MARIE-JULIE FAVE

REINTRODUCTION DU CISCO DE FUMAGE

(COREGONUS HOYI) DANS LE LAC ONTARIO :

DIVERSITÉ GÉNÉTIQUE ET CONSANGUINITÉ

Mémoire présenté

à la Faculté des études supérieures de l'Université Laval dans le cadre du programme de maîtrise en biologie pour l'obtention du grade de maître es sciences (M.Se.)

Département de biologie

FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES ET GÉNIE UNIVERSITÉ LAVAL

QUÉBEC

Octobre 2006

RESUME

La gestion active des populations est souvent désirée et doit être réalisée de façon à minimiser les risques génétiques. Afin de déterminer la meilleure source de cisco de fumage (Coregonus hoyi) pour une réintroduction dans le lac Ontario, le polymorphisme de 10 locus microsatellites a été analysé pour des échantillons de C. hoyi des lacs Huron, Michigan, Supérieur et Nipigon ainsi que pour des échantillons de C. artedi et de ciscos des zones profondes du lac Ontario. Les populations de C. hoyi sont génétiquement diversifiées malgré des baisses d'abondance connues et sont différentiées entre les lacs. Aussi, nos résultats suggèrent que les individus du lac Ontario sont plus étroitement liés aux individus des lacs Huron et Michigan qu'à ceux des lacs Supérieur et Nipigon. Par la suite, des simulations montrent qu'un grand nombre de géniteurs, un rapport des sexes équilibré, une haute proportion de croisements efficaces, un pool de géniteurs diversifié ainsi qu'un grand nombre d'individus introduit minimiserait la consanguinité dans la nouvelle population.

ABSTRACT

Active population management is often desired and should be designed so as to minimize genetic risks. In order to détermine the best source of bloater {Coregonus hoyi) for a reintroduction in Lake Ontario, we analyzed genetic polymorphism at 10 microsatellite loci in samples of C. hoyi from Lakes Huron, Michigan, Superior and Nipigon as well as samples of C. artedi and deepwater ciscoes from Lake Ontario. C. hoyi populations are genetically diversified despite known démographie déclines and they are significantly differentiated among lakes. Also, our results suggest that Lake Ontario ciscoes are more closely related to ciscoes from Lake Huron and Michigan than to ciscoes from Lake Superior or Nipigon. Computer simulations demonstrate that a high number of breeders, a balanced sex ratio, a high proportion of effective crosses, a genetically diverse pool of breeders and a high number of individuals introduced each year would minimize inbreeding in the reintroduced population.

AVANT-PROPOS

Une multitude de gens et d'organismes ont contribué, chacun à leur façon, à l'accomplissement de ce projet :

Je tiens avant tout à remercier ma directrice Julie Turgeon pour m'avoir accueillie dans son laboratoire après une simple petite rencontre, pour m'avoir accordé sa confiance et guidée dans mes nombreux apprentissages, de la pipette à la rédaction finale. Merci pour toutes les discussions que nous avons eues, scientifiques comme humanistes, sérieuses comme ludiques, critiques comme naïves. Je dois également un gros merci à Pierre Duchesne pour avoir programmé les équations qui ont servi lors des simulations exécutées dans le Chapitre 2, sans qui la réalisation de cette deuxième partie aurait été bien plus laborieuse, voire impossible. Je le remercie pour ses recommandations toujours éclairées, précises et efficaces. Merci aux nombreuses personnes qui ont collaboré à l'échantillonnage des ciscos dans les Grands Lacs, soit Rick Salmon (OMNR), Lloyd Mohr (OMNR), Bruce Morrison (OMNR), Owen Gorman (USGS) et Kim Scribner (Michigan State University). Je remercie la Great Lakes Fishery Commission pour l'initiation du projet ainsi que pour son support financier nécessaire à la réalisation de celui-ci. Je remercie également pour leur soutien financier, le FGÉS-CRSNG et le département de biologie.

Merci aux membres du labo JT pour les discussions quotidiennes qui font avancer les choses et qui refont notre petit (ou grand) monde, pour les conseils judicieux ainsi que pour les bons moments passés ensemble: Julien April, Olivier Rey, Cécilia Hernandez, Marie-Claude Gagnon, Ariane Dubé-Linteau, Mélissa Tremblay, Julie Jeukens, Emilie Bilodeau, Milouda Achaboune, Sébastien Bélanger et Kevin Foulché. Pour m'avoir changé les idées aux moments propices, merci à mes amis cépassiens, avec qui les plus fous délires libérateurs sont permis et aux fidèles grimpeurs matinaux, toujours prêts à se dépasser afin d'assouvir notre dépendance aux endorphines, à l'adrénaline et aux grands espaces...

Et bien sûr, un merci tout particulier à François et Martine, pour leur continuel support, pour m'avoir appris à poursuivre mes idées et pour toujours m'encourager à accomplir ce qui me rend heureuse.

Ce mémoire comporte une introduction et une conclusion générales rédigées en français. Les chapitres I et II sont rédigés en anglais car ils sont destinés à être publiés dans des revues spécialisées.

TABLE DES MATIERES

RÉSUMÉ II ABSTRACT II AVANT-PROPOS III TABLE DES MATIERES V LISTE DES TABLEAUX ET FIGURES VII INTRODUCTION GÉNÉRALE 9

RÉINTRODUCTIONS EN NATURE 9 LA FAUNE ICHTHYENNE DES GRANDS LACS LAURENTIENS 12 RÉINTRODUCTION DE C. HOYI DANS LE LAC ONTARIO 1 3 OBJECTIFS DE RECHERCHE 14

CHAPITRE 1: 16 PATTERNS OF GENETIC DIVERSITY IN GREAT LAKES BLOATERS

(COREGONUS HOYI) FOR FUTURE REINTRODUCTION IN LAKE ONTARIO ... 16

RÉSUMÉ 17 ABSTRACT 1 7 INTRODUCTION 19

Laurentian Great Lakes Fish Fauna 20 Reintroduction ofC. hoyi inLake Ontario 21

MATERIALS AND METHODS 22

Biological material 22 DNA extraction and microsatellite analysis 23 Genetic diversity and historical demography 23 Genetic relationships among Great Lakes bloaters andLake Ontario ciscoes 24 RESULTS 25 Genetic diversity and historical demography 25 Relationships among populations and individual assignment tests 26

DISCUSSION 28

Genetic diversity and bottlenecks 28 Differentiation within and among lakes 31

CONCLUSIONS 32 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 3 3 FIGURE LEGEND 34 A N N E X E A : NOMBRE D'INDIVIDUS ( N ) , NOMBRE D'ALLÈLES ( A ) , HÉTÉROZYGOTIE OBSERVÉE (HO) ET ATTENDUE (HE) PAR LOCUS ET MULTILOCUS POUR CHAQUE

ÉCHANTILLON 4 4

CHAPITRE 2 : 48 INBREEDING DYNAMICS IN REINTRODUCED, AGE-STRUCTURED POPULATIONS OF HIGHLY FECUND SPECIES 48

RÉSUMÉ 49 ABSTRACT 4 9 INTRODUCTION 51 MATERIALS AND METHODS 52

Breeding design and inbreeding coefficient. 52 Dynamics of inbreeding coefficient in a reintroduced population 53

RESULTS 55

Effects of breeding design on FH 55 Dynamics ofFwin the reintroduced population 56

DISCUSSION 57 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 6 0 FIGURE LEGEND 61 A N N E X E B : DERIVATION OF RECURRENCE EQUATIONS TO COMPUTE F VALUES 6 4

Discrète générations 64 Three âge classes 65 Nine âge classes 66

CONCLUSION GÉNÉRALE 69

Résumé de la recherche 69 Limites et perspectives .71

LISTE DES TABLEAUX ET FIGURES Liste des tableaux

Chapitre 1

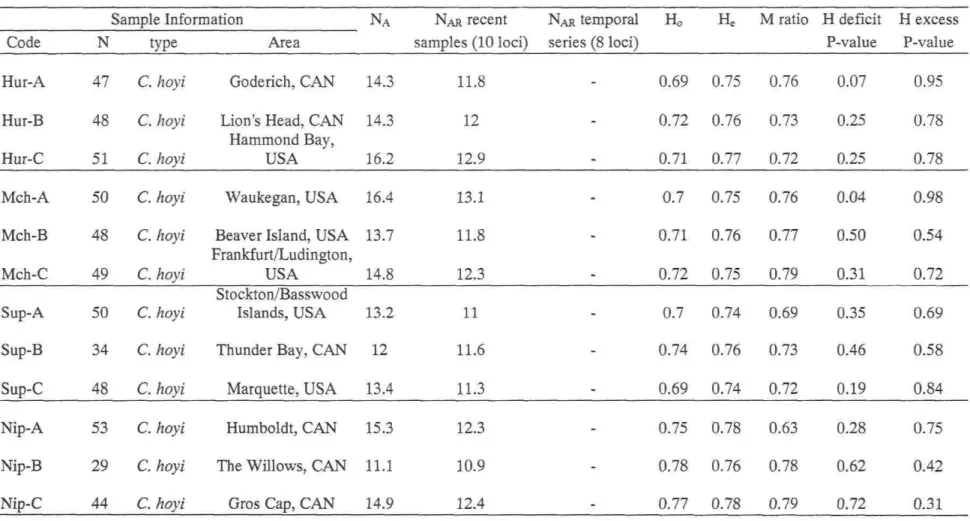

Table 1: Information on ciscoe samples, along with détails on genetic diversity (NA:

