© The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com. 580

doi:10.1093/fampra/cmw095 Advance Access publication 12 September 2016

Review

Quality of qualitative studies centred on

patients in family practice: a systematic review

Benoit Cambon

a,*

, Philippe Vorilhon

a,b, Laurence Michel

a,

Jean-Sébastien Cadwallader

c,d, Isabelle Aubin-Auger

e,f, Bruno Pereira

gand Hélène Vaillant Roussel

a,haDepartment of General Practice, Faculty of Medicine of Clermont-Ferrand, University of Auvergne, 63000

Clermont-Ferrand, France, bPerinatal period, Pregnancy, Environment, Medical Practices and Development

(PEPRADE), Clermont University, University of Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France, cINSERM U1178, University

Paris-Saclay, University of Paris-Sud, Villejuif, Paris, France, dDepartment of General Practice, Faculty of

Medicine Pierre and Marie Curie, Sorbonne Universities, UPMC University Paris 06, Paris, France, eDepartment

of General Practice, University Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, F-75018 Paris, France, fEA Recherche Clinique

Coordonnée Ville-Hôpital, Méthodologies et Société (REMES), F-75018 Paris, France, gBiostatistics Unit (Clinic

Research and Innovation Department), University Hospital Clermont-Ferrand, 63000 Clermont-Ferrand, France and hClinical Investigation Center, INSERM CIC 501, Ferrand University Hospital, 63000

Clermont-Ferrand, France.

*Correspondence to Benoit Cambon, Department of General Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Auvergne, 63000 Clermont-Ferrand, France; E-mail: benoit.cambon@udamail.fr

Abstract

Background. Qualitative research is often used in the field of general medicine. Our objective was

to evaluate the quality of published qualitative studies conducted using individual interviews or focus groups centred on patients monitored in general practice.

Methods. We have undertaken a review of the literature in the PubMed and Embase databases

of articles up to February 2014. The selection criteria were qualitative studies conducted using individual interviews or focus groups, centred on patients monitored in general practice. The articles chosen were analysed and evaluated using a score established from the Relevance, Appropriateness, Transparency and Soundness (RATS) grid.

Results. The average score of the 52 studies chosen was 28 out of 42. The criteria least often present

were the description of the patients who chose not to participate in the study, the justification of the end of data collection, the discussion of the influence of the researchers and the discussion of the confidentiality of the data. The criteria most frequently described were an explicit research question, justified and in relation to existing knowledge, the agreement of the ethical committee and the presence of quotations. The number of studies and the score increased from year-to-year. The score was independent of the impact factor of the journal.

Conclusions. Even though the qualitative research was published in reviews with a low impact

factor, our results suggest that this research responded to the quality criteria of the RATS grid. The evaluation scored using RATS could be useful for authors or reviewers and for literature reviews.

Key words: Focus group, general practice, individual interview, patients, qualitative research, review.

Introduction

Qualitative research from the humanities responds to the complex health issues with which GPs are confronted (1,2). It explores and describes phenomena that seek to explain and understand these issues. Unlike quantitative methods, which aim to bring proof con-cerning prevalence, prediction, causes or effects, qualitative research seeks to explain the hiatus that sometimes exists between scientifi-cally acquired data and the behaviour of care providers and those being cared for (1).

Qualitative research fits with current trends in medicine where humanistic and social aspects are again becoming important (3). The main techniques for collecting data used in the medical field are observation, individual interviews and focus groups (4–6). These techniques are particularly suitable for research in general medicine as they allow for medical complexity to be treated in real-life situ-ations, using an approach that is centred on the patient and reflects a bio-psycho-social model (6,7). These approaches allow for the exploration of numerous questions that GPs are confronted with concerning personal experience of the illness and the behaviour of the patients. Qualitative research has often been derided for a supposed lack of scientific rigor (8). It is, however, subject to the same quality requirements as quantitative studies: a pertinent line of research, transparent procedures, systematic data analysis and explicit communication (9–11). It is now accepted that these two types of research studies are complementary in the case of health care research and for the formulation of guidelines, notably in patient-centred care (12,13).

