© Robin Couture Matte, 2019

Digital Games and Negotiated Interaction

:

integrating Club Penguin Island into Two ESL Grade

6 Classes

Mémoire

Robin Couture Matte

Maîtrise en linguistique - didactique des langues - avec mémoire

Maître ès arts (M.A.)

Digital Games and Negotiated Interaction:

Integrating Club Penguin Island into Two ESL Grade 6

Classes

Mémoire

Robin Couture Matte

Sous la direction de :

ii

Résumé

Cette étude avait pour objectif d’explorer l’interaction entre de jeunes apprenants (11-12 ans) lors de tâches communicatives accomplies face à face et supportées par Club Penguin Island, un jeu de rôle en ligne massivement multijoueur (MMORPG). Les questions de recherche étaient triples: évaluer la présence d’épisodes de centration sur la forme (FFEs) lors des tâches communicatives accomplies avec Club Penguin Island et identifier leurs caractéristiques; évaluer l’impact de différents types de tâches sur la présence de FFEs; et examiner les attitudes des participants.

Ce projet de recherche a été réalisé auprès de 20 élèves de 6ième année en anglais intensif dans la province de Québec. Les participants ont exécuté une tâche de type «information gap», et deux tâches de type «reasoning gap» dont une incluant une composante écrite. Les tâches ont été réalisées en dyades et les enregistrements des interactions ont été transcrits et analysés pour identifier la présence de FFEs et leurs caractéristiques. Une analyse statistique fut utilisée pour évaluer l’impact du type de tâche sur la présence de FFEs, et un questionnaire a été administré pour examiner les attitudes des participants à la suite des tâches.

Les résultats révèlent que des FFEs ont été produits lors des tâches accomplies avec le MMORPG, que les participants ont pu négocier les interactions sans l’aide de l’instructeur et que la majorité des FFEs visaient des mots trouvés dans les tâches et le jeu. L’analyse statistique démontre l’influence du type de tâche, puisque davantage de FFEs ont été produits lors de la tâche de type «information gap» que l’une des tâches de type «reasoning gap». Le questionnaire sur les attitudes révèle qu’elles ont été positives. Les implications pédagogiques soulignent l’impact des MMORPGs pour l’acquisition des langues secondes et les conclusions ajoutent à la littérature limitée sur les interactions entre de jeunes apprenants.

iii

Abstract

The objective of the present study was to explore negotiated interaction involving young children (age 11-12) who carried out communicative tasks supported by Club Penguin Island, a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG). Unlike previous studies involving MMORPGs, the present study assessed the use of Club Penguin Island in the context of face-to-face interaction. More specifically, the research questions were three-fold: assess the presence focus-on-form episodes (FFEs) during tasks carried out with Club Penguin Island and identify their characteristics; evaluate the impact of task type on the presence of FFEs; and survey the attitudes of participants.

The research project was carried out with 20 Grade 6 intensive English as a second language (ESL) students in the province of Quebec. The participants carried out one information-gap task and two reasoning-gap tasks including one with a writing component. The tasks were carried out in dyads, and recordings were transcribed and analyzed to identify the presence of FFEs and their characteristics. A statistical analysis was used to assess the impact of task type on the presence of FFEs, and a questionnaire was administered to assess the attitudes of participants following the completion of all tasks.

Findings revealed that carrying out tasks with the MMORPG triggered FFEs, that participants were able to successfully negotiate interaction without the help of the instructor, and that most FFEs were focused on the meaning of vocabulary found in the tasks and game. The statistical analysis showed the influence of task type since more FFEs were produced during the information-gap task than one of the reasoning-gap tasks. The attitude questionnaire revealed positive attitudes, which was in line with previous research on digital games for language learning. Pedagogical implications point to the impact of MMORPGs for language learning and add to the scarce literature on negotiated interaction with young learners.

iv

Table of contents

Résumé ... ii

Abstract ... iii

Table of contents ... iv

List of tables ... vii

List of figures... viii

List of abbreviations/acronyms ... ix

Acknowledgements ... x

Introduction ... 1

Chapter 1: Statement of the problem ... 3

1.1 Research questions ... 5

1.2 Conclusion ... 6

Chapter 2: Theoretical framework ... 7

2.1 MMORPGs and virtual worlds ... 7

2.2 Negotiated interaction and focus-on-form episodes ... 8

2.3 Tasks ... 13

2.4 Choice of the interactionist perspective for the present study ... 15

2.5 Conclusion ... 18

Chapter 3: Review of the literature ... 19

3.1 Task-based interaction and focus on form within MMORPGs and virtual worlds ... 19

3.2 Negotiated interaction: Classroom research with adolescents and adults ... 26

3.3 Negotiated interaction with children ... 33

3.4 Conclusion ... 35

Chapter 4: Methodology ... 37

4.1 Context of the study ... 37

4.2 Participants ... 37

4.3 The research design ... 38

4.4 The game: Club Penguin Island ... 39

4.5 Tasks ... 40

4.6 Data collection instruments ... 42

4.7 Procedure ... 43

4.8 Analysis ... 44

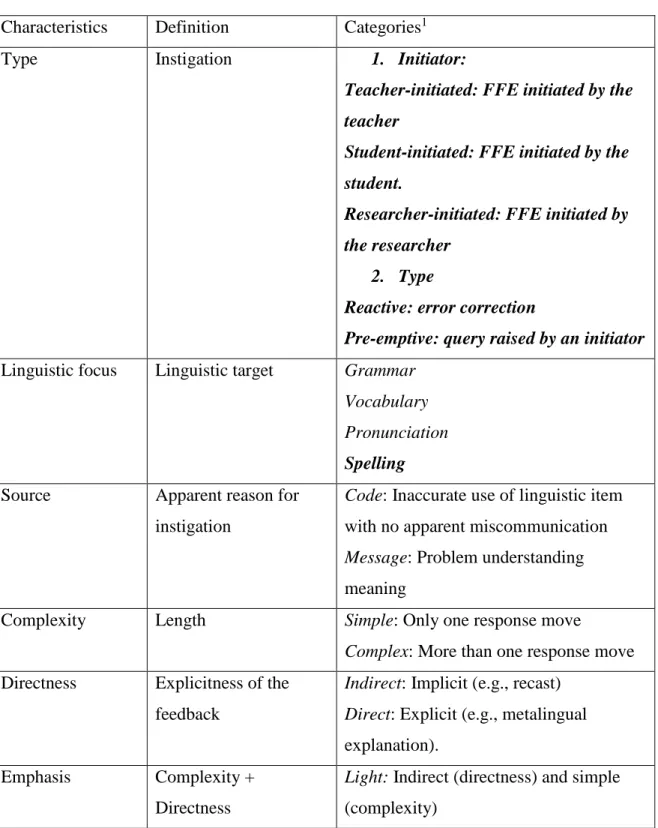

4.8.1 Modifications to the type characteristic ... 48

v

4.8.3 Modifications to the uptake and successful uptake characteristics ... 53

4.8.4 Other modifications ... 54

4.8.5 Statistical analyses ... 55

4.9 Conclusion ... 56

Chapter 5: Results ... 57

5.1 Question 1: FFEs and characteristics of FFEs ... 57

5.2 Question 2: Differences between tasks ... 60

5.3 Question 3: Attitudes ... 62

5.4 Conclusion ... 65

Chapter 6: Discussion ... 66

6.1 Question 1: FFEs and characteristics of FFEs ... 66

6.1.1 Number of FFEs ... 66

6.1.2 Type ... 67

6.1.3 Linguistic focus and source ... 68

6.1.4 Complexity, directness, emphasis and timing ... 69

6.1.5 Response ... 69

6.1.6 Uptake and successful uptake ... 71

6.2 Question 2: Differences between tasks ... 71

6.3 Question 3: Attitudes ... 72 6.4 Conclusion ... 72 Conclusion ... 74 Summary of findings ... 74 Limitations ... 75 Pedagogical implications ... 76

