ContentslistsavailableatSciVerseScienceDirect

Animal

Reproduction

Science

j o ur na l ho me p ag e :w w w. e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / a n i r e p r o s c i

Review

article

Reproduction

in

the

endangered

African

wild

dog:

Basic

physiology,

reproductive

suppression

and

possible

benefits

of

artificial

insemination

F.

Van

den

Berghe

a,b, D.B.B.P.

Paris

c, A.

Van

Soom

b, T.

Rijsselaere

b,

L.

Van

der

Weyde

d,

H.J.

Bertschinger

e,

M.C.J.

Paris

d,f,∗aObstetricsandSmallAnimalReproduction,DepartmentofClinicalSciences,FacultyofVeterinaryMedicine,UniversityofLiège,BoulevarddeColonster20,

B44,4000Liège,Belgium

bDepartmentofReproduction,ObstetricsandHerdHealth,FacultyofVeterinaryMedicine,GhentUniversity,Salisburylaan133,9820Merelbeke,Belgium

cSchoolofVeterinaryandBiomedicalSciences,JamesCookUniversity,SolanderDrive,Townsville,QLD4811,Australia

dSchoolofAnimalBiology,FacultyofNaturalandAgriculturalSciences,TheUniversityofWesternAustralia,35StirlingHighway,Crawley,WA6009,

Australia

eDepartmentofProductionAnimalStudies,FacultyofVeterinaryScience,UniversityofPretoria,POBox75058,LynnwoodRidge,0040,Pretoria,SouthAfrica

fInstituteforBreedingRareandEndangeredAfricanMammals,MammalResearchInstitute,UniversityofPretoria,Pretoria,SouthAfrica

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received13February2012

Receivedinrevisedform30May2012

Accepted6June2012

Available online 12 June 2012 Keywords:

Africanwilddog

Dominance ArtificialInsemination Seasonality Oestrouscycle Pregnancy

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

TheAfricanwilddog(Lycaonpictus)isanendangeredexoticcanidwithlessthan5500 animalsremaininginthewild.Despitenumerousstrategiestoconservethisspecies, num-bersoffree-livinganimalsareindecline.Itisahighlysocialspecieswithacomplexpack structure:separatemaleandfemaledominanthierarchieswith,typically,participationof subdominantadultsintherearingofthedominantbreedingpairs’pups.Basic reproduc-tiveknowledgeislargelymissinginthisspecies,withonlylimitedinformationavailable ontheprofileofreproductivehormones,basedonnon-invasiveendocrinemonitoring.The dominantoralphamaleandfemalearereproductivelyactiveandthesubdominantsare generallyreproductivelysuppressed.However,theoccasionalproductionoflittersby sub-dominantfemalesandevidenceofmultiplepaternitywithinlitterssuggeststhatfertilityof subordinatesisnotcompletelyinhibited.Inthisrespect,therearestillconsiderablegapsin ourknowledgeaboutthemechanismsgoverningreproductionandreproductive suppres-sioninAfricanwilddogs,particularlytheinfluenceofdominanceandpackstructureon bothmaleandfemalefertility.Givenconcernsoverthelong-termsurvivalofthisspecies, furtherresearchinthisareaisessentialtoprovidevaluableinformationfortheircaptive breedingandconservation.Reproductiveinformationcanalsobeappliedtothe develop-mentofAssistedReproductiveTechniquesforthisspecies;theutilityofwhichinAfrican wilddogconservationisalsodiscussed.

© 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

∗ Correspondingauthorat:SchoolofAnimalBiology,FacultyofNaturalandAgriculturalSciences,TheUniversityofWesternAustralia,35Stirling

Highway,Crawley,WA6009,Australia.Tel.:+61864882237;fax:+61864881029.

E-mailaddresses:f.vandenberghe@ulg.ac.be(F.VandenBerghe),damien.paris@jcu.edu.au(D.B.B.P.Paris),ann.vansoom@ugent.be(A.VanSoom),

tom.rijsselaere@ugent.be(T.Rijsselaere),leannevdw@gmail.com(L.VanderWeyde),henkbert@tiscali.co.za(H.J.Bertschinger),mparis@ibream.org

(M.C.J.Paris).

0378-4320/$–seefrontmatter © 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Contents

1. Introduction... 2

2. ReproductioninAfricanwilddogs... 2

2.1. Oestrouscycleandmating... 2

2.2. Pregnancy,parturition,littersandthebiasinsex-ratioofoffspring... 3

2.3. Seasonalityofreproduction... 3

3. Suppressionofreproduction... 4

3.1. Stress-inducedsuppressionofreproduction?... 4

3.2. Multiplematernityinpacksandsuppressionoffemalereproduction... 5

3.3. Suppressionofmalereproduction... 5

4. FurtherresearchinAfricanwilddogreproduction... 6

5. PotentialroleforassistedreproductivetechniquesintheAfricanwilddog... 6

6. Conclusion... 7

References... 7

1. Introduction

TheAfricanwilddog(Lycaonpictus),likethedomestic dog(Canisfamiliaris)andthewolf(Canislupus),belongs to the Canidae (order Carnivora). Formerly occurring throughoutsub-SaharanAfrica,Africanwilddogshave dis-appearedfrommostoftheiroriginalrangewithlessthan 5500animalsleftinthewild,andarenowoneofthemost endangeredcanidsintheworld(McNuttetal.,2008).The keythreatsaffectingfree-livingAfricanwilddogsare habi-tatfragmentationandloss,infectiousdiseases,intra-and interspeciescompetition(mostlywithlions,Pantheraleo, andhyenas, Crocutacrocuta)andanthropogenic mortal-ity(e.g.persecutionandroadaccidents)(CreelandCreel, 1998;VucetichandCreel,1999;Woodroffeetal.,2007). Numerousstrategieshavebeenundertakentopreservethe species,includingre-introduction,communityawareness andeducation(Gussetetal.,2008),andcaptivebreeding programs(Frantzenetal.,2001),butstilltheirnumbersare indecline(McNuttetal.,2008).Africanwilddogshavelarge homerangesfrom1500to2000km2andlowpopulation densities(WoodroffeandGinsberg,1997;CreelandCreel, 1998),makingthemrelativelyvulnerabletohabitat frag-mentationandtocontactwithhumansorhumanactivities (CreelandCreel,1998).InSouthAfrica,theKrugerNational Parkistheonlyprotectedhabitatconsideredlargeenough tocontainaviableself-sustainingpopulation(Fanshawe etal.,1997).Re-introductionsofAfricanwilddogsinother conservationareasandperiodictranslocationshavebeen performedinordertosupplementtheoriginalpopulation (Gussetetal.,2006).Thesetranslocationsareperformed tomimicthenaturaldispersalandsustainasingle popu-lationcomposedofdifferentisolatedsubpopulations.This humaninterventioniscalledmetapopulationmanagement (Davies-Mostertetal.,2009).

