Trying to Locate the Real Anne Frank in

Recent Authorized Graphic Novels

Matt Reingold

Abstract

Since its publication in 1947, The Diary of Anne Frank has been adapted into many different media and has been the inspiration for numerous creative and literary adaptations. Two official and authorized graphic novels about Anne Frank have been published alongside the rise in interest in graphic novels. Ernie Colon and Sid Jacobson's graphic novel is a biography of Anne's life and legacy, whereas Ari Folman and David Polonsky's graphic novel is a literary adaptation of Anne’s diary. In this article, I argue that competing organizations and individual interpretations of Anne’s place in history result in divergent interpretations of Anne Frank’s life in two recent Anne Frank-themed graphic novels. Seventy years after Anne’s death, she remains as elusive and complex a figure, just as she was with the publication of the original diary by her father upon its discovery.

Résumé:

Depuis sa publication en 1947, le Journal d’Anne Frank a fait l’objet de nombreuses adaptations en divers médias et il a également servi de base à de nombreuses adaptations créatives et littéraires. C’est ainsi que le succès croissant du roman graphique a donné lieu à la sorite de deux bandes dessinées officiellement soutenues par les ayant-droits. Le travail d’Ernie Colon et Sid Jacobson est une biographie de la vie et de la postérité d’Anne Frank, là où le livre d’Ari Folman et David Polonsky constitue une véritable adaptation littéraire du journal. Dans cet article, je démontre que la compétition entre différentes organisations et différentes interprétations subjectives de la place d’Anne Frank dans l’histoire engendre des lectures également divergentes et que les deux romans graphiques en question portent la trace de ces débats.

Soixante-dix ans après la mort d’Anne, elle demeure un personnage insaisissable, comme elle l’était déjà au moment de la découverte puis de la publication de son journal par son père.

Biographical line

Dr. Matt Reingold teaches at TanenbaumCHAT in Toronto, Canada where he also serves as the co-department head of Jewish History. His scholarly publications can be viewed

at https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=a07ZQ24AAAAJ&hl=en

Keywords: Anne Frank, graphic novels, Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colon, Ari Folman and David Polonsky, The Diary of Anne Frank, Holocaust

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jeffrey Shandler identify Anne Frank as a unique cultural and historical figure. Frank, they argue, is one of “few public figures [who] have inspired connections that are as extensive and as diverse, ranging from veneration to sacrilege… They are often deeply personal at the same time that they validate their subject’s iconic stature” (1). This uniqueness is reflected in the continuously evolving catalogue of texts that feature Frank, including ones that transpose her into alternate settings, time periods and contexts. Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Shandler trace Frank’s popularity and her diary to a confluence of factors including the complex history of the diary’s composition and subsequent publication, the circumstances surrounding Anne’s death and the bildungsroman-esque features of the diary in which the Holocaust serves as a backdrop to her development as an adolescent. Sara R. Horowitz notes that “as a book in which the act of writing figures so centrally and self-consciously, Anne Frank’s widely read diary has, not surprisingly, engendered an especially rich array of literary responses” (215). Yet it is crucial to recognize that none of these creative texts are able to fully capture Anne’s life and the experiences. This is because, as adaptations or biographies, they involve synthesizing, condensing, appropriating narrating and interpreting, processes which involve decisions that shape and mould the way in which Anne is depicted.

Decisions were already being made by editors and translators about how best to introduce Anne Frank to the world, even before her diary was posthumously published, and in a manner beyond the literary adaptations that have emerged over the past 70 years. Decisions made by Anne’s father Otto and Contact Publishing, the diary’s first publisher, in 1947 revolved around whether or not including anecdotes about Anne’s arguments with her mother, Anne experiencing her first menstruation and even her first kiss with a boy, were appropriate for publication and whether it would be preferable to censor them in order to present Anne and her family in a particular way.

While the aforementioned examples of diary entries would eventually find their way into the official published version by later editors of the diary, their exclusion reflects the wider editorial stance taken about Anne’s life in which her creative and academic adaptors wanted readers to come to know Anne in a particular way. Since the diary’s publication, Anne’s story and versions of her diary have been staged, narrated, illustrated, filmed and turned into graphic narratives.

Kees Ribbens has identified over fifteen different comic book and graphic novel depictions of Anne Frank that have been published in countries as varied as Mexico, The Philippines, The United States and Japan. As he notes, the preponderance of texts “functions as a solid impression of Anne Frank’s legacy in the medium of sequential art” (221). The following article explores two recently authorized graphic novels about Anne Frank and consider how each offers a different way of understanding Anne’s life. Both Anne Frank’s Diary:

The Graphic Adaptation which has been adapted by Ari Folman, illustrated by David Polonsky and authorized

by the Anne Frank Foundation in Basel and Anne Frank: The Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic

Biography by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón and authorized by The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam and the

Anne Frank Center USA take up the challenge of telling Anne’s story. By considering the texts together for the first time, what emerges is a recognition that even within the same medium, two very different Annes are depicted and this reifies the reality that no text – no matter how authoritative – can fully capture Anne’s nature, character and experiences. Instead, both present carefully curated depictions of Anne, but an analysis of the ways in which they creatively, aesthetically and historically approach Anne’s life reveal two entirely different Anne Franks. Polonsky and Folman’s text positions her as a rebellious, precocious and complex teenager replete with the maturity and immaturity of a teenager, who is approachable to readers because of her personality and the ways that she responds to challenges and difficulties. Conversely, Jacobson and Colón’s text glosses over many aspects of Anne Frank’s complexity, and presents her as an entirely likeable, simple version of the girl who authored the diary and whose significance is in her message of hope and peace for the future. Additionally, by viewing the two texts together, and alongside the ways that Anne has been intentionally and unintentionally occluded and adapted throughout history, the reader is confronted with the reality that despite the over 70 years since her death, Anne still remains an elusive figure whose authentic self

might never be fully revealed.