Areas for further research ... 76

Conclusion ... 77

References ... 78

Appendix A: Attitudes questionnaire ... 83

Appendix B: Task 1 ... 85

Appendix C: Task 2 ... 86

Appendix D: Task 3 ... 90

Appendix E: Transcription conventions ... 92

Appendix F: FFE characteristics between groups per task (Mann-Whitney U test) ... 93

Appendix G: Differences between FFEs categories (Mann-Whitney U Test) ... 96

vi

Appendix I: Elicited FFEs ... 102 Appendix J: Consent Forms ... 1

vii

List of tables

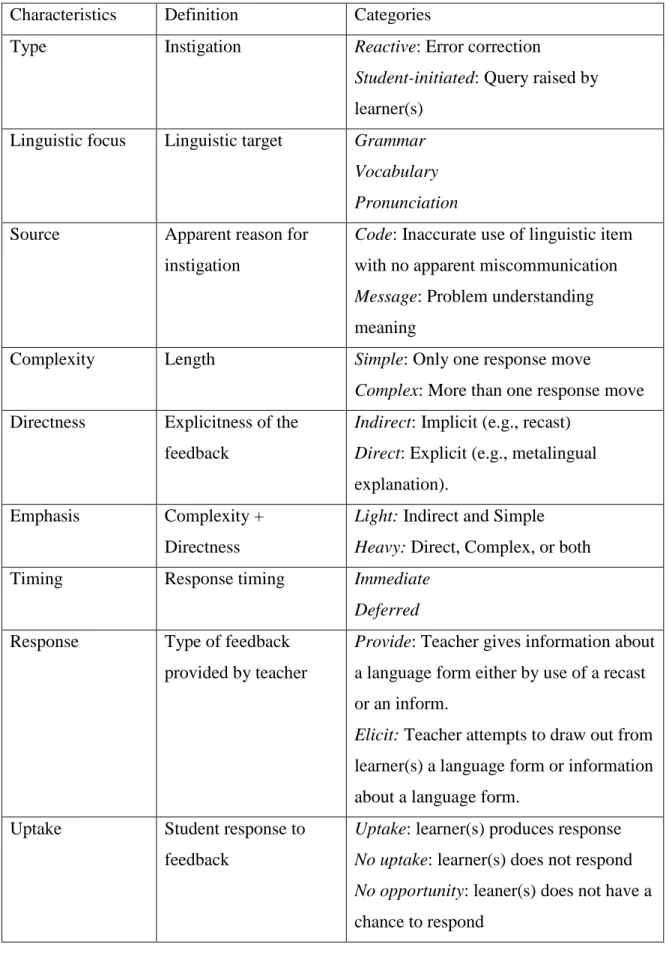

Table 2.1: Characteristics of FFEs from Loewen (2005) ... 12

Table 4.1: Schedule for the study. ... 43

Table 4.2: Research questions, data collection activities and analysis ... 45

Table 4.3: FFE characteristics adapted from Lowen (2005) ... 46

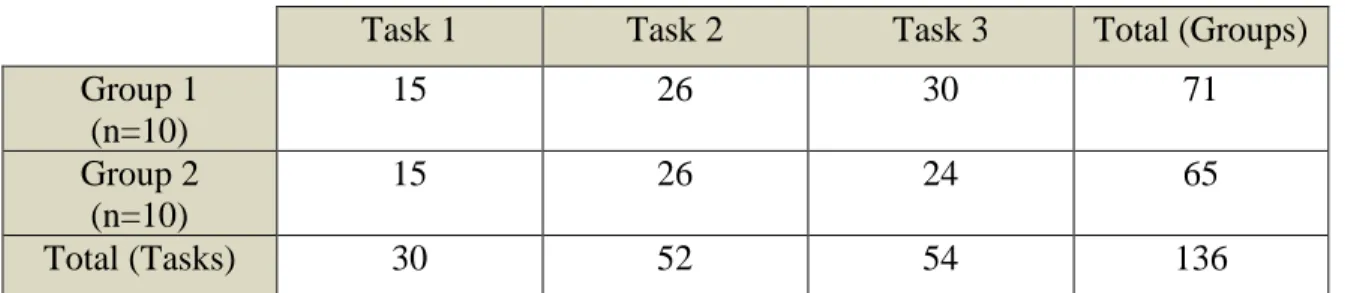

Table 5.1: Number of FFEs for combined groups per task ... 57

Table 5.2: Results of the Mann-Whitney U test for number of FFEs between groups per tasks ... 57

Table 5.3: Overview of the categories for each FFE characteristics ... 58

Table 5.4: Distribution of FFEs between tasks (both groups combined) ... 61

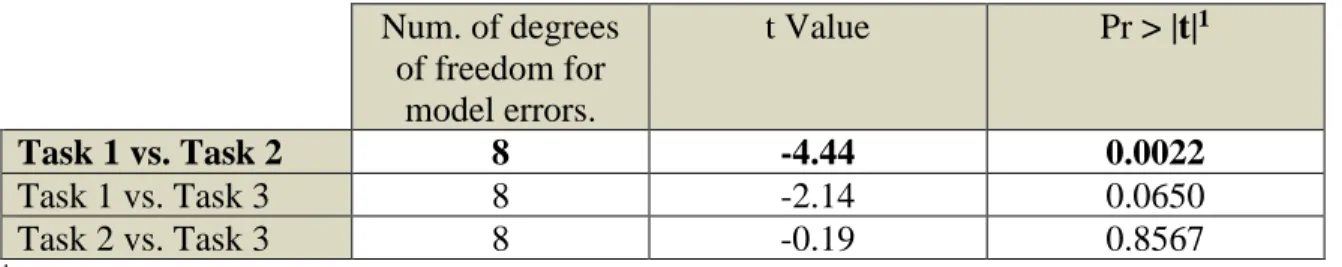

Table 5.5: Results of Bruner et al.’s procedure (2002) for task, group, and group*task as tested in number of FFEs ... 61

Table 5.6: Results of Bruner et al.’s procedure (2002) for significance between tasks ... 61

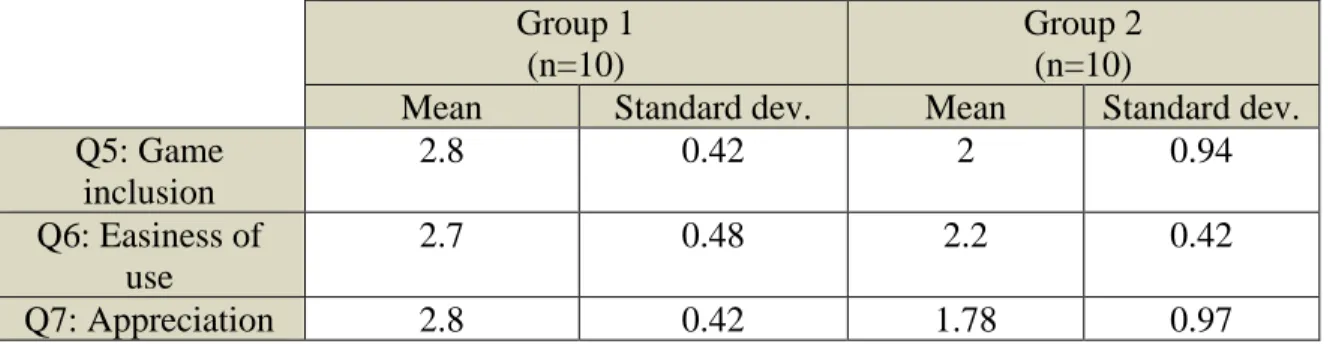

Table 5.7: Results of the questionnaire with regards to tasks per group ... 63

Table 5.8: Results of the questionnaire with regards to the game per group ... 63

