AVIS

Ce document a été numérisé par la Division de la gestion des documents et des archives de l’Université de Montréal.

L’auteur a autorisé l’Université de Montréal à reproduire et diffuser, en totalité ou en partie, par quelque moyen que ce soit et sur quelque support que ce soit, et exclusivement à des fins non lucratives d’enseignement et de recherche, des copies de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse.

L’auteur et les coauteurs le cas échéant conservent la propriété du droit d’auteur et des droits moraux qui protègent ce document. Ni la thèse ou le mémoire, ni des extraits substantiels de ce document, ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement reproduits sans l’autorisation de l’auteur.

Afin de se conformer à la Loi canadienne sur la protection des renseignements personnels, quelques formulaires secondaires, coordonnées ou signatures intégrées au texte ont pu être enlevés de ce document. Bien que cela ait pu affecter la pagination, il n’y a aucun contenu manquant.

NOTICE

This document was digitized by the Records Management & Archives Division of Université de Montréal.

The author of this thesis or dissertation has granted a nonexclusive license allowing Université de Montréal to reproduce and publish the document, in part or in whole, and in any format, solely for noncommercial educational and research purposes.

The author and co-authors if applicable retain copyright ownership and moral rights in this document. Neither the whole thesis or dissertation, nor substantial extracts from it, may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author’s permission.

In compliance with the Canadian Privacy Act some supporting forms, contact information or signatures may have been removed from the document. While this may affect the document page count, it does not represent any loss of content from the document.

Impacts des migrations forcées sur les pays hôtes

par

Marna Keita

Département de sciences économiques Faculté des arts et des sciences

Thèse présentée à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l'obtention du gr~de de

,Philosophiae Doctor (Ph.D.) en sciences économiques

Novembre 2007 .

Cette thèse intitulée:

Impacts des migrations forcées sur les pays hôtes

présentée par .

Marna Keita

a été évaluée par un jury composé des personnes suivantes:

Sidartha Gordon président - rapporteur Walter Bossert directeur de recherche André Martens codirecteur de recherche Onur Ozgur membre du jury Jean-Yves Duclos

examinateur externe (Université Laval) Marie Mc Andrew

représentante du doyen de la FES

Cette thèse est composée de trois essais portant sur l'impact des migrations forcées sur les populations hôtes ..

Le premier essai est intitulé: Migrations Forcées, Bien-être des Populations Hôtes, et Resquillage de la Communauté Internationale

Cet essai développe un cadre analytique en vue d'expliquer le comportement de la Com-munauté Internationale lorsqu'un cas de migrations forcées intervient dans un endroit du monde. A travers un modèle simple de planificateur central, nous dérivons les déterminants de la demande privée en réfugiés que l'on pourrait attendre d'un pays humanitaire, si celui-ci n'était pas contraint par les lois internationales. Nous modélisons également la protection des réfugiés comme un bien public international devant être produit sur une base volontaire par l'ensemble des pays du monde, et nous examinons les comportements de resquillage sub-séquents. L'exercice mené aide à mieux comprendre comment le régime de protection des réfugiés qui prévaut au plan international, favorise le manque de solidarité et compromet l'action humanitaire mondiale.

Le second essai est intitulé: Relation de Principal-Agent entre la Communauté Interna-tionale et un pays accueillant un afflux massif de Réfugiés

Dans cet essai nous modélisons les relations entre un pays accueillant un afflux massif de réfugiés et la' communauté internationale comme un problème de type Principal-Agent. Nous déterminons le comportement optimal d'un pays hôte en matière de protection des réfugiés, étant donnés les risques afférents à une telle situation, et étant donné le niveau de soutien reçu de la part de la communauté Internationale. (le UNHCR). Nous établissons que les gouvernements des pays hôtes prennent en compte les caractéristiques des réfugiés reçus pour décider du mode de logement à accorder à ces derniers. Une analyse économétrique . menée par la suite confirme les résultats théoriques trouvés.

Le troisième essai est intitulé: Les afflux massifs de réfugiés ont-ils affecté le bien-être des populations hôtes en Guinée?

dévelop-pées par Duclos, Sanh et Younger pour juger si la présence prolongée d'un nombre important de réfugiés a pu affecter le bien-être des populations locales guinéennes. La Guinée constitue en effet un des plus grands pays contributeurs à l'accueil des réfugiés au monde, du fait des afflux massifs de réfugiés qu'elle a enregistré tout au long des années 90 et au-delà, en raison des violents conflits qui ont éclaté dans certains de ses pays voisins, à savoir le Liberia, la Sierra Leone, et plus tard, la Côte d'Ivoire. La Guinée est divisée en qua~re régions naturelles, et la région forestière est celle qui a abrité la majeure partie des réfugies. En recourrant à trois enquêtes sur les ménages réalisées en 1991, 1994 et 2002, et couvrant la période la plus

\

intense entermes de présence des réfugies en Guinée, nous ex~minons l'évolution du

bien-. \

être dans chacune des régions, et regardons si le schéma observé. en Guinée Forestière est suffisamment différent de celui des autres régions, pour permettre d'envisager un lien entre les spécificités relevées et le choc externe qu'a constitué la présence prolongée des réfugies. Les analyses menées nous font pencher pou~ une réponse affirmative à cette préoccupation. Mots-clés : relations internationales, biens publics, principal-agént, bien-être, analyses multidimensionnelles de la pauvreté, migrations forcées, réfugiés, burden-sharing.

Summary

This thesis consists in three essays on the impact of forced migrations on host countries. The first essay is titled: Forced Migrations, well-being of host populations and free-riding behaviour of the International Community

This essay develops an analytical framework to explain the behaviour of the international community when a case of forced migration occurs somewhere in the world. Through a simple model of a social planner 1 derive the determinants of the private demand for refugees· a humanitarian government would formulate in the absence of international laws. 1 also look at the provision of protection to refugees as an international public good that has to be produced on a voluntary basis by aIl the safe countries in the world, and 1 examine the subsequent free-riding behaviour expressed by the countries. 'The exercise helps in improving our understanding of how the current international regime of refugee protection biases burden sharing and jeopardizes humanitarian action in the world.

