O

pen

A

rchive

T

OULOUSE

A

rchive

O

uverte (

OATAO

)

OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and

makes it freely available over the web where possible.

This is an author-deposited version published in :

http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/

Eprints ID : 19370

To link to this article : DOI:

10.1016/j.corsci.2017.02.022

URL :

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2017.02.022

To cite this version :

Gravina, Rosanne and Pébère, Nadine and Laurino, Adrien and

Blanc, Christine Corrosion behaviour of an assembly between an

AA1370 cable and a pure copper connector for car manufacturing

applications. (2017) Corrosion Science, vol. 119. pp. 79-90. ISSN

0010-938X

Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent to the repository

administrator:

staff-oatao@listes-diff.inp-toulouse.fr

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Corrosion

Science

jo u r n al ho m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / c o r s c i

Corrosion

behaviour

of

an

assembly

between

an

AA1370

cable

and

a

pure

copper

connector

for

car

manufacturing

applications

Rosanne

Gravina

a,b,

Nadine

Pébère

a,

Adrien

Laurino

b,

Christine

Blanc

a,∗aCIRIMAT,UniversitédeToulouse,CNRS,INPT,UPS,ENSIACET,4alléeEmileMonso,CS44362,31030Toulouse,France bLEONIWiringSystemsFrance,5avenuedeNewton,78180Montigny-le-Bretonneux,France

Keywords: A.Aluminium A.Copper B.EIS C.Crevicecorrosion C.Pittingcorrosion

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

ThecorrosionbehaviourofanassemblybetweenanAA1370cableandapurecopperconnectorforwiring harnesseswasstudiedinneutralchlorideandsulphatecontainingsolution.Electrochemicalimpedance measurementsshowedthatthecorrosionbehaviourofthecablewascontrolledbytheingressofthe elec-trolyteinsidecablecavities.Further,localimpedancemeasurementswereperformedontwoassembly cross-sections,i.e.withandwithoutcavitiesinthealuminiumcable.Theresultsprovidedevidencefor boththegalvaniccouplingbetweenaluminiumandcopperandthepresenceofcavitiesinthealuminium cableasrelevantexplanationsforthecorrosionbehaviouroftheassembly.

©

1. Introduction

Typicalwiringharnessesintheautomotiveindustryconsistof assemblybetweenCucableandCuconnector.Today,thepressure inenvironmentalregulationsledtosearchforsolutionsgivingrise tofueleconomyandreductioninCO2emission.Inthiscontext,car

manufacturersplannedtoreducebothcostandweightofwiring harnesses.OneinnovativesolutionisthesubstitutionofCubyAl alloys,suchasAA1370,incables.Inthelastyears,severalworks concernedthemanufacturingprocessesofthisnewtypeof assem-bly.Recently,differentmethodshavebeenproposedtoproduceAl strandswithductilityandfatiguecharacteristicsreliablefor auto-motivewiringharnesses[1–4]whileultrasonicweldinghasbeen usedtojoinAlcablewithCuconnector[5,6].However,onemajor problemforwiringharnessesconcernstheircorrosionresistance because,in service,wiring harnesses are exposedto aggressive media,suchasde-icingsalt,whichcangeneratecorrosiondamage. Numerousdataarereportedintheliteratureconcerningthe cor-rosionbehaviourof1xxxAlalloys.Themainresultsconcernedthe influenceofFe-richparticleswhichactascathodicsitesand pro-motefirstdissolutionofthesurroundingmatrixandthen,pitting corrosion[7–9].However,thecorrosionbehaviourofanAlcableis morecomplex.Intheliterature,onlyfewworkshavebeenreported

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:christine.blanc@ensiacet.fr(C.Blanc).

concerningthecorrosionbehaviourofacable.XuandChen inves-tigatedthecorrosiondamageofwirespecimenspulledfromthe replacedcablesinShimenBridge[10].Theyanalysedthecorroded cablesfromthesheathbreakagetothecablecenterandexplained thattheextentofcorrosionatanypointofacablesectionwas con-trolledbyitsdistancefromthesheathbreakageduetothefluidthat couldpenetrateinsidethecable[10].IshikawaandKawakami[11] showedthepresenceofcavitiesinsideacableduetothe incom-pletepenetrationofthesheathrubber.Then,duringexposuretoan aggressivemedium,thesolutionpenetrateintothecablecavities leadingtotheformationofaconfinedenvironment.Dependingon theconfigurationoftheharness,e.g.numberofstrandarms con-stitutiveofthecableandspacebetweenthem,andtheintrinsic corrosionbehaviourofthestrand,theconfinedelectrolyte com-positionshouldevolverapidly,e.g.,oxygenconcentration,cations concentrationandpH,andtheninduceseverecorrosion phenom-ena,suchascrevicecorrosion[12–14].ChanelandPeberestudied themechanismsgoverningthedegradationofbrass-coatedsteel cords fortyresin a 0.25M Na2SO4 solution incontact withair

andmaintainedat25◦Cbyusingelectrochemicalimpedance

spec-troscopy(EIS)[15].TheyshowedthatEISwasasuitabletechnique toquantifythecorrosionresistanceofacable[15].Moreover,the assemblybetweenanAlcableandaCuconnectorshould gener-ategalvaniccorrosionduetothedifferenceincorrosionpotential valuesbetweenthetwometalsinaqueoussolution[16–21].Khedr andLashieninvestigatedthecorrosionbehaviourofpureAlinCu2+

richsolutionsandshowedtheacceleratingeffectoftheCu2+cations

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2017.02.022 0010-938X/©2017ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved.

AlcorrosionrateduetoCudepositionandsubsequentgalvanic coupling[17,18].Jorcinetal.[19]showed,foramodelcouple con-stitutedofAlandCu,thechemicaldissolutionofAlduetoapH increaseattheAl/Cuinterface;thisgeneratedanoccludedzonein whichthecompositionoftheelectrolyte(a10−3MNa

2SO4

solu-tionincontactwithairandatroomtemperature)evolvedrapidly. ThegalvaniccouplingbetweenAlandCuwasalsoinvestigatedina 10mMNa2SO4solutionbyusingathin-layercellinordertomodel

theoccludedzoneinthecrevice[20].Jomaetal.performed exper-imentsina0.1MNa2SO4solutionandshowedthatthechemistry

inathin-layercellplaysasignificantroleatleastatalocalscale [21].

The present work contributes to get a better insight of the mechanismsgoverningthedegradationofanAA1370cable/pure Cu assembly with a particular attention to the effect of the electrolyteingressinsidethecable.Conventionalelectrochemical measurements(Ecorrmeasurements,polarisationcurvesand

elec-trochemicalimpedancespectroscopy)werefirstcarriedoutforthe AA1370cableinordertoinvestigatethecorrosionbehaviourofthe cablealone.Giventhatthecablewasmadeofalargenumberof strands,theelectrochemicalmeasurementswerealsoperformed forAA1370strandstohaveabetterunderstandingofthe corro-sionmechanisms.Then,toinvestigatethecorrosionbehaviourof theAA1370cable–Cuconnectorassembly,localelectrochemical impedance(LEIS)measurementswereperformedontwo cross-sectionsof theassembly,onecross-section correspondingtoan AA1370cablewithcavitiesandtheotheronewithoutcavities.LEIS isanon-destructiveelectrochemicaltechniquethathasbeenused inrecentyearstostudylocalizedcorrosiononbimetallicsurface [19,22–26].Itwasusedheretodeterminetheinfluenceofthe cav-itiesintheAA1370cableafterweldingonthegalvaniccorrosion processesoccurringfortheAA1370cable/Cuconnectorassembly.

