Copyright © 2017 European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

For permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com 930

doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx027 Advance Access publication February 21, 2017 Original Article

Original Article

Risk of Rectal Neoplasia after Colectomy and

Ileorectal Anastomosis for Ulcerative Colitis

Mathieu Uzzan

a, Julien Kirchgesner

b, Nadia Oubaya

c,

Aurélien Amiot

d, Jean-Marc Gornet

e, Philippe Seksik

b,

Stéphane Nancey

f, Eddy Cotte

g, Matthieu Allez

e, Gilles Boschetti

f,

David Laharie

h, Nicola de Angelis

i, Maria Nachury

j,

Anne-Laure Pelletier

k, Vered Abitbol

l, Mathurin Fumery

m,

Antoine Brouquet

n, Anthony Buisson

o, Romain Altwegg

p,

Jacques Cosnes

b, Yves Panis

q, Xavier Treton

aaDepartment of Gastroenterology, IBD and Nutritive Assistance, Hôpital Beaujon, APHP, Clichy, France bDepartment of

Gastroenterology, Hôpital Saint Antoine, APHP, Paris, France cDepartment of Epidemiology and Clinical Research, Hôpital

Beaujon, APHP, Clichy, France dDepartment of Gastroenterology, Hôpital Henri Mondor APHP, Créteil, France eDepartment

of Gastroenterology, Hôpital Saint Louis, APHP, Paris, France fDepartment of Gastroenterology, CHU Lyon Sud,

Pierre-Bénite, France gDepartment of Digestive Surgery, CHU Lyon Sud, Pierre-Bénite, France hDepartment of Gastroenterology,

Hôpital du Haut-Levêque, CHU Bordeaux, Pessac, France iDepartment of Digestive Surgery, Hôpital Henri Mondor, APHP,

Créteil, France jDepartment of Gastroenterology, CHRU Lille, Lille, France kDepartment of Gastroenterology, Hôpital

Xavier Bichat, APHP, Paris, France lDepartment of Gastroenterology, Hôpital Cochin, APHP, Paris, France mDepartment

of Gastroenterology, CHU Amiens, Amiens, France nDepartment of Digestive Surgery, Hôpital du Kremlin-Bicêtre, APHP,

France oDepartment of Gastroenterology, CHU Estaing, Clermont-Ferrand, France pDepartment of Gastroenterology,

CHRU Montpellier, Montpellier, France qDepartment of Digestive Surgery, Hôpital Beaujon, APHP, France

Corresponding author: Mathieu Uzzan, MD, Hopital Beaujon, Service de Gastroentérologie, MICI et Assistance Nutritive, 100 Boulevard du Général Leclerc, 92110 Clichy, France. Tel: +33-1-40-87-56-00; Fax: +33-1-40-87-45-74; Email address: mathieuuzzan@gmail.com

Abstract

Background and Aims: Colectomy can be required in the management of ulcerative colitis [UC]. While ileal-pouch anal anastomosis [IPAA] is the recommended reconstruction technique, ileorectal anastomosis [IRA] is still performed and might present some advantages. However, the risk of rectal neoplasia might limit its indication. The aims of our study were to determine the incidence of rectal neoplasias following IRA for UC and to identify risk factors associated with rectal carcinomas.

Methods: We performed a multicenter retrospective study including patients who underwent IRA for UC from 1960 to 2014 in 13 centers. Cox-proportional hazard models were used to determine carcinoma-associated risk factors.

Results: A total of 343 patients were included, with a median follow-up of 10.4 years after IRA. At the end of follow-up, 38 rectal neoplasias (including 19 carcinomas) were diagnosed, and 7 patients [2%] had either died from rectal carcinoma or had a metastatic disease. Incidences of rectal carcinoma after IRA for UC were estimated at 3.2% at 10 years and at 7.3% at 20 years, whereas incidences of

Abbreviations: IBD, Inflammatory bowel diseases; IPAA, Ileal pouch anal-anastomosis; IRA, Ileorectal anastomosis; PSC, Primary sclerosing cholangitis; UC, Ulcerative colitis.

neoplasia were estimated at 7.1% and 14% at 10 and 20 years, respectively. In multivariate analysis, age at IRA, IBD duration, primary sclerosing cholangitis [PSC] and history of prior colonic carcinoma were independently associated with the risk of rectal carcinoma following IRA.