Africanwilddogscommonlyliveinpacksof5–15adults andyearlings,andshowacomplexsocialstructure con-sistingofseparatemaleandfemaledominancehierarchies (CreelandCreel,2002).Thealphamaleandfemalehave almostexclusivereproductiveprivileges,while subdomi-nantsrarelybreedbuthelptorearpups.Thiscooperative breedingsystemisalsoseeninseveralothercarnivores includingmeerkats(Suricatasuricatta),graywolves(Canis lupus) and dwarf mongooses (Helogale parvula) (Creel, 2005;Youngetal.,2006).Inthewild,thereisapositive

relationshipbetweenpacksize andsuccessfulbreeding, huntingandsurvivalintheAfricanwilddog(Courchamp andMacdonald,2001;Buettneretal.,2006),witha criti-calthresholdofatleastfiveanimalsinapack(Courchamp andMacdonald,2001;Grafetal.,2006).Thus,thefailureof somereintroductionattemptsmightbeexplainedbythe inabilitytoformormaintainapackoffiveormore ani-mals,coupledwithalackofsufficientnumbersofseparate packstoestablishageneticallyself-sustainingpopulation (Gussetetal.,2009).Dispersalofadultanimalstypically involvessingle-sexgroupsandoccursatanolderagein males(medianage28.1months)thaninfemales(median age21.8months)(McNutt,1996).Anewpackismostly formedwhentwoopposite-sexgroupsjointogetherand, aftera‘trialperiod’,astablereproductiveunitisformed (McCreeryandRobbins,2001;CreelandCreel,2002). Dur-ingthe‘trialperiod’,differentfactorslikegroupsize,mate choiceandcompetitionareresponsiblefortheformation ofastablesocialstructure.Annulmentofapack,for exam-plecausedbymatecompetitionandmatechoice,canoccur withinseveralmonthsofinitialassociation(McCreeryand Robbins,2001).

Asstatedabove,therearediversebutimportantthreats affectingcurrentAfricanwilddogpopulations.Although infertilityisnotacommonproblemintheAfricanwilddog, forthelong-termpropagationofthisspeciesitiscrucially important to thoroughly understandtheir reproductive physiology in order tocarefullyregulate captive breed-ingprogramstomaximizethepresentgeneticdiversity.In thisarticleweprovideanoverviewofcurrentreproductive knowledgeandthepossiblemechanismsofreproductive suppressionintheAfricanwilddog.Inaddition,we iden-tifyareasrequiringfurtherresearch,anddiscussthemerits ofusingAssistedReproductiveTechniques(ART)towards theconservationofthisspecies.

2. ReproductioninAfricanwilddogs 2.1. Oestrouscycleandmating

Mostcanidsstudiedtodateshowsimilarreproductive features:amono-oestrouscyclewitha longpro-oestrus and oestrus, a pregnant or non-pregnant (pseudopreg-nancy) period of dioestrus and an obligatory period of anoestrus(AsaandValdespino,1998;Concannon,2009).

Anexception tothis is for example theAsian wilddog orDhole(Cuonalpinus)thatexhibitsseasonalpolyoestrus withacycleoffourtosixweeks(Durbinetal.,2004).

Aswithmostendangeredwild-livingspecies,thereis adearthofknowledgeaboutfemalereproductive physi-ologyinAfricanwilddogs;largelybecauseitisgenerally difficulttoobtainsamplesfor analysis.Limiteddatahas beencollectedusingblood serumfromAfricanwilddog bitches(vanHeerdenandKuhn,1985).However,improved techniquesusingnon-invasiveendocrinemonitoring,now permitsbasicreproductiveinformationtobeobtainedon amoreregularbasis(LasleyandKirkpatrick,1991). Fae-calsampleshavebeenusedtoassesssteroidmetabolites byradioandenzymeimmunoassaysinAfricanwilddogs (Creelet al.,1997;Monfort etal.,1997; Johnstonetal., 2007;SantymireandArmstrong,2009).

Behaviourally,theapproach(approximately1.5months priortotheonsetofpro-oestrus)ofthebreedingseasonin captivedogsinSouthAfricaismarkedbyincreased intra-packaggression,whichmostlyinvolvesfemales(Boutelle andBertschinger,2010).Fightingasaresultofaggression maybecomesoseverethatdeathsoccurandisindeedthe mostcommoncauseofmortalityinadultandsub-adult dogsincaptivityinSouthAfrica(vanHeerden,1986;van Heerdenetal.,1996).Thiscomplexsocialstructurehasalso oftenledtosimilarproblems,leadingtomorbidityandat timesmortality,inzoologicalinstitutionsworldwide.Up tonow,nohardfigureshavebeencollected,sotheexact severityoftheproblemcanonlybespeculatedupon(M. Paris,personalcommunication).Mortalityresultingfrom intra-packaggressionispresumablylesscommonin free-rangingdogsbecausetheyareless space-restrictedand, assuch,maybebetterabletoavoidconflict(Boutelleand Bertschinger,2010).

Studies in captive females show that the period of pro-oestrusandoestrustakes14–20days (vanHeerden and Kuhn, 1985).During pro-oestrus femalereceptivity slowly increases beforemating, during which time the bondbetweenthedominantmaleandfemalestrengthens (vanHeerden and Kuhn, 1985; Creel et al.,1997). Vul-varswelling andsanguinousvaginal dischargehasbeen observedatthetimewhenoestrogeniselevated(Monfort et al., 1997).Behavioural oestrus lasts six to nine days (Monfort et al., 1997). Moreover, measurement of fae-calprogesteronemetabolitescollectedindividuallyfrom group-housed individuals shows thatfemales appear to cycleintheabsenceofmales(Parisetal.,2008).Research is currentlyongoing toinvestigatethis ingreaterdetail (L.VanderWeyde,unpublisheddata).Matingoccursover a period of three to sevendays at the time of peak or decliningoestrogenandincreasingprogesterone metabo-liteconcentrations(Monfortetal.,1997).Thecopulatorytie observedinallcanids(AsaandValdespino,1998),isvery shortinAfricanwilddogsandcaneasilygoundetectedin captivity(H.Verberkmoes,personalcommunication;H.J. Bertschinger,personalobservation),althoughithasbeen observedtolastupto15mininthewild(H.J.Bertschinger, personalobservation).Moreover,asinthedomesticdog, captivebutnotwildmaleshavebeenobservedtoturnonce thetie hasbeen established(H.J.Bertschinger, personal observation).

Table1

MajorreproductiveseasonofAfricanwilddogsinthesouthernand

north-ernhemisphere.

Southernhemisphere Northernhemisphere Oestrus February–May LateAugust–earlyOctober

Birth May–July October–December

2.2. Pregnancy,parturition,littersandthebiasin

sex-ratioofoffspring

Pregnancy,when countedfromthetimeoflast

mat-ing,takes approximately69–72 days (van Heerdenand

Kuhn,1985;Creeletal.,1997;Monfortetal.,1997). Partu-ritioncoincideswithadropinprogesterone,asevidenced byadecreaseinfaecalprogesteronemetabolites(Monfort etal., 1997).The numberof nipplesonan Africanwild dogbitchcanvaryfrom12to16(vanHeerdenandKuhn, 1985),withlargelittersconsistingofapproximately10–12 pups(Comizzolietal.,2009).Whilelactationin subdom-inantfemalesiscommoninwolves(AsaandValdespino, 1998),itisrareinAfricanwilddogs(Creel etal.,1997). Weaningtakesplaceatabout10weeksalthoughpupsstart toeatregurgitatedfoodfrom14 daysof age(Smithers, 1983).SomepopulationsofAfricanwilddogsshowabias inthesex-ratiooflitterswithprimiparousbitches produc-ingmoremalepupsthanmultiparousones(Creel etal., 1998;McNuttandSilk,2008).Theexactmechanism under-lyingthisphenomenonisyettobedetermined,butithas beenproposed that elevated oestrogenlevels in primi-parousbitchesmayselectivelyaffectuterineimplantation ofmalezygotesormaycausespermselectioninthefemale reproductivetract(Creeletal.,1998).

