Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

L j 15

Dewey

oi-

I3

'-1^Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

COPING

WITH

CHILE'S

EXTERNAL

VULNERABILITY:

A

FINANCIAL

PROBLEM

Ricardo

J.

Caballero

WORKING

PAPER

01-23

REVISED,

January 2002

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Diive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper

can be downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science Research Network

Paper

Collection

at

http://papers.ssrn.

c

\(y

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

COPING

WITH

CHILE'S

EXTERNAL

VULNERABILITY:

A

FINANCIAL

PROBLEM

Ricardo

J.Caballero

WORKING

PAPER

01-23

REVISED,

January 2002

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research

Network

Paper

Collection

at

http://papers.ssrn.

conn/abstract=274083

'.GHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OFTECHMOLOGY

H'AR

7

2002

Coping

with

Chile's

External

Vulnerability:

A

Financial

Problem

01/11/2002

Ricardo

J.

Caballero'

Abstract

With

traditionaldomestic imbalances long

under

control, theChilean business

cycle isdriven

by

external shocks.Most

importantly,Chile

'sexternal vulnerability isprimarily

a

financial

problem.

A

decline in theChilean

terms-of-trade,for

example,

isassociated

toa

decline in realGDP

thatismany

timeslarger

than

one

would

predict

in thepresence of

perfect financial markets.

The

financialnature

of

this excess-sensitivityhas two

centraldimensions:

a sharp

contraction in Chile'saccess

tointernationalfinancial

markets

when

itneeds

it themost;

and

an

inefficientreallocationof

thisscarce access

across domestic

borrowers

during

external crises. In thispaper

I

characterize thisfinancial

mechanism

and

argue

that Chile'saggregate

volatilitycan

be reduced

significantlyby

fostering

theprivate

sector'sdevelopment of

financialinstruments

thatare contingent

on

Chile

'smain

external shocks.

As

a

first step, theCentral

Bank

or

IFIscould

issuea

benchmark

instrument

contingent

on

theseshocks. I alsoadvocate

a

countercyclicalmonetary

policy

but

mainly for

incentive—

that is,as

a

substitutefor

taxeson

capital inflowsand

equivalent

measures

—

rather than for

ex-postliquiditypurposes.

'

MIT

and

NBER.

e-mail: caball(a)mit.edu; http://web.mit.edu/caball/www.

Prepared

for theBanco

Centralde

Chile. Iam

very grateful VittorioCorbo, Esteban

Jadresic,and

Norman

Loayza

fortheircomments;

toAdam

Ashcraft,Marco

Morales

and

especiallyClaudio

Raddatz

for excellent research assistance;

and

toHerman

Bennett for his effort collectingmuch

of

theI.

Introduction

and Overview

With

traditionaldomestic imbalances longunder

control,the Chilean business cycle isdrivenby

extemal shocks.

Most

importantly, Chile'sextemal

vulnerabilityisprimarilya financialproblem.A

decline intheChilean

terms-of-trade, forexample,

is associatedtoa declinein realGDP

thatis

many

times larger thanone

would

predict in the presenceof

perfect financial markets.The

financial nature

of

this excess-sensitivity hastwo

central dimensions: a sharp contraction inChile's access to international financial

markets

when

itneeds

it the most;and an

inefficientreallocation

of

this scarce access acrossborrowers

duringextemal

crises. Iargue

that Chile'saggregatevolatility

can

be

reduced

significantlyby

fosteringthe private sector'sdevelopment of

financial instruments that are contingent

on

themain

extemal

shocks

facedby

Chile.As

a first step,the CentralBank

orIFIscouldissueabenchmark

instrument contingenton

these shocks.Ialsoadvocate acountercyclical

monetary

pohcy

(alsocontingenton

theseshocks)butmainly

forincentive

—

that is, as a substitute fortaxeson

capital inflowsand

equivalent—

ratherthan forex-post hquidity purposes.

The

essenceof

themechanism

through

which

extemal shocks

affect theChilean

economy

can

be

characterized as follows: First,there is adeteriorationof

terms-of-tradethat raises theneed

for

extemal

resources ifthe realeconomy

istocontinue unaffected,butthistriggers exactlytheopposite reaction fi^om international financiers,

who

puU back

capital inflows. Occasionally, thelatteroccurs directly as part

of

"contagion" effects.Second,

once extemal

financialmarkets

faUto

accommodate

theneeds

of domestic

fiimisand

households, these agents turn todomestic

financial maricets,

and

tocommercial banks

inparticular. Again, this increase indemand

is notmatched by

an

increase in supply asbanks

—

particularly resident foreign institutions-

tightendomestic

credit, opting instead to increase their net foreign asset positions. Third, there is significant "flight-to-quaUt}^' within the domestic financial system,which

reinforces theabove

effects as large firms find it

more

attractive to seek financing indomestic

markets, incircumstances that the displaced small

and

medium

size firms cannot access intemationalfinancial

markets

atany

price.The

costsof

thismechanism

are high.Widespread

financial constraints are binding during thecrisis,

when

major

forced adjustments are needed.The

sharp decline indomestic

asset prices,and

corresponding rise in expected returns, is drivenby

theextreme

scarcity in financialresources

and

theirhigh

opportunitycost.Even

thepraisedrise inFDI

thatoccurred duringthemost

recentcrisisisasymptom

of

thesefiresales.The

fact thatthisinvestment takes theform

of

control-purchases rather than portfoUo or credit flows

simply

reflectssome

of

the underlyingproblems

that Limit Chile's integration to intemational financial markets:weak

corporategovernance and

other "transparency" standards. Finally, the costsdo

notend

with

the crisis, as financially distressedfirms are iUequipped

tomount

aspeedy

recovery.The

latteroftencomes

not only withthe costs

of

aslow

recoveryinemployment

and

activity,butalsowith aslowdown

in the process

of

creative destmctionand

productivity growth. In the U.S., the lattermay

account

forabout

30%

of

the costsof

an average

recession (see Caballeroand

Hammour,

the presence

of

a largenumber

of

financially distressed small firms,when

severe enough,reduces rather than

enhances

the effectivenessof

monetary

policy in facihtating the recovery(seebelow).

The

distnbutional impactof

thistypeof

crisis is significant as well.On

one

end, large firms aredirectlyaffected

by

external shocks butcan

substitutemost

of

theirfinancialneeds

domestically.They

are affected primarilyby

demand

factors.On

the other, smalland

medium

sized firms (henceforth,PYMES)

arecrowded

outand

are severely constrainedon

the financialside.They

arethe residual claimants

of

thefinancial crunch.-Thisdiagnosis points inthe direction

of

a stmctural solutionbased

on

two

buildingblocks.The

first

one

deals withthe institutionsrequiredtofosterChile's integration to international financialmarkets

and

thedevelopment

of domestic

financialmarkets.Chileismaking

significantprogressalongthis

margin

throughitscapitalmarkets

reform

program.The

second

one,necessaryduringthe unavoidable

slow

natureof

theabove

process, is to designan

appropriate internationalliquidity

management

strategy.The

lattermust

be

understood in terms broader than just themanagement

of

intemational reservesby

the central bank,and

include thedevelopment

of

financial instrumentsthatfacilitatethe delegationof

thistask tothe privatesector.I focus

on

the latter typeof

solutions in this paper.^ Iview

thepohcy

problem

asone

of

remedying

a chronic private sector underinsurance with respect to external crises.' Afteroutlining the

main

sourcesof such

problem

and

the corresponding solutions, I focuson two

of

them.

The

firstone

seeks todevelop

akey

missing market. Ipropose

the creationof

abenchmark

"bond"

that ismade

contingenton

themain

externalshocks

facedby

Chile. Thisinstalment should facilitate the private sector's pricing

and

creationof

similarand

derivativecontingentfinancial instruments.

Inthe

second

one,Idiscussoptimalmonetary

poUcy

and

intemational reservemanagement

fi-oman

insuranceperspective.Provided

thattheCentralBank

of

Chile hasachieved

ahighdegreeof

inflation-target credibility,the optimal responseto

an

externalshock

iswith

amoderate

injectionof

reservesand an

expansionarymonetary

pohcy.The

latter,however,

isunlikely tohave

alargereal impact

and

indeed willimply

a sharp short-Uvedexchange

rate depreciation.The main

benefit

of

suchpohcy

is in the incentives it provides. Itsmain

problem

is that it istime-inconsistent.

