O

pen

A

rchive

T

OULOUSE

A

rchive

O

uverte (

OATAO

)

OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and

makes it freely available over the web where possible.

This is an author-deposited version published in :

http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/

Eprints ID : 13234

To link to this article :

DOI:10.1016/j.ijar.2014.07.004

URL :

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijar.2014.07.004

To cite this version :

Ciucci, Davide and Dubois, Didier and Lawry, Jonathan

Borderline vs. unknown : comparing three-valued representations of imperfect

information. (2014) International Journal of Approximate Reasoning, vol. 55

(n° 9). pp. 1866-1889. ISSN 0888-613X

Any correspondance concerning this service should be sent to the repository

administrator: staff-oatao@listes-diff.inp-toulouse.fr

Borderline

vs.

unknown:

comparing

three-valued

representations

of

imperfect

information

Davide Ciucci

a,

Didier Dubois

b,

Jonathan Lawry

caDipartimentodiInformatica,SistemisticaeComunicazione,UniversitàdiMilano-Bicocca,VialeSarca336/14, 20126Milano,Italy

bIRIT,UniversitéPaulSabatier,118routedeNarbonne,31062Toulousecedex4,France

cDepartmentofEngineeringMathematics,UniversityofBristol,Queen’sBuilding,UniversityWalk,BristolBS81TR,UnitedKingdom

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

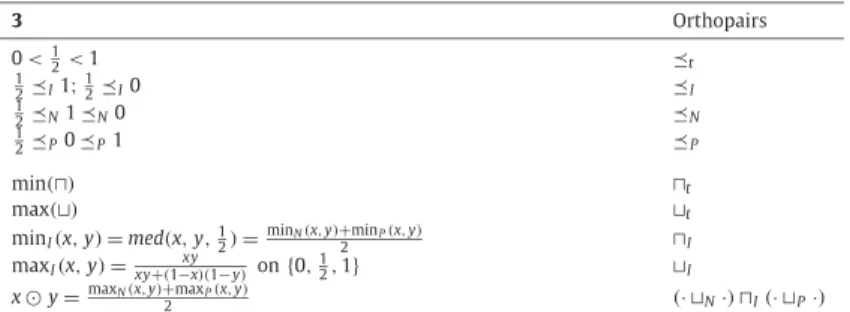

Keywords: Kleenelogic Partialmodels Orthopairs Vagueness Incompleteinformation Belnaplogic SupervaluationsIn this paper we compare the expressive power of elementary representation formats for vague,incomplete or conflicting information. Theseinclude Boolean valuation pairs introduced by Lawry and González-Rodríguez, orthopairs of sets of variables, Boolean possibility and necessity measures, three-valued valuations, supervaluations. We make explicittheir connectionswith strong Kleene logicand with Belnaplogicof conflicting information. The formal similarities between 3-valued approaches to vagueness and formalismsthathandleincompleteinformationoftenlead toaconfusionbetweendegrees oftruth and degrees ofuncertainty. Yet thereare important differencesthat appear at theinterpretivelevel:whiletruth-functionallogicsofvaguenessareacceptedbyapartof thescientificcommunity(evenifquestionedbysupervaluationists),thetruth-functionality assumptionofthree-valuedcalculiforhandlingincompleteinformationlooksquestionable, comparedtothenon-truth-functionalapproachesbasedonBooleanpossibility–necessity pairs.Thispaperaimstoclarifythesimilaritiesanddifferencesbetweenthetwosituations. Wealsostudytowhatextentoperationsforcomparingandmerginginformationitemsin theformoforthopairscanbeexpressedbymeansofoperationsonvaluationpairs, three-valuedvaluationsandunderlyingpossibilitydistributions.

1. Introduction

Three-valuedlogicshavebeenusedfordifferentpurposes,dependingonthemeaningofthe thirdtruth-value.Among them,Kleenelogic[29] istypicallyassumedtodeal withincompleteknowledge,withthethird truth-valueinterpretedas unknown.Anotherpossibilityistointerprettheadditionaltruth-valueasborderline,asameansofrepresentingborderline casesforvaguepredicates[28].ItisthentemptingtouseKleenelogicasasimplelogicofnon-Booleanpredicatesasdone recentlybyLawryandGonzález-Rodríguez[32].Theyintroducedanewformalismtohandlethree-valuedvaguepredicates bymeans ofupperandlower Booleanvaluations.Basicthree-valuedconnectivesofconjunction, disjunctionandnegation canbeexpressedbycomposingBooleanvaluationpairs.Moreover,they showedhowtorecovertheconnectivesofBelnap 4-valuedlogicofconflictintermsofBooleanvaluationpairs.Theyalsouseanotherequivalentrepresentationconsistingof pairsofsubsetsofatomicvariablesthataredisjointwhentheyrepresentKleenevaluations. LawryandTang[33]interpret

thesupervaluationapproachtovaguenessintermsofgeneralnon-truth functionalvaluation pairsrespectingBoolean tau-tologies.

However,three-valuedvaluationsalsoencodeBooleanpartialmodels,likeforinstanceinpartiallogic[6].Orthopairsof variable sets then representthe sets ofBoolean variables that are knownto be trueand ofthose that are knownto be false. Thethirdtruth-valuethenrefers totheunknown. Thenaturalgeneralisationofpartialmodelsconsistsofepistemic sets,understoodasnon-emptysubsetsofinterpretationsofaBooleanlanguage,representingtheinformationpossessedby an agent, which can be viewedasall-or-nothing possibilitydistributions [45].Such possibility distributions generalise to formulasintheformofpossibilityandnecessityfunctions[42,18].Possibilitytheory,eveninitsall-or-nothingform,isnot truth-functional,whichexplainsapparentanomaliesinKleenelogicforhandingincompleteinformation[19].Morerecently LawryandDubois[31]proposedoperationsformergingvaluationpairsandstudytheirexpressionintermsofthree-valued truth-tables,aswellaspairsofsubsetsofvariables.

In thispaper, wefocus ontheuseoforthopairs ofsubsetsofvariables forhandlingvagueor incompleteinformation. We compare the expressivepowerof three-valuedvaluations, Boolean valuation pairs, andorthopairs. The aim isto ex-posethedifferencesbetweenthesethreerepresentationtools.Incontrastwiththesetruth-functionalrepresentationtools, we considernon-truthfunctionalones,such aspossibility–necessitypairsandsupervaluations,respectivelyusedfor mod-elling incompleteinformationandvagueness, andshow theirformal similarities,aswellastheirdifferenceswithBoolean valuation pairs.Besides, we show that orthopairs are more difficult tohandle than three-valuedvaluations andBoolean valuationpairswhenitcomestoevaluatinglogicalexpressionsinKleenelogic,evenifthethreenotionsareinone-to-one correspondence.

We then study informational orderingsand combination rules for the merging of pieces of information that can be expressed intermsof orthopairs.Again, some discrepanciesare highlighted intheir expressivepowercomparedto other representationformats,especiallypossibilitydistributions.