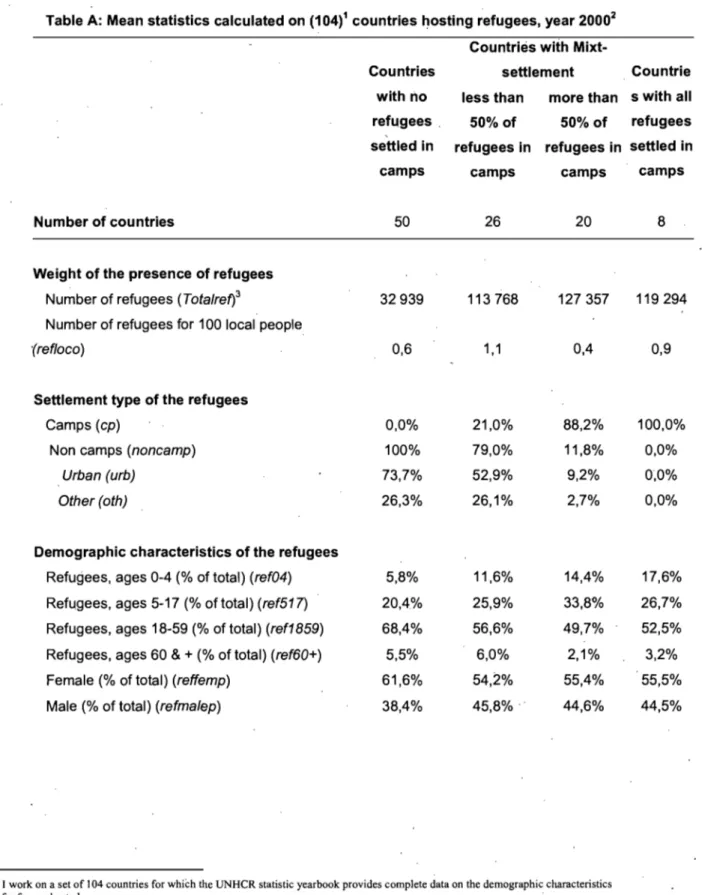

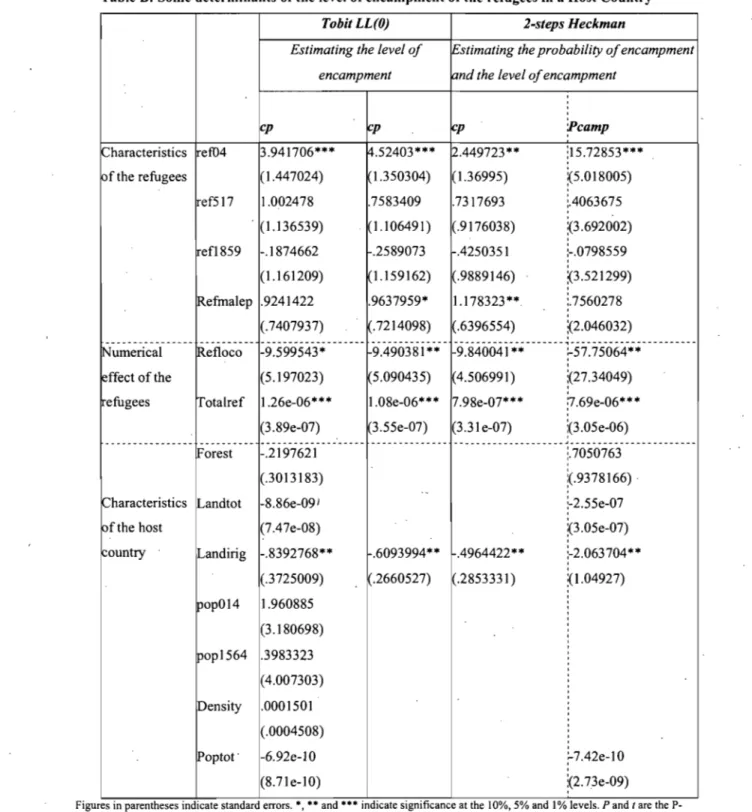

The second essay is titled: A principal-agent relationship between a country hosting refugees and the international corrmmnity

In this essay the relation~hip between a country hosting refugees and the international community is modeled as a principal-agent problem and what might be an optimal behaviour of such a country in terms of refugees protection given the risks inherent ta the situation and given the level of support received from the international community is examined. Next,a regression analysis is performed and the results support the theoretical findings. The essay argues on the basis of both theoretical and èmpirical analysis that host-country governments' choice of refugees' settlement patterns is influenced by the characteristics of the refugees received.

The third essay is titlerl: Didthe long-lasting presence of refugees in Guinea affect the well-being of the host populations?

In this essay, 1 use the methods of robust comparison of poverty and wel1 being deve~oped by Duclos, Sanh and Younger to examine whether the long-lasting presence of a large number of refugees may have altered the' well-being of the host populations in Guinea. Guinea is

indeed among the biggest cOIitributors to refugees hosting in the world, as it recorded several mass influxes of refugees throughout the 1990s and beyond,. due to the civil wars that broke out in sorne of its neighbouring countries, namely Liberia and Sierra Leone, and later on Côte d'Ivoire. Guinea is divided into four natural regions, the forest region being the one which hosted the bulk of the refugees. Using three household surveys carried out in 1991, 1994 and 2002 covering a large part of the duration of the stay of the refugees in Guinea, l examine the evolution of well-being in each region and see whether a link can be made

between the differences in pattern appearing for the forest region and the presence of the refugees. The analysis carried out tends to favour an affirmative answer to this concern.

Keywords : international relations, public goods, principal-Agent, well-being,

multidi-mensional poverty analysis, forced migrations, refuge es , burden sharing.

Contents

Sommaire Summary Dédicace Remerciements Introduction généraleChapter 1: Forced migrations, the well-being of host populations and free-riding behavior of the international community

1. Introduction

2. The Basic Model

3. The protection of refugee1'l as an international public good

3.1 The provision of refugee protection as an international public good when the

i iii xii xiii 1 6 7 13 22

refugees are settled in the first-asylum country (context 1) . . . 24 3.2 The provision of refugee protection as an international public good when the

solution of resettlement in second-asylum countries is colltemplated in a way des cri bed in context 2

3.3 The provision of refugee protection as an international public good.when the solution of resettlement in 'second-asylum countries is contemplated in a way described in context 3 4. Conclusion 5. Appendix

28

30 33 36Chapter' 2: A principal-agent relationship between a country hosting

refugees and the international community 42

1. Introduction 43

2. Sorne basics on the principal-agent model 46

2.1 The principal-agent problem 46

2.2 Holmstrom model (1979) . . 47

2.3 Sorne results on the principal-agent problem ' 49

3. Interactions between the host government and the international agency 51

3.1 The Agent's program . . 55

3.2 The principal's program

4. Empirical analysis 4.1 The data. . ~ .

56

60

61

4.2 The method of estimation 62

4.3 The results . . . 68

,5. Conclusion 69

6. Appendix 70

6.1 Existence of solutions to the programs of the agent and the principal in the

principal-agent problem of section 3 . . . . 70

6.1.1 The agent's pro gram (The agency) 70

6.1.2 The principal's pro gram (the government) 71

Chapter 3: Les afflux massifs de réfugiés ont-ils affecté le bien-être des

1. Introduction 83

2. Quefques' éléments distinctifs de la Guinée Forestière et des autres

régions 87

2.1 Les différences entre la Guinée Forestière et les autres régions en termes d'accueil des réfugiés

2.2 Les différences entre la Guinée Forestière et les autres régions en termes d'initiatives de développement économique et social . . .

2.3 Les différences entre la Guinée Forestière et les autres régions en termes d'atouts naturels . . . .

3. Les données et la méthodologie 3.1 Les données . . . : .. .

3.1.1 La source des données

3.1.2 L'adéquation des données avec l'objectif visé par l'étude 3.2 La méthodologie . . . . 3.2.1 La mesure du bien-être 88 89 91 92 92 92 93

96

96

3.2.2 3.2~3Les méthodes de comparaison robuste du bien-être ou de la pauvreté 99· Les tests de dominance stochastique. . . ... . . . . 108

4. Analyse de l'évolution du bien-être dans les différentes régions de la

Guinée entre 1991 et 2002. 111

4.1 Analyse de l'évolution du bien-être selon quelques statistiques descriptives 112 4.2 Analyse de l'évolution du bien-être à partir des méthodes de comparaison

robuste unidimensionnelle et bidimensionnelle .. 4.2.1 Évolution du bien-être entre 1991 et 1994 . 4.2.2 Évolution du bien-être entre 1994 et 2002 .

113 113 114

5. Discussion: la présence massive et prolongée de réfugiés a-t-elle favorisé une réduction du bien-être en Guinée Forestière? 117