Conclusion: The risk of rectal carcinoma in patients with IRA for UC remains, and this justifies long-term endoscopic surveillance. Either IPAA or end ileostomy should be considered in ‘high-risk’ patients i.e. those with PSC and/or with prior colonic neoplasia.

Key Words: Ulcerative colitis; ileorectal anastomosis; rectal carcinoma; rectal neoplasia

1. Introduction

Despite progress in medical management, colectomy for ulcera-tive colitis [UC] is still performed in up to 30% of patients.1–3 It is required in several circumstances, including refractory disease to medical therapy, and colonic neoplasia.4 Patients with inflammatory bowel diseases with colonic involvement are at higher risk of devel-oping colonic neoplasia compared with the general population.5 This potentially lethal complication usually necessitates a colectomy. While ileal-pouch anal anastomosis [IPAA] is recommended by the European current guidelines as the preferential reconstruction technique after colectomy for UC,6,7 ileorectal anastomosis [IRA] appears to have some advantages. The latter include a potentially better functional outcome as well as a less complex surgical proce-dure.8 However, the fear of the occurrence of a subsequent neoplasia located on the remnant rectum might limit its indications.

To date, only limited knowledge regarding this issue is available, which is gathered in a recent meta-analysis by Derikx et al.9 The pooled prevalence of rectal neoplasia after colectomy and IRA was 2.4% among 2762 patients, with a reported follow-up ranging from 1 to 35 years. The combined analysis of three widely heterogeneous studies revealed a history of prior colonic carcinoma as a risk factor for developing rectal carcinoma after IRA.9 Other potential risk fac-tors have never been studied or have been insufficiently studied and reported. Moreover, until recently only one cohort study (including 86 patients) estimated the cumulative incidence of rectal carcinoma after IRA.10 Therefore, the available evidence regarding the risk of rectal neoplasia after IRA for UC as well as its associated risk factors remains scarce. It is mainly based on historical studies often exhibit-ing a restricted size cohort, a very variable duration of follow-up, or the occurrence of very few events, thus providing inaccurate and one-dimensional data.

To address these important and clinical practice–oriented ques-tions, we conducted a retrospective study from a large GETAID/ GETAID chirurgie cohort, and our aim was to determine the inci-dence of rectal neoplasia after colectomy and IRA for UC and to identify risk factors associated with rectal carcinoma.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

The present cohort of patients has been studied regarding the risk of IRA failure and the results of that study have already been pub-lished.11 The cohort was built from a centralized GETAID/GETAID chirurgie registry. GETAID is a consortium of French and European inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] centers. In the present study, 13 French centers participated and enrolled patients using an online registry. Data were then retrospectively collected from medical records. Colectomies and IRAs were performed from 1960 to 2014, and the last known contact date ranged from 1972 to 2015. Patients

were followed until secondary protectomy, death or last known contact date.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: patients who underwent a sub-total colectomy with IRA as the reconstruction technique; patients should be older than 18 years at cohort entry and should have an established diagnosis of UC or indeterminate colitis at the time of the colectomy. Patients with Crohn’s disease diagnosed prior to IRA were excluded. There was no limitation on the date of the colec-tomy and IRA. As no recommendation regarding the frequency of endoscopic surveillance of the remnant rectum is currently available, the endoscopic surveillance of the remnant rectum was performed according to each center’s habits. In French tertiary IBD centers, sim-ilarly to colonic surveillance, rectal endoscopy is usually performed every 2–3 years in the presence of IRA. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (the Institutional Review Board [IRB 00006477] of HUPNVS, Paris 7 University, Assistance publique des hôpitaux de Paris [AP-HP]).

