Thinking about Photography in Comics

Nancy Pedri

Abstract

This article provides a short history of photography and cartooning, with an eye toward elucidating their comingling in comics. Drawing from the work of several theorists and practitioners, it traces a variety of methods in which photography has been used in comics. Emphasis is placed on comics’ flexibility as a narrative form; photography’s impact on narrative practices, especially visual narrative practices; and how the use of photography in comics extends well beyond fulfilling a documentary function.

Résumé

Cet article offre une courte histoire de la photographie et du dessin, faite en vue d’élucider leur croisement dans la bande dessinée. Il s’appuie sur les recherches de plusieurs théoriciens et praticiens et présente une série de techniques ayant conduit à l’utilisation de photos en bande dessinée. On met l’accent sur la flexibilité de la bande dessinée comme forme narrative et sur l’impact de la photographie sur la narration, plus particulièrement visuelle. Enfin, on discute aussi l’utilisation de la photographie en bande dessinée au-delà de sa seule fonction documentaire.

Keywords

Drawings are interpretative even when they are slavish renditions of photographs, which are generally perceived to capture a real moment literally. But there is nothing literal about a drawing. A cartoonist assembles elements deliberately and places them with intent on a page. There is none of the photographer’s luck at snapping a picture at precisely the right moment. A cartoonist ‘snaps’ his drawing at any moment he or she chooses. It is this choosing that makes cartooning an inherently subjective medium.

Joe Sacco. Journalism. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2012. xi-xii.

Comics are a composite art, combining not only verbal and visual elements but also different types of images to tell stories. More than ever, comics artists are incorporating maps, charts, photographs, sketches, photocopies, or paintings into their cartoon storyworlds. To an exceptional degree, the past decade has witnessed a new thrust in creative experimentation and innovation marked by the coming together of photography and cartooning in comics. From the quasi equal mix of photography and cartooning in Le Photographe by Emanuel Guibert, Frédéric Lemercie, and Didier Lefèvre (2001-2003) to the cartoon altered photographs reproduced in Ho Che Anderson’s King: A Comics Biography of Martin Luther King, Jr (2005) and Eddie Campbell’s The Lovely Horrible Stuff (2012), from the drawn photographs in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (2006) or Shaun Tan’s The Arrival (2006) to the recent web photo-comics of Derik Badman (2013), Lynn French (2007), or Seth Kushner (2006), there is ample evidence that photography has found its way into a wide spectrum of comics genres. The variety of methods adopted by artists that incorporate photography into their comics universe, with some artists drawing, others altering, and others faithfully reproducing photographs, prompts the consideration that the use of photography in comics is more than a stylistic trend. Indeed, when considered alongside the popularity of photography in comics, the broad range of visual techniques surrounding its use suggests that photography’s narrative potential attracts comics artists to it. Photography in comics does not fulfill a documentary function, corroborating the facts of the cartoon storyworld; it is not subordinated to the other verbal and visual elements that comprise the comics universe in which it is used. Instead, it joins those elements to advance the narrative and get the business of storytelling done.

The flourishing of comics that make use of photographs should come as no surprise in our post-photographic age where digital photography has all but replaced analog photography. This change in photographic technology, with its quick production of images that are immediately ready for viewing and printing as well as digital processing and publishing, makes it comparatively easy to embed photographs in different verbal or visual media. It thus gives rise to photographic hybrids (Richten 75) where photographs merge with different visual or verbal media to produce unique narrative combinations that entice readers to develop a new literacy better suited to accommodate the “fluid, evanescent digital image” (Richten 76). Comics are only one among many media that have enriched their visual storytelling practices by taking hold of the photographic image. As Diarmuid Costello and Dominic McIver Lopes note, “the boundary between photographic and non-photographic art has blurred, as the camera has found a home in a wide range of art practices from painting and theater through sculptural installation to conceptual art” (1).

Comics do, however, easily accommodate photography and the visual innovations its use gives rise to since comics are a very flexible multimodal storytelling form that “produces numerous codes to create meaning” (Postema, Narrative Structure in Comics xvi).1 Comics impress for their diverse handling of

panels and gutters, word balloons and captions, speed lines and emanata, colour and other signifying features of the form. Comics artists deploy not only different combinations of words and images to tell their stories, but also a remarkable range of different types of images and verbal scripts. There is literally no end to how a comics universe can blend all types of words and images to create a meaningful story; it is an infinitely flexible medium. In comics “[t]here is room for very different styles of art,” writes Paul Gravett. “In fact, graphic does not narrow down to drawing and illustration, as in graphics, since some artists create their comics using photos, 3D models, or found objects” (8).

