FACULTE DES LETTRES

N

6300.6

UL

T/ (

RENÉ MAGRITTE. A CRITIQUE OF REIFICATION

MICHELINE JÔEMETS

Mémoire présenté pour F obtention

du grade de maître ès arts (M.A.)

ÉCOLE DES GRADUÉS UNIVERSITÉ LAVAL

AVRIL 1991

This essay examines René Magritte’s works from 1925 to 1933. It posits that Magritte’s paintings underwent two distinct stages of resistance to commodity relations, one around 1925-1927, the other starting in 1933 with the development of a work process known as

objet-réponse.

It suggests that the two stages of resistance to commodity relations were founded on opposite modes of construction. The works dating from the early years are understood as being the result of a constant effort to negate the structural principles of the 'organic’ work of art, while the works dating from 1933, are understood as aiming for the creation of a new value system, one which transcends the rational and quantitative norms imposed by reified society.Cet ouvrage examine les oeuvres de René Magritte datant de 1925 à 1933. L’auteur considère les oeuvres crées au cours de ces années comme appartenant à deux moments distincts d’un même cheminement critique des relations marchandes. Le premier moment est situé de 1925 à 1927, le second en 1933, au seuil de la découverte d’un processus de formation d’images appelé "objet- réponse". Ces deux périodes sont considérées comme étant basées sur des modes de construction opposés. Les oeuvres datant de la première période sont perçues comme étant le résultat d’une volonté de nier les principes structurels de l’oeuvre "organique". Les oeuvres construites d’après le modèle de T objet- réponse sont, quant à elles, interprétées en tant que tentative de transcender les limites strictement quantitatives et rationelles imposées à tout objet par les rapports marchands. Cette poursuite vers un dépassement de la valeur d’échange s’établit grâce à la construction de liens et d’images qui débordent toutes considérations pratiques.

Signatures: Micheline Jôemets, Elliott Moore; _

I would like to thank all those who have given me their support during the time of research leading up to the completion of this work:

Elliott Moore,

Mariette G arceau and Elmar Jôemets, Viivi Jôemets and Pierre Jôemets, Valérie Perrault and Barry Holms, Jacinta Ferrari and Calvin Meiklejohn, Angèle Boulay

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SUMMARY ...I TABLE OF CONTENTS ... Ill LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS... V

INTRODUCTION ... 1

I. MAGRITTE, 1925 TO 1927 ...4

Jeune fille ayant une rose à la place du coeur

...4Le Jockey perdu

... 8The organic and non organic work of art... 12

The 1927 show... 18

A neutral style ... 20

The use of space... 22

Collages ... 26

The notion of space: Magritte and Brecht...28

Le retour à l’ordre

and Magritte’s destruction of spatial and semantic unity... 31A reaction to modernism...38

