r

econflict

a

n arch

itectu

re

o f

i

n c a r c e r a t i o n

MAR

2 61991

Dedicated to Mom, Dad, Heather, and Wendy, with love.

Special thanks to Fernando Domeyko, Senior Lecturer in Architecture, for serving as advisor,

and to Ann Pendleton-Jullian, Associate Professor of Architecture,

and Standford Anderson, Head of the Department of Architecture,

for serving as readers to this thesis.

e

17

-.

Culture/Conflict/Colors: An Architecture of Incarcer tion

by Robert Matthew Noblett

Cameron's [Missouri] prison, its second, will open in February, tucked out of sight, just off the main road to town, near a Wal-Mart.

With its cluster of rambling, green roofed buildings, it resembles a junior

college more than the maximum-security prison that it is. Gone are the

traditionalfortress-like stone walls and guard towers. In their place will

be a lethal electricfence and motion detectors.

-The Boston Sunday Globe

October 13, 1996

Crime-fighting has become one of the fastest growing industries in the United States. Consequently, the construction of facilities which serve as the end-product of that fight, prisons, has become one of the nation's fastest growing industries as well.

The architecture of those facilities, which logically would fall

somewhere in the middle, has yet to catch up.

The intention of this project is to begin to explore the possibility for architecture within the context of the prison. It investigates ideas of space-making within a building which combines programmatic complexity with a requirement for security and control. It addresses notions of individual versus collective within the culture of the prison. It questions the relationship of the public to the imprisoned, of outside to inside.

Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial

fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Architecture at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology - February 1997.

Acknowledgments

0 -E

fig. 7a: final model

r~)

0

IICb

-I

6-7Author's

note

of office-building style spaces that simply fulfill a programmatic requirement. Lastly, a preoccupation with the wall, its possibili-ties and implications, found itself in this project, something unavoidable in a discussion of the prison.

-site plan courtesy City of Boston, Massachusetts.

000

The project is situated in Boston, Massachusetts at the confluence of the Longfellow Bridge, Cambridge Street, Charles Street, and Storrow Memorial Drive, at the end of the northern side of Canibridge Street.

v-4 -L

The site, mea the north-so General Hos wraps up to These two si chamfered s station. A si both the east northern and scale of move The northeas of the hospit

for the purposes of this project was erased. Less than one mile north along the river is the location of the recently constructed Suffolk County Jail, the replacement facility for the Charles Street Jail.

Lert

Program

1. Inmate Housing: (200) cells common spaces showers housing offices multi-use spaces segregated/difficult inmate housing 2. Dining Service: kitchen dining space storage 3. Medical Facilities administration diagnostic pharmacy outpatient dental storage inpatient care mental health 4. Education classrooms library workshops 5. Recreation outdoor recreation indoor recreation canteen storage 6. Visitation common visitation private visitation 7. Administration offices conference room hearing room control center 8. Chapel 0 0c .UJThis project is best understood as the

O

gathering up of several strands of

thought concerning the manner in

w .itecture for man body.

es mn

problem can ason that of approach,ng of the

yand the

h springs up orn here thata desire to

ee

mena which

pe, to beginto

'to the

there exists relation-inhabitants culture that ething that earchers ly has been and women large groups origins of the contemporary situation lie in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The trends leading up to thefig. 15b: cell model

twentieth century prison have been examined in depth by the likes of Sir Robin Evans in The Fabrication of

lish Prison

itectire

1750-18 aelIgnatieff in A

Just

re of Pain: The Penitentiary in the

ustrial R volution 1750-1850, and by

Michelfoufault in Diine andPunish: T Birth of the Prison.

These s outite the origins of punishment and trace the eventual aceptance and evolution of the prison.4 oucault desribesheshift

in p hment away IO trfro ild and p ent of theb

edyto'+e

c

and punishment of emintel

this o thentr

n be

ngein 1791 of

P. taicon, both as mo

f

ti ideal n as well as a con t deeply robted in ad surveillance ciety. As

Fou t

sees

it, thes ts set thestage or tlhstead dpment of the

*

~%

tio of t.

ough the

nineteen ntiet enturies. As

methods oa

e

becamerfd d so too was

S$a'ped

'reo

ulture within.

Although researchers felt that up through very recently a prison culture was identifiable and indeed

necessary to the operation of such an

0o

institution, the contemporary condi-tion has cast doubts over this nature of

rison Yer and

r

y mvre

v

oler

offendersave aisru h sqC of this

ulture an 4 respect of

e senior or O ffenders,

4n etman for

nsel co stering the

owtho

pis unclear

whether the pnson gngs have their

minsU the t c an o prevalent

najr i cities or in

cu5tu divisions within

prion seems clear is

that th tr e more or

less "tu culture e prison to

one Ose at frontational

1 g

has

he face ofqI

te nsi Arcing thosev tion and

h

n to

reevaluatedf ac by which

c era off C r .unt, 1993).

