HAL Id: dumas-01517888

https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01517888

Submitted on 3 May 2017HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Utilisation du chef médial du muscle triceps brachii pour

la couverture des pertes de substance complexes des

membres

Anaïs Delgove

To cite this version:

Anaïs Delgove. Utilisation du chef médial du muscle triceps brachii pour la couverture des pertes de substance complexes des membres. Médecine humaine et pathologie. 2017. �dumas-01517888�

Université de Bordeaux

UFR des Sciences Médicales

Année 2017 – Thèse n°3009

UTILISATION DU CHEF MÉDIAL

DU MUSCLE TRICEPS BRACHII

Pour la couverture

Des pertes de substance complexes des membres

Thèse présentée le 23 mars 2017 Pour l’obtention du

Diplôme d’État de Docteur en Médecinepar

Mademoiselle Anaïs Delgove née le 19 mars 1988 à La Tronche (38)

Thèse dirigée par

Monsieur le Docteur Romain Weigert

Composition du jury

Monsieur le Professeur Vincent Casoli, président Monsieur le Professeur Thierry Fabre, rapporteur Monsieur le Professeur Philippe Pelissier, juge Monsieur le Professeur Vincent Pinsolle, juge

Couverture : Représentation du Discobole de Myron — Dessin Anne Delgove

Remerciements

Monsieur le Professeur Vincent Casoli, président du jury.

Vous me faites l’honneur de présider cette thèse dont le sujet est avant tout le votre. Depuis le début de mon internat, je bénéficie de votre soutien, de vos conseils et de vos enseignements : l’anatomie, la microchirurgie et la reconstruction des membres, mais aussi le compagnonnage, la ténacité, la réactivité, et les bonnes manières. J’espère pouvoir et savoir transmettre tout cela à mon tour. Veuillez trouver ici toute ma gratitude et ma recon-naissance.

Monsieur le Docteur Romain Weigert, directeur.

Je te remercie pour ta réactivité, tes conseils avisés et tes remarques constructives tout au long de ce travail. Nous nous intéressons à des domaines différents de la chirurgie plastique mais tu m’as toujours guidée et conseillée sur le chemin à suivre. Tu m’as encouragée à lire, à me former, à participer aux congrès. J’espère continuer à profiter de ton expérience.

Monsieur le Professeur Thierry Fabre, rapporteur.

Vous apportez la caution orthopédique à ce travail et je vous en remercie. Vous m’avez accueillie à deux reprises dans votre service afin que j’y acquière les concepts et les connaissances complémentaires nécessaires à la chirurgie du membre supérieur et à la reconstruction des membres. J’espère pouvoir continuer à travailler avec votre belle équipe.

Monsieur le Professeur Philippe Pelissier, juge.

Vos enseignements ont marqué des générations d’étudiants et d’internes à Bordeaux et ailleurs. La précision et la rapidité de votre geste chirurgical m’ont marquée, j’espère avoir davantage l’occasion d’apprendre à vos côtés. Merci d’avoir accepté de juger cette thèse.

Monsieur le Professeur Vincent Pinsolle, juge.

Merci pour la gentillesse et la bienveillance avec laquelle vous partagez vos connaissances et votre expérience au quotidien dans le service. Soyez assuré de mon respect et de ma gratitude.

Remerciements

Monsieur le Docteur Henri Duraffour,

Ce premier semestre de chirurgie à vos côtés me restera en mémoire. J’y ai appris les bases de la chirurgie générale et de la chirurgie orthopédique. J’essaie de suivre scrupuleusement vos conseils avisés et les transmets à mon tour aux plus jeunes : ”ne jamais abandonner un patient”, ”opérer beaucoup pour opérer bien” et ”aller voir ailleurs, surtout en consultation !”. Veuillez trouver ici toute ma reconnaissance et mon respect.

Monsieur le Docteur Maxime Laporte, Madame le Docteur Marie-Laure Abi-Chahla,

Tu es indiscutablement la personne qui m’a le plus guidée en chirurgie de la main. Tes connaissances, ton expé-rience chirurgicale, ton compagnonnage, ta pédagogie et ta motivation sont pour moi un exemple. J’ai hâte de travailler à nouveau avec toi. Merci de ton amitié.

Madame le Docteur Camille Poujardieu,

Messieurs les Docteurs Hussein Choughri & Jean-Christophe Lepivert,

Messieurs les Docteurs Julien Pallaro, Bertrand Dunet, Clément Tournier,Vincent Souillac, Thi-bault Masquefa, Rafael De Bartolo & Nicolas Verdier,

Merci pour ces deux semestres passés dans votre équipe et pour tous vos enseignements au sujet de cette belle spécialité. Je retiendrai quelques phrases clefs : ”Demain, il fera jour.” & ”Nous ne sortirons pas de ce bloc tant que ce ne sera pas parfait.” Merci pour tout.

Madame le Docteur Alexandra Erbland,

Tes enseignements en chirurgie du membre supérieur ont été précieux. Tes connaissances et ta rigueur sont exem-plaires. J’espère pouvoir continuer à apprendre à tes côtés.

Monsieur le Docteur Gaël Ledoyer,

Vos qualités chirurgicales et de chef de service ont été pour moi un exemple. Nous avons souvent discuté des techniques utilisées en chirurgie vasculaire et de leurs applications possibles en chirurgie plastique. Ces échanges ont toujours été intéressants et instructifs pour moi. Merci d’avoir eu la patience de me transmettre un peu de votre savoir faire. Soyez assuré de mon profond respect.

Monsieur le Docteur Nicolas Ottaviani,

Messieurs les Docteurs Rémi Klotz & Jean-Louis Bovet,

Vous avez accepté de m’accueillir chacun dans vos spécialités et de m’apporter une formation complémentaire

Remerciements

indispensable. Votre engouement pour les nouvelles techniques et le partage des expériences est remarquable. Veuillez trouver ici tout mon respect et ma reconnaissance.

Monsieur le Professeur Gilles Dautel,

Vos connaissances, votre expérience et vos qualités chirurgicales et de chef de service sont incommensurables. J’espère être un jour à la hauteur de vos enseignements. Veuillez trouver ici mon infinie reconnaissance.

Monsieur le Docteur Stéphane Barbary,

Tu excelles dans ton domaine. Merci de ta gentillesse et de faire partager ce don chirurgical que tu développes avec tant d’audace. J’espère que le futur apportera d’autres occasions d’apprendre à tes côtés.

Monsieur le Docteur Jeremie Chevrollier & Madame le Docteur Sandrine Huguet,

Monsieur le Professeur Éric Dobremez, Messieurs les Docteurs Yan Lefèvre, Abdelfetah Lalioui, Luke Harper & Mesdames les Docteurs Audrey Angelliaume, Maya Loot & Carmen Trabanino,

Merci de m’avoir accueillie dans votre équipe dynamique, vos enseignements en chirurgie pédiatrique et votre gentillesse ont fait de ce semestre une superbe et indispensable expérience.

Aux équipes soignantes,

avec qui j’ai eu le plaisir de travailler à Pau, à Bordeaux et à Nancy.

Au personnel du Laboratoire d’Anatomie de la Faculté de Bordeaux,

Remerciements

À Juliette Coudurier,

Tu m’as soutenue et rassurée dans les grands moments depuis ma première année de médecine. Je me souviens de ce coup de téléphone où tu me conseilles de choisir la chirurgie de la main en premier stage d’externat. Merci !

À Marie-Aude & Gérald Houbart,

Ces années grenobloises à vos côtés sont d’excellents souvenirs. Malgré l’éloignement, j’espère vous voir souvent.

À mes amis Grenoblois Angélique Franchi, Nicolas Ravier, Yoann Doudeau, Dominique Seblain, Da-vid Jospin, Marion Aribert, Clément Boguet, Juliette Beguin-Lecuyer, Clément Trincat, Tiphaine Ge-nevois, David Tournoux & Quentin Morelot

Merci pour ces années d’insouciance et ces vacances à travers l’Europe fortes en culture et en activités sportives...

À Jeremie & Barbara Papin,

Notre première rencontre bordelaise et non la moindre. Merci de votre présence et de votre amitié.

À Alison Denis-Delesque & Simon Mazas,

Alison, mon étoile polaire ! Toujours disponible et toujours d’excellent conseil ! Je te remercie tout simplement, pour tout ce que nous avons partagé jusqu’ici. J’ai hâte de continuer la route avec vous deux.

À Adrien Cadennes,

Mon bon Cadennes, tu as animé nos semestres, nos soirées et même nos vacances, avec ton humour et ta gen-tillesse. Je suis tellement contente que tu reviennes !

À Olivier Camuzard,

le plasticien ORL qui fait de la main. Quelle belle rencontre personnelle et professionnelle ! Merci pour ces 6 mois à Nancy, je te souhaite le meilleur et espère te revoir souvent.