The comingling of photography and cartooning is not new to the comics form. Indeed, since its inception in the 1880s, photography “offered to cartoonists an almost unlimited source of new models that could be stylized, deformed, or redirected in empirical and intuitive manners to represent action and movement” (Smolderen 120). Almost immediately following the invention of the photographic process and the first experiments in photography that were often available for public viewing, cartoonists were inspired by the way in which photographs could be assembled to represent a world in action. The narrative concern with representing action over time was an important development that took place in the comics world, one greatly inspired by chronophotography -- the use of photographic cameras to record minute details of movement -- and, in particular, Eadweard Muybridge’s late-nineteenth-century animal and human motion studies.2 Muybridge’s chronophotographic plates, which portray the

progressive movement of the photographed subject across a sequence of equally sized frames, inspired comics artists to adopt a repetitive grid to convey motion. A. B. Frost, who drew comics for Harper’s Bazar in the 1880s, was instrumental for crafting the standard comics storytelling practice of drawing a sequence of contiguous images divided (and united) by spatial and temporal intervals. As Thierry Smolderen comments, he “understood that Muybridge’s regular grid, strictly identical framings, and precisely timed intervals gave temporal, dynamic meaning to the gaps between successive images” (123). Other cartoonists that were instrumental for promoting the multipanel, sequential comics include F. M. Howarth and Jimmy Swinnerton in the US, Wilhelm Busch in Germany, and Achille Lemot in France.3

Comics, however, did not merely adopt the discrete image sequencing of chronophotography; it adapted it to meet its own narrative ends as they intersect with its specific narrative means. Unlike Muybridge’s chronophotographic plates that exposed the tiniest of equally timed intervals of motion, comics panel to panel transitions function to impress the action’s development through time by providing readers with a series of “pertinent postures, which Lessing might have called ‘pregnant moments’” (Kukkonen, “Comics as a Case Study” 43). Comics thus evoke movement across time not only by way 1. See Groensteen 6.

2. See, Bukatman 88-89; Braun 247-256; Gunning; and Kukkonen, “Comics as a Test Case for Transmedial Narratology” 41-43. Because of their studies on motion, Muybridge and his contemporary Étienne-Jules Carey are often referred to as principal contributors to the development of the motion picture.

3. A precursor to multi-panel, sequential comics storytelling is Rodolphe Töpffer who produced such strips as early as 1830.

of what is recorded within its panels, but also through omissions or fractures in both space and time that occur between individual panels. Through the sequencing of panel frames, comics strive to achieve not so much the illusion of motion, but rather the illusion of a coherent, continuous, dynamic movement of action across time. Its language of motion, as Scott Bukatman specifies, is characterized by “[a] flowing, more improvisational line, the sense of an illustration as incomplete unless viewed as part of a sequence, and an increasing emphasis on what Scott McCloud categorizes as moment-to-moment (rather than scene-to-scene or action-to-action) transitions between illustrations” (92). With the concern to convey action across time, the panel and the gutter space’s narrative potential was realized and multipanel, sequential graphic narratives were born. These salient visual features that mark the comics’ narrative structure have been a staple in comic strips and books alike since the last decades of the nineteenth century. Hijacked, so to speak, from early photographic practices, but mastered and expanded upon by comics artists, they quickly became popular in Europe and America.4

The fast growing standard layout of comics strips and pages reflected not only a desire to better relate motion across time, but also the new visual culture -- “the shared practices of a group, community, or society, through which meaning is made out of the visual, aural, and textual world of representations” (Sturken and Cartwright 3) -- fostered by the invention of photography. The ubiquity of photographic images, rapidly produced and widely disseminated, resulted in a shift in ways of seeing the world in the culture at large. Photographs “extended our field of vision” and accounted for new and variant details that “created sets of objects embodying the categories that organized the visual world” (Armstrong 15, 21). Once mass produced and consumed, photography began shaping public consciousness.5