number of alleles; NAR: allelic richness; Ho and He: observed and expected

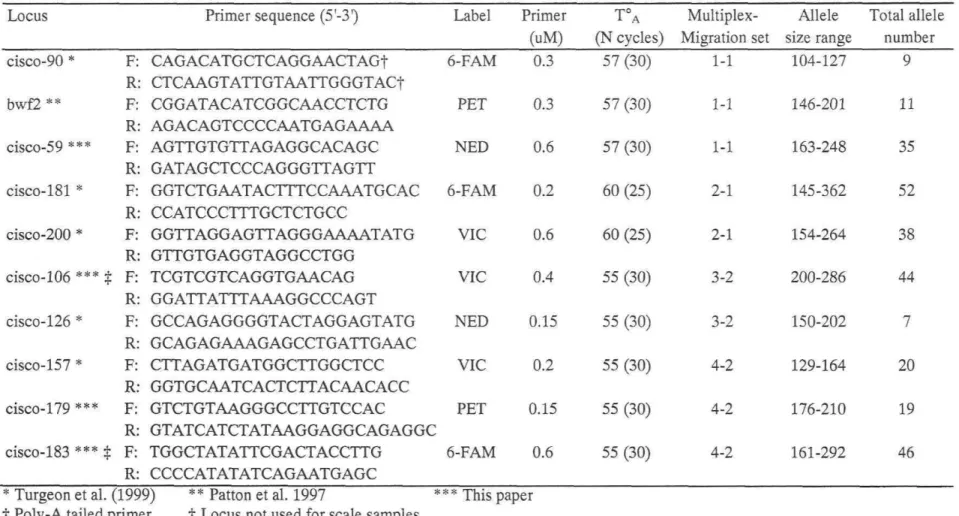

heterozygosity, respectively), and results of démographie tests, (P-values for heterozygosity déficit and excess (Cornuet and Luikart 1996); M ratio of Garza and Williamson (2001)) 35 Table 2: Microsatellite loci used for the characterization of Great Lakes ciscoes: primer séquences with fluorescent label, PCR conditions (primer concentration, TA, and

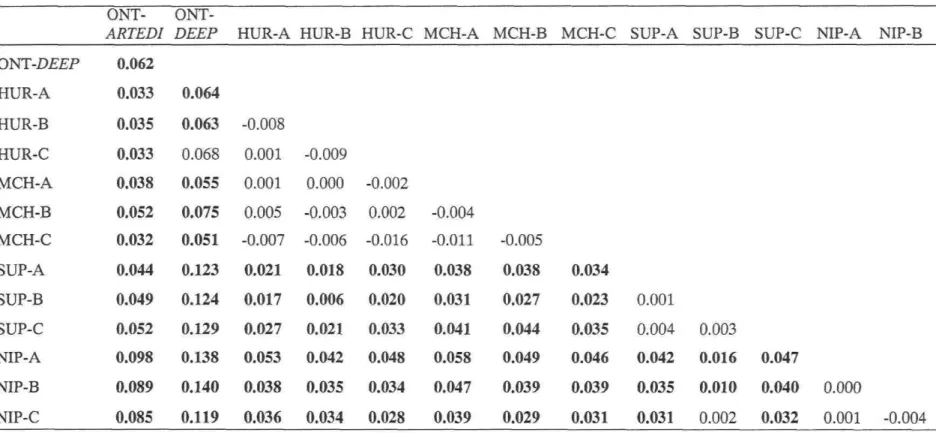

number of cycles), PCR multiplex and migration set, allele size range (bp), and total number of alleles observed 37 Table 3: Pairwise FST values between C. hoyi samples from Potential Donor Lakes (HUR:

Lake Huron; MCH: Lake Michigan; SUP: Lake Superior; NIP: Lake Nipigon) and ciscoes from Lake Ontario (ONT-ARTEDI, ONT-DEEP). FST values

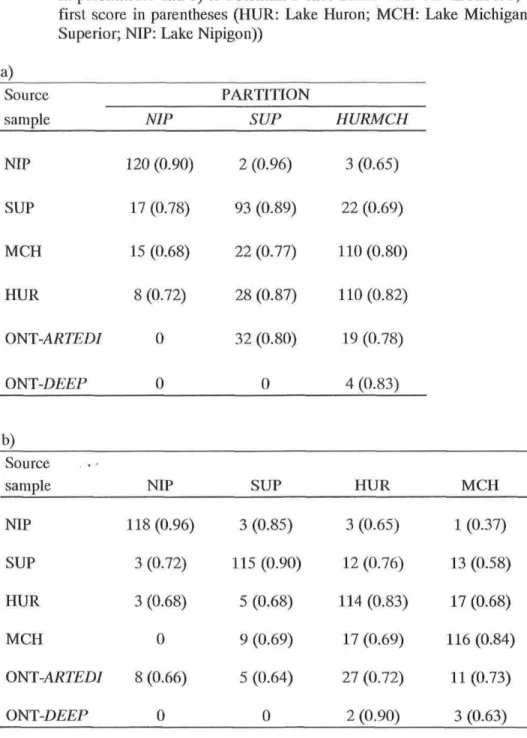

significantly différent from 0 (Bonferroni corrected) are in bold 38 Table 4: Average probability (LnP(D)) and standard déviation across 20 runs of STRUCTURE for K genetic partitions among bloaters from ail Potential Donor Lakes 39 Table 5: Assignment of individual ciscoes from Lake Ontario a) to three genetic partitions defined by STRUCTURE - see Results-, with mean coefficient of membership (q) in parenthèses and b) to Potential Donor Lakes with GENECLASS, with average first score in parenthèses (HUR: Lake Huron; MCH: Lake Michigan; SUP: Lake Superior; NIP: Lake Nipigon)) 40

Liste des figures Chapitre 1

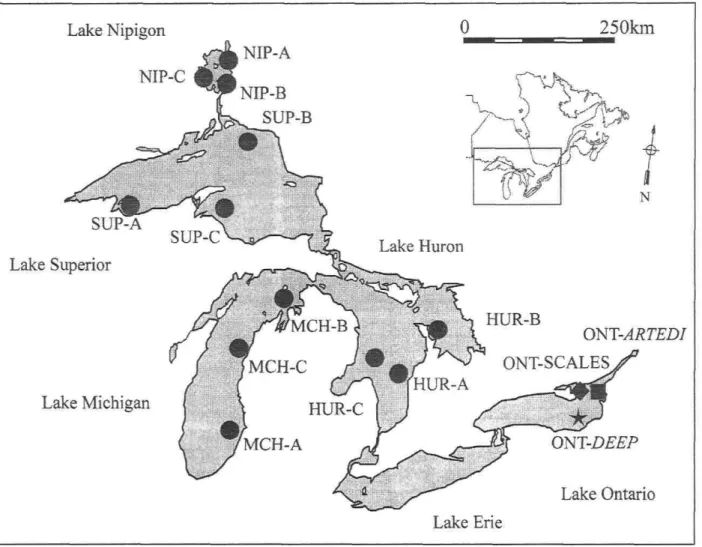

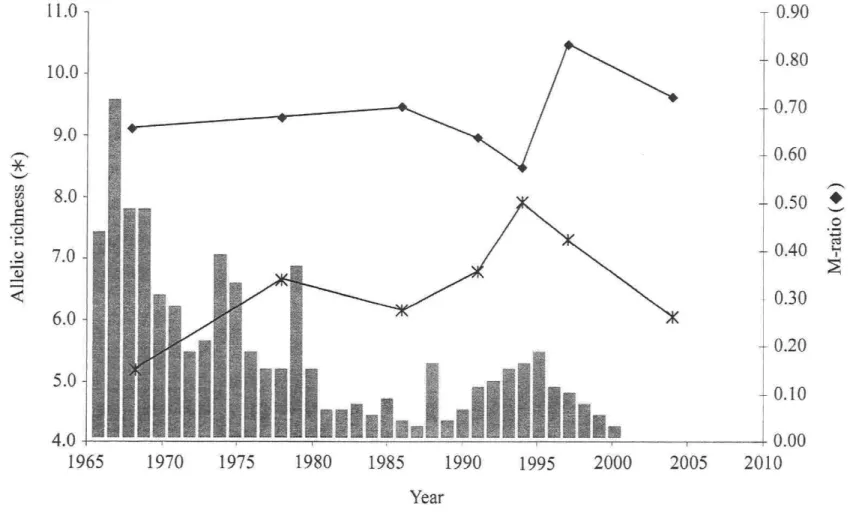

Figure 1: Sampling locations for C. hoyi in Potential Donor Lakes ( • ) and for ciscoes in Lake Ontario ( • : contemporary and historical scale samples of C. artedi; "*": deepwater ciscoes caught in 2002) 41 Figure 2: Temporal variation in allelic richness (NAR) and demographical index (M ratio)

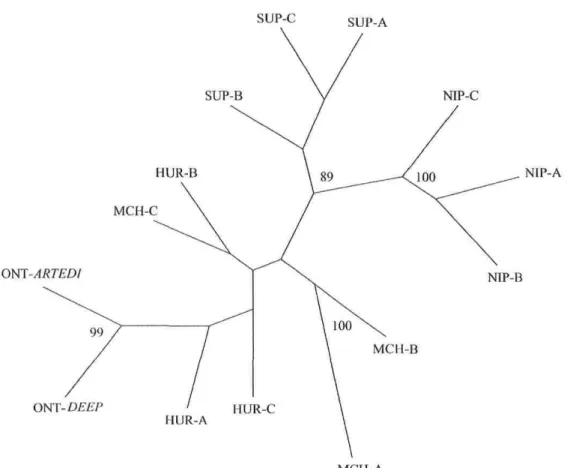

in historical ciscoes from Lake Ontario (Hay Bay, Canada) in relation with relative commercial ciscoes catch in the Canadian waters of Lake Ontario (grey bars; Baldwin et al. 2005) 42 Figure 3: Unrooted DcE-based neighbor-joining phenogram relating ail samples from Potential Donor Lakes and Lake Ontario ciscoes (ONT-ARTEDI: récent sample of C. artedi; ONT-DEEP: deepwater ciscoes caught in 2002). Bootstrap values above 60 are shown 43

