Students' Perceptions of their Intercultural

Communicative Competence Following Intercultural

Encounters with Language Assistants: A Multiple Case

Study

Mémoire

Christina Driedger

Maîtrise en linguistique - avec mémoire

Maître ès arts (M.A.)

Students’ Perceptions of their Intercultural

Communicative Competence Following Intercultural

Encounters with Language Assistants: A Multiple Case

Study

Mémoire

Christina Driedger

Sous la direction de :

Monica Waterhouse, directrice de recherche

Suzie Beaulieu, codirectrice de recherche

Résumé

Le programme des langues officielles, Odyssée, existe depuis plus de 40 ans, mais aucune recherche empirique connue ne s'est penchée sur son impact sur les apprenants de L2—le plus grand nombre d'acteurs impliqués. Pour combler cette lacune, cette étude s'est penchée sur la perception qu'ont les apprenants de L2 en anglais de leur compétence en communication interculturelle à la suite de rencontres interculturelles avec des assistants en langues officielles. Une approche d'études de cas multiples a été utilisée pour recueillir des données quantitatives et qualitatives auprès d'un assistant en langues (n=1) et des apprenants d’anglais L2 (N=124) dans deux écoles secondaires de la province de Québec, situées dans une communauté semi-urbaine et rurale. L'objectif principal de cette étude était d'examiner comment les rencontres interculturelles avec des assistants en langues pourraient façonner les dimensions cognitives et affectives de la compétence communicative interculturelle des apprenants. Elle a également examiné comment les facteurs sociodémographiques pouvaient influencer les résultats. Les principaux résultats révèlent que les participants des deux écoles ont estimé que l'apprentissage avec l'assistant de langue a façonné leurs attitudes et connaissances interculturelles, mais pas dans la même mesure. Cette étude souligne l'influence potentielle des facteurs sociodémographiques sur les attitudes et les connaissances interculturelles des participants ainsi que le rôle que l'assistant de langue a pu jouer dans la formation des connaissances interculturelles des participants. Enfin, cette étude suggère que l'intersection de la compétence interculturelle et de la recherche sur les assistants de langues est un domaine d'enquête important et que les programmes de langues officielles au Canada bénéficieraient de recherches supplémentaires dans cette direction.

Abstract

The official languages program, Odyssey, has existed for over 40 years, yet no known empirical research has investigated its impact on L2 learners—the largest number of stakeholders involved. To address this gap, this study looked at English L2 learners’ perceptions of their intercultural communicative competence following intercultural encounters with official language assistants. A multiple case study approach was used to collect quantitative and qualitative data from a language assistant (n=1) and English L2 learners (N=124) at two secondary schools in the province of Quebec, located in a semi-urban and rural community. The primary objective of this study was to examine how intercultural encounters with language assistants might shape the knowledge and affective dimensions of learners’ intercultural communicative competence. It also considered how sociodemographic factors might influence the results. Main results reveal that participants in both schools felt that learning with the language assistant shaped their intercultural attitudes and knowledge, but not to the same degree. This study highlights the potential influence of sociodemographic factors on participants’ intercultural attitudes and knowledge as well as the role the language assistant may have played in shaping participants’ intercultural knowledge. Finally, this study suggests that the intersection of intercultural competence and language assistant research is an important area of inquiry and that official languages programs in Canada would benefit from further research in this direction.

Table of Contents

Résumé ... ii

Abstract ... iii

Table of Contents ... iv

List of Figures ... viii

List of Tables ... ix

List of Abbreviations ... x

Acknowledgements ... xi

Introduction... 1

Chapter 1 Statement of the Problem ... 4

1.1 Research on Language Assistant Programs ... 5

1.2 Research on Intercultural (Communicative) Competence ... 5

1.3 Objectives... 7

Chapter 2 Conceptual Framework ... 8

2.1 FL and L2 Learning ... 8

2.2 Core L2 Learning in the Current Educational System ... 8

2.3 Language Assistant ... 8

2.4 Intercultural Encounters ... 9

2.5 Aspects of Culture... 9

2.6 Intercultural Communicative Competence ... 9

2.7 Byram’s (1997) Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence ... 10

2.7.1 Overview ... 10

2.7.2 Origins ... 11

2.7.3 The Savoirs: Components of Byram’s (1997) Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence 11 2.8 Rationale for Focussing on Attitudes and Knowledge ... 13

Chapter 3 Review of the Literature ... 15

3.1 Language Assistant Programs ... 15

3.1.1 Language Assistants in FL Learning ... 15

3.1.2 Language Assistants in CLIL ... 16

3.2 Intercultural (Communicative) Competence in FL Learning ... 18

3.2.1 Intercultural Communicative Competence in FL Learners in a Classroom Setting... 18

3.4 Summary ... 22

3.5 Research Questions... 22

Chapter 4 Methodology ... 24

4.1 Research Design ... 24

4.1.1 Case Study Research ... 24

4.1.2 Advantages and Limitations of Case Study Research ... 24

4.1.3 Case Selection Logic ... 24

4.1.4 Rationale for Case Study Research ... 25

4.2 Case Profiles ... 25

4.2.1 Setting ... 25

4.2.2 Participants ... 25

4.3 Instruments ... 35

4.3.1 Questionnaire for L2 Learners ... 35

4.3.2 Focus Group Interview Schedule ... 37

4.3.3 Questionnaire for Language Assistants... 37

4.4 Procedure ... 38

4.4.1 Piloting the Instruments ... 38

4.4.2 Data Collection ... 41

4.5 Data Management ... 42

4.5.1 Case Study Database ... 42

4.5.2 Data Processing ... 42

4.6 Data Analysis ... 43

4.6.1 Analyzing Quantitative Data ... 43

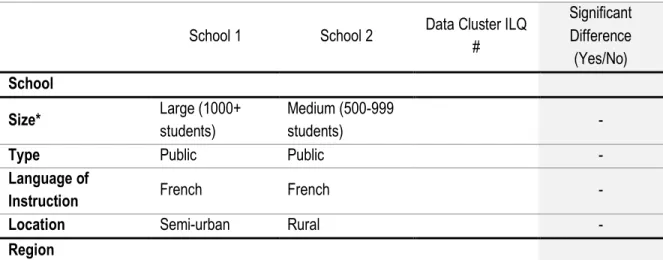

4.6.2 Analyzing Qualitative Data ... 47

4.7 Ensuring a Trustworthy Study ... 50

4.7.1 Construct Validity ... 50

4.7.2 Internal Validity ... 51

4.7.3 External Validity in Case Study Research ... 51

4.7.4 Reliability ... 51

4.8 Ethical Considerations ... 51

4.9 Summary ... 51

Chapter 5 Results ... 53

5.2 Research Question 1a ... 53

5.2.1 Dimension 1: Willingness to seek out or take up opportunities to engage with otherness in a relationship of equality ... 53

5.2.2 Dimension 2: Interest in discovering other perspectives on interpretation of familiar and unfamiliar phenomena both in one’s own and in other cultures and cultural practices ... 55

5.2.3 Dimension 3: Readiness to experience the different stages of adaptation to and interaction with another culture during a period of residence ... 56

5.2.4 Dimension 4: Readiness to engage with the conventions and rites of verbal and non-verbal communication and interaction ... 57

5.2.5 Dimension 5: Willingness to question the values and beliefs central to one’s own culture practices and products ... 58

