C ONVERGING INTENTIONS, DIVERGING REALITIES:

Rights vs. Growth-Based Approaches to Safe Sanitation Provision in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

by

Fitsum Anley Gelaye

BA in Architectural Studies Mount Holyoke College South Hadley, MA (2015)

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master in City Planning

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

June 2018

2018 Fitsum Anley Gelaye. All Rights Reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter

/ 1created.

Author

Signature redacted

Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 24, 2018

Certified by

Signature redacted

Assistant Prodior od lnternati, lDjopment and Urban Planning, Gabriella Carolini Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor

Accepted b)<

Signature redacted

Professor of the Practice, Ceasar McDowell Department of Urban Studies and Planning

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE Chair, MCP Committee

OF TECHNOLOGY

JUN 18 2018

C ONVERGING INTENTIONS, DIVERGING REALITIES:

Rights vs. Growth-Based Approaches to Safe Sanitation Provision in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

by

Fitsum Anley Gelaye

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning On May 24, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning

ABSTRACT

Although we are now well into the twenty first century, the possibility of achieving equitable, universal access to water and sanitation is still out of reach for most cities. According to a progress report by the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program, in 2015, 844 million people lacked even the most basic access to safe drinking water (WHO/UNICEF, 2017). The case for sanitation is even more dire, as about 2.3 billion people have no access to the most basic sanitation service (WHO/UNICEF, 2017). Moreover, an estimated 1.5 million children under the age of five die each year as a result of water and sanitation related diseases. This harsh reality is consistently reflected in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where much like many other cities in the global south, water shutoffs are a norm and access to safe sanitation services is unfortunately minimal. Caught between the influences of the normative recognition of water and sanitation as a right and a national development agenda that sees Addis Ababa as the driver for economic progress, the city's utility is struggling to provide adequate access to its inhabitants. This thesis uses the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority's recent, ambitious plan to transition Addis on to the country's first sewage grid as a sight for investigating how these influences play out on the ground and understand how residents are being serviced or excluded from accessing safe sanitation services. Drawing on multiple interviews, close readings of policy documents, and physical analysis of the distribution of services, I conclude that both normative and growth-centric approaches fail to reach their goals of achieving equitable, universal access to safe sanitation services for the city's residents. This is in large part because these approaches are not adequately responding to the realities of Addis Ababa, which is as much a city of informality and poverty as it is the capital of Africa's fastest growing economy.

Thesis Supervisor: Gabriella Carolini

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor and mentor Gabriella Carolini for all she has done to encourage my pursuit of knowledge at MIT. Gabriella's relentless commitment to equity and fairness in planning has inspired me to imagine a theory of practice that I can be proud of. Her ambition and curiosity has also sparked my own, and has been a significant part of my growth over the past two years at DUSP. I would also like to thank my reader, Alka Palrecha for the encouraging comments she has given me during the process of this thesis.

My greatest gratitude goes to my mother, Wesenyelesh Gebeyehu. Thank you Mommy for doing all you can to allow me to peruse my dreams. I have stolen fire now, and will be home soon. My sister, Zeweter Anley Gelaye, I am so glad we are different versions of the same thing. Thank you for being by my side through thick and thin and pushing me to explore the breath of my abilities. Babo, my little boy, thank you for actually taking me seriously. I hope to give you the same opportunities the elders of our family have given me. Babi, I know you are watching this.

Last but not least, I want to thank the graduating class of 2018. It has truly been a pleasure to have learned with, and from, you. To the strangers who have now become close friends, thank you for the support, advise, encouragement and love you have given me. I truly have grown, not only as a professional, but as a person because of you. I wish you all the best.

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

C hapteri: Introductio n ... 7

1 .1 W h y A d d is A b a b a ? ... 8

1 .2 M e t h o d o lo g y .... 9

1.3 Data Collection M ethod, Lim itations and Challenges ... 10

1 .4 C h a p te r B re a k d o w n ... 1 3 Chapter II: Influences On Water And Sanitation Provision in Addis Ababa: ... 14

2.1 The Relevance of using a Rights vs. Growth Based Approaches in Understanding Water and S a n itatio n S e rv ice P ro v isio n Strateg ie s ... 14

2.2 Ethiopia's Acknowledgement of Water and Sanitation as a Right ... 16

2.3 Ethiopia's G row th and Transform ation Plan ... 16

Chapter III: AAW SA and Its Growth And Transform ation Plan ... 18

3.1 Overview of the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority (AAWSA) ... 18

3.2 AAW SA's Revenue Structure and Financial Standing ... 18

3.3 AAWSA's Plan for Growth and Transformation in Service Provision ... 21

3.4 Goal I : Improving the City's Modern Sewerage Grid and AAWSA's Ability to Collect, Remove and R e u s e W a s t e ... 2 2 C h a p te r IV : A n a ly s is ... 2 7 4.1 Addis A baba and the Existing Sew erage G rid ... 27

4.2 The Proposed Expansion of the City Sewerage Grid and Addis' Construction Boom ... 31

4.3 The Proposed Expansion of the City Sewerage Grid and the Integrated Housing Development P r o je c t s ... 3 4 4.4 The Proposed Expansion of the City Sewerage Grid and the City's Informal Community ... 36

4.5 The Proposed Expansion of the City Sewerage Grid and the Burden of Cost Recovery ... 39

4.6 Analysis of AAW SA's Alternative Options for Expanding Access ... 39

4.6.1 AAW SA's Public Rest-stop and Restroom Project... 40

4.3.2 AAW SA's Poorest of the Poor Safety-net Program ... 43

4 .6 4 .7 A n Interventio n Flaw ed by D esign ... 43

C h apte r V : A Few Ste ps Fo rw a rd ... 4 6 5.1 Making the Requirement for Connecting to the Sewerage Network Flexible ... 46

