Mothers' and teachers' autonomy support on

students' school adjustment

: The mediating role of

satisfaction and frustration on basic psychological

needs

Mémoire

Angel Anne-Lise Charlot Colomès

Maîtrise en psychopédagogie - avec mémoire

Maître ès arts (M.A.)

Québec, Canada

Le soutien à l’autonomie de la mère et des enseignants sur

l’ajustement des jeunes en milieu scolaire : Le rôle

médiateur de la satisfaction et frustration des besoins

psychologiques fondamentaux

Mémoire

Angel Anne-lise Charlot Colomès

Sous la direction de :

iii

Résumé

Il existe une riche littérature portant sur la contribution du soutien à l’autonomie de la mère et des enseignants sur l’ajustement des jeunes en milieu scolaire. Cependant, peu d’études ont tenté d’évaluer les mécanismes responsables de ce lien. Fondée sur la théorie de l’autodétermination (TAD ; Ryan & Deci, 2017), la présente étude tente de combler les lacunes empiriques en évaluant un modèle qui explore le rôle médiateur des besoins psychologiques chez les jeunes dans la relation entre le soutien à l’autonomie de la mère et des enseignants et leur ajustement à l’école. L’échantillon était constitué de 271 jeunes mauriciens du secondaire (127 garçons, 144 filles) de 10e et 11e années (âge moyen de 15,5 ans) ayant répondu à un questionnaire mesurant leurs perceptions des relations avec leur mère et leurs enseignants, ainsi que leur ajustement scolaire, social et émotionnel. Les analyses basées sur la modélisation par équations structurelles ont révélé que la satisfaction et la frustration des besoins psychologiques agissent comme médiateurs entre le soutien à l’autonomie et l’ajustement, mais selon des patrons d’associations distincts pour la mère et les enseignants. Ces résultats sont abordés et discutés à la lumière de la TAD. Les principales limites et implications de l’étude sont également soulevées.

Mots clés : Théorie de l’auto-détermination, satisfaction et frustration des besoins psychologiques fondamentaux, soutien à l’autonomie, ajustement scolaire.

iv

Abstract

There is a broad literature that depicts the relationship between mothers’ and teachers’ autonomy support on students’ adjustment at school. Yet, the mechanisms underlying this link have received less attention. Grounded on the self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2017), the present study aimed to address this gap in the literature by testing a model illustrating basic psychological needs satisfaction and their frustration as mediators in the association between autonomy support and school adjustment. The sample consisted of 271 Mauritian adolescent students (127 boys, 144 girls) in 10th and 11th grade (mean age of 15,5 years old) who responded to a questionnaire measuring their perceived relationships with their mother and teachers as well as their academic, social and emotional adjustment. Analyses relying on structural equation modeling showed that basic psychological needs satisfaction and frustration mediated the relationship between autonomy support and school adjustment. However, distinct patterns of mediation were observed from mothers and teachers. These results are presented and discussed based on SDT. The limitations and implications of the present study are also highlighted.

Keywords: Self-determination theory, satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs, autonomy support, school adjustment.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Résumé ... iii

Abstract ... iv

List of tables ... vii

List of figures ... viii

List of abbreviations ... ix

Acknowledgements ... x

INTRODUCTION ... 1

CHAPTER 1: PROBLEM STATEMENT ... 4

1.1. School Adjustment ... 4

1.2. Parents and teachers as protective agents ... 5

1.2.1. Autonomy support from parents ... 7

1.2.2. Autonomy support from teachers ... 7

1.3. The underlying mechanism ... 8

CHAPTER 2: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 9

2.1. Self-determination theory ... 9

2.1.1. The need for competence ... 10

2.1.2. The need for relatedness ... 10

2.1.3. The need for autonomy... 11

2.1.4. The interdependence of needs ... 11

2.2. Needs satisfaction and frustration ... 13

2.2.1. Need satisfaction and school adjustment ... 13

2.2.2. The distinction with need frustration ... 14

2.2.3. Autonomy support and needs satisfaction/frustration ... 16

2.2.4. The mediating role of need satisfaction and frustration ... 18

2.3. The gap in the literature and novelty of the present study ... 19

2.4. The purpose of the study and hypotheses ... 20

CHAPTER 3: THE MAURITIAN CONTEXT ... 23

3.1. The socio-demographic characteristics... 23

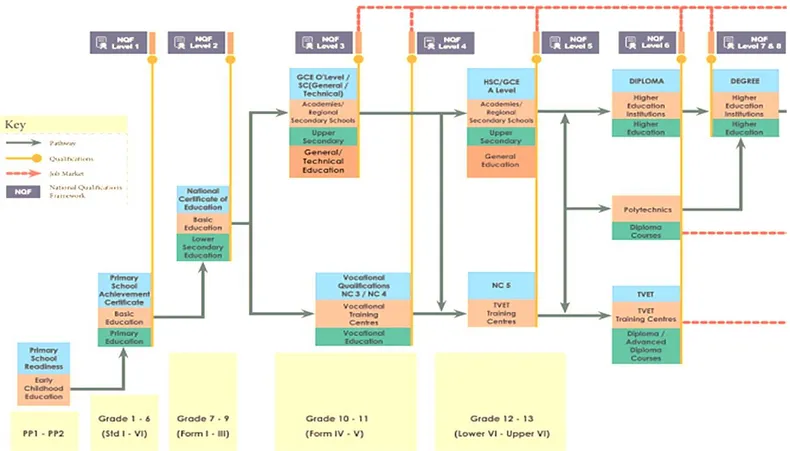

3.2. The educational system ... 23

CHAPTER 4: METHODOLOGY ... 27

4.1. Participants ... 27

vi

4.3. Measures ... 28

4.3.1 Perceived mothers’ autonomy support. ... 28

4.3.2 Perceived teachers’ autonomy support. ... 29

4.3.3 Satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs. ... 29

4.3.4 School adjustment. ... 30 4.4. Statistical analyses ... 31 CHAPTER 5: RESULTS ... 34 5.1. Preliminary analyses ... 34 5.1.1 Descriptive statistics ... 34 5.1.2 Mean differences ... 36 5.2. Main analyses ... 36 5.2.1. Direct effects. ... 37 5.2.2. Indirect effects. ... 40 CHAPTER 6: DISCUSSION ... 43

6.1. Unique relations of the social sources with basic psychological needs and school adjustment ... 43

6.2. Basic psychological needs as explanatory mechanisms... 44

6.2.1. The need for relatedness ... 44

6.2.2. The need for competence ... 48

6.2.3. The need for autonomy... 49

6.3. Strengths of study, limitations and recommendations ... 49

6.4. Implications... 51

CONCLUSION ... 54

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 55

vii

List of tables

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of sample………...……….27 Table 2. Internal consistency of each factor in the satisfaction and

frustration of basic psychological needs scale………...………….30 Table 3. Means, standard deviations and zero-order correlations of all study variables………...35 Table 4. Direct and indirect effects, path estimates, SE and 95% CI for the theoretical model……….………41

viii

List of figures

Figure 1. Hypothesized model based on Self-Determination Theory…..22 Figure 2. New Educational Pathway…………...……….26 Figure 3. Proposed path model with gender as control variable………...33 Figure 4. Predictive relationship between mother and teacher autonomy support, satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs and school adjustment dimensions………...39

ix

List of abbreviations

CPE- Certificate of Primary Education

MESR- Ministry of Education & Scientific Research MIE- Mauritius Institute of Education

x

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my deepest appreciation to my supervisor, Mr. Stephane Duchesne who provided me with the continuous support, encouragement and patience I needed to fulfill my tasks as a research student. You were a tremendous mentor. Thank you for being so passionate about what you do.