À Johanna Zemmour, Éva Gachie, Audrey-Élodie Mercier, Charlie Verbruggen, Gabriel Vallade, Débo-rah Royaux, Maylis Berger, Tiphaine Menez, Thomas Sagardoy, Mathias Blangis, Clément Ribes, Tho-mas Thelen, Corentin Velut, Pierre Coudert, Marion Dias, Romain Detammaecker, Hugo Maschino, Juliette Lombard, Héléne Agneray, Stéphane Jullion, Valentin Calafat, Edouard Harly, Thomas De-lefortrie, Pauline Savidan, Pierre Paillet, Camille Poutays, Xavier Thevenot, Antoine Dannepond & Antoine Héron,

La différence entre un bon et un excellent stage d’internat, ce sont les co-internes. Merci pour tout.

À Renaud, Boris & Camille, Raphael & Marina, Julien & Aida, Matthieu, Kolyan & Erika, Sylvain À Messieurs les génies Matthew Bellamy, Freddie Mercury & Frédéric Chopin

Remerciements

À Josselin,

Ma moitié, mon équipier, mon plus solide atout.

Quel bonheur et quelle chance de partager ton quotidien, d’avancer avec toi. Ton aide et ton soutien pour cette thèse comme pour l’ensemble de mon parcours professionnel sont inestimables. Merci pour tout. Je t’aime.

À mes parents,

Je vous dois tant. Votre éducation, vos valeurs, votre soutien, votre réconfort et vos encouragements m’ont permis de traverser ces années d’étude avec envie et enthousiasme et d’obtenir les clefs d’un métier passionnant. Veuillez trouver ici tous les deux mon infinie reconnaissance. Je vous aime.

À mes soeurs,

Héloïse, Zoë, je vous remercie pour votre soutien sans faille. Être votre grande soeur est un honneur. Avancer dans la vie à vos côtés est un plaisir. Je suis extrêmement fière de vous. Je vous aime.

Aux moitiés,

Gautier, Florian, merci d’être là, aux côtés de mes soeurs. Vous êtes géniaux, ne changez rien. Je vous aime. Sylvie, merci pour ton interêt et ton soutien, au côté de papa.

À mes grands parents, mes oncles et tantes, mes cousins et cousines. À ma belle famille,

Votre accueil, votre intérêt et votre soutien sont un pilier de plus dans la construction de ma vie. Veuillez trouver ici ma profonde gratitude.

Table des matières

Remerciements i

Liste des figures xi

Liste des tableaux xiii

Liste des abréviations xv

i Introduction 1

i.1 Problématique des pertes de substance complexes des membres (PSCM) . . . 1

i.2 Prise en charge des PSCM . . . 2

i.3 Progrès de la reconstruction . . . 3

i.4 Cahier des charges de la prise en charge des PSCM . . . 3

i.5 Travaux sur la thématique au CHU de Bordeaux . . . 3

i.5.1 Description anatomique du chef médial du triceps brachial . . . 4

i.5.2 Technique chirurgicale de prélèvement du chef médial du triceps brachial comme lambeau libre . . . 4

i.5.3 Technique chirurgicale de prélèvement du chef médial du triceps brachial comme lambeau pédiculé . . . 5

i.6 Objectifs du travail de thèse . . . 7

Références . . . 8

1 Medial triceps brachii free flap in lower limb reconstructive surgery 11 1.1 Introduction . . . 12

1.2 Material and methods . . . 12

1.2.1 Charts and clinical examination . . . 12

1.2.2 Statistical analysis . . . 12

1.3 Results . . . 13

1.3.1 Population . . . 13

1.3.2 Surgical procedure . . . 13

Table des matières

1.4 Discussion . . . 18

1.5 Conclusion . . . 20

References . . . 21

2 Evaluation of donor site morbidity after medial triceps brachii free flap for lower limb recon-struction 25 2.1 Introduction . . . 26

2.2 Methods . . . 26

2.2.1 Study design . . . 26

2.2.2 Health record analysis . . . 26

2.2.3 Surgical technique . . . 27 2.2.4 Patient questionnaires . . . 27 2.2.5 Clinical examination . . . 28 2.2.6 Statistical analysis . . . 28 2.3 Results . . . 29 2.3.1 Population . . . 29 2.3.2 Functional results . . . 29 2.3.3 Cosmetic results . . . 30 2.3.4 Global satisfaction . . . 30 2.4 Discussion . . . 30 2.5 Conclusion . . . 34 References . . . 35

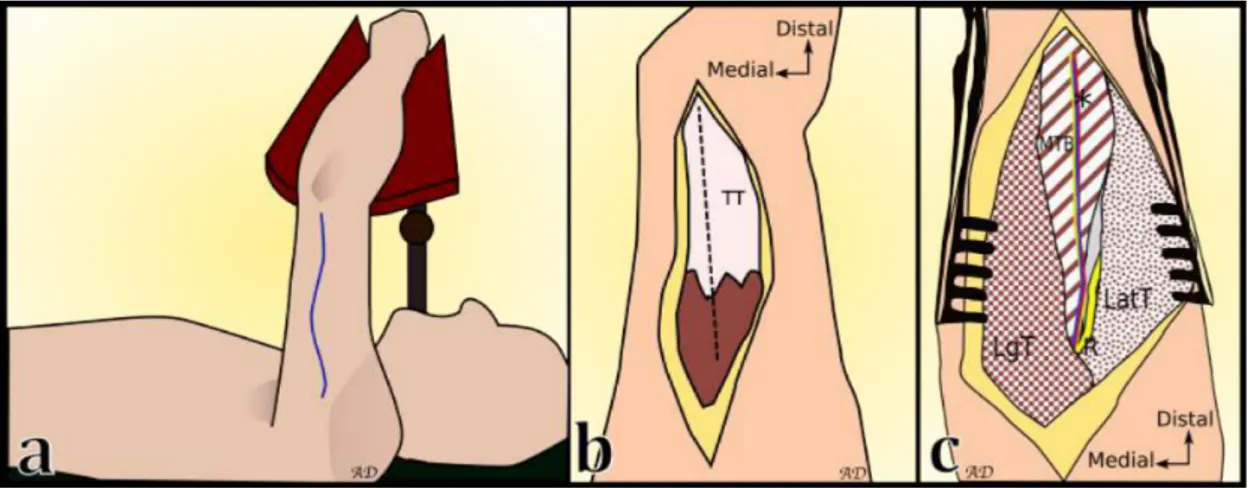

3 A new local muscle flap for elbow coverage: the medial triceps brachii flap. Anatomy, surgical technique and preliminary outcomes 37 3.1 Introduction . . . 38

3.2 Materials and methods . . . 38

3.2.1 Study design . . . 38

3.2.2 Statistical analysis . . . 38

3.3 Results . . . 39

3.3.1 Population . . . 39

3.3.2 Surgical technique . . . 39

3.3.3 Flap procedure and wound healing . . . 40

3.4 Discussion . . . 41 3.5 Conclusion . . . 44 References . . . 45 Conclusion 47 Références . . . 49 viii

Table des matières

a Annexes 51

QuickDASH . . . 51 POSAS . . . 54

Liste des Figures

i.1 Dessin anatomique réalisé au pastel . . . 6

1.1 Number of medial triceps brachii (MTB) free flap in each group on the observation period . . . 14

1.2 Learning curve of the MTB free flap procedure. . . 15

1.3 Patient photographs . . . 16

2.1 Surgical approach . . . 27

2.2 Correlation between OSAS and PSAS scales . . . 32

2.3 Scars on the posterior aspect of the arm . . . 33

2.4 Surgical approach and anatomical landmarks . . . 34

3.1 Patient photographs, surgical set up and approach . . . 40

3.2 Patient photographs . . . 42

3.3 Anatomical dissection on a right arm from a latex-injected fresh cadaver . . . 43

a.1 QuickDASH. Part 1. . . 52

a.2 QuickDASH. Part 2. . . 53

a.3 POSAS Observer Scale . . . 54

Liste des tableaux

1.1 Mechanism and wound characteristics in the three groups of patient . . . 14

1.2 Characteristics for flap failure . . . 17

1.3 Care delays, time to wound healing, bone union, walk recovery and complications in each group . . . 17

1.4 Time to bone union and walk recovery regarding reconstruction bone type . . . 17

1.5 Number of surgical procedure and duration of hospital stay for each group . . . 18

2.1 Medical Research Council scale . . . 28

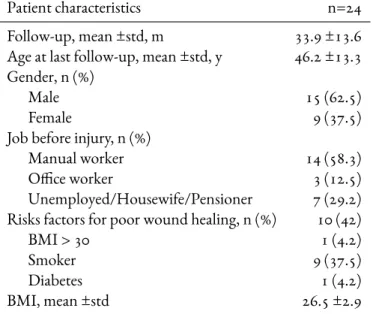

2.2 Patient characteristics . . . 29

2.3 Functional results . . . 30

2.4 Cosmetic results . . . 31

3.1 Patient characteristics . . . 39

Liste des abréviations

ATA Artère Tibiale Antérieure Anterior Tibial Artery

BMI index de masse corporelle Body Mass Index

DBA artère brachiale profonde Deep Brachial Artery

ITFG greffe inter-tibio-péronière Inter Tibio Fibular Graft

MCA artère collatérale moyenne Middle Collateral Artery

MRC Medical Research Council

MTB chef Médial du muscle Triceps Brachial Medial head of the Triceps Brachii muscle

n Number of patients

NPWT thérapie à pression négative Negative Pressure Wound Therapy

ORIF réduction à foyer ouvert - fixation interne Open Reduction - Internal Fixation