Section II describes the essence

of

theextemal

shocksand

the financialmechanism

atwork.

2

See Caballero (1999,2001) fora discussion ofthestructural reformsaimed atimprovingintegration and

thedevelopment offinancial markets.

More

importantly, Chileis inthe process ofenactinga majorcapitalmarketsreform.

Section

in

follows with a discussionof

theimpact of

thismechanism on

the real sideof

theeconomy

and

the differenteconomic

agents. SectionIV

discussespohcy

optionsand

SectionV

concludes.II.

The Shock and

the

Financial

System

In this section I illustrate the

mechanism

though

which

externalshocks

aflFect the Chileaneconomy.

I organize the discussionof

the role playedby

theseshocks

and

their amplificationmechanisms

around

demand

and supply

factors affecting thedomestic banking system

-

thebackbone of

the Chilean financial system.An

overview

of

the Chilean financial institutions ispresentedin

Box

1.

I focus

on

themost

recent cychcal episode, as thechanging

natureof

the Chilean financialsystem

makes

olderdatalessrelevant.//.1

The

External

Shock and

itsImpact

on Domestic

Financial

Needs

The

triggerof

themechanism

isillustratedinFigure 1.Panel(a)shows

thepathof

Chile'sterms-of-trade

and

the spread paidby

prime Chilean

instrumentsover

the equivalent U.S.Treasury

instrument.ItisapparentthatChile

was

severelyaffectedby

both

attheend

of

the 1990s.Panel

(b)offers abettermetricto

gauge

themagnitude of

these shocks.Taking

the quantities firom the1996

cvirrentaccount

as representativeof

those thatwould have

occurred

in theeconomy

absent

any

real adjustment, it translatesthem

into the dollar losses associated to thedeterioration in terms-of-trade

and

interestrates. In 1998, these lossesamounted

toabout

2%

of

GDP,

with

similarmagnitudes

for1999

and

2000.Box

1:

The

Chilean

Banking

Sector

Banks

are an important sourceof

financingfor Chilean firms.

The

composition offinancing (table A.l) is similar to that of

advanced European

economies. Unlike thelatter,

and

much

like theUS,

the maturity structure of Chileanbank

loans ismore

concentrated

on

the short end:57%

oftotalloans,

and

60%

of

commercial

loans, have amaturity of less than 1 year. In

summary,

Chilean banks look like

European

banks interms oftheir relativeimportance butlike

US

banks

in termsof

their focuson

shortmaturities.

Relative

importance:

Loans

versus

other instruments.

TableA.l:

The

relativeimportance ofbank

loans. Source offinancing Loans Equity

Bonds

Stock Flows43%

51%

54%

33%

3%

16%

Note: Participations built using the stocks at

December 2000. Flows were computed as the

difference in stocks between December 1999 and

December 2000 except for the flow of new equity,

which wasbuiltusinginformationonequity placement duringthe period.

Composition

of

Loans.

Chilean banks concentrate

most

of

theiractivity

on

firms.Commercial

loans represent around60%

of totalbank

loans(see Table A.2).

Adding

trade loans, about70%

oftotalbank

credit supply isdirected to firms.TableA.2:Compositionofloansbyuse.

Typeof loan Fracti(>noftotalloans

Commercial

60%

Residential

15%

Consumption

10%

Trade

10%

Other

5%

Source:SuperintendenciadeBancoseInstituciones

Financieras.

Composition

of

commercial

loans

by

firm

size.Chilean

banks

concentrate their lendingactivity

on

large fums,atleastwhen

firmsize is approximated

by

loan size.Around

65%

of thevolume

of

commercial

loans is allocated to loansabove

US$

1.The

relativeimportanceof

different loan sizes issummarized

inTableA.3.

TableA.3:

The

relativeimportanceofdifferentloansizes.

Loansize Fractionofthevolumeof commercialloans

Large

64%

Medium

14%

Micro

22%

Note: Large: all loans above 50,000 UF (around

US$ 1.4 millions (end of 1999 dollars)); Medium:

loansbetween10,000and 50,000

UF

(US$280,000 andUS$ 1,400,000); Micro: loansbelow 10,000UF

(US$280,000).

Source:Superintendencia deBancoseInstituciones

Financieras.

Banks

versus other

financialinstitutions.

''Computedusing the stock

ofloansinDecember 1999. Source Superinlendencia de Bancos e Jns/i/imones Financieras.

^ In Germany, for example, more that

70%

of the commercialloansarelongterm. In contrast,intheUS

short term loans account for about60%

ofnon-residentialloans.

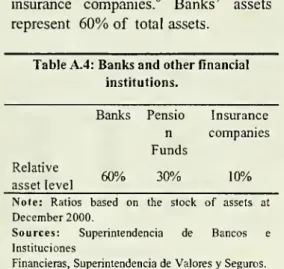

Banks

in Chile are importantwhen

compared

withotherfinancial institutionsas well. Table

A.4

compares

the total assetsof

banks, pension fiinds,and

insurance companies.^

Banks'

assets represent60%

of

total assets.TableA.4:Banks andotherfinancial

institutions.

Banks Pensio Insurance

n companies

Funds

Relative assetlevel

60%

30%

10%

Note: Ratios based on the stock of assets at

December2000.

Sources: Superintendencia de Bancos e

Instituciones

Financieras,Superintendencia de ValoresySeguros.

Domestic

and

Foreign banks.

Foreign

banks

presence is verysignificant. Table

A.5

shows

that loansby

foreignbanks

representedaround

40%

of total loans in 1999. It isimportant to note that Chilean

Banking

Law

does not recognize subsidiariesof

foreign

banks

as partof

theirmain

headquarters.

TableA.5:DomesticandForeign

Banks

Domestic Foreign Relativeimportance (%) total loans)

58%

42%

Portfoliocomposition Loans80%

67%

Securities11%

14%

Foreignassets6%

15%

Reserves3%

4%

Note:RatiosbasedonDecember1999values.

Source:Superintendencia deBancoseInstituciones Financieras.

Total assetsisthesumoffinancialandfixedassets.

Fixedassets arenotincludedforinsurancecompanies. Nevertheless, fixed assets represent averysmall fractionoffinancialinstitutions' assets.

Figure1:ExternalShocks

(a) TefTTis otTradeand Sovereign Spread (b)TermsofTradeandInterestRateeffect(fixedquanlities) I1U1MJ

~>

' ^\

/

V

V

y

V

' \A

V

^s

-

1;\/

" •^y

_^ / <• ——

~- _._.^.• ' i 1 I 1 i-1. i \ '^ I i \ '^ s s 1 ? i i 1 s—

./',^

Hi

fiHi

f

-4

< ^'"' 1 [ TemaoltfjdB—-St»B3dEntnaEr»tea|HTT eHecl li.rnri.slram BffT^

Notes:Preliminarydata used for 1999and2000. TheyearlyFigure for2000 was computed multiplyingthe S quarters cumulative value by4/3. (a) Terms-of-tradeis the ratio ofexports price indexand import price indexcomputedbythe

CentralBank. Thesovereignspreadwas estimated asthe spread ofENERSIS-ENDESAcorporatebonds. The spreaddata for 1996wasestimatedbytheauthorusing informationfromtheCentralBankofChile, (b) Theterms-of-tradeeffectwas

computedas thedifferencebetweenthe actual terms-of-tradeandtheterms-of-tradeat 1996quantities. The interestrate effectwas computedinsimilar fashion

Source:BancoCentraldeChile.