I am also grateful to Mrs. Geneviève Boisclair Chateauvert and Mrs. Bei Feng for sharing with me their remarkable skills and knowledge in data analysis. Thank you for having spared some of your time from your busy schedules. It means a lot to me.

Thank you to all the members of the GRIP from the 9th floor at the faculty who have been so supportive throughout my two years of study.

Thank you to all my professors Mrs. Sylvie Barma, Mr. Simon Larose and Mr. David Litalien. I am so fortunate to have been one of your students and learnt so much from you.

A special thanks to my correspondent from Mauritius, Dr. Jimmy Harmon, whose assistance and counselling were vital for the success of the study.

I also wish to express my deepest gratitude to the school directors, teachers, students and their parents from Bon et Perpetuel Secours College of Beau-Bassin and La Confiance College who gave access to their premises and genuinely collaborated in the study. This project would not have been achievable without your trust and openness to research and novelty.

I gratefully acknowledge the funding that I received from the “Programme Canadien de Bourses de la Francophonie”. Special thanks to Mr. Tony Toufic, Mrs. Diane Cyr and all the staff members for your diligent work and contribution.

xi

I am also grateful to my dear friend, godmother and sister from another mother, Maha Hassoun for her support, love and care. I could not ask for a better friend. You are irreplaceable.

I am indebted to my family whose love and support kept me strong especially during the toughest moments of my stay in Canada. Special thanks to my father, mother, sisters, cousins, aunts and uncles. It was an honour to elevate our family name.

In memory of my dear uncle, Steeve Alexandre, who was so encouraging about my journey to Canada. Wherever you may be, I pray your soul is at peace. I miss you so much.

Finally, I wish to convey my upmost gratitude to God for his protection, trust and love. May his spirit guide me to my purpose in this world.

1

INTRODUCTION

According to a Mauritian educational report, among the 15,675 students who sat for the School Certificate exams in 2015, only 9,490 of them successfully followed the academic pathway and took part in the Higher School Certificate exams two years later (Statistics Mauritius, 2019). Likewise, the highest drop-out rate (25 %) and repetition rate (30%) recorded in 2017 were among grade 11 students (Statistics Mauritius, 2019). In spite of such a decline in students’ perseverance and adjustment at secondary level, no recent report or study has, until now, sought to identify the antecedents of this trend and remediate to it.

One plausible explanation to such records could be the restrictive conditions within the Mauritian educational system which may relate to difficulties in school adjustment (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Indeed, admission to “high achiever” schools and academies is, on one side, viewed as a privilege to higher quality education and, on the other side, as a bridge to better career and scholarship opportunities (Hollup, 2004; Paviot, 2015). However, due to limited seats and selective enrolments to such institutions, the learning process became exam oriented (Hollup, 2004; MESR, 2001). As a result, the school system has been distorted by a competitive culture, exerting psychological pressure and stress on students and parents (Foondun; 2002; Hollup, 2004; Reddi, 2017). Moreover, the focus on academic outcomes has exposed teachers to various pressures from above manifested in the form of overloaded curricula, limited freedom and time to manage them, as well as imposed teaching methods undermining students’ learning experience (MIE, 2002; Paviot, 2015). These pressures were found to predict a decrease in teachers’ autonomous motivation which in turn led to their engagement in autonomy frustration practices (Pelletier, Séguin-Lévesque, & Legault, 2002). Parents are also aware of the deficiency in the educational system and of the factors compromising quality teaching (Foondun, 2002). For

2

fear that their children may be left out in the classroom, most parents register them to after-school private tuitions adding up to nine hours of instruction per day (Foondun, 2002; Mmathoorah, 2012). This pattern has subsequently led to the institutionalisation of private tuitions; a means that nurtures a “rat race” while further limiting students’ free time (Paviot, 2015).

Exposure to high stakes evaluations, external rewarding and controlling environments can actually threaten students’ autonomy or the ability to take self-endorsed actions or decisions (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Around the age of 10 to 19 years old, students face adolescence; a transitional stage of development involving physiological, emotional and psychosocial changes that pave their way to adulthood (UNICEF, 2011). These imbalances along with what Erikson (1968) described as an “identity crisis” are the elements that portray adolescence as a fragile phase of life (Droehnlé-Breit, 2006). It is the time where youngsters acquire a greater sense of volition while they struggle to affirm their identity and develop their own values (Braconnier, 2007; Vansteenkiste, Niemiec, & Soenens, 2010). Autonomy development is therefore viewed as one of the most crucial developmental tasks during adolescence (Pardeck & Pardeck, 1990) whose cascade influence on other developmental domains can determine adolescents’ future adjustment trajectories (Cook, Wilkinson, & Stroud, 2018). Indeed, perceived autonomy was found to be significantly related to better school-related adjustment characterised by perceiving the school as supportive, valuable and meaningful, engaging confidently in school activities and being cared for by their peers (Doren & Kang, 2016). Furthermore, studies revealed that autonomy support from both parents and teachers predicted for an increase in students’ perceived competence and intrinsic academic motivation which consequently led to school persistence (Hardre & Reeve, 2003) and fewer drop out behaviours (Studsrod & Bru, 2009; Vallerand, Fortier, & Guay, 1997).

3

The main goal of this masters’ thesis is to evaluate and explain for the role of autonomy supportive practices engaged by parents (particularly mothers) as well as teachers on Mauritian students’ school adjustment at secondary level. More precisely, the present study is supported by the self-determination theory which posits that the satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness can operate as mechanisms through which supportive environments influence adjustment (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

This thesis consists of six chapters. The first chapter provides a picture of the societal and scientific relevance of the key concepts and associations, stressing on the benefits of autonomy supportive behaviours from various contexts on adjustment. This chapter concludes with the presentation of the main objectives of the study. The second chapter introduces SDT and its core elements, which are also validated through a literature review that depicts the existing knowledge around autonomy support, needs satisfaction-frustration and school adjustment. This chapter also proposes the hypotheses of the present study that address the gap in the literature. The third chapter portrays the geographic and cultural specificity of the studied population, that is, the Mauritian context. The fourth chapter presents the characteristics of the sample and the research method namely, the sampling and data collection procedure as well as the instruments and analyses used to measure and assess the variables. The fifth chapter conveys the preliminary and main results pertaining to the objectives and hypotheses of the study. Finally, the sixth chapter discusses the results, their theoretical and practical implications as well as proposes recommendations for future research.

