“Country of birth, migration and health status: a French data analysis” (Temporary Version)

Caroline Berchet (Université Paris dauphine (LEGOS))

Florence Jusot (Université Paris Dauphine (LEGOS); Associate Researcher, Research and Information Institute for Health Economics-IRDES)

Paul Dourgnon (Research and Information Institute for Health Economics-IRDES)

Michel Grignon (Center for Health Economics and Policy Analysis, Mc Master University; and Associate Researcher, Research and Information Institute for Health Economics-IRDES)

1. Introduction :

This study explores the statistical association between migratory status, country of birth and individual health. As social health inequalities are well documented in general population in France, few studies have focused on migrant population due to the lack of information on nationality and country of birth in most of health survey. However a growing body of literature suggests not only that there is some differences in individual health between native born and immigrant population but also within the migrant population. Several mechanisms related to the migratory history, to the socio-economic status and the social integration in the host country may explain social health inequalities and health heterogeneity within the migrant population.

The first hypothesis related to the migratory history and the origin refers to the “Healthy Migrant Effect”, which suggests that the foreign born present a better health than native born population. This hypothesis, which can be considered as a selection effect, assumes that only people with a good health or initially wealthy are more able to migrate. The “Healthy Migrant Effect” is well documented by international literature and the French one but findings are not similar. Hence, in the USA, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom, immigrant population presents a better health than the native one (McDonald & Kennedy, 2004; Kennedy & al, 2006; Rubalcava & al, 2008). In France, however, results of recent studies prove that migrant or foreign population is in a worse health status than French native born population (Jusot & al, 2008; Attias-Donfut & Tessier, 2005). This selection effect can therefore be offset with time by a deleterious effect of migration which can lead to loneliness or a loose of social support. Then, to explain the observed heterogeneity in health status within the immigrant population, scholars have shown that the native country, the length of stay in the host country and the language barrier are important determinants of individual migrant health. The country of origin has actually an important implication on individual health and especially through the influence of the economic or political context and the country customs. Jusot and al (2008) have noticed that individuals emigrated from countries whose GDP per capita is low (that is second or third quartile of GDP) are more likely to

report a poor health status than individuals emigrated from countries having a higher GDP. Results are moreover similar if they introduce the country human development indicator in their analysis. In this way there is a clear protector effect of country development level on health status. Hence, this study suggests that there is a long term effect of economic situation of native country on individual health. Cultural habits (such as pattern of food consumption or medicine pattern) may also explain migrant health. Findings of Klhat and Courbage (1995) study have shown that individual emigrated from Morocco are more likely than French people to benefit from a lower death rate due to a healthy diet and a lower alcohol consumption. More recently, Gee, Kobayaski and Prus (2007) indicated that individuals residing in Canada and who are emigrated from Asia have a much higher risk to report a chronic disease. To explain this result, the above-named authors suggest that Asian people encounter difficulties in understanding the health care system or prevention programs. To explain, lastly, health disparities within the migrant population, some authors have shown that the length of stay in the host country and the language barrier are positively associated with the likelihood to report a poor health (Atias-Donfut et Tessier, 2005; McDonal and Neily, 2007; Lert, Melchior and Ville, 2007; Zambrana and al, 1994; Leclere, Jensen and Biddlecom, 1994).

Apart from mechanisms related to individual origin or migratory history, social determinant of health such as socio-economic conditions and psycho-social resources allow to understand not only health inequalities between native born and migrant population but also health inequalities within the migrant population.

Socio-economic condition influence on health is largely documented and numerous scholars have shown that the position in the social order is strongly correlated with the individual health status (Goldberg and al, 2002; Marmot and Wilkinson, 2006). Studies on migrant health emphasized that this population are more likely to be affected by unemployment, to have a lower income or a lower education level (Newbold & Danforth, 2003; Attias-Donfut and Tessier (2005); Jusot and al, 2008). A Canadian study show not only that migrant population has more unfavourable socio-economic condition but also that these determinants are more important in the explanation of migrant health than native born one (Dunn and Dyck, 2000). Note that these factors are not enough to explain individual health status and this is why a growing body of literature stresses the importance of psycho-social resources to explain health. These last kinds of determinants are related to social integration and social interaction such as social relationship or emotional and financial support. Social capital is actually considered as potential explanatory factors of health status. And yet, numerous scholars suggest that a high level of social capital enhances population health outcomes and reduces health differences (Golberg et al., 2002; Jusot, Grignon and Dourgnon, 2008; Folland, 2007; Islam, 2007). Moreover, social capital seems to be a particularly relevant health determinant for vulnerable populations, such as migrant population since it constitutes an informal insurance against health risk, it enable to reduce informational cost or to spread health norms (Putnam 1995, 2000).

Within the framework of this study, we intend to analyse links between migratory status, country of birth and health status by completing the existing literature in several ways. Apart from comparing health status between migrant population and French population, we propose to analyse more precisely health disparities according to migratory status in distinguishing first migrant generation from second migrant generation. Moreover, the analysis is refined by integrating country of origin in our estimation in order to study health heterogeneity within both group of migrant population. Hence, we attempt to explore health differences between individuals emigrated from Southern Eastern Mediterranean countries and individuals emigrated from all other countries. Lastly, to confirm health determinants proposed by previous literature we explore the influence of socio-economic condition and psycho-social resources on health status.

