POWER RELATIONS AND GOOD GOVERNANCE: A SOCIAL

NETWORK ANALYSIS OF THE EVOLUTION OF THE

INTEGRITY IN PUBLIC OFFICE ACT IN THE

COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA

Thèse

Gérard JEAN-JACQUES

Doctorat en science politique

Philosophiae doctor (Ph.D)

POWER RELATIONS AND GOOD GOVERNANCE: A SOCIAL

NETWORK ANALYSIS OF THE EVOLUTION OF THE

INTEGRITY IN PUBLIC OFFICE ACT IN THE

COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA

Thèse

Gérard JEAN-JACQUES

Sous la direction de:

Louis IMBEAU, directeur de recherche Mathieu OUIMET, codirecteur de recherche

RÉSUMÉ:

La Banque mondiale propose la bonne gouvernance comme la stratégie visant à corriger les maux de la mauvaise gouvernance et de faciliter le développement dans les pays en développement (Carayannis, Pirzadeh, Popescu & 2012; & Hilyard Wilks 1998; Leftwich 1993; Banque mondiale, 1989). Dans cette perspective, la réforme institutionnelle et une arène de la politique publique plus inclusive sont deux stratégies critiques qui visent à établir la bonne gouvernance, selon la Banque et d'autres institutions de Bretton Woods. Le problème, c’est que beaucoup de ces pays en voie de développement ne possèdent pas l'architecture institutionnelle préalable à ces nouvelles mesures. Cette thèse étudie et explique comment un état en voie de développement, le Commonwealth de la Dominique, s’est lancé dans un projet de loi visant l'intégrité dans la fonction publique. Cette loi, la Loi sur l'intégrité dans la fonction publique (IPO) a été adoptée en 2003 et mis en œuvre en 2008.Cette thèse analyse les relations de pouvoir entre les acteurs dominants autour de évolution de la loi et donc, elle emploie une combinaison de technique de l'analyse des réseaux sociaux et de la recherche qualitative pour répondre à la question principale: Pourquoi l'État a-t-il développé et mis en œuvre la conception actuelle de la IPO (2003)? Cette question est d'autant plus significative quand nous considérons que contrairement à la recherche existante sur le sujet, l'IPO dominiquaise diverge considérablement dans la structure du l'IPO type idéal. Nous affirmons que les acteurs "rationnels," conscients de leur position structurelle dans un réseau d'acteurs, ont utilisé leurs ressources de pouvoir pour façonner l'institution afin qu'elle serve leurs intérêts et ceux et leurs alliés. De plus, nous émettons l'hypothèse que: d'abord, le choix d'une agence spécialisée contre la corruption et la conception ultérieure de cette institution reflètent les préférences des acteurs dominants qui ont participé à la création de ladite institution et la seconde, notre hypothèse rivale, les caractéristiques des modèles alternatifs d'institutions de l'intégrité publique sont celles des acteurs non dominants.

Nos résultats sont mitigés. Le jeu de pouvoir a été limité à un petit groupe d’acteurs dominants qui ont cherché à utiliser la création de la loi pour assurer leur légitimité et la survie politique. Sans surprise, aucun acteur n’a avancé un modèle alternatif. Nous avons conclu donc que la loi est la conséquence d’un jeu de pouvoir partisan.

Cette recherche répond à la pénurie de recherche sur la conception des institutions de l'intégrité publique, qui semblent privilégier en grande partie un biais organisationnel et structurel. De plus, en étudiant le sujet du point de vue des relations de pouvoir (le pouvoir, lui-même, vu sous l’angle actanciel et structurel), la thèse apporte de la rigueur conceptuelle, méthodologique, et analytique au discours sur la création de ces institutions par l’étude de leur genèse des perspectives tant actancielles que structurelles. En outre, les résultats renforcent notre

capacité de prédire quand et avec quelle intensité un acteur déploierait ses ressources de pouvoir.

ABSTRACT: The World Bank proposes good governance as the strategy

to correcting the evils of bad governance and to facilitate development in developing states (Carayannis, Pirzadeh, & Popescu 2012; Hilyard & Wilks 1998; Leftwich 1993; World Bank 1989). From this perspective, institutional reform and a more inclusive public policy arena are two critical strategies that will likely lead to good governance, according to the Bank and other Bretton Woods institutions. The problem is that many of these states do not have the pre-requisite institutional architecture to accommodate such measures. This thesis studies and discusses how one developing state, the Commonwealth of Dominica, approached the development of an institution to oversee integrity in public office. This Act, the Integrity in Public Office Act (IPO) was passed in 2003 and implemented in 2008.

The focus in the thesis is on power relations among dominant actors surrounding the IPO consequently, it employs a combination of social network analysis and qualitative research techniques to answer the principal question: Why did the state develop and implement the current design of the IPO (2003)? This question is all the more significant when we consider that contrary to existing research on the subject, the Dominican IPO diverges considerably in structure from the ideal-type IPO. We argue that “rational” actors, cognizant of their structural position in a network of actors, have used their power resources to shape the institution so that it serves them and their allies. We hypothesized that: First, the choice of a specialised anti-corruption agency and the subsequent design of that agency reflect the preferences of the dominant actors who were involved in the creation of the IPO and second, our rival hypothesis, the characteristics of alternative options and models of public integrity institutions are those of the non-dominant actors.

Our results are mixed. Power play was limited among a small group of dominant actors who sought to use the creation of the Act as an opportunity for political legitimacy and survival. Not surprisingly, there was no alternative model advanced. We concluded therefore that the Act resulted from a purely partisan agenda.

This research responds to the paucity of studies on the design of institutions of public integrity, which largely seem to have an organisational and structural bias. In addition, by embracing the topic from the perspective of power relations, the thesis adds conceptual, methodological, and analytical rigour to discourses on the creation of such institutions by studying their evolution from both agential and structural perspectives. Finally, the results offer us an opportunity to predict when and in what intensity actors will deploy their power resources.

TABLE OF CONTENTS RÉSUMÉ ... III ABSTRACT ... v TABLE OF CONTENTS ... VI LIST OF TABLES ... IX LIST OF FIGURES ... X REMERCIEMENTS ... XI INTRODUCTION ... 1

