SEMANTIC ANALYSIS OF THE USE OF CLASSIFIERS IN

TAGBANA

Thèse

KIYOFON ANTOINE KONE

Doctorat en linguistique

Philosophiae Doctor (Ph.D.)

Québec, Canada

iii

Résumé

L’examen de la littérature concernant le phénomène des classificateurs dans les langues africaines en général et en particulier dans la langue Tagbana, révèle que l’emploi des classificateurs dans le discours est envisagé sous l’angle d’un accord purement morphologique lié à une perspective syntaxique qui fait abstraction des fondements sémantiques, voire conceptuels qui caractérisent ces emplois. Envisageant, pour notre part, le phénomène sous l’angle des conditions cognitives qui déterminent l’emploi des classificateurs dans le discours, en rapport avec les cadres d’investigations de la psychomécanique et de la grammaire cognitive, il a été démontré dans cette thèse que les classificateurs k, l, m, p, t, et w dénotent une fonction cognitive fondamentale: la structuration du domaine référentiel sur la base de six (06) catégories conceptuelles:

Le concept de l’animé désigné par la forme w; Le concept de l’inanimé désigné par la forme k; Le concept de discontinuité désigné par la forme l; Le concept de d’homogénéité désigné par la forme m;

Le concept du pluriel ayant rapport avec la neutralisation des individualités au profit de

l’ensemble perçu comme un tout désigné par la forme t;

Le concept du pluriel ayant rapport avec la conservation des individualités au sein du

groupe désigné par la forme p. Ces catégories conceptuelles conditionnent et rendent

explicite toute conceptualisation dont est capable le locuteur au regard des données de l’expérience. Dans leur apports conceptuel et sémantique à la définition des référents du discours, les classificateurs expriment le genre et le nombre tels qu’envisagés par le locuteur.

v

Abstract

An examination of the literature on this topic of classifiers in African languages reveals that in general the use of classifiers has been treated as conditioned by a pure morphological process, independent of any semantic and conceptual basis. Viewing the phenomenon from the perspective of the mental conditions underpinning the use of classifiers in discourse, within both the Guillaumean and cognitive grammar frameworks, it has been demonstrated that classifiers have a cognitive function: they structure the experiential domain of Tagbana speaker into six conceptual categories. Investigations into the uses of the classifier k, l, m, p, t, and w in discourse indicate that there are six conceptual categories through which Tagbana speakers view the input from the universe of experience:

The concept of high-scale animacy designated by the classifier w The concept of inanimacy designated by the classifier k

The concept of discontinuity designated by the classifier l The concept of homogeneity designated by the classifier m

The concept of plurality with loss of individuation designated by the classifier t The concept of plurality with maintenance of individuation designated by p

These mental categories allow the speakers’ conceptualizations of any experiential entity. A classifier can be defined, therefore, as a linguistic means which allows and

makes explicit the speaker’s conceptualization of the experiential entity being

vii Contents Résumé ... iii Abstract ... v Contents ... vii Figures ... xiii Abbreviations ... xv Acknowledgements ... xvii 0. Introduction ... 1 0.1 Contextualization ... 1