2.3. Seasonalityofreproduction

Mostcanidsseasonallyreproduce(AsaandValdespino, 1998).InthecaseoftheAfricanwilddog,mostpupsare borninthesouthernhemispherebetweenMayandJuly (McNutt,1996;Buettneretal.,2006),howeveritshiftsby upto6 monthsinanimalslivinginthenorthern hemi-sphere(Verberkmoes,2008)(Table1).

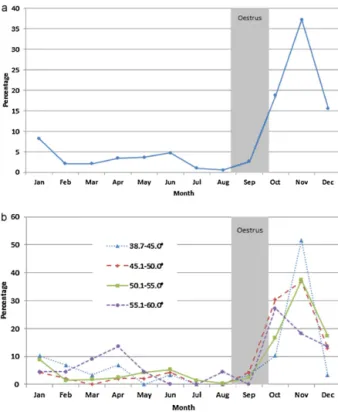

BasedonEuropeanregionalstudbookinformation,the majorbreeding seasonfor captive African wilddogsin EuropeisaroundAugust/Septemberresultinginapeakof birthsinNovember(Verberkmoes,2008)(Fig.1a).When births were grouped by the latitude at which animals werehoused,noobviousdifferencesinthepatternofpeak birthswasobserved(Fig.1b).Birthshowever,dooccurat lowerlevelsyear-round, withtheleastoccurringinJuly andAugust(1.1and0.5%respectively).Although consid-eredstrictlymono-oestrus,somecaptiveAfricanwilddog bitchesinEuropealsoshowasecondminorbreeding sea-sonbetweenFebruaryandMarch(withacorresponding increaseinbirthsduringApril),iftheyfailtobecome preg-nantduringthemainbreedingseasonoriftheylosetheir pups(H.Verberkmoes,personalcommunication;Fig.1b). Similarly,asecondminorbreedingseasoninAfricanwild dogs has been observed in South Africa (Boutelle and Bertschinger,2010).

Fig.1.MonthlypercentageofAfricanwilddoglittersbornincaptivityin

Europefrom1938to2008presentedas(a)combineddataand(b)grouped

bylatitude.Theperiodofoestrusisindicatedingrey.Databasedonthe

Europeanregionalstudbook(Verberkmoes,2008).

Thecollectiveevidencesuggeststhatreproductionof theAfricanwilddogisgenerallyseasonal,yetbirthscan occurat every month of theyear, supporting the idea that the window of fertility of the African wild dog is broader than described for temperate and arctic zone canids.Valdespino(2007)showedanegativerelationship between latitude and the duration of the reproductive season in canid species, with longer reproductive sea-sonsoccurringatlowerlatitudes.Seasonalreproductionis mainlyinfluencedbyphotoperiod,butalsobyotherfactors liketemperature,bodyconditionandnutritionalintakeas describedforexampleinmares(Nagyetal.,2000).

InmostseasonallybreedingCanidaeincludingmaned wolves(Chrysocyonbrachyurus;Vellosoetal.,1998;Maia etal.,2008),redandbluefoxes(VulpesvulpesandAlopex lagopus; Farstad, 1998; Andersenberg et al., 2001) and coyotes(Canislatrans;MinterandDeLiberto,2008), testos-teronelevels,testissizeandsemenproductionincreasein malesduringthebreedingseason.IntheAfricanwilddog, themeasurementoftestosteronelevelshasgiven conflict-ingresults(Creeletal.,1997;Monfortetal.,1997;Johnston etal.,2007),buttestissizeappearstoincreaseinthe breed-ingseasonandsemencouldnotalwaysbecollectedatother timesoftheyear(Johnstonetal.,2007).However,failure tocollectsemenby electroejaculation doesnot conclu-sivelyprovespermatogenicarrestinthisspecies,because seasonal reduction in male accessory glands may also reducethesurfacecontactoftheprobeandeffectiveness oftheelectrostimulation(D.Paris,personalobservation; H.J. Bertschinger, personal observation). Moreover, the

European regional studbook data (Verberkmoes, 2008) presented in Fig. 1 suggest that males are reproduc-tively fertile throughout most of the year. This could indicate that female fertility is generally photoperiod-dependentwhilemalefertilityisopportunisticallyprimed by femalepheromonalcues.A similarphenomenonhas beenobservedinthetammarwallaby(Macropuseugenii) inwhichfemaleseasonalityisstrictlycontrolledby pho-toperiodwhilemalesarefertileyear-round;butthequality oftheirsemendecreasesoutsidethemainbreeding sea-son (Paris et al., 2005).Similarly, in African wilddogs, semenquality(percentagemotilesperm,motilityrating andspermmorphology)waspoorerinout-of-season sam-plesthanin-seasonsamples(Nöthlingetal.,2002).Inmale red wolves (Canis rufus), it hasbeen shown that faecal androgenconcentrationsbegintorisefourmonthspriorto theonsetofoestrusinfemales,withpeakconcentrations coincidingwithmaximalspermproduction(Walkeretal., 2002).Thus, althoughspermatogenesis doesnot appear tobecompletelyarrestedinmaleAfricanwilddogs,they wouldneedtodetectandrespondtofemalepheromonal cuessufficientlyearlytoensureoptimalreproductive syn-chronicitybetweenthesexes.

In conclusion, even though there were a few births ofcaptive Africanwilddogsin Europeoutsidethemain breedingseason,thechancesoffertilizationand success-fulpregnancyarelikelytobemuchlowerdueto(i)alack offemalecyclicity,(ii)poorsemenqualityinfluencedby lowertestosteronelevels,(iii)alackofreproductive syn-chronicitybetweenmalesandfemales,and(iv)amyriad ofenvironmentaleffectsthatcouldincludelatitude, pho-toperiod,temperature,changesinhousinganddietduring winter,etc.

3. Suppressionofreproduction

3.1. Stress-inducedsuppressionofreproduction?

The mechanismunderlyingreproductivesuppression that inhibits or greatly reducesthe fertilityof subordi-nates is notwell understood.The relationshipbetween social dominanceandcirculatingsteroidhormonesmay beonepossiblemechanisminvolvedinreproductive sup-pression.Inmanyspecieswithacomplexsocialstructure, hierarchyanddominancearerelatedtothelevelof circu-latingglucocorticoids(GC)(Creel,2001,2005).Inratsand primates,dominantanimalsshowlowercortisol concen-trationsthansubdominantanimals(deVilliersetal.,1997; Creel,2001).‘Socialstress’experiencedbysubordinates, cancauseachronicincreaseofGCsecretion(Creel,2001). Itisknownthatchronicaugmentationofthesehormones costs/requiresenergyandcansuppressother physiologi-calsystemsnotimmediatelynecessaryforsurvivaland,in thecaseofthereproductivesystem,cancause ‘psycholog-icalcastration’(Creeletal.,1997;Barjaetal.,2008).One cooperative breederin whichstress-related suppression of reproductionis animportantstrategy isthemeerkat (Suricatasuricatta),wherepregnantfemaleschase subor-dinatefemalesfromthegroupresultinginanincreaseof GClevelsinsubordinatesandadown-regulationoftheir reproduction(Youngetal.,2006).However,inmanyother

cooperativebreederssuchaswolves(Canislupus),female dwarfmongooses(Helogaleparvula)andmaleandfemale Africanwilddogs,itisdominantanimalsthatexhibithigher GC levels thansubordinates without anyadverse effect on their fertility (Creel et al., 1997; Creel, 2005; Barja etal.,2008).Theseconflictingobservationsacrossspecies exemplifytheWingfield’schallengehypothesisstatingitis sometimesmorestressfultobedominantanditis some-timesmorestressfultobesubordinate(Wingfieldetal., 1990).