4

CHAPTER 1: PROBLEM STATEMENT

Schools are one of the main institutions in society responsible for adolescents’ healthy psychosocial development (Fletcher et al., 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2017; Verschueren, 2015). Not only do they forge student’s knowledge of the world and prepare them to job life, but they also offer them a suitable socialising environment (Tian, Tian, & Huebner, 2016). Indeed, adolescents spend a substantial amount of time at school where they interact mostly with their peers and teachers (Takakura, Wake & Kobayashi, 2010; Tian, Liu, Huang, & Huebner, 2013). These social exchanges along with their school experiences help adolescents to shape unique perceptions of their student lives, crucial in determining their adjustment orientations throughout their academic journey (Danielsen, Samdal, Hetland, & Wold, 2009; Tian et al., 2013).

1.1. School Adjustment

Adjustment is referred to as a condition where an organism strives to be in equilibrium with its environment (Sawrey & Telford, 1967). It is a process that involves coping and change with the aim to maintain optimum interaction between a person and his surroundings (Sawrey & Telford, 1967). Adjustment does not involve a single process but rather the interplay of behavioural, emotional and psychological processes that pave the way to coping with pressures and demands (Lazarus, 1969). As a result, adjustment cannot be viewed as a single construct as it operates through various aspects and dimensions.

Baker and Siryk (1984, 1986) propose a multifaceted conceptualisation of school adjustment that involves various demands varying in nature and intensity and which can be addressed through various coping responses. They suggest that school adjustment consists of three dimensions notably, academic, social and personal-emotional. Academic adjustment pertains to students’ ability to cope with educational demands while considering their feelings of effectiveness and

5

satisfaction about their performances. Social adjustment relates to students’ coping with interpersonal demands and involvement in relationships within the school community. Finally, personal-emotional adjustment focuses on students’ physical and psychological state as they strive to cope with stressful occurrences and school demands.

Research revealed that students who are well-adjusted at school experience positive school outcomes, including better academic achievement (Adhiambo, Odwar, & Mildred, 2011), fewer conduct problems (Liu, Lan, Hsu, Huang, & Chen, 2014), delayed onset to alcohol use (Henry, Stanley, Edwards, Harkabus, & Chapin, 2009), lower emotional distress (Wilkinson-Lee, Zhang, Nuno, & Wilhelm, 2011), higher self-esteem (Sbicigo & Dell’Aglio, 2013) and fewer depressive symptoms (Shochet, Homel, Cockshaw, & Montgomery, 2008). Studies also support for the buffering effect of school adjustment in the negative relationships between social factors and students’ mental health (Carney, Kim, Hazler, & Guo, 2017; Wilkinson-Lee et al., 2011). Adjusting to the school environment and its demands is therefore crucial towards students’ socialisation, psychological growth and well-being.

1.2. Parents and teachers as protective agents

Students’ positive adjustment is highly under the influence of key socialising contexts, especially the family and the school (Ratelle, Duchesne, & Guay, 2017; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Parents and teachers are viewed as the closest social agents within adolescents’ social environment whose support and guidance help in shaping their beliefs system, behaviours and psychosocial development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). On one side, parents are the primary socializers on whom adolescents rely for resources, guidance, care and protection (Maccoby, 2015). Teachers, on the other side, are viewed as the adult figures within the school environment who provide adolescents with the conditions and means that favour their cognitive development and the emotional support they require

6

in times of learning difficulties or maladjustment at school (Verschueren, 2015). Although these two socialising agents operate on distinct territories, they play unique roles in facilitating adolescents’ adjustment to school (Jungert & Koestner, 2013; Vallerand et al., 1997).

SDT recognises autonomy support as one of the most salient practices engaged by both parents and teachers to favour adolescents’ well-being and subsequently, their adjustment (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Autonomy support is defined as «the degree to which the environment allows individuals to feel that they initiate their actions, rather than feel that they are being coerced» (Grolnick, 2003, p. 13). It involves the provision of choice and the encouragement for one’s initiation in self-endorsed behaviours (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Ryan, Deci, Grolnick, & La Guardia, 2006). It is also contrasted with the term “psychological control” which refers to the use of intrusive psychological and emotional strategies such as guilt induction, shaming and love withdrawal that aim to change adolescents’ feelings, behaviours and opinions and make them comply to adults’ expectations (Barber, 1996).

SDT proposes that autonomy support remains relevant in all relationships, although these may differ in nature and function (Ratelle, Simard, & Guay, 2013; Ryan & Deci, 2017; van der Kaap-Deeder, Vansteenkiste, Soenens, & Mabbe 2017). Nonetheless, students’ do perceive autonomy support differently from parents and teachers (Guay, Ratelle, Larose, Vallerand, & Vitaro, 2013). Indeed, studies evaluating the joint influence of parents and teachers revealed that their autonomy supportive practices related uniquely and independently to students’ functioning and adjustment (Guay et al., 2013; Guay & Vallerand, 1997; Ratelle et al., 2013; van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2017).

7 1.2.1. Autonomy support from parents

Parents who acknowledge their adolescents’ autonomy offer them choice, provide rationale to rules and behaviours that are required of them as well as take into consideration their perspectives (Ryan & Deci, 2017). The existing literature indicates a clear association between parental autonomy support and various indicators of their adolescents’ positive school adjustment. For example, a meta-analysis including 36 parenting studies (Vasquez, Patall, Fong, Corrigan, & Pine, 2015) showed that children and adolescents whose parents were autonomy supportive expressed more autonomous motivation and engagement at school, performed academically better and were psychologically healthier. A parent- adolescent relationship favouring autonomy support was also found to be linked to enhanced academic and social adjustment (Joussemet, Koestner, Lekes, & Landry, 2005). Similar findings were obtained in other studies where children’s perceptions of autonomy support from their parents predicted their school adjustment (Ratelle et al., 2017; Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2005).

1.2.2. Autonomy support from teachers

Teachers who exercise autonomy supportive practices establish a consistency between students’ autonomous motivation and the completion their school tasks (Jang, Reeve, & Deci, 2010; Reeve, Jang, Jeon, & Barch, 2004). They do so by acknowledging students’ perspectives and by nurturing their needs and interests during classroom activities (Stroet, Opdenakker, & Minnaert, 2015; Jang et al., 2010). Tsai and colleagues (2008) provide support to these statements by reporting that perceived teachers’ autonomy support positively correlated with students’ gain of interest during lessons. Students’ interests are fostered by settling learning goals and tasks that are viewed as meaningful, valuable and challenging to them (Jang et al., 2010). Autonomy supportive teachers also create opportunities where students can take their

8

own initiatives in solving issues related to their studies (Jang et al. 2010). For instance, an autonomy supportive learning environment allows students to be in control of their learning experience while stimulating their autonomous motivation to participate in school activities. Studies revealed that teachers’ autonomy support positively predicted various important school-related outcomes including students’ perceived competence, autonomous motivation, school perseverance, school engagement as well as school performance (Hardré & Reeve, 2003; Jang et al., 2010; Reeve et al., 2004; Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Soenens, & Matos, 2005).