0.2 Situating the problem ... 2

0.3 Defining the problem ... 5

CHAPTER I: A REVIEW OF THE STATE OF KNOWLEDGE OF THE PHENOMENON ... 15

1.1 Classifier within the grammaticalization theory ... 15

1.1.1 The notion of grammaticalization ... 15

1.1.2 Classifiers and the hypothesis of lack of semantic transparency ... 16

1.2 Classifiers within the “quantitative-gender” approach ... 17

1.2.1 The notion of class within the quantitative-gender approach ... 17

1.2.2 The use of classifiers also denotes a qualitative gender ... 17

1.3. The status of classifiers within the morphosyntactic approach ... 18

1.3.1 Classifiers as typical suffixes of nominal classes ... 18

1.3.2 Other shortcomings of the morphosyntactic approach ... 19

1.4 The reference-tracking approach ... 21

1.4.1 The status of classifiers within the reference-tracking apprach ... 21

1.4.2 The reference-tracking approach as an extension of the morphosyntactic approach ... 21

1.5 The indices-analysis approach ... 22

1.5.1 Classifiers and the identification of the intended referent in discourse.. 23

1.5.2 Classifiers and noun stems indexation ... 23

1.6 The logic semantic approach ... 24

1.6.1 The meaning of words in logic semantic ... 24

1.6.2 Classifiers denote what is common to a set of entities ... 25

1.7 Classifiers and the theory of cognitive models... 26

1.7.1 Classifiers as part of the cognitive apparatus ... 26

1.7.2 The use of classifiers in Tagbana does not directly reflect the structure of external reality ... 27

1.8 The sociolinguistic approach ... 28

1.8.1 Classifiers as a reflex of social stratification ... 28

1.8.2 The use of classifiers in Tagbana reflects the conception of social relation ... 28

1.9 Classifiers within a topological aproach... 29

1.9.1 Classifier within the topological approach: a matter of subjectivity ... 29

1.9.2 Classifiers as forms of langue and not of discours ... 30

1.10 The analysis of classifiers within the pragmatic approach ... 31

viii

1.10.2 The shortcomings of the pragmatic approach ... 32

CHAPTER II: THEORETICAL ORIENTATION AND HYPOTHESES ... 35

2.0 Introduction ... 35

2.1 A dynamic view of language ... 35

2.1.1. Language as a potential ... 36

2.1.1.1 The nature of a concept ... 37

2.1.1.2 The underlying principles guiding concept formation ... 38

2.1.1.3 The function of concepts as entities instituted in tongue ... 40

2.1.1.4 The internal makeup of concepts ... 41

2.1.2 Language as a process of actualization ... 43

2.1.2.1 Viewing language from the point of view of the speaker ... 44

2.1.2.2 Actualization: a mental process of construing meaning ... 45

2.1.3 Language as a result of a process of actualization: discourse ... 47

2.2 Morphemes accompanying classifiers in Tagbana ... 47

2.2.1 The consonantal frame work and the construction of substantive nouns in Tagbana ... 48

2.2.1.1 The notion of substantive noun in Psychomechanics ... 48

2.2.1.2 The consonantal framework and the categorization of lexical bases ... 49

2.2.2 The consonantal framework and the construal of pronominal support in discourse ... 50

2.2.2.1 The concept of pronoun in psychomechanics ... 50

2.2.2.2. The pronominal use of classifiers in discourse ... 51

2.2.3 The vocalic framework and the grounding predication ... 54

2.2.3.1 The relation between the vocalic framework and determiners ... 55

2.2.3.2 The system of articles in the Guillaumian approach ... 55

2.2.3.3 The relation between the definite article and the vowel [-i] in Tagbana ... 57

2.2.3.4 The relation between the indefinite article and the vowel [-a] in Tagbana ... 58

2.2.3.5 The vowel -é and the term «particule explétive» ... 59

2.2.3.6 The vowel -é: an intensifier ... 59

2.4 The underlying hypotheses and objectives of the thesis ... 61

2.4.1 First with respect to the consonantal framework ... 61

2.4.2 Second, with respect to the vocalic framework ... 62

2.4.3 Third, with respect to the status of the classifiers and the vowels ... 62

2.4.4 The objectives of the thesis ... 64

CHAPTER III: METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH ... 65

3.0 Introduction ... 65

3.1 The empirical basis of the study ... 66

3.2 The compilation of the corpus ... 66

3.3 The transcription of the corpus ... 66

3.4 The analysis of the data ... 68

3.5 Some terminological clarifications ... 72

CHAPTER IV: DESCRIPTIONS OF CLASSIFIERS IN TAGBANA ... 77

ix

4.1 Classifiers and number expression ... 78

4.2 Description of the uses the classifier k in Tagbana ... 80

4.2.1 Classifier k: the expression of species ... 81

4.2.1.1 The generic use of the classifier k ... 81

4.2.1.2 The relationship between deverbal nouns and the classifier k ... 81

4.2.2 The classifier k: a superordinate category ... 84

4.2.2.1 The use of the classifier k in superordinate-category references ... 84

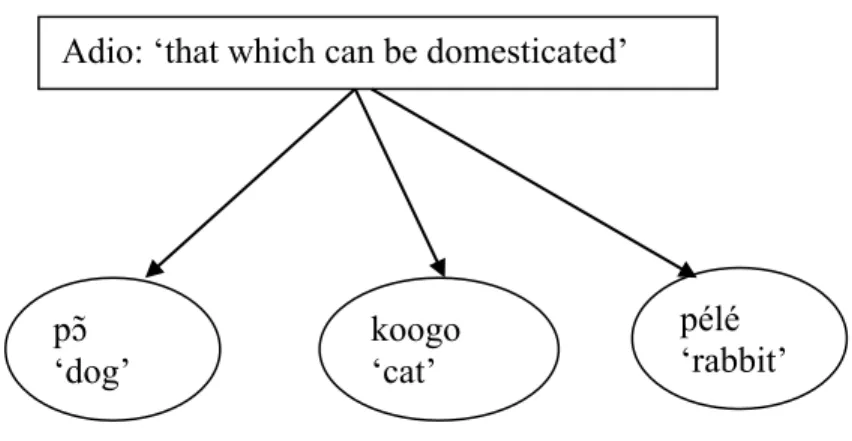

4.2.2.2 k versus w, in referring to domestic animals ... 85

4.2.3 The classifier k and the general notions of thing ... 86

4.2.3.1 The use of the classifier k with the classifier l... 86

4.2.3.2 The use of the classifier k with the classifier m ... 87

4.2.3.3 The use of the classifier k with the classifier t... 88

4.2.3.4 The use of the classifier k with the classifier w ... 89

4.2.3.5 The incompatibility between the classifier k with the classifier p ... 89

4.2.3.6 The use of the classifier k: expert knowledge about “objects of this kind” ... 89

4.2.4 Pronominal use of the classifier k in discourse ... 91

4.2.4.1 The use of the classifier k in initial position: type or sort specification ... 91

4.2.4.2 The use of the classifier k in mass reference: stuff-conceptualization ... 93

4.2.4.3 The unspecified or neuter use of the classifier k ... 94

4.2.4.4 The use of the classifier k with reference to a whole sentence ... 95

4.2.4.5 The use of the classifier k with reference to a group of people ... 99

4.2.4.6 The classifier k used to express an augmentative effect ... 100

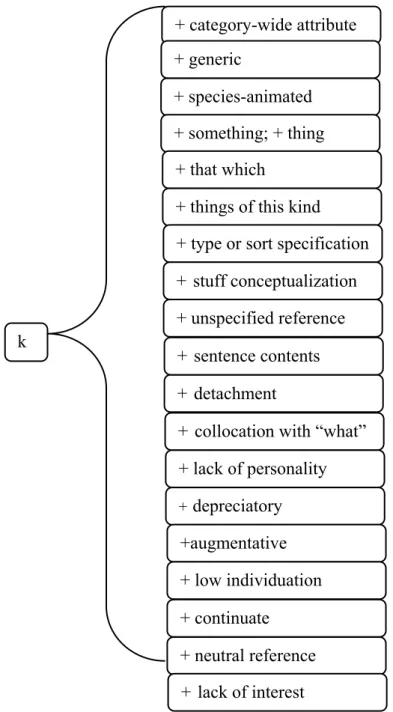

4.2.5 Reconstructing the schematic potential meaning of the classifier k ... 102

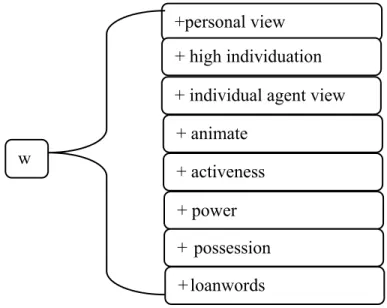

4.3 Description of the uses of the classifier w in Tagbana ... 103

4.3.1 The use of the classifier w with nominal forms construed with lé ... 105

4.3.2 The use of the classifier w with nouns denoting a personal agent’s view ... 107

4.3.3 The use of the classifier w in the structure of nominal forms construed with ascriptive adjectives ... 109

4.3.4 The use of the classifier w with plants perceived as active ... 114

4.3.5 The use of the classifier w with names of infectious diseases ... 114

4.3.6 The use of the classifier w with names of human artefacts ... 115

4.3.7 The use of the classifier w with nouns denoting powerful entities... 116

4.3.8 The use of the classifier w in attributive constructions with possession inference ... 118

4.3.8.1 Possessor nominals exemplifying a relation of ownership ... 118

4.3.8.2 Possessor nominals exemplifying a relation of identification ... 120

4.3.9 The use of the classifier w in talking about domestic animals ... 123

4.3.10 The use of the classifier w with loanwords ... 125

4.3.11 Alternation between classifiers w and k in reference to human beings: the animate vs inanimate view of the referent ... 126

4.3.12 Reconstructing the schematic potential meaning of the classifier w .. 128

x

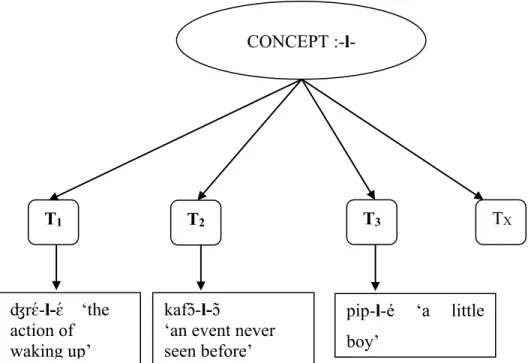

4.4.1 The cognitive function of the classifier l in the construction of the

diminutive suffix plé in Tagbana ... 131

4.4.2 The use of the classifier l with nouns denoting small body parts ... 133

4.4.3 The use of the classifier l with deverbal nouns denoting a transition into and out of a state ... 134

4.4.4 The use of the classifier l with nouns denoting events which stand out from the normal course of situations ... 136