T thre extends

mate culture th t c&lu 1e role of the

prison official as part of prison culture as a whole. Because, as Sykes and Messinger point out, "the conditions of

Z

-o

0 fig. 19b

E fig.

19c

custody involve profound attacks on the prisoner's self-image or sense of personal worth," the desire or need to

-worth has

e to the

ich the roles

n this system of one'e

kes, 1960,

r write that rs moves m itcy as demanded rte pains ofniso

eess severe... A

ovides the

I group with

ch self and

w

h,

iu

n his struggles

ir

his condemniers. (Sykes, 1960,

16). nit toreiteing the

niddle wof D the oppiro was

thsin n posed to the stablishment

'of the

*on of

Any

riso

rticipate mn

his

osition to t

>lishment

.iimi/herself

d entirely

cutueof

r fellow

e~ffM

rom- the

opportunity to be reinvested with a

sense of worth. Despite the opposition

establish-a)

0

N > }

fig. 21b

fig. 21C

ment of officials in the prison, it was this unification of the prisoners within this culture which led to relative

By avoiding cials of the ble to secure cy to their status quo mnmate chieving this d seem that .ff ngs in the

k IS, es the unity

ey are placed er, placing

t

ary element n he ovea sche tis reduced toYt nolence

Compound-w tuency of

n

Yng'

e tig fromdi. be :dade real or

e m t oyalty to the ,but

so tygangs

3ilyndgFranteed.

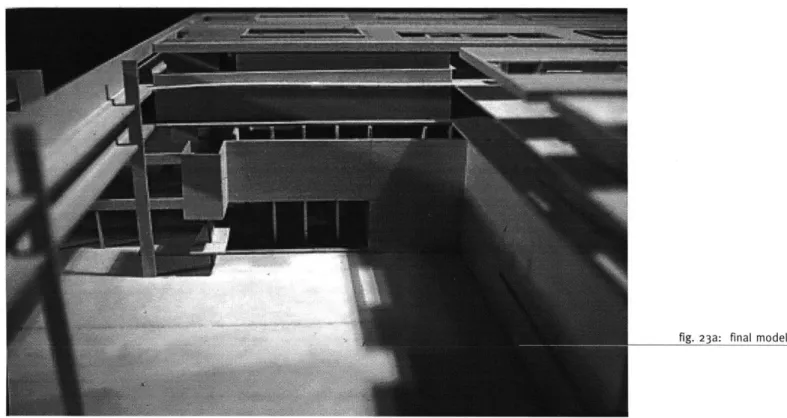

gh "iW reiaididivided as to what this new incarnation of prison culture means to the operation of these institutions, it seems clear that it has led

MV

N

CN

fig. 23a: final model

to increased violence and deep-seeded uncertainty among both prisoners and prison officials alike. The widely held

n., -. .o . presence of

tion, but

presence ofth one

asier to

maintain that ne another se they don'tv

-tofight wit

e guards

nt, 1993).

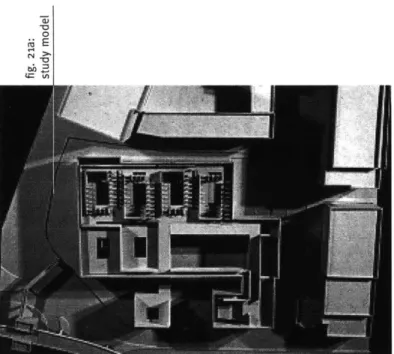

Architituially,'the project is about the

y hich one goes a out

con-struetmng space whigh'oranizes the pris *fulture. This implies

under-stan~if5 ,n eractipp 4f the internal culi Mswellie spee of the

vidual owd" th turn

impacts;i~e peiohe building

in ters. of rdfigtaitionally

architecture of the prison. It quickly became clear that there are essentially two stategies operating within the project. The first

.n N 1. recreation 2. workshop/ machine shop 3. works ho p/ storage 4.

laundry/

storage 5. vehicle sally port6. public lobby 7. open space -- L -121 3 4 5 iL L 10

8R

:

9A

---8. administration 9. education

10. chapel support spaces

77N

strategy began with the study of the

ao

cell, at the scale of the individual as well as of several individual cells

I g advantage

ofspat4I opportaftitie ' eths

Jagely it oode

exp of the way i hc h

bcteiatially related

by involves

the otioe element

ne has become

IPA

e, sy h O~ca laer~ hhseparates

tIp recognized by

inside frof 'outside I

tliegnate asthtwithr, ht Whi olds him-i

aartfroerstood by

ely contains olte ands

irnan fw panding the

thi knwhicht the

~

ight, andlending to the institution a sense of permanence. My models of the wall as

17. counseling rooms

18. common visitation

19. medical facilities/pharmacy

20. long-term property storage

21. prisoner intake

22. warden's apartment

23. classrooms

11. private visitation

12. open to below

13. guard changing area 14. guard dining and lounge

15. administration

16. education

fig. 29b: third level plan

fig. 29a: second level plan

fig. 31a: longitudinal building section

interested in the wall as something very free in its ability to wrap the building, yet suggest that the condition of being

-..-. .- f"- s t so much a terior but a

17

-11wall

you

p int 6project is the

u o strategies. ersion, cells s round three ce, served by

c

6 urth side. acent cell larger spatial anization of groundspatia strategy

oundary condition of the

bu i cr al 9

45

tounder-stan

e f utopianosi .building's

t cit 'te- n, that is

On the wall.

bt ch

conceptu-een e two

strategies becomes the circulation of the building. The traditionally centralized position of the guards is

24. kitchen

25. double bunk cells

26. dining hall

27. chapel

28. roof garden

here moved to the perimeter of the building, literally inverting the Panop-tic ideal. It wraps the collection of cell

blocks, an e of the

buildig

r movement

fpriso the various levels

ft eulding. oQtermost layer

tion

exerts specific contro M ighou e building bymeans

maller fingers-of circulation nove frornihe oter layer into the hea th41h ding. Theplace-mFent

bl

s sets up the greater pattern of circ ation aroundthe eRU i as movement

between cks. in turn

liberates the rior w f the

buildingi from responsibili as a

physical barrier, allowing it to define ns d ) eas a Viction of its

ot

aye iin "ayer. TheW :ely

rA

ing. As oneove ro mbrid treet toward

e

m

psace, On experiencest

ii

fh

s it turnso ce the library.

Cr A is exposed

0 in the "int o 'Pen space, where one is literally within the prison

wall.

The intention of the facades

LA

E

3

1

32L33

30. single bunk cells

31. open to chapel below

32. open to library below

of the building is to suggest this liberation of the prison wall by articulating its lightness and allowing a

g .interior of iterally hung rete slabs

ground.

are made f reducing surface area,on of the

ou

1eb~

.,f

It

investi-nes

of moving - d and of uestioning or "outside" the various two levels inin o rows of

hese blocks e open spacellc

exf

the

soutnern

northeast. above the er datum of the building and to create space below for the other programmatic elements of the building. The cells are located atfig. 37a: final model view into public lobby from "inside" open space

36-

37

the uppermost layer of the building, each with a window to the sky and organized around the large spaces

p r he building.

C de" of

builA4 ily to the

sky comes a layer

media.

ground,

allowi t annected at

once

e

at tfsame timeetaced in an independent floating "city.

*arc

ce1bock contains

18cell per teI onl he sices of an

ext or v'vhic rings light, air,

and space into the b ,ihg. These

# light ells penetrate thrgh the entire section of tie buildingllowing the

e

r's

e bilding to beboth lit from above, an connected to ground and sky. On the fourth side of the open space are the collective activities, which consists of a double height day room, exercise facilities, and showers. Cells on the lower level of the cell block are double bunk units, and are four feet greate in length than

those above. This ltdvs for the

placement of a window at the end of the cell, bringing in light and creating a view to the sky. Upper level cells arefig 34b: north elevation study

ON

0f

fig. 39a: final model

smaller, single bunk units also with an opening at the top of the cell. Circula-tion within the cell block is maintained etween the ister style. in constant and sky, to their tio intense tal layers of e bu nish the aditional S ig I a n

environ-wee thegoned body is not

ith the confined

ties.for co

ing and

iIo eve of the

blca end ofthe

bidn'These are; lctd in close

proimty ohecel tofcilitate

sm berso general rsiipoulation as well1 as to faciliae cl ltigof th entire

opulato Cr ree times per

these and ther facilities wi uilding is by

me o link all five

levels of the building, and ensure the secure movement of groups of prison-ers by a limited number of guards.

fig. 41a: final model view from space in north-east corner of site toward chapel 40- 41

