The Present Perfect in since-clauses: the interaction

with different types of predicates

Mémoire

Gabrielle Morin

Maîtrise en linguistique - avec mémoire

Maître ès arts (M.A.)

The Present Perfect in since-clauses: the interaction

with different types of predicates

Mémoire

Gabrielle Morin

Sous la direction de :

Résumé

Ce mémoire est une étude sémantique ayant comme sujet l’utilisation du Present Perfect dans les constructions temporelles introduites par la conjonction since en anglais. Le Simple

Past étant la forme verbale la plus fréquente dans ce type de constructions syntaxiques telles

que « She has been my friend since we were at school together », le Present Perfect est tout de même parfois utilisé par les interlocuteurs de l’anglais, comme dans « I have known you since I have lived in Quebec City ». Le but de la présente étude est donc de démontrer qu’il existe une certaine corrélation entre l’utilisation du Present Perfect et les différents types d’évènements/prédicats dans ce type de construction. Pour ce faire, la catégorisation des évènements en accomplissements, achèvements, activités, et états décrite par Vendler (1957) sert de base pour classer les 527 contextes de corpus utilisés. Dans ce sens, la signification intrinsèque de chaque type de prédicat, en combinaison avec l’influence d’éléments de durée présents dans la phrase principale tels que « It’s been twenty years since… », a une influence sur quelle forme verbale entre le Present Perfect et le Simple Past est la plus fréquente dans ce type de construction pour chaque type de prédicat. Il deviendra aussi clair que l’utilisation du Present Perfect dans les since-clauses n’est pas si rare qu’on peut le croire. Cependant, il est souvent possible de le remplacer par le Simple Past, ce qui nous amène à nous questionner sur le rôle et l’utilité du Present Perfect dans les propositions introduites par since.

Abstract

This thesis is a semantic study of the behaviour of the Present Perfect in temporal clauses. The Simple Past being the most commonly found verb form in temporal since-clauses of the kind She has been my friend since we were at school together, there are times when speakers of English use the Present Perfect instead, such as in I have known you since

I have lived in Quebec City. The purpose of this study is therefore to show a correlation

between the use of the Present Perfect and the different types of events/predicates in this type of construction. To do so, Vendler’s (1957) categorization of events into accomplishments, achievements, activities, and states is used as a basis for the classification of the 527 corpus results examined in this study. In this sense, the intrinsic meaning of each type of predicate, combined with the influence of durational elements in the main clause such as It’s been

twenty years since…, has an influence on whether the Present Perfect or the Simple Past is

the most frequent verbal form used for each type of predicate. It will also become apparent that the presence of the Present Perfect in since-clauses is not as rare a phenomenon as one might think. However, in some cases, the Present Perfect can be replaced by its counterpart, the Simple Past, leading one to seek the reason for the choice of the Present Perfect in since-clauses.

Table of Contents

Résumé ... ii

Abstract ... iii

Table of Contents ... iv

List of Tables ... vi

List of Diagrams ... vii

List of Abbreviations ... viii

Acknowledgements ... ix

Introduction ... 1

Stating the Problem ... 1

Rare Phenomena in Language ... 3

Since and the Present Perfect ... 5

Chapter 1 Theoretical Framework ... 7

1.1 Literature Review ... 7

1.1.1 The Conjunction since ... 7

1.1.2 Present Perfect ... 11

1.1.3 Tense and Aspect ... 11

1.2 Types of Predicates ... 13

1.3 Hirtle’s analysis of the Present Perfect ... 20

Chapter 2 Research Method ... 22

Methodology and Hypotheses ... 22

Chapter 3 Data Analysis ... 25

3.1 Events and Durations ... 25

3.2 Achievements ... 27 3.2.1 Definite Durations ... 27 3.2.2 Indefinite Durations... 30 3.2.3 No Expression of Duration ... 36 3.3 Accomplishments ... 40 3.3.1 Definite Durations ... 40 3.3.2 Indefinite Durations... 41 3.3.3 No Expression of Duration ... 43

3.4 Activities ... 46 3.4.1 Definite Durations ... 46 3.4.2 Indefinite Durations... 47 3.4.3 No Expression of Duration ... 50 3.5 States ... 51 3.5.1 Definite Durations ... 51 3.5.2 Indefinite Durations... 52 3.5.3 No Expression of Duration ... 53

3.6 Any and Some ... 56

Mini-Study ... 56

Conclusion ... 64

Findings ... 64

References ... 69

Appendix A ... 71

Corpus results for Achievement predicates (187 contexts) ... 71

Appendix B ... 86

Corpus results for Accomplishment predicates (79 contexts) ... 86

Appendix C ... 92

Corpus results for Activity predicates (160 contexts) ... 92

Appendix D ... 103

Corpus results for State predicates (101 contexts) ... 103

Appendix E ... 110

List of Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Present Perfect and Simple Past in since-clauses with pronouns……4 Table 2: Quirk et al.’s (1985) situation types……….18 Table 3: Xiao & McEnery’s feature matrix system of verb classes………19 Table 4: Percentages of the number of events for each of the duration contexts……….67

List of Diagrams

Diagram 1: Hirtle’s tenses of English………12 Diagram 2: Percentages of examples for each category of events………..26 Diagram 3: Number of contexts for each category of events………..26

List of Abbreviations

ACC: Accomplishment ACH: Achievement ACT: Activity

BNC: British National Corpus

COCA: Corpus of Contemporary American English DD: Definite Duration

ID: Indefinite Duration

NPI(s): Negative Polarity Item(s) SPast: Simple Past

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Duffley for his help and support throughout the writing of this thesis. His knowledge and teaching of English grammar have always inspired and helped me as a non-native speaker of English to understand in more depth the fascinating discipline that is English grammar. I am thankful to have been under his direction throughout my time in the master’s program. I would also like to thank my parents and sister for their psychological support as well as their understanding throughout my time at Laval University.

Introduction

Stating the Problem

This study will investigate the conditions under which the Present Perfect can and cannot be used in since-clauses. First of all, such a study will cast greater light on the workings of the Present Perfect, a form which combines both tense and aspect. Most grammars deal with this construction as a simple tense belonging to past time (cf. Leech 2004: 35), thereby obscuring its more complex meaning, which combines present tense with perfect aspect. Since the Simple Past is the default form in since-clauses, this investigation can also bring greater clarity to describing the difference between the Present Perfect and the Simple Past: are they really just two ways of denoting a past event? Finally, it can help second and foreign language learners of English acquire and understand more easily this complex and often misinterpreted verb form and its usage.

Over the last 60 years there have been numerous studies on the difference between the Present Perfect and the Simple Past in English. There have also been studies on the various temporal adverbials and their function in syntactic constructions. For example, Hirtle (1975a) has written on the difference in meaning between during and for in relation to time. As he points out, the preposition for is used to measure the time of an event in its entirety, contrasting it with during, which does not measure, but dates the moment of an event’s happening:

(1) He lived in England for the summer. (2) He lived in England during the summer.

Also, when for is used, the entire duration of the event, from beginning to end, is implied, while with during the event is not necessarily understood to have taken place for the entirety of the duration implied:

(3) He stayed here for the summer. (4) He stayed here during the summer.

