MIT LIBRARIES

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

hb3i

[DEWey

.M415

—

"~—

-Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

AN

ASSESSMENT

OF

THE

PROPOSALS

OF

THE

PRESIDENT'S

COMMISSION

TO

STRENGTHEN

SOCIAL

SECURITY

Peter

Diamond

Peter

Orszag

Working

Paper

02-28

July

2002

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02

142

This

paper can

be

downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection

at

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

AN

ASSESSMENT OF

THE PROPOSALS

OF

THE

PRESIDENT'S

COMMISSION

TO

STRENGTHEN

SOCIAL

SECURITY

Peter

piamond

Peter

Orszag

Working

Paper

02-28

July

2002

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network

Paper

Collection

at

http://papers.ssm.com/abstract=322040

AUG

2

An

Assessment

of the

Proposals

of

the President's

Commission

to

Strengthen

Social

Security

July

2002

PeterA.

Diamond

InstituteProfessor

and

ProfessorofEconomics

MIT

Department

ofEconomics

E52-344

50 Memorial

DriveCambridge

MA

02142-1347

pdiamond@mit.edu

Peter R.

Orszag

Joseph A.

Pechman

Senior FellowEconomic

StudiesThe

Brookings Institution1775 Mass.

Ave

NW

Washington,

DC

20036

porszag@brookings.edu

An

Assessment

oftheProposals ofthe President's

Commission

toStrengthen

Social SecurityPeterA.

Diamond

and

Peter R.Orszag

July

2002

Abstract

The

President'sCommission

to Strengthen Social Securityproposed

three reform plans.Two,

analyzed here, restore actuarial balancein the absence ofindividual accounts.One

achieves this balance solely through benefit reductions.

The

other usesnew

dedicated revenue to cover one-third ofthe actuarial deficit, reducing benefits to close the rest.Both

plans cut disability andyoung

survivor benefits in step with retirement benefits,while bolstering benefits for long-career

low

earnersand

surviving spouses withlow

benefits.

The

plansboth include voluntary individual accounts that replace partofthe scaled-back Social Security system. Payroll taxes are diverted to the accountsand

one of the plansalsorequires a (subsidized) add-oncontribution forthosechoosingaccounts.

Under

both models,any

payroll tax deposited in anindividual account is also recorded in a "liabilityaccount" for the worker.

The

liability account tracks the diverted payroll revenue (withinterest)

and

is paid offby

reducing traditional benefits.The

individual accounts aresubsidized through a sub-market interest rate on the liability accounts. This subsidy

worsens

the financial position of the Trust Fund.The

accounts also create a cash-flow problem. Consequently,by

themselves, the individual accountsmake

Social Security's solvencyproblems

worse

both inthe shortrunand

overthe longrun.To

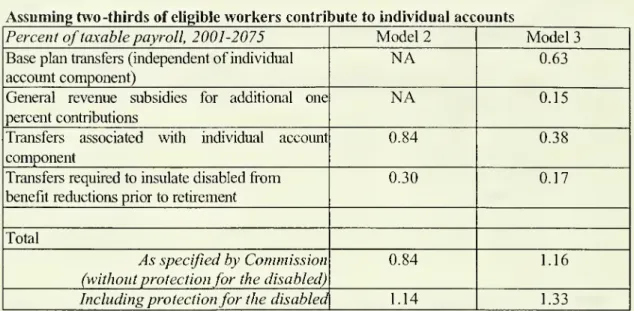

offset the adverse impact ofthe accounts, theplans call for large transfers ofgeneralrevenues (despite substantial projected budget deficits). If all (two-thirds of) eligible

workers opted forthe accounts, the

new

revenues required over the next 75 yearswould

amount

tobetween

1.2and

1.5 (0.8and

1.1) percent of payroll.Holding

the disabled harmlessfrom

the benefit reductionswould

raise the required transfers tobetween

1.5and 1.7 (1.1 and 1.3) percent ofpayroll

(compared

to a projected actuarial deficit of 1.9relative to paying scheduled benefits, the plans

would

produce significant reductions inexpected

combined

benefits.At

the end of 75 years, however, assets in the accountswould

amount

tobetween

53and 66

(35and

44)percentofGDP,

and

the value to Social Security of the accumulated liabilities that reduce later benefitswould

amount

tomore

An

Assessment

ofthe Proposals ofthePresident's

Commission

toStrengthen

Social SecurityPeterA.

Diamond

and

Peter R.Orszag

1July,

2002

Social Security isrunning short-term surplusesbut faces a long-term actuarialimbalance.

According

to theintermediate costprojections containedin the2002 Annual

Report ofthe Social Security Trustees, the projected imbalance over the next 75 yearsamounts

to 1.87 percent of taxable payroll.2 In other words, an increase in the payroll tax rate of 1.87 percentage points (.935 each foremployer

and employee)

starting in2003

would

beneeded

to balance projected revenuesand

outlays over the 75-year horizon traditionally used toexamine

the financialpositionofSocial Security.

Moreover,

the Trustees' Reportprojected that theTrustFund

would

be

exhausted (reach zero) in 2041, atwhich

pointincoming

revenuewould

be sufficient tofinance only about 75percent

of

scheduledbenefits.3Social Security's long-term actuarial imbalance,

combined

with a desireby

some

tointroduce individual accounts into the program, has sparked interest in reform over the past several years.4 Indeed, Social Security figured prominently in the

2000

presidential campaign. Followingthe election, PresidentBush

appointed acommission

—

thePresident'sCommission

toStrengthen Social Security

—

withtwo

chargesand

several constraints.One

was

to find away

to1

We

thank Greg Anrig, Barry Bosworth, Robert Cumby, William Gale, Stephen Goss,Robert Greenstein, KiloloKijakazi, Alicia Munnell, Richard Leone, Jeffrey Liebman, Michael Orszag, Jim Poterba, Wendell Primus, and

Bernard

Wasow

forhelpfulcommentsand/or discussions. Theviews expressedhere are thoseoftheauthorsaloneand donot necessarily represent those ofthestaff,trustees,orofficersoftheinstitutionswithwhichthe authors are

affiliated. Fora lesstechnicalversionof ouranalysis,seePeterDiamondandPeterOrszag,"ReducingBenefitsand

SubsidizingIndividualAccounts:

An

Analysis ofthePlans Proposed by thePresident'sCommission to StrengthenSocial Security,"TheCentury FoundationandtheCenteron BudgetandPolicyPriorities,June 18,2002.

See2002AnnualReport oftheBoardofTi-usteesoftheFederalOld-Age andSurvivorsInsuranceandDisability

Insurance TrustFunds. The actuarial imbalance figure reflects theintermediate cost projections and includes the

cost ofensuring that theTrust Fund at the end ofthe evaluation period is equal to oneyear's expenditures. The

imbalanceamountsto0.7percentof

GDP

overthenext75years.Theevaluationbythe OfficeoftheChief ActuaryatSocialSecurityoftheCommission'sproposalswerebased on

the intermediate cost assumptions used in the 2001 report ratherthan the 2002 report. The 2001 assumptions

produceda75-yearactuarial imbalance of1.86percentofpayrolland aprojected dateofTrust Fundexhaustion of 2038.

restore "financial soundness" to the system.

The

secondwas

to design a system ofvoluntary individual accounts.(Box

1 provides the precisewording

of the charge to theCommission.)

After deliberating for approximately eight months, theCommission

issued a final report inDecember

2001

thatcontainedthree differentproposals.5One

ofthe threeCommission

proposals(Model

1)would

notrestorelong-term balancetoSocial Security

and

is therefore not considered inmuch

detail here.The

othertwo

models

substantially reduce traditional Social Security benefits in order to

improve

the system'slong-term balance. Indeed, these

two models

achieve actuarial balance in the absence of theirindividual accountproposals.

The

models

also create individualaccounts thatreplacepart ofthescaled-back Social Security system.