Scientific criteria specific to qualitative research have been devel-oped (14), in addition to guidelines, such as RATS scale (Relevance, Appropriateness, Transparency and Soundness) for writing and reading the studies (15), COREQ (Consolidated criteria for report-ing qualitative studies) (16), ENTREQ (Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research) (17) or SRQR (Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research) (9). There are still relatively fewer qualitative studies that have been published com-pared to quantitative research (18,19), although the number of such publications has increased considerably since 2000 (10). Few articles have analysed the quality of qualitative research articles, notably those concerning patients monitored in general medicine. Qualitative research with patients, as practiced by GPs, is useful however, as it is centred on the patient (13). It is a source of information for the GPs on representations of the illness or treatments, as well as on attitudes and behaviours of their patients (20).

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the methodo-logical quality of the published qualitative studies using individual interviews or focus groups of patients being monitored in general medicine. The secondary objective was to describe these publications.

Methods

Research strategy

Our study concerns qualitative studies using individual interviewing techniques, focus groups or a combination of the two, irrespective of the analysis method used. We limited these data collection techniques of data collection to interviews, as this is the method currently used in qualitative studies in general medicine. Two researchers conducted the literature review between November 2013 and February 2014. One of the researchers is a librarian in the Health Sciences Library at the University of Clermont-Ferrand (21). The PubMed via Medline and Embase databases were searched without start-date limits. We used following search formulae, combining the keywords:

qualitative research/interviews, structured interview, semi-structured interview, unstructured interview or focus groups/general practice or GPs or family practice or family physicians/patients, patient.

Selection of studies

The first step in study selection was to read the title and the abstract of the article. For the articles retained, a second step was performed by reading the full text. Four researchers participated in the selection of the articles. The researchers were distributed into three teams of two researchers, where each of the other researchers worked as a team with LM (LM–BC, LM–HVR and LM–PV). Each team read a third of the total number of articles identified at the start. The two researchers on the team independently read the title and the abstract, followed by the full text of each article. Disagreements were then resolved by discussion between the two researchers until a consensus was reached. If a consensus was not reached, the opinion of a third researcher was required.

The criteria for inclusion were as follows:

• Studies published in English referenced in the PubMed or Embase databases;

• Qualitative method using individual interview or focus group; • Some or all of the subjects studied are patients;

• Some or all of the subjects are recruited in a general medicine office;

• The theme of the study is patient centred.

Processing of an evaluation score

No evaluation grid for qualitative studies has been found in the liter-ature, and thus, a quality score was developed from the first 21 items of the RATS grid (15). The last item of RATS grid (‘Are red flags present?’) was not retained as it was non-discriminating. Each item was scored from 0 to 2 depending on the presence of the item in the article: 0 (absence of description), 1 (partial description) and 2 (com-plete description). The total maximum score was 42 (Supplementary Table S1).

Analysis of methodological quality of the studies

Having made the selection, three groups (LM–BC, LM–HVR and LM–PV) performed an analysis of the articles selected. Each group was given one-third of the articles. The two researchers in each group independently scored the article. A meeting between the evalu-ators following the analysis of five articles allowed for an agreement to be reached on the method of scoring the articles. The results were then compared and discussed. In the case of a disagreement that was unresolved through a discussion between the two researchers, the opinion of a third researcher was sought.

Statistical analysis of the results

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata software, version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The tests were two sided with Type I error α at 0.05. Study characteristics were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, according to statistical distribution (nor-mality assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test), and as the number of studies (%) for categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were performed using chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categori-cal variables and ANOVA (Analysis of variance) or Kruskal–Wallis tests if assumptions of ANOVA did not meet [(i) normality and (ii) homoscedasticity], as studied using the Bartlett test for quantita-tive parameters. Analyses of the relationships between quantitaquantita-tive

parameters (for example, total score and impact factor or publica-tion year) were studied using the correlapublica-tion coefficient r (Pearson or Spearman, with regard to the statistical distribution).

