Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur:

Proceedings of the Canadian Communication Association (CCA’09), 2009, 2009-05-30

READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE.

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright

Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la

première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. Si vous n’arrivez pas à les repérer, communiquez avec nous à PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at

PublicationsArchive-ArchivesPublications@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information.

NRC Publications Archive

Archives des publications du CNRC

This publication could be one of several versions: author’s original, accepted manuscript or the publisher’s version. / La version de cette publication peut être l’une des suivantes : la version prépublication de l’auteur, la version acceptée du manuscrit ou la version de l’éditeur.

Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at

Perception and Use of Video by Today’s Youth

Molyneaux, H.; Fournier, H.; Simms, D.

https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits

L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site

LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB.

NRC Publications Record / Notice d'Archives des publications de CNRC: https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=b3d9a7b1-1ce9-48b5-bca3-ecf63535338d https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=b3d9a7b1-1ce9-48b5-bca3-ecf63535338d

Perception and Use of Video by Today’s Youth

Molyneaux, H., Fournier, H., and Simms, D.National Research Council of Canada {first name. last name}@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

Abstract

Purpose: With the success of Skype, YouTube, Google and Yahoo Video, videoconferencing and online video are becoming ubiquitous means of communication. Youth are often perceived as the “digital generation”; as a result scholars pay greater attention to technology use in adult populations (Jenkins, 2004; Livingston & Helsper, 2007). Few studies examine how youth actually engage with video technology in everyday life to communicate with friends and family. This study examines how youth (ages 15-18) currently perceive and use video as a communication tool. Method: This study analyzes the results of surveys and focus groups conducted with Canadian high school students taking part in two separate Virtual Classroom sessions. Data related to their perception and use of video communication technologies in everyday life were analyzed using both quantitative and qualitative methods. Results: The analyses indicate that although video and videoconferencing were not frequently used in everyday communications, youth perceived video as a useful means of communication. In the focus groups, participants discussed watching online video and selectively using videoconferencing to communicate with close friends and family members located at a distance. Conclusions: While the youth in this study regarded video and videoconferencing as important tools for communication, they did not use these technologies for communication on a regular basis. Students‟ perceptions of video as a broadcast medium and videoconferencing as a formal and intimate means of communication affected the ways in which they used video. Data on perceptions of video point to important differences in the current use and perceptions of video as a readily accessible medium for communication.

Keywords

Canada, youth, communication, digital divide, computers, video, text messaging, social networking, cell phones, telephone, social presence.

Introduction

Of all of the G7 countries, Canada has the highest ratio of households using broadband connections (CRTC, 2008). Internet use is prevalent among Canadian youth, with 96% of those aged 12-17 currently going online (Zamaria & Fletcher, 2007). Young people in Canada are increasingly using communication technology and diverse technologies to communicate. This paper investigates preferences for various types of communication technologies, including online video and videoconference, and highlights the diverse

ways in which young people utilize a variety of communication media within the Canadian context.

In order to examine the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) by Canadian high school students we conducted two separate data collections following Virtual Classroom sessions held in 2007 and 2008. Initiated in 1996 at the

Communication Research Centre (CRC), the Virtual Classroom program became a joint venture between the CRC and the NRC-IIT under the Broadband Visual Communication (BVC) Research Program. The program researches and evaluates the impact of

multimedia tools and advanced infrastructure to support video mediated learning within broadband enabled learning environments (Emond et al., 2009; Milliken & Culberson, 2009).

The Virtual Classroom linked high school students across Canada by multi-site videoconference and broadband virtual cameras (BVCam) to discuss topical issues. Multi-site videoconferencing allowed students at geographically dispersed sites to communicate with each other by transmitting audio and visual data through

videoconferencing systems (Molyneaux et al., 2007; Molyneaux et al., 2008) while the BVCam allowed students to record and view short videos through a web interface (Emond, et al., 2008).

As part of the Virtual Classroom data collection, students were asked about their use of ICT, in particular, their use of video. This paper presents the analysis of data on young people‟s use of ICT collected during the “Diet and Body Image” (November 2007) and “Stem Cell Research” (April 2008) Virtual Classroom sessions (O‟Donnell et al., 2007; Simms et al, 2008). Five schools were involved in both Virtual Classroom sessions with more than 500 students participating in the first session and approximately 150 in the second session. Our data was collected from students in high schools of the three following cities: St. John‟s, Newfoundland; Fredericton, New Brunswick; and Ottawa, Ontario. The data from 208 questionnaires and the transcripts from six focus groups were analyzed.

This study investigates the perception and use of communication media while studying what types of technologies Canadian youth use in general. We were also interested in the ways in which young people communicated using these technologies, in particular video communication tools. In our study we found that the media young people used for communication not only depended on what message they wanted to convey but also their social relationship with the person with whom they are communicating.