5.2 Form ing Partnerships w ith Com m unity Based Organizations ... 47

5.3 Advocating for the Recognition of the Social Value of Land ... 48

5 .5 C o n c lu s io n ... 5 1

B ib lio g ra p h y ... 5 3

LIST OF FIGURES

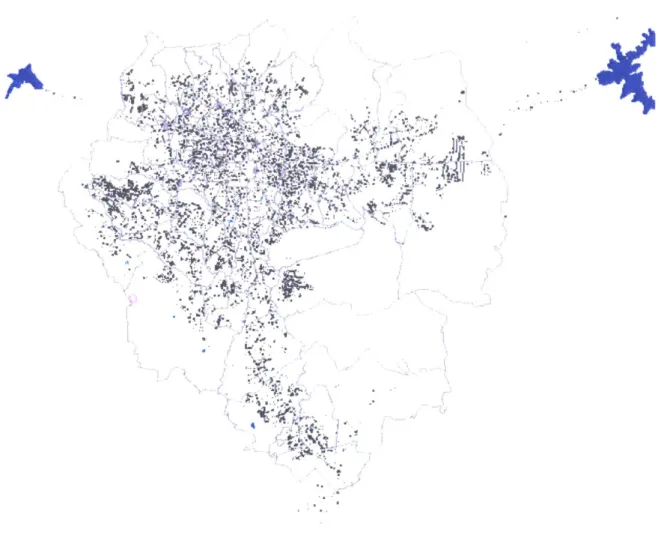

Figure. 1 Location of water m eters run by AAW SA, 2016... 19

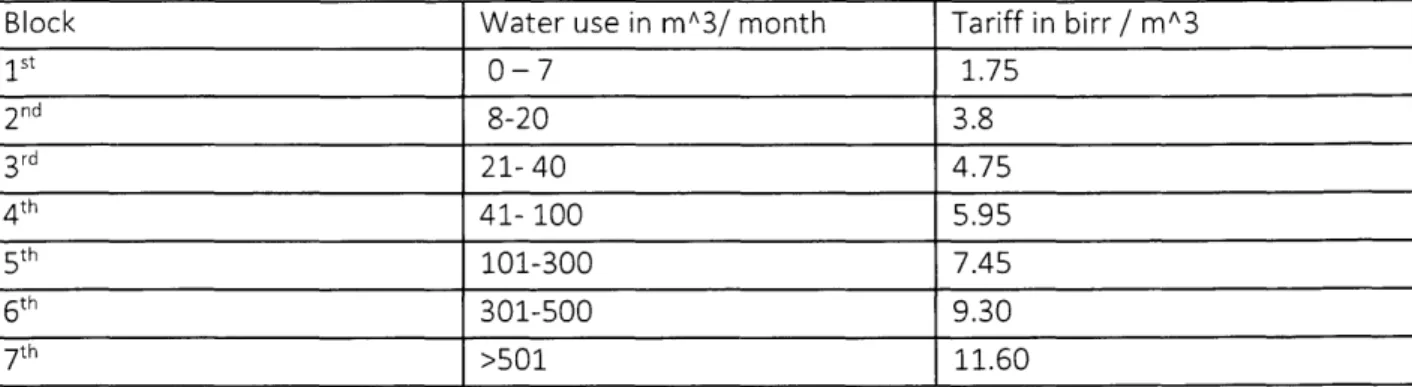

Figure 2. A A W SA 's Tariff Breakdow n ... . 20

Figure 3 AAWSA's Existing and Proposed plan for expanding Addis' Sewerage Network...24

Figure 4. Addis Ababa's Built up area in 1986, 2000, and 2010... 27

Figure 5. Addis Ababa's Existing Sew erage Netw ork... 28

Figure 6. Kebele H ouses in A rada Sub-city... 29

Figure 7. Dot Map of High-rises constructed between 2010-2017 over a gradient map of land expropriation in the four core sub- cities... 32

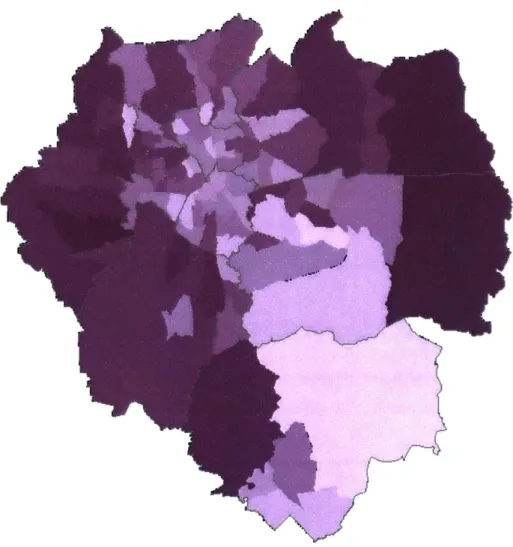

Figure 8. Overlaid image of AAWSA's Proposed Grid with High-Rise buildings constructed b e tw e e n 2 0 1 0 a n d 2 0 1 7 ... 3 3 Figure 9. Location of Integrated Housing and Development Project (Condominium) s it e s ... 3 4 Figure. 10 Overlaid image of AAWSA's Proposed Grid with Integrated Housing Development S it e s ... 3 5 Figure 11. Population distribution of Addis Ababa based on forecasts from the CSA... 37

Figure 12. Residents waiting in line to fill their canteens from a neighborhood public fo u n t a in ... 3 8 Figure 13: AAW SA built public toilet in Kora Neighborhood... 40

CHAPTER

I

INTRODUCTIONAlthough we are now well into the twenty first century, the possibility of achieving equitable, universal access to water and sanitation is still out of reach for most cities. According to a progress report by the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program, in 2015, 844 million people lacked even the most basic access to safe drinking water (WHO/UNICEF, 2017). The case for sanitation is even more dire, as about 2.3 billion people have no access to the most basic sanitation service (WHO/UNICEF, 2017). Moreover, an estimated 1.5 million children under the age of five die each year as a result of water and sanitation related diseases.

This harsh reality is consistently reflected in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where much like many other cities in the global south, water shutoffs are a norm and access to safe sanitation services is unfortunately minimal. Caught between the influences of the normative recognition of water and sanitation as a right and a national development agenda that sees Addis Ababa as the driver for economic progress, the city's utility is struggling to provide adequate access to its inhabitants. This thesis uses the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority's recent, ambitious plan to transition Addis on to the country's first sewage grid as a sight for investigating how these influences play out on the ground and understand how residents are being serviced or excluded from accessing safe sanitation services.

The question for this thesis was partially inspired by an interview I conducted with a high level official and his colleague from the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority (AAWSA) in the summer of 2016 as part of an MIT sponsored research project on the UNHABITAT sponsored Water Operator Partnership program. At the time, the two professionals from AAWSA informed me of the Authority's grand plan to become one of the Africa's top five service providers by 2020 (AAWSA , 2015). When I raised the subject of expanding access to low income communities and informal households, one of my interviewees mentioned that because AAWSA acknowledges water as a right, the authority provides access to untenured communities and those who cannot afford a connection to the city's water line through pay-per-service public fountains. He added, as an informal side note, "you should not be worried about informal communities too much though, they will, after all, be gone in two to three years" (Interview 1, 2016). While one employee's opinions and biases do not necessarily reflect AAWSA's values, this comment still highlights the importance of how priorities in setting the agenda for service provision determine how service provision is implemented on ground.