Chapitre 2

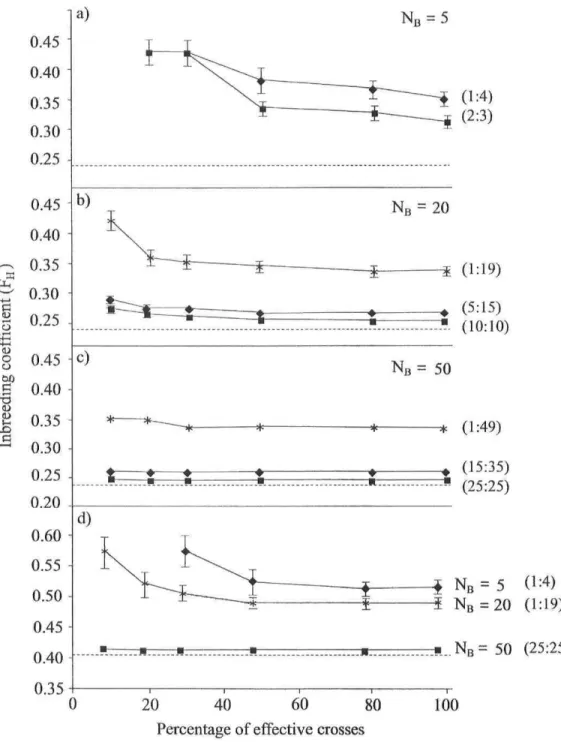

Figure 1: Inbreeding coefficient (FH) generated by crosses with variable numbers of

breeders (NB), M:F sex ratios ( • ~ 1:1; • ~ 1:4; * ~ 1:20), and pools of breeders characterized by high (a, b, and c; F = 0.24) or weak genetic diversity (d; F = 0.41) as a function of the proportion of effective crosses (PEC). Dashed Unes represent the F value for an infinité Wright-Fisher population of similar diversity. Bars represent variance among 200 simulations. Missing data points represents situations with unrealizable calculations because of excessively stringent conditions (a, PEC = 10; d, PEC = 10 and 20) 62 Figure 2: Simulated demography and inbreeding in a new population of bloaters created by supplementation during 15 years. a) Age-3 bloater population size b) breeders inbreeding coefficient (Fw) compared to that of introduced individuals (FH = 0.24; horizontal dashed Une). In both graphs, the number of individuals

supplemented each year is indicated by différent Une types 63 Figure B.l: Supplementation System with three âge classes J, W l , and W2 68

INTRODUCTION GÉNÉRALE

L'homme a un impact global incontestable sur plusieurs fonctions des écosystèmes qui va jusqu'à exercer un contrôle sur ceux-ci. Un grand nombre d'espèces ont été surexploitées tout autour du monde, principalement au cours des derniers siècles où l'accroissement de la population humaine fut substantiel. En réponse à cet impact grandissant, de nombreuses espèces ont vu leurs populations décliner, diminuant parfois jusqu'à l'extinction locale ou globale. Les priorités de conservation devraient donc porter sur des politiques de gestion qui renforceraient la protection contre la surexploitation et toutes les conséquences qui y sont associées. Malheureusement, dans certaines circonstances, la protection complète n'est plus possible à cause de la disparition de l'espèce dans une partie de son aire de répartition historique. Une telle situation ne laisse souvent que la création volontaire d'une nouvelle population pour restaurer la diversité écologique originale et son potentiel évolutif futur.

Une population ayant une diversité génétique élevée augmente ses chances d'adaptation et de survie à long terme dans un environnement où les conditions biologiques sont changeantes (Keller et al. 1994, Hughes et Stachowicz 2004). La diversité génétique nécessiterait d'être maximisée dans les programmes de réintroduction d'espèces en milieu naturel afin d'en augmenter le succès par la persistance de l'espèce sur une longue période de temps (Hedrick et Kalinowski 2000, Hughes et Stachowicz 2004, Tallmon et al. 2004). Une telle pratique doit donc être réalisée avec attention et considération de la biologie de l'espèce, de sa démographie et de ses structure et diversité génétiques (Bowen 1999, Moritz 2002).

Réintroductions en nature

Les pratiques de conservation consistent souvent à prélever des adultes sauvages matures, à effectuer une ou plusieurs reproductions en captivité pour ensuite relâcher les juvéniles le plus rapidement possible dans la région où l'espèce est disparue localement (réintroduction) ou est en sévère déclin (supplémentation). Bien qu'une espèce puisse atteindre de hautes abondances en captivité, entraînées par une meilleure fertilité et une survie plus élevée, l'objectif ultime pour toutes les espèces devrait consister en la

réintroduction en milieu naturel (Frankham et al. 2002). Plusieurs espèces dont les populations ont été historiquement réduites au seuil de l'extinction ont été récemment l'objet de programmes de réintroduction et sont en voie de rétablissement en milieu naturel, telles que l'oryx d'Arabie (Marshall and Spalton 2000), le sabre d'Argent du Mauna Kea (Friar et al. 2000), la crécerelle de l'île Maurice (Groombridge et al. 2000) et la panthère de Floride (Pimm et al. 2006). Par contre, d'autres espèces tel le touladi

(Salvelinus namaycush) dans les Grands Lacs, peinent encore à retrouver des niveaux

d'abondance appréciables et leur persistance dépend encore de l'introduction volontaire de spécimens élevés en captivité (Page et al. 2004).

L'établissement d'une population à partir d'un nombre limité d'individus entraîne le risque de causer un effet fondateur et de générer des niveaux élevés de consanguinité dès la création de la nouvelle population. Un tel effet est observé lorsque la diversité génétique des descendants se trouve diminuée à cause du nombre réduit de parents fondateurs et qu'une ascendance commune s'installe entre les rejetons. Il en sera amplifié si ces individus fondateurs sont apparentés, ou s'ils ont été échantillonnés dans une population ayant une faible diversité génétique. Aussi longtemps que la population reste petite et isolée, la diversité génétique est érodée par la fixation aléatoire des allèles et des mutations délétères tendent à s'exprimer à cause de l'efficacité réduite de la sélection naturelle. (Lande 1995, Lynch et al. 1995, Frankham et al. 2002). De ce fait, les individus consanguins démontrent souvent une survie réduite par rapport aux individus diversifiés lorsqu'ils sont soumis à une menace environnementale (Keller et al. 1994, Saccheri et al. 1998, Sherwin et al. 2000). Même lors de circonstances où la mortalité peut être attribuée à des causes environnementales, ce sont les facteurs génétiques qui, en définitive, déterminent quels individus survivront ou non. La consanguinité peut être un phénomène difficilement identifiable sans équivoque mais doit prendre une place centrale dans un programme de gestion de population et de réintroduction (Frankham et al. 2002).

Afin d'augmenter la probabilité de succès d'un programme de réintroduction, on cherche à maximiser la diversité génétique tandis qu'on cherche à minimiser la consanguinité. Ce but sera atteint en considérant deux aspects simultanément. Premièrement, les géniteurs fondateurs doivent être prélevés autant que possible dans une population génétiquement diversifiée, où aucune baisse d'abondance drastique récente

n'est suspectée. Ce point de départ assure déjà un pool génétique relativement diversifié et représentatif de l'espèce. Par exemple, des programmes de réintroduction du touladi

{Salvelinus namaycush) dans les Grands Lacs ont été conçus de manière à respecter la

diversité et divergence génétique observée entre les différents morphotypes présents (Page et al. 2004, 2005) afin de rétablir la diversité originale. Deuxièmement, la stratégie de reproduction en captivité doit être adroitement planifiée afin de minimiser l'ascendance commune des rejetons en fonction des contraintes biologiques et logistiques induites par le programme d'élevage en captivité. Un plan de croisement factoriel, où la production d'œufs totale de chaque femelle est divisée de manière à ce que chaque partie soit fécondée par un mâle différent, maximise à la fois la production de rejetons et la taille efficace de la population générée (Fiumera et al. 2004).

Le deuxième risque rencontré est celui d'introduire des individus trop différenciés génétiquement dans une population résiduelle et alors y causer une supplantation génique si ces nouveaux migrants ont une valeur adaptative plus élevée ou que leur nombre excède de beaucoup celui des résidents (Frankham et al. 1995, Rhymer et Simberloff 1996). Un cas classique de mélange génétique est celui des canards malards (Anas platyrhynchos) qui se sont hybrides intensément avec des populations d'espèces indigènes en Australie, en Nouvelle-Zélande et à Hawaii. Ces hybridations ont contribué au déclin de espèces endémiques locales et à la perte du phénotype original (Mank et al. 2004). Le croisement d'individus localement adaptés avec des individus génétiquement divergents amène également la possibilité de créer un phénomène de dépression d'outbreeding, où les descendants hybrides se trouvent défavorisés à cause du démantèlement de complexes de gènes co-adaptés et de l'expression d'allèles néfastes récessifs. Un tel phénomène fut identifié par des taux de survie réduits chez les hybrides FI et F2 issus de croisements entre deux populations génétiquement différentiées de saumon rosé (Onchorhynchus

gorbuscha) (Gilk et al. 2004). Par ailleurs, la vigueur d'individus hybrides est identifiée

dans divers systèmes biologiques (Sehaussen 2004), où l'introduction de migrants dans des populations consanguines peut apporter du nouveau matériel génétique bénéfique (Ebert et al. 2002, Whitlock et al. 2000). Aussi, une dépression é'outbreeding peut être considérée comme un phénomène à court terme puisque les combinaisons génétiques défavorables seront éventuellement éliminées par sélection naturelle (Frankham et al. 2002).

La faune ichthyenne des Grands Lacs Laurentiens

La communauté de poissons indigènes des Grands Lacs Laurentiens a souffert de modifications majeures depuis le début du vingtième siècle. L'exploitation commerciale intense et les introductions involontaires d'espèces exotiques agissant en synergie avec la pollution aquatique ont aggravé le déclin de plusieurs espèces indigènes ou ont empêché leur rétablissement (Christie 1973, Mills et al. 1991). Un exemple frappant d'un tel déclin ayant pour cause des influences anthropogéniques est celui des ciscos {Coregonus spp., excepté C. clupeaformis). Les ciscos ont eu une importance économique et culturelle incontestable, plus particulièrement aux États-Unis. La pêche aux 'chubs', florissante jusque dans les années 50, exploitait alors toutes les formes de cisco de profondeur des Grands Lacs. Avec C. artedi et C. clupeaformis, ils formaient alors la plus grande biomasse de poissons des Grands Lacs, les ciscos comptant pour la plus grande biomasse des eaux profondes (Smith 1995, Baldwin 1999). Aujourd'hui, les ciscos sont un groupe décimé et plusieurs formes qui occupaient les Grands Lacs historiquement, dont certaines endémiques, font l'objet de préoccupation. Le statut de C. kiyi est considéré comme préoccupant alors que d'autres espèces sont menacées (C. zenithicus, C. reighardi, C.

nigripinnis) ou disparues (C. alpenae, C. johannae) (Cosepac 2006). Globalement, la

plupart des formes de cisco de profondeur sont maintenant menacées ou disparues, à l'exception du cisco de fumage (C. hoyî) qui est toujours abondant dans certains lacs.