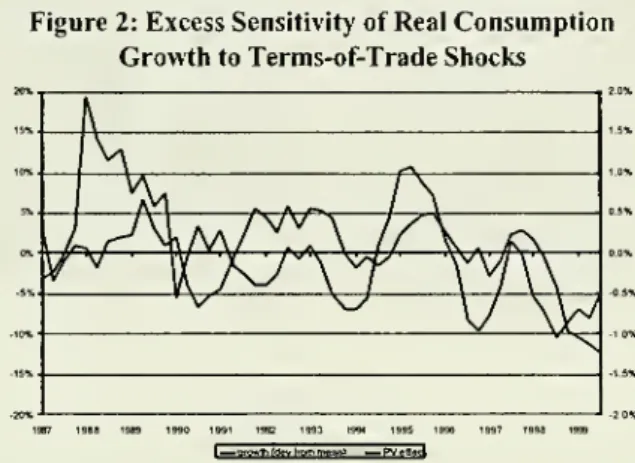

How

should Chilehave

reacted to this sharp decline innational income, absentany

significantfinancial friction (aside

from

thetemporary

increase inthe spread)? Figure2

hints the answer.The

thin line depictsthe pathof

actualconsumption

growth, while the thick line illustrates the hypothetical pathof

Chile'sconsumption

growth

ifitwere

perfectly integrated to international financialmarkets

and

terms-of-trade the only sourceof

shocks.'There

aretwo

interesting features inthe figure. First, there isa veryhigh

correlationbetween

Chile's business cycleand

shocks

to its terms-of-trade. This correlation is notobserved

in othercommodity

dependent

economies with

more

developed

financial markets,such

as AustraliaorNorway

(seeCaballero1999

or 2001).Second,

and

more

importantly for theargument

in this paper, the actualresponse

of

theeconomy

isbeingmeasured

on

theleftaxiswhilethatof

the hypotheticalisbeingmeasured

on

the right axis.Sincethe scale in theformer

isten timeslargerthanthatof

thelatter,itisapparentthat the

economy

over-reacts totheseshocks

by

asignificantmargin. Inpracticeshocks to the terms-of-trade are

simply

too transitory, especiallywhen

they are drivenby

demand

as inthe recentcrisis, to justify alarge responseof

the real sideof

theeconomy.^

The

Consumption growth is very similar to

GDP

growth for thiscomparison. Adding the income effect ofinterest rate shocks

would

not change things toomuch

as these were very short-lived. I neglect thepresence of substitution effects because there is no evidence of a consumption overshooting once

income

effect that ismeasured

in panel (b)of

Figure 1 should in principle, but itdoes

not inpractice, translate almostentirely inincreased

borrowing

from

abroad.Figure2:ExcessSensitivityofReal

Consumption

Growth

toTerms-of-Trade Shocks1SB7 13BS

I af.Brtif<Wl7W.m«in) PV^g^

Notes:consumptiongrowthfromIFS, copperprices(London Metal Exchange)fromDatastream,copperexportsfromMin. de Hacienda.

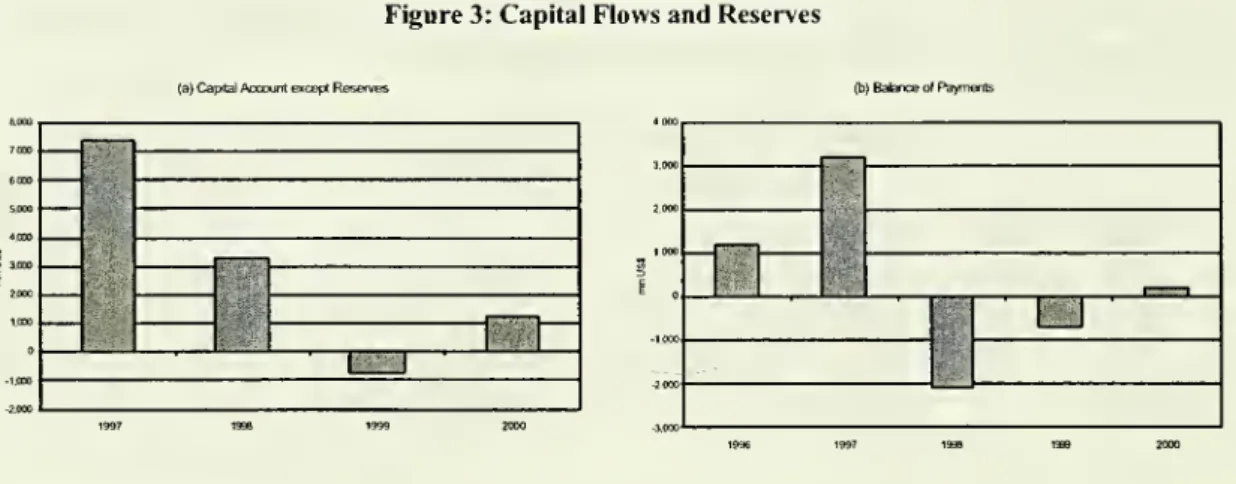

Returning to the late

1990s

crisis, panel (a)of

Figure 3 illustrates that international financialmarkets

not only did notaccommodate

the (potential) increase indemand

forforeign resources butactually capital inflows declinedrapidly overthe period. Panel(b)documents

thatwhilethe centralbank

offset partof

this declineby

injectingback

some

of

its international reserves, itclearly

was

not nearlyenough

tooffsetboth

the declinein capitalinflowsand

therisein externalneeds.

For

example,

the figureshows

that in 1998, the injectionof

reservesamounted

toapproximately

US$2

bilhondollars. Thisiscomparable

tothedirectincome

effectof

the declineinterms

of

tradesand

rise in interest rates,butitdoes

notcompensate

forthe declinein capitalinflowsthat

came

with these shocks.'

The

price ofcopper has trends and cycles at different frequencies,some

ofwhich are persistent (seeMarshall and Silva, 1998). But there seemsto be no doubt that the sharp decline in the price ofcopper duringthelate 1990scrisiswasmostlytheresult ofatransitory

demand

shock brought aboutbytheAsian andRussiancrises.1wouldarguethatconditionalontheinformationthatthecurrentshockwas

a transitorydemand

shock,the univariateprocessusedtoestimate the present valueimpact ofthedeclineinthepriceof copperin Figure2, overestimatesthe extentofthis decline.Thelower declinein future pricesisconsistentwith this view.

The

variance ofthe spot price is 6 times the variance of 15-months-ahead future prices.Moreover,theexpectationscomputed fromthe

AR

processtrackreasonablywell theexpectationsimplicitinfuturemarketsbutfortheveryendofthesample,

when

liquiditypremiaconsiderationsmay

havecome

into play.Figure3:CapitalFlowsandReserves

(a) CapitalAccount except Reserves (b)BabncEofPayments ecoD son •1C00 -2.000

"EE

'i^'\r

Ic-^

Source:BancoCentra!deChile

How

severewas

themismatch between

the increase inneeds

and

the availabilityof extemal

financial resources? Figure

4a

has a back-of-the-envelope answer. It graphs the actual currentaccount (lightbars)

and

the current account withquantities fixedat1996

levels(darkbars).At

the trough, in 1999, the actual current account deficit

was

around

US$4

bUhon

smaller thanwhat

one

would

have

predicted using only the actualchange

in terms-of-trade.Moreover,

thisdollaradjustment underestimates the quantityadjustment

behind

it,as the deteriorationof

terms-of-trade typically

worsens

the currentaccountdeficitforany

pathof

quantities.The

importance

of

thisprice-correctioncan

be

seen inpanel (b),which

graphs the actual currentaccount (hghtbars),

and

the currentaccount

at1996

prices (dark bars). Clearly, the lattershows

asignificantlylargeradjustmentthanthe former.