2. Experimental 2.1. Materials

TheassemblywasobtainedbyultrasonicweldingusingaDS 20-IIapparatusbetweenanAA1370(99.7%Al,0.072%Fe,0.0045%Mg, 0.045%Si;wt.%)cableandapureCu(99.90wt.%Cu;200–400ppm O2)connector.TheCuconnectorwasahotstampedCusheet.In

thefollowing,theAA1370cableintheassemblywillbereferred toas‘theAlpart’;theAA1370cable/Cuconnectorassemblywillbe referredtoasAl/Cuassembly.Duringtheweldingprocess,thecable (withoutthepolymershell)waspositionedontheCuconnectorand apressurewasexerted.Then,ultrasonicvibrationswereappliedso thatthecableandtheCuconnectormovedrelativelytooneanother withanoscillatingmovement.Thisledtoafrictionbetweenthetwo metalsandthentotheformationofaweldingzone.Thetotallength oftheweldedzonewasabout12mm.Thequalityofthewelding dependsmainlyontheappliedpressureandontheamplitudeof thevibrations.Therewasashortzone(8mm)wherethestrands constitutiveofthecablewereentirelyweldedtogethersothatthe cabledidnotrevealanycavitiesafterthewelding,thiszonebeing calledasthe‘effectiveweldedzone’.

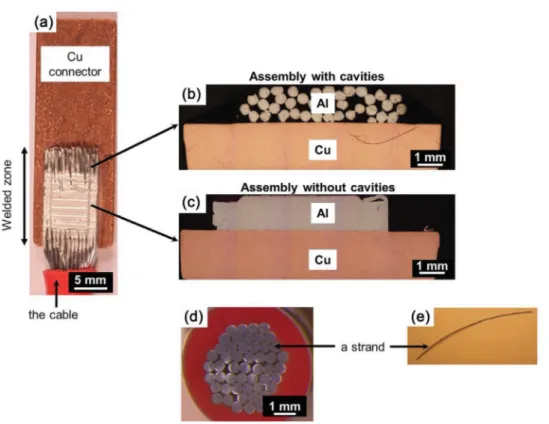

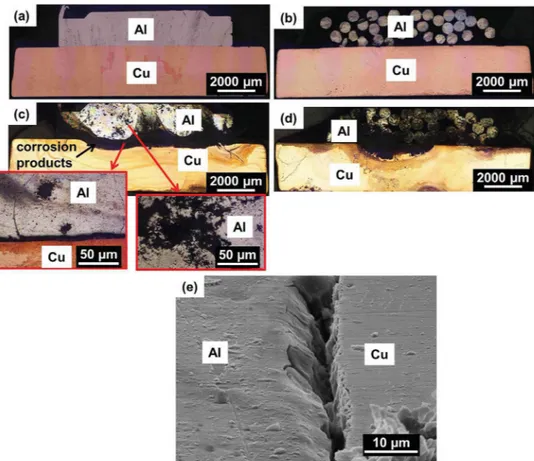

Thegalvanic couplingat theAl/Cu interfacewas studiedby electrochemicalmeasurementsperformedontwocross-sections oftheassembly.Fig.1ashows aglobalpictureoftheassembly. Thetwoselectedcross-sectionsareshowninFig.1bandc.Oneof thecross-sectionswasremovedfromaporouszoneofthecable due tothe fact that thestrands constitutive of the cablewere not entirelyweldedtogether (henceforthcalled ‘assemblywith cavities’)(Fig.1b).Anothercross-sectionwasremovedfromthe effectiveweldedzonewherenocavitieswereobservedbetween theweldedstrands(henceforthcalled‘assemblywithoutcavities’)

(Fig.1c).Beforecorrosiontests,thecross-sectionswereembedded inanepoxy-resinwithoutfillingthecavities.Thiswasachievedby embeddingthecross-sectionsinaparafilmshell.

Fora betterunderstandingofthecorrosionbehaviourofthe assembly, electrochemical measurements were also performed forcross-sectionsofboththeAA1370cablebeforewelding and AA1370strandsconstitutiveofthecable.Thecross-sectionswere perpendiculartothecable/strandaxis.Thecablewasanassembly of50strands(0.52mmdiameter)protectedbyaplastic insulat-ingsleeve.Fig.1dshowsanopticalobservationofacross-section ofacablewhere the50strandscanbeobserved.Itcanbeseen that thespacebetweenthestrands isnot uniform. Toperform theelectrochemicalmeasurements,thecablewasembeddedin anepoxy-resinwithoutfillingthespacebetweenthestrands(see theprocedurefortheassembly).Ifonlythesurface perpendicu-lartothecableaxiswastakenintoaccount,thesurfaceareaof thecross-sectionofthecablewith50strandsexposedtothe elec-trolyteduringtheelectrochemicalexperimentswas0.11cm2.To

studythecorrosionbehaviourofastrand,thedifficultywasits diameter,i.e.0.52mm.Threeelectrodeswerepreparedwiththe cross-sectionsof1strand(S=0.002cm2),4strands(S=0.008cm2)

and22 strands(S=0.047cm2)respectivelyexposed tothe

elec-trolyte.Forthe3electrodes,thestrandswereorganizedtoobtaina regulararrangementoftheircross-sections(theaxisofeach indi-vidualstrandbeingparalleltotheothers)andembeddedtogether inanepoxy-resin.Allthecavitiesbetweenthestrandswerefilled bytheepoxy-resin.Preliminaryexperimentsshowedthatsimilar resultswereobtainedforthe3electrodes.However,the repro-ducibilityofthemeasurementswasbetterfortheelectrodewith 22strandsduetothefactthatthesurfacewasmorerepresentative ofthealloymicrostructure.Inthefollowing,forbrevity,onlythe resultsfortheelectrodewith22strandsarepresented.This elec-trodewasreferredtoas‘strandsample’.Itcouldbenotedherethat thecorrosionbehaviourofthestrandsamplecouldbeconsidered representativeofthebehaviourofacableforwhichthecavities wouldbesealed.Electrochemical measurementswerealso per-formedforaCusampletakenoffaconnectorusedfortheassembly; thesurfaceexposedtotheelectrolytewas0.11cm2.

Beforeallelectrochemicaltests,thesurfaceofthespecimens wasmechanicallyabradedwithsuccessivegritSiCpapers(1200, 2400)andthenpolishedfrom6to1mmgradewithdiamondpaste anddeionisedwateraslubricant.

2.2. Electrochemicalmeasurements

Allelectrochemicalmeasurementswereperformedinsulphate and/orchloride-containingsolutions;theyareassumedtobe rep-resentativeoftheautomotiveenvironments.Severalauthorshave usedsulphateand/orchloride-containingsolutionstostudyAl/Cu galvaniccouplingallowingtheresultsobtainedinthisworktobe comparedwiththeirresults[20,21].Fortheconventional electro-chemicalmeasurements(Ecorrmeasurements,polarizationcurves

andimpedancemeasurements),thecorrosivemedium(pH=6.5) waspreparedfromdeionisedwaterbyadding0.1MNa2SO4 and

asmallconcentrationofchloride(0.001MNaCl).ForLEIS experi-ments,a0.001MNaClsolution(pH=6.5)preparedfromdeionised water was chosen to maintain a low conductivity required to optimize the measurements in the low-frequency range [27]. Theelectrolyte wasmaintained ata temperatureof 25◦C±1◦C

exceptfortheLEISmeasurementsperformedatroomtemperature (22◦C±1◦C).

Fortheconventionalelectrochemicalmeasurements,the exper-imentalset-upconsistedofathree-electrodecell,connectedtoa BiologicVSPapparatus,withalargeplatinumelectrodeusedas counterelectrodeandasaturatedcalomelelectrode(SCE)as ref-erenceelectrode.Specimensusedastheworkingelectrodewere

Fig.1.(a)GlobalviewoftheassemblybetweenAA1370cableandpureCuconnector;cross-sectionsoftheassemblies(b)withand(c)withoutcavities;(d)theAA1370cable and(e)astrand.

thestrandsampleandthecable.Forthetwocross-sectionsofthe assembly,onlyEcorrwasmeasuredforexposuretimestothe

elec-trolyterangingfrom1hto168h.In thefigures,meanvaluesof Ecorr aregivenonthebasisof atleasttenexperimentsforeach

experimentalcondition.Forthepolarizationcurves,thesamples werefirstexposedtotheelectrolyteatEcorrfor3handthen,the

anodicandcathodicpartswereobtainedindependentlyfromEcorr

atapotentialsweeprateof0.07mVs−1.Foreachsample,atleast

threecurveswereplottedtocheckthereproducibility.Impedance measurementswereperformedunderpotentiostaticconditionsat Ecorrwitha15mVpeak-to-peaksinusoidalperturbation.Frequency

wassweptdownwardsfrom65kHzto3mHzwith9pointsper decade.Severalimpedancediagramswererecordedasafunction oftimerangingfrom3hto168h.Allimpedancemeasurements wererepeatedthreetimestocheckthereproducibility.