With since, the entire duration is comprised in the event’s occurrence, from a specific moment in the past defining the beginning of a duration up until the present, bringing since in relation with for in cases such as:

(5) He has known her for three years.

(6) He has known her since three years ago/2016.

Consequently, one can say that for measures the length of time of an event’s happening and during only dates it in time, while since can be said to combine elements of both of the other two prepositions because it both dates the past moment when an event occurred as the beginning point of a stretch of time, and it measures that duration as stretching up to another point in time, usually the present of speech.

However, few grammarians have looked at the interaction between verb inflections and clauses with temporal conjunctions. Werner (2013) has investigated the interaction between the Present Perfect and Simple Past alternation and temporal adverbials. Through the use of corpus data, Werner shows that the temporal adverbial since is mostly used with a Present Perfect form in the main clause – rather than a Simple Past – across all varieties of English examined in his survey (p. 227). However, Werner’s study does not examine the verb forms occurring in since-clauses; rather it deals only with the adverbial use of since illustrated in the context cited below:

(7) The Government has since relaxed the requirement for four years’ teaching… Yet, as most studies in the literature show, because of the definite past meaning of the Simple Past, this form is the logical verb tense to be expected in clauses introduced by the definite time-point adverbial since:

(8) It has been a few years since she ran a marathon.

If this is the case, the question arises as to why it is possible to use a Present Perfect in temporal clauses introduced by this conjunction as in (9) below:

(9) I’ve known him since he has lived on this street.

One might be tempted to account for this by the fact that the first sentence expresses an action-like or dynamic event, whereas the second expresses a stative one. However, this explanation is not applicable to the following sentence which involves an action-like (dynamic) event:

(10) It has been two years since you’ve worked.

There is a difference between (8) and (10) however, in that ran a marathon is an accomplishment whereas worked denotes an activity. This suggests that the aspectual category to which the event belongs (cf. Vendler, 1957) is a relevant factor for the present study.

Rare Phenomena in Language

Although the use of the Present Perfect in temporal since-clauses is not a frequent occurrence, it is important to study this phenomenon for various reasons. First, rare or infrequent language usage can help shed light on the normative uses, as is the case in the present study which deals with a somehow infrequent collocation. Second, although linguists of the Generative approach, such as Chomsky (1981), support the claim that only “core” language structures matter for the study of language, there must be some reason why language users have recourse to “peripheral” structures in discourse. Thus Goldberg (2003) argues that marginal or infrequent uses are just as much part of the language as normative ones, which means that they are of interest to the linguistic analyst as they may have semantic import which is different from the norm. For example, as Goldberg shows, the article the is supposed to accompany a noun in order to create a noun phrase or clause; however, that is not the case in sentences such as “The more you think about it, the less you understand” (2003: 220), in which the definite articles are not attached to any noun and therefore are not creating noun phrases or clauses. Nonetheless, this type of sentence is completely grammatically acceptable and widely used by native and non-native speakers. The fact that it is not a common pairing – the article with a comparative instead of a noun – does not mean that it should not be used or understood. Moreover, the article evokes a certain definite quantity of additional thought to which corresponds a certain definite quantity of additional understanding in this type of use, which shows that it is not unrelated semantically to the other uses of this form.

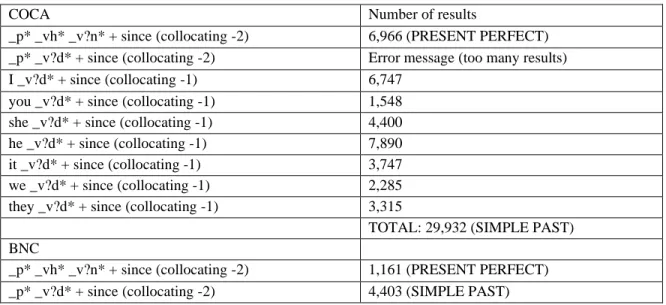

Moreover, the use of the Present Perfect in syntactic constructions which normally allow a Simple Past such as since-clauses is not as infrequent as one might believe, as shown in a quick corpora search conducted for the purpose of this study. In order to demonstrate

how rare the presence of the Present Perfect in since-clauses is, a basic search on both British National Corpus (BNC) and Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) databases – respectively containing around 100 million and 1 billion words – comparing the use of both Simple Past and Present Perfect in this clause was conducted, as shown in Table 1 below. First, a search using the pronoun + have + past participle string, occurring after since, gave 6,966 results in COCA and 1,161 results in BNC, both corpora including the Present and Past Perfects. Then, by replacing the have + past participle string with verb ending in -ed, the search in BNC gave 4,403 results, which is almost four times more results than with the Present Perfect. As for the use of the Simple Past in COCA, the search pronoun + verb ending

in -ed was too vague to be done, the website giving the error message that one of the string

search elements occurred more than 40,000,000 times, so it had to be narrowed down. By searching one pronoun at a time amongst I, you, he, she, it, we, and they with the Part of Speech tag verb ending in -ed, the search gave 29,932 results in total, which is more than four times the search for the Present Perfect including all pronouns. However, one thing to be noticed here is that the search for all instances of the perfect form includes the Past Perfect as well, and so does the search for the -ed ending verbs, due to the fact that the Past Perfect uses the past form of have. Also, the search might not only include temporal since-clauses, but causal since-clauses as well.

Table 1: Comparison of Present Perfect and Simple Past in since-clauses with pronouns

COCA Number of results

_p* _vh* _v?n* + since (collocating -2) 6,966 (PRESENT PERFECT) _p* _v?d* + since (collocating -2) Error message (too many results) I _v?d* + since (collocating -1) 6,747

you _v?d* + since (collocating -1) 1,548 she _v?d* + since (collocating -1) 4,400 he _v?d* + since (collocating -1) 7,890 it _v?d* + since (collocating -1) 3,747 we _v?d* + since (collocating -1) 2,285 they _v?d* + since (collocating -1) 3,315

TOTAL: 29,932 (SIMPLE PAST) BNC

_p* _vh* _v?n* + since (collocating -2) 1,161 (PRESENT PERFECT) _p* _v?d* + since (collocating -2) 4,403 (SIMPLE PAST)

However, apart from the fact that both the Present Perfect search and the Simple Past one provide results out of the scope of the intended search, it still gives us the difference in frequency for both corpora on the actual usage of both verb forms in since-clauses: the Present Perfect occurs approximately four times less than the Simple Past in since-clauses. This is evidence that the Present Perfect is less frequent in this type of clause, in comparison with the Simple Past, but corpus data also shows that it nevertheless occurs in 20.9% of British usage and 18.9% of American, giving support to the relevance of studying this phenomenon. As a matter of fact, if rare phenomena are worth researching, studying, analyzing, and understanding, phenomena like the one concerned in the present study – which represents approximately 20% of language usage – are certainly worth it as well. Indeed, it is surprising to witness a total lack of research on the use of the Present Perfect in temporal

since-clauses as it turns out to be significantly frequent after all.