The Commonwealth of Dominica ... 6

Integrity in Public Office Act (2003) ... 9

Structure of the IPO ... 12

Purpose, Research Question, and Thesis Statement ... 14

Justification for the Research ... 15

Summary ... 17

Structure of the Thesis ... 18

Summary of the Introduction ... 19

CHAPTER 1: CONCEPTUALISATION ... 20

1.1 Public Integrity ... 20

1.2 Institutions: Choice and Design ... 23

1.3 Purpose of Integrity Bodies... 24

1.4 Typology of IPOs ... 26

1.5 Ideal-Type ... 30

1.6 Summary to Chapter 1 ... 32

CHAPTER 2: EXPLAINING CHOICE: THEORIZING ABOUT CREATING THE IPO ... 33

2.1 Theorizing about Integrity Management ... 39

2.2 Structure – Agency ... 40

2.3 Power ... 42

2.4 Theories of Power in Networks of Actors ... 44

2.5 Strong and Weak Ties ... 44

2.6 Centrality ... 45

2.7 Typology of Power Resources ... 48

2.8 Summary of Our Theory: Power and Integrity Management ... 50

2.9 Summary of Chapter 2 ... 52

CHAPTER 3: METHOD ... 55

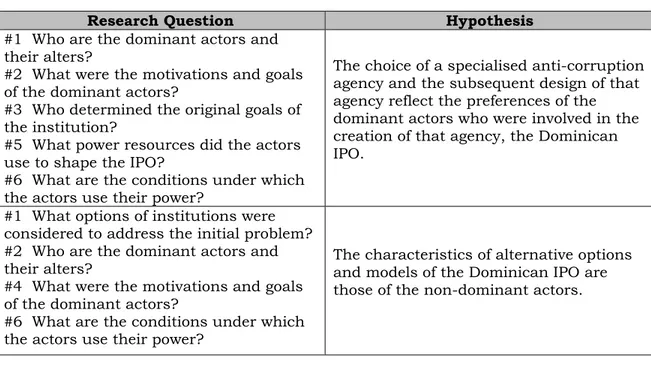

3.1 Research Questions and Key Concepts ... 56

3.2 Hypotheses ... 57

3.2.1 Hypothesis #1: Theoretical Foundations ... 58

3.2.2 Hypothesis #2: Theoretical Foundations ... 61

3.3 Data Collection and Analysis ... 63

3.4 Data Sources ... 64

3.5 Data Collection ... 64

3.6 Document Search ... 64

3.9 Summary of Document Analysis ... 69

3.10 Interaction with Participants ... 69

3.13 Semi-Structured Interviews ... 75

3.14 Validating Data ... 76

3.15 Jaccard Similarity Coefficient ... 77

3.16 Questionnaires ... 77

3.17 Triangulation of Sources ... 78

3.18 Analysing Power Relations ... 78

3.18.1 UCINET ... 79

3.18.2 Connections among Actors ... 82

3.18.3 Actor Centrality ... 82

3.19 Summary of Chapter 3 ... 84

3.20 Anticipated Conclusions... 85

CHAPTER 4: THE RESULTS ... 87

4.1 Overview ... 88

4.1.1 Key Concepts ... 88

4.1.2 Pre and Post Phases ... 88

4.2 Results for question #1 ... 90

4.2.1 Egonets ... 94

4.2.2 Degree Centrality Scores ... 109

4.3 Results for question #2 ... 110

4.4 Results for question #3 ... 114

4.5 Results for question # 4 ... 116

4.6 Results for question # 5 ... 120

4.6.1 Results for sub-questions #1 and #1.1 ... 122

4.6.2 Results for sub-question #2 ... 124

4.6.3 Results for sub-question #3 ... 126

4.7 Results for question #6 ... 131

4.7.1 Urgency ... 135

4.7.2 Structurally ... 137

4.7.3 Composition of the Coalitions/Pre and Post-Transitions ... 137

4.8 Summary to Chapter 4 ... 138

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION ... 140

5.1 Review ... 140

5.2 The Anatomy of a Centralised IPO ... 143

5.3 Part I: Institutional Divergence ... 147

5.3.1 A Multi-Purpose Tool ... 147

5.3.2 Clanification and the Bear Syndrome ... 149

5.3.3 Talk, and More Talk ... 154

5.3.4 Political Survival ... 155 5.3.5 Defensive Democratization ... 156 5.3.6 Fluctuating Investments ... 159 5.3.7 International Pressure ... 160 5.3.8 Unexpected Findings ... 161 5.3.9 Summary ... 162

5.4 PART II: Explaining the Choice of the Dominican Model ... 163

5.4.1 Isomorphism ... 164

5.5 Part III: Validating Hypotheses ... 167

5.6 Summary to Chapter 5 ... 171

CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSIONS ... 173

6.1 Review ... 173

6.2.2 Dobel Triangle, Policy Networks, and Public Integrity ... 178

6.2.3 Reconceptualisation of Public Integrity and Political Transparency ... 179

6.2.4 Conflict Zone ... 181

6.2.5 Summary ... 183

6.3 Challenges ... 183

6.4 Areas for Further Study ... 184

6.4.1 Measuring Power... 184

6.4.2 Democracy and Public Integrity: The Conundrum ... 185

6.4.3 The Centralised Model Vs the Ideal Type ... 186

6.5 Concluding Comments ... 187

REFERENCES ... 188

APPENDICES ... 200

Appendix 1: Example of Matrix used for Analysing Documents ... 200

Appendix 2: List of all Actors ... 205

Appendix 3: Matrices Showing UCINET Ties Among Actors ... 207

Appendix 3.1: Pre-Transition Ties ... 207

Appendix 3.2: Post-Transition Ties ... 209

Appendix 4: Questionnaire and Interview Schedule Intended for used in the Data Collection ... 211

Appendix 4.1: Questionnaire on the Creation of the Dominica Integrity in Public Office Act (2003) ... 211

Appendix 4.2: Interview Guide ... 221

APPENDIX 5: Egonets in the Pre and Post-Transition Phases ... 227

Appendix 5.1: Adjacent Matrices Showing Egonet for Top Five Egos and Ties among Alters in Pre-Transition ... 227

Appendix 5.2: Adjacent Matrices Showing Egonet for Top Five Egos and Ties among Alters in Post-Transition ... 229

Appendix 5.3: Egonet for PRI1 and Ties among Alters in Pre-Transition ... 231

Appendix 5.4: Egonet for PRI1 and Ties among Alters in Post-Transition ... 231

Appendix 5.5: Egonet for PU1 and Ties among Alters in Pre-Transition ... 232

Appendix 5.6: Egonet for PU1 and Ties among Alters in Post-Transition ... 233

Appendix 5.7: Egonet for PRI2 and Ties among Alters in Pre-Transition ... 234

Appendix 5.8: Egonet for PRI2 and Ties among Alters in Post-Transition ... 234

Appendix 5.9: Egonet for PU2 and Ties among Alters in Pre-Transition ... 235

Appendix 5.10: Egonet for PU2 and Ties among Alters in Post-Transition ... 236

Appendix 5.11: Egonet for PU3 and Ties among Alters in Pre-Transition ... 237

Appendix 5.12: Egonet for PU3 and Ties among Alters in Post-Transition ... 237

Appendix 6: Actors and Their Ranked Power Resources ... 239

Appendix 6.2: The Alters and Their Ranked Power Resources in the Pre and Post-Transition Phases ... 239

Appendix 7: Showing Degree Centrality Scores in Both Phases ... 241

Appendix 7.1: Degree Centrality Measures. Pre-Transition. ... 241

List of Tables

Table 1: Relationship between Hypotheses and Research Questions ...63

Table 2: Results of Theme Analysis of Interviews and Frequency of Actors’ Names ...91

Table 3: Summary of Size of Egonets of Dominant Actors ...95

Table 4: Summary of Composition of Egonets of Dominant Actors ...96

Table 5: Principal Concerns of Parliamentarians who Contributed to the Debate in the House on the Creation of the IPO (2003) ...117

Table 6: Distribution of Power Resources among the Four Different Categories of Actors in the Pre and Post-Transition Phases ...124

Table 7: Key Activities Surrounding the Evolution of the IPO (2003), Classified According to Power Relation Type. ...127

Table 8: Social Power Relations Surrounding the Creation of the IPO (2003) ...129

Table 9: Instrumental Power Surrounding the Creation of the IPO (2003) ...130

Table 10: Key Activities on the Creation of the IPO, Resultant Power Relations, and the Conditions Under Which the Activities and Relations Occurred. ...132