Results

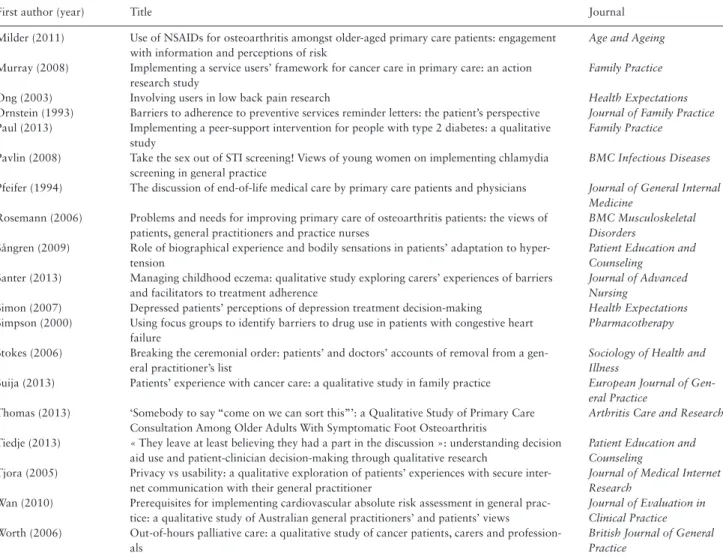

The researchers identified 620 references: 221 on PubMed and 399 on Embase. Following the two steps for selection by reading the title/abstract and then the full text, 52 studies met inclusion criteria (Fig. 1; Table 1).

Methodological quality of the studies

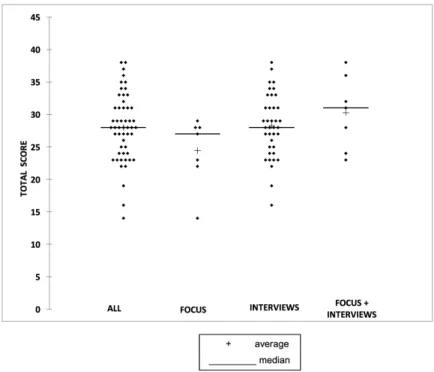

The average total score was 28 (±5.2) and 50% of the values were situated between 24 and 31 (Figure 2). The average of the scores was higher for studies conducted using individual interviews than for studies using focus groups, and higher again for studies combin-ing individual interviews and focus groups, but the difference was not statistically significant.

The analysis of the scores for each item in the RATS grid allowed for determining the methodological weaknesses of the studies (Supplementary Table S1). Certain items that were rarely described or absent in the articles (majority of score 0) are as follows: • A description of the characteristics of patients who chose not to

participate in the study and their reasons.

• A description and justification of the end-of-data collection. • A discussion of the influence of the researchers on the

formu-lation of the research question, the collection of data and the interpretation of results.

• A discussion of anonymity and confidentiality of the data. The items the most frequently described in the articles (majority of score 2) were as follows:

• Explicit research question;

• Justified research question and relationship to existing knowl-edge;

• Agreement with the ethical committee mentioned; • Presence of appropriate and valid quotations; • Article well-written and clear.