3.2. Multiplematernityinpacksandsuppressionof femalereproduction

Stress-inducedreproductivesuppressionmayalsobe anunlikelymechanisminAfricanwilddogsbecauseboth subdominant malesand females remainfertile tosome extent.Inthewild,thealphafemaleproduces75–81%of alllitters(Creel,2005).Multiplematernityinpacks,where subdominantfemalesalsoreproduce,occursin40%ofthe packyears,but onlyeightpercentofthesubdominant’s pupssurvivebeyondtheirfirstyear(Girmanetal.,1997). Thishighpupmortalityisprobablypartlyduetoinfanticide bythealphafemaleobservedbothinthewildand captiv-ity(Girmanetal.,1997;RobbinsandMcCreery,2000).In caseswheresubdominantfemalescopulate,itisgenerally thebetafemalethatdoesso(Creeletal.,1997). Subdomi-nantfemalesdocycle(vanHeerdenandKuhn,1985;Paris etal.,2008),butthefrequencyandextenttowhichbetaor lowerrankedfemalescanreproduceisunknown,leaving crucialgapsinourunderstandingofreproductive suppres-sion inthis species. Bertschinger et al.(2002) observed oestrus attwo to three weekintervals inthree captive femaleshousedtogetherinthesameenclosure.Hofmeyr (1997)observedbreedingbytwosub-rankingfemalesafter threecaptive-bornfemaleswereco-housedinapre-release enclosure for fivemonths withthree wildmales. How-ever,noneofthepupssurvived.Oneyearafterrelease,the alphafemalewasmatedinFebruarybyallthreemales, gavebirthinMaybutemergedfromthedenwithoutpups whichwerepresumeddead.Subsequently,boththe sec-ondandthird-rankingfemalesexhibitedoestrusandwere matedatdifferenttimesinApril,andgavebirthinashared denattheendofJuneandmiddleofJulyrespectively.The third-ranked femaleemergedwithhersevenpupsafter fightingdisplacedthesecond-rankedfemale,whoselitter presumablyhadbeenkilled.However,thefollowingyear, theoriginalsecond-rankingfemalebecamealphafemale and produced 12 pups. Thus, it appears that subdomi-nantfemalesofanyrankarereproductivelyfertile,butthe opportunitytosuccessfullyraisetheirpupsappearstobe status/hierarchy-dependent.

In graywolves,allsubdominantfemales ovulateand matingissuppressedbydominantfemalebehaviour(Asa andValdespino,1998),whileinsomeprimates, reproduc-tion is physiologically suppressedby arresting pubertal development(Abbottetal.,1981).Behaviouralinhibition ofcopulationamongsubdominantanimalshasoftenbeen observedandisrecognizedasamechanismofreproductive suppressioninAfricanwilddogs(vanHeerdenandKuhn, 1985).Itispossiblethatbehaviouralsuppressionallowsall

Africanwilddogfemalestoovulatebutpreventscopulation insubordinatefemales,resultingin aperiod of pseudo-pregnancythatmakesthemmorereceptiveasmaternal carers.Thismayreflectthehighenergydemandsrequired tosuccessfullyraiseasinglelitterwithinthepack. 3.3. Suppressionofmalereproduction

Inmales,subordinatesoccasionallycopulatebuttoa lesserextentthanthealphamale(Creeletal.,1997).This raisesquestionsaboutthefertilityofthesesubdominant matings.Testosteronelevels,testissize,andsemen pro-duction are positively correlated in mammals (Preston etal.,2001;Gomendioetal.,2007).Duringthebreeding seasonin African wild dogs,the dominantmale shows highertestosteronelevelsthansubdominants(Creeletal., 1997;Monfort et al.,1997; Johnstonet al., 2007).High testosteronelevelscanpositivelyinfluenceboth spermato-genesisandthesizeandsecretoryactivityofaccessorysex glands(Parisetal.,2005;Gomendioetal.,2007).Although spermatogenesisdoesnotimprovefurtheronceacertain thresholdoftestosteronehasbeenreached(Walker,2009), dominant males with higher testosterone could have higherqualitysementhansubordinates.Thefactthattestis sizeinsubdominantmaleAfricanwilddogsalsoincreases duringthebreedingseason(Johnstonetal., 2007), sup-port theidea that spermatogenesis is not arrestedas a resultof dominance.However, when subjectedto elec-troejaculationduringthebreedingseason,mostmalesin thecaptive packproduced spermatozoa,butmean ejac-ulatequalitywasreducedoncethedominancehierarchy wasestablished(Johnstonetal.,2007).Thissuggeststhat dominancemayaffectsubordinatemale fertility. Unfor-tunately,sampleswerepooledforanalysisinthisstudy, makingitunclearwhethertheoveralldecreaseinsemen qualitywasspecificallycausedbypoorsemenfrom sub-dominantmales.Thus,theextenttowhichdominanceand packstructuremaypositivelyornegativelyaffectfertility requiresfurtherinvestigation.

Moreover,dominanceandoptimaltimingoforhigher ratesofcopulationdonotalwaysresultinhigher repro-ductivesuccess.Inthetammarwallaby(Macropuseugenii), despitedominantmalesguarding andbeingthe firstto matewithoestrousfemalesattheoptimaltimeof copu-lation,theysireonlyhalfoftheoffspringborncomparedto second,thirdandfourthrankingmales(Hynesetal.,2005). InSoayrams(Ovisaries),largerdominantmalesshowa veryhighrateofmating,butthiseventuallyleadstosperm depletionasthematingseasonprogresses,makingthem lessfertilethansubordinatemales(Prestonetal.,2001). InAfricanwilddogs,Girmanetal.(1997)showedmultiple paternityinatleast10%oflittersand,inonecase,paternity wasalsoassignedtothebrotherofthedominantmale.This suggeststhatintra-packmatingdoesexistinthewild,and demonstratesthatatleastsomesubdominantmalesare fertileirrespectiveofwhethertheyarerelatedorunrelated tothedominantmale.Multiplepaternitywasreportedin fivelitterssampledat9–12monthsold,fromthree free-rangingpacksinSouthAfrica(Mouiex,2006).Inonelitter ofeight,fourpupsweresiredbythealphamale,threeby thesecondandonebythethirdrankingmale.Inthefour

remaininglittersthereweretwosireseachandthe num-bersofpupssiredbythealphaandsecondrankingmale were11andone,threeandone,fiveandoneandsevenand one,respectively.ThissupportsobservationsinMadikwe GameReserveofonefemalebeingmatedbythreedifferent males in order of ranking (M. Hofmeyr, personal com-munication).Subdominantmalefertilitywasalsorecently demonstratedbySpieringetal.(2010)inwhich approxi-matelyhalfofthepupsweresiredbythealphamale,while remainingpupsweresiredbythesecondandthirdranking males.

Althoughsubdominantmalesappeartobeabletosire offspring, the extent of this fertility/sub-fertility is not definitivelyclear.Indeedevidenceofreducedsemen qual-ityandlimitedpaternitysuccesssupporttheideathatthere isatleastsomedegreeofreproductivesuppressionthat limitsmatingaccessandfertilizationsuccessof subdomi-nantmales.Besidesbehaviouralsuppression,atthisstage wecannotexcludeotherhormonalor pheromonalcues thatmayactonthehypothalamic–pituitary–gonadalaxis toinducesub-fertilityinmaleAfricanwilddogs.