La taxonomie des ciscos des Grands Lacs a posé de nombreux problèmes à cause de leur extrême variation phénotypique et écologique, et ce, malgré les efforts continus depuis Koelz (1928) pour la résoudre. Des travaux récents sur la phylogéographie de C. artedi (Turgeon et al. 1999, Turgeon et Bernatchez 2001a,b, 2003) ont révélé une partie de leur histoire évolutive complexe. L'analyse des polymorphismes mitochondriaux de C. artedi a démontré l'existence de deux races glaciaires qui, après avoir été isolées durant la dernière glaciation du Pléistocène, sont entrées en contact secondaire lors de la recolonisation postglaciaire. Ainsi, les différentes formes endémiques de ciscos des Grands Lacs ont fort probablement évolué suite à une période d'hybridation intensive des deux lignées glaciaires de C. artedi. Des analyses de microsatellites ont indiqué que l'évolution des phénotypes caractérisant les multiples formes endémiques est survenue très récemment, soit après le contact secondaire des deux races glaciaires de C. artedi. De plus, ces formes endémiques ont probablement évolué indépendamment dans chaque lac où elles sont, ou

étaient, rencontrées (Turgeon et Bernatchez 2003). Chaque écomorphotype rencontré est donc l'expression unique d'une partie du pool génique constitué du mélange, à divers degrés de deux lignées distinctes, ce pool étant apparemment toujours en diversification.

Historiquement, quatre formes indigènes de ciscos de profondeur occupaient le lac Ontario, soit C. hoyi, C. reighardi, C. nigripinnis et C. kiyi, ainsi qu'une forme pélagique,

C. artedi. Ces quatre premières espèces ont un jour formé la plus grande biomasse dans les

régions profondes de chacun des Grands Lacs et étaient des sources de nourriture importantes pour le touladi (S. namaycush) et la lotte (Lota Iota) (Smith 1995). Le lac Ontario fut peut-être le lac qui eut le plus haut rendement de pêche de tous les Grands Lacs (Smith 1995). Mais au tournant du 20e siècle, C. nigripinnis, le plus gros des ciscos, était

déjà disparu du lac Ontario et entre 1927 et 1942, C. kiyi et C. reighardi disparurent également (Christie 1973). Le cisco de fumage était à l'époque plutôt dédaigné, étant de plus petite taille que les autres espèces mais il acquit de l'importance une fois les plus grosses espèces décimées (Scott et Crossman 1973). À ce jour, toutes les formes de cisco de profondeur du lac Ontario sont considérées éteintes, laissant uniquement C. artedi et C.

clupeaformis comme coregonidés encore présents (Christie 1973). Cependant, quelques

prises occasionnelles de ciscos de profondeur laissent croire qu'il pourrait toujours exister une population réduite dans les strates profondes du lac. Depuis 2002, moins d'une dizaine de C. hoyi ont été attrapés dans le lac Ontario (Bruce Morrisson, OMNR, comm. pers.). Il reste toujours abondant dans les lacs Huron, Michigan, Supérieur et Nipigon; il n'a par ailleurs jamais été présent dans le lac Érié.

Réintroduction de C. hoyi dans le lac Ontario

En dehors des aspects sociaux et culturels rattachés à la réhabilitation de C. hoyi dans le lac Ontario, le principal gain d'une réintroduction identifié par une majorité de scientifiques (voir Baldwin 1999) serait celui d'occuper l'habitat pratiquement vide des profondeurs du lac. La chaîne alimentaire est actuellement dépourvue de benthivore majeur, les populations de chabots de profondeur (Myoxocephalus thompsoni), le seul autre planctivore benthique saisonnier, étant assez basses (Smith 1995) et constituées presque seulement d'adultes (Robert O'Gorman, USGS, comm. pers.). Elle se termine donc dans un cul-de-sac, laissant de larges populations de mysidés non consommées et occasionnant une perte d'énergie en raison du flux énergétique interrompu. La

réintroduction d'un planctivore indigène se nourrissant de ces invertébrés pourrait recréer le lien trophique manquant et ainsi rétablir les transferts d'énergie originaux (Baldwin 1999, Stewart et al. 2002). Le rétablissement d'un planctivore aurait aussi l'autre avantage direct de fournir une source d'alimentation à S. namaycush et L. Iota. Contrairement aux autres coregonidés du lac Ontario, la distribution verticale dans la colonne d'eau de C. hoyi chevauche presque entièrement celle de S. namaycush, et il en fut une des proies favorisées historiquement (Scott et Crossman 1973).

Certains aspects intrinsèques à C. hoyi devront bénéficier d'une attention plus particulière lors de l'élaboration du plan de réintroduction. Certaines populations de coregonidés sont connues pour être possiblement porteuses de la maladie bactérienne des reins (Bacterial Kidney Disease, BKD) qui est un pathogène obligatoire des salmonidés. Il est connu pour infecter des populations captives et naturelles de poissons et sa transmission s'effectue soit entre adultes, soit d'un parent à la progéniture par les œufs (Warren 1983). Des individus exempts de pathogènes devront être choisis comme géniteurs afin de prévenir l'introduction de la maladie dans les populations du lac Ontario. D'un autre côté, la dynamique de la population suite à la réintroduction relève des caractéristiques inhérentes à l'espèce et à l'environnement. La fertilité, l'âge à maturité, la longévité, la probabilité de survie, les interactions de dépendance à la densité et la capacité de support du milieu devront être considérés comme autant de facteurs clés pouvant influencer l'évolution de la population au cours des années. C. hoyi est connu pour sa démographie peu commune, influencée principalement par le rapport des sexes. Une dynamique cyclique du rapport des sexes s'échelonnant sur 30 ans a été découverte dans le lac Michigan (Bunnell et al. 2006) et est suspectée dans le lac Huron (Schaeffer 2004). Les années de rapport des sexes équilibré sont associées à un fort recrutement tandis que les années de rapport des sexes biaisé vers les femelles à un faible recrutement (Bunnell et al. 2006).

Objectifs de recherche

Dans le cadre de cette recherche, deux objectifs principaux se démarquent et chacun fera l'objet d'un chapitre de ce mémoire. Le premier objectif porte sur l'identification d'une source de cisco de fumage à des fins de réintroduction dans le lac Ontario. Cette source devra être une population (1) génétiquement diversifiée et ne montrant pas de

signes de déclin récent afin de minimiser la consanguinité dans la population réintroduite ; et (2) ayant une ascendance partagée maximale avec les ciscos du lac Ontario pour minimiser les risques de dépression d'outbreeding chez la potentielle population réduite de cisco de profondeur du lac Ontario et augmenter la probabilité d'expression de l'écomorphotype désiré. Pour ce faire, le polymorphisme de locus microsatellites de l'ADN seront analysés pour des échantillons de C. hoyi provenant des lacs Huron, Michigan, Supérieur et Nipigon. Des échantillons de C. artedi et de quelques ciscos de profondeur du lac Ontario seront également analysés afin d'obtenir un portrait de la diversité génétique des ciscos du lac Ontario.

Le deuxième objectif cherche à optimiser le plan de croisement artificiel nécessaire à la création d'individus à réintroduire en milieu naturel de façon à minimiser la consanguinité des individus fondateurs, ainsi qu'à évaluer la dynamique de cette consanguinité à plus long terme pour différents scénarios de réintroduction. Afin d'optimiser le plan de croisement, j'ai exécuté des simulations de croisements artificiels d'individus en utilisant les fréquences alléliques d'un échantillon diversifié et exempt de signe de goulot d'étranglement provenant du Chapitre 1. Par la suite, la dynamique de la population réintroduite a été étudiée en réalisant des simulations de réintroduction en milieu naturel à l'aide d'un modèle mathématique évaluant la dynamique de la consanguinité, couplé à un modèle démographique adapté à l'espèce étudiée. Les résultats obtenus pourront guider la réintroduction du cisco de fumage dans le lac Ontario de façon à maximiser les chances de réussite quant à la conservation d'une diversité génétique élevée à long terme et à l'expression du phénotype désiré.