2.2. End points

The primary end point was defined by the occurrence of rectal carci-noma after IRA for UC. Secondary end points were the occurrence of rectal neoplasia [including dysplasia and carcinoma] after IRA. The diagnosis of rectal carcinoma was always confirmed via histological assessment. The presence of prior colonic neoplasia was based upon the pathological findings of the surgical specimen after colectomy.

Since, over the long duration of the study, many changes in defi-nitions, grading and characterization of lesions have occurred,12 and, as there is a wide interobserver variability in dysplasia evaluation,13 low-grade and high-grade dysplasia were merged into a unique vari-able [i.e. ‘dysplasia’]. ‘Indefinite’ regarding dysplasia ‘was not con-sidered as dysplasia. The concomitant presence of carcinoma and dysplasia was classified as ‘carcinoma’. Pathological features were recorded from pathological reports.

2.3. Statistics

Quantitative variables are expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Qualitative variables are given as numbers [percentages]. The comparison of patients’ baseline characteristics according to the occurrence of rectal neoplasias was performed using Chi-square tests for qualitative variables and with a Student t test for quantitative variables. Cumulative incidences of neoplasias were assessed using a Kaplan–Meier analysis. We used a logrank test to compare survival among various subgroups. In order to identify predictors of rectal carcinoma after IRA, a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed.

Variables significant at p < 0.20 in the univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model, with a backward variable elimination procedure to assess the strength of the associations, while controlling for possible

confounding variables. The results are reported with hazard ratios [HR] and their 95% confidence intervals [95% CIs]. The alpha risk was set at 5% for the statistical significance level. Calculations were performed with SAS version 9.4 [Cary, NC].