Figure4:

The

CurrentAccount(a)CunentAccajntand CuiTent Accountat1996quantities (b)CunGnt Account(actualandh19g6pnc8s}

S^

t599 2000MCjTtrt /•aInviUSS\» Qjignt Arc|m«USl96il

Notes: (a)Thecurrentaccountat1996quantities was computedbymultiplyingthe1996quantitiesby eachyear'sprice indicesforexports,importsandinterestpayments. Theothercomponents ofthecurrentaccountwerekept at currentvalues,

(b) Thecurrentaccountin 1996priceswas computedbymultiplyingthe1996pricesby each year'squantities.Source:

BancoCentraldeChile

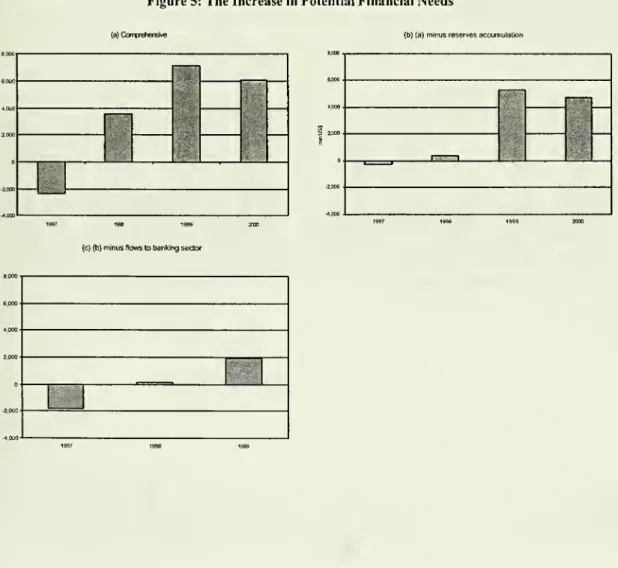

Figure 5 reinforces the

mismatch

conclusionby

reportingincreasingly conservative estimatesof

path

of

thechange

inpotential financialneeds

stemming from

the declinein temis-of-tradeand

capital inflows,and

the increase in spreads. Panel (b)subtractsfrom

(a)the injectionof

reservesby

the central bank, while panel (c) subtractsfrom

(b) thedechne

in capital inflows to thebanking

sector.We

can

seefrom

this figurethatthe increase in financialneeds

for1999

rangesfrom

about$2

bilhons tojustabove $7

billions. Regardlessof

theconcept

used,themismatch

is large, creating a potentially large surge in the

demand

for resourcesfrom

the domesticfinancial system.

The

differencebetween

panel (b)and

(c), as well as the next sectionmore

extensively,

show

that thelatter sectornot only did notaccommodate

this increase indemand,

butalsoexacerbatedthe financialcrunch.

Figure5:

The

IncreaseinPotentialFinancialNeeds(s)CuTprfiensTi/e (b) {a)minusreservesaccumulation

1 6.0X 4,000 1 -S?:;-:C S -2.000

w

^^^^^^^^^^(c)(b)minusflews tobankingsetior

Notes:Panel(a) corresponds to the sum ofthe terms-of-trade effect, the interestrate effect, andthe decline in capital

inflows. Boththe terms-of-tradeandthe interestrateeffectsaremeasuredat1996quantities. Thedeclineincapitalflows correspondsto thedifferenceofthecapitalaccountexceptreserves with respecttoits1996value. Panel(b)subtractsfrom

(a)thenetchangein CentralBankreserves.Panel(c)subtractsfrom panel (b)the net increaseinflows tothe banking

sector. Source:BancoCentraldeChile

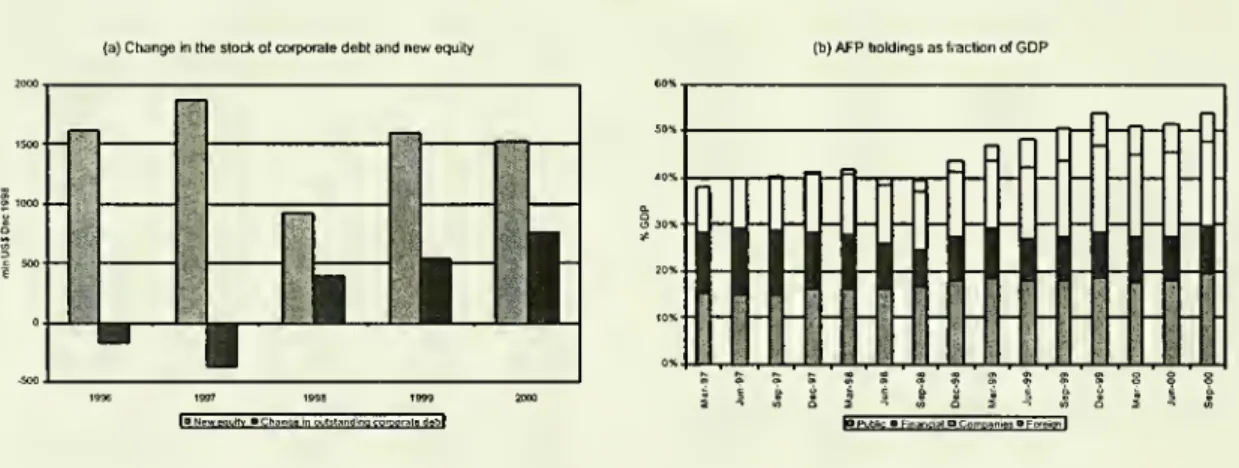

To

conclude this section. Figure 6 illustrates otherdimensions

that could have, but did not,smooth

thedemand

for resourcesfrom

resident banks.Panel

(a)and

(b) carry the relatively"good"

news.The

former

panelshows

that issuesof

new

equityand

corporatebonds

did notdecline very sharply, although they hidethe fact that the required

retum

on

these instrumentsrose significantly.

The

latterpanel illustrates that while theAPPs

increased their allocationof

flmds to foreign assets during the period, this portfoho shift occurred

mostly

against publicinstruments.

However,

thisdeclineprobablytranslated intoalargeplacement of

publicbonds

on

some

othermarket

or institution thatcompetes with

the private sector, likebanks

(see thediscussionbelow). Panel (c),

on

the other hand, indicates that retained earnings, a significantsource

of

investment financing to Qiilean firms, declined significantly overthe period.^ Finally,panel (d) illustratesthat

workers

did not helpaccommodating

the financial bottleneckeither,asthelaborshare rosesteadilythroughoutthe period.

Figure6:OtherFactors

{a)Changeinthestock ofcorporatedebtandnewequity (b)AFPholdingsas fracfion ofGDP

_

I

|_

199G 1997 >998 1999

IBNewequJN ChanuBinoulsUntHno corporaiadflbl mPubBe•FinancialaComMriwBFCTCtijiI

Beforethecrises, in 1996, the stock ofretainedearningsrepresented

20%

oftotalassets forthe medianfirm. The difference between profits and dividend payments, a measure ofthe flow ofretained earnings, representedarounda

50%

oftotalcapitalexpendituresforthemedianfirmin 1996.(c)Retained Earnings

I

I

M

10%'.1

'^ 'IH

'

i_

=

;;;^;, -. iDFtow/Opcfabon iSiodt/ToB) |Notes: (a) Source: Bolsa deComerciode Santiago andSuperintendencia de Valoresy Seguros. Newequity valued at

issuanceprice, anddeflatedusing CPI. Thestockof corporatedebt outstandingwasalso deflatedbyCPI. TheDecember 1998exchangeratewas432 pesos perdollar, (b)Source: Superintendencia deAFP. Thevaluesareexpressedas afraction oftheyear'sGDP.(c)ThedataonretainedearningsarefromBolsa de Comerciode Santiago (SantiagoStockExchange)

andcorrespondto thestocksofretainedearning reportedin thebalancesheetsofallthe societiestradedinthaiexchange. Theyexclude investmentsocieties,pensionfunds,andinsurance companies. The flowvaluewas computedasthedifference

inthe (deflated)stocksatIandt-l. (d)Source:BancoCentraldeChile.