CHAPITRE 1:

PATTERNS OF GENETIC DIVERSITY IN GREAT LAKES BLOATERS

(COREGONUS HOYI) FOR FUTURE REINTRODUCTION IN LAKE ONTARIO

Running title: Reintroduction of bloaters in Lake Ontario Names of author(s): Marie-Julie FAVÉ and Julie TURGEON*

(correspondence author) Institution address: Département de biologie

Université Laval, Québec, Canada, G1K 7P4 Full mailing address : Département de biologie

Université Laval,

Québec, Québec, Canada G1K 7P4 Phone : 418-656-3135

Fax : 418-656-2043

Email : julie.turgeon@bio.ulaval.ca

Keywords : reintroduction, genetic diversity, bottleneck, Coregonus hoyi, ciscoe, Laurentian Great Lakes

Résumé

La faune originale des ciscos des Grands Lacs Laurentiens a souffert de plusieurs extinctions à l'échelle locale et globale. Les ciscos de fumage (Coregonus hoyi) sont présumés disparus du lac Ontario et la réintroduction de cette espèce benthique est considérée. En tenant compte des fluctuations documentées de cette espèce dans les autres Grands Lacs et de son origine intralacustre récente, nous cherchons à identifier une source génétiquement diversifiée et similaire de cisco de fumage par l'analyse de la diversité et de la structure génétique de C. hoyi en utilisant 10 locus microsatellites. Malgré des déclins démographiques bien documentés, nous n'avons pas trouvé d'évidence de goulot d'étranglement dans 12 échantillons de ciscos de fumage provenant de quatre lacs donneurs potentiels (Huron, Michigan, Supérieur et Nipigon). Par contre, des goulots d'étranglement ont été détectés dans des échantillons historiques de C. artedi du lac Ontario, suggérant que les méthodes génétiques standard de détection des goulots d'étranglement ne peuvent détecter que des étranglements très sévères et de longue durée pour des populations ayant naturellement de hautes abondances. Les patrons de différentiation génétique suggèrent également que les quelques ciscos de profondeur récemment capturés dans le lac Ontario font partie d'une petite population de C. hoyi restée non détectée durant plusieurs années, les individus la composant étant plus similaires aux ciscos de fumage des lacs Huron et Michigan, lesquels ne sont pas génétiquement différenciés. En se basant sur les critères génétiques de grande diversité génétique, d'absence de goulot d'étranglement et de la similarité avec les ciscos du lac Ontario, nous suggérons que les ciscos de fumage provenant des lacs Huron ou Michigan, peu importe le site particulier, seraient un choix de géniteurs judicieux pour effectuer une réintroduction de C. hoyi dans le lac Ontario.

Abstract

The originally diverse ciscoe fish fauna of the Laurentian Great Lakes has suffered many extinctions and local extirpations. Bloaters {Coregonus hoyi) are presumed extirpated from Lake Ontario and the reintroduction of this deepwater fish is under considération. Given the démographie fluctuations of this species in the other Great Lakes

and its reœnt intralacustrine origin, we sought to identify a genetically diverse and similar source of bloaters via an analysis of genetic diversity and population structure of C. hoyi using 10 microsatellite loci. Despite well-documented démographie déclines, we found no genetic évidence of bottlenecks in 12 bloater samples from the four potential donor lakes (Huron, Michigan, Superior and Nipigon). By contrast, évidence of bottlenecks among historical samples of C. artedi from Lake Ontario suggested that standard genetic methods frequently used to identify population bottlenecks can only detect very severe and long-lasting démographie déclines in naturally large populations. Patterns of genetic differentiation also suggested that the few deepwater ciscoes recently caught in Lake Ontario are part of a small undetected C. hoyi population most similar to bloaters of Lake Huron and Lake Michigan, which are not genetically differentiated. On the basis of genetic criteria, and given the high genetic diversity, the absence of significant bottlenecks and the similarity to Lake Ontario ciscos, we conclude that bloaters from any location within Lake Huron or Lake Michigan would be judicious sources of breeders for reintroducing C. hoyi in Lake Ontario.

Introduction

Human impact on the environment is undeniable. For many species, it has repeatedly led to huge démographie déclines driving local populations and species to extinction. Conservation priority should obviously be given to improved management and protection policies. Unfortunately, the near or total extirpation of a species from a portion of its native range too often prevents this idéal approach. In such cases, reintroduction and/or supplementation of vacant site(s) is the only option to restore ecological diversity and its associated biological functions. Reintroduction and supplementation imply the release of artificially-reared individuals, or alternatively the translocation of wild-caught individuals, in an area where a native species is extirpated or severely declined, respectively. Thèse conservation practices, however, should be conducted with care and considération for the species biology, health status, genetic structure and diversity (Bowen 1999, Moritz 2002).

The first genetic risk associated with establishing a new population is a founder effect whereby genetic diversity is reduced because of the small number of individuals used for the reintroduction. This effect can be further amplified if founding individuals are taken from a genetically depauperate population, e.g. because of a past bottleneck (Ramstad et al. 2004), and it sets the stage for increased inbreeding in the new population. Care should therefore be taken to sélect founders so as to reflect the original genetic diversity (Frankham et al. 2002, Moritz 1999). Indeed, reduced diversity in small populations can negatively affect fitness-related traits such as reproductive capacity or survival; it can also increase the probability of expression of deleterious mutations, and eventually bring a population to extinction (Ryman and Laikre 1991, Frankham 1996, Hartl and Clark 1997, Frankham et al. 2002, Keller and Weller 2002,). For example, reduced genetic variability has been associated with weak résistance to bacterial pathogens and viruses in animal species (O'Brian and Evermann 1988, Sherwin et al. 2000). Similarly, high genetic diversity was associated with enhanced survivorship under changing biological conditions in eelgrass Zostera marina (Hughes and Stachowicz 2004), indicating that it should be maximized to improve the likelihood of long-term persistence of reintroduced species.

Another genetic risk, often considered in supplementation programs is the possibility of creating an outbreeding dépression as a resuit of crosses between indigenous and introduced individuals (Hedrick and Kalinowski 2000). Indeed, reproductively isolated populations may evolve unique co-adapted gène complexes spécifie to local environment (Lynch 1991), and disruption of those complexes by hybridization with individuals bearing différent genomic architecture may negatively affect fitness-related traits in offspring. For example, Gilk et al. (2004) hâve shown that FI and F2 hybrids between genetically differentiated pink salmon (Onchorhynchus gorbuschà) populations had significantly reduced survival rates. On the other hand, évidence for hybrid vigor is reported in many Systems (e.g. Seehausen 2004), indicating that the introduction of foreign individuals in inbred or bottlenecked populations can often be valuable by providing new genetic material and bénéficiai alleles (Ebert et al. 2002, Whitlock et al. 2000, Tallmon et al. 2004). Furthermore, an outbreeding dépression could be a short-term phenomenon since the unfit genetic combinations would eventually be nearly eliminated by natural sélection (Frankham et al. 2002).

Laurentian Great Lakes Fish Fauna

The native fish community of the Laurentian Great Lakes has suffered major modifications since the beginning of the 20th century (Crossman 1991). Intense

commercial fisheries, inadvertent exotic species introductions and water pollution hâve exacerbated the downfall of many indigenous species and/or prevented their recovery (Christie 1973, Mills et al. 1991, Ricciardi 2001). Thèse modifications hâve had effects on the original fish biodiversity of the area as well as on lake ecosystem functions (Horns et al. 2003, Ebener 2005, Holey and Trudeau 2005, Mills et al. 2005)

One striking example of a human-induced native species décline in the Great Lakes is that of the ciscoes (Coregonus spp. except C. clupeaformis). Each lake once possessed several ecomorphotypes displaying différences in trophic traits, diet, spawning season, and habitat depth (McPhail and Lindsey 1970, Scott and Crossman 1973, Smith and Todd 1984, Turgeon et al. 1999). Many of thèse were endémie to the Great Lakes and enhanced global biodiversity of the zone (Scott and Crossman 1973). Moreover, thèse unique ecotypes likely evolved recently within each lake following extensive secondary contact between two glacial races (Turgeon and Bernatchez 2001, 2003). Nowadays, the pelagic

lake herring {C. artedi) is présent in ail of the Great Lakes, while most deepwater ciscoes are either extinct or restricted to Lake Superior and/or Lake Nipigon (Philips and Ehlinger 1995). The only exception is the bloater (C. hoyi), which remains abundant in Lakes Huron, Michigan, Superior and Nipigon (it never occurred in shallower Lake Erie).

In Lake Ontario, the décline in forage fishes such as C. hoyi followed the gênerai pattern observed in the other Great Lakes, with three out of four deepwater forms gone extinct by the mid-20th century, namely C. nigripinnis, C. reighardi and C. kiyi (Christie

1973). Bloaters persisted longer but became scarce by the 60s, and the last documented catch dates back to 1983 (Baldwin 1999). Bloater's décline coincided with the expansion of invading smelt populations {Osmerus mordax), but the présence of other non-indigenous species, notably the alewife {Alosa pseudoharengus) and the sea lamprey {Petromyzon

marinus), may also hâve accelerated the final démise of C. hoyi (Christie 1973, Christie

1974, Stedman and Argyle 1985). However, rare occasional catches of deepwater ciscoes since 2002 (less than ten individuals) suggest that there could still exist an undetected remnant population of C. hoyi in the deepest layers of the lake, or alternatively, that lake herrings are gradually invading the underexploited deep layers of the lake.

Reintroduction ofC. hoyi in Lake Ontario

The reintroduction of C. hoyi in Lake Ontario has been identified as a priority for achieving a healthy lake ecosystem through the restoration of the native fish fauna (Baldwin 1999, Stewart et al. 1999, Eshenroder and Krueger 2002). Beyond a gain in native biodiversity, the principal benefit of C. hoyi rehabilitation in Lake Ontario would be to re-establish the original energetic pathways linking benthic production, which is now left largely unconsumed, with top predators in the upper layers of the lake. Indeed, bloaters feed on epibenthic amphipods {Mysis relicta, Diporeia spp.) and perform diel vertical migrations (TeWinkel and Fleischer 1999), thus providing a trophic link with their indigenous predators, namely Salvelinus namaycush and Lota Iota.

In this paper, we use genetic criteria to identify a source of bloaters that would minimize genetic risks associated with its planned reintroduction in Lake Ontario. We first aimed at identifying genetically diverse, non-bottlenecked population(s) that would help minimize inbreeding in the introduced population. Concerns for this potential effect are

justified because of the known unstable demography of bloaters in ail of the Great Lakes (Schaeffer 2004, Baldwin et al. 2005, Bunnell et al. 2006). Secondly, we wished to identify a source population of C. hoyi with maximum shared ancestry with Lake Ontario ciscoes in order to minimize the risk of outbreeding dépression in the putatively remnant deepwater-like ciscoes of Lake Ontario. To this effect, we analyzed variation at 10 microsatellite loci in C. hoyi samples from ail potential donor lakes. In addition to that, we also tested for the origin of the putatively remnant deepwater-like ciscoes of Lake Ontario, composed of either individuals derived from pelagic C. artedi progressively invading the deeper layers of the lake, or from a truly remnant C. hoyi population that was undetected for décades. We hypothesize that if the genetic differentiation between those deepwater ciscoes and Lake Ontario C. artedi individuals is non-significant, the deepwater population originates from recently derived C. artedi individuals invading the vacant benthic habitat. The alternate hypothesis of a significant genetic differentiation would indicate an historical isolation between the two populations that allowed for a détectable divergence, and thus confirming the remnant origin of a deepwater C. hoyi population.