Thispaperisstructuredasfollows.Thenext sectionpresentsthreedifferentwaysofencodingthree-valuedvaluations. Section3presentstwousesoftheserepresentations,formodelling borderlinecasesofvaguepredicates,andforincomplete Booleaninformation.Section4caststheminthesettingofpossibilitytheory.Thestrongformalsimilaritybetween super-valuation pairsandpossibility–necessitypairsisalsohighlighted.Section5extendstheserepresentationssoastoaccount forconflictinaccordancewithBelnaplogic.Wethenobtaingeneralised valuationpairsthatcanbeinconsistent,andgeneral pairsofsubsetsofvariablesthatcanoverlap(onvariablesforwhichknowledgeisinconsistent).Theproblemofimporting therecursivedefinitionsofconsistentpairsofvaluationsforlogicalexpressionsintotheframeworkoforthopairsofvariables isdiscussedindetailinSection6.Section7considersvariousnotionsoforderingrelationsbetweenthree-valuedvaluations andvariouscombinationrules.Itstudieswhethertheycanbeencodedinthethreeformatsproposedinthispaper.Finally inSection 8,wecheck whetherthesecombinationoperationsareexpressible intermsofthefusionofgeneralsubsetsof interpretations.

2. Three-valuedvaluations

Let

A

beafinitesetof(propositional)variables.Wedenoteby3 theset{0,

12

,

1},equippedwithtotalorder0<

1 2<

1,looselyunderstoodasasetoftruth-valueswith0 and1 respectivelyreferringtofalseandtrue.

Definition2.1.Athree-valuedvaluation isamapping

τ

: A

→

3.Wedenoteby3A thesetofthree-valuedvaluations.Aparticularsubsetof3A consistsofBooleanvaluations(or inter-pretations),i.e.mappings w

: A

→ {0,

1};wedenotebyΩ = {0,

1}Athesetofallsuchvaluations.

Inthissectionweintroducetwoalternativerepresentationsofthree-valuedvaluationstogetherwiththeirextensionsto logicalexpressionsinKleenelogic:orthopairsandorderedpairsofBooleanvaluations.

2.1. Representationsofthree-valuedvaluations

Definition2.2.Byanorthopair,wemeanapair

(

P,

N)

ofdisjointsubsetsofvariables: P,

N⊆ A

andP∩

N= ∅.

A three-valued valuation

τ

: A

→

3 induces an orthopair asfollows: a∈

P ifτ

(

a)

=

1, a∈

N ifτ

(

a)

=

0.So P and N standforpositive andnegativeliterals, respectively.Conversely, givenan orthopair(

P,

N)

we candefine the following three-valuedfunction:τ

(

a) =

0 a∈

N 1 a∈

P 1 2 otherwiseThereisindeedabijectionbetweenorthopairsandthree-valuedvaluations.

Lawryand González-Rodríguez[32] proposeyetanotherrepresentationofternaryvaluations

τ

bymeans ofconsistent Booleanvaluationpairs:τ∈3A (v≤v)

(P,N)

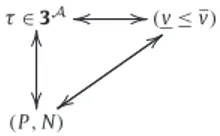

Fig. 1. Bijection among three-valued functionsτ, orthopairs(P,N)and pairs of Boolean functions v≤v.

Table 1

Kleenestrongconjunction⊓.

⊓ 0 1 2 1 0 0 0 0 1 2 0 1 2 1 2 1 0 12 1

Definition2.3.Aconsistent Booleanvaluationpair(BVP)isapair

E

v= (

v,

v)

∈ Ω

2ofBooleanvaluationson{0,

1},suchthatv

≤

v holdspointwisely.v iscalledalowerBooleanvaluation,andv isanupperBooleanvaluation.Athree-valuedvaluationinducesaconsistentBVPasfollows.Forvariablesa

∈ A:

•

ifτ

(

a)

=

1 thenv(

a)

=

v(

a)

=

1;•

ifτ

(

a)

=

0 thenv(

a)

=

v(

a)

=

0;•

ifτ

(

a)

=

12 then v(

a)

=

0,v(

a)

=

1.Clearlytheproperty v

≤

v holdsandexpressesconsistencyoftheBVP.Thereisalsoaone-to-onecorrespondencebetween consistentBVP’ssuchthatv≤

v andorthopairs(

P,

N),

definedby P= {

a∈ A

:

v(

a)

=

v(

a)

=

1},N= {

a∈ A

:

v(

a)

=

v(

a)

=

0},andv(

a)

=

0,v(

a)

=

1 ifa∈

/

P∪

N.Thecondition P∩

N= ∅

isequivalently expressedby v≤

v usingBVPs.Obviously,τ

(

a)

=

v(a)+2v(a).So, in the casewhere v

≤

v there are bijections between three-valued functions, orthopairs andconsistent BVP’s as illustratedbyFig. 1.2.2.Kleenelogicexpressions

Inthispaperwefocusonthesimplestthree-valuedlogicknownasKleenelogic[29].Kleenelogicusestwoconnectives: anidempotentconjunction

⊓

andtheinvolutivenegation′.Connectivesaredefinedtruth-functionally,asfollows(seealso Table 1):Definition2.4.Negationandconjunctionarerespectivelydefinedby:

•

0′=

1,1′=

0,12′=

12,whichreads

τ

(φ

′)

=

1−

τ

(φ).

•

τ

(φ ⊓ ψ )

=

min(τ

(φ),

τ

(ψ )).

Basedontheseconnectives,wecanconstructalanguage

L

K.ThelanguageL

K isrecursivelygeneratedby:a∈ L

K,

φ

′∈

L

K,

φ ⊓ ψ ∈ L

K.Thecorrespondingdisjunctionisφ ⊔ ψ

thatstandsfor(φ

′⊓ ψ

′)

′suchthatτ

(φ ⊔ ψ )

=

max(τ

(φ),

τ

(ψ ))

=

τ

((φ

′⊓ ψ

′)

′).

1Thislanguage definesaclass ofthree-valuedfunctionswhoseexpressions are thesameasthoseof Booleanlogic,but forthepossibilityofsimplifyingtermsoftheforma

⊔

a′ anda⊓

a′.Remarkably,thereisnotautologyinKleenelogic,that is,no constantfunction f:

3A→

3 taking thevalue{1}

that canbe expressed inthe Kleene logiclanguage. In factany propositioninKleenelogictakesvalue 12 ifallitsvariablestakevalue 12.UpperandlowerBooleanvaluationscanbeextendedtoformulas

φ

builtfromvariablesandKleeneconnectives′,

⊓,

⊔:

v

¡φ

′¢ =

1−

v(φ);

(1) v(φ ⊓ ψ ) =

min¡

v(φ),

v(ψ )¢;

v(φ ⊓ ψ ) =

min¡

v(φ),

v(ψ )¢;

(2) v(φ ⊔ ψ ) =

max¡

v(φ),

v(ψ )¢;

v(φ ⊔ ψ ) =

max¡

v(φ),

v(ψ )¢.

(3)Table 2

Borderlinevs.unknown.

Name Tall Single

John 1 1

Paul Borderline 1

George 0 Unknown

Ringo 0 0

Itcanbecheckedthatif

τ

(φ)

iscomputedbymeansofKleenetruthtablesandthepair(

v,

v)

iscomputedbytheabove identitiesthen,•

ifτ

(φ)

=

1 thenv(φ)

=

v(φ)

=

1;•

ifτ

(φ)

=

0 thenv(φ)

=

v(φ)

=

0;•

ifτ

(φ)

=

12 then v

(φ)

=

0,v(φ)

=

1.Furthermore,itcanbe shownby inductionthatthethree-valuedvaluation

τ

canbe definedasanarithmetic meanof v,

v forallexpressionsinKleenelogic:Proposition2.1.Foranyformula

φ

formedusingtheKleeneconnectivesitholdsthatτ

(φ)

=

v(φ)+2v(φ).Proof. Itiseasytocheckthatforatomicpropositions

τ

(

a)

=

v(a)+2v(a).Byinduction,wecanprovebyenumeratingall the possiblesituations,that•

τ

(φ

′)

=

1−

τ

(φ)

=

1−

v(φ)+v(φ)2

=

v(φ′)+v(φ′)

2 ,

•

τ

(φ ⊓ ψ )

=

min(v(φ)+2v(φ),

v(ψ )+2v(ψ ))

=

min(v(φ),v(ψ ))+2min(v(φ),v(ψ )).✷

The question of whetherthe evaluationof Kleene expressions can be obtainedby combining orthopairs ismuch less obviousandwillbeaddressedinSection6.However,wefirstpointouttwoareaswhereKleenelogichasbeenused.