1.1 WhvAddis Ababa?

Addis Ababa's ability to provide basic services is put under tremendous pressure by a construction boom that requires many resources on the one hand and a rapidly increasing population demanding adequate access to their basic rights on the other. As the construction of commercial high-rises and large single family homes redefines the city's skyline, many are being displaced by the city's urban renewal agenda and its construction boom. Despite receiving varying forms of compensation, it is now common to see households either settling in informal homes or being displaced multiple times over across the city (UNHABITAT, 2017; Yintso,2008). At the same time, the city's population is also growing at a 3.8% rate according to the Ethiopian Central Statistics Agency. Although the CSA estimates the city's population to be about 3.9 million, others like the World Bank estimate it to be around five million (CSA, 2017; World Bank & GFDRR, 2015). The city's population is estimated to double itself to reach close to 10 million by 2037 (World Bank & GFDRR, 2015). As before, the ever continuing urban rural migration is increasing the number of people residing in informally constructed and untenured homes in the city's peripheries (HABITAT, 2017).

It is in this context of rapid construction, development and continued urban-rural migration that the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority struggles to provide basic services to the city's residents. The Authority prides itself on providing universal access to water to the city's residents through water lines and public fountains (Interviewee 1, 2016). Unfortunately, in this case, universal access does equate universal availability of water. Due to water resource constraints exasperated by climatic factors, constant electricity cuts that interfere with water pumps and a 33% rate of non-revenue water, the city's residents connected to the Authority's water lines receive access through shifts (Interviewee 6, 2018 ; AAWSA, 2015). This reality leaves some households without water for weeks. Furthermore, an estimated 37% of the households do not have access to the city's water line, and can only access water through public water fountains. The status of sanitation provision is even worse for the city's residents. According to a 2011 WASH inventory, an estimated 92.34% of the city has some form of access to a toilet facility (Defere, E and Yemaneh, H, 2011). However, 44% of households use unimproved pit latrines and only 20-30% of the city's residents have access to safe wastewater collection and treatment, either through centralized sewerage line or vacuum trucks (Birhane, 2017).

A significant part of Addis Ababa has no access to any services, especially to safe and hygienic sanitation services. These households are usually informal and fail to provide proof of legitimate tenure, live in highly dense settlements that cannot be accessed by AAWSA's vacuum trucks or are too poor to afford connection services. Most residents thus rely on themselves to gain access to these services. Some dig unimproved pit latrines in their homes and empty them illegally and unsafely onto the city streets. Others build pit toilets in empty land they find around their

residences, abandoning them to dig new ones when they fill up ( Interviewee 9, 2017). 70% of the city's residents currently do not have access to safe waste collection services and dump their untreated waste on to the city's streets and nearby streams, leading to the growing pollution of the Akaki River (Van Rooijen, D., & Gebre, G, 2009). Small scale vegetable farms within the city depend on the increasingly polluted Akaki River and groundwater reserves to produce about 60% of the vegetables sold in the city (Van Rooijen, D., & Gebre, G, 2009). As a result of this insufficient provision of hygienic services, Addis Ababa has constantly been affected by the outbreak of waterborne diseases such as Cholera and Acute Watery Diarrhea. In June of 2016, such an outbreak claimed the lives of 12 residents ( as reported, though the number is estimated to be higher) and affected the livelihoods of many across the city.1

Thus, in a city like Addis Ababa that has limited access to services and where informality and poverty are as much a reality as rapid construction and economic growth, the prioritization of objectives when providing basic services has deep implications for marginalized and informal communities. It is given this background that a casual comment by a government official incited an investigation into why Addis is falling behind in sanitation service provision and resulted in this thesis project.

1.2 Methodology

In this thesis, I do a comparative analysis between what I interpret to be an efficiency centric approach taken by AAWSA to increase access to sanitation services and the normative approaches the authority is taking to ensure equitable and universal access to residents. I use the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority's ambitious plan to put 76% of the city on the country's only sewerage grid system and expand the city's wastewater treatment capacity as my main site of investigation. I do this because the investment in this infrastructure is one of the manifestations of the country's aim for efficiently increasing universal access to basic services. Additionally, in my research I have found this sewerage grid to be seen as a symbol of modernity and a platform for fulfilling the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority's ambition for becoming one of the top five service providers in Africa, the Addis Ababa City Administration's aspiration of being a contender with other middle-income cities on the African continent and the Ethiopia's overall goal for eradicating poverty ( Interviewee 1, 2016; AAWSA, 2015 ; National Planning Commission, 2016). Moreover, the expansion of the grid and the city's ability to safely treat wastewater is also an environmental protection strategy and aims to mitigate the pollution of the city's rivers in line with achieving resident's constitutional right to live in a healthy environment (AAWSA, 2015). Lastly, as this infrastructure project is financed by a large loan from the World Bank, it is also

working under a set of conditionalities such as cost recovery and equitable distribution, which in turn has an effect other forms of providing access to sanitation that AAWSA is engaging in.

Although this grid is a focal point for the analysis of this thesis, my investigation will also look into what I categorize as AAWSA'S normative intervention for increasing access to safe sanitation. This interventions is the Authority' plan to expand access to affordable communal and public toilet facilities across the city. Finally, this thesis will also rope in AAWSA's approach to increasing the provision of water to residents who cannot access the city's water lines due to tenure or affordability restrictions, as the sewerage grids by nature unequivocally dependent on having secure access to water.

I use a rights vs. growth based framework to conduct this analysis because I have found there to be a dichotomous relationship between the two approaches in the city's water and sanitation provision strategies. For instance, according to a World Bank document that details the conditions of the loan AAWSA is taking on to finance the expansion of the sewerage grid, public toilet projects are depicted as interventions aimed at ensuring equitable access to the residents of the city that will not be able served by the grid ( World Bank, 2017). These influences are also byproducts of Ethiopia's recognition of water and sanitation as a right both constitutionally and in the international arena on the one hand, and the country's ambitious Growth and Transformation Plan, which has set the goal for reaching middle-income status by 2025 partially through trough efficient infrastructural expansion (National Planning Commission, 2016). As I will explain in the first chapter of this thesis, both these frameworks aim to achieve universal access to water and sanitation for the citizens of Ethiopia and influence the strategies for provision of these services at a local level, including in Addis Ababa.

1.3 Data Collection Method, Limitations and Challenges

The research for this thesis began in the Summer of 2016 as part of a project with Professor Gabriella Carolini from MIT's Department of Urban Studies and Planning. The project focused around understanding the impact of UNHABITAT's Water Operator Partnerships (WOP) and the impact they are having on improving access to basic services in developing cities such as Addis Ababa. At the time, I was tasked with interviewing officials from the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority about the status of provision in the city, the inner workings of the department, challenges and opportunities they have identified and lastly, how the WOP that they were a part of was influencing their ability to increase service provision.

