HAL Id: hal-01611017

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01611017

Submitted on 5 Sep 2018

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Inverse gas chromatography a tool to follow

physicochemical modifications of pharmaceutical solids:

Crystal habit and particles size surface effects

María Graciela Cares Pacheco, Rachel Calvet, G. Vaca-Medina, A. Rouilly,

Fabienne Espitalier

To cite this version:

María Graciela Cares Pacheco, Rachel Calvet, G. Vaca-Medina, A. Rouilly, Fabienne Espitalier.

In-verse gas chromatography a tool to follow physicochemical modifications of pharmaceutical solids:

Crystal habit and particles size surface effects. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Elsevier,

2015, 494 (1), pp.113-126. �10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.07.078�. �hal-01611017�

Inverse

gas

chromatography

a

tool

to

follow

physicochemical

modifications

of

pharmaceutical

solids:

Crystal

habit

and

particles

size

surface

effects

M.G.

Cares-Pacheco

a,*

,

R.

Calvet

a,

G.

Vaca-Medina

b,c,

A.

Rouilly

b,c,

F.

Espitalier

aaUniversitédeToulouse;MinesAlbi,UMRCNRS5302,CentreRAPSODEE;CampusJarlard,F-81013Albicedex09,France bUniversitédeToulouse;INP-ENSIACET,LCA,310130Toulouse,France

cINRA;UMR1010CAI,310130Toulouse,France

Keywords:

D-mannitol

Polymorphism Surfaceenergy

Inversegaschromatography Spraydrying

Cryomilling ABSTRACT

Powders are complex systems and so pharmaceutical solids are not the exception. Nowadays, pharmaceuticalingredientsmustcomplywithwell-defineddraconianspecificationsimposingnarrow particlesizerange,controlonthemeanparticlesize,crystallinestructure,crystalhabitsaspectand surface properties of powders, among others. The different facets,physical forms, defectsand/or impuritiesofthesolidwillalteritsinteractionproperties.Apowerfulwayofstudyingsurfaceproperties isbasedontheadsorptionofanorganicorwatervaporonapowder.Inversegaschromatography(IGC) appearsasausefulmethodtocharacterizethesurfacepropertiesofdividedsolids.

TheaimofthisworkistostudythesensitivityofIGC,inHenry’sdomain,inordertodetecttheimpactof sizeandmorphologyinsurfaceenergyoftwocrystallineformsofanexcipient,D-mannitol.Surface

energyanalysesusingIGChaveshownthattheaformisthemostenergeticallyactiveform.Tostudysize andshapeinfluenceonpolymorphism,pureaandbmannitolsampleswerecryomilled(CM)and/or spraydried(SD).Allformsshowedanincreaseofthesurfaceenergyaftertreatment,withahigher influenceforbsamples(gd

sof40–62mJm!2)thanforamannitolsamples(gdsof75–86mJm!2).Surface

heterogeneityanalysisinHenry’sdomainshowedamoreheterogeneousb-CMsample(62–52mJm!2).

Moreover,despiteitssphericalshapeandquitehomogeneoussizedistribution,b-SDmannitolsamples showedaslightlyheterogeneoussurface(57–52mJm!2)also higherthantherecrystallizedb pure

sample("40mJm!2).

1.Introduction

Pharmaceuticalsolids mustcomply withwell-defined speci-ficationsintermsofbioavailability,solubility,toxicityandstability. Nowadays, the requirements are more and more draconian, imposingnarrowparticlesizerange,controlonthemeanparticle size, crystalline structure, crystal habits aspect and surface propertiesof powders,among others. Alargeset ofoperations is developed to answer these requirements. The processes for producingfinepowders(aroundmicrometer)arevariedasmelt quenching,grinding, freeze-drying,spray drying,crystallization, antisolventprecipitation,milling,andsupercriticalfluids. Depend-ing upon the nature of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs),it is known that thepreparation methodinfluencesthe

physicalstabilityandcrystallizationbehavior.Theimpactofthese processes on solid phase transformations may lead to the formationofametastableoranamorphousform,oramixtures ofvariouscrystallineformsincludingotherhydrates(orsolvates). Thesechangesaredesiredforcertainstagesoftheformulationor forsomeusepropertiesoftheAPI,butsometimescanalsohave undesirableeffectsonthesolid.

Inversegaschromatography(IGC)appearsasatooltostudythe changes on surface properties in order to highlight process influencestoassessdrugdeliverysystemsperformance. Mechani-cal operations are the most studied processes to determine pharmaceuticalsolidssurface’sbehavior.Mostauthorsdescribed an increase of the dispersive component of the solid surface energy,

g

ds,aftermechanical grinding(Table1).Thisincreaseis

generallyattributedtotheexposureofspecificcrystalfacetsthat presentdifferentchemicalgroups,theformationofhigherenergy zonessuchascrystaldefects,dislocationsand/ortosolidsstate transformations(Chamarthyet Pinal, 2008; Feeley etal., 2002;

* Correspondingauthor.

Fengetal.,2008;Hengetal.,2006;Hoetal.,2012;Newelland Buckton,2004).

1.1.Surfaceenergy,particlessizeandsurfacechemistry

Duetotheanisotropicnatureofpowders,theexhibitionofnew crystalfacesundermillingcanchangetheacidic/basiccharacterof the solid depending on the functional groups present in the exposed facets. Heng et al. (2006) highlighted the anisotropic natureofformIparacetamolcrystals.Theconfrontationofsessile dropandIGC,allowedthemtoconcludethatgrindingleadstoa fragmentation of thefacet(010),which possesses theweakest attachmentenergyandexhibitsthelarge

g

ds.Thus,aftermillingthe

g

dsofthesamplesincreased,showingamorehydrophobicsurface,

withdecreasingparticlesize.

York et al. (1998) were interested in the milling of DL

-propranololhydrochloride.Theevolutionof

g

dsshowedtodepend

on the particles size. During milling the surface becomes increasinglymoreenergetic(gd

sfrom45to61mJ/m2forparticles

75–16.5

mm)

untilreachedaplateaufollowedbyasmallfalling

dsforthefinestpowder(<10

mm).

Theauthorsconcludedthatthe increasesing

ds,andin

Dg

adsusingCH2Cl2asprobemolecule,are duetoafragmentationreleasingthedominantcrystalface,which possesthelowestattachmentenergyandisrichinnaphthalene groups. Attrition might become significantas millingintensity increase releasingfaceshavingOHgroups,naphthaleneand Cl! ions.Trowbridgeetal.(1998)highlightedthatacetaminophensize reductionfrom30to10

mm

leadedtoanincreaseofg

dsfrom50.9to

61.3mJ/m2andtoanincreaseof

Dg

adsfrom327to506J/mol,using chloroformasprobemolecule.Millingalsoincreasesthe hydro-phobicandbasiccharacterofacetaminophensurface.Thisresults

are in agreement with those obtained by molecular modeling whichestablishedthatmillingleadstotheexposureofthecrystal facet (010) which contain an hydrophobic methyl group, a benzeneringandacarboxylgroup,bothbasic.

OhtaandBuckton(2004)studiedsurfaceenergeticchangesof cefditorenpivoxil,acephalosporinantibiotic,asconsequenceof milling.After grinding in a vibration mill,the authorsfound a decreaseinthe

g

dsaccordingtothegrindingtime,from52.3mJ/m2before milling to 45.8mJ/m2 after 30min of grinding with a decreaseinsolidcrystallinity.Inaddition,theauthorshaveshown adecreaseinthesolidacidiccharacter withanincreasedonits basicity.Theseeffects areattributedtotheexposureofcarbonyl groups,whichhaveanelectrondonatingnature.

Luneretal.(2012)studiedbyIGCtheimpactofhighshearwet milling(HSWM)anddrymilling(DM)onthesurfacepropertiesof two pharmaceutical compounds, succinic acid and sucrose. Physicochemical characterizationof both samples showed that bulk properties were unaffectedby wet and dry milling while surfacepropertiesanalysesshowedanincreaseofsolidsdispersive surface energyafter DMand HSWM.Succinic acidsamples,

g

d s=35mJ/m2,exhibitminordifferencesbetweendrymilledandwet milled samples, 40#2mJ/m2, attributed to minimal impact of cleavageandtheexposure ofcrystal facetswithsimilaratomic surface arrangements. For HSWM sucrose, the polarity of the solvents used during wet milling influenced

g

ds of the milled

samplesfrom55to71to91mJ/m2,for hexane,methyltertiary butyl ether and ethanol respectivelywhile dry milled samples exhibita

g

dsof44mJ/m2.Differencesbetweendryandwetmilling

processeswereattributedtotheattritionmechanisminpresence ofsolvent.