H. THE YEARS 1928 TO 1930 ... 44

A move to Paris ... 44

A shift in tension from space to objects... 47

Vague figures have a meaning as necessary and

perfect as precise ones

... 49A word can take the place of an object in reality

.... 51The irrational combination of objects as a criticism of reification... 52

a) Lukâcs’ theory of reification... 53

The construction of an image through negation ... 57

HI. THE DISCOVERY OF THE

OBJET-RÉPONSE -

1933 . . 61Les Affinités électives

... 61Les Vacances de Hegel

... 63The two versions... 66

The relationship between title and work...68

Use value, exchange value, poetic value...71

The objects ...74

Isolation as a means of intensifying effect...75

Détournement

...76The

objet-réponse

as a form ofdétournement

... 79The inclusion of space in the formation of

objet-réponse

... 83La Condition humaine

. ... 84CONCLUSION... 89

BIBLIOGRAPHY...i

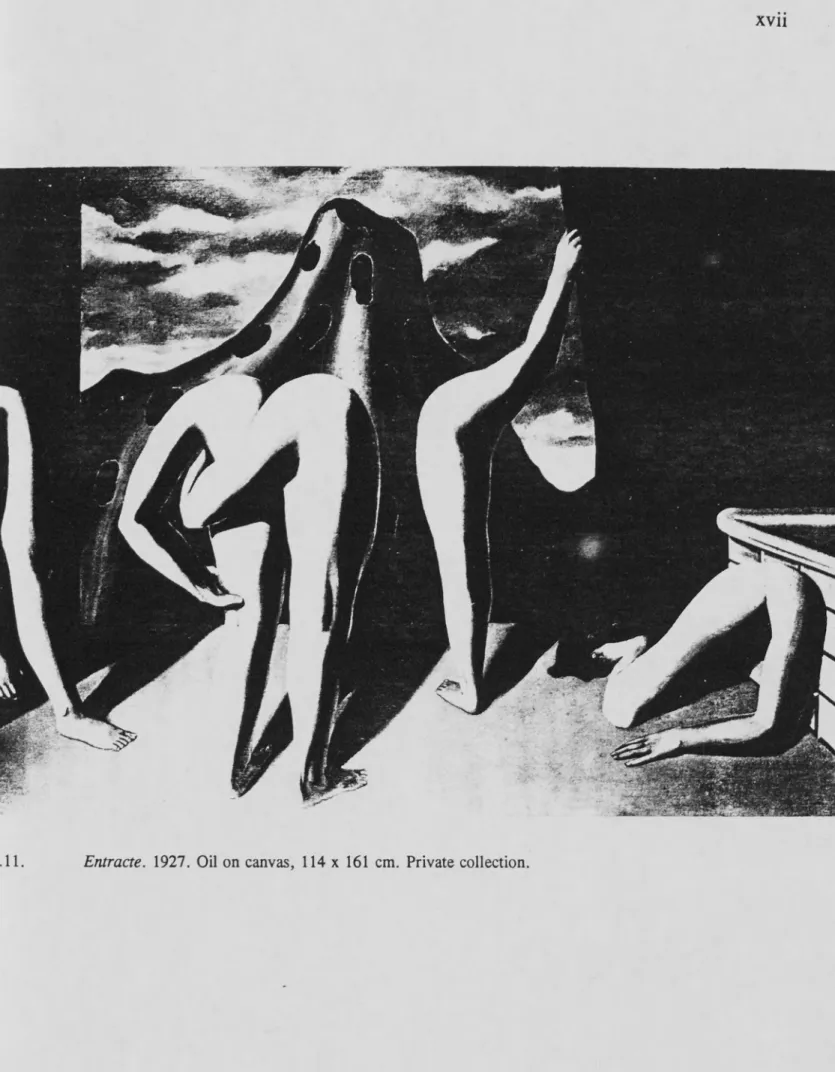

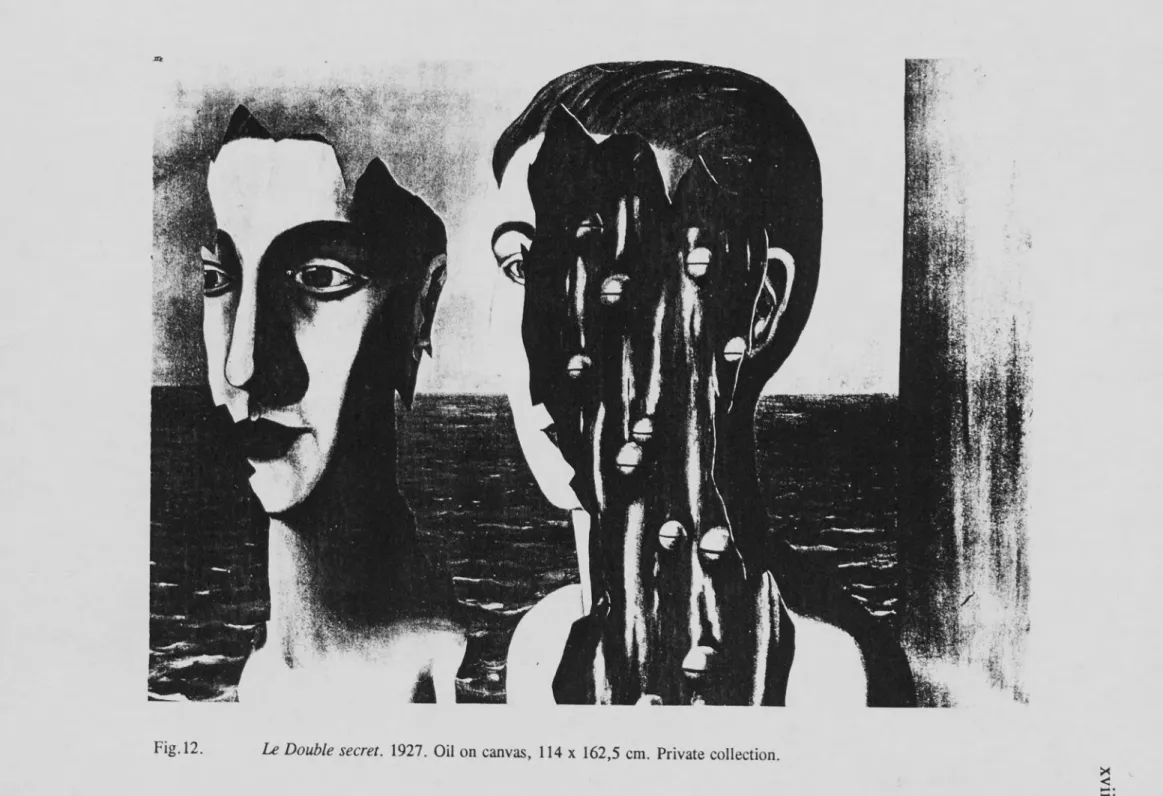

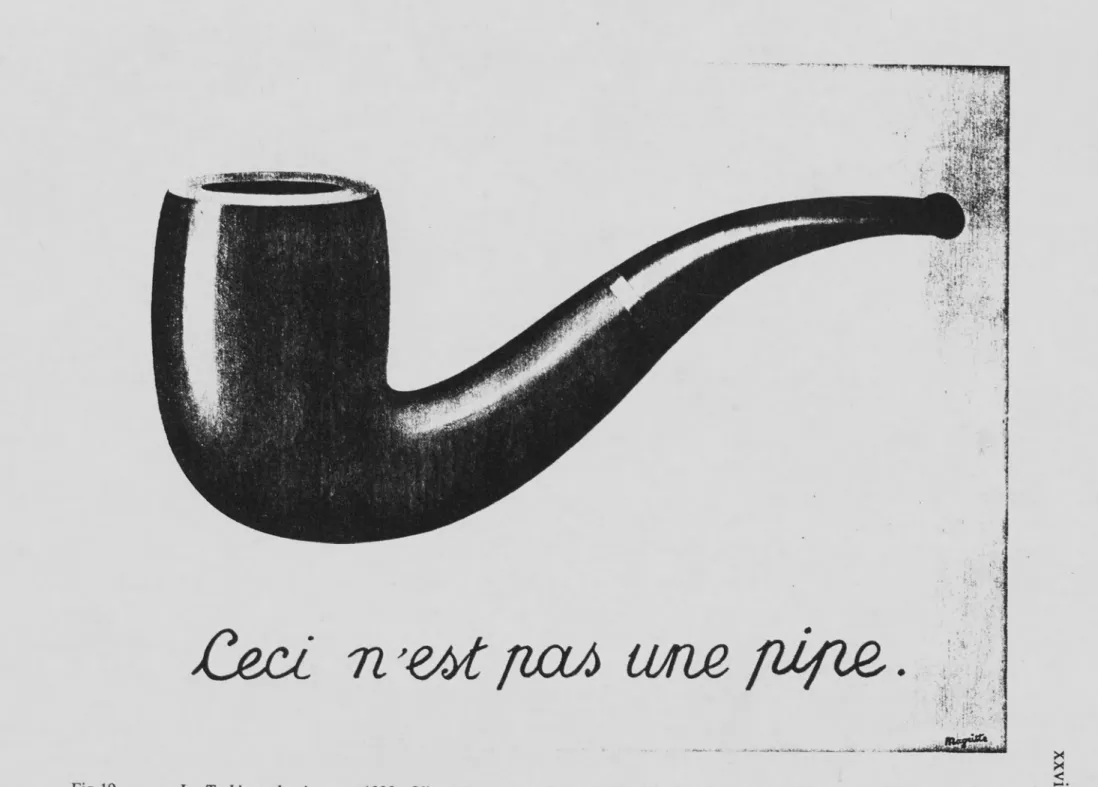

Fig. 1. Fig. 2. Fig. 3. Fig. 4. Fig. 5. Fig. 6. Fig. 7. Fig. 8. Fig. 9. Fig. 10. Fig. 11. Fig. 12. Fig. 13. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Jeune fille ayant une rose à la place du coeur.

1924. Oil on canvas, 55 x 40 cm. Mrs Magritte collection.Le Jockey perdu.

1926. Oil on canvas, 63,5 x 73,5 cm. Mrs. R. Michel collection.Femmes.

1922. Oil on canvas, 70,2 x 100,2 cm. Private collection.Femmes.

1923. Oil on canvas, 100 x 70 cm. Private collection.La Traversée difficile.

1926. Oil on canvas, 80 x 65,3 cm. Private collection.Le Supplice de la vestale.

1926-1927. Oil on canvas, 97,5 x 74,5 cm. Isy Brachot Gallery, Brussels-Paris.Le Jockey perdu.

1926. Paper, wash, ink, 39,5 x 60 cm. Harry Torczyner collection, New YorkUntitled. 1926. Paper, wash, ink, 55 x 40 cm. Private collection. Untitled. 1926. Paper, wash, ink, 40 x 55,5 cm. Private collection.

Le Groupe silencieux.

1926. Oil on canvas, 120 x 80 cm. Isy Brachot Gallery, Brussels-Paris.Entracte.

1927. Oil on canvas, 114 x 161 cm. Private collection.Le Double secret.

1927. Oil on canvas, 114 x 162,5 cm. Privatecollection.

Les Mots et les images.

La révolution surréaliste. Paris, n° 12-15, 1929, p 32-33.VI

Fig. 14.

La Sortie de l’école.

1927. Oil on canvas, 75 x 100 cm. Claude Spaak collection.Fig. 15.

Le Sens propre.

1928-1929. Oil on canvas, 73 x 54 cm. Robert Rauschenberg collection, New York.Fig. 16.

Le Corps bleu.

1928-1929. Oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm. Mr. & Mrs. Orvalet collection, Brussels.Fig. 17.

Le Miroir vivant.

1926. Oil on canvas, 54 x 73 cm. Mrs Sonabend-Binder collection, Brussels.Fig. 18.

L’Usage de la parole.

1928. Oil on canvas, 54 x 73 cm. Rudolf Zwimer Gallery, Kôln.Fig. 19.

La Trahison des images.

1929. Oil on canvas, 62,2 x 81 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.Fig. 20.

Les Affinités électives.

1933-1934. Oil on canvas, 41 x 33 cm. Etienne Périer collection, Paris.Fig. 21.

Les Vacances de Hegel.

1958. Oil on canvas, 60 x 50 cm. Isy Brachot Gallery, Brussels-Paris.Fig. 22.

Les Vacances de Hegel.

1959. Oil on canvas, 48 x 38 cm. Private collection.Fig. 23.

Le Modèle rouge.

1935. Oil on canvas, 55,9 x 45,8 cm. Collection Musée National d’Art Moderne; Centre National d’Art et Culture Georges Pompidou, Paris.Fig. 24. Letter written by René Magritte to Suzi Gablik, May 19, 1958. Fig. 25.

Le Mariage de minuit.

1926-1927. Oil on canvas, 139,5 x 105,5cm. Musées Royaux des beaux-arts de Belgique, Brussels.

Fig. 26.

La Réponse imprévue.

1933. Oil on canvas, 82 x 54,5 cm. Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels.vn

Fig. 27.

La Condition humaine.

1934. Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm. Private collection, Paris.Fig. 28.