6. Conclusion 122

7. Annexes 125

Conclusion générale 153

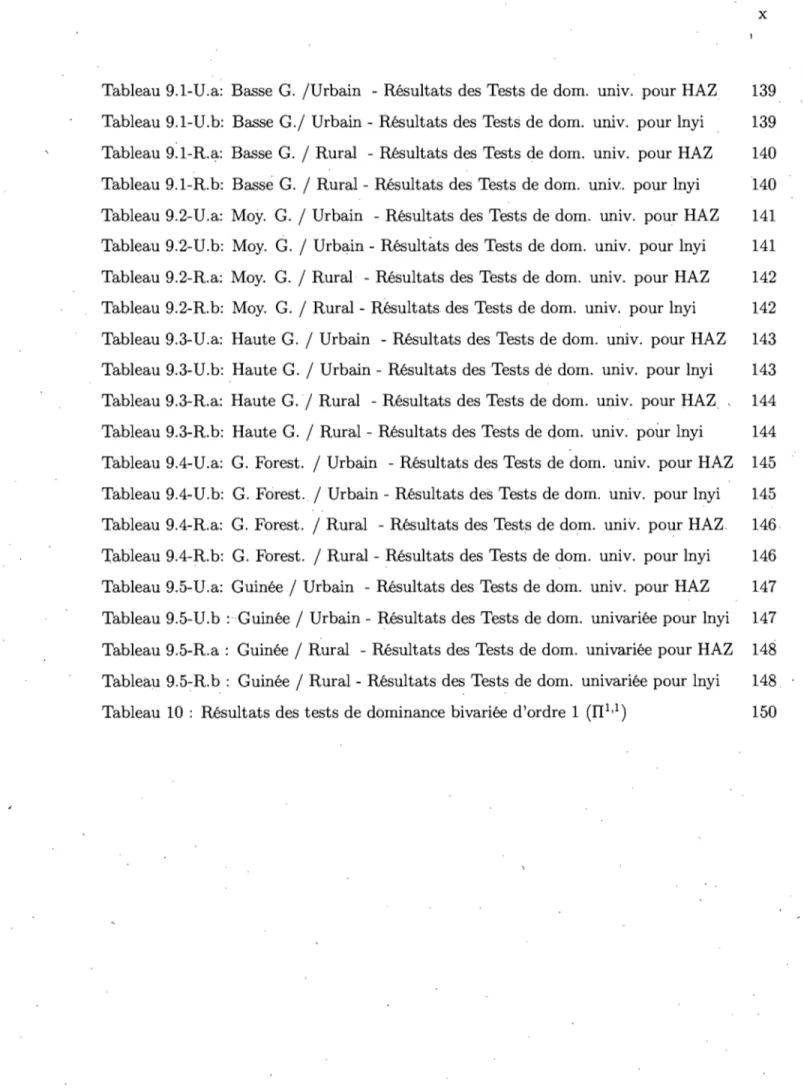

List of Tables

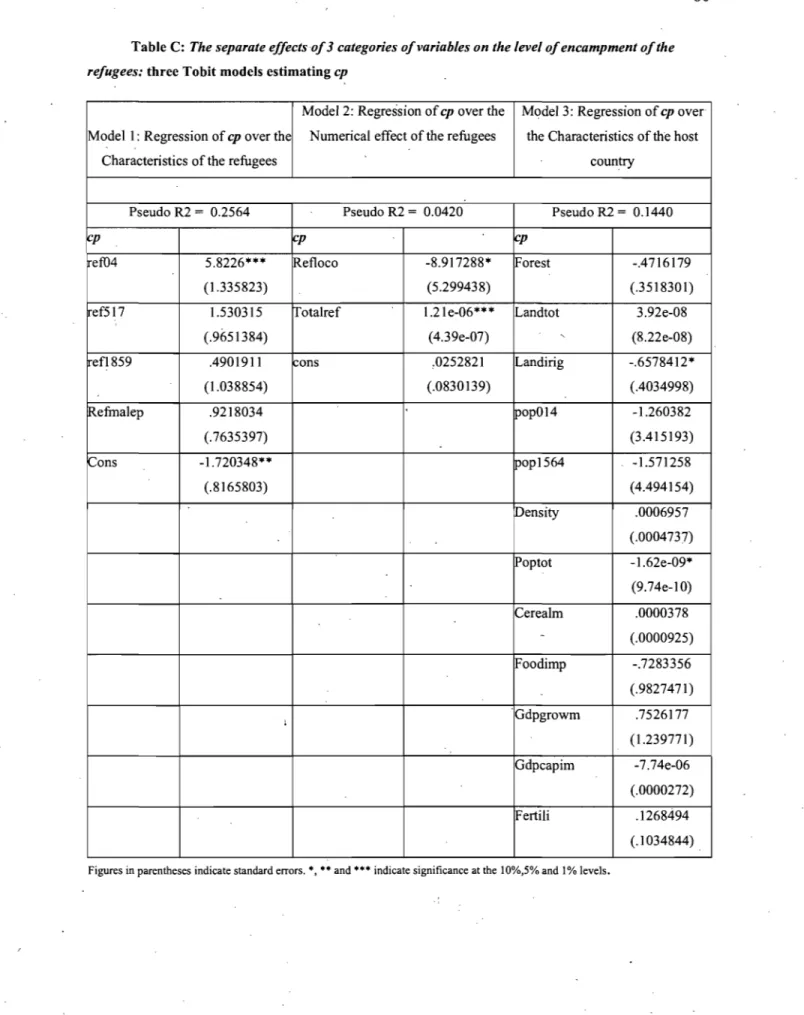

Table A : Mean statistics calculated on 104 countries hosting refugees (year 2000) 65 Table B : Sorne determinents of the level of encampment of the refugees in host

countries 78

Table C : The separate effects of 3 groups of variable on the level of

encampment of the refugees: 3 tobit models estimating 80

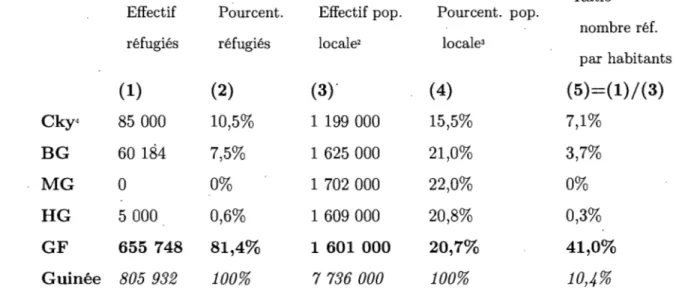

Tableau 1 : Poids numérique des réfugiés en Guinée entre 1991 et 2002 (en millions) 84 'Tableau 2 ': Répartition des réfugiées et des populations locales par région en 1998 88

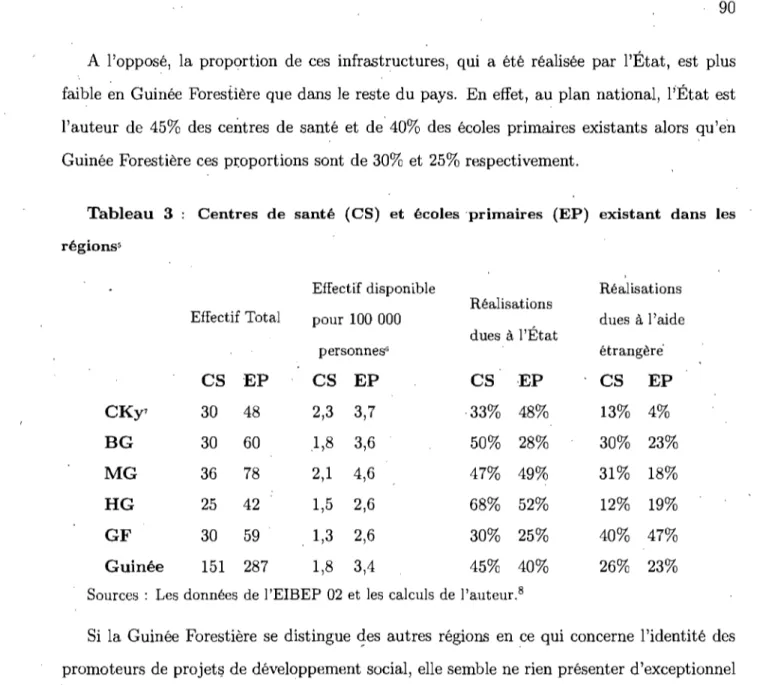

Tableau 3 : Informations sur les centres de santé et écoles primaires existant dans

les différentes régions de la Guinée 89

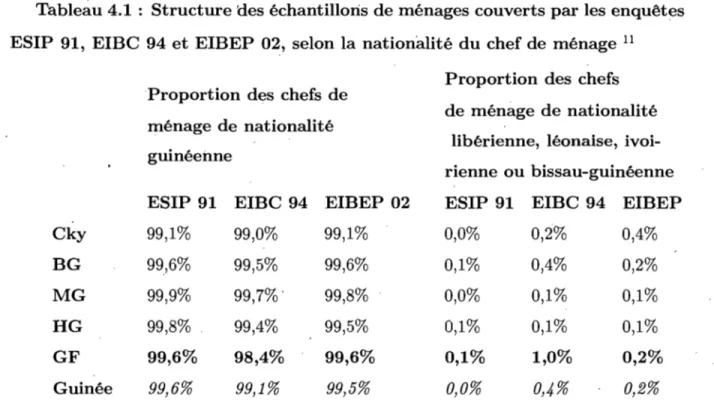

Tableau 4.1 : Structure des échantillon.s de ménages couverts par les enquêtes ESlP 91,

ElBC 94 et ElBEP 02, selon la nationalité du chef de ménage 94

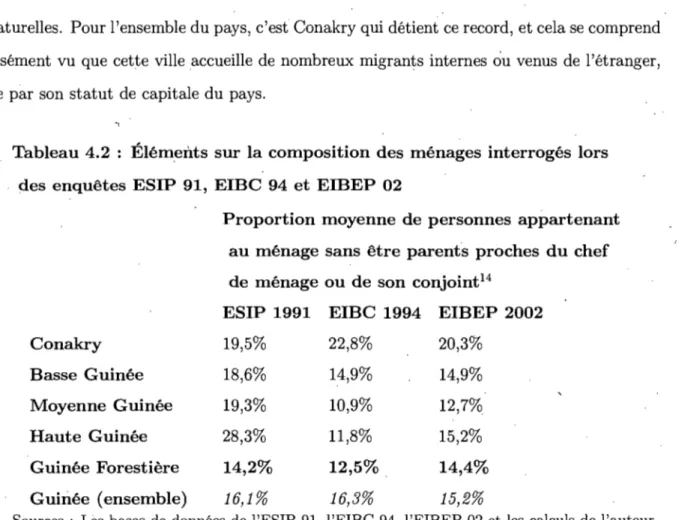

Tableau 4.2 : Éléments sur la composition des ménages interrogés lors des enquêtes 96 ESlP 91, ElBC 94 et EIBEP 02