Literature review

Although much scholarly attention has been paid to adult use of communication technologies, young people are labeled as “the digital generation” – high users of new media who are born consumers of digital tools (Jenkins, 2004; Livingstone & Helsper, 2007). The way that children and young people make use of communication technology is often assumed as “natural” and scholars pay more attention to studying adult

populations. Although young people are dubbed “online experts” and “the internet generation”, scholars have begun to challenge this labeling as myth and continue to investigate the actual ways in which young people use technology (Cheong, 2008; Jenkins, 2004; Livingstone & Helsper, 2007).

Researchers have stated that young people use communication tools in ways which are distinct from adults. For example, while e-mail is a popular means of communicating in adult populations, young people do not use e-mail as frequently. Young people also use information and communication tools in different ways than adults. In her study of teen sociality in networked publics, boyd (2008a) found that teens communicate across multiple communication channels but that the media used depends upon the reason for communication. Accordingly, if an immediate response is necessary teens will use the phone. Instant messaging (IM) is used to ask general questions and Facebook is used as an even less formal means of communicating.

Studies indicate that young people are more inclined than adults to use the internet for socializing (Zamaria & Fletcher, 2007). In Canada, statistics show that young people‟s use of communication technology is increasing. The average grade eight student in Canada is online talking to friends more than an hour a day (Media Awareness Network, 2005b).

In a 2005 study of 5,000 students between grades four and eleven, 94% of respondents had internet access at home. Of these young internet users, 23% responded that they owned cell phones and 22% had webcams. When the data from the grade 11 group was isolated, these numbers increased to 46% and 30% respectively (Media Awareness Network, 2005a). Internet access via wireless devices is low in Canada – but higher in the youth population (Zamaria & Fletcher, 2007). Adoption of multi-function applications of cell phone is low in Canadian but higher among Canadian youth, who use the text messaging, camera and video functions of their cell phones twice as often as their adult counterparts (Zamaria & Fletcher, 2007).

A 2006 PEW internet and American life survey of 935 teens aged 12-17 found that the young people used a variety of communication media, from fixed-line phones and cell phones to e-mail. Some teens, dubbed “multi-channel teens” by the researchers, used multiple communication technologies everyday (Lenhart, 2007). The survey also found that teens are also likely to multitask while sending instant messages, visiting websites or playing computer games. A 2006 Kaiser Family Foundation study found that 81% of young Americans use more than one media at once during a typical week (Foehr, 2006). Young adults in Canada also are interested in online video. In a recent study of 60 YouTube users from a university in Atlantic Canada, researchers found that 55.0% were frequent visitors; 26.7% had posted comments to videos on YouTube and 11.7% had posted videos to the site (Milliken et al., 2008). Young people are also showing growing interest in using synchronous video. The Canada Online! report states that new internet communication applications like Skype video is gaining popularity amongst young

internet users. Young Canadians are also expressing growing interest in posting photographs and video (Zamaria & Fletcher, 2007).

A 2007 PEW study investigating the video habits of 2,200 young adults and adults in the United States notes that online video was commonly watched; 57% of adults with internet access used it to watch video – 19% on a daily basis. Young adults (18-29) were even more likely to watch video – 76% watching videos (compared to the 57% of adults); 31% reporting daily viewing (compared to 18% daily use –ages 30-49; 12% ages 50-64; 10% of those 65 and older). Researchers found that 67% of young adults shared links to videos with their friends. Young adults were also the most active users of the participatory features of online video (Maddon, 2007). In a 2006 study of 1,060 adolescents in the Netherlands, researchers discovered that 57% used webcams while on instant messaging programs at least occasionally, while 32% sometimes also used microphones (Peter, Valkenburg & Schouten, 2006).

Video can aid in communication by adding social presence. Social presence, a term originally coined by Short, Williams and Christie (1976) was defined as the “degree of salience of the other person in a mediated communication and the consequent salience of their interpersonal interactions” (p. 65). Social presence and media richness theories suggest that increased richness leads to increased social presence. For example, video with its greater ability to support visual cues, such as facial expression recognition, will give people a greater sense of social presence than audio alone (Roussel & Gueddana, 2007).

Social presence refers to the quality of the communication medium. According to Short and colleagues (1976), the social presence of a media varies in degrees, and this variation helps determine how people interact. They hypothesize that the users themselves know that different media have different levels of social presence and they choose which media they use to communicate with accordingly. Social presence is primarily measured by the semantic differential technique, in which users rate communication media on a seven point scale to determine the degree to which the medium is personal (or impersonal). Short et al. (1976) suggest that the social presence of the medium can either contribute to the intimacy of the medium or to a feeling of distance.