Le Chant de Corage.

1937. Oil on canvas, 66,2 x 54,9 cm. Scottish National Gallery of Art.Fig. 29.

L’Empire des lumières.

1954. Oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm. Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels.1 INTRODUCTION

In this text I propose an interpretation of René Magritte’s works as a criticism of reification. Reification is the concretization of inter-human relations into materially definable instances and thence into commodities. Georg Lukâcs defined reification as follows:

Its basis is that a relation between people takes on the character of a thing and thus acquires a "phantom objectivity," an autonomy that seems so strictly rational and all-embracing as to conceal every trace of its fundamental nature: the relation between people.1

As a direct consequence of the division of labour and of specific dominant relations regulating the work force in the interest of a ruling class, a perfectly closed and quantitative system developed under capitalism which, by the end of World War I, had led to an extreme segmentation of life and had reduced it to a series of commercial transactions. The fundamental social relations which were at the heart of the production process had been transformed and distorted into relations between objects and goods, thereby obliterating their social origin. Commodity relations had, by this time, become the universal category of society as a whole and they began to permeate all spheres of human activity. René Magritte (1898-1967) was a member of the Belgian surrealist movement. I believe that Magritte’s works underwent two distinct stages of resistance to commodity relations, one around 1925-1927 and the other starting in 1933 with the development of a work process known as

objet-réponse.

I will attempt togive a detailed account of the ways in which both of these stages could, at the same time, propose a criticism of reification and differ significantly from one another in their critical approaches. It will further be suggested that the two stages of resistance to commodity relations were actually founded on opposite modes of construction.

I will attempt to demonstrate that the works produced in the 1925-1927 period were the result of a constant effort to negate the very notion of the "work of art" and that this attitude expressed itself, in part, through a conflictive representation of space.

Peter Bürger understands the development of the non organic work of art (a term which he uses to define the works produced by the historical avant-garde movements) as a moment in which art enters into self-criticism. For him, the non organic work of art developed in reaction to the autonomous and socially irrelevant status which characterized the institution of art in late modernism.

I will suggest that Bürger’s analysis of the non organic work of art can indeed serve as a basic theme with which it may be possible to approach the kind of negative processes observed in Magritte’s works of the 1925-1927 period. I

I will also argue that the works dating from 1933 were based on a constructive principle. Starting in 1928, the conflict and tension observed in the representation of space will be abandoned or rather transposed onto the representation of objects. The year 1933 will appear as the beginning of Magritte’s constructive work process known as

objet-réponse.

3

It is my view that the construction principle upon which the

objet-réponse

depends implies an active resistance to the hegemonic commodity relations. In the initial part of the third chapter, I will attempt to demonstrate that by constructing images based on the complex and poetically expressive unification of two unrelated objects, Magritte refused to adhere to an externally defined exchange value. Instead, he proposed to transcend this purely quantitative attitude through the creation of a new value system based on poetic expression. If, by creating this new value system, which I define as poetic, Magritte can be said to distance his image from the concept of exchange value, it must also be observed that this criticism of reification is nevertheless restricted to the artistic sphere. In the subsequent part of the third chapter, I will compare the activity of the Situationist International and Magritte’s construction of anobjet-réponse

in order to demonstrate how, given similar goals, Magritte’s criticism remained nonetheless isolated within a specialized form of expression.As a final note, I will also attempt to demonstrate that the changes observed in Magritte’s evolution from a destructive to a constructive approach can actually be traced back to specific historical developments in the evolution of the surrealist movement.

La révolte contre le monde actuel signifie le refus de participer volontairement à l’activité de ce monde qui est au pouvoir de voyous et d’imbéciles. Elle signifie également la volonté d’agir contre ce monde et la recherche des moyens de le faire changer.

René Magritte, "La révolte en question",

Le Soleil Noir, Paris, 1952.

Jeune fille avant une rose à la place du coeur

Magritte arrived in Brussels in the middle of the First World War (1916) at the age of 18. He entered

VAcadémie des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles

that year and remained there until 1918. It is in 1919 that he was first introduced to cubism and futurism. This first contact with the Italian movement occurred through a catalogue. Although Magritte never specified the source of this catalogue, it has been suggested that the exhibition to which it referred was theGrande Esposizi-

one nationale futurista

held in Milan in 1919, the preface to which had beenwritten by Marinetti.2 For Magritte, the exposure to this movement sparked the beginning of a series of futurist experiments which lasted until 1925.

In 1924 Magritte painted

Jeune fille ayant une rose à la place du coeur

(fig. 1). This painting depicts a young woman, nude but for stockings, leaning on the comer of a table in an otherwise empty room with no visible windows or doors. A drawn curtain is in the foreground, on the right side of the work. The figure is composed of flat uniform sections with little specific details. The featureless head is represented in profile. The hands, where they are not partially hidden, are represented as fiat curved forms. In the lower part of the body the curves and volumes are lightly modeled by chiaroscuro. Some parts of the upper body (arms, breast) are segmented by the opposition of tonal planes. Different shades of orange, brown, and yellow are used across the entire surface. With the exception of the floor and the stockings, which are respectively rendered in dark brown and black, the same limited palette is used for figure, room, table, walls, and curtains. In fact, the dark tones which define both the floor and the stockings isolate these areas from the rest of the image, particularly in the case of the floor, which can thereby be read both as part of the room and as an independent vertical plane serving as a partial background to the figure. A rose is painted below the woman’s right breast in a nuance of pink that highlights it against the otherwise drab surface.In a text written in 1938, "Ligne de Vie I", Magritte described the years leading to 1925 as a period characterized by an abstract vision of the world. It was

5

towards the end of this period, recalled Magritte, that he gradually awakened to the connections existing between the abstract style of his early futurist works and the abstract way that he perceived the world. He recollected how, for example, detailed and nuanced sceneries would suddenly appear to him as flat and void of any physical distance and depth, as if curtains had been placed before his eyes.3 He qualified this state as one of complete innocence, similar to that of a child mistakenly attempting to grasp objects situated beyond his reach. Referring to his futurist works, Magritte says:

Je fis alors des tableaux représentant des objets immobiles, dépouillés de leurs détails et de leurs particularités essentielles. Ces objets ne révélaient au regard que l’essentiel d’eux-mêmes et par opposition à l’image que nous voyons d’eux dans la vie réelle, où ils sont concrets, l’image peinte signifiait un sentiment très vif d’une existence abstraite.

Or, cette opposition fut réduite; je finis par trouver dans l’apparence du monde réel lui-même la même abstraction que dans les tableaux; car malgré les combinaisons compliquées de détails et de nuances d’un paysage réel, je pouvais le voir comme s’il n’était qu’un rideau placé devant mes yeux. Je devins peu certain de la profondeur des campagnes, très peu persuadé de l’éloignement du bleu léger de l’horizon, l’expérience immédiate le situant simplement à la hauteur de mes yeux.

J’étais dans le même état d’innocence que l’enfant qui croit pouvoir saisir de son berceau l’oiseau qui vole dans le ciel.4

In his book

The Society of Spectacle,

Guy Debord comments on the degree of abstraction and alienation endured by men in advanced capitalism. He says:3 Magritte, p. 106.

7

Toute la vie des sociétés dans lesquelles régnent les conditions modernes de production s’annonce comme une immense accumulation de spectacle. Tout ce qui est directement vécu s’est éloigné dans une représentation.5

Le concept de spectacle unifie et explique une grande diversité de phénomènes apparents. Leurs diversités et contrastes sont les apparences de cette apparence organisée socialement, qui doit être elle- même reconnue dans sa vérité générale considéré selon ses propres termes, le spectacle est l’affirmation de l’apparence et l’affirmation de toute vie humaine, c’est-à-dire sociale, comme simple apparence. Mais la critique qui atteint la vérité du spectacle le découvre comme la négation visible de la vie; comme une négation de la vie qui est devenue visible.6

In 1925 Magritte decided to break away from what he considered a passive attitude in order to adopt a more active stance towards reality in the hope of transforming life.