The corrosion behaviourof the Al/Cu assembly wasstudied bylocalelectrochemicalimpedancespectroscopy(LEIS).The mea-surementswerecarriedoutwithaSolartron1287Electrochemical Interface,a Solartron1255B frequencyanalyser anda Scanning Electrochemical WorkstationModel 370(Uniscan Instruments). Thismethodusedafive-electrodeconfiguration.Theprobe(i.e., abi-electrodeallowinglocalcurrentdensitymeasurements)was steppedacrossaselectedareaofthesample.Theanalysed part had anareaof 8mm×14mmandthestepsizewas500mmin thexandydirections.Mapswereobtainedatafixedfrequency, choseninthepresentcaseat10Hz,andadmittancewasplotted ratherthanimpedancetoimprovethevisualizationoftheresult [28].Localimpedancediagramswererecordedoverafrequency rangeof65kHz–3Hzwith8pointsperdecade.Spectrawere plot-tedforthe2cross-sectionsoftheassemblyshowninFig.1bandc fromtheCuparttotheAlpartwiththeoriginofaxisbeingtheAl/Cu interface.Thetimetorecordallthelocalimpedancediagramswas lowerthan60min.ForalltheLEISmeasurements,thespatial reso-lutionwasabout1mm2,i.e.theanalysedsurfacewasabout1mm2

whenalocalimpedancediagramwasplotted[27].Fortheassembly

withcavities(Fig.1b),thecavitiescorrespondedto20%ofthe ana-lysedsurfacesothattheeffectivemetallicsurfacewasonly80%of theanalysedsurface(analysisperformedonthecross-section per-pendiculartothecableaxis).Inthefollowing,forLEISresults,the impedancevalues(incm2)arenotcorrected.Therefore,forthe

assemblywithcavities,theimpedancevaluesareoverestimated withanerrorofabout20%ifonlythesurfaceexposedtothebulk solutionistakenintoaccount.

2.3. Surfacecharacterization

AA1370surfaceswereobservedbeforeandafterthe electro-chemicaltestsbyusingaNikonEclipseMA200opticalmicroscope (OM).ALeo435VPscanningelectronmicroscope(SEM)wasused tovisualizetheAl/Cuassemblyafterdifferentexposuretimesto theelectrolyticsolutionandtoobtainabetterdescriptionofthe corrosionmorphology,particularlyattheAl/Cuinterface.Forall theobservations,thesampleswereremovedfromtheelectrolyte aftertheelectrochemicaltests,rinsedwithdeionised waterand thenair-dried.

3. Experimentalresultsanddiscussion

First, the corrosion behaviour of the cable, as compared to the strand sample, was studied by combining stationary and impedancemeasurements.Then,attentionwaspaidtothe corro-sionbehaviouroftheAl/Cuassembly.

3.1. ElectrochemicalbehaviouroftheAA1370cable

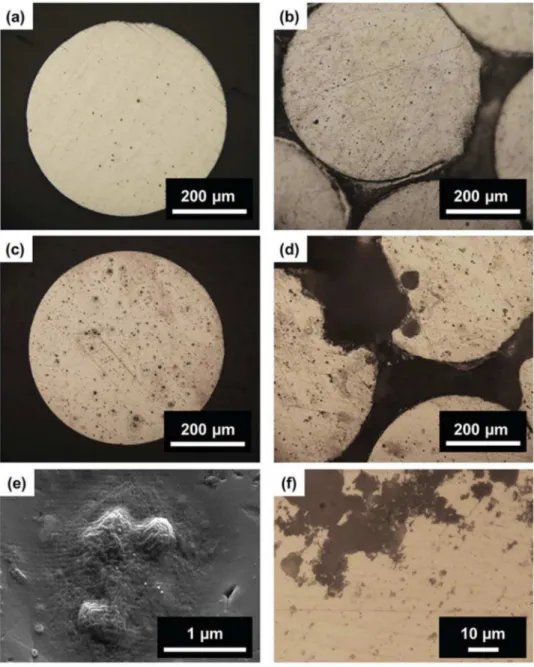

Fig.2showsOMobservationsofastrandandofthecableafter twoexposuretimes(3hand168h)totheaggressivesolutionat theircorrosionpotential.Forbothsamples,aweakdissolutionof thematrixaroundtheFe-richparticles,identifiedasAl3Fe

Fig.2.Opticalmicroscope(OM)observationsofthestrandandofthecableafter:(a,b)3hofimmersionand(c,d)168hofimmersionatEcorrin0.1MNa2SO4+0.001MNaCl.

(a)and(c)correspondtothestrand,(b)and(d)tothecable.(e)SEMobservationofcorrosionphenomenaoccurringattheAl3Feintermetallicparticles.(f)close-uponthe

corrosionfilamentsobserved.

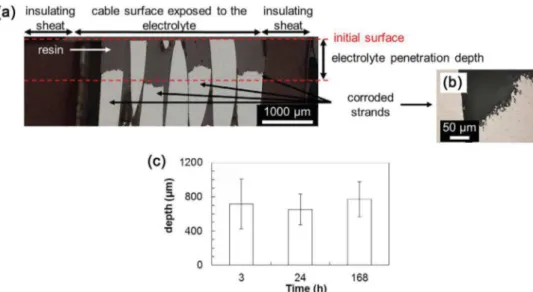

bshowedthatafter3hthematrixdissolutionaroundthe inter-metallicparticleswasmoreextendedforthecablethanforthe strand.After168hofimmersion(Fig.2candd),asignificant dis-solutionofthematrixaroundtheFe-richparticles(Fig.2e)canbe seenonthewholesurfaceforbothsamples,andinaddition,for thecable,largepitssurroundedbyfinefilaments(Fig.2f)werealso observedattheperipheryofthestrands.Thesecorrosionfeatures, inagreementwithliteraturedata,accountedforthepenetration oftheelectrolyteinsidethecableleadingtoaconfinedmedium andcrevicecorrosion phenomenon[10,11].OMobservations of cross-sections parallel to the cable axisafter various exposure timestothechloride-containingsulphatesolutioncorroborated thisassumptionandallowedthedepthofthecorrodedzoneto bemeasured(Fig.3a).Itwasassumedtobeagoodindicationof theelectrolytepenetrationdepth.Inordertomeasurethedepthof thecorrodedzone,thecorrosiondamagewasenhancedby polar-izingat−700mV/SCEfor5minthesamplesaftertheexposureat Ecorr(Fig.3aandb).Theelectrolytepenetrationdepthwasfoundto

becomerapidlyindependentoftheexposuretime,reachingabout 800mmafter3hofexposure(Fig.3c).

Fig.4 reports Ecorr values versus exposuretime tothe

elec-trolyteforthestrandsampleandthecable.Forthestrandsample, Ecorr stabilized rapidly and an almost stationary value(around

−600mV/SCE)wasobtainedafter3hofimmersion.Onthe con-trary, for the cable, Ecorr decreased significantly towards more

negativevaluesduringimmersionwhichwasinagreementwith thedifferencesincorrosionmorphologyobservedbetweenthetwo samples(Fig.2).Fig.5showsthepolarizationcurvesforthestrand sampleandthecableobtainedafter3hofexposuretothe chloride-containingsulphatesolution.Forthecable,thecurrentdensities werecalculatedbytakingintoaccount(i)onlythecross-sections ofthe50 strands constitutiveof thecable,i.e.only thesurface exposedtothebulksolution(S=0.11cm2,nocorrectedsurfacein

Fig.5)and(ii)boththecross-sectionsandthelateralsurfaceof the50strandsona800mmdepth,i.e.boththesurfacesexposed tothebulkand toaconfinedelectrolyte(S=0.76cm2,corrected

Fig.3.(a)OMobservationofacablecross-section(paralleltothecableaxis)after3hofexposuretothe0.1MNa2SO4+0.001MNaClsolutionfollowedbypolarizationfor

5minat−700mV/SCE;(b)close-uponacorrodedstrandinsidethecable;(c)electrolytepenetrationdepthversustheexposuretime.