3. Results

3.1. Background characteristics

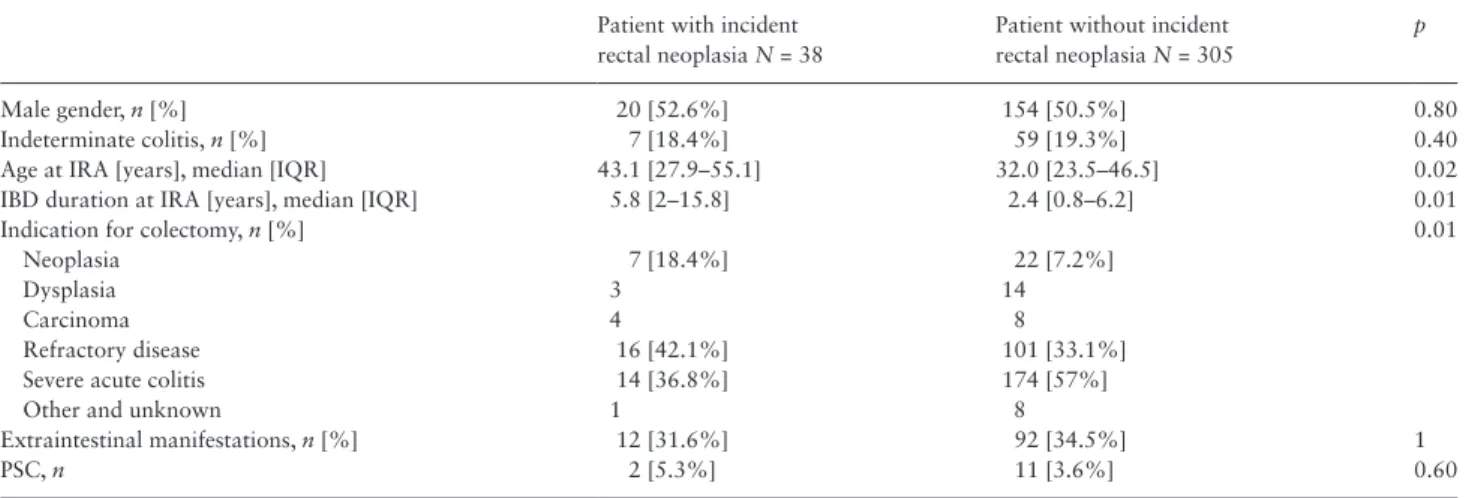

We included 343 patients from 13 centers. The median follow-up after IRA was 10.4 years (IQR [4.4–18.4]). General baseline char-acteristics with respect to the occurrence of rectal neoplasia are dis-played in Table 1. Of note, in the cohort, 13 patients [3.8%] had primary sclerosing cholangitis [PSC], the overall median age at IRA was 32.4 years (IQR [23.9–47.6]) and 8.6% of patients were oper-ated on for colonic neoplasia. The IRA was performed in 92 patients before 1990, in 165 patients between 1990 and 2005 and in 86 patients after 2005. The frequency of prior colonic neoplasia dif-fered between periods, as it was 1.2% before 1990, 5.6% between 1990 and 2005 and 20.9% after 2005.

3.2. Incidence of rectal neoplasia and rectal carcinoma after IRA

During follow-up, 38 patients were diagnosed with rectal neopla-sia. Of these, 19 had rectal carcinoma. In the overall cohort, the cumulative estimated incidence of rectal carcinoma was 1.4% (95% CI [0.5–3.3]), 3.2% (95% CI [1.5–5.9]) and 7.3% (95% CI [2.9– 12.4]) at 5, 10 and 20 years after colectomy and IRA, respectively. Respective cumulative incidences of rectal neoplasia after IRA were estimated at 3.5% (95% CI [1.8–6]), 7.1% (95% CI [4.3–10.7]) and 14.0% (95% CI [9.1–19.8]) at 5, 10 and 20 years [Figure 1].

Cumulative incidences of post-IRA incidental rectal carcinoma were estimated at 0.4% (95% CI [0–1.2]), 3.1% (95% CI [0.6–5.5]) and 7.0% (95% CI [2.3–11.5]) at 10, 20 and 30 years after IBD diagnosis, respectively.

3.3. Characteristics of patients with post-IRA incidental rectal carcinoma

The characteristics of patients with rectal carcinomas are displayed in Table 2. The median age at the time of the IRA confection was 43.5 years in patients who developed a post-IRA incidental rectal

carcinoma compared with 32.3 in patients who did not develop a post-IRA incidental rectal carcinoma during follow-up [p = 0.09]. Of note, at the time of rectal carcinoma diagnosis, 47% of patients had a concomitant presence of rectal dysplasia.

During follow-up, 7 patients [36.9%] had died from their rectal car-cinoma or had a metastatic disease [TNM Stage IV] (median follow-up after being diagnosed with rectal carcinoma: 1.5 years IQR [0.2–6.9]).

3.4. Risk factors associated with rectal carcinoma First, we performed a univariate Cox model analysis to assess for fac-tors associated with post-IRA incidental rectal carcinoma [Table 3]. Table 1. Baseline characteristics according to the occurrence of rectal neoplasia.

Patient with incident rectal neoplasia N = 38

Patient without incident rectal neoplasia N = 305

p

Male gender, n [%] 20 [52.6%] 154 [50.5%] 0.80

Indeterminate colitis, n [%] 7 [18.4%] 59 [19.3%] 0.40

Age at IRA [years], median [IQR] 43.1 [27.9–55.1] 32.0 [23.5–46.5] 0.02

IBD duration at IRA [years], median [IQR] 5.8 [2–15.8] 2.4 [0.8–6.2] 0.01

Indication for colectomy, n [%] 0.01

Neoplasia 7 [18.4%] 22 [7.2%]

Dysplasia 3 14

Carcinoma 4 8

Refractory disease 16 [42.1%] 101 [33.1%]

Severe acute colitis 14 [36.8%] 174 [57%]

Other and unknown 1 8

Extraintestinal manifestations, n [%] 12 [31.6%] 92 [34.5%] 1

PSC, n 2 [5.3%] 11 [3.6%] 0.60

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IRA, ileorectal anastomosis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients with post-IRA incidental carcinoma.