Materials and Methods

Biological material

Tissue samples (adipose fin or muscle) were obtained from 551 bloaters collected from three différent sectors within each potential donor lake (PDL), namely Lake Huron, Lake Michigan, Lake Superior, and Lake Nipigon (Table 1). Given the virtual absence of

C. hoyi in Lake Ontario, we used samples of C. artedi individuals as a surrogate sample of

the genetic diversity of Lake Ontario ciscoes. Indeed, because of the intralacustrine diversification of Great Lakes ciscoes (Turgeon and Bernatchez 2003), extant lake herrings are the closest living relatives and share maximal ancestry with bloaters that once inhabited Lake Ontario. Thus, we analyzed tissue from 51 C. artedi (ONT-artedi) and five deepwater ciscoes (ONT-deep) caught in Lake Ontario in 2004 to portray Lake Ontario modem genetic diversity. Ail samples were preserved in 95% ethanol.

In addition, 116 Lake Ontario C. artedi scale samples from an historical temporal séries (1968 to 1994) were characterized along with 28 EtOH-preserved samples from 1997 used by Turgeon and Bernatchez (2003) (Table 1). Ail of thèse samples were caught

in Hay Bay (Canada) and were obtained from the Glenora Fisheries Research Station (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources). This temporal séries was used to assess the ability of our markers to detect known population décline (see below).

DNA extraction and microsatellite analysis

DNA from récent samples was extracted either by using Miniprep extraction plates and a vaccum pump (Millipore Montage BAC96 Miniprep Kit) following the manufacturer's instructions or with a classic phenol-chloroform protocol (Sambrook and Russell 2001). Ail individuals were amplified at 10 microsatellite loci, among which five were developed for this study (Table 2). Ail multiplex amplifications were performed in a 15 juL total reaction volume including -20 ng of genomic DNA, 20 //M of each dNTP, IX buffer (500 mM KC1, 200 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.8, Triton X 1%), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1U Taq

polymerase and 0.15-0.6 |J.M primer. Amplification profiles were as described in Turgeon et al. (1999). Diluted PCR products were pooled into one of two genotyping sets and separated by capillary electrophoresis on an ABI 3100 automated sequencer (Table 2). Alleles were sized using GeneMapper V. 3.7.

DNA from scale samples was extracted following the protocol of Nielsen et al. (1997) with the following modifications: scales were digested 2 hours at 55 °C, 10 juL of RNAse and 10 juh of proteinase K were added 45 minutes before the end of the digestion, and the second elution step was performed with 10 //L of distilled water. Two microsatellite loci (cisco-106 and cisco-183) were discarded because amplification was very difficult on low DNA concentration samples. Each locus was individually amplified by two successive PCR reactions; 1.5//L IX BSA was added to the reaction and amplification was performed with 5 additional cycles.

Genetic diversity and historical demography

Estimated number of alleles (NA), expected (HE) and observed (Ho) heterozygosity

were calculated using GENETIX V.4.05.2 (Belkhir et al. 2004). We examined the data for the présence of allelic "drop-out" events associated with low quality or degraded DNA using MICROCHECKER V.2.2.3 (Van Oostershout et al. 2004). Allelic richness (NAR,

Petit et al. 1998) was estimated independently for récent and historical samples given the important variation in sample sizes and the différent number of loci considered (Table 1).

Tests for déviation from Hardy-Weinberg and linkage equilibria were conducted using exact tests in GENEPOP V.3.4 (Raymond and Rousset 1995). Bonferroni corrections (Rice 1989) for multiple comparisons were carried out using FSTAT V.2.9.3.2 (Goudet 2001).

We employed two methods to identify past bottlenecks in each PDL sample. First, data were analyzed with BOTTLENECK V.1.2.02 (Cornuet and Luikart 1996), assuming a two-phase mutation model (TPM) (variance=30%, SMM=70%). Under mutation-drift equilibrium, important réduction in effective population size is expected to yield a significant heterozygosity excess given the observed number of alleles (hereafter HE test). Second, we computed the M statistic of Garza and Williamson (2001), i.e. the ratio between the mean number of alleles and the allele size range. One locus (cisco-126) was not included in this calculation because its compound nature (Turgeon et al. 1999) biased calculations towards very low M values. According to Garza and Williamson (2001), an M value equal to or smaller than 0.68 is a conservative indication of an important réduction in the effective size of a population, while an M value greater than 0.82 is indicative of populations that hâve not experienced substantial size fluctuations. Moreover, given that bloater populations are known to undergo large démographie fluctuations (e.g. Bunnell et al. 2006), we used the temporal sample séries available for C. artedi from Lake Ontario to assess the potential of our genetic markers at detecting a réduction in genetic diversity and/or a past bottleneck. This was achieved by comparing M and NAR values to the relative abundance of ciscoes (as estimated by commercial catches) during the period covered by our temporal samples séries (i.e. 1968 to 1997).

Genetic relationships among Great Lakes bloater s and Lake Ontario ciscoes

Global patterns of relationships among Great Lakes bloaters and Lake Ontario ciscoes were first assessed with conventional analyses. Inter-population DCE distances (Cavalli-Sforza and Edwards 1967) were estimated and a Neighbor-Joining tree was constructed using PHYLIP V.3.65 (Felsenstein 2005). Then, pairwise FST values among ail récent samples were estimated with FST (Weir and Cockerham 1984) using ARLEQUIN V.2.0 (Schneider et al. 2000). Given the small number of deepwater ciscoes caught in Lake Ontario (ONT-deep; N = 5), we investigated the effect of this small sample size on patterns of genetic differentiation identified with the latter analysis. To this effect, virtual samples were created by randomly choosing 5 individuals from a PDL C. hoyi sample and

assessing differentiation. This was repeated ten times and FST significance levels obtained were compared to the actual FST significance level between ONT-deep and ONT-artedi.

Given the very récent ancestry of ail ciscoe types in the Great Lakes, we also used an analytical approach seeking to group PDL bloaters with similar ancestral genetic characteristics. Similarity of Lake Ontario ciscoes to thèse référence groups was then assessed. The référence groups were defined with the Bayesian method implemented in STRUCTURE V.2.1 (Pritchard et al. 2000). Ail PDL individuals were included to détermine the number of cohesive genetic clusters (K) présent in the System. Twenty runs were performed for each K value (K =1 to 9), with 10 000 burn-in and 10 000 MCMC itérations. Evanno et al. (2005) recently used second-order rate of change in Ln P(D) between successive K values in order to enhance the ability of STRUCTURE to detect the real number of clusters when K >2 but, this procédure did not always yield better results (Waples and Gaggiotti 2006). Therefore, we chose to use the original advice of Pritchard et al. (2000) and selected the value of K associated with the highest posterior probability of the data (LnP(D)), while also seeking to minimize variability among runs.

Having identified three cohesive groups as référence clusters (see Results), a second analysis was performed with STRUCTURE to estimate the genomic proportion of each Lake Ontario individual's shared ancestry (q) in each cluster. Then, each individual was assigned to the référence clusters of highest q value, but only if over 50%.

Thèse assignments were then compared to those obtained with assignment tests performed with GENECLASS V.2.0 (Piry et al. 2004) using the Bayesian statistical approach of Rannala and Mountain (1997), which is more efficient than distance-based methods (Cornuet et al. 1999). Given that the true population of origin of Lake Ontario ciscoes is obviously not any of the PDLs, we forced the assignment of each spécimen to one of the PDL by not allowing the exclusion of any population of origin.

Results

Considérable microsatellite gène tic variation was detected in ail samples (Table 1, detailed information available in Appendix A). In PDL samples, the observed heterozygosity (Ho) was rather high (0.57 to 0.78), and allelic richness (NAR) varied from

10.9 to 13.1 alleles per sample. In Lake Ontario historical samples, for which only 8 loci were considered, NAR ranged from 5.1 to 7.9 alleles per sample. Exact probability tests

across populations did not show any significant departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Similarly, no significant déviation from linkage equilibrium was found for any pair of loci (P > 0.05).

Very little évidence of past bottlenecks was found among PDL samples with either of the two tests employed. First, Wilcoxon sign rank HE test (Cornuet and Luikart 1996) did not yield significant results for any samples (Table 1). Likewise, M ratios seldom exceeded the range of values indicative of drastic démographie changes (0.68-0.82) in PDL bloater samples. Only one sample from Lake Nipigon (NIP-A) yielded M ratios close or below the cut-off value indicative of a population bottleneck, while other samples showed values between 0.69 and 0.79 (Table 1).

For the Lake Ontario temporal séries, M ratios ranged from 0.57 to 0.83, with samples from 1968, 1991 and 1994 having M ratios clearly below the 0.68 threshold value, and the 1997 sample exhibiting an M ratio slightly over 0.82 (Table 1). Variation of M ratio and NAR over the period covered by the temporal séries followed, albeit with some lag for M, the historical records of relative ciscoes catches in the Canadian waters of Lake Ontario (Figure 2). The important réduction in population size, which reached its lowest level around 1987, was reflected by a drop in allelic richness in the 1986 sample as well as a décline in M ratio from 1986 to 1994. A sensible démographie rebound between years 1989 and 1995 was also followed by a small increase in NAR and M ratio. Finally, a second

decrease in NAR and M ratio was observed in 2004, once again following an important drop

in ciscoes abundance between 1995 and 2000.

