BUILDING PEACE BY SUPPORTING POST-CONFLICT

ELECTORAL PROCESSES

Thèse

Arsène Brice BADO

Doctorat en science politique

Philosophiae doctor (Ph.D.)

Québec, Canada

© Arsène Brice BADO, 2016

BUILDING PEACE BY SUPPORTING POST-CONFLICT

ELECTORAL PROCESSES

Thèse

Arsène Brice BADO

Sous la direction de :

Jonathan Paquin, directeur de recherche

Susan Hyde, codirectrice de recherche

iii Résumé

Les élections post-conflit ou élections de sortie de crise organisées sous l’égide de la communauté internationale en vue de rétablir la paix dans les pays sortant de violents conflits armés ont un bilan mixte caractérisé par le succès ou l’échec selon les cas. Ce bilan mitigé représente le problème principal auquel cette recherche tente de répondre à travers les questions suivantes : l'assistance électorale étrangère est-elle efficace comme outil de rétablissement de la paix dans les sociétés post-conflit? Qu'est ce qui détermine le succès ou l'échec des élections post-conflit à contribuer efficacement au rétablissement de la paix dans les sociétés déchirées par la guerre?

Pour résoudre cette problématique, cette thèse développe une théorie de l’assistance électorale en période post-conflit centrée sur les parties prenantes à la fois du conflit armé et du processus électoral. Cette théorie affirme que l'élément clé pour le succès des élections post-conflit dans le rétablissement de la paix est le renforcement de la capacité de négociation des parties prenantes à la fois dans le processus de paix et dans le processus électoral post-conflit. Dans les situations post-conflit, une assistance électorale qui se voudrait complète et efficace devra combiner à la fois le processus électoral et le processus de paix. L'assistance électorale sera inefficace si elle se concentre uniquement sur les aspects techniques du processus électoral visant à garantir des élections libres, transparentes et équitables. Pour être efficace, l'accent devra également être mis sur les facteurs supplémentaires qui peuvent empêcher la récurrence de la guerre, tels que l’habilité des individus et des groupes à négocier et à faire des compromis sur les grandes questions qui peuvent menacer le processus de paix.

De fait, même des élections transparentes comme celles de 1997 au Liberia saluées par la communauté internationale n’avaient pas réussi à établir des conditions suffisantes pour éviter la reprise des hostilités. C’est pourquoi, pour être efficace, l'assistance électorale dans les situations de post-conflit doit prendre une approche globale qui priorise l'éducation civique, la sensibilisation sur les droits et responsabilités des citoyens dans une société démocratique, le débat public sur les questions qui divisent, la participation politique, la formation au dialogue politique, et toute autre activité qui pourrait aider les différentes parties à renforcer leur capacité de négociation et de compromis. Une telle assistance électorale fera une contribution à la consolidation de la paix, même dans le contexte des élections imparfaites, comme celles qui se sont détenues en Sierra Leone en 2002 ou au Libéria en 2005.

Bien que la littérature sur l'assistance électorale n’ignore guère l'importance des parties prenantes aux processus électoraux post-conflit (K. Kumar, 1998, 2005), elle a fortement mis l'accent sur les mécanismes institutionnels. En effet, la recherche académique et professionnelle est abondante sur la réforme des lois électorales, la reforme constitutionnelle, et le développement des administrations électorales tels que les commissions électorales, ainsi que l’observation électorale et autres mécanismes de prévention de la fraude électorale, etc. (Carothers & Gloppen, 2007). En d'autres termes, les décideurs et les chercheurs ont attribué jusqu’à présent plus d'importance à la conception et au fonctionnement du cadre institutionnel et des procédures électorales. Cette thèse affirme qu’il est désormais temps de prendre en compte les participants eux-mêmes au processus électoral à travers des types d'assistance électorale qui favoriseraient leur capacité à participer à un débat pacifique et à trouver des compromis aux questions litigieuses. Cette approche plus globale de l'assistance électorale qui replace l’élection post-conflit dans le contexte plus englobant du processus de paix a l’avantage de transformer le processus électoral non pas seulement en une expérience d’élection de dirigeants légitimes, mais aussi, et surtout, en un processus au cours duquel les participants apprennent à régler leurs points de vue contradictoires à travers le débat politique dans un cadre institutionnel avec des moyens légaux et légitimes. Car, si le cadre institutionnel électoral est important, il reste que le résultat du processus électoral dépendra essentiellement de la volonté des participants à se conformer au cadre institutionnel et aux règles électorales.

iv Abstract

The record of the international community is mixed regarding support of post-conflict electoral processes developed to consolidate peace in countries emerging from internal armed conflict. It has constituted the empirical puzzle this dissertation strives to explore through the following questions: Is foreign electoral assistance effective as a tool for peace making in post-conflict societies? What determines the success or failure of electoral assistance as a tool for peace making in war-torn societies? In this dissertation, I developed and implemented an actors-centered, post-conflict electoral assistance theory that proposes ways to achieving peace consolidation in countries torn by civil war. I have argued that the key element for the success of post conflict elections in restoring peace is the extent to which electoral assistance builds the negotiation capacity of stakeholders in both the peace process as well as in the post-conflict electoral process. It is of vital importance that in post-conflict settings, comprehensive and effective electoral assistance must combine both the electoral process and the peace process. Electoral assistance will be unsuccessful if it focuses only on the technical aspects of the electoral process to ensure free and fair elections.

To be effective in post-conflict countries, electoral assistance must contribute to establishing a durable peace by facilitating dialogue between former parties to the conflict and other societal groups, encouraging negotiation, and emphasizing compromise. Consequently, in post-conflict settings, an electoral process should not focus solely on strengthening electoral institutions that can guarantee free and fair elections. Emphasis should also be placed on additional factors that can prevent the recurrence of war, such as the abilities of individuals and groups to negotiate and reach compromises over major issues that may threaten the peace process. Even internationally acclaimed free and fair post-conflict elections, such as the one that took place in Liberia in 1997, do not necessarily prevent further war. From this standpoint, in order to be effective, electoral assistance in post-conflict settings must take a comprehensive approach that prioritizes such activities as civic education, awareness programs about citizens’ rights and responsibilities in a democratic society, public debate on divided issues, political participation, skills training, and any other activity that might help various parties in building their capacity for negotiation and compromise. Foreign electoral assistance that encompasses such issues will make a substantial contribution to consolidating the peace even in the context of imperfect elections, like those held in Sierra Leone in 2002 or Liberia in 2005.

While the literature regarding electoral assistance in post-conflict situations does not ignore the importance of various stakeholders (K. Kumar, 1998, 2005), it has heavily focused on institutional mechanisms such as the reforms of laws and constitutions as well as on the development of electoral administrations, including electoral commissions, offices of voter registration, polling stations, election monitoring, etc. (Carothers & Gloppen, 2007). In other words, policy-makers and scholars have ascribed more importance to the design and enforcement of the framework and rules of the electoral process than to the assistance to participants in the post-conflict electoral process.