Creative Adaptations of The Diary of a Young Girl

Horowitz cites “the context of its composition; the intelligence, sensitivity, and tragic fate of its author; [and] the diary’s subsequent cultural stature” (216) as factors that have led to the growing body of works that depict Anne. These works, Horowitz argues, lead Anne to transcend her own narrative and to become an “imaginary Anne”, one who takes on the identities of the people who rewrite her story. While Horowitz’s academic treatment of the nature of Anne Frank-inspired literature remains neutral in its assessment of these works’ merits, it is important to acknowledge that the concept of Anne Frank adaptations has engendered negative reactions. In a 1997 New Yorker article, Cynthia Ozick remarked how the diary has been “bowdlerized, distorted, transmuted, traduced, reduced; it has been infantilized, Americanized, homogenized, sentimentalized, falsified, kitschified, and, in fact, blatantly and arrogantly denied”. Sparing no one, Ozick castigates dramatists, directors, translators, Otto Frank and even the public for what has been done to Anne Frank’s work and her legacy as expressed in these different texts.

Kirshenblatt-Gimbell and Shandler see the diary as “an open text, not least because … it is an unfinished work, just as her life was cut short by her murder at the age of fifteen” (5). The text is, quite literally, an open text given that it ends when Anne is forcefully removed from the annex, but it is also an open text in how it has been used as a foundation for alternative analyses and a blank canvas for literary treatment. The transformation of Anne Frank the historical author to a literary character, suggests Marouf Arif Hasian, occurred even before the diary was first published. It is well known that Otto Frank had difficulty securing a publisher for his daughter’s diary but once one was found, they prioritized focusing on the “humanist dimensions” (356) of Anne’s life as opposed to the uniquely Jewish ones that led to her death in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Nazi Germany. Dramatists Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett helped popularize this universalist message of the diary with their stage adaptation of the diary that premiered on Broadway in 1955. The depictions of Anne that were offered by the publishers and by Goodrich and Hackett, suggests Alex Sagan, leads one to “sugar-coat and obscure the nature of the genocidal persecutions that led to her death” (103). They also “project[ed] a naïve and somewhat ahistorical picture” (104) of Anne by glossing or smoothing over the harsh critiques and criticisms that she sometimes had of her family members and her circumstances in the annex.

Hasian documents how by the early 1960s, buoyed by the success of the diary and concerns with its universal messages, the diary was reframed by some in the Jewish community as a Jewish text due to a belief that the diary “would contribute to denial, minimization, or depoliticization of the Holocaust” (359). Therefore, with a growing global awareness and willingness to engage with the Holocaust as a traumatic experience, the diary was positioned as a text that was about a Jewish girl who was murdered for being Jewish. The two contrasting readings of Anne – universalistic or particularistic – coupled with the burgeoning catalogue of Anne-texts led to myriad readings and mis-readings of Anne’s story. Hasian notes how “the passage of time did not bring some mystical clarify or univocality of opinion, but rather a blurring of images and arguments” (362). Instead, Kirshenblatt-Gimbett and Shandler suggest that “in none of these paradigms does Anne prove to be a perfect fit” (17)

Despite all of these contrasting interpretations of Anne, Nigel A. Caplan rightly notes how it was actually Anne herself who was the first to curate or present her diary in a particular way. While initially composed as a diary that “functions as a place of refuge, a safe niche in which to construct and explore her various, but carefully hidden selves” (Goertz), Anne began editing and rewriting her own diary following a radio broadcast on March 29, 1944 in which Gerrit Bolkestein, the Dutch Minister for Education, Art and Science, called for individuals to preserve their wartime documents. During this process, she took out specific passages, including ones about her attraction to a female friend from her childhood and her feelings of sexual titillation after seeing

images of female nudes. While eventually restored to the diary, their inclusion results in leading the reader to an appreciation of an Anne who is “more complex, lively, self-reproaching, and biting” (Goertz) than Anne herself envisioned for the text or for how she wanted to be presented to the world. In fact, Anne’s own editing so seamless was that Caplan suggests “that Anne has always tricked readers into believing that it was a precociously talented thirteen-year-old writer, rather than a fifteen-year-old rewriter” (82).

Anne Frank: The Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography

As many readers are likely aware, neither Folman and Polonsky’s graphic adaptation nor Jacobson and Colón’s graphic biography are the first graphic novels to address the Holocaust. Over 40 different graphic novels have been produced about the Holocaust, beginning with Art Spiegelman’s seminal Maus I which was published in 1986. Some, like Maus and Rutu Modan’s The Property have even won major international awards. Stephen Tabachnick has argued that the merit of Holocaust graphic novels is that they provide “a reading and viewing experience together … [O]ne can turn back or forward or linger on a particular panel or page … one can mediate carefully while one is experiencing the work of art, instead of being forced forward every second” (39). The variety of Holocaust graphic novels is exceptionally diverse and reflect a range of subtopics within the field of Holocaust studies. These include memoir, autobiography, fiction and superhero stories and have been published in English, Hebrew, Spanish, German and even Japanese (Weiner and Fallwell).

Henry Gonshak is critical of many of the aforementioned works in his assessment of Holocaust graphic novels, including Will Eisner’s A Life Force and Joe Kubert’s Yossel, for approaching the topic in what he sees as a solely a realistic way by presenting a fairly linear, straight-forward and visually literal narrative. While rich in detail – both textually and visually – the graphic novels do not involve imaginative or creative approaches towards representing or depicting the Holocaust. It is this type of Holocaust graphic novel that most accurately describes Jacobson and Colón’s graphic biography of Anne Frank. Published under the auspices and authorization of the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam and the Anne Frank Center USA, the work is a biography of Anne’s life and not a graphic adaptation of her diary. The contents of the graphic novel reflect the identity of the Anne Frank House as “an independent organization that manages the place where Anne Frank was in hiding during the Second World War, and where she wrote her diary” (“What we do”). While Anne’s diary was written in the secret annex, the Anne Frank House does not own the rights to the diary and it, therefore, follows that the organization’s mandate does not involve positioning the diary at the forefront of its agenda; instead, it makes use of the entirety of the Frank family’s experiences during World War II. Its goals include not only telling Anne’s story, but also “encouraging people to reflect on the dangers of antisemitism, racism, and discrimination, and the importance of freedom, equal rights, and democracy” (“What we do”). Positioning itself as an educational institution, the Anne Frank House develops curricula for schools and curates exhibitions within the residence in which the Franks lived during the Holocaust.