5.2.6 Summary of Attitudes ... 62

5.3 Research Question 1b ... 64

5.3.1 Dimension 1: Knowledge about social groups and their products and practices in one’s own and in one’s interlocutor’s country, and knowledge of the general processes of societal and individual interaction ... 64

5.3.2 Dimension 2: Knowledge about the processes of social interaction in one's interlocutor's country . 66 5.3.3 Dimension 3: Knowledge about how the TL community is perceived by one’s own and vice versa, (inter)cultural knowledge ... 67

5.3.4 Summary of Knowledge ... 70

5.4 Themes from the Qualitative Data ... 74

5.4.1 Participants perceived their culture and the TL culture as very much alike (variations: similar; same; except language, same country; few differences)... 74

5.4.2 Participants did not learn a lot about the TL culture (variations: TL culture; Language assistant’s culture; Language assistant) ... 75

5.4.3 Learning with the language assistant shed light on differences in surface and deep culture aspects of participants’ culture and the TL culture ... 75

5.4.4 Learning with the language assistant shed light on similarities in surface and deep culture aspects of participants’ culture and the TL culture ... 76

5.4.5 Reflecting on intercultural encounters ... 76

5.5 Summary ... 77

Chapter 6 Discussion ... 79

6.1 Introduction ... 79

6.2 Students’ perceptions of their intercultural attitudes after learning with the language assistant ... 79

6.2.1 Research Question 1a ... 79

6.3.1 Research Question 1b ... 84

6.4 Implications ... 88

6.4.1 Defining culture and equipping language assistants to talk about it ... 88

6.4.2 Providing additional resources to regions ... 89

6.4.3 Reimagining OLP curricula to create more space for (inter)cultural reflection ... 89

6.5 Summary ... 90

Conclusion ... 91

Limitations ... 92

Avenues for Future Research... 93

Bibliography... 94

Appendix A Questionnaire for L2 Learners... 102

Appendix B Breakdown - Questionnaire for L2 Learners ... 107

Appendix C Focus Group Interview Schedule for L2 Learners ... 112

Appendix D Questionnaire for Language Assistants ... 114

Appendix E Pilot Feedback Form - Questionnaire for L2 Learners ... 116

Appendix F Pilot Feedback Form - Focus Group Interview Schedule for L2 Learners ... 117

Appendix G Pilot Feedback Form - Questionnaire for Language Assistants ... 118

Appendix H Coding Manual for Qualitative Data... 119

Appendix I Data Visualization Created in NVivo ... 122

List of Figures

Figure 1: Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence (Image source: Byram, M. (1997) Teaching and

Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters) ... 14

Figure 2: Descriptive data for language spoken at home ... 28

Figure 3: Descriptive data for English spoken outside of school ... 29

Figure 4: Descriptive data for number of times per week participants speak English outside of school ... 29

Figure 5: Descriptive data for English activities outside of school ... 31

Figure 6: Descriptive data for number of times per week participants participate in activities in English outside of school ... 31

Figure 7: Three phases of data collection ... 41

Figure 8: Coding process for qualitative data (adapted from Saldaña & Miles, 2013) ... 48

Figure 9: Descriptive data for Attitudes, Willingness to seek out or take up opportunities to engage with otherness in a relationship of equality ... 54

Figure 10: Descriptive data for Attitudes, Interest in discovering other perspectives on interpretation of familiar and unfamiliar phenomena both in one’s own and in other cultures and cultural practices ... 55

Figure 11: Descriptive data for Attitudes, Readiness to experience the different stages of adaptation to and interaction with another culture during a period of residence... 56

Figure 12: Descriptive data for Attitudes, Readiness to engage with the conventions and rites of verbal and non-verbal communication and interaction ... 58

Figure 13: Descriptive data for Attitudes, Willingness to question the values and beliefs central to one’s own culture practices and products: Aspects of the TL culture participants would like to find in their own culture ... 59

Figure 14: Cross-case comparison of qualitative data for aspects of TL culture participants would like to see in their own culture ... 60

Figure 15: Descriptive data for Attitudes, Willingness to question the values and beliefs central to one’s own culture practices and products: Aspects of participants’ own culture that would benefit the TL culture ... 61

Figure 16: Cross-case comparison of qualitative data for aspects of participants’ culture that could benefit the TL culture ... 62

Figure 17: Descriptive data for Knowledge about social groups and their products and practices in one’s own and in one’s interlocutor’s country, and knowledge of the general processes of societal and individual interaction ... 65

Figure 18: Descriptive data for Knowledge about the processes of social interaction in one's interlocutor's country ... 67

Figure 19: Descriptive data for Knowledge about differences between participants’ own and TL cultures ... 68

Figure 20: Cross-case comparison of qualitative data for differences remarked between participants’ own and TL cultures after having learned with the language assistant ... 69

Figure 21: Descriptive data for Knowledge about similarities between participants’ own and TL cultures ... 69

Figure 22: Cross-case comparison of qualitative data for similarities remarked between participants’ own and TL cultures after having learned with the language assistant ... 70

List of Tables

Table 1: People participants speak English with ... 30

Table 2: English activities participants participate in outside of school ... 32

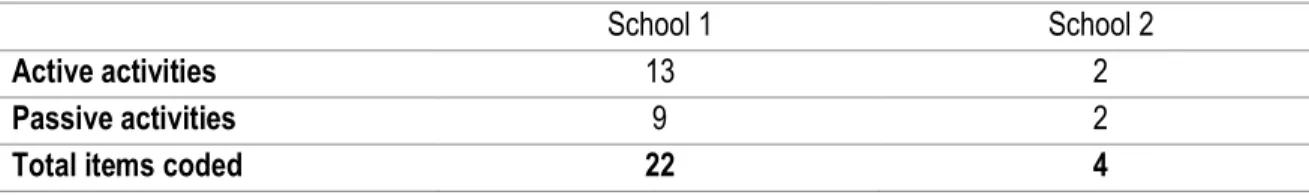

Table 3: Case profile summary ... 33

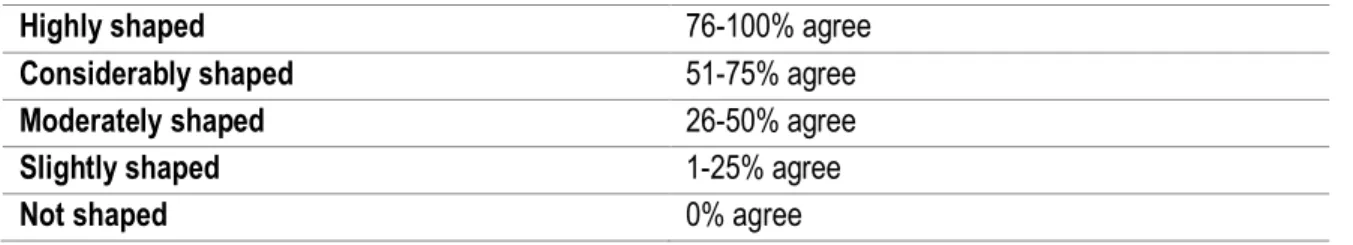

Table 4: Data clusters for attitudes ... 44

Table 5: Data clusters for knowledge ... 46

Table 6: Scale to interpret descriptive statistics from questionnaire for L2 learners ... 46

Table 7: Case study tactics for four design tests (adapted from Yin, 2018, p. 43) ... 50

Table 8: Summary of results for research question 1a ... 63

Table 9: Summary of results for research question 1b ... 71

List of Abbreviations

ESL: English as a second language FL: Foreign language

FSL: French as a second language

ICC: Intercultural communicative competence ILQ: Intercultural Learning Questionnaire L1: First language

L2: Second language LA: Language assistant OLA: Official Languages Act OLP: Official languages program TL: Target language

Acknowledgements

Ce projet a été réalisé grâce à l’aide et du soutien généreux de plusieurs personnes.