N = 19

Age at rectal carcinoma [years], median [IQR]

57.6 [44.2–71] Time between IRA and rectal carcinoma

[years], median [IQR]

12.1 [6.1–21.3] Time between IBD diagnosis and rectal

carcinoma [years], median [IQR]

28.8 [18–41.2] 20% 15% 10% Cumulative incidence (%) 5% 0% 0 5 10 Follow up (years) Any rectal neoplasia Rectal carcinoma Rectal dysplasia

15 20

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of rectal dysplasia, carcinoma and neoplasia

after IRA.

As previous colonic neoplasia appeared as an associated factor for rectal carcinoma after IRA, we assessed the cumulative incidences of rectal carcinoma and rectal neoplasia according to the presence/ absence of a history of colonic dysplasia or carcinoma.

The 10-year estimated cumulative incidence of rectal neoplasia was 30.0% [95% CI [0.8–60.8]) for patients with previous colonic dysplasia, 50.5% (95% CI [3.5–86.9]) for patients with previous colonic carcinoma and 6.0% (95% CI [3.4–9.6]) for patients with-out previous colonic neoplasia Figure 2. Regarding the risk of rectal carcinoma, the cumulative incidence at 10 years after IRA was esti-mated at 25.0% (95% [CI 0.4–57.4]), 50.5% (95% CI [3.5–86.9]) and 2.1% (95% CI [0.8–4.6]) for patients with previous colonic dys-plasia, carcinoma or without previous colonic neodys-plasia, respectively [Figure 3].

Further, using a multivariate Cox model after backward elimi-nation of non-significant variables, we determined that age at IRA, IBD duration, PSC, as well as the history of prior colonic carcinoma at the time of the colectomy, were independently associated with the risk of developing a rectal carcinoma after colectomy and IRA [Table 3]. In multivariate analysis, the period of the IRA confec-tion was not associated with the risk of rectal carcinoma (<1990 as

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with rectal carcinoma after IRA for UC. The final multivariate Cox model was established after backward elimination of non-significant variables.

uHR [95% CI] p aHR [95% CI] p

Male gender 1 [0.4–2.6] 0.94

Age at IRA +10 years 1.7a [1.4–2.2] <0.001 1.6a [1.2–2.3] 0.002

IBD duration at IRA +10 years 1.8a [1.3–2.5] <0.001 1.6a [1.2–2.2] 0.003

IRA period < 1990 Ref

1990–2005 1.9 [0.6–6.1] 0.29

>2005 4.4 [0.7–29.3] 0.12

IBD type UC Ref

Indeterminate colits 1.2 [0.3–4.1] 0.80

Active smoker at the time of IRA 0.5 [0.1–3.8] 0.5

Extraintestinal manifestation 0.9 [0.3–2.7] 0.88

Primary sclerosing cholangitis 6.1 [1.4–27.2] 0.02 8.2 [1.4–49.7] 0.02

Prior colonic neoplasia No Ref

Dysplasia 4.2 [0.5–33.2] 0.17 0.6 [0.1–6.3] 0.64

Carcinoma 11.4 [3.2–40.8] <0.001 5.9 [1.4–25.5] 0.017

uHR, unadjusted hazard ratio; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; IRA, ileorectal anastomosis; ref, reference variable; UC, ulcerative colitis. aHazard ratios for a

10-year increase, e.g. age at IRA: aHR = 1.6-fold increase in the risk of post-IRA rectal carcinoma for a 10-10-year increase in age at the time of IRA, 95% CI [1.2–2.3].

Cumulative incidence of carcinoma (%) 5%

10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% 45% 50% 55% 60% 0% 0 5 10 Follow up (years) No neoplasia at colectomy Dysplasia at colectomy Carcinoma at colectomy 15 20

Figure 3. Cumulative incidence of rectal carcinoma after IRA according to

prior colonic status at colectomy. Logrank tests: ‘Dysplasia at colectomy’ versus ‘carcinoma at colectomy’: p = 0.17; ‘Dysplasia at colectomy’ versus ‘no neoplasia at colectomy’: p = 0.08; ‘Carcinoma at colectomy’versus ‘no neoplasia at colectomy’: p < 0.001.

