16

Reading Facsimile Reproductions of Original

Artwork:

The Comics Fan as Connoisseur

Jean-Paul Gabilliet

Abstract

By focusing on the recent French and American phenomenon of “classic” comics reprinted in actual-size facsimile reproductions of original artwork instead of the traditional reduced four-color format, this paper addresses the diversity of practices among “comics readers,” from the most casual to the most sophisticated. Unlike individual relationships to the medium emphasizing bibliophily, academic interpretation, or sketch-hunting, the appreciation of volumes of original comic art exemplifies a connoisseurship combining archaeological and esthetic aspirations. Its agenda is to experience a reading that enables one to get as close as possible to the past actuality and, ideally, the authenticity of the cartoonist’s creative process before it was altered by the cultural industry.

Keywords

17

In the last decade, one notable phenomenon in the U.S. and French comics publishing industries has been the multiplication of “classics” issued in pricey, oversized hardcover books containing facsimile reproductions of original artwork. The corpus under consideration in this paper includes the two most representative French and American examples of these new volumes: Marsu Productions’ “Collection V.O.” (which started reprinting André Franquin’s Gaston Lagaffe and Spirou et Fantasio in 2005) and IDW’s “Artist’s Edition” (which, since 2010, has featured some of the “best” material of various key American comic book artists, at least according to the conventional wisdom of mainstream comic fans).1

The emergence of such books raises a number of questions that can be addressed in the framework of the inquiry conducted in the late 1990s by French researchers Gérard Mauger, Claude F. Poliak, and Bernard Pudal into the sociology of reading practices and the uses of reading (Mauger et al.). Comics reading as a practice (or, more exactly, a set of practices) is admittedly an understudied topic, whether in relation to traditional U.S.-type floppy comic books (and Francophone revues de bandes dessinées) or more contemporary “graphic novels” (and albums, their European precursors)—and has been so since the moral panics over comics that took place in western countries from the mid-1940s through the mid-1950s. Parents, educators, child psychologists, law enforcement representatives, and politicians then allied together to stigmatize comics reading as a crime-inducing behavior pattern and comic magazines as cultural artifacts liable to encourage mass “demoralization” and delinquency among children and adolescents in societies that were still recovering from the hardships of the Second World War (see Crépin for France; Nyberg for the U.S.; Lent for an international panorama). It was not until 2015 that La bande dessinée: quelle lecture, quelle culture? [Comics: what reading, what culture?], a report jointly commissioned by France’s Ministry of Culture and the Centre Georges Pompidou-based Bibliothèque Publique d’Information (BPI) [Public Information Library], proceeded to look into the various facets of comics reading in France, from both quantitative and qualitative social sciences perspectives (Berthou). To the best of my knowledge no similar study has yet been produced in English.

Whether it is considered in relation to comics or any other species of printed material, “reading” is generally the proverbial tip of the iceberg, a term unduly emphasizing the descriptive dimension of an activity whose praxis and significance vary widely according to the individual engaging in it—incidentally the same can be said about practically all forms of cultural consumption: movie-going, television watching, museum-going, music listening, etc. When it comes to comics, the diversity of “reading” practices is actually very wide, from occasional readers to hardcore hobbyists of various kinds. For casual readers, comics correspond to one form of recreational, escapist practice among many others. Hoarders of books or floppies will exemplify a reading-intensive approach to the medium. Collectors of “old” comics will inscribe them within practices typical of bibliophily, where reading is a distant second to owning. The agenda of scholastic2 readers is

primarily to interpret comics in terms of academic analysis. Nostalgics will often limit their reading to material (collectables or reprints) liable to be attached to childhood memories. Convention sketch hunters, for some 1 Originally an independent Monaco-based publishing company created in 1986 by Jean-François Moyersoen to market a graphic novel line featuring Franquin’s Marsupilami, Marsu Productions was bought up by the Belgian publisher Dupuis in 2013. IDW is the publishing branch of Idea and Design Works, a San Diego-based media company created in 1999 ; at the end of 2015 it was the U.S. comic book specialty market’s fourth largest publisher after Marvel Comics, DC Entertainment, and Image Comics (“Diamond Announces”).