By

themselves,the accountsworsen

Social Security'slong-term actuarial balance because of subsidies provided to workers opting for the accounts.

The

accounts also create a cash-flow

problem

sincerevenues are divertedaway

from

Social Security decadesbefore benefits arereducedas a resultoftheaccounts.To

deal with the deterioration in Social Security's finances generatedby

the individual accounts,Models

2 and 3 call for significant infusions ofgeneral revenue into Social Security.Given

the dramatic deterioration in the nation's fiscal outlook, however, simplyassuming

theavailability of large transfers, without specifying other changes in the Federal budget to

accommodate

suchtransfers,would

appeartobe problematic.The

purpose of this paper is to describe and assess the proposals included in theCommission's

final report. Before turning to the analysis, one issue is worth highlighting: the baseline againstwhich

theproposedbenefitsare compared. Indescribing bothbenefit levelsand

fiscal implications,

we

initiallycompare

the proposals to "scheduled benefits,"which

are thosegiven

by

the current benefit formula withoutmaking any

adjustment for the current level ofactuarialimbalance. Thisbaselinehas

some

advantages. First,the current benefitformula has aninherent

economic

logic: it maintains replacement ratesfrom

one generation to the next forForahistoryofthereform debateduringthe 1990s, seeDouglasW. Elmendorf,JeffreyB. Liebman,andDavidW.

Wilcox, "Fiscal Policy and Social Security Policy During the 1990s," inJeffrey A. Frankel and Peter R. Orszag,

workers with the

same

earningsrelative to the averagewage

(oncethenormal

retirementage hasstabilized). Second, since it is

embodied

in legislation, the current benefit formula isunambiguous and

does not require assumptions abouthow

benefits might be adjusted in thefuture.

The

major

limitation of using scheduled benefits as the baseline,however,

is that SocialSecurity

would

not be able topay

these scheduled benefits without additional revenue. Inparticular, paying scheduledbenefits

would

require additional financing equal to 1.87 percent oftaxable payroll over the next 75 years. Despite this long-term financing gap,

we

use scheduled benefits as the baseline in our initial analysis.We

note that this treatmentconforms

to the approach to evaluating Social Security reforms adoptedby

theGreenspan

Commission

in 1983and

theAdvisory

Council in 1994-1996, bothofwhich used

the scheduledbenefit formula as the baseline despite projected long-term deficits in Social Security. Importantly,by

using a single baseline throughout the initial analysis,we

describe not only benefit levels but also fiscalimplications relative to the

same

standard.7 Thisremoves

the temptation to focus attentionon

differentbaselines for differentimplicationsofa proposal.8

5

A

revisedfinalreportwas issuedinMarch 2002. All page numbersand referencesin this documentrefer to the

March2002versionoftheReport.

6

The Commission used three baselines, scheduled benefits, payable benefits, and real benefits paid to current

retirees. "Payablebenefits" are defined as the benefits thatcouldbe financed by projected revenues undercurrent

law, assumingnochangeinrevenuesor benefitsuntil theTrustFundis exhausted, followedbya cutin benefitsso

that annual benefits equal annual revenues.

Two

problemsarise with regard to this alternative baseline. First, thepattern ofbenefits is complex, making it harder to follow the implications ofthe proposals. Second, thepayable

benefitbaselinemaybe evenlessplausiblepoliticallythan thescheduledbenefit baseline. AsChairman Greenspan

has emphasized, the pattern ofno action followedby such sharp benefit cuts embodied in the "payablebenefits"

baseline simply will nothappen. (Alan Greenspan, "Saving for Retirement," Remarks before the 2002 National

SummitonRetirementSavings, theDepartmentof Labor, Washington, D.C.,February28,2002.) The Commission

arguesagainst useofthe scheduled benefitbaselinebecause "confusion occasionally arises when comparisons are

made between two different plans that employ different levels of tax revenue." (President's Commission to

Strengthen Social Security, Strengthening SocialSecurityand CreatingPersonal Wealth forAllAmericans, page

35.)

We

recognizethatsuch confusion canarise.We

note,however,thattheCommission'splans involve substantialamounts ofgeneral revenue transfers. The "payable benefits" baseline, on the other hand, involves no general

revenuetransfersbydefinition, sinceSocial Security benefitsare always maintained atthe level ofSocial Security

revenue. The Commission's comparison ofthe benefits under its plans to the "payable benefits" baseline thus

violates its own warning against comparing plans with different levels ofassumed tax revenue. Indeed, ifone

wantedtocompare plansto a baselinewith thesamelevel ofassumed general revenue, Models 2 and3 would be

moreappropriately compared tothescheduledbenefitbaseline than thepayablebenefit baseline, because the level

ofgeneral revenuetransfers underModels 2 and 3overthenext 75 years aremuch closerto the level oftransfers

requiredtofinancescheduledbenefitsthantozero.

In particular,usingscheduledbenefitsasthebaselineforcomparingrevenueinfusions, butpayablebenefitsas the

baseline for benefit comparisons, could easily create confusion. For example, Model 2's combined benefits are

lowerthan scheduledbenefits,but Model 2's actuarial deficit (absentgeneral revenuetransfers) is also lowerthan

with scheduledbenefits. At thesame time, Model 2's combined benefits are less than payable benefits until the

TrustFundisexhausted andthen eventually larger thanpayablebenefits. Sincepayablebenefits,bydefinition,need

Use

of scheduledbenefitsas the initial baseline in thisanalysis, however, is notmeant

toimply inany

way

thatreforms tothe currentsystem areunnecessary. Indeed,we

favor restoringactuarial balance with legislation in the near future that slowly phases in a combination of

changes tothe Social Security system, including adjustments toboth revenues

and

benefits. It isalso importantto

emphasize

thatwe

examine

the effectsofalternative baselines in a latersection ofthe paper,where

we

provide informationon two

alternative baselines that achieve 75-year solvency with thesame

level ofgeneralrevenuetransfers asModel

2.To

examine

the effects of theCommission's

proposals, Section I begins with the proposed changes in the determination and financing of traditional Social Security benefits.Examining

these changes totraditional benefits is importantas a buildingblock in understandingthe overall effects ofthe proposals,

and

is crucially important in understanding the effects forworkers

who

choose not to contribute to the individual accounts. Section II thenexamines

thestructure of the individual accounts proposed

by

theCommission.

Section III presents thecombined

effects of the individual accountsand

the changes to the traditionalcomponent

of Social Security in terms of assets, cash flows, actuarial imbalance, andmonthly

benefits forworkerswith differentearnings levels.9 Section

IV

offerssome

conclusions.I.

Changes

inScheduled

BenefitsThe

Commission

referredtoitsthreeproposalsas "reform models."The

first contains an individual account plan withoutany

changes to the traditional system,and

therefore is not described in this section (since there is nothing to explain about its impacton

scheduledbenefits)andlessdemandongeneralrevenues(thanscheduledbenefits),while anopponent canassert thatModel2

offers lower benefits (than scheduled benefits) and makes a greater demand on general revenues (than payable

benefits). Both statements areliterally accurateand both havethe potential tomislead. Using asinglebaseline is

moretransparentand lesslikely tocause confusion.

To seethe roleofmultiple baselinesintheCommission Report,consider the discussionofModel 2onpages 121

to 129.

When

discussingbenefits,scheduled benefitsarebyand large ignored, appearing only in a footnotein thetable on page 122.

When

discussing financing, only scheduled benefits are discussed. Furthermore, the term"currentlaw"isusedtorefer topayablebenefitsin thetableonbenefitsonpage 122 andtoscheduledbenefitsinthe

figuresonfinancingon pages 125 and 126.

We

donot exploretheimportantissueoftheimpactoftheplansonnational saving. Forapreliminary analysisofthat topic, see Barry Bosworth and Gary Burtless, "Economic and Distributional Effects of the Proposals of

benefits).

The

secondand

third proposals contain changes to the traditional Social Security systemthatwould

restore actuarialbalance in theabsenceofthe individual accountcomponent.