Table 5.9: Recurring themes as to what participants liked and disliked about the game and the tasks ... 64

viii

List of figures

ix

List of abbreviations/acronyms

CEFR Common European Framework of Reference CEGEP Collège d’Enseignement Général et Professionnel

ESL English as a second language

FFE Focus-on-form episode

FoF Focus on form

ICT Information and communication technology

LRE Language-related episode

MMORPG Massively multiplayer online role-playing game

MSL Mandarin as a second language

NIFLAR Networked Interaction in Foreign Language Acquisition and Research

NNS Non-native speaker

NS Native speaker

SLA Second language acquisition

x

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I would like to thank God Almighty for giving me the opportunity and perseverance to undertake this project. His blessings made this achievement possible. In my journey as a Master’s student, I have found an irreplaceable mentor in my research director, Dr. Susan Parks. Her expertise and her encouragements proved invaluable. She has given me the opportunity to pursue my research and her guidance made sure I stayed on course throughout my graduate studies.

There are many people to whom I would like to express my gratitude. Among these are my parents who provided consistent encouragement and who were always present to support me in the most difficult moments. During my graduate studies, I also had the chance to meet John Coffie Teye, who became a close friend and whose assistance during my studies proved to be a blessing. Finally, I would like to thank all the professors who helped me acquire the necessary skills and who supported me for this project.

1

Introduction

Research studies on negotiated interaction in the second language classroom evolved in reaction to Krashen’s input hypothesis (1980, 1981, 1985) which suggested that acquisition was possible through comprehensible input. In the 1980s, researchers began to explore how comprehensible output (Swain, 1985) and interaction (Long, 1980, 1983) could be beneficial for second language acquisition (SLA) (Pica, 1994). As a result, one of the most important developments with regards to how negotiated interaction can be

systematically observed concerns the concept of negotiation of meaning. Negotiation of meaning involves what Long (1996) described as "interactional adjustments" triggered when a communication problem arises between two interlocutors while carrying out meaning-focused activities (also referred to as communication breakdowns). As a result of negotiation of meaning, learners of a second language have been found to internalize language. This has been found to occur when learners communicate among themselves or with a more proficient interlocutor such as the teacher (Long, 1996).

In the 1990s, Long (1996) proposed that while attempting to repair communication breakdowns, learners may also focus on linguistic features. Drawing on Schmidt’s work (1993) on the role of noticing in the acquisition of linguistic elements, Long (1996)

developed the idea of focus on form (FoF) which entails the noticing of linguistic elements during negotiation of meaning. From a research perspective, the specific moments during which focus on form occurs were labelled focus-on-form episodes (FFEs). Such episodes were found to be beneficial for the acquisition of linguistic elements (Alcón Soler & Garcia Mayo, 2008; Ellis, 2001a; Loewen, 2005; Loewen and Reissner, 2009). The

conceptualization of focus on form has led to an important body of research studies that explore when the noticing of linguistic features occurs, how it can be triggered, its characteristics and its outcomes with respect to language acquisition.

Drawing on the rich line of studies on focus on form, the objectives of the present study were to explore the presence of FFEs during communicative tasks carried out by elementary school ESL students and supported by a digital game. Accordingly, the present study is divided into 6 chapters. Chapter 1 will present the statement of the problem and the

2

research questions. Subsequent chapters will deal with the following aspects of the present study: Chapter 2 – Theoretical framework, Chapter 3 – Review of the literature, Chapter 4 – Methodology, Chapter 5 – Results, Chapter 6 – Discussion. Finally, the conclusions of the present study will be presented.

3

Chapter 1: Statement of the problem

Most studies that have explored negotiated interaction have focused on adults (Ellis et al., 2001a; Ellis et al., 2001b; Loewen, 2003; Loewen, 2004; Williams, 2001). As pointed out by Gagné and Parks (2013), few studies which have investigated negotiated interaction have involved young learners. In this regard, only three studies (Gagné & Parks, 2013; Oliver, 1998, 2013) have systematically explored negotiated interaction with second language students under the age of 12 when working with peers. From an interactionist perspective, Oliver (1998, 2013) assessed negotiation of meaning between native and non-native ESL learners (aged 8-13) working in pairs. Whereas Oliver’s studies were carried out in an experimental setting, a study by Gagné and Parks focused on children in a

classroom setting from a sociocultural approach. Indeed, Gagné and Parks (2013) assessed how Grade 6 non-native students (aged 11-12) used scaffolding during cooperative learning activities. Their research, while assessing communication breakdowns, was mainly focused on how students received help from the members of the class (e.g. peers and the teacher) when dealing with linguistic problems during negotiation of meaning. The studies by Gagné and Parks (2013) and Oliver (1998, 2013) have come to the promising conclusion that young learners in the school system can successfully negotiate interaction when working with peers. Nevertheless, their studies also underscore the necessity for more research studies on negotiated interaction with young children.

One of the areas of interest with respect to negotiation of meaning and FoF is task type. Indeed, it is with the use of meaning-focused tasks that the concepts of negotiation of meaning and focus on form were found to be suitable for language acquisition (Ellis, 2003; Long, 2015). In view of studying and promoting negotiated interaction and language acquisition, Ellis (2017) explains that researchers in the field of task-based language teaching (TBLT) have developed different classifications with respect to how tasks can be designed. More importantly for the present study, this development has led to the

assessment of how different types of tasks can influence the production of negotiated interaction and FFEs (Ellis, 2017). To my knowledge, no research study has assessed if different types of tasks influence the number of FFEs produced by children when carrying out communicative tasks in pairs in the classroom.

4

The context in which early studies on negotiated interaction were carried out mainly involved the use of what one may consider "traditional" support for learning, such as activities printed out on paper or carried out with textbooks. In more recent years researchers and second language teachers have started to explore how information and communication technologies (ICTs) can promote negotiated interaction and enhance learning in general. In this respect, second language teachers are now integrating electronic devices, applications and games to support their teaching. In parallel, researchers have started to assess how negotiation of meaning and focus on form can occur and be triggered in the context of ICT-supported language teaching. Chun (2016), in her review of studies which have explored the use of technologies for SLA, reports that an increasing number of researchers have explored negotiated interaction as it occurs through different means of communication such as tandem learning or text-based online communication. One of the most recent developments with regards to ICTs and negotiated interaction is the use of online digital games for language learning. One of the advantages that has been associated with online digital games is the positive attitudes they trigger (Canto et al., 2013; Jauregi et al., 2011; Lan, 2014; Lan et al., 2016; Peterson, 2010, 2016; Reinders and Wattana, 2011, 2014; Suh et la., 2010). To my knowledge, only one study (Suh et al., 2010) has explored the use of digital games with young learners in the context of negotiated interaction.

To explore the gaps as presented in the above review, the present study assessed the presence of FFEs and participant attitudes during communicative tasks involving an online digital game (Club Penguin Island) carried out by Quebec Grade 6 students enrolled in an ESL intensive program. The game selected for the present study was Club Penguin Island, a massively multiplayer role-playing game (MMORPG) designed for a young audience (age 5-12). MMORPGs are commercial games in which players control an avatar and move freely about a virtual environment while completing quests which are generally part of a storyline. In the case of Club Penguin Island, players embody a penguin, move around an island and complete different tasks related to the survival of the island. The use of such games for language learning was advocated by Peterson (2010, 2016) and explored by a few researchers (Canto et al., 2013; Jauregi et al., 2011; Lan, 2014; Lan et al., 2016;

5

Peterson, 2010, 2016; Reinders and Wattana, 2011, 2014). This type of game also generally involves online communication between players through chat or audio communication (microphone). Most of the reviewed studies thus involved online gameplay in which adult learners communicated through chat or through a microphone either as a team or with other players online.