1.3. The underlying mechanism

Although there exists substantial evidence which confirms the association between autonomy supportive contexts and school adjustment, the underlying mechanism that may account for this relationship remains underexplored. In fact, being well-informed about the process through which parents and teachers favour students’ adjustment could provide a clearer understanding of their distinct and unique contributions as social agents. However, most of the existing research has been focused on explaining the predictive role of autonomy support on other students’ outcomes such as intrinsic motivation (Banack, Sabiston, & Bloom, 2011), subjective vitality (Adie, Duda, & Ntoumanis, 2012) and school engagement (Yu, Li, & Zhang, 2015). SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2017) proposes a motivational mechanism that depicts the role of basic psychological needs’ satisfaction and frustration as explanatory processes involved in students’ adjustment.

Grounded on SDT, the aims of the present study are twofold. Firstly, to assess the relationship between social agents’ (mother and teacher) autonomy supportive behaviours and students’ school adjustment while distinguishing their unique contributions. Secondly, to evaluate the mediating role of basic psychological needs’ satisfaction and frustration.

9

CHAPTER 2: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1. Self-determination theorySDT is an organismic-dialectical perspective that defines human beings as proactive organisms who are inherently propelled to grow, function and adjust within their social surroundings (Deci & Ryan, 2000). SDT postulates that these inherent capacities are driven by individuals’ basic psychological needs and that the latter can be fulfilled by contributing social and contextual factors (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Basic psychological needs are defined as «innate psychological nutrients that are essential for ongoing psychological growth, integrity, well-being» (Deci & Ryan, 2000, p. 229). This definition proposes a two-fold feature of needs, one as organismic and the other as functional, where needs drive human thriving, health and integration on the condition that they are being nourished, since failure to supply these nutrients can have detrimental psychological consequences on an individual (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Needs are therefore viewed as vital conditions for human psychological well-being. Consequently, SDT views a basic psychological need as the nutrient whose satisfaction guarantees an individual’s healthy psychological processes, cognitive growth, adjustment and well-being while its deprivation may lead to non-optimal psychological outcomes, maladjustment and ill-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017). SDT posits that alongside physical needs such as food and shelter, basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness and competence are fundamental resources on which a person is dependent for full functioning (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

10 2.1.1. The need for competence

The need for competence is defined in SDT as the feeling of efficacy, ability and success in one’s interactions within a social environment (Deci & Moller, 2005; White, 1959). Feelings of competence are experienced in contexts that provide individuals with opportunities and resources to express, develop and master their skills (Deci & Moller, 2005; Ryan & Moller, 2016; White, 1959). Competence satisfaction depends on the individuals’ perceived degree of control over their activities and behaviours. In fact, SDT scholars view competence as a concept closely attached to the self since it is the self that nourishes an individual’s feelings of effectance (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Ryan & Moller, 2016). Therefore, one’s need for competence can only be satisfied on the condition that individuals, firstly, engage in activities that are self-initiated and secondly,acknowledge ownership of their accomplishments (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

2.1.2. The need for relatedness

The need for relatedness refers to the feeling of connectedness or belongingness to a person or a particular group (Deci & Ryan, 2000). The need for relatedness can be fulfilled only in relationships that are autonomous and authentic in the eyes of the self and of others (Ryan & Deci, 2017). For example, one cannot hope to feel loved and cared for in relationships that are imposed to them. Moreover, even though people were to act in ways that are expected of them with the aim to please others or to gain recognition, the need for relatedness will not be met unless their behaviours are perceived as autonomous and valued by the self (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

11 2.1.3. The need for autonomy

The term “autonomy” is literally defined as “self-governing” or referred to self-regulation which is the process of regulating one’s experiences and actions by the self (Ryan & Deci, 2017). The need for autonomy is further described by SDT scholars as a feeling of volition whereby one’s actions are integrated by the self or self-endorsed rather than being externally regulated (Deci & Ryan, 2000; de Charms, 1968; Ryan & Connell, 1989). The antonym to the term “autonomy” is “heteronomy”, which is defined as the experience of being controlled or overruled (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). Furthermore, SDT distinguishes the concept of autonomy from independence. Independence involves non-reliance on others’ guidance or support which can turn out to be either autonomously or heteronomously driven (Chirkov, Ryan, & Kim, 2003; Ryan & Lynch, 1989). Autonomy, on the contrary, implies self-endorsement which does not deprive one’s feelings of connectedness with others(Ryan & Deci, 2017).

2.1.4. The interdependence of needs

Deci and Ryan (2000) assert that all three basic psychological needs are invaluable and that the frustration of one of them can be problematic to an individual’s full functioning. This suggests that a healthy human being is one whose all three basic psychological needs are mostly satisfied. Nevertheless, in certain situations, one of the three needs may take the lead, while the others remain independently important (Ryan & Deci, 2017). In tandem, SDT posits that the satisfactions of the needs for autonomy, relatedness and competence are more inclined to be interdependent, for example, in most situations, the satisfaction of one need will tend to facilitate the satisfaction of the others (Ryan & Deci, 2017). On those grounds, the need for autonomy has received considerable attention due to its key role in the satisfaction of the other needs (Ryan & Deci, 2017). SDT postulates that as long as people’s

12

behaviours, relationships and skills are perceived as owned, valued and self-integrated, i.e. autonomously driven, their needs for autonomy, relatedness and competence will be achieved (Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O’Connor, 1994; Deci, La Guardia, Moller et al., 2006; Ryan & Deci , 2017).

Indeed, both feelings of competence and autonomy were found to work simultaneously in triggering and sustaining students’ intrinsic motivation at school tasks (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999; Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). Similarly, autonomy and relatedness were found to be interrelated within close relationships (Allen et al., 1994; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Moreover, autonomy has been found to be detrimental to adolescents’ behaviours in contexts that deprive any sense of attachment to the family and society (Chassin, Presson, & Sherman, 1989; Crittenden, 1990). Some SDT scholars even view the concepts of autonomy and relatedness as a single overall construct known as “autonomy relatedness” showing their intertwined roles in maintaining healthy development and close relationships in adolescence (Allen et al., 1994; Inguglia, Liga, Lo Coco et al., 2018).

The interrelation between the need for competence and relatedness can be demonstrated in situations where people’s achievement or skills are considered as requirements for group memberships. For example, when people exhibit a need to be affiliated to such a group, they will experience a need to be competent enough so as to prove others and themselves that they are worthy to be part of that group. Reciprocally, the sense of affiliation to such a group can only be maintained as long as members perceive themselves as meritorious of their status in that group, i.e. through their feelings of competence. Accordingly, SDT posits that all three basic psychological needs are expected to demonstrate high intercorrelations across domains and contexts (Chen, Vansteenkiste, Beyers, Boone et al., 2015; Ryan & Deci, 2017).