ReducingparticlesizemayalsobenecessaryfortheAPItoreach thetargetorgan,particularlywhenthedrugadministrationisby Nomenclature

as(m2/g) Specificsurfaceareaofthesolid d(n,0.5)(mm) Numbermediandiameter D[y,0.5](mm) Medianvolumediameter

Dg

ads(J/mol) Molarfreeenergyvariation foran isother-maladsorptionofprobemolecules m(g) Samplemassn(mol) Desorbedmolenumber

nads(mmol/g) Adsorbedmolenumberpergramofsolid nm(mol) Monolayercapacityornumberofadsorbed

molescorrespondingtoamonolayer P(Pa) Vaporpressureorpartialpressure Psat(Pa) Saturationvaporpressure T(K) Temperature

Tc(K) Columntemperature tN(min) Netretentiontime VN(cm3) Netretentionvolume

Wadh(J/m2) Workofadhesionwhenadsorptionoccurs n/nm(–) Surfacecoverage

Greeksymbols

g

dl (J/m2orN/m) Liquidsurfaceenergy(orsurfacetension)

g

ds(J/m2orN/m) Dispersive component of solid surface

energy

g

s(J/m2orN/m) Totalsurfaceenergyofasolidg

sps (J/m2orN/m) Specific component of solid surfaceenergy

u

s(–) SurfacecoverageTable1

Anoverviewoftheinfluenceofparticlessizereductionoverthesurfaceproperties ofpharmaceuticalingredientsbyIGC.

Pharmaceuticalsolid gd

s Reference

Acetaminophen " Trowbridgeetal.(1998)

Hengetal.(2006)

Cefditorenpivoxil # OhtaandBuckton(2004)

DL-propanololhydrochloride " Yorketal.(1998)

Felodipine " ChamarthyandPinal(2008)

Griseofulvine

ChamarthyandPinal(2008)

" Feng etal.(2008) OtteandCarvajal(2011)

# Otteet al.(2012)

Ibipinabant " Gambleetal.(2012)

Indomethacin " Planinseketal.(2010)

Limetal.(2013)

Lactose

Ahfatetal.(2000) Feeleyetal.(2002) NewellandBuckton(2004)

" Thielmannetal.(2007) Shariareetal.(2011) BrumandBurnett(2011) Jonesetal.(2012) Mannitol " Hoetal.(2012) Salbutamolsulfate " Ticehurstetal.(1994) Feeleyetal.(1998)

SalmeterolXinofoate " Tongetal.(2001,2006)

Dasetal.(2009)

Sucrose " SuranaHasegawaetal.et(2003)al.(2009) Luneretal.(2012)

inhalation. Nowadays, dry powder inhalers (DPIs) are of great interestthankstotheabsenceofpropellantandthestabilityofthe formulationasaresultofthedrystate.Asuccessfuldrugdelivery willdependontheinteractionbetweenthepowderformulation andthedeviceperformance.Duringinhalation,theAPIdetaching from the carrier by the energy of the inspired airflow that overcomestheadhesionforcesbetweentheAPIand thecarrier. Over the past few years, lactose has been considered as the excipientofchoiceinseveralsolidoraldosageformsandsomany studieshasbeencarriedonlactose,mostofthembasedonthe study of its physical–chemical properties as function of the manufacturingprocess(Pilceretal.,2012).Thus, whylactoseis alsothemoststudiedorganicsolidbyIGC.Feeleyetal.(2002)and

Shariareetal.(2011)studiedtheinfluenceofmillingonthesurface propertiesoflactose.IGCanalysesshowedalowsensitivityof

g

dsto

milling. However, the study of basic and amphoteric probes showed changes of the hydroxyl groups presented in lactose surface.Shariareetal.(2011)alsohighlightedthattheacidicor basiccharacterofthepowderseemstoberelatedtothesizeof startingparticles.Forsample,themicronizationoflargerparticles, 50–100

mm,

resultsinan increaseof thespecificcomponentof solidsurfaceenergy,g

sps,measuredwithTHF(basicprobe).Whilethemicronizationoffinerparticles,<20

mm,

leadstoanincreaseofg

sps usingamphotericprobesmoleculessuchasacetone.1.2.Surfaceenergyandcrystallinesolidstate

Tongetal. (2001, 2006)studied theinfluenceof solid–solid interactionsontheaerosol performanceofsalmeterolxinafoate (SX)polymorphsandlactosecarrierbyIGC.SXisahighlyselective bronchodilator, known to exist in two crystallineforms. Three activebatchesofSXweregenerated:thetwopolymorphs,SXIand SXII,crystallizedusingsolutionenhanceddispersionby supercrit-icalfluidsfrommethanolsolution(SEDS)andaformcalledMSXI generated by the micronisation of the SXI form. First of all, dispersivesurfaceenergyanalysisbyIGCexhibitsa moreactive MSXIsample(gd

SXI"33mJ/m2,gdSXII"29mJ/m2and

g

dMSXI"39mJ/m2).IGCwasalsoappliedtocalculatethecohesionbetweenSX samplesandtheadhesionbetweenthesamplesofSXandlactose. Thestudyof thestrengthdrug–drugcohesion anddrug-carrier adhesion suggests that the active particles of SX bond more stronglytothecarrierparticlesoflactosethattothoseoftheirown species, except for SXII–lactose: SXI–SXI (190.7MPa), SXII–SXII (67.3MPa),MSX–MSX(245.0MPa),SXI–lactose(212.6MPa)SXII– lactose(47.5MPa),MSXI–lactose(278.1MPa).Theuseoflactoseas acarrierimprovesaerosolperformanceabout25%forthebatchSXI and140%forthebatchMSXI.

Traini et al. (2008) studied by IGC the lactose–salbutamol sulfateinteractionsinDPIformulations.Theaimwastoinvestigate lactose pseudo-polymorphs,

a-anhydrous,

a-monohydrate

andb-anhydrous,

in terms of carrier functionality. In this work,a-monohydrate

formexhibitsbestaerosolperformance, indicat-ingthatcarriersurfacechemistryplaysadominatingroleinDPIs. The authors also highlighted an inverse relationship between surfaceenergyandaerosolefficiency.Morerecentlystudieshasbeencarriedoutinordertoprovidea substitutefor

a-lactose

monohydrateascarrierin DPI formula-tions.Indeed,lactosepossessesseveraldrawbacksduetoitsbovine origin,its incompatibilitywithamino groups likepeptides and proteinsanditstendencytobecomeamorphousaftermechanical treatment. Nowadays, mannitol appears to be an adequate substituteforlactosebecauseit doesnotcarry reducinggroups thatmaycausechemicalinteractionwithproteinsandishighly crystallineevenuponspraydrying(Maasetal.,2011).SurfaceenergyanalysisofD-mannitolhasbeenfocusedonthe

stable

b

form.IGChashighlighteditsacidicnature,attributedto thehighdensityofhydroxylgroupsatmannitolsurface(Saxena etal.,2007).Morerecentlyresearchwerefocusedontheeffectof millingand/orsurfaceenergyheterogeneityofthestableb

form (Hoetal.,2010, 2012).Our previousresearchwork,Caresetal. (2014),was focusedonthestudyofD-mannitolpolymorphs.D-mannitol pure polymorphs exhibit a more active and highly heterogeneous

a

form(74.9to45.5mJ/m2)withalessactiveand quitehomogeneousstableb

mannitol("40–38mJ/m2),whichalso behave similarly to the instabled

form. Mannitol particles, generated by SD, have been used commercially in bronchial provocationtest(Aridol).Tangetal.(2009)studiedtheimpactof different generation processes in particles to improve aerosol performance.Threepowdersampleswereprepared:byconfined liquidimpingingjets(CLIJs)followedbyjetmilling(JM),SDandJM. These processes generated quite different powder samples, needle-shape for CLIJs samples, spherical for SD samples and orthorhombique for theJM samples. Dispersivesurface energy analysisbyIGCexhibitsamoreactiveCLIJssampleattributedtothe presence ofa

mannitol (gdCLIJs"85mJ/m2,

g

dSD"60mJ/m2 andg

dJM"48mJ/m2). Particles shape showed to be an important

contributor totheaerosol performanceofmannitol powdersas itaffectsthesurfaceenergyandparticlesdynamics.

