H

l3>

IIII

* ft\ U- 13

9080 02874 5112

no-

6^—

o&

MIT LIBRARIES DUPL

Ill

!DEWEY

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

The

Consequences

of

Radical

Reform:

The

French

Revolution

Daron

Acemoglu

David Cantoni

Simon

Johnson

James

A.

Robinson

Working

Paper

09-08

March

19,

2009

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

withoutcharge from

theSocial

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection atThe

Consequences

of

Radical

Reform:

The

French

Revolution*

Daron

AcemogW

Davide

Cantoni*

Simon

Johnson^

James

A.

Robinson

11March

2009.Abstract

The

French Revolution of 1789had

amomentous

impact on neighboring countries.The

French Revolutionaryarmies during the 1790s andlaterunderNapoleoninvaded andcontrolled

large parts of Europe. Together with invasion

came

various radical institutional changes.Frenchinvasion

removed

thelegaland economicbarriersthathad

protected thenobility, clergy, guilds,and

urban oligarchies and established the principle of equality before the law.The

evidence suggests that areas that were occupied

by

the Frenchand

that underwent radical institutionalreformexperiencedmore

rapid urbanizationand economicgrowth, especially after 1850. There is no evidence ofa negative effect of French invasion.Our

interpretation is that the Revolution destroyed (the institutional underpinnings of) the power of oligarchiesand

elites opposed toeconomic change;

combined

with the arrival ofnew

economicand

industrialopportunities in the second half of the 19th century, this helped pave the

way

for futureeconomic growth.

The

evidence does not provide any support for several other views,most

notably, that evolved institutions are inherently superior to those 'designed'; that institutions

must

be 'appropriate'and

cannot be 'transplanted'; and that the civil code and other French institutions have adverse economic effects.Keywords:

institutions, civil code, guilds, democracy, oligarchy, political economy.*We thank JaredDiamond,RobertDixon, Niall Ferguson, Tim Guinnane,Peter Hall,Philip Hoffman,Joel

Mokyr, Sheilagh Ogilvie, Winifred Rothemberg, Jesus Villaverde, John Wallis, Peter Wilson andparticipants

inthe AmericanEconomicAssociation AnnualMeetingfor theircomments, and Camilo Garcia,Tarek Hassan, JuttaHoppe andMichael Kapps forexcellentresearch assistance.

fMassachusettsInstitute ofTechnology,DepartmentofEconomics,

E52-380, 50MemorialDrive, Cambridge

MA

02142, USA. e-mail: daron@mit.edu.'Harvard University, Department, of Economics, Littauer Center, Cambridge

MA

02138, email: can-toni@fas.harvard.edu.5MIT,

Sloan School of Management, 50 Memorial Drive, Cambridge

MA

02142, USA. e-mail: sjohn-son@mit.edu."Harvard University, Departmentof Government and IQSS, 1737 Cambridge Street N309, Cambridge

MA

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

1

Introduction

The

recent literature on comparative development has emphasized that underdevelopment iscaused by institutions that do not create the right incentives for economic growth.

But

there is disagreement about which specific institutions are important.Some

scholars emphasizeproperty rights (North and

Thomas,

1973, Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, 2001,Acemoglu

and

Johnson, 2005),some

legal institutions (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny, 1998) and others barriers to entry or oligarchies (Olson, 1982, Acemoglu, 2008).Another unresolved issue is whether institutions can be designed, and relatedly whether

they can be reformed externally.

Hayek

(1960) argued that institutions cannot be designedand

have to evolve organically (and that thiswas

the major reason for the inferiority of thecivil code), and a recent literature has claimed thatinstitutionshavetobe 'appropriate' to the

specific circumstances of countries (Berkowitz, Pistor and Richard, 2003a,b, Rodrik, 2007).2

These problems are amplified

when

such reforms are implemented 'Big Bang' style.Propo-nents ofthese views argue that enforced institutional change is likely to reduce prosperity, a claim that receives

some

support from the apparent failures of institutional reforms in LatinAmerica, Africa,the former Soviet

Union

inthe 1980s and 1990s,and

the recent experiences in Afghanistanand

Iraq.Not

allexternalreformare failures, however, as evidenced, for example, by thesuccessfulUS-imposed

reforms in postwarGermany

and Japan.Inthispaper

we

exploitthevariationininstitutionalreform createdinEurope

bytheFrench Revolutionto investigatetheconsequencesofradical, externally-imposedreformon subsequent economic growth. After 1792 French armies invaded and reformed the institutions ofmany

European

countries.The

lessonsfromthisepisode arecentral tosome

ofthe currentdebates oninstitutions. First, thepackageofreforms theFrenchimposedonareastheyconqueredincluded the civil code, the abolition of guilds

and

the remnants offeudalism, and the introduction ofequality beforethelawandtheunderminingof aristocratic privilege. Thesereforms thusclearly relate totheabove-mentioned debates. Ifoligarchieswerethe

main

barrier toeconomicgrowthin

Europe

at the turn of the 19th century, thenwe

would expect the Revolutionary reformsto unleash

more

rapid economic growth in affected areas. If, on the other hand,externally-imposed radical reform is generally costly or if the civil code creates major distortions, the

'Relatedly, adominant paradigm in economics maintainsthat institutions efficiently

—

albeitslowly—

adapttotheunderlying characteristics ofsociety (e.g., Demsetz, 1967, Djankov, Glaeser, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes

reforms should have negative effects.2

We

investigate the economic consequences ofthe French Revolution, and particularly, thereforms that itimposed on therest ofEurope, by usingtwo sourcesof historical data.

The

firstis cross-national. French armies invaded and reformed

some

parts ofEurope

but not others, sowe

can take those invaded as the 'treatment group'and

compare

their relativeeconomic

successbefore

and

after the revolutionary period. Nevertheless, there is a substantialamount

ofheterogeneity in this sample. For instance, the French tended to have a greater impact

on

countries in

Western

Europe compared

toEasternEurope and

eventhoughwe show

that there isno

evidence of pre-trends, this does not rule out potential unobserved differencesbetween

the treatment

and

control groups.In addition to cross-national variation,

we

alsoexamine

variation withinGermany.

Partsof

Germany,

primarily the westand

northwest, were invadedand

reformed, while the southand

the east were not. Thereforewe

can constructmore

comparable treatmentand

controlgroups within

Germany.

In addition,we

collecteddatato developseveral seriesofinstitutionalreforms across

German

polities. This enables us both to verify that the French did indeed reform various aspects of institutions and to utilize a two-stage least squares strategy, with French invasion as an instrument for institutional reform.Crucially for our identification strategy,

European

countries or parts ofGermany

did notchoose theFrench institutions, but those institutions were imposed on

them

first by the Revo-lutionand

thenby

Napoleon.3Moreover, territorial expansionby Frencharmies did not target places with a greater future growth potential. Instead, it

had

twomajor

objectives.The

firstwas

defensive, especially, in response to the threat of Austrian or Prussian (or later British) attempts to topple the Revolutionary regime.The

secondwas

expansionary. Thiswas

partlybecause ofresource needs of the French Republic, and partly because ofthe ideology of the

French Revolution. In addition, in the early 1790s, the French sought to establish France's

'natural frontiers.'4 Finally, the purpose of theinstitutional reforms ofthe French Revolution

These issues arealso related to the classic historicaldebate about the extent to which the institutions of the ancien regimeimpededcapitalismandeconomicgrowthandwhetherornot theFrench Revolutionplayeda constructiveordestructiveroleinEuropeanpoliticaldevelopment. Thehistoricaldebateabouttheconsequences

oftheFrench Revolution isalso about its impact onpolitical institutions and democracy, which isbeyond the scopeofthe current paper.