Since and the Present Perfect

The conjunction since is definite in meaning; it represents a specific past moment, which corresponds to the beginning of an event that unfolds over a subsequent time-period:

(11) I’ve lived here since 2012.

(12) I’ve known you since we went to school together.

In (11), the conjunction denotes a specific past moment representing the beginning of the event of living here over a period of eight years up to the present, whereas in (12) the event of going to school together is viewed as a past moment that initiated the time-period over which the speaker has known the hearer.

The Simple Past tense is also definite when it is used with dynamic events; it represents a specific past event or situation that started and ended in the past (i.e. completely accomplished in the past and is over at the present moment), as in (13) in which yesterday is past and over with, which implies that the subject is not at the store anymore:

(13) I went to the grocery store yesterday.

However, when it is used with stative events, the Simple Past can be either definite (14) or indefinite with no clear beginning or endpoint (15):

(15) The old man was exhausted.

The Present Perfect, in contrast, does not imply definiteness; it represents an event or a situation that started in the past, but that can either continue to the present (16) or involve a result phase that is itself in the present (17):

(16) I’ve lived in Quebec City for 10 years. (17) I’ve lost my keys! (from Hirtle 2007: 35)

Both the Present Perfect and the temporal conjunction since are bounded at the beginning of the stretch of time that they evoke but not at the end, therefore allowing both the impression of present result or that of continuation up to the present. However, this resemblance does not account for the fact that a beginning and end-bounded verb form such as the Simple Past is more likely to be found in temporal since-clauses. Why is the Present Perfect allowed in some cases in this context, but not in others? There must be a reason for the use of the Present Perfect in these clauses, and that is what this study attempts to explain.

Chapter 1 Theoretical Framework

1.1 Literature Review

1.1.1 The Conjunction since

The word since can function in the English language as an adverb, a conjunction, and a preposition. The Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary provides the following definitions, respectively (2012: 1163):

1) from a definite past time until now ˂ has stayed there ever ̴ ˃

2) at a time in the past after or later than ˂ has held two jobs ̴ he graduated ˃ : from the time in the past when ˂ ever ̴ I was a child ˃

3) in the period after a specified time in the past: from a specified time in the past These three different uses of since all have one notion in common: they involve a definite time in the past. The Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English For Advanced Learners (2009) merges the three functions of adverb, conjunction and preposition to propose a single concise definition (p. 1636):

[generally used with a perfect tense in the main clause] from a particular time or event in the past until the present, or in that period of time

It also incorporates the difference in use between since and for in a small grammar rubric (ibid.):

Use since to say that something started at a point in time in the past, and is or was still continuing: He has been living in Leeds since 1998. | We’ve known about

it since May.

Use for when you state the length of time that something has been or had been happening: We have known each other for ten years (NOT since ten years).

Another reference grammar, Swan’s (2005) Practical English Usage describes since’s usage similarly, comparing it with for and from (pp. 184-185). Since defines an event as starting at some point in time in the past and continuing up to the present.

As Moens (1987) defines it, since describes an up-to-now event, delimiting the beginning of a stretch of time during which some event occurs and having the present

moment (present of speech) as its final point. Other authors have called since an adverb of “time past” (Kerl 1861: 31), of “indefinite time” (Rastall 1999: 80), or as marking the “durational starting-point” of a situation (Huddleston & Pullum 2002: 702). What all authors agree on is that since is a time-word delimiting the temporal boundaries of an event or situation.

Because of the specific point in time it expresses, the since-clause is understood to allow only a Simple Past verb form. As Leech (2004) puts it, “the Past Tense, indicating a definite point of reference in the past, is to be expected in temporal clauses introduced by

when, while, since, etc., because the time specified in such clauses is normally assumed to be

already given” (p. 43). What most authors seem to have missed is that there is a significant number of instances of another verb form in the since-clause: the Present Perfect. This form is generally only noted to occur in the main clause to which the since-clause is related, as a compulsory reflex of the since-clause, which situates the event of the main clause in a time stretch starting in the past but continuing up to the present of speech (Bauer 1970, Comrie 1976, McCoard 1978, Quirk et al. 1985, Huddleston & Pullum 2002, Binnick 2006, Reed 2012, Yao 2014).

As with authors mentioned above, in Palmer’s (1988) The English Verb, only the verb tense or inflection of the main clause used in conjunction with a since-clause is discussed:

In addition to the adverbials used with tense, there are some that are specifically associated with the perfect. These are the adverbial clauses and phrases beginning with since (since Tuesday,

since we met). They indicate the starting point of the period of time. Adverbials beginning with since are used only with perfect forms, except, rarely, with progressive forms used for limited

duration:

I’ve been reading since three o’clock. I’d been reading since three o’clock. (p. 47)

However, once again, the verb tense or inflection involved inside the since-clause itself is not discussed, despite the fact that there are numerous instances of the Present Perfect in this temporal clause, not only of the Simple Past.

Only a few authors (Swan 2005, Algeo 2006, Hundt & Smith 2009) mention that

since allows for a Present Perfect in its environment. However, they do not specify under

what conditions the verb form in question is used in that environment. Although Swan observes that the Present Perfect can be used instead of the Simple Past in the since-clause, he does not characterize any difference in meaning between the two forms (p. 513):

(18) I’ve known her since we were at school together. I’ve known her since I’ve lived in this street.

You’ve drunk about ten cups of tea since you arrived.

You’ve drunk about ten cups of tea since you’ve been sitting here. We visit my parents every week since we bought the car.

We visit my parents every week since we’ve had the car.

In this respect, Close (1992) goes a bit further with his observation that the Present Perfect is acceptable in a since-clause if the event expressed can continue or extend in time up until now (p. 73):

(19) Since he was in the army, he has been in much better health. Since he has been in the army, we have seen him only twice.

In the first example, the subject is no longer in the army, which is why the Simple Past is used: it describes a state that ended before the present. In contrast, the second example entails that the subject is still in the army at the moment of speaking: the event started in the past but is still continuing up to the present moment. As we shall see later on when analyzing the corpora results of the present study, the use of the Present Perfect in since-clauses is not restricted to state-like events like those shown above. As a matter of fact, we found instances of the Present Perfect in since-clauses with all types of events; punctual, continuative, dynamic, static, bounded, unbounded, etc.

Werner (2014) remarks that since is part of a group of adverbials that act in a more or less neutral way, allowing the possibility of both the Simple Past and the Present Perfect. The only difference between them is dialectal: the British variety of English tends to use the latter more, while American English uses the Simple Past more or at least as much as the Present Perfect (pp. 337-338). This claim will be verified in our corpus study, which will examine data from both the BNC and COCA databases, to see if there are indeed any dialectal differences in usage.

Quirk et al.’s (1985) definition and description of temporal since is the most complete of all definitions given of this lexical item. They describe it as a word used for “adjuncts of backward span” (p. 536), as well as “specify[ing] a span of time [and] mark[ing] in addition the starting point” (p. 537), as opposed to for-adjuncts, which do not specify a starting point.