Fig.4.VariationofEcorrduringimmersionin0.1MNa2SO4+0.001MNaClforthe

strandsampleandthecable.

Fig.5.Polarizationcurvesofthestrandsampleandthecableobtainedafter3h ofimmersionatEcorrin0.1MNa2SO4+0.001MNaCl.Scanrate=0.07mVs−1.For

thecable,thecurve‘nocorrectedsurface’onlytakesintoaccountthecablesurface exposedtothebulk(S=0.11cm2);the‘correctedsurface’curvetakesintoaccount

boththesurfaceexposedtothebulkandthatexposedtotheconfinedmedium insidethecavities(S=0.76cm2).

surfaceinFig.5).Forboththestrandsampleandthecable,the cathodicbranch,correspondingmainlytotheoxygenreduction, wassimilar.Forthestrandsampleandthecable,Ecorrvalueswere

−580mV/SCEand−730mV/SCErespectively.Theanodicdomain wascharacterizedforthestrandsample bya passivityplateau, withpassivecurrentdensitiesofabout4.10−4mAcm−2,followed

byabreakdownpotentialat500mV/SCEassociatedwith,first,a slowincreaseoftheanodiccurrentdensitiesandthenasharper one.Thiscouldbeassociatedto,first,anincreaseofthe dissolu-tionrateofthematrixsurroundingtheFe-richparticlesandthen topittingcorrosion.Besides,thesignificantcurrentfluctuations observedafterthesharpincreaseofthecurrentdensities consti-tutesacharacteristicfeatureofthepittingcorrosion.Forthecable, ashortpseudo-plateauwasobservedandtheanodiccurrent densi-tieswereabout2.10−3mAcm−2(correctedsurface).Whateverthe

surfacetakenintoaccount,thecurrentdensitieswerehigherforthe cable,ascomparedtothestrandsample;thiscouldbeassignedto adissolutionprocessratherthanapassivityprocess.Abreakdown potentialwasthenobservedat−550mV/SCEfollowedbyasharp increaseoftheanodiccurrentdensities.Alltheresultsshoweda lowercorrosionresistanceforthecableascomparedtothestrand sample.Thedifferencesincorrosionbehaviourbetweenthetwo sampleswererelatedtothepenetrationoftheelectrolyteinsidethe cablecavitiesleadingtotheformationofaconfinedandthenmore aggressiveelectrolyte.Thisconfirmed,forthecable,theoccurrence ofbothpittingcorrosiononthesurfaceexposedtothebulk solu-tionandcrevicecorrosiononthesurfaceexposedtotheconfined mediuminside thecavities. Thehigheranodiccurrentdensities observedforthecablewererelatedtotheprogressive modifica-tionoftheelectrolytetrappedinsidethecavitiesandsubsequent dissolutionphenomenon.

Impedance measurements were performed for the strand sampleandthecableafterdifferentexposuretimestothe chloride-containingsulphatesolution.Fig.6showsthediagramsinBode (Fig.6a) and Nyquist (Fig. 6b) coordinates for thestrand sam-ple. After3hand 24h of immersion, the impedance diagrams arecharacterizedbytwotimeconstants.Thefirsttimeconstant (60kHz–1Hz)wasassociatedtotheresponseofthepassivefilm, whilethesecondtimeconstant(1Hz–100mHz)wasattributedto thechargetransferprocessand totheoxygenreductiononthe passivefilminagreementwithliterature[27].Impedance mea-surementsperformedatEcorrinadeaeratedelectrolyte(resultsnot

Fig.6.Electrochemicalimpedancediagramsobtainedforthestrandsample–(a) Bodeand(b)Nyquistcoordinates–afterdifferentexposuretimesatEcorrto0.1M

Na2SO4+0.001MNaCl.

at low frequencies and no modification in the high frequency domain.Thisconfirmedtheattributionofthelowfrequencytime constanttotheoxygenreduction.After168hofimmersion,the impedancediagramshowedonlyonetimeconstantwithalower resistancewhichcouldbeassociatedtothecorrosionofthealloy, i.e.tothechargetransferprocess.Suchanevolutionofthediagrams wasinagreementwiththeOMobservations(Fig.2c),i.e.the disso-lutionofthematrixsurroundingtheFe-richparticlesduetooxygen reductionontheintermetallicsand subsequentalcalinizationof theelectrolyte for increasingimmersion times. The impedance diagramsobtainedforthecable(Fig.7)wereclearlymodifiedas compared tothose obtainedfor the strandsample. Theresults arepresented by takinginto account thetotal surface exposed totheelectrolyte(the surfaceexposedtothebulksolutionand thatexposedtotheconfinedmediumtrappedinsidethecavities). TheNyquistdiagram(Fig.7b)wasconstitutedbyastraightlinein thehigh-frequencydomainfollowedbyasemicircle.Thistypical shapecanbeassociatedtotheoxygendiffusioninaporoussystem [30–33]inagreementwiththepenetrationoftheelectrolyteinside thecablecavities.Theflattenedsemicirclemayoriginatefromthe cavityshape [34].Theimpedancevalues forthecablewereten timessmallerthanthoseobtainedforthestrandsamplein agree-mentwiththedifferencesincorrosiondamagebetweenthetwo sampleswhichhighlightedtheinfluenceoftheelectrolyte pene-trationthroughthecavitiesofthecable.For168hofimmersion,a decreaseoftheimpedancewasobservedand,inthehigh-frequency domain,atimeconstantappearedwhichcouldbeassociatedtothe corrosionofthealloyintheconfinedmedium[35,36].Additional experiments(results notshown) wereperformedwitha cross-sectionofthecableforwhichthecavitieshadbeensealedwitha resinbyforcingtheresintopenetrateintothecavitieswitha vac-uumsystem.Theimpedancediagramobtainedforthecablewith sealedcavitiesafterimmersionintheaggressivesolutionandthat ofthestrandsampleweresuperimposed.Thiswasinagreement withcommentsintheexperimentalpartandconfirmedthatthe corrosionbehaviourofthecablewascontrolledbythepenetration oftheelectrolyteinsidethecable.

Fig.7.Electrochemicalimpedancediagramsobtainedforthecable–(a)Bode and(b)Nyquistcoordinates–after differentexposuretimesatEcorr to0.1M

Na2SO4+0.001MNaCl.Theimpedancevaluestakeintoaccountboththesurface

exposedtothebulkandthatexposedtotheconfinedmediuminsidethecavities (S=0.76cm2).

Equivalent electrical circuits are frequently used to extract parametersassociatedwiththeimpedancediagrams.Inthepresent study,thedifferentsetsofimpedancemeasurementsperformed allowedtheinterpretationofthedifferenttimeconstantsin agree-mentwithliteraturedataandrelevantparametersweredefined. Forthestrandsample,relevantparametersweretheoxidefilm resistance(Rox)andthechargetransferresistance(Rt).Theywere

directlymeasuredontheimpedancespectra.Further,among rel-evantparameters,aconstant phaseelement(CPE)isoftenused insteadofa capacitance totakethenon-ideal behaviourofthe interfaceintoaccount.TheCPEisgivenby:

ZCPE=

1

Q (jω)˛ (1)

where ais related to theangle ofrotation of a purely capaci-tivelineonthecomplexplaneplotsandQisin−1cm−2s˛.In

thepresentstudy,aandQweredeterminedusingthegraphical methodproposedbyOrazemetal.[37].Forthecable, consider-ingthecomplexityofaporoussystem,thepolarizationresistance (Rp)wasassumedtoallowthecorrosionresistanceofthecableto

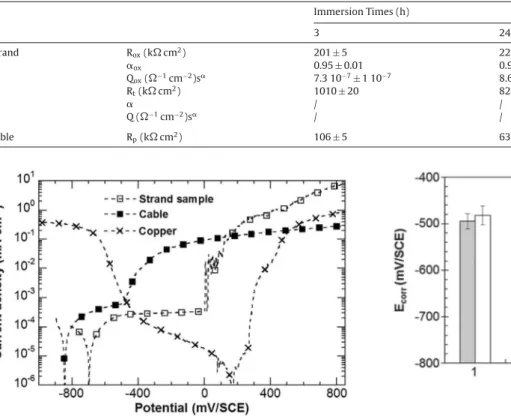

becomparedtothatofthestrandsample.Fig.7ashowedthatthe impedancemoduluswasquitestableforfrequencieslowerthan 10mHz;therefore,theimpedanceatlowfrequency(3mHz)was measuredandusedtoevaluatethecorrosionresistanceofthecable. TheimpedanceparametersarereportedinTable1.