3

Inmostcases, therewerelocalJacobin (localradical) forces inthe countries invaded bythe Frencharmies, butthepresence ofsuch forcesdid not play amajorrole in determiningwhichcountresandcitieswere invaded bythe French. See, for example,Doyle (1989, Chapter9).

4

For example, the Revolutionary leader George Danton stated: "Les limites de la France sont marquees

was

not to foster industrialization per se, though theymay

have achieved this objective asa by-product of its major goal of destroying the grip of the aristocracy, oligarchy, and the clergyon political and economic power.5 Therefore, to a first approximation,

we

can think of the imposition ofthe institutions of the French Revolution as an 'exogenous treatment'and

investigate the economic implications oftheradical French reforms.

We

distinguish three definitions of 'French treatment:' (1) length of French occupation (in years), (2) adummy

for French control during the Revolutionary period prior to thetake-over of Napoleon in 9

November

1799 (18 Brumaire in the revolutionary calendar), (3)a

dummy

for French control during the Napoleonic periodup

until 1815. Using all threedefinitions,

we

find reduced-form evidence, both across countries and withinGermany,

thatour

main

proxy for economic prosperity, urbanization rates, increased significantly faster intreated areas during thesecondhalfofthe 19th century.

We

also supplement our cross-countryanalysis with Maddison's

GDP

data.Maddison

reports data for 'Germany' and 'Italy' prior to their unification, rather than the independent polities which subsequently unified.Much

of the variation in French treatment, however, is withinwhat

became

Germany

and Italy, so Maddison's data aremuch

less appropriate than the urbanization data for our purposes. Nevertheless, the findings withGDP

per-capita are similar, though on the whole weaker thanthose using urbanization rates.

Within

Germany,

we

provide supporting evidence using the expansion of railwaysand

the sectoral composition ofemployment, again suggesting that treated partsof

Germany

grew

more

rapidly—

in fact, industrializedmore

rapidly—

after 1850. UsingGerman

data,we

furthershow

a strong association between our measures of institutional reforms and French invasionor control. Using this association as a first stage,

we

also estimate instrumental-variables models, which indicate large effects of institutional reforms on subsequent growth. Overall,our results

show

no evidence that the reforms imposed by the French had negative economicconsequences.

On

the contrary, there is fairly consistent evidence from a variety of different cotedes Alpes. La, doivent finir les bornes denotre republique." (speech to National Convention, January 31,1793; quoted in Blanning 1983, p. 2). Grab (2003, p. 1) summarizes these motives and arguments as: "The

revolutionary governmentsjustified the occupationof foreign lands, using the theory of 'natural frontiers' and

declaringtheir intentionor liberating oppressed peoplefromtyrannical regimes." 5

Itis unlikely that the reforms were made specifically to encourage industrial growth. Most likely, no one

at theturn ofthe 19th centurycould haveanticipated the new technologies that wereto arrive afew decades

later. The exception to this statement istextiles. By 1800 the British and others had established some new

technologies that increasedproductivity(e.g.,inspinning) by anorderofmagnitude. Textilesarean important partofthe storyintheRhineland. discussedbelow,butthereisnoevidence that theFrenchchangedinstitutions in the Rhinelandspecificallybecause they foresaw great potential inthemanufactureof cloth.

empirical strategies that they

had

positive effects.An

important aspect ofourfindings is that the positive effects of institutional reforms are only visible in the second half ofthe 19th century.By

1850, treated areasshow

no differential growth or insome

specifications, slight (and insignificant) negative growth. This is not sur-prising.The

French reforms wereaccompanied

by

the disruptions causedby

invasionand

war

and

thisoften had quite destructive and exploitative aspects (see, for instance, Blanning, 1983,1986).

Grab

(2003, p. 1), for example, writes "the French armies requisitioned provisionsand

imposed

heavy war contributionson

occupied regions, thereby alienating their populations."Thus, the short-term impact of French invasion

may

have been negative.But

this is unin-formative about the impact ofRevolution-imposed institutional changes.The

most

plausible hypothesis—

and our starting point—

is that themajor

role of the reformswas

in creating an environment conducive to innovationand

entrepreneurial activity. Thisenvironment matteredmost

inthedissemination oftheindustrial revolution, which took place in ContinentalEurope

in the second halfofthe 19th century.6

Our

evidence of positive effects in the second half ofthe 19th century is consistent with this hypothesis.

There

are severalmain

conclusions from the evidence presented in this paper. First, theresults emphasize the role ofinstitutions and institutional reforms in economic development.7

Second, our findings are consistent with the view that the institutions of the ancien regime (guilds, feudal legacy in countryside, absence of equality before the law)

impeded

growth.However, the fact that French reforms

came

as a bundle does not allow us to assess therel-ative importance of, for example, the abolition of guilds

compared

to the abolition of feudalprivileges. Third, they do not support the view that civil code

and

French institutions havedetrimental economic effects.8 Fourth, the evidence does not support the thesis that insti-6

This argument is similar to that ofEngerman and Sokoloff (1997) and Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2002) whoargue that the divergence of institutions in colonial societies, which took place between 1500 and

1800, had littleeconomic impact untiltheage ofindustry.

Also noteworthy is that unlike theexperienceofEuropean colonialism in thewiderworld, the French did notsettle after 1815 inthe partsofEuropetheyreformedandtheydid not build schools,so duringthisepisode therewerelargechangesininstitutionswithculture,humancapitalandthe ethniccompositionofthepopulation remaininglargelyunchanged.

This statement is subject to two obvious caveats, firstly, that the comparison is not to the

common

law,and secondly, that it could be that the imposition ofthe civil code did have negative effects, but these were

more than compensated for by positive effects emanating from reforms simultaneously implemented with the

civil code. Thesecaveatsnotwithstanding, ifthecivil codeand other aspectsofFrench institutionswerehighly

damaging to growth, particularly ifimposed on other countries, we would expect to find significant negative

effects in treatedareas. In addition,apart from parts oftheworldthat voluntarilyadoptedthe civilcode,such

as Latin America, existing evidence on the consequences ofthe civil code comes from former French colonies which, likethe Europewe study, hadthecivil codeimposed simultaneouslywith other French reforms.

tutions are efficiently adapted to the underlying characteristics of a society

and

that evolvedinstitutionsare superior tothose that are designedor externallyimposed.

The

FrenchRevolu-tionary armies imposed

new

and radically different institutionsfrom those existing previously,and

did so in extreme 'Big Bang' style. Nevertheless, our evidence suggests that thiswas an

'economic success'.