It is important to note that the approach selected in the present study differs from the literature on MMORPGs. Indeed, Club Penguin Island was used as a support for tasks carried out face-to-face by students who were working in pairs. Consequently, online communication during tasks was extremely rare and the game was mainly adopted for its rich virtual environment. Indeed, all tasks involved learners working in pairs who were seated side by side and discussed their tasks while playing the game on an electronic tablet. The reasons for using the game in this manner and disregarding online communication mainly concern the technological challenges proper to the use of this type of game which were expressed by previous researchers (e.g. Chan, 2010; Lan, 2014, Reinders & Wattana, 2014). These reasons will be discussed in Chapter 3. Thus, the present study contributes to the field of language learning and technologies for it assessed a novel perspective with respect to the use of a MMORPG with children in the context of classroom interaction.

1.1 Research questions

As discussed above, the present study aimed at assessing the presence of FFEs during communicative tasks involving a MMORPG (Club Penguin Island) carried out by Quebec Grade 6 students enrolled in an ESL intensive program. More specifically, the questions addressed in this study are the following:

1. Does the use of communicative tasks involving a MMORPG engaged in by Quebec Grade 6 ESL intensive students trigger FFEs? If so, what are the characteristics of FFEs?

2. Does task type influence the number and characteristics of FFEs triggered by the use of communicative tasks involving a MMORPG engaged in by Quebec Grade 6 ESL intensive students?

6

3. What are the attitudes of Quebec Grade 6 ESL intensive students towards the use of communicative tasks involving a MMORPG?

1.2 Conclusion

This section addressed the objectives and the rationale behind the present study. It was shown that more studies were needed in the area of FoF when used in the context of MMORPGS with children. Accordingly, three research questions were proposed. The following chapter – Chapter 2 – will present the theoretical framework for carrying out tasks in the context of a MMORPG with children.

7

Chapter 2: Theoretical framework

As explained in the introduction, the present study deals with MMORPGs, and, as such, one must first define concepts related to this type of game. Following this first set of definitions, the concepts of negotiated interaction and focus on form will be explained, followed by task type, a key element for the present study. Finally, since the present study involves social interaction, the choice between using an interactionist perspective as the theoretical framework rather than socio-cultural theory will be explained.

2.1 MMORPGs and virtual worlds

According to Peterson (2010), massively multiplayer role-playing games (MMORPGs) can be used as “arenas” for second language acquisition. To define MMORPGs, Peterson (2010) identifies the importance of certain key characteristics. Amongst those characteristics, one can find the use of avatars, an authentic environment (albeit a virtual), teamwork and the use of authentic tasks (usually known as “quests”). One can also attribute the same characteristics to virtual worlds, which are often seen as a similar type of game. Indeed, Perron (2012) includes virtual worlds within her definition of MMORPGs. The difference between both activities (MMORPGs and virtual worlds) thus lies in the narrative experience which is automatically included within a MMORPG and possible, but not necessarily present within a virtual world. The narrative experience within MMORPGs and virtual worlds consists of tasks (generally not communicative) that are embedded within a storyline for which the avatar is rewarded. For example, the avatar could be asked to retrieve a legendary object from a specific area and carry it to another character in the virtual world in exchange of virtual money which can be used to buy virtual clothes or virtual furniture for the avatar’s house. However, as concluded by Reinders and Wattana’s (2011, 2014), the narrative experience offered by MMORPGs is generally not suited for language learning. They explain that the language included in the narrative experience is often very limited, providing few opportunities for negotiation. As such, when preparing language learning tasks for these types of activities, language teachers most commonly ignore the narrative experience present in a MMORPG and only consider the authentic environment and avatars. By doing so, they ignore what makes MMORPGs differ from virtual worlds and

8

use MMORPGs as virtual worlds. Thus, I will use the two terms interchangeably for they describe a very similar learning/gaming environment and tackle the same issues when applied to language learning.

With regards to the advantages of MMORPGs and virtual worlds, Peterson (2016) found that the reasons expressed by different authors behind the use of these types of online games tie in with two perspectives: a cognitive perspective and a sociocultural perspective. With regards to the first perspective, he explains that online communication and task accomplishment within MMORPGs and virtual worlds can lower anxiety and affective barriers, provide rich input and promote negotiation for meaning between players. With regards to the second perspective, he emphasizes that community-based and peer-based social interactions found within MMORPGs and virtual worlds can be ideal for language learning and “learning socialization” (Peterson, 2016). From Peterson’s review of studies on the use of MMORPGs, the ideas of negotiation of meaning, and, in turn, a focus on form, were found to be of high interest for this research. Consequently, both will be defined.

2.2 Negotiated interaction and focus-on-form episodes

The concept of “negotiation for meaning” emerged in the 1980s in relation to Krashen’s input hypothesis (1980, 1981, 1985). As explained by Krashen, this hypothesis suggests that second language acquisition (SLA) is possible through comprehensible input as generated, for example, by a teacher in a language classroom. He based his theory on earlier observations with children learning their first language and he explains that learners acquire a language by understanding messages containing elements present in the next stage of the learner’s language development (also presented as the i+1). Thus, he concluded that “the major function of the second language classroom is to provide intake (comprehensible input) for acquisition” (Krashen 1981, p.101). Accordingly, he proposed that activities in the language classroom should be created to aim for i+1. In reaction to Krashen, Long (1980, 1983) started to explore interaction and more precisely interaction between native speakers, and between native speakers and non-native speakers. He concluded that interaction between native speakers and non-native speakers triggered interaction modifications to cope with communication problems created by the non-native speaker’s lower level of proficiency.

9

From this conclusion, Long (1983), who considered the importance given to comprehensible input in SLA, proposed the concept of “negotiation of comprehensible input” in which comprehensible input is achieved when interlocutors adapt their speech to comprehend each other, a concept he deemed promising for the language classroom. Swain (1985) also played an important role in refining the concept by introducing the notion of comprehensible output. Indeed, as she explains in her study of French immersion programs in Canada, the idea of comprehensible input and Krashen’s take on it defined output simply as a generator of comprehensible input. As shown by her study (1985) of French immersion students, even with large quantities of comprehensible input the latter were not able to attain the levels of linguistic competency of native French-speaking children of the same age. She thus proposed the idea of “negotiating meaning” as a term that encompasses all three concepts (comprehensible input, interactional adjustments and comprehensible output) and as a key factor in second language acquisition. It is thus from Krashen’s studies on comprehensible input, Long’s studies on interaction and Swain’s studies on comprehensible output that what would be known as the concept of “negotiation for meaning” emerged. While evolving through the years, the concept led many researchers to explore it using different approaches and contexts from the 1980s and into the 1990s. Pica’s (1994) review of early studies on negotiation of meaning as applied to language learning is a testament to what she presents as a “rich line of research” these concepts initiated. In a later version, Long (1996) defined negotiation for meaning as “interactional adjustments” triggered when interlocutors encounter communication problems which help weaker learners both notice where their linguistic gaps lie and help adjust their language (comprehensible output) to reach the target level of language to resume communication. He argues that this interaction arrives at the right moment to help the learner internalize the attention to form prompted by the communication problem and thus, help language acquisition.