3. Three-valuedlogic:vaguenessvs.incompleteinformation

Thereare twomaininterpretationsofKleenelogic:itprovidesa representationofborderlinecasesinthemodelling of vagueness,oritmayaccountforreasoningunderincompleteknowledge.

3.1. Kleenelogicasanelementaryframeworkforvaguepredicates

The existence ofborderline caseswhenevaluating thetruth statusofpropositions issupposed tobe one ofthemain characteristics ofvaguenessinnaturallanguage [28].Inthe mostelementaryrepresentationofvaguenesswe canassume variablestobethree-valued,withthethirdtruthvalue 21 beinginterpretedasborderline.Inthisapproach,eachthree-valued valuationisacompletemodel,thatis,wherebyeachvariableisassignedatruthvalue(false,trueorborderline).Thisisthe approachofLawryand González-Rodríguez[32],whocastthiselementaryidealised modelofvaguepropositionsinKleene three-valuedlogic[29].While 12 meansborderline,thetruth-values1and0respectivelymeanclearlytrue and clearlyfalse. Inotherwords,thevalue 12 indicatesasituationwhereapropositionisneitherclearlytruenorclearlyfalse.Itiseasilyseen that the lower valuation v evaluates whethera propositionisclearlytrue ornot, while theuppervaluation v evaluates whetherapropositionisatleastborderlinetrueornot.Inthisview,anorthopair

(

P,

N)

isinterpretedasfollows:P isthe set ofvariablesthat are clearlytrue in thesituationunderconcern, N theset ofclearlyfalse ones,andthe remainderare consideredtobeborderline.The corresponding three-valued set-theory is a very elementary variant of fuzzy set theory [44] where sets possess centralelementsandperipheralonesasfirststudied,inthescopeoflinguistics,byGentilhomme[25].Forinstance,inthe scale

[0,

250]cm,menheightsfrom1.80cmupareconsideredtypicaloftall heights,hencecentral,whileheightsbetween 1.70 to1.80cmcorrespondtoborderline casesoftall.So,thepredicatetall maybebetterdescribedasathree-valuedone than asa Booleannotion,assomepersons maybejudgedneitherclearlytall notclearlynottall (asopposed, e.g. toother clearcutpredicatessuchassingle,seee.g.,Table 2).Butthesepersonsmayaswellbejudgedatthesametimeperipherally tall andperipherallynottall,(theweakformsofoppositepredicatesoverlap)evenifnotclearlyso.Thiselementarymodelling ofborderlinecasesisdiscussedinthebookofShapiro[36,page64].Thethree-valuedsetting reflectstheopentextureofvaguepredicatesleadingtopropositionsthatcangoeitherway.Heelaboratesasupervaluationist approach ontop ofthethree-valuedsetting: theborderline truth-valueisthen understoodasreflecting thefact that the

truthstatusofthestatement tall(x) islikelytomovefromtruetofalseandback inconversational scores.Forinstance,in Table 2,Paulmayalternatively bedeclaredtall or nottall,becausehisheight liesbetween1.6 and1.8 meters.Ofcourse, thisisjust acoarseidealisationofthevaguenessphenomenon,infactthemostelementaryonemightthinkof,sincethe borderlineinterval

[1.6,

1.8]isquestionablyoverprecise.The clear-cut boundaries between the borderline area andthe truth andfalsity ones maybe found counterintuitive. However,itismaybeworthnotingthat Sainsbury[35]arguesagainsttheintroductionofhigherordervaguenessinterms ofborderlineborderlines,etc.Hesaysthatevenifyoudosuchathingtheimportantquestioniswhichcasesaredefinitely true andwhich are definitely false. And, following Shapiro [36], one may consider such precise boundaries as artefacts ofthe model,whoseaim issolelyto expose thepresence ofborderline casesin theextension of vaguepredicates. They donot representsomethingmeaningfulfortheunderstandingofnaturallanguages.Besides,evenifthetruth-functionality of Kleene logic of borderline has a well-founded algebraic setting (the so-called Kleene algebras), the adequacy of this assumption is widely questioned by supervaluationists,among others [22]. We will make no attempt hereto engage in thedebateregardinghigher-ordervaguenessandthelimitationsofthethree-valuedlogicofborderlinetoaccountforthe representationofvagueness. Instead,ourpurposeisonlytouseaverybasicrepresentationofnon-Booleanpredicates(as advocatedbyLawryandcolleagues)andcontrastitwiththelogicofunknown.

3.2.Kleenelogicandincompleteinformation

Theoriginalintuitionin[29]regardingtheinterpretationofthethirdtruth-value 12 correspondstotheideaofunknown insteadofborderline.Inthissection, weassume thatthethird truth-value 12 meansunknown,andrefers totheignorance about theactualBoolean truthvaluesofclassical binary propositionalvariables.The truth-tablesofKleene logicare then sometimesusedtopropagateincompleteknowledge.

Inmanyapplications,suchasrelationaldatabases[11],orlogicprogramming[23],weassumethat anagent expresses knowledgeonlyabout elementaryBooleanvariables.Inthedatabasearea,thevalue 12 iscalleda null value.Forinstance, inTable 2,thevariablepertainingtothepredicatesingle isBoolean,butitisnot knownwhetherGeorge issingleornot. However,thepredicatesingle isinnowayvague.Thisexampleillustratesthedifferencebetweenborderline andunknown.

An orthopair

(

P,

N)

then does not have the same meaning as in the previous Subsection 3.1. Here, P is the set of atomicpropositionsknowntobe true(intheusualsense),andN isthesetofatomicpropositionsknowntobe false.Clearly,A

\(

P∪

N)

representsvariablesonwhichtheagent hasnoknowledge.Notethatthisisformallythesameorthopairasin theprevioussection,anditcanagainbeencodedasathree-valuedvaluation.However,theintendedmeaningsoforthopairs arequitedifferent:inthevaguenesssituation,anorthopairrepresentscomplete knowledgeaboutanon-Boolean description, whilehereitrepresentsincompleteknowledgeaboutaBooleanpropositioninastandardpropositionallanguageL

equipped withusualconjunction,disjunctionandnegationconnectivesrespectivelydenotedby∧,

∨,

¬.

InthisBoolean language,theorthopair

(

P,

N)

correspondsto aconjunctionofliteralsinA

,i.e.,V

a∈Pa

∧

V

a∈N

¬

a.Atthesemanticlevel,

(

P,

N)

issometimescalledapartialinterpretationorpartialmodel.Usuallyinpartiallogic[6],thesame satisfiabilitydefinitionsasforBooleanvaluationsareappliedtopartialmodels,whichcanbequestioned[13].LetthesetofBoolean modelsofa formula

φ

(thatis,theset ofBooleanvaluationsthat makeφ

true) bedenoted by E= [φ].