First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest appreciation and thanks to my research supervisors and mentors, Professor Monica Waterhouse and Professor Suzie Beaulieu. Without your support, expertise, invaluable insight and thoughtful advice, this project would not have been possible. Thank you for your guidance at every step of the project, for developing my critical spirit and for introducing me to the exciting world of research.

Je suis également très reconnaissante aux professeures du comité de lecture qui ont si gracieusement accepté d'évaluer ce manuscrit, professeure Monica Waterhouse, professeure Suzie Beaulieu et professeure Susan Parks. Merci d'avoir pris le temps de lire attentivement et de commenter ce mémoire de maîtrise. Vos recommandations judicieuses ont grandement contribué à améliorer sa qualité générale.

I would like to acknowledge the Odyssey program at the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada, and the

Ministère de l'Éducation et de l'Enseignement supérieur du Québec for helping me with my recruitment efforts.

To the teachers who so kindly welcomed me into their classrooms to collect data, the principals who accepted my invitations, and all of the students who participated: a huge thank you for your invaluable contribution. I would also like to thank those individuals who piloted my instruments for their constructive feedback and the teacher who took the time to offer suggestions during the pilot testing process.

Merci à mes amis qui ont été une source de soutien et d'inspiration tout au long du chemin.

To my family – thank you for your continuous help, love and support and for accompanying me, from near and far, on this journey.

Enfin, je tiens à remercier chaleureusement, Josué. Merci de m’avoir soutenu dans mon voyage pour apprendre une nouvelle langue, découvrir de nouvelles cultures, et réaliser ce projet de mémoire. Ton soutien, amour, et tes encouragements me sont très chers.

Introduction

This study took a first look at second language learners’ perceptions of their intercultural competence development within the context of an official languages program in Canada. Situated against the backdrop of the Odyssey program, this research investigated English as a second language learners’ perceptions of their intercultural communicative competence (Byram, 1997), following intercultural encounters (Holmes, Bavieri, & Ganassin, 2015) with language assistants.

Intercultural (communicative) competence has been the subject of studies across many sectors in recent years (Deardorff, 2015). As our ability to connect with individuals around the globe rapidly increases, there is reason to believe that this trend will continue to grow. In second and foreign language classroom-based learning, a body of intercultural research suggests that exposure to intercultural knowledge from learning materials (Ahnagari & Zamanian, 2014) and opportunities to interact with target language speakers (Houghton, 2010) contribute to learners’ intercultural competence. Studies also show that language assistants create opportunities for foreign language learners to interact with target language speakers and learn about target languages and cultures (Hibler, 2010). Therefore, Odyssey, which places language assistants in classrooms across Canada with the goal of helping learners practice their target language and enhance their knowledge of its cultures (The role of the language assistant, n.d.), offers an ideal context to study intercultural competence development. However, to date, we know of no empirical research that has attempted to do so.

To fill this gap, we conducted a multiple case study (Yin, 2018) that collected quantitative and qualitative data from English as a second language learners (N=124) from two secondary schools in the province of Quebec. The secondary schools were situated in distinct, and in some ways, contrasting locations, with one school (school 1) located in a semi-urban community and the other (school 2) in a rural community. The research sites were strategically targeted to provide an opportunity to compare and contrast participants’ responses and fulfill not only the first objective of our study, to examine how intercultural encounters with language assistants might shape the knowledge and affective dimensions of learners’ intercultural communicative competence, but also consider how sociodemographic factors may impact the results.

Data were collected in three phases using three instruments: a questionnaire for learners, a focus group interview for learners, and a questionnaire for the language assistant. Data analysis involved a statistical analysis of the quantitative data and thematic analyses of the qualitative data. As prescribed by our multiple case study design, data for each school were analyzed separately and then compared. Information from the language assistant questionnaire was used to help interpret and describe data collected from the other two sources.

Overall, results revealed that participants in both schools perceived that learning with the language assistant shaped their intercultural attitudes and knowledge. However, a difference was noticed concerning the way the dimensions appeared shaped in each school. On the one hand, results showed that in school 1, participants felt that their attitudes were shaped to a somewhat higher degree than participants in school 2. On the other hand, results indicated that in school 2, participants felt that their knowledge was shaped to a slightly higher degree than participants in school 1. To interpret these results, we drew on multiple sources of information, including sociodemographic data, themes that emerged from the qualitative data, and information from the language assistant questionnaire. While our findings cannot be generalized to other contexts, it appears that for attitudes, the differences observed between schools may primarily be explained by sociodemographic characteristics linked to location that afforded participants in school 1 more opportunities to interact with target language speakers. In terms of knowledge, it appeared that the same sociodemographic characteristics were at play. Interestingly, for this dimension, it also appeared that the type of activities language assistants led may have had an impact on the type of intercultural knowledge participants acquired.

The next six chapters will walk through how we came to these conclusions and discuss the potential implications of this study on the Canadian language assistant program.

In Chapter 1, we state the problem, introducing the language assistant program and providing an overview of previous research that has looked at language assistant programs and intercultural (communicative) competence. This chapter ends with a statement of our objectives.

In Chapter 2, we define key terms and outline Byram’s (1997) model of Intercultural Communicative Competence which served as the conceptual framework for the present study.

In Chapter 3, we review previous literature, presenting research on language assistant programs in various contexts as well as research focused on intercultural (communicative) competence in a language learning setting and the broader context of Canadian society. The research question and sub-questions are presented at the end of this chapter.

In Chapter 4, we describe our research methodology. This chapter includes an overview of case study research, the profiles of the two cases and their participants, and a description of the data collection instruments. This chapter also details how we collected and analyzed the data and the measures we took to ensure a trustworthy study.

In Chapter 5, we present the results, beginning with attitudes and moving onto knowledge. The final paragraphs of the chapter present five themes that emerged from the qualitative data and cut across schools. This data helped to provide context for our interpretations and triangulate the findings.

In Chapter 6, we discuss the results, drawing on multiple sources of information and examining plausible rival explanations for the trends and tendencies observed. This chapter ends with three main implications for the language assistant program which can be interpreted within the limits of the research.

Finally, we conclude this master’s thesis with a summary of the results followed by a discussion of the limitations of this study and avenues for future research.

Chapter 1 Statement of the Problem

In 2019, Canada celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Official Languages Act (OLA). Implemented in 19691,

the OLA ensures the equal status of French and English in federal institutions, protects the vitality of official language minority communities, and supports the use of both official languages in Canada. One important outcome of the OLA was the creation of Canada’s official languages programs (OLP) to “promote Canada’s two official languages and the cultures they convey” (Council of Ministers of Education Canada [CMEC], 2012).

The Odyssey program is one of Canada’s oldest OLPs. Funded by the Department of Canadian Heritage and coordinated on a national level by the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC), Odyssey provides opportunities for eligible Canadian citizens or permanent residents to work as English or French language assistants (LA) in primary, secondary or post-secondary institutions across the country. The program has grown considerably since its inception in 1973 and Canadian Heritage reports that approximately 300 LAs participate each year (Canadian Heritage, 2017).