Beginning their text with the marriage of Anne’s parents Otto and Edith, Jacobson and Colón immediately introduce the reader to the Frank family’s experience and, through this, reflect the Anne Frank House’s interest in telling the entirety of her story and emphasizing universal lessons from her experiences. Over the course of the text, Jacobson and Colón document the rise of Nazism and its impact on the family, culminating in the decision to move into the annex in Amsterdam where they would hide for just over two years. Drawing upon archival materials and eyewitness testimonies, Jacobson and Colón’s work includes depictions of Anne’s life in Bergen-Belsen and her death due to typhus. Focusing primarily on Anne’s biography, the work makes minimal use of Anne’s diary as a referenced primary source and instead relies on narrative and invented dialogue to depict Anne’s experiences.

Jacobson and Colón’s biography of Anne does not end with her death in 1944; instead, it concludes with the discovery of the diary and its subsequent publication. Their biography echoes the editorial decisions made

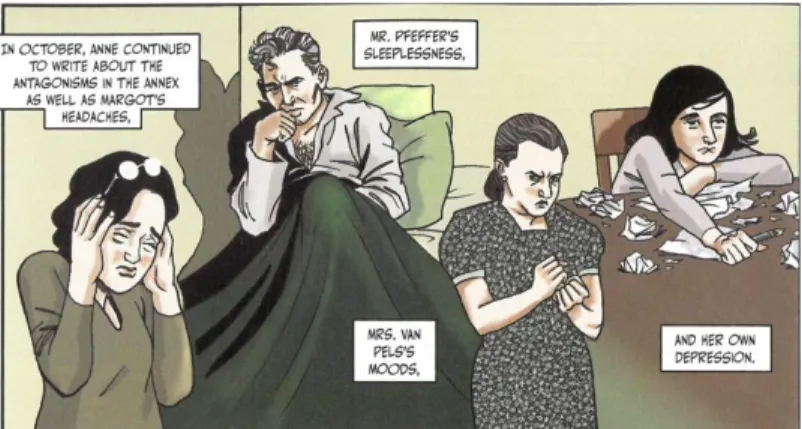

previously by Anne’s father by presenting Anne as a naïve and innocent figure and as one whose life story should project a message of hope, peace and universal humanity. Jacobson and Colón achieve this result by glossing over and omitting many of the more salacious and personal details of Anne’s experiences in the annex. Anne includes dozens of references to conflicts between her and her mother, her feelings of frustration towards other residents in the annex and even her curiosity with male and female genitalia within the diary itself. In Jacobson and Colón’s graphic novel, these details are either not included – like her descriptions of vaginas – or minimized almost to the point of being non-issues. In her diary, Anne reflects on her feelings of isolation while being trapped inside the annex, and of feeling that no one understands her, especially her mother. Jacobson and Colón’s treatment of these texts involves rewriting them as third person descriptions of the experiences and not as the powerful first-person diary entries as they are in Anne’s original diary. In one panel that encapsulates Anne’s many entries, Jacobson and Colón write: “In October, Anne continued to write about the antagonisms in the annex as well as Margot’s (Anne’s sister) headaches. Mr. Pfeffer’s sleeplessness, Mrs. Van Pels’s moods, and her own depression. Anne stated that she didn’t ‘give a dash’ about her mother and Margot… and that there was no one she loved more than her father” (96) (see fig. 1). The sparse description of Anne’s emotional tenor contrasts with her own description of her feelings from November 8, 1943: “I’m currently in the middle of a depression. I couldn’t really tell you what set it off, but I think it stems from my cowardice … This evening… the doorbell rang long and loud. I instantly turned white, my stomach churned, and my heart beat wildly – and all because I was afraid. At night in bed I see myself alone in a dungeon,… I simply can’t imagine the world will ever be normal again for us. I do talk about ‘after the war,’ but it’s as if I were talking about a castle in the air, something that can never come true” (Frank, 144-145)

Fig 1. Third-person description and depiction of Anne’s depression, p. 96. Excerpts from ANNE FRANK: THE ANNE FRANK HOUSE AUTHORIZED GRAPHIC BIOGRAPHY by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón. Copyright © 2010 by Sid Jacobson. Artwork copyright © 2010 by Ernesto Colón. Reprinted by permission of Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

A further way in which Jacobson and Colón’s biography of Anne Frank reflect a particular editorial stance towards positioning Anne in as humane a way as possible is their depiction of Anne’s afterlife. As noted previously, Anne’s death does not end the biography. Instead, the story of how Otto Frank published the diary and its subsequent popularity conclude the work. On the graphic novel’s penultimate page, an enlarged ghostly apparition of Anne hovers over Otto’s head as he ponders how best to preserve her memory. Illustrated almost like a holy religious martyr, Otto is lost in thought about Anne’s memory and her experiences and how they can be preserved so that her death was not without purpose (see fig. 2). Reading the image in this way is affirmed by Jacobson and Colón’s concluding page. There, a multiracial group of young adults is depicted in the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam clustered around artifacts from her time in the annex, with the diary prominently displayed in the middle of the page. Framing the images are two caption boxes which read: “Over the years, millions of visitors from every corner of the globe have come to see the place where Anne Frank wrote her diary … Anne has indeed become a world-famous inspiration to many” (141) (see fig. 3). Ending their biography by visualizing a diverse community of people who have come together to learn and be inspired by Anne’s experiences conveys a particular narratological statement that reflects the education goals of the Anne Frank House; this ending suggests that Anne’s death has not been in vain and that her writings serve a higher moral purpose from which everyone can learn. At the same time, however, by choosing to position Anne as a universal figure, Jacobson and Colón omit many of the salient details that show Anne as a real

person who struggled during the war. Including these details might detract from the narrative that they are trying to present about a girl whose legacy is our shared humanity as people, irrespective of race and religion. For example, in much the same way that Otto Frank did not want these passages included in the published diary for fear of how people would react to Anne, including scenes that show Anne being disrespectful to her mother might prevent a reader from being able to learn lessons about global peace, given that Anne herself seems unable to be kind to family members who are protecting her from the Nazis.