A.

Model

2Proposals for Traditional Benefitsand

theirFinancing

The

future benefit reductions inModel

2 are sufficient to restore actuarial balance toSocial Security with

no

new

sources ofrevenue, while also financingtwo modest

expansions inbenefits for

needy

groups.The

plan accomplishes this objectiveby

changingfrom

the currentwage-indexed

system fordetermining initial benefits atretirement to one that uses a price indexas partofthe determinationofinitialbenefits.

Under

current law, initial retirement benefits are basedon

a worker's average indexedmonthly

earnings(AIME).

AIME,

in turn,is determinedby

takingearnings inpreviousyearsand

scaling

them

up by

subsequent national averagewage

growth.10The

"bend

points" of the formula relating full benefits (the so-calledPrimary

InsuranceAmount)

to earnings are also indexedtoaverage earnings.''Under

this approach, the benefitsystemis designed tomaintainaconstant replacement rate across generations

-

that is, the full retirement benefit as a share of pre-retirement earnings is constant over time for successive cohorts ofworkers

with thesame

earnings relative toaverage earnings.

A

constantreplacement rate across generationsmay

seem

like an abstract concept, but itserves the crucial purpose of allowing beneficiaries to share in the general increase in the

standard-of-livingthat society as a

whole

experiencesfrom one

generation to the next.A

focuson

replacement rates also recognizes the psychologicalphenomenon

by which

familiesbecome

accustomed

to a given level of consumption; substantial declines inincome

during retirement can pose difficultadjustment problems.Moreprecisely, thewage indexing occurs throughtheyearinwhichaworkerturns60. Theinitial benefitlevelis

thusindexed towage growth.After initially claimingbenefits, benefitincreases areindexed topricegrowth. Price

indexing ofbenefitsbeginsaftertheyearinwhicha workerturns62. Thus there isagap withnoindexing,which

The Commission's

proposalwould

alter the current system so that in determining theinitial benefit level, benefits

would keep

pace with price growth, notwage

growth.More

precisely, theproposal

would

multiply the 90 percent, 32 percentand

15 percent factors usedtocompute

the Primary InsuranceAmount

by

the ratio of cumulative price growth to cumulativewage

growthbetween 2008 and

the year inwhich

aworker

becomes

entitled to claim benefits.This approach leads to real benefit levels that are constant over time, rather than increasing in line with real wages. Since real

wage

growth is positive on average, the changewould

reduceinitial benefitlevels

and

the size ofthe reductionwould

increase overtime.The

latest Trustee'sReportprojects long-run growth ofprices of3.0percent peryear and long-run growth oftaxable

wages

of4.1 percent per year.Over

10 years, cumulative pricegrowth

is then90

percent ofwage

growth; over20

years, 81 percent; over40

years,65 percent.1The

implications of the proposedchange

on

benefit levels are dramatic.One

of the President's charges to theCommission was

to preserve the level ofbenefits for retirees and forthose nearing retirement.

The Commission

interpretedthat chargeas applyingtoworkers age 55 and over on January 1, 2002.Under

Model

2, the reductions in benefitswould

thereforebe

phased in startingwith workers

who

were

54 at the beginning of 2002. For each additional yearthat a

worker

isyounger

than 55, thebenefit formula is projected to be reducedby

an additional one percent (approximately-

one

percentis theassumed

ultimaterealwage

growth forthe2001

" In 2002, thePrimary Insurance Amount is equalto 90 percent ofthefirst $592 of

AIME;

32 percentofAIME

over$592and through$3,567; and 15percentof

AIME

over$3,567.The "bendpoints"atwhich the90,32,and 15percentfactorsapplyareindexedtowagegrowth.

12

Theprincipleofprice indexingwassupportedbyapanel on whichDiamondservedin 1974-5(Panel onSocial

SecurityFinancingconsultingtoU.S. Senate Finance Committee). Atthe time,thatprincipleseemedappropriate

since the magnitude ofthe actuarial imbalancewas so severe that itwas difficult to see how Congress would

legislate sufficient benefit reductionsand/orrevenue increases to restore solvency to the system whileretaining

wage indexation. The severity ofthe projected imbalance at that time was underscored by the fact that the

subsequent 1977 legislation was followed very shortly after by the 1983 legislation. According to the 1975

Trustees' Report, the actuarial deficit was 5.32 percent of payroll and the Trust Fund was projected to be

exhausted in fiveyears.

By

1976, the actuarial deficit was up to 7.96 percent, with aslightly later projectedexhaustion. By contrast, the actuarial imbalance is

now

1.87 percentofpayroll and theprojected dateoftrustfund exhaustion is nearly four decades away. Since the financial situationnow is far less severe, a dramatic

alteration in the system is neither needed nor desired. Furthermore, the type ofprice indexingadopted by the

Commission in Model 2 is more severe than the approach proposed by the 1974-5 panel on which Diamond

served. The1974-5panelproposed indexing bothAverageIndexedMonthlyEarningsandthebendpointstoprice

inflation rather than wage growth; that approachwould still allow realbenefit increasesovertime.

By

contrast, theCommission proposal maintainsaconstant realbenefit level. Forfurtherdetailon thealternativeapproaches,see Stephen C. Goss, "Long-Range

OASDI

Financial Effects of a Proposal to CPI-Index Benefits AcrossTrustees' intermediate cost projections, with slightly different

growth

rates in the first ten yearsofthe projection).13

With

these reductionscompounding,

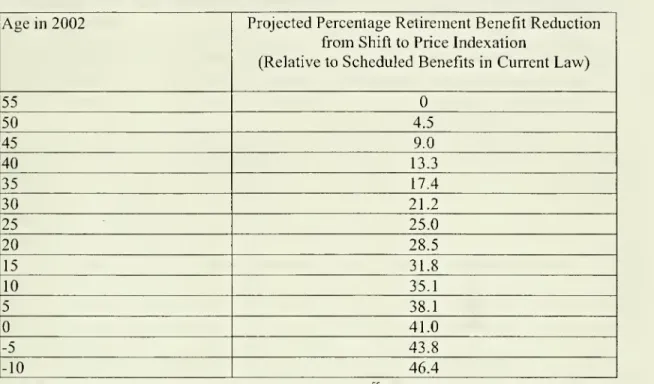

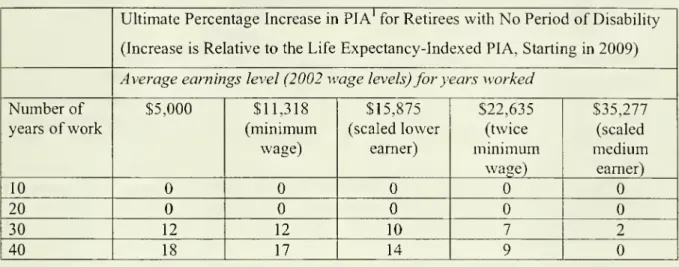

the patternshown

in Table 1 emerges.Thus

a current 35-year oldwould

have

benefits reducedby

17.4 percent under the proposalcompared

to scheduledbenefits under current legislation.The

future benefit level foranewborn

in

2002

would

be reducedby

41.0percentrelative tothe scheduledbenefitlevel.14

The

replacement ratesfrom

Social Securitywould

be reduced'by

corresponding percentages.Under

current law, for example, Social Security is scheduled to replace slightlymore

than36

percent of former earnings forsingle workers with average earnings retiringatage65 in

2025

or thereafter (or equivalently two-earner couples with thesame

earnings each).15Under

Model

2, the replacement ratewould

fall to30

percent for a current 35-year-oldand

to22 percent foranewborn

in2002.The

roleof

the Social Security systemin allowing the elderlytomaintain theirstandard ofliving afterretirement

would

thusdeclinesharplyovertime.The

proposedchange

in the indexation system ismore

than sufficient,by

itself, toeliminate the 75-year actuarial imbalance in Social Security.