4.4.5 The use of the classifier l with nouns denoting prohibited actions ... 137

4.4.6 The use of the classifier l in expressing the idea of minimum or approximate quantity ... 138

4.4.7 The use of the classifier l with nouns denoting proverb: discontinuity in thought ... 140

4.4.8 The pronominal use l vs. w: marking a discontinuity among human beings ... 144

4.4.9 The classifier l: an evaluative instrument at the disposal of the speaker ... 146

4.4.10 The use of the classifier k: to create an augmentative effect ... 150

4.4.11 Reconstructing the schematic potential meaning of the classifier l .... 151

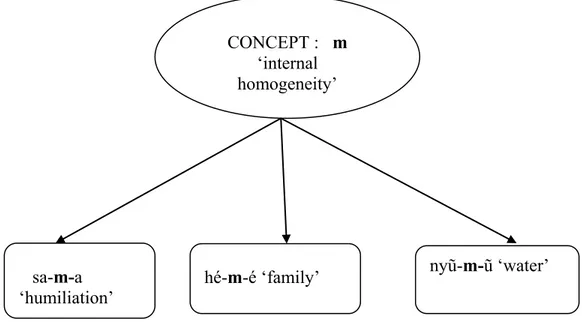

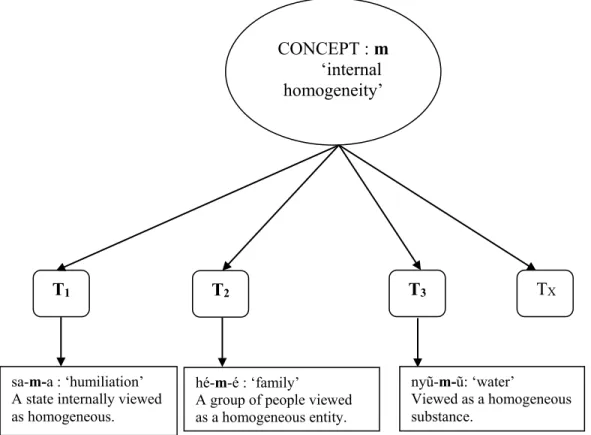

4.5 Description of the uses of the classifier m in Tagbana ... 152

4.5.1 The use of the classifier m in reference to mass nouns ... 155

4.5.2 The use of the classifier m with nouns denoting qualities ... 158

4.5.3 The use of the classifier m with nouns denoting states ... 159

4.5.4 The use of the classifier m in the construction of abstract nouns ... 161

4.5.5 The use of the classifier m with the noun denoting family ... 162

4.5.6 The incompatibility between m-nouns and reduplication ... 164

4.5.7 The use of the classifier m as first person singular pronoun in discourse ... 164

4.5.8 Reconstructing the schematic potential meaning of the classifier m .... 166

4.6 Description of the uses of the classifiers t and p ... 167

4.6.1 Classifiers t versus p ... 167

4.6.1.1 t as the plural form of inanimate entities ... 168

4.6.1.2 p as the plural form of human beings and higher-animate entities 168 4.6.1.3 p as the plural of k ... 169

4.6.2 Description of the uses of the classifier t ... 171

4.6.2.1 r as an allomorph of the classifier t ... 171

4.6.2.2 The use of the classifier t with human bodies ... 171

4.6.2.3 The use of the classifier t with collective nouns ... 173

4.6.2.4 Mutual exclusiveness between t and reduplication ... 174

4.6.2.5 The use of the classifier t with nouns denoting a set of actions or events related to one cause ... 175

4.6.2.6 The use of the classifier t with nouns denoting a series of actions of the same characteristic ... 177

4.6.2.7 The uses of the classifier t with lexical bases denoting states ... 177

4.6.2.8 The use of the classifier t with names of qualities ... 179

4.6.2.9 Reconstructing the schematic potential meaning of the classifier t ... 180

xi

4.6.3 Description of the uses of the classifier p in Tagbana ... 181

4.6.3.1 The use of the classifier p with animate count-nouns ... 182

4.6.3.2 The semantic relation between the phenomenon of reduplication and the use of p ... 184

4.6.3.3 Classifier p versus m ... 186

4.6.3.4 The use of the classifier p as the plural of the category w ... 188

4.6.3.5 The use of the classifier p with nouns denoting ethnic groups... 190

4.6.3.6 The use of the classifier p with collective nouns construed with the prefix a- ... 191

4.6.3.7 Reconstructing the schematic potential meaning of the classifier p ... 192

4.6.4 The micro-system t / p ... 193

CHAPTER V: CONCLUDING REMARKS ... 195

5.1 The traditional views and their limits ... 195

5.2 Classifiers as conceptual categories ... 197

5.3 Classifiers as grammatical categories ... 198

5.4 Classifiers and categories of gender and number ... 201

5.5 Perspectives for future research... 204

5.6 The contribution of the thesis to the domains of syntax and morphology .. 204

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF REFERENCE WORKS CONSULTED ... 207

ANNEX: DATA USED IN THE THESIS WHICH COULD SERVE FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ... 219

xiii

Figures

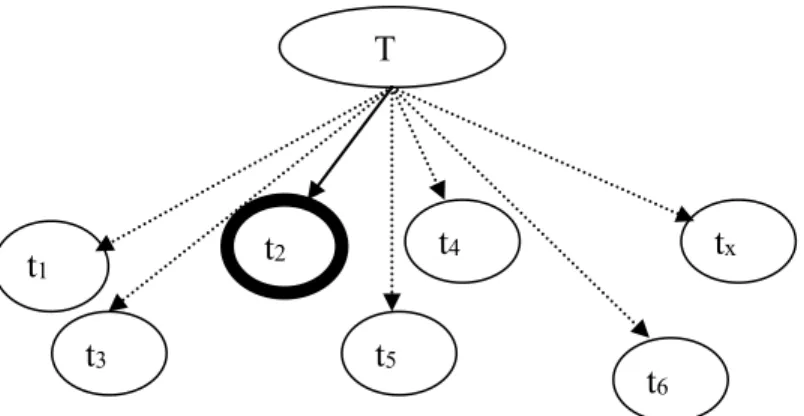

Diagram 1: The unifying view of concepts ... 25

Diagram 2: A schematic characterization the concept RODENT ... 38

Diagram 3 Typical instantiations of the schematic concept denoted by the classifier -m- ... 39

Diagram 4: Actualizations of the characterizing trait of the concept denoted by the classifier m... 42

Diagram 5: Comparing the concept m with the concept l ... 43

Diagram 6: Grounding predication ... 55

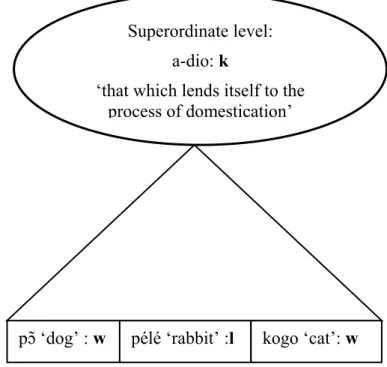

Diagram 7: The superordinate status of the classifier k. ... 85

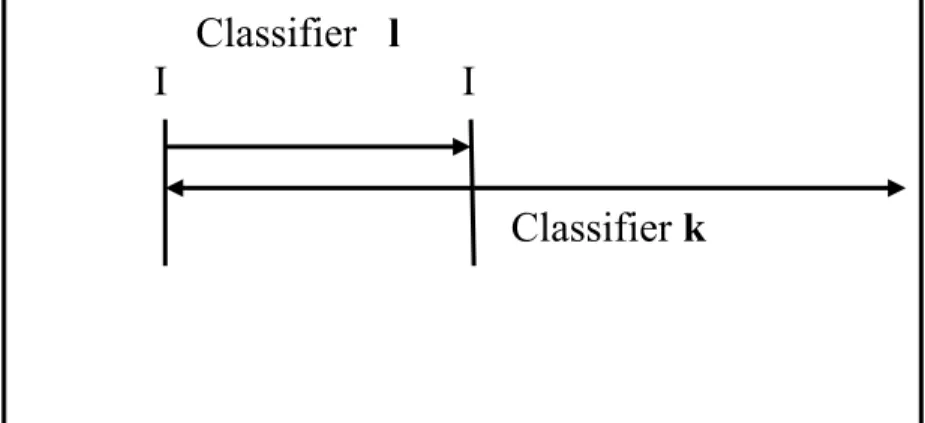

Diagram 8: Contrastive views of the classifiers k and ... 101

Diagram 9: Defining characterizing traits of the classifier k ... 102

Diagram 10: Characterizing traits of the classifier w ... 129

Diagram 11: Marking a transition between two states ... 136

Diagram 12: Image of missing the point during the whole debate ... 148

Diagram 13: Reducing the point missed during the whole debate to a specific and short instant unrelated to the rest ... 149

Diagram 14: Contrastive views of the classifiers k and l ... 150

Diagram 15: Characterizing traits of the classifier l ... 152

Diagram 16: Characterizing traits of the classifier m ... 167

Diagram 17: Impressions produced by classifier t ... 180

Diagram 18: Contrasting views of classifiers m and p ... 188

xv

Abbreviations

CL Classifier

FVLB Final Vowel of the Lexical Base

LB Lexical Base N Noun Neg Negation NP Noun Phrase Perf Perfective Prog Progressive PN Proper Noun Others symbols

[ ] postposed syntactic construct | | related to the structure of the noun

xvii

Acknowledgements

Research for this thesis was partially supported by a one-year grant (2010-11), from the ROTARY FOUNDATION (USA). The thesis’s completion was made possible by the congenial working conditions at Université Laval, and particularly the Fonds Gustave Guillaume. My special thanks go to Patrick Duffley, for his assistance in guiding the thesis through to completion. This study owes much to Gnélinnaha Angèle Touré, for her contribution as informant. Finally, a word of thanks to my family, particularly, Marie Laure Akpa, Prisca Koné, Koné Kouassi, Kiffon Coulibaly, and Eddy Letsoalo whose understanding and encouragement have been a constant help.