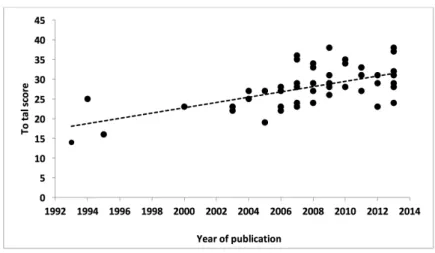

Pure qualitative studies obtained a higher score than did studies combining qualitative and quantitative methods (28.8 ± 5.1 versus 25.4 ± 4.9, P = 0.048). The studies chosen were published between 1993 and 2013. An increase in the number of publications over time was observed (Figure 3). There was a correlation between the total score obtained by each study and the year of publication. The total score increased from year-to-year (r = 0.53, P < 0.001) (Figure 4). The studies published prior to 2003 (year of publication of the RATS checklist) had an average score of 20.5 (±4.4) versus 29 after 2003 (±4.5) P < 0.001. The score was analysed as a function of the impact factor of the journal. There was no correlation between the total score obtained by each study and the impact factor of the journal in which it was published (r = 0.20, P = 0.21).

Description of the studies

The collection of data was done via individual interviews in 38 studies (73%), via focus groups in 7 studies (13.5%), and using a combined individual interview and focus groups method in 7 studies (13.5%). About 40 studies (76.9%) employed a pure qualitative method and 12 studies (23.1%) used a qualitative method combined with a quantita-tive method. Among the 52 studies chosen, 42 were published in jour-nals having an impact factor. The average impact factor was 1.7 (±0.7)

and 50% of the studies were published in journals with an impact factor of between 1.6 and 1.9. The sample was composed exclusively of patients in 26 studies (50%). There was a significant relationship between the total score obtained by each study and the composition of the sample. The average total score was 29.1 ± 6.1 when the subject of the study was exclusively patients, while it was 27 ± 3.9 when the subjects were patients and health professionals (P = 0.04).

The most frequent themes among the studies chosen were the doctor–patient relationship (13 studies), followed by chronic ill-nesses (11 studies), prevention (8 studies), therapeutics (7 studies), end of life (4 studies), organization of care (3 studies), quality of life (3 studies) and medical research (3 studies). About 23 studies (44.2%) were published in a general medicine journal, 11 studies (21.1%) in a general journal and the remaining 18 studies (34.6%) in different specialized journals. The general medicine journals that published the largest number of qualitative studies were Family

Practice (six studies), British Journal of General Practice (five studies)

and BMC Family Practice (four studies). With 20 studies (38.5%), the British research groups seem to publish the greatest number of qualitative studies (USA, six studies; Australia, five studies; Belgium, Canada, Denmark and Ireland, two studies; Spain, Estonia, Norway and the Netherlands, one study). The profession of the authors could be determined for 50 of the 52 studies chosen, and 42 studies (84%) were published by a research group consisting of one or several GPs.

Discussion

The principal results

Our review of the literature allowed us to evaluate the quality of 52 pub-lished qualitative studies on patients of GPs, using individual interviews Figure 1. Flowchart of study selection

or focus groups, published between 1993 and 2013. The average score of the 52 studies using RATS grid was 28 out of 42. The criteria most frequently described were an explicit research question, justified in rela-tion to existing knowledge, the agreement of the ethical committee and the presence of quotations. The criteria least often present were the description of the patients who chose not to participate in the study, the justification of the end-of-data collection, the discussion about the influ-ence of the researchers and the discussion about the confidentiality of the data. The number of publications and their quality increased from year-to-year, particularly after 2003. The evaluation score was highest when the studies only dealt with patients. There was no relationship between the quality of the study and the impact factor of the journals.

Interest in a scoring tool

Previous researchers have proposed evaluation criteria for assess-ing methodological quality of qualitative publications, but they did not propose an evaluation score. Our scoring tool was created for this study, making comparisons with similar publications difficult.

Hoddinott’s review of the literature, which evaluated the methodo-logical quality of published qualitative studies in general medicine that used interviews (individual or group) of patients or GPs, was published in 1997 (22). The 29 studies in that paper were chosen over a period of 4 years, and analysed with 8 general criteria with binary scoring.