POSAS Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale

PSCM Perte de Substance Complexe des Membres complex lower limb injury

PTA artère tibiale postérieure Posterior Tibial Artery

QuickDASH Quick Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand

i

Introduction

i.1

Problématique des pertes de substance complexes des membres (PSCM)

L

a reconstruction des pertes de substance complexes des membres est un domaine majeurde la chirurgie plastique et reconstructrice. Les pertes de substance des membres peuvent être d’origine traumatique (fractures ouvertes, écrasements, dégantages), infectieuse (ostéo-myélites, ostéo-arthrites), tumorale ou iatrogène (désunions cicatricielles ou nécroses cutanées post-opératoires). Elles peuvent être pluritissulaires (os et/ou muscle et/ou peau et/ou structures vasculo-nerveuses), et associées à une ostéite chronique et/ou une pseudarthrose. La guérison demande la stéri-lisation des tissus, la consolidation osseuse et la cicatrisation cutanée, ces trois éléments étant largement dépendants les uns des autres. Lorsqu’un ou plusieurs critères ne sont pas acquis et que les solutions de reconstruction sont épuisées, un geste radical non conservateur est proposé : l’amputation. Les solutions disponibles pour obtenir la cicatrisation cutanée forment un éventail de techniques plus ou moins complexes : cicatrisation dirigée, thérapies à pression négative, greffes de peau, substituts der-miques, lambeaux locaux, régionaux et libres. La cicatrisation dirigée, les thérapies à pression négative, les greffes de peau ou les substituts dermiques ne font pas parties des solutions de première intention en présence d’exposition osseuse ou articulaire ou en présence d’une pseudarthrose. En effet, ces situations nécessitent une couverture par des tissus vascularisés et de bonne trophicité. Dans ces cas d’expositions osseuses ou articulaires, la couverture se fait la plupart du temps par des techniques de lambeaux. Ils sont locorégionaux lorsqu’ils sont prélevés près du site à couvrir ou libres lorsqu’ils sont prélevés à distance et qu’ils nécessitent des anastomoses vasculaires.i. Introduction

i.2 Prise en charge des PSCM

Des parcours de soins identifiés et des équipes pluridisciplinaires et pluriprofessionnelles voient le jour dans les centres hospitaliers universitaires depuis plusieurs années pour prendre en charge les patients nécessitant une reconstruction des PSCM. Ces équipes regroupent des chirurgiens orthopédistes, des chirurgiens plasticiens, des médecins infectiologues, des infirmières spécialisées en cicatrisation, des mé-decins rééducateurs et des psychologues. Leur domaine d’action s’étend des pertes de substances pluri-tissulaires traumatiques des membres, en passant par les ostéomyélites chroniques fistulisées à la peau, les tumeurs avec résection massive, jusqu’au remodelage des moignons d’amputation ou à la couverture de matériel d’ostéosynthèse exposé [1].

Ces nouvelles filières font l’objet de nombreuses études et semblent diminuer le temps d’hospitalisation, augmenter la rapidité de la prise en charge des patients et diminuer le risque d’ostéite [2–4]. Les der-nières décennies ont vu également le développement de raffinement dans les techniques en chirurgie orthopédique (« damage control » orthopédique [5], nouveaux fixateurs externes) et en chirurgie plas-tique (lambeaux composites) [6], ainsi que des progrès technologiques (substituts dermiques) [7,8]. Malgré ces progrès, les résultats à long terme des reconstructions n’apparaissent pas meilleurs qu’après amputation et appareillage [9–14]. Les procédures de reconstruction, lorsqu’elles sont mises en oeuvre, font l’objet de complications plus fréquentes, de durées d’hospitalisation plus longues et d’un plus haut taux de ré-intervention.

Le progrès des techniques et des matériaux d’appareillage ainsi que le caractère long et incertain des résultats d’une reconstruction sont les éléments expliquant l’absence de supériorité à long terme de la reconstruction sur l’amputation. Lorsque cette possibilité thérapeutique est expliquée et proposée au patient, elle est en général refusée au premier entretien, vécue comme un échec de la prise en charge, une mutilation définitive et la promesse de grandes séquelles physiques et psychologiques. Un des rôles des équipes pluridisciplinaires et pluriprofessionnelles est d’orienter le patient vers la meilleure solution thérapeutique en terme d’équilibre bénéfices/risques. De nombreux facteurs intrinsèques associés à des mauvais résultats de reconstruction ne peuvent être changés, mais la stratégie globale de prise en charge des PSCM peut être améliorée : réduire les délais de prise en charge, diminuer les taux d’échecs microchirurgicaux, obtenir une adhésion du patient et de sa famille au programme de reconstruction. Au CHU de Bordeaux, cette équipe pluridisciplinaire a été créée en 2009 et porte le nom ”Orthoplast”. Une visite hebdomadaire au lit du patient nécessitant un avis de chirurgie plastique a d’abord été instau-rée dans tous les services du CHU et plus particulièrement en orthopédie et en infectiologie. Depuis 2014, une réunion de concertation pluridisciplinaire hebdomadaire a complété la filière de prise en charge des PSCM.

i.3. Progrès de la reconstruction

i.3

Progrès de la reconstruction

Les avantages de la reconstruction sont la conservation de l’intégrité anatomique, plus ou moins esthé-tique, et la récupération partielle ou complète des fonctions du membre. Ces avantages sont à opposer aux inconvénients qui sont une plus longue durée de prise en charge médicale, avec de multiples hos-pitalisations et chirurgies, sans garantie de résultats. Il est nécessaire de continuer à progresser dans le développement de ces techniques de reconstruction afin de réduire les indications d’amputation. Le cahier des charges d’une chirurgie de reconstruction réussie est complexe. Les délais de prise en charge doivent être rapides, l’ostéosynthèse et la couverture tissulaire adaptées.

i.4

Cahier des charges de la prise en charge des PSCM

La couverture des PSCM permet une cicatrisation rapide, une consolidation osseuse et la prévention ou le traitement des ostéites. Elle se fait la plupart du temps par des techniques de lambeaux. Au ni-veau des membres inférieurs, les particularités des PSCM sont la position immédiatement sous la peau des structures osseuses et articulaires, voire du matériel d’ostéosynthèse et le nombre restreint de sites donneurs de lambeau local, notamment en région distale de jambe ou au niveau du pied. Ceci a plu-sieurs conséquences : la fréquence accrue d’exposition osseuse lors de traumatismes ou de désunions cicatricielles et le recours plus fréquent à des techniques de lambeaux libres, plus difficiles technique-ment et moins fiables [15]. Les lambeaux libres décrits sont nombreux mais aucun n’est idéal : lambeau libre antéro-latéral de cuisse, lambeau de muscle grand dorsal, lambeau brachial externe, lambeau de muscle serratus antérieur, lambeau de muscle gracilis. Le lambeau est choisi en fonction de la taille de la perte de substance, de sa localisation et des structures qu’il doit reconstruire. La morbidité du site donneur, fonctionnelle et esthétique, doit également être prise en compte. Une autre difficulté de la prise en charge des pertes de substance de la partie distale du membre inférieur est la nécessité d’une couverture de taille, d’épaisseur et de stabilité adaptées au chaussage et à la marche.

i.5 Travaux sur la thématique au CHU de Bordeaux

Dans une démarche d’amélioration des pratiques et de recherche appliquée, nous avons développé au CHU de Bordeaux un nouveau lambeau musculaire pur adapté au cahier des charges de la couverture des pertes de substance complexes distales des membres inférieurs : le lambeau de chef médial du triceps brachial (MTB). Deux études cadavériques et une étude préliminaire clinique ont montré la faisabilité et les premiers résultats de cette nouvelle technique [16–18].