Tableau 5 : Statistiques descriptives sur la' malnutrition 125

Tableau 6 : Statistiques desc, sur les dépens,es minimales par tête (yi) des ménages 126 Tableau 7 : Synthèse des résultats des tests de dominance pour le bien-être global

et la pauvreté 131

Tableau 8.l.a : Conakry - Résultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour HAZ 133 Tableau 8.1. b : Conakry - Résultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour Inyi 133 Tableau 8.2.a : Basse Guinée - Résultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour HAZ 134 Tableau 8.2.b : Basse Guinée - Résultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour Inyi 134 Tableau 8.3.a : Moy. Guinée - Résultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour HAZ 135 Tableau 8.3. b : Moy. Guinée - R;ésultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour Inyi 135 Tableau 8.4.a : Haute Guinée - Résultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour HAZ 136 .Tableau 8.4.b : Haute Guinée - Résultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour Inyi 136 Tableau 8.5.a : Guinée Forest. - Résultats des Tests de domlnanèe univariée pour HAZ 137 Tableau 8.5.b : Guinée Forest. - Résultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour Inyi 137 Tableau 8.6.,a : Quinée - Résultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour HAZ 138 Tableau 8.6.b : Guinée - Résultats des Tests de dominance univariée pour Inyi 138

Tableau 9.1-U.a: Basse G. /Urbain - Résultats des Tests de dom. UlllV. pour HAZ 139

Tableau 9.1-U.b: Basse

G.j

Urbain - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour lnyi 139 Tableau 9:1-Ra: Basse G. / Rural - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour HAZ 140 Tableau 9.1-Rb: Basse G. / Rural- Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour lnyi 140 Tableau 9.2-U.a: Moy. G. / Urbain - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour HAZ 141 Tableau 9.2-U.b: Moy. G. / Urbain - Résultàts des Tests de dom. univ. pour lnyi 141 Tableau 9.2-Ra: Moy. G. / Rural - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour HAZ 142 Tableau 9.2-Rb: Moy. G. / Rural - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour lnyi 142 Tableau 9.3-U.a: Haute G. / Urbain - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour HAZ 143 Tableau 9.3-U.b: Haute G. / Urbain - Résultats des Tests dé dom. univ. pour lnyi 143 Tableau 9.3-Ra: Haute G./ Rural - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour HAZ 144 Tableau 9.3-Rb: Haute G. / Rural - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour lnyi 144 Tableau 9.4-U.a: G. Forest. / Urbain - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour HAZ 145 Tableau 9.4-U.b: G. Forest. / Urbain - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour lnyi 145 Tableau 9.4-Ra: G. Forest. / Rural - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour HAZ 146 Tableau 9.4-Rb: G. Forest. / Rural - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour lnyi 146 Tableau 9.5-U.a: Guinée / Urbain - Résultats des Tests de dom. univ. pour HAZ 147 Tableau 9.5-U.b : Guinée / Urbain - Résultats des Tests de dom. univariée pour lnyi 147 Tableau 9.5-Ra : Guinée / Rural - Résultats des Tests de dom. univariée pour HAZ 148 Tableau 9.5-Rb : Guinée / Rural- Résultats des Tests de dom. univariée pour lnyi 148. .

List of Figures

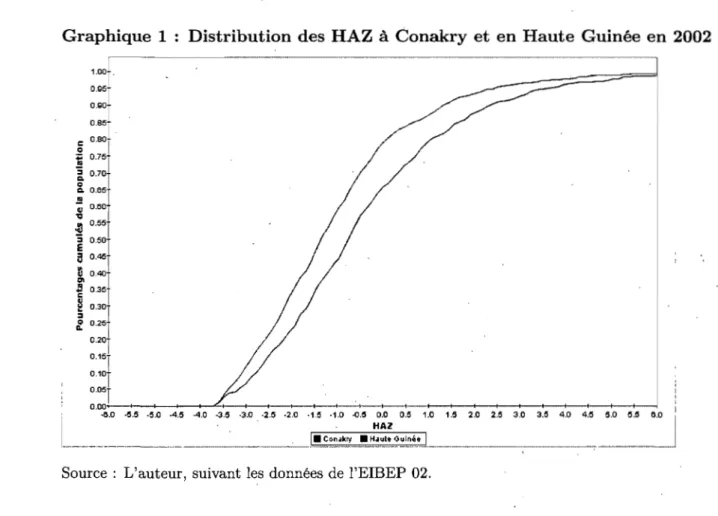

Graphique 1 : Distribution des HAZ à Conakry et en Haute Guinée en 2002 101 Graphique 2 : Distribution dès RAZ à Conakry en 1991 et en 2002 103 Graphique 3 : Frontières de pauvreté d'union, d'intersection ou intermédiaires 107

A

mes parents Seydou Keita et Ramata Gueye, cespersonnes exceptionnelles que je remercie du fond du coeur pour tout;

,à mes frères et soeurs, que je suis tellement heureuse et fière

Remerciements

J'adresse mes sincères et profonds remerciements à mes directeurs de thèse Walter Bossert et André Martens pour leur encadrement, mais aussi pour leur courtoisie indéfectible, leur disponibilité et leur amitié, qui m'ont permis de réaliser ce travail dans une atmosphère conviviale et de le conduire à terme. J'ai beaucoup apprecié de les avoir pour directeurs.

Je remercie le personnel administratif du département de sciences économiques et du ClREQ pouF son soutien continu et son amabililité durant toutes ces années de préparation de ma thèse. Je suis reconnaissante au Département de sciences économiques, au ClREQ, et à Walter Bossert, pour le soutien financier apporté.

Le professeur Claude Monmarquette a bien voulu m'accorder un peu de son temps pré-cieux et m'a fait des commentaires et suggestions tres utiles sur certaines parties de mon travail. Qu'il en soit chaleureusement remercié.

De nombreuses autres personnes ont c6ntribué à faciliter mes travaux de recherche. Parmi elles il y a Mme Bangoura Mame B. Guèyeet ses collègues du bureau du HCR à Nzérékoré qui m'ont permis de visiter des camps de réfugiés et de m'imprégner de la réalité de terrain en ce qui concerne l'accueil des réfugiés. Il y a MM. Aboubacar S. Keita du bureau du HCR

à Conakry et Mory Touré du BCR qui m'ont permis d'accéder à une riche documentation sur les impacts' de la présence des réfugiés en Guinée; il y à M. Mahamadou Touré du bureau du HCR à Tabou en RCl, dont j'ai fait la connaissance à travers le professeur Martens, qui m'a fourni de bonnes informations sur la protection des réfugiés de manière générale. Je leur exprime à tous ma profonde gratitude.

Je dis un grand merci à mon ami de toujours Hervé Lohoues, qui a favorisé mon premier 'contact avec l'Université de Montréal, me permettant de concrétiser mon projet de faire une thèse. Je remercie également mes amis Viorel lordache et Jacques Ewoudou pour leurs commentaires, 'suggestions, et encouragements continuels à poursuivre le travail commencé.

Merci à toute ma famille pour son soutien, sa compréhension et sa confiance en moi, pendant ces années difficiles.

Introduction générale

Cette thèse porte sur l'impact des afflux massifs de réfugiés sur les pays hôtes. Elle

est composée de trois essais et comporte à la fois des analyses théoriques et des analyses

empiriques.

Les mouvements migratoires et en' particùlier les migrations forcées se sont accrus de manière très importante .ces 20 dernières années, à la fois d'un point de vue qualitatif et

d'un point de' vue quantitatif. Selon le Haut Commissariat des Nations Unies pour les

Réfugiés (UNHCR), le nombre de réfugiés et autres personnes d'intérêt pour le UNHCR est

passé de 15 millions en 1990 à 22 millions en 2000 puis à 32,9 millions en 2006.

Comparativement au nombre de 2 millions qui' prévalait en 1950, la situation paraît

inquiétante (UNHCR 2007, IOM 2001).