Table 11: Key Activities on the Creation of the IPO, Resultant Power Relations, and the Conditions Under Which the Activities and Relations Occurred. (Continued.) ...134

List of Figures

Figure 1: Depicting Dobel (1999) Triangle of Judgment ... 22

Figure 2: Depicting Power Theory on IPO Construction ... 52

Figure 3: Example of Incident Matrix ... 80

Figure 4: Example of Asymmetric Adjacent Matrix ... 80

Figure 5: Example of Symmetric Adjacent Matrix ... 80

Figure 6: Netdraw Graph Displaying Pre-Transition Ties Among Actors ... 97

Figure 7: Netdraw Graph Displaying Post-Transition Ties Among Actors ... 98

Figure 8: Pre-Transition PRI 1 and Alters ... 99

Figure 9: Post-Transition PRI 1 and Alters ... 100

Figure 10: Pre-Transition PRI 2 and Alters ... 101

Figure 11: Post-Transition PRI 2 and Alters ... 102

Figure 12: Pre-Transition PU 1 and Alters ... 103

Figure 13: Post-Transition PU 1 and Alters ... 104

Figure 14: Pre-Transition PU 2 and Alters ... 105

Figure 15: Post-Transition PU 2 and Alters ... 106

Figure 16: Pre-Transition PU 3 and Alters ... 107

Figure 17: Post-Transition PU 3 and Alters ... 108

REMERCIEMENTS

Ce projet de recherche doctorale me signifie beaucoup. Il a été engendré par ma soif naturelle de nouveaux défis et nouvelles connaissances. Cependant, il a été alimenté par le désir intense de construire un monument pour célébrer l’esprit infatigable de mes parents et d’inspirer mon fils à être suffisamment ambitieux pour pousser continuellement au-delà des plafonds et des murs construits socialement, persévérant surtout dans l'adversité. Je dédie donc cette thèse à la mémoire de mon père défunt, Hubert Jean-Jacques, pour sa discipline et son amour; à ma mère, Ruthine James, pour son soutien et son inspiration; à mon fils, Kodie Jean-Jacques, pour son encouragement, son admiration, et son amour; et à ma «deuxième maman,» Myrtle, pour son amour et son soutien inlassable.

Certes, il y avait d'autres dans mon coin et je dois les saluer. A mon ami, Son Excellence l'Ambassadeur Aaron, je te dis un grand merci pour ton soutien sincère et généreux et à ma partenaire, Stéphanie, ton amour et ta patience m’ont beaucoup motivé. Merci Stephanie! À Laval, je me souviens de la première réunion (et des suivantes) avec mon Directeur de thèse, le Professeur Louis Imbeau. Le défi a toujours été de travailler assidûment, mais d'exceller en le faisant. Il a compris ma passion et il a été un guide et une inspiration. Merci, Professeur Imbeau. Professeurs Mathieu Ouimet (mon Co-Directeur), Jean Crête, Marc André Bodet, Éric Montigny, Thierry Rodon, Raymond Hudon, vous aussi, avez compris ma passion et vous avez été généreux au maximum dans votre direction. Je me suis toujours vraiment senti supporté quand j'ai parlé avec n'importe lequel d'entre vous. Votre magnanimité restera donc, pour toujours gravée dans mon esprit. Merci. Merci également au Professeur Jonathan Paquin, à l’équipe accueillante à la salle de musculation de PEPS et celle à la bibliothèque, à mes collègues, à mes amis, à mes fans et à mes proches. Votre chaleur a contribué sans doute à faire de mon expérience à Laval l’une des plus mémorables. Merci!

Il est clair que je n'ai pas fait ce voyage seul. Cette partie de mon voyage personnel a aussi été très spirituelle. Elle a renforcé ma conviction profonde qu'il y a une force suprême qui nous guide et nous protège. Grâce à elle, je me suis rapproché davantage à cette force pendant mon séjour au Québec, et je ne craignais point. Je n’ai jamais oublié que je n’étais pas arrivé à Laval uniquement sur ma propre volonté. «Le Créateur est avec moi,» je disais souvent. Je ne peux donc terminer cette étape de mon voyage sans reconnaitre et louer l'omniprésence du Créateur, le Tout-Puissant. J’espère que vous le retrouverez de nouveau, comme je l’ai fait.

Chapeaux à tous! Merci maman. Merci papa d’être mon ange. Merci Kodie.

Acknowledgements

This doctoral research project means a number of things to me. It began out of my natural thirst for new challenges and for knowledge. However, it has been fuelled by the intense desire to build a monument to celebrate the efforts of my indefatigable parents and to inspire my son to be ambitious enough to continually push beyond ceilings and socially-constructed walls, persevering especially in the face of adversity. I therefore dedicate this thesis to the discipline and memory of my deceased dad, Hubert Jean-Jacques; to the support and example of my mom, Ruthine James; to the encouragement, admiration, and love of my son, Kodie Jean-Jacques; and to the love and tireless support of my “second mom,” Myrtle.

Of course, there were others in my corner and I must salute them. To my friend, His Excellency Ambassador Aaron, big thanks to you for your sincere and generous support and to my partner, Stephanie, your love and patience have further motivated me. Thank you Stephanie. At Laval, I recall my first and subsequent meetings with my Director, Prof. Louis Imbeau. The challenge was always to work hard but to excel in doing so. He understood my passion and he has been a guide and an inspiration. Thank you, Prof. Imbeau. Professors Mathieu Ouimet (my second Director), Jean Crête, Marc André Bodet, Éric Montigny, Thierry Rodon, Raymond Hudon, you too, understood my passion and you have been most generous in your guidance. I always truly felt supported whenever I spoke with any of you. Your magnanimity will remain forever etched in my mind. Thank you. Thank you also to Prof. Jonathan Paquin, the faces at the PEPS weight room and at the library, my colleagues, my friends, my fans, and my loved ones. Your warmth helped made the Laval experience a most memorable one. Thank you!

It is clear that I did not do this alone. This portion of my personal journey has also been a very spiritual one. It has reinforced my strong conviction that there is a supreme force that guides and protects us. I re-connected with that force while in Quebec and I never feared; especially when I was down. I remembered that I did not arrive at Laval solely on my own volition. “The Creator is with me,” I often said. I therefore, cannot end this leg of my journey without acknowledging the omnipresence of the all-powerful Creator. I hope you will connect with the Creator as I did.

Hats off to all! Thank you mammie. Thank you daddy for being my angel. Thank you Kodie.

INTRODUCTION

During the 1970’s individual members of the government of former Prime Minister (PM) Patrick John were accused by opposition parliamentarians and civic-minded citizens of conspiring with unsavoury foreign elements to use the Caribbean island of the Commonwealth of Dominica (Dominica, from henceforth) as their personal fiefdom. For example, it has been revealed that towards mid 1970’s, the PM had entered into a “pact with a Texas businessman named Don Pierson that would have given close to one-tenth of the island over to a foreign company for just $100 a year” (Bell 2008:33) ostensibly to set up a free port on the island. PM John was also accused of entering into other arrangements with foreign leaders that were not open to the scrutiny of parliamentarians. Indeed, writing on the history of the Commonwealth of Dominica, the Encyclopaedia Britannica observes: “John’s government was implicated in a number of questionable dealings, including a scheme to lease land to a firm allegedly planning to supply petroleum illegally to South Africa, which was then under an international trade embargo because of its government’s apartheid policy” (Encyclopaedia Britannica Online n.d.).