i. Introduction

i.5.1 Description anatomique du chef médial du triceps brachial

Le triceps brachial est le seul muscle de la loge postérieure du bras. Il est extenseur de l’avant-bras sur le bras. Il est constitué de trois chefs musculaires. Le chef long est inséré sur le tubercule infra-glénoïdien de la scapula. Le chef latéral prend son insertion sur la partie proximale et postérieure de l’humérus au-dessus du sillon du nerf radial. Le chef médial nait de la partie postérieure de l’humérus en dessous du sillon du nerf radial et du septum intermusculaire médial. Les trois chefs musculaires convergent pour se terminer en un tendon unique : le tendon tricipital, s’insérant sur la partie proximale de l’olécrane [19, 20]. L’innervation du triceps provient du nerf radial [21,22]. Il donne une branche pour chaque chef musculaire. Il existe de rares cas décrits d’innervation partielle par le nerf ulnaire [23]. La vascularisation de ce muscle provient des branches de l’artère brachiale profonde (deep brachial artery, DBA) qui suit le nerf radial dans son sillon le long de l’humérus et se divise en artère collatérale moyenne (middle collateral artery, MCA) et artère collatérale radiale (radial collateral artery, RCA) [24]. Le chef médial du triceps est vascularisé par l’artère collatérale moyenne qui court à la surface du corps musculaire de manière longitudinale (Fig.i.1). Elle rejoint ensuite le cercle anastomotique du coude, en apportant sa vascularisation au muscle anconé [25,26]. Ces anastomoses avec les artères récurrentes radiales, ulnaires et interosseuses, permettent une utilisation du chef médial en lambeau pédiculé sur sa partie distale.

i.5.2 Technique chirurgicale de prélèvement du chef médial du triceps brachial comme lam-beau libre

Le prélèvement s’effectue sous anesthésie générale, en décubitus dorsal, avant-bras reposant sur un ap-pui situé à l’aplomb du thorax. La face postérieure du bras est ainsi exposée. Un champ d’extrémité délimite le site opératoire. Il est possible de positionner un garrot stérile de moyenne largeur à la racine du bras afin de faciliter la dissection. Celui-ci devra toutefois être retiré pour la fin de la dissection. Les repères cutanés sont tracés depuis le relief de l’insertion du deltoïde sur l’humérus jusqu’à la fossette olécranienne. L’incision cutanée expose le plan du tendon tricipital. La voie sera ensuite trans-tricipitale sur le bord latéral du tendon. Les fibres du chef médial du triceps sont décollées de la face profonde du tendon. L’espace entre le MTB et le septum intermusculaire latéral est disséqué. Plusieurs branches vas-culaires perforantes font, à cet endroit, l’objet d’une hémostase soigneuse. Le pédicule vasculonerveux du MTB est facilement repérable à la surface du corps musculaire, courant de manière longitudinale et centrale jusqu’à la gouttière du nerf radial en proximal et latéral.

La dissection musculaire trouve sa limite distale avant la fossette olécranienne afin de ne pas léser la cap-sule articulaire du coude et sa limite médiale au niveau du bord médial de l’humérus. Les perforantes à visée osseuse sont coagulées de manière soigneuse lorsque le muscle est détaché de la face postérieure de l’humérus. La dissection proximale intéresse uniquement le pédicule ou le pédicule et les fibres mus-culaires l’accompagnant. La jonction du pédicule avec la RCA est ligaturée et la DBA est disséquée au contact du nerf radial jusqu’à obtenir une longueur suffisante. Le lambeau est alors sevré et rincé au sérum hépariné.

i.5. Travaux sur la thématique au CHU de Bordeaux

Les corps musculaires restants sont rapprochés à l’aide de points en croix de fils tressés et le tendon est suturé par un surjet passé. La fermeture cutanée se fait sur drainage aspiratif profond avec un surjet in-tradermique. Un pansement semi compressif est laissé en place et le bras est surélevé pendant 48 heures. La surveillance postopératoire nécessite un examen sensitivo-moteur du nerf radial et du nerf ulnaire, ainsi que la vérification de l’absence de formation d’hématome. Le drainage est retiré au 3ème jour et le membre supérieur est rapidement mobilisé.

i.5.3 Technique chirurgicale de prélèvement du chef médial du triceps brachial comme lam-beau pédiculé

La localisation de ce muscle et sa vascularisation à rétro par le cercle anastomotique du coude ont éga-lement permis son utilisation en lambeau pédiculé pour la couverture des pertes de substances de la région du coude. L’installation et la voie d’abord sont similaires. Le chef médial exposé, c’est sa partie proximale qui est exposée en premier afin de ligaturer son pédicule. Il est ensuite séparé de ses attaches osseuses et septales de proximal en distal puis retourné sur la perte de substance à couvrir, en restant attaché par ses insertions distales sur l’humérus. La voie d’abord est refermée sur drainage aspiratif jus-qu’à la zone de retournement du lambeau. Celui-ci est greffé en peau fine immédiatement ou dans un second temps.

i. Introduction

Figure i.1 –Dessin anatomique au pastel. Anne Delgove. 1, chef médial du triceps brachii ; 2, chef latéral du triceps brachii ; 3, chef long du triceps brachii ; 4, nerf ulnaire ; 5, nerf radial ; 6, pédicule vasculo-nerveux du chef médial (artère collatérale moyenne et nerf de l’anconé) ; 7, artère brachiale profonde ; 8, artère collatérale radiale.

i.6. Objectifs du travail de thèse

i.6

Objectifs du travail de thèse

Les objectifs de ce travail étaient :1. d’évaluer les résultats des reconstructions de pertes de substances complexes du membre inférieur réalisées avec le lambeau libre de chef médial du triceps brachial ;

2. d’évaluer la morbidité du site donneur de ce lambeau ;

3. d’évaluer les résultats des couvertures des pertes de substance du coude avec le chef médial du triceps brachial utilisé en lambeau pédiculé.

i. Introduction

Références

1. Lerman, O. Z., Kovach, S. J. & Levin, L. S. The respective roles of plastic and orthopedic surgery in limb salvage. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 127 Suppl, 215S–227S. issn : 1529-4242 (jan. 2011).

2. Mathews, J. A., Ward, J., Chapman, T. W., Khan, U. M. & Kelly, M. B. Single-stage or-thoplastic reconstruction of Gustilo–Anderson Grade III open tibial fractures greatly reduces infection rates. Injury 46, 2263–2266. issn : 00201383 (nov. 2015).

3. Fernandez, M. A. et al. The impact of a dedicated orthoplastic operating list on time to soft tissue coverage of open lower limb fractures. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 97, 456–9. issn : 1478-7083 (sept. 2015).

4. Chummun, S., Wright, T. C., Chapman, T. W. L. & Khan, U. Outcome of the management of open ankle fractures in an ortho-plastic specialist centre. Injury 46, 1112–1115. issn : 18790267 (2015).

5. Pape, H.-C. C., Giannoudis, P. & Krettek, C. The timing of fracture treatment in poly-trauma patients : Relevance of damage control orthopedic surgery. American Journal of Surgery 183, 622–629. issn : 00029610 (juin 2002).

6. Perrot, P., Kitsiou, C., Yeo, S., Lescour, V. & Duteille, F. Le lambeau libre composite costomusculaire de serratus anterior dans le traitement des pertes de substance complexes du membre inférieur : à propos de 20 cas avec 5 ans de recul. Annales de Chirurgie Plastique

Esthé-tique 61, 263–269. issn : 02941260 (août 2016).

7. Lamy, J., Gourari, A., Atlan, M. & Zakine, G. Utilisation de Matriderm® 1mm en chirurgie reconstructrice. Série de 31 cas. Annales de Chirurgie Plastique et Esthetique 58, 235–242. issn : 02941260 (juin 2013).

8. Alet, J. M., Weigert, R., Castede, J. C. & Casoli, V. Management of traumatic soft tissue defects with dermal regeneration template : A prospective study. Injury 45, 1042–1048. issn : 18790267 (2014).

9. Penn-Barwell, J. G. et al. Medium-term outcomes following limb salvage for severe open tibia fracture are similar to trans-tibial amputation. Injury 46, 288–291. issn : 18790267 (fév. 2015). 10. Bosse, M. J. et al. An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation after leg-threatening

injuries. The New England journal of medicine 347, 1924–31. issn : 1533-4406 (déc. 2002). 11. Fochtmann, A., Mittlböck, M., Binder, H., Köttstorfer, J. & Hajdu, S. Potential

prognostic factors predicting secondary amputation in third-degree open lower limb fractures.

The journal of trauma and acute care surgery 76, 1076–81. issn : 2163-0763 (avr. 2014).

Références

12. Hoogendoorn, J. M. & van der Werken, C. Grade III open tibial fractures : functional out-come and quality of life in amputees versus patients with successful reconstruction. Injury 32, 329–34. issn : 0020-1383 (mai 2001).

13. MacKenzie, E. J. et al. Long-Term Persistence of Disability Following Severe Lower-Limb Trauma. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 87, 1801–1809. issn : 00219355 (août 2005). 14. Ladlow, P. et al. Influence of Immediate and Delayed Lower-Limb Amputation Compared

with Lower-Limb Salvage on Functional and Mental Health Outcomes Post-Rehabilitation in the U.K. Military. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 98, 1996–2005. issn : 0021-9355 (déc. 2016).