Taken

together, these findings are interesting for thosewho

favor radi-cal institutional reforms.They

suggest thesemay

be successful, at least in certain historical contexts.The

success of the French reforms raises the question:why

did theywork

when

other externally-imposed reforms often fail?Most

likelythis is because thereforms weremuch more

radical than is typically the case.9

The

French reformed simultaneously inmany

dimensionsand weakened

thepowersof localelites,making

a returnto the statusquo ante largelyimpossi-ble.

Even

when

some

pre-revolutionelitesreturnedtopowerafter 1815, there wasapermanent

change in the political equilibrium. This scope

and

radicalism ofthe French reforms arecom-mon

with thepost-war reform experiences inGermany

and Japan and stand in contrast withmany

otherreform experiences.In additionto the literature on the implications and desirability of different typesof insti-tutionalreforms, discussed above, ourpaper is related to alarge literature on theconsequences oftheFrench Revolution.

The

debateon theFrench Revolutionwasstarted initsmodern form

by

thepamphlet

published by the conservative English philosopherEdmund

Burke in 1790,entitled Reflections on the Revolution in France, which initiated controversies about institu-tional change which continue today. In this pamphlet, Burke

condemned

the brutality, theinterventionist spirit and the radicalism ofthe French Revolution and argued:

"It is with infinite caution that any

man

should ventureupon

pullingdown

an edifice,which hasanswered inanytolerabledegreeforagesthecommon

purposesof society, oron building itup

againwithout having models andpatterns ofapproved utility before his eyes" Burke (1969, p.152).The

conclusion Burkedrew

from these eventswas

that the negative impacts of the French Revolution would be felt not only in France and not only in its immediate aftermath, but would potentially change the world formany

more

decades oreven centuries to come.On

the other side, the positive reception ofthe French Revolution was as enthusiastic asBurke's condemnation.

Thomas

Paine, inabook

that would subsequentlybecome

aclassic for See Acemoglu and Robinson (2008) fora model inwhich limited reforms canbecounterproductive.the democratization

movements

ofthe 19th-century Europe,The

Rights ofMan,

responded toBurke

in 1791. Paine hailed the French Revolution as the harbinger offreedom and equalitybefore the law, a role that it achieved

by

demolishing the ancien regime. Paine argued:"It

was

. . . against the despotic principles ofthe government, that the nationrevolted.

These

principleshad

. . .become

too deeply rooted to be removed,and

the

Augean

stable of parasitesand

plunderers tooabominably

filthytobe cleansed,by

anything short ofa complete and universal revolution" Paine (1969, p. 69).According to Paine, the French Revolution

was

exactly the kindofradical institutional reformnecessary to break the hold on land

and

people exercised by the ancien regime, whichwas

not only morally abhorrent, but also the source of significant economic inefficiencies.

The

Revolutionwould

therefore pave theway

formodern

freedomsand

democratic institutionsby

removing serfdom, aristocratic privileges, the Church's domination over politics and land,

and

inequity before the law.

The

debatebetweenBurke and

Painehas not beenresolvedby

academic researchand

thereis no consensus about the economic consequencesofthe French Revolution.

On

the one hand,many

economic historians, likeLandes

(1969, p. 142), view the French Revolution as "apo-litical roadblock" to technological adoption for Continental countries,

and

conclude that as aconsequence ofthe Revolution, "thegap in technique [between the Continent

and

Britain]had

widened, while

most

ofthe fundamental educational, economic,and

social obstacles toimita-tion remained" (Landes, 1969,p. 147). Similarly, Buystand

Mokyr

(1990, p. 64, 74) write: "itis our contention .. . that the

Dutch

economy

in the years ofthe Frenchand

NapoleonicWars

was

anotherexample

ofa smallopen

commercialeconomy whose

prosperitywas

disruptedby

world events . . .

The

French period . . . [was] disastrous for theDutch

economy." Crouzet's(2001,p. 121) viewissimilar, noting "theFrench Revolution

and

thewarsthat followed greatly slowed the transfer oftechnology."101

Withinthe history profession theeconomic impact ofthe French Revolution hasbecome inexorably

inter-twined withtheMarxistinterpretationofthe revolutionasmarkingthe'riseofthebourgoisie'. Most historians nowrejectaMarxist interpretationofthe Revolution, but havenot articulated analternativeassessment ofits

implications. Other economichistorianssimplyignore the Revolution. Intheliteratureon19thcenturyGerman

industrialization, forexample,though itis

common

toarguethattheStein-HardenbergReformsinPrussiaafter1807, which were induced by the defeatof Prussiaby Napoleon at Jena, helpedto modernizeagriculture and

facilitatethe reallocation of laborto industrial areas (e.g.,Tilly, 1996), littlemention ismadeofany potential impact of French institutional reformsin Germany. The institutional reform most mentioned isthe formation

On

the other hand,many

other economic historians also agree with Mokyr's assessmentsthat "the Revolution's long-term effect was to clear

up

the debris of the ancien regimeon

the Continent, thus assuringEurope's ability eventuallyto follow Britain inrevolutionizing its

productive system" (1990, p. 259), and that "the French Revolution

and Napoleon

installedmore

forward lookinggovernments inEurope" (1990, p. 253).Even

Landes,who

generallyem-phasizes the negative effectsofthe Revolution, also mentions in passing that such institutional changes as the abolition of guilds were beneficial (1969, pp. 144-145).

n

The

restofthepaper isorganized asfollows. Section2providesanoverviewofthe historyofthe FrenchRevolutionandthesubsequentinvasion of

Europe

bytheFrench. Section3discusses our data. Section 4 provides country-level regression evidence investigating the reduced form effectoftreatment onour dependent variables. Section 5 looks atthe differencesin the growthexperience oftreated and untreated

German

polities. Section 6 concludes.2

The

Effect

of

the

French

Revolution

on

Europe

In this section,

we

provide a briefsketch ofcertain aspects of the French Revolution and thesituation in various neighboring countries

and

cities before the Revolution that are relevantto our investigation.

We

also recounthow

expansion by the French Revolutionary armiesand

later by Napoleon affectedthese areas.12 Further historical details are provided in Acemoglu,

Cantoni, Johnson and Robinson (2009).

The

Revolution was precipitated by a long-running fiscal crisis which led to the convening ofthe Estates-Generalin 1789 forthe first timesince 1614.The

initial meetingofthe Estates-General in Versailles onMay

5, 1789 ended with the decision to convene amore

powerfulbody, the National Assembly, which initiated a process of radicalization culminating in the

storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789.

The

newly-formed National Constituent Assemblyabolished feudalism

and

allofthe special privilegesand

rights oftheFirstand

Second Estateson

August

4, 1789. Thiswas

followedby theabolition ofthe Church's authoritytolevyspecialtaxes,

and

laterturning the clergy into employees ofthe state, thus starting the process ofthe separation ofchurch and state. It subsequently passed a constitution on September 29, 1791,"See also Crouzet (2001, p. 122), Cameron (1993, pp. 211-213) and Rosenthal (1992). Similarly, Rude

(1964), Kisch(1962), Trebilcock (1981), Doyle (1989), orGrab (2003) also arguethat the French reformswere

significant improvementsrelative tothe situation atthe time. Noneofthese workssystematically investigates

theeconomic consequences ofthe Revolutioneither in theshortorthe longrun.