Photography “had a significant impact not only on the way reality is perceived, but also on how it is narrated” (Horstkotte and Pedri 9). As a principal determinant of visual culture, photography was a social practice that had a very real influence on visual (and verbal) representation practices and that, in turn, was influenced by those practices.6 On the one hand, photography originated in conventions

of vision based in painting and other handmade images (Snyder 511); on the other, drawing and painting practices borrowed from the photographic style and aligned themselves with the fast growing photographic tradition. Some ways in which photography borrowed from or emulated painting and other pictorial media range from choices in subject matter to the mode of address, from the format or size of the image to the intended venue of presentation. To emphasize the interrelatedness of photography, painting, and other drawing forms is to conceive of photography not as “a discrete medium,” but rather as pertaining to “a pictorial continuum,” as participating in an artistic tradition that extends beyond its medium specific qualities (Costello 80).7

4. Cf. Gardner who argues that film, not photography, gave rise to the comics sequence (Projections 1-28). 5. See J. Ryan for an extended discussion of photography’s moral impact.

6. For studies on the influence photography exerted on literary practices, see Adams; Armstrong; Bryant; Rabb; and Rugg.

7. See also Gombrich; Snyder; and Warburton, who argue for a strong continuity between painting and photography. Critics who approach photography as distinct from painting include André Bazin, Stanley Cavell, and Jonathan Friday.

Notwithstanding this appreciation of photography as equal to other pictorial arts in both aesthetic value and kind, photography’s intimate link to them also gave rise to a new sense of reality and its representation, which then had serious implications for painting.8 “The first and most obvious impact of photography on

painting,” writes Michael North, “was to correct certain habits of composition that turned out to be visual conventions and not accurate transcriptions of reality” (14). Even before the invention of photography, painting had been influenced by proto-photographic techniques through the use of drawing and drafting aids, such as the camera obscura, the camera lucida, the silhouette machine, the magic lantern, and the physionotrace. But, photography was more than a visual aid to painters. It also influenced a painterly and drawing style characterized by the removal of modulations of tone and value producing “flattened, highly contrasted shapes that seemed both artificial and roughly unfinished to early viewers” (ibid.). With the advent of photography, painters and drawers alike began to adopt a style that evoked the flat, stamped-out quality of a photograph or print.9 Photography always existed in a reciprocal relationship

with the other visual arts; indeed, some argue that the photographic image became “the reference by which all graphic representation was instinctively measured” (Smolderen 121). Whether one postulates likeness or resemblance as the aim of graphic representation, that which Ted Cohen disparagingly calls “a kind of gross, generic representation” (299), or whether one appreciates the value of representation in itself, a value that takes into account the artistry of photography and other forms of visual representation, what needs to be emphasized is that the relation between painting and photography has always been a complex mutual one.

Partaking in and drawn by the changes in visual practices and expectations brought about and promoted by photography, comics artists in the 1880s and 1890s began to adopt clear lines and visual narrative structures that gave their stories a flat, pseudo-objective tone. “From the point of view of an illustrator,” explains Smolderen, “the defining characteristic of photographic images was their cold neutrality of tone, which they shared with technical illustration” (129). Producing a much-desired mechanical tone, this new model of drawing associated with cartoonists Caran d’Ache (Emmanuel Poiré), Christophe (Georges Colomb), and Rudolph Dirks replicated the detached, matter-of-factness of the photographic image.

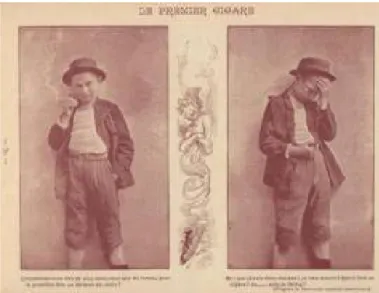

Cartoonists did not hold photography at arm’s length for long as the adaptation of photographic practices to cartooning and comics stylization suggests. As early as 1900, a two panel photo-comic strip entitled “Le premiere cigar” was produced in Album Noël, a collection of ninety-seven comic strips by different artists including Achille Lemot, J. B. Clark, and F. M. Howarth.10 “Le premiere cigar” is a two

photograph comics sequence of a young boy smoking a cigar; the photographs are placed side-by-side, traced with a dark line, separated by a large gutter with an ink drawing of a devil-like figure that emerges from the smoke of a cigar, and accompanied by a verbal text narrating the boy’s experience (Fig. 1).11

8. See De Font-Réaulx for an extended analysis on the relationship between photography and painting. 9. Manet is perhaps the best known painter who adopted this style in his Olympia.