The idea of FoF thus emerged in the 1990s from the concept of negotiation of meaning. As explained, the importance of attention to form was already present in later definitions of negotiation of meaning, but early attempts at defining the concept did not automatically include focus on form in negotiation for meaning. Indeed, when tackling the idea, Long (1991) presented focus on form alongside a focus on forms (outright teaching of

10

grammar) and a focus on meaning. Nonetheless, one of his first innovations was to include the idea of noticing to the concept and to suggest that a focus on form may happen when it is unplanned by the teacher during a meaning-focused activity. The current definition of FoF is thus intimately linked with this idea of noticing that was brought from the field of psychology to the field of SLA by Schmidt (1993) who defined it as the incidental recognition of linguistic elements (for example a rule) within the target language which can lead to the understanding of the said element and its acquisition. Thus, Long (1996) later redefined the concept of FoF as the noticing of linguistic features by students during negotiation of meaning within the context of a communicative task. This attention to form is expected to be beneficial for the learner’s acquisition. Indeed, noticing gaps in the interaction within the context of a communication problem encourages the learner to notice his/her own linguistic gaps and to produce a higher level of language to ensure communication, which in turn, may result in internalization of the noticed linguistic features (Schmidt, 1990, 1993). As such, while a focus on form can occur during negotiation of meaning, it is also possible that it does not occur, leaving the linguistic feature unnoticed. Nonetheless, negotiation of meaning and focus on form have evolved simultaneously in research for many years. Indeed, Peterson (2010), when presenting his rationale for the use of MMORPGs in language learning, argues that both concepts can be used to advocate the use of this type of online activity in the language classroom.

It is finally important to distinguish between two different types of FoF. Indeed, planned FoF involves a presentation by the teacher before a communicative task or activities planned in such a way as to focus on specific aspects of the language, while incidental FoF briefly occurs naturally during a communicative task because of an error or a gap in the students’ knowledge (Ellis, Basturkmen & Loewen, 2001a; Kim & Nassaji, 2017; Loewen & Reissner, 2009). Both concepts are generally considered by researchers as focus on form as both are still part of a communicative task but debate as to which of the two is most efficient for language teaching is present in the literature (Ellis et al., 2001a; Long & Robinson, 2009). Nonetheless, such instances of a brief occurrence during communication (whether planned or not) are referred to as a FoF episode (FFE). For the present study, in

11

light of the tasks used in the context of the classroom, only incidental FFEs will be analyzed and, as such, its possible characteristics will be explained in the following sections.

Negotiation of meaning and focus on form have both been subject to different methods of measure and analysis. When analyzing episodes of negotiation of meaning, Varonis and Gass (1985) were the first to propose a model. Their model included the trigger and the resolution which was further divided into three subsections (the indicator, the response and the reaction to the response). In more recent years, the FFE was defined by Ellis et al. (2001a) as the “point ... where the attention to linguistic form start[s] to the point where it end[s]. The endpoint occur[s] when either a topic change[s] back to a focus on meaning or, sometimes, to a focus on a different linguistic form” (p.294). Ellis et al. (2001a) also used the term of “uptake” to indicate the third section of the episode (referred to as the reaction to the response by Varonis & Gass, 1985). The current model for the analysis of FFEs includes three components: the trigger, the response and the uptake. First, the trigger is best described as the noticing of a problem within the interaction. Second, the response includes a discussion on the error and the possible finding of an answer (erroneous or not). Finally, the uptake occurs when one of the participants subsequently uses the form correctly or not. Although highly desirable, an episode of FoF does not need to include the third move (uptake) to be successful, and the absence of uptake does not necessarily mean that acquisition was not present (Ellis et al., 2001a). In sum, only the trigger and the response are necessary to qualify as a FFE. In addition to the three-move model for FFE analysis, Loewen (2005), drawing on Ellis, Loewen and Basturkmen (1999), also proposed that FFEs may be further analyzed in accordance with different characteristics (Table 2.1). The characteristics he presented were developed for assessing classroom negotiated interaction from the teacher’s perspective. Other researchers such as Shekary and Tahririan (2006) and Loewen and Reissner (2009) subsequently adapted this analysis for studies involving online interaction. However, the present study uses an online tool in the context of face-to-face interaction and not online interaction. As such, Loewen’s model was adopted and further adapted for the present study. More information on the modifications made to Loewen’s model will be explained in the methodology section.

12

Table 2.1: Characteristics of FFEs from Loewen (2005)

Characteristics Definition Categories

Type Instigation Reactive: Error correction

Student-initiated: Query raised by learner(s)

Linguistic focus Linguistic target Grammar Vocabulary Pronunciation

Source Apparent reason for

instigation

Code: Inaccurate use of linguistic item with no apparent miscommunication Message: Problem understanding meaning

Complexity Length Simple: Only one response move

Complex: More than one response move Directness Explicitness of the

feedback

Indirect: Implicit (e.g., recast) Direct: Explicit (e.g., metalingual explanation).

Emphasis Complexity +

Directness

Light: Indirect and Simple Heavy: Direct, Complex, or both

Timing Response timing Immediate

Deferred Response Type of feedback

provided by teacher

Provide: Teacher gives information about a language form either by use of a recast or an inform.

Elicit: Teacher attempts to draw out from learner(s) a language form or information about a language form.

Uptake Student response to feedback

Uptake: learner(s) produces response No uptake: learner(s) does not respond No opportunity: leaner(s) does not have a chance to respond

13 Successful uptake Quality of student

response

Successful uptake: learner(s) incorporates linguistic information into production Unsuccessful uptake: learner(s) does not incorporate linguistic information into production

2.3 Tasks

In addition to the important concept of FoF and FFEs, the idea of tasks and more specifically task types is central to the present study. Ellis (2003), Long (2015) and Van der Branden (2016) all agree that there is no clear consensus as to the exact definition of task. In a general manner, Van der Branden (2016) explains that many definitions of tasks have been used in the literature but that they all share a “common core” (p. 241). Indeed, he explains that “a task is a goal-oriented activity that people undertake and that involves the meaningful use of language” (Van der Branden, 2016, p. 241). Long (2015), one of the forebearers of the approach, defines tasks as “the real-world activities people think of when planning, conducting, or recalling their day” (Long, 2015, p. 6). As such what Long labels as “pedagogic tasks”, or tasks accomplished in the classroom by students and teachers, are problem-solving activities prepared with a real-life perspective in mind and presented in a progressive manner within a syllabus. He presents them as a unit of analysis which is used in TBLT to design syllabuses, implement them and assess their success in language learning with students. He thus creates a clear distinction between TBLT’s definition of task and other activities which are often labelled as tasks, but do not follow the aforementioned principles. For example, he often contrasts TBLT tasks to grammar-based activities labelled tasks within commercially available textbooks which are more linguistically driven than based on real-life problems.

In a recent article, Ellis (2017) argues that defining tasks in terms of their real-life nature is flawed for any task will become "pedagogic" when used in a classroom context. He thus proposed that "pedagogic" tasks differ from “real-world” tasks in that they "lack situational authenticity but aim(s) at interactional authenticity" (p. 509). Pedagogic tasks thus

14

do not try to re-enact real-life situations but are created mainly to create interaction that can be used outside of the classroom. Taking into consideration the entertaining nature of MMORPGs, it would be difficult to create tasks which are designed to mimic "real-world" contexts such as proposed by Long (2015). The tasks in the context of the present study were thus created from a perspective much closer to Ellis’ definition of "pedagogic" task (2017) for they were created to achieve interactional authenticity as supported by the game. It is thus from Ellis’ definition of pedagogical tasks, as defined within TBLT, that the present study approached the use of MMORPGs to support the creation and use of communicative tasks.