Of further relevance to our present document is the work of renowned Dominican historian Dr. Lennox Honychurch (PhD) on that period in the history of the island. In chronicling the political career of former PM of Dominica, Patrick Roland John, Dr. Honychurch writes:

In 1979, heavily influenced by the Attorney General Leo Austin, the DLP [Dominica Labour Party] engaged in deals and took legislative action that stirred up the population in violent response. On 29 May 1979 demonstrators outside the House of Assembly were shot at by the DDF [Dominica Defence Force], several were injured and one youth was killed. Representatives of civil society gathered under the leadership of the Committee for National Salvation (CNS) and called for the resignation of the government. John and Finance Minister Victor Riviere did not resign … (Honychurch n.d.)

Mr. John was subsequently overthrown by an angry mob. As a related side note, Patrick John was later found guilty and jailed in Dominica for conspiring with a motley crew of Ku Klux Klan militants (an extreme racist and xenophobic entity in the U.S) and international mercenaries such as the Canadians Wolfgang Walter Droege and Larry Lloyd Jacklin for conspiring to overthrow the elected government and use Dominica as a base for their criminal enterprise. Stewart Bell writes extensively on that chapter in Dominica’s history in his book, Bayou of Pigs (Bell 2008).

The 1980 elections that followed the political demise of Prime Minister John saw the genesis of 15 years in power by the Dame Eugenia Charles (1919 – 2005), a former leader of the Dominica Freedom Party (DFP) and staunch ally of Ronald Reagan. Once in office, as it was in the case while in opposition, the Dame continued to promote integrity and good governance in government; once, reportedly dismissing a minister because he had ordered the use of a public excavator to work on his private driveway. Integrity in public office had therefore been a political issue for Dominica since the 1970’s; its emergence coinciding with increased global sensitivities regarding public management.

Elsewhere, during the 1980’s and 1990’s, notably in Britain and the US, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan had launched a campaign for what has been suggested as a re-conceptualization of and revolution in the way we manage the production of public goods and services. New Public Management it was coined. New Public Management (NPM) was not about integrity building per se, but it promoted a more inclusive political landscape, political accountability, and the rule of law. One of its principles was that the citizen, the client, was entitled to effective and efficient service and honest leadership from his leaders (Dunleavy 1994; Eliassen & Sitter 2008; Hood 1991). The rise of the NPM agenda

therefore coincided with the rise of discourses in Dominica about integrity and good governance in public office.

Equally significant is that during the rule of the United Workers Party (UWP) in Dominica, 1995 to 1999, the UWP government was accused repeatedly by the Opposition Dominica Labour Party (DLP) and private citizens of impropriety and mismanagement in office: graft, nepotism, blatant patronage, and waste. In fact, it was during its 4-year reign that Dominica saw the evolution of two civic-minded groups for the promotion of good governance: Transparency International (Dominican Chapter) and the Organisation for Good and Accountable Government. The political landscape had become more crowded and noisier with new actors using their resources to force the government to comply with existing laws and with international standards of good governance. Accordingly, during the election campaign of December 1999, the DLP then promised that once in government it would implement integrity legislation; that is, it promised that for the first time in Dominica’s history, the discourses for integrity in public management would have been institutionalized.

The Dominica Labour Party subsequently won the 1999 election campaign largely, it would seem, on a platform of anti-corruption and responsibility in public office. However, in resisting a petition demanding that the government in which he served implement integrity in public office legislation, Julius Timothy, a former Minister of Finance in the Commonwealth of Dominica lamented in 2008: “’The country was in the middle of an austerity programme and we were presenting to the Parliament an integrity legislation that would cost us in the region of 1.2 million dollars to operate on an annual basis…We are in a third world country, this is first world legislation’” (Dominica News Online April

former Italian president advised his countrymen: “Bribes are a phenomenon that exists and it’s useless to deny the existence of these necessary situations …These are not crimes. We’re talking about paying a commission to someone in that country. Why? Because those are the rules in that country.” He further described Italian condemnation of bribery in non-Western countries as, “absurd moralisms … If you want to make moralisms like that, you can’t be an entrepreneur on a global scale” (Frye 2013). Berlusconi was referring to the arrest by Italian prosecutors of a former Chief Executive of the defence technology giant Finmeccanica SPA on charges of illegal payments surrounding a helicopter deal with India.

These two positions are revealing. Berlusconi’s remarks reinforce the widely held view that developing countries facilitate, even institutionalize, corruption. However, what they both share in common is the perception that the political context in a developing country is manifestly different from what occurs in a developed country. In the former, there are cultural, institutional, and material phenomena that seem to frustrate the development of good governance principles.

In fact, it is this realisation that had prompted the World Bank to advance its good governance project. Moved by the failures of structural adjustment measures in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Bank concluded that the main reason for those failures was not that the reforms were bad political choices but that Sub-Saharan Africa suffered from bad governance (Carayannis, Pirzadeh, & Popescu 2012; Hilyard & Wilks 1998; Leftwich 1993; World Bank 1989). Good governance was therefore proffered as the best response to the development challenges that plagued Sub-Saharan Africa, indeed the developing world. The thrust of this agenda was, and still remains, the construction of an “enabling

environment entails wide ranging economic, institutional, political, and social reforms. It is possible to summarize the Bank’s good governance prescription as a recipe for development. Its main pillars are: efficiency in the public sector, the rule of law, transparency and accountability, and inclusion of civil society in the policy process (Graham, Amos, & Plumptre 2003; Kapoor 2008; World Bank 1989).

It must be noted therefore, that although the distinction is not often made, the Bank’s good governance project is functionally different from good governance as we know it in the West. In both contexts, the concepts are the same, mostly: thriving civil society, institutions of transparency and integrity, and the rule of law, and an efficient public sector, etc. However, both the goals and function differ. In the West, the pursuit of good governance assumes that development has already been achieved and therefore, good governance is simply a strategy to maintain the gains made. However, in the developing world, good governance has the inherent assumption that the target destinations do not have the requisite capacity for development and therefore, the creation of this capacity is a primary conduit leading to development. The Bank’s good governance recipe is meant to facilitate this capacity, irrespective of the socio-political context.

The recipe is consequently, a logocentric approach (Hollinger 1994) that seems to ignore the heterogeneity of the world political contexts. Hence, its implementation usually comes up against resistance or creates complications for local communities (Hilyard & Wilks 1998). This complication can be examined on two levels. First, good governance structures cannot be imposed in contexts of incompatible institutional and sociological superstructures. Second, the recipe assumes that more democracy will naturally lead to reduced conflict, less corruption, and

the relationship is not as direct and sustaining. A broadened political space in which the policy process is opened so that a multiplicity of actors can participate in the process simply creates more entry points for actors to interact with policymakers. In contexts deprived of the requisite institutional filters to manage this access, political inclusion could simply facilitate the type of bad governance that the good governance recipe seeks to avoid: Corruption and the subversion of the policy process by elites. The good governance model is therefore problematic for some countries. Yet, it is strongly recommended, indeed imposed, by the World Bank and its Bretton Woods partners. For the purpose of this thesis document, let us examine more closely the Dominican context and a brief overview of salient features of the Act in question.