The

bottom

lineof

thissectionisclear: dxiringexternalcnmches,

firmsneed

substantial additional financialresourcesfi-omresidentbanks.11.2

The

(Supply)

Response by

Resident

Banks

How

did residentbanks

respond

to increaseddemand? The

shortanswer

is that theyexacerbatedratherthan

smooth

theexternal shock.Panel (a)inFigure

7

shows

thatdomestic

loangrowth

actuallyslowed

down

sharplyduringthelate90s,

even

as deposits kept growing. Thistighteningcan

alsobe

seen inprices inpanel (b),through

the sharp rise in the loan-deposit spread during the earlyphase

of

the recent crisis.While

spreads started to fallby

1999, therewas

a strong substitutiontoward prime

firms thatmakes

itdifficulttointerpret thisdeclineasalooseningin creditstandards(seebelow).Figure?:

The

CreditCrunch

{a)LoansandDeposits:BankingSyslem (b) InlerestRate Spreads(Annual%}

s /'""•' *»'

"

i a -—^->'/^

-=^""^

1_.^--^^

s 1 • 2 s $ i s ss • 1 1 5HI

11 S sit

H U

1^ 1 1 8 8 8 5Jl -l.CWC'---DB'OSnsNotes: (a) Loans: commercial, consumption, trade,andmortgages. Deposits: sight depositsandtime deposits. Thevalues were expressedindollarsofDecember 1998 usingtheaverageDecember1998 exchangerate(472pesos/dollar), (b) The 30-dayinterestratesare nominalwhilethe90-365are real(toafirst order, thisdistinctionshouldnot matter for spreads calculations).

Sources:BancoCentral,andSuperintendencia deValoresySeguros.

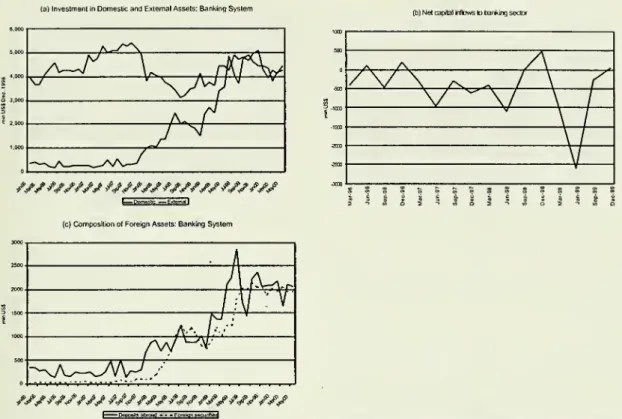

The main

substitutes for loans in banks' portfolios are public debtand

external assets.These

alternatives areshown

in Figure 8a, with the clear conclusion thatbanks

moved

their assetstoward

externalassets.Interestingly,the centralbank

policyof

fightingcapitaloutflowswithhighdomestic

interestrateswas

only temporarily successful (see the reversal during the last quarterof

1998). Instead, therise in interest rates duringthe Russianphase

of

the crisisseems

tohave

succeeded mostly

in slowingdown

the decline in banks' investment inpubhc

instmment,and

encouraged

substitutionaway

fi-om loans.Banks,

rather thansmooth

the lossof

externalfunding, exacerbated it

by becoming

partof

the capital outflows. In fact,while

panel (b)illustrates that the

banking

sector also experienced a large capital outflow during this episode,panel (c) reveals that

much

of

the net outflowwas

notdue

to a decline in their internationalcreditlinesorinflows,butrather

due

toan

outflowtoward

foreign depositsand

securities.Figure8:CapitalOutflowsbytheBanking System

(a)InveslmanlinDomesticandExternal Assets:BankingSystem

(b)Netcapitalrifbwsto tjankingsector

CZoomwIic

—

Ettemall(c)CompositionofForeign Assets:BankingSystem

Notes: (a) Domesticassets include CentralBanksecurities with secondarymarket andintermediatedsecurities. External

assetsare thesum ofdepositsabroadandforeignsecurities.Depositsabroadaremostly sight deposits in foreign (non-resident) banks.Foreignsecuritiesare mostly foreign bonds.

Sources:BancoCentralandSuperintendenciade Bancos.

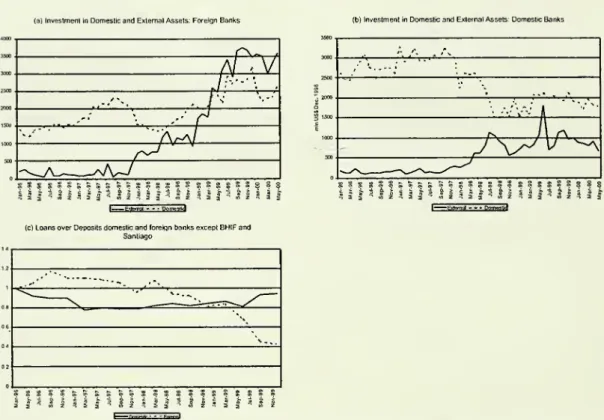

While most

residentbanks

exhibitedthispattern tosome

degree,itisresidentforeignbanks

thathad

themost

pronounced

portfoUo shifttowards

foreign assets. This is apparent inpanels (a)and

(b)in Figure 9,which

presentthe investmentindomestic

and

foreignassetsby

foreignand

domestic

(private) banks, respectively.While

allbanks

increased their positions in foreignassets, foreign banks' trend

was

substantiallymore

pronounced.

Moreover, domestic

banks

"financed" a larger fiaction

of

their portfoHo shiftby

reducing other investments rather thanloans. This conclusion is

confirmed

by

panel (c),which

shows

the pathsof

loans-to-depositratiosforforeign (dashes)

and

domestic

(sohd) banks.'"This figure excludestwo banks

(BHIF

andBanco

de Santiago) that changed firom domesticto foreignownership duringthe period.

The

changein statisticalclassificationtookplaceinNovember

1998forBanco

BHIF,andinJuly1999for

Banco

deSantiago. In thecase ofBanco

deSantiago, thetakeover operation tookplace in

May

1999byBanco

Santander (the largest foreign bank in Chile).Assuming

that the two banks weregoingtomerge,theChileanbanksregulatoryagency(Superintendenciade Bancos)orderedBanco

de Santiagotoreduceitsmarketpresence(thetwo banks hadajointpresence equivalentto29%

oftotalloans).The banksfinally decided notto mergeandthereforetheirjointmarketpresencehasremainedunaltered so

far.

Most

likely the confusion createdby the potential participafion limits did not help the severe creditcrunchthatChilewasexperiencingatthe time.

Figure9:

Comparing

Foreignand DomesticBank

Behavior(a)InvestmentinDomesticandExternalAssetsForeignBanks (b)InvestmentinDomestic andExternalAssets:DomesticBanks

'•. .'• . '"-/'•'..-:' '" -./vv A

.

/\.

—

-'J\y^^

^

^^s__—

x^-.-^-^

4 1 J -11 i s 1 1 [SSsS3SSSSSgsS?|SS

Exlomrf --•DomesBJ(c)Loansover Depositsdomestk:andforeignbanksexceptBHIFarxJ

Santiago

I I = 5 S I 3 I = « = I S I 5 I

Notes: Domestic banks donotincludeBancodelEstado. (a), (b)Domesticassets include CentralBanksecuritieswith secondarymarketandintermediatedsecurities.External assets arethesumofdepositsabroadandforeignsecurities.

Allconstant1998-pesoserieswere convertedtodollars usingtheaverageexchangeraleduringDecember 1998 (472 pesos/dollar), (c) Loans-to- depositsratiosarenormalizedtooneinMarch 1996. Deposit: sightandtimedeposits.

Loans: commercial, consumption, and tradeloans, andmortgages. Banco

BHIF

and Banco de Santiago, whichchanged fromdomestictoforeign duringtheperiod, were excludedfromthesample. Theinformationusedtoseparate thesetwobanksisfromtheBolsadeValoresde Santiago(SantiagoStockExchange).

The

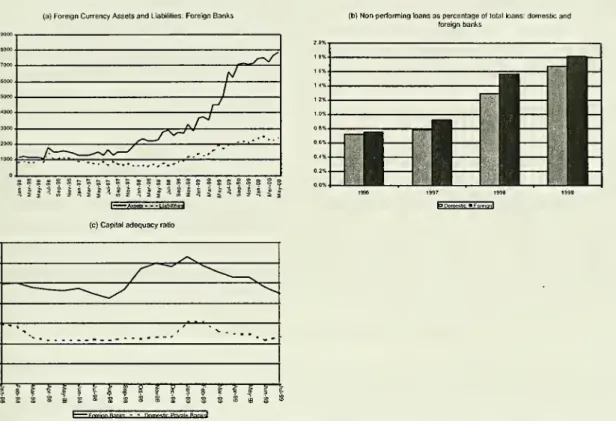

questionariseswhether

itisnot thenationalitybut otherfactors(e.g.,risk characteristics)of

the

banks

thatdetermined

the differential response.While

this is certainly atheme

tobe

explored

more

thoroughly,the evidenceinFigure 10 suggeststhatthisisnotthe case. Panel (a)shows

that foreignbanks

did not experience a rise in net foreigncurrency liabiUties that couldaccountforadditionalhedging.