They also mention that the Present or Past Perfect is favored in the main clause because of the past punctuality expressed by the since-clause, which depicts either a “continuous state or activity” or a “period within which one or more discrete actions took place” (p. 538). Moreover, they stand out from most authors in stating that there is a possibility of finding a Present Perfect inside the since-clause, as illustrated by the following example (p. 538)

(20) Since they have lived in London, they have been increasingly happy. [= ‘during

that time’]

showing that the event of living in London is still true in the present, as opposed to

(21) Since they went to live in London, they have been increasingly happy. [= ‘from

that point in time’] (ibid.)

which focuses not on the living in London itself, but on the moment they moved to the city. They further differentiate the Past and Perfect with a third example, in which the event of living in London is not true anymore in the present:

(22) Since they lived in London, they have been increasingly happy. (ibid.)

Furthermore, they mention that verbs like live define a continuous activity or situation, but verbs like join define a punctual activity, therefore the reading “being true at the present” is not applicable in that context:

(23) He’s been getting bad headaches since he joined the army. (ibid.)

In the last example, there is no explicit or implicit proof that he is or is not in the army at the moment of speaking. When it comes to differentiating the Present Perfect from the Simple Past inside the since-clause, they state:

When the whole construction refers to a stretch of time up to (and potentially including) the present, the general rule for the temporal since-clause is that the simple past is used when the clause refers to a point of time marking the beginning of the situation referred to in the matrix clause and the present perfective is used when the clause refers to a period of time lasting to the

present (p. 1017).

On the very next page, however, they mention that sometimes, the Present Perfect can be used in a since-clause denoting an event which took place at a precise point of time, with a case in which, based on the rule given above, one would expect the Simple Past tense (p. 1018):

1.1.2 Present Perfect

According to Swan (2005), the Present Perfect is used to talk about past events that are connected to the present and its use is relevant only if the situation requires us to talk about the past and the present at the same time (p. 440). Quirk et al. (1985) contest the claim that the Present Perfect is used when the event is “past with current relevance” and maintain rather that it is used in three different ways. The first is what they call “state leading up to the present” as in That house has been empty for ages. The other two uses are “indefinite event in a period leading up to the present” as in Have you (ever) been to Florence? and “habit (i.e. recurrent event) in a period leading up to the present,” as in Mr Terry has sung in this choir

ever since he was a boy (p. 192).

Other authors classify the Present Perfect into four different uses: “stative perfect”, “experiential perfect”, “perfect of persistent situation”, and “perfect of recent past” (McCawley 1971, Comrie 1976, Dahl 1985):

(25) John has arrived1.

Bill has been to America. We’ve lived here for ten years.

I have recently learned that the match is to be postponed.

In all cases, the Present Perfect differs from the Simple Past in that the former has some present result or relevance while the latter denotes events that occurred and ended in the past with no evocation of the present result of the occurrence.

1.1.3 Tense and Aspect

Most linguists believe that verbal aspects can be divided into binary oppositions such as perfective/imperfective (Moens 1987), simple/progressive (Bauer 1970), or perfect/progressive (Leech 2004). According to the influential treatment proposed by Comrie (1976), the basic function of aspect is to describe the temporal profile of an event: he defines aspect as the way the event is portrayed with regards to its whole or parts, i.e. the internal temporal constituency of an event. The perfective aspect represents a whole situation without

1 Comrie uses the term “perfect of result” instead of “stative perfect”, but both are the same in that they express

a past situation which has a present result in the form of a state, i.e. the result of John arriving is the state of John being here.

any mention of how it unfolds, changes or varies from phase to phase, whereas the imperfective aspect views the situation from within, with all its parts, phases, and changes (p. 16).

Based on the fact that there are only two indicative-mood morphological forms of the verb in English (look/looked), the future being a verb phrase composed of the modal auxiliary

will and the bare infinitive, Hirtle (2007) argues that there are only two tenses in the indicative

in English, the past and the nonpast, the latter involving all other times than the past. The nonpast thus includes the present and the future, an analysis which accounts for the fact that the Simple Present inflection can be used to express future events:

(26) The bus arrives at the bus stop at 2:05.

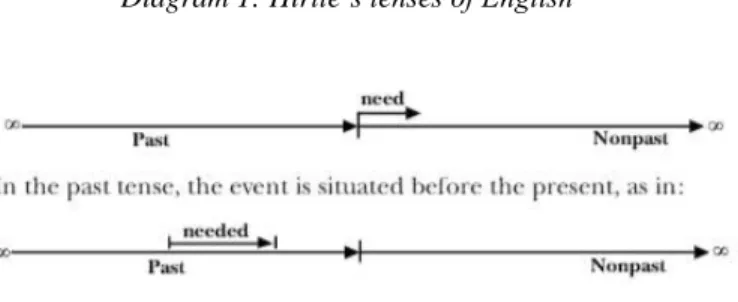

Hirtle’s view of English tenses can be illustrated by the following diagram (2007: 58):

Similarly, there are only two aspects: the immanent aspect (e.g. look), which has to do with the interiority of an event, and the transcendent aspect (e.g. have looked), which denotes the aftermath or result phase of an event. The have + participle construction cannot be regarded as a tense because it can express not only a past event but a future one as well:

(27) She has left the building.

She had left the building when the cops arrived.

She will have left the building when the cops (will) arrive.

Since it cannot be restricted to a single time sphere, the English Perfect cannot be considered a tense. Based on the form of the conjugated verb, he argues that the Present Perfect is not a past tense, but rather nonpast. Furthermore, since the Present Perfect implies a result, Hirtle analyzes it as a transcendent aspect. In sum, Hirtle does not classify the Present Perfect construction either as a tense or an aspect but as a combination of these two categories, which

he calls the “nonpast transcendent” (p. 232). Hirtle argues that the Present Perfect denotes the past participle’s result phase as persisting in the present, as illustrated by the contrast between the two sentences below:

(28) I lost my keys. I have lost my keys.

Whereas the first sentence could be used to describe an unlucky incident that happened 10 years ago, the second denotes the result phase of the losing as currently existing, which represents the keys as still being lost. Hirtle thus analyzes the Present Perfect as “a transcendent verb in the nonpast” (p. 225) in which the auxiliary have “relates its span of duration to the present” (p. 223). The past participle denotes an event as seen from the viewpoint immediately after its final moment. The combination of the two forms represents the subject of the auxiliary as being in the result phase of the event expressed by the past participle.

1.2 Types of Predicates

Vendler’s (1957) Verbs and Times categorizes verbs into four broad classes according to their aspectuality: states, activities, achievements, and accomplishments. His framework has been the foundation of numerous – if not all – subsequent analyses and research on the aspectuality of verbal predicates. Other scholars have fleshed out Vendler’s classification in greater detail so as to cover more types of verbs and predicates (Quirk et al. 1985, Xiao & McEnery 2005, Croft 2012).

Croft (2012) proposes the most elaborate aspectual classification system, distinguishing seven more types of predicates, on the basis of the claim that Vendler’s categorization is too vague and causes problems for the classification of certain verbs.