Yamauchi et al. (2011) studied physicochemical differences with emphasis on the surface properties, by IGC and DVS, of niclosamideandnaproxensodiumandtheirrespectiveanhydrate anddehydratedhydratedforms.Thenaproxensodiumanhydrate formshowedahigher

g

dsandhigherrateofmoisturesorptionthan

thedehydratedhydratedform,whereastheoppositewasobserved forniclosamide.

1.3.Surfaceenergy,defectsandamorphization

Many APIs are poorly soluble in water, which limits their bioavailability.Theirrateofdissolutionmayimprovebyusingan amorphous phase of the API. Indomethacin (IDMC) is a good example.IDMCisanantipyreticandanti-inflammatorydrugused inmanypharmaceuticalformulations,ithasfourpolymorphsand anamorphous.Accordingtothegrindingtemperature,belowor higher than its glass transition temperature (Tg), and grinding intensitythemoststableformatambientconditions,

g-IDMC,

can transformtothemetastablea

formorleadtoanamorphousstate (Crowleyand Zografi, 2002; Desprez and Descamps, 2006). As IDMCishighlyinsolubleinwater(0.02mg/mL),thebioavailability oftheproductanditsabsorptionbythegastrointestinaltractcan beimprovedbyusinganamorphousformofthedrug(Imaizumi etal.,1980).Planinseketal.(2010)studiedthecrystallinefraction thattransformsintoamorphousformsuponintensivemilling.IGC wasusedtodetectsurfacechangescausedbymillingcrystallineg-IDMC

whileDSCwasusedtodeterminethemass(orequivalent volume) fraction of the samples transformed. The authors determinedthatthedispersiveenergyofthestableg-IDMC

was 32.2mJ/m2andthatoftheamorphous,generatedinaballmillfor 120min,of43.3mJ/m2.Studiesontheinfluenceofmillingtime, allows theauthors toillustrate thesensitivity of theIGC-ID to detectcrystalsurfacedefectsashigh-energysites(gd30min=

g

d60min=g

damorphe).Bycomparingtimeevolutionoftheamorphousfraction

ofthesurfacebyIGCandvolumebyDSCtheauthorsshowedthat surfacetransformsathigherrate(anorderofmagnitude)thanthe bulkphase.IGCseemstobeapowerfultooltoquantifyamorphous rateandtolocateitbytheconfrontationwithbulk(orvolume) measurementtechniques(BrumandBurnett,2011).

Thedevelopmentofcost-efficienttechnologiesforthe genera-tionofdrugpowderswithdesiredphysicochemicalpropertiesis stillachallengeforpharmaceuticalcompanies.Toactuallydefinea successfulprotocolitseemsnecessarytostudysurfaceenergyasa functionofpolymorphism,surfacechemistryoftheexposedfacets, particlessizeandshape(crystalhabits).Nevertheless,ascanbe depicted, it is quite difficultto actually distinguish each effect influence.Theobjectiveofthisworkistoquantifytheeffectofsize andcrystalhabitsinsurfaceenergyofanAPI,D-mannitol.

Tostudyparticlessizeandshapeinfluenceonsurfaceenergetics ofD-mannitolpolymorphstwotechniquesareused:spraydrying

and/orcryomilling.Asmannitolisknowntobehighlycrystalline evenduringmillingorspraydrying,sizereductionprocessesusedin thisworkwereestablishedinwaysthatpolymorphssolidssamples donotundergoanyphasetransformation.IGCatinfinitedilution (IGC-ID)isusedto studysolidsurfaceanisotropyatlowsurface coverage,whileDVSwillbeusedtohaveamoreglobalviewofthe interactionpotential.Thedualaimofthisworkistohighlightthe impact of sizeand crystal habitsontheadsorption behavior of differentanhydrousformsofD-mannitolandtocomparethesurface

energydeterminationtechniquesusedpointingouttheirrelevance consideringthephysicalsenseofthemeasure.

2. Materialsandmethods 2.1.Materials

D-mannitolwasgenerouslyprovidedbyRoquette(France).The

batch, Pearlitol 160C, is composed of 99% of

b

mannitol mass percentageandonly1%ofsorbitol.Highpuritydeionizedwater (18MVcm)wasobtainedfromalaboratorypurificationsystem. Thenon-polarprobesoctane,nonaneanddecanewerepurchased fromSigma,assay>99%.2.2.Generationandformulationprotocols 2.2.1.Crystallization

Pure

b

anda

formsweregeneratedbyantisolventprecipitation (acetone)andbyseedingandfastcoolingrespectivelyasdescribed previouslyinCaresetal.(2014).2.2.2.Spraydrying(SD)

Theexperimentswereperformedusingalaboratoryminispray dryer BüchiB-290 equipped with a two-fluid nozzleof 0.5mm diameter.Theflowrateoftheaqueousmannitolsolutions,10g/L,is setat6mL/min andtheatomizingairrateat600NL/h.Airinlet temperatureissetto120$Cwhileoutlettemperaturewasmeasured

byatemperaturesensorintheairexitpoint,noted87$C.Torecover

the powder the aspiration is set to 35m3/h (maximum level). Sampleswerestoredatroomtemperatureundervacuuminglass desiccatorscontainingsilicagel(relativehumidityof6%).

2.2.3.Cryomilling(CM)

ARetschcryogenicimpactmillwasusedformilling.Samplesof around500mgwereplacedinstainlesssteelgrindingjarsof5mL containingonestainlesssteelgrindingballof5mmdiameter.The samples were milledfor 4 cycles in total, each consistingof a 10mingrindingtimeat25Hzfollowedbyintervalsof0.5minat 5Hz. Thesampleswere continuallycooled withliquidnitrogen beforeandduringthegrindingprocess.

2.3.Particlesphysicochemicalcharacterization 2.3.1.Chemicalpurity

ThechemicalpurityofeachsamplewascheckedbyHPLCusing a Hi-Plex Caligandexchange column coupledwitha refractive

index detector (analysis conditions: mobile phase HPLC grade water,flowrate0.3mLmin!1,columntemperature45$C).

2.3.2.Polymorphsfingerprints

Themannitolpowdersampleswereanalyzedusingdifferent techniquestoconfirmtheidentityofthedifferentpolymorphs. X-ray powder diffraction patterns (XRPD) were obtained using a PANanalytical X’Pert Pro MPD diffractometer (set-up Bragg– Brentano).Diffractiondataisacquiredbyexposingthepowders samplestoCu-Karadiationatavoltageof45kVandtoacurrentof 40mA.Thedatawerecollectedoverarangeof8–50$2u&atstep

size of 0.03$. Quality diffraction patterns were obtained in a

relativelyshortexposuretime(20min).Dataanalysisisdonewith theX’Pert Data Collector softwarewhile phase identificationis madewithPANalyticalHighScoreMoresoftwareanddatabases “ICDD Powder Diffraction File 2” and “Crystallography Open Database”.

FT-Raman spectra were recorded with an atomic force microscopeequipped witha confocal Ramanimaging upgrade, Alpha300fromWITec.Amagnificationof50%andanexcitation source of Nd:YAG (532nm) were used. The Raman data were acquired using WITec Project Plus software that hasa 16 bits resolutionandasamplingrateof250Hz.

Thermalanalysis was performed witha DSC Q200 fromTA Instrument.Samplesamountofabout3–5mgareplacedin non-hermeticaluminumpanels,inthetemperaturerangeof20–200$C

ataheatingrateof5$C/minundernitrogenatmosphere.Nitrogen

flow was adjusted at 50mL/min. All data measurements are averagesof atleast3 measureson3differentsamples.Heatof fusionvalues weredeterminedusinga sigmoidbaselinewitha standarddeviationoflessthan0.5%(6measuresaverage). 2.3.3.Sizeandparticleshapeanalysis

Particle shape analyses were examined using a XL30 SEM, scanning electron microscopy, witha field emission gun (FEG) operatingat15or20kV.Sampleswereplacedontodoubled-sided adhesiveandcoatedwithPlatinumfor4minusinganautosputter coaterSC7640underargongaspurge.