10. See Andy’s Early Comics Archive.

11. This short photo-comic was produced at the same time when photography began replacing drawing in an illustrative capacity in the magazine industry. An early example of this new trend is the 1899 hunter and dog photographic illustrations reproduced in Penny Pictorial Magazine.

Fig. 1: (artist unknown) “Le premiere cigar.” Album Noël 1900.

The attractiveness of the photographic image for comics artists is also evident in another comic strip included in the same Album Noël. In a six-panel comic strip, “Histoire d’un nid: D’une famille aérienne d’après des photographies indiscrètes,” each image of a mother bird interacting with her new hatchlings is traced from actual photographs. The result is detailed, realistic drawings that lack many of cartooning’s popular stylistic features, such as the use of pronounced outlines, motion lines, or cross-hatching. These early examples of the concrete use of photographs by comics artists testify to the magnitude of the impact of photography on existing visual media as well as to the malleability of the comics form.

Comics penchant for experimentation, especially for what concerns its visual storytelling techniques, and its concrete intersection with photography are further exemplified with an early 1950s Mad Magazine comics cover (Fig. 2). The magazine’s eleventh issue mixed “drawing and photography in a completely new way, so that a photograph of roof tops and water towers collaged with a gargoyle monster drawn by Basil Wolverton can be called ‘The Beautiful Girl of the Month’” (Mitchell and Spiegelman 24).

Another early example of the comingling of cartooning and photography are cartoonist Louis Magila’s racy photo cartoon collages published in Humorama (and other magazines of the Humorama group) since its first 1957 issue and into the 1970s (Fig. 3). Whereas the Mad Magazine cover uses a photograph cityscape as a backdrop to a large cartoon monster- female hybrid, Magila’s collage positions cartooning and photography on equal footing. Despite their differences, these mid-century American examples suggest that some cartoonists drove their visual experimentation by drawing from photography and the allure it held for readers.12

Given this long and lively interaction between photography and comics, the current popularity of photography’s inclusion in comics cannot be said to mark a change in the visual technology of comics. It can, however, be said to mark a new visual trend that exposes and challenges our conception of both photography and cartooning.

12. It is not by chance that these early examples of the comingling of photography and cartooning appeared in commercial magazines in the 1950s when new web-offset printing technologies facilitated visual experiment.

Fig. 2: Basil Wolverton. Mad Fig. 3. Louis Magila. Untitled. Jest 1962. Magazine 11 May 1954.

Cartoons and photographs have often been theorised as opposite types of pictures in relation to their level of abstraction or what Scott McCloud calls levels of iconicity, that is, in relation to how closely they resemble their real-life counterparts (29). Unlike the photographic image that is said to have a privileged because necessary, direct “relationship to objective reality,” cartoon images have a “relationship to the subjectivity of the artist: a drawn image implies that someone drew it” (Woo 175). The cartoon image does not hide, or attempt to hide, the hand of its maker as the photographic image does. It draws attention to and, at times, even exploits the fact that what it shows has been “transformed through somebody’s eye and hand” (Wolk 118). Whereas the cartoon image, with its use of symbolic abstraction and distortion, makes apparent its own handcraftiness (Gardner, “Storylines” 56), the photographic image conceals its maker’s hand and thus is readily approached as “an imprint or transfer of the real” (Krauss 26). Given their unique modes of production -- one handmade, the other mechanical -- the two types of images cannot be (or, at least, seem to cannot be) further removed one from the other. They are situated at diametrically opposed sides of what W.J.T. Mitchell deems to be a particular branch of the family of images, graphic images (10), or what Roland Barthes before him calls “the community of images” (3).