The first type of predicate presented by Vendler is the category of states, characterized as being non-dynamic, durative (not punctual), and unbounded. Dahl (1985) holds that states are unbounded and that only dynamic events have the possibility of being bounded. Croft (2012) argues that the category of states should be divided into the subcategories of inherent permanent, acquired permanent, transitory, and point states – the latter allowing punctuality

in spite of Vendler’s claim that all states are necessarily durative (p. 36). Here are some examples from Croft (2012):

(29) Inherent permanent: “She is French”

Acquired permanent: “The window is shattered” Transitory: “The door is open”

Point: “The sun is at its zenith”

The second class of predicate in Vendler’s schema is activities. The following examples represent activities in Vendler’s terms, i.e. events that involve change but no endpoint.

(30) So it’s been almost a year since she’s surfed. (ACT 118)2

(31) We’ll see how it works, it’s been a long time since I’ve played. (=play sports) (ACT 80)

(32) If it’s been a while since you’ve exercised, start by walking 20 minutes a day, three times a week. Once you feel comfortable with this, add a bit of running. (ACT 39)

According to Vendler’s analysis, activities are dynamic (they involve change), durative, as well as unbounded (they do not have a specific endpoint). For Freed (1979), activities are initially bounded, which means that although the event does not have an endpoint, it has a clear beginning. For example, the activity sing in The choir sang does not involve a final state where The choir stopped singing is true, but there is an explicit change from the initial state, where there was no singing, to the beginning of the event expressed by the activity verb. Other authors hold that not all activities are unbounded and that some of them allow for an endpoint. As Radden and Dirven (2007: 180-181) argue, activity predicates are atelic – there is no result as a consequence of the actualization of the event – but they can be bounded as in Ann cuddled the baby, or unbounded as in Ann is cuddling the baby. In the first example, the event occurred in the past, therefore there was an end to the cuddling of the baby, whereas in the second example, the progressive form of the present tense implies that the activity is not over yet, hence not implying any end to the cuddling.

2 Examples taken from the present study’s corpus data are identified in parentheses with the category’s

abbreviation, followed by the context number, which corresponds to the number found in the corresponding appendix.

According to Croft (2012), on the other hand, activities are unbounded but can be either directed or undirected. He argues that the event cool in The soup cooled is a directed unbounded activity involving an ongoing change from an initial state to the end of the event. Although Croft claims that directed activities do not involve a result state, it is hard to see how soup cooling does not lead to the result of the soup not being warm anymore. For undirected activities, Croft uses the example The girls chanted, in which the verb chant expresses a process, but not a continuous or linear one leading in some direction, but rather merely “a repeated emission of certain types of sounds” (2012: 40). Thus one can say that undirected activities are perceived as a series of events grouped together. This characterization resembles that proposed by Levin and Rappaport Hovav (2002) of a complex

event: it describes the “internal temporal constitution” of an event as comprising subevents

that can be temporally dependent from one another (p. 9). In fact, Levin and Rappaport Hovav argue that although the notion of complex event is often associated with the notions of accomplishment or telicity, this association is mistaken; a complex event is an event constructed from many subevents that occur one after the other, but any subevent can be taken as representation of the whole event. For example, in The girls chanted, the event is comprised of many subevents during each of which the girls were chanting. Therefore, one instance of the event represents the entirety of it as well. As they also observe, a complex event does not have to be bounded, which means that activities can be treated as complex events. Similarly, if a telic event is one which involves a final result – therefore, a change of state – then activities can be understood to be complex events, bounded or not (depending on one’s point of view), which are atelic.

Croft (2012) argues that activities can either have an endpoint or not, so they should be divided into directed activities (those having an endpoint) and undirected activities (those with no endpoint, as in the case of Vendler’s activities). A first problem with Croft’s subcategorization of activities arises here. If activities can have an endpoint, but yet are dynamic and durative, then what differentiates them from accomplishment predicates? In fact, according to both Vendler and Croft, accomplishments are durative events that entail change and have an endpoint. Croft believes that directed activities are predicates that in other cases could be undirected. For example, the predicate ran a mile in She ran a mile is a directed activity, not an accomplishment, according to Croft, because the verb run is an

activity verb and is usually used to express an undirected event, as in She ran this morning. However, this entails that Croft’s aspectual classes are not based on the actual use of the verbal predicate in the sentence being analyzed, but rather on the most frequent use of the verb. This opens the door to confusion, as there is no way of knowing what other uses of the item being analyzed are being covertly invoked to determine how the verb is classified. This raises the whole problem of determining what is the most frequent or prototypical use of the verb, a task which seems practically impossible to carry out.

The third category distinguished by Vendler (1957) is accomplishments, which express events that are dynamic and durative, but, unlike activities, bounded. Hence, they involve both a result state and an endpoint.

(33) You think about your old lists; it’s been months since you’ve written a new

goal. (ACC 76)

(34) Since I have installed it, I have not had a Windows failure using DOS,

Windows or Windows 95 software. (ACC 43)

Croft (2012) regards accomplishments as dynamic, durational events that involve an endpoint. The only thing separating directed activities from accomplishments, according to Croft, is that the latter involve incremental (ongoing) change, whereas the former do not. Moreover, as mentioned above, directed activities are events that otherwise would be undirected activities, therefore accomplishments include events that would not be categorized as activities in other contexts. He bases his analysis on the idea conveyed by the verb out of context and not in relation with the context in which it is used. This leads to confusion in the differentiation of directed activities from accomplishments as discussed above. He assumes the verb to have an intrinsic aspect or “potential”, as he calls it, to represent a certain type of aspectual construal. Thus, since the verb be most frequently denotes a state, this would entail that it should be classified as a directed state in a use such as The baby was sick all over her new dress, in which it most clearly denotes an action.

The fourth Vendlerian aspectual category is achievements, which are events that are dynamic and bounded, like accomplishments, but, unlike accomplishments and activities, punctual, i.e. non durative. Vendler’s achievements are represented in the following examples:

(35) These are states that are hurting. In the two states where the president is today, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, each state has lost somewhere in the range of 160,000 manufacturing jobs since the president has taken office. (ACH 176)

(36) I should have recognised him, but it’s a while since I’ve seen his picture. (ACH 146)

Croft proposes a subdivision of this category into four types: reversible, irreversible, cyclic (or semelfactive), and runup. All of these four types of achievement are dynamic, punctual, and bounded. What differentiates cyclic achievements from reversible and irreversible ones is the idea of change: “authentic” achievements involve a change from an initial state to a final, resultant state, caused by the actualization of the event, but cyclic achievements imply that the initial state is returned to after the actualization of the event. Although there is no change when cyclic achievements are involved, there are still the features of punctuality and boundedness that connect them to the other two “original achievements”. As far as Croft’s category of runup achievements is concerned, they are in fact accomplishments rather than achievements. Croft argues that the process of change that they involve is “incremental”, as opposed to ongoing. However, the defining characteristic of Vendlerian achievements is punctualness, and runup achievements are clearly durative. The fact that there is a process leading to a result and a change of state indicates that they are better classified under accomplishments.