2. Data and Method:

The analysis is based on a population survey, representative of the French population, the Health, Health Care and Insurance Survey (ESPS: “Enquête sur la santé et la protection sociale”), coordinated by the Institute for Research and Information in Health Economics (IRDES). We use the 2006 wave which included a set of question on native country, country of birth and psychosocial resources. The survey sample, comprised of 8100 households and 22 000 individuals, is based on a random draw from administrative files of the main sickness funds to which over 90% of the population living in France belong. Individuals drawn at random from the administrative files are used to identify households. The socio-economic questionnaire is answered by one key informant in each household (aged at least 18), who needs not be the individual selected at random and self-selected voluntary. Questions on health status are collected through a self-administered questionnaire completed individually by each household member. Questions on psychosocial resources and nationality are answered by the key informant for him or her-self.

Since our main objective is to examine health differences between migrant and native population, we restrict our analysis to the population of employed individuals aged 18 to 64, who reported both their health status and their national origin (7260 individuals).

2.1. Migration status and country of birth:

To build migratory status, we use information relating to the nationality and the country of birth of individuals and those of their parents. The crossbreed between these questions allows distinguishing 3 migratory statuses: “individual born French whose parents are born in France”, “First migrant generation” and “Second migrant generation”.

First, “individual born French whose parents are born in France” represents in our analysis the reference population and it gathers individual with French nationality whether they are born in France or not and whose parents are born in France. Then, “First migrant generation” gathers

foreign individuals who are born abroad, regardless parents nationality and country of birth. And lastly, the “second migrant generation” group represents individual who are not foreigner born abroad and whose at least one parent is a foreigner born abroad. Note that a last migratory status has been created; it gathers individuals whose parent’s nationality or country of birth is not known. To analyse social health inequalities of individuals coming from Southern and Eastern Mediterranean (SEM) countries we use individual’s country of birth for the first migrant generation and then for second migrant generation the parent country of birth. Hence, we constructed an indicator named “origin” to distinguish individuals or parents who are emigrated from Turkey, Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Libya, Egypt, Israel, Lebanon and Syria from individuals or parents who have emigrated from all other countries.

Individual born French, which constitute the reference population, represent 80.4% of the sample (Table 2). 9% of the sample is composed by first generation migrant and within this group, 31.2% are emigrated from Southern and Eastern Mediterranean countries and 68.8% are emigrated from all others countries than SEM countries. Second migrant generation represents 10.2% of the sample. Within this last category, 23% have parents emigrated from SEM countries and almost 77 % have parents emigrated from all other countries. Note that first migrant generation population is on average older than the second one (49.2 years versus 45.3), itself slightly younger than the French reference population.

2.2. Health variables:

To assess the individual health we first use 2 standardised questions suggested by the WHO European Office. Self assessed health is the first one, it measures the individual perception of their health status and thus we construct a binary health descriptor opposing people reporting a “very good” or “good” general health status to people reporting a “fair”, “bad”, or “very bad” general health status. The second standardised question is an indicator of functional health which allows to measure whether individual has some activity restrictions or not. Again, we construct a binary functional health descriptor opposing people who report “having some activity restrictions for more than 6 months due to health problem” to people who does not report any activity restriction. To estimate lastly the individual health, we constructed a mental health indicator. According to the WHO, mental health can be defined “as a state of well-being in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community”1. The mental health indicator is constructed thanks to the SF-36 questions concerning the psychological health. In the survey, mental health is measured by indicators which suggest the likelihood of having a depressive trouble. The construction of a binary mental health descriptor is realised by using the “Euro-D” method (Borsch-Shupan and Al, 2005). According to this method, people having a score lower than (SF-36 Mean – (1.5 * Standard Deviation)) are considered as having a poor mental health.

1

24.9% of the sample declares having a poor self assessed health; almost 17.5% of the sample states having some activity restrictions and 7.5% are considered as being in poor mental health (Table 1).

The descriptive analysis shows some health differences according to migratory status and country of origin (Table3). On average, first generation migrants are in poorer health category than French population for the three considered indicators. Hence, among people who declare a poor self assessed health, 43.8% are first migrant generation who emigrated from SEM countries and 40.2% are first migrant generation who emigrated from all other countries whereas 26% are French population. First migrant generation has also a poorer health status than second migrant generation and again this is true for the three health indicators. Among people who declare having some functional restrictions for example, 25.6% and 25.9% are first migrant generation coming from SEM countries and all others countries respectively whereas 16.2% and 20.4% are second migrant generation whose parents emigrated respectively from SEM and other countries. Note that second migrant generation reports on average a better health than French population for the first two indicators (self assessed health and functional health) but presents a poorer mental health. For instance, among second migrant generation whose parents emigrated from SEM countries 10.4% are considered in poor mental health whereas 8.3% for French population.

2.3. Psycho-social resources measures:

Psycho-social resources, which represent a sort of social integration, can be assessed through the 3 dimensions usually used by the literature: social capital, social support and sense of control at work.