Since the emergence of the idea of a task-based approach to second language learning (TBLT), many types of syllabuses and characteristics have been used and evaluated by researchers to classify how tasks are planned and carried out. Among the many, and often dichotomic, task characteristics (such as open/closed or convergent vs. divergent tasks) and task-based syllabuses (such as the process and hybrid syllabuses) is the idea of task type which is central to the present research study (Ellis, 2003; Long, 2015). One of the most referred-to classifications for task type includes three types of tasks: information gap, reasoning gap and opinion gap (Ellis, 2003; Long, 2015). Information-gap tasks are tasks where information is missing between participants which leads to a sharing of the missing information. One of the most common representations of such types of tasks are jigsaw activities, such as the sharing of different clues to find the answer to a puzzle. Reasoning-gap tasks involve the use of clues or conditions within a context (usually provided by the instructor) which allows the participants to create new pieces of information which, in turn, makes the completion of the task possible. Opinion-gap tasks require the participants to share their personal meanings or preferences to given information (Long, 2015). As discussed by Ellis (2003) and Long (2015), opinion-gap tasks, which are considered “open” tasks (tasks which do not allow for a finite number of solutions) were found the least successful for negotiation of meaning, while reasoning-gap tasks and information-gap tasks yielded the best results. Indeed, as explained by Ellis (2003), opinion-gap, or open-ended tasks are perhaps too unstable for they do not provide a clear outcome for the participants. Drawing on Ellis’ (2003) and Long’s (2015) conclusions, only information-gap and reasoning-gap tasks were evaluated in the present study.

15

Finally, one must note that in studies related to virtual worlds, “tasks” can convey a different meaning. Indeed, they are activities which involve actions performed by the avatar and aimed at accomplishing certain objectives (e.g. finding an object and bringing it back to a character in the game or solving a puzzle). For the present study, it is important to note that “tasks” was used to refer to the activities prepared by the researcher to be used with the MMORPG, and not the activities already present in this type of game.

2.4 Choice of the interactionist perspective for the present study

Up to this point, the concepts of FoF and FFEs, which are part of the terminology proper to an interactionist (also called cognitive) approach to language learning, have been explored. Yet, one can easily argue that a socio-cultural approach for the analysis of interaction within the context of MMORPGs and virtual worlds could have been used for the present study. Indeed, when elaborating on the use of MMORPGs in the classroom, Peterson (2010, 2011, 2016) presents arguments from an interactionist and a socio-cultural perspective. However, we chose to approach the present study from an interactionist perspective. Consequently, the similarities and differences between the two perspectives and their units of analysis will be presented to ultimately justify my choice for the present study.

As explained by Mondada and Doehler (2000), both perspectives view and study language learning as a product of social activity and more precisely, social interaction. Consequently, tasks in the language classroom are at the root of language learning and explaining why learning is occurring during interaction is the main goal for both perspectives. The broader spectrum of such beneficial interaction is often referred to as scaffolding, which is a term that was defined by Wood, Bruner and Ross (1976) as the “process that enables a child or novice to solve a problem, carry out a task or achieve a goal which would be beyond his unassisted efforts” (p. 90). Scaffolding includes a focus on adapting language to make tasks feasible, but also includes the controlling of factors such as getting the learner interested in the task and redirecting the learner when the learning objective is no longer being pursued (Wood et al., 1976). In sum, scaffolding is used by the teacher to make sure that the task can lead to a successful outcome.

16

However, both perspectives’ views on how to reach this goal and the tools they use to study it differ. Indeed, on the one hand, an interactionist perspective to language learning proposes to study the conditions and processes which lead to learning within interactional discourse. For example, conditions such as task type or the roles interlocutors take during discourse are often seen as important factors. However, an interactionist approach to language learning often limits its analysis to crucial moments during interaction (e.g. FFEs), without going beyond interaction and immediate conditions. On the other hand, a socio-cultural approach to the study of language learning looks beyond discourse and considers the socio-historical nature of interaction. While it does study discourse, crucial moments for learning (named language-related episodes) and the processes which lead to learning, it also considers contextual elements such as motivation and relations between participants, which brings the analysis further. This view of language learning also ties in with the concept of tasks. Indeed, as explained by Mondada and Doehler (2004), while an interactionist approach to language learning may study tasks and their characteristics as one of the conditions leading to learning, a socio-cultural approach distinguishes between tasks and activities. From this perspective, tasks are referred to as instructions provided by a teacher, while activities encompass a larger spectrum of factors (such as motivation and resources available to students) which make the same task a different activity for each student. A good example of the difference between the two concepts (task vs. activity) can be seen in Parks’ study (2000) of three CEGEP (college level) students in the province of Quebec, Canada, where the same task presented by a single instructor led to radically different activities and outcomes for each student. One can thus see how the two perspectives (interactionist vs. socio-cultural), while tackling the same objectives and very similar concepts, do not go to the same lengths to explain language learning from interaction. On the one hand, the interactionist perspectives views language learning as a series of conditions and processes, restricted to certain parts of interactional discourse between students and teachers; and on the other hand, the cultural perspective analyses a similar series of conditions and processes to which socio-historical factors are added. This difference led Mondada and Doehler (2004) to present the interactionist approach to language learning as weak, compared to a strong socio-cultural approach to language learning.

17

This distinction in perspectives also translates into differences in approaches to evaluating and analyzing language learning in the classroom. Indeed, since both perspectives still approach social interaction as the main factor leading to language learning, it is understandable that researchers from both perspectives use units of analysis that are very similar. One can easily associate the use of focus-on-form episodes, as presented earlier, within an interactionist perspective and LREs (language-related episodes) within a socio-cultural perspective. While focus-on-form episodes have already been defined in the previous subsection, LREs, for all practical purposes, share the same definition, but also include the idea of self-correction. The term was first coined by Swain and Lapkin (1995, 1998) in their studies with French as a second language students. They defined it as follows: “An LRE episode is defined as any part of a dialogue where the students talk about the language they are producing, question their language use, or correct themselves” (Swain & Lapkin, 1998, p. 326). Both terms (focus-on-form episodes and LREs) are often used interchangeably without much consideration for the perspectives they represent. For example, two of the studies reviewed for the present study (Williams, 2001; Shekary & Tahririan, 2006) use both terms interchangeably. Smith (2005) acknowledges this interchangeability directly in his study of task-based computer-mediated acquisition when he states that the “SLA literature has also referred to this concept [FFEs] as a language-related episode” (p. 38).

One may thus legitimately ask why the use of MMORPGs and virtual worlds in the classroom was not approached from a socio-cultural perspective in the present study. Indeed, as explained earlier, a socio-cultural perspective includes much of what the interactionist perspective has to offer and adds a socio-historical dimension to the study of social interaction. More specifically, however, for the present study, I decided to focus on the analysis of FFEs within an interactionist perspective for both comparative and technical reasons. First, the use of a framework such as that developed by Loewen (2005) provides for a more fine-grained analysis of various aspects relevant to focus on form. As well, using such a framework for analysis facilitates comparisons with other studies within an interactionist perspective and the results thus contribute to a very important line of research in the field of SLA. Second, the socio-historical perspective included in a socio-cultural approach to language learning involves a more complex set of data collection and analysis

18

(often including interviews with participants and more elaborate questionnaires, e.g. Gagné & Parks, 2013). Since the present study which involved the use of a MMORPG in a classroom context was in itself innovative and exploratory, it was decided to put the emphasis on one important aspect of language learning, the role of FFEs. As will be explained in the methodology section, teachers had to accommodate the researcher and the equipment for recording the interaction of students during group work into their busy schedules. Adding interviews and more elaborate data collection instruments would have proved difficult in those conditions.