We

discuss actuarialbalanceissuesin

more

detail below.Disability

and

Young

SurvivorBenefitsThe

same

benefit formula that is used for retirement benefits is also used for disabilitybenefits.

Thus

the switch to price indexationmeans

that aworker

becoming

entitled todisabilitybenefits in

2020

would

have

disability benefits reducedby

10.7 percent; aworker becoming

entitled in

2040 would have

disability benefitsreducedby

26.4 percent;and

aworker becoming

13

TheTrustees' Report makesyear-by-yearassumptions for 10 yearsand then usesan ultimate assumption of1.0

percent peryearrealwagegrowth fortheremainingyearsto the projection horizon. Inthe2002 Trustees' Report,

theultimaterateof growth ofrealwagesistakentobe 1.1 percent.

Within the traditional 75-year horizon, the largest reduction in retirement benefits would occur for a worker

reaching age 62 in 75 years.

Of

course, such aworker is not yet alive. For such a future worker, the reductionwouldbe almost 50percent. Thereductionsrelative toscheduledbenefitswouldbesomewhatlargerunderthe2002

Trusteesassumptions, becausetheassumedrealwagegrowthrate ishigher thanunderthe2001 assumptions. Under

the2002assumptions, forexample,shifting topriceindexingwouldreducebenefitsfora newbornin 2002 by44.1

percent(comparedto41.0percentunderthe2001 assumptions).

The replacement rates at age 65 are higher but declining during the period that the normal retirement age is

entitled in

2075

would have

disability benefits reducedby

47.5 percent (see Table 2). Yet,many

disabled workers

would have

little opportunity to accumulate substantial balances in theirindividual accounts to offset these benefit reductions

- and

in any case, theywould

notbe

allowedaccesstotheirindividualaccount balancespriortoretirement age.

Since,

on

average, disabled beneficiaries are financially poorlyoff, the proposed changes represent a large reduction in benefits for aneedy

group.16 Furthermore, minorities,on

average, have higher rates of disability than the rest of the populationand

therefore disproportionately benefitfrom

the disability benefits that Social Security provides. For example, Social Security datashow

that 1.1 percentof black workersaged

50-59became

disabled in 1997, relative to 0.6 percent of all workers.17 Blacks account for 13 percent ofworking-age

Americans, but 17 percent of disabledworker

beneficiaries.The

reductions in disability benefitswould

thusio

disproportionately

harm

minorities.The Commission was

aware

of these issuesand

stated explicitly thatsome

other groupneeded

toexamine

disability benefitsand

that "the calculations carried out for thecommission

and

included in this reportassume

that defined benefits willbe

changed

in similarways

for thetwo programs

[OASI

and

DI]. Thisshould

not be taken asa Commission recommendation

for policy implementation.^9 Nonetheless, theCommission

dedicatedno

revenue to financing aFordataonthecircumstancesofthe disabled,see, forexample,VirginiaReno, JerryMashaw,andBillGradison,

eds., Disability: Challenges for Social Insurance, Health Care Financing, and Labor Market Policy (National

AcademyofSocial Insurance: 1997).

Office ofPolicy, Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics, Social Security Administration, "Earnings of

Black and Nonblack Workers:

Who

Died orBecameDisabled in 1996 and 1997?" Note No. 2000-01, November2000.

18

A

final pointaboutdisabilitybenefits isworthnoting. Thereduction in disabilitybenefitsrelative to scheduledbenefits from the shift to price indexation would depend on the worker's year of disability, not the year of

entitlementtoretirementbenefits. Thusa20-year-oldworkerin2002

who

claimeddisabilitybenefitsatage40(in2022)wouldexperienceareductionindisabilitybenefitsof12 percentrelative toscheduledbenefit levels-andthat

real benefit levelwould continueafterthe worker reached retirement age. If thatworker continued workinguntil

retirement,however,thereductioninbenefitswould amountto30percent. Entitlementtodisabilitybenefitswould

effectively lock inasmaller benefit reduction(relative toscheduledbenefits)than entitlementtoretirementbenefits.

It isworthnoting,however, thatthereallevelofbenefits(asopposedtothereductionrelative toscheduledbenefits)

wouldbethesameforthedisabled beneficiaryandtheretiredbeneficiary.

The Commission Report states: "DI beneficiaries may not have their full adult lives in which to accumulate a

retirement account, so this is a rationale for maintaining their traditional benefits. However, ifbenefits were

changed for

OASI

but not DI, thismightleadto anincreaseinDI applicants. The Commission urges theCongressto consider the full range ofoptions available for addressing these concerns. In the absence offully developed

proposals, thecalculations carried out forthe commission and included in this report assumethat definedbenefits

will bechangedin similarways forthetwoprograms. Thisshouldnot betaken asa Commission recommendation

more

modest

reduction in disability benefits. Instead, it included dramatic benefit cuts for thedisabled as part of the solution to restoring actuarial balance.

The

reductions in disabilitybenefits included in

Model

2improve

solvencyby

roughly 0.3 percent ofpayroll over the next75 years.20

Without

these large savings,Model

2would

notachieve long-termbalance.Similarly, Social Security also provides benefits to the

young

children ofworkerswho

die (as well as the children of workers

who

become

disabled).The

reduction in the scheduledbenefit formula, described above, has the

same

proportional impacton

benefits foryoung

children as it does

on

disabled workers. Thus, the benefit for surviving childrenwhose

parent died in2020

would

be reducedby

10.7 percent;and

the benefit for a surviving child in2075

would

be reducedby

47.5 percent relative to scheduled benefit levels. African-American childrenwould

be disproportionately affectedby

these benefit reductions; they currentlyconstitute 15 percent of

Americans

under age 18 butmore

than22

percent of the childrenreceiving Social Security survivorbenefits.

As

with disability benefits, the presence of an individual accountwould

notdo

much

tomitigate the benefit reductions for

young

survivors. First,many

workerswould

nothave

time toaccumulate

much

in an individual accountbefore anearly death. Second, ifthe worker's spouseis alive, the account (and the benefit offset

from

the account)would

be available to the spouseonlyafterthe spouseretires,

and

sonotbe available (atleast immediately)forthechildren.forpolicy implementation" StrengtheningSocial SecurityandCreatingPersonal Wealth forAllAmericans,page

149(italicsinoriginal).

"°The

shift to price indexing under Model 2 reduces total benefits (retirement, survivor, and disability) by 2.07

percent ofpayroll overthe next75 years, which is 13.4 percent of scheduledbenefits over thatperiod (underthe

2001 Trustees' intermediate assumptions). Disability benefits aloneamount to 2.23percent ofpayroll. Assuming

that price indexing affects disability benefits proportionately to retirement and otherbenefits, the impact ofthe

disabilityreductionswouldbe 13.4percentof2.23 percent, or0.3percentofpayroll. This estimatedoesnot include theeffects on young survivors, nordoes it include the benefit reductions forthedisabled after theirconversion to

retirement benefitsatthenormal retirement age. FortheDI componentitself,theproportionalityassumptionmay

underestimate the impact on DI because thebenefit reduction depends on the yearofeligibility for benefits, and

meanduration since benefiteligibilityis lowerfor disabilitybeneficiariesthan for retiredworkerbeneficiaries (both

because ofrelativelyhighmortalityrates forDIbeneficiariesand because oftheconversion ofdisabilitybenefits to

retirement benefitsatthenormalretirementage).

On

theotherhand,theDIcostrateincreasesmoreslowlythantheOASI

costrateduring the75-yearprojection period: Underthe2001 assumptions,theDI costrate wasexpectedtorise from 1.45 percent ofpayroll in 2001 to 2.57 percent ofpayroll in 2075, whereas the

OASI

cost rate wasexpectedto rise from9.04percent ofpayroll in2001 to 16.82percentofpayrollin2075. The75-yearcostrate for

DI is thussomewhat more front-loaded thanthe 75-yearcostrateforOASI, which wouldcausetheproportionality

assumption to overestimate the impact on DI (since the benefit reductions are larger for later years of initial

Long-Career

Low

EarnersFor

many

families, living standards in retirement are considerablybelow

those enjoyedbefore retirement. Social Security-is supposed to mitigate the drop in living standards for

families

who

have

not saved sufficientlyon

theirown.