Language assistants are Odyssey’s primary stakeholders and the program is marketed as an opportunity for them to participate in a linguistic and cultural exchange by diving “deep into another language and culture while sharing [their] own; travel and explore Canada; earn an income and get bilingual professional experience” (What is Odyssey?, n.d.). However, the program has another stakeholder population that is often overlooked—the second language (L2) students directly impacted by the presence of LAs in their schools. A closer look at program documentation reveals important pedagogical aims of Odyssey that target these secondary stakeholders:

In the ESL and FSL streams, language assistants are assigned to an educational institution to help second-language teachers or instructors encourage students to interact in the language they are studying and to raise their awareness of the culture associated with that language. (CMEC, n.d.) [emphasis added]

Recently, the Canadian government recognized the vital role that Odyssey plays in promoting a bilingual Canada by committing to modernize the program over the next five years (Government of Canada, 2018). However, despite the program’s history, the number of youths implicated, and plans for development, a review of the research literature reveals that very little is known about the impact of the program on both its primary and

secondary stakeholders. In fact, no known empirical research exists examining the impact of Odyssey on L2 learners who are believed to benefit from an enriched school environment by learning with LAs (CMEC, 2016).

1.1 Research on Language Assistant Programs

In addition to Canada, language assistant programs exist in several countries around the world (e.g., Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, Australia, the UK, Spain, France, the U.S.). Yet, despite their mainstream popularity, literature on these programs is relatively thin. Existing research has taken place outside of the Canadian context and has focused on the use of LAs to enhance foreign language (FL) learning (Lynch & Anderson, 2001; Macaro, Nakatani, Hayashi, & Khabbazbashi, 2014; Martin & Mitchell, 1993) and Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) (Dafouz & Hibler, 2013; Hibler, 2010; Lorenzo, Casal, & Moore, 2010; Méndez García & Pavón Vázquez, 2012) among primary and post-secondary learners. These studies show that employing LAs to work in FL and CLIL contexts allows learners to scaffold their knowledge of course content (Dafouz & Hibler, 2013), discover different registers of target language (TL) speech (Dafouz & Hibler, 2013) and engage in opportunities for input, output and interaction in the TL (Hibler, 2010; Lynch & Anderson, 2001; Martin & Mitchell, 1993). Research has also touched on the role of LAs as cultural informants (Hibler, 2010), offering insight into how they make connections and create opportunities for students to compare their L1s and cultures with the TLs and cultures. However, despite the dual mandate of many language assistant programs to promote both language and cultural learning, intercultural exchanges between LAs and their learners have not been explored in depth. As scholar Wallace-Dargent (2013) points out, there is more to be learned about learners’ interculturality by studying the interactions between LAs and their students (p. 278).

1.2 Research on Intercultural (Communicative) Competence

Wallace-Dargent’s assertion is timely. As the forces of globalization continue to shape all aspects of our lives – from how we do business to how we learn – intercultural competence, broadly defined as the ability to communicate effectively with individuals of different cultural backgrounds and in diverse contexts (Peng & Wu, 2016, p. 17-18), is more important than ever before. In 2013 UNESCO declared intercultural competences as critical to maintaining social harmony, and today intercultural competence is integral to many education and training programs across sectors, from the military to healthcare to education (Deardorff, 2015).

In the field of education, scholars acknowledge intercultural competence as an essential component of students’ success in an increasingly interconnected world (Moeller & Nugent, 2014). Second and foreign language education has also seen a greater focus on teaching and assessing intercultural competence in recent years (Hismanoglu, 2011). This is not surprising considering that many L2 and FL learning scholars support the notion of language and culture as inherently linked (e.g., Byram, 1989; Byram & Morgan, 1994; Kramsch, 1993; Liddicoat, Papademetre, Scarino & Kohler, 2003; Risager, 2005) and have underscored the connection between

language, culture and intercultural communicative competence (Lussier, 2011). For example, Byram and Morgan (1994) argue that due to the inseparable nature of language and culture, teaching language involves teaching culture and vice versa (p. vii). Furthermore, Lussier (2011) proposes that L2 and FL language learning, which invites learners to enter into contact with different languages, cultures and Otherness, offers the optimal environment for the development of intercultural communicative competence. According to Lussier (2011), “learning a foreign language is essentially learning to interact as an ‘intercultural competent speaker’” (p. 36). Following the lead of these authors, we will subscribe to the notion of language and culture as inseparable; as such, we see encounters between L2 learners and LAs within the context of L2 learning as presenting occasions for both language and culture learning.

Research on intercultural competence in L2 and FL learners has taken place in many contexts, from study abroad (e.g., Durán Martínez, Gutiérrez, Beltrán Llavador, & Martínez Abad, 2016; Hismanoglu, 2011; Root & Ngampornchai, 2012; Salisbury, An, & Pascarella, 2013) to classroom-based language learning in both immersion (Moloney, 2007; Moloney & Harbon, 2010) and L2 and FL programs (Ahnagari & Zamanian, 2014; Amireault, 2002; Houghton, 2010, 2014; Peiser, 2012). Overall, these studies show that L2 and FL learners demonstrate manifestations of intercultural (communicative) competence.

In the arena of L2 and FL classroom-based learning, research has mainly been conducted among primary and post-secondary learners and has focused on the knowledge and affective dimensions of intercultural communicative competence (ICC). Studies suggest that a combination of factors both inside and outside of the classroom contribute to learners’ intercultural knowledge and attitudes and include sociodemographic and socio-affective factors, curriculum, teachers, exposure to intercultural knowledge, and opportunities to interact with TL speakers via classroom activities or travel (e.g., Ahnagari and Zamanian, 2014; Amireault, 2002; Houghton, 2010, 2014; Peiser, 2012, 2015). However, although scholars state that favoring contacts between different cultural groups can help to generate intercultural understanding (Lussier, 2011), they also note that a lack of intercultural competence may lead to cultural misunderstandings, for example, in contexts where socio-historical conflict may exist (Peiser, 2015).

In sum, studies show that LAs have be used to support FL learning and cultural awareness. They do this by interacting with learners in their TL, modelling the TL, and exposing learners to TL cultures, in some cases, by introducing authentic learning materials into the classroom. Research also reveals that L2 and FL learners show manifestations of ICC. Many factors are at play and among these, exposure to intercultural learning materials and opportunities to engage with TL speakers have been frequently cited as shaping their intercultural knowledge and attitudes. In both research streams, a paucity of empirical research involving secondary school language learners is observed.

In 2017-2018, 80 Odyssey LAs worked in primary, secondary and post-secondary classrooms in the province of Quebec. More than half of these assistants were attributed placements at the secondary level where they worked to support English L2 learning (M. Camirand, personal communication, January 29, 2018). Yet, as stated above, we are unaware of the potential impact that learning with LAs might have on these learners and, more specifically, on their intercultural development. This study aims to fill this gap.

1.3 Objectives

This study has two main objectives. First, it will inquire into how intercultural encounters with LAs might shape the knowledge and affective dimensions2 of learners’ ICC. Second, it will consider how sociodemographic factors

(such as age, gender, L1, languages spoken at home, dominant language, number of years learning with language assistants, frequency of intercultural encounters with language assistant, contact with TL outside of school, and community language demographics) might influence these results. In addition to contributing to a growing body of interculturally-focused second language learning literature, it is hoped that this study will help to better define how linguistic and cultural exchanges shape contemporary Canadian society.