A more recent way of classifying social presence is along three themes: elements of shared space, being involved and engagement. Shared space is determined by the elements of co-presence, co-location and mutual awareness in a physical space. Being involved is characterized by the experience of psychological involvement, which encompasses the concepts of saliency, immediacy, intimacy, and making oneself known. Behavioural engagement refers to the amount of interaction and immediacy between participants (Biocca, et al. 2001 as cited in Rettie 2003).

In the surveys and focus groups we were interested not only in evaluating the Virtual Classroom1 but also in investigating how young people use ICTs in everyday life. In particular we were interested in addressing the following questions:

What ICTs are young people using?

In what ways are young people using ICTs?

Does the level of social presence affect young people‟s use of ICT? What are young people‟s perceptions of video as a communication tool?

Research Focus and Methodology

This study explored levels and patterns of ICT use by young Canadians. In our study, students in three high-schools in different provinces across Canada participated in a Virtual Classroom project which involved the students using multi-site videoconference to discuss diet and body image (November 2007) and stem cell research (April 2008). In both the 2007 and 2008 questionnaires students were asked about the specific technologies they used for the Virtual Classroom session – videoconferencing and the BVCam.

Research on the Virtual Classroom was approved by the ethics boards of the NRC and participating school boards and data was collected at the two Virtual Classroom sessions, in the three different locations. The data presented in the current study were 208 surveys and the transcripts of six focus groups.

The research methods included a quantitative analysis of surveys administered to the students as well as a qualitative examination of the findings of focus groups held at three different schools. For both surveys students in grades 10-12 attending the Virtual Classroom sessions from high schools in Ottawa (Ontario), Fredericton (New Brunswick) and St. John‟s (Newfoundland) were invited to participate.

For the 2007 data collection, all the students from the three schools were invited to complete the voluntary survey after the Virtual Classroom session had ended. A total of 250 students from the three schools participated in the Virtual Classroom and were offered the questionnaire. One hundred and fifty two students completed the survey, a completion rate of 61%. In 2008 students from the three schools were again invited to complete a survey. Of 60 students, 57 completed the survey, a 95% completion rate. In both the 2007 and 2008 questionnaires, we analyzed the responses to a question about how often they use communication technologies to keep in touch with acquaintances, friends and family. The communication technology options included: home telephone; cell phone (voice or text); cell phone (pictures or video); E-mail; Instant Messaging; website/blog you built yourself; video chat; watch video online; upload video to share with others; post text comment to an online video; Facebook, second life or MySpace.

1 For evaluations of the technologies used in the Virtual classroom see: Edmond et al., 2009; O‟Donnell et

Students reported their frequency of use of each technology on a five-point Likert scale with end points Never/rarely (1) and Everyday (5). SPSS statistical analysis software was used to investigate technology use.

For the focus groups, students were invited to participate after the Virtual Classroom session and the questionnaires had been completed. Some students had classes and could not stay for the focus groups. Focus groups ranged in size from 5 to 36 students. Both the 2007 and 2008 focus groups consisted of high-school students in Ottawa, Fredericton and St. John‟s and were conducted by a researcher in each location. Focus groups ran as short as 15 minutes in Ottawa (2007) to as long as 42 minutes in Fredericton (2008). Participation rates in the 2007 and 2008 focus groups were different due to the smaller overall group size in 2008.

In the focus groups, the researchers followed a semi-structured interview guide with mostly open-ended questions and probes to explore areas of interest. The questions covered the Virtual Classroom session the students had just attended as well as questions about technology, including their favourite communication technologies, and who they communicate with using these technologies. A quantitative analysis was preformed on the focus group transcripts, and several common themes were identified.