Relationships among populations and individual assignment tests

The neighbor-joining DCE phenogram relating PDL bloaters samples and Lake Ontario ciscoes readily suggests greater genetic similarity within lakes as well as between nearby lakes (Fig. 3). Samples from Lake Nipigon clearly defined a distinct cluster and

formed a very well-supported group with bloaters from the geographically proximate Lake Superior. Although of uncertain taxonomic status, ciscoes from the deepest section of Lake Ontario (ONT-deep) strongly grouped with the lake herring sample (ONT-artedi; bootstrap support of 99%, Fig. 3). It is worth noting that the branch linking the latter sample is not excessively long even if leading to a différent taxon. Finally, samples from Lakes Huron and Michigan did not show any clear grouping pattern but stood between the Ontario and Superior-Nipigon clusters, reflecting their geographical setting.

The pattern of population differentiation, which was globally significant (FST = 0.027; P < 0.00001), reflected similar trends. First, there was no significant differentiation within any of the PDLs. Likewise, there was no évidence for significant differentiation between samples from Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. By contrast, nearly ail other comparisons between PDLs yielded significant FST ranging from 0.010 (NIP-B/SUP-B) to 0.058 (MCH-A/NIP-A), with only one FST value not significantly différent from zéro (SUP-B/NIP-C). The lake herring sample from Lake Ontario was significantly différent from ail PDL (FST: 0.033 - 0.098) as well as from ONT-deep (0.062, Table 3). The small

sample from ONT-deep was also differentiated from most PDL samples, but less so from bloater samples from Lake Huron or Lake Michigan. Differentiation was likely not due to the small sample size of ONT-deep, as none of the pseudo-samples of size N = 5 were differentiated from their source sample (P > 0.05).

Bayesian clustering analysis identified three genetic clusters among PDL individuals. Evidence for three clusters was provided on the one hand by the highest probability value for K = 3, and on the other hand by the much larger standard déviations among runs as K further increased (Table 4). Ail but 20 individuals unambiguously belonged to one of thèse référence clusters, with highest coefficients of membership (q) averaging 0.83 ± 0.17 (Table 5a). Each partition included a majority of individuals from Lake Superior, Lake Nipigon or from both Lakes Huron and Michigan, and thèse partitions are referred to accordingly hereafter (i.e. Sup, Nip, and HurMch).

Lake Ontario ciscoes were easily assigned to one of thèse partitions, with a high average coefficient of membership of 0.79 ± 0.14 (Table 5a). Nineteen C. artedi were classified in HurMch and 32 were classified in Sup. No individuals were classified in Nip.

Four out of the five deepwater ciscoes were classified with strong support in HurMch (q > 0.67, Table 5a) while the other deepwater cisco could not confidently be assigned. The assignaient procédure with GENECLASS was also successful, with 84% of individuals confidently reassigned to their lake of origin. As for Lake Ontario individuals, 27 C. artedi were assigned to Lake Huron, 11 to Lake Michigan, eight to Lake Superior and five to Lake Nipigon (Table 5b). Individuals assigned to Lakes Huron and Michigan were assigned with higher average q scores (0.72 and 0.73 respectively) than individuals assigned to Lakes Superior or Nipigon (0.66 and 0.64 respectively). Deepwater ciscoes were assigned either to Lake Huron (N = 2) or Lake Michigan (N = 3). Even if more individuals were assigned to Lake Michigan than Huron, those assigned to Lake Huron were assigned more confidently (0.90).

Discussion

Genetic diversity and bottlenecks

Our analyses revealed that ail contemporary Great Lakes bloater populations hâve retained substantial genetic diversity, and that there are neither strong nor widely distributed genetic évidence of démographie bottlenecks. Thèse results are ail the more surprising given the high commercial exploitation during the last century and the well-documented drastic fluctuations in ciscoe population abundances (Christie 1974, Baldwin et al. 2005, Bunnell et al. 2006). Indeed, analysis of commercial catch data and long-lasting monitoring programs (Christie 1973, Baldwin et al. 2005) hâve clearly demonstrated that bloater and lake herring populations hâve been reduced below exploitation levels on several occasions during the 20th century. For example, in Lake Superior, abundance of deepwater ciscoes inferred from catch data reached a maximum abundance slightly above one million fish at the end of the 70s, but dropped below 50 thousands fish during three periods in the 20th century (Baldwin et al. 2005). Similar trends are also documented from the other Great Lakes (Horns et al. 2003, Baldwin et al. 2005, Fleischer et al. 2005). In Lake Michigan, Bunnell et al. (2006) recently analyzed a 30 year-long data séries and they hâve convincingly suggested that population fluctuations may be under natural endogenous cycles whereby high and low recruitment phases alternate at about 15 years intervais. Thus, despite repeated periods of population réductions, widely distributed genetic évidence for bottleneck is lacking.

It appears that the M ratio and HE tests, albeit widely used as standard tests in conservation genetics, often fail to detect the genetic signatures expected from major démographie déclines in real endangered populations. Indeed, failures to detect significant loss of diversity in cases of known démographie déclines hâve been reported for a variety of organisms such as marsupials (Jones et al. 2004), reptiles (Kuo and Janzen 2004), mammals (Whitehouse and Harley 2001, Harley et al. 2005), insects (Watts et al. 2006), and fish (Lippe et al. 2006). Among the potential causes invoked by thèse authors, the pattern of démographie décline, the species lifespan, a past founder effect and the type of genetic markers may hâve played a rôle in the case of the Great Lakes bloaters. First, a graduai rather than sudden pattern of décline has been put forward as a possible cause for the absence of impact on the number of alleles and heterozygosity (Kuo and Janzen 2004, Lippe et al. 2006). For the majority of Great Lakes ciscoes, population décline was long and graduai and span over more than 80 years, with huge historical abundances apparently preventing steep population drops in abundances. Moreover, although population réductions reported in ciscoes appear enormous, thousands of individuals were still counted at lowest historical abundances. Thèse minimum, yet large population sizes probably prevented any significant allelic loss, and may in fact not qualify as real bottlenecks. Similarly, a graduai décline is reported to reduce the power of the HE test at detecting bottlenecks (Harley et al. 2005). Second, Kuo and Janzen (2004) and Lippe et al. (2006) suggested that the long lifespan of species could also prevent the détection of bottlenecks with both tests. Although not explicitly invoked, this factor may also hâve played a rôle in the failure to detect known bottlenecks in long-lived species such as éléphant (Whitehouse and Harley 2001), Tasmanian devils (Jones et al. 2004), and rhinocéros (Harley et al. 2005). With regards to bloaters, they are known to live between 6 and 11 years (Scott and Crossman 1973) and this moderate lifespan could be an aggravating factor contributing to the failure of the tests. Third, Jones et al. (2004) proposed that past founder effect could so severely reduce the original genetic diversity that no clear pattern of allelic loss could be detected after subséquent bottlenecks. In the case of the Great Lakes ciscoes, however, the opposite argument seems to apply. Indeed, extensive genetic diversity is présent in Great Lake ciscoes (Table 1, Appendix A, Todd 1981, Turgeon et al. 1999, Turgeon and Bernatchez 2003) and very large long-term effective population sizes in thèse forage fishes has apparently prevented major losses of

genetic variation. In fact, only very severe and prolonged bottlenecks such as in Lake Ontario hâve caused a réduction in population abundance sufficient to generate a strong genetic érosion signal (Table 1, Figure 2).

Finally, failure to detect bottlenecks may be due to the lack of resolution caused by mutation modalities or allele frequency distribution of genetic markers, as has been suggested by Whitehouse and Harley (2001). This potential explanation, however, is rejected for Great Lakes bloaters. Indeed, the ability of our markers to identify bottlenecks is validated by the results for the Lake Ontario historical séries, with M ratios below or on the threshold value of 0.68 in 1968, 1978, 1991 and 1994. Knowing that Lake Ontario harbors the most severely impacted populations of ciscoes, thèse results support the hypothesis that extrême and long-lasting low abundances are needed to provoke détectable réductions of genetic diversity in naturally large populations such as bloaters or lake herrings. Hère, the décline of Lake Ontario C. artedi population started around 1941 and abundances of less than 50 000 fish per year are consistently reported since 1955. The fact that the two most récent samples do not exhibit M ratios characteristic of bottlenecked populations may indicate some recovery or at least, stability of the population size in the last décade or so. In fact, M ratios tend to increase gradually even in reduced but demographically stable populations (Garza and Williamson 2001).

Incidentally, the inadequacy of available tests to detect bottleneck is further suggested by the few significant results obtained in this study. For example, the détection of a bottleneck in Lake Nipigon (NIP-A, Table 1) is unexpected given that Lake Nipigon is the only Great Lake that never supported a commercial ciscoe fishery. While no long-term population data is available for this lake, it seems legitimate to suppose that it has not been disturbed to the same extent as the other lakes. Ail thèse results suggest that the M and HE tests used to detect genetic bottlenecks are far from infallible, and that they should be applied and interpreted very carefully. Indeed, when démographie data are not available, such as is often the case in non-commercial species, severely declining populations may well be identified as not having suffered severe abundance réductions, and the lack of évidence for bottlenecks could mislead conservation décisions.

In relation to the reintroduction of bloaters in Lake Ontario, the lack of évidence for bottlenecks so severe as to significantly affect genetic diversity is a positive finding. Indeed, it appears that the récent evolutionary history of the Great Lakes ciscoes, which involved massive hybridization fostering genetic diversity, as well as the large size and resilience of populations of this long-lived species hâve prevented undesirable diversity érosion. In terms of diversity, then, any one of the Great Lakes is equally fit to provide the reproductive adults needed for reintroducing deepwater ciscoes into Lake Ontario.