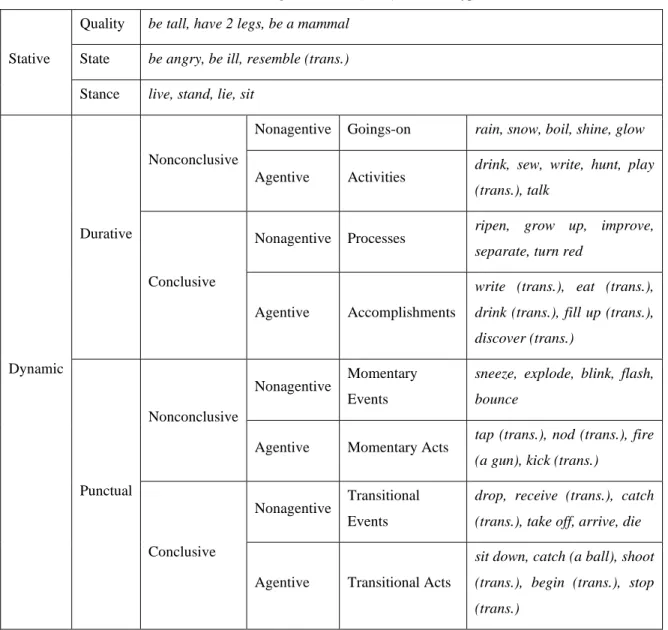

Quirk et al. (1985) classify verbs into what they call “situation types”. The major binary distinction is that between stative and dynamic situations. Both categories are further subdivided to cover a total of 11 different types of situations. Table 2 summarizes these categories.

States are divided in terms of whether they express qualities, states of mind, or physical posture, without any mention of their relation to time. As for dynamic situations, they are divided into those that take time and those that are punctual, those that are agentive and those that are not, as well as subtypes that involve a result or completion and those that do not involve these notions. Activities are therefore dynamic, durative situations that do not involve a result phase and that have an agent. The same logic is applied to accomplishments,

which are treated as separate from processes because they need to have an agent to be considered accomplishments. Achievements are not part of Quirk et al.’s classification, but they would correspond to the whole category of dynamic punctual situations, i.e. to momentary events and acts, and transitional events and acts combined. Quirk et al.’s classification has little to do with the event’s internal temporal profile and much to do with whether the verb has an agent or not.

Table 2: Quirk et al.’s (1985) situation types3

Stative

Quality be tall, have 2 legs, be a mammal

State be angry, be ill, resemble (trans.)

Stance live, stand, lie, sit

Dynamic

Durative

Nonconclusive

Nonagentive Goings-on rain, snow, boil, shine, glow

Agentive Activities drink, sew, write, hunt, play

(trans.), talk

Conclusive

Nonagentive Processes ripen, grow up, improve,

separate, turn red

Agentive Accomplishments

write (trans.), eat (trans.), drink (trans.), fill up (trans.), discover (trans.)

Punctual

Nonconclusive

Nonagentive Momentary Events

sneeze, explode, blink, flash, bounce

Agentive Momentary Acts tap (trans.), nod (trans.), fire

(a gun), kick (trans.)

Conclusive

Nonagentive Transitional Events

drop, receive (trans.), catch (trans.), take off, arrive, die

Agentive Transitional Acts

sit down, catch (a ball), shoot (trans.), begin (trans.), stop (trans.)

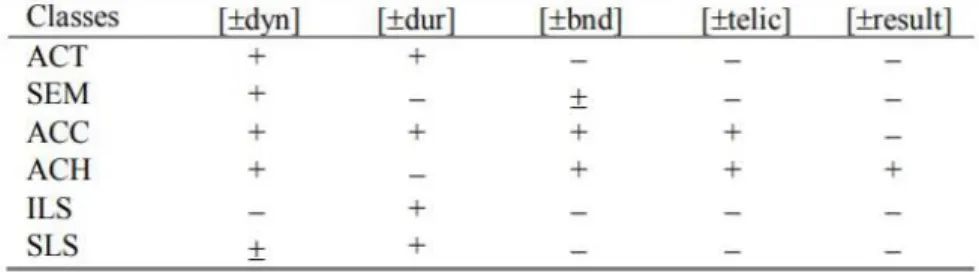

In their paper “Situation aspect: a two-level approach”, Xiao and McEnery (2005: 185-200) identify six different types of verbs. They consist of Vendler’s four categories of activities, accomplishments, achievements, and states, with the category of semelfactives being added and states being divided into “individual-level” and “stage-level” (p. 189). The authors use five features to classify verbs into the different categories, namely dynamism, duration, telicity, boundedness, and result:

Table 3: Xiao & McEnery’s feature matrix system of verb classes

This feature system is malleable in that it changes according to the contexts in which the verb is used along with other sentence elements. For example, the above table shows that individual-level states are unbounded, but in sentences like He was chairman from ’81 to ’85 the prepositional phrase from… to transforms the verb into a bounded situation. The same goes for stage-level states and accomplishments followed by for… to prepositional clauses as in They were silent for a while and Having practiced for a whole year, Yang was soon to

finish his apprenticeship, where the prepositional clause in both sentences bounds the

usually-unbounded event (Xiao & McEnery 2005).

In the present study, we will use a combination of Vendler’s (1957) four-way classification and Croft’s (2012) 11 categories. States will be divided into the four subtypes provided by Croft (inherent permanent, acquired permanent, transitory, and point), and achievements will be separated into reversible, irreversible, and semelfactive to see if there is any kind of correlation between these subtypes and the use of the Present Perfect.

As will become evident, some contexts in the present study could be interpreted differently and fall under different categories of predicates since these categories are

theoretical ways to classify language. Therefore, depending on one’s view of a situation, in a context such as

(37) Dame Elizabeth Taylor, the silver screen legend herself. It has been three years since she's done a major interview. It was right here three years ago. She'll be on with us in about 12 minutes. (ACT 13)

one could see the event of doing interviews as having an endpoint because interviews normally have natural endpoints and therefore classify this use in the category of accomplishments, or as simply engaging in the activity of doing interviews, in which case it would be classified as an activity. The latter is the view adopted in the present study.

1.3 Hirtle’s analysis of the Present Perfect

For Hirtle (2007), the Present Perfect is a compound form involving the nonpast tense and the transcendent aspect. Instead of dividing the Present Perfect into different uses, such as “stative perfect”, “perfect of present relevance”, etc., Hirtle (1975b) claims that all these uses of this verbal construction have one point in common, that is “the present of speech being seen in the event’s aftermath, whatever the subject can actualize in this moment is felt to be in some way conditioned by the preceding event” (p. 65). This is a more accurate description of the Present Perfect because it accounts for contexts such as the negation in I

haven’t read the book, in which there is no reading, but there still is a present “result” of not

knowing what the book is about so the subject is in a present situation of not having read the book, which was brought by the transcendence of the non-reading of the book.