Concern

about the potential declines inliving standards

upon

retirement is a reason for focusingon

replacement rates at all earningslevels.

But

the issue is ofparticularconcern with regardtolow

earners, since a decline in theirincome

could threaten the ability to secure basic necessities. This concern motivates proposalstoraise Social Security benefits for

low

earners.A

complication intryingto targetbenefit increaseson

thosewho

areneedy

is that retiredworker

benefits are basedon

a worker's earnings record; the system for determining benefitsdoes not fully reflect family circumstances.

The

Supplemental SecurityIncome

(SSI)program

does take intoconsideration family circumstances

and

puts a floorunder

the living standards of those age 65and

older, but themaximum

benefit level under SSI isbelow

the official povertyline.21

More

pressingin the context ofalong-termprogram

such as Social Security, theofficialpovertyline increasesonly with inflation, resulting in apoverty linethat falls further

and

furtherbehind averageearnings over time(given positivereal

wage

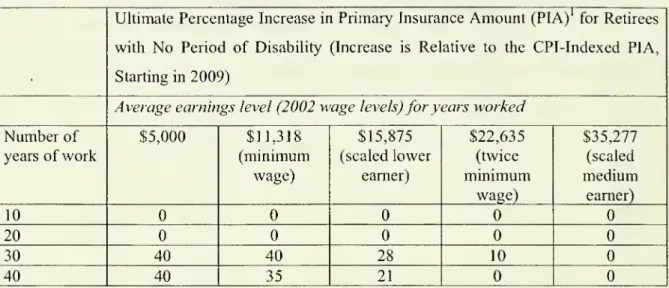

growth).The Commission

has recognized these issues and proposed to usesome

ofthe revenue savedby

the benefit reductions described above to raise benefits for workers withlow

earningswho

have had

earnings in at least 20 years.The

details ofthe proposal areshown

in Table 3.The maximal

percentage increase of40

percent is not sufficient to offset the reduction intraditional benefits

from

price indexing for workersyounger

than 20.22 Unfortunately, the21

The

maximum

federal SSIbenefit, $545permonth foranindividualand $817 foracouplein2002. Theofficialpoverty thresholdforanelderlycouple in2001 was$10,705,or$892permonth. The figurefor2002islikely tobe

approximately$920 permonth.

Many

analysts, furthermore, believe theofficial povertythreshold is too low. Forfurtherdiscussionoftheproblems withthe officialpovertythreshold,seeConstanceF.Citroand RobertT. Michael,

ed.,MeasuringPoverty:A

New

Approach (NationalAcademyPress: 1995). SomestatessupplementthefederalSSIpayment,buttheamountsvarybystate.

Workers

who

are youngerthan 20experiencemorethan a 28.6percent declineintheirPIA,which is thecriticalthreshold for determining whether benefits are higher orlower than under the current benefit formula. (Solving

Commission

did notprovide a detailed analysisof

the impact ofthis proposalon

the distributionof

income

levels.But

regardless of the precise effects, the existence of the proposal underscorestheCommission's

validconcern aboutthe plightoflowerearners in retirement.Widows

andWidowers

Just as Social Security isdesignedto mitigate a declinein living standards

when

aworker

is disabled or retires, so too it is designed to mitigate a drop in living standards of family

members

when

aworker

orretiree dies. Social Security provides benefits tothe elderly spouses of deceased workers. It also provides benefits to theyoung

children ofworkerswho

die, as discussed above.Although

theCommission

did not address issues raisedby

the deaths of workers withyoung

children, it didmake

a proposal for thewidows

and

widowers

ofretiredworkers.

Under

current law, the survivor receives a benefit equal tobetween 50

percentand

67 percent ofthecombined

benefits ofthe couple before the death.The Commission

proposes instead that in the event of the death of aworker

after retirement, the benefit ofthe surviving spousewould

be at least as large as 75 percent ofthecombined

benefits ofhusband and

wife before the death.25However,

this provisionwould

be limited to benefit increases that did notraisethe benefit level

above

the averagePIA

ofretiredworkers. InDecember

2000, theaveragePIA

of retired workerswas

$851,which

would

correspond to an annual benefit of$10,214

if1.4x=1.0givesx=.714,which implies a28.6 percent declineinPIA. Forlong-careerlow-incomeworkers younger

than 20,thespecificbenefitexpansionisthereforemorethanoffsetbythe general reductioninbenefitsunderModel

2.)

Theimpact ofthe proposal, whileprogressive, would appeartobe relativelymodest. Overthe 75-yearhorizon,

for example, its cost amounts to roughly 6.5 percent of the cost savings from the shift to price indexation for

determininginitialbenefits. Furthermore,theproposalisdefined intermsofapercentage ofthePrimary Insurance

Amount (PIA), which is the benefit level received by a worker claiming benefits at theNormal Retirement Age (NRA). Thus the annual costofthe proposal gets steadily smaller relative to the annual cost savings fromprice

indexing(since priceindexing reducesthePIAby increasingamounts,which alsoreducesthecostoftheexpanded

benefit).

The survivor's benefit is reduced ifthe survivor claims it before the normal retirement age, and can also be

reduced iftheprimaryworker had claimed benefits before the normal retirement age (or increased iftheprimary

workerhad claimed benefits after the normal retirement age). For further discussion, see David Weaver, "The

Widow(er)'s LimitProvisionofSocial Security,"SocialSecurityBulletin,Vol. 64,No. 1,2001/2002, pages 1-15.

benefits

were

claimed at thenormal

retirement age.26Even

with this increase in survivorbenefits relative to

worker and

spouse benefits, the steady declinefrom

price indexation inworker

and spousal traditional benefitswould

eventually be larger than the increasefrom

thisadjustment.

Thus

widow

andwidower

benefitswould

eventuallybe lowerthan those scheduledincurrentlaw.

Analysts ofSocial Security have longbeen concerned about the drop in living standards ofthe surviving spouse

upon

the death ofa retired worker. Indeed, survivingwidows

typicallysuffer a 30 percentdrop in living standards(income relative to a

measure

ofneeds).27Moreover,

although the poverty rates for elderly married couples are approximately 5 percent, the poverty

rates forelderly

widows

aremore

than three times as large.Basing

the benefits ofa survivoron

the benefits thathad been

receivedby

the couple is a sensible approach to theproblem

of29

trying tomaintainliving standards.

ActuarialBalance

The

reduction in retirement, survivor, and disability benefitsfrom

the change to price indexing,combined

with themodest

increases inbenefits for long-careerlow

earnersand

some

widows

and widowers

withlow

benefits, produces the impacton

actuarial balanceshown

inTable 4.

The

shift to price indexing reduces benefitsby

somuch

that it is possible to devote a26

The PIA figure is taken from Table 5.CI of the draft Annual Statistical Supplement 2001, available at

http://www.ssa.gov/statistics/Supplement/2001/index.htmI.

11

Karen Holden and Cathleen Zick, "Insuring against the Consequences ofWidowhood in a Reformed Social

Security System," in R. Douglas Arnold, Michael J. Graetz, and AliciaH. Munnell, FramingtheSocial Security

Debate: Values,Politics,andEconomics(NationalAcademyofSocial Insurance: 1998),pages 157-181.