Theorists who set out to compare and contrast cartoon and photographic images also emphasize the uniqueness of each image within that family. As Philippe Marion argues, cartoon images are distinct from photographic images insofar as they are “eminently self-reflexive and autoreferential” (qtd. in Baetens 149). Indeed, Marion holds that since cartoons are so obviously handmade, not only do they allude to their own making, but the narrative space the cartoon images occupy is a “highly mediated, unreal” one (ibid.). This is because the hand-crafted quality of the cartoon drawings that comprise the comic universe posits vision as necessarily mediated; they present “the way the artist’s mind interprets sight” (Wolk 125). Others too have argued that “[r]ealism is incompatible with comic art” (Inge 14) or that “there is no truth or realism inherent in the mode (drawing) or style (which is generally

non-realistic)” (Round 325), and some have suggested that because of this comics, especially particular comics genres such as graphic memoir and comics journalism, may “reconfigure the relation between the visual and the truthful” (Cvetkovich 114). Like Marion, these comics critics examine the degree to which the cartoon as a type of image is or is not linked to the real world. They do so by gauging the cartoon image’s and the cartoon universe’s similarity to, resemblance to, or dependence on the real.

Similar criteria govern much thinking informing the photographic image. Theorists who have linked the photograph’s specificity to its dependence on the real world include such familiar names as André Bazin ([1945] 1975), Susan Sontag (1977), Rosalind Krauss (1981), and Barthes (1981), all of whom were instrumental in legitimizing the academic study of photography. More recently, Jonathan Friday has studied the relationship between the photograph’s implicit authority and its indexicality or its immediate contact with the thing in the real world it represents. According to Friday, photography’s unique photochemical process sets photographic images apart from other images; indeed, it impacts “the way in which photographs are made, how they are related to the world they depict and their status as evidence” (44).13 The relatively unquestioned assumption that the photograph shows what has been in

the real world continues to govern its appreciation even if we know “that the ‘objectivity’ of technical images is an illusion” (Flusser 15).

It is relatively common for critics who consider the stylistic particulars of the drawn cartoon image to contrast it to the mechanically produced photographic image. Surprisingly, however, the perceived difference between the two types of images -- the “stylized” quality of cartoons and the “realist” quality of photographs (Beaty n.p.) -- has been highly underexplored by the growing number of scholars working in comics studies or in the field of word-and-image relations. Some comics critics who swiftly distinguish cartoon images from contemporary realist forms such as photography include Amy Kiste Nyberg (117-118), Ann Miller (123), Barbara Postema (“Draw a Thousand Words 488), Douglas Wolk (118), Ann Cvetkovich (114), and Pascal Lefèvre (72). Other exceptions include brief mentions of their comingling by Marianne Hirsch who claims that the documentary photographs in Art Spiegelman’s Maus expose all images as fictional constructs (25); Ann Miller who approaches the use of other media in comics, including photography, as an instance of intertextuality (142); and Elizabeth El Rafaie who sees the inclusion of photographic images in graphic memoir as documentary evidence (158). These critics, however, only nod towards the distinctions between photographic and cartoon images, setting up quick contrasts that are understood to hold true; they do not offer extended critical commentaries on the differences and similarities between the two types of images.

More extensive studies on the use of photography in particular comics include Julia Watson’s analysis of drawn photographs in Fun Home, Roy Cook’s examination of drawings of photographs in comics, and my own studies on the inclusion of actual photographs in Le Photographe (Pedri “When Photographs Aren’t Quite Enough”) or in graphic memoir (Pedri “Cartooning Ex-Posing Photography in Graphic Memoir”). Whereas Cook emphasizes the drawn photograph’s objective purport, I argue that the photographs reproduced in comics have a narrative, story-based (and not a referential, reality-based) function that blurs boundaries separating the documentary and the aesthetic. Watson also underscores the 13. For a detailed overview of how photography has come to be seen as a special type of images, see Dubois (1990).

realistic drawing style of the photographs depicted in Fun Home. However, unlike Cook, she does so to argue that the drawn photographs betray untold stories, offering the protagonist occasion for introspection and, at the same time, inviting the reader’s spectatorial complicity. For Watson, photography in Fun Home raises “questions about the nature of visual evidence and the possibility of viewers’ empathic recognition” (38). Although studies such as these begin to pave the way for a critical discourse that engages with this fast growing storytelling technique, much more work in the field is needed.