As noted above, no one has ever investigated the use of the Present Perfect in since-clauses of the type illustrated in It’s been a long time since you’ve spoken to him. As already noted also, what is striking about this type of clause is that it should normally be constructed with a Simple Past, because it describes a past event that ended before the present moment, which corresponds to the meaning of since, which denotes a punctual moment in the past. However, as mentioned earlier, since does not only denote a point in the past, but represents this point as the start of a stretch of time leading up to some other reference point, usually the present. In this sense, it aligns semantically with the aspectuality of the Present Perfect,

which can sometimes evoke an event that started in the past but occupies a stretch of time leading up to the present, as in I’ve waited for this for a long time.

Chapter 2 Research Method

Methodology and Hypotheses

As the research question being investigated in this study is “what are the different types of verbs and predicates allowing the Present Perfect in temporal since-clauses”, this research is designed as a descriptive study based on an empirically grounded theory. In order to test the hypotheses proposed by the theory, web corpora have been used for data collection because they represent data from contemporary usage and allow access to the actual contexts in which language users produced the sequences under study here, in genres ranging from written academic texts to informal spoken interview transcripts; the only genres not included in the corpora used for this study are ordinary conversations not recorded such as ones among friends and family and everyday encounters in general. Accessed through the Brigham Young University (BYU) website, both the British National Corpus (BNC) and the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) were used in order to allow the possibility of investigating dialectal differences, if applicable, with respect to the use of the Present Perfect with the different types of predicates in temporal since-clauses.

Corpus research is required in order to verify the study’s hypotheses regarding the use of the Present Perfect in since-clauses, which are as follows:

i. Accomplishment and achievement predicates allow the Simple Past to be substituted for the Present Perfect in since-clauses in most cases;

ii. Activity and state predicates allow the Simple Past to be substituted for the Present Perfect in some cases, but there is a proclivity towards the use of the Present Perfect; iii. British English uses the Present Perfect more than the Simple Past in since-clauses. In addition to verifying these hypotheses, the corpora used here can help provide a larger and more accurate sample for data analysis than a corpus created by personally collecting examples from one-on-one interviews and conversations or from collecting data from different websites, journals, literature, etc. for the following reasons:

i. The variety of formal and informal texts from BNC and COCA databases cover a larger set of language use than data that could be collected in a personal corpus;

ii. The examples collected from BNC and COCA come mainly from native English speakers4, who are difficult to access in a French-speaking environment such as the author’s;

iii. BNC and COCA include instances from a large range of years, not simply of the last two or three years, which would have been the maximum range for informal oral data if it were to have been collected by the present researcher;

iv. Finally, the fact that the corpora are gathered in one database allows an accurate and exhaustive representation of overall language use by providing all instances of a specific syntactic construction, which would not be possible by collecting one’s own examples from different online, paper, and oral sources.

When it comes to methods of analysis, there are two ways of analyzing the data from corpus research: Glaser’s (1978) method is comprised of two phases, substantive coding and theoretical coding, while Strauss and Corbin’s (1990) method consists of three phases, open coding, axial coding, and selective coding (in Fortin & Gagnon 2015). The present research will use the three phases of Strauss and Corbin’s approach. The first phase, open coding, consists of dividing the corpus data into the different predicate categories of accomplishments, achievements, activities, and states based on Vendler’s (1957) classification. Then, the axial coding phase involves dividing certain categories of the previous phase into subcategories, which is the case for states and achievements. Glaser’s approach does not account for this phase, and proceeds directly from the categorization of the open coding phase (Glaser’s substantive coding) to the final phase of theoretical coding, which Strauss and Corbin call selective coding. This last phase of selective coding brings out the relations between categories regarding why or how they allow or not the Simple Past substitution. Moreover, the ongoing comparison and analysis of the data collecting process led to the modification of certain categories. In fact, at first Croft’s (2012) 11 aspectual categories were used to classify the examples, but the impracticability of making certain distinctions between certain of these categories led to a return to Vendler’s (1957) four-way classification, keeping only certain of Croft’s subcategories; states were subdivided into inherent permanent, acquired permanent, transitory and point, while achievements were

4 Even if some contexts are from non-native speakers of English, it is still an accurate representation of

subdivided into reversible, irreversible and semelfactive. Once the classification of the verbal predicates found in the corpus was done, all the examples were divided into those in which the Present Perfect could be substituted by the Simple Past and those in which it could not.5 In summary, including subcategories, there are nine types of predicates, each of them is divided into whether or not it allows the Simple Past substitution for the Present Perfect without altering the intended message.

5 For the purpose of this study and from intuition and knowledge of both a native speaker and a non-native

speaker of English, classifying an example as not allowing the use of the Simple Past can mean one of two things: either the sequence would not make sense (e.g. *I am happy since I was in the Navy) or the message expressed would be substantially altered (e.g. I’ve felt better since I’ve been in the hospital vs I’ve felt better

Chapter 3 Data Analysis

3.1 Events and Durations

Events were divided in the four categories of accomplishments, achievements, activities, and states according to their duration, dynamism, and boundedness. The interaction of the duration of events with different types of duration components in the syntax of the sentence can influence the perception of the message intended. For example, in the two sentences below, the first of which involves an accomplishment and the second an achievement:

(38) And yet it’s been 10 years since we’ve had an honest conversation about

racial profiling in this country. (ACC 33)

(39) It is three years since I’ve scored for England and I’m well aware that the two I scored against Czechoslovakia remain my only goals. (ACH 129)

the parameters of the two contexts are similar: definite durations of a few years and specific events. The effect of substituting the Present Perfect for the Simple Past is also similar. In the first example, in which the event expressed is an accomplishment, the use of the Simple Past gives the impression of going back to the last time they had an honest conversation about racial profiling in the US, as can be seen from:

(38’) And yet it’s been 10 years since we had an honest conversation about racial

profiling in this country.

The original context with the Present Perfect entails that the subjects have not had an honest conversation about the topic for the past 10 years. The Present Perfect thus brings the durational aspect to the fore, while the Simple Past hearkens back to the last time they had an honest conversation. Achievement predicates like the one in (39) above, involve a similar contrast:

(39’) It is three years since I scored for England and […].

The major difference between (39) and (39’) is the interaction between the three-year duration and the verbal inflection. With the Present Perfect in (39), the focus is on the accumulated duration of three years in the result phase of scoring – the speaker has not scored for three years – whereas the use of the Simple Past in (39’) shifts the focus to the last occurrence of the event three years ago.

In the present study, contexts found through corpora search for BNC and COCA were manually separated into the four Vendlerian categories of events. As can be seen in Diagrams 1 and 2 below, the 527 results collected from both corpora are not of equal number. We tried to collect approximately 100 examples for each of the categories, but there were too many examples of achievement predicates the more we were digging into the databases. Therefore, it is to be understood that even if we would have continued our search to find more accomplishment predicates to make it 100 examples, there would have been more and more examples from other categories, notably activities and achievements. For that reason, we stopped at 527 examples in total, deciding that it was enough data to reach an approximate percentage and number of the different categories of predicates of the Present Perfect use in temporal since-clauses.