Leur répartition par région d'asile est très inégale à travers le monde,'la grande majorité

étant située dans Jemonde en développement. En 1994, l'Afrique abritait 46% du nombre

total de réfugiés dans le monde; l'Asie suivait avec une proportion de 35%. L'Europe et

l'Amérique du Nord affichaient respectivement 13% et 5%, tandis que l'Amérique Latine et

l'Océanie avaient les plus petites proportions, soit 0,8% et 0,4%.

A

l'intérieur des régions aussi, la distribution dès réfugiés est très inégale. En Afrique par exemple, plus de la moitiédes 6, 7 millions de réfugiés recensés' en 1994 par le UNHCR était concentrée 'dans seulement

4 pays à savoir: l'ex-Zaïre (26%), la Tanzanie (13%), le Soudan (11%), et la Guinée (8%).

Ces statistiques correspondent à une situation ponctuelle. La durée du séjour est toutefois

un élément important pour évaluer, les coûts de la présence des réfùgiés. Plus cette durée

est longue, plus l'impact de la présence des réfugiés est ressenti par les populations hôtes

(UNHCR, 2002).

De nombreuses différences peuvent également être observées d'un pays d'accueil à l'autre

à la suite d'afflux massifs de réfugiés. Par exemple les caractéristiques socioéconomiques et démographiques des réfugiés sont variables: les pourcentages d'enfants, d'horrimes et de

Les modes d'installation et de logement des réfugiés sont également variables: les réfugiés

peuvent être reçus en zone urbaine ou en zone rurale, ils peuvent être re'groupés dans une

même localité ou dispersés dans plusieurs villes ou villages; ils peuvent être IOpés dans des

camps ou intégrés aux populations locales.

Toutes ces ~ifférences font que l'impact des réfugiés sur les pays d'accueil est susceptible de varier grandement d'un pays à l'autre. Certains pays d'accueil peuvent bénéficier d'une

assistance importante de la part de la communauté internationale; en outre dans certains cas les réfugiés peuvent participer pqsitivement dans l'économie du pays hôte en y augmentant le

niveau qe consommation ou l'offre de travail. À l'opposé, la littérature sur le sujet rapporte de nombreux cas de dommages économiques, sociaux et environnementaux dans les pays hôtes.

Il apparaît donc qu'une présence massive de réfugiés peut avoir aussi bien des effets

bénéfiques que des effets indésirables sur les pays d'accueils. Ainsi, il y a des risques que

l'impact global de cette situation s'avère négatif et ces derniers sont loin d'être négligeables. Au niveau international, la Convention de Genève de 1951 est le document clé qui définit

le ~tatut de réfugié, ainsi que les droits et devoirs afférents. Un réfugié y est défini comme une personne vivant hors de son pays de nationalité, qui ne souhaite pas ou n'est pas en

mesure de retourner chez lui pour des raisons de persécution dues à la race, la religion,

la nationalité, l'appartenance à un groupe social ou à une sensibilité politique spécifiques.

Dans le régime international actuel de protection des réfugiés, les pays d'accueil sont les

premiers garants de la protection des réfugiés, et les 143 parties signataires de la Convention

doivent aider à la réalisation effective de cette protection. L'article 33 de la Convention

définit un engagement très contraignant pour les pays d'accueil, dénommé le principe de

non-refoulement. Ce dernier stipule qu'aucun pays ne doit refouler un réfugié au point de le

renvoyer à des frontières ou dans des territoires où sa vie ou sa liberté serait menacée pour

des raisons liées à sa race, sa religion, sa nationalité, sa sensibilité politique, ou son origine

Deux aspects du régime méritent d'être'soulignés: (i) quelle que soit l'ampleur de l'afflux

les pays hôtes n'ont théoriquement pas d'autre choix que de recevoir tous les réfugiés

re-quérant l'asile; (ii) les autres pays doivent assister les pays d'accueil pour la protect~on des réfugiés.

Par conséquent, il apparaît que le niveau de sacrifice accepté ou supporté par les pays

hôteq est subordonné à la bonne foi et à la détermination des autres pays à intervenir au

plan humanitaire.

Les interactions entre les pays hôtes et les autres pays ont lieu à travers le UNHCR, qui est l'agence des Nations Unies ayant pour mandat d'assurer la protection des personnes

vulnérables au niveau mondial. Pour remplir adéquatement sa mission, cette agence travaille

avec de nombreux partenaires et donateurs, Elle recueille des fonds auprès des gouverne-ments, des fondations et du secteur privé afin d'assister immédiatement les réfugiés dansla

satisfaction de leurs besoins essentiels, dont ceux en nourriture et en logement. A long terme,

le UNHCR peut soit organiser le rapatriement des réfugiés dans leur pays d'origine, soit les aider à s'intégrer dans le pays d'accueil, soit les réinstaller dans un pays tiers dénommé alors

pays de second asile.

,

L'intérêt pour les questions dE:) réfugiés n'est pas récent dans le monde académique. Par

exemple la manière dont les coûts relatifs à la réception et à l'intégration des réfugiés

de-vraient être distribués parmi les pays est un sujet très discuté par les chercheurs depuis au

moins les années 80. Il est généralement abordé à travers la notion de "burden-sharing"

(Fonteyne 1983; Hathaway and Neve 1997; Schuck 1997) .

Plus récemment, les contributions se sont· orientées vers des tentatives de clarifier le 1

concept de burden-sharing lorsqu'il se rapporte aux questions de réfugiés (Suhrke 1998, Betts

2003, Noll 2003); Parmi les courants récents, on note également l'intérêt pour l'impact de la

réception des réfugiés sur les populations hôtes (Graeme 1996, Albernethy 1996, Whitaker

2002).

dernier ordre d'idées. L'objectif principal de cette thèse est d'accroître les connaissances sur

l'impact de l'accueil des réfugiés dans les pays hôtes. Jusqu'à maintenant, l'analyse théorique

des questions de réfugiées a été grandement restreinte à des contributions qualitatives; de

plus la majeure partie de celles-ci est due à des chercheurs en droit, en sciences politiques,

en sociologie, en démographie, en éthique. Nous nous proposons d'innover dans le domaine en introduisant de la formalisation mathématique et le recours à des outils Qffert~ p~r les sciences économiques pour analyser diverses questions relatives à la protection des réfugiés.

Aux plans théorique et empirique, notre contribution se veut donc avant tout de type

conceptuel et méthodologique.

A

ce propos un objectif spécifique recherché est d'offrir un cadre conceptuel logique qui permette de mieux comprendre certains processus de prise de .décision afférents à la protection des réfugiés dans le monde. Un autre objectif est de mettre

en lumière certains effets qu'une présence massive et prolongée de réfugiés peut avoir dans

un pays, et de favoriser la formulation de politiques économiques et sociales appropriées à une telle situation.

Le premier essai est entièrement théorique. Nous y utilisons un modèle simple de

plan-ificateur central, pour analyser les déterminants de la demande privée en réfugiés qu'un

gouvernement humanitaire pourrait exprimer si ses choix ne devaient pas être subordonnés

aux lois internationales. Nous y modélisons également la protection des réfugiés comme un

bien public international et examinons les comportements de resquillages afférents adoptés

)

par la communauté internationale.

Le second essai comporte un volet théorique et un volet empirique. Nous y utilisons·

le modèle de principal-agent pour analyser le processus suivant lequel un pays hôte

déter-mine les modalités de logement qu'il est disposé à accorder aux réfugiées. Une analyse

économétrique est ensuite réalisée, et ses résultats s'avèrent conformes à ceux établis dans

la première partie du chapitre.

Enfin, le troisième essai est totalement empirique: en recourant à des méthodes robustes d~ comparaison des niveaux de bien-être, nous regardons si la Guinée, qui pendant de longues

années a accueilli un nombre important de réfugiés, a enregistré des changements en matière

de distribution du bien-être des populations locales.

Au meilleur de notre connaissance, é'est la première fois que chacun des outils auxquels

Chapter 1

Forced migrations, the well-being of host populations

and free-

ri ding

behavlor of the international

community

Abstract:

This essay develops an analytical framework to explain the behaviour of the international

community when a case of forced migration occurs somewhere in the world. Through a simple

model of a social planner l derive the determinants of the private demand for refugees

a humanitarian government would formulate in the absence of international laws. l also

look at the provision of protection to refugees as an international public good that has to

be produced on a voluntary basis by all the safe coùntries in the world, and l examine the

subsequent free-riding behaviour expressed by the countries. The exercise helps in improving

our understanding of how the current international regime of refugee protection biases burden

sharing and jeopardizes humanitarian action in the wotld.