Research findings

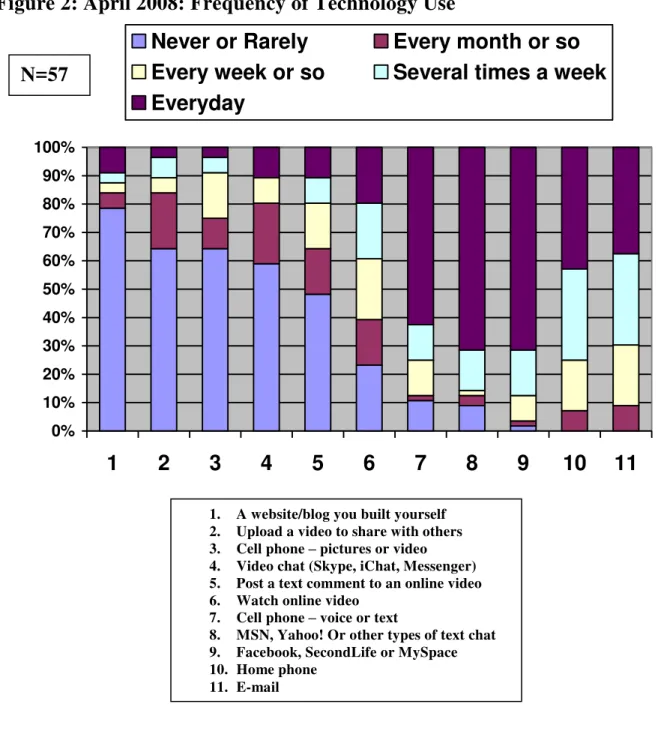

The 2007 survey revealed that computer-based chat, social networking sites, the home phone and the cell phone (voice or chat) were the most popular communication media for everyday use; however, some students reported never or rarely using social networking sites, the home phone and e-mail (Figure 1). In the 2008 survey all students reported using the home phone and e-mail, but social networking sites, computer-based text chat and cell phone voice or chat were the most popular communication choices for everyday use. The home phone fell to fourth and e-mail was the fifth most important tool used on a daily basis (Figure 2).

In both surveys the use of a user-generated blog or website was the least popular means of communication, with the vast majority of students reporting never or rarely using the tool. Also video – either synchronous, like video chat, or asynchronous, like on-line video or pictures and video taken on a cell phone, were also less likely to be used by the students on an everyday basis, and a high percentage of students reported never or rarely using video communication technology (Figure 1; Figure 2).

An examination of the data from just the surveys might indicate that video does not have an important role in the communication lives of Canada‟s youth. However, an examination of the student‟s opinions of different types of technologies in the focus groups revealed some interesting findings about the role of video and young people‟s communication methods.

The focus groups analysis revealed that young people were not only using a variety of communication media but also that they choose the communication medium based on

their audience. Also, the communication medium depended on the degree to which the young people were multitasking – an activity common when communicating with people via texting or social networking sites.

In general, the findings of the focus group also identified similar least favored and most favoured technologies. Students in Ottawa mentioned using e-mail to communicate with others living in foreign countries, because of the time difference and calling people over the cell phone if they really needed to contact them (Ottawa, 2008). However, students stated their preferences for social networking sites (except MySpace, which students in Ottawa, 2008, declared “Dead and buried”) over e-mail:

Researcher: And so, will you use Facebook more than just a regular hotmail email?

[Group: Ya]

Female (F): Ya I don‟t send e-mails much anymore, I just send messages on Facebook, they‟re one and the same thing

Researcher: And why? What's so lucrative about Facebook?

F: I think people check it a lot more often

F: Also there‟s a lot of things on it so people are on it more often doing like, other things and not just that, like I don‟t check my email that much

F: It‟s also easier, it has everyone‟s names so you just type in their names and then you can send them a message

F: Ya, it‟s a lot more…

F: You don‟t have to find out what their email address is or anything

Male (M): And like with hotmail you just go and send a message and that‟s it but with Facebook you‟re looking at like pictures and everything else too. It‟s a little more personalized I guess because I guess in a sense like all the info, everything is right there (Fredericton, 2008).

The students in Fredericton stated that they found Facebook easier to use than e-mail, since they did not have to remember addresses, just the names of their Facebook “Friends” – the people that they added to their Facebook page. Also they found Facebook to be more useful than e-mail because of the variety of information available, like photograph albums, and the fact that their peers check Facebook on a regular basis. The social networking site‟s perceived usability and usefulness by the students may explain its popularity with the group.

Students in the focus groups not only preferred Facebook over e-mail but also expressed their general dislike of talking over their cell or home telephone, aside from short messages. Some of the students mentioned long distance costs as a reason for their preference for texting. They mentioned that they rarely used cell phones for verbal conversations, except when the air time is free in the evenings and during the weekend, but instead use them most often for text messages. Some students mentioned that they only talk on the phone to their parents who are not as good at texting or don‟t text at all (Fredericton, 2008). Students in St. John‟s proved to be the exception, stating in the 2008

focus group their preference for fixed-line phones over cell phones because they are less expensive to use (St. John‟s, 2008).

Focus group analysis supports the survey findings in that the overall favorite communication media for both the young men and women were Facebook, MSN, and cell phone texting (Fredericton, 2008; Ottawa, 2008). The students, however, did not use these favorite media indiscriminately, but chose their means of communication according to who it was they were communicating with.

The students in the 2008 Fredericton focus group identified three main levels of communication. Facebook was viewed as the most general means of communicating. MSN text messenger was seen as a means of communicating with a slightly narrower group of friends and family. Text messaging over cell phone, used within an even smaller group of contacts, was viewed as the most personal and private means of communication of the three media. While Facebook and MSN messenger were used extensively by the students, texting on cell phones was identified as the main form of communication with family and close friends:

F: Ya and it kind of goes through because Facebook is like the most general thing ever and then you‟ve got like MSN like your Facebook friends narrow down to like closer friends and then you have your texting which is like the closest.