We found only one review which used the RATS grid which was a review by Siddiqui concerning qualitative articles on urinary inconti-nence in women (23). The 23 studies listed were classified into 3 cate-gories (high quality, moderate quality and low quality) as a qualitative assessment of the RATS methodological criteria. The results are dif-ficult to compare with ours because of the different populations and different scoring systems used. Our tool offers a finer analysis, with 22 criteria assessed each with a score of present/absent/intermediate.

Correlation between the score obtained and the impact factor

In our study, there was no correlation between the score obtained by each study and the impact factor of the journal in which it was published. The Figure 2. Distribution of total score of studies by the method

Figure 3. Evolution of number of studies by the publication year

impact factor is, therefore, not a pertinent criterion for evaluating the quality of a qualitative article. Several studies have also reported this dissociation between the impact factor and the quality of quantitative research (24–26). Our review is the first to describe this relationship for qualitative research. The studies chosen were published in journals hav-ing a rather low impact factor. It is possible that qualitative research has difficulty being accepted by high-impact factor journals, even though the studies have a high-quality score. It should also be reported that general medicine journals have a rather low impact factor overall.

Criteria of quality

It is probable that the growing number of directives concerning the writing of qualitative articles (such as RATS) favours the quality of these articles, as is the case for quantitative research assessed using the STROBE (The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) or CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) grids (27). The same four criteria obtained the low-est scores in Hoddinott’s and Siddiqui’s studies, as well as in Carlsen’s research on focus groups (22,23,28). This underlines the requirement for clarification of these four items in the reporting guidelines of pub-lications. For example, the article should describe how patient confi-dentiality and data anonymization will be ensured when obtaining the patient’s consent. Researchers should also report the number of inter-views that give no new data (saturation). The researcher should dis-cuss how his position has influenced the participants and the analysis. Other items were present in the majority of studies (article well-written and clear, a clear and justified research question and speci-fied approval from the ethical committee). This result was relatively predictable as these are required criteria for the publication of all research work, qualitative or not. The quality score was lowest when the study sample was not exclusively comprised of patients, and was also low in mixed studies combining qualitative and quantita-tive methods. The quantity of information to present in the article, perhaps, did not allow the researcher to describe the study in more detail, which could explain a lower score for the items concerned.

The majority of studies used individual interviews as the data collection method. This method is probably the most familiar to GPs as it corresponds to the dual relationship that they have already mastered in their consultations. The focus group, requiring organ-izational and leadership skills, is the most difficult to implement. Individual interviews are also easier to organize in a doctor’s office or at the patient’s home. The use of both data collection methods in the same study was rare, yet this triangulation of methods allows for improvement of the internal validity (11).

Strengths and limitations

This is an original work, without equivalent identified in the litera-ture. The methodological rigor of the selection and the scoring of articles by independent researchers, seeking consensus in cases of disagreement and the opinion of a third researcher when consensus could not be reached, provided a more reliable selection of articles. Discussions between the evaluators after five articles were analysed and allowed for the subjectivity of the scoring to be limited.

The RATS grid served as a support for our evaluation grid, with a score given out of a total possible score of 42. The RATS grid was chosen since it is the most frequently used in general medicine. The COREQ grid is used more often by social anthropology groups.

Our research was limited to the PubMed and Embase databases. This can represent and limit the exhaustiveness of the research. The analysis of other databases, such as Psychinfo or Sinacle, would have provided a more exhaustive search. The research was limited to the publications using individual interviews and focus groups as the data collection method. Other articles that used methods such as observa-tion or narrative were, therefore, not analysed. Another limit of the study was the inclusion of publications written only in English. Some methodological data could not be retranscribed into the article for fear of conciseness. Our study is an indirect means to evaluate the quality of qualitative studies.

Implications for practice

What do we learn for our practice from this review of the literature? The RATS grid was developed to improve qualitative studies using focus groups and individual interviews. The RATS score allows a critical reading of qualitative research articles. The RATS score can help generate a quantitative evaluation according to different aspects of the study (context, method, finding, analysis and interpretation). We suggest that researchers use this tool at three stages of the study to improve the study’s quality:

• Before the study: list the RATS quality criteria and implement them in the study design.