13 2.2. Needs satisfaction and frustration

SDT further proposes that any fluctuation in need satisfaction will elicit variations in people’s readiness to be fully functional and to consequently experience well-being (Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan et al., 2011; Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017). While autonomy satisfaction implies full endorsement of behaviours, autonomy frustration relates to the experience of control, pressure and coercion (de Charms 1968; Nishimura & Suzuki, 2016; van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2017). When the need for relatedness is fulfilled, people experience authentic connectedness and intimacy with others (Ryan, 1995). On the other hand, relatedness frustration relates to the experience of loneliness and social isolation (Nishimura & Suzuki, 2016; Ryan 1995). Finally, competence satisfaction fosters feelings of effectance and achievement while its frustration will induce the experience of failure and worthlessness (Ryan 1995; van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2017; Vansteenkiste et al., 2010).

2.2.1. Need satisfaction and school adjustment

Many studies have supported the role of basic psychological needs satisfaction in promoting various aspects of students’ adjustment (Rodriguez-Meirinhos, Antolin-Suarez, Brenning et al., 2019; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Recently, Duchesne, Ratelle and Feng (2016) observed in a longitudinal study that the satisfaction of the need for autonomy, relatedness and competence predicted later academic and social adaptation at secondary level. Similarly, Yu and colleagues (2015) revealed that basic needs satisfaction at grade 8 predicted an increase in students’ school engagement in grade 9. These results coincide with previous studies whereby high levels of perceived needs satisfaction were found to relate to better academic, social and personal-emotional adjustment (Ratelle & Duchesne, 2014) while low needs satisfaction

14

predicted a decrease in school adjustment (Ahmad, Vansteenkiste, & Soenens, 2013).

There is also extensive empirical evidence of the role of needs satisfaction on personal-emotional adjustment. For example, studies reported a covariation between fluctuations in needs satisfaction and day-to-day variations in students’ well-being (Reis, Sheldon, Gable, Roscoe, & Ryan, 2000). Similarly, Chen and colleagues (2015) reported that both the fulfilment of students’ need for autonomy and competence were associated with their well-being. The researchers also found relatedness satisfaction to be positively correlated to self-esteem but negatively linked to depressive symptoms. In a second study, the researchers found a positive relationship between needs satisfaction, life satisfaction and vitality among university students across four different cultural contexts (Chen et al., 2015). In parallel, need satisfaction was found to reduce students’ depressive and anxiety symptoms. These results converge with those in previous studies where need satisfaction was found to be positively related to indicators of personal-emotional adjustment including life satisfaction (Kasser & Ryan, 1999), subjective well-being (Tian, Chen, & Huebner., 2014), positive mood (Reis et al., 2000), self-esteem (Deci, Ryan, Gagné, Leone et al., 2001), and vitality (Liu & Chung, 2014; Reis et al., 2000).

2.2.2. The distinction with need frustration

Studies also revealed that low need satisfaction was associated with dysfunctional outcomes and ill-being (Chen et al., 2015; Hodge, Lonsdale, & Ng, 2008; Pelletier, Dion, & Lévesque, 2004). However, these findings are not consistent in the literature (Bartholomew et al. 2011). The researchers attribute these conflicting findings to the lack of direct measures of need frustration which, compared to low needs satisfaction, is believed to be far more detrimental to human development (Ryan & Deci, 2000). SDT scholars, in fact, point out that low need

15

satisfaction does not indicate the frustration of needs but rather that the latter are not fulfilled to the degree they are expected to (Bartholomew et al., 2011). Hence, low need satisfaction is expected to merely hinder growth potential (Bartholomew et al., 2011; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Vansteenkiste and Ryan (2013) further explain this distinction through their plant metaphor by comparing low need satisfaction to depriving a plant of sunlight and water, whereas need frustration to the spreading of salt other it. In both situations, the plant is bound to die but the process is accelerated in the case of need frustration. In their recent study, van der Kaap-Deeder and colleagues (2017) provided empirical support to this plant metaphor by showing that autonomy support and psychological control (i.e., the frustration of the need for autonomy) related uniquely to well-being and ill-being, respectively. Autonomy support was precisely related to higher well-being via need satisfaction while need frustration mediated for the relationship between psychological control and ill-being. These findings were consistent with previous studies where need satisfaction was found predictive of growth and well-being, while need frustration predicted ill-being and maladjustment (Cordeiro, Paixao, Lens et al., 2016; Haerens, Aelterman, Vansteenkiste et al., 2015; Longo, Alcaraz-Ibanez, & Sicilia, 2018; Longo, Gunz, Curtis, & Farsides, 2016). Need frustration is therefore distinguished as an active process where need satisfaction is persistently hindered (Bartholomew et al., 2011). It is, ultimately, the recurrent and intensified deprivation to need fulfillment that portrays need frustration as a significant predictor of diminished growth potential, maladjustment, psychopathology and ill-being (Bartholomew et al. 2011; Rodriguez-Meirinhos et al., 2019; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Stebbings, Taylor, Spray, & Ntoumanis, 2012; Vansteenkiste & Ryan 2013).

16

During the last decade, there has been a growing interest in need frustration and its consequences, although none were concerned with academic or social adjustment specifically but rather on students’ physical and psychological health. Indeed, studies on need frustration predicted physical exhaustion, depression, eating disorders and burnout among student athletes (Balaguer, Gonzalez, Fabra et al., 2012; Bartholomew et al., 2011). Research works have also reported the frustration of all three basic psychological needs to be positively associated to harmful outcomes among adolescents such as negative emotions (Liu & Chung, 2014; Reis et al., 2000) and problem behaviours (Yu et al., 2015). Additionally, Inguglia and colleagues (2018) recently reported that autonomy and relatedness frustration was positively associated to anxiety among adolescents.

2.2.3. Autonomy support and needs satisfaction/frustration The experience of need satisfaction varies largely on the degree to which social environments foster the conditions that are supportive to need fulfillment (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Because of their roles as key socializers, parents’ and teachers’ practices can either satisfy or thwart adolescents’ needs (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017). SDT recognises autonomy support as one of the most salient practices which acts either as a facilitator to the fulfillment of basic psychological needs (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017) or as a resilience factor to the consequences of need frustration (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013).

Recent studies corroborate these propositions by showing positive relationships between parents’ autonomy support and the satisfaction of adolescents’ need for autonomy, relatedness and competence (Costa, Cuzzocrea, Gugliandolo, & Larcan, 2016; Inguglia et al., 2018; Simsek & Demir, 2013; Wuyts, Soenens, van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2015). More specifically, mother autonomy support was found to be positively related to autonomy and competence satisfaction (Grolnick, Raftery-Helmer,

17

Flamm et al., 2014; Joussemet, Landry, & Koestner, 2008). Similarly, Inguglia and colleagues (2018) reported that maternal autonomy support was positively related to both autonomy and relatedness satisfaction but negatively and significantly associated to autonomy and relatedness frustration.