This first set of interviews I conducted, which also includes the one mentioned in the beginning of this chapter, were an introduction to the difficult experiences I had over the last couple of years in my attempts to gather enough information about Addis Ababa's sanitation ecosystem. The first,

and most defining, part of this experience was my initial attempt to contact a high level official who was listed as the person of contact for AAWSA on the UNHabitat Global Water Operator Partnerships Alliance (GWOPA) website. Because AAWSA did not have a live website at the time, this was the only contact I was able to acquire. I thus emailed the official multiple times, but did not receive any answers from him. Thus, armed with an introduction letter that Professor Carolini had written for me, I went to AAWSA's Head Office to find him and conduct my interview. I went from office to office asking for him, but no one seemed to know who he is, or want to give me more information about where I can find him. I later found out from someone who works as a cashier in the finance department that this official had unfortunately passed away a couple of years back and was now replaced by someone new. I found the fact that this information was not updated on the GWOPA website interesting, especially since the official I was seeking out was the Authority's General Manager and an important point of contact. This was not the only hindrance that I faced during that summer. Although I began seeking interviews in the beginning of June, I was not able to conduct any interviews until the beginning of August, three days before I was supposed to leave Addis Ababa. Between June and August, I was traveling between the Head office and the Project Office of the Addis Ababa Water and Sewage Authority, chasing after contacts who were no longer available, making appointments to make other appointments, and mostly waiting outside offices to get a piece of information.

This level of misinformation and delays continued throughout the two other visits I made to Addis Ababa in the Summer of 2017 and January 2018 to gather further data and information for this thesis. It had thus been a challenging task for me to put together the puzzle of the interventions AAWSA has been making to fulfil its mandate of providing adequate services to the city's residents. One reason for the challenges I faced is the fact that it is only in the last couple of months that AAWSA's official website has actually gone live. During the time that I was conducting my fieldwork, there has been little publically available data on even the most common information about water and sanitation services in the city. A second reason is the reluctance that the more accessible, lower-level officials had to provide information to people they did not know or trust without the approval of a high level official. I anticipate that this reluctance stems from the lack of official processes for providing information and responding to data requests from outside entities, which is not just limited to AAWSA. Although some of the people that I was able to interview felt the need to be more transparent with information, especially for those pursuing academic research, data requests in most of Addis Ababa's municipal offices are still viewed as suspicious, and need to be directed by someone who is willing to take the risk of potential downfalls that may come from sharing information. On the other hand, high level officials are usually not available, even for signing a memo that grants permission for lower-level officials to give out interviews and data, making the whole process a long and drawn out on. There is also misinformation within the Authority, which I have encountered when I had been directed to getting information from officials

who did not have access to the data I needed or knew of the projects that I was investigating, prompting me to start my request process again.

Another issue that I have faced while trying to conduct my fieldwork was the quality of the information I was receiving from the Authority, which is influenced partially by the fact that I was conducting this research while being based thousands of miles away from the city. For instance, there have been times when the officials I interviewed gave me little time, limiting the amount of follow up questions that I was able to ask. Some told me to return for more details, but were usually too busy to respond again to my requests. There have thus been times when I had to leave the country with more questions than I had coming in. Another influence on the quality of the data that I gathered was the fact that some officials were not aware of the details of the information they were giving me, which has caused some misinformation in my initial analysis. For instance, in a conversation with an official from the Authority's water control division, I was informed of a significant tariff increase that had been instituted for insuring cost recovery of the aforementioned infrastructural project. However, when I called one of AAWSA's customer service line to re-confirm this information, I was informed that such an increase was not instituted. There was also an instance when an official who provided the map of the existing and proposed sewage lines that makes up a crux of this thesis' analysis was not able to provide me with an adequate explanation of the details of the data he was giving me. Finally, there is also the issue with data unavailability, which has limited the level of analysis I would have been able to undertake during this project. For instance, the analysis of this thesis would have benefited greatly from being able to use geocoded information of public water fountains, which would have been a perfect proxy for spatially representing the city's informal communities. It would also have been extremely helpful to have received the feasibility studies conducted before the decision was made to go forth with the sewerage grid expansion project, which would have added to my understanding of the initial intensions AAWSA had when undertaking this infrastructure project.

All in all, the information presented in this thesis is collected through six semi-structured interviews conducted with officials from AAWSA, one interview with an official from the Addis Ababa City Administration, two heads of households from the city's Kore neighborhood, and two managers of AAWSA's public toilet facilities. I also use spatial data that I gained from AAWSA and satellite imagery in conjecture with multiple reports released on the water and sanitation provision status of the city. Additionally, I use a close reading of the country's constitution, Ethiopia's two Growth and Transformation Plans, World Bank loan documents and AAWSA's annual reports as my sources.

1.4 Chapter Breakdown

The second chapter of this thesis begins by describing why it is relevant to use a rights vs. growth framework in assessing the effectiveness of service provision and describes in detail Ethiopia's economic development policies and the country's recognition of water and sanitation as a right. This chapter will also explain how the country's obligations and policies influence water and sanitation provision strategies in Addis Ababa. The third chapter will describe the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority's mandate, financial standing and internal structure. It will also detail the strategies that AWWSA has devised to increase access to sanitation services for the city's residents. The fourth chapter will analyze how the implementation of the aforementioned strategies plays out on ground to expand and/or limit access to safe sanitation services. I will conduct this analysis through two methods. The first type of analysis will place both the sewerage grid in the physical, economic and demographic context of Addis Ababa, to give perspective on how these plans include or exclude residents from increased access. This method will also analyze how AAWSAs requirements for accessing the sewerage grid in particular contribute to deciding who gains access. Secondly, I will assess the shared facility provision that AAWSA is using as a way to reach residents who might not be able to access the grid, to see how effective they are in expanding safe sanitation service. The fifth chapter will be a reflection on the findings from the third chapter and will provide recommendations for a way forward that centers equity in the city's water and sanitation provision. In this chapter, I will reflect on how the prioritization urban centers like Addis Ababa as the country's engine of economic development actually forces citizens to be further isolated from their recognized right to basic services and fall further into marginality.

C HAPTE

R II

INFLUENCES ON WATER AND SANITATION PROVISION IN ADDIS ABABA

2.1 The Relevance of using a Rights vs. Growth Based Approaches in Understanding Water and Sanitation Service Provision Strategies

The human right to both safe drinking water and sanitation was explicitly recognized in 2010 by the United Nations' General Assembly and the Human Rights Council (G.A. Res. 64/292, U.N. Doc. A/RES/64/292 (Aug. 3, 2010); Human Rights Council Res. 15/9, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/RES/15/9 (Oct. 6, 2010). The resolution rested on the recognition that achieving universal access to water and sanitation were integral to the fulfilling all human rights and maintaining people's dignity. This official recognition was also seen as a vehicle for putting pressure on governments to translate the rights into specific national and international obligations that equitably and adequately addressed the pressing needs for better access to water and sanitation (Gleick, 1999). Additionally, the resolution was a validation of decades of fights by communities across the globe for equitable and just access, and it enabled them to bring attention to perceived inequalities and injustices that

kept them from these services (Murthy, 2013).