Social capital is often measured at the individual level through civic engagement, which refers to participation in collective action like association, sportive club, religious community, union or political party. Therefore, in this research social capital study is part of Putnam’s framework in which social capital “refers to features of social organisation, such as trust, norms and networks that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated action” (Putnam, 1995). For social support, we used a question which addresses if individuals have suffered from loneliness during their life. Lastly, sense of control at work which refers to the individual perception towards their position in the social order is measured via individual autonomy at work. A last indicator of social integration was used referring to the language spoken during childhood for which there are 3 modalities: “to have spoken in French”, “to have spoken in French and other language” and “to have spoken only in another language than French one”.

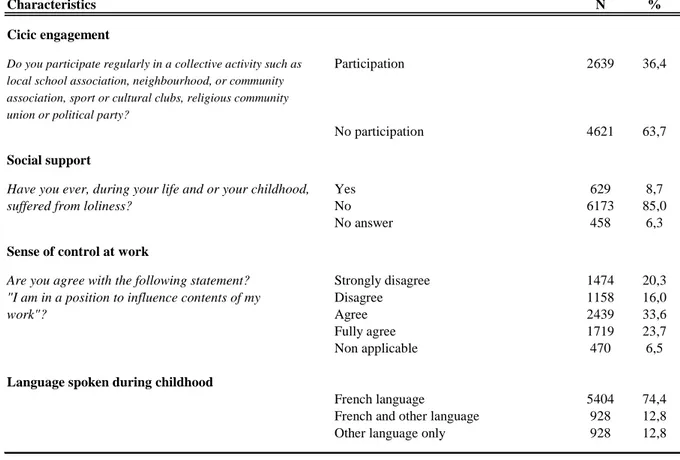

63.7 % of the sample declares not to participate to collective action like association, sportive club, religious communities, a union or a political party. 8.7% of individual states having suffered from loneliness during their live and 36.2% do not believe they have autonomy in their work (Table 4). Descriptive statistics show that individuals with a poor access to

psycho-social resources present on average a poorer health status for the three considered indicators (Table 5). Hence, individuals who do not participate to collective action are, for example, more numerous to declare a poor self assessed health than individuals having a collective participation (31.7% versus 20.5%). Similarly, individual who have suffered from loneliness contrary to people who did not, are more numerous to be considered as having a poor mental health (22.8% versus 7.6%). Descriptive statistics2 indicate also that the distribution of psycho-social resources is uneven distributed within the sample. In this way, first and second migrant generations are more numerous to not have any civic engagement, to have suffered from loneliness and not to have any sense of control at work than French population. Note that first migrant generation are also more numerous than second generation to suffer from lacking of psycho-social resources.

2.4. Socio-economic variables:

To assess the influence of socio-economic status on individual heath, educational level, occupation, socio-economic position, income and household composition are used.

Educational level is measured as follow: without certification, primary level, first level of secondary school, second level of secondary school, post secondary education and other level of education which includes missing value, foreign diploma, professional training and other education. There are four occupational statuses: active, non-working, retired and unemployed. For our analytical framework we also used the famous French “Socio Professional Category” (PCS) in which 8 groups are defined: executive (used as reference), agricultural employee, self-employed, intermediary occupations, administrative employee, business employee, skilled worker, unskilled worker, non-working. Income is measured as household income (from all sources of income), divided by the OECD equivalent scale (1 for the first household composition, 0.5 for the second and 0.3 for the third and following one). We created income quintile and a last category was built which refers to those who did not provide income information. Finally, to assess the household composition we constructed 5 categories: couple with child (used as reference), be alone, single-parent, childless couple and other household composition.

As previously, the descriptive analysis proves some differences according to migratory statuses and country of origin3. First and second migrant generations have in general more unfavourable socio-economic conditions than French population and that is confirmed for all indicators considered (educational level, occupation, PCS, income or household composition). First and second migrant generations are more numerous to have any certification or to be unemployed than French population. The socio-economic status is not homogenous within both groups of migrant population. Within the first migrant generation, individuals who have emigrated from SEM countries have a more unfavourable socio-economic situation than individuals who have emigrated from all other countries. In the same way, within the second

2 Descriptive statistics not reported. 3

generation of migrants, individuals whose parents have emigrated from SEM countries have a more unfavourable situation.

2.5. Analytic Strategy:

To analyse the link between migration, country of origin and health status, we have ran several logistics regressions aimed at studying at the same time the influence of migratory status and country of origin on the likelihood to declare a poor health status for the three considered indicators. Note that we have also introduced psycho-social resources in order to evaluate the association between social integration and health status.

First we ran a baseline logistic analysis with health as the dependent variable and entered sex, age and origin only (that is migratory status and country of origin). All socio-economic indicators were then entered simultaneously in a second model to analyse the association

ceteris paribus between self assessed health and origin. These two first models enable to

distinguish direct effect of migration and country of origin on health status from indirect effect which pass through socio-economic conditions. Thanks to these models, it is possible to assess the share of health inequalities that is explained on one hand by biological and material factor and on the other hand by migration and country of origin.