12

This section draws on Doyle (1989), Palmer (1959, 1964), Rude (1988), Grab (2003), and Blanning (1983,

making

France a constitutional monarchy. This constitution alsoremoved

themajor

power

of the guilds inthe cities.The

radicalization ofthe Revolution led to the Terror which ended with the execution ofRobespierre

and

Saint-Just in July 1794. There followed a phase of relative stability, first inthe form of collective government under the Directory between 1795

and

1799,and

thenwith

more

concentratedpower

in the formofa three person Consulate, consisting ofDucos, Sieyesand Napoleon

Bonaparte. Already during the directory, theyoung

general Bonapartehad

become famous

for his military successesand

statesmanship. His influencewas

only togrow

after 1799.

The

Consulate soonbecame

personal rule by Napoleon,who

initially engineered his election as First Consul inNovember

1799 with the coup ofthe 18th ofBrumaire

and

thendeclared himself

emperor

in 1804.The

years between 1799 and the end of Napoleon's reign,1815, witnessed a series ofgreat victories, including those at Austerlitz, Jena-Auerstedt,

and

Wagram,

bringing continentalEurope

to its knees.They

also allowedNapoleon

to impose hiswill (and his legal code) across awide swath ofterritory.

2.1

Europe

Before the Revolution

Before the age ofthe French Revolution,

much

ofEurope was dominated by

two kinds ofoli-garchies,the landed nobilityinagriculture

and

the urban-based oligarchycontrollingcommerce

and

various occupations, with explicit or implicit entry barriers.By

the end of the eighteenth century, feudalism in itsmost

rigid formhad

disappeared inmany

parts ofEurope, but a lot of its remnants remained.Serfdom

—

the system through which peasants are tied to the landand

cannot sell their labor in free markets or engage inother occupations without the permission of landowners

—

still continued inmuch

of EasternEurope

(seeBlum,

1978), while it had been replacedby

various formsoftaxes and tributes tolandowners in other areas, which could nonetheless be quite onerous.13 For example, in the

Rhineland, the first area in

Germany

tocome

under French control, an attenuated form ofserfdom (Grundherrschaft) which severely restricted freedom of

movement

was

still practiced(Blanning 1983, pp. 20-21).

Grab

(2003, p. 86) states: "Their conditions were worse east of the Elbe where serfdom still prevailed.But

even inmany

western regions where serfdomhad

declined

and

peasants were freerand

better off, they were often still subject to landlords to13

Sinceone could be concerned that including Eastern Europe in the sample leads the control group to be very heterogeneous, in the empirical work we show that all our results hold when we restrict our sample to

whom

theyowed

seigneurial fees and laborobligations. In additionthey had to pay taxesand

support their parishes and village communities."

Even

when

serfdom inits classic form was absent, various rights ofthe nobility and clergy created a very unequal political and economic situation in rural areas. These groupswere

frequently

exempt

fromtaxationby the stateand

enjoyed the rightoftaxationofthepeasants under their control. Lenger (2004, p. 92), for example, describes this as: "besides the origi-nal obligations to provide servicesand

dues to the lord the agricultural labor forcewas

also burdened with personal servitude".He

continues:"In the small territoryofNassau-Usingen around 1800 there were no less than 230

different payments, dues,

and

services that thepeasants livingtherehad

to provideto the lords.

Dues

included . .. the 'blood tithe' to be paid after an animal wasslaughtered, a 'bee tithe', a 'wax tithe' ... as well as large fees

owed

to the lord whenever a piece ofproperty changed hands." (Lenger, 2004, p. 96).Moreover, inplaceswhere

some

formof seigneurial privilege remained, itwas usualfor nobilityand

clergy tobe subject to different lawsand

courts.The

principle ofequality before the lawwas

quite alien (or even revolutionary) inmost

ofEurope

in 1789.The

urban oligarchy was perhaps evenmore

pernicious to industrialization.Almost

allmajoroccupationswere controlled by guilds, significantly limiting entry into those professions

by others, and often restricting adoption of

new

technologies (see White. 2001, for examples from French guilds). For example, Cipolla (1970) argues that the guilds stopped innovationin Italy, in particular they forbade the production ofexactly the type oflower quality goods

that were taking their markets. In Venice (p. 206) "for almost the whole ofthe 17th century,

the statutes of the guild prevented cloth from being

made

of the English andDutch

type, whichhad had

somuch

success on the internationalmarkets. Moreover, the guild statutes notonly

demanded

the production ofatraditional type ofgoods, but also prevented the adoptionof

new methods

ofmaking

these old products." Braudel's (1992, p. 136) and Rapp's (1976)analysis is similar. For the case of

Germany,

a similarargument

ismade

by Ogilvie (2004,2007) and Kisch (1989) for the Rhineland. In the major cities of Cologne and

Aachen

theadoption of

new

textile (spinning and weaving) machines were significantly delayed because of guild restrictions. In addition,many

cities were controlled by a few families formany

generations, amassing wealth at the expense ofpotentialnew

entrants with greater ability or2.2

Under

the

Republic

Despite the fact that the French Revolution

was

immediately seen as threatening to Europe'selite,

war

—

the so-calledWar

ofthe First Coalition—

did not break out until 1792.14 Contrary to almost everyone's expectations, aftersome

early defeats, the armies of thenew

Republic were victorious in an initially defensive war. There were serious organizational problems toovercome, but particularly after the introduction of

mass

conscription (the levee en masse) inAugust

1793, the Frenchhad

a military advantage than verged on supremacy.Initial military success encouraged the Republic's leadership to

expand

France's borders,with an eye towards creating an effective buffer between the

new

Republicand

the hostilemonarchs

of Prussia and Austria.The

French quickly seized present-dayBelgium

and

theNetherlands (where ice famously allowed French cavalry to capture alarge part ofthe

Dutch

navy).

The

French also gained effective control overmuch

ofmodern-day

Switzerland. In allthree places, the French

had

strong control through the 1790s.Germany

was

initially hotly contested but by 1795 the Frenchhad

firm control over theRhineland (thewest or left

bank

ofthe Rhine),and

the Prussians were forced to recognize this fact undertheTreatyofBasle.15Between

1795and

1802, theFrenchfirmlyheld the Rhineland,but not any other part of

Germany.

In 1802 the Rhinelandwas

officially incorporated intoFrance.

Italy remained the

main

seat ofwar

in the second half the 1790s, with the Austrians asthe

main

opponents. Savoywas annexed

by France in 1792,and

a stalematewas

reached until Napoleon's invasionin April 1796. In his firstmajor

continental campaign, by early 1797Napoleon

had sweptup

almost all of Northern Italy, except for Venice (whichwas

takenby

the Austrians).

The

Treaty ofCampo

Formio, signed with the Austrians in October 1797,ended the

War

ofthe First Coalition and recognized anumber

ofFrench-controlled republicsin Northern Italy.

However, the French continued to

expand

their control over Italy even after this treaty.In

March

1798 the French invaded the Papal Statesand

established theRoman

Republic. InJanuary 1799, Naples

was

conqueredand

the Parthenopean Republic created.16With

the14

The initial reaction in European capitals was amazement but there was no perceived need to intervene. Thischanged with the execution ofLouis XVI. See Doyle (1989) for general background and Blanning (1986)

fora more detailed treatment. Esdaile (1995, 2001) and Ellis (2003) are succinct overviews ofall ofthe wars from 1792 to 1815, whileBlanning (1996) and Gates (1997) provide moredetails.