4. FurtherresearchinAfricanwilddog reproduction

Infertilityordecliningreproductionisnotthecauseof endangermentinAfricanwilddogs(Comizzolietal.,2009). Whenpacksizeissufficientlylargeandresourcesplentiful, thedominantpairwillproducelargelittersonceperyear inthewild(CourchampandMacdonald,2001).Incaptivity, sufficientnumbersofpupsarealsoproducedtomaintain anadequatepopulationsize.However,itiscritically impor-tantforthelong-termcaptivepropagationofthisspecies, tocarefullyregulatebreedingpartnersandmaintaina pop-ulationsizethat willeffectively maximizeand maintain currentlevelsofgeneticdiversity(Frantzenetal.,2001).In ordertoachievethisandtoavoidinbreedingdepression, currentstrategiesinvolvetheregulartranslocationoflive animals.In captivity,maleand femalesingle-sexgroups areoftencombinedtoconstituteanewsocialunitinan attempttoimitatedispersalpatternsthatoccurnaturallyin thewild(H.Verberkmoes,personalcommunication).Such introductionsaremadedifficultbecauseof thecomplex socialstructureoftheseanimalscoupledwiththe unnat-ural space-limited environment often present in zoos; thatcancausestresstoanimalsandresultinaggression and sometimes morbidity and mortality. Thus research directedatovercomingproblemsofaggressionis essen-tial.OnesuchapproachhasbeenundertakenbyVlamings et al. (2009) who investigated whether Dog Appeasing Pheromone (DAP) can be used to minimise aggression duringintroductions,withthehopeofreducingcasesof morbidityandmortality.Asecondapproach,couldinvolve theuseofartificialinseminationtoinfusenewgenesinto existinggroupswithoutdisruptingtheirsocialhierarchy bytheintroductionofnewindividuals(seethefollowing section).

In addition tomodifying behaviour,studies directed at further understanding and controlling the female reproductivecycleofthespeciescouldhelpimprove ani-malwelfare and captive conservationmanagement. For

example, there is an urgent need to improve current methodsofcontraceptionforgeneticallyover-represented captiveindividuals.Previouscontraceptiveadministration ofprogestins,havebeenshowntogreatlyincreasetherisk of developing pyometra, to which theAfrican wilddog bitchishighlysusceptible(Hermesetal.,2001;Boutelle and Bertschinger, 2010). Deslorelin, a GnRH agonist, is currentlythesafestmethodforinducingreversible con-traceptioninallcarnivores,includingtheAfricanwilddog, butfurtherresearchisneededtogainmoreinformationon dosageandreversibility(Bertschingeretal.,2001,2002; BoutelleandBertschinger,2010).

Basicknowledgeisstillmissingonreproductive hor-moneprofilesinbothfemaleandmaleAfricanwilddogs,as wellastheeffectofseason,dominanceandpackstructure onfertility.Endocrinemonitoringoffaecalsamplescanbe usednon-invasivelytoanswermanyofthesequestions. Such endocrine datacoupledwithbehavioural observa-tionscollectedinthenorthernhemisphereduringthe2009 seasonfromgroup-housedindividualsinthepresenceor absenceofmales,iscurrentlybeinganalysed(L.Vander Weyde, unpublished data). These studies also incorpo-rateendocrinedatacollectedfromfree-ranginganimalsin Hluhluwe–UmfoloziGameReserve,SouthAfrica.

5. Potentialroleforassistedreproductive techniquesintheAfricanwilddog

Artificial Insemination (AI) coupledwith semen cry-opreservationhaslongbeenconsideredoneofthemost powerfulandleastinvasiveforms ofAssisted Reproduc-tive Techniques (ART)for thepreservation, distribution andimprovementofanimalgenetics(Durrant,2009).Its value and success in overcoming infertility in humans and animals as well as improving livestock production (e.g.increasedmilkproduction ormeatquality)is illus-tratedbyitswidespreadapplication(Mastromonacoetal., 2011).Thesetechniquesarebeingincreasingly incorpo-ratedintothecaptivebreedingprogramsofawiderange of wildlife species. In this regard, perhaps one of the greatest AI successstories hasbeen thebirth and wild re-introductionofover139endangeredblack-footed fer-ret (Mustela nigripes) kits using AI and cryopreserved semen (Howard and Wildt, 2009). Multiplebirths have resulted from AI in other mammals including a vari-etyofnon-domesticfelids,cervids,non-domesticbovids, camelids, marsupials, primates, ursids and pachyderms (Paris and Mastromonaco, 2009). Moreover, in at least one case,AIhasalready beenconductedsuccessfully in captiveNorth-Americancheetahs(Acinonyxjubatus)using frozen–thawedsemenfromwild-caughtmaleswithoutthe need to remove these malesfrom theirnatural habitat (Howardand Wildt, 2009).Despite thesesuccesses,the lackofastrongworkingrelationshipbetweenconservation biologists/animalmanagersandreproductivespecialists, aswellasgeneraldistrustof‘artificial’manipulationsof reproduction,hascreatedoneof theobstaclesthat pro-hibit thewidespread useof AIin wildlife species (Holt andLloyd,2009;Mastromonacoetal.,2011).Itshouldbe recognizedthatalthoughboth thesegroups have differ-ingideologies,theysharea commongoalinstrivingfor

thepropagationand conservationofthreatenedspecies. Increaseddialogueis neededtooutlinethemeritsofAI toovercomespecies-specificproblems(suchasthehighly complexsocialstructureandhierarchyoftheAfricanwild dog)thatinfluencethesuccessandgeneticmanagementof captivenaturalbreedingprograms.

In CanidaesuccessfulAIusing bothfresh andfrozen semenhasbeen widelyperformedin foxes and wolves (Thomassen and Farstad, 2009). Several wolf species are threatened by inbreeding and human interference (ThomassenandFarstad,2009).Sincewolveshavea com-plexmonogamoussocial structure (Asa andValdespino, 1998),AIcouldpermittheintroductionofnewblood with-outdisruptingestablishedpair-bonds.

However, reproduction is regulated by a series of species-specific mechanisms and patterns of hormonal cyclicity.Asaresultofsuchdifferences,reproductive infor-mationcannot alwaysbeextrapolatedbetweenspecies, evenifcloselyrelated(Parisetal.,2007).Evenwithinthe Canidae,thereareseveralimportantdifferencesin season-alityandreproduction(Table3inWildtetal.,2010).This lackofbasicreproductiveknowledgeinmanyendangered animalsisoftenthereasonwhyARTscannotbeusedas aneffectivemethodtohelprescueacriticallyendangered speciesalreadyonthebrinkofextinction(HoltandLloyd, 2009).