To test further the influence of psycho-social resources on health status, we lastly entered in a third model indicators representing social integration (that is civic engagement, social support, sense of control at work and language spoken during childhood). Hence, this last methodology attempts to assess the share of social health inequalities that is explained by a lack of psycho-social resources and more generally by a lack of social integration in France.

The goal of this study is exploratory in trying to find any relationship between origin and health status and more specially to assess the social health inequalities that can be explained by the fact of coming from Southern and Eastern Mediterranean countries.

Is there any association between health and migratory status? Among migratory status, is there any difference in health according to the country of origin?

3. Findings:

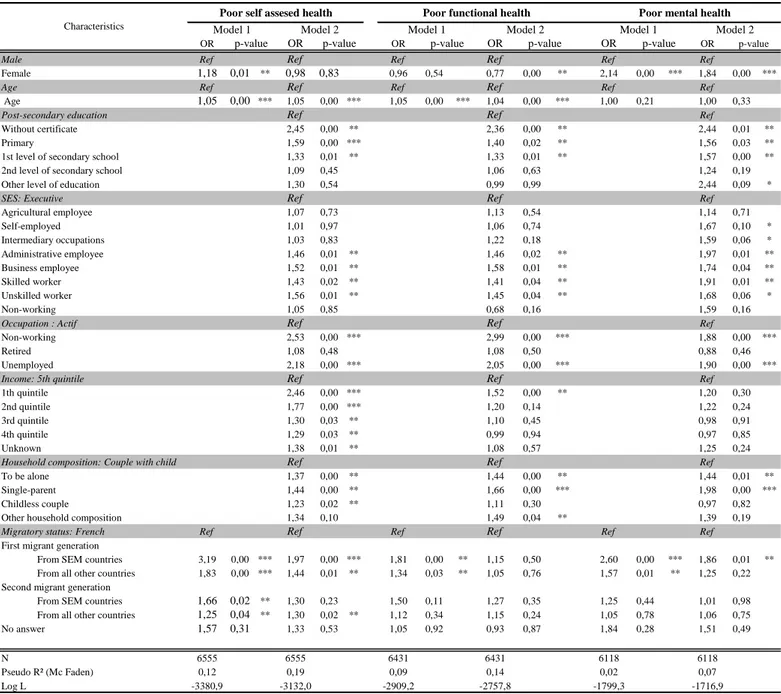

The table 6 presents the results of logistics analysis aimed at studying the individual determinant of health status and the migrant health heterogeneity according to their migratory status and their origin.

Model 1 (in which there is no control for socio-economic conditions) shows that migratory status has a significant effect on the probability of reporting poor self assessed health (column 1). First and second migrant generations have a higher probability than French population to declare a poor self assessed health and this risk is not similar among the migrant population. Individuals coming from SEM countries are more likely to be in the poorer health category,

whether they belong to the first generation group or the second one. The control for socio-economic conditions conducts to different results (model 2, column 2). First, the decrease of odds ratios associated with migratory status between model 1 and 2 shows that the migrant bad health status is partly explained by their more unfavourable socio-economic conditions. In spite of this decrease, first migrant generation still has a significant higher probability than French population to declare a poor health status. Even after control for socio-economic condition, the risk of being in the poorer health category is higher for people emigrated from SEM countries (OR equals to 1.97 and significant at 1% level) than people emigrated from all other countries (OR equals to 1.44 and significant at 5% level). This result suggests a deleterious effect of migration and origin independently of immigrant socio-economic conditions. Within the second migrant generation then, only individuals whose parents have emigrated from all other countries are more likely than French population to declare ceteris

paribus a poor self assessed status. Thus, the deleterious effect of migration independently of

socio-economic conditions is once again observed for this sub-group of second migrant generation. However, this effect is not verified for second migrant generation whose parents have emigrated from SEM countries. It seems that their poor self assessed health is entirely explained by material and biological factors.

If we focus our attention on the functional health indicator it appears that, without control for socio-economic condition, only first migrant generation are more likely to declare some functional restrictions than French population (Model 1, column 3). Again, the probability is higher for individuals who have emigrated from SEM countries (OR equal to 1.81 and significant at 5% level) than individuals who have emigrated from all other countries (OR equal to 1.30 and significant at 5% level). There is, however, no significant difference in functional health between second migrant generation and French population. After the control for socio-economic conditions (Model 2, column 4), migratory status and country of origin do not explain any more functional health which suggests that the poor functional health of first migrant generation (for both groups) is only explained by their socio-economic conditions.

Results concerning the mental health indicator are similar. Without any control for socio-economic conditions, there is no significant difference between second migrant generation and French population with regard to mental health (Model 1, column 5). Only first migrant generation has a higher probability of reporting a poor mental health than French population. The risk within this group is higher for individuals who have emigrated from SEM countries (OR equals to 2.60 and significant at 1% level) than individuals who have emigrated from all other countries (OR equals to 1.57 and significant at 5%). After control for socio-economic conditions (Model 2, column 6), only individuals who have emigrated from SEM countries are more likely to declare a poor mental health than French population (OR equals to 1.86 and significant at 5%). The decrease in this odds ratio shows that the socio-economic condition only explained a part of their poor mental health. Unlike the poor mental health of first

migrant generation emigrated from all other countries is only explained by their material living condition.