I propose that now is the time to take into account the participants themselves through the above mentioned types of electoral assistance activities that would foster their ability to engage in peaceful debate over contested issues in an effort to find compromise. This more comprehensive form of electoral assistance can transform the electoral process to be not only an experience of the election of legitimate leaders, but also, and more importantly, to be a time during which participants learn to settle their conflicting points of view through debate, compromise and ultimately, through ballots and not through bullets. For, if the total framework of the process matters, the outcome of the process will rely on how participants comply with the rules.

v Table of Contents

RÉSUMÉ ... III

ABSTRACT ... IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... V

LIST OF TABLES ... VIII

LIST OF FIGURES ... IX

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS... X

DEDICATION ... XII

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... XIII

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION: SUPPORTING POST-CONFLICT ELECTIONS AND

MAKING PEACE ... 1

CHAPTER 2: CURRENT STATUS AND CHALLENGES OF FOREIGN ELECTORAL ASSISTANCE IN PEACEBUILDING ... 17

2.0.INTRODUCTION ... 17

2.1.APPRAISING THE NOTIONS AND PRACTICES OF CONTEMPORARY ELECTORAL ASSISTANCE ... 18

2.1.1. Defining Democracy Promotion ... 19

2.1.2. Defining Electoral Assistance ... 24

2.1.3. From ‘Election Assistance’ to ‘Electoral Assistance’ – a Gap Between Theory and Practice ... 25

2.2.PROVISION OF ELECTORAL ASSISTANCE ... 27

2.2.1. Bilateral Provision of Electoral Assistance ... 28

2.2.2. Multilateral Provision of Electoral Assistance ... 33

2.2.3. Provision of Electoral Assistance within Peacekeeping Operations ... 38

2.2.4. Problems of Provision of Electoral Assistance ... 39

Problems of Perception ... 40

Problems of Cooperation ... 41

Problem of Principal-Agent Relationship ... 43

2.3.CONCLUSION ... 44

CHAPTER 3: AN ACTORS-CENTERED POST-CONFLICT ELECTORAL ASSISTANCE THEORY ... 47

3.0.INTRODUCTION ... 47

3.1.THE ACTORS-CENTERED POST-CONFLICT ELECTORAL ASSISTANCE ARGUMENT ... 48

3.2.STAKEHOLDERS’PEACEMAKING AND ELECTORAL CAPABILITY BUILDING ... 56

3.3.CAPACITY BUILDING OF ELECTORAL INSTITUTIONS ... 59

3.4.METHODOLOGY ... 60

3.4.1. A multiple case study approach ... 60

3.4.2. Data Collection ... 62

3.4.3. Method of analysis ... 65

3.5.CONCLUSION ... 66

CHAPTER 4: PEACE PROCESSES AS PREREQUISITES FOR SUCCESSFUL IMPLEMENTATION OF POST-CONFLICT ELECTORAL ASSISTANCE ... 67

4.0.INTRODUCTION ... 67

4.1.SIERRA LEONE:THE PEACE PROCESS LEADING TO THE 2002 POST-CONFLICT ELECTIONS ... 69

4.1.1. Explaining the civil war in Sierra Leone, 1991-2002 ... 69

4.1.2. Negotiating and implementing peace agreements in Sierra Leone: Building the skills for negotiation and compromise ... 74

vi

4.1.3. The impact of the peace process on the 2002 Sierra Leone’s post-conflict electoral

process ... 87

4.2.LIBERIA: THE PEACE PROCESSES LEADING TO THE POST-CONFLICT ELECTIONS OF 1997 AND 2005 ... 89

4.2.1. The two Liberian civil wars, 1989-1997 and 1999-2003 ... 89

4.2.2. Negotiating the peace accords during the first Liberian civil war... 94

4.2.3. Impact of the Liberian first peace process on the 1997 post-conflict elections ... 104

4.2.4. The second Liberian peace process leading to the 2005 post-conflict elections .... 105

4.2.5. The impact of the second Liberian peace process on the second post-conflict electoral process of 2005 ... 109

4.3.CÔTE D’IVOIRE: THE PEACE PROCESSES LEADING TO THE POST-CONFLICT ELECTIONS OF 2010... 111

4.3.1. The two civil wars in Côte d’Ivoire, 2002-2007, and 2010-211... 111

4.3.2. Negotiating and implementing the peace process in Côte d’Ivoire ... 116

4.3.3. Impact of the peace process on the 2010 post-conflict elections ... 123

4.4.CONCLUSION ... 125

CHAPTER 5: TRAINING THE PLAYERS: ASSISTANCE TO STAKEHOLDERS’ ELECTORAL CAPABILITY BUILDING ... 129

5.0.INTRODUCTION ... 129

5.1.IDENTIFICATION OF PLAYERS WHO MATTER IN A POST-CONFLICT ELECTORAL PROCESS ... 130

5.2.FROM VOTER EDUCATION TO ELECTORAL AND CIVIC EDUCATION: TRANSFORMING THE ELECTORAL PROCESS INTO A PEACE CONSOLIDATION PROCESS ... 135