The use of AI has yet tobe reported in the African wilddog,andonlytwopublicationscurrentlydescribethe cryopreservationofsemeninthisspecies(Hermesetal., 2001;Johnstonetal.,2007).Thedevelopmentand optimi-sationofthesetechniquesisofimmediateprioritywhile viable populationsofanimalsstill exist.Inaddition,the establishmentofagenomeresourcebankcontaining cry-opreservedsemenofgeneticallyvaluableanimals,together withbasicreproductiveresearch,deliversacertainlevel of insurancefor the future of Africanwilddog popula-tions. Such bankscan provide a bufferagainst possible threatssuchasfiresorsuddenepidemicofinfectious dis-easesbothincaptivityandinthewild(Pukazhenthietal., 2007).Indeed,anoutbreakofCaninedistempervirusina captiveAfricanwilddogbreedinggroupin2000resulted inthedeathof49outof52animalswithintwomonths (van de Bildt et al., 2002). During the late eighties in theMasai Maraand SerengetiNationalParks bordering KenyaandTanzania,diseaseresultedinthedisappearance of8entireAfricanwilddogstudypacks(Woodroffeand Ginsberg,1997),althoughrecentevidencesuggestsAfrican wilddogshavepersistedintheSerengeti–Mara(Marsden et al., 2012).Gene (semen) banking initiatives coupled withartificialinseminationtechniques,therefore,should be considered asimportant for conservationas disease prevention,habitatpreservationorcommunityeducation. Moreover,sinceAfricanwilddogshaveacomplexsocial structure,withstrictdominancehierarchies,AIcould over-comethehighlevelsofintra-packaggressionassociated withthetranslocationandintroductionofnewgenetically valuableanimals(Johnstonetal.,2007).Transportationof semeninsteadof liveanimalstoinfuse newgenesinto a groupcannotonly improveanimal welfare,by reduc-ingtranslocation-andintroduction-associatedaggression, but can also provide economic and ecological benefits.

Transportationof semenischeaper, avoidstheremoval ofanimalsfromthewild,andcanalsodecreasethe inci-denceofdiseasetransmission.Inthewild,cryopreserved semenandAIcouldpotentiallybeusedtofacilitate meta-populationmanagementsoastoavoidinbreedinginfenced reservesthataresmallerthantherangerequiredforAfrican wild dog populations to be self-sustaining, or in cases wherenaturaldispersalislimited(M.Szykman,personal communication).

6. Conclusion

TheAfrican wilddog is anendangeredcanid witha dominance hierarchyand a cooperative breeding strat-egy.Itsreproductionappearstobebroadlyseasonaland femalesaregenerallymono-oestrus,althoughlower lev-els of fertile mating may occur year round. Collective evidencesuggeststhat reproductivesuppressionof sub-dominant animals primarily occurs at the behavioural level,sincebothmaleandfemalesubdominant individu-alsoccasionallyproducealimitednumberofoffspringbut thesuccessofraisingsubdominantfemalelittersisgreatly reduced. However, it is yet to be determined whether dominanceandpackstructurehavesecondaryeffectsthat reducethefertilityofsubdominantindividualsviaother mechanisms (such as hormone-induced or pheromone-inducedsuppression).Therearestillconsiderablegapsin ourknowledgeofmaleandfemalereproductivehormone profilesandfemalecyclicity.Moreover,effortsneedtobe directedtowardthemanagementofintra-packaggression, thedevelopmentofspermcryopreservationandartificial insemination, andtheimprovement of contraceptionas complementarystrategiestogeneticallymanageboth cap-tiveandwildpopulations.

References

Abbott,D.H.,McNeilly,A.S.,Lunn,S.F.,Hulme,M.J.,Burden,F.J.,1981.

Inhi-bitionofovarianfunctioninsubordinatefemalemarmosetmonkeys

(Callithrixjacchusjacchus).J.Reprod.Fertil.63,335–345.

Andersenberg,K.,Wiger,R.,Dahl,E.,Torp,T.,Farstad,W.,Krogenaes,A.,

McNeilly,A.S.,Paulenz,H.,Ropstad,E.,2001.Seasonalchangesin

sper-matogenicactivityandinplasmalevelsofFSH,LHandtestosterone,

andtheeffectofimmunizationagainstinhibininthemalesilverfox

(Vulpesvulpes).Int.J.Androl.24,284–294.

Asa,C.S.,Valdespino,C.,1998.Canidreproductivebiology:anintegration

ofproximatemechanismsandultimatecauses.Am.Zool.38,251–259.

Barja,I.,Silvan,G.,Illera,J.C.,2008.Relationshipsbetweensexandstress

hormonelevelsinfecesandmarkingbehaviorinawildpopulationof

Iberianwolves(Canislupussignatus).J.Chem.Ecol.34,697–701.

Bertschinger,H.J.,Asa,C.S.,Calle,P.P.,Long,J.A.,Bauman,K.,DeMatteo,

K.,Jochle,W.,Trigg,T.E.,Human,A.,2001.Controlofreproduction

andsexrelatedbehaviourinexoticwildcarnivoreswiththeGnRH

analoguedeslorelin:preliminaryobservations.J.Reprod.Fertil.Suppl.

57,275–283.

Bertschinger,H.J.,Trigg,T.E.,Jochle,W.,Human,A.,2002.Inductionof

contraceptioninsomeAfricanwildcarnivoresbydownregulationof

LHandFSHsecretionusingtheGnRHanaloguedeslorelin.Reprod.

Suppl.60,41–52.

Boutelle,S.M.,Bertschinger,H.J.,2010. Reproductivemanagement in

captiveandwildcanids:contraceptionchallenges.Int.Zoo.Yb.44,

109–120.

Buettner,U.K.,Davies-Mostert,H.T.,duToit,J.T.,Mills,M.G.L.,2006.

Fac-torsaffectingjuvenilesurvivalinAfricanwilddogs(Lycaonpictus)in

KrugerNationalPark,SouthAfrica.J.Zool.272,10–19.

Comizzoli,P.,Crosier,A.E.,Songsasen,N.,Gunther,M.S.,Howard,J.G.,

Wildt,D.E.,2009.AdvancesinReproductiveScienceforWild

Concannon,P.W.,2009.Endocrinologiccontrolofnormalcanineovarian

function.Reprod.Domest.Anim.44(Suppl.2),3–15.

Courcha1mp,F.,Macdonald,D.W.,2001.Crucialimportanceofpacksize

intheAfricanwilddogLycaonpictus.Anim.Conserv.4,169–174.

Creel,S.,2001.Socialdominanceandstresshormones.TrendsEcol.Evol.

16,491–497.

Creel,S.,Creel,N.M.,1998.SixecologicalfactorsthatmaylimitAfrican

wilddogs(Lycaonpictus).Anim.Conserv.1,1–9.

Creel,S.,Creel,N.M.(Eds.),2002.TheAfricanWildDog.Behavior,Ecology,

andConservation.UniversityPress,Princeton.

Creel,S.,Creel,N.M.,Mills,M.G.L.,Monfort,S.L.,1997.Rankand

repro-ductionincooperativelybreedingAfricanwilddogs:behavioraland

endocrinecorrelates.Behav.Ecol.8,298–306.

Creel,S.,Creel,N.M.,Monfort,S.L.,1998.Birthorder,estrogensand

sex-ratioadaptationinAfricanwilddogs(Lycaonpictus).Anim.Reprod.

Sci.53,315–320.

Creel,S.F.,2005.Dominance,aggression,andglucocorticoidlevelsinsocial

carnivores.J.Mammal.86,255–264.

Davies-Mostert,H.T.,Mills,M.G.L.,Macdonald, D.W.,2009. Acritical

assessmentofSouthAfrica’smanagedmetapopulationrecovery

strat-egyforAfricanwilddogsanditsvalueasatemplateforlargecarnivore

conservationelsewhere.In:Hayward,M.W.,Somers,M.J.(Eds.),

Rein-troductionofTop-OrderPredators.Wiley-Blackwell,London.

deVilliers,M.S.,vanJaarsveld,A.S.,Meltzer,D.G.A.,Richardson,P.R.K.,

1997. Socialdynamics andthe cortisol responseto

immobiliza-tionstressoftheAfricanwilddog,Lycaonpictus.Horm.Behav.31,

3–14.