Differentiation within and among lakes

Ail analyses coincide with the lack of genetic differentiation within any of the Potential Donor Lakes, the great similarity between bloaters from Lake Huron and Michigan, and the significant genetic differentiation of bloaters from Lake Superior and Lake Nipigon (Figure 3, Table 3). When considered in conjunction with the analyses including ciscoes from Lake Ontario, thèse results provide background information pertinent to the sélection of a source of bloaters for artificial rearing and subséquent reintroduction in Lake Ontario. First of ail, the absence of significant spatial genetic substructure within each PDL indicates that the précise location for collecting C. hoyi in the selected donor lake is not relevant. More importantly, this gênerai resuit suggests that ciscoes recently caught in the deepest section of Lake Ontario likely consist of a remnant, undetected population of bloaters. Indeed, given that sympatric bloaters are not genetically differentiated within any of the PDL, the significant differentiation between deepwater ciscoes and sympatric lake herring suggest that they belong to a différent ciscoe lineage. As hypothesized in the introduction, if the deepwater ciscoes were merely derived from lake herrings having recently recolonized the vacant deeper strata of Lake Ontario, it is unlikely that they would be so significantly differentiated from the récent ancestral stock (FST = 0.062, P < 0.0001). Certainly, the fact that only five deepwater ciscoes were available for genetic analyses could be seen as an important weakness, and we do not deny that more samples would hâve been of great value. However, ail tests with small virtual populations revealed non significant genetic differentiation from the original samples, indicating that a sample of only five individuals was sufficient to detect genetic differentiation. While this interprétation confirms that the original genetic diversity of Lake Ontario bloaters can no longer be recovered, it also indicates a tangible risk of outbreeding

dépression and underlines the importance of choosing a PDL most genetically similar to the Lake Ontario deepwater ciscoes.

Patterns of genetic similarity and assignment analyses indicate that Lake Huron and Lake Michigan represent the best sources for the reintroduction of bloaters in Lake Ontario. Ail analyses indicated that both lakes are equally suitable as sources of bloaters. Indeed, there was no support for genetic differentiation among samples from thèse lakes (Table 3), thèse were most similar and intermingled on the DCE phenogram (Figure 3), and

a Bayesian analysis clearly indicated that a majority of individuals from Lake Huron and Michigan define a cohesive genetic partition (HurMch, Table 5a). In turn, Lake Ontario deepwater ciscoes were ail assigned to this partition or to thèse lakes on the basis of extensive shared ancestry or high assignment scores, respectively (Table 5a, b). With regards to Lake Superior and Lake Nipigon, they defined distinct genetic partitions, and ail samples from thèse lakes were significantly differentiated from the best suited donor lakes. Bloaters from Lake Nipigon were most strongly differentiated from ail the other Great Lakes (Table 3), suggesting that this lake would be the least suited lake to obtain bloaters from. Finally, it is worth noting that ail of thèse results are consistent with previous results indicating that geography is the best predictor of genetic similarity, and that Lake Nipigon belongs to the western group of cisco populations whereas alleles typical of the Atlantic glacial race predominate in ail other Great Lakes (Turgeon and Bernatchez 2003).

Conclusions

This study surveyed patterns of neutral genetic variation in Great Lakes ciscoe populations that are relevant to the future re-introduction of C. hoyi in Lake Ontario. Our results first indicate that bloaters from ail potential donor lakes are genetically very diverse. The absence of genetic signature revealing démographie déclines was rather unexpected given the known fluctuations of commercially-exploited bloater populations during the past century. While suggesting that the available tests may often be unable to detect bottlenecks, thèse results also indicate that the original diversity of huge forage fish populations such as bloaters can prevent the érosion of genetic diversity, even with récurrent periods of abundance below exploitation level. Second, our analyses confirmed that the few available deepwater ciscoes of Lake Ontario likely represent a remnant

population of bloaters, and that thèse are most similar to Lake Huron and Lake Michigan populations. Given that there was no apparent spatial structure within Lake Huron or Lake Michigan, we conclude that bloaters from any location within either lake would be suitable as a source for reintroduction. Thèse recommendations, based solely on genetic criteria, will obviously need to be weighted in light of fish health and logistical considérations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Great Lakes Fishery Commission grant to JT. We would like to thank those who provided samples: Rick Salmon (OMNR), Lloyd Mohr (OMNR), Bruce Morrison (OMNR), Owen Gorman (USGS), and Kim Scribner (Michigan State University).

Figure legend

Figure 1: Sampling locations for Coregonus hoyi in Potential Donor Lakes ( • ) and for ciscoes in Lake Ontario ( • : contemporary and historical scale samples of

Coregonus artedi; ^ : deepwater ciscoes caught in 2002).

Figure 2: Unrooted DcE-based Neighbor-joining phenogram relating ail samples frorn Potential Donor Lakes and Lake Ontario ciscoes (ONT-ARTEDI: récent sample of C. artedi; ONT-DEEP: deepwater ciscoes caught in 2002). Bootstrap values above 60 are shown.

Figure 3: Temporal variation in alielic richness (NAR) and demographical index (M ratio)

in historical ciscoes from Lake Ontario (Hay Bay, Canada) in relation with relative commercial ciscoes catch in the Canadian waters of Lake Ontario (grey bars; Baldwin et al. 2005).

Table 1: Information on ciscoe samples, along with détails on genetic diversity (NA: number of alleles; NAR: allelic richness; Ho and He:

observed and expected heterozygosity, respectively), and results of démographie tests, (P-values for heterozygosity déficit and excess (Cornuet and Luikart 1996); M ratio of Garza and Williamson (2001)).

Code

Sample Information

N type Area

NAR récent NAR temporal Ho He M ratio H déficit H excess

samples (10 loci) séries (8 loci) P-value P-value Hur-A 47 C.hoyi Goderich, CAN 14.3 11.8

Hur-B 48 C. hoyi Lion's Head, CAN 14.3 12 Hammond Bay,

Hur-C 51 C.hoyi USA 16.2 12.9

0.69 0.75 0.76 0.07 0.95 0.72 0.76 0.73 0.25 0.78 0.71 0.77 0.72 0.25 0.78 Mch-A 50 C. hoyi Waukegan, USA 16.4 13.1

Mch-B 48 C.hoyi Beaver Island, USA 13.7 11.8 Frankfurt/Ludington, Mch-C 49 C.hoyi USA ' 14.8 12.3 0.7 0.75 0.76 0.04 0.98 0.71 0.76 0.77 0.50 0.54 0.72 0.75 0.79 0.31 0.72 Stockton/Basswood

Sup-A 50 C.hoyi Islands, USA 13.2 11 Sup-B 34 C.hoyi Thunder Bay, CAN 12 11.6 Sup-C 48 C.hoyi Marquette, USA 13.4 11.3

0.7 0.74 0.69 0.35 0.69 0.74 0.76 0.73 0.46 0.58 0.69 0.74 0.72 0.19 0.84 Nip-A 53 C.hoyi Humboldt, CAN 15.3 12.3

Nip-B 29 C.hoyi The Willows, CAN 11.1 10.9 Nip-C 44 C.hoyi Gros Cap, CAN 14.9 12.4

0.75 0.78 0.63 0.28 0.75 0.78 0.76 0.78 0.62 0.42 0.77 0.78 0.79 0.72 0.31

Sample Information

Code type Area

NA NAR récent NAR temporal Ho He M ratio H déficit H excess samples (10 loci) séries (8 loci) P-value P-value

Ont-deep Ont-artedi 1997 1994 1991 1986 1978 1968 5 51 28 22 24 17 28 25 deepwater ciscoes C. artedi C. artedi ciscoe scales ciscoe scales ciscoe scales ciscoe scales ciscoe scales

Rocky point, CAN 4.5 Hay Bay, CAN 12.8 Hay Bay, CAN 10.8 Hay Bay, CAN 9.8 Hay Bay, CAN 8.3 Hay Bay, CAN 6.4 Hay Bay, CAN 6.9 Hay Bay, CAN 5.9

-6.1 7.3 7.9 6.8 6.1 6.6 5.1 0.64 0.7 0.65 0.57 0.66 0.61 0.63 0.65 0.59 0.71 0.67 0.69 0.68 0.65 0.68 0.62 -0.72 0.83 0.57 0.64 0.70 0.68 0.66 -0.08 0.01 0.13 0.16 0.58 0.68 0.58 -0.94 0.99 0.90 0.88 0.47 0.37 0.47 U )

Table 2: Microsatellite loci used for the characterization of Great Lakes ciscoes: primer séquences with fluorescent label, PCR conditions (primer concentration, TA, and number of cycles), PCR multiplex and migration set, allele size range (bp), and total number of alleles

observed.

Locus Primer séquence (5'-3') Label Primer T°A Multiplex- Allele Total allele

(uM) (N cycles) Migration set size range number cisco-90 * bwf2** cisco-59 *** cisco-181 * cisco-200 * cisco-106 *** $ cisco-126 * cisco-157 * cisco-179 *** cisco-183 *** t F: R: F: R: F: R: F: R: F: R: F: R: F: R: F: R: F: R: F: R: CAGACATGCTCAGGAACTAGf CTCAAGTATTGTAATTGGGTACt CGGATACATCGGCAACCTCTG AGACAGTCCCCAATGAGAAAA AGTTGTGTTAGAGGCACAGC GATAGCTCCCAGGGTTAGTT GGTCTGAATACTTTCCAAATGCAC CCATCCCTTTGCTCTGCC GGTTAGGAGTTAGGGAAAATATG GTTGTGAGGTAGGCCTGG TCGTCGTCAGGTGAACAG GGATTATTTAAAGGCCCAGT GCCAGAGGGGTACTAGGAGTATG GCAGAGAAAGAGCCTGATTGAAC CTTAGATGATGGCTTGGCTCC GGTGCAATCACTCTTACAACACC GTCTGTAAGGGCCTTGTCCAC GTATCATCTATAAGGAGGCAGAGGC TGGCTATATTCGACTACCTTG CCCCATATATCAGAATGAGC 6-FAM PET NED 6-FAM VIC VIC NED VIC PET 6-FAM 0.3 0.3 0.6 0.2 0.6 0.4 0.15 0.2 0.15 0.6 57 (30) 57 (30) 57 (30) 60 (25) 60 (25) 55 (30) 55 (30) 55 (30) 55 (30) 55 (30) 1-1 1-1 1-1 2-1 2-1 3-2 3-2 4-2 4-2 4-2 104-127 146-201 163-248 145-362 154-264 200-286 150-202 129-164 176-210 161-292 9 11 35 52 38 44 7 20 19 46 * Turgeon et al. (1999) ** Patton et al. 1997 *** This paper