1

0. Introduction 0.1 Contextualization

There are six consonants in Tagbana1 whose effect on the message is that some entity is being referred to whenever a Tagbana speaker makes a sentence in a given situation of communication, i.e. k, l, m, p, t, w. These consonants have three basic syntactic positions. First, with a nominal2 , they can be used within the nominal form as an infix. When used as an infix, these consonants occur in the middle of the nominal form:

(1) a a-k-a

‘that which can be used as food’ b prɔ-l-ɔ

‘act of being married’ c prɔ-m-ɔ̃

‘state of being married’ d a-p-uɔ

‘that which can be used to tie’ / ‘clothes’

e déf-w-ɔ ‘landlord’

Secondly, the same consonants can also be used in postposition to the nominal to form a noun phrase (NP).When used in postposition, these six consonants must be connected by one of the following three vowels, a-, é-, i-, whose meaning affects the message conveyed by the NP in terms of the type of reference that the latter denotes:

(2) a a-k-a k-i nyɛ̃ pɛ́rɛ́ ni ‘The food is expensive.’ b a-k-a k-a nyɛ̃ pɛ́rɛ́ ni

‘Some food is expensive.’

1Tagbana is a Gur language spoken in Katiola (the north of Côte D’Ivoire) (cf. Clamens 1952 : 1403; Gaber 1991 : 3; Katia 1988: 10; Gudrun & Kerstin (2007).

2It should be noted that as far as the consonant t- is concerned, it does not occur within the nominal as an

infix; however, it does occur in postposition with nominals having the consonant- r-as an infix. The reason for this difference in phonetic realization will be explained later.

2

Furthermore, when postposed to the nominal form in constituting a NP, it is possible to use more than one classifier with respect to one and the same nominal form.

(3) défɔ-w-ɔ w-é w-i nyɛ̃ lagbãmã ‘This particular landlord is kind.’

These consonants can also be used with the predicate without being in construction with a particular nominal form. In this usage, they must also be syntactically related to one of the vowels -a, -é, or -i, whose meaning concerns the reference of the NP. When used with the predicate, together with the vowels a-, é-, i-, without an antecedent nominal form, these consonants function as pronouns and the entity being referred to can only be determined with respect to a specific situation of communication.

(4) a k-i nyɛ̃ wuɔ

‘It is black’ (talking about a car). b l-i nyɛ̃ tikligi

‘He is intelligent’ (talking about a little boy). c m-i nã hɛ̃ɛ̃ ʧũ

‘It will get you drunk’ (talking about some local beer). d p-i nyɛ̃ wa go ni

‘They are in the house’ (talking about some clothes). e t-i nyɛ̃ tuturu

‘It is not enough’ (talking about some money). f w-i nã pii krɛ́ɛ́

‘He is a teacher’ (talking about a particular man).

The consonants described above are known in the literature as classifiers and the languages whose systems involve this type of phenomenon are termed classifier languages (cf. Garber 1991).

0.2 Situating the problem

The study of the phenomenon of classifiers within most descriptive frameworks has tended to focus on surface forms and not on how these linguistic forms contribute semantically in

3 their different uses, to the expression of the speakers’ conceptualizations of the entities referred to in discourse.

Most of the descriptive approaches share the assumption that classifiers are meaningless units whose function consists in classifying nouns on the basis of morphological criteria. The phenomenon of classifiers is treated in this perspective as mere morphological agreement. According to Clamens (1950:1412) the choice of a classifier is determined in Tagbana by the phonological make-up of the noun.This makes classifiers a mere exponent of grammatical agreement between linguistic forms and not an element which conveys meaning:

The essential features of Niger-Congo classification systems which characterize them as strongly grammaticalized systems are these three: (i) nouns divide into subsets (noun classes) according to their behavior in agreement mechanisms; (ii) the forms involved in these agreement mechanisms (nouns, noun modifiers, pronouns, and verbs) include affixes (class markers) that determine their agreement behavior; (iii) all nouns enter the classification, which is basically a classification of nouns, not of the referents (cf. Grinevald and Seifart 2004: 246).

In the definition mentioned above, classifiers are basically defined as nominal affixes whose function consists in determining the agreement behavior of the nouns they are associated with. In other words, classifiers are viewed as morphological markers which fundamental role consists in the partitioning of nouns into classes on the basis of observable similarities of form. Another definition which shares the same position not only with respect to the morphological criteria, but also with respect to the fact that classifiers are linguistic units that are syntactically bound to the noun they co-occur within a given sentence, is the following:

4

Une langue est reconnue «à classes nominales» quand elle remplit au moins l’une des conditions suivantes : 1) son substantif comporte d’emblée, déjà au stade notionnel, deux constituants de base, un radical et un suffixe, 2) les affixes sont variés et les substantifs sont regroupés par affixe et, enfin 3) l’affixe impose une marque d’accord aux déterminants et / ou des anaphoriques pronominaux du substantif auquel il est associé (cf. Tchagbale 2006: 2).

The authors just above all have in common the following points as far as classifiers are concerned:

- Classifiers are nominal affixes, therefore, syntactically bound units;

- As nominal affixes, the key function of classifiers is to determine on a morphological basis the kind of determiner or anaphoric pronoun a given noun will collocate with on the syntactic level.

- The use of classifiers reflects a purely syntactic phenomenon autonomous from semantics.

The point to be raised here with respect to the assumptions pointed out by these authors is that their description is only based on certain uses of classifiers in Tagbana, i.e. their use as infixes within the nominal form, cf. (1a), (1b), (1c), (1d), (1e) and that as pronouns where the entity referred to is determined with respect to a specific situation of communication, cf. (4a), (4b), (4c), (4d), (4e), (4f). While these uses could perhaps be accounted for by a syntactic agreement operation, some classifiers can be used in Tagbana without being in a relation of morphological agreement to the noun they are associated with. For example, the classifier w, can be used with nouns denoting human beings endowed with some specific

powers; however, these nouns do not show morphological agreement with this classifier.

(5) a lépkɔ w

‘sorcerer’ CL (classifier) b lényã w

‘someone endowed with six senses which allow him to see what an ordinary people does not see’.

5 The same classifier is used with nouns denoting entities which potentially can have a

stimulating effect on the human mind in cases where the form of the noun does not contain

a w for the classifiers to agree with. (6) a gboho w- ‘tabacco’ CL b kori w- ‘cola3’ CL c kafé w- ‘coffee’ CL

These uses of classifiers are said to be the deviant or irregular ones in Tagbana (cf. Gudrun and Kerstin 2007). The reason for this irregularity being that the morphological agreement principle does not apply to them. In fact, it should be pointed out that the morphological criteria in some cases may be overridden by the semantic criteria. Furthermore, the problem with these particular uses does not lie on the level of their irregularity or their being deviant with respect to morphological agreement. Actually, the problem is that the agreement or concord approach to classifiers tries to account for the phenomenon of classifiers on the basis of one syntactic position, i.e. the classifier within the nominal form. What is more, the structural relation between the noun stem and the classifier used as infix within the nominal form is viewed as a static or ready-made relation (cf. Tchagbale 2006; Grinevald and Seifart 2004). The dynamic conditions under which this relation emerges have been overlooked.

0.3 Defining the problem

The phenomenon of classifiers needs to be situated in its natural context, i.e. the relation between language and thought, in the sense that classifiers as linguistic means represent the conceptual categories instituted in Tagbana in terms of which Tagbana speakers apprehend and understand the world they have got an experience of. More precisely, they allow and make explicit Tagbana speakers’ conceptualizations of any experiential entity they wish to

3Tropical African evergreen plants (Cola acuminata or C. nitida) having reddish fragrant nutlike seeds

yielding an extract that contains caffeine and theobromine and is used in carbonated beverages and pharmaceuticals.