[Group: Ya]

F: so it‟s kind of like those three levels [Group: Ya]

M: Ya, like texting is like whoa, you guys are close

F: Ya, it's like shifted though so like if you talk to someone over text it's like way more personal than MSN and like MSN is way more personal than Facebook so it kind of just like goes through the ranks (Fredericton 2008).

--- F: Cause your cell phone number like only people you give it to can get it but like more people can get your email address and Facebook like anyone can get it. Ya. Cell phones are like the most private and like secure thing, the most personal (Fredericton, 2008).

Students in all three of the focus groups in 2008 spoke of a social hierarchy implicit with the three most popular types of communication media. Students use cell phone calls or texting primarily for friends and family members to whom they were particularly close (Fredericton, 2008; Ottawa, 2008). MSN text messaging was used for a larger group of people, while Facebook was used most frequently to communicate with more casual acquaintances and people they didn‟t know very well (Ottawa, 2008). Students reported using computer-based communications, like MSN chat and Facebook, more frequently to communicate with people in other cities, especially those living outside North America (St. John‟s, 2008; Fredericton, 2008)

While viewing videos online was discussed in all the focus groups, the students did not report making videos in order to communicate with others. They felt that while making

videos was fun, good videos took a lot of time to plan and they felt awkward talking to the camera (St. John‟s, 2008). Also students made the observation that producing a video, unlike text messages, usually requires planning it out and a script. As a result, video would be a medium that was “less of a communication and more of an argument” (Fredericton, 2007). Students in Ottawa stated that it is harder to respond to a posted video than to have a conversation instantly over videoconference (Ottawa, 2007).

According to the focus groups, - using video for communication occurs during such activities as desktop videoconferencing through Skype or MSN video messenger. Students in the focus group mainly used their webcams to communicate with family members living in another country (Fredericton, 2008; St. John‟s, 2008). In some cases, videoconferencing was the only way in which students could see their relatives or close friends for an extended period of time:

Researcher: Do you guys think that videoconferencing itself is a good way to communicate with people in different locations? …

M: Well I for one, my cousin lives in Australia so there is no real way that we can communicate without flying out there so videoconferencing is definitely a benefit. When you‟re talking you know I can see her three-year-old son and that you know rather than just hearing it and all that so it‟s definitely better (St. John‟s, 2008). --- F: I know a girl who, her boyfriend goes to hockey school away, and like they communicate through videos and they talk to each other. Rather than being on the phone, they actually have video conversations, which is kind of cool. That‟s kind of for a different purpose (St. John‟s, 2007).

The students also stated that increased social presence was the main benefit of video communication:

Researcher: So what do you think that the effect would be on your

relationships if you didn’t have these technological tools to stay in contact with people…if you didn’t have video how would it affect your relationships with people who are far away?

F: Ya, I just don‟t think we would be as close because I wouldn‟t be able to put a face to any of it. Like a lot of the people… I left a long time ago and a lot of the people… a lot of the time I don‟t really know what everyone looks like and stuff so when they are there and I can see them it puts more of a face to like what I‟m talking to them about and I can relate to them more I guess

M: It‟s way more personalized F: Ya, its way more personal

M: Like my cousin, she lives in Thailand, and before that she lived in Ottawa so I didn‟t really see her, except for when I was younger, but when she moved to Thailand she videoconferenced with us like, via MSN messenger and like, I don‟t know, it was just like cool to see what she looked like now as opposed to my image I had of her when she was 10.

M: Ya, it makes it like I mean it makes it more as if they are here, like you can see them and talk to them its as if they are here (Fredericton, 2008).

Students from all three locations seemed to agree that videoconferencing was a more personal means of communication. However, they did note that there were times where video was appropriate, and times where it would be cumbersome.

F: It‟s great talking on a web cam with someone like, “live” feed. But posting videos is a totally different story. I wouldn‟t; I don‟t do it.

F: I don‟t do it either, but at the same time the visual aspect of it is … F: Makes it more personal

F: Yeah, it‟s more personal.

M: I personally only use video on MSN only when, honestly, one of my friends changes their appearance, if they get a new haircut or new clothes or something and they want to model it off. Even my cousin, she got a new haircut and she just had to show me. That‟s just how we do it. I never use it to sit there and talk to someone. I‟ve never been that interested in that approach, in my entire computer experience (Ottawa, 2007).

In the focus groups the students all seemed to agree that the use of video, especially videoconferencing, added social presence and was a much more personal means of communication than texting or social networking. So why did the students use video less often? As Short, et al. (1976) noted in their discussion of social presence, the students were choosing their communication medium according to the degree of social presence they wished to communicate. The students created a hierarchy of relationships and the levels of intimacy each required, and that dictated which communication tools they used. The closer the relationship, and further the distance, the more likely students were to use video. However, for people living nearby, or for more casual acquaintances, students were more likely to use text and social networking sites.