Before the 2010 resolution, the need for rights-based approaches to equitable provision of water and sanitation services had been alluded to in many international covenants and declarations that have supported the right to a dignified and humane life. 2 Throughout the

decades of discussion over these two rights, the recognition of water as an economic good with economic values was also pushed, creating an efficiency-centric discourse along with the equity-centric one. This recognition was specifically cemented at International Conference of Water and Environment in 1992 through the Dublin Principles, whose fourth key point stated that "water has an economic value in all its competing uses and should be recognized as an economic good" (The Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development, 1992.) Linking the lack of recognition of water as a right to past wasteful and environmentally degrading uses, the fourth principle called for the need to manage water as an economic good to achieve both efficient and equitable distribution. In other words, the principle suggested that if people were priced correctly, then water would be used more sustainably (Murthy, 2013).

This controversial principle, in conjecture with neoliberal policies advocated for by multilaterals such as the World Bank and IMF, subsequently added to the prominence of service provision strategies that encouraged economic and environmental efficiency as much as they

2 the Convection of the Rights of the Child, the Declaration on the Right to Development, International Covenant

sought equity (Murthy, 2013; Marson & Savin, 2015). Thus, as urbanization, population increase, industrial development and environmental degradation began to put stress on water resources, utilities across the globe began to feel the need to improve the economic pricing of water as a way to minimize wastage and maintain their financial sustainability (Murthy, 2013). In the decade before the international recognition of a normative approach, privatization, cost control and cost recovery in water and sanitation infrastructure development began to be centric to achieving this desired efficiency ( Marson & Savin, 2015).

This approach was heavily criticized as neglecting social benchmarks and decreasing access for those who cannot afford to pay for the full cost of the service rendered to them, especially in the developing world. For instance, Banerjee and Morella (2011) found that tariffs set when capital cost recovery were set as a priority were not affordable for 60% of Sub Saharan Africa households. Furthermore, following a review of World Bank evaluations on neoliberal approach to water provision, Bayliss (2011) finds that there is little incentive for African water operators to pursue social objectives when their performance is measured in financial terms. 3 Additionally, while

assessing whether financial results are actually associated with increasing coverage in twenty five Sub-Saharan countries, Marson and Savin (2015) found that although financial results translate into corresponding coverage increases up to some level, beyond a certain threshold this trend changes to the contrary one, where better financial results are associated with lower increase in coverage or even loss of coverage".

Thus, the 2010 resolution came at a time where the need for efficiency and cost recovery in service delivery was a dominant approach to water and sanitation advocated for and criticized by many. The eventual recognition of water and sanitation as a right brought light to the possibility of diverging from the global responses to service provision that increasingly prioritized economic efficiency and privatization (Murthy, 2013). Rather than implicitly or explicitly prioritizing efficiency, this normative approach called out for centering equity and equality in service provision and making sure the services are affordable and inclusive, even for those whose economic status prevented them from being profit-generating customers (Murthy, 2013).

As can be seen from the subsequent portions of this chapter, in the case of Ethiopia, and by extension, Addis Ababa, the normative priority of service provision and the need to efficiently to match economic development goals are granted, more or less, equal roles in national legislation. However, the above, brief description of the debates on water and sanitation provision shows us what is a priority consideration when carving out strategies for water and sanitation provision has an important role in determining who gets to access the services, and who gets excluded. Therefore, understanding why and how access is limited also rests on understanding the implicit and explicit intensions behind increasing access.

2.2 Ethiopia's Acknowledaement of Water and Sanitation as a Riaht

Ethiopia abstained from voting during the 2010 deliberation to pass water and sanitation as human rights. The Ethiopian delegation of the time acknowledged water to be a "natural right", but abstained from voting because the recognition that states have the sovereign right to their own natural resources was not explicitly mentioned in Resolution 64/292. 4 Despite not

participating in this monumental vote, the country has acknowledged citizen's rights to water and sanitation in many forms since the current governing entity (EPRDF) came to power in the early 1990's. In fact, EPRDF's 1995 constitution, for the first time in the country's history, explicitly states the rights citizens had to some basic services (Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 1995). Specifically, Article 90 of the Ethiopian constitution states that "to the extent the

country's resources permit, policies shall aim to provide all Ethiopians access to public health and education, clean water, housing, food and social security". The government further cemented the

right to water in 2000 through the Water Resources Management Policy, which states that every Ethiopian citizens should have access to water to satisfy their basic human needs. The policy also states that water should be used for fulfilling social and economic needs, emphasizing that domestic water supply and sanitation should have preference over all other uses.

Additionally, Ethiopia has also declared a normative approach to water and sanitation provision with a statement in 2012 during the Sanitation and Water for All (SWA) High Level Meeting in Washington D.C. The statement specified that in alignment with international conventions that view water and sanitation as a right, Ethiopia has defined and extended its pursuit of a Universal Access Plan II (UAP Il)- which sought to reach 98.5% access to safe water and 100% access to sanitation by 2015 (MoWIE, 2012).

2.3 Ethiopia's Growth and Transformation Plan

At the same time that the country has been explicitly affirming the right to basic services such as water and sanitation, Ethiopia has also set a path to eradicate poverty by maintaining a double digit economic growth rate and transitioning from being an agrarian economy to an industry and manufacturing based one (GTP 11, 2015). Although EPRDF has instituted multiple macroeconomic plans, the Growth and Transformation Plan has been the most intentional and well-resourced for achieving this goal. Inspired by the Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty PASDEP's implementation process5 and the country's Urban Development Policy, which frames urbanization as centric to development, the Ethiopian

4 https://www.un.org/press/en/2010/ga10967.doc.htmL, Accessed, March 2018

government instituted the first, five year Growth and Transformation Plan I (GTP 1) in 2011 (MoFED, 2010). The main vision of the GTP I was to make Ethiopia" a country where democratic rule, good-governance and social justice reigns, upon the involvement and free will of its peoples; and once extricating itself from poverty and becomes a middle-income economy" between 2020 and 2023. With the objective of sustaining broad based, fast and equitable economic growth, the GTP I also aimed to increase access to basic services in alignment with the Millennium Development Goals by expanding and ensuring the quality of infrastructure development. The plan especially stated that due to the significant role of urbanization in accelerating the country's economic and social development, urban infrastructure including water and sanitation will be given a priority (MoFED, 2010).