Forthestrandsample,duringthefirst24hofimmersion,aox

remainedconstantandequal to0.95. ThevaluesofQox slightly

increasedfrom7.310−7−1cm−2s0.95to8.610−7−1cm−2s0.95.

Theaox andQox valuesaccountedforthepresenceofapassive

layer.ThevariationofQoxwithincreasingimmersiontimecould

berelatedtotheevolutionofthethicknessand/orofthe chemi-calcompositionofthepassivefilminrelationwiththedissolution ofthematrixaroundtheintermetallics.Duringthefirst24h,the

85 Table1

Parametersobtainedfromtheimpedancediagramsforthestrandsampleandforthecableafterdifferentimmersiontimesin0.1MNa2SO4+0.001MNaClsolution.Forthe

cable,theimpedancevaluestakeintoaccountboththesurfaceexposedtothebulkandthatexposedtotheconfinedmediuminsidethecavities(S=0.76cm2).

ImmersionTimes(h) 3 24 168 Strand Rox(kcm2) 201±5 220±5 / aox 0.95±0.01 0.95±0.01 / Qox(−1cm−2)sa 7.310−7±110−7 8.610−7±110−7 / Rt(kcm2) 1010±20 821±10 324±5 a / / 0.94±0.01 Q(−1cm−2)sa / / 4.2510−6±110−6 Cable Rp(kcm2) 106±5 63±5 27±2

Fig.8. PolarizationcurvesoftheAA1370strandsample,theAA1370cableandthe pureCuconnectorafter3hofimmersionatEcorrin0.001MNaClsolution.

corrosionbehaviourofthestrandsamplewascontrolledbythe presenceof theoxidefilmwithhighvaluesof bothRox andRt

while,for168hofimmersion,theelectrochemicalbehaviourwas controlledbythecorrosionprocesses(decreaseoftheRtvalues).

Forthecable,thelowRpvalueswereinagreementwiththelow

corrosionresistanceofthecableascomparedtothestrand sam-ple;moreover,thedecreaseofRpwithincreasingimmersiontime

wasinagreementwiththeextentofthecorrosiondamagerelated tothepenetrationoftheelectrolyteinsidethecableandtothe crevicecorrosionphenomenaonthesurfaceexposedtothe con-finedmediumwhilepittingoccurredonthesurfaceexposedtothe bulk.

3.2. Electrochemicalbehaviouroftheassembly 3.2.1. Preliminaryexperimentsandobservations

Apreliminarystudywasperformedin0.001MNaClto charac-terizeseparatelythecorrosionbehaviourofAl(i.e.AA1370)andCu inthesamesolutionasthatusedfortheLEISmeasurements.First, theanodicbranchofthepolarizationcurvesfor theAlsamples (strandsampleandcable)andthecathodicandanodicbranches forpureCuwereobtained(Fig.8).ComparisonofFigs.5 and8 showedthattheglobalshapeofthecurvesfortheAlsampleswas thesameindependentlyoftheelectrolyte.Forthestrandsample, a600mV-longplateaucorrespondingtoapassivityplateauwith lowanodiccurrentdensities(3.10−4mAcm−2)wasobservedand

followedbyanabruptincreaseofthecurrentassociatedtopitting corrosion.Forthecable,aplateauwasalsoobserved;itwas bet-terdefinedthaninsulphateandchloride-containingsolutionsbut, again,correspondedtohigheranodiccurrentdensitiesthanforthe strandsampleandwasconsideredasapseudo-passivityplateau. Itwasrapidlyfollowedbyasharpincreaseoftheanodiccurrent densitiesassociatedtobothpittingandcrevicecorrosionas

previ-Fig.9. VariationofEcorrduringimmersionin0.001MNaClsolutionfortheAl/Cu

assemblieswithandwithoutcavities.

ouslyexplained.Asobservedinthechloride-containingsulphate solution,thebreakdownpotentialassociatedtotheincreaseofthe anodiccurrentdensitieswasmorenegativeforthecable(pitting andcrevicecorrosion)thanforthestrandsample(pitting corro-sion) whichshowedthelowercorrosionresistanceof thecable ascomparedtothestrandsample.Inthe0.001MNaClsolution, thebreakdownpotentialwas10mV/SCEand−500mV/SCEforthe strandsampleandthecable,respectively.Then,itcanbeseenfrom Fig.8thatthecorrosionpotentialofpureCuwasmorepositive (200mV/SCE)thanthoseofthestrandsample(−700mV/SCE)and thecable(−850mV/SCE)showingasexpectedthat,intheAl/Cu assembly,pureCuwillbethecathodeandtheAlsampleswillbe theanode[20,21,38–40].FromtheanodiccurvesoftheAlsamples andthecathodiccurveofCu,thecommonpotentialmeasured,in thecaseofagalvaniccouplingbetweenthetwometalswiththe samesurfacearea,wouldbeabout−400mV/SCEforanAlstrand sample/Cuassembly,and−500mV/SCEforanAlcable/Cu assem-bly.Itwasworthnoticingthat,fortheassembliesinvestigatedhere andasshowninFig.1,theratioSCu/SAl(SCuandSAlarethesurface

areasexposedtotheelectrolyteintheassemblyrespectivelyfor CuandAl)wassignificantlyhigherthan1.Therefore,thecommon potentialshouldbeshiftedtowardsmorepositivevaluesthanthose previouslyestimated(withthesamesurfacearea).FromFig.8,it canbeclearlyseenthat,in0.001MNaCl,thecommonpotentialwas inthelocalizedcorrosion(pittingandcrevicecorrosion)regimefor thecable,whereas,dependingontheratioSCu/SAl,itcouldbeinthe

passiveregimeforthestrandsample.Thismeantthatasevere cor-rosiondamagewasexpectedforthecablewhencoupledwithCu. Thissuggestedalsothatdifferencesshouldbeobservedbetween thetwotypesofassembly,i.e.withandwithout(allthestrands con-stitutiveofthecablebeingweldedtogether)cavities,asdescribed inFig.1.

Fig.10.OpticalmicroscopeobservationsofthecorrosiondamagefortheAl/Cuassembliesafter(a,b)3hand(c,d)168hofimmersionatEcorrina0.001MNaClsolution:

assembly(a,c)withoutand(b,d)withcavities.(e)SEMmicrographoftheAl/Cuinterfaceoftheassemblywithoutcavitiesafter24hofimmersionin0.001MNaClsolution (tiltof70◦).

Fig.9showedEcorr valuesversusimmersiontime in0.001M

NaClforthetwotypesofassembly.Asexpected,Ecorrvalueswere

betweenthoseoftheAlcableandCu.Forbothassemblies,Ecorr

valuesdecreasedwithincreasingimmersiontimewhichcouldbe relatedtocorrosiondamage.Duringthefirst24h,Ecorrvalueswere

thesameforthetwotypesof assembly;theydecreasedslowly from−500mV/SCEto−600mV/SCE.After24hofimmersion,Ecorr

oftheassemblywithoutcavitiesstabilizedaround−600mV/SCE, whereas,fortheassemblywithcavities,Ecorrmovedtowardsmore

negativevaluesandreached−770mV/SCEafter168hof immer-sion.ThisvariationofEcorrsuggestedthat,foranimmersiontime

longerthan24h, thecorrosiondamage wasmoreextended for theassemblywithcavitiesandunderlined,asalreadydiscussed, thatthepresenceofcavitiesinthecablemodifiedthecorrosion processes.