100%

75%

50%

Cumulative incidence of neoplasia (%)

25% 0% 0 5 10 Follow up (years) No neoplasia at colectomy Dysplasia at colectomy Carcinoma at colectomy 15 20

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence of rectal neoplasia after IRA according to prior colonic status at colectomy. Logrank tests: ‘Dysplasia at colectomy’ versus

‘carcinoma at colectomy’: p = 0.66; ‘Dysplasia at colectomy’ versus ‘no neoplasia at colectomy’: p = 0.002; ‘Carcinoma at colectomy’ versus ‘no neoplasia at colectomy’: p < 0.001.

reference; aHR = 1, 95% CI [0.3–3.4] for 1990–2005; aHR = 0.8, 95% CI [0.1–7.6] after 2005).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we report an overall cumulative incidence of rectal carcinoma at 3.2% at 10 years and at 7.3% at 20 years fol-lowing IRA for UC. Age, IBD duration, PSC, and a prior colonic carcinoma were independently associated with a higher risk. These results were based on a multicenter cohort with a long median fol-low-up of >10 years. Therefore, the high number of reported rec-tal carcinomas [19 events] makes our findings accurate and reliable regarding estimated long-term incidences and risk factors.

Previously reported cumulative incidences are detailed in Table 4. Abdalla et al. recently reported the data from a Swedish nation-wide population-based study. They estimated the cumulative incidences of rectal carcinoma at 1.6% at 10 years and at 5.6% at 20 years after IRA for UC.14 Regarding the estimated incidences accord-ing to IBD duration, in the metaanalysis of Derikx et al. (a pooled analysis of three studies), the long-term estimations of incidence of post-IRA rectal carcinoma were higher than those in our study: 0%, 5% and 10% compared with 0.4%, 3.1% and 7% at 10, 20 and 30 years after IBD diagnosis, respectively.9 In our study, the large number of patients followed for a long period of time may explain that the long-term incidences that we observed were not over-esti-mated, which could be the case in smaller cohorts, particularly with a shorter follow-up. Conversely, our numbers might be overesti-mated compared with population-based studies as our study mainly involved more severe patients followed in tertiary centers. However, our cohort may be able to provide more accurate, deeper insights regarding risk factors.

Regarding the risk of carcinoma following IPAA and as expected, the overall cumulative incidence of pouch carcinoma after IPAA is lower than the risk of rectal carcinoma after IRA. It has been reported by Derikx et al. at 1.4% at 10 years and at 3.3% at 20 years after IPAA confection.15 Interestingly, it was estimated at 0.1% at 10 years and at 0.1% at 20 years in the Swedish population-based study.14 Unfortunately, we couldn’t compare the incidence of rectal cancer following IRA with the incidence of pouch carcinoma following IPAA in a complementary GETAID cohort, as this is currently not available.

Similarly to the risk for colonic carcinoma in the context of inflammatory colitis,5 we determined that age and disease duration at the time of IRA as well as the concomitant presence of PSC were independently associated with the risk of developing rectal carci-noma after IRA for UC. PSC is thus highly associated with the risk of colorectal carcinoma in the context of IBD, before as well as after colectomy. This may also be the case in the context of IPAA.16

It has been stated that endoscopic surveillance is required in the context of IRA for UC.5,17,18 However there are no current guidelines available regarding the recommended frequency. The earliest rectal carcinoma occurred after 9.7 years of IBD duration in our cohort and, similarly to what it is recommended for colon screening in IBD, a rectal endoscopy screening doesn’t seem necessary in the early years of the disease. Conversely, we observed the earliest rectal carcinoma 1 year after the IRA confection, so rectal neoplasia screening might be required even a short time after IRA. A reasonable approach for a screening strategy would be to follow current guidelines regarding colonic screening in IBD i.e. based on IBD duration. The relatively low overall risk of rectal carcinoma in the absence of risk factors

may allow rectal endoscopies to be performed every 2 to 3 years. Table 4

.