5.3.POLITICAL PARTIES ... 139

5.4.CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS ... 147

5.5.THE ELECTORATE ... 156

5.6.FORMER ARMED GROUPS AND EX-COMBATANTS ... 161

5.7.CONCLUSION ... 167

CHAPTER 6: FRAMING AND IMPLEMENTING THE RULES OF THE GAME ... 171

6.0.INTRODUCTION ... 171

6.1.BUILDING LEGAL FRAMEWORKS FOR POST-CONFLICT ELECTORAL PROCESSES ... 174

6.1.1. Electoral Assistance for Reforming Post-Conflict Electoral Laws ... 174

6.1.2. Electoral Systems ... 188

6.2.DESIGNING AND STRENGTHENING ELECTION MANAGEMENT BODIES FOR POST-CONFLICT ELECTORAL PROCESSES ... 192

6.2.1. Designing EMBs for Post-Conflict Electoral Processes ... 193

6.2.2. Operational capacity building of EMBs ... 200

6.2.3. Capacity of EMBs to Administer the Post-Conflict Electoral Processes ... 204

Voter Registration ... 204

Campaign and Media Regulation ... 205

Polling Operations, Election Results, and Complaints ... 208

6.3.CONCLUSION ... 215

CHAPTER 7: CONCLUSION ... 218

7.1.THE FINDINGS ... 218

With Regard to the Assistance to Electoral Stakeholders ... 219

With Regard to the Assistance to Electoral Institutions ... 223

7.2.POLICY IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 224

vii

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 228

ANNEXES ... 240

ANNEX 1:STANDARDIZED QUESTIONS FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF CASES STUDIED ... 240

viii List of Tables

TABLE 1:DEMOCRACY PROMOTION COMPONENTS ... 21

TABLE 2:DIFFERENT APPROACHES TO DEMOCRACY PROMOTION ... 22

TABLE 3:COMPONENTS OF INTERNATIONAL ELECTORAL ASSISTANCE IN POST-CONFLICT SETTINGS ... 25

TABLE 4:HYPOTHESES ... 55

TABLE 5:CASE SELECTION ... 61

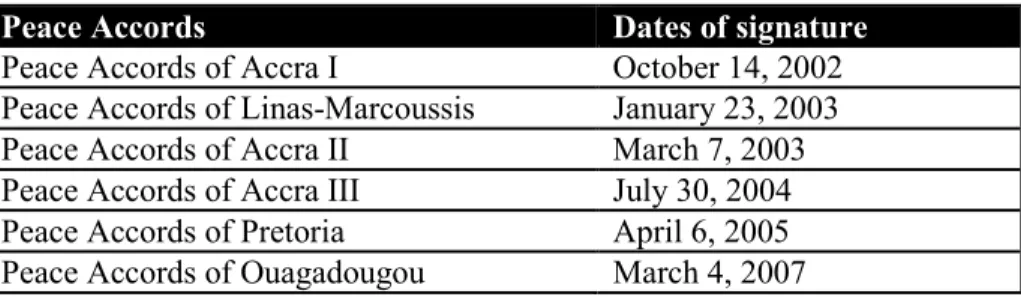

TABLE 6:ACCORDS SIGNED DURING THE FIRST LIBERIAN PEACE PROCESS ... 101

TABLE 7:PEACE ACCORDS SIGNED DURING THE IVORIAN PEACE PROCESS ... 120

TABLE 8:ELECTORAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK:RELEVANT OBLIGATIONS AND CONSTITUENT PARTS OF THE ELECTION ... 185

ix List of Figures

x List of Abbreviations

AFL: Armed Forces of Liberia

AFRC: Armed Forces Revolutionary Council

ASAPSU: Association de Soutien à l'Auto-Promotion Sanitaire Urbaine ASEAN: Association of Southeast Asian Nations

AU: African Union

CDF: Civil Defense Force (Kamajors)

CERAP: Centre de Recherche et d’Action pour la Paix CPA: Comprehensive Peace Agreement

COFEMCI: Coordination of the Women of Cote d’Ivoire for the Elections and Post-Crisis Reconstruction

CSCI: Convention de la Société Civile Ivoirienne

DDR: Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration program

DFID: Department of International Development of the United Kingdom E.C.: European Commission

ECOMOG: ECOWAS Cease-Fire Monitoring Group ECOWAS: Economic Community of West African States

EIDHR: European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights ERL 2004: The Liberian Electoral Reform Law of 2004

EU: European Union

EU-EOM: European Union Election Observation Mission FN: New Forces

FPI: Front Populaire Ivoirien ICG: International Crisis Group

IDEA: International Institute for Democracy and Election Assistance IDPs: Internally Displaced Persons

IEC: Independent Electoral Commission IECOM: Independent Elections Commission

IFES: International Foundation for Election Systems IRC: Inter Religious Council

IRCSL: Inter-Religious Council of Sierra Leone IRI: International Republican Institute LEON: Liberia Election Observation Network LPA: Lomé Peace Accord

LPC: Liberia Peace Council

LURD: Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy MODEL: Movement for Democracy in Liberia

NCCP: National Coordinating Committee for Peace

NCDHR: National Commission for Democracy and Human Rights – Sierra Leone NDI: National Democratic Institute

NEC: National Election Commission

NED: National Endowment for Democracy NGO: Non-Governmental Organization

xi NPFL: National Patriotic Front of Liberia NPP: National Patriotic Party

OAS: Organization of American States OAU: Organization of African Unity OPA: Ouagadougou Political Agreement PDCI: Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire RDR: Rassemblement des Républicains

RHDP: Rassemblement des Houphouetistes pour la Démocratie et la paix RTI: Radio Télévision Ivoirienne

RUF: Revolutionary United Front RUFP: Revolutionary United Front Party SLA: Sierra Leone Army

SLAUW: Sierra Leone Association of University Women SLPP: Sierra Leone People’s Party

SRSG: Special Representative of the Secretary General of the United Nations ULIMO: United Liberation Movement of Liberia for Democracy

UN: United Nations

UNAMSIL: United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone UNDP: United Nations Development Program UNEAD: United Nations Electoral Assistance Division UNMIL: United Nations Mission in Liberia

UNOCI: United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire UNOMIL: United Nations Observation Mission in Liberia UNSC: United Nations Security Council

USAID: United States Agency for International Development WANEP-CI: West Africa Network for Peace building - Côte d’Ivoire

xii Dedication

I dedicate this dissertation in loving memory to my brother Léonard Bado who passed away during my second year of doctoral studies.

xiii Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge with appreciation, the many individuals whose actions and support made possible this doctoral research. In particular, I owe a special debt of gratitude to Professor Jonathan Paquin of Université Laval and Professor Susan Hyde of Yale University who co-advised this research and played key roles in improving all aspects of my dissertation. I am deeply grateful to them for their expertise, guidance, and comments as well as for providing me with the opportunity for candid discussions with them; discussions which substantially helped to strengthen and clarify the argument in this dissertation. Professors François Gélineau, Marie Brossier, and Annessa Kimbal who are the other members of my dissertation committee, have also provided valuable comments and suggestions in defining the research project.

Beyond the dissertation committee, I received helpful comments during my time visiting at Yale University in 2014-2015, from faculty members, Prof. Bruce Russetts, Prof. Kate Baldwin, Prof. Nuno Monteiro, and Prof. Stathis Kalyvas. Yale graduate students also made insightful comments during the Africa Working Group Seminars; I especially mention Pia Rafler, Itumeleng Makgetla, Kevin Russell, and Gautam Nair. Prof. Andrew Bennett and Prof. Matthew Carnes from Georgetown University provided very helpful comments and suggestions at the early stage of the research project. Prof. Carnes was a mentor who helped me to navigate through my doctoral research and also to define a clear strategy for academic publications.

Additionally, this research has benefited from comments from several other individuals. I particularly cite the following persons: Mr. Jeffrey Fischer from Creative Associates International; Mr. Herbert Loret from the Department of Peace Keeping Operations at the United Nations in New York City; Mrs. Sehen Hirpo from the Electoral Assistance Division of the Department of Political Affairs at the United Nations in New York City; Mr. John L. Hirsh from the International Peace Institute in New York and former United States Ambassador to the Republic of Sierra Leone; Mr. Gamaliel Ndaruzaniye from the Department of Political Affairs of the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire; Dr. Christophe Kouamé from the National Coordination of the Convention of Ivorian Civil Society; Mr. Antoine Adou from the Independent Electoral Commission of Cote d’Ivoire; Mr. Fatorma Fah-Bundeh from the National Electoral Commission of Sierra Leone; Elizabeth Plachta and Claire Kaye from the Carter Center; and Rushdi Nackerdien and Staffan Darnolf from IFES.

My mother Pauline Kandiel and my sisters and brothers have been very supportive and were always eager to hear about my progress when I was able to contact them in Burkina Faso.