15

Partofthe broader 1795PeaceofBaslewith Prussia, Spain,and Hessen-Kassel.

16

exceptionofVenice (still Austrian), theFrench

now

controlled the entire Italian peninsularei-therdirectly (Savoy)or throughsatelliterepublics (Cisalpine, Ligurian,

Roman,

andPartheno-pean). There was further back-and-forth in the

War

ofthe Second Coalition (1798-1801), but this ended with the French essentially remainingin control.2.3

Institutional

Changes

Induced by

the

Revolutionary

Armies

Many

of themost

radical institutional changes were undertaken during the invasion of theFrench Revolutionary armies. This included the abolition of all the remaining vestiges of

serfdom and quasi-feudal land relations, the hold of the clergy over economic

and

politicalpower, the domination of the guilds in urban areas, and legal changes establishing equality before the law.

In Belgium

"The

clergy and the nobility, the two upper estates, enjoyedmany

privilegesand

possessed considerable wealth and politicalpower

. ..Urban

guilds and corporations, thedominant

element in the Third Estate, also possessed important privileges and controlled thetowns" (Grab, 2003, p. 75). France annexed Belgium in 1795

and

ruled for 20years. Equality beforethe lawwasestablished and seigneurialrights, thetithe, nobleprivileges, and the guilds were abolished; in fact, fromDecember

1796, anynew

French legislationbecame

applicable inBelgium

(Grab, 2003, p. 78).In the Netherlands (or United Provinces), the existing institutions were

more

those ofen-trenched urbanoligarchies inthe various cities. These oligarchieswereeffectively expropriated

by

the French and, after considerable upheaval, the Batavian Republic was established alongFrench lines (Grab, 2003, Chapter4).

In Switzerland, the situation

was

similar to the Netherlands. Before 1789, "Feudal priv-ileges persisted inmany

rural communities. Peasantsowed

theChurch

and landlords tithe, seigneurial fees,and

laborservices.Many

Swisslackedthe freedomtosettlewheretheywanted

to or choose the occupation they desired." (Grab, 2003, p. 113).

With

thecoming

ofRev-olutionary armies, existing oligarchs were dispossessed or forced to cede power, and feudal

privileges largely disappeared.

In

Germany,

the only real changes during this period were in the Rhineland (WestBank

of the Rhine). While the impact of the French on the Rhineland during the 1790s remains controversial, especially because ofthe great deal ofplunder and the resulting resentment by have had agreatimpact on some institutions inthe southofItaly,on whichsee Davis (1991, 2003) orGregory

the localpopulation mentioned above (see, e.g., Blanning, 1983, Doyle, 1989), the importance ofthe revolutionary reforms in Rhineland is not in question.

Even

acritic ofthe French, such as Blanning (1983), admits the significant institutional reforms undertaken by the French inthe Rhineland.

Most

significantly, in 1798 the seigneurial regime and the guilds wereabolished (Blanning, 1983, pp. 137and

155),and

this paved theway

to a relatively free labor market. This was a major reformand

meant

that master artisans could (and did) setup

their shopswhen

they wished to do so (Diefendorf 1980, p. 164). Equally important were the legalchanges. Forexample, the French created acommercial court in

Aachen

in 1794,and

followedwith similar courts elsewherein the Rhineland (Diefendorf, 1980, pp. 159-160),

which

were to play an important role in the creation ofcommercial and industrial businesses in the years tofollow.

InItaly, several

new

Republics wereestablishedwithFrench-styleconstitutions, parliaments(on a property-based franchise),

and

more

efficient systems ofadministration. Extensive aris-tocratic privileges were abolishedand

the notion ofequality before the lawwas

introduced inearnest for the first time (see Doyle, 1989, Chapter 15, Grab, 2003, Chapter 10, Broers, 1997,

2005).

2.4

Napoleon At

the

Helm

AfterNapoleon's takeover, the Frenchimpact spread

much

wider throughout Europe. In Ger-many, where the direct control ofthe Revolutionaryarmieshad

been limited tothe Rhineland,Napoleon

constructed astring ofsatellite buffer states on France'snortheastern border.There

were several iterations, but the big break point followed the Peace of Luneville (February

1801), with amassive reorganization ofthe territories that comprisedthe Holy

Roman

Empire

(roughly Austria and

Germany

in their 1914 borders).Much

ofthe astonishing variety oftheEmpire

disappeared—

literally hundredsofindependentstates, ecclesiastical territoriesand

freeimperial cities vanished

and

were consolidated into a cluster of larger kingdoms, principalities,and

duchies; ultimately, theirnumber

shrank to fewer than 40 states (Grab, 2003, pp. 89-90).The

main

beneficiariesweretheGrand

Duchy

ofBaden and

thekingdoms

ofWiirttenbcrgand

Bavaria (all in the South of

Germany).

These andmost

otherGerman

states except Prussiawere brought togetherin 1806 inthe Rheinbund,

known

in English asthe Confederation oftheRhine (see Schmitt, 1983).

into satellite states under his control.

The Duchy

ofBergon the rightbank

ofthe Rhinewas

formed in

March

1806 (it was supposed to be ruled by his infantnephew

Louis Napoleon),the

Kingdom

ofWestphalia (ruled by his brother Jerome) in August 1807,and

theDuchy

ofFrankfurt in February 1810 (it

was

planned that Napoleon'sstepson,Eugene

de Beauharnais,would inherit it). These were run by the French and persisted until the collapse following

Napoleon's invasion ofRussia. During this period Napoleon also took over parts ofNorthern

Germany,

including inDecember

1810 the annexation into France ofHamburg,

Liibeckand

Bremen

(Hanseatic cities) and the plains ofLower

Saxony, which would later comprisemost

ofthe

Kingdom

ofHanover.Elsewhere the French maintained their control over the

Low

Countries, and in 1808 in-vaded Spain. In ItalyNapoleon

re-created the Cisalpine (subsequently Italian)and

Ligurian Republics and created the satellitestate oftheKingdom

ofEtruria comprising the larger partofTuscany.

By

March

1802 the Frenchcommanded

all of Italyexcept again the Papal States, Naplesand

Venice.Piedmont was

annexed to France in early 1803, and in 1805Napoleon

turnedthe Italian Republicintothe

Kingdom

of Italy (1805to 1814)and

theLigurianRepub-licand

Parma

weremade

part ofFrance. In 1806, the French againinvaded southernItalyand

Napoleon installed his brother Joseph as the

King

ofNaples.The

Papal States were invaded by the French in 1808, andmost

was

annexed to France, forming the departments ofTiberand

Trasimene. In 1808, Josephwas

made

King

ofSpain, and theKingdom

ofNaples passedto Napoleon's brother-in-law, Joachim Murat.

2.5

Napoleon's

Reforms

Although Napoleonwas an

Emperor

seekingtosolidify hiscontrol, ruthlesslywhen

necessary, in France and throughoutthe French Empire, henonetheless continued toimplement the reformsinitiated by the Revolutionary armies (see Grab, 2003, Connolly, 1965, and Woolf, 1991).