The scarce work in the use of photography in comics is particularly surprising given that comics critics tend to privilege the visual storytelling techniques and devices of comics over the verbal.14 The

focus on the visual rests on the shared understanding that, although in comics words and images often come together in an integrated way to tell a story, comics is essentially a visual art form. (If we think of sans paroles or the extended use of wordless pages in comics, it is easy to see that words are not necessary to the comics form.) Interest in the narrative capacities of the visual track of comics has led to numerous studies that focus on page-layout,15 the use of repeated images,16 the graphic line or the

gutter space,17 the angle of vision,18 and other visual devices within specific graphic novels. However,

despite the emphasis placed on visual storytelling among comics scholars and practitioners -- with some claiming that images (and not words) definitively tell the greater part of the story in a comics universe -- the use of photography (or other types of images, for that matter) by comics artists to help tell their stories has not yet received adequate critical attention.

Studying the way in which the mixing of different types of images in comics shapes the telling as well as the story in specific comics or across a number of different comics genres may very well lead to a better understanding of how different types of images can (and often do) come together in comics to orchestrate a unique reading experience, one that draws on preconceived notions of readers, that accentuates the mechanics of visual storytelling, and that privileges subjective interpretation. It can thus lead to links between comics studies and the findings proposed by scholars such as Marie-Laure Ryan and Fiona Doloughan who are working towards a more comprehensive understanding of visual forms of storytelling and how they interact. The investigation of how photography can work alongside another visual mode of representation, as opposed to a verbal one, will also introduce a new angle to the study of photography in literature, which is to date mostly focused on examining the impact of photography on literature in general19 or its use in specific literary genres20 or in particular literary texts.

As editor of this volume, it is my hope that the essays collected here will leave a mark in the field of word-and-image studies by introducing a new subfield of study, photography in comics. Another prospect is that this volume will promote further analysis and scholarly considerations of the mixing of visual modes in comics. Lastly, it is also my hope that it will influence the cultural understanding of 14. See, for instance, Badman (“Talking, Thinking, and Seeing in Pictures” 97); Postema (“Draw a Thousand Words” 487).

15. See, for instance, Smith; Kukkonen, Studying Comics and Graphic Novels (7-30); Cortzen; Szczepaniak; Duncan and Smith (139-141).

16. See, for instance, Fischer and Hatfield (81-91); Horstkotte and Pedri (343-350); Groensteen (147). 17. See, for instance, Drucker (40-44); and Round (317-320).

18. See, for instance, Fischer and Hatfield (78); Morgan (37); Herman (135). 19. See, for instance, Armstrong; and Bryant.

visual storytelling practices, including cartooning and photography, and will encourage artists to explore new creative initiatives by promoting dialogue between comics artists, theorists, and those interested in this evermore popular visual storytelling practice.

Works Cited

Adams, Timothy Dow. Light Writing and Life Writing: Photography in Autobiography. Chapel Hill, London: U of North Carolina P, 2000.

Anderson, Ho Che. King: A Comics Biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2005. Andy’s Early Comics Archive. http://www.konkykru.com/earlycomics.htm. Web.

Armstrong, Nancy. Fiction in the Age of Photography: The Legacy of British Realism. Cambridge and London: Harvard UP, 1999.

Badman, Derik A. MadInkBeard No. 5. Private Publisher: Winter 2013. Web.

---. “Talking, Thinking, and Seeing in Pictures: Narration, Focalization, and Ocularization in Comics Narrative.” International Journal of Comic Art 12.2 (2010): 91-111.

Baetens, Jan. “Revealing Traces: A New Theory of Graphic Enunication.” The Language

of Comics: Word and Image. Ed. Robin Varnum and Christina T. Gibbons. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2001. 145-155.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

Bazin, André. [1945]. “Ontologie de l’image photographique.” Qu’est-ce que le cinema? Paris: Cerf, 1975. 9-17.

Beaty, Bart. “Le photographe Vol. 3, Emmanuel Guibert.” The Comics Reporter. Dec. 14 2006. Web. Bechdel, Alison. Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

Braun, Maria. Picturing Time: The Work of Étienne-Jules Marcey (1830-1904). Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1994.

Bryant, Marsha. Photo-Textualities: Reading Photographs and Literature. Newark: U of Delaware P; London: Associated UP, 1996.

Bukatman, Scott. “Comics and the Critique of Chronophotography, or ‘He Never Knew When It Was Coming!’.” Animation 1 (2006): 83-103.

Campbell, Eddie. The Lovely Horrible Stuff. Portland: Top Shelf Productions, 2012. Cavell, Stanley. The World Viewed. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1979.