The findings of model 2 (columns 2, 4 and 6) confirm the influence of socio-economic conditions on health proved by previous studies relating to social health inequalities. The probability to declare a poor health status increases with age for the three health indicators and is higher for females than for males (except for self assessed health). All socio-economic variables have a significant effect on health and on the expected way. Individuals without any certification and those with primary education level are more likely to report poorer health status (for the three health indicators) compared to individuals with post-secondary education level and skilled or unskilled workers compared to executives. Individuals are also more likely to report a poor health when they are non-worker, unemployed or single parent. Household income is strongly significant for self assessed health but less for functional and mental health. Household income reduces the likelihood to report a poor self assessed health.

The last table (Table 7) gives the results of the second analysis where social integration indicators (that is psycho-social resources) are entered simultaneously with origin in the regression of self assessed health status, functional health and mental health (controlling for age, sex and socio-economic conditions).

Introducing psycho-social resources into the model substantially affects results and specially the influence of origin in the explanation of health status.

With regard to self assessed health, only individuals within the first migrant generation who have emigrated from SEM countries have a higher probability than French population to declare a poor health status (OR equals to 1.64 and significantly different at 5%). There is therefore a deleterious effect of origin and migration on health independently of economic conditions and social integration for this group of migrant. This likelihood does not remain significant for people emigrated from all other countries. Hence there is no more significant difference in self assessed health status between this sub-group of first migrant generation and French population. This suggests that their poor self assessed health is not only explained by their socio-economic conditions but also and mostly by their access to psycho-social resources. Despite a slight decrease in odds ratios, results concerning the second migrant generation do not change after the introduction of psycho-social resources. Second migrant generation whose parents are emigrated from SEM countries does not have a significant higher probability than French population to declare a poor health whereas the second sub-group has (OR equals to 1.25 and significant at 10% level). In this first column, all social integration indicators are strongly associated with the probability to report a poor self assessed health. To have spoken in French and other language during childhood in comparison to have spoken only in French increase the likelihood to report a poor health status (OR equals to 1.19 and significant at 10). Unlike there is no significant difference between individual who have spoken only in another language and those who have spoken in French. In addition there is a

clear correlation between the three psycho-social resources and the probability to declare a poor self assessed health status. Hence, individuals who do not have any collective participation, who disagree that they have autonomy in their work and who have suffered from loneliness, are more likely to be in the poorer self assessed health category (odds ratios significantly different from 0 at 1% level). These results confirmed previous literature on social health inequalities.

The second column of table 7 gives the results of the probability to report a poor functional health. Results are similar to the first analysis. Once again, there is on one hand no difference between first migrant generation and French population and on the other hand between second migrant generation and French population, which is consistent with Table 6 (column 4). Whereas the language spoken during childhood is not associated with functional health, the three other social integration indicators are and on the expected way. The lack of civic engagement, no sense of control at work and no social support increase the probability to report some functional restrictions. Note that odds ratios are smaller and less significant than they were for self assessed health.

With regard to mental health lastly (column 3), origin and migratory status do not explain any more mental health after introducing social integration indicators. In other words, the difference that has been noticed in the first analysis between first migrant generation who emigrated from SEM countries and French population does not remain when psycho-social resources are entered in the model. This suggests that the poor mental health of this sub-population is explained largely by a lack of social integration in France. Like for functional health indicator, the language spoken during childhood does not have any significant association with mental health but the other social integration indicators have. Hence, individuals who do not participate in collective action, who declare that they have no autonomy at work and those who have suffered from loneliness have a higher probability to declare a poor mental health.

Lastly, the analysis of the determinants of poor access to psycho-social resources4 shows that socio-economic conditions, migratory status and origin play a considerable role. Hence, individuals with lower levels of education, income and more generally with unfavourable socio-economic conditions benefit on average from less access to psycho-social resources. Similarly, migrant population tends to have less access to these resources and is less likely to be socially integrated to the society than French population. They participate significantly less often and have less emotional and social support for example.

4

5. Discussion:

This study provides some empirical evidence of the link between migratory status, country of origin and health status, controlling for other determinants of health, such as age, gender, socio-economic conditions and psycho-social resources.

Our result are consistent with several previous studies since we show that migrant population (first and second generations) are more likely to be in the poorer health category than French population. Introducing origin into the analysis enables to confirm the health heterogeneity within both groups of migrants. Individuals coming from SEM countries are more likely to be in the poorer health category (for the three health indicators) whether they belong to the first generation group or the second one.

After the control for socio-economic conditions and psycho-social resources, only individuals emigrated from SEM countries and second migrant generation whose parents have emigrated from other countries have a higher likelihood to report a poor self assessed health. Hence, this result suggests a long term effect of migration and origin which is independent of socio economic situation and social integration. This long term effect is actually determined by the country of origin and it enables to explain a part of social health inequalities in France. However, socio-economic conditions and psycho-social resources mostly explain the poor self assessed health of second migrant generation whose parents are emigrated from SEM countries and first migrant generation who emigrated from all other countries. In this way, the influence of origin is also indirect and passes through more unfavourable socio-economic conditions and a lack of psycho-social resources. Findings concerning functional and mental health show on one hand that second migrant generation are no different from French population but on the other hand it seems that socio-economic condition and psycho-social resources explain entirely the poor health of first migrant generation (mostly for individuals emigrated from SEM countries). Once again, the influence of origin on health is captured by their unfavourable socio-economic conditions and a lack of social integration.