Following this, the country's Urban Water Supply Universal Access Plan and the Urban Sanitation Universal Access plan were drafted by the Ministry of Water and Energy (now the Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Electricity). These two plans provided urban centers with a pathway towards universal access to water and sanitation, or at the very least to meet target 7c of the MDGs (GTP I, 2010). 6 Although by the time the GTP I came to an end in 2015 Ethiopia achieved the Millennium Development Goal of halving the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water, universal access was not achieved. In terms of sanitation, the percentage of people in urban areas with access to improved latrines had increased to just 27 percent from 20 percent in 1990, much lower than the Sub-Saharan Africa average of 40 percent (Birhane, 2017).

Subsequent to evaluation of the first Growth and Transformation Plan ( GTP I), a second Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP 11) was instituted in 2015. The GTP II aimes to maintain an annual economic growth of 11.2 % per year over a five-year period. In addition to reaffirming the GTP l's attempt for increasing domestic saving and attracting foreign investment, it also reemphasizes the need for increasing infrastructure development (National Planning Commission, 2016). The GTP 11 also re-acknowledges the value that urban centers have in furthering the country's development agenda and specifically prioritizes the expansion of sustainable potable water supply and improving urban sanitation. The GTP 11, whose implementation period extends to 2020, aims to continue the path to universal access that the first GTP began, now in alignment with goal six of Sustainable Development Goals (National Planning Commission, 2016). Utilities in the country's urban centers thus follow the structure set by this plan, in addition to the constitutional right to water and sanitation, to shape their own strategic approach to water and sanitation services. This structure gives the agendas of efficiency and rapid development

propagated by the GTP a significant influence over local basic service delivery strategies.

6

GTP 1, 2010 ; target c of goal 7 aimed to halve, by 2015, the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation.

CHAPTER III

AAWSA AND ITS GROWTH AND TRANSFORMATION PLAN 3.1 Overview of the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority (AAWSA)

Although the first piped water service in Addis Ababa began in 1890, it was not until 1970 that the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority (AAWSA) was founded as an autonomous body for providing water and sewerage services for the city in accordance with proclamation No. 68/1963. The Authority works under the acknowledgment that water and sanitation access are rights that the city's residents have, and takes on the responsibility for fulfilling them (Interviewee 1, 2016). Under the slogan "Water is Life!", AAWSA thus has the mandate to develop, collect, treat, and distribute water and wastewater in Addis Ababa. I AAWSA follows its own iteration of the Growth and Transformation Plan in order to fulfil this obligation (Interviewee 1, 2016). This plan forms its basis upon the aforementioned GTP 1I, AAWSA's business plan, Addis Ababa City Administration's plan for the city and multiple studies the Authority has conducted over the course of the past two decades.

The Authority has two divisions : The AAWSA Head Office and AAWSA Water Supply and Sanitation Project Office. The Head Office overlooks the operation and maintenance of the city's water and sanitation systems through its eight branches. The Head Office is also responsible for connecting new lines and deploying the city's vacuum waste collection trucks (Interviewee 3, 2016). The Project Office, on the other hand, is tasked with developing and constructing expansion projects. It is charged with determining the areas that require service expansion in accordance with the Growth and Transformation Plan and the city's masterplan. The Project Office thus conducts feasibility studies, puts out tenders for identifying consultants, suppliers and contractors and oversees the implementation of expansion projects. (Interviewee 3, 2016).

3. 2 AA WSA's Revenue Structure and Financial Standing

AAWSA's Head Office sustains itself through the revenue it collects from selling water and providing waste collection services to residents, and is by principle meant to be self-sufficient. Despite the presence of some decentralized and illicit providers of access to such services across the city, a majority of service delivery is done through AAWSA. As can be seen from Figure 1, which depicts the water points that AAWSA administers as of 2016, the authority has a significant customer base. In fact, the Authority's water line currently reaches 423,260 households out of the over 600,000 that the city is estimated to have.8

7 https://aawsa.gov.et/?Iang=en Accessed, April, 2018

A..

IJA

161P Pj J? . P.-P i. -';6 4hFigure 1. Location of water meters run by AA WSA, 2016

As can be seen from the Figure 2, AAWSA charges its customers on an incremental basis and pegs fees to the amount of water used (Interviewee 1, 2016). The Authority also collects fees from the liquid waste collection service it provides through its vacuum trucks and from public water fountain users. Furthermore, the Authority gets a 10% cut from the fees collected by small and micro enterprises for public toilet services. Finally, it charges fees for solid waste collection, which it splits with the small and micro enterprises that provide door to door collection services

Block Water use in mA3/ month Tariff in birr / mA3 1s 0-7 1.75 2nd 8-20 3.8 3rd 21-40 4.75 4th 41- 100 5.95 5th 101-300 7.45 6th 301-500 9.30 7th >501 11.60

Figure 2. AAWSA's Tariff Breakdown

* 1$ =33 Birr

Despite the multiple sources of revenue the Authority relies on, AAWSA's Head Office usually falls into budget deficits, limiting the amount of services it is able to provide to residents. According to AAWSA's Financial Support manager, the Head Office usually suffers from budgetary short cuts, forcing it to request supplemental funds from The Addis Ababa Finance and Economy Development Office, which it does not always receive (Interviewee 2, 2016). For instance, in FY 2016/2017 of the 840 million Birr (approximately 30.5 million USD) the Authority planned on collecting as revenue, only 82% or around 690 million was collected . When put in contrast with the 1.324 billion Birr (approximately 480 million USD) that the Authority as a whole budgeted to spend over the fiscal year, this deficit has put a strain on the Authority, forcing it to request additional funds from the city administration and pursue foreign funding through its Project Office (AAWSA, 2017).

The biggest reason for this deficiency, is that AAWSA imports most of its materials; from the treatment chemicals it uses, to the pipes it installs , right down to the water meters that are set up in each customer's house. This is very expensive, and requires foreign currency which is currently available in limited amounts for the Authority (Interviewee 2, 2016). Additionally, the Head Office's fee collection method is highly inefficient. According to a World Bank study, 16% of the meter readings show that connected households to be using less than 1 metric cube per month, which appears very low in comparison to utilities in other countries. Couple this with the unreliable door to door meter reading system AAWSA uses, the Head Office's revenue potential is highly compromised ( World Bank, 2017). The Head Office currently loses 33% of the water it provides to Non-Revenue Water, further decreasing its revenue potential. Furthermore, AAWSA significantly subsidizes this services it provides. For instance, the authority takes on 70% of the

cost of emptying and transporting waste from septic tanks. Its water rates are also quite low and affordable. Unfortunately for the Authority however, the affordability of the services it provides generates little revenue. Because of this, the authority is planning to transition out of operating vacuum trucks in the foreseeable future and aims to regulate private service providers instead(Interviewee 4, 2017).