Pramod Nayar argues that the medium of graphic novels provides a unique forum for the expression of biography. He writes: “rather than a straight, linear narrative that requires elaborations and footnotes … the graphic medium allows us to see, in one sweeping iconostatic gaze (history) … It also allows the representation of historical impact in direct visual terms in the form of spatialized arrangements of characters in panels. Multiple temporalities as portrayed in the folding of the documentary into the aesthetic facilitate our understanding” (167).

Fig 2 and 3. Establishing the Anne Frank House museum where all people can learn from her experiences, p. 140-141. Excerpts from ANNE FRANK: THE ANNE FRANK HOUSE AUTHORIZED GRAPHIC BIOGRAPHY by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón. Copyright © 2010 by Sid Jacobson. Artwork copyright © 2010 by Ernesto Colón. Reprinted by permission of Hill and

Wang, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

While Tabachnick’s observation that the graphic novel provides the reader with “a fuller understanding of Anne’s life” (55) because their source material extends beyond her diary is well taken, the potential offered by the genre to weave together a narrative of Anne’s experiences and story across space and time and to use imagery itself as a conduit for meaning-making is virtually non-existent in Jacobson and Colon’s biography of Anne Frank. Their biography emphasizes text over image, wherein the text often describes what is being depicted in the image and rarely do they complement each other by presenting the narrative in different, yet compatible, ways. Visually, the text relies on literal illustrations of the characters atop blank backgrounds.

Tabachnick has praised the artistic style for its “realistic visual rendering of [Anne’s] appearance and those of her companions and of their condition” (40), the absence of backgrounds and the context they can provide reinforces how non-interpretive and non-imaginative the illustrations are. Similar to how their narrative treatment of Anne downplays her complexity, sophistication and maturity in favor of a universal narrative, the images likewise retain a superficial quality that diminishes Anne’s story and denies it the uniqueness that it deserves. While likely designed to be as non-confrontational or non-offensive to readers, what remains is a text that is equally devoid of aesthetic, artistic, or analytic risks. In this way, Jacobson and Colón’s Holocaust graphic novel reflects Gonshak’s criticism about many Holocaust graphic novels that I mentioned previously and they present an Anne who reflects the universal message that the Anne Frank House wants to present to the world. This Anne can be located in the diary, but by omitting the less salient details which might disappoint or shock readers, Jacobson and Colón create an Anne who is not reflective of the entirety of the diary. Even though making meaning of a historical figure’s life is one of the biographer’s tasks since the biographer must make “order, continuity, coherence, and closure” (Benton, 5), in Jacobson and Colón’s treatment of Anne’s narrative I identify echoes of the critique levied by James Scorer of their early work Che: A Graphic

Biography. He sees a text that is more explanatory than analytical in their graphic biography of Che Guevara;

more targeted at beginners than for people already familiar with the text. What results in the case of Che, he argues, is a text that is “didactic [in] nature” and which involves “the anachronistic persistence of the mythic past … Far from animating Latin America, the work thus runs the risk of turning it into an unchangeable object” (142). In the case of Anne Frank, Jacobson and Colón strip Anne’s life of the complexity and nuance that is so present in her diary while repositioning Anne’s traumatic experiences as part of a story of hope even as their own narrative voices are virtually non-existent throughout the text; this is achieved by condensing Anne’s family history, her life, and her posthumous literary afterlife into under 140 pages. What emerges most clearly, however, is a story of hope with no context or details – objective or subjective – to support this conclusion. The sparsity and superficiality of details to support a reading of Anne as a beacon of hope is not clearly presented and the text almost seems to rely on the reader’s own pre-knowledge of the veneration of Anne in order to justify their representation of her story.

Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation

Unlike Jacobson and Colón’s biography of Anne Frank which is typical of the majority of Holocaust graphic novels in its presentation of the Holocaust, Folman and Polonsky’s adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary reflects the alternative way of Holocaust representation as identified by Gonshak. When considering Art Spiegelman’s

Maus, Gonshak writes: “Maus honors the cartoon genre while simultaneously transcending it… a good

Holocaust graphic novel must take aesthetic risks, as well as try to fully exploit the potential for the genre” (77). A work of this nature is polarizing; it provokes responses and emotional reactions; it leads to agreement and disagreement; perhaps most importantly, it offers a narrative voice that guides the reader through the text by challenging the reader to consider the Holocaust anew. Where the two recent authorized graphic novels about Anne Frank differ most is with how Folman and Polonsky’s work is far more imaginative, creative, riskier and nuanced, as a result of the potential to polarize the readership.

Folman and Polonsky’s graphic adaptation of the diary is an authorization by the Anne Frank Foundation. The Foundation is the international organization that holds the copyright to the diary and to later writings by Otto Frank and authorizes adaptations and translations of the text. Founded by Otto Frank following the discovery of the diary, the Foundation is “committed to strengthening human rights, in particular child and women’s rights, and promoting a more just society” (“Tasks”) by publicizing and making the diary available in many languages and formats.

At the end of the graphic novel, Folman describes the process that he and Polonsky underwent when trying to adapt Anne’s diary into a graphic novel. Beyond the ideological risks involved with turning what he calls an

“iconic text” into a graphic novel, “illustrating the entire text in a graphic rendition would require the better part of a decade and would likely be 3,500 pages long” (148). Therefore, Folman and Polonsky endeavoured to “retain only a portion of Anne’s original diary while still being faithful to the entire work” (148). The decision to select some texts over others and to blend multiple texts into single images reflects an understanding that some texts would be prioritized over others, even as they included full and lengthy passages. The act of choosing texts involves an editorial process in which Folman and Polonsky decided who their Anne would be. Through their selection of entries, like the later editors of the diary who sought to restore Anne’s complexity, Folman and Polonsky depict a teenager who openly grappled with her circumstances and who struggled significantly under Nazi rule. Their Anne is one who fights with her family frequently and does not always see the positives in life. It is crucial to recognize that even though they depict an Anne who is complex and developed, by selecting some texts over others and by providing artistic interpretations of her words, Folman and Polonsky have made editorial decisions that reflect their understanding of Anne, and not necessarily Anne herself. As a result of these editorial choices, it becomes evident that, like Jacobson and Colón, Folman and Polonsky have undergone a process of depicting a specific Anne Frank and even though one of the texts is a biography and one an adaptation, both are commentaries on Anne that position her in a particular way. Identifying this distinction facilitates opportunities to consider the myriad ways artists and scholars have understood Anne’s life and experiences, but it also leads to recognizing the impossibility of an objectively true accounting of her story.