Cohen, Ted. “What’s Special about Photography?” Monist 71.2 (April 1, 1988): 292-305.

Cook, Roy. “Drawings of Photographs in Comics.” The Media of Photography. Ed. Diarmuid Costello and Dominic McIver Lopes. Spec. issue of Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 70.1 (Winter 2012): 129-138.

Cortzen, Rikke Platz. “Thirty-Two Floors of Disruption: Time and Space in Alan Moore’s ‘How Things Work Out’.” Crossing Boundaries in Graphic Narrative: Essays on Forms, Series and Genres. Ed. Jake Jakaitis and James F. Wurtz. Jefferson: McFarland, 2012. 93-103. Costello, Diarmuid. “After Medium Specificity chez Fried: Jeff Wall as a Painter; Gerhard

Richter as a Photographer.” Photography Theory. Ed. John Elkins. New York / London: Routledge, 2007. 75-89.

Diarmuid Costello and Dominic McIver Lopes. Spec. issue of Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 70.1 (Winter 2012): 1-8.

Cvetkovich, Ann. “Drawing the Archive in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 36.1-2 (Spring / Summer 2008): 111-128.

Doloughan, Fiona J. Contemporary Narrative: Textual Production, Multimodality and Multiliteracies. London, New York: Continuum, 2011.

Drucker, Johanna. “What Is Graphic about Graphic Novels?” English Language Notes 46.2 (Fall-Winter): 39-55.

Dubois, Philippe. L’Acte photographique. Paris, Nathan, 1990.

Duncan, Randy and Matthew Smith. The Powers of Comics: History, Form and Culture. New York: Continuum, 2009.

El Rafaie, Elisabeth. Autobiographical Comics: Life Writing in Pictures. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2012.

Fischer, Craig and Charles Hatfield. “Teeth, Sticks, and Bricks: Calligraphy, Graphic

Focalization, and Narrative Braiding in Eddie Campbell’s Alec.” SubStance 124 40.1 (2011): 70-93.

Flusser, Vilém. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. London: Reaktion, 2000.

De Font-Réaulx, Dominique. Photography and Painting, 1839-1714. Paris: Flammarion, 2013. French, Lynn. Dark Red. 2007. Web.

Friday, Jonathan. Aesthetics and Photography. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002.

Gardner, Jared. Projections: Comics and the History of Twenty-First-Century Storytelling. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2012.

---. “Storylines.” SubStance 124 40.1 (2011): 53-69.

Gombrich, E. H. The Image and the Eye. Oxford: Phaidon P, 1982.

Gravett, Paul. Graphic Novels: Stories to Change your Life. London: Aurum Press, 2005.

Groensteen, Thierry. The System of Comics. Trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2007.

Guibert, Emanuel, Frédéric Lemercie and Didier Lefèvre. Le Photographe. 3 volumes. Brussels: Aire Libre Depuis, 2001-2003.

Gunning, Tom. “Never Seen this Picture Before: Muybridge in Multiplicity.” Time Stands Still: Muybridge and the Instantaneous Photography Moment. Ed. Philip Prodger. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003. 222-270.

Herman, David. “Beyond Voice and Vision: Cognitive Grammar and Focalization Theory.” Point of View, Perspective, and Focalization: Modeling Mediation in Narrative. Narratologia 17. Ed. Peter Hühn, Wolf Schmid, and Jörg Schönert. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2009. 119-142.

Hirsch, Marianne. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory. Cambridge, London: Harvard UP, 1997.

Horstkotte, Silke and Nancy Pedri. “Introduction: Photographic Interventions.” Photography in Fiction. Ed. Silke Horstkotte and Nancy Pedri. Spec. issue of Poetics Today 29.1 (Spring

2008): 1-29.

Krauss, Rosalind. “The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism.” October 19 (1981): 3-34. Kukkonen, Karin. Studying Comics and Graphic Novels. Malden: Wiley Blackwell, 2013. ---. “Comics as a Test Case for Transmedial Narratology.” SubStance 124 40.1 (2011): 34-52. Kushner, Seth. CulturePOP Act-I-Vate. 2006. Web.

Lefèvre, Pascal. “Mise en scène and Framing: Visual Storytelling in Lone Wolf and Cub.”

Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods. Ed. Matthew J. Smith and Randy Duncan. New York, London: Routledge, 2012. 71-83.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins, 1994. Meskin, Aaron. “Defining Comics.” Journal of Aesthetics 49.3 (2009): 219-239.

Miller, Ann. Reading Bande Dessinée: Critical Approaches to French-language Comic Strips. Bristol: Intellect, 2007.

Mitchell, W.J.T. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1986. Mitchell, W.J.T. and Art Spiegelman. “Public Conversation: What the %$#! Happened to Comics?” Comics and Media. Ed. Hillary Chute and Patrick Jagoda. Special issue of

Critical Inquiry (Spring 2014): 20-35.

Morgan, Harry. “Graphic Shorthand: From Caricature to Narratology in Twentieth-century Bande Dessinée and Comics.” European Comic Art 2.1 (2009): 21-39.

North, Michael. Camera Works: Photography and the Twentieth-Century Word. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP, 2005.

Nyberg, Amy Kiste. Seal of Approval: The History of the Comic Code. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1998.

Pedri, Nancy. “Cartooning Ex-Posing Photography in Graphic Memoir.” Literature & Aesthetics 22.2 (December 2012): 248-266.

---. “When Photographs Aren’t Quite Enough: Reflections on Photography and Cartooning in Le Photographe.” ImageText: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies 6.1 (Fall 2011): 1-18.

http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v6_1/pedri/

Postema, Barbara. “Draw a Thousand Words: Signification and Narration in Comics Images.” International Journal of Comic Art 9.1 (Spring 2007): 487-501.

---. Narrative Structure in Comics: Making Sense of Fragments. New York: Rochester Institute of Technology, 2013.

Rabb, Jane M. (Ed.). The Short Story and Photography: 1880s - 1980s. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico P, 1998.

Richten, Fred. After Photography. New York: W.W. Norton, 2009.

Round, Julia. “Visual Perspective and Narrative Voice in Comics: Redefining Literary Terminology.” International Journal of Comic Art (Fall 2007): 316-329.

Rugg, Linda Haverty. Picturing Ourselves: Photography and Autobiography. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1997.

Ryan, James R. Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1997.

Ryan, Marie-Laure, Ed. Narrative across Media: The Languages of Storytelling. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2004.

Sacco, Joe. Journalism. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2012.

Smith, Greg M. “Comics in the Intersecting Histories of the Window, the Frame, and the Panel.” From Comic Strips to Graphic Novels: Contributions to the Theory and History of Graphic Narrative.

Ed. Daniel Stein and Jan-Noël Thon. Berlin: DeGruyter, 2013. 237.

Smolderen, Thierry. 2000. The Origins of Comics: From William Hogarth to Winsor McCay. Trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2014.

Snyder, Joel. “Picturing Vision.” Critical Inquiry 6.3 (Spring 1980): 499-526. Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1977.

Sturken, Marita and Lisa Cartwright. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. New York: Oxford UP, 2009.

Szczepaniak, Angela. “Brick by Brick: Chris Ware’s Architecture of the Page.” The Rise and Reason of Comics and Graphic Literature. Ed. Joyce Goggin and Dan Hassler Forest. Jefferson, London: McFarland, 2010. 87-101.

Tan, Shuan. The Arrival. Melbourne: Arthur A. Levine Books, 2006.

Warburton, Nigel. “Varieties of Photographic Representation: Documentary, Pictorial, and Quasi-documentary.” History of Photography 15 (Autumn 1991): 203-210.

Watson, Julia. “Autographic Disclosures and Genealogies of Desire in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home.” Biography 31.1 (Winter 2008): 27-58.

Wolk, Douglas. Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What they Mean. Cambridge: De Capo, 2007.

Woo, Benjamin. “Reconsidering Comics Journalism: Information and Experience in Joe Sacco’s Palestine.” The Rise and Reason of Comics and Graphic Literature: Critical Essays on

the Form. Ed. Joyce Goggin and Dan Hassler-Forest. Jefferson: McFarland, 2010.

177.

Nancy Pedri is Professor of English at Memorial University of Newfoundland. Her major fields of research include word and image studies, photography in contemporary literature, and comics studies. Her co-authored article, “Focalization in Graphic Narrative,” won the 2012 Award for the best essay in Narrative.