Durbin,L.S.,Venkataraman,A.,Hedges,S.,Duckworth,W.,2004.Dhole

(Cuonalpinus).In:Sillero-Zubiri,C.,Hoffman,M.,Macdonald,D.W.

(Eds.),Canids:Foxes,Wolves,JackalsandDogs.StatusSurveyand

ConservationActionPlan.IIUCN/SSCCanidSpecialistGroup.Gland,

SwitzerlandandCambridge,UK,pp.210–218.

Durrant,B.S.,2009.Theimportanceandpotentialofartificialinsemination

inCANDES(companionanimals,non-domestic,endangeredspecies).

Theriogenology71,113–122.

Fanshawe,J.H.,Joshua,R.G.,Sillero-Zubiri,C.,Woodroffe,R.,1997.The

statusanddistributionofremainingwilddogpopulations.In:The

IUCN/SSCCanidSpecialistGroup’sAfricanWildDogStatusSurveyand

ActionPlan,Chapter3.

Farstad,W.,1998.Reproductioninfoxes:currentresearchandfuture

challenges.Anim.Reprod.Sci.53,35–42.

Frantzen,M.A.J.,Ferguson,J.W.H.,deVilliers,M.S.,2001.Theconservation

roleofcaptiveAfricanwilddogs(Lycaonpictus).Biol.Conserv.100,

253–260.

Girman,D.J.,Mills,M.G.L.,Geffen,E.,Wayne,R.K.,1997.Amolecular

geneticanalysisofsocialstructure,dispersal,andinterpack

relation-shipsoftheAfricanwilddog(Lycaonpictus).Behav.Ecol.Sociobiol.

40,187–198.

Gomendio,M.,Malo,A.F.,Garde,J.,Roldan,E.R.,2007.Spermtraitsand

malefertilityinnaturalpopulations.Reprod.Suppl.134,19–29.

Graf,J.A.,Gusset,M.,Reid,C.,vanRensburg,S.J.,Slotow,R.,Somers,

M.J.,2006.Evolutionaryecologymeetswildlifemanagement:

artifi-cialgroupaugmentationinthere-introductionofendangeredAfrican

wilddogs(Lycaonpictus).Anim.Conserv.9,398–403.

Gusset,M.,Jakoby,O.,Muller,M.S.,Somers,M.J.,Slotow,R.,Grimm,V.,

2009.Dogsonthecatwalk:modellingre-introductionand

translo-cationofendangeredwilddogsinSouthAfrica.Biol.Conserv.142,

2774–2781.

Gusset,M.,Maddock,A.H.,Gunther,G.J.,Szykman,M.,Slotow,R.,

Wal-ters,M.,Somers,M.J., 2008.Conflictinghumaninterestsoverthe

re-introductionofendangeredwilddogsinSouthAfrica.Biodivers.

Conserv.17,83–101.

Gusset,M.,Slotow,R.,Somers,M.J.,2006.Dividedwefail:theimportance

ofsocialintegrationforthere-introductionofendangeredAfrican

wilddogs(Lycaonpictus).J.Zool.270,502–511.

Hermes,R.,Goritz,F.,Maltzan,J.,Blottner,S.,Proudfoot,J.,Fritsch,G.,

Fassbender,M.,Quest,M.,Hildebrandt,T.B.,2001.Establishmentof

assistedreproductiontechnologiesinfemaleandmaleAfricanwild

dogs(Lycaonpictus).J.Reprod.Fertil.Suppl.57,315–321.

Hofmeyr,M.,1997.TheAfricanwilddogsofMadikwe.Asuccessstory.

NorthWestParksBoard,Rustenburg,SouthAfrica,p.18.

Holt,W.V.,Lloyd,R.E.,2009.Artificialinseminationforthepropagationof

CANDES:thereality!Theriogenology71,228–235.

Howard,J.G.,Wildt,D.E.,2009.Approachesandefficacyofartificial

insem-inationinfelidsandmustelids.Theriogenology71,130–148.

Hynes,E.F., Rudd, C.D., Temple-Smith, P.D.,Sofronidis, G.,Paris, D.,

Shaw,G., Renfree,M.B.,2005. Matingsequence, dominanceand

paternitysuccessincaptivemaletammarwallabies.Reprod.130,

123–130.

Johnston,S.D.,Ward,D.,Lemon,J.,Gunn,I.,MacCallum,C.A.,Keeley,T.,

Blyde,D.,2007.StudiesofmalereproductionincaptiveAfricanwild

dogs(Lycaonpictus).Anim.Reprod.Sci.100,338–355.

Lasley,B.L.,Kirkpatrick,J.F.,1991.Monitoringovarian-functionincaptive

andfree-rangingwildlifebymeansofurinaryandfecalsteroids.J.Zoo.

WildlifeMed.22,23–31.

Maia,O.B.,Jacomo,A.T.A.,Bringel,B.A.,Kashivakura,C.K.,Oliveira,C.A.,

Teodoro,L.O.F.,Silveira,L.,daCosta,M.E.L.T.,Malta,M.C.C.,Furtado,

M.M.,Torres,N.M.,Mattos,P.S.R.,Viau,P.,Lima,T.F.G.,Morato,R.G.,

2008.Comparisonofserumhormonelevelsofcaptiveandfree-living

manedwolvesChrysocyonbrachyurus.Braz.J.Med.Biol.Res.41,

176–179.

Marsden, C.D.,Wayne,R.K.,Mable,B.K.,2012. Inferringtheancestry

ofAfricanwilddogsthatreturnedtotheSerengeti–Mara.Conserv.

Genet.13,525–533.

Mastromonaco,G.F.,Paris,M.C.J.,Krisher,R.L.,Paris,D.B.B.P.,2011.

Con-sensusdiscussiononartificialinseminationincompanionanimals,

non-domestic,andendangeredspecies(CANDES).In:Wheeler,M.B.

(Ed.),EmbryoTransferNewsletter.InternationalEmbryoTransfer

Society,Illinois,pp.10–12.

McCreery,E.K.,Robbins,R.L.,2001.Proximateexplanationsforfailedpack

formationinLycaonpictus.Behaviour138,1467–1479.

McNutt,J.W.,1996.Sex-biaseddispersalinAfricanwilddogs,Lycaon

pic-tus.Anim.Behav.52,1067–1077.

McNutt,J.W., Mills,M.G.L.,McCreery,K., Rasmussen,G.,Robbins,R.,

Woodroffe,R.,2008.Lycaonpictus,IUCN2009.In:IUCNRedListof

ThreatenedSpecies.

McNutt,J.W.,Silk,J.B.,2008.Pupproduction,sexratios,andsurvivorshipin

Africanwilddogs,Lycaonpictus.Behav.Ecol.Sociobiol.62,1061–1067.

Minter,L.J.,DeLiberto,T.J.,2008.Seasonalvariationinserumtestosterone,

testicularvolume,andsemencharacteristicsinthecoyote (Canis

latrans).Theriogenology69,946–952.

Monfort, S.L., Wasser, S.K.,Mashburn, K.L., Burke, M., Brewer, B.A.,

Creel,S.R.,1997.Steroidmetabolismandvalidationofnoninvasive

endocrinemonitoringintheAfricanwilddog(Lycaonpictus).ZooBiol

16,533–548.