• During the study: check the RATS quality criteria at all steps of the study.

• Before submission: score the study with the RATS grid and reword items that have scored 0 or 1.

This procedure will limit missing criteria and prompt discussion if necessary. Using this procedure, the quality of qualitative work and its chances of being published will be improved. This tool could also be useful for journal reviewers as a means of scoring an article, Figure 4. Evolution of total score by the publication year

Table 1. The 52 qualitative studies

First author (year) Title Journal

Aubin-Auger (2011) Obstacles to colorectal screening in general practice: a qualitative study of GPs and patients

Family Practice

Bane (2007) The journey to concordance for patients with hypertension: a qualitative study in pri-mary care

Pharmacy World and Science

Beattie (2009) Primary-care patients’ expectations and experiences of online cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: a qualitative study

Health Expectations

Berkelmans (2010) Characteristics of general practice care: what do senior citizens value? A qualitative study

BMC Geriatric

Boggis (2007) General Practitioners with special clinical interests: a qualitative study of the views of doctors, health managers and patients

Health Policy

Borgsteede (2007) Communication about euthanasia in general practice: opinions and experiences of patients and their general practitioners

Patient Education and Counseling

Burton (2011) The interpretation of low mood and worry by high users of secondary care with medi-cally unexplained symptoms

BMC Family Practice

Calderón (2011) Health promotion in primary care: how should we intervene? A qualitative study involv-ing both physicians and patients

BMC Health Service Research

Chew-Graham (2009) Disclosure of symptoms of postnatal depression, the perspectives of health professionals and women: a qualitative study

BMC Family Practice

Clerkin (2013) Patients’ views about the use of their personal information from general practice medical records in health research: a qualitative study in Ireland

Family Practice

Dicker (1995) Patients’ views of priority setting in health care: an interview survey in one practice British Medical Journal

Dickinson (2010) Long-term prescribing of antidepressants in the older population: a qualitative study British Journal of General Practice

Ellis (2004) Patients’ views about discussing spiritual issues with primary care physicians Southern Medical Journal

Emmett (2012) Acceptability of screening to prevent osteoporotic fractures: a qualitative study with older women

Family Practice

Farber (2003) Issues in end-of-life care: patient, caregiver, and clinician perceptions Journal of Palliative Medicine

Fung (2009) A qualitative study of patients’ views on quality of primary care consultations in Hong Kong and comparison with the UK CARE Measure

BMC Family Practice

Goyder (2009) Informed choice and diabetes screening in primary care: qualitative study of patient and professional views in deprived areas of England

Primary Care Diabetes

Greenwood (2011) Perceptions of the role of general practice and practical support measures for carers of stroke survivors: a qualitative study

BMC Family Practice

Griffiths (2014) Case typologies, chronic illness and primary health care Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice

Harrison (2012) Are UK primary care teams formally identifying patients for palliative care before they die?

British Journal of General Practice

Hickner (2007) Physicians’ and patients’ views of cancer care by family physicians: a report from the American Academy of Family Physicians National Research Network

Family Medicine

Johnston (2007) Qualitative study of depression management in primary care: GP and patient goals, and the value of listening

British Journal of General Practice

Jones (2012) Patients’ experiences of self-monitoring blood pressure and self-titration of medication: the TASMINH2 trial qualitative study

British Journal of General Practice

Kehler (2008) Cardiovascular-risk patients’ experienced benefits and unfulfilled expectations from preventive consultations: a qualitative study

Quality in Primary Care

Lacy (2004) Why we don’t come: patient perceptions on no-shows Annals of Family Medicine

Magin (2009) The psychological sequelae of psoriasis: results of a qualitative study Psychology, Health and Medicine

Martin (2005) Non-attendance in primary care: the views of patients and practices on its causes, impact and solutions

Family Practice

Meyer (2012) Does prognosis and socioeconomic status impact on trust in physicians? Interviews with patients with coronary disease in South Australia

British Medical Journal Open

Meyfroidt (2013) How do patients with uncontrolled diabetes in the Brussels-Capital Region seek and use information sources for their diet?