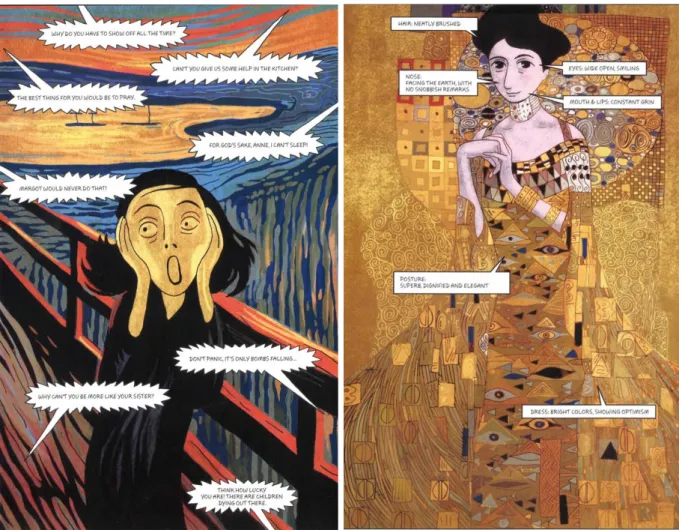

One of the ways in which Folman and Polonsky introduce their interpretation of Anne’s diary is by using illustrations to depict their understanding of Anne’s emotional state. Across a two-page spread, Anne’s face is transposed over the body of the central character in Edward Munch’s painting “The Scream” and Margot’s face is transposed over Adele Bloch-Bauer in Gustav Klimt’s “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I” (see figs. 4 and 5). Accompanying the images are criticisms of Anne and compliments to Margot. Throughout her diary, Anne is very cognizant of her own deteriorating emotional state and is self-aware of her own declining mental health. She references feeling depressed and lost. These feelings are a result of a confluence of factors that include the extended period spent in the annex and her feelings of frustration over the way the other residents treat her. The paintings serve as metonyms that reflect how Polonsky understands Anne’s increasing descent into depression, as reflected by Munch’s painting, and how it is exacerbated by her perception – even if this perception does not reflect reality - that Margot is able to remain inured to what is happening within the annex in the same way that Bloch-Bauer appears to be passive in her portrait.

Fig. 4 and 5. Anne depicted in ‘The Scream’ and Margot depicted in ‘Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer’, p. 54-55. Text, by Ari Folman, copyright © 2018 by Ari Folman; and Illustrations, by David Polonsky, copyright © 2017 by David Polonsky; from ANNE FRANK'S DIARY: THE GRAPHIC ADAPTATION by Anne Frank. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint

of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Considered in this way, while it is abundantly clear from her diary entries that Anne audibly rages against the people who live with her in the Annex, like the figure in Munch’s painting, her assumption that Margot is unaffected by the external stimuli of anti-Semitism and war is, as Folman and Polonsky suggest, probably incorrect. The apparent absence of emotion that is present on Bloch-Bauer’s face is a carefully constructed façade that is designed to present her that way. By appropriating Bloch-Bauer’s likeness, Folman and Polonsky suggest that understanding Margot’s silences are more complex than the singular way in which Anne understands and describes them.

Throughout their graphic novel, Folman and Polonsky include no fewer than eight images of Anne falling, sinking or drowning (see fig. 6).1 These images are significant within the graphic novel because Anne never mentions any of these happening in her fantasies or fears in the diary itself. Instead, they serve as visual metaphors that reflect the ways that Folman and Polonsky understand Anne’s narrative. They are the most consistent narratological device that is included in the work, and they frame the diary as not a text of hope, but one of both complexity and tragedy in which the titular figure, despite some moments of levity and joy, is weighed down by the world around her. Folman and Polonsky’s visualization of Anne’s depression, as

1 I would like to thank the anonymous reviewer who noted that Folman and Polonsky’s graphic adaptation of Anne Frank is not

their only work that prominently features imagery of drowning and sinking, and that it is a reoccurring motif in their work together. In their earlier autobiographical film and graphic novel Waltz with Bashir, the titular character Ari is also shown submerged under water, sometimes fighting against the tide and struggling to keep himself afloat and at other times giving in to the pull of the water and being carried along with the tide.

something that pulls at her sharply, contrasts with the aforementioned third-person, one-line description provided by Jacobson and Colón that Anne was depressed while living in the annex. The inclusion of visual commentary of Anne’s depression, as opposed to a perfunctory mention of a topic that shapes the way that Anne sees and interacts with the world is reflective of the contrasting editorial agendas of each of the texts. Whereas Jacobson and Colón’s text is objectively descriptive of what Anne experienced in her lifetime, beyond presenting the diary, Folman and Polonsky’s text is also subjectively descriptive of how they interpret Anne’s experiences in the annex.

Problematizing Literary Responses to the Holocaust

Unlike Jacobson and Colón’s biography of Anne Frank, in which a happy ending and a positive posthumous evaluation of Anne’s significance redeems and reframes her traumatic experiences, there is no such closure to be found in Folman and Polonsky’s adaptation of the diary.