28

Melissa M. Favreault,Frank J. Sammartino, and C. Eugene Steuerle, "Social Security Benefitsfor Spouses and

Survivors," in Melissa M. Favreault, Frank J. Sammartino, and C. Eugene Steuerle, eds., Social Security andthe

Family(UrbanInstitutePress:2002),Table6.1,page 183. 29

AlthoughtheBush Commission'sproposalisa step intherightdirection, restrictingittolow-benefit survivorsis

unduly restrictive. Indeed, the cost ofthis proposal is only fourpercent ofthecost savings from thereduction in

benefitsfrompriceindexing. Previousproposals,forexampleby Burkhauser and Smeeding,wouldnothavelimited

the survivor benefit expansion to those with low benefits. In particular, Burkhauser and Smeeding proposed an

increase in survivor benefits for all elderly survivors, and suggested financing this increase by reducing spousal

benefits,thereby tendingto transferbenefitsfromthetimewhenbothhusbandand wifewerealive tothetimewhen

just one was. (See Richard Burkhauser and Timothy Smeeding, "Social Security Reform:

A

Budget-NeutralApproach to Older Women's Disproportionate Risk ofPoverty," Center for Policy Research, Maxwell School,

SyracuseUniversity, 1994.) TheGramlichplanfromthe 1994-1996 Advisory Council proposedasimilarapproach.

"Option II: Publicly-Held Individual Accounts," Report ofthe 1994-1996Advisory Council on Social Security,

VolumeI: Findings andRecommendations,pages28-29.

tenth ofthecost savings to increased benefits for

some

groups withlow

benefitsand

still restoreactuarialbalance.

Moreover,

since benefitlevelsaresomuch

lowerthan scheduledbenefits after75 years

and

since furtherbenefit reductionswould

follow in lateryears,this systemwould

beinpermanent

balance:The

passage of time itself, withunchanged economic and demographic

assumptions,

would

notproducelargerdeficits.In

summary,

Model

2 partially substitutes price indexing forwage

indexing indetermining initial benefits. It represents a shift in the focus of Social Security

away

from

itsrole inpreservinglivingstandards of workers

and

theirfamilies attimes ofretirement, disability,or death

and

to a lesser role of providing benefits that would,on

average, lag behind earnings. Thismodel

shows

clearly the implications of trying to close the long-term Social Securityactuarial deficit solely

by

benefit reductions.Although

it incorporates onlyone

particularpatternof

how

benefits could be reduced for workers born in different years, it illustrates the broader implications ofclosing the actuarial deficit purelyby

benefit reductions.Not

surprisingly, such an approach involves dramatic reductions relative to scheduled benefits.No

fundingwas

provided to lessen these dramatic reductions for beneficiaries with little or

no

ability todraw

upon

an individualaccount, suchas thedisabledand

young

survivors.B.

Model

3Proposals forTraditional Benefitsand

theirFinancing

Model

2is anexample

ofhow much

benefitsmust

be reduced torestore actuarial balanceifthere are

no

additional revenuesdevotedto Social Security.Model

3 insteadassumes

thatone-third ofthe actuarial deficit will

be

coveredby

new

dedicated revenues. It then eliminates therest of the actuarial imbalance

by

reducingmonthly

benefits in line withimprovements

inmortality (i.e., it reduces

monthly

benefits tofully offsetthe costof

providing benefits for longer expectedlives inretirement) along with additional reductionsforearlyretireesand

high earners.Life expectancy is expected to continue toincrease in the next 75 years.

Such

increaseshave

longbeen

part ofthe projections ofthe Office oftheChief

Actuary at Social Security.30The Social Security projectionshave been criticized bysome asunderestimating the futuredecline in mortality

rates. Forexample, the 1999 Technical PanelonAssumptionsandMethods ofthe Social SecurityAdvisoryBoard

Thatraises thequestion of

whether

the structureofSocial Security shouldreflectthis expectation of longer life expectancies.To some

degree, Social Security already reflects increasing lifeexpectancies.

The

discussion surrounding the 1983 reforms related the legislated increases inthe

normal

retirement age(NRA)

to projected increases in life expectancy. Nonetheless, itremains a legitimate question to ask

whether

Social Security shouldbe

modified further inresponse totheexpectedincreasesin lifeexpectancy.

First,

we

can askhow

an individual might sensibly adapt ifhe or she learned early in acareer that life expectancy

was

longer than had been previously thought.Such

an individualwould

recognize that theprevious plan of(1)consumption

and

savingwhile working, (2) an ageofretirement,

and

(3) aconsumption

plan after retirementwas

no

longer feasible.31Given

theincrease in life expectancy, it

would

no

longerbepossible toconsume

asmuch

each yearduringa career, retire at the

same

age, andconsume

asmuch

each year during retirement.A

sensibleapproach

would

have

the individualadjust all three marginsthat are available. Inotherwords,asensible individual

would

savesomewhat more

whileworking (consume

somewhat

less),work

somewhat

longer, andconsume

somewhat

lessper yearinretirement.Social Security allows individuals to enjoy larger

monthly

benefitsby

delaying the startof benefits

-

so the deferral option is already incorporated in Social Security. Indeed, for atypical 62-year-old

worker

(which is themost

common

age forclaimingbenefits), the increaseinbenefits

from

a delayed startroughly offsets the loss inbenefits.32 ForSocial Security to includethe other

two

responses toa longerexpected lifewould

call for increased payroll taxesand

lowerbenefits. Indeed,

one

could design apackage

of slowly increasing taxesand

a slowlydecreasingbenefits formula that couldbalance these

two

responses.The Commission

did not approach theissue in this

way,

however.underestimatefuturelifeexpectancies. 1999TechnicalPanelonAssumptionsandMethods(Washington:November

1999).

Anotherpossiblemarginistoreduceplannedbequests.

Forfurtherdiscussion ofthe actuarial adjustments in Social Securityand theireffects on claiming behavior, see

CourtneyCoile, PeterDiamond,JonathanGruber,and AlainJousten,"DelaysinClaimingSocial Security Benefits,"

NBER

WorkingPaperW73

18, August 1999.After recognizing the trend increase in life expectancy,

Model

3 proposes to reduce scheduledbenefits to fully offsetthe impact ofthe currently expected increasein lifeexpectancyon

Social Security outlays.The

particular proposal is to reduce benefits in line with actuarialcalculations for each

new

group of potential retirees.Given

current actuarial projections, thiscalls for a reduction in scheduled benefits of I/2 of 1 percent for each later year ofbirth.

The

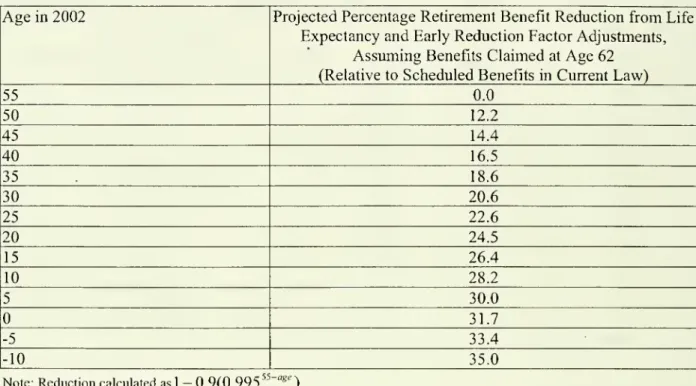

implications of such reductions are

shown

inTable 5.For

example, a current 35-year oldwould

have

a 9.5 percent cut relative to scheduled benefitsunder

this proposal.A

currentnewborn

would

experiencea24.1 percent reduction.Note

that theCommission's

approachwould

be

implemented

even in yearswhen

thenormal

retirement age is being increased under current law, supposedly also in response toincreased life expectancy