The Commonwealth of Dominica

The Commonwealth of Dominica has been a parliamentary democracy since its independence from Britain on November 3, 1978. As per the Constitution, elections are due every five years. As in Canada, the Prime Minister is the head of government. In 2015, this head is the Honourable Roosevelt Skerrit. There is a President, but his role is largely symbolic – much as the Governor General’s position in Canada. In the last general elections (December 8, 2014), PM Skerrit’s party, the Dominica Labour Party (DLP), won 15 of the 21 constituencies on the island. Indeed, the party has been in power since 2000, having defeated the incumbent United Workers Party (UWP) in 1999, less than 5 years after the latter got into power. It is noteworthy that the United Workers Party has never conceded defeat after an election and, equally significant, is that the party has never stopped campaigning since the 1999 General Election. In that election, one principal issue was a claim by the Opposition, the Dominica Labour Party, of corruption in the UWP government. These claims have remained unproven although the DLP will point to examples of impropriety in the UWP government. There are three major political

parties: The Dominica Labour Party, the Dominica Freedom Party, and the United Workers Party. The latter is, in 2015, the official opposition.

On the international level, the foreign policy of the government has been characterised by efforts to create or deepen ties with non-traditional allies that share socio-political and economic histories. Consequently, Dominica is part of the Commonwealth, the Organization of the Americas, and the Francophonie. However, she has been nurturing her relations with the countries of Latin America, especially Venezuela, (for example, Dominica is an active member of the ALBA; a grouping of Latin American and Caribbean states that pursues a regional brand of social democracy that focuses on social and economic development) (ALBA-TCP n.d). In addition, in the last decade, the Roosevelt Skeritt administration has maintained or developed relations with China, the European Union, Cuba, Russia, India, and Morocco. Venezuela, China, and Cuba are Dominica’s “favourite friends” (DNO March 2012).

This decision to court non-traditional allies developed circa 2000 when Dominica had an IMF structural adjustment programme. As in the case of similar measures, the state was limited in its ability to finance public projects. The government's strategy was therefore to adhere to the agreement with the IMF while being sufficiently flexible and skilled internationally in order to attract foreign direct investment (DNO March 2012). One result of this strategy saw Dominica’s GDP of USD $ 0.324 billion in 2000 to USD $0.477 billion in 2011. In 2013, that figure was USD$0.517 billion. The rise is projected to continue to 0.533 billion in 2014 (Economywatch n.d).

Dominica’s economy is largely dependent on fragile industries, agriculture and tourism (especially eco-tourism), despite moves towards

for companies that outsource their operations. However, in 2015, the government is on a drive to develop the island’s geothermal potential so that it may export surplus energy to neighbouring islands. The projection is that by 2017, the island should have a fully operational geothermal plan that will provide the island with all its energy needs as well as allow for surplus electricity to be sold to the neighbouring French islands. Additionally, Dominica offers a legitimate and secure citizenship by investment programme.

A combination of a hostile global economic climate, natural disasters, and, arguably, bad governance meant that circa 2000 Dominica entered into an IMF structural adjustment programme. In addition, the IMF has recorded a deleterious effect of the recent fiscal crisis on the Dominican economy. However, reports and forecasts from the IMF and Economy Watch are favourable (Economywatch n.d., IMF 2013). Furthermore, according to Senior Energy Specialist at the World Bank, Miagara Jaywardena, speaking in Roseau in March 2013, the deficit has been declining (although public debt remains steady at 70% of GDP) (Dominica News Online March 2013).

The island’s administrative structure is modelled on that of the British. The Minister is the head of his ministry, but his work is facilitated by a permanent secretary (the Canadian equivalent would be “deputy minister“). There is no position of Assistant Deputy Minister. In the last ten years, Dominica has adopted several structures that are supposed to foster its development and its integration into the world, for example the Law on Prevention of Money Laundering (2000, updated in 2011) and the Integrity in Public Office Act (2003) (Integrity Commission n.d).

Integrity in Public Office Act (2003)

The Integrity in Public Office Act is Dominica’s first publicly known effort at institutionalising probity and integrity in the governance of the state. During the 1999 election campaign, the DLP Opposition promised the electorate that once in office it would create legislation that would oversee integrity in public management. This promise followed a series of allegations of impropriety in office against the UWP government of 1995 to 1999 by the then Opposition DLP. Indeed, following the 1999 General Elections, the Dominica Labour Party completed an inquiry into those allegations of corruption and subsequently tabled a report in parliament. However, this report has not resulted in the prosecution of a public official. The official explanation, as offered by sources close to the DLP, is that the PM at that time, Pierre Charles (1954 – 2004), thought that the cost of pursuing the alleged wrongdoers was prohibitive and consequently, the State had to abbreviate its anti-corruption agenda. The Dominica IPO emerged therefore, in a climate of conflict.

Yet, the Act may have had an even more complex genesis. Dominica had also found itself incapable of resisting exhortations and pressure from international partners to implement legislation that would improve the governance of the island.

Circa 2001, Dominica deepened its relationship with the IMF by adopting structural adjustment measures recommended by the organisation. This meant that the management of its finances came under heavy scrutiny by the organisation. There are no specific requests for integrity legislation made. However, working in consultation with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the IMF did urge the Skerrit government to ensure greater accountability and transparency in financial laws.

The FATF was originally set up by the G-7 countries to combat money laundering. It has since broadened its mandate to include efforts against financing terrorism. Most of its members are also members of the OECD. The IMF, the UN, the Organisation of American States, and the World Bank all have observer status in the FATF. Dominica is not a member of the Force, but it would seem that it has been a member of the Caribbean Financial Action Task Force (CFATF), itself, an Associate member of the FATF, since the creation of the CFATF in 1992. Hence, fearing that international governments and agencies would not help finance its projects and lift it out of its economic woes, the island logically complied with the demands of the Force.

In addition, the island, as a member of the Commonwealth, also felt obligated to design and implement public integrity legislation in light of the various declarations made by the Commonwealth of Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) directly or through their affiliate organs, such as the Commonwealth Law Ministers Meetings. In fact, the Harare Commonwealth Declaration of 20 October 1991, which was issued by Heads of Government in Harare, Zimbabwe, specifically reaffirmed the principles of “democracy, democratic processes and institutions which reflect national circumstances, the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary, just and honest government” (Commonwealth Secretariat 2004).

Indeed, the 1996 Commonwealth Law Ministers Meetings also listed efforts to maintain public integrity and “promote honest and accountable government” as an issue of “primary concern” (Commonwealth Secretariat 1996). For example, in 1996 the ministers supported the FATF forty recommendations (drawn up in 1990) and called on members to implement them. These recommendations are a package of structures

efficiency, and transparency in financial transactions globally, across borders and within borders. Consequently, when the Commonwealth of Heads of Government (CHOGM) met in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1997 they strongly urged that all member participants do more to enact anti-corruption and pro-integrity in public office legislation. Dominica participated at that meeting. The imperatives for placing public integrity legislation top on the political agenda of Dominican governments were therefore locally made and internationally relevant.

Logically therefore, once in office in 2000, the DLP government, led by Hon. Roosevelt “Rosie” Douglas (1941 – 2000), carved the IPO out of several existing integrity in public office acts from England, Trinidad, Barbados, Bermuda, St. Lucia; namely that of Trinidad. In 2000 Hon. Pierre Charles took over the reins of government and he, too, seemed determined to pass the Act. Consequently, in 2001, a first version of the bill was introduced in parliament by the then Attorney General, Mr. Bernard Wiltshire. It was a formal indication that the government intended to pass the Act. On April 30 2003, under the new leadership of Pierre Charles, the current version of the Act was debated and passed in parliament. Both sides of the House supported it.