2 The term is used here in reference to Pierre Bourdieu’s analysis of the scholastic point of view, i.e. the “detached” intellectual posture of scholars, who objectivize reality and thereby often run the risk of losing sight of its practical dimensions (Bourdieu).

18

of whom reading per se is quite a secondary concern, will assign value to their comics only as long as they are adorned by personalized drawings done by the cartoonist.3 Notwithstanding are the many comic fans who

exemplify hybrid practices combining several approaches…4

What sort of reading material is found in volumes of facsimile reproductions? The back cover blurb of Marsu books outlines a specific agenda:

This album […] contains reproductions of André Franquin’s original artwork, whose outside appearance has been preserved. Lines are not printed in black and white but in color. Many new details thereby become visible, just as if you were sitting at the master’s drawing table. The yellowed paper, traces of penciling under the greasy ink, whiteout touch-ups, annotations in the margins, pre-printed blue lines for lettering—everything has been preserved for an all-new exploration of Franquin’s work. (my translation)5

Those books enable readers (more precisely those who can afford them) to “re-discover” previously known material in the format of black and white original artwork instead of the usual reduced four-color mass-produced format. In the IDW volumes, each page is an actual-size color photograph of the original art. The Marsu line offers titles reproduced in the same way (mostly the Spirou et Fantasio albums since QRN sur Bretzelburg in 2008) but also ones in which traditional photogravure black and white line art is blown up to the size of original pages (Idées noires 2005; Le Nid des marsupilamis 2006). Some volumes (for instance “L’intégrale Gaston”) consist of reproductions of both kinds.6

The packaging of those books is, in itself, telltale. Each IDW Artist’s Edition copy “is shipped in a custom cardboard box for maximum protection,”7 given the books’ unusual weight of 2 to 5 kilograms (5 to 11

pounds)—as opposed to the lighter Marsu books, weighing in at less than 2 kilograms (4 pounds). However, as specified in their final endpapers, Artist’s Edition volumes are “dedicated to showcasing outstanding artists in a format as special as their work deserves.” In this context weight matters as much as size: while Marsu books are 30 x 43 cm (12 x 17 inches, no less than 1.5 times the standard size of Dupuis albums), IDW volumes range from similar sizes (Dave Stevens’ The Rocketeer) to a more spectacular 39 x 57 cm (16 x 23 inches) for MAD or Will Eisner’s The Spirit. (Fig. 1)

3 I obviously do not include as “readers” the sketch hunters whose actual agenda, distinctly remote from any reading enjoyment, is to obtain free drawings from cartoonists only to auction them off on the web later (Vandenberghe; Walter & Kubacki).

4 This enumeration is based on my own forty-year-long experience as a participant observer of French and North American comics fandoms. Evidently such generalizations, regardless of their ideal type agenda, tend to erase occasional distinctions between French and North American fans.

5 Original French text: “Cet album de la collection « V.O. » (Version Originale) est constitué de reproductions de planches ori-ginales d’André Franquin, en conservant leur aspect réel. Les traits sont imprimés, non pas en noir et blanc, mais en couleurs. Apparaissent alors de nombreux nouveaux détails, comme si vous étiez à la table à dessin du maître. Le papier jauni, les restes de crayonnés sous l’encre grasse, les retouches à la gouache blanche, les notes dans les marges, les lignes bleues imprimées qui servent de portées au lettrage, ... Tout a été conservé pour une exploration inédite de l’œuvre de Franquin.”

6 Other publishers have released “art books” that include facsimile original art, such as Editions Albert René’s deluxe version of Astérix vol. 36, Le Papyrus de César (2015) or Genesis West’s Conan – Red Nails (2013) by Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith.