En trouvant la même volonté, avec, en plus, une méthode et une doctrine supérieures, dans les ouvrages de Karl Marx et de Frederic Engels, et en faisant vers la même époque la connaissance des Surréalistes qui manifestaient avec violence leur dégoût pour toutes les valeurs bourgeoises, idéologiques et sociales qui retiennent le monde dans ses ignobles conditions actuelles, j’acquis la certitude qu’il me faudrait vivre avec le danger, pour que le monde, que la vie répondent davantage à la pensée, aux sentiments.7

Magritte associated his change of attitude to an intense emotional experience he had in a pub in Brussels one evening in 1925. He recalled being terrified by

5 Guy Debord, La Société du spectacle, (Paris, Editions Gérard Lebovici, 1987), p. 11. 6 Debord, p. 12.

the mystery with which the mouldings of a door seemed to have been invested8. This encounter triggered his departure from an abstract mode to one imbued with a greater power of confrontation. Speaking of this transitory period, Magritte says:

Par la suite, j’introduis dans mes tableaux des éléments avec tous les détails qu’ils nous montrent dans la réalité et je vis bientôt que ces éléments, représentés de cette façon mettaient directement en cause leurs répondants du monde réel.9

Le Jockey perdu

In late 1925 to early 1926, Magritte painted

Le Jockey perdu

(fig. 2). This work depicts an outdoor scene, structured around two intersecting alleyways. A frontal view is given onto the intersection of the two perpendicular alleys. One is shown sharply receding to a centrally located point on the horizon, while the other runs the length of the canvas. A racing horse mounted by a jockey occupies the foreground of the picture, at the intersection point of the two alleys. The composition is such that the head of the jockey directly overlaps the perspective point. The trees bordering the alleys have been metamorphosed into a combination ofbilboquets

and tree branches. Thebilboquets

serve as tree8 "En 1925, je pris la décision de rompre avec cette attitude passive à la suite précisément d’une contemplation intolérable que j’eus dans une brasserie populaire de Bruxelles : les moulures d’une porte me parurent douées d’une mystérieuse existence et je fus longtemps en contact avec leur réalité. Un sentiment voisin de la terreur fut le point de départ d’une volonté d’action sur le réel, de transformation de la vie." Magritte, pp. 142-143.

9

trunks to the few branches which sprout out of their upper parts. A dark drawn- back curtain is painted on the right side of the scene.

Before we begin to compare these two works, we must first specify that the 1924 painting differed from earlier futurist works insofar as it announced a shift in interest towards the representation of objects. As can be witnessed in two paintings dating from 1922 and 1923 both entitled

Femmes

(figs. 3 & 4), the works preceding the creation ofJeune fille ayant une rose à la place du coeur

were more strictly limited to the study of the decomposition of human forms.Jeune fille ayant une rose à la place du coeur

is distinguishable itself from earlier futurist works in that it represents Magritte’s first attempt at submitting an object to a specific procedure (in this case substitution). The necessity of describing the substitution procedure in the title of the work, where formerly Magritte had either altogether omitted to propose a title or had only given a general one word title such asFemmes

to his futurist paintings, points to the importance and the novelty of this new procedure.If the link between the heart (inside the chest) and the rose (outside of the chest) can be more or less described in terms of substitution, the nature of links between objects in subsequent paintings will not only multiply but will also become more complex. As a result, any attempt to give a one- or two-word definition to the procedure involved in subsequent works will become problematic. Given these difficulties, René Passeron and Suzi Gablik have nevertheless both attempted to reduce Magritte’s rhetoric to a calculable number

of procedures. René Passeron has been able to denote a total of five procedures, while Suzi Gablik, for her part, has found eight.10

If we continue our comparison of the two paintings, we notice that the impact created by the substitution of one object for another (i.e., a rose for a heart) noted in

Jeune fille ayant une rose à la place du coeur

is, inLe Jockey perdu

, extended to new limits. In order to examine this point more closely, let us look at what Bürger has called "the traditional unity of the work" or "the unity of the universal and the particular. "In

Ligne de Vie I

Magritte described the motivation for substituting a rose for a heart. This procedure, said Magritte, was prompted by a desire to create a "shattering"(bouleversant)

effect on the overall perception of the painting11. In a further note on this work, he commented on the disappointing effects produced by the final image: "La rose que je mis dans la poitrine d’une jeune fille nue ne produisit pas l’effet bouleversant que j’attendais."1210 René Passeron notes that five basic procedures have been used by Magritte over the years. The first procedure is one of physical contradiction, as between the extremes of heavy and light, animal and vegetal, day and night. The second procedure is one of logical displacement or metonymy. Such is the case with the substitution of the egg for the bird. The third procedure noted is that of an aberrant superposition. Such would be the case with the apple substituted for a human face. The fourth is qualified as a process of reification. Here the author has in mind the examples of the flesh turning to wood or to rock. Finally, the fifth procedure is defined as one of the "absolute enigmatic". Here an enigma is proposed which cannot yield sense.

Suzi Gablik proposes eight categories as follows : (1) isolation, (2) modification, (3) hybridization, (4) a change in scale, position or substance, (5) the provocation of accidental encounters, (6) the double image as visual pun, (7) paradox, (8) conceptual bipolarity.

11 Magritte, p. 107.

11

Indeed, it can be observed that the substitution procedure initiated in

Jeune fille

ayant une rose à la place du coeur

does not shatter the stability and coherence of the composition. This is due in part to the ambiguous nature of the substitution (visible character of the rose vs. invisible character of the heart) noted earlier, and in part to the small fraction of the work being affected by this procedure. It must also be noted that the substitute object is of a more or less equivalent size to the object it replaces, thus reducing the visual impact of the transfer. Furthermore, let us add that the application of a limited colour scheme to the entire surface plane, and the overall schematization of the image mentioned in the initial description of the work, are two criteria which bind the image into a structured whole.Looking at

Le Jockey perdu

we notice that the substitution procedure initiated inJeune fille ayant une rose à la place du coeur has been modified. The relative

equivalence in size between heart and rose witnessed in the 1924 painting has

been abandoned in favour of a more contrasted choice of objects. The greater

discrepancy in the size of the two objects involved in the substitution procedure

(i. e., the bilboquet

and the tree trunk) has not, however, severed all of the ties linking them together. Indeed, some form of association in colour, shape, and material still remains.Let us now briefly comment on the overall visual consequences of this substitution. For one, I would suggest that the unexpected and illogical appearance of the

bilboquets

has served to isolate them from the rest of the image. Although their presence is not altogether without purpose (they still serve as trunks from which the branches may sprout) their acute disproportionprevents them from being coherently included in the scenery depicted. It is as if, in perceiving the overall image, one is simultaneously offered two distinct and overlapping scales. Their reconciliation into a unified image is still possible, though not without a certain degree of effort.

The organic and nonorganic work of art

It is Bürger’s contention that the historical period to which the avant-garde belongs created a crisis in the specific historical form of the "work," or the "artwork" as a category. This period called the unity of works into question. It did not destroy it (though such were the dadaïsts’ intentions), but it mediated it, for the concept of unity was extended and stretched to new limits. What the avant-gardiste work really called into question, says Bürger, was the traditional "organic" conception of the work, with its relationship between parts and whole.

In the organic (symbolic) work of art, the unity of the universal and the particular is posited without mediation; in the nonorganic (allegorical) work to which the works of the avant-garde belong, the unity is a mediated one. Here, the element of unity is withdrawn to an infinite distance, as it were. In the extreme case, it is the recipient who creates it... .The avant-gardiste work does not negate unity as such ... but a specific kind of unity, the relationship between part and whole that characterizes the organic work of art.13

13

Bürger denotes as classicist the artist who produces organic works. This artist, states Bürger, will take on a different attitude towards his material than does the avant-gardiste. The classicist will view his material as a living substance, as a carrier of meaning. For the avant-gardiste, material is nothing other than an empty sign into which only he can introduce significance. He tears the material "out of its functional context that gives it meaning... .The Classicist treats the material as a whole, whereas the avant-gardiste tears it out of the life totality, isolates it, and turns it into fragments."14

The diverging attitudes expressed by both category of artists towards their material, notes Bürger, is reflected in their attitude towards the constitution of the work. The classicist conceives of the work as a living image of the totality and this even though the work may only show a segmented representation of reality. In keeping with his approach to the material, the avant-gardiste intends to control the meaning.