Previously repor

ted cumulati

ve incidences of rectal carcinoma following colectom

y and IRA for UC.

Study [First Author , Journal, Y ear of publication] Number of patients Number of rectal carcinomas Follow-up [years] Incidences of rectal carcinoma after IRA Incidences of post IRA rectal carcinoma after IBD diagnosis

10-year incidence 20-year incidence 10-year incidence 20-year incidence 30-year incidence Baker , Br J Surg, 1978 19 374 22 [5.9%] -0% 6% 15% Grundfest, Ann Surg, 1981 20 89 4 [4.8%] 7.7 [mean] 0.5% 0.9% 3.4% da Luz Moreira, Br J Surg, 2010 10 86 7 [8.1%] 11 [median] 2% 14% Andersson, J Crohns Colitis, 2014 21 105 2 [1.9%] 5.4 [mean] 0% 2.1% Abdalla,

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol,

2016 15 1112 20 [1.8%] 8.6 [mean] 1.6% 5.6%

Data from our cohort

343 19 [5.5%] 10.4 [median] 3.2% 7.3% 0.4% 3.1% 7% IBD

, inflammatory bowel diseases; IRA,

ileorectal anastomosis.

However in the presence of risk factors, including PSC and prior colonic neoplasia, a higher frequency of rectal surveillance seems necessary. Nevertheless, either IPAA or end ileostomy should be considered as the preferential approach after colec-tomy for UC in patients presenting such risk factors for colorectal carcinoma.

Unfortunately, we were not able to determine whether other known colonic carcinoma–associated factors for IBD, such as chronic inflammation and the use of treatments, influence the risk of rectal carcinoma after IRA. Additional studies are warranted for assessing these factors in order to determine a more tailored approach for rectal surveillance after UC.

While our study provides informative findings regarding the risk of rectal neoplasias after IRA for UC, some limitations have to be discussed. First, grading of dysplasias and centralized patho-logic examinations have not been performed. As exposed in the Materials and Methods section, the wide period of the study did not allow us to do this. However, we selected a strong primary end point, i.e. rectal carcinoma, and we considered separately colonic dysplasia and colonic carcinoma for the risk factor analysis, which make our findings reliable. Second, data regarding surveillance [i.e. frequency and number of rectal endoscopies] was not avail-able. Additionally, the long follow-up as well as the large number of patients followed in expert IBD centers are strong features of our cohort.

5. Conclusion

Rectal carcinoma may develop at a clinically relevant rate in UC patients with IRA, and this may justify regular endoscopic surveil-lance. The risk of rectal carcinoma is raised by a history of colonic neoplasia, IBD duration, age, and an associated diagnosis of PSC. UC patients with IRA who present one or several of the latter risk factors should be closely monitored for the risk of rectal carcinoma. Moreover, given the high risk of rectal neoplasia, either IPAA or end ileostomy should be viewed as the preferred option after colectomy for patients with PSC and/or prior colonic neoplasia, along with nec-essary endoscopic pouch surveillance.

Funding

None.Conflict of Interest

None related to this work.Acknowledgments

This study was conducted on the behalf of the GETAID and the GETAID chirurgie groups. We would like to thank the following physicians and sur-geons involved in this study: Jean-Louis Dupas, Jean-Marc Regimbeau, Charles Sabbagh [CHU Amiens], Gilles Bommelaer, Anne Dubois [Clermont-Ferrand, CHU Estaing], Yoram Bouhnik, Carmen Stefanescu, Léon Maggiori [Clichy, Hôpital Beaujon], Nicolas de Angelis, Francesco Brunetti [Créteil, Hôpital Henri Mondor], Franck Carbonnel, Stéphane Benoist [Kremlin-Bicêtre], Benjamin Pariente, Philippe Zerbib, Guillaume Piessen [CHRU Lille], Lara Ribeiro [Paris, Hôpital Bichat], Mahaut Leconte, Bertrand Dousset [Paris, Hôpital Cochin], Harry Sokol, Laurent Beaugerie, Jérémie Lefevre, Emmanuel Tiret [Paris, Hôpital Saint-Antoine], Clotilde Baudry, Nicolas Munoz-Bongrand [Paris, Hôpital Saint-Louis], Quentin Denost [Pessac, CHU Bordeaux], Bernard Flourie [Pierre-bénite, CHU Lyon-Sud], Françoise Guillon, Guillaume Pineton de Chambrun, Jean-Michel Fabre [Montpellier].