19

To lay observers, size is really the defining characteristic that makes volumes of facsimile original art out-of-the-ordinary objects, as this anecdote from comics critic Tom Spurgeon suggests:

[…] a friend of mine and I were in a comics shop when we saw the Simonson book [Walter Simonson’s The Mighty Thor: Artist’s Edition]. He saw this massive thing behind the desk and asked me about it. I told him what it was, and he had the owners prepare a little space for him to check it out and he eventually bought it. It struck me while watching my friend basically take the book out for a special test drive that this isn’t a typical item for a lot of stores. (Spurgeon) (Fig. 2)

Predictably enough, such items have low print-runs. Marsu’s Gaston Lagaffe and Spirou titles are limited to 2,000 to 2,200 copies (the 2009 reprint of Idées noires had an exceptional print-run of 3,000). IDW does not disclose the print-runs of its standard volumes but occasionally issues ultra-limited editions, from 100 copies (Will Eisner’s The Spirit) to 250 (Gil Kane’s The Amazing Spider-Man).8 The standard volumes issued

by Marsu retail for 99 to 119 euros; the IDW books range from 100 to 150 U.S. dollars. As they are 100 to 200 pages long, they are indeed expensive books. Even in unnumbered editions, they pertain to reading practices predicated by economic and cultural elitism.

Superficially, they seem to exemplify Thorstein Veblen’s “conspicuous consumption” among comic fans: expensive, heavy, cumbersome, impossible to shelve next to “normal” graphic novels, these volumes cumulate all the characteristics of commodities designed to display their owners’ standing rather than fulfill their alleged cultural function, i.e. enabling one to read a comics narrative. This function is very dubious in the first place anyway—repackaging in oversized coffee-table books material that has been reprinted over and over in affordable formats for decades de facto disproves the view of comics as a democratic art form, widely accessible both economically and culturally to people from all walks of life (such as it was articulated by Leslie Fiedler in 1955 in his Encounter essay “The Middle Against Both Ends,” for instance). Yet only comic fans—actually only certain comic fans—will go out of their way to purchase such books.

8 One exceptional title is Sergio Aragonés’ Groo the Wanderer Remarqued Cover Edition, of which each 1200 U.S. dollars copy (out of 25) sported a different piece of original cover art. Such an extravagant price is an extreme example however.

Fig. 1: Comparative sizes of four books (from L to R): a traditional Dupuis album, its larger Marsu version, IDW’s Dave Stevens’ The Rocketeer, and IDW’s MAD. Photograph from the author.

20

Another major difference between the two publishers concerns paratexts. Whereas IDW books typically include short prefaces or forewords, each Marsu volume supplies a critical apparatus that situates the album within both its historical context and Franquin’s career. Such bonuses, on top of the original art, underscore the quasi-hagiographic concerns running through a collection devoted to one creator. Still, while IDW publishes what is admittedly the best output of several creators, a similar fetishization is clearly perceptible in the name of its line: “Artist’s Edition” unambiguously echoes the “director’s cuts” so prized by the home video industry nowadays.9

In comics like in film, emphasizing the figure of the artist underlies a set of beliefs in the singular quality of the creator. Nathalie Heinich interprets such beliefs as a value system that dismisses the demands and expectations of the “merchant world” as so many hindrances imposed upon the “inspired world” that is the artist’s ideal space of practice, creation, and agency. Packaging comics narratives in volumes the size of original artwork and removing the coloring that adorned the pages when they were first published in magazines or graphic novels predicate a return, both symbolical and practical, to the roots of the creative process— before the technological process leading from original art to printed art, before the commercial process that transforms the handiwork of an author into a commodity marketed according to the identities of the creator and series: Franquin’s Gaston Lagaffe, Barry Smith’s Conan, Will Eisner’s The Spirit, etc.

The two factors are likely to combine in various ways according to individual reading habits. Someone mainly seeking escapism will privilege a narrative genre or formula and its stereotypical characters regardless of the creators’ specificities (this is typically how children choose their comics). Meanwhile, another reader with a more complex, “sophisticated” relationship to the medium will rationalize their choices on behalf of 9 A different form of fetishization is exemplified by DC Comics’ Absolute collections, oversized slipcased hardbacks including color reprints and extras of various kinds retailing for about 50 U.S. dollars in the primary market. They cater to readers whose essential agenda is the sort of augmented escapist enjoyment one experiences when watching a Blu-Ray with a home theater equip-ment rather than a traditional TV set. “Enhanced escapist reading with a touch of connoisseurship” best describes this sort of cultural practice.