6

talk about in discourse. The use of the classifiers in (1), (2), (3) and (4), highlights the need for the characterization of the referents4 of NPs as conceptualized by the speaker. More precisely the use of the classifiers k, l, m, p, t, and w in discourse in Tagbana is meant to indicate the kind of entity which the intended referent is seen to belong to. Viewed in this sense, a parallel can be drawn between classifiers and gender since, etymologically, gender means ‘kind’ or ‘sort’ (cf. Corbett 1991: 1). Furthermore, it is worth pointing out that the type of gender denoted by classifier should be distinguished from biological gender, i.e., gender based on the sex of the referent. In Tagbana for example, the classifier w can be used indiscriminately to refer to a male or female referent. By gender therefore, we mean grammatical gender.

As far as the parallel between classifiers and gender is concerned, it is worth pointing out that the relation between gender and classifiers has been and still is a matter of controversy within descriptive approaches. In most of its uses, the notion of gender is depicted as contributing to the expression of number. In this perspective the concept of gender is understood as “a pair of classes that correspond with each other in the expression of number” (cf. Grinevald and Seifart 2004: 246). The notion of gender is thus fundamentally reduced to the expression of number. The reason for this standpoint is stated in the following terms:

An important feature of Niger-Congo classification systems is the impossibility of dissociating noun affixes encoding number from noun affixes expressing gender-like distinctions” (cf. Grinevald and Seifart, op. cit., p.246).

Although it is true that the use of classifiers has something to do with the expression of number, to reduce the use of classifiers to the mere expression of number is to take a partial look at the whole phenomenon. Furthermore, the assumption according to which it is impossible to dissociate gender and number with respect to the uses of classifier is questionable as far as the case of Tagbana is concerned. A cursory examination of the use of classifiers in Tagbana illustrates this as evidenced by the following examples of the use of the classifier w with the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ ‘landlord’:

4By the expression ‘referent’, I mean any entity being referred to in a situation of communication as perceived

7 (7) wi mãkrɛ défɔ-w-ɔ

‘He has turned into a landlord’

As can be seen in (7), the use of the classifier -w- inside the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ ‘landlord’, is actually non-quantitative5, i.e. the classifier -w-, in défɔ-w-ɔ ‘landlord’ which functions in the clause as predicative complement, does not quantify the entity being referred to. On the other hand, it can be said that the classifier -w- confers a linguistic indication of the kind to which the entity referred to is conceived as belonging. Put in a different way, it could be argued that that the classifier -w- denotes a ‘categorial meaning6’

in the sense that it indicates how the category of persons denoted by the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ , to which the entity being referred to in (7), is said to belong, is thought or perceived by the speaker. The nature of the reference denoted by this type of use of classifiers is actually qualitative. What the speaker wants to highlight in (7), is nothing but the type of person the intended referent has now turned into, i.e., a landlord. Furthermore, the cognitive role of the classifier -w- within the nominal form déf-w-ɔ is to indicate the speaker’s conceptualization of the intended referent as a member of a category of human beings having some kind of power, since a landlord is someone who has control over

certain land. Therefore, the use of classifiers within nominal form denotes a qualitative use

which should be paralleled to the grammatical category of gender conceived as expressing ‘kind’, ‘type’ or ‘sort’. The following uses of the classifiers-l and m, within the nominal froms prɛ́-l-ɛ́ and prɛ́-m-ɛ́ functioning respectively as subjects of the clauses (8a) and (8b), highlight the conceptual side of the uses of classifiers in discourse in Tagbana.

(8) a prɛ́-l-ɛ́ l-i o nã tãni adi

‘The activity of selling is no more fruitful’ b prɛ́-m-ɛ́ m-i yo mã po dihɔ̃ ni

‘Being a salesman requires being courageous’

5I use the term non-quantitative in line with the sense formulated by Huddleston and Pullum (2002), with

respect to the use of the indefinite article a found in ascriptive predicative complements indicating simple membership, as in Jill is a doctor (p.372).

6The term ‘categorial meaning’ is borrowed from Quirk et al. (1985), in line with the use of the zero article

with respect to count nouns having a predicative complement function in a clause, like in, They have become

8

As it can be perceived in (8a) vs (8b), the two nominal forms prɛ́-l-ɛ́ and prɛ́-m-ɛ́, proceed from the one and the same lexical base, i.e. /prɛ́/, which denotes the notion of ‘sell’. Whenever this notion is thought as ‘a short action which happens at given specific time’, the form l is used, while the form m is used whenever the same notion is conceived as a ‘state of being vendor’. So what is at issue with the commutation between the classifiers l and m with respect to the nominal forms prɛ́-l-ɛ́ and prɛ́-m-ɛ́, is conferring an indication of the category to which the intended referent is actually seen as belonging. This function by itself is indicative of the fact that classifiers are meaningful linguistic forms and their uses in discourse tend to corroborate such a view. Therefore, statements such as these can only be considered to be open to question:

Rien n’autorise à affirmer que les classes nominales des langues Niger-Congo soient reliées à une quelconque classification conceptuelle des signifiés des lexèmes nominaux de façon plus directe que les genres indo-européens (cf. Creissels 1999: 181); or

L’opération de réduplication, en étant un lien formel qui unit le marqueur de classe de l’unité nominale au marqueur d’anaphore de détermination et de substitution, nous permet de dire que l’appartenance d’une unité nominale à une classe donnée est d’ordre syntaxique ou morpho-syntaxique et dépend uniquement du marqueur de classe sélectionné par un lexème de base (cf. Dieng 2007: 160)7.

In actual fact, the notion of reduplication referred to by Dieng can be compared to the use of classifiers in postposition to the nominal form. What is more, as seen in example (3), more than one classifier can be used in postposition to the nominal form, which at first sight may give an impression of redundancy. However, as already mentioned, the phenomenon of classifier, in all its manifestations, needs to be situated in its natural context, i.e. making explicit speakers’ conceptualizations of experiential entities in discourse. The so-called reduplication process cannot actually be analysed in its full significance if it is not situated within this dynamic process. In actual fact, each of the

7 It is worth mentioning that this statement of Dieng (2007) is based on the analysis of nominal classifications

9 classifiers postposed to the nominal form indicates a particular thought of the speaker about the intended referent. Classifiers alongside the nominal form denotes a cognitive process, i.e. that of indicating how the actual referent of the nominal form is actually thought of by the speaker in discourse. In fact a cursory analysis of example (3) mentioned above, can help discern this cognitive process:

défɔ-w-ɔ w-é w-i nyɛ̃ lagbãmã ni

‘This particular landlord is kind.’ (cf. example 3)

As can be seen in this example, we have three occurrences of the classifier w, first within the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ ‘landlord’, second in postposition with the vowel -é, i.e., w-é; third in the postposition with the vowel -i, i.e. w-i. But a dynamic view on the use of the use of the classifier w, which goes beyond the directly observable facts, suggest that there are three underlying cognitive processes to be explained here:

(1) the use of the classifier w within the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ ‘landlord’: the cognitive function the classifier w, is to provide a linguistic indication of the kind to which the entity being referred to by the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ belongs. This step may be referred to as the categorizing step.

(2) the use of the classifier w with the vowel -é, in postposition to the nominal form

défɔ-w-ɔ ‘landlord’, i.e., défɔ-w-ɔ w-é. The use of the classifier w with the vowel -é

adds new information about the intended message, i.e. that of singling out the intended referent from the possible referents denoted by the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ ‘landlord’. So what is at issue when the classifier w in correlation with the vowel -é is used in postposition to the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ is no more the need of categorization, but rather the idea of uniqueness, i.e., the uniqueness of the landlord, with respect to the other possible landlords. The perception of the landlord as unique with respect to the predicate ‘being kind’ is quite indicative of the speaker’s subjectivity. And this meaning effect which is added to the intended message is related to the notional content attached to the vowel -é. What is more for this information to be added to the message the vowel -é need to be associated with the classifier w. Therefore the connection between the classifier w and the vowel -é denotes in itself a conceptual relation.