1.

Introduction

Migration activities and particularly forced migration patterns have changed over the

past decade from the qualitative and quantitative viewpoints. According to the United

Natioris High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the number of refugees in the world

rose from 15 million in 1990 to more than 22 million in 2000. Co~pared to the mere 2 million . refugees counted in 1950, the figure appears worrisome (IOM 2001)1. The distribution of

them by region of asylum is very unequal worldwide. The bulk is located in the developing world. In 1994, Africa was sheltering 46% of the total refugees in the world, followed by

Asia with35%. Europe and North America had respectively 13% and 5%. The proportions

for Latin America and Oceania were the smallest with 0.8% and 0.4% respectively.

Within the regions, the distribution pattern is very different from one country to another as weIl. In Africa, more than half of the 6.7 millions refugees counted by the UNHCR in

1994 were located in only 4 countries: ex Zaire (26%); Tanzania (13%); Sudan (11%) and

Guinea (8%). These statisticspresent the figures at a given time, yet an important element for assessing the "cost" of refugees is the duration of their stay. The longer refugees stay,

the more their impact will be felt by the host society (UNHCR statistical yearbook, 2002). Beside the differences in the distribution of the burden of tefugees among regions and among

countries, differences exist also in other aspects: the socio-demographic characteristiès of

refugees are different from one country to another (percent age of children, of male/female,

percent age by education level reached, etc.); the settlement and the concentration patterns

are different (refugees may be settled in camps or mixed with localpopulations; aIl refugees

may be received in a single locality or dispatched in several places; they may be received in

urban an:ias or in ruràl ones, etc.). Statistics are available about these specificities for most i

of the countries in the UNHCR's statistical yearbooks.

With aIl these differences, the impact of refugees on the receiving countries is likely to

be different from one country to another.

Many cases of important environ mental damages in hosting countries are reported in the literature. On the other hand, sorne host countries may receive a large international assistance at the wake of a mass influx of refuges. Furthermore, the refugees may participate positively in the economy, of the host country as consumers or as producers/workers, and even tax-payers.

An issue that arises then is to determine what is the total impact of the presence of refugees on local populations? To what extent are the native-born affected by the forced migration?

1 think that this issue is of great interest because of the ethical aspect behind it. lndeed in case of negative impacts the right question is: why should an individual of sorne host country suffer more from the forced migration with which he has nothing to do, than would do any individualliving elsewhere in the world?

It sooms that the differences in burden borne by the countries and their citizens in the world in terms of refugee protection is a great deal due to the nature of the prevailing international regime of refugee protection. '

At the international level, the key legal document iIi defining who is a refugee, their rights and the legal obligations of states is the 1951 Convention of Geneva on the Status of Ref1!-gees. A refugoo is defined as a person outside of his or her country of nationality who is unable or unwilling to return because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.

In the current international refugee regime, host governments are primarily responsible for protecting refugees and the (143) partIes to the Convention are expected to carry out its provision. Article 33 of the convention defines' a compelling statement for host countries: the principle of "non-refoulement", the first paragraph of which says:

"No contracting state shaH expel or return a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race,

religion, nationality, membership of a particularsocial group or political opinion". Thus two

features of the regime deserve to be highlighted: (i) the host countries have theoretically no

choice but receive aIl the refugees seeking asylum no matter the extent of the influx (ii) other

countries have to assist it in the protection of the refugees. These two features might explain

partially at least why the costs of protecting refugees in the world are unevenly distributed among the countries: the host countries have the physical presence and face the subsequent

risks (environmental damages, political instability, etc.); the other countries have to help by

sending financial or in-kind support. Thus the burden of the sacrifice accepted by the ho~t countries is submitted to the willingness· of the other countries to help in the humanitarian

field. The interactions between the ho st countries and the other countries take place through the United Nations.

The United Nations' Agency which has the mandate to ensure the protection of the

world's vulnerable people is the UNHCR2 .

The UNHCR's overall mission is to provide operational support and coordination to a wide range of private and public actors who work in the interest of refugees.

The agency does this in several ways. Using the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention as its

. major tool, it ensures the basic human rights of vulnerable persons and that refugees will

not be returned involuntarily to a country where they face persecution. The UNHCR needs

to work with a wide variety of donors and partners to adequately fuI fil its role. It raises

funds through governments,Joundations and private donors so that refugees can be assisted .

immediately with food, shelter and other essentials.

In the longer term, the organization helps civilians repatriate to their homeland, integrate

in countries of asylum or resettle in third countries also called second-asylum countries.

The interest in refugee studies is not new in the academic world. Questions about how

costs related to the reception and the integration of refugees should be distributed among

2The persons of concern to the Agency are mainly refugees, but also other categories of persons in distress like internally displaced people (IDP).

countries are addressed since at least earlier 80's. They are generally tackled through the

notion of "burden-sharing" (Fonteyne 1983; Hathaway and Neve 1997; Schuck 1997). What

is more recent is the theoretical attempts to clarify this concept of burden-sharing for refugee

matters.

'Suhrke (1998) applies for the first time, the theory of public goods to the burden-sharing

debate in refugee protection. She argues that while aIl states have an interest in maintaining

multilateral humanitarian provision to refugE)es, their unilateral incentives to provide are far less as the security threat to individual states is a private cost. Consequently, the overall

refugee regime structure is a public good, characterized by free-riding and a sub-optimal

provision as it is generally the case for public goods. Betts (2003) attempts to identify explicitly the public good inherent in refugee provision along the two properties of

non-excludability and non-rivalry that characterize a public good. He introduces the notion of

joint-products to the burden-sharing debate. The joint-products model implies that rather

than yielding a single non-excludable and non-rivalry benefit, a given good or service will provide multiple benefits which vary in their degree of publicness amongst a given group of

states.

Noll (2003) uses the analytical framework offered by game theory to explain the problems

an international lawmaker is faced with when crafting norms on the sharing of protective

burdens. His paper focuses on risks and their distributions among various actors involved in

case of refugee influx. He says that states seek to diminish sorne risks such as unbalanced

budget, not being re-elected, aggravated social tensions, etc. The game theoretical techniques

allows him to map actors' choices in terms of cooperation and defection in receiving refugees

and participating in the burden-sharing.

So far, the theoretical analysis of refugee issues has, by and large, been restricted to

qualitative assessments; moreover the bulk of the existing contributions are due to researchers

in Law, Politics, Sociology, Demography, Ethics. The main.purpose ofthis paper is to include sorne mathematical formalism in this area by means of suit able tools offered by Economies.

The goal is to get a logical framework that would help to understand better the decision

making process of the different actors involved in the international provision of refugee

protection. The objective is to analyze the impacts of the international regime of refugee

protection and the lack of burden-sharing that characterizes it on the native populations of

the ho st countries.

Two specifie issues are tackled.

(i)- Independently of the internationallaw compelling the host countries to receive and

assist any refugee soliciting asylum, what is actually the optimal number of refugees to admit and what is the optimal level of well-being to provide them with given the socioeconorriic

parameters of a receiving country, the costs refugees might induce~ and the international aid? What are the impacts of those optimal choices for natives? In other words, 1 ànalyze the determinants of the private demand in refugees of a humanitarian country.

(ii)-

If the international provision of refugee protection is actually an international publicgood like Suhrke suggested, what is the exact nature of that good and how is the free-riding

behavior inherent to it expressed bythe actors concerned by its provision?

To address the first issue 1 formulate a simple model where a humanitarian government has to make a decision about the well-being to offer to its citizen, the number of refugees to

accept and the level of assistance to guarantee them, according to the resource constraint of

the country. In the second issue 1 define the public good inherent to the protection of refugees

as th~ provision of well-being to all the refuges. Thus 1 model it as the sum of the utiIities of all the refugees which has to be ensured collectively by all the safe countries in the world, ona

voluntary basis. 1 examine the provision of that good in three distinct contexts inspired each

.from the features of the aétual refugee protection regime. The contributions exp~cted from the countries for the provision of the international public good are different from one context

to another. In the first context, all the refugees are settled in a first-asylum country and the

international community has to ensure their well.:being there. The contribution expected

, from the countries in this context are monetary or in kind grants for the constitution of a .

cornrnon fund for the refugees. In the two àther contexts 1 examine a situation where the

refugees settled in a first-asylum country hàve to be relocated to other countries in or der

to relieve their first hosto In the two contexts the contribution expected from any potential. secçmd-asylum country comprises two aspects: the country has to make a deçision about the

number of refugE;)es to adrilit and it has to determine the level of weIl- being to guarantee· to the refugees it would admit. The difference between those two contexts is that in one case

the refugee protection regime is designed such that each second-asylum country unilaterally

decides on the level of weIl- being to offer to the refugees it will accept and in the other caSe the well-being of the refugees accepted by any second-asylum country is to be ensured by a corrimon fund constituted by aIl the countries taking par~ in the resettlement process.