2 See section 2.8 for rationale as to why we chose to focus on the attitude and knowledge components of Byram’s (1997)

Chapter 2 Conceptual Framework

This study aimed to explore how intercultural encounters between English L2 learners and LAs might shape learners’ ICC. The present chapter will define the following concepts central to our study: FL and L2 learning, L2 learning in the current educational system, language assistant, intercultural encounters, aspects of culture, and intercultural communicative competence as defined by Byram (1997).

2.1 FL and L2 Learning

The difference between a FL and an L2 is contextual. In Canada, where French an English are official languages, learning either of these as an additional language is considered L2 learning because it is expected that learners will have opportunities to engage in the TL outside of the classroom.

This study draws on research from around the world, much of which refers to FL learning. When reporting on it, we will use the term originally employed by the author to designate the context in which the language learning is taking place (e.g., FL or L2). When describing research in the Canadian context that involves either French or English as an additional language learning, including our own, we will refer to L2 learning.

2.2 Core L2 Learning in the Current Educational System

This study takes place in the context of core ESL learning in the current Quebec educational system. In Canada, core L2 learning refers to the minimum obligatory second language instruction offered through the Canadian public-school system. In the province of Quebec, core ESL begins in the first year of primary school (ages 6-7) and continues until the last year of secondary school (ages 16-17). On average, students at the secondary level receive 100 hours of second language instruction per year (approximately 2.5 hours/week) (Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport, 2012). According to the core ESL program, graduates "will be able to communicate in English to meet their needs and pursue their interests in a rapidly evolving global society" (Ministère de l’éducation et enseignement supérieur, n.d., p. 1).

2.3 Language Assistant

A language assistant is an individual who works in conjunction with teachers to support L2 or FL learning. The LAs in this study are participants of the OLP, Odyssey. Generally, their mandate consists of providing students with opportunities to use the TL in a classroom setting and encouraging them to learn more about the TL and its associated cultures (The role of the language assistant, n.d.). According to the CMEC, assistants will achieve these objectives by leading oral communication activities, games, and by drawing on authentic materials (e.g., music, art, stories, local expressions). LAs are recruited based on their first language skills (Eligibility, n.d.) and

take part in pedagogical training sessions that address TL teaching (Training sessions, n.d.). They also have access to a range of print and electronic activities provided by the program and are encouraged to develop their own (CMEC, n.d., p. 4-5). Depending on their level, LAs may team-teach, lead sessions with small groups of learners, or a combination of both (CMEC, n.d., p. 3).

2.4 Intercultural Encounters

Intercultural encounters are defined as interactions between LAs and L2 learners that take place in the context of L2 learning and involve the exchange of the TL and cultures. This definition is adapted from Holmes, Bavieri, and Ganassin's (2015) understanding of intercultural encounters as “the verbal or non-verbal interactions between two or more people who may perceive each other as having different cultural or linguistic backgrounds” (p. 17). We feel that this definition aligns with the nature of LA-learner interactions described by the Odyssey program, which refers to the sharing of two cultures—that of the LA and of the L2 learner (What is Odyssey?, n.d.), and is thus appropriate for our study.

2.5 Aspects of Culture

In this study, we looked to Weaver’s (1986) cultural iceberg model to define two types of cultural aspects that appeared in our data, what we refer to as surface and deep culture aspects. Guided by this model, surface culture aspects refer to elements such as language, behaviour, customs and traditions. Deep culture aspects, on the other hand, refer, for example, to beliefs, values, assumptions and thought processes.

2.6 Intercultural Communicative Competence

Byram (1997) defines intercultural communicative competence as: “knowledge of others; knowledge of self; skills to interpret and relate; skills to discover and/or to interact; valuing others’ values, beliefs, and behaviors; and relativizing one’s self. Linguistic competence plays a key role [...]” (as cited in Deardorff 2006, p. 248). This study will adopt Byram’s definition of intercultural communicative competence and is framed around Byram’s (1997) conceptual model of Intercultural Communicative Competence.

In the field of L2 and FL learning, there are five main conceptual frameworks for intercultural (communicative) competence: Bennet’s (1993) Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS), Gudykunst’s (1993) Anxiety/Uncertainty Management Model (AUM), Byram’s (1997) Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence, Deardorff’s (2006) Process Model of Intercultural Competence, and Lussier’s (1997) Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence. In brief, Bennet’s (1993) Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) traces individuals’ evolution from “ethnocentric” to “ethnorelative” as a result of intercultural interactions; Gudykunst’s (1993) Anxiety/Uncertainty Management Model (AUM) revolves around self-awareness as a way to connect with other cultures and has been commonly used in study abroad contexts;

Byram’s (1997) Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence focuses on attitudes, knowledge and skills as central to building intercultural relationships; and Deardorff’s (2006) Process Model of Intercultural Competence centers on the process of building attitudes, knowledge, and internal and external outcomes that support intercultural competence development (see Moeller & Nugent, 2014, p. 4). Finally, Lussier’s (1997) model of Intercultural Communicative Competence focuses on intercultural knowledge, skills and existential competence and has been applied in studies that examine the cultural representations that language learners form as a result of (inter)cultural experiences (e.g., Amireault 2007; Amireault, 2002; Lussier, Auger, Clément, Lebrun- Brossard, 2000-2008).

Moeller and Nugent (2014) suggest that Byram’s (1997) model of ICC is well adapted for FL and L2 learning3 because of its focus on TL use during intercultural communication. In addition to this, we find Byram’s

(1997) Model of ICC appropriate for our study for the following reasons. First, Byram’s model was designed for an educational context and promotes the development of ICC through intercultural communication in a FL. Similarly, L2 learners in our study will participate in intercultural encounters with LAs using their second language in an educational setting. Second, intercultural communication4 is integral to the cultural component of the

Quebec English as a Second Language program. A review of the program’s bibliography reveals sources that focus on intercultural communication and reference Byram’s (1997) work on ICC (e.g., Huber-Kriegler, Lázár, & Strange, 2003) (see Ministère de l’éducation et enseignement supérieur, n.d.). Finally, Byram’s (1997) model focuses on the development of ICC through five savoirs: attitudes, knowledge, skills and critical cultural awareness. Our reading of the objectives of the Odyssey program reveals commonalities between Byram’s (1997) definitions of attitudes, knowledge, skills, and citizenship, as conceptualized in the component critical cultural awareness.

2.7

Byram’s (1997) Model of Intercultural Communicative

Competence

2.7.1 Overview

Byram’s (1997) model of Intercultural Communicative Competence (Figure 1) is a prescriptive model for the development of ICC in an educational context. Comprised of linguistic, sociolinguistic, discourse, and intercultural competence (Byram, 1997, p. 56), the model is made up of five savoirs5: attitudes (savoir être),

3 Byram (1997) specifies that the model of ICC is designed for both FL and L2 contexts (p. 4).

4 Byram (1997) labels the components of his model, “factors in intercultural communication” (p. 34). Intercultural

communication is defined as interactions between people of different countries or cultures in which at least one interlocutor is using a FL and all interlocutors are drawing on the knowledge of their own and other interlocutors’ social identities to create mutually comprehensive meanings (Byram, 1997, p. 31-2).