Carolyn M. Beaudin deserves special thanks for having proofread the entire dissertation. I am deeply thankful to her for her expertise and friendship. I am blessed by her tremendous support. She also shared my joys and anxieties during the process of completing this dissertation. Robert McGovern also proofread my dissertation. I am grateful to him for his time, expertise, and friendship. Other people, too numerous to mention by name, corrected, commented upon or made suggestions with respect to some sections of the dissertation. I am thankful to all of them for their generosity and dedication.

xiv

I am also thankful to my fellow graduate students in political science at Laval. Nicolas Falomir and Mamadou Lamine Sarr shared my joys and hardships during my years studying at Université Laval. I wish them all the best in their own doctoral research.

The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C., provided me with a unique opportunity to discuss the results of my research with scholars and policymakers at the U.S. Department of States, the U.S. House Subcommittee on Africa, Creative Associates International, the United States Institute of Peace, and at SAIS Johns Hopkins University. I am deeply thankful to the team of the Africa Program at the Wilson Center, and especially to Dr. Monde Muyangwa, Elizabath Ramey, Grace Chesson, and Jeremy Gaines. I am deeply grateful to the Jesuit community at the Gonzaga College High School for its warm welcome during my stay in Washington, D.C.

The Saint Thomas More Catholic Center and Chapel at Yale University offered me hospitality during my time researching at Yale University. I felt especially welcome at Saint Thomas More thanks to the Chaplain, Fr. Robert L Beloin, and the entire Catholic community at Saint Thomas More. I have been blessed by having lived with such great human beings and faithful people.

I would have not been able to study in Quebec without the support from the Jesuit community at Rue Dauphine in Quebec City, and from the Jesuit Provinces of French Canada and West Africa. Thank you very much to my fellow Jesuits for what we have shared together. This research was made also possible by the following awarded fellowships and grants: Doctoral Fellowship of the Research Chair on Democracy and Parliamentary Institutions of Université Laval, the Georges-Henry Levesque Fellowship Award by the Faculty of Social Sciences of Laval, the Field Research Grant by the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the scholarship of Presses de l’Université Laval, the Fund Jean-Pierre Derriennic of the Department of Political Science of Université Laval, the Merit Scholarship of the Department of Political Science of Université Laval, and the Southern Voices Network Scholarship of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Writing a dissertation is not only an academic exercise, but also a human experience. I am deeply grateful to all those whom I met during this journey, and who helped me to deepen and improve my thinking.

1

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION: SUPPORTING POST-CONFLICT

ELECTIONS AND MAKING PEACE

Electoral assistance and democracy promotion activities have become central components of bilateral and multilateral aid over the last two decades. After the conclusion of the Cold War, governments in Europe and North America rushed to support the reintroduction of multiparty politics in states that had seen their political climates distorted by the rivalry between the Soviet Union and the United States. In this context, electoral assistance has emerged as one of the main instruments used by the international community, with the aim of putting an end to internal conflicts and consolidating the peace process in post-civil conflict situations. Since the end of the Cold War, the electoral component of peace operations has gained much prominence. In fact, at the present time, it is hard to find a peacekeeping operation or peace agreement in a situation of internal conflict that does not prioritize the holding of elections as an essential element of the peace process. This dynamic captures the importance of elections in post-conflict situations and explains why foreign electoral assistance and other democracy promotion activities have gained much interest in International Relations and Peace Studies.

Electoral assistance providers, however, have a mixed record in supporting electoral processes as a tool for peace making in post-conflict societies. In some cases, like Sierra Leone in 2002 or Liberia in 2005, internationally assisted post-conflict elections returned those countries to normalcy. In other cases, like in Côte d’Ivoire in 2010 or Liberia in 1997, externally supported election processes failed in their efforts to prevent these countries backsliding into conflict. This mixed record generates a critical set of questions: is foreign electoral assistance effective as a tool for peace making in post-conflict societies? And subsequently, what determines the success or failure of electoral assistance as a tool for peace making in war-torn societies? The chapters that follow will work to resolve these questions.

2

I argue that, if electoral assistance is solely focused on the delivery of a legitimate electoral process in a conflict setting, it will be ineffective. To be effective in post-conflict countries, electoral assistance must also contribute to establishing a durable peace by facilitating dialogue between former combatants and other societal groups, encouraging negotiation, and emphasizing compromise. Consequently, in conflict settings, an electoral process should focus not only on strengthening electoral institutions that can guarantee free and fair elections. Emphasis should also be placed on additional factors that can prevent the recurrence of war, such as the abilities of individuals and groups to negotiate and make compromises over major issues that may threaten the peace process. Even internationally acclaimed free and fair post-conflict elections, such as the one that took place in Liberia in 1997, do not necessarily prevent further war. From this standpoint, in order to be effective, electoral assistance in post-conflict settings must take a comprehensive approach that prioritizes civic education, awareness programs about citizens’ rights and responsibilities in a democratic society, public debate on divided issues, political participation, skills training, and any other activity that might help various parties build their capacity for negotiation and compromise. Such foreign electoral assistance will make a contribution to consolidating the peace even in the context of imperfect elections, like those held in Sierra Leone in 2002 or Liberia in 2005.

While the literature regarding electoral assistance in post-conflict situations does not ignore the importance of various stakeholders (K. Kumar, 1998, 2005), it has heavily focused on institutional mechanisms such as the reforms of laws and constitutions and on the development of electoral administrations, including electoral commissions, offices of voter registration, polling stations, election monitoring, etc. (Carothers, 2009; Carothers & Gloppen, 2007). In other words, policy-makers and scholars have ascribed more importance to the design and enforcement of the framework and rules of the electoral process. I propose that now is the time to take into account the participants themselves through the above types of electoral assistance activities that would foster their ability to engage in peaceful debate over contested issues and find compromise. This more comprehensive form of electoral assistance can transform the electoral process to be not

3

only an experience of the election of legitimate leaders, but also, and more importantly, to be a time during which participants learn to settle their conflicting points of view through debate, compromise and ultimately, through ballots and not through bullets. For, if the total framework of the process matters, the outcome of the process will rely on how participants comply with the rules.

To demonstrate my argument, I assess how electoral assistance programs and activities have empowered both institutions and citizens across four post-conflict elections that took place in Sierra Leone during 2002, Liberia in 1997 and 2005, and in Cote d’Ivoire during 2010.

I show that in the post-conflict elections of Sierra Leone during 2002, and in Liberia in 2005, an emphasis on capacity building was an important determinant of the success of electoral assistance, in terms of contributing to the consolidation of peace. In these two cases, foreign electoral assistance programs gave an important place to facilitating public debate on divided issues in addition to the design and implementation of institutional and legal procedures. Foreign electoral assistance programming also helped formerly armed groups to participate in the political process, and fostered the emergence of a civil society as a domestic third-party between the former warring parties. In both Liberia in 2005 and Sierra Leone in 2002, targeting efforts towards societal actors, rather than simply towards electoral rules and institution building, electoral assistance programs enabled improved outcomes.