This analysis corroborates previous studies since we also shown that psycho-social resources are strongly associated with poor health status for the three health indicators. Lacking of civic engagement, lacking of social support or autonomy at work is associated with the probability of being in the poorer health category. Furthermore, it seems that access to these resources is uneven across the population and strongly influenced by socio-economic condition, migratory status and origin.

Thus, further investigations should work on the causal pathway between access to psycho-social resources and health of migrant population. Indeed, the discrimination based on ethnicity or immigrant status is an important factor of unequal access to psycho-social resources in France and could potentially explained the poor health of this sub-population group.

N % Very good 1249 17,2 Good 3495 48,1 Fair 1505 20,7 Bad 242 3,3 Very bad 64 0,9 No answer 705 9,7

Yes, important restriction 370 5,1

Yes 903 12,4

No 5158 71,1

No answer 829 11,4

Mental health 1 Good 5572 76,8

Bad 546 7,5

No answer 1142 15,7

Note:

1. Individuals having a score lower than (SF-36 Mean – (1.5 * Standard Deviation)) are considered as having a poor mental health.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics : Health status of the sample Characteristics

Self assesed health

Functionnal restriction

N %

Migratory status and origin French 5836 80,4

First migrant generation

From SEM countries 203 2,8

From all other countries 447 6,2

Second migrant generation

From SEM countries 169 2,3

From all other countries 561 7,7

No answer 44 0,6

Characteristics

Migratory status and origin French 8,3 First migrant generation

17,3 12,6 Second migrant generation

10,4 8,7

No answer 14,3

Note: * Within the french population, 26.1% report a poor self assesed health.

16,2 20,4 25,0 23,1 29,1 42,4 26,1 19,2

Characteristics Poor self assesed health Functional restriction

From SEM countries From all other countries

Poor mental health Table 3. Descriptive statistics: health status of the sample according to origin and migratory status (% row)

43,8 40,2

25,6 25,9 From SEM countries

Characteristics N % Cicic engagement

Do you participate regularly in a collective activity such as Participation 2639 36,4 local school association, neighbourhood, or community

association, sport or cultural clubs, religious community union or political party?

No participation 4621 63,7

Social support

Have you ever, during your life and or your childhood, Yes 629 8,7

suffered from loliness? No 6173 85,0

No answer 458 6,3

Sense of control at work

Are you agree with the following statement? Strongly disagree 1474 20,3

"I am in a position to influence contents of my Disagree 1158 16,0

work"? Agree 2439 33,6

Fully agree 1719 23,7

Non applicable 470 6,5

Language spoken during childhood

French language 5404 74,4

French and other language 928 12,8

Other language only 928 12,8

Civic engagement Participation No participation To have suffered from loneliness Yes

No No answer

Sense of control at work Strongly disagree

Disagree Agree Fully agree Non applicable Spoken language during childhood French language

French and other language Other language only

Note: * Within individuals who do not have any civic engagement, 31.7% report a poor self assesed health.

Poor mental health Poor self assesed health Functional restriction

74,9 81,4

Characteristics

Table 5. Descriptive statistics: Health status of the sample according to psycho-social ressources (% row)

22,4 16,7 6,2 48,3 33,8 7,1 12,4 16,3 59,9 74,6 91,7 70,0 78,7 97,1 87,2 5,6 25,7 47,2 31,7 22,6 33,7 18,6 10,9 22,8 7,6 29,0 21,2 20,5 15,0 17,1 21,2 36,6 26,4 9,8 24,3 6,9 15,9

OR OR OR OR OR OR

Male Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref

Female 1,18 0,01 ** 0,98 0,83 0,96 0,54 0,77 0,00 ** 2,14 0,00 *** 1,84 0,00 ***

Age Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref

Age 1,05 0,00 *** 1,05 0,00 *** 1,05 0,00 *** 1,04 0,00 *** 1,00 0,21 1,00 0,33

Post-secondary education Ref Ref Ref

Without certificate 2,45 0,00 ** 2,36 0,00 ** 2,44 0,01 **

Primary 1,59 0,00 *** 1,40 0,02 ** 1,56 0,03 **

1st level of secondary school 1,33 0,01 ** 1,33 0,01 ** 1,57 0,00 **

2nd level of secondary school 1,09 0,45 1,06 0,63 1,24 0,19

Other level of education 1,30 0,54 0,99 0,99 2,44 0,09 *

SES: Executive Ref Ref Ref

Agricultural employee 1,07 0,73 1,13 0,54 1,14 0,71 Self-employed 1,01 0,97 1,06 0,74 1,67 0,10 * Intermediary occupations 1,03 0,83 1,22 0,18 1,59 0,06 * Administrative employee 1,46 0,01 ** 1,46 0,02 ** 1,97 0,01 ** Business employee 1,52 0,01 ** 1,58 0,01 ** 1,74 0,04 ** Skilled worker 1,43 0,02 ** 1,41 0,04 ** 1,91 0,01 ** Unskilled worker 1,56 0,01 ** 1,45 0,04 ** 1,68 0,06 * Non-working 1,05 0,85 0,68 0,16 1,59 0,16