Unlike the Head Office, the Project Office is allowed to accept outside funds, and has been known to partner with foreign entities such as Vitens International - a Dutch Utility -- and the World Bank (Interviewee 3, 2016). In fact, most of the funds that the Project Office receives are from the World Bank, which has had a significant influence in the office's project delivery through the grants and loans it provides. Aside from the capital projects that the Project Office and World Bank are involved in - which I will get into in more detail in the coming sections of this chapter-the Bank also provides financial support to AAWSA for providing access to water lines for residents identified as the city's poorest of the poor (Interviewee 3, 2016).

3.3. AAWSA's Plan for Growth and Transformation in Service Provision

Between the insufficient revenue it has at its disposal and the conditionalities it has to abide by form its foreign donors, AAWSA works under a significant financial pressure. In spite of this, AAWSA still aims to increase access to the services that it provides. In order to do this, AAWSA has instituted the second round of its very own Five Year Growth and Transformation Plan in recognition of the increased demand for clean water and sanitation services that is caused by the city's rapid urbanization and population growth (AAWSA, 2015). The plan document depicts Addis Ababa as a political, economic and social hub not just for the country but for the African continent as well, and sets the goal to make AAWSA one of the top five service providers on the continent. The mandate of this plan is to take into account the rapid growth the city is undergoing and provide the city's residents with adequate and reliable water and sanitation services. Inspired by the growth of the city both physically and in terms of political prominence, the increase in the city's industrial sector and other infrastructural projects planned by the city, the plan sets out to achieve the following four goals by 2020:

1. To make water provision in the city just and lasting for the city's residents.

2. To improve the city's modern sewerage grid and AAWSA's ability to collect, remove and reuse waste

3. To make revenue collection more efficient and increase AAWSA's financial capacity

4. To improve AAWSA's capacity, eradicate rent seeking and create an efficient, productive and transparent service delivery to implement the strategies putforth by the document

AAWSA's goals to invest resources in curbing rent seeking practices in the Authority and capacity building to make its internal workings more efficient are important and much need interventions for bettering its service delivery capacity. However, this thesis is looking at AAWSA's provision of services and not analyzing its internal structure and workings. Thus, I will not be diving into these goals at this time. Rather, in the next section of this chapter, I will conduct an analysis of AAWSA's second goal. As mentioned in the introduction, because of the linked nature of sewerage grids with water availability, my analysis will also eventually loop back to addressing goal one, which aims to provide just and lasting provision of water for residents.

3.4 Goal II: Improving the City's Modern Sewerage Grid and AAWSA's Ability to Collect, Remove and Reuse Waste

As I have stated in the introduction of this thesis, Addis Ababa residents' access to safe sanitation services is still very limited. As of 2015, only 10 percent of Addis had access to the city's sewerage system, which was mostly constructed during the Italian occupation in the 1930s (Interviewee 5, 2018). Today, the main waste removal service that the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority provides for residents is through its fleet of 104 vacuum trucks it operates and 58 private ones that it regulates (Birhane, 2017). Unfortunately, only 62% of the tracks are actually functional, reducing the available number of trucks to only 101 (World Bank, 2017). For the past decade, AAWSA has substantially subsidized this service and has covered 70% the cost of emptying and transporting waste. Although the total cost for this service is about 450.00 birr (approximately 17 USD), AAWSA charges residential customers 69.00 Birr approximately 2.5 USD and non-residential ones 196.00 Birr (approximately 8.50 USD)(AAWSA, 2015). Most houses with septic tanks have a settled sewerage system, where solid part of waste is settled onsite in an inceptor tank while wastewater is allowed to flow out into rivers. This means that septic tanks do not fill up frequently, making safe sanitation virtually free for some households.

However, despite the affordability of this service, it does not serve all households in the city. This service currently reaches about twenty percent of the city's residents. One reason for this is because the vacuum trucks are quite large and cannot penetrate some of the city's densely packed neighborhoods. These trucks also only have the capacity to serve about 130 households and can transport 11,000 cubic meter of waste per day. Moreover, using sludge drying beds as a waste storage method is not an efficient way of providing the whole of Addis Ababa with safe wastewater collection, given that this practice requires a significant amount of land. The city's sludge drying beds and lagoons are sized to treat about 356,000 mA3 of sludge per year. In contrast, the city produces an estimated 357,004 cubic meter of wastewater every day, making the service inadequate for meeting the city's demand (AAWSA, 2015).

In recognition of its current inability to provide adequate and safe access to sanitation services for most of the city's inhabitants, AAWSA has undertaken many a project to increase its service provision capacity. Of these projects, the most ambitious and costly one seeks to transfer the city's current system from one centered around septic tanks and pit toilets to a modern sewerage grid (Interviewee 1, 2016). According to its Growth and Transformation Plan, AAWSA aims to achieve this goal by increasing connection to wastewater treatment plants from its current 10% to 50% and connecting housing units in the Integrated Housing Development Program to containerized package wastewater treatment plant, which will increase access to treatment by 26%, treating 31,000 cubic meters of wastewater per day (AAWSA, 2015). According to AAWSA's 2015 Growth and Transformation Plan Report, that will collectively put 76% of the city onto one big grid. The project also aims to increase Addis' daily wastewater treatment capability from its current 20,000 cubic meters to 375,932 by the given deadline through the upgrade of the Akaki Wastewater Treatment plant and the construction of two additional treatment plants. The first plant is the Kaliti Wastewater Treatment Plant, which will have the capacity to clean 100,000 cubic meters of wastewater per day, and is estimated to benefit 2 million people (AAWSA, 2015). The second plant is the Easter Wastewater Treatment Plant which will have the capacity to clean 150,000 cubic meters of wastewater (AAWSA, 2015). Both of these plants are currently under construction. The expansion of the existing Akaki Wastewater Treatment Plant into two sub divisions will have the capacity to clean 85,000 mA3 of wastewater per day (AAWSA, 2015). Compared to the city's current estimated production of 357, 004 cubic meters of wastewater per day, these improvements will significantly elevate the Authority's ability to safely treat wastewater (AAWSA, 2015).