The works created by Magritte between 1925-1927 can best be described as a series of attempts to negate spatial and semantic unity. By spatial unity, I refer to the system of representation established during the Renaissance which

implies that the painting surface is understood as a "window" through which we look out into a section of space. If taken seriously, this means no more nor less than that pictorial space is subject to the rules that govern empirical space, that there must be no obvious

contradiction between what we do see in a picture and what we might see in reality. 15

By semantic unity, I refer to Bürger’s description of the construction principle of the organic work of art where: "individual parts and the whole form a dialectical unity. An adequate reading is described by the hermeneutic circle: the parts can be understood only through the whole, the whole only through the parts."16

Bürger notes that it is possible to negate spatial unity without negating semantic unity. Here Picasso’s

papiers collés

are used as an example. Although the notion of perspective as described above has been destroyed, Bürger maintains that because the creation of an aesthetic whole is posited, a sense of unity remains. Describing thepapiers collés,

Bürger says: "the reality fragments remain largely subordinate to the aesthetic composition, which seeks to create a balance of individual elements (volumes, colors, etc.)...the intent to create an aesthetic object is clear, though that object eludes judgment by traditional rules."17The negation of semantic unity is thus understood as the emancipation of the parts from the superordinate whole: "they are no longer its essential elements. This means that the parts lack necessity. In an automatic text that strings images

15 Erwin Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting, Vol.l, Its origins and Character, (New York, Harper & Row, 1971,), pp. 140-141.

16 Bürger, p. 79.

15

together, some could be missing, yet the text would not be significantly affected."18 A work produced on this principle, says Bürger, "neither creates a total impression that would permit an interpretation of its meaning nor can whatever impression may be created be accounted for by recourse to the individual parts, for they are no longer subordinated to a pervasive intent."19 What occurs under these circumstances is characterized as a "refusal to provide meaning" or as a "withdrawal of meaning."

Although Magritte had intended as early as 1924 to emancipate parts of the painting from the superordinate determination of the whole, this process was not actually begun until 1925 and

Le Jockey perdu.

As Magritte himself noted, the efforts made in 1924 to distance the rose from its insertion within the painted image were unable to shatter the unified perception of the work. It is not until the creation ofLe Jockey perdu

that the lack of necessity, or the arbitrariness given to the parts with respect to the whole, began to be realized. Indeed, the double scale reading, mentioned earlier with regards to the presence of the disproportionatebilboquets

amidst a spatially unified scenery appeared as the initial step in drawing the objects away from a global and comprehensive reading of the whole.It is my belief that the objects represented in the works dating from the 1925- 1927 period were gradually drawn away from the subordinate role of con structing unitary meaning. During the months leading up to 1927 (the year of

18 Bürger, p. 80. 19 Bürger, p. 80

his move to Paris, the capital of French surrealism), he increasingly began to tear his objects away from an organic structure in order to let them discover freer forms of association. These new associations liberated the objects from the harness of predestined function, and allowed them to seek meaning in a setting which surpassed market rationality. The need to expand the bounds of organic construction compelled Magritte to subject his objects to a number of procedures. His intention was here similar to that of Breton’s : to liberate words from their strict grammatical use in order to let them expose unexpected aspects of their nature.

Breton denounced and rejected notions of order and precdictability at all levels of their manifestation, and especially as they appeared in creative expression. He’s use automatic writing was accuse and denounce the restriction of language to strict uses of communication and exchange. His writing served to "emancipate words and restore to them their full power" (Surrealist Manifesto). Automatic writing was believed to liberate thought from the bounds of reason and from aesthetic and moral preoccupations an attitude which was in direct opposition to the instrumentalist and rationalist ideology of the Third Republic.

Aragon described the first experimentation with automatic writing as follows:

Tout se passait comme si l’esprit, parvenu à cette charnière de l’inconscient, avait perdu le pouvoir de reconnaître où il versait. En lui subsistaient des images qui prenaient corps, elles devenaient matière de réalité. Elles s’exprimaient suivant ce rapport, dans une force sensible. Elles revêtaient ainsi les caractères d’hallucinations visuelles, auditives, tactiles. Nous éprouvions toute la force des images. Nous avions perdu le pouvoir de les manier. Nous étions devenus leur domaine, leur monture. Dans un lit, au moment de dormir, dans la rue les yeux

17

grands ouverts, avec tout l’appareil de la terreur, nous donnions la main aux fantômes.20

Magritte’s first attempts at negating the structural basis of painting, though remaining within a painting did not avoid generating conflict. Indeed, it would appear as if Magritte was caught in a dilemma with respect to the representation of receding space. The conflict arose between the need to use effects of the third dimension to intensify the impact produced by the manipulation of objects and the identification of receding space with the structural basis of the organic work of art.

Much as Magritte intended to negate traditional organic unity, the very fact of having to express this negation in pictorial terms implied the urgency of some form of synthesis. I believe that during these early years, Magritte attempted to redeem his "deviations" into spatial perspective by directly opposing the illusionary (figurative) effects of this representation to the two-dimensional nature of the canvas. In other words, he sought and found a way to bracket and objectify receding space, thereby distancing and reducing it to the unequivocal condition of a simple pictorial means to be used for the attainment of a specific effect.

The emergence of reminders of the two-dimensionality of the canvas can be witnessed in the case of

Le Jockey perdu

in the addition of the dark curtain on the right side of the painting. This example will be discussed in greater detail.The 1927 show

Contracts signed with Paul-Gustave Van Hecke and the Centaure Gallery in Brussels in 1926 gave Magritte the opportunity to concentrate his energy on his artistic production. As a result, 1926 figures as a particularly prolific year for the young painter, with over 60 works created. Magritte held his first solo exhibition the next year at the Centaure Gallery. The exhibition ran from April 23rd to May 3rd, 1927. Forty-nine oil paintings and twelve collages were shown. The catalogue included texts by Van Hecke and Nougé. Among the paintings shown were

Le Jockey perdu, La Traversée difficile

(fig. 5),Le

Supplice de la vestale

(fig. 6), andL’Assasin menacé.

Le Jockey perdu

was the earliest among them.Critical reception to this exhibition was largely negative. Bürger’s description of the nonorganic work as being characterized by a "refusal to provide meaning" or by a "withdrawal of meaning" was perceived by some authors, though certainly in an uncritical manner. Indeed, one author wrote:

On pourrait peut-être écrire le vide. Magritte nous prouve qu’on peut le peindre... Je n’y vois qu’une seule chose: c’est le produit d’un cerveau de citadin exsangue, trop faible pour être sensuel, d’un être, énervé jusqu’au grand calme; nous sommes dans le grand froid, dans le grand silence, dans la mort. Plus rien ne relie cet art à la réalité: c’est, au fond, un produit très naturel du spiritualisme poussé jusqu’à l’extrême.21

21

19

Another added:

L’exposition Magritte sue toutes les sueurs d’un modernisme qui n’en peut plus. Que dire devant ces toiles prétentieuses, sans aucun lien vivant, veules, sinistres de pauvreté, affichant, sans pudeur, la décomposition d’un milieu qui crève d’individualisme et sent la charogne à quinze pas?22

It must be kept in mind when reading these lines that the viewer’s pictorial anticipation at the time of the exhibition had been largely forged by the stability and order of the

Ecole de Paris.