15. Pinsolle, V., Reau, A. F., Pelissier, P., Martin, D. & Baudet, J. Soft-tissue reconstruction of the distal lower leg and foot : are free flaps the only choice ? Review of 215 cases. Journal of

Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery 59, 912–917. issn : 17486815 (2006).

16. Piquilloud, G., Villani, F. & Casoli, V. The medial head of the triceps brachii. Anatomy and blood supply of a new muscular free flap : the medial triceps free flap. Surgical and radiologic

anatomy : SRA 33, 415–20. issn : 1279-8517 (juil. 2011).

17. Villani, F., Piquilloud, G. & Casoli, V. The medial head of triceps brachii : A muscular flap.

Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery 65, e263–e264. issn : 17486815 (2012).

18. Delgove, A. et al. Medial triceps brachii free flap in reconstructive surgery : a prospective study in eight patients. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery 135, 275–82. issn : 1434-3916 (fév. 2015).

19. Lim, A. Y., Pereira, B. P. & Kumar, V. P. The long head of the triceps brachii as a free func-tioning muscle transfer. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 107, 1746–52. issn : 0032-1052 (juin 2001).

20. Madsen, M. et al. Surgical anatomy of the triceps brachii tendon : anatomical study and clinical correlation. The American journal of sports medicine 34, 1839–43. issn : 0363-5465 (nov. 2006). 21. Cho, H., Lee, H. Y., Gil, Y. C., Choi, Y. R. & Yang, H. J. Topographical anatomy of the radial nerve and its muscular branches related to surface landmarks. Clinical Anatomy 26, 862–869. issn : 08973806 (2013).

22. Tubbs, R. S. et al. Anatomy and landmarks for branches of the brachial plexus : A vade mecum.

Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 32, 261–270. issn : 09301038 (2010).

23. Loukas, M. et al. Ulnar nerve innervation of the medial head of the triceps brachii muscle : A cadaveric study. Clinical Anatomy 26, 1028–1030. issn : 08973806 (nov. 2013).

24. Parry, S. W., Ward, J. W. & Mathes, S. J. Vascular anatomy of the upper extremity muscles.

Plastic and reconstructive surgery 81, 358–65 (mar. 1988).

25. Hwang, K., Han, J. Y. & Chung, I. H. Topographical anatomy of the anconeus muscle for use as a free flap. Journal of reconstructive microsurgery 20, 631–6. issn : 0743-684X (nov. 2004).

i. Introduction

26. Schmidt, C. C. et al. The anconeus muscle flap : Its anatomy and clinical application. Journal

of Hand Surgery 24, 359–369. issn : 03635023 (mar. 1999).

1

Medial triceps brachii free flap in lower limb

reconstructive surgery

Background— In lower extremity reconstruction over the last several decades, the plastic surgeon’s armamentarium has grown to include free muscle and fasciocutaneous flaps along with perforator and propeller flaps. In this study, we present results of lower limb reconstruction using the medial triceps brachii (MTB) free flap.

Methods— This is a retrospective study of a single surgeon’s series of MTB free flaps. Patient char-acteristics, wound characteristics and procedure details were analyzed. Complications, short and long-term outcomes, secondary procedures, duration of hospital stay and number of surgical procedures needed before wound healing, bone union and walk recovery were assessed.

Results— We identified 24 MTB flaps. The mean follow-up time was 33.9 ±13.6 months. There were 6 distal third leg, 7 ankle, 5 heel and 6 foot wounds. The mean defect size was 20 ±8 cm2. There were 8 patients in the acute phase of an open fracture (Gustilo III B), 6 patients with secondary cuta-neous necrosis after surgical procedure and 10 patients with chronic osteomyelitis. In all cases, bone was exposed. The median duration of the MTB free flap procedure was 5 [4–6.8] hours. There were 3 total flap losses. Two patients developed donor site hematomas. Three patients underwent secondary procedures for re-draping. Twenty MTB free flap procedures led to complete wound healing. In one case, an additional local flap was required, with satisfactory outcomes. Complete wound healing was achieved in 76.5 [42.5–124.5] days after the MTB procedure. Bone union and walk recovery were ob-tained, respectively, in 3 [3–5.5] and 3 [2–4.5] months after the bone reconstruction procedure for all patients.

Conclusion— This study shows satisfactory results compared to previously-described muscular or fasciocutaneous free flaps. The MTB is an interesting option to cover small- to medium-sized defects of the lower extremity.

Chapitre 1. Medial triceps brachii free flap in lower limb reconstructive surgery

1.1

Introduction

O

pen fractures and chronic defects of the ankle and foot require a well-fitted cover-age to allow a normal walk. A new free flap technique has been described using the medial triceps brachii (MTB) [1]. Preliminary single-center results have demonstrated its potential for the coverage of small to medium-sized defects [2]. This free flap represents a serious alternative to gracilis free flap or anterolateral thigh free flap for lower limb reconstruction when local flaps are un-available. It has several advantages. Its limited size provides a flap appropriate for distal leg, ankle and foot coverage. It is a denervated muscle flap that will atrophy over time, potentially improving contour and cosmetic outcomes without requiring multiple secondary procedures. Its harvest is easy and the procedure can be done using a two-team approach, in order to reduce operative time. Furthermore, direct closure is possible, thus avoiding the additional scar of a skin graft harvest [3]. The aim of this study was to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of the MTB muscle flap as a primary option in recon-structing small- and medium-sized ankle and foot defects.1.2 Material and methods

1.2.1 Charts and clinical examination

This retrospective clinical study protocol was performed following the local ethical guidelines. Inclu-sion criteria were: patients of all ages, of both sexes, operated on between March 2011 and July 2015, who underwent MTB free flap procedure to cover defects localized at the distal third tibial shaft, ankle and foot level in our department. A single surgeon performed all surgeries (V.C.). Demographic informa-tion, medical comorbidities, mechanism of injury, details of the wound, preoperative imaging, recip-ient vessel selection, complications, flap survival and associated procedures were recorded. Secondary reconstructive procedures and revision surgeries were also identified. Times to wound healing, bone union and walk recovery were recorded, along with the number of required procedures, and hospital-ization lengths of stay. An independent observer examined all patients and charts. A board-certified radiologist or orthopedic surgeon reviewed x-rays or imaging assessing radiographic bony union.

1.2.2 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Matlab (R2014a, The MathWorks®, Inc., Massachusetts, USA). Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard error (std) for normal distributions and as median [1st – 3rd quartiles] for non-normal distributions. Correlations between quantitative variables were assessed using Pearson or Spearman’s correlation coefficient, as appropriate. Inter-group

1.3. Results

ences were assessed using Student’s t-test or Mann Whitney’s U-test, as appropriate.

1.3

Results

1.3.1 Population

Twenty-four patients were identified with lower extremity injury and had a MTB free flap procedure during the study period, representing 30% of all free flaps in our department. All patients were in-cluded. There were 9 women and 15 men, mean age 46.2 ±13.3 years old at the time of surgery. Twenty-two patients ambulated independently before their injury. One patient had paraplegia due to spina bifida and another had peripheral immunologic neuropathy. Comorbidities were frequent, including tobacco use in 12 patients and diabetes in one patient. The 24 patients were addressed to our depart-ment at different stage of the care process and for different indications: 8 patients in the acute phase of an open fracture (Gustilo III B) (Group 1), 6 patients with secondary cutaneous necrosis after surgical procedure (Group 2) and 10 patients with chronic osteomyelitis (Group 3) (Table1.1). Over time, no trend to a specific indication was observed (Fig.1.1).

Etiology of the defect was mostly traumatic (75%). The most common mechanisms of injury were mo-torcycle accidents (33%) and falls (28%). In traumatic etiologies, 8 wounds were directly due to open fracture, 3 related to septic pseudarthrosis, and 7 were due to secondary disunion of open reduction and internal fixation of a closed fracture. Other etiologies of the defect were diabetes/neurologic in 3 cases, and iatrogenic in 3 cases. There were 6 distal third leg, 7 ankle, 5 heel, and 6 foot defects treated with free tissue transfer. The mean defect size was 20 ±8 cm2. At the time of admission, local infections were observed for 15 patients.

1.3.2 Surgical procedure

Concerning preoperative imaging, all patients with a traumatic injury history, tobacco use or no pal-pated peripheral pulse underwent angiography to evaluate lower extremity vessels. Wounds were man-aged with negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) up to the flap procedure date. The arterial anasto-mosis was end-to-side on the anterior tibial artery (10 patients), end-to-end on the anterior tibia artery (7 patients), end-to-side on the posterior tibial artery (6 patients) and end-to-end on the posterior tib-ial artery (1 patient). Two venous anastomoses were performed if possible (41.7%). In all cases, the anastomoses were done outside of the injured zone.