Adolescents spend most of their daily lives at school (Tian, Zhang, & Huebner, 2018). Schools are therefore suitable environments where basic psychological needs can be fulfilled under favourable conditions. Teachers are the closest social agents with whom adolescents interact within the school environment and whose behaviours can determine students’ satisfaction of their need for autonomy, competence and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2017). In fact, a longitudinal study among Norwegian students recently revealed teachers’ provision of autonomy to be predictive of later satisfaction of basic psychological needs (Diseth, Breidablik, & Meland, 2018). Previous studies have also found a positive relationship between teacher autonomy support and students’ satisfaction of their need for autonomy, relatedness, and competence (e.g., Reinboth, Duda, & Ntoumanis, 2004). There is also substantial empirical evidence within the sports context, where perceived coaches’ autonomy support was found to facilitate athlete students’ satisfaction of their need for autonomy, relatedness and competence (Balaguer, Castillo, & Duda, 2008; Banack, Sabiston, & Bloom, 2011; Gonzalez, Castillo, Garcia-Merita, & Balaguer, 2015; Loppez-Walle, Balaguer, Castillo, & Tristan, 2012; Morillo, Reigal, & Hernandez-Mendo, 2018). Alternatively, coaches’ autonomy support was found to be negatively related to young athletes needs frustration (Balaguer et al., 2012; Bartholomew et al., 2011).

18

2.2.4. The mediating role of need satisfaction and frustration While explaining the process of need frustration, SDT asserts that when need satisfaction cannot be achieved, due to non-supportive situations, individuals are instinctively driven to engage in defensive activities and behaviours that will compensate for their deficiency and protect them from the threat of unmet needs (Deci & Ryan, 2000). These protective accommodations are theorised to manifest through compensatory processes, e.g. the search for need substitutes, the development of non-autonomous regulatory styles and rigid behaviour patterns that are eventually held accountable for the significant adverse outcomes of need frustration on human development and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Niemiec, Ryan, & Deci, 2009; Ryan et al., 2006; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). Needs satisfaction and frustration can therefore be conceptualised as universal mechanisms that could explain for the relationship between favoring/undermining social environments and indicators of well-being/ill-being (Deci & Ryan 2000; Ryan & Deci 2000).

However, few studies have sought to evaluate the mediating role of basic psychological needs’ satisfaction and frustration in the relationship between autonomy support and students’ school adjustment. For example, Vallerand and colleagues (1997) confirmed a motivational model whereby students’ perceived competence and autonomy acted as mediators in the relationship between parents’ and teachers’ autonomy support, intrinsic academic motivation and dropout intentions. Likewise, Joussemet and colleagues (2008) showed that maternal autonomy support predicted students’ feelings of autonomy and relatedness, which in turn, positively predicted their school performance. Similar trends were observed in a longitudinal study among Chinese students, where satisfaction of basic psychological needs in 8th grade mediated the

relationship between perceived teachers’ autonomy support at 7th grade

19

and colleagues (2016) reported that the positive relationship between teachers’ support and students’ school-related subjective well-being was explained by the satisfaction of the need for autonomy, competence and relatedness. As for need frustration, no research has so far undergone the evaluation of its mediating role with respect to autonomy support and students’ adjustment. Nonetheless, the existing literature did portray need frustration as a significant mediator between controlling environments and ill-being (Balaguer et al., 2012; Bartholomew et al., 2011).

2.3. The gap in the literature and novelty of the present study Despite substantial evidence validating the propositions in SDT, there are issues that still remain unexplored and which require further insight. Firstly, no studies have, until now, attempted to investigate the pathway autonomy support

→

needs satisfaction and frustration→

school adjustment. For instance, these associations remain unexplored. Furthermore, school adjustment has rarely been evaluated as a multidimensional concept (Duchesne et al., 2016; Ratelle & Duchesne, 2014) and was instead predominantly assessed through indirect measures such as school engagement (Yu et al., 2015) or anxiety (Chen et al., 2015).The second issue pertains to the lack of empirical evidence in demonstrating the predictive role of multiple sources of autonomy support on all three basic psychological needs satisfaction. While some studies have focused more specifically on the need for autonomy or/and competence (e.g., Guay et al., 2013; Vallerand et al., 1997), others attempted to evaluate only composite scores of needs satisfaction or frustration (van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2017). The existing literature therefore limits our understanding on how the need for relatedness, along with the other basic psychological needs, is uniquely related to various autonomy supportive contexts and adjustment dimensions.

Thirdly, previous studies have been mostly focused on the contribution of need satisfaction rather than need frustration (Ryan &

20

Deci, 2017). Although there may be a growing interest in need frustration, we still know nothing about its mediating or predictive role on school-related outcomes, more specifically, on school adjustment. Moreover, these two concepts have barely been investigated simultaneously and even less as explaining mechanisms between autonomy support and school adjustment (Chen et al., 2015; Haerens et al., 2015; Rodriguez-Meirinhos et al., 2019; van der Kaap-Deeder et al., 2019).

Finally, though SDT has been applied to various cultures (e.g. Chen et al., 2015), no research works have attempted to test it in the Mauritian context, which is known for its unique social and cultural diversity (Ministry of Arts and Culture, 2013). The present study may bring further ground to the universality of the theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

2.4. The purpose of the study and hypotheses

With the aim to address the gap in the existing literature and to broaden our perspective in SDT, the purpose of the present study is to test for a model which examines the mediating role of basic psychological needs’ satisfaction and frustration in associations between autonomy supportive contexts and school adjustment. Figure 1 presents the hypothesized model. Accordingly, the present study formulates the following hypotheses:

(i) Perceived mothers’ and teachers’ autonomy supportive behaviours are expected to be uniquely related to students’ school adjustment, (ii) Perceived autonomy support from both mothers and teachers are

expected to positively predict school adjustment via the satisfaction of all three basic psychological needs,

(iii) Perceived autonomy support from both mothers and teachers are expected to positively predict school adjustment via the low frustration of all three basic psychological needs.

21

Finally, gender was specified as a control variable in the examined model due to gender-related differences observed in previous studies. More specifically, females were found to report higher levels of support from their teachers and parents as compared to males (Rueger, Malecki, & Demaray, 2010). Contradictory findings revealed that boys were more socially supported by their teachers than girls (Tian et al., 2016). Boys were also found to score higher in autonomy-supportive teaching and needs satisfaction (Haerens et al., 2015). Similar studies indicated that girls scored lower than boys in competence need satisfaction (Rodriguez-Meirinhos et al., 2019) as well as reported higher levels of relatedness need satisfaction and competence need frustration (Vandenkerckhove, Brenning, Vansteenkiste et al., 2019). Gender differences were also observed in students’ academic adjustment (Kiang, Supple, & Stein, 2012; Bugler, Mcgeown, & St Clair-Thompson, 2015; Marcenaro-Gutierrez, Lopez-Agudo, & Ropero-Garcia, 2018), social adjustment (Jèsus Cava, Musitu, & Buelga, 2010) and psycho-emotional adjustment (Hoffman, Powlishta, & White, 2009; Ahmad et al., 2013).