The corrosiondamages for thetwo types of assembly were observedbyOMandSEMaftershortimmersiontimes(3hand24h) andlongimmersiontime(168h)in0.001MNaCl(Fig.10;results areonlygivenfor3hand168h).Independentlyoftheimmersion time,AlpartwascorrodedwhiletheCusurface exposedtothe bulksolutionremainedsafe.Forashortimmersiontime,no signif-icantdifferencewasobservedbetweenthetwotypesofassembly (Fig.10aandb).After168hofimmersion,significantdifferences wereobservedfortheAlpartdependingonthepresenceornot ofcavities(Fig.10candd).Fortheassemblywithoutcavities,OM observationsshowedthepresenceofpitsandnumerousfine fila-mentsaroundthepitsfortheAlpart(Fig.10c).Fortheassembly withcavities,aseverecorrosiondamageoftheAlpartwasobserved withnot onlypitsobservedonthesurfaceexposedtothebulk solutionbutalsosomestrandsconstitutiveofthecablecompletely dissolvedoverseveralhundredsofmicrometersindepth.These

corrosionfeatureswereinagreementwithpittingcorrosion phe-nomenaoccurringonthesurfaceexposedtothebulksolutionwhile crevicecorrosionoccurredinthecavities[38].Moredetailed atten-tionwaspaidtotheAl-Cuinterface.Forbothassemblies,corrosion products(blackareasinFig.10candd)wereclearlyobservedatthe Al/CuinterfaceandspreadallovertheAlpartfortheassemblywith cavities(Fig.10d).Fig.10eshowsaSEMmicrographoftheAl/Cu interfaceafter24hofimmersionfortheassemblywithout cavi-ties.AttheAl/Cuinterface,acrevicewasclearlyvisibleandalsothe Aldissolution.Suchacrevicewasalsoobservedfortheassembly withcavities:itwasevenmorevisible.Similarfeaturewasalready observedforaAl/Cumodelcouple[19].ThisshowedthatforCu, eventhoughnocorrosiondamagewasobservedonthesurface exposedtothebulksolution,corrosionphenomenaoccurredon theverticalwallinsidethecrevice,referringtocrevicecorrosion processes[20,21].Thus,forbothassemblies,theinitialstepofthe corrosionprocesswasthedissolutionoftheAlpartattheAl/Cu interfaceduetothealkalinisationlinkedtotheoxygenreduction reactionontheCupart[19].Theelectrochemicalreactionsthat justifythealuminiumcorrosionwereasfollows[38,40–42]:

Cathodic(ontheCusurfaceexposedtothebulksolution):

O2+2H2O+4e−→4OH− (2)

Anodic:

Al→ Al3++3e− (3)

2Al+6H20 →2Al(OH)3+3H2 (4)

Al(OH)3+OH−→ [Al(OH)4]− (5)

With increasing immersion time, in the crevice, hydrolysis of cationscan beassumed and asa consequencethe chemical

Fig.11. Admittancemapsobtainedafter24hofimmersionatEcorrin0.001MNaCl

solutionat10HzabovetheAl/Cuassemblies:(a)withoutcavitiesand(b)with cav-ities.Admittancevaluesarecalculatedtakingintoaccountananalyzedsurfaceof 1mm2.

compositionoftheelectrolyteattheAl/Cuinterfaceshouldvary significantlywithadecreaseofpHasshownbyShietal.[40].This canbeascribedtothereactionofAldissolutionandhydrolysis[40]: Al+nH2O→Al(OH)n3−n+nH++3e−,n=1–3 (6)

Therefore,inthecreviceformedattheAl/Cuinterface,thepH gotmore acidicwhichshouldpromoteacrevicecorrosion phe-nomenonforCu.Ontheopposite,farfromtheAl/Cuinterface,Cu wasincontactwiththebulksolutionwhereoxygenispresent[21] leadingtoanon-corrodedsurface.FortheAlpart,fortheassembly withoutcavities,pittingcorrosionwasobserved.Concerningthe assemblywithcavities,pittingcorrosionwasobservedontheAl surfaceexposedtothebulksolutionandcrevicecorrosionoccurred inthecavitiesexistingbetweenthestrandsduetothe penetra-tionoftheelectrolyteinsidethecavities.Therefore,thecorrosion productsobservedshouldincludebothcopperoxides,aluminium oxidesandhydroxides[20,38,40,42].Håkanssonetal.showedthat themaincorrosionproductsformedduringgalvaniccorrosionof aluminium/carbonsystemsin0.6MNaClwasAl(OH)3,presented

asagelatinoussubstanceinthecrevicesbetweentheAlwires[43]. TheseauthorsalsoshowedthatAl(OH)3shouldcontroltherateof

thecorrosionprocesseswhichshouldexplaintheplateauobserved onthepolarizationcurvesforthecableafterthebreakdown poten-tial(Fig.8).

3.2.2. LEISstudyoftheassemblies

LEISwasfirstusedinmappingmode.Mapsobtainedat10Hzfor theassemblieswithandwithoutcavities,after24hofexposurein a0.001MNaClsolutionareshowninFig.11.Forbothsamples,the admittancevaluesarehigher(i.e.,lowerresistance)ontheAlpart whichwasduetothegalvaniccouplingbetweenAl(anode)and Cu(cathode).Moreover,heterogeneousvaluesoftheadmittance

wereobservedontheAlpartinaccordancewithpittingcorrosion processes,aspreviouslyshown.ComparisonofFig.11aandbdid notshowsignificantdifferencesbetweenthetwotypesofassembly inagreementwithEcorrmeasurements(Fig.9).

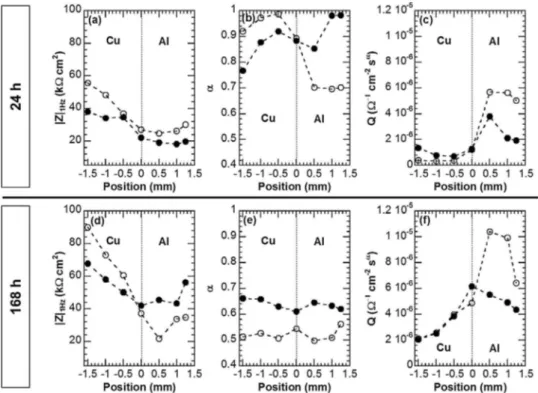

Then, localimpedance spectrawerecollected after24hand 168hofimmersionforthetwotypesofassembly(Fig.12,Nyquist coordinates).

First,itcanbeseenthatimpedancevaluesontheAlpartfor theassemblywithcavitiesarehigherthanthosefortheassembly withoutcavities.Asexplainedintheexperimentalpart,impedance valuesontheAlpartareoverestimatedfortheassemblywith cavi-ties.Theerroronthemeasurementswasestimatedtobeabout20% byconsideringonlythesurfaceexposedtothebulksolution.Ifthe surfaceexposedtotheconfinedelectrolyteinthecavities (consid-eringthesurfaceintheplaneparalleltothecableaxis)istakeninto account,thiserrorshouldbereducedbecausetheexposedsurface wouldbeincreased.Nevertheless,despitetheseinaccurate mea-surements,itwashelpful,forbothAl/Cuassemblies,tostudythe changesobservedforthelocalimpedancediagramsversus immer-siontimeandtocomparetheelectrochemicalresponseoftheAl partandtheCuparttodescribetheinfluenceofthecavitiesonthe corrosionbehaviouroftheAl/Cuassembly.

Then,forbothassemblies,theimpedancevaluesafter24hof immersion (Fig. 12a and b) were higher on the Cu part, then decreasedwhentheprobemovedtowardstheAl/Cuinterface,and decreasedagainwhentheprobewasovertheAlpart.Suchan evo-lutionoftheimpedanceasafunctionofthepositionoftheprobe wasinagreementwiththegalvaniccouplingbetweenAlandCu. After24hofimmersion,pittingcorrosionoccurredontheAlpart (Fig.10).Fortheassemblywithcavities,thediagramsplottedfor theCupart(redcurves inFig.12)aresignificantlymodified in thelowfrequencyrange ascomparedtothoseobtainedforthe assemblywithoutcavities.Theirglobalshapesuggesteda diffusion-controlledelectrochemicalprocess inrelationwiththecathodic reactionofoxygenreductionontheCupart.After168hof immer-sion,thediffusion-controlledprocesswasevenmoremarkedon thediagramsfortheassemblywithcavities(Fig.12d)andcouldbe alsonotedfortheassemblywithoutcavities(Fig.12c).This conclu-sioncouldberelatedtothoseofHåkanssonetal.whoshowedthat, foraAl/carboncouple,theratecontrollingmechanismwassolely themasstransportofoxygenthroughthegelatinousAl(OH)3inside

thecrevice[43].