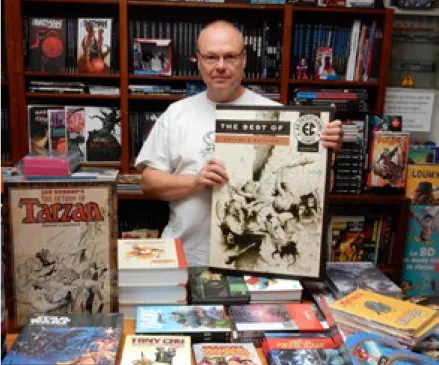

Fig. 2: Tony Larivière, proprietor of the Atomik Strip comic store (Andenne, Belgium), presenting an IDW Artist’s Edition volume.

21

their appreciation of a creator or creators, yet without necessarily attaching importance to a genre’s more or less predictable narrative horizon; for instance, such a reader will enjoy any comics by Wally Wood, whether they are EC stories, 1960s superhero fare or later alternative, Witzend-type material. Given the broad diversity of reading practices, referring to a generic comics reader is tantamount to hypothesizing a sociological chimera. Consequently the quantitative data tallying sales figures by genre are actually of little, if any, use to construct qualitative outlines of the reading practices incarnated in each reader and to document the individuals that alternately engage in escapist and connoisseur forms of reading, depending on which books they choose to read at a given time.

In certain Marsu books the critical apparatus emphasizes what is described as the restoration of the artist’s original intent, contrasting with their publishing histories as Dupuis albums. Several of the Spirou et Fantasio narratives drawn by Franquin were initially collected in albums with extensive alterations. The pages of those stories were designed in accordance with the layout constraints of the weekly Journal de Spirou: from the early 1950s through October 1965 its cover featured a title topper above a three-tier page of the Spirou et Fantasio story then under serialization, generally followed by two four-tier pages on the inside front cover and first inside page. Yet, when the same stories were collected later, the four-tier format of each album page caused many cliffhanger panels placed in the bottom right corner of the magazine pages to appear at the top or in the middle of album pages.

Although it is fascinating to rediscover the page and panel layout originally designed by the artist, one should yet not mistake his “intentions” for some pure and perfect creative freedom. Even when reproduced photographically, the original artwork of Franquin or the U.S. comic artists featured by IDW resulted as much from the creators’ gestural and stylistic singularity as from their internalization of down-to-earth editorial constraints in terms of format (epitomized by the lettering and live area blue lines pre-printed on art boards), pagination and, on a less purely visual level, of the presumed expectations of readers regarding genre narratives. Unlike “old-time” artists (pre-1980s for the U.S. and pre-1970s for the Franco-Belgian area), whose creative horizon was essentially limited to the readership of periodical magazines, contemporary comic artists (whether mainstream, or alternative, or anywhere between these loose creative labels) have incorporated into their practices the consideration of the two clienteles from which they derive their incomes—readers on the one hand, and galleries and art collectors on the other. Hence, equating the “reconstruction” of the author’s intentions and the return to some genesis of each original art page appears as a deceptively self-evident and truly anachronistic assumption. Original art pages have always been black and white templates created first and foremost in order to be reduced, colored and printed in mass-produced magazines (West 170). For decades the sensitivity to the aesthetic potential of original comic art was a minority posture outside the milieu of cartoonists (who, incidentally, in their overwhelming majority used to regard themselves as craftsmen more than artists and appraise the pages they drew as more or less well-mastered craft rather than inspired works of art). The artistic appreciation of original comic art became a little more common, albeit definitely not widespread, very gradually from the 1970s onward, with two parallel phenomena—the multiplication of original art exhibits and the growth of a collectors’ market (Beaty 153-209).