Duration of surgery was not significantly increased when two venous anastomosis were performed (p=0.14). The median duration of the MTB free flap procedure was 5 [4–6.8] hours. Procedure

du-Chapitre 1. Medial triceps brachii free flap in lower limb reconstructive surgery

Group 1 (n=8) Group 2 (n=6) Group 3 (n=10) Total (n=24)

Open fracture Secondary cutaneous Chronic

necrosis after surgical procedure osteomyelitis Trauma mechanism, n MCA 2 1 4 7 GSW 1 0 1 2 Crush injury 2 0 0 2 Fall 3 3 1 7 Non trauma*, n 0 2 1 6 Work accident, n 3 2 1 6

Location of soft tissue defect, n

Distal third leg 2 1 3 6

Ankle 3 2 2 7

Heel 0 0 5 5

Foot 3 3 0 6

Mean defect size , ±std, cm2 27 ±3 19 ±5 14 ±2 20 ±8

Admission, n

Primary 6 4 0 10

Secondary 2 2 10 14

Local infection at admission, n 0 5 10 15

Table 1.1 –Mechanism and wound characteristics in the three groups of patient.

MCA : motorcycle accident ; GSW : gun shot wound; * diabetes/neurologic or postsurgical chronic wound.

Figure 1.1 –Number of MTB free flap in each group on the observation period.

1.3. Results

Figure 1.2 –Learning curve of the MTB free flap procedure.

ration decreased significantly with the surgeon experience (rho = -0.89, p < 0.01) (Fig. 1.2). There was no statistical difference in terms of duration between a MTB free flap procedure with (5 [4.4–7.1] hours) or without (5 [3.9–6.6] hours; p=0.62) an associated bone reconstruction procedure. To avoid tension during skin closure, a dermal substitute was placed on anastomoses and grafted 3 weeks later if necessary (58.3%) (Fig.1.3).

When an infection occurred on orthopedic hardware, it was systematically removed (4 patients). In the case of chronic osteomyelitis without fracture, curettage was done (7 patients). Multiple bone samples were taken at each procedure and bacteriological analysis carried out. Patients were placed on an in-travenous antibiotics regimen following guidelines from our local expert bacteriological department (probabilistic association of piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin). When bacteriological results were obtained, targeted double therapy was continued for 6 to 8 weeks. Reconstruction of bone sub-stance loss was carried-out using an iliac bone graft in 4 cases, the technique of induced membranes [4] in 5 cases and with an inter-tibio-fibular graft (ITFG) in 2 cases. Delay between the two procedures in the induced membrane technique was in average 4 [2.8–6.3] months.

Median size of harvested MTB was 40 [27–52] cm2. There were 2 harvest complications: 2 hematomas, 1 requiring revision for hemostasis.

Chapitre 1. Medial triceps brachii free flap in lower limb reconstructive surgery

1.3.3 Short and long-term results, complications

The series presented 3 total necrosis of MTB free flap (12.5%). There was no significant difference be-tween these 3 patients and the 21 that healed regarding number of venous anastomoses, type of arterial anastomosis, delay before surgery (Table1.2). In these patients, wound healing was obtained with an-other procedure (one dermal substitute and two local flaps). Twenty MTB free flap procedures led to wound healing. In one case, an additional local flap was required, with satisfactory outcomes. No patient required flap debulking surgery but three underwent flap re-draping after an average of 18 ±11.5 months. In these 3 cases, the flap was localized on the calcaneus. One of these remodeling procedures led to a complete necrosis of the flap, requiring a secondary amputation, 2 years after the initial cover procedure.

The mean follow-up time was 33.9 ±13.6 months (Table1.3). Median time from reconstruction decision to soft tissue cover was 41 [28–55] days. Complete wound healing was achieved in 76.5 [42.5–124.5] days after the MTB procedure. Bone union and walk recovery were obtained in 3 [3–5.5] and 3 [2–4.5] months after the bone reconstruction procedure, respectively. Results regarding bone reconstruction

Figure 1.3 –42 years-old patient, who fell from a high point. (A,B) Distal third of tibial shaft and fracture were exposed. (C,D) Soft tissue and bone debridment was done and antibiotic cement was placed to fill the bony loss of substance. (E) Dermal substitute (*) was placed on the vascular pedicle of the MTB flap (§) to avoid tension during skin closure. (F) Wound healing at 1 month. (G,H,I) Wound and bone healing at 33 months.

1.3. Results

Patient a Patient b Patient c

Age (y) / gender 55/M 42/M 55/M

Tobacco 0 0 1

Wound Location Tibial pilon Foot Distal 1/3 tibia

Group 1 2 3

Delay to wound coverage (d) 39 75 Several years

Anastomosis type and location End-to-end on ATA End-to-end on ATA End-to-side on PTA

Number of veins 2 1 1

Duration of surgery (h) 7.25 4 3.5

Delay thrombosis (d) 1 13 3

Time to re-exploration (h) 2 NA NA

Table 1.2 –Characteristics for flap failure.

Abbreviations: y, years; d, days; h, hours; ATA, anterior tibial artery; PTA, posterior tibial artery; NA, not applicable

Group 1 (n=8) Group 2 (n=6) Group 3 (n=10)

Follow-up, mean ±std, months 34.6 ±15.6 26.7 ±9.1 37.6 ±13.7

MTB free flap as a first cover attempt, % 100 83.3 40

Delay between, median [1st–3rd quartiles]

Reconstruction team advice and MTB flap procedure, days 33.5 [28–43] 33 [19–49] 48 [35–81]

MTB flap procedure and complete wound healing, days 80.5 [41–93] 50 [35–123.3] 75 [48.5–212]

Injury and bone union, months 7.5 [3.5–14] 8.5 [6–10] 20 [19–21]

Bone reconstruction procedure and bone union, months 3 [3–4] 3 [2–7] 5 [4.3–6.5]

Injury and walk recovery, months 6.5 [3.5–12] 5.5 [3–8] 29.5 [22–43.5]

Bone reconstruction procedure and walk recovery, months 3 [3–4] 3 [2–3.8] 4 [1.5–8]

Long-term complications

Secondary amputation, n 0 0 1

Wound recurrence, n 0 0 1

Partial pseudarthrosis, n 0 0 1

Return to work, % 60 20 50

Table 1.3 –Care delays, time to wound healing, bone union, walk recovery and complications in each group

type are exposed in Table1.4. All of the 24 patients were able to walk at the time of the last follow-up. Long-term complications were partial pseudarthrosis in 1 patient and wound recurrence in the diabetic patient. Of 16 patients who were working before the injury, 7 returned to work. The patient with secondary amputation underwent prosthetic rehabilitation and returned to work.

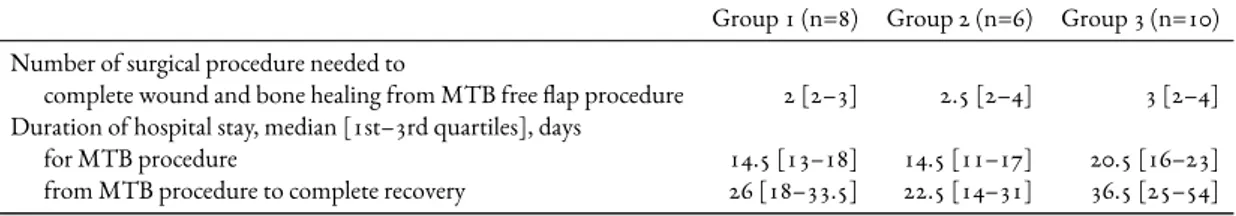

Median number of procedures to complete wound and bone healing from the MTB procedure was 3.5 [2–5] (Table 5). MTB free flap procedure was follow by a skin graft within 10 days, with a median total length of stay for this cover procedure of 15.5 [13–21] days. Median duration of hospital stay from

Induced membrane technique Iliac bone graft Inter-tibio-fibular graft

Time to bone union, median [1st–3rd quartiles], months 3 [2.5–3.5] 3 [2.5–7] 5 [3–7]

Time to walk recovery, median [1st–3rd quartiles], months 3 [2.8–5.3] 3 [2.5–3.5] 6 [5–7]

Chapitre 1. Medial triceps brachii free flap in lower limb reconstructive surgery

Group 1 (n=8) Group 2 (n=6) Group 3 (n=10) Number of surgical procedure needed to

complete wound and bone healing from MTB free flap procedure 2 [2–3] 2.5 [2–4] 3 [2–4] Duration of hospital stay, median [1st–3rd quartiles], days

for MTB procedure 14.5 [13–18] 14.5 [11–17] 20.5 [16–23] from MTB procedure to complete recovery 26 [18–33.5] 22.5 [14–31] 36.5 [25–54]

Table 1.5 –Number of surgical procedure and duration of hospital stay for each group

MTB procedure to complete wound and bone healing was 30 [19.5–38.5] days.