As for the first issue analyzed in the paper 1 find that the number of refugees to admit increases whith the total resources available to the hostcountry, whether internaI (the GDP)

or external (the international aid); 1 find also that a humanitarian government must be willing

to make great sacrifices in the refugee cause as the optimal level of well-being to provide them· with must be superior to the "net" international aid received. This suggests that

a humanitarian state would be willing to make sacrifice and provlde assistance to asylum

seekers it would receive, yet it would determine the numb'er of people to receive according

to its resource constraint.

ln the second issue the first context examined shows, as expected in the case of volùntary provision of public goods, that each don or country makes it contribution to the asistance

to the refugees settled in the first-asylum country depend on the contributions of the other

don ors such that the overall well-being of the refugees is jeopardized by the free-riding

behavior taking place in this regime of refugee protection. In thé second context, only one

of the two elements constituting the contribution expected from a country is subject to

free-riding, namely 1 the number ofrefugees to take in. In this case a potential second-asylum

country will count on the other participants to admit a large number of refugees but it will

participants. In the last context, it appears that both elements constituting the contributions expected from a country are subject to free-riding behavior: each potential second-asylum country will count on the other participants to admit a large number of refugees and it will count on them too for the constitution of the common fund that must serve to protect the refugees. In aIl the cases it appears that the voluntary basis participations characterizing the refugee protection regime affects the overall number of refugees protected in the world, the level of well-being provided to them, and aIso the living standards of the natives in first-asylum countries.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: section 2 presents the basic model; the three contexts defined to examine the refugee protection as an international public good constitute section 3. Concluding remarks are provided in the last section.

2.

The Basic Model

. The world is composed of several countries and an internationàl agency, say the UNHCR. An internaI conftict occurs in a country

B.

A number nR of its citizens ftee away and become asylum-seekers in the closest country, the country A of nA inhabitants. It is assumed that if an asylum-seeker is not accepted, he dies.The environment in country A which represents a small developing country is described

as

follows.There is a single consumption good denoted CE R+.

Let U : R+ -+ R be an individu al utility function assigning well-being to consumption

levels. 1t is assumed that

U

is twice continuously differentiable on R+ and strongly concave with limU'(C) = 00. Thus for aH C E R+l U'(C)>

0 and UI/(C)<

O. The function isC->O

assumed tohave a constant absolute risk aversion coefficient denoted r = -U"jU'.

The utility functions of asylum seekers are identical to those of individuals in country A This is a plausible assumption as in the developing world, the official borders separating countries are not natural at aIl and were imposed by the colonization. In fact most of the

time, from one part of a border to another, one can find individuals having many things in common, starting with the language.

The local production function is F : R+ ----T R+,whereF(nAlA

+

anBlB) is the amount ofthe good produced with the totallabor supplied by locals and by refugees, nAlA and anBlB

respectively. The two kind of labor are assumed to be perfectly substitut able and the main properties stated for Fare that it is a decreasing return to scale function and concave, that is with the following signs for its derivatives: F'

>

0, Fil<

0; a E [0, 1] represents the proportion of refugees that could take part to the production process.It is assumed that agents are homogenous in terms of consumption and labor within each group.

I now describe in turn the role or the behavior. of the four types of institutional agents interacting in the,country A after the conflict occurring in Country B:the local consumers; the refugees; the government and the international agency.

The local consumers: they are consumers and workers. Their labor supply is assumed

fixed. This is close to the reality if one considers the fact that in developing countries the economy is essentially based upon the agricultural sector, where farmers don't choose their labor supply at the intensive margin. They have no choice but working a lot to survive. The civil servants or the informal sector workers supply usually a fixed amount of labor as weIl.

The refugees: when accepted, they are granted an amount CB of the local consumption

good, and they may be allowed or not to work. This depends usually on whether refugees are settled in town among the native people or in refugee-camps. In the latter case, they are generally subject to restrictions to limit the disturbances they might induce for the host country.

Beside CB refugees may induce other expenses to the government such as for instance,

expenses due to damages caused to the environment or natural resources like forest, soil/land and water sources.

paper of Suhrke (1998) whereby aIl states have an interest in maintaining the multilateral

humanitarian provision of refugee protection3

• Its objective function denoted VA is given by

a weighted sum of utilities of both groups of individuals, the native-born (locals) and the

refugees:

(2.1)

where

CA

and CB are the consumption levels of the locals and the refugees respectively;and ÀA and "XA are the weights attachèd to the weIl-being of locals and refugeès respectively,

with ÀA

+

"XA'=

1, ÀA > 0 ~nd"XA > 04. Gis an increasing function such that G' >0 andG"

~ O. For convenience of notation, sometill).es in the text,U(Ck)

andG(nkU(Ck))

willbe denoted Uk and Gk respectively, for any country k.The government receives from the international agency a subsidy 1 per refugee accepted.

The government has to decide how many refugees nB to accept and what level of con-sumption CB they should receive given the resource constmint of the economy. This means

that the· government behaves as a social planner that aIlocates resources among the two

groups. The government may have to bear other ïnonetary costs due to the presence of .

refugees, like administrative costs, or expenses to prevent or repair the damages they might

cause. Let m deilotes these expenses per refugee:

The international agency: it is humanitarian too and cares for the weIl-being of the

refugees as weIl as the weIl-being in the receiving country. It offers a subsidy 1 per refugee accepted in country A, which enters the buqget coristraint of the government. The subsidy

3The assumption is plausible if one bears in mind that the 1951 Convention of Geneva on r:efugees was . freely signed by 143 countries, committing by that act to take part in the protection of refugees in the world. 4The assumption

AA

> 0 cornes from the assumption whereby .the states are humanitarian. To figure out how country A could be willing to care about the well-being of refugees coming from country E, one could see the two countries as two big families living alongside one another since ever. Then it appears normal that if a bad event occurs and threatens the lives of the members of family E, familly A expresses sorne empathy. Thus depending on the sensitivity of country A the level ofAA

could be high or very small, but it will be strictly positive.is financed from contributions by member countries of the international agency.

1 can now solve the program of the government as a social planner. For the sake of

simplicity, the number of refugees is treated as a continuous variable. The government

\

solves the following problem:

slt

. (2.2)

(2.3)

(2.4)

where (2.3) is the resource constraint of the economy. 1 substitute (2.4) into (2.2) which

becomes a problem depending on.CB and nB only.

First Order Conditions (FOC): 1 assume that ali the conditions are satisfied for interior .

solutions.

FOC in CB for nA, nB

=f.

0 yields:G~U'(CA)

G'sU'(C

B )À

A

ÀA

(2.5)

The FOC in C B says that the government will allocate the consumption good to the locals

and the refugees along the weight it attaches to each group. For instance it may be shown

that ~A

>

"X

A ==? nAêA>

nBêB in the specific case where U(x)=

Inx and G(x)=

Inx5 •The FOC in nB.is:

(2.6)

The FOC in nB says that the government will accept refugees until the well-being derived

by the refugees from this hospitality compensates (or equalizes) the loss of marginal utility

imposed to natives by humanitarian~sm.

5Throughout this chapter, a hat over a variable designates an optimal value of the said variable.

The combinat ion of (2.5) and (2.6) yields:

(2.7)

Proposition 2.1 A necessary condition to find a solution to the government 's program is that the total "internal" costs per refugee CB

+

m must be superior to the total benefit drawnfrom the presence of each, that is aF'

+ [.

Proof: A necessary condition for (2.7) to hold is that its Right Hand Side (RHS) be

positive as it is the case for the Left Hand Side (LHS). That is:

(t8)

•

Proposition 2.1 means that a humanitarian government must be willing to make sacrifices and that the consumption CB to provide the refugees with must be superior to the net

international aid [ - m. In particular, when there is no aid received from abroad

(1

= 0) and when the refugees are not allowed to work or have a very weak productivity (a=

0 orlB = 0) then the receiving country bear aIl alone the entire burden due to the presence of

refugees. This situation is generally bbserved in the first times of the arrivaIs of refugees.

lndeed, in such times the international assistance has not been organized yet, and moreover,

the refugees who had been travelling to escape from a given confiict or disaster are weak and

present a low productivity. Ithas been observed that settling refugees into camps rather

than among-natives has often been preferred by governments (Black 1998), and the contents

of proposition 2.1 sheds sorne light on such a behavior. lndeed, states seek to reduce their

risks, for instance the risk of an unbalanced budget or a risk of social tensions (Noll 2003).