-

a double reduction for thesame

cause.Presumably

both of these reductions should nothappen

at thesame

time.Whatever

the motivation orjustification, the benefit reductionsfrom

this provision are projected tohappen

at roughly one-halfthe rate of benefitreductionsinModel

2.33

Actuarial Reductionand

Delayed

RetirementCreditThe

benefitsfor a retiringworker depend on

theage atwhich

aworker'sbenefitsstart. Ifa

worker

claims benefits at theNRA,

which

is slowly increasingfrom

age 65 to age 67under

current law, benefits are equal to the PIA. Ifa

worker

claims benefits at an earlier age, the benefits arereducedby

a factor thatis called the actuarial reduction.When

theNRA

was

65, aworker

claiming benefits at age 62would have

received 80 percent of the PIA.Under

current law, claiming benefits at age 62 results in 77.5 percent ofthePIA

since theNRA

isnow

above

age 65; as the

NRA

increases further under current law, that percentage will decline to70

percent (for workers turning age 62 in

2022

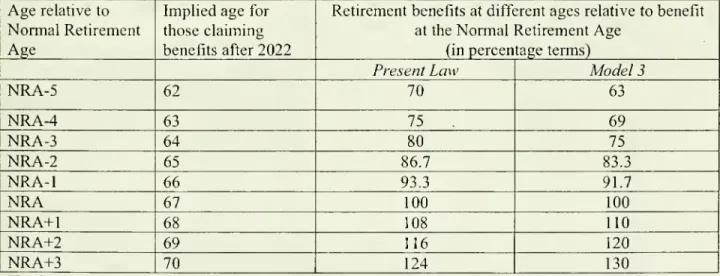

or later).Model

3 includes a further reduction of benefitsforworkerswho

starttheirbenefits beforetheNRA,

asshown

inTable 6.The procedure forupdating thebenefit adjustments for mortality shifts is somewhatunclear. In particular, the

Report states that the "adjustment wouldbe based on actual changes in period tables 10 years prior." Itremains

unclear whether the adjustment would be automatic, left to the discretion ofthe actuaries, or require legislative

Since

most

workers retire before thenormal

retirement age, theywould

experience largerbenefit reductions than

shown

in Table 5. In 1999, for example, 69 percent ofmen

and 73 percent ofwomen

claimedbenefitsbefore age65. Table 7shows

thereductions forretirementat age 62,

combining

the adjustments for life expectancy with thechange

in the actuarialreduction. .

(Model

3 alsoincorporatesotherchangesdescribedbelow.)While

acurrent 35-yearold

would

havea 9.5percent reductionfrom

scheduled benefits ifclaiming benefits attheNRA,

thereductionwould

be 18.6 percent ifbenefitswere

claimed at age 62.A

newborn

todaywould

experience a 24.1 percent reduction in benefits if claiming benefits at the

NRA,

and

a 31.7 percent reduction ifclaiming benefits at age 62.Reducing

benefits for 62-year oldsby

more

than forworkersretiringatlaterages isan incentiveto continueworking.35

Once

aworker

reaches theNRA,

benefits can be claimedwhether

theworker

retires ornot. Ifa

worker

delaysthe startofbenefits,benefits are largeronce

theydo

startbecause oftheDelayed

Retirement Credit(DRC).

Under

Model

3, theDelayed

Retirement Credit is increasedrelative to current law. In the absence of

major

behavioral changes, however, the increase islikely to affectvery

few

workers-

only thosewho

have

not claimedbenefits already. In 1999,only 7 percent of

new

retirement benefitswere

claimedby workers

age 66 orolder.37Moreover,

since benefits can

be

claimed ordelayedwhether

working

or retired, the increase in benefits fordelays

beyond

theNRA

does not noticeablyaffectthe incentive tocontinueworking.Lower

Benefits forHigh

EarnersModel

3 includes a reduction in the benefit formula for high earners, with the marginal benefit rate goingfrom

15 percent to 10 percent for the highest tier of covered earnings.38 (Inother words, an increase of $1 in averaged indexed

monthly

earnings in the highest earnings34

Committee on

Ways

and Means, 2000 Green Book, Table 1-13, page 53 (Government Printing Office:Washington,2000).

Of

course, such an incentivecould alsohavebeen achieved by increasing benefits forthose retiring laterratherthandecreasing benefitsforthoseretiringsooner.

Before the

NRA,

anearnings testlimits theability of workers to claim benefitswhile continuing towork. SeeJonathan Gruber andPeterOrszag, "WhatTo

Do

Aboutthe Social Security EarningsTest," Issue in BriefNumber1,CenterforRetirementResearch,BostonCollege, July 1999.

Committee on

Ways

and Means, 2000 Green Book, Table 1-14, page 53 (Government Printing Office:Washington,2000).

38

range

would

raise themonthly

benefit levelby

10 cents, rather than 15 cents as under current law.) This reduction is a progressive contribution to actuarial solvency: It reduces benefitsby

more

for higher earners than forlower earners,and

is expected toeliminate slightly less than 10 percentofthecurrent 75-yearactuarial imbalance intheprogram.Disabled

Workers and

SurvivingChildrenAs

withModel

2, the benefit reductions areassumed

to apply to the children of deceased workersand

to the disabledand

their dependents for actuarial scoring.Thus

a 20-year oldworker

todaybecoming

disabled atage40

(in 2022)would

experience a 7 percent reduction inbenefits,

and

aworker becoming

disabled in2075

would

experience a29

percent reduction inbenefits (Table 8).

The same

effectswould

apply to the childrenof

deceasedand

disabled workers.As

withModel

2, theCommission

failed to provide funding for mitigating theseeffects.

Long-Career

Low

Earnersand

Widows/Widowers

As

underModel

2,Model

3 contains proposals to increase benefits forlow

earnersand

survivingspouses with

low

benefits.39With

thebenefitreductions inModel

3 being smallerthan benefit reductions inModel

2, the increase in benefits forlow

earners is smaller in percentage terms (since the expansion is intended to provide at least the poverty level of income,and

since base benefits are higherunder

Model

3).The

details of this proposal are in Table 9.The

maximal

percentage increase of 18 percentis not sufficient to offset the reductions in traditionalbenefits for workers

who

are22

oryounger

who

claim benefits atthenormal

retirement age or workersyounger

than43who

claimbenefitsat age 62.The

proposalforsurviving spouses isthesame

as inModel

2.Even

with this increase in survivor benefits relative toworker and

spousebenefits, the steady decline in traditional benefits for workers

and

spouseswould

eventuallybe

larger than the increase

from

this adjustment.Thus

widow

and

widower

benefitswould

eventually be lower than those scheduled in current law.

The

cost of thetwo

proposals isroughly the

same

forModel

3 as forModel

2.Actuarial Balance

The

reduction in retirement, disability,and

survivor benefitsfrom

indexing the benefit formula forlife expectancy,combined

with thechanges inthe actuarialreduction factor, delayed retirement credit, benefits for high earners and the increases in benefits for long-careerlow

earners and

widows

andwidowers

withlow

benefits, generates the 1.31 percent of payrollimprovement

in actuarial balanceshown

in Table 10.However,

these changes,by

themselves,arenot sufficienttorestore actuarialbalance:

The

actuarial imbalance remainingamounts

to 0.55percentofpayroll.

To

eliminate the remaining imbalance,Model

3 proposes an increase in revenues dedicated to Social Security, sufficient to cover roughly one-third ofthe actuarial deficit.The

Commission

does notrecommend

any

particular source for these revenues.However,

it doesscore the dedicated revenues as ifthey

came

from

an increase in themaximum

earnings subjectto payroll taxation

and

a transfer ofsome

ofthe revenuefrom

theincome

taxation ofbenefitsfrom

Medicare

to Social Security.40The

Commission

does not indicatehow

to avoiddeterioration in Medicare's financial position in response to the loss

of

revenues under thisapproach.41

As

withModel

2, since benefit levels are somuch

lower than scheduled benefits in 75 yearsand

since furtherbenefit reductionswould

follow in later years, this systemwould

notgo

Thescoringofthe transfersassumedthatthepercentageof coveredearnings subjecttotaxincreasedto86percent

between2005 and 2009, andwas thenmaintainedatthat level thereafter. Therevenues transferredfromMedicare

to Social Security werephased in between2010 and 2019. Undercurrent law, Social Security beneficiaries with

modified adjusted gross income above $25,000 if single or $32,000 ifmarriedhave partoftheir Social Security

benefits includedinincomefortax purposes. Forincome abovetheselevels, 50percentofSocial Security benefits

areincludedin incomefortaxpurposes. The incometaxderivedfromincluding these benefitsintaxableincome is

creditedtothe Social Security TrustFund. Forthehighest-incomebeneficiaries(thosewith incomesabove$34,000

ifsingle or $44,000 ifmarried), up to 85 percent ofSocial Security benefits can be included in income for tax

purposes.