10

(3) the use of the classifier w with the vowel -i in second postposition to the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ ‘landlord’. The third use of the classifier w with the vowel -i, comes after the use of the classifier w with the vowel -é, and adds to the intended message, the information that the intended referent is known to both the speaker and the hearer. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that the classifier w with the vowel -i cannot be used before the classifier w with the vowel -é, both being syntactically postposed to the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ ‘landlord’:

* défɔ-w-ɔ w-i w-é nyɛ̃ lagbãmã ni

This fact actually suggests that the uses of classifiers in postposition to the nominal form is not just a matter of reduplication, but there is something systematic in line with these uses which need to be explained.

With respect to the assumption put forward by Creissels (ibid., p.181.), which suggests that there is nothing conceptual about the uses of classifiers, let us consider the following pair: (9) a k8-i piplé l-i ʤɛ́ hãbé

CL N CL come where?

‘Where does this kind of little boy come from?’ b piplé l-i ʤɛ́ hãbé

N CL come where?

‘Where does the little boy come from?’

As it can be perceived in (9a) vs (9b), the pre-posed classifier k-i, does not show any similarity in form with the nominal form piplé but actually does have a conceptual relation9 with it. This conceptual relation is denoted by the consonant k. The sense effect kind of, or the downgrading effect which is added to the message comes from the notional content attached to this form, and, also highlights the attitude of the speaker towards what is being referred to by the nominal form.

8It is worth pointing out that among the six existing in Tagbana, only the classifier -k-, can be used in

preposition with respect to a nominal form. This syntactic position seems to be in correlation with the nature of the notional content attached to it. More explanations will be brought in line with this particular use of the classifier -k- in the following chapters (cf. Section 3.2.3).

9By conceptual relation I mean the way under which the entity denoted by the nominal form piplé is thought

11 Furthermore, the categorizing function signified by means of the six consonants must be separated from the determining or individualizing function attached to the vowels, which denotes the speaker’s view of a specific referent given a situation of communication. The three vowels i.e. a-, é-, i-, in Tagbana are meant to bring specifications about the intended referent as perceived by the speaker in line with specific situations of communication. In actual fact, there is a kind of complementary relationship between the qualitative function denoted by the six consonants k, l, m, p, t, and w and the quantitative function10 denoted by the vowels a-, é-, i-, with respect to the activity of reference. The following examples could be insightful in grasping this complementary relationship:

(10) a a-k-a k-a nyɛ̃ wa gbabou ni food CL be locative kitchen in ‘There is some food in the kitchen’.

b a-k-a k-i nyɛ̃ wa gbabou ni food CL be locative kitchen in ‘The food is in the kitchen’.

c a-k-a k11-é k-i nyɛ̃ wa gbabou ni

food CL CL be locative kitchen in ‘The special food is in the kitchen’.

(11) a défɔ-w-ɔ w-a mã nyĩnĩ nɛ̃ alani landlord CL Perf. show up here today ‘A landlord has shown up here today’.

b défɔ-w-ɔ w-i mã nyĩnĩ nɛ̃ alani landlord CL Perf. show up here today ‘The landlord has shown up here today’.

10For the quantitative function denoted by the vowels a-, é, and i- in Tagbana, it is worth mentioning that the

concept of ‘existential quantification’ put forwards by Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 358), might be helpful in understanding the point developed here.

11It should be noted that the classifier k-, in this particular context gets voiced and is realized in the actual

12

c défɔ-w-ɔ w-é w-i mã nyĩnĩ nɛ̃ alani landlord CL CL Perf. show up here today ‘The special landlord has shown up here today’.

As can be seen in (10a), (10b), (10c) as well as in (11a), (11b) and (11c), there is a complementary relationship between the consonants k and w, and the vowels -a, -i and -é in line with the process of reference. The use of the classifiers k and w as infixes within the nominal forms a-k-a ‘food’ and défɔ-w-ɔ ‘landlord’in (10a), (10b), (10c) and (11a), (11b) and (11c), can be said to be non-referential, given the fact that the meaning they denote is not link to a particular entity but to what the set of entities they can potentially refer to, have in common. In other words, the classifier k, in a-k-a denotes a set of entities which have the quality of ‘being chewed’ whenever used as food. Therefore any entity perceived by the Tagbana speaker as having the quality ‘being chewed’ is likely to be categorized by the substantive a-k-a. The same thing could be argued for the classifier w, with respect to its use in the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ in (11). In actual fact the cognitive role of the classifier w within the nominal form défɔ-w-ɔ is to indicate that the referent belongs to the category animate beings.These observations lead us to the assumption that classifiers, i.e., the six consonants k, l, m, p, t, and w are linguistic means whereby the speaker of Tagbana represents the experiential elements of his universe as notional or substantial. The meaning they denote therefore is qualitative, i.e. classifiers denote pure abstract notional contents, which affect in certain ways the conceptual life the speakers of Tagbana12.They become means of reference, i.e. functioning as determiners, only when they are associated with the vowels -a, -i and -é. This syntactic connection makes them context-dependent, therefore means of reference. In other words, when associated with the vowels -a, -i and -é, the classifiers k, l, m, p, t, and w presuppose the existence of a contextual entity that the addressee, is expected to be able to identify. As can be seen in (10a), (10b), and (10c) as well as in (11a), (11b) and (11c), the connection of the vowels -a, -i and -é with the classifiers k and w, actually suggests this quantitative side of the use of classifiers in discourse. The association of the vowel -a with the classifiers k and w in (10a) and (11a),

12It should be noted that this position with respect to the nature of the meaning denoted by classifiers has been

affirmed by Croft (1994) in postulating that: “Noun classes are found in determiners or other elements of referring expression. Their function is simply to identify and refer to the concept so classified” (p. 147).

13 for example, presupposes the existence of some food in the kitchen in (10a) and the existence of a landlord who did show up in (11a); while the association of the vowel -é with the classifiers k and w indicates the existence of some special food in (10c) and a

special landlord in (11c).

These observable facts suggest that the phenomenon of classifiers in Tagbana, therefore, cannot be treated adequately on the basis of meaning autonomous syntactic or morphological agreement, nor as governed by selectional restrictions (cf. Wu and Bomodo 2009: 488). As can be observed in the following example, the commutation between the vowels -a and -i in (12a) vs (12b), cannot be said to be constrained by the nominal form

piplé ‘little boy’:

(12) a. piplé l-i nã pã N CL prog come ‘The little boy is coming.’ b piplé l-a nã pã N CL prog come ‘A little boy is coming.’

As it can be perceived through the different glosses in (12a) and (12b), the relation between the nominal form piplé and the postposed classifiers l-i and l-a is not reducible to a mechanical process of formal agreement. What is at issue in the opposition between the vowels -i and -a with respect to the commutation between classifiers l-i/l-a is to provide specifications about how the entity being referred to by the nominal form piplé is introduced into the discourse. In using the vowel -i in (12a), the speaker introduces the entity being referred to as known to the hearer, therefore expecting him to be able to identify the entity referred to by the NP piplé + l-i. There is no such expectation in (12b), where by using the vowel -a, the speaker introduces the entity referred to in the discourse by the NP piplé + l-a as unknown to the hearer. The function of specifying the definiteness or indefiniteness of the entity being referred to in discourse is clear evidence that the vowels attached to the consonants cannot be treated as meaningless units.