Figure 3. AA WSA 's Existing Grid (in Green) and Proposed Plan (in Red) for Expanding Addis' Sewerage Network

AAWSA plans on extending the main lines of the grid to reach within three meters of households in the city (Interviewee 5, 2018). AAWSA's connection policy has two distinct features. Households that are within three meters of the main lines are required to connect the grid and finance the last few meters (AAWSA, 2015). On the other hand, even if households are not within proximity to the secondary lines, they can choose to request connection by going to Authority's Head Office (Birhane, 2017). Along with their request, they must provide documentation that proves the legitimacy of their tenure, a water bill they have recently paid and must be able to pay a the connection fee, which approximately starts at 3,450 birr (150 USD) and increase depending on the household's distance from the main line ( World Bank, 2017) . After paying this fee, customers are expected to pay service charges along with their water bill. However, these charges

---Mm

Existing Grid

will be subsidized by the city's administration and AAWSA's revenue from water earnings (Birhane, 2017). AAWSA estimates that connecting each household will take about three days.9

Anticipating the possibility that this service will not be accessed by all residents, AAWSA also plans to significantly increase the city's public and communal toilet stock. These toilets are aimed to be constructed in densely packed areas and low income neighborhoods, to increase access to safe facilities most of the city. By 2020, AAWSA's GTP has set out the goal to increase its current stock of fixed toilets by 500 and mobile toilets by 2200. In addition to these public toilets, AAWSA also plans on expanding its communal toilet stock by adding 300 more (AAWSA, 2015). The communal toilets are part of AAWSA's Poorest of the Poor Safety Net Program, which, with support from the World Bank, aims to increase access to services for the city's poorest households. The communal toilets are built at the request of households who have proof of legal tenure but are unable to afford building their own toilet facilities. AAWSA aims to connect these toilets, along with the public facilities to the sewer grid (Interviewee 3, 2016).

This plan for improvement is a part of the Second Ethiopia Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Project, and gathers its funding from the World Bank and the country's government through funds granted to Addis Ababa City Administration (World Bank, 2017 ; AAWSA 2015). The Second Ethiopia Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Project is a continuation of the First Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Project (2007 -2017), both of which aimed to efficiently increase access to services in Addis Ababa and 22 other urban towns (World Bank, 2017). The project is part of a memorandum of understanding signed between the Ministry of Water, Energy and Irrigation and the World Bank, and aligns itself with the country's Growth and Transformation Plan I's urban and infrastructural agenda (World Bank MOU, 2017).

The budget for this project is 6.7 billion Birr (approximately 224.6 million USD) (World Bank, 2017). Specifically, $169.6 million of the budget will be supplied through an International Development Association loan from the Bank, while the government of Ethiopia will provide $60 million as a grant to AAWSA. The IDA loan will be channeled to AAWSA channeled through the Water Resources Development Fund (WRDF) in the span of six years. The term of the loans stipulates an interest rate of not more than 3% over 25 years, gives AAWSA a five yeargrace period before payment begins (World Bank, 2017).

The goal AAWSA has set to advance its service provision and increase access through multiple channels is ambitious and is exciting. The sheer scale of the project aims to efficiently increase access to sewerage services for a city that is growing both physically and in terms of its population. AAWSA's recognition of the rights that people have to water and sanitation is also reflected in the plan's strategy to reach low income communities through providing shared facilities. Additionally, the plan will significantly increase the city's ability to treat its wastewater,

which will concurrently decrease the pollution of the city's rivers, contributing to achieving resident's constitutional right to live in a safe and healthy environment. The plan will provide opportunities for employment through construction jobs and small scale co-ops, which will help in decreasing the city's 21.2% unemployment rate (CSA Health and Demographic Survey, 2015). Lastly, the aim to "modernize" sanitation service delivery goes hand in hand with the image of modernity and progress that Addis Ababa seeks to embody. However, despite the many merits that can be assumed about this plan, a further investigation into how the implementation plays out on ground is essential to understand how effective it is in reaching the households of Addis Ababa, whose service, as AAWSA claims it, is the number one priority .

CHAPTER I

V

ANALYSIS4.1 Addis Ababa and the Existing Sewerage Grid

Although Addis Ababa is the capital of one of Africa's most recognizable countries, the city is fairly young. Addis was founded in 1889 by Emperor Minilik and his wife Empress Taytu (Pankhurst, 1961). Under Minilik and Taytu, the city grew organically around three nodes: the Imperial Palace, the Arada Market and the St. George's church and maintained a rural characteristic for a long time (UNHABITAT, 2017). Addis Ababa continued to grow in this manner until 1935, during the rule of Ethiopia's last king, Emperor Haile Selassie, when Italy concurred the country and occupied the capital for five years. During the five year occupation period, the Italians created a masterplan aimed at segregating Europeans from Ethiopians. They occupied the central core of the city and expelled locals out, initiating the slow expansion of the city.

A4 A

et

URBAN EXTENT 1986

A

URBAN EXTENT2000 URBAN EXTENT 2010

Figure 4. Addis Ababa's Built up area in 1986, 2000, and 2010 Source- atlasofurbanexpansion.org Accessed, March, 2018

Today, this original core area covers four of the city's ten sub-cities. As can be seen from Figure 4, this area has been consistently built up over the city's lifespan and is the oldest and most

dense part of the city. It was during the Italian occupation that Addis' first sewerage network was built, specifically to address sanitation needs in the Italian occupiers(Interviewee 4, 2017). The city's original grid was thus concentrated in the core of Addis Ababa and mainly serviced the four core sub cities. As can be seen from the following sewage map, most households in the city's core have historically had enough proximity to the sewer grid, so that they could easily connect to it if they chose to. In fact, of the 10% of the city's households connected to the grid as of 2015, about 3% of the households are located in this area (Birhane, 2017). 10

KOTEBE SLUDGE RYING BEDS

EXISTING KALI PROPOSED E

WWT PLAN WWT PLANT

AKAKI 11 W

AKAKI WWT

Figure 5. Addis Ababa's Existing Sewerage Network as of 2017

10 The rest 7% are connected to households part of the city's Integrated Housing Development Project, also known

informally as Condominium Houses, which I will explain in detail in a following section.

I

The housing units in this area were mostly constructed in the 1940's, after Emperor Haile Selassie took back the city from the Italians and reestablished his imperial rule. During this time, much of the city's housing stock was taken over by feudal lords, who became the majority land owners and provided rentals for migrants and those who could not afford to own homes (UNHABITAT, 2017).This form of hierarchical relation between feudal landlords and renters continued until a Marxist-Leninist military junta named Derg occupied Addis in 1974 and irradiated the imperial system. Derg nationalized most of the wealth owned by feudal lords and made land state property. The new, socialist administration also converted the houses owned by feudal landlords into affordable public housing, and branded them as Kebele Houses. 1 Derg managed these homes under the Addis Ababa Administration of Rental Homes, and charged renters a monthly fee of 100 Birr (approximately 3.05 USD) (UNHABITAT, 2017). As of 2007, 142,095 of these homes, mostly concentrated in the city's core, made up a significant part of the city's housing stock of 628,984 units (CSA, 2007 and Tesfaye, 2007). Although most of these houses still stand today, they are in extremely dilapidated conditions because they were initially built of thatch and mud, leading them to be typecast as undesirable slums (MUDCo, 2015).

Figure 6. Kebele Houses in Arado Sub-city

Image source, The Guardian, 2018

11 A Kebele was the smallest administrative unit in the city during the Derg's and much of the current administration's rule