There is also another potential explanation as to why the students were not employing video communication media as much as text-based tools. In the focus group, the students talked about how they actually use communication media, a discussion which revealed the importance of communication media that allow for multitasking.

The young people in the focus groups emphasized the need for multitasking while communicating. The fact that the students use communication media while engaging in other activities is not surprising. The 2007 Canada Online report notes that multitasking is common for young people, who often talk on telephone or cell, listen to music, and watch television while they are online (Zamaria & Fletcher, 2007). Research on European and Quebec youth reveals that communication media are used simultaneously with other media: for example, young people are chatting on MSN messenger while watching TV or listening to music (Bevort & Verniers, 2008).

Students in the focus group mentioned communicating with others while doing online activities. For example, one young man in Fredericton noted “…if I‟m not at the

computer my phone‟s always with me like if I‟m playing video games I‟ll stop a game just to see what my text says” (Fredericton, 2008)

It is interesting to note that students in the Virtual Classroom focus groups also reported multitasking while using communication technologies. These young people stated the regular practice of carrying on conversations with various people not only simultaneously – a feat commonplace on computer-based text programs like MSN messenger - but also over a variety of different communication media:

F: I think when we‟re on MSN or something, that we‟re also like multitasking so it‟s just a side thing so it‟s not like we‟re on video too, and you‟re watching each other that‟s taking all of your focus...

F: When we‟re on the computer, I can guarantee you we‟re doing three things. Like we‟re on email, MSN, doing your homework and on Facebook.

F: You never just go on the computer just to go on MSN.

F: And you‟ll probably even be on the phone while you‟re on the computer. Talking to someone. Even doing a project, and then you‟re on the computer writing up the project, talking to friends on MSN, it‟s multitasking more than it‟s just sitting and watching videos and posting (Ottawa, 2007).

Discussion

This study collected data in 2007 and 2008 from high-school students in three provinces across Canada. Analysis of the data offers a glimpse into the digital world in which young Canadians communicate. The debate over the use of newer ICT (e.g., cellular phones, social networking sites and video communication technologies) in the classroom generally ignores the powerful influence mediated signs and messages have in the formation of identities among youths. Our findings indicate how young people are

currently using communication technologies, underscoring their potential use as powerful pedagogical tool within the classroom.

The findings from the Virtual Classroom surveys and focus groups also reveal important information about what types of communications were used most often. Young men and women use similar technologies, often simultaneously, in the same ways to communicate with close family and friends whether they are in the same community or elsewhere as well as more casual acquaintances. The hierarchy of ICT use is represented in Figure 3 to show student preferences for some communication tools (social networking, computer and cell phone texting) over others (home phone, e-mail and video communication). Researchers working on the Young Canadians in a Wired World report note that the popularity of computer chat and social networking relates to social status. They emphasize the idea that the size of their contact list acts as a social marker for young people (Media Awareness Network, 2005b). Long lists of social contacts seemed common; only a few students in the study mentioned that they kept their contact list short and included only people they knew and communicated with on a regular basis. Although young people noted that they did not communicate with everyone on their list,

researchers suggest that the larger the contact list, the more social prestige is demonstrated by the young person (Media Awareness Network, 2004). In her research on young people‟s use of social networking sites, danah boyd (2008b) notes that teens replicate social hierarchies online. Some teens use social networking sites to expand their social circle, but they still classify their online friends in many ways (Livingstone, 2008). Connections between teens can be publically displayed through “friends” lists and applications like “Top 10” friends. This display of friendship is used by young people to establish social status online (boyd, 2008b) This is one potential explanation why the base of the communication technology pyramid is Facebook/MSN chat, but it does not highlight the ways in which young people use different communication tools to express not just their own status, but the status of others.

While students used social networking sites and texting more than other communication technologies like video, the communication tool students used depended upon their relationship with the recipient. The hierarchy of communication tools was based on the intimacy of the relationship between the student and the other person. Although students used video technology less, it was often reserved for communicating with the people at the top of the pyramid (Figure 3), primarily as a communication tool for family and close friends living at a distance. Cell phone text and talk were used to communicate with friends or family members living in close proximity. MSN was seen as the next level, a slightly less personal means of communication. Facebook was the most widely used tool to communicate both with intimate friends and family as well as casual acquaintances and even online friends.

The qualitative data from the focus groups supports social presence theory in relation to video communication. Students reported using video technology for more personal communication with friends and family living at a distance and expressed appreciation for the great social cues offered by video. However, video was not the preferred medium for everyday communication. Students didn‟t see the value of using video for conversations with casual acquaintances. Also the young people in the focus groups identified multitasking communication technologies as a key behavior; perhaps video was not as widely utilized by these young people because it is difficult to maintain social presence through video while multitasking. A student also felt video communication, especially asynchronous video communication, was too formal and needed to be planned out.