An orthopair(

P,

N)

viewed asa partial modelcorresponds to a non-empty set E(P,N)= [

V

a∈Pa∧

V

a∈N

¬

a]

ofBooleanvaluations,namelyallBooleaninterpretations w thatcompletethepartialmodel.ABooleanvaluationw then cor-respondstoanorthopair

(

P,

Pc),

wherePc denotesthecomplementof P ,thatpartitionsthesetofpropositionalvariables;or,equivalently, w isthe only model ofa maximal conjunctionof literals

V

a∈Pwa

∧

V

a∈/Pw

¬

a.Boolean valuations thatcompleteanorthopair

(

P,

N)

canbe representedby(

Pw,

Pcw)

where P⊆

Pw andN∩

Pw= ∅.

Itisoftenthecase(e.g.inlogicprogramming)thataBooleanvaluation w issimplyrepresentedbythesubset Pw

= {

a∈ A

:

w(

a)

=

1}=

P ofpositiveliteralsitsatisfiesaspertheaboveexpression.Thisexposestheone-to-onecorrespondencebetween

Ω

and2A.Now,letussupposethatanagentexpressesknowledgebymeansofpositiveliterals, P

⊆ A.

Wecanhavetwoattitudes withrespecttotheothervariablesinA

\

P .First,theopenworldassumption.InthiscasenothingisassumedaboutA

\

P . Then the corresponding orthopair is(

P,

∅).

In contrast, underthe closed world assumption, itis supposed that what is notsaidtobetrueisfalse,thus N= A\

P contains thenegativefacts.Thiscorrespondstoselectingjustasinglevaluation(

P,

Pc)

amongallthepossibleonesinE(P,∅).NowletusturntotheuseofupperandlowerBooleanvaluationsinthiscontext.The lowervaluation v

(

a)

=

1 means thatvariablea isknowntobetrue,theuppervaluation v(

a)

=

0 meansthata isknowntobefalse,whilethecasewhere v(

a)

=

0 and v(

a)

=

1 corresponds tothe case whereit is unknown whethera is true or false.Very naturally,the pair(

v(

a),

v(

a))

representsthe setofpossible(Boolean)truth-valuesofa, accordingtothe availablestate ofinformation.The truth-tablesofKleenelogicarethenpreciselytheset-valuedextensionsoftheBooleantruth-tables[34,15],namely:¡

v(

a∧

b),

v(

a∧

b)¢ = ©

w(

a∧

b) :

v≤

w≤

vª

=

¡

min¡

v(

a),

v(

b)¢,

min¡

v(

a),

v(

b)

¢¢

¡

v(

a∨

b),

v(

a∨

b)¢ = ©

w(

a∨

b) :

v≤

w≤

vª

=

¡

max¡

v(

a),

v(

b)¢,

max¡

v(

a),

v(

b)

¢¢

¡

v

(¬

a),

v(¬

a)¢ = ©

w(¬

a) :

v≤

w≤

vª = ¡

1−

v(

a),

1−

v(

a)

¢

However, ifused to evaluate the knowledge about the truth orfalsity ofany Boolean formula, the recursive application of these definitions becomes counterintuitive in the incomplete information setting. Indeed, using Kleene logic (or the recursive formulas on the upper and lower Boolean valuations as in the previous section), one finds that for instance,

(

v(

a∧ ¬

a),

v(

a∧ ¬

a))

= (0,

1),ifτ

(

a)

=

12.However,undertheincompleteinformationsetting,since w

(

a)

canonlybetrueorfalse,thetruth-valuew

(

a∧ ¬

a)

isnecessarily0(knowntobe false).Andthiscanberetrieveddirectlybyapplyingthe set-valuedcalculustoallformulasφ,

namely,bycomputingV

(φ) =

©

w(φ) :

v(

a) ≤

w(

a) ≤

v(

a), ∀

a∈

A

ª,

ratherthatusingthetruth-tablesforconjunction, andnegationrecursively.Forinstance,

∀

v≤

v,

V(

a∧ ¬

a)

= {0}

(andnot{1,

0}providedbyKleenetruth-tables)since∀

w,

w(

a∧ ¬

a)

=

0.ItsuggeststhatthelackoftautologyinKleenelogiccanbe consideredsurprisinginthescope ofincompleteBooleaninformation:ifvariablesareBoolean,classicaltautologiesshould be preserved, evenifthetruth-valueofsome variablesis unknown.Forinstance,fromTable 2 wedonot knowwhether Georgeissingle,butitisalwaystruethatheis“singleornotsingle”.Theexplanationofthisapparentanomalyisclarified inSection4.3.So,whilethereisaone-to-onecorrespondencebetweenpartialmodelsrepresentingincompleteinformationand three-valuedvaluations(relyingonthebijectionbetween 3 andtheset

{{0},

{1},

{0,

1}}ofnon-emptysubsetsoftheunitinterval), Kleene truth-tablesdonotcorrectlymodeltheincompleteinformationsettingforevaluatingtheepistemicstatusof com-plex Booleanformulae.Toovercomethelimitedexpressivenessoforthopairs whenmodelling incompleteinformation,one needs a moregeneralview of epistemicstates ascanbe provided intermsof{0,

1}-valuedpossibilitydistributions over interpretations[42,18].4. Non-truth-functionalframeworksforincompleteorvagueinformation

The aimofthissectionis todiscussformalsettings thatare slightlymoreexpressivethanKleene logicforaddressing theproblemofincompleteinformationintheclassicallogicsettingandthequestionofvagueness.Theysharethefeature ofdroppingthetruth-functionalityassumption,andturnouttobeformallyveryclose.

Wefirstexplainthelimitationoforthopairsintherepresentationofepistemicstates,viewingthemas

{0,

1}-valued pos-sibilitydistributionsoverthesetofclassicalinterpretations.Thenwerecall{0,

1}-valuedpossibilityandnecessitymeasures which wecompare toupperandlower Booleanvaluations.We showtheir closeconnection withmodalitiesinepistemic logic.Finally,weshowthatsupervaluations,usually appliedtothemodelling of vagueness,areformallyverycloseto pos-sibilitytheory.4.1. Thelimitedexpressivenessoforthopairsforincompleteinformation

In the following, a non-empty subset of Boolean valuations E

⊆ Ω

is calledan epistemicset. It represents an agent’s epistemic state, that is, a state of information according to which all that is known is that the real world is properly describedbyoneandonlyoneofthevaluationsinE.Thesets E(P,N)ofBooleanvaluationscompatiblewithapartialmodel(

P,

N)

arespecialcasesofepistemicsets.Wecanequivalentlyrepresentanepistemicset E byapossibilitydistribution[45]:

Definition4.1.ABooleanpossibilitydistributionisamapping

π

: Ω → {0,

1}suchthatπ

(

w)

=

1 forsome w∈ Ω.

Thepossibilitydistributionπ

E attachedto E issimplyitscharacteristicfunction:π

E(

w) =

½

1 if w∈

E (it means possible)0 otherwise (impossible) (4)

Then, thepossibilitydistribution

π

(P,N) of theepistemic set E(P,N) associatedwithan orthopair(

P,

N),

i.e. theset ofmodelsof

φ =

V

a∈Pa

∧

V

a∈N

¬

a,canbefactorised as:π

(P,N)(

w) =

min³

min a∈Pπ

a(

w),

mina∈N1−

π

a(

w)

´

(5)withconventionmin∅

=

0 andπ

a(

w) =

½

1 if w

²

a0 otherwise

TheepistemicsetE(P,N)isasetofBooleanvaluationsthattakestheformofaCartesianproductofsubsetsof

{

a,

¬

a},

a∈ A.

Table 3

Basicepistemicsetsrepresentablebyorthopairs.