Fig. 6. Example of Anne sinking, p. 47. Text, by Ari Folman, copyright © 2018 by Ari Folman; and Illustrations, by David Polonsky, copyright © 2017 by David Polonsky; from ANNE FRANK'S DIARY: THE GRAPHIC ADAPTATION by Anne

Frank. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

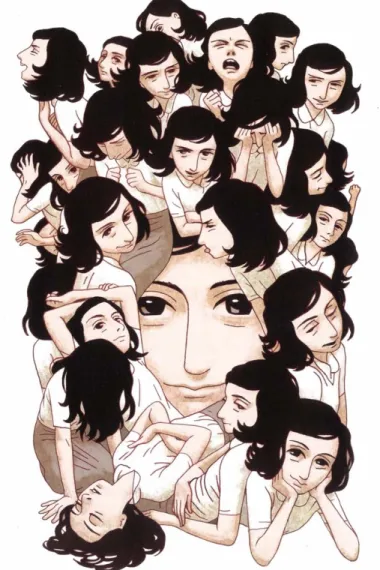

Instead, the final page of the work is a montage of over 20 illustrations of Anne showing facial expressions that range from happiness to sadness and anger to placidity (see fig. 7). This image leaves the reader with a greater awareness of the complexity of Anne’s life and the diverse feelings and emotions that she experienced while living in the annex and how they reflect the wide range of feelings that are present in everyone. This image ultimately comes to symbolize a rejection of the type of simplistic Holocaust narratives that gloss over complex narratives and feelings like the ones that Gonshak has identified as being present in many Holocaust graphic novels when he notes how many of the Holocaust graphic novels rely on “stock assumptions” and turn the Holocaust “into an easily dismissible cliché” (76). It also reflects an interpretation of Anne Frank as a universalizable character for entirely different reasons than the one offered by Jacobson and Colón. Instead of focusing solely on the universalizable message of hope, Folman and Polonsky introduce the reader to a wider range of Anne’s feelings, and through their juxtaposition of diary entries, they consider how this range is part of the richness, complexity, and difficulty of fully appreciating her story. Folman and Polonsky suggest that while no one will be able to relate to all of her experiences or feelings, because of the range of emotions that emerge from their close reading of the diary, everyone will be able to connect on a deep and personal level with some of her experiences; it is this aspect of Anne’s experiences that is universalizable.

illustrators can use creative tools to convey the narrative in non-superficial ways, there exists a further concern about Holocaust representation that is raised by Sophia Marshman. She writes: “in the process of ‘remembering’ the Holocaust, our desire to hide from its ultimate horror is reflected in the preference of many for representational forms which make it somehow bearable. But we are not simply looking for a bearable Holocaust; we may also be looking for a ‘safe’ glimpse of horror” (9).

Fig. 7. Illustration of Anne’s emotional range, p. 145. Text, by Ari Folman, copyright © 2018 by Ari Folman; and Illustrations, by David Polonsky, copyright © 2017 by David Polonsky; from ANNE FRANK'S DIARY: THE GRAPHIC ADAPTATION by Anne Frank. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin

Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Marshman worries that Holocaust representations, by virtue of a desire for them to be palatable, not only obfuscates the real horrors of it, but might lead to misunderstandings and inaccuracies in how its stories are told. Marshman’s concerns are not trivial; the popularity of works like William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice and John Boyne’s The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, irrespective of their artistic merit, present a Holocaust narrative that reframes what is primarily a Jewish experience as one in which non-Jewish adults and children are equally victims of the Nazi machination.

In light of Marshman’s considerations, the detailed prose offered by Jacobson and Colón is rich in detail and accurately relays what happened to Anne and her family. Their graphic novel effectively conveys to the reader the traumas that the Franks experienced and the ways that the Holocaust impacted upon their lives. Furthermore, despite glossing over Anne’s feelings, they do depict images of suffering and pain, including showing an emaciated and flea-bitten Anne at the end of her life (see fig. 8).

Fig 8. Anne in Auschwitz, p. 124. Excerpts from ANNE FRANK: THE ANNE FRANK HOUSE AUTHORIZED GRAPHIC BIOGRAPHY by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón. Copyright © 2010 by Sid Jacobson. Artwork copyright © 2010 by Ernesto

Colón. Reprinted by permission of Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

At first glance, the use of Anne’s diary itself as the text of their graphic novel would suggest that Folman and Polonsky’s diary should also be considered a text that is reflective of a broader and authentic Holocaust experience. Making use of the diary in such extensive fashion not only ensures that it is abundantly clear that it is Anne Frank’s diary which is the subject of the work, but it also restores Anne’s voice to her own narrative. Yet Folman and Polonsky’s own recognition, which they have abridged and synthesized in order to produce a graphic novel, involves editorial decisions that are not reflective of the ones that Anne herself made when she began editing her own diary in 1944. The omission of entries and the conjoining of entries reflects concerns that have been made by historians (Clark). By moving away from the original text and transforming it into a graphic novel, historians suggest that the text loses its inherent value and becomes something else entirely. J. Spencer Clark’s response is that any history textbook also bastardizes the original source material, and graphic novels should therefore not be singled out as an exception. He writes: “graphic novels offer an interpretation for readers to engage as they make sense of historical agents’ actions, and the reasons that sparked those actions, by utilizing traditional historical sources in unique narrative forms” (68).

Adopting the position there is inherent tension in trying to turn the entirety of Anne Frank’s diary into a graphic novel and that it is important to produce a work that retains historical accuracy, one of the ways that Folman and Polonsky have attempted to resolve this conflict is by way of imagery. Beyond the printed text included from Anne’s diary, their graphic novel also makes use of images that also depict Anne’s diary entries. Polonsky’s images visualize the feelings that Anne describes in her text; they even replace the printed text itself in some instances. Their work is, therefore, a multilayered adaptation of the diary in which the printed text is only one component of their presentation of the diary. Both image and word are conjoined texts through which the reader is able to gain a more complete understanding of Anne’s original text, but only when read together.