5 Byram (1997) uses the French term ‘savoir’ to refer to the components in his model. This choice of terminology stems

knowledge (savoirs), skills of interpreting and relating (savoir comprendre), skills of discovering and interacting (savoir apprendre/faire) and critical cultural awareness (savoir s'engager). These components are interrelated and revolve around the fifth savoir, and last addition to the model, critical cultural awareness.

2.7.2 Origins

Byram (1997) explains the model of ICC was born of the communicative approach in language teaching that developed in response to Hymes’ (1972) seminal work on communicative competence. Byram notes that the model builds on van Ek’s (1986) model of Communicative Ability and includes theories in applied linguistics and sociolinguistics, such as, Tajfel’s, (1981) social identity theory, Gudykunst’s (1994) cross-cultural communication theory and Bourdieu’s (1990) theory of cultural capital, which come together to shape its cultural aspects of communication (Byram, 2009, p. 322; Byram, 1997).

Byram’s model of ICC seeks to remediate two main discrepancies resulting from the transfer of Hymes’ (1972) model of communicative competence to communicative FL pedagogy: (1) the underdeveloped cultural dimension of language learning and cross-cultural communication in Hymes’s (1972) model and (2) the tendency to posit the native speaker as a model for all aspects of FL acquisition, including cultural competence, advanced by other models (i.e., van Ek’s (1986) model of Communicative Ability) (Byram, 1997, p. 10). As such, it rejects the notion of the native speaker as a model for FL learning and proposes an alternative ideal, the individual who can

see and manage the relationships between themselves and their own cultural beliefs, behaviours and meanings, as expressed in a foreign language, and those of their interlocutors, expressed in the same language—or even a combination of languages—which may be the interlocutors' native language, or not. (Byram, 1997, p. 12)

This individual is referred to as the intercultural speaker6.

2.7.3 The Savoirs: Components of Byram’s (1997) Model of Intercultural

Communicative Competence

The five components of Byram’s model of ICC are attitudes, knowledge, skills of interpreting and relating, skills of discovering and interacting, and critical cultural awareness.

“conserve() the elegance of French terminology in which knowledge, skills and attitudes can be described as different

savoirs” (Byram, 1997, p. 55).

6 On a basic level, an intercultural speaker is someone who possesses some degree of the five savoirs (Byram, 2009, p.

327). On a more complex level, the concept of the intercultural speaker is tied to the notion of intercultural citizenship, embodying tenants of the 5th savoir, critical cultural awareness (Byram, 2009, p. 327).

2.7.3.1 Attitudes (savoir être)

Attitudes are the foundation of the model of ICC. Defined as “curiosity and openness, readiness to suspend disbelief about other cultures and one’s own” (Byram, 1997, p. 50), attitudes are the entry point to ICC and the “first factor the learner must address” (Moeller & Nugent, 2014, p. 3). Byram’s (1997) conceptualization of attitudes finds its roots in Allport’s (1979) work on intergroup contact which asserts that attitudes of individuals towards different social groups tend to be negative or stereotypical (Byram, 1997, p. 34). Recognizing that these types of attitudes can be a barrier to successful communication, the model aims to develop unbiased interpretations of people from different countries or cultures belonging to the same or different social groups (Byram, 1997, p. 34-5). Byram notes that this component of the model is influenced by concepts from the field of psychology such as ‘decentering’ (Kohlberg et al., 1983), ‘alteration’ (Berger & Luckmann, 1966) and ‘tertiary socialisation’ (Byram, 1989b; Doyé, 1992), processes that allow individuals to develop objectivity and construct attitudes that facilitate intercultural communication.

2.7.3.2 Knowledge (savoirs)

Knowledge is divided into two broad categories: “knowledge of social groups and their products and practices in one’s own and in one’s interlocutor’s country, and knowledge of the general processes of societal and individual interaction” (Byram, 1997, p. 51). The first type of knowledge is relational and is always present to some degree. It is first acquired through the process of socialization and later refined through formal education. Knowledge gained through formal education often revolves around national culture and identity. However, individuals also develop other identities simultaneously through formal and informal socialization. Knowledge, therefore, includes recognizing that individuals have multiple identities. The second type of knowledge is theoretical and pertains to knowing about the processes of interaction at individual and societal levels. This knowledge must be explicitly learned and includes how to act in specific situations (Byram, 1997, p. 36). Finally, Byram, Gribkova and Starkey (2002) underscore that knowledge does not mean knowing specific facts about a given culture but rather includes knowledge of social groups, identities and other factors that come to play in intercultural interaction.

2.7.3.3 Skills of Interpreting and Relating (savoir comprendre)

The skills of interpreting and relating are defined as “the ability to interpret a document or event from another culture, to explain it and relate it to documents from one’s own” (Byram, 1997, p. 52). The act of comparing documents or events from two or more cultures allows the intercultural speaker to gain new perspectives of FL cultures and identify where misunderstandings might occur (Byram et al., 2002, p. 8). In the process, interpreting and relating may lead to the discovery of similarities, differences, and misunderstandings and the intercultural speaker faces the task of managing these (Byram, 1997, p. 37). Unlike the skills of discovering and interacting, interpreting and relating may be carried out individually, with or without social interaction (Byram, 1997, p. 37).

2.7.3.4 Skills of Discovering and Interacting (savoir apprendre/faire)

The skills of discovery and interacting are defined as the “ability to acquire new knowledge of a culture and cultural practices and the ability to operate knowledge, attitudes and skills under the constraints of real-time communication and interaction” (Byram, 1997, p. 52). The skill of discovering involves both instrumental and interpretive knowledge, the former pertaining to the knowledge that is required to discover new ways of functioning in a foreign environment and the latter, allowing individuals to grasp cultural nuances and understand other countries without necessarily leaving their own (Byram, 1997, p. 38). The skill of discovering may occur during, or in the absence of social interaction. Social interaction is one form of discovery that involves time constraints and individuals’ perceptions and attitudes. The skill of interacting is characterized by an ability to manage these constraints during communication with different interlocutors in a variety of situations (Byram, 1997, p. 38).

2.7.3.5 Critical Cultural Awareness (savoir s’engager)

Critical cultural awareness is the last component in the model of ICC. Defined as the “ability to evaluate critically and on the basis of explicit criteria perspectives, practices and products in one’s own and other cultures and countries” (Byram, 1997, p. 53), critical cultural awareness contributes to the formation of FL learners who are sensitive to the reasons behind their interlocutors’ behaviours as well their own (Byram, 2010). Critical cultural awareness has been compared to the philosophy of politische Bildung in West German education tradition (Byram, 2009, p. 323). Bildung encourages learners to critically reflect on their values, beliefs, and actions through the study of other cultures (Byram, 2009, p. 323). In the literature, Bildung has been linked to FL education (see Hansen, 2004 as cited in Kramsch, 2004) and political education (see Doyé, 1993 as cited in Byram, 1997; Byram, 2008). Likewise, critical cultural awareness is associated with participation in international civil society and citizenship (Byram, 2008).

2.8 Rationale for Focussing on Attitudes and Knowledge

This study focused on two of the five dimensions of Byram’s (1997) model of ICC, attitudes (savoir être) and knowledge (savoirs). While it would have been interesting to consider learners’ perceptions of all five components of the model of ICC, this would have fallen outside the scope of this master’s thesis. We chose, therefore, to focus on the two most examined components of ICC in the research literature, attitudes and knowledge.