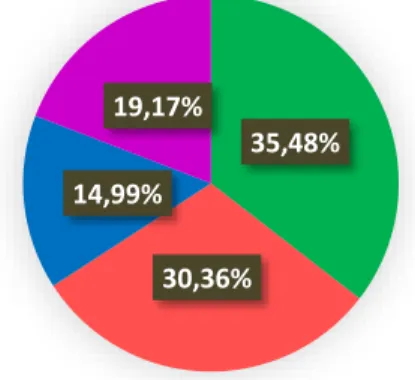

35,48%

30,36% 14,99%

19,17%

Diagram 2: Percentages of examples for each category of events

Achievements Activities Accomplishments States 187 160 79 101

Diagram 3: Number of contexts for each category of events

Achievements Activities Accomplishments States

The following section deals with achievements in the presence of durational elements in their environment, followed by accomplishments, activities, and states.

3.2 Achievements

3.2.1 Definite Durations

Achievement predicates represent 35.48% of all corpus contexts, with 187 contexts out of the 527 total. Predicates of this category allow the Simple Past substitution in the majority of cases – 139 out of the 187 contexts – as in (39) and (39’) above. When they do not, it is because the duration of the non-occurrence of the event is far more salient than the last punctual occurrence of it in the past. This occurs in only three of the 16 contexts with definite durations, shown in (40)-(42) below, leaving a total of 81.25% of the definite duration contexts for achievements to permit the substitution.

(40) It must be a month since you’ve seen her? (SP:PS0RR) Mm, she’s, she pops down when she can. (ACH 140)

(41) Just how much skin matters is a calculus I have tried to work out in the 10 years I have lived in this predominately Mormon state. […] It has been a decade

since I have seen Elle or Self or Cosmo sitting out in plain view. (ACH 138)

(42) Actually, it seems like yesterday. I sit there and I think, ‘OK, well, it’s been 10 years since I’ve been able to talk to her on the phone. It’s been 10 years since

I’ve been able to tell her I love her.’ (ACH 23)

The use of “it must be” in (40) evokes the duration since the last occurrence as indefinite, making it unlikely that the moment in time of the last occurrence is recalled.

(40’) ?It must be a month since you saw her?

Something similar occurs in (41), where the approximate time expression decade and the evocation of different alternatives bring indefiniteness and genericity to the context; the speaker has not seen any magazine of that type in a long time.

The indefinite meaning conveyed by the Present Perfect in (42) emphasizes again the duration of non-occurrence of the event for 10 years rather than going back to a specific moment in the past, but there is something else in that context that does not permit a Simple

Past substitution. The predicate be able to also influences whether the Present Perfect can or cannot be replaced by the other verb inflection. With this phrase, there is a sense of capacity for the subject to perform the event before the time-period expressed in the sentence. For example, in (42), the speaker was able to talk to her before, but in the last 10 years, it has not been possible to do so. To use a Simple Past here would convey the message that there was an exercise of the speaker’s capacity leading them to overcome something potentially preventing the speaker from talking to her and telling her that they loved her on a particular occasion 10 years ago:

(42’) ?[…] OK, well, it’s been 10 years since I was able to talk to her on the phone. It’s been 10 years since I was able to tell her I love her.

However, this is not the intended message of the original context:

Only two contexts with be able to allow the Simple Past substitution without altering the intended message, and the first one involves a definite duration6:

(43) It’s been six months since he’s been able to make a payment. (ACH 24) (43’) It’s been six months since he was able to make a payment.

In this last example, there is no indication of whether the subject was able to make a payment before six months ago, or if there was something preventing him from doing so until six months ago. Hence, the Simple Past can take the place of the Present Perfect without the intended meaning of the message – that the subject has not made a payment in six months – being altered.

6 The other be able to context allowing the substitution will be discussed in the following section on indefinite

durations cf. p. 30 example (48).

able to talk to her not able to talk to her

10 years ago Present

stretch of time since exercise of capacity

10 years ago Present

able to talk to her = exercise of capacity

Apart from the be able to context just mentioned, there are a few other examples of achievement predicates in the since-clause allowing the Simple Past substitution in the presence of a definite duration phrase in the main clause. In fact, out of the 16 contexts of definite duration, 13 of them allow the substitution:

(44) In the two and a half years since Thomas has assumed his post on the

Supreme Court, the underlying assumptions of the conversation I heard as

uniquely outrageous have become commonplace, popularly expressed, and louder in volume. (ACH 18)

(45) It’s been 22 years since the Open has come to the South, and this is only the second occasion (Atlanta Athletic Club in 1976 was the first) it has been conducted southeast of Southern Hills in Tulsa, Oklahoma. (ACH 37)

(46) Voting is the cornerstone of our democracy, yet a month has passed since the

legislature has convened and little has been done to rectify this problem. (ACH

44)

All three contexts express memorable events, yet the Simple Past is usually the form conveying memorable events, not the Present Perfect. Here, the Present Perfect is used to situate all subjects in the result phase or transcendence of the events of assuming a post, coming to the South, and convening, which is not a notion present when the Simple Past is used, even though both verb forms are acceptable for (44)-(46).

In fact, among the 48 achievement predicate contexts rejecting the possibility of substitution, three of them are found with a definite duration in their main clause – (40)-(42) above – and the remaining 45 involve an indefinite duration in the main clause. This means that if there is no expression of duration in the main clause to which the since-clause is adjacent, the Present Perfect can be replaced by the Simple Past without affecting the intended message because there is no durational element putting forward the importance of the length of non-occurrence over that of recalling the last occurrence of the event. This will be discussed in more details in section 3.2.3.

3.2.2 Indefinite Durations

There are 69 examples of achievement predicates in the corpora with indefinite durations. A little more than 30% of these contexts – 24 in total – allow the substitution of the Present Perfect by a Simple Past inflection, as illustrated by the following:

(47) Robert is eager to see you. It has been near three months since he has set

eyes on his beloved sister. (ACH 164)

(47’) Robert is eager to see you. It has been near three months since he set eyes on

his beloved sister.

(48) Aung San Suu Kyi is 63 now, and its[sic] been years since shes[sic] been able

to freely address her followers like this. The generals who seized power in 1988

did nt[sic] tolerate free opposition. (ACH 21)

(48’) […] and it’s been years since she was able to freely address her followers like

this.

The Simple Past substitution in (47’) is possible in this situation because it involves a significant event that can be recalled. When it comes to the predicate be able to as in (48), which is similar to (43) above, the indefinite duration context permits the Simple Past substitution in (48’) because the subject may or may not have had the capacity to freely address her followers before the duration expressed in the context; what the Present Perfect puts forward is the length of time during which she has not been able to do so, while the Simple Past gives a sense of recall of the last occurrence of the event. Some contexts involving be able to do not permit the Simple Past substitution, such as (49) and (50) below, which entail that the speakers had the capacity to talk about it and check their reflection, respectively, before the duration expressed in the contexts. If there was nothing preventing the subject, in the past – before the duration expressed in the sentence – from actualizing the event, then the Present Perfect makes more sense, while the Simple Past would entail that talking about something and checking one’s reflection in a mirror were not doable before – which is almost impossible with such events of everyday situations. In other words, there was nothing preventing the subjects from performing those events in the past:

(49) It’s been a long time since I’ve been able to talk about it. (ACH 22) (49’) * It’s been a long time since I was able to talk about it.