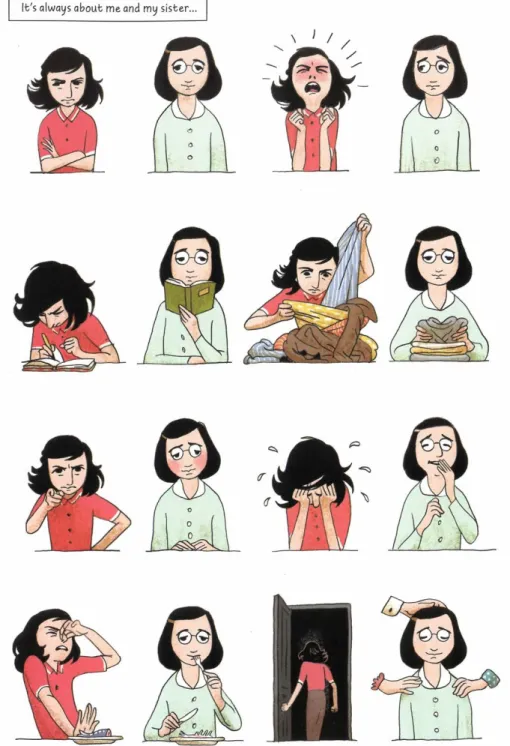

One example of an instance in which Polonsky uses images to preserve the content of the diary without including any of Anne’s written words is found early in the graphic novel. A constant source of frustration for Anne is her perception that her family loves Margot more than her because Margot is a perfect child. Using only the textual prompt “It’s always about me and my sister…” (28), Polonsky illustrates eight different examples from the diary of specific things that Anne believes that Margot does better than her. Illustrated as juxtaposed images, Anne is shown to be temperamental to Margot’s docile, messy to Margot’s neat, picky to Margot’s amenable and, ultimately, rejected to Margot’s accepted (see fig. 9). Stylistically, Polonsky includes all eight pairings within one panel. While the eight different events occurred at different moments in time in the annex, and in turn in the diary, by containing them within one panel, which indicates a singular unit of time, Polonsky fuses them together to reflect Anne’s increasingly heightened feelings of frustration at the comparisons between herself and her sister, while preserving the historical integrity of Anne’s words.

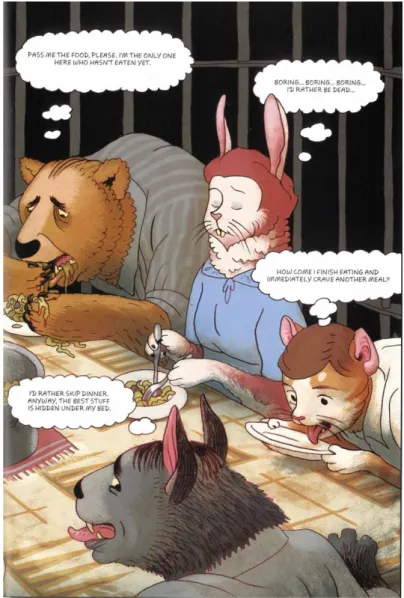

recognize that the selection of which texts to include is not the only way that Folman and Polonsky synthesize their own understanding of Anne Frank with the diary. Polonsky’s images and page layouts are equally important devices in discerning the ways that they understand Anne and how they convey this understanding to the reader. Their text is what all good adaptations are: “a derivation that is not derivative – a work that is second without being secondary. It is its own palimpsestic thing” (Hutcheon and O’Flynn, 9). In a fairly lengthy diary entry on August 9, 1943, Anne describes a typical meal and the ways that each of the inhabitants behave at dinner. In her description of her sister Margot, Anne writes that she eats like a bird. Channeling Art Spiegelman’s usage of animals as metaphoric substitutes for different groups of people, here, Polonsky uses Anne’s singular reference to an animal as a springboard for illustrating every resident of the annex as a different animal based on her descriptions of their behaviours and personalities (see fig. 10).

Fig. 9. Juxtaposition of Anne and Margot’s behaviour, p. 28. Text, by Ari Folman, copyright © 2018 by Ari Folman; and Illustrations, by David Polonsky, copyright © 2017 by David Polonsky; from ANNE FRANK'S DIARY: THE GRAPHIC ADAPTATION by Anne Frank. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a

Her father, the paradigm for modesty, is a slender stork and the gluttonous Pfeffer is a ravenous wolf who consumes great quantities of food. Anthropomorphizing the residents of the annex as animals can be understood in a number of ways. It might be an artistic attempt to create visual parallels between individuals and members of the animal kingdom. It might also be an attempt to reject Nazi racial doctrine, which postulates that Jews are all bestial with only base impulses. It could also be an attempt to appropriate that Nazi contention and by illustrating Jews as animals, take ownership of the types of animals that people are. The reading I prefer, however, is one that is critical of Anne because all of the animals, even the domesticated and docile ones, are illustrated in some type of negative way, by being either too self-indulgent or too dismissive of the other residents. Perhaps, by adopting the Nazi stance that Jews are animalistic, but by reading these traits into Anne’s words, Folman and Polonsky are critical of the ways that Anne herself disparages and insults the people around her by generalizing their behaviours and stereotyping their personalities. Folman and Polonsky are not likening Anne’s criticisms of her fellow residents to the behaviours and attitudes of Nazis, but through the use of animal imagery, they highlight how childish and juvenile Anne can sometimes be for stereotyping, generalizing or demeaning the people around her in cruel ways that are similar to those of the Nazis.

A further way that historical authenticity is maintained despite the need to adapt the text is through the use of the previously mentioned visual metaphor of descent and drowning. Considered additionally as a visualized foreshadowing of what will happen to Anne once she stops writing and is taken first to Auschwitz and later to Bergen-Belsen, Folman and Polonsky weave this privileged information that readers of the diary know that Anne herself does not. Additionally, making use of dramatic irony in this way further preserves the text’s historical context as it ensures that despite some of Anne’s hopeful statements, the images reify the fact that her life is ultimately cut short. Reading the images of descent in this way recognizes that

their adaptation is a synthesis of preserving the historical record of the diary, remaining attuned to Anne’s ultimate death and integrating their own understanding of Anne as expressed through the diary.