However, the Act was not implemented in 2003. Hon. Roosevelt Skerrit was sworn in as PM January 8, 2004 following the sudden departure of his predecessor PM Pierre Charles. Two reasons are given for the delay. First, Dominica was still under IMF austerity programme and the island could not afford the implementation of the Act. Second, the Skerrit-led DLP administration thought that the 2003 legislation needed improvements before implementation. Hence, the Act remained unimplemented from 2003.

Structure of the IPO

The objective of this Act is to establish "probity, integrity, and accountability in public life and for related matters" (IPO 2003: 1). It targets parliamentarians, senior civil servants, and other persons who may be in private life but are members of governing boards of state or quasi-state institutions. The Act has several important features. First, the principal implementing organ is a commission called The Integrity in Public Office Commission, henceforth referred to as “the Commission” or “the IPO Commission.” The Commission is a semi-autonomous body. It is not answerable to the Cabinet, but its budget is determined by the Cabinet. It comprises seven members: A Chair, “who shall be a former Judge of the High Court, an attorney-at-law of fifteen years standing at the Bar or a former Chief Magistrate, appointed by the President on the advice of the Prime Minister” (IPO 2003) after the latter has consulted with the Leader of the Opposition. The Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition must each nominate two members who will be appointed by the president, the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Dominica or a similar body is empowered to also nominate a certified or chartered accountant, and the Dominica Bar Association must also recommend an attorney-at-law.

Second, the Act has limited investigative powers. It does not have prosecutorial authority. Investigations can only be launched upon formal complaints by an interested party. However, such complaints must pertain to named breaches of conduct by public officers within the jurisdiction of the Act. In addition, if the complaint is proven to be unjustified, the accused can take legal action against the complainant. If an inquiry indicates that an official is potentially liable under the Act, the Commission can then forward the file to the Prosecutor General for consideration.

A third feature of the Act is the requirement that public officials declare their assets and liabilities under confidential cover to the Commission. This must be done at the beginning of the official’s tenure and repeated annually. Indeed, in 2011, the Commission asked the Attorney General, in accordance with the IPO, to pursue certain policy makers and officials who had not submitted their application before the deadline.

The Act’s dormancy eventually became political ammunition for many, who suspected the Dominica Labour Party administration of delaying its implementation in order to first clean up traces of its corrupt acts prior to implementing the Act. Consequently, from 2006 the opposition, i.e. the UWP leadership and other actors who were not necessarily formal members of the UWP, embarked on a campaign to force the implementation of the Act. There were at least 3 groups of actors exerting pressure: the UWP leaders; a self-described non-partisan Citizens Forum for Good Governance; and some leaders of a US-based Dominican Diaspora community called the Dominica Academy of Arts and Science (DAAS). The Citizens forum subsequently formed a coalition with the UWP, a US-based pressure group, and individual citizens who were concerned about perceived bad governance of the state under the umbrella the Fund for the Defence of Democracy in Dominica. This Fund was active in seeking the implementation of the Act but its activities went beyond the mere implementation of the Act. The group targeted a broader agenda of good governance in Dominica and also participated in efforts to force the government to implement the IPO. Many of the members of the Citizens Forum for Good Governance were actually former senior members of the DLP, e.g. the Attorney General (AG) who had first tabled the IPO in the parliament, a former government minister, and a former senior party member.

For a while, the Skerrit administration resisted but the opposition persisted and succeeded in returning the IPO on the political agenda. They never stopped campaigning for the adoption of the law until the Prime Minister ceded. Five years after it was debated and consented to by parliamentarians, the President assented to the Integrity in Public Office Act on August 5, 2008 and it became operational as of September 1, 2008.

Not surprisingly, however, opposition politicians insist that the Prime Minister and his cabinet have manipulated the date of entry into force of the IPO - September 2008 - in order to protect himself and his colleagues from examination for certain illegal acts they would have had committed prior to September 2008.

Purpose, Research Question, and Thesis Statement

This thesis studies and discusses how one developing state, the Commonwealth of Dominica, approached the development of an act to oversee integrity in public office, the Integrity in Public Office Act (IPO). In light of the context of political conflict and mobilization in which it evolved, the thesis focuses on power relations surrounding the developing of this Act. It aims to understand and explain how structural and agential factors have resulted in the creation of this Act. We assume that a context of institutional deficiency but with political openness presented special opportunities for studying power relations among actors. The principal guiding question is therefore: Why did the state develop and implement the current design of the IPO (2003). Our central premise is that “rational” actors, cognizant of their structural position in a network of actors, have used their power resources to choose and model an institution so that it serves them and their allies. Their power and their behaviours are consequently, a reflection of their understanding of their position in a network of actors. Indeed, we define

“rational actors” as those actors who deliberate and strategize to advance their interests. Manifestly, such actors engage in self-maximizing behaviour.

Justification for the Research

Through an examination of this power play among rational actors, this thesis aims broadly to contribute to the discourse on building democratic institutions. We can discuss some more specific benefits to political science; theoretically, methodologically, and empirically.

Theoretically, first, this research attempts to respond to the paucity of studies on the design of institutions of public integrity. The conventional approach to the choice and design of institutions of integrity is holistic, incorporating all facets of society (including the private sector). However, research into such institutions has been limited to conceptual and organizational themes (Coghill 2004; Roberts et al. 1992). Additionally, there remains a dearth of studies on the role of networks on the choice and design of public integrity institutions. There is even less empirical evidence regarding how informal networks are used to influence formal ones (Donnet 2012). This study therefore adds to the literature on institutional choice and design of integrity oversight bodies.

Indeed, a critical component of the processes involved in creating an institution to oversee public integrity is the role of networks of actors in the policy process (politicians, senior bureaucrats, technical experts, media, etc.). A second achievement of this study is therefore, the enrichment of the literature on the evolution of a public institution through a study of both structural and agential features of such networks. Political Science accepts that actors use their power resources to advance their interests and therefore, institutional design can be understood as the result of deliberate political action, or non-action. We

believe that it is not enough to merely acknowledge that actors use their power to their own ends. This study offers insight into how rational actors deploy their power resources, i.e. what power resources they use, against which actors they use these resources, and what determines how much of their power they use. It therefore goes beyond merely using network analysis techniques to study a theme. It embraces a theory that acknowledges both structural and agential explanations of institutional design.

Third, by studying the choice and design of institutions of public integrity from the perspective of power relations among actors, we introduce a perspective that allows integrity and anti-corruption reformers to correctly target the interstices and structures that facilitate corruption or hinder the system-wide development of integrity and probity in public governance. Typically, challenges to public integrity are seen as a management issue. Solutions are therefore, studied from an institutional perspective: Build more institutions and the problems will be corrected. This study highlights the deficiencies with this logic and suggests that understating public integrity from a power perspective is likely to lead to more realistic and context-appropriate strategies at creating institutions of public integrity. Reformers could then use appropriate mechanisms (legislation, counter-information or propaganda, or public activism, etc.) to thwart attempts at subjugation of integrity networks. Moreover, our effort in Chapters 4 and 5 to measure and discuss specific degrees of power employed by actors and to record the conditions in which these degrees are exercised advances our understanding of actor behaviour in the policy process and enhance our capacity to predict structural conditions that will engender in certain types of actor behaviour. Hence, by shifting the focus from largely organizational variables to the interplay among actors, this study adds

public integrity, that of actor behaviour vis à vis integrity reforms; especially as this behaviour pertains to contexts of embryonic democracy and weak institutional support.