3 Orthopairs Valuation pairs Subsets of Boolean valuations

0 (∅, A) 0E= (0,0) {w0} = [∧a∈A¬a]

1

2 (∅, ∅) (0,1) Ω

1 (A, ∅) 1E= (1,1) {w1} = [∧a∈Aa]

undef. undef. undef. ∅

areviewedashyper-rectanglesinthespace

Ω = {0,

1}niftherearen variables.Inthecaseofthespecialorthopair(

P,

Pc),

thepossibilitydistribution

π

(P,Pc)takesvalue 1 onlyforthevaluationcharacterised by P .Table 3showsbasicepistemicsetsthataremodelledbyorthopairs.Notethattheuseoforthopairshighlightsthe inter-pretationwithallpositiveliteralsandalsotheonewithallnegativeliterals,whichplaynospecificroleinthemoregeneral possibilitytheory setting. Moreover, there isno way of representing theempty set of interpretations (the contradiction) withorthopairsorconsistentvaluations.

Howeverwecangeneratearectangularupperapproximationofanynon-emptysubsetE

⊆ Ω

ofBooleaninterpretations bymeansofasinglepartialmodelRC(

E)

= (

PE,

NE)

asfollows:•

a∈

PE iffw(

a)

=

1,∀

w∈

E,•

a∈

NE iffw(

a)

=

0,∀

w∈

E.Themap E

7→ (

PE,

NE)

definesan equivalence relationon possibilitydistributions overΩ

and E(P,N)= ∪{

E: (

PE,

NE)

=

(

P,

N)}.

RC(

E)

can be called the rectangularclosure of E. Note that the rectangular closure of E may even lose all the informationcontainedinE.Forexample,ifE isadisjunctionofinterpretationshavingdifferentprojectionsoneachatomic space,suchasanydiagonalofthehyper-rectangleΩ,

thenRC(

E)

= Ω.

Ingeneral,anon-emptyepistemicset E

⊆ Ω

canberepresentedbyacollectionoforthopairs,whichcanbe viewedas adisjunctionofpartialmodels.Toseethis,consideraBooleanformulaφ

whosesetofmodelsisexactly E.Then, convertφ

todisjunctivenormalform(asadisjunctionofconjunctionsofliterals).Eachsuchconjunctioncanberepresentedbyan orthopair.Remark1.We canalways represent E by aset ofmutuallyexclusivesubsetsofinterpretations, each representingpartial models. This is because it is always possible to convert a disjunction of conjunctions into an equivalent disjunction of mutuallyexclusiveconjuncts,forinstanceusingspecificnormalforms(suchasbinarydecisiondiagrams[7]).

So,theuseofKleene logictohandleincompleteknowledgeissubject toseverelimitationsintermsofexpressiveness, since only a small subfamily of epistemic sets can be captured by orthopairs. Using orthopairs to representincomplete knowledgepresupposesthatinformationcanonlyhaveabearingonvariables,independentlyofeachother.Whileinlogical representations,variables aresupposed to belogically independent,theuseof orthopairscarries thisassumptionover to epistemicindependence(independence betweenpieces ofknowledgepertaining tovariables). Replacing possibility distri-butionsbyprobabilitydistributions,itissimilartoassumingstochasticindependencebetweenvariables(whichisastrong assumption).

4.2.Possibility–necessitypairs

Iftheavailable informationtakesthe formofan epistemic set E, we canattach toanypropositionits possibility and necessitydegrees

N (φ)

andΠ (φ)

[19].Definition4.2.Necessitymeasure

N

andpossibilitymeasureΠ

arerespectivelydefinedasΠ (φ) =

1 if and only if∃

w∈

E,

w|H φ

and 0 otherwise;

(6)N

(φ) =

1 if and only if∀

w∈

E,

w|H φ

and 0 otherwise.

(7)N (φ)

=

1 meansthatφ

iscertainlytrue,andΠ (φ)

=

1 thatφ

ispossiblytrue,inthecorrespondingepistemicstate.So,ifN (φ)

=

0 andΠ (φ)

=

1,itmeansthatthetruthofφ

isunknownintheepistemicstate[19].Theset-functionΠ (φ)

(resp.N

)isanextremecaseofnumericalpossibilitymeasure[45](resp.necessitymeasure[18]).Wecancomputethepair

(N ,

Π )

offunctionsL

→ {0,

1}inducedbytheepistemicsetrepresentinganorthopair(

P,

N)

asfollows:• N (φ)

=

1 ifV

a∈Pa∧

V

a∈N¬

a|H φ

and0otherwise.• Π (φ)

=

1 ifV

a∈Pa∧

V

There isan obvioussimilaritybetweenconsistentBVPsextendedtothewhole languageandnecessity–possibilitypairs

(N ,

Π ),

namelythefollowingidentitieshold:N

(¬φ) =

1− Π (φ)

andΠ (¬φ) =

1−

N

(φ)

(8)N

(θ ∧

ϕ) =

min¡

N

(θ ),

N

(ϕ)

¢

(9)Π (θ ∨

ϕ) =

max¡Π(θ), Π(ϕ)

¢

(10)Howeverthereisadifferencebetweenthem:whilev

(θ ∨

ϕ

)

=

max(v(θ ),

v(

ϕ

))

andv(θ ∧

ϕ

)

=

min(v(θ ),

v(

ϕ

)),

ingeneral, itonlyholdsthatN

(θ ∨

ϕ) ≥

max¡

N

(θ ),

N

(ϕ)

¢

and

Π (θ ∧

ϕ) ≤

min¡Π(θ), Π(ϕ)

¢

Inparticular,

Π (θ ∧ ¬θ )

=

0 (non-contradictionlaw)andN (θ ∨ ¬θ)

=

1 (excludedmiddlelaw),thusescapingtheanomaly oflosingtheBooleantautologieswheninformationisincompleteandpropositionsareBoolean.Duetotheseproperties,it isclearthat:Proposition4.1.IftheepistemicsetisapartialmodelencodedbytheconsistentBVP

(

v,

v)

theassociatedpossibility–necessitypairs arerecoveredasΠ (φ) =

maxv≤w≤vw

(φ)

N

(φ) =

minv≤w≤vw

(φ)

Proof. v

≤

w≤

v is equivalenttosaying that w is acompletion of thepartial model(

P,

N)

encodedby(

v,

v),

i.e. w∈

E(P,Q).✷

It is easy to identify logical expressions

φ

forwhich extended consistent BVP’s(

v,

v)

and possibility–necessitypairs(Π,

N)

differ.Example4.1. a

⊔

b anda⊔ (

a′⊓

b)

are not equivalentpropositionsunder extendedconsistent BVP’s.Indeed,consider the orthopair(

P,

N)

= ({

b},

∅).

Since v(

b)

=

v(

b)

=

1,it isobviousthat v(

a⊔

b)

=

v(

a⊔

b)

=

1 too.Fortheother formula,we canproceedasfollows:•

v(

a)

=

1 and v(

a)

=

0 sincea∈

/

P∪

N;•

v(

a′)

=

1 andv(

a′)

=

0 likewise;•

v(

a′⊓

b)

=

min(v(

a′),

v(

b))

=

1;•

v(

a′⊓

b)

=

min(v(

a′),

v(

b))

=

0;•

So v(

a⊔ (

a′⊓

b))

=

max(v(

a),

v(

a′⊓

b))

=

1;•

So v(

a⊔ (

a′⊓

b))

=

max(v(

a),

v(

a′⊓

b))

=

0.Note that this result is more easily checked with Kleene truth-tables, since, with

τ

(

a)

=

12

,

τ

(

b)

=

1,τ

(

a⊔

b)

=

max(12

,

1) =1,whileτ

(

a⊔ (

a′⊓

b))

=

max(12,

min(12,

1))=

12.However,intheBooleansettingthetwo formulasa∨

b and a∨ (¬

a∧

b)

havethesamesetofmodels,soN (

a∨

b)

= N (

a∨ (¬

a∧

b)),

andΠ (

a∨

b)

= Π (

a∨ (¬

a∧

b)).