Indeed, artists such as André Derain, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso had, by this time, all returned from their experimen tations and wanderings of the 1910s to reorient themselves in an aseptic academism.At the same time as Magritte was working on his first attempts at defining a new pictorial vocabulary, a series of regular meetings were being held on the rue Blomet, in Paris, between Masson, Miro, Leiris, Limbour, Artaud, and Desnos. Together, these men were beginning to imagine the possibility of creating an automatist imagery. The results of these visual experiments, where the unconscious was allowed to dictate the drawing or painting while the logical forces were held back, were first exhibited in 1925 at Pierre Loëb’s Gallery. These first experiments led to the creation of distinct automatist techniques, and eventually to the development by some artists of a particular mode of functioning. Such was the case with Dominguez’

décalcomanies sans objet

préconçu,

Man Ray’ssolarisations

and other manipulation of photographic techniques, and Max Ernst’sfrottages

andraclages.

A neutral style

Three years prior to painting

Le Jockey perdu

Magritte had written:Une grande erreur est la cause de recherches désespérées de la plupart des peintres modernes: ils veulent fixer "a priori" le style-aspect d’un tableau; or ce style est le résultat fatal d’un objet bien fait: l’unité de l’idée créatrice et de sa matérialisation.23

It is my observation that the combination of "materialization" and creative idea mentioned by Magritte was most accurately reflected in the realization of a neutral style. By neutral style I am referring to the use of a pictorial means to function as a mediator between an idea and its representation — a tool to materialize a thought.

il faut donc que le peintre connaisse à fond les ressources matérielles dont il dispose et les emploie rigoureusement selon les lois de leur substance. Il doit être un savant technicien MAITRE de son métier et non ESCLAVE. La virtuosité est le cas de l’idiot (considéré médicalement). Le vrai métier, c’est la disposition, le choix des lignes, formes et couleurs qui déclencheront automatiquement la sensation esthétique.24

23 Magritte, p. 18.

21

Later in 1938, Magritte again commented on his style:

Cette manière détachée de représenter des objets me paraît relever d’un style universel, où les manies et les petites préférences d’un individu ne jouent plus. J’employais, par exemple, du bleu clair là ou il fallait représenter le ciel, contrairement aux artistes bourgeois qui représentent le ciel pour avoir l’occasion de montrer tel bleu à côté de tel gris de leurs préférences. Je trouve quant à moi, que ces pauvres petites préférences ne nous regardent pas et que ces artistes s’offrent dans le plus grand sérieux en spectacle très ridicule.25

According to Bürger, the avant-garde movements were the first to liberate "artistic means" and allow them to become physical means. He emphasizes that for the first time in history, a truly styleless movement was developed. "What did happen is that these movements liquidated the possibility of a period style when they raised to a principle the availability of the artistic means of the past periods."26 In Burger’s opinion, it was at a time when one began to see "defamiliarization" or shock as the general principle at work in avant-garde art that one was able to recognize that the object "artistic means" had reached its full historical development.

The use of space

Raising pictorial means to the level of physical means, and thus liberating them from their association with specific aesthetic canons not only involved the

25 Magritte, p. 108.

creation of a neutral style but also required the explicit denunciation of the use of traditional linear perspective as an illusionary practice. This Magritte achieved by simultaneously opposing two- and three-dimensional effects within a single image. If in

Le Jockey perdu

the use of receding space was deemed necessary to heighten the effect of the substitution process, it is, however, forbidden from defining the whole image. Indeed, Magritte sets up fragmentary reminders of the actual two-dimensional nature of the canvas.The presence of the dark curtain on the right side of the canvas is one instance where such resistance occurs. I perceive this curtain as fulfilling a double function. For one, it plays on the theatrical aspect of the image. It heightens the impression that the surrounding space only acts as a neutral site into which the objects are the only real protagonists. For another, it reinforces the perception of the picture plane as a fiat surface resembling a window.

The image of the horse and jockey presents a second instance of disruption in the homogeneous perception of receding space. The only reproductions I have seen of this painting have been printed in black and white. Furthermore, the quality of the print has never been very good. However, given these inconveniences, it still remains possible to observe the two-dimensional effect given to the figure (horse and jockey). In contrast to the detailed surrounding landscape, the horse and jockey appear as dark silhouetted forms. Aside from the presence of a few highlighted areas (cap, hand, right side of the face), the whole figure appears to be defined entirely by contour. The contrast achieved by superimposing the dark silhouetted figure upon a lighter background produces a collage effect. Magritte cleverly integrates the impression of collage

23

into his image by strategically positioning the head of the jockey on the central vanishing point27, as well as by avoiding a complete profile image of the horse and jockey by presenting them in a semi frontal position.

Let us compare this ambiguous, double standing status given to the horse and jockey figure to one mentioned earlier with regards to the same painting. I have already discussed the problematic status of the

bilboquets.

It has been upheld that their presence within the image creates both a disturbing and a normalizing effect. Though their insertion within the landscape is illogical, they are integrated into the composition by preserving a utilitarian function and by maintaining a number of characteristics (shape and material) which relates them to their substitute, the tree trunks. If this instance serves as an example of the kind of disturbance which can disrupt the semantic unity of the work, a similar example can be noted with regards to the spatial unity.As is seen in the above description of the painting, the horse and jockey are subjected to two different spatial readings. They are defined.by their flatness, and yet their strategic position and orientation within the landscape also allow them to be comprehensively inserted within the whole image. A certain amount of tension arises from this ambiguous situation. Receding space is at once affirmed and rejected. The double identity (fiat yet inserted within a composition defined by the laws of perspective) given to the figure is a good

27 "...in the perspective picture all parallel lines, regardless of location and direction, converge in one of an infinite number of Vanishing points’; all parallels intersecting the picture plane at right angles (’orthogonal’, often loosely referred to as Vanishing lines’ pure and simple) converge in a central vanishing point (often loosely called the Vanishing sight’)". Panofsky, p. 5.

example of the way in which Magritte disrupted organic spatial unity by using receding space as a simple pictorial tool.

I shall use the term "objectification" of space to define the specific kind of contradictory use of space made by Magritte in those early years. This term, then, refers to what I perceive as an intention on Magritte’s part to qualify the space hosting the combined objects as a purely functional area (as a setting), by exposing the actual flatness upon which this representation is built. In other words, the intention is to deny the illusionary representation of space its traditional status as a fundamental element of painting (as was the case in organic works of art) by elevating this practice to the level of a pictorial means.

While still in his futurist style, Magritte had already made allusions to the possible necessity of drawing upon receding space as a tool for creating specific effects. He wrote:

Lorsque l’idée créatrice nécessite des plans en profondeur pour son expression adéquate le peintre doit sacrifier l’aspect plane de la toile, car c’est la toile qui sert et non le peintre et il ne peint pas pour couvrir une toile de couleurs, comme le poète n’écrit pas pour couvrir une page de mots.28

A similar effort at objectifying the illusionary aspect of a technique by designating it as a consciously used tool occurs at times in film. Such is the case in Godard’s 1967 movie entitled

La Chinoise,

when one of the actors25

unexpectedly turns to the camera and addresses the audience directly. This sequence is immediately followed by a short scene in which the in-action cameraman, to whom the actor is addressing himself, is in turn shown on the screen in the act of recording the event taking place before him. This kind of diversion momentarily repels the spectator from complete absorption.

It is my conclusion that Magritte continued to negate the use of receding space until about 1927. At this time he gradually moved away from a contradictory and ambiguous representation of space towards isolating his objects against a uniform and monochrome background. This allowed him to channel his efforts exclusively to the development of procedures for relating objects to one another. It was not until 1933, after the discovery of his work process known as

objet-

réponse,

that Magritte finally re integrated receding space within his image. This incorporation of the third dimension differed from the practice witnessed in the earlier years, in that it operated on a positive and constructive basis. As will be discussed in the third chapter with regards toLa Condition humaine,

the integration of receding space was then made on the same basis as that of any other object involved in the construction of anobjet-réponse,

and no longer served to disturb the cohesion of the work.Collages

It is during the 1925-1927 period that Magritte did most of his experiments with collage. Given his interest in creating a confiictive representation of space, it is possible to see in this technique an opportunity for him to develop stronger

and freer forms of confrontation than the painting medium allows. Collages are similar in principle to the idea of frottage. They allow for a freer, more spontaneous assemblage of forms, figures, and shapes taken directly from one’s immediate surroundings. Magritte often combined collage with some drawing and painting techniques.