When

compared

with domestic

banks, they did not experience asignificantly sharperrise in

non-performing

loans as is indicatedby

panel (b), orwere

affectedby

atightercapital-adequacyconstraintinpanel (c).Figure10:RiskCharacteristicsofForeign

and

DomesticBanks

(a)ForeignCurrencyAsselsandLiabilities:ForeignBanks (b)Nonperforming loans aspercenlageot totalloans:domesticand

foreign tianks

^^

1 f™n rJrl

,—y~^^~^••

p-. _^--N/s^

^

, 1 -•.-•-...,..---1 i 21s 1 • 1 i 113 1 r s 1 i 1 S g sSini

S5 Sill!?!!

S = 5 5 5 1 1—

-AMfltt •UnbBifiei (c)Capitaladequacyratio,^i^

"TTTTTTTT

TTT

Notes: (a)Foreign assets:foreignloans, depositsabroadandforeignsecurities. Foreignliabilities:fundsborrowed from abroad anddepositsinforeign currency, (b) ROE: ratio oftotalprofitsover capitalandreserves (as a percentage). Domesticprivatebanks donot includeBancodel Estado.

Source: SuperinlendenciadeBancoseInstitucionesFinancieras.

Foreign

banks

usually playmany

useful roles inemerging

economies

but theydo

notseem

tobe

helpingto

smooth

extemal shocks

(atleast inthemost

recent crisis). It isprobably

thecasethatthese banks' credit

and

risk strategies arebeing

dictatedfrom

abroad,and

thereisno

particularreasontoexpect

them

tobehave

toodifferentlyfrom

other foreigninvestorsduring thesetimes.In

summary,

during1999 -perhaps

theworst

fuU year during the crisis—

banks reduced

loangrowth

by

approximatelyUS$2

billions," while the increase in financialneeds

by

thenon-banking

privatesectorwas

about

US$2

billions aswell(see figure5c).Although

there aremany

general equilibrium issues ignoredinthesesimple calculations, it isprobably not too far-fetched toadd

them up

and conclude

that the financialcrunch

was

extremely large,perhaps

around

US$4

biUions (about5-6%

of

GDP)

in thatsingle year."

A

number

closetotwobilliondollarsisobtainedfromthedifferencebetweentheflow ofloansduring

1999(computedasthechangeinthestockofloansbetween

December

1999andDecember

1998)andtheflowofloansin 1996 (computedinasimilarmanner).

III.

The

Costs

The

impactof

the financial crunchon

theeconomy

iscorrespondinglylarge, especiallyon

smalland

medium

size firms.111.1

The

Aggregates

Figure2 already

summarized

the first-order impactof

the financialmechanism,

with adomestic

business cyclethatis

many

timesmore

volatilethanitwould

be

iffinancialmarketswere

perfect.This "excessvolatility"

was

particularlypronounced

inthe recentslowdown,

as isillustratedby

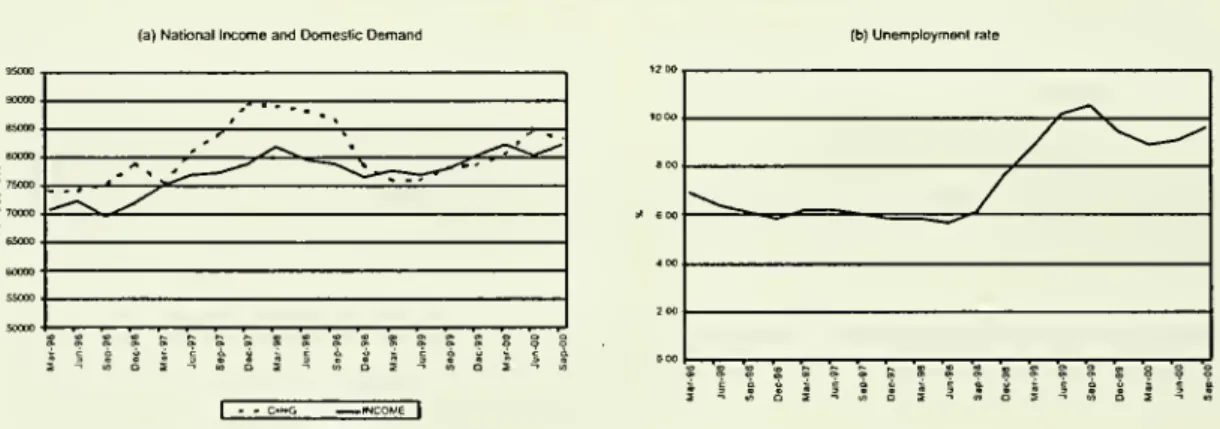

panel(a)inFigure 11.

The

pathsof

nationalincome

(soUd)and

domesticdemand

(dashes) notonly appearto

move

together, butthe latter adjustsmore

than the former,implying

that thelargely transitory terms-of-trade

shock

isnotbeing

smoothed

overtime. Panel (b) illustrates asharpriseinthe

unemployment

ratethathasyet tobe undone.

Figure1 1:Output,

Demand,

andUnemployment

(a}NationalIncomeand DomesticDemand (b)Unemploymentrate 95000. '~ '--., BOOOO ^-<.^ • -^^T"^.^^-^ 1 .•",

^^

^

^^.^

M L-^-^^/

E 65000. 60000 5O0O0 . , . 5-'(OQl-'inQ

3^mDl-'in05

-• --c.tH;Notes: (a)Seriesareseasonallyadjustedandannualized. Source:BancoCentraldeChile, (b)Source:INE.

Aside

fi^omthe directnegativeimpact

of

theslowdown

and any

additionaluncertainty thatmay

have

been

createdby

the untimely discussionof

anew

labor code, the buildup

inunemployment

and

its persistence canbe

linked totwo

additional aspectsof

the financialmechanism

described above. First, in the presenceof an

external financial constraint the realexchange

rateneeds

alargeradjustmentforany

given declineinterms-of-trade.'^As

aresultof

this, a big share

of

the adjustment fallson

the labor-intensivenon-tradable sector, as illustratedin panel (a)

of

Figure 12.Second,

going

beyond

the crisisand

into the recovery, the lackof

financial resources

hampers

jobcreation,aphenomenon

thatisparticularlyacute inthePYMES

(see below).

While

Ido

nothave

job creationnumbers,

panel (b)shows

that investment (solidline) suffered a

deeper

and

more

prolonged

recession than the restof domestic

aggregate'^The

largerrealexchangerateadjustment correspondstothe dualofthe financialconstraint. See Caballero and Krishnamurthy(2001a).

demand

(dashed line). This is importantbeyond

itsimpact

on

unemployment,

as it also hints atthe

slowdown

of

one of

themain

enginesof

productivitygrowth: therestmcturingprocess. If theU.S. is

any

indicationof

the costsassociatedtothisslowdown

inrestmcturing—

possiblya veryoptimistic

lower

bound

for the Chilean costs—

thismechanism

may

add

a significantproductivityloss that

amounts

toover

30%

of

theemployment

costof

the recession.'^Figure12: Forced and DepressedRestructuring

(a)GDPtratjeableandnorvlradeable (b)Evohjlion of flomestrcdemand

t-.RCS1

—

=FBglNotes: (a)Series are seasonally adjustedandnormalizedto one in March 1996. Tradable sector: agriculture,fishing,

mining, and manufacturing. Non-lradable sector: electricity, gas and water, construction, trade, transport and

telecommunications, andotherservices, (b) Series areseasonally adjusted, andannualized. Source: Banco Central de

Chile.