The particle size analysis was performed by image analysis usinganopticalbancPharmaVisionSystemPVS830fromMalvern Instruments.Toseparatetheparticles,apressureof6barwasset (SPD1300). Thenumber of particlestobe analyzedwas setat 70,000.Two objectifswereused“zoom3” whichcananalyzea particlesizerangebetween310and7.5

mm,

witharesolutionof 7mm

and “zoom 5” which allows to analyze a particle range between100and1.7mm

witharesolutionof3mm.

2.3.4.Surfaceanalysistechniques

SpecificsurfaceareaandsurfaceenergyanalysesofD-mannitol

polymorphs were carried out using an IGC–Surface Energy Analyser(IGC–SEA)fromSMS.Eachpowdersamplewaspacked intopre-silanisedcolumnsof300mmlengthand4mminternal diameter, plugged with silanised glass wool. Prior to analysis, eachcolumnwasconditionedat50$Cfor 2hat0%RH.Helium

wasusedasacarriergasat10sccmandthecolumntemperature was fixed at 30$C during the analysis, all experiences were

undertakeninidenticalconditions.Theretentiontimesofprobe moleculesandmethaneweredeterminedusing aflame ioniza-tion detector (FID).Deadvolume wasdeterminedby methane injections and dispersive surface energy determination by a homologous series of n-alkanes (n-decane, n-nonane and n-octane).Dispersivesurfaceenergyprofileswerecalculatedusing Cirrus Plus software (version 1.2.3.2 SMS, London) following Dorris-Grayapproach.Thecorrespondingsurfacecoverage,

u

s,at each injection concentrationis theratiobetween thedesorbedamount,n,determinedfrompeakareaandthemonolayercapacity ofthesolid,nm(us=n/nm).Inourexperiments,nmwasdetermined fromthespecificsurfaceareavalueobtainedbyIGC–SEAusing n-nonane as probe molecule. Full details of the experimental procedure and analysis by IGC have beenpublishedpreviously (Caresetal.,2014).

3. Results

3.1.D-mannitoldepartsamples

3.1.1.Powdercrystallinityandpurity

XPRDpatterns of thecommercial formP160C and the pure forms

b

anda

mannitolareshowninFig.1.Asitisdepictedfrom thefigure,a

mannitol hascharacteristic reflectionpeaksat 2u positionsof13.7$, 17.3$and19.9$and21.4$whileforb

mannitolarelocated at 14.7$, 18.8$, 23.6$ and 29.5$. No differences in the

characteristicreflectionpeaksbetweenthecommercialpowder

Pearlitol160Cand the

b

pureformwerefound, thedifferences betweenpatternspeaksintensitycanbeattributedtomorphology differencesbetweenbothsamples.Indeed,sorbitolpresencesin the commercialpowder P.160C is not detected byXPRD but is detectedbyDSC(Table2).AsshowninFig.2,thefirstendothermic peakat81.4$C,isconsistentwiththemeltingpointofa-sorbitol

(Nezzal et al., 2009) which decreasesboth heat of fusion and meltingpointof

b

polymorph.It should be noted that the detection of small quantities is complexandmaydependonthelocationofsorbitolwithinthe powder,neartothesurfaceorwithinthebulkofthecrystals. 3.1.2.Particlessizeandhabit

As described in our previous work, the commercialsample Pearlitol 160C (P160C) is composed by irregular sticks with a medianvolume diameterD[y,0.5]of 64

mm

and a D[y,0.9]of 250mm

(Fig.3a).Theb

formgeneratedbyantisolvent precipita-tion is formedby better-defined sticks withsmoother surfaces (Fig.3b), and it has a D[y, 0.5]of 26.7mm

and a D[y, 0.9]of 81.7mm.

Itseemsthatforbothsamples,thesmallerparticlesget stuckonthesurfaceofthelargestones.The

a

formisthefinestonewithneedle-shapemorphologyand aD[y,0.5]of25.3mm

andaD[y,0.9]of42.4mm

(Fig.3c).Itshould benoticethatparticlessizeanalysisusingPVS830seemstobenot welladaptedforthea

formanalysis.InfactSEManalysisshoweda narrowersizedistribution.ItispossiblethatPVS830characterizes particlesagglomerationsdue tohighercohesionforcesbetween theseparticles. 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 x 104 2θ Intensity P.160C (1) β (2) α (3) (1) (2) (3)Fig. 1.X-raypatternsofdepartsamples,aandbmannitolandthecommercialform Pearlitol160C.

Table2

Summaryofphysicalsolid-statecharacterizationobtainedbyDSC.

P160C b-form a-form

Heatoffusion(Jg!1) 300.2 304.5 294.4

0.4 – –

Meltingpoint(onset)($C) 165.6 166.7 165.3

81.4 – –

3.2.Spraydriedsamples(SD)

Twosamplesweregeneratedbyspraydryingtwodifferent

b

mannitolbatches.Thefirstonecorrespondtoapureb

mannitol obtainedbyantisolventcrystallizationandthesecondbatchtothe commercialpowderPearlitol160C. Theabbreviationsb-SD

and P160C-SDareusedinthismanuscripttodifferentiatethem. 3.2.1.PowdercrystallinityandpurityXPRDpatternsrevealedthatthetwoSDsamplesarecomposed ofthestable

b

form(Fig.4).Thesmallpeakpresentat17.3$canbeattributedtothepresence,inreallysmallquantities,of

a

mannitol. Neverthelessnotothercharacteristicpeaksfromthea

formwere found in thepatterns. Moreover,DSC and Ramanspectroscopy analysis do not corroborate thepresence ofa

mannitol in the samples.Thedifferencesbetweenthepatternspeaksintensitycan beattributedtothemorphologydifferences.SomeprotocolstospraydryD-mannitolaqueoussolutionscan

befoundintheliterature,differentiatinginpolymorphs genera-tion.Forexample,Leeetal.(2011)obtainedonlythestable

b

form afterSDwhileMaasetal.(2011)showedthatoutlettemperatures at/below90$Cgeneratedmainlyb

mannitolandsmallamountsofa

mannitol (around 5%). Outlet temperatures up to 140$Cincreased

a

mannitolconcentrationwithinthesamples(between 5 and 15%). Nevertheless, in our experiences, with an outlet temperatureof87$C,DSCandRamanspectroscopyanalysisdonotdetectedthepresenceofthe

a

formintheSDsamples.3.2.2.Particlessizeandhabitbyscanningelectronmicroscopy(SEM) ImageanalysisobtainedwithPVS830cannotbeusedforthe analysisofspraydriedsamples.Infactthemostpowerfulcamera lens “zoom 5” does not measure particles smaller than 3

mm,

whichseemstobeaquiteimportantpopulationaccordingtoSEM analysis.In addition,thedispersionprotocolusedwiththeSPD 1300 does not seem to actually disperse the particles. Finally, crystalhabitsandsizeanalysishasbeenexploitedbySEM.Froma microscopic point of view(10–20

mm),

the powders obtained after spray drying are homogeneous in size and morphology. SEM micrographs show quite spherical particles withdiametersbetween300nmand10mm

anda“quite”smooth surface (Figs. 5 and 6). These values are smaller than those obtained by Maas et al. (2011) which despite the observed differencesinparticleformation,theparticlessizedistributions obtainedatdifferentoutlettemperatures(60,90and120$C)areveryclosed, witha meandiameter of 13

mm.

The authorsalso highlightedthatthespraydryingofmannitolatdifferentoutlet temperaturesmodifiesparticlesurfacetopography.Intheircase dryingat60$Cleadstotheformationofacicularcrystalwithasmoothparticlesurface.Incontrast,athighertemperatures,the dropletsevaporatemuchfasteranddonotrecrystallize immedi-atelybecauseofthelownucleationrateatthistemperature.Evenif there is expectedthat water evaporate prior crystallization, no difference in particle size were obtained. Thus, the authors assumedthatthenucleationandcrystalgrowthalsooccursina

Fig.3.SEMmicrographsof(a)commercialpowderPearlitol160C,(b)purebmannitoland(c)pureamannitol.