Conversely, in the case of post-conflict elections held in Liberia in 1997 and in Cote d’Ivoire during 2010, an insufficient focus on the capacity building of electoral stakeholders contributed to the resumption of hostilities. In these two post-conflict elections, foreign assistance was focused on the consolidation of normative and institutional procedures. Priorities included the reform of constitutional and electoral laws, efforts to support the functioning of electoral commissions, the establishment of offices for voter registration, polling stations, and the provision of electoral monitoring. The focus is

4

on a set of legal, administrative and regulatory mechanisms that aimed at ensuring the holding of free, fair and credible elections. While these procedures are certainly important, objective, measurable, and can enable the successful holding of elections in due course, they are not sufficient to ensure peace, even after “good elections”.

I do not understate the importance of institutions, but I argue that the capacity building of both institutions and participants must be prioritized in foreign electoral assistance programs to maximize their effectiveness. The former are quickly fixed, less time consuming and lend themselves to clearer assessment, while the latter are value-oriented and require longer term commitment, additional funds and can be more difficult to evaluate. This may explain why electoral assistance providers are less committed to educational and training activities that foster the capacity for negotiation and compromise than they are to activities that target institutions. But democracy is not only the implementation of institutional procedures; it is also built on the values that inform citizens’ preferences and participation. At this stage of the argument, the question that emerges is this: What constitutes effective electoral assistance in post-conflict settings? The answer to this question frames the entire argument of this dissertation.

Electoral assistance in post-conflict settings

Explaining the effect of electoral assistance in peace making requires a better understanding of the concept of electoral assistance in post-conflict settings. Yet, the notion of electoral assistance is itself a puzzle since it is highly complex and elastic; it has different meanings according to different providers, be they state or non-state organizations. Moreover, in conflict-affected societies, electoral assistance tends to be labeled differently under the broad categories of democracy promotion or development assistance. Indeed, the expectations placed on post-conflict elections are often too high, as they are expected to consolidate peace, legitimate elected leaders, and to create conditions for reconstruction and development (K. Kumar, 1998). To add to this complexity, The United Nations Department of Political Affairs (UNDPA) states that there is no universal

5

model of electoral assistance and that programs are tailored according to the specific needs of each requesting member state (UNDPA, 2013).

The UNDPA, however, identifies three dimensions of electoral assistance: technical assistance which “covers a wide range of short and long-term expertise provided to national authorities in charge of administering elections in their country”; political assistance through election observation and other assessments including the validation of the integrity of an electoral process; and in some cases, the organization or the supervision of elections by a third-party entrusted with the full responsibility of organizing elections in a state.

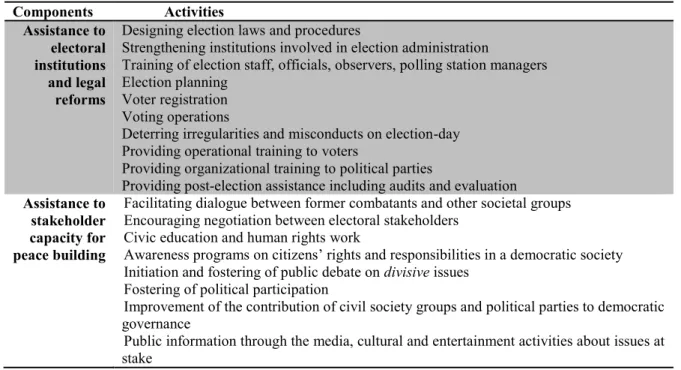

From this perspective, I define the notion of post-conflict electoral assistance as referring to any activity undertaken purposely to support electoral laws, institutions, and stakeholders in order to impact both the electoral and peace processes. I construe post-conflict electoral assistance through the two following broad components: assistance to electoral institutions and laws, and assistance to stakeholders’ capacity for peace building. I describe briefly each of the two components below:

The first component, assistance to electoral institutions and laws, is concerned with establishing a legitimate electoral process that is able to deliver a free and fair election, in accordance with international standards. In order to achieve this goal, the variety of electoral support provided includes the design and implementation of election laws, systems, institutions and procedures; strengthening of institutions involved in election administration; training of election staff, officials, observers, and polling station managers; election planning; voter registration; operational training of voters; organizational training of political parties; voting operations; deterring of irregularities and misconducts on election-day; and post-election assistance including audits and evaluation. These activities are common in electoral assistance provided not only to post-conflict elections, but also to routine elections in developing countries (Reilly, 2003; Tuccinardi, Guerin, Bargiacchi, & Maguire, 2008; Zeeuw, 2005).

6

The second component, assistance to stakeholders’ capacity for peace building, seeks to strengthen relevant stakeholders’ capacity for negotiation and compromise over divided issues. This objective is achieved through the following assistance programs and activities: facilitation of dialogue between former combatants and other societal groups; encouragement of negotiation between electoral stakeholders; civic education and human rights; awareness programs about citizens’ rights and responsibilities in a democratic society; initiation and encouragement for public debate on divided issues; fostering of political participation; trainings, public information through the media, cultural and entertainment activities, and any other assistance that might help various parties including the entire population to engage in peaceful debate and learning about issues at stake.

In this dissertation, I argue that in post-conflict settings, foreign electoral assistance should not only be concerned with guaranteeing free and fair post-conflict elections, but also with building participants’ capacity for negotiation, public debate and compromise over divided issues. This comprehensive approach to electoral assistance enables the post-conflict electoral process itself to be transformed into a peace process. This dynamic makes post-conflicts markedly different from routine elections in peacetime. It is important to ask: How are post-conflict electoral processes different from other electoral processes? In this dissertation, I contend that a failure to adequately adapt electoral assistance programming to reflect the specific needs of post-conflict environments explains, in part, the ineffectiveness of electoral assistance in many post-conflict settings.

Post-conflict electoral processes

I define a post-conflict electoral process as the first electoral process held after a major violent conflict, usually as a provision of a peace agreement, which makes post-conflict elections an integral part of the peace process, if not the high point of the peace process. The context of conflict and peace-making in which these electoral processes take place distinguishes them from elections held in peaceful times. I argue that post-conflict

7

electoral processes should be designed and implemented accordingly, and that post-conflict elections should only be held if, during the current electoral cycle, electoral assistance programs have enabled relevant participants to learn to compromise peacefully over the issues at stake. In addition, as the objectives of post-conflict elections extend beyond the competitive selection of representatives and towards the consolidation of peace, these post-conflict electoral processes, they should be viewed differently than elections that take place in other settings. Krishna Kumar (1998) has identified three main objectives of post-conflict elections to which I add a fourth objective, which I outline below:

The first is “to transfer power to a democratically installed government that enjoys national and international legitimacy and is able to start rebuilding the country” (K. Kumar, 1998, p. 6). This primary objective is certainly important; however, it is insufficient in guaranteeing peaceful post-election political order even after free, fair and well-organized elections. Here lies the difference between normal or routine elections in a peaceful period and post-conflict elections after a violent civil conflict. The latter includes the following objectives that go beyond the selection of legitimate leaders.