22

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

+ + + + + + + + + + + + + + +23

CHAPTER 3: THE MAURITIAN CONTEXT

3.1. The socio-demographic characteristicsSituated in the southwest of the Indian Ocean, Mauritius Island, the main island of the Republic of Mauritius, covers an area of 1,868.4 km2 and shelters an estimated resident population of 1,221,150 inhabitants (Statistics Mauritius, 2018). The native language spoken is Kreol and the official language used is English, although French is also widely spoken in school and work premises (Statistics Mauritius, 2018). Mauritius Island possesses a rich cultural diversity since its inhabitants are mainly descendants of slaves, indentured labourers and settlers from Africa, Asia and Europe. As of 1983, data about the ethnic groups’ population were no more collected for the population census due to the government’s resolve in promoting a common national identity and eradicating the communalist view bound to ethnic grouping (Hollup, 2004). Nevertheless, studies revealed that Mauritians from the main ethnic groups, i.e. Indo-Mauritians, Afro-Mauritians and Sino-Mauritians affirm a dual identity where both ethnic and religious identities coexist with a strong sense of national belongingness (Ng Tseung-Wong & Verkuyte, 2015).

3.2. The educational system

High quality education is viewed as one of the building blocks of Mauritius’ economic and social growth (Ministry of Education, Culture and Human Resources, 2009). As a result, throughout the years, governments have disbursed extensive funds in the implementation of educational programs accessible for all (Ministry of Education, Culture and Human resources, 2009). The aim was to train competent and highly skilled individuals from diverse fields who would integrate new sectors of the labour market and contribute to the economy. One of the main initiatives was the provision of free education from pre-primary to tertiary

24

level as from 1977 (Ministry of Education, Culture and Human Resources, 2009).

Before 2017, the Mauritian educational system was similar to the British system with six years of primary level. At the end of primary level, students were evaluated through the Certificate of Primary Education (CPE) examination; a highly competitive national examination which determined enrolment in secondary schools or colleges. Secondary education consisted of two levels; the lower secondary and upper secondary. The lower secondary level involved five years of study which would conclude with the School Certificate (SC) examinations, followed by two years of upper secondary education assessed by the Higher School Certificate (HSC) examinations. HSC graduates were subsequently eligible for admission at tertiary level.

As from 2017, the Ministry of Education and Human Resources, Tertiary Education and Scientific Research enforced a new educational reform known as the Nine Year Continuous Basic Education (NYCBE). This reform extended by one year the educational program as from Grade 7 for the inclusion and provision of support to low achievers from primary to secondary level. The NYCBE is illustrated in the Figure 2. As depicted in the new educational pathway, two major changes were implemented. Firstly, students no more compete for the national examination after six years of primary education but are rather assessed through the Primary School Achievement Certificate (PSAC) which produces a grade aggregate representing the sum of grades in the best four core subjects. Secondly, the National Certificate Education examination, which is a replacement to the CPE exams, is undertaken after 3 or 4 years (extended year) of study at the lower secondary level. The outcomes of this examination determine whether a student remains in a regional secondary school or is eligible for enrolment to one of the “academies”. Academies are secondary schools other than regional schools that are open for

25

admission as from Grade 10 to Grade 13. These schools are usually referred to as “star” colleges or institutions of excellence since they deliver the highest pass rate in HSC exams across the country. Among the 68 state schools and 135 private schools in Mauritius, 12 were designated as academies in the NYCBE.

26

Figure 2. New Educational Pathway. In NYS Brochure Secondary, Explaining the NYCBE Reform - The Secondary Sector. Ministry of Education and Human Resources, Tertiary Education and Scientific Research, Mauritius.

27

CHAPTER 4: METHODOLOGY

4.1. ParticipantsThe participants (N = 271; 53.1% girls) were Mauritian students (French-speaking) with a mean age of 15.5 years (SD = 1.15). Most of the students reported being of African origin (40.9%), living in urban areas of the island (74.9 %) and having siblings (86.9%). Most mothers completed their studies up to School Certificate (31.2%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sample. (N = 271)

Demographic variables n % Age Sex Boys 127 46.9 Girls 144 53.1 Ethnicity Afro-Mauritian 106 40.9 Indo-Mauritian 67 25.9 Sino-Mauritian 17 6.6 Franco-Mauritian 21 8.1 Mixed 5 1.9 Others 43 16.6 Residential area Urban 182 74.9 Rural 61 25.1

Mothers’ education level

CPE and lower 72 26.6

School Certificate (O-Level) and lower 89 32.8 Higher School Certificate (A-Level) and

lower 65 24

University Degree Level 25 9.2

Others 9 3.3

Family Structure

Only child 35 13.1

Has siblings 232 86.9

28 4.2. Procedure

The participants of this study were selected based on schools’ answer to an emailed call for participation. Two secondary schools, an all-boys school, La Confiance College and an all-girls school, Bon et Perpetuel Secours College, granted access to their premises. All students from Grade 10 and 11 from each school were approached. Students and their parents were both requested to complete and return consent forms. After both parties provided their consent, students were asked, during the first school semester, to fill in a questionnaire in their classroom during a free class period of 45 minutes, agreed and set beforehand with the school director and teachers. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Laval University.

4.3. Measures

4.3.1 Perceived mothers’ autonomy support.

Students’ perceived autonomy support from their mother was measured using the French version of the Perceived Parental Autonomy Support Scale (P-PASS; Mageau, Ranger, Joussemet et al., 2015). It is a 24-item scale which assesses the autonomy support vs controlling parenting component. In the present study, only the 12 items measuring the component of parental autonomy support were used. Three perceived autonomy supportive behaviours, notably choice (e.g., “My mother gives me many opportunities to make my own decisions about what I was doing.”), rationale (e.g., “When my mother asks me to do something, she explains why she wants me to do it.”) and acknowledgement of feelings (e.g., “My mother encourages me to be myself.”), were measured through 4 items each. Participants indicated to which extent they agreed on their mothers’ behaviours on a 7-point response scale, ranging from 1 (do not

agree at all) to 7 (very strongly agree). The scale scores were obtained by

adding up item scores with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived autonomy support from the mother. The internal consistency of

29

the P-PASS has been previously demonstrated (Mageau et al., 2015; Ratelle et al., 2017). The internal reliability obtained in this study was .86.

4.3.2 Perceived teachers’ autonomy support.

Students’ perception of their teachers’ autonomy support was measured using a shortened version of the P-PASS (Mageau et al., 2015). The items were selected based on the highest factor loadings they displayed in an unpublished pilot study. The scale consisted of 3 items from the dimension “choice” (e.g., “My teachers give me many opportunities to make my own decisions about what I was doing.”), 3 items from the dimension “rationale” (e.g., “When my teachers want me to do something, they explain to me why they want me to do so”) and 2 items from the dimension “acknowledgement of feelings” (e.g., “My teachers listen to my opinions and point of views when I don’t agree with them”). The students indicated the extent to which each item applied to them on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). The scale scores were obtained by adding up item scores with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived autonomy support from the teacher. In the present study, the scale’s internal consistency was .80.