Mouiex,C.,2006.Geneticverificationofmultiplepaternityintwo

free-rangingisolatedpopulationsofAfricanwild dogs(Lycaonpictus).

UniversityofPretoria,Pretoria.

Nagy,P.,Guillaume,D.,Daels,P.,2000.Seasonalityinmares.Anim.Reprod.

Sci.60,245–262.

Nöthling,J.O.,Bertschinger,H.J.,Broekhuzen,M.H.,Hemmelder,S.,

Nar-dini,R.,2002. QualityofAfricanwild dog(Lycaonpictus)semen

collectedbymeansofelectro-ejaculation.In:Dehnhard,M.(Ed.),4th

InternationalSymposiumonPhysiologyandBehaviourofWildand

ZooAnimals.BlackwellWissenschaftsverlag,Berlin,Germany,p.146.

Paris,D.B.,Taggart,D.A.,Shaw,G.,Temple-Smith,P.D.,Renfree,M.B.,2005.

Changesinsemenqualityandmorphologyofthereproductivetract

ofthemaletammarwallabyparallelseasonalbreedingactivityinthe

female.Reprod.130,367–378.

Paris,D.B.B.P.,Mastromonaco,G.F.,2009.ProceedingsoftheIETS2009

Post-ConferenceSymposium:ImplementationofArtificial

Insemi-nationinCANDES,7January2009,Foreword.Theriogenology71,

111–112.

Paris,M.,Schwarzenberger,F.,Thomas,R.,Jabbour,H.,Farstad,W.,Millar,

R.,2008.Developmentofregularindividualfaecalsamplecollections

fromgrouphousedAfricanwilddogs(Lycaonpictus)inaEuropeanZoo

setting:evidenceofoestruswithoutmalepresence.Reprod.Domest.

Anim.43,133–134.

Paris,M.C.J.,Mastromonaco,G.F.,Paris,D.B.B.P.,Krisher,R.L.,2007.A

per-spectiveontheroleofemergingtechnologiesforthepropagationof

companionanimals,non-domesticandendangeredspecies.Reprod.

Fert.Develop.19,iii–vii.

Preston,B.T.,Stevenson,I.R.,Pemberton,J.M.,Wilson,K.,2001.Dominant

ramsloseoutbyspermdepletion—awaningsuccessinsiringcounters

aram’shighscoreincompetitionforewes.Nature409,681–682.

Pukazhenthi,B.,Santymire,R.,Crosier,A.,Howard,J.,Wildt,D.E.,2007.

Challenges in cryopreserving endangered mammalspermatozoa:

morphologyandthevalueofacrosomalintegrityasmarkersof

cryo-survival.Soc.Reprod.Fertil.Suppl.65,433–446.

Robbins,R.L.,McCreery,E.K.,2000.Dominantfemalecannibalisminthe

Africanwilddog.Afr.J.Ecol.38,91–92.

Santymire,R.M.,Armstrong,D.M.,2009.Developmentofafield-friendly

techniqueforfecalsteroidextractionandstorageusingtheAfrican

wilddog(Lycaonpictus).Zoo.Biol.28,1–14.

Smithers,R.H.N.,1983.TheMammalsoftheSouthernAfricanSubregion.

UniversityofPretoria,Pretoria.

Spiering, P.A., Somers, M.J., Maldonado, J.E., Wildt, D.E., Gunther,

cooperativebreedingintheAfricanwilddog(Lycaonpictus).Behav.

Ecol.Sociobiol.64,583–592.

Thomassen,R.,Farstad,W.,2009.Artificialinseminationincanids:auseful

toolinbreedingandconservation.Theriogenology71,190–199.

Valdespino,C.,2007.Physiologicalconstraintsandlatitudinalbreeding

seasonintheCanidae.Physiol.Biochem.Zool.80,580–591.

vandeBildt,M.W.,Kuiken,T.,Visee,A.M.,Lema,S.,Fitzjohn,T.R.,

Oster-haus,A.D.,2002.DistemperoutbreakanditseffectonAfricanwilddog

conservation.Emerg.Infect.Dis.8,211–213.

vanHeerden,J.,1986.DiseaseandmortalityofcaptivewilddogsLycaon

pictus.S.Afr.J.WildRes.16,7–11.

vanHeerden,J.,Kuhn,F.,1985.Reproductionincaptivehuntingdogs

Lycaonpictus.S.Afr.J.WildRes.15,80–84.

vanHeerden,J.,Verster,R.,Penrith,M.L.,Espie,I.,1996.Diseaseand

mor-talityincaptivewilddogs(Lycaonpictus).J.S.Afr.Vet.Assoc.67,

141–145.

Velloso,A.L.,Wasser,S.K.,Monfort,S.L.,Dietz,J.M.,1998.Longitudinal

fecalsteroidexcretioninmanedwolves(Chrysocyonbrachyurus).Gen.

Comp.Endocr.112,96–107.

Verberkmoes,H.,2008.HistoricRegionalStudbook,10thedition.

Vlamings,B.,Pageat,P.,Schilder,M.,Berstchinger,H.,Paris,M.,2009.Cross

speciespheromoneapplication:ausefultooltominimizeaggression

ofAfricanwilddogs?In:7thInternationalConferenceonBehaviour,

PhysiologyandGeneticsofWildlife,Berlin,pp.23–24.

Vucetich,A.,Creel,S.,1999.Ecologicalinteractions,socialorganization,

andextinctionriskinAfricanwilddogs.Conserv.Biol.13,1172–1182.

Walker,S.L.,Waddell,W.T.,Goodrowe,K.L.,2002.Reproductiveendocrine

patterns in captive female and male red wolves (Canis rufus)

assessed by fecal and serum hormone analysis. Zoo. Biol. 21,

321–335.

Walker,W.H.,2009.Molecularmechanismsoftestosteroneactionin

sper-matogenesis.Steroids74,602–607.

Wildt,D.E.,Comizzoli,P.,Pukazhenthi,B.,Songsasen,N.,2010.Lessons

frombiodiversity—thevalueofnontraditionalspeciestoadvance

reproductivescience,conservation,andhumanhealth.Mol.Reprod.

Dev.77,397–409.

Wingfield,J.C.,Hegner,R.E.,Dufty,A.M.,Ball,G.F.,1990.Thechallenge

hypothesis—theoretical implications for patterns of testosterone

secretion,matingsystems,andbreedingstrategies.Am.Nat.136,

829–846.

Woodroffe,R.,Davies-Mostert,H.,Ginsberg,J.,Graf,J.,Leigh,K.,McCreery,

K.,Mills,G.,Pole,A.,Rasmussen,G.,Robbins,R.,Somers,M.,Szykman,

M.,2007.RatesandcausesofmortalityinendangeredAfricanwild

dogsLycaonpictus:lessonsformanagementandmonitoring.Oryx.

41,215–223.

Woodroffe,R.,Ginsberg,J.,1997.Pastandfuturecausesofwilddogs’

pop-ulationdecline.In:AfricanWildDogStatusSurveyandActionPlan.

TheIUCN/SSCCanidSpecialistGroup’s(Chapter4).

Young, A.J., Carlson, A.A., Monfort, S.L., Russell,A.F., Bennett, N.C.,

Clutton-Brock,T.,2006.Stressandthesuppressionofsubordinate

reproductionincooperativelybreedingmeerkats.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.