The second objective of post-conflict elections is “to initiate and consolidate the democratization process in the country” (K. Kumar, 1998, p. 6). While democratization cannot be achieved in a single election, a free and fair election may constitute an important step toward democratization.

The third objective is “to promote reconciliation between the parties that were formerly at war with each other” (K. Kumar, 1998, p. 7). I argue that for the post-conflict electoral process to be effective in peace making, reconciliation activities and commitments should be highlighted during the electoral process and not only in the post-election era. The initiation of such activities before the post-elections constitutes a positive signaling of the willingness, or at least the intentions of conflicting parties for peace.

8

The fourth objective that I suggest is to foster dialogue and compromise building. I argue that it is critical that stakeholders and especially former warring parties learn through the post-conflict electoral process how to dialogue, and how to broker compromise through a democratic institutional framework. It is of much importance that the post-conflict electoral process introduces stakeholders to the art of democratic compromise by reinstating a sense of citizenship, of responsibilities and duties between government and governed, as well as the importance of voicing grievance through a political and institutional framework, rather than through the extra-institutional framework that is civil war. This highlights the importance of civic education activities during the electoral cycle in order to help electoral stakeholders to learn and embody peaceful ways of conflict management and respect of human rights. This allows the entire electoral process to foster and build the trust between stakeholders.

Thus, these four objectives and the context of transition from war to peace, make post-conflict electoral processes very specific with high prospects for peace for which legitimately elected leaders matter as well as the termination of the conflict. However, do post-conflict elections bring peace?

Elections and peace

The correlation between post-conflict elections and peacemaking, and more broadly between elections and peace is hotly debated (Fischer, 2002; Wai, 2011). This debate is part of a larger scholarly debate on democracy and peace (Buchan, 2002; B. Russett, Layne, Spiro, & Doyle, 1995; B. M. Russett, 1993). I will address different aspects of this debate at different stages of the development of the argument of this dissertation. So I limit myself here to discussing some elements of this controversy to better situate the issue of supporting post-conflict elections in order to resolve or to mitigate internal political violence.

9

One has to acknowledge the existence of a paradox in the use of elections in peace building strategies, since there is no doubt that elections can ignite or exacerbate conflicts in divided societies (Wai, 2011). Elections are about power and who will control it and lead the community. Elections are about choosing between rivals and deciding who the winner is and who is the loser. In such situations, an election may act as the perfect trigger of conflict and political violence. Divided societies, especially those emerging from conflict are therefore “dangerous places” for holding elections (Gillies, 2011).

This paradox has been reinforced by the existence of several cases where elections have aggravated societal divisions and political violence instead of resolving them. In the last two decades, internationally assisted elections have sometimes failed to strengthen peace in African countries that have been enmeshed in conflict, such as Angola, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and Côte d’Ivoire, among others (see Collier, 2010; European Commission, UNDP, & International IDEA, 2011a; Fischer, 2002, pp. 11-20; Khadigala, 2010, pp. 5-6; Maley, Sampford, & Thakur, 2003; Schwarzmantel, 2011; Sisk & Reynolds, 1998). Election-related conflicts are not specific to Africa. They have been observed in European countries such as Bosnia and Herzegovina (see Fischer, 2002); in Asian countries such as Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines and Thailand (see UNDP, 2011); and in the Americas such as in Haiti, Jamaica, Venezuela, Mexico, etc. (see Altman & Perez-Linan, 2002). How can one resolve, or at least understand this paradox of elections that can trigger violence instead of consolidating peace?

This dissertation contributes to the literature by considering elections in general, and post-conflict elections in particular, as alternatives to violent conflict. A careful analysis of electoral violence reveals that it is not the elections themselves that generate violence. What produces electoral violence is the behavior of political stakeholders that seek to impact the electoral process through violent and unlawful means. Or as, Fisher explains, “it is when an electoral process is perceived as unfair, unresponsive, or corrupt that its political legitimacy is compromised and stakeholders are motivated to go outside the

10

established norms to achieve their objectives” (Fischer, 2002, p. 2). That is why the core argument of this dissertation contends that electoral assistance should not be concentrated only in the strengthening of electoral institutions, but rather it should seriously take into account the strengthening of stakeholders’ electoral capacity, in order to deter misconduct, or the use of other violent and illicit means that might negatively affect the electoral process. This approach constitutes a better way to resolve the paradox of elections, which can lead to conflict instead of peace under unfavorable conditions.

From that standpoint, this dissertation holds that, elections, and more broadly, liberal democracy, is underpinned by a culture incarnated into a wide variety of institutional norms and procedures that help to transform internal conflicts. Democracy is about a process of managing conflicting interests through predefined and commonly agreed values, behaviors, rules and procedures. Elections are a key element of that process, and “should sound the death knell to political violence” (Collier, 2010, p. 2). Furthermore, after a major intrastate conflict, it is difficult to imagine means other than elections to decide whom, among former enemies, might govern the state. This explains why the international community, and especially major states, is more inclined to relate electoral processes to peace processes, and why electoral assistance has become a critical component of peace settlement process and political order reconstitution.

Yet, although they play a key role in peace making, internationally assisted post-conflict elections are not a panacea for the re-establishment of peace and for the return to normalcy after violent internal conflicts. The global context in which post-conflict elections take place matters, both for the determination of the appropriate types of electoral assistance, and for the outcome of the electoral process. For instance, the security environment is critical for the holding of post-conflict elections. In post-conflict settings, electoral assistance is usually provided within a peacekeeping operation whose role is important in ensuring minimal security through the presence of foreign military and police forces, and through the training of domestic security forces and the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of former combatants.

11

The post-conflict economic setting also matters (Flores & Nooruddin, 2009). Though economic reconstruction and development after a major civil war cannot be achieved in the short-term, the beginning of reconstruction or at least the possibility for the population to expect some signs of improvement in the near future constitutes a critical asset that usually helps former warring groups and the entire population to turn their backs to war and to build confidence in the future and initiate an electoral process, as I will later demonstrate through an exploration of case studies from electoral processes in Serra Leone, Liberia, and Cote d’Ivoire.

The nature of the conflict, its intensity and duration, the identity of warring groups, the quality of the peace agreement, and whether there is a clear winner or not, each structure different parameters that affect the post-conflict setting and the post-conflict electoral process.