Moregenerally,givenatautologicalBooleanformula

φ,

thereexistsaconsistentBVP(

v,

v)

suchthatv(φ)

=

1,v(φ)

=

0, corresponding to the third truth-value 12.In contrast, forany possibility–necessity pair,it holds thatN (φ)

= Π (φ)

=

1. Conversely, givenaninconsistentBoolean formulaφ,

thereexistsa consistentBVP(

v,

v)

such that v(φ)

=

1, v(φ)

=

0.In contrast, foranypossibility–necessity pair, it holds thatN (φ)

= Π (φ)

=

0.This indicates that possibility–necessity pairs representincompleteinformationmorefaithfullythanBVPs.Sothereisnoequalitybetweenv andΠ,

norbetweenv andN

.However, a consistent BVP(

v,

v)

determines a unique possibility–necessitypair:the former determines an orthopair(

P,

N)

andtheresultingpossibility–necessitypair(Π,

N )

istheonethatisinducedbytherectangularepistemicsetE(P,N).4.3. Possibilitytheoryandepistemiclogic

In fact, necessity–possibility pairs

(N ,

Π ),

as witnessed by their characteristic axioms (8), are also pairs of dual KD modalities,andassuchitislegitimatetoconnect themtoepistemiclogic[27].Thisconnectionismadeundertheformofasimplifiedepistemic logiccalledMEL[2,3].Itisbased onafragment oftheKDlanguage, withnonestingofmodalities andnoobjective(modality-free)formulas.Inotherwords,itisahigher-orderstandardpropositionallanguagewithatomic formulasoftheform

✷

α

,whereα

isanypropositionalformulaofanunderlyingstandardpropositionallanguage.Itsaxioms arethe usual K,D,anda necessitation axiomforpropositional tautologies,ontop ofpropositional axiomsforthemodal formulas.Eventhough onemayconsiderMEL asa genuinespecialcaseofKDorS5,thereare differenceswiththeusual epistemiclogicsuchasS5:•

It cannot distinguish belief from knowledge (true belief) since axiom T(✷α

→

α

) cannot be expressed in the MEL language.•

MELdoesnotdealwithintrospection:itaccountsforpartialknowledgeoftheepistemicstateofanexternalagent(e.g. theperceptionofwhatacomputerknowsorbelieves).Howeverthepresentpaperisnotconcernedwithintrospection either.•

ItssemanticsisintermsofepistemicsetsE6= ∅,

notintermsofaccessibilityrelations(infactMELisjustapropositional logic,adoptingthelanguageofepistemiclogic).NamelyamodalformulainMELisevaluatedonepistemicsets,noton possibleworlds.In[10],wehaveshownthatKleenelogic(andotherthree-valuedlogicsofunknown)canbeencodedinMEL.Wethenhave torestricttheMELlanguagetoatomicformulasoftheform

✷

ℓ

whereℓ

isaBooleanliteral.Thetranslationofτ

(

a)

=

1 is✷

a,2thetranslationofτ

(

a)

=

0 is✷¬

a andthusthetranslationofτ

(

a)

=

12 is

♦

a∧ ♦¬

a.ItfirstexplainswhytherearenotautologiesinKleenelogicforincompleteinformation.Indeed,

✷

a∨ ✷¬

a isclearlynotatautology inthemodallogicKD whilea∨ ¬

a isatautologyinpropositionallogic.It alsoclearly highlights the limitedexpressive powerof three-valued logics, namelya disjunction of literalssuch as a

⊔ ¬

b inKleenelogic(Kleeneimplication)correspondsto✷

a∨ ✷¬

b inMEL,while✷

(

a∨ ¬

b)

hasnocounterpartinKleene logic. In other words, the sub-logic of MEL accounting for three-valued logics of unknown uses a language where only literalsare prefixedbymodalities,andthesemanticaccount canberestrictedtorectangularepistemicsetscorresponding tothree-valuedvaluations,orequivalently,toorthopairs(

P,

N).

Remark2.Atwo-valuedtruth-functionalmodalityreducestoastandardBooleanvaluation[19],while,inthethree-valued propositional setting accommodating borderline cases, such deviant modalities (where the lower necessity-likevaluation distributesover disjunctions)arenot trivial. MoregeneralKleene algebras displayingsuch deviant modalitiesare studied in[8].

4.4.Supervaluationsandpossibilitytheory

Supervaluationism,proposed by Fine[22],3 isan alternative modelofborderline casesasyielding truth-gapsbetween clearlytrueandclearlyfalse.Inthisapproachthefundamentalideaisthatvariablestakingborderlinevaluescanbe indif-ferentlyassignedanyoftheclearcutvalues.SuchcompletionscorrespondtoasetofadmissibleBooleanvaluations.

Definition4.3.Asentenceissupertrue ifitistrueineveryadmissiblevaluationandsuperfalse ifitisfalseineveryadmissible valuation.

Accordingly, a sentenceis borderline,if itis neither supertrueor superfalse or,in other words, ifthere are some ad-missible valuations for which the sentence is true andother ones for which it is false. Unlike three-valued logics, the supervaluationistapproachisnon-compositional anditalsopreservesBooleanlogicalequivalences,tautologiesand contra-dictions.4 Forexample,evenifpropositionalvariablea anditsnegation

¬

a arebothborderline,nonetheless,thesentences a∨ ¬

a anda∧ ¬

a arealwayssupertrueandsuperfalserespectively.ThisisincontrasttothesamescenarioinKleenelogic wherebothsentenceswouldbeallocatedaborderlinetruth-value.ThisexampleisaparticularcaseofwhatFine[22]refers toaspenumbralconnections ascorrespondingtologicalrelationsholdingbetweenborderline sentences.Forinstance,given asetofborderlineliterals,penumbral connectionsmayresultincertain logicalcombinationsoftheseliteralsbeingeither clearlytrueorclearlyfalse. Ingeneral, itsadvocates arguethat thesupervaluationistapproachisbetter abletorepresent penumbralconnectionsthanthree-valuedlogics.2 Inotherwords,τ(a)=1 iffw(a)=1 iscertainlytrue.

3 Infactthetermsupervaluation wasoriginallyintroducedbyvanFraassen[39]withregardtothesituationinpredicatelogicwhensometermsofthe

languagedonothavereferentsinaparticularinterpretation.

4 Ifsentencesθ,φ ∈ LareclassicallyequivalentinthesensethatforallBooleanvaluationsw∈ Ω,w(θ )=w(φ),thenθissupertrue (superfalse)ifand

onlyifφissupertrue (superfalse).Similarly,ifφisatautologyinthesensethatforeveryBooleanvaluationw∈ Ω,w(φ)=1 thenφissupertrue.Finally, supervaluationisttruthmodelsarenotcompositionalsince,ingeneral,knowingthetruthvalueofθandofφisnotsufficienttodeterminethetruthvalue ofθ ∧ φorθ ∨ φ.