Primary Health Care Re-search and Development

Michiels (2007) The role of general practitioners in continuity of care at the end of life: a qualitative study of terminally ill patients and their next of kin

Palliative Medicine

Miedema (2006) Young adults’ experiences with cancer: comments from patients and survivors Canadian Family Physician

Mikkelsen (2008) Cancer rehabilitation: psychosocial rehabilitation needs after discharge from hospital? Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care

Mikkelsen (2008) Cancer surviving patients’ rehabilitation—understanding failure through application of theoretical perspectives from Habermas

BMC Health Services Research

giving them as a list of objective quality criteria. This score could be used as an evaluation tool for literature reviews on qualitative research.

Conclusion

This work is the first methodological review of published qualitative studies using individual interviews or focus groups of patients moni-tored in general practice. This review showed that the number and quality of this type of qualitative study have constantly increased year-by-year. However, our review also showed that progress needs to be made in the following criteria: description of the patients who chose not to participate in the study, justification of the end-of-data collection, discussion of the influence of the researchers and discus-sion of the confidentiality of the data. The use of scoring tools from the RATS grid used for this study would be useful to authors or reviewers and would further improve the reliability of publications. It can also be useful for literature reviews. It is now necessary to validate this tool for this purpose.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Family Practice online.

Declaration

Funding: none. Ethical approval: none. Conflict of interest: none.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Mrs Nathalie Pinol-Domenech, Librarian at the University Library of the faculty of Medicine of Clermont-Ferrand for her contribution to the review of the literature.

References

1. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines.

Lancet 2001; 358: 483–8.

2. Côte L, Turgeon J. Comment lire de façon critique les articles de recherche qualitative en médecine. Pédagog Méd 2002; 3: 81–90.

3. Fantini B, Lambrichs LL. Histoire de la pensée médicale contemporaine - evolutions, découvertes, controverses. Le Seuil, 2014: 531.

4. Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an intro-duction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ 1995; 311: 42–5.

5. Aubin Auger I. Introduction à la recherche qualitative. Exerc Rev Fr

Médecine Générale 2008; 84: 142–5.

First author (year) Title Journal

Milder (2011) Use of NSAIDs for osteoarthritis amongst older-aged primary care patients: engagement with information and perceptions of risk

Age and Ageing

Murray (2008) Implementing a service users’ framework for cancer care in primary care: an action research study

Family Practice

Ong (2003) Involving users in low back pain research Health Expectations

Ornstein (1993) Barriers to adherence to preventive services reminder letters: the patient’s perspective Journal of Family Practice

Paul (2013) Implementing a peer-support intervention for people with type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study

Family Practice

Pavlin (2008) Take the sex out of STI screening! Views of young women on implementing chlamydia screening in general practice

BMC Infectious Diseases

Pfeifer (1994) The discussion of end-of-life medical care by primary care patients and physicians Journal of General Internal Medicine

Rosemann (2006) Problems and needs for improving primary care of osteoarthritis patients: the views of patients, general practitioners and practice nurses

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders

Sångren (2009) Role of biographical experience and bodily sensations in patients’ adaptation to hyper-tension

Patient Education and Counseling

Santer (2013) Managing childhood eczema: qualitative study exploring carers’ experiences of barriers and facilitators to treatment adherence

Journal of Advanced Nursing

Simon (2007) Depressed patients’ perceptions of depression treatment decision-making Health Expectations

Simpson (2000) Using focus groups to identify barriers to drug use in patients with congestive heart failure

Pharmacotherapy

Stokes (2006) Breaking the ceremonial order: patients’ and doctors’ accounts of removal from a gen-eral practitioner’s list