In the article “Beyond „Beyond Being There‟” researchers note that oral and text based communication (telephone and e-mail) remain the most popular means of communication, and that while videoconferencing applications are available (some even free) few use them on a regular basis. Authors Roussel & Gueddana (2007) suggest that in person communication should not be imitated by video communication media, but should be developed to go beyond so that people would prefer using these systems even if they have the option of meeting in person. Some researchers have focused on immersive, experiential and effective telepresence with the goal of making video communications more natural, more intuitive and more realistic. However, the focus on synchronous communication and complex technology limits the use of video to formal

and highly planned interactions. Instead Roussel & Gueddana advocate a “beyond being there approach” which is more diverse and involves collaborative uses of video. They suggest one approach to going beyond video us to combine video with other media – for example, with instant messaging (Roussel & Gueddana, 2007). While Roussel‟s article refers to workplace communications, this approach may also aid in young people‟s communication. The youth in our study already combine a variety of communication media in order to communicate with others, and might appreciate a collaborative and diverse means of video communication.

Conclusions

Researchers were limited to collecting data from a select number of schools participating in the Virtual Classroom sessions due to ethics approval and the need to be at the site to collect data. As a result survey and focus group data were only collected from three schools after each session. Young people in high schools in St. John‟s, Fredericton and Ottawa were given the opportunity to give feedback, and their responses are not representative of those of all Canadian youth. The focus groups that were conducted at each of the schools were comprised of self-selected students. These students may have had different levels of engagement with ICT and their view might not be representative of the broader population.

This paper examines the ways in which Canadian youth appropriate communication technologies. Patterns of use reveal a hierarchy not only of types of technology, but also a hierarchy of the young people‟s relationships with others. Social networking sites like Facebook were the most commonly used communication tool while young people used media with a high level of social presence, like videoconferencing for infrequent and intimate communications with close friends and family members. Technology use and the technological preferences of young people are important factors for scholars and designers to consider. Our findings show a glimpse at the current use of communication technologies by Canadian youth and suggest future possibilities of new media technologies such as video communication technologies.

References

Bevort, E., Verniers, P. (2008). The Appropriation of New Media and Communication Tools by Young People Aged 12-18 in Europe. Empowerment Through Media Education: An Intercultural Dialogue. U. Carlsson, S. Tayie, G. Jacquinot- Delaunay and J. M. P. Tornero. Goteborg, Sweden, The International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media: 89-100.

Boyd, D. (2008a). Taken Out of Context: American Teen Sociality in Networked Publics. (Dissertation) University of California, Berkley.

Boyd, D. (2008b)Why Youth ♥ Social Network Sites: The Role of Networked Publics in Teenage Social Life. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Learning – Youth, Identity, and Digital Media Volume. Cambridge: MA: MIT Press: 119-142.

Cheong, P.H. (2008). The Young and the Techless? Investigating Internet use and Problem-solving Behaviors of Young Adults in Singapore. New Media & Society 10(5): 771-791.

CRTC (2008). Communications Monitoring Report. Ottawa: Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly 13(3): 319-340.

Dresang, E. T., Gross, M., Holt, L. (2007). New Perspectives: An Analysis of Gender, Net-Generation Children, and Computers. Library Trends 56(2): 360-386. Emond, B., Molyneaux, H., Spence, J. Brooks, M. (2009). Student Perceptions of

Broadband Visual Communication Technology in the Virtual Classroom: A Case Study. Proceedings of the International Communications Association (ICA 2009), Chicago, United States, May 21-25.

Emond, B., Scobie, D., Allen, M., Postma, M., and McIver, W.J. (2008). An H.323 Broadband Virtual Camera for supporting asynchronous visual communication in large groups, Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society (IEEE ISTAS 08), Fredericton, Canada, June 26-28.

Foehr, U.G. (2006). Media Multitasking among American Youth: Prevalence, Predictors and Pairings. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Haddon, L. (2008). Young People's Diverse use of Multimedia Mobile Phones. 2008 Conference of the International Communications Association. Montreal.

Race, Gender, and Information Technology Use: The New Digital Divide. CyberPsychology & Behavior 11(4): 437-442.

Jenkins, H. (2004). The Myths of Growing up Online. Technology Review. Retrieved April 2, 2009 from http://www.technologyreview.com/biotech/13773/

Lenhart, A., Madden, M., Macgill, A.R., Smith, A. (2007). Teens and Social Media. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Washington D.C.