Example4.2.ConsiderthefollowingtypeofpenumbralconnectionsrelatedtothevaguepredicateTall ofTable 2.Suppose wehaveanincreasingsequenceofheightsh1

<

h2< . . . <

hnwhereh1isclassedasbeingclearlynottall,whilsthnisclearlytall.Allotherheightsaretakentobeborderlinecasesoftall.However, despitetheir borderlineclassificationifwewere to learnthatheighthiwasindeedconsideredtall wewouldimmediatelyinferthathjshouldbealsoconsideredtall for j

≥

i.Nowdefiningpropositionalvariablessuchthataidenotesthestatement‘apersonofheighthi istall’fori

=

1,. . . ,

n,thensuchpenumbralconnectionscanbecapturedbytheepistemicset E

= {

w2,

. . . ,

wn}

where wi(

aj)

=

1 ifandonlyif j≥

i.In thesettingof propositionallogic, a naturalformalisationofsupervaluationism isinterms of(non-truth-functional) loweranduppertruthvaluationsasrecentlyproposedbyLawryandTang[33].InthisapproachasetofadmissibleBoolean valuationsisidentified,andthenforanysentence

φ ∈ L,

thelowervaluation ofφ

is1 ifandonlyifφ

istrueineach of theadmissiblevaluationsi.e.φ

issupertrue.Similarly,theuppervaluation ofφ

is1 if andonlyifφ

istrueinatleastone admissiblevaluation,i.e.,φ

isnotsuperfalse.Definition4.4.LetE

⊆ Ω

denotethesetofadmissiblevaluationsforL

.Thenwedefineloweranduppervaluationsv: L

→

{0,

1}andv: L

→ {0,

1},referredtoasasupervaluationpair[33],suchthat∀φ ∈ L;

v

(φ) =

min©

w

(φ) :

w∈

Eª

and v

(φ) =

max©

w

(φ) :

w∈

Eª

Here v

(φ)

=

1 meansthatφ

issupertrue andv(φ)

=

0 meansthatφ

issuperfalse.ThisformalisationismathematicallyidenticaltotheBooleanpossibility–necessitypairsdescribedinSubsection4.2.More specifically,

Proposition4.2.LetE

⊆ Ω

bethesetofadmissiblevaluationsofthelanguageL

.Considerthenecessityandpossibilitymeasures definedinEqs.(6)and(7).Thenφ

issupertrueifandonlyifN (φ)

=

1 andsuperfalseifandonlyifΠ (φ)

=

0.Theproofofthispropositionisstraightforward(seealso[14]).So,theLawryandTangsupervaluationistlowerandupper valuationsinthesupervaluationframeworkthenrespectivelycorrespondtonecessityandpossibilitymeasures.

Despite thisformal identity between supervaluationsand Boolean possibility–necessitypairs there is none-the-less a subtle interpretationaldifference between thetwo models. Interestingly,this difference isinherently linked to the inter-pretationoftheintermediatevalue.Thenotionsofconjunctiveanddisjunctivesets[41,20]arefundamentaltounderstanding thesetwodistinctsemantics.Aconjunctivesetisaconjunctionofelementsrepresentingthevalueofaset-valuedproperty, whereasadisjunctivesetisacollectionofmutuallyexclusiveelements,eachrepresentingoneofanumberofpossibilities, onlyoneofwhichcanactuallyberealised.Forexample,thesetofpeoplewhohaveboughtalotteryticketisaconjunctive set,whilst the setofpeople whomaypossibly havethewinninglottery ticketisa disjunctiveset.From thisperspective thenthesupervaluationistsetofadmissiblevaluationsisaconjunctivesetofBooleanvaluationsinthesensethateach pre-cisificationofthegiventruth-modelisonaparwithanotherwhilst forBooleanpossibility–necessitypairstheunderlying epistemic setisa disjunctivesetofpossibleBoolean valuationsonlyoneofwhichcaptures theactualprecisification.The latterdisjunctiveviewisclosertotheepistemicapproachtovagueness,advocatedbyWilliamson[40].Theconjunctiveview canactuallyinturnbeinterpretedintwoways:supervaluationistsconsiderthatnoneoftheprecisificationsisappropriate, whileplurivaluationists(likeSmith[37])considerallprecisificationsareequallygood.

4.5. Boundedepistemicsets

Many ofthe theoretical results concerningsupervaluationism can be easily translated fromLawryand Tang[33] into possibilitytheory.Thistranslationhighlights therelationship betweenBoolean possibilitytheoryandKleene three-valued logicofborderline.Suchrelationshipsarebestformulatedwithinthecontextofaparticularrestrictedclassofepistemicsets definedasfollows:

Definition4.5. An epistemic set E

⊆ Ω

is said to be bounded iff{

wE,

wE}

⊆

E, where wE(

a)

=

min{w(

a)

:

w∈

E}

andwE

(

a)

=

max{w(

a)

:

w∈

E},

foralla∈ A.

NoticethatanepistemicsetE(P,N)inducedbyanorthopair

(

P,

N)

isaspecialcaseofaboundedepistemicsetinwhichwE

=

v(P,N)andwE=

v(P,N),theconsistentBVP(

v(P,N),

v(P,N))

inducedby(

P,

N).

Infactwecanviewsuchstatesasbeingboundedandcomplete since E(P,N)

= {

w∈ Ω :

v(P,N)≤

w≤

v(P,N)).

There are,however,manycasesofboundedepistemicsetswhichcannotbegeneratedinthisway.

Example4.3. A simple example ofa bounded epistemic set is E

= [(

a∧

b)

∨ (¬

a∧ ¬

b)],

where wE(

c)

=

0,∀

c∈ A,

and wE(

c)

=

1,∀

c∈ A.

However,E′= [(¬

a∧

b)

∨ (

a∧ ¬

b)]

(exclusiveor)isnotbounded.Example4.4. Consideringagainthe penumbral connection of Example 4.2, E is a bounded epistemic set with wE

=

wnandwE

=

w2 sothatthecorrespondingorthopairis(

P,

N)

= ({

an},

{

a1}).

However,theassociatedepistemicset E({an},{a1})includesvaluationsw forwhichw

(

ai∧ ¬

aj)

=

1 where j>

i,andhenceE⊂

E({an},{a1}).Definition4.6.Anentirelypositive (resp.entirelynegative)sentenceisasentencegeneratedrecursivelyfromthepropositional variables(resp.thenegatedpropositionalvariables)usingonly

∧

and∨.

Thesetofentirelypositive(resp.entirelynegative) sentencesisdenotedbyL

+(resp.L

−).Example4.5.Theformulasa1

∧ (

a2∨

a3)

∈ L

+ and¬

a1∧ (¬

a2∨ ¬

a3)

∈ L

−.Let

Π

E andN

E denote the Boolean possibility and necessitymeasures representing an epistemic set E as given byEqs.(7)and(6).WerecallthefollowingresultsfromLawryandTang[33],inthelanguageofpossibilitytheory:

Proposition4.3.LetE beaboundedepistemicsetandletE′

= {

wE,

wE}

then∀θ ∈ L

+∪ L

−,N

E(θ )

= N

E′(θ )

andΠ

E(θ )

= Π

E′(θ )

.Proposition 4.3showsthat fora boundedepistemic set E and forentirelypositiveor entirelynegativesentences,the necessityandpossibilityvaluesaredependentonlyontheboundingBooleanassignments wE andwE.