Any

income taxderived fromincludingmorethan 50percentofbenefitsin taxableincomeiscreditedtotheMedicareTrustFund.

In what may be the only dissenting word in the Report, "Some members ofthe Commission believed that a

substantialportion ofthis 0.63%shouldcome froman increase inthe payroll tax base....However, this suggestion

wasdeemedinconsistentwiththeprinciplesintheexecutive order establishing theCommission."(footnote 41,page

131).

out of balancejust

from

the passageof

time (assumingunchanged economic and demographic

assumptions).

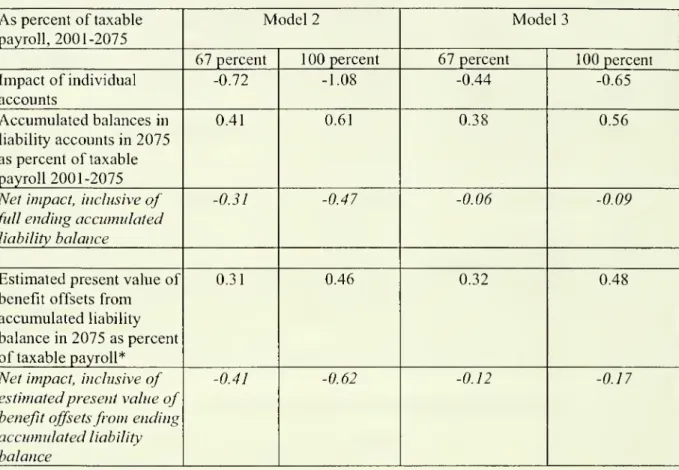

II. Introduction of Individual

Accounts

Following the charge to the

Commission,

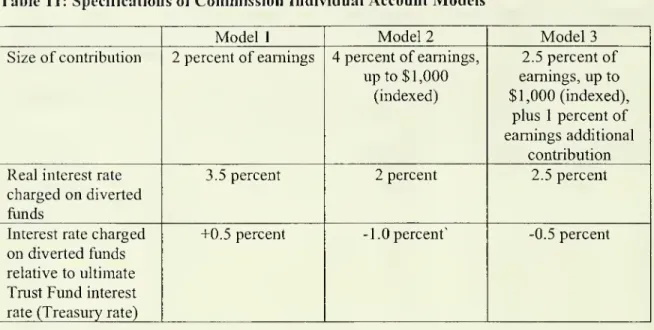

the Report presents a design for individual accountsthat isusedin allthree reform models.We

beginby

consideringthe generalstructure ofthe proposed accounts.

Then

we

considerthe effectson

actuarial balance, TrustFund

balances, Treasuryborrowing

from

the public,and worker

assetsand

benefits.In broadterms,

workers

underall three planswould

be giventhe option ofhavingpartoftheir payroll taxes deposited into individual accounts.

The

individual account systemwould

involve

two

components: the individual account assets,which

would

containa worker's deposits and the accumulated earningson

them,and

a"liabilityaccount." Ifaworker

chose to participate inthe individual account system, the portion ofhis orher payroll taxes diverted intothe accountwould

accumulate during the worker's career,and

be available to theworker

upon

retirement. Since therevenue diverted to this accountwould

reduce the financing available to the traditionalSocial Security system, a liability account

would

alsobe

created. This liability account accumulates theamounts

diverted plus interestand

so determines the debtowed

back

to Social Security because ofthe diverted funds.Upon

retirement, the debtwould

be repaidby

reducingtraditional Social Securitybenefits.

A.

Account

Specification-

AssetAccumulation

In all three models, workers are given the option of having part oftheir payroll taxes deposited into theirindividual accounts.

These

diverted fundsareused

topurchase assets from alimited

menu

ofalternatives, withone

menu

organizedby

thegovernment

forthose with small accounts (Tier I) and additional choicesfrom

private providers for those with larger accounts (Tier II).The

Tier I structure ismodeled on

the Thrift Savings Plan that handles defined contribution accounts for federal civil servants.Under

this tier,workers

could chooseamong

nine differentmutual funds.42 Forthosewith balances

above

$5,000 (adjustableinthe future, but without specifiedrules), therewould

be a furtheroption ofmoving

the entire balance outofTierI and investing with a private fund manager.

These

fundmanagers

could offerthesame

optionsas in Tier I

and

could offer additional options, although the latterwould

be restricted to bewidely diversified funds.

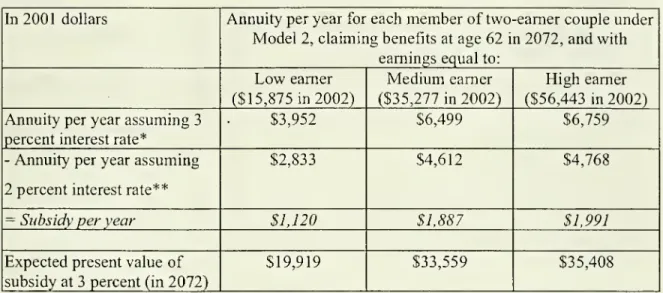

In assessing the implications ofthebalances in these accounts, the

Commission

assumes

that Treasury

bonds

would

have

a 3 percent gross annual real yield, corporatebonds

a 3.5percent gross annual real yield,

and

stocks a 6.5 percent gross annual real yield. All threenumbers

are reasonableand

consistent with the 3 percent real interest rate assumption usedby

the actuaries in assessing the evolution oftheTrust Fund.43 In converting grossyields to yields

net of transaction costs, the

Commission

assumes

an annual charge of 30 basis points (0.3percent) of assets under

management.

Such

an administrative cost cumulativelyconsumes

roughly six percent of the account balance at the

end

of a 40-year career relative tono

administrative charges. Several issues arise in considering this estimate for the administrative charges.4

First, in the early years, setting

up

the initial set of accountswould

involve additionalone-timecosts, and the

assumed

30 basispoint chargescouldnotcrediblycoverthese costs.The

Commission

ignores this short-runproblem, focusingon

a long runwhen

theaccountswould

belarger.

42

An

individual couldput all ofthe accountinto one ofthe three balanced funds (which combine equities withfixed-income assets, and vary in thepercentage in stocks). Or an individual could divide theaccount among six

mutual funds (large stocks, small stocks, foreign stocks, corporate bonds, Treasury bonds, and inflation-indexed

Treasury bonds). Information about the Tier I accounts would be available online and by automated phone, but

written statements wouldbe sentonlyonce peryear. Changesto the allocationofeitherexistingbalances ornew

deposits wouldalso be allowedonceper year. Collectionof revenuesand allocationto individual accountswould

bedoneinconformity withcurrent payroll taxcollection,implyingthat therewouldbesignificant lagsbetweenthe

transmission oftaxes by the worker's employer and when the funds were invested as the worker designates. In

addition, individualspayingtaxesatdifferenttimesoftheyearwouldallbetreated asiftheypaidtaxesatthesame

time.

Theassumption onstocks does not address the likelihoodthat stock returnswill be much lowerin theshort

run thaninthelongrun.

On

stockreturns, see PeterA.Diamond,"WhatStockMarketReturnstoExpectfortheFuture?" Social SecurityBulletin,2000and SocialSecurityAdvisory Board, EstimatingtheReal RateofReturn

onStocksOvertheLong Term,Washington,DC,August2001

.

For more discussion of administrative costs, see Peter A. Diamond, "Administrative Costs and Equilibrium

Charges with Individual Accounts, " in John Shoven (ed.), AdministrativeCosts andSocial Security Privatization