In this thesis, consequently, we will argue that the observation of the actual uses of Tagbana classifiers in real situations of communication indicates that they cannot be treated

14

as linguistic forms devoid of meaning. The basic function of classifiers will be argued to allow and make explicit the speaker’s conceptualizations of experiential entities in discourse. This function by itself brings into focus the conceptual aspect related to the use of classifiers in discourse and their relation to the grammatical categories of number and gender. Given the controversy which characterizes the notions of classifiers and gender, it seems worth mentioning that there is a room for establishing a parallel between these two notions in many ways. First, both classifiers and gender represent linguistic means which enable and make explicit speakers’ conceptualizations of extra-linguistic realities. More precisely, they contribute to the definition of referents in discourse as conceptualized by speakers. These linguistic means, therefore, cannot be adequately treated on the basis of a meaning-free syntactic agreement principle. This view constitutes the topic of the next chapter, which is meant to show the limits of the traditional approaches which value the formal aspect of the use of classifiers regardless their semantic input.

15

CHAPTER I: A REVIEW OF THE STATE OF KNOWLEDGE OF THE PHENOMENON

1.1 Classifier within the grammaticalization theory 1.1.1 The notion of grammaticalization

Perhaps, one way to start dealing with classifiers within the grammaticalization theory is to define what is meant by the concept of grammaticalization.

The term grammaticalization appears to have been first used by the French linguist Meillet, who coined the word to refer to the “attribution of a grammatical character to a formerly autonomous word”. Givón also argues that the meaning changes involved in such cases were to be characterized as “bleaching” (cf. Hopper 1996: 218). As a framework for the grammatical description of individual languages, the grammaticalization theory seeks to identify the segments of the lexicon that are most likely to become grammaticalized. This approach, therefore, combines synchronic and diachronic analyses that provide an enlightening and novel perspective on language.

Heine & Reh (1984) put forward some basic assumptions in line with the grammaticalization of linguistic forms in African languages, which are highlighted by Hopper (1996) in the following terms:

The more a form is grammaticalized,

(a)…the more it loses in semantic complexity, functional significance, and/or expressive value;

(b)…the more it loses in pragmatics and gains in syntactic significance;

(c)…the more its syntactic variability decreases; that is, its position in the clause becomes fixed;

(d)…the more it coalesces semantically, morphosyntactically, and phonetically with other units;

(e)…grammaticalization often results in extreme erosion, even to the point where morphemes sometimes remain only as phonetic traces devoid of meaning (cf. Hopper 1996: 222).

As can be perceived through the assumption mentioned above, what is at issue as far as the process of grammaticalization is concerned is the meaning of linguistic forms or

16

morphemes. Should classifiers in African languages be considered as devoid of meaning since they are said to reflect strongly grammaticalized agreement systems?

1.1.2 Classifiers and the hypothesis of lack of semantic transparency

Before any answer is proposed to the question mentioned above, let us consider the following observations:

In most noun classes of the Niger-Congo family, the only semantic distinction which is obviously reflected in noun classes is [+/- human]. The tendency of nouns sharing certain other semantic features to group into certain genders is undeniable, but it is not easy to exactly determine the relevant semantic features, since these features often turn out to be fairly abstract, and the relationship between genders and semantic features is rarely absolute, but rather of a statistical nature. It must be kept in mind that Niger-Congo noun class systems have been grammaticalized a very long time ago, and that evolutions may have distorted the original relationship (if any) between classes and meanings (cf. Grinevald & Seifart 2004: 253).

There are three points to be mentioned here in line with the above statement: (a) The study of classifiers in Tagbana to be presented here will be based on a synchronic view, i.e., the data we are working on in this thesis are collected from actual uses of classifiers in communicative situations by Tagbana speakers. Therefore, the question of whether or not classifiers have gone through a kind of distortion in terms of meanings is not at issue here; instead the question worth asking could be related to how classifiers as linguistic instruments enable and make explicit speakers’ conceptualizations of the entities they talk about in discourse. (b) As far as the process of abstraction is concerned, we can postulate that one of the basic functions of classifiers as linguistic forms is the categorization of the experience of the Tagbana speakers. Therefore, each classifier by virtue of being a linguistic tool which evokes a category of experiential entities should represent an abstract meaning in keeping with its status as an instrument of categorization. (c) Classifiers in Tagabana are not devoid of meaning. Their actual uses in communicative situations will be shown to prove this position. As it can be perceived in (8a) vs (8b), above, the commutation between the classifiers -l- and -m- within the nominal forms prɛ́-l-ɛ́ and prɛ́-m-ɛ́,

17 proceeding from one and the same lexical base, i.e. /prɛ́/, which denotes the notion ‘sell’, brings about two types of conceptualizations i.e., ‘a short action which happens at given

specific time’, with -l-; and a ‘state of being a salesman’ with m. So, the question worth

asking is: how can linguistic forms devoid of meaning contribute to the actualization of a lexical notion in two different meaningful ways? The commutation between the classifiers -l- and -m- with respect to the lexical base /prɛ́/, indicates the kind of entity which the intended referent is thought to belong to. This function by itself is indicative of the fact that classifiers are meaningful linguistic forms.

1.2 Classifiers within the “quantitative-gender” approach

1.2.1 The notion of class within the quantitative-gender approach

Semantically, the most obvious function of commutation between classifiers is said to be the expression of number, i.e. the singular-plural opposition (cf. Grinevald & Seifart 2004: 246). According to this approach, these items reflect classifications of nouns into different classes on the basis of singular versus plural agreement. The notion of class is thus defined as “a regular pairing of a singular and a plural class” (cf. Gundrun & Kerstin 2007: 3). The problem, as it can be perceived through this approach, is the tendency to reduce the uses of classifiers only to their quantitative pole. Observations of the actual uses of classifiers in discourse suggest, however, the need to take into account the qualitative dimension which is inherent to their uses.

1.2.2 The use of classifiers also denotes a qualitative gender

The use of certain classifiers obviously incorporates quantification as part of the meanings to be expressed with respect to the entities mentioned in discourse. But to reduce the meanings they express to only the quantitative dimension is like looking at the phenomenon only from one angle. As mentioned before, classifiers also denote a type or kind meaning which has a category-assignment function in discourse. The commutation between the classifiers -l- and -m- with respect to the same lexical notion /prɛ́/ in (8a) vs (8b) suggests this category-assignment role in discourse. Actually the notions of “act or action” vs

“state” coming out of this commutation obviously denote a category-assignment function.

In (8a), the speaker talks about the activity of selling in general. Therefore, the classifier l-i in (8a) does not denote one particular action of selling. So, the meaning of the classifier l-i,

18

in this use, is not reducible to ‘one’. Furthermore, in (8b), the classifier m-i, is used in reference to a state which is non-quantifiable. So as it can be perceived, there is a qualitative side inherent to the use of classifiers in discourse which needs to be explained along with the quantitative aspect.

Another point which needs to be highlighted with respect to the analysis of the uses of classifiers is their status within the morphosyntactic approach.

1.3. The status of classifiers within the morphosyntactic approach

A good start in dealing with the status of classifiers within the morphosyntactic approach could be Fodor’s observations:

…those nouns and pronouns which became the suffixes of particular classes, genders that is to say, in the beginning fulfilled the function of formatives. It can be presumed the nouns and pronouns in question were first affixed only to the noun, without sticking to the other elements in grammatical relation with it, that is, concord had not as yet come to existence. Enclisis of the noun and the nominal or pronominal suffix that lost its independence gave birth analogically to a class marker. The next step was that the sentence elements dependent on the noun assumed the phonetic form of the class marker and so concord came to be established (cf. Fodor 1959: 186-187).

The above statement calls for a few remarks the point to be highlighted being how classifiers are defined within the morphosyntactic approach.