Figure 1: Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence (Image source: Byram, M. (1997) Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters)

Chapter 3 Review of the Literature

In this chapter, we discuss research that has been conducted on the use of language assistants to support FL learning (3.1) and intercultural (communicative) competence in FL learning (3.2) and then look at two relevant studies from the Canadian context (3.3). This review of the literature is not exhaustive, rather, key studies have been selected to illustrate what is currently known about the impact of language assistant programs on FL learning and the development of ICC in FL and L2 learning settings. As will be evident, no empirical studies have addressed both research streams. In section 3.4 we summarize the literature reviewed and in section 3.5, present the research question and sub-questions.

3.1 Language Assistant Programs

Despite their mainstream popularity, language assistant programs have received little attention in the research literature. Indeed, several scholars (Ehrenreich, 2006; Macaro et al., 2014; Murphy-Lejeune, 2002; Wallace-Dargent, 2013) underscore the need for further research on these programs to better understand their impact on the actors involved (LAs, teachers, learners).

Existing research on language assistant programs focuses on the experience of being an LA in a foreign country (Alred & Byram, 2002; Murphy-Lejeune, 2002; Wallace-Dargent, 2013), interactions between LAs and their school supervisors (Culpeper, Crawshaw, & Harrison, 2008), social support systems for LAs living abroad (Ruble, 2011), and the use of LAs to enhance learning in both FL (Lynch & Anderson, 2001; Macaro et al., 2014; Martin & Mitchell, 1993) and CLIL (Dafouz & Hibler, 2013; Hibler, 2010; Lorenzo et al., 2010; Méndez García & Pavón Vázquez, 2012). The following paragraphs will examine studies that address the use of language assistants in FL and CLIL learning contexts.

3.1.1 Language Assistants in FL Learning

Martin and Mitchell (1993) give one of the earliest accounts of LAs in the FL classroom in their evaluation of the Basingstoke Language Awareness Project in the United Kingdom. The project, designed to promote and support FL learning in primary schools, featured the use of French, German and Spanish foreign language assistants (FLAs) to increase opportunities for students to communicate in their TL, learn about TL cultures, and overcome national stereotypes by building intercultural awareness. Qualitative data collected over nine months revealed that FLAs provided opportunities for students to communicate in their TLs through activities and games and enabled them to enrich their knowledge of foreign languages and cultures by exposing them to authentic learning materials (e.g., audio-visual, storybooks) and sharing information about their home countries. In terms of intercultural awareness, while it was anticipated that one of the advantages of FLAs would be to help students overcome national stereotypes, the study does not empirically measure developments in students’ intercultural

awareness as a result of learning with FLAs. Nevertheless, this early look at LAs in the FL classroom highlights how they can be used to support learning and raises an interesting question about the role they might play in confronting stereotypes that has not been attended to in the research to date.

In a more recent study, Lynch and Anderson (2001) explored the use of an English-speaking course assistant in an English for Academic Purposes (EAP) course at a university in Scotland. The study aimed to determine whether different types of communication might occur between adult EFL learners (n=18) and the course assistant (n=1), compared to learners and teachers (n=2), and gain insight into learners’ perceptions of their interactions with the two types of educators. Data in the form of parallel recordings of learner-assistant and learner-teacher utterances were collected over six weeks and analysed comparatively in terms of the frequency and nature of the episodes. A post-course questionnaire was also administered to learners. Findings reveal that the assistant created more and different types of opportunities for learners to communicate in the TL and learn about TL cultures. For example, recordings showed that learners spoke as often about language-related items with the course assistant as with the teachers, but that the assistant initiated more discussion about planning strategies during preparation for in-class activities. The recordings also reveal that learners spoke twice as much about themselves with the assistant than with the teachers. Data from the questionnaire provided a potential explanation for this, revealing that some learners felt more confident speaking with the assistant in their FL because her role was perceived as less pedagogical. Learners’ responses also illustrated that talking to the assistant was a way for them to grow accustomed to native speakers and gain exposure to different types of cultural information by discussing ‘real-life’ topics like living as a foreigner in Scotland. Finally, although the majority of learners perceived the assistant as an added benefit to the EAP course, one participant disagreed, stating that her role was unclear.

Concern around the role of LAs has been addressed in the literature in recent years. Studies (Ehrenreich, 2006; Hibler, 2010) show that, despite the longevity of language assistant programs, their roles can still be perceived as ambiguous by both teachers and LAs. It seems important, therefore, to learn more about the use of LAs in language learning to better understand how they may impact students’ target language and (inter)cultural development.

3.1.2 Language Assistants in CLIL

Another context that has employed LAs to enhance FL learning is CLIL. Similar to immersion or content-based instruction, CLIL has the two-fold objective of increasing learners’ knowledge of academic subjects and of a foreign language.

In Spain, English CLIL programs in the Madrid area host a growing number of English-speaking LAs to “assist local teachers and promote students’ FL and intercultural competence” (Dafouz & Hibler, 2013, p. 655). Several recent studies have examined teacher-LA collaborations in these classrooms.

In one such study, Hibler (2010) investigated interactions between LAs and teachers to identify best-practice uses of LAs in an English CLIL program in Andalusia. Observations of interactions between LAs (N=15) and non-native speaker teachers (N=15) revealed that LAs acted as models of FL pronunciation, created opportunities for students’ output in the TL and assumed the role of cultural informants. A pilot questionnaire administered to LA participants revealed, however, that while the majority of LAs enjoyed working in the program, they also faced challenges. For example, forty percent (40%) of LAs stated that they did not understand their role and fifty percent (50%) noted that they would have liked to have been more involved in classroom activities. Therefore, while this study sheds light on the ways LAs can enrich FL learning, it also underscores the need to systematically assess the Spanish language assistant program to ensure that LAs are employed in ways that will optimize both students’ learning as well as their own experiences in English CLIL classrooms.

Building on Hibler (2010), Dafouz and Hibler (2013) examined interactions between LAs and teachers team-teaching in primary English CLIL classrooms in Spain to determine how language further shapes their roles as FL educators. Data were collected using a pilot questionnaire (Hibler, 2010) and via recorded observations of interactions between LAs (n=6) and teachers (n=6) during six team-teaching sessions. Comparative analysis of the interactions, coupled with analysis of pre-recorded data produced by the Regional Education Department7, revealed qualitative differences in the discourses produced. For instance, LAs tended

to employ indirect rather than direct speech acts more frequently than teachers and they exposed learners to a more conversational style language, confirming like results by Lorenzo, Casal, and Moore (2010). LAs also played a role in scaffolding learners’ language and content learning by recasting the main teachers’ utterances (Méndez García & Pavón Vázquez, 2012). Moreover, in demonstrating that the use of LAs in English CLIL exposed learners to varied speech acts, this study highlighted a new dimension to the role of the LA that moves beyond that of a cultural and FL informant previously discussed in the literature and supported by the Spanish regional government (Dafouz & Hibler, 2013, p. 666). In sum, the results of this study support the idea that LAs and teachers have different but significant roles as FL educators in CLIL. Recommendations for future research include examining the ways in which LAs’ and teachers’ discourses impact classroom pedagogy and FL learners. In light of the studies reviewed above, it is evident that another area could benefit from further investigation, that is, learners’ intercultural development and how learning with LAs might influence it. In fact, while learning with LAs is presumed to increase students’ intercultural awareness (Martin & Mitchell, 1993) and

intercultural competence (Dafouz & Hibler, 2013), this element of the language assistant research is underdeveloped.