We also see methodological advancements in this study. In Chapter 3, we explain that we used social network analysis (SNA) techniques in this study. SNA emphasises power as a result of network centrality.Yet, there has been little work done on the conditions, structural and attributes, that determine how actors actually deploy their resources to effect a desired change. This study advances work towards filling this gap. Structural positions, the study shows, interrelate with agential considerations, viz the actor’s selection and intensity of power resources. A case study of Dominica’s IPO that focuses on both agential and structural features of power relations adds clarity and precision to the literature and permits comparisons between similar studies in similar contexts. Methodologically, this study can claim to be unique.

Finally, empirically, the study advances the literature on how actors in developing countries and contexts of burgeoning democracy use their power within informal networks and across informal and formal ties. Additionally, Dominica’s IPO is unexamined in the published literature. The study therefore, offers the Dominican public a record of the process that preceded the IPO, an analysis of the power structure involved in the governance of the island, and a vision for improving the policy process so that its outcomes are representative of the will of the majority. This study therefore, has much empirical value to political science.

Summary

We reiterate that the underlying problem that has triggered this study is the observation that current efforts creating democratic structures appear to create new opportunities for political conflict that are not easily

resolved in contexts that have a deficient institutional infrastructure. Societies that seem to lack certain support structures and a reservoir of democratic support (Dalton 1999; Mcallister 1999; Norris 1999), “reservoir of democratic capital” (Dalton 2004:1999) as in the case of Dominica (only receiving suffrage in 1941, e.g.), appear most at risk. In such contexts, we believe, powerful political actors appear to engage in a power play that goes unchecked and that results in policies that reflect the interests of a dominant actor. This original research therefore examines how actors use their power resources to advance their interests as a result of their understanding of their position in a network of actors. In the next chapter we will discuss the conceptual framework of this thesis.

Structure of the Thesis

In order to explore this thesis, this document has been divided into 5 chapters, in addition to the introduction and conclusion. Each chapter is further sub-divided into subsections where necessary in order to facilitate reading. The first two chapters lay out the theoretical frame of the thesis. The third describes the method used to search for responses to the research question. Chapters 4 and 5 deal exclusively with the data obtained. In Chapter 1, we conceptualize public integrity and discuss some concepts that are central to this thesis. This discussion is important because it describes common approaches to the design of institutions of public integrity and concludes with a typology of such institutions. In Chapter 2, we explain our theory on the design choice of the Dominican IPO. To do this, we discuss theories that are central to our thesis; namely, the structure and agency debate, power, and power in social networks. In Chapter 3, we detail our methodological approach to the problem. At the core is the use of social network analysis (SNA) and qualitative techniques. Methodologically, therefore, this study takes on a micro view of the development of the Act by studying principal

actors and on a lower level, their alters. Chapter 4 offers a detailed description of the results. Having laid out the theoretical framework of the thesis that clearly describes situates the Dominican IPO and described the results that emanated from our research, we proceed in Chapter 5 to discuss the results and explain how and why the current model of the Integrity in Public Office Act was created. The thesis ends with concluding statements pertaining to the research question and hypotheses. Throughout the text the masculine form is used in a generic manner.

Summary of the Introduction

Having thus described the contextual background, the structure of the thesis, and the major contributions of this thesis to political science, we now turn to its theoretical framework, which we elaborate in the next two chapters.

CHAPTER 1: CONCEPTUALISATION

We recall that the central question in this dissertation is, why did the state develop and implement the current design of the IPO (2003). The aim of this chapter is to create a reference frame in which we can situate the Dominican IPO so that we may better understand its design and subsequently, how this design may be a direct result of calculated actor behaviour. The effort to create this frame is organized into four principal sub-sections. First, we define and discuss public integrity as a central concept of this study. Second, we discuss various types of institutions employed to oversee public integrity. This discussion is very important because embedded in the principal question guiding this study is the issue of the choice of institution to address perceived deficiencies in public integrity. Third, choice and design are closely related to the functions of the institutions. Consequently, we briefly discuss the various functions of public integrity oversight bodies. Fourth, we offer a typology of institutions that are created to oversee public integrity.

1.1 Public Integrity

The dictionary’s conceptual definition for “integrity” does not differ from that which writers in academia seem to have attributed to the concept; that of wholeness or coherence among different parts (Hamlin 1999; McFall 1987; van Luijk 2004). This coherence is manifested in at least two different dimensions. First, integrity is the coherence between the values of an actor and his behaviour. It pertains to: “the state of being ‘undivided’; an integral whole….Integrity requires ‘sticking to one's principles’, moral or otherwise, in the face of temptation, including the temptation to re-description” McFall (1987:4). For McFall, integrity is clearly a concept that speaks of the individual being one with himself, displaying a seamless rapport between his values and personal conduct; doing as he preaches, as it were. Second, integrity is also the fit between an actor’s standards (internal moral compass) and those of another

(Hamlin 1999; McFall 1987; van Luijk 2004). It speaks of the coherence between the actor’s personal values and those of the environment in which he exists. It describes the harmony between societal demands and agential preferences. In either dimension, the key concept is consequently, “coherence” or “wholenesss;” wholeness between an actor’s values and his behaviour or an actor’s values and those of the structures in his environment.

It is the second conceptualisation of integrity however, that is most relevant to our research because it addresses the juxtaposition between agential attributes and structural forces. In addition, this conceptualisation already suggests the potential for conflict between the actor’s values and those emanating from the structures around him. If integrity pertains to coherency and wholeness between one’s standards and those of society, public integrity can be defined as the fit between personal and public values; that is, public integrity emerges as achieved equilibrium between structure and agency. It is “achieved,” we believe, because the actor has to work at building this equilibrium, it does not occur naturally.

Dobel (1999) develops a triangle of judgment that elucidates this perspective of conflict in the search of coherence. In the author’s view, public integrity is “an iterative process among three mutually supporting domains of judgment – obligations of office, personal commitment and capacity, and prudence” (20). Office obligations pertain to the formal obligations of the actor’s job. However, the individual is not without personal moral attachments that interact with his formal obligations. Prudence therefore, is the intervening grey area in which the official connects his commitment to his job and his moral values so that the policy outcome serves the society that he is appointed or elected to serve.

accurately relate the three points of the triangle so that some harmony is achieved among them. Figure 1 below offers a graphic representation of the triangle.

Figure 1: Depicting Dobel (1999) Triangle of Judgment

We find Dobel’s (1999) analysis of the concept apt to our study because it highlights accurately the interplay between agency and structure, which appears fundamental to the development of institutions that are intended to oversee integrity in public office, such as the Dominican IPO. Integrity in Dobel’s view, is not simply the coherence between the actor’s values and his behaviour. The concept of wholeness transcends the actor and describes the equilibrium among three key variables: the actor’s values, those of society, and his behaviour.

In summary, we conceptualize public integrity as an equilibrium between an actor’s personal values, public obligations, and public values. It is an equilibrium that is borne out of the fit among the above three variables. However, we argue that this equilibrium is likely the result of a struggle as the actor seeks to create the “wholeness” among parts that may be in conflict with each other. Measures to oversee public integrity are therefore, an arena for potential conflict because each actor is constantly seeking that balance among the three points in the triangle, which all

Personal capacity and commitments

integrity building through this lens, of conflict, we can logically perceive the choice and design of the IPO Act (2003) as a theme to be studied from a power perspective as opposed to an institutional concern.