The above-mentioned issues, be they related to the security, the economy, or other grievances, must find an important place in the post-conflict electoral process. In Sierra Leone, Liberia and Cote d’Ivoire, the major issues at stake, concerning the conflict and the return to a peaceful sociopolitical order, were raised during the electoral process. The latter provided opportunities for political parties and their candidates - as well as civil society groups and other election stakeholders - to engage in public debates on divided issues and policies. This represents both a strength and a weakness in terms of the ability for post-conflict electoral processes to secure a durable peace. Indeed, the power of a post-post-conflict electoral process is found in its ability to channel challengers and their conflicting interests into an institutional framework, in which the constituency as the ultimate source of legitimacy chooses between the competing options. This is how post-conflict electoral processes give birth to peaceful sociopolitical order, with newly elected and legitimate leaders, and with the renewal of a social contract allowing former enemies to live together peacefully. The downside is that by channeling unresolved issues of the war, post-conflict electoral processes can become highly explosive and may even lead to the abandonment of

12

the entire peace process. This situation played out, for instance, in Cote d’Ivoire in 2010. That is why this dissertation is about exploring ways and means of transforming internationally sponsored post-conflict electoral processes into mechanisms of peace making.

Outline of the dissertation

The main objective of this dissertation is to explore the factors that determine whether internationally sponsored post-conflict elections will be effective or not, in terms of peace making.

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the current status of foreign electoral assistance in peace building. It explores the practices of donor-sponsored activities and programs targeted towards electoral assistance and more broadly, towards democracy promotion. From this assessment, I argue that electoral assistance providers, whether they are state or non-state actors, share the same outlook, as both categories of actor see electoral assistance as a long-term commitment, with goals that go far beyond the support of activities on polling day. These donor driven activities include long-term capacity building of stakeholders and institutions in order to support the emergence of democracy as a human-rights-based regime that permits compromise and peaceful resolution of conflicting interests. However, this empirical analysis of contemporary practices of electoral assistance demonstrates that there is a paradox between the stated intentions of both state and non-state providers of electoral assistance and their eventual actions. The effectiveness of electoral assistance in post-conflict settings is hampered by the routine willingness of donors to prioritize short-term assistance and quick-fix solutions over long-term assistance with the capacity to address deeper structural problems, which are often the largest barriers to peace. In this chapter, I also assess ways of delivering electoral assistance as well as the motivations of donors. I argue that electoral assistance that is provided through either bilateral or multilateral frameworks is a part of the foreign policy strategies of international contributors, which means it is part of a gain-seeking foreign policy strategy. Stated

13

otherwise, electoral assistance is not a neutral instrument, and it is essential to recognize that the strategies of both the providers and the recipients of electoral assistance will evolve across different circumstances. Thus, by evaluating practices of contemporary electoral assistance, Chapter 2 highlights the puzzle of electoral assistance provision and implementation in post-conflict setting as a means of peace consolidation.

Chapter 3 presents the theoretical argument. To account for success and failure of foreign electoral assistance in peace consolidation through post-conflict elections, I suggest a new theoretical explanation that I term actors-centered post-conflict electoral assistance theory. The theory states that for electoral assistance to be effective in consolidating peace in post-conflict settings, it has to facilitate dialogue between stakeholders and actions must be taken to foster their negotiation skills and ability to negotiate compromise over divided issues. It contends that the success of electoral assistance programs in post conflict settings is grounded in their ability to build the capacity of stakeholders to negotiate effectively with regard to peace consolidation. Therefore, strengthening electoral institutions with the aim of developing a legitimate electoral process for free and fair elections is not sufficient for preventing war and establishing durable peace in post conflict settings. In contrast to previous research on electoral assistance in post-conflict settings, which places an emphasis on the legal and institutional mechanisms that aim to deliver free and fair elections, this dissertation makes the fundamental claim that the effectiveness of electoral assistance in post-conflict societies relies upon the quality of relationships between stakeholders, which can be increased by facilitating dialogue between former warring parties as well as between major societal groups, and by emphasizing compromise.

After the conceptualization of the theory, the chapter exposes the theoretical predictions and the methodological framework for assessing the theory.

Chapter 4 explores post-conflict elections and their role in the context of peace agreements. It aims to analyze the impact of the negotiation and implementation of peace agreements on post-conflict electoral processes. I argue that since post-conflict elections are provisions in peace agreements, they are therefore an integral part of the peace process

14

and should be conceived of as such. This represents a specific feature of post-conflict elections that distinguishes them from other elections held in different circumstances. The implication of this argument is that peace agreements and post-conflict electoral processes are mutually related and influence each other. The better stakeholders have performed in terms of negotiating and implementing a peace agreement, the better they are able to perform in the post-conflict electoral process and the better their prospects of securing peace. Peace agreements provide stakeholders with the opportunity to learn to negotiate and to compromise over central issues in order to restore peace. This is very important for the rest of the peace process and for the electoral process. Therefore, the design of electoral laws and institutions as well as the electoral capacity building of stakeholders depends on how much stakeholders have been included in the peace process and how ready they are to participate in the electoral process. That is why electoral assistance providers cannot disregard the situation of the implementation of peace agreements and the entire peace process.

The next two chapters 5 and 6 explore the implementation of electoral assistance during post-conflict electoral processes across four case studies: Sierra Leone in 2002, Liberia in both 1997 and in 2005, and Côte d’Ivoire in 2010. The two chapters are framed as different parts of an electoral game.

Chapter 5 focuses on the players. It examines the effect of electoral assistance programming that provides training and awareness-raising activities for electoral stakeholders. These activities are usually labeled under the broad umbrella of electoral civic education, which refers to a broad democratic education that includes civic education, strengthening of civil society groups and awareness-raising programs about citizens’ rights and responsibilities in a democratic society. Electoral civic education has been a central component of foreign electoral and democratic assistance. I argue that these training and awareness raising activities can play a significant role in strengthening stakeholders’ capacity to engage peacefully in the electoral process. Indeed, awareness-raising activities can help to encourage non-combatants and former belligerents alike to favor the electoral

15

process as a solution to restore durable peace, rather than a return to war. I therefore assess in this chapter the quality and the possible impact of electoral civic education activities in each post-conflict electoral process.

Chapter 6 evaluates the impact of electoral assistance activities aimed at crafting, implementing and supporting electoral institutions and rules. While the previous chapter focuses on the training of the players, this chapter focuses on analyzing the framework and rules of the game. It assesses the quality and the impact of reforms that target electoral laws and electoral administrations, including electoral commissions that usually are in charge of the technical organization of elections. I argue that assistance to consolidate these institutional mechanisms is important but not sufficient to ensuring the effectiveness of internationally assisted post-conflict elections in restoring durable peace. The chapter strives to find similarities and differences in institutional capacity building both in successful and failed post-conflict electoral processes. This comparison provides clues to gauge the weight of electoral institutions in the post-conflict electoral process. Chapter 6 also probes the capacity of electoral management bodies in handling the electoral campaigns, polling day operations, and the election outcomes. It assesses how the training of the players and the strengthening of electoral institutional mechanisms and rules come into play during the post-conflict electoral process. It will try to explain why the elections in each particular case succeeded or failed in contributing to peace consolidation. As I theorize, I expect successful contributions to peace consolidation in cases where either the peace process or the electoral process (or both) helped stakeholders to improve their mutual trust and their capacity of negotiation and compromise building. The empirical analysis of the four post-conflict elections provides clues to evaluate the above theoretical argument.