Additionally, two banks of elevators located at either end of the central zone of circulation allow for transpor-tati disabl - . . -

r

lt inmates.Be: cells are the

'd ig centers for

one

e offices,ent cells, and pharmaceutical storae

a'd

distribu-tion. There is a secure area consistingof group visitation roois which is

accessed by the visitors from below via a ramp connecting the entry lobby with the two levels of visitation spaces

The easend

e

is level is the- e- hich newly hit up via ally port ed for stay at s in the a ed here d booking, rooms. A storage of pe inmates to the

h9

own is more

of a mezzanine level, occupying only the two eastern bays of the building's northern half. This part houses the

fig. 43a: final model

private facilities for the guards includ-ing changinclud-ing and showerinclud-ing areas, dining and kitchen facilities. This area

tors entered

orthern

ate vistitation,1tat10n

level. The

d level is

reationalor the

five foot tall

interior

b-of

support-u activities. le spaceinery and

degallery

e fee spaces for

and the

py this level. erior space is lobby space, tive spaces er recreationof the

program including the chapel and its support spaces, and the library and its supporting educational facilities begin

fig. 45a: final model

44-

45

to move outside of the main body of the building to occupy the prominent Cambride Street part of the site. They

old back on

h the

strative

building's rt of the site.ally to

he northern suggesting at on et edge isuilt and points where spatial cuts into

xist. Prisoners also begin to

c4

te site in a different way,

rem of the wall while

mo

'O he ert of the

building.

The conclusions of this thesis as

represented in the final

presentation

are reconciliation of ideafwhich wereb dational

ttheproject,

as well as hich arose dur the process ofguh the

jecita.

The

ofth

1, the

d issues related nature of the prison itself seemed to drive the project at various points in time. However, the establishment of the cells as the most

important element of the program coupled with a concern for their spatiality was the point of departure for

onsistent seems crucial the

develop-s the

ot only

cdupled withfe

which

An approach these aspects of e oportunitiespateBibliography

Brenner, Douglas et al. "Jails and Prisons." Architectural Record. March 1983. 171(3). p 81-99.

Borland, John et al. "The Irish in Prison: A Tighter Nick for the 'Micks'?" The British

journal

of Sociology. 1995. 46(3). p 371-394.Camhi, Morrie. The Prison Experience. Charles E. Tuttle: Rutland, 1989.

Cloward, Richard, A. et al. Theoretical Studies in the Social Organization of the Prison. Social Science

Research Council: New York, 1960.

Courtney, Marian. "New Jersey State Prison." Metropolis. Jan-Feb 1992. 11(6). p 21-22,24-26.

Dickens, McConville, and Fairweather. Penal Policy and Prison Architecture. Barry Rose: Great Britain, 1978.

'U-Evans, Robin. The Fabrication of Virtue: English Prison . Cambridge University Press:

trit-Mi .

hrrellh"

nis - of the ---- Pison. Pantheof: Nw.Ln

Hall Douglas, K. et al. In Prison. Henry Holt: New York,

1988.

Howard, Roberta. Designs for Contemporary Correctional Facilities. Capitol: Maryland, 1985.

Hunt, Geoffrey et al. "Changes in Prison Culture: Prison Gangs and the Case of the Pepsi Generation." Social

Problems. August 1993. 40(3). p 398-409.

Ignatieff, Michael. A

just

Measure of Pain: The Penitentiary in the Industrial Revolution 1750-1850. Columbia University: New York, 1980.Jenkins, Joylon. "The Hard Cell." New Statesman & Society. March 19, 1993. 6(244). p 18-20.

Johnston, Norman, et al. Crucible of Good Intentions. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Philadelphia, 1994. Johnston, Nonnan. The Human Cage: A Brief History of Prison Architecture. Walker: Philadelphia, 1994. Koolhaas, Rem and Ma u,~Brucee. :M-EXC Monaei ~

Y rk, 1995.

Lyon Dan

Conversations with the Dead. Holt, Rinehart, and

w YQrk, 1988.

...

m

fig. 51a: final model

mL ...-..

(N

Mote, Gary et al. Design Guide for Secure Adult Correctional Facilities. American Correctional Association: College Park, 1983.

"Nailing the Screws." The Economist. May 16, 1992. 323(7759).

p 79.

Noel, Elizabeth. "The Worst Day of the Year." The Spectator.

1995. 275(8736). p 12.

"Prisons Generating Big Interest in Small Towns." Boston Globe. 13 October 1996. All.

Spens, Iona et al. The Architecture of Incarceration. St. Martin's: New York, 1994.

Toch, Hans. Living in Prison: The Ecolog of Survival. The Free Press: New York, 1977.

Worth, Robert. "A Model Prison." The Atlantic. 1995. 276(5). p 38-44.