Because some of the works created with the collage technique reproduce themes presented in earlier paintings, it is possible to make some observations on the changes which this new medium brought to the image. A look at the 1926 collage entitled

Le Jockey perdu

(fig. 7) can give us such an indication.For one, we notice that the drawing of the jockey and horse team is much more detailed. If in the painted version the illusionary representation of receding space was confronted by a dark silhouetted jockey and horse, we observe that in the collage version the reverse is true. The flat background is here contrasted to a detailed and illusionary representation of jockey and horse.

We also observe that a third procedure has been added to the combination of

bilboquets

and tree branches. In addition to the procedures of substitution and of scale inversion already noted in the painted version, we observe that a change in texture has occurred. This modification is obtained as a result of a "découpage" technique. A sheet of music has been cut in the shape ofbilbo

quets

and glued onto the pictorial surface. Tree branches were then painted on the extremities of these shapes.27

Magritte pursues his conflictive representation of space by contrasting the two- dimensional effect of the découpage technique with the effects of depth and volume. This is accomplished by drawing some shaded areas along the right side of the

bilboquets,

thus attempting to give volume to a form defined by flatness.Although doing away with the strong receding lines observed in the painted version of

Le Jockey perdu

, Magritte does not altogether abandon the feeling of receding space; rather, new devices are being sought to produce a similar effect. The presence of curtains on both sides of the image accentuates the impression of scenic space noted earlier in the painted version. The wash of blue ink painted in gradation from dark to light as it descends towards the centre of the work also creates an effect of receding space. So too does the network of arbitrarily drawn diagonals which delimits the area of the scene. To do Magritte justice however, I must stress that not all of his collages maintain such a high contrast between the two-dimensional and three-dimensional effects. The works shown in figs. 8 and 9 serve to illustrate this last point. Indeed, we notice in both of those works that the images are no longer held within a coherently organized "scene" (one being defined according to the laws of perspective), but are scattered in such a way as to resist a congruence between the meaning of the individual parts and the meaning of the whole.The notion of space: Magritte and Brecht

The playwright Bertold Brecht had, at about the same time period, a similar contradictory notion of space, of its representation and of its use as the one noted in Magritte’s early works. Though using the theatre stage as a privileged location from which to present his plays, Brecht explicitly denounced this setting as fictional. In fact, he developed a number of processes to prevent the spectator from identifying with the scenes acted on stage.

Brecht considered that the process of identification which normally occurred in bourgeois theatre only served to let the spectator dwell on emotions as a kind of therapy for a short and determinate time. The play would in this sense be experienced as a kind of purge. Once the play ended, the bourgeois could go back to a life of repression and alienation, without having pondered upon the nature of the split existing between leisure and work. Brecht wanted his theatre to induce the spectator to thinking. He wanted to sever the automatic link of identification, so that instead of letting himself be guided along to predetermined emotional and ideological responses, the spectator could of himself stand back and reflect upon the action presented to him.

The techniques used by Brecht to achieve this breach between play and audience were motivated by a sort of objective representation. For example, the actor was not to allow himself to identify with his character, seeing how this identification process would automatically induce a similar reaction in the audience. Instead, the actor was to be able to maintain his identity as comedian and from such a standpoint only, relate to the audience a delayed or distant

29

version of the character he was interpreting. The notion of distanciation was thus also applied to the kind of play-acting to be performed by the comedian.

There were to be no hidden or special effects produced on stage. Lighting was to be as neutral as possible. The variations in light were to be suggested by signs or symbols (i.e., a moon for the night), and not by a make-believe reproduction of the actual light intensity. Actors who were waiting for their parts were permitted to stay on stage. Similarly, the musicians were also to be in full view, so as to render visible the source of the musical contribution.

Brecht was also presenting the artistic process of creation as a process of rational choice between various available means. The conflictive relationship between the illusionary representation of space and its denunciation as illusionary noted earlier with regards to Magritte’s work, was also present in Brecht’s work. On the one hand, the use of a theatrical stage and setting was deemed mandatory for the presentation of the action, yet on the other, this space was explicitly prevented from fulfilling its illusionary role. Through a series of processes, it was manipulated in such a way as to induce the spectator to view it as a tool or as a neutral area which simply hosted the action without defining it. Brecht, then, also attempted to negate the basis of theatre, though remaining within a theatrical mode of expression.

Magritte and Brecht similarly prevented the viewer from wallowing in the action. In both cases, this distanciation was achieved as a result of the contradictory status of the product (i.e., paintings and plays which were identified on the basis- of a negative rapport with their medium). The conflict

occurred between the affirmation of space through its illusionary representation (Magritte) or actual physical use (Brecht) on the one hand, and its negation or destruction through disruptive processes on the other. Magritte says of his painting:

I don’t paint ideas. I describe, insofar as I can by means of painted images, objects and the coming together of objects in such a light as to prevent any of our ideas or feelings from adhering to them.29

Peter Bürger comments on the type of reception which accompanies these works. He maintains that what distinguishes the historical avant-garde from other movements

consists in this new type of reception that the avant-gardiste work of art provokes. The recipient’s attention no longer turns to a meaning of the work that might be grasped by a reading of its constituent elements, but to the principle of construction.30

Through an "irrational" construction of space, meaning is denounced. Bürger explains that if the recipient is unwilling to accept a partial or arbitrary meaning expressed only through parts of the work, he must necessarily orient his attention to another level, that of the principle of construction. By refusing to adhere to the usual hermeneutic circle which provides meaning for the whole through a cohesion of its parts, the avant-gardiste work produces a shock effect. "Shock is aimed for as a stimulus to change one’s conduct of life; it is the

29 Suzi Gablik, Magritte, (London, Thames and Hudson, 1970), p. 13.

means to break through aesthetic immanence and to usher in (initiate) a change in the recipient’s life praxis"31

Le retour à Vordre and Magritte’s destruction of spatial and semantic unity

In a brief essay entitled

Les fameuses Années Vingt,

Theodor Adomo comments on the false illusions of freedom and political liberation which prevailed about the 1920s.Ce que la conscience du public d’aujourd’hui - du moins la mode de la réactualisation - met au compte des Années Vingt était déjà en déclin à l’époque, dès 1924...32

Fostering an ideal vision of the 1920s in Europe, remarks Adomo, gives fascism the false appearance of having been externally applied, rather than being the consequence of an inward-found phenomenon.

Les phénomènes de régression, de neutralisation, cette paix des cimetières que l’on n’attribue généralement qu’à la pression de la terreur nazie, apparaissaient déjà sous le Régime de Weimar, et en général dans les sociétés libérales européennes. Les dictatures ne fondirent pas sur ces sociétés, de l’extérieur, tel Cortez envahissant le Mexique, mais elles furent engendrées par la dynamique sociale après la Première Guerre mondiale, et projetèrent leur ombre sur l’avenir.33

Bürger, p. 80.

32 Theodor W. Adomo, Modèles Critiques, (Paris, Payot, 1984), p. 47. 33 Adomo, p. 47.

Le retour à l’ordre

which occurred during the early twenties had already set the ground for an idealization of order which Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin were to bring to its apotheosis.In France, the search for stability and order headed by Raymond Poincaré and Aristide Briand, both of the

Bloc National,

was typical of the tactics used by all conservative governments. It included, among others measures, a refusal to partake in any form of innovative measures (economic or social), and the reduction of taxes to their lowest possible levels, thus precariously relying on short-term bonds as a source of financing. This option was all the more delicate, since France was balancing its budget by taking into account unreceived payments to be made by Germany in reparation for war damages.Peace, normality, and safety were the prevailing

mots d’ordres.