In order to quantitatively analyse the LEIS diagrams, three parametersweregraphicallyextracted:theCPEvalues(aandQ) andthevaluesoftheimpedancemodulusat1Hz(|Z|1Hz).Fig.13

showsthevariationoftheseparametersforeachdiagramobtained overtheAlandCuparts.Independentlyoftheassemblyandof theimmersiontime,|Z|1HzvaluesfortheCupartwerehigherthan

thosefortheAlpart,whichconfirmedthedifferencesin reactiv-ity betweenthetwo metals whentheywerecoupled(Fig.13a, d).On theCupart,thelow frequency rangewasrelated tothe diffusionprocesslinkedtotheoxygenreduction(Fig.12). What-evertheassembly,theincreaseof|Z|1Hzbetween24hand168hof

immersionwasingoodagreementwiththeshiftofthecorrosion potentialsmeasuredfortheassembliestowardsmoreandmore negativevaluesfrom24hto168hofimmersion(Fig.9):thiswas linkedtoamoreandmoresignificantcathodicpolarizationforthe Cupart.Whentheimmersiontimeincreased,inagreementwith thecorrosionpotentialvalues measuredforthetwoassemblies, thedifferencesin|Z|1HzvaluesbetweentheAlandCupartswere

evenmoremarkedfortheassemblywithcavities.After168hof immersion,|Z|1HzvaluesmeasuredontheAlpartfortheassembly

withcavitieswerelowerthanthoseoftheAlpartforthe assem-blywithoutcavities.Thiswasexplainedbytakingintoaccountthe increaseoftheelectrochemicalprocessesina confinedmedium previouslyshowedforthecable:theeffectofthegalvaniccoupling

Fig.12.Localimpedancespectraobtainedafter(a,b)24hand(c,d)168hofimmersionatEcorrin0.001MNaClsolutionfordifferentpositionsofthebi-electrodeabovethe

Al/Cuassemblies:(a,c)withoutcavitiesand(b,d)withcavities.Impedancevaluesarecalculatedtakingintoaccountananalyzedsurfaceof1mm2.

Fig.13. Variationoftheparameters((a)and(d)|Z|1Hz,(b)and(e)aand(c)and(f)Q)obtainedfromthelocalimpedancespectraafterdifferentexposuretimesin0.001M NaClandfordifferentpositionsofthebi-electrodeovertheAl/Cuassemblies:(d)withoutcavitiesand( )withcavities.Impedancevaluesarecalculatedtakingintoaccount ananalyzedsurfaceof1mm2.

wasmoreandmoremarkedwithincreasingimmersiontimefor theassemblywithcavities.

ThedifferencesinreactivitybetweenCuandAlfromonepart, andbetweenthetwoassembliesfortheotherpart,wereconfirmed bythevariationofaandQwithincreasingimmersiontime.After 24hofimmersion,thestrongreactivityattheAl/Cuinterfacewas

showedwithboththedecreaseofaandtheincreaseofQinthezone whereSEMmicrographies(Fig.10e)showedacreviceontheAlpart. Thisevolutionwasmoremarkedforanassemblywithcavitiesin relationwithalowercorrosionresistanceoftheAlpartduetothe penetrationoftheelectrolyteinsidethecavitiesofthecable.After 168hofimmersion,aandQvaluesconfirmedtheincreaseofthe

89 galvaniccouplingeffect.Between24hand168hofimmersion,a

valuessignificantlydecreasedinagreementwithanincreaseofthe diffusionprocessesontheCupartandastrongercorrosionforthe Alpart.Moreover,itcanbeseenthatafter168hofimmersion, avaluesarelowerforboththeCuandAlpartsfortheassembly withcavitiesascomparedtotheassemblywithoutcavities.The resultcouldbelinkedtoastrongerincreaseofQvaluesattheAl/Cu interfaceobservedfortheassemblywithcavitiesascomparedto theassemblywithoutcavities.Theresultswereingoodagreement withthepresenceoftheconfinedelectrolytewhichamplifiedthe effectofthegalvaniccouplingwhentheimmersiontimeincreased. Therefore,theLEISmeasurementsprovidedevidencethatthe corrosionbehaviouroftheAl/Cuassemblywasexplainedbyboth thegalvaniccouplingbetweentheAlandCuparts,whichenhanced thecorrosionoftheAlpart,andthepenetrationoftheelectrolyte insidethecavitiesobservedintheAlpartoftheassembly,which ledtoamoreandmoreconfinedandaggressiveelectrolytewith increasingimmersiontimesothatitenhancedthereactivityofthe AlpartandthusthegalvaniccouplingwithCu.

4. Conclusions

ThestudywasfirstfocussedonthecorrosionbehaviourofanAl (AA1370)cableascomparedtoastrand.

1.OMobservationsafterexposuretoachloride-containing sul-phatesolutionshowedamoreextendedcorrosiondamagefor thecablethanforthestrand.

2.Electrochemical measurements showed for the cable: (i) a strongerdecreaseofthecorrosionpotentialwithtimethanfor thestrand,(ii)anincreaseoftheanodiccurrentdensity associ-atedwithapseudo-passivityplateauandamorenegativepitting potentialascomparedtothestrandand(iii)impedancediagrams characteristicofaporoussystem.

3.ThecorrosionbehaviouroftheAlcablewascontrolledbythe penetrationoftheelectrolytebetweenthestrandsconstitutive ofthecable.Suchaphenomenonledtoamoreaggressive con-finedmediumwhichexplainedthelowercorrosionresistance ofthecableascomparedtothestrand.

4.Then,thecorrosionbehaviouroftheassemblybetweenanAl cableandaCuconnectorwasinvestigatedbyelectrochemical techniques,andinparticularlocalimpedancemeasurements. 5.Aldissolution occurreddue togalvaniccouplingwiththeCu

connectorandcrevicecorrosionwasobservedontheCuwalls perpendicularlytotheAl/Cuinterfaceexposedtotheelectrolyte. 6.LocalimpedancedatashowedthatthecavitiesoftheAlcable significantlyinfluencedthecorrosionbehaviourofthe assem-bly:thereactivityattheAl/Cuinterfaceandtheextentofthe corrosiondamageontheAlpartwerestrongerfortheassembly withcavities.

References

[1]Y.Yamano,T.Hosokawa,Developmentofaluminumwiringharness,SEITech. Rev.73(2011)73–80.

[2]A.Laurino,E.Andrieu,J.P.Harouard,J.Lacaze,M.C.Lafont,G.Odemer,C. Blanc,Corrosionbehaviorof6101aluminumalloystrandforautomotive wires,J.Electrochem.Soc.160(2013)5069–5575.

[3]K.Yoshida,K.Doi,Improvementofductilityofaluminumwireforautomotive wiringharnessbyalternatedrawing,ProcediaEng.81(2014)706–711. [4]S.Koch,H.Antrekowitsch,AluminumAlloysforwireharnessesinautomotive

engineering,BergHuettenmaennMonatsh152(2007)62–67.

[5]S.-I.Matsuaka,H.Imai,Directweldingofdifferentmetalsusedultrasonic vibration,J.Mater.Process.Technol.209(2009)954–960.

[6]J.W.Yang,B.Cao,X.C.He,H.S.Luo,Microstructureevolutionandmechanical propertiesofCu–Aljointsbyultrasonicwelding,Sci.Technol.Weld.Join.19 (2014)500–504.

[7]R.Rambat,A.J.Davenport,G.M.Scamans,A.Afseth,Effectofiron-containing intermetallicparticlesonthecorrosionbehaviourofaluminum,Corros.Sci. 48(2006)3455–3471.

[8]J.O.Park,C.H.Paik,R.C.Alkire,ScanningMicrosensorsformeasurementof localpHdistributionsatthemicroscale,J.Electrochem.Soc.143(1996) 174–176.