4.3.3 Satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs. Students’ satisfaction and frustration of their basic psychological needs were assessed using the 24-item of the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (Chen et al., 2015). The scale is based on a 6-factor model (4 items each) notably satisfaction of the need for autonomy ( e.g., “I feel a sense of choice and freedom in the things I undertake”), relatedness (e.g., “I feel close and connected with other people who are important to me’) and competence (e.g., ‘‘I feel I can successfully complete difficult tasks’’) as well as the frustration of the need for autonomy (e.g., “I feel forced to do many things I wouldn’t choose to do”), relatedness (e.g., “I feel excluded from the group I want to belong to”), and competence (e.g., “I feel insecure about my abilities”).

30

Participants reported their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely false) to 5 (completely true). The scale scores were obtained by adding up item scores with larger scores indicating greater satisfaction or frustration of needs. In the Chen and colleagues’ study (2015), the Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.64 (relatedness frustration) to 0.88 (competence satisfaction). The Cronbach’s alpha for each factor in the present study is showed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Internal consistency of each factor in the satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs scale.

Factors Cronbach’s alpha (α)

Satisfaction

Need for autonomy 0.64

Need for competence 0.77

Need for relatedness 0.79

Frustration

Need for autonomy 0.64

Need for competence 0.77

Need for relatedness 0.78

4.3.4 School adjustment.

Students’ school adjustment was measured using the French (Larose et al., 1996) and high school-adapted version (Duchesne, Ratelle, Larose, & Guay, 2007) of the Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (SACQ; Baker & Siryk, 1989). It is a 24-item self-report scale comprised of three subscales: (a) academic adjustment, (b) social adjustment and (c) personal-emotional adjustment. The academic adjustment subscale consists of 10 items (e.g., “I have had trouble concentrating when I try to

31

study” ) which assesses students’ coping and interest to schoolworks. The social adjustment subscale consists of 7 items (e.g., “I have had difficulties feeling at ease with other people at school” ) which assesses students’ ability to engage and maintain healthy relationships with others. The personal-emotional subscale comprises of 7 items (e.g., “I haven’t been sleeping very well”) which assesses students’ psychological, emotional and physical state and coping. Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed to each item using a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (does not apply to me at all) to 9 (applies to me very well). The French version of the SACQ, adapted to the high school setting (Duchesne et al., 2007) demonstrated high internal reliabilities ranging from .72 to .82. In the present study, Cronbach’s alphas were .76, .69 and .67 for academic, social and personal-emotional subscales respectively.

4.4. Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted in four steps. First, datasets were screened for missing values and normality. Normality was screened by assessing the skewness and kurtosis of each variable. The second step involved preliminary analyses with the calculation of means, standard deviations and correlations as well as an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to evaluate the mean differences in all variables with respect to gender. Third, path analysis was performed on Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012) under robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR) to examine the relationships among the study variables and to test the mediation hypotheses. The proposed path model is illustrated in Figure 3. The mean scores of the observed variables from each measure were used as input. Three statistics were used to evaluate the goodness of model fit, notably the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; also known as the Bentler-Bonett non-normed fit index). A CFI and TLI close to or above .95, a SRMR close to .08 and an RMSEA less than .08 were

32

considered as indicators for a good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Browne & Cudeck, 1993). The fourth step involved bootstrap resampling method to compute standardized parameter estimates and assess the indirect effects within the model (Bauer, Preacher, & Gil, 2006; Marcoulides & Schumacker, 2013). In the present study, bootstrapping used 1000 resamples that were randomly selected from the original sample. The analysis involved the calculation of 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for each subsample around the product of the non-standardized path coefficients of the estimated indirect effect. Confidence intervals that do not include zero indicated significant indirect effects (Hayes, 2012).

Of the 271 participants, 233 had complete data. Missing values were investigated by performing the Little’s test (Little, 1988) on all the variables. The test is used to evaluate whether the pattern of missing data was completely at random (MCAR). The result was statistically non-significant, χ2 (7503,143) = 7623, p = .83, indicating that there was no

systematic pattern for missing data. Moreover, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was applied during the path analysis to impute missing values (Graham, 2003; Muthén & Muthén, 1998- 2012).

34

CHAPTER 5: RESULTS

5.1. Preliminary analyses5.1.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 3. presents the means, standard deviations and significant zero-order correlations of all variables. Mothers’ (r = .20; p < .01) and teachers’ autonomy support (r = .18; p < .01) were positively associated with students’ social adjustment only. Mothers’ autonomy support was also positively associated with the satisfaction of all three needs (r ranged from .17 to .29; p < .01) while significantly and negatively correlated to the frustration of the need for autonomy (r = -.25; p < .01) and relatedness (r = -.15; p < .05). Teachers’ autonomy support was positively associated with all needs’ satisfaction (r ranged from .13 to .20; p < .05). Unexpectedly, teachers’ autonomy support was significantly and positively associated with the frustration of the need for relatedness (r = .14; p < .05), suggesting that the more supportive were the teachers of their students’ autonomy, the least the latter felt connected with people or groups of interest. Academic adjustment was negatively correlated to all three needs’ frustration (r ranged from -.22 to -.50; p < .01) and was found to be significantly and positively correlated to competence satisfaction (r = .15, p < .05) only. Social adjustment was positively associated with all needs’ satisfaction (r ranged from .37 to .43; p < .01) while significantly and negatively correlated to the frustration of the need for competence (r = -.18; p < .01) and relatedness (r = -.41; p < .01). Finally, personal-emotional adjustment was shown to be negatively associated with the frustration of all three needs (r ranged from -.22 to -.45; p < .01). However, no association was found between personal-emotional adjustment and needs’ satisfaction.

35 Table 3.

Means, standard deviations and zero-order correlations of all study variables (N=271).

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1. MAS - 2. TAS .16* - 3. SaAut .29** .20** - 4. FrAut -.25** .05 -.12* - 5. SaRel .22** .19** .41** .02 - 6. FrRel -.15* .14* -.29** .32** -.33** - 7. SaComp .17** .13* .49** -.08 .35** -.12* - 8. FrComp -.09 .04 -.09 .22** .01 .26** -.21** - 9. AcAdj .08 .04 .05 -.27** -.10 -.22** .15* -.50** - 10. SocAdj .20** .18** .40** -.11 .43** -.41** .37** -.18** .08 - 11. PersAdj .07 .05 .09 -.22** -.10 -.27** .08 -.45** .65** .12 - M 4.98 4.18 3.89 3.21 4.05 2.47 3.87 3.26 4.29 6.58 4.50 SD 1.22 1.23 0.74 0.89 0.84 1.09 0.87 1.02 1.56 1.50 1.64 Scores range 1-7 1-7 1-5 1-5 1-5 1-5 1-5 1-5 1-9 1-9 1-9

Note. MAS= Mother autonomy support; TAS= Teacher autonomy support; SaAut= Autonomy Satisfaction; FrAut= Autonomy Frustration; SaRel= Relatedness Satisfaction; FrRel=

Relatedness Frustration; SaComp= Competence Satisfaction; FrComp= Competence Frustration; AcAdj= Academic adjustment; SocAdj= Social adjustment; PersAdj= Personal-emotional adjustment; M= Mean; SD= Standard deviation. * p < .05. ** p < .01.