1.4

Discussion

This study represents an institutional review of lower extremity reconstruction using an MTB free muscle flap over a 4-year period. In our practice, we preferentially choose the MTB muscle flap for small- and medium-sized defects of the lower tibia, ankle and foot. The harvesting technique has been thoroughly described [2]. The donor site morbidity is very low with a very good patient satisfaction and no impairment of the elbow function (Delgove A, Weigert R, Casoli V. Evaluation of donor site morbidity after medial triceps brachii free flap for lower limb reconstruction, submitted for publica-tion). Its vascular pedicle is 2.9 cm long and if necessary the deep brachial vessels can also be dissected up to their origin from the brachial vessels and harvested with the medial collateral vessels, providing an 8–12 cm long ”extended” pedicle [1]. In this series, the MTB free flap allows to cover defects with me-dian size of 40 cm2. In the reconstructive microsurgeon’s armamentarium, this flap can cover defects of sizes smaller than the serratus free flap or the gracilis free flap [5,6]. Learning curve was signifi-cant (9.3 hours for the first flap versus 3 hours for the last flap of the series). This result is in line with published reports of free flap procedures in lower extremity reconstruction [7,8]. When an infection occurred on orthopedic hardware, it was systematically removed (4 patients) in agreement with local multidisciplinary recommendations and literature [9].

We performed two venous anastomoses each time it was possible, and this did not impact surgical time. It was always possible to find two veins in the vascular pedicle of the flap but sometimes the recipient vessels were not adequate to perform two venous anastomoses. Heidekrueger et al. have done a com-plete review of literature about this debated subject [7,10–13]. Some authors recommend one venous anastomosis arguing that venous thrombosis results from low blood velocity and more than one anas-tomosis would reduce the venous flow and thus increase the risk of forming venous thrombosis. On the other hand, to enhance venous drainage and especially to provide a rescue venous drainage if one of the venous anastomoses occludes, other authors postulate the use of two or more venous anastomoses. Actually, we performed two venous anastomoses if these conditions were met: two veins are present on the pedicle, two recipient veins are available and suitable.

Our flap loss rate of 12.5% and overall lower extremity salvage rate of 95.8% is in line with published

1.4. Discussion

reports of free flap survival in lower extremity reconstruction. We did not identify any significant pre-dictive factor of flap loss.

The first patient was 55 years old and admitted after a motorcycle accident with an open tibial pilon fracture Gustilo IIIa. He had no comorbidity. Skin necrosis occurred after open reduction-internal fixation (ORIF) and coverage was performed 39 days after bone exposure. End-to-end arterial anasto-mosis on the anterior tibial artery and two venous anastomoses were performed. Venous congestion occurred at day 1 and day 3 and flap failure occurred notwithstanding 2 procedures to redo the venous anastomosis within 2 hours of clinical congestion. Wound healing was obtained using a dermal sub-stitute. The patient had a bone graft three months after wound healing, through another surgical approach and had a delayed bone union (11 months).

The second patient was 42 years old and had secondary skin necrosis after tibiotalar arthrodesis proce-dure. He had no comorbidity. Flap procedure was done 75 days after bone exposure associated with hardware removal. End-to-end arterial anastomosis on the anterior tibial artery and one venous anas-tomosis were done. Venous congestion and flap necrosis occurred 13 days after surgery, and no attempt for anastomosis refection was done. A distally based sural flap was performed one month later, leading to wound healing in 19 days. Arthrodesis union was obtained in 6 months, allowing non-painful walk. The third patient was 55 years old and a heavy smoker (40 pack-years) with peripheral arterial disease. He had chronic tibial exposure for several years, next to a 30-year old open fracture. Pre operative imaging showed a developed collateral circulation in the entire lower limb but a good flow in a non-stenotic posterior tibial artery. He sustained two successive free flap failures with an anterolateral thigh free flap (arterial thrombosis at day 1 and unsuccessful refection of anastomoses) and an MTB free flap. End-to-side arterial anastomosis on the posterior tibial artery and 1 venous anastomosis were done. Arterial thrombosis occurred at day 2. Beyond this third arterial thrombosis, no attempt for re exploration was done. In the end, delayed wound healing was obtained 10 months after the surgery, using a local fasciocutaneous flap associated with dermal substitute and medical wound care.

Two risk factors described in the literature were found: long operative time (7.25 hours) for the first patient and tobacco use in the month preceding the microsurgery for the third patient [14].

In the literature, the highest failure rates concern the reconstruction of lower limbs. Sakurai et al. has shown that the arteriovenous pressure gradient for a lower-limb free flap is significantly lower than that for a free flap located elsewhere [15]. This elevated venous pressure accounts for the poor perfusion of lower limb flaps.

Our time to reexploration for the first patient was as reduced as possible, in accordance with literature, but did not avoid flap failure [16].

In our series, 3 patients required flap re-draping to allow normal walk recovery. Their flaps were placed on heel and were shearing on the bone, leading to difficulties for footwear and normal walk. The calcaneus has a particular curved shape and when the free flap is initially placed on it, it should not be

Chapitre 1. Medial triceps brachii free flap in lower limb reconstructive surgery

positioned too tight in order to avoid vascular tension. After flap healing, tissues are more elastic and tension is reduced, and the flap is then shearing on the calcaneus. This problem is well identified for muscular and fasciocutaneous flaps in weight-baring areas of the heel [17,18]. Debulking of free flap on the ankle and foot is frequently required but there is little data on the need of re-draping [19,20]. A complete necrosis of one of this re-draped flap occurred, probably due to an invasive mobilization of the flap 18 months after the initial procedure. Different studies suggest a neovascularization of muscle flap from the bed wound that can provide blood supply and survival in cases of main pedicle lesions [21–23]. When the flap is detached from the base, this supply may be cut off and lead to flap necrosis. In the acute trauma group, our median delay to cover was 41 days. 95.8% of patients with acute lower extremity wounds requiring microsurgical reconstruction did not receive soft tissue coverage within 7 days due to primary trauma, physiologic instability, patient comorbidities, or orthopedic and plastic surgery operative backlog.

Consequences of delayed coverage are still open to debate, but early studies concerning open lower limb fractures suggest that soft tissue coverage should be carried out as soon as possible, and that de-lays to flap surgery above seven days lead to higher infection rates [24]. More recent studies do not significantly report higher infection or flap loss rate in case of delayed coverage [25]. However, others recent studies demonstrate the other way [26,27].

Delay from injury to bone union was 7.5 to 8.5 months in Group 1 and 2 patients, widely depending on delay from injury to bone reconstruction procedure. Indeed, once the bone reconstruction procedure was done, 96% of our patients obtained bone union at 3 to 5 months, in accordance to the literature [28].

This study has limitations inherent to a retrospective review. There is no control group leaving con-clusions to be drawn from comparisons to the current literature on the topic. A direct comparison between two flap types in lower extremity reconstruction remains challenging due to the extreme het-erogeneity of patient comorbidities, mechanisms of injury, wound defects, and reconstructive options as well as the sample size needed to detect a meaningful difference between two reconstructive options. Strengths of this study are the original series report of this new technique and the long follow-up. It confirms the safety and efficacy of the MTB free flap as a primary option in reconstructing ankle and foot defects.

1.5 Conclusion

Wound healing, osteomyelitis treatment, bone union and walk recovery are obtained in adequate delay with an MTB free flap procedure. The harvest is simple and there is a reliable neurovascular pedicle. Furthermore, the donor site morbidity is low. These different points make the MTB a very attractive option to cover small- to medium-sized defects of the lower extremity.

References

References

1. Piquilloud, G., Villani, F. & Casoli, V. The medial head of the triceps brachii. Anatomy and blood supply of a new muscular free flap : the medial triceps free flap. Surgical and radiologic

anatomy : SRA 33, 415–20. issn : 1279-8517 (juil. 2011).

2. Delgove, A. et al. Medial triceps brachii free flap in reconstructive surgery : a prospective study in eight patients. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery 135, 275–82. issn : 1434-3916 (fév. 2015).

3. Delgove, A., Weigert, R. & Casoli, V. Evaluation of donor site morbidity after medial tri-ceps brachii free flap for lower limb reconstruction. in review.

4. Masquelet, A. C., Fitoussi, F., Begue, T. & Muller, G. P. [Reconstruction of the long bones by the induced membrane and spongy autograft]. Annales de chirurgie plastique et

esthe-tique 45, 346–53. issn : 0294-1260 (juin 2000).

5. Mastroianni, M. et al. Lower extremity soft tissue defect reconstruction with the serratus an-terior flap. Microsurgery 34, 183–7. issn : 1098-2752 (mar. 2014).

6. Franco, M., Nicoson, M., Parikh, R. & Tung, T. Lower Extremity Reconstruction with Free Gracilis Flaps. Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery. issn : 0743684X. doi :10 . 1055 / s -0036-1597568. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28024305> (déc. 2016).