Proposition4.4.LetE beaboundedepistemicsetthen

∀θ,

ϕ

∈ L

+and∀θ,

ϕ

∈ L

−itholdsthat:N

E(θ ∨

ϕ) =

max¡

N

E(θ ),

N

E(ϕ)

¢

and

Π

E(θ ∧

ϕ) =

min¡Π

E(θ ), Π

E(ϕ)

¢

Thisresultshowsthat possibility–necessitypairsrepresentingboundedepistemic setsarestronglycompositionalwhen restricted eitherto entirely positive or entirelynegative sentences. Indeed forthis fragment of the logic they share the same conjunctionanddisjunction rules as lower andupper Boolean valuationsencoding Kleene truth-values. Infact, as thefollowing resultshows, possibility–necessitypairsrepresenting boundedepistemic setsare particularlyrelatedto the consistentBVPgeneratedbytheorthopair

(

P,

N)

whereP= {

a:

wE(

a)

=

1}andN= {

a:

wE(

a)

=

0}.Proposition4.5.IfE isaboundedepistemicset,thenthereisauniqueextendedconsistentBVP

E

v= (

v,

v)

suchthat∀θ ∈ L

+∪ L

−,N

E(θ )

=

v(θ )

andΠ

E(θ )

=

v(θ )

,andingeneral∀θ ∈ L

,v(θ )

≤ N

E(θ )

≤ Π

E(θ )

≤

v(θ )

.Furthermore,E

v= E

v(P,N)whereP= {

a:

wE

(

a)

=

1}andN= {

a:

wE(

a)

=

0}oralternativelyE

v= E

vRC(E).Hence,inan epistemic/partialknowledge settinginvolvingboundedepistemic sets,we maythink ofKleenevaluations (intheformextendedconsistentBVP’s)asagenerallymoreimpreciseapproximationoftheunderlyingpossibility–necessity pair(seealso[12]),whichonlyagreeswiththepossibilisticmodelwhenrestrictedtoentirelypositiveorentirelynegative sentences.Fromthealternativeperspectiveoftruth-gapsorborderlinecasesinducedbyinherentlyvaguepropositions,the above propositionindicates that Kleene valuations can always be viewed asa semantic weakening ofa stronglyrelated supervaluationisttruth-model.

5. Representationsforconflictinginformation

Inordertoextendtheexpressivepoweroforthopairsofsetsofvariables,wemaywishtorelaxtheconditionP

∩

N= ∅.

The epistemic understanding ofthis license isthat ifa∈

P∩

N, it means that there are reasons tobelieve thetruth of a and also reasons to believe a tobe false. For instance,there maybe agentsclaiming the truth of a and other agents claiming its falsity. This approach is akin to the semantics of some paraconsistent logics such as Belnap’s [4]. Dubois, KoniecznyandPrade[16]usedsuchparaconsistentpairsofsetsofvariablesforthestudyofapossibilisticlogiccounterpart ofquasi-classicallogicofBesnardandHunter[5].5.1. ParaconsistentvaluationsandBelnaptruth-values

We call such pairs of subsetsof variables

(

F,

G)

∈

2A×

2A with F∩

G6= ∅

paraconsistent. Forthese pairs, it is clearthat E(F,G)

= ∅.

Anothersemantics isnecessaryforthem.We usea set4= {0,

1,u,

b}

oftruth-values,whereu standsforunknown (itcorrespondsto1/2 inKleenelogic)andb standsforcontradictory (bothtrueandfalse).Afour-valuedvaluation isamapping

A

→

4 denotedbyσ

.Apair(

F,

G)

intheparaconsistentcaseiscloselyrelatedtoBelnap[4]4-valuedlogic, namely,inhisterminology:•

Ifa∈

F\

G thenσ

(

a)

=

1:a isassertedbutnotnegated(Belnaptruth-valueTRUE).•

Ifa∈

G\

F thenσ

(

a)

=

0:a isnegatedbutnotasserted(Belnaptruth-valueFALSE).•

Ifa∈

F∩

G thenσ

(

a)

=

b:a isbothnegatedandasserted(Belnaptruth-valueBOTH).•

Ifa∈

/

F∪

G thenσ

(

a)

=

u:a isneithernegatednorasserted(Belnaptruth-valueNONE).Table 4

Belnapdisjunctionandconjunction.

⊔ 0 u b 1 0 0 u b 1 u u u 1 1 b b 1 b 1 1 1 1 1 1 ⊓ 0 u b 1 0 0 0 0 0 u 0 u 0 u b 0 0 b b 1 0 u b 1 τ∈4A (v,v) (F,G)

Fig. 2. Equivalences for paraconsistent information representation.

Table 5

Basicepistemicsetsrepresentablebygeneralvaluationpairs.

3 Generalised pairs Valuation pairs Subsets of Boolean valuations

0 (∅, A) 0E= (0,0) {w0} = [∧a∈A¬a]

u (∅, ∅) (0,1) Ω

1 (A, ∅) 1E= (1,1) {w1} = [∧a∈Aa]

b (A, A) (1,0) ∅

The epistemic truthset 4 isequippedwitha bi-latticestructure[24],namelythere isthetruth-ordering

<

such that 0<

u<

1 and0<

b<

1;andtheinformationordering(rangingfromnoinformation(u)totoomuchinformation(b))such that u<

1<

b and u<

0<

b. The truth-tablesare those ofKleene logic for{0,

u,

1} and{0,

b,

1} according to thetruth ordering, plus u⊔

b=

1,u⊓

b=

0 (seeTable 4). Thesecond borderline truth-valueb playsthesame role asthe firstone withrespectto1and0.Four-valuedvaluationscanbecapturedbygeneralBooleanvaluationpairs.Thecasewherev

£

v exactlycorrespondsto pairs(

F,

G)

ofsetsofvariablessuchthat F∩

G6= ∅,

letting F= {

a∈ A

:

v(

a)

=

1}andG= {

a∈ A

:

v(

a)

=

0}.Wecallsuch pairs(

v,

v)

paraconsistent BVP’s.LawryandGonzález-Rodríguez[32]haveshownthattruth-tablescorresponding totheinductivedefinitions(1),(2),(3) ofconsistentBVP’soverthelanguagebecomeBelnap4-valuedtruth-tableswhentheseinductivedefinitionsareappliedto allBVP’s

(

v,

v)

withouttherestrictionv≥

v.Inparticular,b correspondstothepair(1,

0),and•

b⊓

u correspondstothecomponentwiseBooleanconjunctionof(0,

1)and(1,

0),whichis(0,

0),i.e.,0.•

b⊔

u correspondstothecomponentwiseBooleandisjunctionof(0,

1)and(1,

0),whichis(1,

1),i.e.,1.InthiscasethediagramofFig. 1shouldbeupdated asonFig. 2.Table 5completesTable 3,accountingfornon-consistent valuationpairs.

JustasforKleenelogic,thetruth-functionalityofBelnapapproachdoesnotsoundverynaturalinthescopeofhandling paraconsistentBooleanformulasotherthanliterals[13].

5.2. Paraconsistentorthopairsaspairsofconsistentorthopairs

Inordertointerprethis4truth-values,Belnapproposestoconsiderseveralconflictingbutinternallyconsistentsources ofinformationaboutvariables.Infacttwosourcesofinformationareenoughtogeneratethefourtruthvalues,eachsource correspondingtoapartialmodel.Itisthennaturaltotrytorepresentparaconsistentorthopairsbymeansoftwostandard consistent orthopairs of the form

(

F,

G\

F)

and(

F\

G,

G)

that conflict with each other. These are pairs of orthopairs(

P1,

N1),

(

P2,

N2),

corresponding to the epistemic states of two conflicting agents, with P2⊆

P1,

N1⊆

N2,

N1∩

P2=

∅,

P1∪

N1=

P2∪

N2. The corresponding paraconsistent pairis ofthe form(

F,

G)

= (

P1,

N2).

It corresponds to twodis-jointepistemicsets Ei

=

E(Pi,Ni),

i=

1,2.More generally we could reconstruct a paraconsistent pair from any two orthopairs