As

Grab

(2003, p. xi) puts it: "Revolutionary France had initiatedmany

of these changes andNapoleon

exportedthem

throughout Europe." Napoleonhimselfsawthe impositionofthecivilcode (Code Napoleon) in the areas he controlled as his most important reform (Lyons, 1994,

p. 94). In practice Napoleon's institutional legacy outside of France is complicated, especially since he

was

more

inclined tocompromise

with local elites atsome

times, but inmost

placesthere

was

a genuine attempt to continueand

deepen the reforms brought by the Revolution.beendeeply involvedwiththe reformsofthe Revolutionaryperiod

and

seemstohaveshared the ideologicalcommitment

ofthe earlyreformers. Second, like them, he wished to build a series of buffer states around France. Finally, reformssuch as abolishing elites, feudal privilegesand

introducing equality before the law

undermined

existingelites andmade

it easier forNapoleon

to establish control over the areas rule he conquered.17

In

Germany, Napoleon

sustained the reforms already introduced into the Rhinelandpar-ticularly introducing the

Code

Napoleon. Kisch emphasizes the economic importance of this (1989, p. 212):"When

themany

strands of commercial legislation were subsequently con-solidated in the Code Napoleon, the Rhineland (on the left bank) was not only given amost

up-to-date legal framework, but also asystem ofgovernment in close

harmony

with the needsofa buoyantly industrializing society."

The

consequence ofall ofthese changeswas

the trans-formation ofthe Rhineland from an oligarchy-dominated areatooneopen

tonew

businessand

new

entrants. Insteadofthetraditional oligarchy, in 1810merchants/manufacturers comprised about halfthemembers

of Conseil General (municipal administrations) in leading Rhineland towns (Diefendorf, 1980, p. 115), and businesspeople were also well represented in the higher department-level Conseil General.Reforms

were also systematically introduced into theGerman

satellite kingdoms. Forexample, Connelly (1965, p. 184) notes that in the constitution of Westphalia, which

was

issued at Fontainebleau on

November

15, 1807,"... the king's subjects were guaranteed equality before the law and religious

liberty; serfdom

and

feudal rights were abolished; noble titles were affirmed, butwere to

command

no special rights, privilegesor offices. Taxes were to fall equallyon

allclasses inallpartsofthekingdom. Provisionwasmade

for aministry, councilofstate,

and

a parliament of onehundred

(seventy landowners, fifteen merchantsand

manufacturers, fifteensavantsand

distinguishedcitizens) . . . EffectiveJanuary1, 1808, the Code Napoleon

was

to be the civil law.The

judiciarywas

to be'independent' but

was

appointed by the king,who

could review his appointmentsevery five years."

He

later notes (p. 189) that "all vestiges of feudal law, together with seigneurial and church'Prussia'sdesire to establishits owncontrol seems to have been one ofthe reasonswhy

itdid not attempt todismantleFrench reformsinthe partsofWesternGermanythatittook overafter 1815 (seeFisher, 1903, pp. 380-381).

courts, disappeared in the first

months

of 1808" and "Allmen

were equal before the lawand

eligible for office." Although the political changes were not implemented (theparliamenthardly met), the economic changes were profound and

—

in this case and inmany

others—

largely irreversible.

In the Netherlands, Belgium,

and

Switzerland, Napoleon consolidated the changesbrought by the Revolution, with an emphasis on establishing (his) legalcode and a downplayingofany

move

towards democracy.18Napoleon'simpacton Spainis controversial. Napoleonacquirednominal controlover Spain

quite late (1808) and from thattime on he had considerable distractions in the form ofalmost

continualmajorwars.

The

Code Napoleonwas

supposedlyintroduced, butit isunclearwhether

it

was

ever properly implemented. There was also considerable popular resistance, abettedby

the British directly and through their base in Portugal, and by 1812 the French had lost effective controlsouth ofthe Pyrenees.

In Italy, the picture is similar with the Code Napoleon being implemented mainly in the North, but also involving certain profound changes in the South.

2.6

Persistence of the

French

Reforms

After the final collapse of Napoleon in 1815 the institutional reforms implemented over the previous 25 years suffered various fates. In our econometric analysis of

Germany we

specifi-cally code reforms throughout the 19th century so examine this issue empirically.As

a firstapproximation, the reforms were

most

clearly persistent in places where the old elites did notreturn, for example, in the areas of Napoleonic

Germany

that were ceded to Prussia at theCongress of Vienna. For instance,

Emsley

(2003, pp. 62-63) notes:"Yet

on

the leftbank

ofthe Rhine, in the departments annexed to France during the revolutionary decade, theCode became

firmly entrenched. Indeed, it was so well entrenched that, after 1815, the Rhenish elite successfullypreserved theCode

and resisted attempts of their

new

Prussian masters to introduce the PrussianAllgemeines Landrecht."19 ls

Napoleon also briefly invaded Portugal, but the French presence did not last long, partly due to British intervention.

We

thereforetreatPortugal aspart ofthe controlgroup,alongwithAustria(whereNapoleon alsohadmilitary victoriesbut never ruled directly).

19

SeeSperber(1989)and (1991) fordetailsontheRhinelanderstried (andsucceededfora long while)to hold onto the Code Napoleon andother progressive aspects ofthe Frenchlegacy.

Emsley's

argument

is that the French reforms fundamentally changed the political statusquo

in such away

as the eliteswho

benefitted from these institutions could sustain the.The

presenceofa

new

elitecreatedby thereformsand

determined tohang

ontothem

is alsocentralto the

argument

ofSimms

(2004, p. 39)who

sums

thisup

as:"In western

and

southernGermany

therewas

no going back to the feudalsta-tus

quo

ante.The

Prussian bureaucrats arriving in the newly acquiredRhine

Provincein 1815 found a population determined to hold ontotheFrenchlaw ... In

southern

Germany

the old corporate representationshad

permanently givenway

to parliaments

whose

lower houses were largely electedon

the basis of a property franchise;and

by 1820 all southernGerman

stateshad

constitutions guarantee-ing freedom ofconscience and equality before the law .. .The

genie of the reformmovement

—

freedom ofmovement,

the standardization of taxation, the abolitionof guilds

—

could not be put back in the bottle."20Although

elsewhere,most

notably in Hanover, therewas

much

more

of a return to thestatus quo, these examples highlight a plausible

mechanism

via which the reformsmay

havehad

enduring effects, even inplaceswhere

the dejure aspects ofFrench reformswere repealedafter 1815.

3

Data

In this section,

we

briefly describe the four types ofdatawe

use for our empirical analysis. Inall cases, further details are contained in the

Data

Appendix.3.1

Country

and

Polity

Level

Outcome

Variables

We

use twomain

data series tomeasure

economic prosperity across countriesand

polities.21Our

first measure ofprosperity is the urbanization rate of a country or a polity,measured

as20

Notethat thesouthernstatesmentionedhere

—

Baden, Wiirttemberg, andBavaria—

arenotinourtreatment group ofinvaded countries. To the extent that defensive modernization promoted economic growth, this willbiasour result downwards, aswediscuss later. 21

Our units ofobservation are countries in their present-day borders where applicable, i.e., where political entities during the 19th century are roughly corresponding to today's borders. For the cases of Italy and

Germany, two complicating factors occur; on the one hand, different regions of these countries experience

different types ofFrench 'treatment.'