Occupation : Actif Ref Ref Ref

Non-working 2,53 0,00 *** 2,99 0,00 *** 1,88 0,00 ***

Retired 1,08 0,48 1,08 0,50 0,88 0,46

Unemployed 2,18 0,00 *** 2,05 0,00 *** 1,90 0,00 ***

Income: 5th quintile Ref Ref Ref

1th quintile 2,46 0,00 *** 1,52 0,00 ** 1,20 0,30

2nd quintile 1,77 0,00 *** 1,20 0,14 1,22 0,24

3rd quintile 1,30 0,03 ** 1,10 0,45 0,98 0,91

4th quintile 1,29 0,03 ** 0,99 0,94 0,97 0,85

Unknown 1,38 0,01 ** 1,08 0,57 1,25 0,24

Household composition: Couple with child Ref Ref Ref

To be alone 1,37 0,00 ** 1,44 0,00 ** 1,44 0,01 **

Single-parent 1,44 0,00 ** 1,66 0,00 *** 1,98 0,00 ***

Childless couple 1,23 0,02 ** 1,11 0,30 0,97 0,82

Other household composition 1,34 0,10 1,49 0,04 ** 1,39 0,19

Migratory status: French Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref

First migrant generation

From SEM countries 3,19 0,00 *** 1,97 0,00 *** 1,81 0,00 ** 1,15 0,50 2,60 0,00 *** 1,86 0,01 ** From all other countries 1,83 0,00 *** 1,44 0,01 ** 1,34 0,03 ** 1,05 0,76 1,57 0,01 ** 1,25 0,22 Second migrant generation

From SEM countries 1,66 0,02 ** 1,30 0,23 1,50 0,11 1,27 0,35 1,25 0,44 1,01 0,98 From all other countries 1,25 0,04 ** 1,30 0,02 ** 1,12 0,34 1,15 0,24 1,05 0,78 1,06 0,75

No answer 1,57 0,31 1,33 0,53 1,05 0,92 0,93 0,87 1,84 0,28 1,51 0,49

N 6555 6555 6431 6431 6118 6118

Pseudo R² (Mc Faden) 0,12 0,19 0,09 0,14 0,02 0,07

Log L -3380,9 -3132,0 -2909,2 -2757,8 -1799,3 -1716,9

Legend :* p<0,1; ** p<0,05; *** p<0,01

Poor self assesed health

p-value p-value

p-value

p-value p-value p-value

Table 6. Influence of migratory status and origin on the likelihood to report a poor health status before and after control for socio-economic conditions

Poor mental health

Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2 Model 1

Poor functional health

Model 2 Characteristics

OR OR OR

Male Ref Ref Ref

Female 0,97 0,72 0,76 0,00 ** 1,82 0,00 ***

Age Ref Ref Ref

Age 1,05 0,00 *** 1,04 0,00 *** 1,00 0,40

Post-secondary education Ref Ref Ref

Without certificate 2,07 0,01 ** 2,16 0,00 ** 1,79 0,10 *

Primary 1,44 0,00 ** 1,31 0,05 * 1,31 0,18

1st level of secondary school 1,24 0,04 ** 1,27 0,04 ** 1,38 0,03 **

2nd level of secondary school 1,03 0,80 1,01 0,92 1,11 0,53

Other level of education 1,15 0,75 0,91 0,85 2,22 0,14

SES: Executive Ref Ref Ref

Agricultural employee 1,12 0,55 1,19 0,40 1,31 0,45 Self-employed 1,05 0,80 1,09 0,65 1,83 0,05 ** Intermediary occupations 1,01 0,92 1,22 0,18 1,60 0,05 * Administrative employee 1,35 0,05 * 1,40 0,04 ** 1,87 0,01 ** Business employee 1,37 0,06 * 1,49 0,02 ** 1,60 0,08 * Skilled worker 1,32 0,08 * 1,34 0,08 * 1,83 0,03 ** Unskilled worker 1,37 0,06 * 1,35 0,10 1,50 0,14 Non-working 1,00 0,99 0,70 0,19 1,53 0,20

Occupation : Actif Ref Ref Ref

Non-working 2,40 0,00 *** 2,90 0,00 *** 1,73 0,00 **

Retired 1,09 0,45 1,09 0,48 0,90 0,56

Unemployed 2,05 0,00 *** 1,95 0,00 *** 1,74 0,00 ***

Income: 5th quintile Ref Ref Ref

1th quintile 2,27 0,00 *** 1,43 0,01 ** 1,04 0,83

2nd quintile 1,68 0,00 *** 1,15 0,27 1,11 0,57

3rd quintile 1,26 0,07 * 1,06 0,63 0,91 0,59

4th quintile 1,25 0,06 * 0,96 0,74 0,90 0,57

Unknown 1,32 0,03 ** 1,04 0,77 1,18 0,40

Household composition: Couple with child Ref Ref Ref

To be alone 1,31 0,01 ** 1,37 0,00 ** 1,31 0,06 *

Single-parent 1,37 0,01 ** 1,58 0,00 ** 1,83 0,00 ***

Childless couple 1,22 0,03 ** 1,10 0,38 0,94 0,65

Other household composition 1,24 0,25 1,39 0,09 * 1,22 0,44

Migratory status: French Ref Ref Ref

First migrant generation

From SEM countries 1 1,64 0,01 ** 1,11 0,64 1,38 0,22 From all other countries 1,20 0,26 1,04 0,83 0,86 0,54 Second migrant generation