10 15 20 25 30 35 40 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7x 104 2θ Intensity β (1) Pearlitol SD (2) β−SD (3) 17.3° (2) (1) (3)

ratherearlydryingstageduetothehighdynamicinthespraydryer and the presence of crystalline seeds that may triggerearliest crystallization. In fact, since thecrystals grow larger in higher temperatures and because of the fast solvent evaporation, the formingshellbecomesquicklyveryrigidandtheopeningsofthe

hollow particles can be seen. In our case, with an outlet temperatureof87$C,someoftheparticlesexhibitaroughsurface

andsomeothershowedtobehollowwithawellvisibleorificein their shell (Figs. 5 and 6). SEM analyses were limited due to samplesdegradationforamagnificationhigherthan6400%.

Fig.5. SEMmicrographsofpurebmannitolsampleafterspraydrying.

Finally,nodifferencesinsizeandparticlesshapewerefound between

b-SD

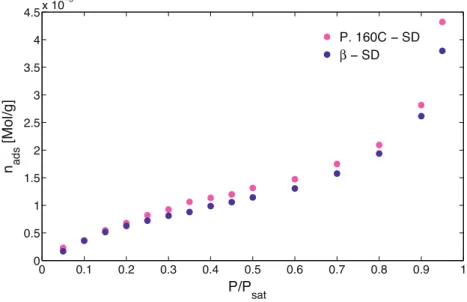

(Fig.5)andP.160-SD(Fig.6)samples.3.2.3.Surfaceenergyanalysis

Afterspraydrying

b-SD

andP160C-SDpresentedanincrement oftheirspecificsurfaceareaandsoanincreaseofthevaporprobes adsorbedamount(Table3)allowingDVSanalysis.Thus,bothSD samples, exhibit a similar adsorption behavior with a type II isotherm(Fig.7).Surface energy values obtainedby DVS were calculatedtakingintoaccountcontactangle valuesobtainedby capillary rise (Cares et al., 2014). The error associated to the measureis1mJm!2.The

g

dsvaluesobtainedbyDVSofb-SD

andP160C-SDsamplesaresimilartothoseobtainedbyIGCforthe

b

pureform(Table3). IGC-IDanalysesshowthatb-SD

andP160C-SDsampleshave similaradsorptionbehavior(Table3).Moreover,g

ds valuesofSD

Table3

Specific surfaceareas anddispersivesurfaceenergiesofdifferentD-mannitol samples.The“X”representstheanalysisthatcannotbedone(techniquelimits) while“–”representstheonesthathavenotbeingdone.

D-mannitol as(m2g!1) gd s(mJm!2) ASAP-Ar IGC-C9 DVS IGC us=0.04% us=0.1% us=1% us=8% P160C 0.4 0.4 X 70.7 69.1 58.0 44.9 a 8.4 8.5 51 74.9 75.0 72.1 45.5 b 2.8 0.4 X 40.9 40.9 39.4 38.2 P160C-SD 3.4 4.0 40 62.6 62.3 55.4 X b-SD 2.9 4.4 41 57.2 57.3 51.7 X a-CM – 11.9 – 85.6 81.7 70.7 X b-CM 3.6 3.3 47 61.9 62.0 52.4 X 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 4.5 x 10−5

P/P

satn

ads[Mol/g]

P. 160C − SD

β

− SD

Fig.7. Adsorptionisothermsofb-SDandP160C-SDobtainedbyDVSusingn-nonaneasvapourprobe.

0 0.001 0.002 0.003 0.004 0.005 0.006 0.007 0.008 0.009 0.01 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75

n/n

mγ

s d[mJ/m

2]

β β − SD P. 160C P.160C − SDsamplesarebiggerthanthoseofthe

b

pureformbutsmallerthan those obtainedforthe commercialpowderP160C (Fig.7).This tendencyofthesamplestohavesimilaradsorptionbehaviorafter spraydryingcanbeexplainedbytheevolutionoftheparticlesto thesamesizeandcrystalshabit.Itseemsimportanttohighlight thattheg

dsofP160C-SDisapproximately5mJm!2biggerthantheoneof

b-SD

forallsurfacecoveragestudied(0.0004<n/nm<0.01). Thisdifference,superiortotheexperimentalerror(<1.3mJm!2), can be attributed to the sorbitol presence in the commercial powder P160C, which one is conserved after spray drying the sample.Itappearsthatsmallquantitiesofsorbitolinthepowders (lessthan1%)increasethestrengthofdispersiveinteractionsofthe soliddispersion.Afterspraydryingthesampleswecanfoundaregionwherethe retentiontime doesnotdependontheinjectionvolume(Fig.8, dottedlinen/nm<0.02).

3.3.Cryogenicmilledsamples(CM)

The

a

andb

D-mannitolpolymorphsgeneratedbysuccessiveprecipitationprotocolswerecryogenicmilledinordertochangeits sizeandhabitstructurewithoutchangingtheirsolid-stateform. Theabbreviations

b-CM

anda-CM

areusedinthismanuscriptto identifythecryomilledpowders.3.3.1.Powdercrystallinityandpurity

XRPD patterns were used to confirm polymorphism and to ensure the physical form of the samples.

a

mannitol has characteristicreflectionpeaksat2upositionsof13.7$,17.3$ and19.9,whilefor

b

mannitolarelocatedat14.7$,18.8$and23.6$.AsshowninFig.8,both

a

andb

puresampleskeeptheirpolymorphic formaftercryomilling.ParticlehabitandsizechangesafterCMcan bedepictedasadecreaseofthecharacteristicpeaksintensity. 3.3.2.Particlessizeandhabitbyscanningelectronmicroscopy(SEM)SEMmicrographsoftheCMsamplesareshowninFigs.10and 11. The

a-CM

samples areformedby agglomeratesof approxi-mately50mm

composedbysmallneedle-likeparticles,andalsoby agglomeratesof biggerparticles alwaysin needle-like shapeas illustratedinFig.9.Thecloserzoomsshowthatfora-CM

samples thedirectionofthefracturefollowsparticlesgeometry.Infact,it seemsthatcrystalsfracturefollowsaplaneperpendiculartothe longitudinalaxisoftheneedle.The SEM analysis of the

b-CM

samples showed particles agglomerations. The powder seems to be composed by quite irregularparticleshabitsbetweensomemicrometersand80mm.

A largequantityofsmallparticlesseemstobestickaroundthebigger ones. For this polymorph the fracture behavior aftercryogenic millingismorecomplexandthesolidseemstohaveamorebrittle behavior(Fig.11).The results obtained by image analysis using the PVS830 showedforthe

b-CM

aD[y,0.1]of8mm,

D[y,0.5]of16mm

andD [y,0.1]of30mm

whileforthea-CM

samplesaD[y,0.1]of9mm,

D [y,0.5]of24mm

andD[y,0.1]of40mm

wereobtained.NorealFig.10.SEMmicrographsofamannitolcryomilledsamples.

10 15 20 25 30 35 40 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10x 104 2θ Intensity α (1) α − CM (2) β (3) β − CM (4) (3) (1) (4) (2)

differences were detected between the samples using this technique. The image analysis by SEM and by PVS830 differs, mostofallduetoparticlesagglomeration.

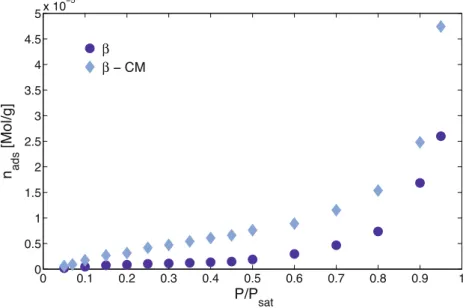

3.3.3.Surfaceenergyanalysis

After cryogenic milling both samples,

b-CM

anda-CM,

increasedtheirspecificsurfaceareas.Thisincrementallowedto analyzebyDVStheb-CM

samplesthankstoanincrementofthe mass up-takeat reallylowpartial pressures,revealinga typeII adsorptionbehavior(Fig.12).Thispointisquiteimportant,indeed ifsolid/probe moleculesinteractionshowed atype IIIisotherm, probe–probemoleculesinteractionswillbestrongerthatprobe–solidinteractionsandsotheretentiontimemeasurebyIGCwill notberepresentativeoftheadsorptionphenomenon.

Duetothelow amount ofexperimentaldata(adsorbedamountas functionofP/Psatrangedbetween0and"0.2),between3and4,and thelowcorrelationcoefficientsobtainedwiththeDVSdata,the specificsurfaceareacalculationshavebeencarriedoutusingIGC. AsshowninTable3,anincreaseinthedispersivesurfaceenergy of

b

anda

cryogenicmilledsamples,atlowsurfacecoverage,has beenobserved.Nevertheless,forthea-CM

samplethisdifference, withthea

puresample,tendstodecreaserapidlywithincreasing theinjectedamount.Indeed,forsurfacecoveragesuperiorsthan 0.1%bothsolids,a

anda-CM,

havesimilaradsorptionbehavior.Fig.11.SEMmicrographsofbmannitolcryomilledsamples.