7. Heidekrueger, P. I., Ehrl, D., Heine-Geldern, A., Ninkovic, M. & Broer, P. N. One versus two venous anastomoses in microvascular lower extremity reconstruction using gracilis muscle or anterolateral thigh flaps. Injury 47, 2828–2832. issn : 00201383 (déc. 2016).

8. Wong, A. K. et al. Analysis of risk factors associated with microvascular free flap failure using a multi-institutional database. Microsurgery 35, 6–12. issn : 1098-2752 (jan. 2015).

9. Patel, K. M., Seruya, M., Franklin, B., Attinger, C. E. & Ducic, I. Factors Associated With Failed Hardware Salvage in High-Risk Patients After Microsurgical Lower Extremity Re-construction. Annals of Plastic Surgery 69, 399–402. issn : 0148-7043 (oct. 2012).

10. Chen, W. F., Kung, Y.-P., Kang, Y.-C., Lawrence, W. T. & Tsao, C.-K. An old contro-versy revisited-one versus two venous anastomoses in microvascular head and neck reconstruc-tion using anterolateral thigh flap. Microsurgery 34, 377–83. issn : 1098-2752 (juil. 2014). 11. Dornseifer, U. et al. Less Is More ? Impact of Single Venous Anastomosis on the Intrinsic

Transit Time of Free Flaps. 1. doi :10.1055/s-0036-1593768 (2016).

12. Hanasono, M. M., Kocak, E., Ogunleye, O., Hartley, C. J. & Miller, M. J. One versus two venous anastomoses in microvascular free flap surgery. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 126, 1548–57. issn : 1529-4242 (nov. 2010).

Chapitre 1. Medial triceps brachii free flap in lower limb reconstructive surgery

13. Lorenzo, A. R. et al. Selection of the recipient vein in microvascular flap reconstruction of the lower extremity : analysis of 362 free-tissue transfers. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic

surgery : JPRAS 64, 649–55. issn : 1878-0539 (mai 2011).

14. Perrot, P., Bouffaut, A. L., Perret, C., Connault, J. & Duteille, F. Risk factors and therapeutic strategy after failure of free flap coverage for lower-limb defects. Journal of

Recons-tructive Microsurgery 27, 157–162. issn : 0743684X (2011).

15. Sakurai, H. et al. Hemodynamic alterations in the transferred tissue to lower extremities.

Mi-crosurgery 29, 101–6. issn : 1098-2752 (2009).

16. Bui, D. T. et al. Free flap reexploration : indications, treatment, and outcomes in 1193 free flaps.

Plastic and reconstructive surgery 119, 2092–100. issn : 1529-4242 (juin 2007).

17. Noever, G., Brüser, P. & Köhler, L. Reconstruction of heel and sole defects by free flaps.

Plastic and reconstructive surgery 78, 345–52. issn : 0032-1052 (sept. 1986).

18. Heymans, O., Verhelle, N. & Lahaye, T. Covering small defects on the weight bearing sur-faces of the foot : The free temporal fasciocutaneous flap. British Journal of Plastic Surgery 58, 460–465. issn : 00071226 (2005).

19. Nelson, J. A. et al. Striving for Normalcy after Lower Extremity Reconstruction with Free Tis-sue : The Role of Secondary Esthetic Refinements. Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery 32, 101–108. issn : 10988947 (2015).

20. Lin, T.-S. & Quing, R. Long-Term Results of a One-Stage Secondary Debulking Procedure after Flap Reconstruction of the Foot. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 138, 923–930 (oct. 2016). 21. Khoo, C. T. K. & Bailey, B. N. The behaviour of free muscle and musculocutaneous flaps after early loss of axial blood supply. British Journal of Plastic Surgery 35, 43–46. issn : 14653087 (1982).

22. Kissun, D., Shaw, R. J. & Vaughan, E. D. Survival of a free flap after arterial disconnection at six days. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery 42, 163–5. issn : 0266-4356 (avr. 2004).

23. Yoon, A. P. & Jones, N. F. Critical time for neovascularization/angiogenesis to allow free flap survival after delayed postoperative anastomotic compromise without surgical intervention : A review of the literature. Microsurgery 36, 604–612. issn : 07381085 (oct. 2016).

24. Fischer, M. D., Gustilo, R. B. & Varecka, T. F. The Timing of Flap Coverage , and Intra-medullary Nailing in Patients of the Tibial Shaft with Extensive Who Have a Fracture Injury *.

The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 1316–1322 (1991).

25. Raju, A., Ooi, A., Ong, Y. & Tan, B. Traumatic Lower Limb Injury and Microsurgical Free Flap Reconstruction with the Use of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy : Is Timing Crucial ?

Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery 30, 427–430 (avr. 2014).

References

26. Liu, D. S. H., Sofiadellis, F., Ashton, M., MacGill, K. & Webb, A. Early soft tissue co-verage and negative pressure wound therapy optimises patient outcomes in lower limb trauma.

Injury 43, 772–778 (juin 2012).

27. Olesen, U. K. et al. A review of forty five open tibial fractures covered with free flaps. Analysis of complications, microbiology and prognostic factors. International orthopaedics 39, 1159–66. issn : 1432-5195 (juin 2015).

28. Pelissier, P., Boireau, P., Martin, D. & Baudet, J. Bone reconstruction of the lower extre-mity : complications and outcomes. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 111, 2223–9. issn : 0032-1052 (juin 2003).

2

Evaluation of donor site morbidity after

medial triceps brachii free flap for lower

limb reconstruction

Background— The medial head of the triceps brachii muscle (MTB) free flap is an attractive solu-tion to cover small to medium defects of the lower limb. This muscular head has no well-identified function, suggesting minimal impact of its removal on elbow mobility. The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and reliability of the harvest procedure and the functional and cosmetic morbidity of this donor site.

Methods— All consecutive MTB free flaps were performed for reconstructive surgery of the lower limb between 2011 and 2015. Patients and their records were retrospectively examined. Functional results were evaluated by assessing elbow extension strength using a dynamometer and with a Quick-DASH questionnaire. Elbow extension strength of our patients was compared to the strength of a healthy cohort. Cosmetic results were assessed using the POSAS observer and patient scales.

Results— 24 patients were followed up postoperatively for an average of 33.9 months. In all cases, the MTB was harvested on the non-dominant arm. No major complication (in particular, no ulnar nor radial nerve injury) occurred during harvest. No patient complained of elbow pain or reduction in strength. Elbow extension was complete in all patients and the median strength was calculated at 92.3% of the contralateral arm, similar to a healthy control population (89.9% [85.5–98.6], p=0.71). The POSAS scale scored an average 8.6 ±3.3 for the observer and 10 ±4.3 for the patient. Cosmetic results using the POSAS scale were satisfactory in all patients.

Conclusion— Objective evaluation of patients who underwent a MTB free flap for limb reconstruc-tion shows no impact of the harvesting procedure on elbow extension. Patient satisfacreconstruc-tion with the donor site was high. It appears that this surgery is safe, aesthetically acceptable, and preserves elbow function.

Chapitre 2. Evaluation of donor site morbidity after medial triceps brachii free flap for lower limb reconstruction

2.1 Introduction

O

pen fractures and chronic defects of the ankle and foot require adapted coverage to allowfor normal walk. A new free flap technique has recently been described using the medial triceps brachii (MTB) [1]. This muscle is vascularized by the deep brachial artery and the middle collateral artery. Preliminary single-center results have demonstrated its potential for the cover-age of small to medium-size defects [2]. There have been significant advancements in lower extremity reconstruction over the last several decades, and the plastic surgeon’s armamentarium has grown to include free muscle and fasciocutaneous flaps along with local perforator and propeller flaps. Lower limb reconstruction is often a long process entailing several hospitalizations and surgical procedures, which is why patients have to be fully involved in the reconstruction process. Flap choice depends on patient and wound characteristics, but must also take into consideration donor site morbidity. To ob-tain complete patient adherence to the proposed strategy, benefits and drawbacks of the chosen flap have to be thoroughly explained [3]. Triceps brachii is one of the longest muscles of the upper limb. It acts as the main extensor of the forearm across the elbow joint [4]. The medial head of this muscle however, has no well-identified function described in the literature. Nevertheless, morbidity of MTB free flap harvesting has to be evaluated. The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and reliability of the harvest procedure and post-operative donor site functional and cosmetic morbidity.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Study design

This was a singe-center retrospective study. After receiving approval of the institutional ethics commit-tee, all consecutive patients who underwent a MTB free flap between 2011 and 2015 in our institution were included. Functional and cosmetic outcomes were evaluated at the date of retrospective analysis. All patients provided written informed consent.

2.2.2 Health record analysis

Data concerning patient characteristics at the moment of surgery, wound size, surgical technique and complications were retrospectively retrieved from our institution’s electronic medical record system.