The next section will look at studies that have addressed intercultural (communicative) competence in L2 and FL learners in Canada and abroad.

3.2 Intercultural (Communicative) Competence in FL Learning

Recent studies in the field of L2 and FL learning have explored the question of intercultural competence in teachers (Bastos & Araújo e Sá, 2014; Sercu et al., 2005; Young & Sachdev, 2011), student teachers (Czura, 2016), language assistants (Alred & Byram, 2002; Wallace-Dargent, 2013) and language learners. Research on learners has examined learners’ intercultural (communicative) competence in study abroad (e.g. Durán Martínez, Gutiérrez, Beltrán Llavador, & Martínez Abad, 2016; Hismanoglu, 2011; Root & Ngampornchai, 2012; Salisbury, An, & Pascarella, 2013), in the context of Internet Communication Technology (Dowd, 2003; Lawrence, 2013; Peiser, 2015), and in classroom-based learning in immersion (Moloney, 2007; Moloney & Harbon, 2010) and L2 and FL language programs. In the following paragraphs, we report on research that has examined intercultural (communicative) competence in L2 and FL learners in a classroom setting and look at two relevant studies conducted in Canada.3.2.1 Intercultural Communicative Competence in FL Learners in a Classroom

Setting

Research investigating ICC in FL learners in a classroom setting has been conducted in several countries around the world and has primarily targeted primary and post-secondary learners. Overall, studies show that language learners demonstrate manifestations of ICC and suggest that an intersection of factors present inside and outside of the classroom contribute to its development. Of the many factors identified (e.g., socioeconomic status, gender, ethnic identity, academic achievement, TL level, curriculum, opportunities for contact with TL speakers), exposure to intercultural knowledge acquired through learning materials and opportunities to engage with TL speakers are commonly cited.

3.2.1.1 Exposure to Intercultural Knowledge Acquired through Learning Materials

In a mixed methods study of EFL learners’ intercultural attitudes (Byram, 1997), Ahnagari and Zamanian (2014) investigated if exposure to intercultural texts, containing information about the TL culture, could impact learners’ attitudes towards the TL and its speakers as well as their scores on a final language proficiency test. Forty-eight (N=48) intermediate EFL learners from two intact classes at a language institute in Iran participated in the study. A Preliminary English Test (PET) determined that the participants were homogenous in terms of TL levels and they were divided into an experimental (n=24) and control group (n=24). Over two months, both groups received 3.5 hours of EFL instruction per week focused primarily on reading tasks. In addition to these tasks, the

experimental group received exposure to TL cultural information related to the unit topics presented. Data collected through a final proficiency test measured against the previously administered PET and questionnaire showed that the experimental group demonstrated evidence of increased positive attitudes towards communication and interaction with native speakers compared to the control group. Furthermore, findings indicated that the experimental group scored higher on the final language test than the control group, suggesting that positive attitudes towards the TL culture, fostered by interculturally enriched learning, may have also benefited participants’ TL proficiency.

In another study of intercultural attitudes (Byram, 1997), Houghton (2014) explored attitudes of curiosity towards study abroad in EFL learners enrolled in a course designed to develop intercultural communicative competence at a university in Japan. Specifically, the study investigated how exposing learners to materials designed to incite interest in study abroad might influence their attitudes towards it. Seven (N=7) upper-intermediate/advanced learners participated in the 13-week study. Data, consisting of learners’ written assignments were analyzed using the Intercultural Dialogue Model (Houghton, 2012), an operationalized form of Byram’s (1997) model of ICC. Results revealed that some learners demonstrated attitudes of curiosity towards studying in TL countries which may have been shaped by the intercultural teaching materials. One activity that was particularly successful was the opportunity for learners to acquire new knowledge about TL countries and cultures from peers who had previously studied abroad. In addition to demonstrating curiosity, it was reported that some learners showed a willingness to actively acquire more information about TL countries as a result of their peers’ accounts. When it did not, however, findings suggest that reflecting on cultural information allowed them to gain greater self-awareness about their reasons for not wanting to study abroad which, for certain learners, involved the process of identifying and challenging stereotypes. Exposure to intercultural learning materials, therefore, was viewed as effective in developing learners’ intercultural attitudes regardless of whether students developed an interest in studying abroad or not.

3.2.1.2 Opportunities to Engage with TL Speakers

The intercultural literature also suggests that opportunities to engage with TL speakers might influence learners’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural aspects of ICC.

In an action research study of EFL learners studying English and intercultural communication at a university in Japan, Houghton (2010) explored the nature of stereotypes and the role of education in managing them by examining how conscious raising tasks derived from the ICC literature8 might enable students to identify,

reflect on and revise common stereotypes. Thirty-six (n=36) students and one teacher-researcher (n=1)

8 Intercultural communicative competence, for its ability to encourage reflexive thinking and self-awareness, was viewed

participated in the study. Qualitative data collected over nine months in the form of audio-recordings of classes, data from student work and teacher and student diary entries revealed that students were able to identify both positive and negative stereotypes and, moreover, recognize the need to address negative ones. Interestingly, data from diary entries showed that interviews with foreigners, one conscious-raising task, played an important role in allowing students to become cognizant of their own stereotypes and provided new information that they could use to revise them. The author found that the student-led interview encounters allowed students to reconstruct common perceptions of the interviewees’ and their cultures and furthermore, that they demonstrated signs of metacognitive awareness and control in the process. In brief, this study demonstrates that students can identify and reconstruct common stereotypes, including their own. Conscious-raising activities, including opportunities to interact with TL speakers and opportunities to reflect on these encounters appears to have been beneficial to achieving this. Finally, the author notes that experiential learning may be one way to tackle harmful stereotypes by developing students’ metacognitive awareness and control, two pre-requisites for critical cultural awareness development.

Finally, in a mixed-methods study that examined FL learners’ perceptions of the importance of Intercultural Understanding (IU), the cognitive, attitudinal and behavioural dimensions of Byram’s (1997) model of ICC, Peiser (2012) revealed that opportunities to interact with TL speakers was one factor that positively influenced students’ IU. Male and female students (N=765) studying French, German and Spanish as a FL in 14 grammar and comprehensive primary schools9 participated in the study. Quantitative and qualitative data

were collected using a questionnaire comprised primarily of 5-point Likert Scale items (N=765) and focus group interviews (n=5). Results show that learners’ perceptions of the importance of IU were influenced by a wide range of sociodemographic factors that varied from school to school and from student to student and included socio-economic status, gender, academic achievement, teachers’ understanding of IU, intercultural knowledge gained in the classroom and opportunities for travel. With regard to socioeconomic status, which was closely linked to opportunities to travel, the study revealed that the socioeconomic status of learners’ schools did not make a difference in their attitudes towards other countries. However, it did play a role in shaping their opinions about the importance of IU to their current and future lives. Data showed that students in comprehensive schools perceived language learning and learning about other cultures to be less important than students in grammar schools. These findings were also mirrored with regard to confidence communicating in another language. The author suggests that opportunities to travel to TL countries, which typically involves some degree of contact with TL culture and speakers, may be one factor that influenced students’ perceived language ability as well as their perceptions of the relevance of IU in their present and future lives. In conclusion, this study reveals that primary

9 In the UK, both grammar and comprehensive schools are state-funded; however, grammar schools select their pupils by