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 4.5 5 x 10−5

P/P

satn

ads[Mol/g]

β

β

− CM

The

b-CM

sample hasa similarbut more energeticadsorption behaviorthan theb

pure form.The regionwhereg

ds doesnotdependoninjectionvolumecorrespondtoaradion/nmlowerthan 0.002.Nevertheless,The

b-CM

sampleismoreheterogeneous,at low surface coverage, than theb

pure sample. This more heterogenic adsorption behavior can be attributed to the anisotropicmorphologyoftheb-CM

particles(Fig.13).4. Discussion

4.1.Henry’sdomaindeterminationbyIGC

Thefirstpointtohighlightisthataftertreatment,spraydrying and cryogenic milling, the Henry’s domain of each sample is reducedtoreallylow surfacecoverage’s(us<1%).Thus, surface energysolidanalysesdonotallowedtorepresentthewholesolids surfacebutallowedustodifferentiatebatchesbehavior.

Itshouldbenoticethatthelinearityoftheisotherm,indicated by its correlation coefficient, plays a key role over the

determination of themaximum

u

sthat define Henry’sdomain, andshouldbewelldefinedinthistypeofanalysis.Forexample,for theb-SD

samples,ifweacceptthelinearityoftheisothermfor R2>0.99,aR2=0.998correspondstoaP=40Paandsotoau

s=10% (Fig.14a)whileaR2=0.999correspondstoaP=140Paandsotoa

u

s=40%(Fig.14b).Nevertheless,wecanseethatevenifR2ishigher taking account higher pressures, the data fit used does not representquitewellthefirstpoints.Thus,inthiscase,pressures smallerthan40PaareusedtodescribeHenry’sdomain.As

g

ds isdeterminatebytheinjectionofaseriesofalkanesn-octane,n-nonaneandn-decane,Henry’sdomainwillbe determi-nate by the probe having the narrowest Henry’s domain. As expected,thelongerthechainsofalkanes,thesmallerthelinear region of theadsorptionisotherm.Sointheseexperiences, the limitsurfacecoveragetostudysurfaceenergybyIGCintheinfinite dilutionregionwillbedeterminedbytheanalysisofn-decane.

Ahighcontroloftheinjectionsizeasanimportantnumberof experimental data points it is fundamental to determine with precisionHenry’sdomain.

0 0.001 0.002 0.003 0.004 0.005 0.006 0.007 0.008 0.009 0.01 40 50 60 70 80 90

n/n

mγ

s d[mJ.m

−2]

α

α

− CM

β

β

− CM

Fig.13.Surfaceheterogeneityanalysisofaandbmannitolsamples,beforeandaftercryogenicmilling(CM).

4.2.Dispersivesurfaceenergy

Itisquitedifficulttolinkcrystalhabit,sizeandagglomeration statetosurfaceenergy.Generally,surfaceenergydifferencesafter physical treatmentsuch as milling,micronization, CM evenSD amountothers,aregenerallyattributedtochangesinparticlessize (surfacearea),morphology(habits), polymorphism(or amorph-ization)andtotheexposureofmoreenergeticallyactiveplanes. Duringourexperienceswetookcaretonotchangethesolidstate ofthesamples,thusnosolid/solidtransformationswereobtained. Moreover ithasbeendeterminedthatfor

b

mannitol,themost energeticallyactiveplane,intermsofdispersivesurfaceenergy, hasag

dsof44.1#0.6mJm!2(Hoetal.,2010).AllthisindicatesthatsurfaceenergyincrementsafterCMandSDcannotbeattributedto the exposure of new and more active phases or to solid-state transformationsaftertreatment.Thus,crystalsizeand morpholo-gychangesseemtoberesponsibleofsurfaceenergyincrementsin

b

mannitolsamples.Nevertheless,wecannotseparate particles size effectof crystalshabiteffectover thesolid surface energy because CM and SD influence at the same time these two parameters.AsshowninTable3,aftercryogenicmillingandspraydrying treatment,

a

andb

mannitolsamplespresentedanaugmentation ofitsdispersivesurfaceenergy,atreallylowsurfacecoverage.For theb

form, three batches of different size and shape were generated. Thefirstoneobtainedbyantisolventprecipitationis composed by well defined sticks with smooth surfaces D[y, 0.5]=26.7mm

andD[y,0.9]=81.7mm

(Fig.3b).Theb-SD

sampleis composedbywelldefinedspheresbetween1and4mm

(Fig.5a) while the batchb-CM

is composed byagglomerationsof quite irregular particles, of few micrometers to 90mm,

with small particlesstuckonthesurfaceofthelargerones(Fig.10).IGCanalysis revealedthatthesethreebatcheshavedifferent surface behavior. After CM and SD the samples are more energetically active due to a change in thecrystal habits. The

b-recrystallized

form appears as a quite homogeneous solid ("40mJm!2)whiletheb-CM

batchandtheb-SD

batchshoweda moreheterogeneoussurface,energeticallyspeaking.Itshouldbe notedthatdespiteitssphericalshapeandquitehomogeneoussize distribution,b-SD

samples showed a slightly heterogeneous surface(57.3–51.7mJm!2).Thisconfirmsthattheparticlessurface isnotassmoothasdepictedbySEManalysis.Surfaceenergyanalysesatreallylowsurfacecoverage,allowus todifferentiatetheCMsamplesoftheSDsamples:for

b-CM

ag

dsof61.9mJm!2whilefor

b-SD

ag

ds of57.2mJm!2at

u

s=0.04%.Theb-CM

particles are quite damaged and seem to have surface defects (Fig. 11). These surface irregularities can be seen as privilegedsiteswhere theprobemoleculescan beadsorbedby undergoing interactions from more than one surface. Surface energyanalysesat reallylowsurfacecoverageemphasizethese differences. Indeed, if the injection volume is incremented,u

s>0.1%, the surface energy differences betweenb-CM

andb-SD

samplestendtodisappearandbothsolidstendtosimilar adsorptionbehavior ("52mJm!2). Nevertheless,at this surface coveragebothsampleshaveahigherg

ds thanthedepart

b

form(52 to 40mJm!2, respectively). This difference can be still attributed to the influence of more energetically active sites related to size and crystal habit changes after SD and CM (Figs.5and11).

ItshouldbenotedthatifIGC-IDweredefinedforP/Psat"0.03,as mostauthorsdoit,wewouldworkedoutsideHenry’sdomainand wewouldalsomisleadtheeffectofparticleshabitsoversolid’s surfaceenergy.

DVSanalyses,whichprovidedameanvalueofthesolidsurface energy,showed that the

g

ds of

b-CM

samples (47mJm!2, pinkdotted line)is higher thanthe

g

ds of

b-SD

samples(40mJm!2,purpledottedline).Theseresultswithsurfaceenergyanalysesby IGC-ID showthe contributionof more active sites tothe solid averagesurfaceenergy(Fig.15).Moreover,IGC–DVSconfrontation clearlyshowsusthatifthemoreactivesitesarenotnumerous enoughornotsufficientlyhigherthanthemostenergeticactive crystalline face, its influence can be misled by the techniques whichprovidesameanvalueofthesolidsurfaceenergylikeDVS. Infact,meansurfaceenergyanalysescanmisleadtodifferentiate batchesandthusmisleadend-useproperties.

Forthe

a

form,twobatchesofdifferentsizesweregenerated but with its morphology partially conserved. Thea

mannitol generatedbysuccessiveantisolventprecipitationsiscomposedby needle-likeparticlesofD[y,0.5]=25.3mm

etD[y,0.9]=42.4mm.