In 1921 relations with the Vatican were renewed in order to provide "religious appeasement. " Patriotism was being encouraged by the wide-spread propagation of anti-German sentiment. In other words, all sorts of issues were being sought to defer the government from taking action and from having to deal with real issues. For Nathanael Greene, the 1920s resembled more "the decade preceding the First World War than the decade that was to follow."34This nostalgic look back to the stability of the prewar period also occurred in the visual arts. The academism of The School of Paris which had triumphed before 1914 was brandished as a remedy against the youthful wanderings of

34 Nathanael greene, From Versailles to Vichy - The Third French republic, 1919-1940, (New York, Thomas Y. crowell Company, 1970) p. 32.

33

cubism and fauvism. The tenants of an artistic

retour à I

’ordre

were praising the same values of stability, order, and hierarchy which the leaders of the centre and right were advocating and trying to install at the cost of raising fascism.At a time when the shaping of the pictorial space as a continuum was being upheld as the only valid form of representation, Magritte was pursuing his destruction of organic unity. Though the works done in 1926-1927 were still generally organized according to the laws of perspective with lines converging towards a vanishing point, this vanishing point was no longer visible as in

Le

Jockey perdu.

Rather, the scenes were almost always limited to interiors, or at least to a mixture of interior and exterior. Whereas in LeJockey perdu,

Magritte had sporadically begun superimposing two- and three-dimensional effects, the process later became internalized, in the sense that the opposition between the two spatial dimensions occurred within the bounds of the structural design of the image. As can be observed inLa Traversée difficile

(fig. 5) andLe Groupe silencieux

(fig. 10), whole surface areas of the depicted interior are ambiguously represented in part as fiat surfaces (a wall) and in part as scenic views. In other words, whereas in prior works (especially in the collages) the conflictive relationship between the two- and three-dimensioanl effects produced as a result of juxtaposition occurred anywhere on the surface of the canvas, in the works dating from 1926 and 1927 this opposition of effect is almost entirely restricted to the surface areas delimited by the construction of the interior space (i.e., to the walls and panels inside the room).Both of the paintings mentioned above are constructed around the representation of an interior space with a scenic view painted on the back wall. The direct

confrontation between effects of flatness and illusionary receding space witnessed in

Le Jockey perdu

is here condensed and transposed into the ambiguous nature of the back plane. Is this plane a painted surface depicting an outdoor scene, or is it an actual view onto such a scene? Magritte plays on the impossibility of determining whether this plane is in the second or in the third dimension. This simultaneous presence of both dimensions is repeated on the side walls of the rooms where perforated panels of wood are positioned. The square panels, which have been interpreted by some writers as representating paintings,35 have been pierced with square openings. The panels have been strategically inclined and positioned so as to allow the "windows" to give onto flat surfaces, and also to reveal some sense of depth.It is possible to say that in both of these images the only vestige left from the receding perspective of

Le Jockey perdu

is the alignment of wall, ceiling and floor. The objects located within this space no longer find the kind of coherence which defined the hybrid trees inLe Jockey perdu.

As incongruous as the mixture of bilboquet and tree branches may have seemed, the resulting object nevertheless fulfilled a coherent function within the whole image. This is not the case inLa Traversée difficile

andLe Groupe silencieux.

The objects represented no longer work towards constructing a semantic unity of meaning. The three eyed cube, the cut-out wooden figure, the empty frame set in front of a perforated canvas partially draped by a red curtain and the distant castle positioned on the edge of a cliff, which are all represented inLe Groupe

silencieux

no longer amount to the kind of semantically cohesive structure still35

partially present in

Le Jockey perdu.

The parts no longer inform the whole. Each element is isolated and turned into a fragment whose meaning is no longer dependent on a functional context.Later in 1927, Magritte added to this negation process by violently deforming the objects or figures represented in his paintings. Rather than simply displaying objects next to one another, he also began assembling and constructing them into units. The figures joined together no longer attempted to form a hybrid whole (as in the case of the bilboquet and tree branches - where both com ponents function as other, yet also as a comprehensive part of the whole), but remained independent fragments whose accumulation failed to produce a unitary meaning.

Le Supplice de la vestale

(fig. 6),Entracte

(fig. 11), andLe Double

Secret

(fig. 12) are examples of this. The assemblage of arms and legs inEntracte,

and the combination of torso and what appears to be four metal rods inLe Supplice de la vestale,

do not produce the kind of constructed meaning which held the hybrid trees together inLe Jockey perdu.

As Magritte gradually moved towards an emphasis on an arbitrary assemblage of objects, he progressively backed away from a conflictive representation of space. The spatial composition of the 1927 paintings are sharply divided into two distinct zones: an immediate foreground and a distant background. The objects appear in the immediate foreground of the painting. The background is, in most cases, composed of a horizon line joining uniformly a fiat sky and seascape (or sky and landscape). Presented in front of such a vast background, and detached from the kind of setting which the interior space of 1926 upheld for them, the objects become all the more isolated. This isolation is amplified

by the fragmentation to which the objects and bodies are subjected. In comparison to the 1926 painting, where the objects were shown in their entirety, the figures depicted in the 1927 paintings are only partially represented. This is the case with the torso and fragments of walls in

Le

Supplice de la vestale,

the body parts inEntracte,

and the head and shoulders inLe Double secret

(fig. 12). The references to linear perspective are reduced to anecdotal remnants. They occur sporadically in the form of partial walls and floor space (seeEntracte

andLe Supplice de la vestale

).Although Magritte has begun to reduce and simplify his representation of receding space in favour of an increased interest in the manipulation and fragmentation of objects, the confrontation between the effects of the second and third dimension still lingers on.

Le Double secret

is one example of this. A man is shown from the shoulders up and portrayed in a semi frontal position against an ocean scene background. The face has been subjected to a strange manipula tion. The central portion, meaning most of the facial features and part of the neck and shoulders, have been cut away from the bust and transposed directly to the left of the figure, on an equal pictorial plane with the latter. This fiat segment is simply juxtaposed upon the background scene. Although the cutting pattern is arbitrary, it remains well within the bounds of the face. The cavity created as a result of the removal of the central piece reveals an undulated surface of metallic spherical bells. This surface is slightly set back within the figure, as if it were inside the body.If on the left side the flatness of the facial segment is defined by its opposition to the vast horizon and by the jagged edges arbitrarily delimiting its contour,

37

the segment on the right is characterised by an inverted opposition. The insertion of the undulated sheet metal within the bust gives the figure a sense of depth and volume. This is heightened by the treatment given to the jagged line delimiting the right side of the cavity. Looking closely at this line, one notices that it possesses a certain thickness, giving the impression that the bust is in fact a hollow sculpture.

The simultaneous perception of flatness and depth observed in Magritte’s earlier paintings is in this case being presented side by side. On the left we observe that the illusionary representation of volume (shadows and highlights employed in drawing the facial features) is being denounced for its falseness. On the right we observe that the same illusionary representation of volume is being confirmed in its trueness. On the left, the figure is perceived as a flat segment, on the right as a hollow structure.

Generally speaking, I perceive the works produced during the 1925-1927 period as the result of a pictorial form of automatism. It is my belief that these works correspond more closely to the type of arbitrary association of forms "dictated by the mind in absence of all control exercised by reason" advocated by Breton in the First Surrealist Manifesto than what was to follow in later years. As was seen in the case of

Le Jockey perdu,

attempts had been made by Magritte to join objects together using some constructive principle. For the most part, however, at least for the years 1926-1927, it must be emphasized that this association of objects restricted itself mainly to an arbitrary display of unrelated objects. Having been tom away from their usual context, the objects were usually presented side by side without being necessarily submitted to a reconstructionprocess. On this aspect, Giorgio De Chirico’s works dating from the

années

géniales

can certainly be seen as a possible source of influence.It is my intention to suggest that by gradually evolving towards the negation of both spatial and semantic unity, Magritte’s works of 1925-1927 achieved a strong criticism of commodity relations, of reification. By inscribing themselves in opposition to the autonomous and aesthetic character of modernist works, they reacted against the commodity relations which had given rise to them. I believe that the creation of "shattering" images used by Magritte was a means of critically perverting and distorting reified bourgeois consciousness.

A reaction to modernism

In