Fig. 10. Residents of the annex depicted as animals, p. 75. Text, by Ari Folman, copyright © 2018 by Ari Folman; and Illustrations, by David Polonsky, copyright © 2017 by David Polonsky; from ANNE FRANK'S DIARY: THE GRAPHIC ADAPTATION by Anne Frank. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a

division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Like Gonshak’s conclusion following his comparison between Maus and other Holocaust graphic novels, the demerits of Jacobson and Colón’s biography of Anne Frank serve to highlight and even accentuate the strengths of Folman and Polonsky’s adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary. Horowitz writes how Anne has been used as “authorial role model, as publishing brand, as imagined companion or lover, as literary icon to be reckoned with… They prompt questions about our relationship with the past and about assumptions and desires readers bring to the act of reading” in her literary afterlives (216). What Folman and Polonsky’s text accomplishes – and this is heightened when considered in light of Jacobson and Colón’s text – is to require the reader to consider Anne anew, not just as a messenger of hope. The creative and complex interplay between text and image moves closer to restoring the diary to its rightful owner – Anne – but with an added layer of insight into how the Holocaust affected her in ways that are not always clear to Anne herself. The juxtaposition of authentic text with the sub-textual tacit acknowledgment of what befalls her provides the reader with an opportunity to engage with the text on its own terms and to consider it in provocative ways that challenge our understanding of Anne’s own mental health and her relationships with her family, leading ultimately to a richer and more meaningful engagement with the Holocaust.

What both texts demonstrate, especially when considered together and in light of their status as ‘authoritative’, is the challenge that contemporary readers face when trying to come closer towards understanding Anne. Beyond the fact that each text has limitations that range from the omission of significant portions of the diary

to the ways that Anne’s feelings and experiences are minimized, the texts present entirely different understandings and interpretations of who Anne was and what her legacy should be. This difference reflects the nature of the work of the adaptors and biographers as they try to make meaning of Anne’s life by evaluating and weighing the significance of diary entries, artefacts and the historical context and legacy of the Holocaust. It also reflects the nature of working with a figure who has already been depicted in dozens of earlier creative works and whose legacy is far reaching and transcends international borders, faiths, cultures and communities. Anne is a global figure whose legacy, message and identity are – irrespective of organizational approval – subject to interpretation, and Jacobson and Colón and Folman and Polonsky’s contributions to the expanding catalogue serve to introduce new ways of interpreting her story and serve to remind the reader how far we have left to go before we fully come to know Anne in her totality.

Works Cited

Benton, Michael. “The Aesthetics of Biography – And What It Teachers.” The Journal of Aesthetic

Education, 49, 1, 2015, 1-19.

Boyne, John. The Boy in the Striped Pajamas. Oxford, David Fickling Books, 2006.

Caplan, Nigel A. “Revisiting the Diary: Rereading Anne Frank’s Rewriting.” The Lion and the Unicorn, 28, 1, 2004, 77-95.

Clark, J. Spencer. “Teaching Historical Agency: Explicitly Connecting Past and Present with Graphic Novels.” Social Studies Research and Practice, 9, 3, 2014, 66-80.

Dean, John. “Adapting History and Literature into Movies.” American Studies Journal, 53, 2009. Eisner, Will. A Life Force. Norton, 2006.

Folman, Ari, and David Polonsky. Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation. New York, Pantheon Books, 2018.

Folman, Ari and David Polonsky. Waltz with Bashir: A Lebanon War Story. New York, Metropolitan Books, 2009.

Frank, Anne. The Diary of a Young Girl: The Definitive Edition, edited by Otto H. Frank and Mirjam Pressler, translated by Susan Massotty, New York, Anchor Books, 1996.

Goertz, Karein K. “Writing from the Secret Annex: The Case of Anne Frank.” Michigan Quarterly Review, 39, 3, 2000.

Gonshak, Henry. “Beyond Maus: Other Holocaust Graphic Novels.” Shofar, 28, 1, 2009, 55-79. Goodrich, Frances, and Albert Hackett. The Diary of Anne Frank. Random House, 1956.

Hasian, Marouf Arif. “Anne Frank, Bergen-Belsen, and the Polysemic Nature of Holocaust Memories.”

Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 4, 3, 2001, 349-374.

Horowitz, Sara R. “Literary Afterlives of Anne Frank.” Anne Frank Unbound, edited by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jeffrey Shandler, Indiana University Press, 2012, pp. 215-253. Hutcheon, Linda, and Siobhan O’Flynn. A Theory of Adaptation. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2013.

Jacobson, Sid, and Ernie Colón. Anne Frank: The Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography. New York, Hill and Wang, 2010.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara, and Jeffrey Shandler. “Introduction: Anne Frank, the Phenomenon.” Anne

Frank Unbound, edited by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Jeffrey Shandler, Indiana University

Press, 2012, pp. 1-22.

Kubert, Joe. Yossel April 19, 1943. New York, iBooks, 2003.

Marshman, Sophia. “From the Margins to the Mainstream?: Representations of the Holocaust in Popular Culture.” eSharp, 6, 1, 2005.

Modan, Rutu. The Property. Drawn and Quarterly, 2013.

Nayar, Pramrod K. “Radical Graphics: Martin Luther King, Jr., B.R. Ambedkar, and Comics Auto/Biography.” Biography, 39, 2, 2016, 147-171.

Ozick, Cynthia. "A Critic at Large: Who Owns Anne Frank?" New Yorker, 6 Oct. 1997.

Ribbens, Kees. “War Comics Beyond the Battlefield: Anne Frank’s Transnational Representations in Sequential Art.” Comics Worlds and the World of Comics: Towards Scholarship on a Global Scale, edited by Jaqueline Berndt, Kyoto, International Manga Research Center, Kyoto Seika University, 2010, 217-231.

Sagan, Alex. “An Optimistic Icon: Anne Frank’s Canonization in Postwar Culture.” German Politics &

Society, 13, 3 (36), 1995, 95-107.

Scorer, James. “Man, Myth and Sacrifice: Graphic Biographies of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara.” Journal of

Graphic Novels and Comics, 1, 2, 2010, 137-150.

Spiegelman, Art. The Complete Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. New York, Pantheon, 1996. Styron, William. Sophie’s Choice. Random House, 1979.

Tabachnick, Stephen E. The Quest for Jewish Belief and Identity in the Graphic Novel. Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 2014.

“Tasks.” Anne Frank Fund. https://www.annefrank.ch/de/fonds/aufgaben.

Weiner, Robert G., and Lynne Fallwell. “Sequential Art Narrative and the Holocaust.” The Routledge

History of the Holocaust, edited by Jonathan Friedman, Routledge, 2010.

“What we do.” Anne Frank House. https://www.annefrank.org/en/about-us/what-we-do/.

Dr. Matt Reingold