Thea-CM

batch is formed by agglomerations of needle-like particles, between 20 and 50mm,

but somenon-agglomerated largerparticlescanalsobefound,alwaysneedle-like(Figs.3cand10).Surface energyanalysisshoweda moreenergeticallyactive

a-CM

sample. Nevertheless, this is only true at low surface0 0.001 0.002 0.003 0.004 0.005 0.006 0.007 0.008 0.009 0.01 35 40 45 50 55 60 65

n/n

mγ

s d[mJ/m

2]

β

β

− SD

β − CM

β

− SD

β

− CM

Fig.15.SurfaceenergyanalysisbyDVS(dottedline)andIGCofdifferentpurebmannitolbatches:bgeneratedbyantisolventprecipitation,afterspraydryingb-SDandafter cryogenicmillingb-CM.

coverage, indeed,for

u

s<0.005both samplesshoweda similar adsorptionbehavior(Fig.15).Alltheseresultscanbebetterunderstoodifthemathematical definitionoftheretentiontime istakenintoaccount.Infact,as alreadyhighlightedinpreviousstudies,tNitisthecontributionof manyinteractionssitesiandtheinteractionenergybetweenthe probeandthesitesi(Caresetal.,2014).So,ifthemoreactivesites arenotnumerousenoughitsinfluencecanbeattenuatedbythe presenceoflessactivesones,moreover,theinfluenceoflessactives siteswillbemoreimportantwhenincreasingtheinjectionsize. Thestudyofsurfaceheterogeneityathighersurfacecoveragecan giveamoregeneralideaofthispoint.Thus,for

a-CM

samples,it seemsthatthemoreactivesitescreatedbythisprocessarenot numerousenoughbecausethecryogenicmillingofa

puresamples seemstoonlygeneratesurfacedefects,whichonesseemtobeless activethanthemostenergeticallyactivefaceofthea

crystal.SurfaceenergyanalysisbyIGCatHenry’sdomainhighlighted the influence of particles habits and size over solid’s surface behavior.ThecombinedsetIGCandDVSvalidatedthisstatement. Nevertheless,itisquitedifficulttoseparatebotheffectsbecause mostprocessesaffectatthesametimesolid’shabitsandsize,even particles separation processes, such as sieving, are related to particlesmorphologies.

Fromacriticalpointofview,thestudyofsurfaceenergiesin Henry’sdomainbyIGC-ID,doesnotprovideaglobalideaofthe solidbehavior.Indeed,SDandCMsamplespresentedquitesmall linearadsorptionregion.Thus,only1%ofthesurfacecanbe“cover” tobeinHenry’sdomain(us<0.01).Sothequestionis,howfarare weofthesolid's“real”behavior;areweabletoactuallydistinguish crystallinefacetsinfluence(surfacechemistry),arethose impor-tant? It seems necessary tohave another technique of surface analysissuchasDVS,orevenmolecularmodeling.Itwillbealso interesting to study surface heterogeneity by IGC using an equipmentthatallowsahighersurfacecoverageandtouseother mathematicalmodelssuchastheenergydistributionfunction. 5. Conclusions

Powderbehaviordependsdirectlyofitsinterfacialinteractions, thusofthephysicalandchemicalcharacteristicsoftheparticlesof whichitiscomposed.Nevertheless,itisdifficulttolinkcrystalline structure,habits,particlesagglomeration state,sizedistribution and surfaceenergy. Classically, surfaceenergy incrementsafter physicalandmechanicaltreatmentsuchasgrinding,areattributed tochanges inparticlessize (surfacearea),morphology(habits), solidstatestructure(polymorphismoramorphization)and/orto theexposureofmoreenergeticallyactiveplanes.Inthisworkwe studiedtheinfluenceofparticleshabitsandsizedistributionover thesolidsurfaceenergy.Toachievethisgoal,twobatchesofpure

a

andb

mannitol,generatedbysuccessivecrystallizationprotocols, werecryogenicmilledand/orspraydried.Forthe

b

form,threebatchesofdifferentsizeandshapewere studied. The first one, obtainedby antisolvent precipitation, is composedbywelldefinedstickswithsmoothsurfaces,thesecond oneb-SD,

iscomposedbywell-definedsphereswhilethebatchb-CM

isformedbyagglomerationsofquiteirregularparticles.Itis quitedifficulttoseparatetheeffectofthesizefromtheeffectof particles habits because the two processes used, CM and SD, affectedatthesametimesolid’shabitsandsize.Moreover,even particles separation processes to study particles size, such as sieving,arerelatedtoparticlesmorphologies.IGC-IDstudieshighlightedsurfaceenergydifferencesbetween thesethree batches.Surface heterogeneity analyses, in Henry’s domain(0.0004<

u

s<0.01), showeda quite heterogeneousand more energetically activeb-CM

(61.9–52.4mJm!2) andb-SD

(57.2–51.7mJm!2)samples, and a quite homogeneous and lessactive

b

form("40mJm!2).Surfaceenergyanalysisatlowsurface coverage,u

s<0.01,allowedustodifferentiatetheSDsamplesof the CM samples. The solid size reduction, due to CM and SD, generatesanincrease ofthespecificsurfaceareaoftheb

pure powder,allowingDVSanalysisoftheb-CM

(47mJm!2)andb-SD

(40mJm!2)samples.For the

a

form, two batches of different size and a quite conservedneedle-likemorphologywerestudied.Thefirstbatch wasgeneratedbyseedingandfastcoolingwhilethesecondone,a-CM,

bythecryogenicmillingofthefirstsample.Surfaceenergy analysisatreallylowsurfacecoverage,u

s<0.005,showedamore energeticallyactivea-CM

sample.Theseresultsallowustoconcludethatparticleshabitsappear tobeamajorfactorinthesolidsurfaceadsorptionbehaviorofD

-mannitol polymorphs. Moreover, it seems that there is a “threshold”abovewhichtheinfluenceofmoreactivesites,here attributed to surface irregularities, is attenuated and different batches of a same polymorph tend towards similar adsorption behavior.Thisthresholddependsdirectlyofthevalueofthemore activesitesbutalsooftheirnumber.Ifthemoreactivesitesarenot numerous enough, or not sufficiently higher than the most energeticactiveface,itsinfluencewillbemisledbythetechniques whichprovidesameanvalueofthesolidsurfaceenergy.

IGC-IDprovideskeyinformationintermsofsurfaceenergyand appears to be a powerful tool to monitoring surface energy evolutionasfunctionofthegenerationprocessoraftermechanical orthermaltreatment.Evenifthesolidsurfaceanisotropyisweak and maybeundetectablebystandardanalytical methods,it can makethesolidmoreenergeticallyactiveandthusmorereactive. IGC-IDisabletodetectweaksurfaceenergyvariation,whichmay explain the behavior differences between batches, of a same polymorph, over time but also in atmospheres more or less moist.

Acknowledgment

InthememoryofElisabethRodier(1966–2014). References

Ahfat,N.M.,Buckton,G.,Burrows,R.,Ticehurst,M.D.,2000.Anexplorationof inter-relationshipsbetweencontactangle,inversephasegaschromatographyand triboelectricchargingdata.Eur.J.Pharm.Sci.9(3),271–276.

Brum,J.,Burnett,D.,2011.Quantificationofsurfaceamorphouscontentusing dispersivesurfaceenergy:theconceptofeffectiveamorphoussurfacearea. AAPSPharmSciTech12(3),887–892.

Cares-Pacheco,M.-G.,Vaca-Medina,G.,Calvet,R.,Espitalier,F.,Letourneau,J.-J., Rouilly,A.,Rodier,E.,2014.PhysicochemicalcharacterizationofD-mannitol polymorphs:thechallengingsurfaceenergydeterminationbyinversegas chromatographyintheinfinitedilutionregion.Int.J.Pharm.475,69–81.

Chamarthy,S.P.,Pinal,R.,2008.Thenatureofcrystaldisorderinmilled pharmaceuticalmaterials.ColloidsSurf.A:Physicochem.Eng.Aspects331(1), 68–75.

Crowley,K.J.,Zografi,G.,2002.Cryogenicgrindingofindomethacinpolymorphsand solvates:assessmentofamorphousphaseformationandamorphousphase physicalstability.J.Pharm.Sci.91(2),492–507.

Das,S.,Larson,I.,Young,P.,Stewart,P.,2009.Surfaceenergychangesandtheir relationshipwiththedispersibilityofsalmeterolxinafoatepowdersfor inhalationafterstorageathighRH.Eur.J.Pharm.Sci.38(4),347–354.

Desprez,S.,Descamps,M.,2006.Transformationsofglassyindomethacininduced byball-milling.J.Non-Cryst.Solids352,4480–4485.