Chapter 7 concludes the dissertation by summarizing the findings of the four case studies. It recalls that, in post-conflict settings, electoral processes are an important part of the broader peace processes and therefore require more than the usual ‘technical’ interventions aimed at delivering legitimate electoral processes. For, free and fair elections

16

are not sufficient to prevent a return to war in post-conflict societies. This concluding chapter will therefore emphasize the policy implications of how to implement electoral assistance in post-conflict settings in a way that prioritizes building the negotiating and peace building capacities of the key actors in post-conflict electoral processes.

In sum, in addition to its academic interest, this doctoral research offers direction for the formulation of future policy-making proposals, and for the definition and implementation of electoral assistance as a mechanism that can work to resolve the internal conflicts that are becoming increasingly visible in many parts of the world.

17

CHAPTER 2: CURRENT STATUS AND CHALLENGES OF

FOREIGN ELECTORAL ASSISTANCE IN PEACEBUILDING

2.0. Introduction

In order to explain the determinants of success and failure of post-conflict elections in peacebuilding, it is critical to understand first what electoral assistance is. Who are its providers? How is electoral assistance delivered? What are the main issues surrounding the provision and the implementation of electoral assistance in post-conflict settings?

This chapter answers to the above mentioned question by providing a broad picture of the actual state of foreign electoral assistance in peace building. It examines donors’ sponsored activities and programs provided under the specific label of electoral assistance or under the broad label of democracy promotion. Understanding what other types of assistance are associated with electoral assistance can help in assessing the contribution of internationally assisted post-conflict elections in peace building. Likewise, a better knowledge of challenges linked to the provision and the implementation of electoral assistance can shed light on this dissertation’s puzzle that is, why have internationally assisted post-conflict elections been effective as a tool for peace consolidation in some post-conflict societies while failing to achieve the same result in other post-conflict societies?

I argue in this chapter that the effectiveness of electoral assistance in post-conflict settings is undermined by the fact that providers of electoral assistance tend to prefer quick-fix solutions through short-term assistance instead of long-term assistance that could address structural problems. Furthermore, like any foreign aid, electoral assistance is not always neutral and may respond to gain-seeking foreign policy strategies of international providers of electoral assistance.

18

The first section of this chapter appraises the notions of electoral assistance and democracy promotion. I extensively analyze democracy promotion activities because most of electoral assistance programs are provided under the umbrella of democracy promotion. To some extent, strategies of democracy promotion shape the definition and the implementation of electoral assistance. The first section also captures the conceptual evolution of “election assistance” to “electoral assistance” and its implications for policy decision-making. The second section assesses practices in the provision of electoral assistance. It analyzes the context and especially peacekeeping operations through which post-conflict electoral assistance is usually delivered. It then analyzes bilateral and multilateral provision of electoral assistance and problems attached to the delivery of electoral assistance in general and in post-conflict situations in particular.

By portraying the current state of the use of foreign electoral assistance in post-conflict elections, this chapter will lay the groundwork for explaining successes and failures of internationally assisted elections as a tool for peace building.

2.1. Appraising the Notions and Practices of Contemporary Electoral Assistance Electoral assistance is a sub-set of democracy promotion. Often, providers of electoral assistance label their assistance in terms of democracy promotion. Therefore, a better understanding of the concept of electoral assistance cannot ignore an understanding of the broader concept of democracy promotion. Challenges facing democracy promotion directly affect electoral assistance. Therefore the broad context of democracy promotion can shed light on the mixed record of externally supported post-conflict electoral processes in consolidating peace.

19 2.1.1. Defining Democracy Promotion

Democracy promotion has gained much importance in foreign aid policies during the past two decades. According to David Gillies (2011, p. xxi), “each year, an estimated US$6 billion to $8 billion is spent on democracy assistance” by states and international organizations worldwide. Most of the donors are Western developed countries and their agencies such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the United Kingdom's Department for International Development (DFID), the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), the European Commission through EuropeAid, and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Besides these major actors, most Western countries include, almost systematically, democracy promotion in their foreign aid or make it a condition for receiving international aid.

Despite the fact that democracy promotion has gained prominence in international aid policies, its nature and its content do not produce consensus in the literature. Democracy promotion remains a rather vague concept which has many substitutes such as: democracy assistance, democracy-building assistance, democracy-related assistance, democracy aid, political aid, political assistance, political system reform assistance, political development aid, support for democracy, support for democratic development, etc. As noted by Peter Burnell (2000, p. 4), “the given terms are not all synonymous. Each one carries value-laden connotations, a certain amount of ideological and even historical baggage.” For instance, some authors may have a preference for the use of the concept of “support for democracy” rather than “democracy promotion.” The first is less pushy or less self-assertive than the second.

Peter Burnell suggests considering three criteria when defining democracy assistance: the provider’s intention, which should be the advance of democracy; the method of delivering democracy assistance, which should be peaceful; and the objective of

20

the arrangement, which should be on a not-for-profit basis (Burnell, 2000, p. 5). However, how can one be assured about the intentions of a democracy promoter? Behind the discourse of democracy promotion, how can one be confident that the promoter is not seeking to advance its own interests? Empirical studies have demonstrated that democracy assistance has not constantly been provided through peaceful methods nor has it been beyond reproach of self-interest (Brown, 2005).

The great diversity of contexts, purposes and uses of democracy promotion makes it very difficult to define the concept of democracy promotion concisely and accurately. However, minimally defined, democracy promotion is any activity undertaken purposely to establish or to foster democracy as a political system and as a state of law. From this standpoint, democracy assistance projects and programs aim at promoting democracy as a goal for itself, or as an instrument for achieving peace, economic and human development, respect for human rights, social equality, and any other activity that contributes to the rooting of democratic principles and culture within a society. The table below displays major components of democracy assistance:

21 Table 1: Democracy Promotion Components

Components Purposes Activities

Electoral assistance Ensure the integrity of an electoral process

Hold credible, free and fair elections

Technical and financial assistance Election assessment

Election supervision

Governance assistance Ensure accountable, participative and transparent ways of managing public affairs Support the establishment

of a democratic constitution and State institutions

Reform of public administration Improvement of government

effectiveness Control of corruption Constitutional assistance

Improvement of regulatory quality and law-oriented institutions

Capacity building for state institutions Building of a well-functioning state

Media assistance Support the emergence of free and independent media

Funding

Professional development Media education

Improvement of legal environment

Human rights assistance Support the respect of ‘first generation’ rights: political rights and civil liberties

Empowering law enforcement institutions

Empowering human rights associations Legal reforms

Human rights education

Human development

assistance Support the emergence and respect of ‘second generation’ rights: socio economic rights

Promotion of developmental projects Promotion of equitable socioeconomic

development

Capacity building for citizens, civil society groups, and worker organizations

Union building

Democracy promotion is as diverse in its content as in its approaches. Indeed, the approaches can be political or developmental (Carothers, 2009), selective or non-selective, interventionist or non-interventionist, or a mixture of several approaches. Each of these approaches to democracy promotion has different objectives and strategies as displayed below in table 2.