From SEM countries 1,16 0,50 1,21 0,47 0,86 0,63

From all other countries 1,25 0,06 * 1,13 0,32 0,98 0,92

No answer 1,14 0,77 0,83 0,69 1,20 0,77

Langue française Ref Ref Ref

Langue française et autre 1,19 0,08 * 1,11 0,32 1,08 0,63

Langue autre 1,12 0,36 0,91 0,45 1,22 0,29

Collective Praticipation Ref Ref Ref

No collective participation 1,35 0,00 *** 1,29 0,00 ** 1,54 0,00 ***

To have autonomy at work Ref Ref Ref

To have no autonomy at work 1,29 0,00 *** 1,15 0,07 * 1,25 0,04 **

Not applicable 1,20 0,20 1,04 0,78 1,30 0,15

To not have suffered from loneliness Ref Ref Ref

To have suffered from loneliness 1,98 0,00 *** 1,74 0,00 *** 2,71 0,00 ***

No answer 0,99 0,96 0,92 0,61 0,84 0,40 N 6555 6431 6118 Pseudo R² (Mc Faden) 0,20 0,14 0,09 Log L -3091,9 -2735,9 -1675,0 Legend :* p<0,1; ** p<0,05; *** p<0,01 p-value

Poor mental health

Model 3

Table 7. Influence of migratory status, origin and social integration on the likelihood to report a poor health status after control for socio-economic conditions

Characteristics Model 3 Model 3

p-value p-value

References

Attias-Donfut C. & Tessier P.(2005), Santé et vieillissement des immigrés, Retraite et Société n°46. Borsch-Shupan & Al (2005), Health Ageing and Retirement in Europe, First results from the survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, puplished by MEA.

Dunn JR. & Dyck I. (2000), Social Determinants of Health in Canada’s immigrant population : results from the National Population Healtlh Survey ; Social Science & Medicine N°51.

Folland S. (2007), Does “community social capital” contribute to population health? Social Science & Medecine N°64.

Gee EM., Kobayaski KM. & Prus S (Mai 2007), Ethnic Inequality in Canada : Economic and Health dimensions ; SEDAP- Research paper n° 182.

Goldberg M, Melchior M, Leclerc A, Lert F. (2002) Les déterminants sociaux de la santé : apports récents de l’épidémiologie sociale et des sciences sociales de la santé. Sciences Sociales et Santé, 20:75-128

Islam M.K. (2007), Essays on Social Capital, Health and Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health, Lund University Eds.

Jusot F., Grignon M. & Dourgnon P. (2008), Acess to psycho-social resources and social health: Exploratory findings from a survey of the French population, Health Economics, Policy and Law. Jusot F., Dougnon P., Sermet C. & Silva J.(2008), Etat de santé des populations immigrées en France, IRDES – Document de Travail N°14.

Kennedy S. et al (2006), The Healthy Immigrant Effect and Immigrant Selection: Evidence from Four Countries, SEDAP, Research Paper n°164.

Khlat M. & Courbage Y. (1995), La mortalité et les causes de décès des Marocains en France 1979 à 1991, Population N°2.

Leclere FB, Jensen L. & Biddlecom AE. (1994), Health Care Utilisation, Family context and adaptation among Immigrants to the United States; Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol 35, N°4.

Lert F., Melchior M. & Ville I. (2007), Fonctional limitations and overweight among migrants in the histoire de vie study, Revue d’Epidémiologie et de Santé Publique 55.

Levitt M., Lane J. & Levitt J. (2003), Immigration, Stress, social Support, and Adjustement ; Departement of Psychologie, Florida International University.

Marmot M. & Wilkinson R.G. (2006), Social Determinant of health, Second Edition, Oxford University Press.

McDonald J.T. & Kennedy S. (2004), Insights into the “healthy immigrant”: health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada; Social Science & Medicine N°59

McDonald J.T. & Neily J. (Juin 2007), Immigration, Ethnicity and Cancer in US Women, SEDAP-Research paper n° 206.

Newbold K.B. & Danforth J. (2003), Health Status and Canada’s immigrant population, Social

Science Medecine N°57.

Putnam. R.D. (1995), Bowling Alone – America’s declining social capital, Journal of Democracy 6:1 Putnam. R.D. (2000), Bowling Alone - The Collapse and revival of American community, Chapitres 1 et 20 , Simon & Schuster Eds.

Rubalcava L.N. & al (2008), The healthy Migrant effect: New findings from the Mexican Family Life Survey, American journal of Public Health, Vol 98, N°1.

Zambrana R.E. & Al (1994), The relationship between psychosocial status of immigrant Latino mothers and use of emergency pediatric services ; National Association of Social Workers.