1.3.1 Classifiers as typical suffixes of nominal classes

According to Fodor a classifier is a nominal or pronominal suffix, which in the beginning fulfilled the function of a formative, and in the end lost its independence, thereby becoming a class marker. So classifiers according to Fodor are typical suffixes of nominal classes. The definition of classifiers as typical suffixes of nominal classes confines classifiers to one syntactic role, which consists in indicating the class to which a particular noun belongs. What is more this function of class-assignment is conceived as purely morphological. This position has been adopted by Grinevald & Seifart (2004: 246) who postulate that the classification denoted by class makers “is basically a classification of nouns and not of

19 classifiers, postulating that: «l’appartenance d’une unité nominale à une classe donnée en est d’ordre syntaxique ou morpho-syntaxique et dépend uniquement du marqueur de classe sélectionné par un lexème de base». It should be pointed, however, that the morphosyntactic analysis of classifiers is based on only one possible syntactic use of classifiers in discourse, i.e. the use of classifier in connection with nominal base. As has been already shown in the introduction, classifiers in Tagbana can be used with the predicate without being in construction with a particular nominal form. When used with the predicate, together with the vowels a-, é-, i-, without an antecedent nominal form, classifiers function syntactically as pronouns and the entity being referred to can only be determined with respect to a specific situation of communication, cf. (4a), (4b), (4c), (4d), (4e), (4f). Should classifiers in this type of use be defined as pronouns or suffixes of nominal classes? The morphosyntactic approach, furthermore, takes for granted that in the “anaphoric use of classifiers, the choice of classifiers, is simply determined by the class to which the head noun (or antecedent) belongs”13. The basic problem with the morphosyntactic approach to classifiers is that it defines classifiers on the basis of only one of their possible uses.

1.3.2 Other shortcomings of the morphosyntactic approach

There are other fundamental problems with the morphosyntactic approach. First, this approach proceeds from the assumption that classifiers are syntactically bound to the noun stem. This position reflects the status of “typical suffixes of nominal classes” assigned to them within this approach. This position in itself is untenable due to the fact that the relation between a noun stem and a classifier occurs under certain conditions. A careful analysis of the use of classifiers in Tagbana suggests that they cannot be reduced to a mere agreement mechanism triggered by the noun-stem. The incontrovertible proof for that is the word for a syringe which, construed as something that restores life contains two classifiers, i.e. k-afuɔ-w-ɔ, which lends itself to the following analysis:

k: the inanimate classifier which refers to the syringe as an instrument;

afuɔ: the noun-stem denoting the notion of syringe;

w: the animate classifier which refers to the syringe as something that restore life

20

ɔ: final vowel of the noun-stem suggesting some kind of unity between the different parts of the word.

This analysis shows that classifiers denote different ways of conceptualizing the referent about which the speaker is talking, therefore, are much more than automatic reflexes of the noun-stem.

As pointed out above, the uses of classifiers in connection with noun stems need to be situated within the speaker’s view of the entity denoted by the noun-stem. More precisely, the structural position ‘noun stem + CL’ is a manifestation of the speaker’s conceptualization of the entity designated by the noun stem. The cognitive function of the classifier consists in making explicit this conceptualization. Therefore, for one and the same noun stem we may have more than one classifier depending on how the speaker conceptualizes the intended referent in discourse. Thus the very same noun-stem /prɛ́/ ‘sell’ can be followed either by the classifier l which denotes clearly delimited entities such as actions with a definite beginning and end, to refer to the act of selling, cf. (8a), and by the classifier m, which denotes homogeneous entities, to refer to the state of being a salesman, cf. (8b). Therefore the relation ‘noun stem + CL’ should be described as a conceptual one, not in terms of syntactic dependency. Furthermore the use of classifiers is not reducible to the assignment of a particular noun to a particular class. There are cases where the morphological criteria may be overridden by semantic criteria, i.e. cases where there is no morphological indication on the noun itself which indicates the class to which the noun belongs, as can be perceived through the following example:

(13) n’dɛ̃ k-i nyɛ̃ tulugu stone CL be heavy ‘The stone is heavy.’

The first thing to be mentioned in line with the use of the classifier k in (13) is that it is not determined by the class to which the head noun n’dɛ̃ (stone) belongs. In other words, the use classifier k is not formally bound to the head noun n’dɛ̃, since there is no morphological similarity observable between k and the nominal n’dɛ̃. Therefore, the definition of classifiers as typical suffixes of nominal classes having a class-assignment function in discourse is open to question. The basic pitfall of the morphosyntactic approach is dealing with the phenomenon of classifiers on the basis of a concept-free syntax which does not

21 reflect the actual use of classifiers in discourse. This way of dealing with classifiers cannot be conclusive since it does not take one step further in grasping the conditions under which classifiers are used in discourse, nor does it seeks for a common denominator underlying the syntactic uses of classifiers. The observations made regarding the morphosyntactic approach can be also applied to the reference tracking approach.

1.4 The reference-tracking approach

1.4.1 The status of classifiers within the reference-tracking apprach

A good way to introduce the reference-tracking approach is the following statement: In many communicative situations speakers need to track referents, i.e. they need to refer back to something that has already been mentioned. The process of referring back is carried out through what is called anaphora which in turn is defined as “the phenomenon whereby one linguistic expression (the anaphor), lacking clear independent reference, can pick up reference or interpretation through connection to another linguistic expression (usually an antecedent)” (cf. Van Letteren 2005: 267).

1.4.2 The reference-tracking approach as an extension of the morphosyntactic approach

As can be seen, the reference-tracking approach describes the relation between nouns and classifiers in discourse as an anaphoric one within which classifiers are said to “lack clear independence reference” and therefore to be strongly dependent on nouns. The reference-tracking approach can thus be said to be an extension of the morphosyntactic approach in the sense that both approaches proceed from one fundamental assumption which is the syntactic dependency of classifiers with respect to nouns. As already mentioned above, this position is untenable given that it proceeds only from one possible syntactic use of classifiers, i.e., the use of classifiers within the noun as a nominal suffix. There are cases, however, where classifiers may be used in discourse without being in construction with a particular nominal antecedent, cf. (4a), (4b), (4c), (4d), (4e), and (4f). Furthermore, by confining the uses of classifiers to an anaphoric relation, the reference tracking approach suggests that the entities they refer to are basically syntactic or syntactic referents. This is far from being the case. Actually, the entities referred to by classifiers used as pronouns

22

without being in construction with a particular noun can only be determined with respect to the situation of communication as can be seen through the following examples.

(14) a w-i nã ʤirɛ́ hãbé CL Prog come where ‘Where does he come from?’ b k-i nã ʤirɛ́ hãbé CL Prog come where

‘Where does that sort of thing come from?’

The classifiers w-i and k-i in (14a) vs. (14b) are used without being in construction with a nominal antecedent. This shows that classifiers are not syntactically dependent on nouns, since they can be used without them. Furthermore the entities referred to by the classifiers w-i and k-i in (14a) vs. (14b) are not syntactic entities, but can be determined only by the communicative situation. What is more, the entity referred to in the discourse is introduced with respect to two types of conceptualizations, which bring about two different expressive effects: in (14a), the entity is introduced in the discourse by the classifier w-i, which indicates a neutral view of a human animate; while in (14b) the same entity is introduced in the discourse by the classifier k-i, which indicates a subjective view of the person referred to with a downgrading effect, i.e. “that sort of thing”. How should the different expressive effects triggered by the use of the classifiers k-i and w-i be accounted for if we take for granted that classifiers are devoid of notional content and therefore reducible to just the syntactic operation of referring back to nouns in discourse? The fact that classifiers can be used in discourse without a nominal antecedent constitutes by and in itself a serious shortcoming of the theory of referent-tracking. Among the approaches which have tried to account for the uses of classifiers in African languages, there is also the indices-analysis approach, which departs from the other approaches in that it considers that the use of classifiers in discourse should be tackled from a communicative viewpoint. This position opens the way to a semantic analysis of the uses of classifiers in discourse.

1.5 The indices-analysis approach

It should be noted that the indices- analysis is a Columbia School theory, grounded in the Saussurian view of language. One of the fundamental explanatory principles of meaning of