Sociology of Health and Illness

Suija (2013) Patients’ experience with cancer care: a qualitative study in family practice European Journal of Gen-eral Practice

Thomas (2013) ‘Somebody to say “come on we can sort this”’: a Qualitative Study of Primary Care Consultation Among Older Adults With Symptomatic Foot Osteoarthritis

Arthritis Care and Research

Tiedje (2013) « They leave at least believing they had a part in the discussion »: understanding decision aid use and patient-clinician decision-making through qualitative research

Patient Education and Counseling

Tjora (2005) Privacy vs usability: a qualitative exploration of patients’ experiences with secure inter-net communication with their general practitioner

Journal of Medical Internet Research

Wan (2010) Prerequisites for implementing cardiovascular absolute risk assessment in general prac-tice: a qualitative study of Australian general practitioners’ and patients’ views

Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice

Worth (2006) Out-of-hours palliative care: a qualitative study of cancer patients, carers and profession-als

British Journal of General Practice

Table 1. Continued

6. Johansson EE, Risberg G, Hamberg K. Is qualitative research scientific, or merely relevant? Research-interested primary care and hospital physi-cians’ appraisal of abstracts. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003; 21: 10–4. 7. WONCA Europe. The European Definition of General Practice/Family

Medicine. 2002. http://www.woncaeurope.org/gp-definitions

8. Mays N, Pope C. Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ 1995; 311: 109–12. 9. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for

reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med

J Assoc Am Med Coll 2014; 89: 1245–51.

10. Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med 2008; 6: 331–9. 11. Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in

qualitative research. BMJ 2000; 320: 50–2.

12. Malterud K. The art and science of clinical knowledge: evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet 2001; 358: 397–400.

13. Britten N. Qualitative research on health communication: what can it con-tribute? Patient Educ Couns 2011; 82: 384–8.

14. Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual

Life Res 2009; 18: 1263–78.

15. Qualitative Research Review Guidelines. RATS | The EQUATOR Network [Internet]. http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/qualita-tive-research-review-guidelines-rats/ (accessed on 16 September 2015). 16. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting

quali-tative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–57.

17. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transpar-ency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC

Med Res Methodol 2012; 12: 181.

18. Shuval K, Harker K, Roudsari B et al. Is qualitative research second class science? A quantitative longitudinal examination of qualitative research in medical journals. PLoS One 2011; 6: e16937.

19. Gagliardi AR, Dobrow MJ. Paucity of qualitative research in general medi-cal and health services and policy research journals: analysis of publica-tion rates. BMC Health Serv Res 2011; 11: 268.

20. Stoffers J. Research priorities in family medicine. Eur J Gen Pract 2011; 17: 1–2.

21. Rethlefsen ML, Murad MH, Livingston EH. Engaging medical librarians to improve the quality of review articles. JAMA 2014; 312: 999–1000. 22. Hoddinott P, Pill R. A review of recently published qualitative research in

general practice. More methodological questions than answers? Fam Pract 1997; 14: 313–9.

23. Siddiqui NY, Levin PJ, Phadtare A, Pietrobon R, Ammarell N. Perceptions about female urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J 2014; 25: 863–71.

24. Sculier JP. Good and bad uses of the impact factor, a bibliometric tool. Rev

Med Brux 2004; 25: 51–4.

25. Metze K. Bureaucrats, researchers, editors, and the impact factor: a vicious circle that is detrimental to science. Clinics (São Paulo) 2010; 65: 937–40.

26. Seglen PO. Why the impact factor of journals should not be used for evalu-ating research. BMJ 1997; 314: 498–502.

27. Cobo E, Cortés J, Ribera JM et al. Effect of using reporting guidelines dur-ing peer review on quality of final manuscripts submitted to a biomedical journal: masked randomised trial. BMJ 2011; 343: d6783.

28. Carlsen B, Glenton C. What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011; 11: 26.