1.2 Institutions: Choice and Design

Indeed, there are a number of different institutions that are used to oversee public integrity in democracies (Pelizzo & Stapenhurst 2008; Stapenhurst et al. 2008); that fit between actor values, societal values, and actor behaviour. They may differ in their institutional location and their principal focus. However, they all seek to facilitate the seamless relationship among three principal variables as suggested by Dobel (1999) above: Actor values, structural considerations, and actor behaviour. Let us briefly examine a few here in an effort to begin situating the Dominican IPO; an exercise that is critical if we are to better understand the evolution of that institution and to lend theoretical and conceptual clarity to our research.

Common examples of public integrity oversight institutions are the offices of the auditor general and the inspector general (in the U.S) that oversee public expenditure and investigate breaches of public finance management. Similarly, some jurisdictions have a Public Accounts Committee. Usually headed by the Leader of the Opposition, the committee has the authority to summon any public official (functionary or politician) to answer questions it may deem necessary, to examine the public accounts, and to investigate and examine all the issues that are referred to it by parliament. Additionally, there is a parliamentary Ombudsman that exists in some jurisdictions and is largely responsible for investigating complaints by citizens regarding public administration. A customary feature of institutions of public integrity is that they usually emerge following reports of scandalous behaviour by public officials. Hence, governments sometimes institute commissions of inquiry. These

have a limited lifespan but they are meant to shed light on perceived scandalous behaviour in public management. Another common practice is to establish certain legislative or extra-parliamentary oversight committees (Stapenhurst et al. 2008) to investigate specific perceived breaches. Finally, the literature also describes various specialised anti-corruption agencies (ACAs). Unlike other institutions mentioned above, such agencies are created with the expressed objective of combating corruption and/or promoting public integrity. Integrity commissions are one such anti-corruption agency. The choice of an institution for overseeing public integrity is therefore contingent on the purpose for which this institution is created. Let us advance our understating of the Dominican IPO by examining more closely the myriad functions of different ACAs.

1.3 Purpose of Integrity Bodies

Integrity oversight bodies seem to have at least four main functions: prevention of corruption, build public trust, education, and to guard the public interest (Doig 1995; Gilman & Stout 2005; OECD 2013; Pope 2000). The emergence of such bodies usually follows public scandals or rumours of scandalous behavior by public officials. Consequently, some are meant to appease the public, keep public officials in line, and maintain social order. Oversight is seen therefore as also a strategy for managing the behaviour of public officials (Verhezen 2008), a “tool for checking the behaviour of the system’s single most powerful political actor” (Stapenhurst et al. 2008: 18). Thus, some oversight bodies have the authority to initiate investigations and prosecute or recommend the prosecution of those perceived to be guilty (Pelizzo & Stapenhurst 2008); all this in an effort to positively influence the behaviour of public officials.

The trust-building function of public oversight bodies suggests that if a citizenry perceives public officials to be of high integrity, i.e. if it is

perceived that there is coherence between the values and behaviour of those officials and the values of the society, they are more likely to support their decisions. In turn, this support will consolidate the legitimacy of the institutions and the individual actors who head them. Nevertheless, as Nieuwenburg (2007) concludes, using public trust as a goal of integrity agencies is a paradox because “one cannot use the trust argument to justify a commitment to integrity in conditions of declining trust” (217). Notwithstanding their trust-building potential, integrity bodies as trust building institutions must evolve in a broader context that aims at building trust and can hardly be seen as simply an ad-hoc reaction to crises.

Consequently, oversight bodies have a broader educative role (Corruption Research Centre 2000; de Sousa 2010; Doig & McIvor 2003; Pope 1999, 2000). Such institutions recognize public integrity as embedded in a wider environment of actors and consequently, seek to establish integrity and fight corruption through wider public sensitization programmes.

A final group of oversight bodies has a largely paternalistic role. This is the case with many regulatory agencies, e.g. the U.S Food and Drug Agency and Environmental Protection Agency (Uchtmann & Nelson 2000) and Health Products and Food Branch Inspectorate in Canada. Such agencies employ various strategies of regulation and accountability to ensure that the regulated industry complies with a standardised mode of conduct and does not comprise the security, physical or health, of the wider public (May 2007). In addition, some other agencies also pursue a largely performance-monitoring role, but still within the framework of aligning private interest with public expectations and norms; e.g. Uganda’s National Water and Sewerage Corporation’s (NWSC), which focuses on the quality of technical and managerial inputs into the

these differ in focus from the oversight bodies, but they all exist to ensure that certain norms and standards are upheld by the public official.

Public integrity oversight bodies therefore, vary in their function but it is clear that they all have at their core the institutionalisation of conduct by public officials that is in line with what is perceived to be societal norms and expectations. Similarly, such institutions also create structures that seek to deter, report, and even prosecute behaviour that may depart from that which is sociologically palatable. Above, we did explain that an institution that oversees integrity in public office is a specialised anti-corruption agency. In order to advance our understanding therefore of the Dominican IPO, in the next section, we examine the question of the institutional design of an integrity in public office act more closely through a typology of models of specialised anti-corruption agencies (ACAs).

1.4 Typology of IPOs

We recall that public integrity is the equilibrium between three main variables; notably, the agential attributes, structural characteristics, and agential action (or non-action). The raison d’être of such ACAs is consequently, to facilitate this equilibrium. Thus far, we have shown that there are different types of institutions pursuing this equilibrium. The literature however, is weak on an ideal-type among these. Yet, the establishment of an ideal-type is significant to our thesis because it allows us to better examine and discuss the evolution of the Dominican IPO. An ideal-type IPO therefore, adds analytical rigour to our thesis.

Dunga (2010) and the OECD (2013) offer one classification that could begin to illuminate this area of interest to us. Their typology identifies three broad categories of institutions: Multi-purpose bodies (with law

enforcement powers); Law enforcement bodies (police and/or prosecutors); and those that focus largely on preventive measures. Multi-purpose bodies owe their nomenclature to the fact that they take on at least three principal activities: prevent, educate, and investigate. This model is usually cited as the most comprehensive and most ideal-type available. The Hong Kong Independent Commission against Corruption (a frequently cited exemplar of effective and comprehensive ACA, never mind the fact that it is the Chief Executive, alone, who appoints commissioners) and the Singapore Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau fall within this category. Law enforcement bodies take on one or all of at least three activities: detection, investigation, and prosecution bodies. Two examples are the Norwegian National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime and the Belgian Central Office for the Repression of Corruption. For their part, prevention agencies are very diverse but their activities remain focused on public education in order to discourage corruption. The OECD typology could help us situate the Dominican IPO. However, it focuses a lot on the functions of ACA’s and ignores other salient features of such agencies (e.g. its location, composition, etc.) and it is therefore, incomplete. In fact, even its ideal-type, which in the literature, appears to be embraced by many, appears to be weak on autonomy. We therefore find ourselves with a few suggested key features for an ideal-type but without an actual example that satisfies our barometer for autonomy.

Consequently, we refer to the review of the literature in order to design the type of institution that can ideally pursue the equilibrium among three variables of which we spoke above. Several writers suggest that there are six themes that are central to such institutions, each comprising two dimensions (Brown & Uhr 2004; Coghill 2004; Doig 1995; Head 2012; Langseth et al. 1997; Pope 1999):