Séttling refugees into camps as soon as they arrive might be seen then as a way for the

government, to protect itself against a too heavy load in terms of damages

(m)

the refugees might cause, as it has to face alone the entire burden entailed by their presence in the first.1 turn now to the determination of the properties of the optimal values for CB, CA 'and

nB. These properties are essentially examined in the case where refugees are not allowed to work that is when they are for instance settled into camps. In this case we hàve 0:

=

O.The properlies of the optimal consumption to ensure to the refugees

Differentiating (2.7) member by member when 0: = 0 yields:

~

U's/U

B- t dCB = - db -

ml

, r

(2.9)

where r

=

-U~/U's>

0 is the absolute risk aversion coefficient assumed to be constant. Then the following properties are established forê

B 6.êB

==

êBb -

m)(-)

(2.10)

Eq. (2.10) says that the optimallevel of CB is such thatit is decreasing in the net

international aid, , - m. This leads to the. following much surprising result:

Proposition 2.2 1.- The optimallevel of consumpti~n or well-being' to pT'0vide to the refugees decreases as the international aid increases , - m. The extent of this variation depends (in-versely) on the absolute risk aversion coefficient.

2. - When refugees are notto parlicipate in the production process

(i.

e. for 0:=

0), theoptimal level of well-being CB to pro vide to them does not depend on the size of the host

population nA nor is it based on the optimal number

nB

of refugees to receive. The onlything that is taken into consideration in its determinatio~ is the net international aid , - m.

3.- When refugees are allowed to work (i.e.

o:i-

O),the optimal level of well-being toprovide them with is inferior to the one wh en they don't work (i.e. 0: =

0).

4.-

When refugees are allowed to iuork (i.e. 0: =1-0)

thenê

B depends on nA through thenature of the production technology used locally (Fil).

Proof: point 1 is established from eq. (2.9). To·see point 2 take Œ= 0 in eq. (2.7). See

pro of for point 3 in appendix. Point 4 is established in appendix through the differentiation

of eq.(2.7) when Œ =1- O .•

Point 1 of the proposition appears surprising at first glance. Yet it seems to stem from

the logic of the government's objective. Indeed, to get the weighted sum of individuals maximized, the government can eithercount on the level of CB or on nB. That is it can

make a trade-off between the quality (of well-being to provide to refugees) and the quantity (of refugees to accept). Then w hen the benefit from refugees is higher, that is w hen the

international aid increases, the optimal behavior of the government is to decrease quality in fayor of quantity. This behavior is understandable on behalf of a humanitarian state. Indeed,

as it cares for the whole people in distress seeking asylum, whenever there js a possibility to

receive more refugees, that is for instance whenever the international aid increases, it will seize the occasion to accept more refugees, even at· the expense of the living standards to

offer them.

,

Point 3 of proposition 2.2 stems from the same logic like the one described above about

the optimal behavior in choosing CB when the benefit from refugees increases. Indeed,

when refugees work, their individual marginal productivity is a benefit for the host country

(see (2.8)). Thus in this case again, the government will prefer quantity to quality: CB

is reduced and n B is iricreased and the government can reach a higher level of satisfaction

(i.e. a higher level of VA)' Many researchers and policy makers plead for the settlement

of refugees among the host population instead of accommodating them into camps, arguing

that they.may bring a benefit to the local community by being workers, consumers, or tax

payers (Kuhlman 1990, Harrel-Bond 1996). The result in point 3 might èxplain why states

facing influx of refugees prefer the solution of encampment to another solution. In effect,

point 3 says that any potential benefit incurred from the refugees is seen as a mean for the

humanitarian government to improve only the humanitarian cause, and not the national or

refugees as econol11ics assets as weIl.

The properties of the optimal number of refugees

vVhen refugees are not allowed to work, that is when a

=

0 eq. (2.3) yields:"

- Cr -

m)

. (2.11)Using then eqs.(2.5) and (2.11), the following properties are established for

nB :

(2.12)

Proposition 2.3 The optimal number of refugees to admit is increased when the size nA and the productivity LA of the host population is larger l(meaning when the GDF is higher),

or when the net international aid 'Y m is larger" or when the solidarity towards refugees

"X

A increases.Proof: the results stem from eq. (2.12) which statements' are established in Appendix. The ·first statement of this proposition is interesting as it confirms the asseSsment of UNHCR that the larger the size of the local population (nA) of a country, the larger its capacity of hosting refugees (nB)' This result might appear non obvious at first glance as a large nA me ans a large pressure from the natives on the resources available for consumption, but it stems from the economic capacity that the size of the local population nA provides to the host country. And this capacity is enhanced when LA is large.

It is interesting to note from the propositions 2.2 and 2.3 that the level of solidarity toward refugees affect the number of refugees to accept but not the level of well-being to provide them with .

. The properties of the optimal consumption of the natives

What is the outcome of the humanitarian behavior of the government in terms of weIl-being of the natives?· The FOC in OB given by eq. (2.5) allows to get an optimallevel

êA

fora

A when a solution has been found for OB.(2.13)

ln the proof of eq. (2.12) in appendix, it is shown that

ê

A depends on bothê

B and nB in'such a way that it increases whith both of them. And that implies that the sense of variation

of

ê

A with respect tor -

m for instance iS'ambiguous as bothê

B and nB depend on thatparameter, yet in an opposite way. Thus the arrivaI of refugees which is materialized by an

international net aid

r -

m might result inli

positive or a negative effect on the well-being of the host populations. Among other things, the out come is related to the form of the functionsU

and G which characterize the preferences of the individuals and the governments. In thespecifie case where the function G is defined such that G(x)

=

x, êAdepends onê

B butnot on nB, and then like

ê

B , it decreases along with the international net aidr -

m. Thisresult suggest that as th~ net benefit drawn from the presence of each refugee increases, a humanitarian government might put its own population at risk by acting in a way that leads

to,the reduction of the well-being of the natives in favor of the humanitarian cause. This kind of behavior may be fine in contexts where the standards of living are high, but in a low

income country it is likely to aggravate the existing situation of poverty.,

At the end of this section, it cornes out that despite the assumption that countries

are humanitarian, which is somehow strong, the net benefit the countries draw from being

humanitarian is

a

determinant of the' number of refugees they take in. This suggests that the humanitarian feature is more expressed in terms of willingness to feed the refugees onceaccepted than in terms of eagerness to take in a large number of refugees. Indeed taking

in a 'large number of refugees requests important resources, whether internaI or external.

This suggests that seeing countries as humanitarian must be done with reàlism, bearing in

mind their concerns for resources constraints and -for, the well-being of their citizens. The

expectations from them in the humanitarian field should be aligned accordingly.

Having stressed the determinants of the countries' involvement in the humanitarian action

refugee protection resting on a voluntary-based participation.

3.

The

protection of

refugees

as an

international public

good

Suhrke (1998) provided an innovative approach by introducing the notion of public goods

into the burden-sharing debate in refugee protection. She argues that while aIl states have an interest in maintaining multilateral humanitarian provision of protection to refugees, their

unilateral incentives to provide are far less as the security threat to individual states is a

pri-vate cost. Consequently, the overan refugee regime structure is a public good, characterized

by free-riding and a sub-optimal provision as it is generally the case for . public goods. Betts

(2003) attempts to identify explicitly the public good inherent in refugee protection along the two properties of non-exdudability and non-rivalry that characterize a public good. He

introduces the notion of joint-products to the burden-sharing debate. My pur pose in this section is to contribute to the identification and the modelling of the public good inherent

to international refugee protection.

1 define the public good inherent to the protection of refugees as the provision of

weIl-being to aIl the refugees. Thus 1 model it as the sum of the utilities of all the refugees which

has to be ensured collectively by aIl the safe countries in the world, on a voluntary basis. 1

examine the provision of that international public good in three distinct contexts, each of

which draws its inspiration from the features of the current refugee protection regime. The

contributions expected from the countries for the provision of the international public good

considered are different from one context to another.

Context 1 for the public good:

ln practice, whena crisis generating refugees occurs, the facts arethat only one (or

few) country is involved in receiving them, namely the first-asylum country which is the