References

1. Farmer RG, Easley KA, Rankin GB. Clinical patterns, natural history, and progression of ulcerative colitis. A long-term follow-up of 1116 patients.

Dig Dis Sci 1993;38:1137–46.

2. Jess T, Riis L, Vind I, et al. Changes in clinical characteristics, course, and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease during the last 5 decades: a population-based study from Copenhagen, Denmark. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:481–9.

3. Targownik LE, Singh H, Nugent Z, Bernstein CN. The epidemiology of colectomy in ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based cohort.

Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1228–35.

4. Dignass A, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, et al.; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current manage-ment. J Crohns Colitis 2010;4:28–62.

5. Annese V, Beaugerie L, Egan L, et al.; ECCO. European evidence-based consensus: inflammatory bowel disease and malignancies. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:945–65.

6. Øresland T, Bemelman W, Sampietro G, Spinelli A, Windsor A, Tiret E,

et al. European evidence based consensus on surgery for ulcerative colitis. J Crohn’s Colitis 2014:9:4–25.

7. Dignass A, Eliakim R, Magro F, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 1: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis 2012;6:965–90.

8. Myrelid P, Øresland T. A reappraisal of the ileo-rectal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:433–8.

9. Derikx LAAP, Nissen LHC, Smits LJT, Shen B, Hoentjen F. Risk of neoplasia after colectomy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:798–806.e20.

10. da Luz Moreira A, Kiran RP, Lavery I. Clinical outcomes of ileorectal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg 2010;97:65–9.

11. Uzzan M, Cosnes J, Amiot A, Gornet J-M, Seksik P, Cotte E, et al. Long-term follow-up after ileorectal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg 2016;XX:1.

12. Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, et al. The Vienna classification of gas-trointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut 2000;47:251–5.

13. Odze RD, Goldblum J, Noffsinger A, Alsaigh N, Rybicki LA, Fogt F. Interobserver variability in the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis–associated dysplasia by telepathology. Mod Pathol 2002;15:379–86.

14. Abdalla M, Landerholm K, Andersson P, Andersson RE, Myrelid P. Risk of rectal cancer after colectomy for patients with ulcerative colitis—a national cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016, published online Dec 21. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.11.036

15. Derikx LA, Kievit W, Drenth JP, et al.; Dutch Initiative on Crohn and Coli-tis. Prior colorectal neoplasia is associated with increased risk of ileoanal pouch neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Gastroen-terology 2014;146:119–28.e1.

16. Imam MH, Eaton JE, Puckett JS, et al. Neoplasia in the ileoanal pouch fol-lowing colectomy in patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:1294–9.

17. Annese V, Daperno M, Rutter MD, et al.; European Crohn’s and Coli-tis Organisation. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:982–1018. 18. Oresland T, Fasth S, Nordgren S, Hultén L. The clinical and functional

outcome after restorative proctocolectomy. A prospective study in 100 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 1989;4:50–6.

19. Baker WN, Glass RE, Ritchie JK, Aylett SO. Cancer of the rectum follow-ing colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg 1978;65:862–8.

20. Grundfest SF, Fazio V, Weiss RA, et al. The risk of cancer following colec-tomy and ileorectal anastomosis for extensive mucosal ulcerative colitis.

Ann Surg 1981;193:9–14.

21. Andersson P, Norblad R, Söderholm JD, Myrelid P. Ileorectal anastomosis in comparison with ileal pouch anal anastomosis in reconstructive surgery for ulcerative colitis–a single institution experience. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:582–9.