2.5 Conclusion

Three main concepts were discussed in this chapter. The first, pertaining to MMORPGs and virtual worlds, provided important definitions regarding this type of online activity, as well as arguments in favor of using them for language learning. The second, pertaining to negotiated interaction and focus-on-form episodes presented a historical review, as well as a description of the main unit of analysis for the present study. It was discussed that FFEs were an appropriate unit for analyzing classroom-based interaction. The third concept discussed was with respect to tasks and task type. This section was important for it defined how tasks and task types were approached in this study. In this chapter, I also clarified my choice of the interactionist perspective as the theoretical framework for the present study. The next chapter will provide a review of pertinent studies for the present study.

19

Chapter 3: Review of the literature

This section will review pertinent literature for the present study. The first section will deal with studies that have explored the role of task-based interaction and FoF within MMORPGs and virtual worlds. The second section will provide an overview of classroom studies on negotiated interaction with adolescents and adults. The third section will review classroom research on negotiated interaction with children.

3.1 Task-based interaction and focus on form within MMORPGs and virtual worlds

Since the 1980s, much attention has been focused on the area of interaction, negotiation of meaning and subsequently focus on form (Alcón Soler & Garcia Mayo, 2008; Ellis et al., 2001a; Ellis et al., 2001b; Loewen, 2003, 2004, 2005; Williams, 2001). However, research conducted in this area with MMORPGs and virtual worlds is recent and scarce. Peterson (2010) was one of the first studies to convey the idea that MMORPGs can be used as arenas for language learning and provide meaningful interaction between players online. In his review article, which considers different studies that have assessed the possible roles of MMORPGs for language learning, he explains that many communication problems which will trigger negotiation of meaning can occur within this type of game. Furthermore, he indicates that this type of game fits in with the concept of FoF. Indeed, he provides a list of advantages that each game design feature can provide to the approach. In this list (Peterson, 2010), he proposes that real-time text and voice chat, challenging themes and goal-based interaction, and the use of personal avatars are the design features that tie in with the concept of FoF. However, as he states in his review, more empirical evidence is needed to confirm the positive outcomes of such features. He concludes that studies on MMORPGs are exploratory in nature and limited. He thus suggests the importance of further research on the subject.

Elsewhere, Jauregi et al. (2011) reported on an exploratory study within the Networked Interaction in Foreign Language Acquisition and Research project (NIFLAR) which had the goal of assessing the feasibility of designing communicative tasks within a virtual world (Second Life). As such, they were the first to provide a task framework for

20

virtual worlds. They integrated many communicative principles such as rich input, FoF and negotiation of meaning to design a grid to be used when creating learning tasks for virtual worlds. In the same research study, they conducted a pilot study to confirm that their rationale and task design grid could be used successfully. To do so, they used their grid to design four tasks which they tested with two learners (university students) and two experts (native speakers) within the online world called Second Life. They assessed the feasibility and pertinence of their task design grids within the virtual world by using interaction recordings, questionnaires with open-ended and Likert-scale questions, and informal interviews with the participants. The researchers analyzed the results to identify the kind of interactions elicited, the advantages of the virtual worlds exploited by the participants and the role of anonymity.

The results of Jauregi et al’s study (2011) confirmed that communicative task principles can be applied to online multiplayer games successfully. Their findings on interaction also revealed that task focus (e.g., exploratory or discussion based) influenced the interactions. Indeed, exploratory tasks (tasks during which the participants had to explore and identify elements within the world) were characterized by long periods of silence while more discussion-based tasks (e.g. discussions about interests) triggered more extensive interaction. Furthermore, the results of interviews and interaction analysis show that tasks carried out within the virtual world prompted episodes of FoF. Unfortunately, the authors provided little evidence of these occurrences for they were only a part of a larger attempt at demonstrating the feasibility of tasks. Thus, one can question the empirical weight of one pilot study which was conducted with two learners and two experts.

Subsequently, in her study of English as a lingua franca in virtual worlds, Liang (2012) also mentioned incidental FoF as part of her analysis. Her study was conducted with twenty university students enrolled in an English program who individually accomplished one task consisting of two conversations within Second Life and completed related activities outside of the virtual world (e.g written essays of online experiences). Her analysis (review of essays, analyses of written conversations and results of a survey) revealed that students who used English as a lingua franca in the virtual world adopted important semiotic and discourse strategies (e.g. the use of emoticons or shifting topics to discuss elements present

21

in the game) to communicate with native speakers who were players of the game. Also, of interest in the present study, she found that students achieved communication partly through focus on linguistic errors and corrections, most notably in regard to chat, which was preferred over real-time audio communication by many students. However, her study does not focus on the analysis of incidental FoF episodes and only states that focus on linguistic form and error correction is one of the communication strategies the students used online. Furthermore, she does not provide extensive and systematic evidence of the presence of incidental FoF in a virtual world while accomplishing tasks. Therefore, further exploration is necessary.

In a subsequent study, Canto, Jauregi and Van den Bergh (2013) assessed the added value of virtual worlds within the NIFLAR (Networked Interaction in Foreign Language Acquisition and Research) project. In their research, they evaluated the impact of cross-cultural interaction within tasks in Second Life. To do so, 50 university students (36 learners of Spanish as second language, and 14 native-speaking Spanish student teachers) carried out five tasks that were adapted for a classroom, the virtual world and a computer-mediated (Skype) context. The tasks included the following: (1) visiting apartments, exchanging cultural and personal information and choosing an activity (e.g. going to the movie theater); (2) talking about and planning holidays; (3) role-playing according to short scripts; (4) impersonating characters and experiencing reactions to others; and (5) a cultural contest composed of television-game-style questions. Unfortunately, since the tasks were adapted from the unit used in the course in which the participants were enrolled, they were not classified according to task type or any other feature of TBLT. The participants carried out the five tasks and had to complete a Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) oral competency pretest and post-test, as well as a questionnaire on their attitudes. In the online environments (Second Life and Skype), tasks were carried out by the learners of Spanish with the native-speaking student teachers. Tasks in the classroom context were carried out by the learners without the input of the student teachers.

Following the analysis of oral pretests and post-tests (based on the CEFR standards) and surveys about the participant experiences, Canto et al. (2013) concluded that the tasks could be used in all three environments and that all participants increased their oral

22

competency as shown by their scores on the CEFR oral competency test. They also concluded that using communicative tasks in the online environments (virtual worlds and computer mediated) provided added value for motivation, interaction and cross-cultural communication. In addition, their findings indicate that the experimental groups (Second Life and computer mediated) were advantaged and significantly enhanced their oral competency more than the control group but that the difference between both experimental groups was not significant. However, considering that the experimental groups, in contrast with the control group, also had the input of native speakers (the student teachers), one can question the validity of Canto et al.’s (2013) conclusions. Indeed, an online control group would have been necessary to ensure that the input provided by the native speakers did not influence the effect the online environment had on the results.

Lan (2014) assessed the use of Second life for the development of oral competency. In her study with Mandarin as a second language (MSL) learners, she reported on research in two phases which, in turn, used a qualitative and a quantitative design. The first phase was conducted with twenty adult MSL learners (mean age of 20) separated into an experimental group who were taught entirely in Second Life and a control group who received the same instruction in a regular classroom through face-to-face communication. The lessons consisted of two teaching units which were recorded and analyzed according to the distribution of classroom talk (teacher vs. students), and the characteristics of output (e.g. feelings, jokes, praises, questions). The analysis revealed that students using Second Life produced a higher distribution of output when compared to the teacher and produced more open-ended output (e.g. sharing feelings and opinions) than students in the control group. Unfortunately, as mentioned by the author, students using Second Life tended to not focus on the task and enjoyed moving freely around the world without paying attention to the instructions. This first phase confirmed the potential of virtual worlds for the quantity of student output. Unfortunately, very little is discussed with regards to the characteristics of the output produced in the two environments and their possible implications for language learning.