On

theother hand,Italy and Germany areestablished as unitarystatesonly towards the end ofthe 19th century. Therefore, we consider 8 distinct pre-unitary polities in Germany, and 12 suchpolities in Italy. Formoredetails,refer to appendices 6 and 6.

the percent ofthe population living in cities with

more

than 5,000 inhabitants.We

compute

urbanization rates for 41 polities (21 present-daystates, 8

German

and

12 Italian pre-unitarystates). Bairoch (1988, Chapter1) and de Vries (1984, p. 164) argue that only areas with high agricultural productivity and a developed transportation network could support large

urban

populations. Inaddition, Acemoglu, Johnson

and

Robinson (2002) present evidence thatboth

in the time-series and the cross-section there is a close association between urbanization

and

income per capita before as well as after industrialization.

We

take urbanization as the bestavailableproxy for

GDP

per capita. Urbanization estimates from Bairoch (1988) and the city level population data from Bairoch,Batou and

Chevre (1988) are fairly reliable and buildon

the

work

ofmany

economic historians.22 In addition, urbanization at this stage ofEuropean

development is likely highly correlated with the growth of industrial activity based in cities.

We

also use estimates ofGDP

per capitafor national polities fromMaddison

(2003).The

numbers

before 1820 are inmany

cases educated guesses by Maddison. Furthermore, becausethese estimates are constructed for

modern

polities, such asGermany

or Italy, they do notallow us to exploit the considerable variation within

Germany

andItaly. Maddison'sestimatesstart in 1500, and are available for 1600, 1700, 1820, and then

more

frequently.We

use theresults with the

GDP

per capita estimates as acheck on our urbanization rateresults.For

Germany,

we

alsocollected datafrom the 19th centuryoftheextentofrailway networksand

also the distribution of the population across different sectors of theeconomy

(industry,commerce

and agriculture).The

sources for all these variables are listed inAppendix

6.3.2

Coding

French

Treatment

We

focusonthreerelatedmeasuresofFrenchtreatment; thesearesummarized

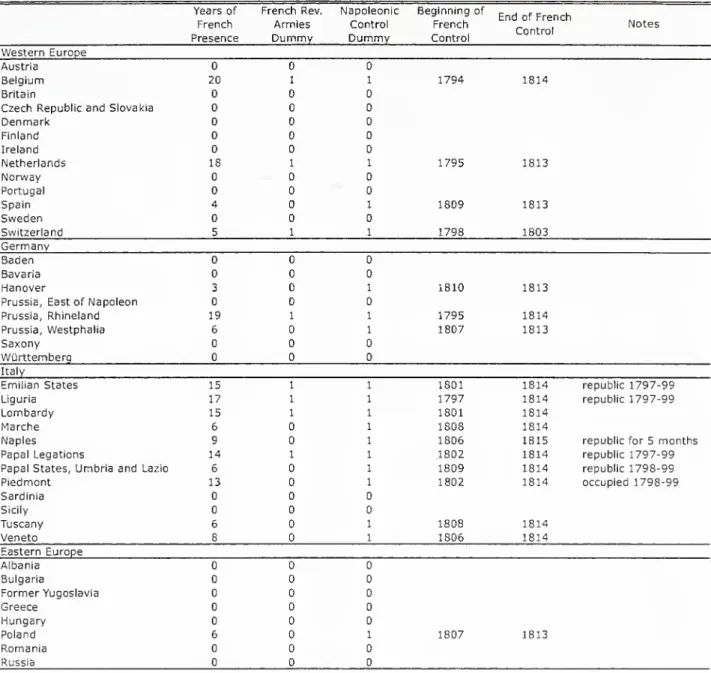

inTable 1for allstatesinourdatasets.

The

first recordsforeachcountry the yearsofFrenchoccupationbetweenthe entire period 1792 and 1815.

We

consider years in which the French had direct controlover these territories or installed republics and principalities directly dependent on French directives;

we

exclude years andmonths

ofpure military occupation, such as for example inthe case of Prussia.

Our

second measure is binary and reports as treated the areas invadedby

the French22

Thecompletecitylevelpopulationdataset hasinformationonall 2,200Europeancitieswhichhad,atsome

time between800and 1800, 5,000ormoreinhabitants. Citylevelpopulations areaddedupanddividedbytotal

population, asgarneredfromMcEvedyand Jones(1978), Lahmeyer(n.d.) orMaddison (2003). TheBairoch et

al. dataset stops in 1850; therefore, weresort toofficialstatisticsofthat period toestimate urbanization rates afterthat date. Moredetails ontheconstruction ofurbanization figures areprovided in Appendix6.

revolutionary armies, thus the Netherlands,Belgium, Switzerland,

most

ofnorthernand

centralItaly as well as the Rhineland.

The

third measure includes countries occupiedby

Napoleon. This adds Spain, Poland,most

of Italyand

thenorthwestofGermany.

The

untreated countriesare all those in

Europe

which were not occupied and for whichwe

have data. This includesBritain, Portugal, Austria, Scandinavia, EasternEurope, andthesouthernandeastern

German

states Baden, Wiirttemberg, Bavaria, Saxony, and Prussia.

To

the extent thatsome

oftheseimplemented

modernizingreforms under pressurefromFrance, through the implicit or explicitthreatof invasion, this coding works against our hypothesis

and

biases ourresultsdownwards.

3.3

Coding

Institutional

Reforms

inGermany

In the last partofour analysis,

we

also use an index ofreforms inGermany,

both toshow

theimpact of the French occupation on institutional reforms

and

as the right-hand side variablein our instrumental-variables strategy. For our 8 polities in

Germany we

were also able to use historical sources to code the nature ofsome

ofthe reforms that took place.The

reformswe

focus on are the enactment of written legal codes including the French civil code, therestructuring of agricultural relations, the abolition of guilds, and the emancipation ofJews.

We

interpret these reforms as a proxy or index for the overall set of institutional reforms,which also include changes in the nature of state administration or tax collection

and

thesecularization ofchurch lands.

We

are not abletoconstruct measures ofthese reforms that arecomparable across different areas of

Germany

(for example, the secularization ofchurch landswas

only relevant for Catholicterritories). Table2 shows the incidence ofreforms inGermany.

Looking firstatthetoppanelofTable2, thefirstthree columnsreport,thetreatment status

forthe 8

German

polities foreachofthe threedefinitionsoftreatment.Column

1, forexample,shows that only

what was

tobecome

the PrussianRhine

Province (the Rhineland)was

treatedduring theRevolutionaryperiod. In

column

2, the Napoleonic treatmentalsoincludesHanover

and Westphalia (the latter also

became

part of Prussia after 1815). Incolumn

3we

record the years of French control, which ranges for 19 years for the Rhineland to just 3 years for Hanover.The

next fourcolumnsrecord the date atwhich the different politiesintroduced the various reformson

whichwe

focus.Appendix

6 describes in detailhow

we

coded these reform datesand

the sourceswe

used.The

first is the date at which a written legal codewas

introduced.of commercial law, represented either by the French code de commerce, or by the Prussian Allgemeines Landrecht (ALR).23

The

Napoleonic civil codewas

introduced in 1805 in French-occupied Rhinelandand in 1808 inWestphalia. Otherplacessuch asBavaria did nothave sucha code until 1900.