[9]O.Seri,M.Imaizumi,ThedissolutionofFeAl3Intermetalliccompoundand

depositiononaluminuminAlCl3solution,Corros.Sci.30(1990)1121–1133.

[10]J.Xu,W.Chen,Behaviorofwireinparallelwirestayedcableundergeneral corrosioneffects,J.Constr.SteelRes.85(2013)40–47.

[11]Y.Ishikawa,S.Kawakami,Effectsofsaltcorrosionontheadhesionofbrass platedsteelcordtorubber,RubberChem.Technol.59(1986)1–15. [12]J.J.Perdomo,I.Song,Chemicalandelectrochemicalconditionsonsteelunder

disbondedcoatings:theeffectofappliedpotential,solutionresistivity, crevicethicknessandholidaysize,Corros.Sci.42(2000)1389–1415. [13]S.H.Zhang,S.B.Lyon,Anodicprocessesonironcoveredbythin:dilute

electrolytelayers(I)-anodicpolarisation,Corros.Sci.36(1994)1289–1307. [14]R.Oltra,B.Malki,F.Rechou,Influenceofaerationonthelocalizedtrenching

onaluminumalloys,Electrochim.Acta55(2010)4536–4542.

[15]S.Chanel,N.Pébère,Aninvestigationonthecorrosionofbrass-coatedsteel cordsfortyresbyelectrochemicaltechniques,Corros.Sci.43(2001)413–427. [16]D.Wong,L.Swette,Aluminumcorrosioninuninhibitedethyleneglycol-water

solutions,J.Electrochem.Soc.126(1979)11–15.

[17]M.G.A.Khedr,A.M.S.Lashien,Theroleofmetalcationsinthecorrosionand corrosioninhibitionofaluminuminaqueoussolutions,Corros.Sci.33(1992) 137–151.

[18]M.G.A.Khedr,A.M.S.Lashien,Corrosionbehaviorofaluminuminthepresence ofacceleratingmetalcationsandinhibition,J.Electrochem.Soc.136(1989) 968–972.

[19]J.-B.Jorcin,C.Blanc,N.Pébère,B.tribollet,V.Vivier,Galvaniccoupling betweenpurecopperandpurealuminum,J.Electrochem.Soc.155(2008) C46–C51.

[20]C.Blanc,N.Pébère,B.Tribollet,V.Vivier,Galvaniccouplingbetweencopper andaluminuminathin-layercell,Corros.Sci.52(2010)991–995. [21]S.Joma,M.Sancy,E.Sutter,T.T.M.Tran,B.Tribollet,Incongruentdissolution

ofcopperinAl-Cualloys:influenceoflocalpHchanges,Surf.InterfaceAnal. 45(2013)1590–1596.

[22]P.DeLima-Neto,J.P.Farias,L.F.G.Herculano,H.C.DeMiranda,Determination ofthesensitizedzoneextensioninweldedAISI304stainlesssteelusing non-destructiveelectrochemicaltechniques,Corros.Sci.50(2008) 1149–1155.

[23]G.Baril,C.Blanc,M.Keddam,N.Pébère,Localelectrochemicalimpedance spectroscopyappliedtothecorrosionbehaviorofanAZ91magnesiumalloy, J.Electrochem.Soc.150(2003)488–493.

[24]S.Marcelin,N.Pébère,Synergisticeffectbetween8-hydroxyquinolineand benzotriazoleforthecorrosionprotectionof2024aluminiumalloy:alocal electrochemicalimpedanceapproach,Corros.Sci.101(2015)66–74. [25]M.Mouanga,M.Puiggali,B.tribollet,V.Vivier,N.Pébère,O.Devos,Galvanic

corrosionbetweenzincandcarbonsteelinvestigatedbylocalelectrochemical impedancespectroscopy,Electrochim.Acta88(2013)6–14.

[26]D.Sidane,E.Bousquet,O.Devos,M.Puiggali,M.Touzet,V.Vivier,A. Poulon-Quintin,Localelectrochemicalstudyoffrictionstirweldedaluminum alloyassembly,J.Electroanal.Chem.737(2015)206–211.

[27]J.-B.Jorcin,M.E.Orazem,N.Pébère,B.Tribollet,CPEanalysisbylocal electrochemicalimpedancespectroscopy,Electrochim.Acta51(2006) 1473–1479.

[28]J.-B.Jorcin,E.Aragon,C.Merlatti,N.Pébère,Delaminatedareasbeneath organiccoating:alocalelectrochemicalimpedanceapproach,Corros.Sci.48 (2006)1779–1790.

[29]N.A.Belov,D.G.Eskin,A.A.Aksenov,MulticomponentPhaseDiagrams: ApplicationsforCommercialAluminiumAlloys,firstedition,ElsevierLtd, Oxford,2005.

[30]D.D.Macdonald,Reflectionsonthehistoryofelectrochemicalimpedance spectroscopy,Electrochim.Acta51(2006)1376–1388.

[31]C.Gabrielli,M.Keddam,N.Portail,P.Rousseau,H.Takenouti,V.Vivier, Electrochemicalimpedancespectroscopyinvestigationsofamicroelectrode behaviorinathin-layercell:experimentalandtheoreticalstudies,J.Phys. Chem.110(2006)20478–20485.

[32]H.-K.Song,H.-Y.Hwang,K.-H.Lee,L.H.Dao,Theeffectofporesize distributiononthefrequencydispersionofporouselectrodes,Electrochim. Acta45(2000)2241–2257.

[33]A.Lasia,Impedanceofporouselectrodes,J.Electroanal.Chem.397(1995) 27–33.

[34]C.Hitz,A.Lasia,Experimentalstudyandmodellingofimpedanceoftheheron porousNielectrodes,J.Electroanal.Chem.51(2001)213–222.

[35]S.Marcelin,N.Pébère,S.Régnier,Electrochemicalinvestigationsoncrevice corrosionofamartensiticstainlesssteelinathinlayercell,J.Electroanal. Chem.737(2015)198–205.

[36]M.Keddam,A.Hugot-Le-Goff,H.Takenouti,D.Thierry,M.C.Arevalo,The influenceofathinelectrolytelayeronthecorrosionprocessofzincin chloride-containingsolutions,Corros.Sci.33(1992)1243–1252. [37]M.E.Orazem,N.Pébère,B.Tribollet,Enhancedgraphicalrepresentationof

electrochemicalimpedancedata,J.Electrochem.Soc.153(2006)B129–B136. [38]R.Vera,P.Verdugo,M.Orellana,E.Mu ˜noz,Corrosionofaluminiumin

copper–aluminiumcouplesunderamarineenvironment:influenceof polyanilinedepositedontocopper,Corros.Sci.52(2010)3803–3810.

R.Gravinaetal./CorrosionScience119(2017)79–90 [39]L.B.Coelho,M.Mouanga,M.-E.Druart,I.Recloux,D.Cossement,M.-G.Olivier,

ASVETstudyoftheinhibitiveeffectsofbenzotriazoleandceriumchloride solelyandcombinedonanaluminium/coppergalvaniccouplingmodel, Corros.Sci.110(2016)143–156.

[40]H.Shi,E.-H.Han,F.Liu,T.Wei,Z.Zhu,D.Xu,Studyofcorrosioninhibitionof coupledAl2Cu–AlandAl3Fe–Albyceriumcinnamateusingscanningvibrating

electrodetechniqueandscanningion-selectiveelectrodetechnique,Corros. Sci.98(2015)150–162.

[41]N.Murer,R.Oltra,B.Vuillemin,O.Néel,Numericalmodellingofthegalvanic couplinginaluminiumalloys:adiscussionontheapplicationoflocalprobe techniques,Corros.Sci.52(2010)130–139.

[42]J.Bernard,M.Chatenet,F.Dalard,Understandingaluminumbehaviorin aqueousalkalinesolutionusingcoupledtechniques:partI.Rotatingring-disk study,Electrochim.Acta52(2006),86–93.

[43]E.Håkansson,J.Hoffman,P.Predecki,M.Kumosa,Theroleofcorrosion productdepositioningalvaniccorrosionofaluminum/carbonsystems, Corros.Sci.114(2017)10–16.