The second phase of Lan’s study (2014), conducted with 24 MSL learners (mean age of 19.5), assessed the development of vocabulary and grammar structure comprehension and

23

attitudes in the context of Second Life. The treatment consisted of 9 one-hour sessions in the virtual world in which participants had to learn words (e.g. food, souvenirs) and grammar structures in Mandarin, reinvest them in a task during which they found out about a host using clues, and finally buy appropriate objects at the virtual super market for the host. Pretests and post-tests were administered. The first pretest and post-test aimed at assessing the comprehension of said words and grammar structures. The second pretest and post-test evaluated the students’ attitudes towards learning Mandarin with the game. Unfortunately, very little is explained about the tests that were used, and the only example given by the author is a multiple-choice comprehension question about a verb tense presented in the treatment. Furthermore, the example is not linked to any of the tasks the students had to perform in the virtual world. Consequently, one may question how the test really reflected the students’ acquisition of words and grammar items in the context of the game. Nevertheless, the author found that virtual worlds were an ideal environment for second language learning both for attitudes and the acquisition of Mandarin words and grammar structures. She explains that the authentic environment of the virtual world enhanced the participants’ comprehension and reinvestment of the words and structures. Unfortunately, the actual effect of the game on the participants’ comprehension is difficult to establish since no control group took part in the study. After experiencing many technical difficulties (due to internet connections for example), she also explained that it is important to simplify the technological requirements (e.g. the need for high-end computer hardware) related to the use of such worlds.

Elsewhere, Lan et al. (2016) also reported on a study with MSL learners which aimed at comparing two types of tasks within a virtual world (Second Life). To do so, the authors compared two randomly-divided experimental groups of 15 MSL learners (age 19-24) who followed similar treatments but with different types of tasks. One group was taught using information-gap tasks, while the other carried out reasoning-gap tasks. The treatment consisted of three teaching packages that followed simple themes such as choosing gifts and included the teaching of specific words and sentence patterns. To establish a comparison between task type, they assessed each group’s oral accuracy and attitudes before and after a nine-week treatment. To test the participants’ evolution with respect to oral accuracy,

24

students had to listen to sentences to select appropriate pictures, as well as produce their own sentences orally while listening to questions. All questions targeted items found in the tasks.

Lan et al.’s (2016) conclusions provided insight into the peculiarity of virtual worlds and MMORPGs. Indeed, while both experimental groups improved their attitudes and their oral accuracy, reasoning-gap tasks (compared to information-gap tasks) were found to have a greater impact on both variables. In this regard, they explained that these findings are both counterintuitive and contrast with previous studies that have explored task types in a classroom environment. Indeed, they explain that previous studies on task type had found information-gap tasks to be more efficient. Lan et al. (2016) propose that this difference was partly due to the lack of face-to-face communication within the virtual world which made information sharing more difficult. However, one must note that since the two types of tasks were attributed to different groups, personal differences between students in each group may have played a role in group cohesion and completion of the different tasks. Furthermore, one can question the validity of the authors’ instruments with respect to oral accuracy for the test they used evaluated specific linguistic items individually, while the tasks were carried out cooperatively in the game using communicative tasks.

Reinders and Wattana (2011) also explored interactions as well as willingness to communicate within a MMORPG (Ragnarok Online) using three different tasks created from the quests found in the MMORPG. After analyzing the quests, the researchers concluded that they were unsuitable for language learning and they were modified. Unfortunately, very little detail as to the principles used behind their modification is provided outside of references to the importance of adding university coursework-related material within the already available quests and to making the quests more suitable for language learning by, for example, shortening the time necessary for their completion. While many principles of TBLT were mentioned, such as the use of real-life tasks as a basis for task design, no link to the task type was created by the authors. The tasks were carried out by sixteen ESL university in Thailand (age 21-26). The participants had to complete an attitude questionnaire, and the task-based interactions were recorded (via chat and voice) and transcribed. Reinders and Wattana’s (2011) analysis assessed interactions both for quality and quantity by looking at the

25

characteristics of participant output and turns (length and number). Their conclusions on the matter is that the interactions within tasks with the MMORPG saw a positive change in quantity (number of turns) but not in quality. Indeed, the interaction analysis revealed that students increased the number of turns they produced in the MMORPG, but that the accuracy and the complexity of their discourse did not increase between tasks. They also found that the medium used by students (either voice or chat) influenced the type and quality of interactions. For example, students tended to use formulaic language more often during oral interaction than written interaction. More importantly for the present study, Reinders and Wattana (2011) revealed that students provided little attention to form. They explained that participants were probably not able to focus on both form and meaning at the same time since the cognitive load of carrying out the tasks with the game was high.

Elsewhere, Suh et al. (2010) carried out a study on the effectiveness of MMORPG-based instruction in a Korean school context. Their objectives were to explore the differences in learning outcomes between face-to-face communication and the use of a MMORPG, and the impact of "gender, prior knowledge, motivation for learning, self-directed learning skill, computer skills, game skills, computer capacity, network speed and computer accessibility" (Suh et al., 2010, p. 370) on student learning with the game. They compared 302 fifth and sixth-grade Korean students of English as a second language separated in two groups: one treatment group which used a MMORPG called Nori School (created for this purpose), and one control group which followed the same instructions using face-to-face interaction enriched with multimedia. Participants attended a 40-minute class twice a week for two months. In the MMORPG, students were required to complete quests in teams (such as defeating a monster) which led to learning activities (e.g. reading a book and subsequently answering a quiz). The students would then complete the learning activity and agree on the answers mostly through chat. Completing the learning activities allowed students to subsequently move to the game’s next level. Five tests (English learning achievement, motivation, self-directed skill, computer use ability and game skill) and a survey were used to compare both groups.

26

Suh et. al (2010) concluded that MMORPGs can be useful for predicting improvement when learning English as a second language. Indeed, students using the MMORPG had higher scores in writing, reading and listening. Furthermore, they concluded that prior knowledge, motivation and network speed were the most influential variables impacting improvement when learning with the game. Network speed was found to be more important than motivation. The authors explained that losing the connection may have impacted motivation which in turn impacted student learning. While the conclusions brought forth by Suh et al. (2010) are important as they are the only study reviewed for the present study to have dealt with children, one must nonetheless point out that their approach towards MMORPGs is different than what is suggested in most of the literature. Indeed, while most studies advocate the use of tasks as defined by TBLT, Suh et al.’s study used MMORPGs to help students cover the necessary and very similar materials as the control group by providing them with an incentive (i.e. the quests used to trigger learning activities) to start doing the tasks. One can thus question how the conclusions of Suh et al.’s study (2010) can be applied to the use of MMORPGs as seen in most studies.

As reviewed, only a limited number of studies have tackled the subject of task-based interaction with MMORPGs or virtual worlds, and apart from Suh et al. (2010), all have done so with adults. Furthermore, to my knowledge, Jauregi et al.’s (2011) and Liang’s (2012) studies were the only ones which provided evidence, albeit limited, of FoF in online task-based interaction within a virtual world or a MMORPG. As explained, Reinders and Wattana (2011) and Lan et al. (2016) included FoF in their studies, but they did not provide systematic evidence of FoF during tasks carried out in a MMORPG or a virtual world. Although the present study does not involve online interaction, it does attempt to assess the presence of FFEs during face-to-face tasks supported by the use of a MMORPG as a stimulus for interaction.

3.2 Negotiated interaction: Classroom research with adolescents and adults

Research on incidental FoF is substantial (Ellis et al., 2001a; Ellis et al., 2001b; Loewen, 2003; Loewen, 2004; Lyster 1998a, 1998b; Lyster & Ranta, 1997; Williams, 2001). As such, only studies most relevant to the present research are reviewed. Researchers who