As

the external constrainttightens, alldomestic

assets that are not partof

international hquiditymust

losevalue sharplyinorderto offer significantexcessreturnstothefew

agentswiththe willand

hquiditytobuy

them. Figure 13ashows

a clear traceof

thisv-pattem

in the Chilean stockmarket.

Panel

(b)isperhapsmore

interesting, asit illustratesthatforeign directinvestment(FDI)

increased

by

almost

$4.5 bilhon during 1999,and

created abottom

to thefire saleof domestic

assets.

However,

while

FDI

is veryuseful since it providesexternal resourceswhen

theyaremost

scarce, its presence duringthe crisis alsoreflectsthe severecostsof

the external financial constraintas valuableassets aresoldatheavy

discounts.See Caballero and

Hammour(

1998).Figure13:Fire Sales

(a)ValueofChilean stocks (index) (b)ForeignDreclInveslment (FDI)

llf-lMll-ll

"^'

i

I

—

r^AI 1996 1997 199B 1999 2000Notes:(a)IGPAisthegeneralstockprice indexoftheSantiagoStockExchange.Sources:Bloombergand BancoCentral deChile

(b)GrossFDIinflows.Source:BancoCentraldeChile.

III.2

The

Asymmetries

The

realconsequences

of

the external shocksand

the financial amplificationmechanism

are feltdifferentlyacross firms

of

different sizes.Large

firms aredirectlyaffectedby

the externalshock

but

can

substitute their financial needs domestically.They

are affected primarilyby

priceand

demand

factors.The

PYMES,

on

the other hand, arecrowded

outfrom

domestic

financialmarkets

and

become

severelyconstrainedon

the financialside.They

arethe residual claimants --and

to a lesser extent, so are indebtedconsumers

—

of

the financialdimension of

themechanism

described above.Figure 14 illustrates

some

aspectsof

thisasymmetry,

startingwith panel (a)thatshows

thepathof

the shareof

"large"loans asan

imperfectproxy

forresidentbank

loansgoing

to large firms.Together

with panel (b),which shows

a sharpincreaseintherelative sizeof

large loans, ithintsatasubstantial reallocation

of

domestic loanstoward

relativelylarge firms. In thepoUcy

sectionI

win

arguethatsome

of

thisreallocationisKkelytobe

sociallyinefficient.Figure14:Flight-to-Quality

(a)Shareofbrge toansintotaJloans (b)Averagesizeofsmatlandlarge loarw

I Strml •- •Largal

Notes: (a)Large loans: largerthan 50000 UF; Smallloan: greater than 400UF but less than 10000 UF. (b) The averagesizecorrespondstothestockofloansineachclassdividedbythenumberofdebtors.

Source:SuperintendenciadeBancoseInstituciones Financieras.

The

next figure looks at cxDntinuing firms fixDm theFECUs.'''

Despite allof

these firms beingrelatively large

pubhcly

tradedcompanies,

one can

already see important differencesbetween

the largestof

them

and

"medium"

size ones. Figure 15shows

the pathof

medium

and

large firms' bank-Uabihties (normalizedby

initial assets) during the recentslowdown.

It is apparentthat larger firms fared better as

medium-sized

firmssaw

their levelof

loans fiozen throughout1999. Perhaps

more

importantly, since thesum

of

loans tomedium

and

largefirms rose duringthis period, while total loans declined throughout the crisis, the contraction

must

have

been

particularly significant insmallerfirms (thosenotinthe

FECUs).

FECU

istheacronymforFichaEstadistica Codificada Uniforme, which isthename

ofthe standardizedbalance sheet that every public firm in Chile is required to report to the supervisor authority

{Superintendenciade Valores

y

Seguros) on a quarterly basis.Our

database contains the information onthose standardizedbalance sheets forevery publicfirm reportingto the authoritybetweenthefirstquarter

of1996 andthefirstquarterof 2000.

Figure15:

Bank

DebtofPubliclyTraded FirmsBy

Size(a)Bankliabilibesofmedium andlarge Hrnis

I Mft.ftjm--[jmal

Notes: (a) Data source:

FECU

reported by all listedfirms to the Superintendencia de ValoresySeguros. The sample includes allfirms that continuously reported information betweenDecember1996andMarch 2000. Withinthissample, themedium (since theyare largerthan firms outsidethesample)sizefirms are those withtotalassetsbelowthemedianleveloftotal assets in December 1996. Theseries correspondto the totalstock of bank

liabilitiesat all maturitiesexpressedin 1996pesos, dividedbythe total levelofassetsin

December1996). Thenominalvaluesweredeflated usingtheCPl. Thetotallevelofassets

in December 1996 was VS$788 millions for the group ofmedium size firms, and US$59,300millionsforthegroup oflarge firms

.

In

summary,

despite significant institutionaldevelopment

overthe lasttwo

decades,the Chileaneconomy

is stUl very vulnerable to external shocks.The main

reason for this vulnerabilityappearsto

be

adouble-edged

financialmechanism,

which

includesa sharptighteningof

Chile'saccess to international fmancial markets,

and

a significant reallocationof

resources fi^om thedomestic fmancial

system

toward

larger corporations,pubhc

bonds

and,most

significantly,foreignassets.

iV.

Policy

Considerations

and

a

Proposal

The

previous diagnostic points attheoccasional tighteningof

an external financial constraint~

especially

when

terms-of-tradedeteriorate—

as the trigger for the costlyfinancialmechanism.

IV.1

General

Policy Considerations

Ifthisassessmentiscorrect,itcallsforastmctural solution

based

on two

building blocks:a)

Measures

aimed

atimproving

Chile's integration to intemational financialmarkets

and

the

development of domestic

financialmarkets.b)

Measures

aimed

atimproving

the allocationof

financial resources during timesof

extemal

distressand

acrossstatesof

nature.While

inpracticemost

stmcturalpoHcies containelementsof both

buildingblocks,Ifocuson

(b)asthe guidingprinciple

of

thepohcy

discussionbelow

because

(a), at least asan

objective, isalready broadly

understood

and

Qiile isakeady

making

significant progress along thisdimension through

its capitalmaikets reform program.

That

is, I focus primarilyon

theintemational

liquiditymanagement

problem

raisedby

the analysisabove.'^Intemational liquidity

management

is primarilyan

"insurance"problem

with respect to those(aggregate)

shocks

that triggerextemal

crises.Of

coursesolutions tothisproblem

must

have

acontingentnature.

The

first stepisto identifya—

hopefidly small—

setof shocks

thatcapture alarge share

of

the triggers tothemechanism

described above. In the caseof

Chile,terms-of-trade, the

EMBI+,

and

weather

variables, represent agood

starting point, but the particularindex

chosen

is a centralaspectof

thedesignthatneeds

tobe

extensively explored beforeitisimplemented.

The

second

step is to identify the ex-post transfers (perhapstemporary

loans rather thanoutright transfers) that are desirable.

At

abroad

leveltheseare simply: i)From

foreignerstodomestic

agents.v)

From

lessconstraineddomestic

agentstomore

constiained ones.At

a genericlevelthesetransfersare clear,butin practice there isgreatheterogeneityinagents'needs

and

availability, raisingthe informationrequirements greatly. Itisthushighly desirable toletthe private sectortakeoverthe

bulk

of

the solution,which

begs

thequestionof

why

isitthatthis sector is not already

doing

asmuch

as is needed.The

answer

to this questionmost

Ukelyidentifiesthepolicy goals withthehighestreturns.

''

See Caballero(1999,2001)forgeneralpolicyrecommendationsfortheChileaneconomy,including

measurestype(a).

My

objectiveinthecurrentpaperisinsteadtofocusand deepenthediscussionofasubsetofthosepolicies,adding an implementationdimensionas well.

The

main

suspectscan be grouped

intotwo

types: supplyand

demand

factors.Among

thesupply factors,there areatleastthreeprominent

ones:a)

Coordination

problems.

The

absenceof

awell-defmed

benchmark

around

which

themarket can

be

organized.b)

Limited

"insurance"

capital.These

may

be

due

to structural shortages ordue

to afinancial constraint (inthe sense that

what

is missing is assets thatcan

be

crediblypledged

by

the "insurer," ratherthan actual funds duringcrises).A

closely relatedproblem, but withcoordination aspects as well, is that

an

insufficientnumber

of

participants in themarket

raisesthehquidity

and

collateralriskfacedby

the "insurers."

c)

Sovereign

(dual-agency)

problems.