Yet, in France, the cultural legitimization of la bande dessinée started off in the 1960s with hardly any exposure to original art. The construction of an aesthetic sensitivity to the medium initially used to focus on

22

printed pages. The visitors of the exhibit “Bande dessinée et figuration narrative” held at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in the spring of 1967, the first prestigious event celebrating the comics medium in France, did not see one piece of original artwork. They were instead treated to photographic blowups of printed panels or pages (sometimes as large as 3 x 4 meters), selected by the curators to highlight the artistic potential of comics:

to enable the public to really see the comic strip, to help it distinguish that which is art in the artist from that which is betrayal in the newspaper. Thanks to the quality of the paper and the clarity of the blacks and whites, the photographic enlargement makes it possible to free the comic strip from the small size that stifles it and to exhibit it in the usual dimensions of the works of art to which the public is accustomed. The works of certain artists can be enlarged, without loss of quality, to an extraordinary size (pictures of six inches enlarged to six and a half feet or more). The large size of these pictures and of the original drawings was a revelation that was ultimately to bring the comic strip into the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in the Louvre. (Couperie and Horn 145)10

The first-generation actors of French bédéphilie were readers, not creators. To them the aesthetic appreciation of comics was mediated by printed pages and panels, whereas original art pertained to the technological domain of publishing, of which the general public knew next to nothing. Mostly because it was then difficult to gain access to significant amounts of original art, particularly from across the Atlantic, exhibiting reproductions, very often enlarged ones, was the customary practice in France well into the mid-1970s.11

A half-century later, there has been a slight evolution in the general public’s perception. Although original comic art has become a more familiar reality for those who collect it and for the small segment of the public that attends exhibits, comics nowadays refer for the general public to a medium whose main vehicles are books 23 x 32 cm in size or smaller. This is the reason why Artist’s Edition and Marsu books are commodities effectively designed for fans that entertain a “connoisseur” relationship to comics. They are individuals for whom spending a substantial sum (over 100 U.S. dollars or euros) on a comic, however bulky, is an economic decision hardly ever predicated by conspicuous consumption but rather by a form of “scholarly” familiarity with the medium and the artists whose artwork is reprinted—even when they are not professional scholars. This relationship is mediated by a substantial knowledge of the history of comic art—its periodization and its personalization around key creators. Explicitly or implicitly, consciously or unconsciously, connoisseur fans rely upon notions drawn from literary history and art history—such as the canon, tradition, classics—to rationalize their relationship to the medium. It is because such readers are knowledgeable about the practical dimensions of the creative process that they give pride of place to the original art page as the end-result of the author’s craft, instead of regarding it as a negligible, invisible, and immaterial template preceding the mass-10 The reference to original art here concerns the three exhibitions organized in Paris in 1965-1966: “Dix millions d’images” [Ten Million Pictures], “Burne Hogarth”, and “Milton Caniff.” The 1967 event only featured enlarged photographs of pages and panels.

11 Hardly any original artwork was featured in the exhibits held during the first three Angoulême festivals, from 1974-1976. The existing scholarship about the history of this annual event, which is still surprisingly underdeveloped, yields hardly any information about the exact contents of the exhibits shown during its first years. Nevertheless a careful scrutiny of the surviving TV news footage suggests that the first significant exhibition of original comic art in Angoulême was the one devoted to Hergé in 1977.

23

printed page.

Still this particular approach is anything but “natural.” Andrei Molotiu has analyzed how, to anyone beholding original art in a museum or gallery, the habitual reading of a comics page (i.e. the linear discovery of the narrative) becomes secondary to the awareness of the art board, the drawings, and the various visual effects that can be seen on it:

[…] a strange development occurs when we confront the original, hand-drawn boards: rhetorical devices, narrative techniques, and so on are lessened in importance proportionally with the de-emphasis of our attention to story and plot. The material support of the narrative sequence no longer presents itself as a (ideally) transparent medium, and the rhetorical, meaning-producing level of the text is revealed as belonging only to the most superficial layer of a thick palimpsest of brush and pen strokes, touches of white-out, blue-penciled editorial interventions, traces of penciling, marginal instructions from writer to inker, and so on. (Molotiu)

Such a schizophrenic relationship is largely specific to this medium: reading a comic and beholding comic art typify distinct acquired tastes—which explains the spontaneous reaction of my 10-year-old daughter who described as “ugly” the pages of one Marsu Spirou et Fantasio title I showed her after she derived great pleasure from reading the very same story in the traditional four-color Dupuis album format.