Feeley,J.C.,York,P.,Sumby,B.S.,Dicks,H.,1998.Determinationofsurfaceproperties andflowcharacteristicsofsalbutamolsulphate,beforeandaftermicronisation. Int.J.Pharm.172(1),89–96.

Feeley,J.C.,York,P.,Sumby,B.S.,Dicks,H.,2002.Processingeffectsonthesurface propertiesofa-lactosemonohydrateassessedbyinversegaschromatography (IGC).J.Mater.Sci.37,217–222.

Feng,T.,Pinal,R.,Carvajal,M.T.,2008.Processinduceddisorderincrystalline materials:differentiatingdefectivecrystalsfromtheamorphousformof griseofulvin.J.Pharm.Sci.97(8),3207–3221.

Gamble,J.F.,Leane,M.,Olusanmi,D.,Tobyn,M.,Šupuk,E.,Khoo,J.,Naderi,M.,2012. Surfaceenergyanalysisasatooltoprobethesurfaceenergycharacteristicsof micronizedmaterials:acomparisonwithinversegaschromatography.Int.J. Pharm.422(1),238–244.

Hasegawa,S.,Ke,P.,Buckton,G.,2009.Determinationofthestructuralrelaxationat thesurfaceofamorphoussoliddispersionusinginversegaschromatography.J. Pharm.Sci.98(6),2133–2139.

Heng,J.Y.,Thielmann,F.,Williams,D.,2006.Theeffectsofmillingonthesurface propertiesofformIparacetamolcrystals.Pharm.Res.8,1918–1927.

Ho,R.,Hinder,S.,Watts,J.,Dilworth,S.,Williams,D.,Heng,J.,2010.Determinationof surfaceheterogeneityofD-mannitolbysessiledropcontactangleandfinite concentrationinversegaschromatography.Int.J.Pharm.387,79–86.

Ho,R.,Naderi,M.,Heng,J.,Williams,D.,Thielmann,F.,Bouza,P.,Keith,A.R.,Thiele, G.,Burnett,D.,2012.Effectofmillingonparticleshapeandsurface heterogeneityofneedle-shapedcrystals.Pharm.Res.29,2806–2816.

Imaizumi,H.,Nambu,N.,Nagai,T.,1980.Stabilityandseveralphysicalpropertiesof amorphousandcrystallineformsofindomethacin.Chem.Pharm.Bull.(Tokyo) 28(9),2565–2569.

Jones,M.D.,Young,P.,Traini,D.,2012.Theuseofinversegaschromatographyforthe studyoflactoseandpharmaceuticalmaterialsusedindrypowderinhalers.Adv. DrugDeliv.Rev.64(3),285–293.

Lee,Y.Y.,Wu,J.X.,Yang,M.,Young,P.M.,vandenBerg,F.,Rantanen,J.,2011.eof polymorphisminspray-driedmannitol.Eur.J.Pharm.Sci.44(1),41–48.

Lim,R.T.Y.,Ng,W.K.,Widjaja,E.,Tan,R.B.H.,2013.Comparisonofthephysical stabilityandphysicochemicalpropertiesofamorphousindomethacinprepared byco-millingandsupercriticalanti-solventco-precipitation.J.Supercrit.Fluids 79,186–201.

Luner,P.E.,Zhang,Y.,Abramov,Y.A.,Carvajal,M.T.,2012.Evaluationofmilling methodonthesurfaceenergeticsofmolecularcrystalsusinginversegas chromatography.Cryst.GrowthDes.12(11),5271–5282.

Maas,S.G.,Schaldach,G.,Littringer,E.M.,Mescher,A.,Griesser,U.J.,Braun,D.E., Urbanetz,N.A.,2011.Theimpactofspraydryingoutlettemperatureonthe particlemorphologyofmannitol.PowderTechnol.213(1),27–35.

Nezzal,A.,Aerts,L.,Verspaille,M.,Henderickx,G.,Rendl,A.,2009.Polymorphismof sorbitol.J.CrystalGrowth311,3863–3870.

Newell,H.,Buckton,G.,2004.Inversegaschromatography:investigatingwhether thetechniquepreferentiallyprobeshighenergysitesformixturesofcrystalline andamorphouslactose.Pharm.Res.21(8),1440–1444.

Ohta,M.,Buckton,G.,2004.Determinationofthechangesinsurfaceenergeticsof cefditorenpivoxilasaconsequenceofprocessinginduceddisorderand equilibrationtodifferentrelativehumidities.Int.J.Pharm.269(1),81–88.

Otte,A.,Carvajal,M.T.,2011.Assessmentofmilling-induceddisorderoftwo pharmaceuticalcompounds.J.Pharm.Sci.100(5),1793–1804.

Otte,A.,Zhang,Y.,Carvajal,M.T.,Pinal,R.,2012.Millinginducesdisorderin crystallinegriseofulvinandorderinitsamorphouscounterpart.CrystEngComm 14(7),2560–2570.

Pilcer,G.,Wauthoz,N.,Amighi,K.,2012.Lactosecharacteristicsandthegeneration oftheaerosol.Adv.DrugDeliv.Rev.64(3),233–256.

Planinsek,O.,Zadnik,J.,Kunaver,M.,Srcic,S.,Godec,A.,2010.Structuralevolutionof indomethacinparticlesuponmilling:time-resolvedquantificationand localizationofdisorderedstructurestudiedbyIGCandDSC.J.Pharm.Sci.99(4), 1968–1981.

Saxena,A.,Kendrick,J.,Grimsey,I.,Mackint,L.,2007.Applicationofmolecular modellingtodeterminethesurfaceenergyofmannitol.Int.J.Pharm.343,173– 180.

Shariare,M.H.,DeMatas,M.,York,P.,Shao,Q.,2011.Theimpactofmaterial attributesandprocessparametersonthemicronisationoflactose monohydrate.Int.J.Pharm.408(1),58–66.

Surana,R.,Randall,L.,Pyne,A.,Vemuri,N.M.,Suryanarayanan,R.,2003. Determinationofglasstransitiontemperatureandinsitustudyofthe plasticizingeffectofwaterbyinversegaschromatography.Pharm.Res.20(10), 1647–1654.

Tang,P.,Chan,H.,Choiou,H.,Ogawa,K.,Jones,M.D.,Adi,H.,Buckton,G.,2009. Characterisationandaerosolisationofmannitolparticlesproducedviaconfined liquidimpingingjets.Int.J.Pharm.367,51–57.

Traini,D.,Young,P.M.,Thielmann,F.,Acharya,M.,2008.Theinfluenceoflactose pseudopolymorphicformonsalbutamolsulfate–lactoseinteractionsinDPI formulations.DrugDev.Ind.Pharm.34(9),992–1001.

Ticehurst,M.D.,Rowe,R.C.,York,P.,1994.Determinationofthesurfacepropertiesof twobatchesofsalbutamolsulphatebyinversegaschromatography.Int.J. Pharm.111(3),241–249.

Thielmann,F.,Burnett,D.J.,Heng,J.Y.,2007.Determinationofthesurfaceenergy distributionsofdifferentprocessedlactose.DrugDev.Ind.Pharm.33(11), 1240–1253.

Tong,H.H.,Shekunov,B.Y.,York,P.,Chow,A.H.,2001.Characterizationoftwo polymorphsofsalmeterolxinafoatecrystallizedfromsupercriticalfluids. Pharm.Res.18(6),852–858.

Tong,H.H.,Shekunov,B.Y.,York,P.,Chow,A.H.,2006.Predictingtheaerosol performanceofdrypowderinhalationformulationsbyinterparticulate interactionanalysisusinginversegaschromatography.J.Pharm.Sci.95(1), 228–233.

Trowbridge,L.,Grimsey,I.,York,P.,1998.Influenceofmillingonthesurface propertiesofacetaminophen.Pharm.Sci.1,310.

Yamauchi,M.,Lee,E.-H.,Otte,A.,Byrn,S.R.,Carvajal,M.-T.,2011.Contrastingthe surfaceandbulkpropertiesofanhydrateanddehydratedhydratematerials. Cryst.GrowthDes.11(3),692–698.

York,P.,Ticehurst,M.D.,Osborn,J.C.,Roberts,R.J.,Rowe,R.C.,1998.Characterisation ofthesurfaceenergeticsofmilledDL-propranololhydrochlorideusinginverse gaschromatographyandmolecularmodelling.Int.J.Pharm.174(1),179–186.