Livingstone, S. (2008). Taking Risky Opportunities in Youthful Content Creation: Teenagers‟ use of Social Networking Sites for Intimacy, Privacy and Self- expression. New Media & Society. 10(3): 393-411.

Livingstone, S., Helsper, E. (2007). Gradations in Digital Inclusion: Children, Young People and the Digital Divide. New Media & Society. 9 (4): 671-696.

Looker D., Thiessen, V. (2003). The Digital Divide in Canadian Schools: Factors Affecting Student Access to the use of Information Technology. Minister of Industry: Ottawa, Ontario, 2003.

Madden, M. (2007). Online Video. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project.

Mahatanankoon, P., O‟Sullivan, P. (2008). Attitude toward mobile text messaging: An expectancy-based perspective. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 13: 973-992.

Media Awareness Network. (2004). Young Canadians in a Wired World: Phase II: Focus Group. Ottawa, Ontario.

Media Awareness Network. (2005a). Young Canadians in a Wired World: Phase II: Student Survey. Ottawa, Ontario.

Media Awareness Network. (2005b). Young Canadians in a Wired World: Trends and recommendations. Ottawa, Ontario.

Milliken, M. and A. Culberson (2009). The Virtual Classroom: Broadband And Big Ideas Connect Canadian Students. Canadian Teacher Magazine, January 2009, pp. 24- 25.

Milliken, M., Gibson, K., O'Donnell, S. (2008). User-generated video and the online public sphere: Will YouTube facilitate digital freedom of expression in Atlantic Canada? American Communication Journal. Volume 10, Number 3. Fall 2008. Milliken, M., Gibson, K., O‟Donnell, S., Singer, J. (2008). User-generated Online Video

International Communications Association (ICA 2008), Montreal, Canada, May 22-26.

Molyneaux, H., O'Donnell, S., Liu, S., Hagerman, V., Gibson, K., Matthews, B., Fournier,

H., Scobie, D., Singer, J., McIver, W. Jr., Emond, B., Brooks, M., Oakley, P. (2007). Good Practice Guidelines for Participatory Multi-Site Videoconferencing. Fredericton: National Research Council.

Molyneaux, H., O‟Donnell, S., Fournier, H., Gibson, K. (2008). Participatory Videoconferencing for Groups. Proceedings of the IEEE International

Symposium on Technology and Society (IEEE ISTAS 08), Fredericton, Canada, June 26-28.

O‟Donnell, S., Singer, J., Milliken, M., Fournier, H. (2007). BVC-SI - Technical Update Report. Fredericton NB, National Research Council: 11.

Peter, J., Valkenburg, P.M., Schouten, A.P. (2007). Precursors of Adolescents‟' use of Visual and Audio Devices During Online Communication. Computers in Human Behavior 23: 2473-2487.

Rettie, R. (2003). Connectedness, Awareness and Social Presence. 6th Annual Workshop on Presence. Aalborg, Denmark.

Roussel, N., Gueddana, S. (2007) Beyond „Beyond Being There‟: Towards Multiscale Communication Systems. ACM. 238-246.

Simms, D., Milliken, M., O‟Donnell, S., Fournier, H., and Emond, B. (2008). BVCam in the Virtual Classroom. May 2008.

Short, J., Williams, E., Christie, B. (1976) The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. Toronto: John Wiley & Sons.

Zamaria, C., Fletcher, F. (2007). Canada Online! The Internet, Media and Emerging Technologies: Uses, Attitudes, Trends and International Comparisons. Canadian Internet project.

Appendix

Figure 1: November 2007: Frequency of Technology Use

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Never or Rarely

Every Month or so

Every Week or so

Several Times a Week

Every Day

1. A website/blog you built yourself 2. Upload a video to share with others 3. Cell phone – pictures or video 4. Video chat (Skype, iChat, Messenger) 5. Post a text comment to an online video 6. Watch online video

7. Cell phone – voice or text

8. MSN, Yahoo! Or other types of text chat 9. Facebook, SecondLife or MySpace 10. Home phone

11. E-mail

N=152

Figure 2: April 2008: Frequency of Technology Use

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Never or Rarely

Every month or so

Every week or so

Several times a week

Everyday

1. A website/blog you built yourself 2. Upload a video to share with others 3. Cell phone – pictures or video 4. Video chat (Skype, iChat, Messenger) 5. Post a text comment to an online video 6. Watch online video

7. Cell phone – voice or text

8. MSN, Yahoo! Or other types of text chat 9. Facebook, SecondLife or MySpace 10. Home phone

11. E-mail

N=57

Figure 3: Pyramid of Communication Technologies

Video

Cell phone text; Cell phone and home phone

calling

Computer-based text chat: MSN, Yahoo! and others

Social Networking Sites: Facebook, Second Life or MySpace

Close friends and family out of the country

Close family and friends

Friends and family; casual acquaintances