While

contracts are signedby

private parties,government

actions affect thepayoffsof

these contracts.'^Among

thedemand

problems,one

should consideratleastthreesourcesof

underinsurance:a)

Financial

underdevelopment.

This leads to a private undervaluationof

insurance withrespect to aggregate shocks.

The

latter depresses effective competition for domesticallyavailable external liquidity at times

of

crises, reducing the private (but not the social)valuation

of

internationalliquidityduringthese times.'^b)

Sovereign

problems.

Imphcit(free)insurance. c)Behavioral problems. Over-optimism.

In

my

view, domestic financialunderdevelopment

is still aproblem

in Qiile,which

givesrelevance to

demand

factor (a)and

to supply factor (b) as it reducesthe sizeof

the effectivemarket.

The

bulk

of

the solution to thisproblem

shouldbe pursued

through financialmarket

reforms. In the

meantime, however, an

adequateuse

of monetary and

reservesmanagement

poUcy

may

remedy some

of

theunderinsurance impUcationsof

this deficiency. Ibriefly discuss the general featuresof

thispoUcy

in thenext section.A

more

extensive discussioncan

be found

inCaballero

and Krishnamurthy

(2001c).Similarly,

demand

factor (c)seems

tobe

a pervasivehuman

phenomenon

(see forexample

Shiller 1999),whose

macroeconomic

impUcationscan

alsobe

partlyremedied with

theabove

policy.The

lattermust

be

done

with great care not to generate a sizeabledemand-(b)

typeproblem,

which

isotherwise notlikelytobe

present inany

significantamount

inthecaseof

Chileand

neitherissupply-(c).This leaves us with supply-(a) as the

main

focusof

thepoUcy

proposal,which

I discuss extensivelyinsectionTV.3."

See,e.g.,Tirole (2000).

"

SeeCaballeroand Krishnamvirthy (2001a,b).IV.2

Monetary

Policy

as

a Solution

to

the

Underinsurance

Problem

Figure 16 provides a stylized characterization

of

an

external crisesof

the sort that 1have

described

up

tonow.

The main problem

duringan

emerging market

crisis is well capturedby

the presence

of

a "vertical" external constraint.That

is, external crises are timeswhen,

at themargin, it

becomes

very difficult formost

domestic

agents to gainany

access to internationalfinancial

markets

atany

price.As

a resultof

this, international liquiditybecomes

scarceand

domestic

competition for these resources bidup

the"doUaf'

-costof

capital, f^,above

the international interest rate facedby

prime

(international) Chilean assets, /*.The

dualof

thiscrunchisasharp fallininvestment.

Figure

16:External

Crisist

7*I^

InvestmentIt is important to clarify a

few

aspectsof

this perspectiveof

crisis thatseem

tohave caused

some

confusioninthepast:a) Particularly in thecase

of

Chile, the risein sovereign (orprime

firms') spreadisnot

ameasure

of

therisein thedomestic

(shadow

or observed) ratef

; rather, it representstherisein/*,

which

inturnmay

tightenthevertical constraint.b) It

needs

notbe

the casethatthecountryliterally runs outof

intemational liquidity forthevertical constraint to bind for small

and

less thanprime

firms. In fact in Chile totalscarcityis

seldom

thecase.But

it isenough

thatprime

firms,banks,and

thegovernment

perceivethatthere isasignificant

chance

that a severeexternal crisismay

lie ahead, forthem

todecidetohoard

some

theintemational liquidity ratherthan lendit domestically,even

when

the currentdomestic

spread, i^- /*, ispositive.c)

Of

course, in practice the constraint isseldom

verticalbut '"diagonal." In that casethe logicof

the analysis that followsmust

be blended

with thatof

the standardMundell-Fleming

typeanalysis,butthe interestingnew

insightis stillthatwhich

related totheflataspect

of

the supplyof

funds.Ex-post-Optimal

Monetary

and

reservespolicy during

crisisBefore discussing optimal policy fijom

an

insurance perspective, it isworth

highhghting theincentivesthata central

bank

facesduringan

externalcrisis.The main

shortage experiencedby

the country isone of

international Uquidity (or "collateral,"broadly understood). Thus,

an

injectionof

international reserves into themarket

is a verypowerful tool: it directly relaxes the "vertical" constraint

on

investment in Figure 16,and

itstabilizesthe

exchange

rate.To

see the latter, note that duringan

external crisis international arbitragedoes

not hold since there isan extemal

credit constraint.Domestic

arbitrage,on

the otherhand,must

hold.Peso

and

dollarinstrumentsbacked

by

domestic

collateralmust

yieldthesame

expected

return (riskaversionaside).

Thus

thedomestic

arbitrageconditionis:(1) f'

=f

+(e-Ee).

where

f

denotes

de peso

interestrate, e thecurrentexchange

rate,and

Ee

theexpected

interest rate fornextperiod. Inwhat

follows,I take the latter as given, although interesting interactionsarise

when

this expectation is affectedby poUcy

as well (seeCabaUero

and Krishnamurthy

2001c).

Rearranging

(1)yieldsand

expressionfortheexchange

rate:(2)

e~Ee=

f' -f

,

which shows

thatasf

fallswith the reserves' injection,theexchange

rate appreciates forany

given peso

interest rate.The

effectivenessof

reserves' injectionsinboosting investmentand

protecting theexchange

ratecontrasts sharplywiththe impact

of an

expansionarymonetary

pohcy.The

reasonforthis isthatthe

main

problem

duringan

extemalcrisis isthelackof

intemationalnotdomestichquidity.Domestic

hquidityfacilitatesdomestic loansand hence

the roleof

f

intheinvestmentfunction inFigure 16 (given H',

lower peso

interest rates raise investmentdemand)

but, to a first order, itdoes

not relax the binding intemational financial constraint.As

a result,an

expansionary'*

Partofthereasonforthe"diagonal"shapeinpracticeisthatthecurrencydepreciates asI rises.If

exportsarean important dimensionofthecountry'sintemationalliquidity,thenadepreciation increases intemationalcollateral.

monetary

policy is not effective in boosting real investment in equilibrium. Instead, itsmain

impact

is to raisedomestic

competition for the limited international liquidity,and hence

f'.By

equation (2), the latter

means

that theexchange

rate depreciates sharply, as itmust

not onlyoffset thereductionin

f

(thestandard channel) butalsoabsorbthe rise int'.In conclusion, a central

bank

that hasan

inflationtargetand

isconcemed

with theimpact

thatthe

exchange

ratemay

have

on

it,will rathertightenmonetary

policy.Doing

otherwisedoes

nothave

much

realbenefitsduringthecrisisand can

lead to asharpexchange

ratedepreciation.Ex-ante-Optimal

Monetary

and

reservespolicy

during

crisisBut

ifthe centralbank

couldcommit

ex-ante to amonetary

policy,would

it stillchoose

to tighten during acrisis.The

answer

is no.The

reason forthis is thatthe primitiveproblem

is the private sector's underinsurancewith

respect to aggregate external shocks.The

amount

of

international Uquidity that thecountry has duringan

external crisismay

be

exogenous

atthe timeof

the crisis but it is not ex-ante. Itdepends

on

how much

internationalborrowing

occurredduring the

boom

years,on

the maturity stmctureand denomination of

that debt,on

thecontingent credit lines contracted,

on

the sectoral allocationof

investment,and

so on.Underinsurance

means

thatthesedecisions did notfully internalizethesocial costof

sacrificing aunit

of

international hquidity. Figure 17 captures thisgap

by

adding a social valuation curve toFigure 16.

The

gap

A-

i' captures theundervaluationproblem. In otherwords,

had

the privatesectorexpected value

of

aunitof

hquiditybeingA

asopposed

to i^ , theywould

have hoarded

more

intemational Uquidityand

the verticalconstraint duringthecrisiswould

have

shifted to theright.