Note

that althoughBaden was

never treated it introduced a versionoftheFrench civil code in 1810.

The

nextcolumn

examines agrarian reform, effectively abolition ofserfdomor alternativefeudallandholding arrangements, suchasthe Grundherrschaft, prevalent

in south and west

Germany

(though inmany

cases peasants had to pay a compensation to their landlords). These reformsseem

to have been relatively ineffective during the Napoleonicperiod itself even in the treated areas with the exception ofthe Rhineland.

Column

6 ofthetable records

when

guilds were abolished.As

thiscolumn

reports, the abolition of guildswas

one of the reforms

most

assiduously implemented by the French, but something that onlyhappened

elsewhere inGermany

some

50 years later. Finally,column

7 presents data on theemancipation of the Jews.

Though

some

historians have argued for the importance of this(Ferguson, 1998), the evidence does not suggest that these reformswere actually enacted very

effectively. In

most

German

states, full formal emancipationhad

to wait until the second half ofthe 19th century to be implemented.In

column

8we

construct a simple index of reforms at two exemplary dates, 1850and

1900 for each polity

by

simply adding thenumber

of years each particular reform had been in place and dividing by 4.As

an example, consider Hanover, whichwas

taken overby

theFrench for such a briefperiod that reforms were not implemented.

By

1850 therehad

yet to be a written civil code; agrarian reform had been in place for 19 years; guildshad

not been abolished; and Jews had not been emancipated. Therefore the value ofthe index forHanover

in 1850 is 19/4=4.75. This indexshows a clear distinction betweenparts ofwestern

Germany

that were reformed

by

the French, those places which defensively modernized, like Prussia or Baden, and the rest of Germany. In 1850, for instance, the reform indexwas

33.5 for theRhineland and 27.25 for Westphalia.

The

fact that it was 31.25 for Prussiaand

26.25 forBaden

showshow

important theIV

strategy is to avoid our results being biased by defensivemodernization. Figure 1 plots the reform index over time showing the divergence between

treated areas (Rhineland, Westphalia), defensive modernization areas (Prussia, Baden) and

the rest of

Germany.

The bottom

panel of Table 2 reportssome

of the data in an intuitive form.We

show

23

TheFrench implementedthecivilcodeandthecommercial codesimultaneouslyandthe

ALR

includesboth typesofcodes, soweemphasized the timingoftheintroduction ofboth typesof legalcodes.the average date that different reforms were implemented, by treatment status. For instance, looking at the average date

when

guilds were abolished for polities which got the Napoleonictreatment,

we

see fromcolumn

6 that thiswas

1826,compared

to 1853 for the control group.The

lastrow

ofthetablereports the correlationcoefficient betweenthe years ofFrenchcontroland the date

when

particularreforms wereimplemented. Forexample, incolumn

4we

see that the correlation between the date of introduction of a written civil codeand

years of Frenchpresence is -0.398, so there is a sizable negative correlation

—

more

years of French presenceis correlated with an earlier introduction ofa civil code.

As

will be clear from the table, thecorrelation with respect to the abolition of guilds is the largest.

3.4

Other

Data

We

also use a variety ofother data as controls, in particular the proportion ofthe population ofa politywho

are Protestant, the latitude ofthe capital city ofthe polity, and initial valuesofthe dependent variable.

3.5

Descriptive

StatisticsTable

3A

recordssome

basic descriptive statistics ofthe complete cross-national dataset withthe standard deviations inparentheses below the means. Panel

A

focuses on the urbanizationdataset, whilepanel

B

examines the countries in the dataset withGDP

per-capita.The

table consists of five columns.The

first five rows describe urbanization rates in thefive time periods considered; this evolution is also depicted in Figures 2

A

and

2B.One

seesthat the urbanization rate prior to the revolutionary period

was

larger in polities that were invadedby

the Revolutionary armiescompared

to those that were not.The

same

is true withrespect to the Napoleonic treatment. This suggests that invaded countries were richer in 1700

and

also 1800. Nevertheless, until 1800-1850 the urbanization rates of the two groups do not display different evolutions (if anything, there is a slight convergence ofthe untreated group towardthe treated group). So thereseems tobe littleevidenceofdifferentialtrends before theFrench Revolution. After 1850, there is a

marked

take-off of the treated states relative to therest.

The

next three rows ofthe table reportsummary

statistics for the treatments status vari-ables. Countries not invaded by French RevolutionaryArmies

still have 2.03 years ofFrenchpresence

on

average (column 3),since they were later under Napoleoniccontrol.The

nextrow

groups.

The

final row of this panel records the averages ofour 'Protestant' variable,which

shows that untreated polities are in general

more

likelyto be Protestant.Panel

B

of Table 3A

showssome

similar patterns.The

sample is smallernow

(sincewe

do not have income variations withinGermany

or Italy) butwe

see that in 1700 income per-capitawas higher intreated thanin untreated areas and remained sothroughout the period ofanalysis.

The

picture with respect to latitude and Protestantism is also qualitatively similar.In Table

3B

we

turn to descriptive statisticsfor the 8German

polities. In contrast to thewhole sample

we

can see that, at least for theNapoleonic treatment, there islittle difference between the urbanization levels of treatment and control groups prior to 1789. This is alsoshown

in Figures3A

and

3B. Indeed, in 1750 urbanization is slightly greater in the controlgroup. Subsequently, however, urbanizationgrows

more

rapidly inthetreatment groupso thatby

1900 it is a full 10 percentage points higher in areas occupied by Napoleon.4

Cross-Country

Regression

Evidence

In this section

we

use ordinaryleast squares (OLS) regressions to investigate the cross-countryreduced-form relationshipbetweenour three measures oftreatment

and

the twobasicoutcome

variables, urbanization rates and log

GDP

per capita. In all caseswe

have a panel dataset.For

GDP

percapita, thetime periodsare unevenlyspread (e.g., from Maddison, 2003,we

have income per capita for 1600, 1700, 1820, 1850, 1870, 1890 and 1900). For urbanizationwe

have data for the periods 1700, 1750, 1800, 1850 and 1900.25Our

basic reduced-form regressionmodel

is as follows:yjt

=

dt+

53+

Y^ ctfDfIj+

]T

OfDfljfXjt'T

+

ejt, (1)teTvre teTp°st

where yJt is the

outcome

variable (urbanization or logGDP

per capita) in country j at timet, the df's denote a full set oftime effects, the Sj's denote a full set of country (polity) fixed effects, Xjt is a vector of other covariates, which will be included in

some

of the robustnesschecks, and £jt is a disturbance term.

The

key variable of interest for us is the treatment variable Ij, which is either adummy

denoting polities treated by the French Revolutionary armies/by Napoleon or thenumber

ofyears ofFrench occupation.The

coefficients of interest24

Recall that for Germany the Revolutionary treatment affects only the Rhineland, which iswhy there are no standarddeviations.

2o

The urbanization dataset is balanced except for Hanover and Bavaria in 1700, and the