The connoisseur readers’ relationship to comics is arguably comparable to that of an archaeologist-cum-aesthete who, without having necessarily heard of Walter Benjamin, de facto believes in the idea that “The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity” (Benjamin 13). For them the highest expression of commitment to the medium is to establish the closest possible proximity to a given comics narrative by perceiving it through its original artwork (or through the best photographs thereof), for example, through the artifacts produced and “desired” by the artist(s) in the first place. For such readers, facsimile reproductions of original art constitute the most satisfactory vehicle to gain access to the traces, gestures, hesitations, changes of mind, and thousand occurrences making up the authors’ daily lives (such as the shopping lists or phone numbers sometimes scribbled in the margins). Facsimile original art also enables them to become privileged observers of several aesthetically charged aspects of the cartoonist’s craft, such as the changing thickness of lines or varying darkness of blacks. They love being privy to all the details and visual blemishes that have been erased in the technological process of mass reproduction. Their enjoyment of a narrative told in comics is equaled if not overtaken by the discovery of another one: the simultaneous, concealed narrative of the creative process.

This quest is necessarily frustrating. However close one gets to the gestures that gave birth to the lines drawn on paper, original art pages provide only traces of the cartoonist’s craft. Very much like fragments of ancient pottery displayed in a museum showcase, they are essentially remains from a past human agency that have been elevated to artwork status—hence the educated gaze of an archeologist and esthete necessary to grasp the cultural significance of those books. IDW and Marsu volumes are elitist forays into an allegedly democratic medium, where the archeological scholarly gaze substitutes escapist immersion. The readers of those books do not primarily read a comic as a text (in the semiological acceptation of the term) but as an artifact. The story in which they immerse themselves is not the diegesis imagined by the creators but the

24

history of the comic’s production reconstructed by means of the imprint of the creators’ craftsmanship in a medium where pictures are worked into narrative construction.

Volumes of facsimile original art draw our attention to the co-existence of at least three forms of reading for comics. The first one is escapist reading, which primarily seeks entertainment and de facto brands comics as commodities; this type of reading (which has always been indispensable to the economic survival of publishers) generated the social stigma attached to the medium throughout most of the 20th century. By

contrast, scholarly types of reading are of two types: the hermeneutic one, which (broadly speaking) chooses to consider the comic as a text from a semiological perspective and aspires to elucidate its meaning, and the archeological one, which chooses to see the comic as an artifact likely to reveal the circumstances of its creation through the traces left by the author’s agency. The three sorts of reading are not mutually exclusive, but in practice, only a limited number of readers will combine them (Mauger 15).

In this day and age when the marketing of comics as mass-produced periodical pamphlets is gradually becoming a practice of the past, the evolution of comics publishing in the last half-century has taken place in parallel with the consolidation of the social uses of comics reading: while saddle-stitched magazines were typical of and culturally adjusted to escapism-oriented reading, the gradual rise of albums in postwar western Europe and of trade collections or graphic novels in North America as of the 1980s was largely conducive to the development of hermeneutic reading by making primary sources available in affordable, easy-to-handle formats (very much in the same way as the mass-market paperback revolution democratized the study of literature after World War II). Collections of facsimile original art are vehicles created for connoisseur reading, a social use of comics typical of individuals whose enjoyment of the medium transcends escapism, attaches more value to artifacts than to texts, and entails the spending of substantial sums. They are ultimate picture-books, concentrates of the history of the medium as craft and artistic practice, objects of connoisseurship predicated by an implicit, often unconscious auteur theory-based value system in which aesthetic appreciation is encapsulated in the synergy between the creators’ assumed authorial intentions and the original traces of their craftsmanship. But at the same time they can be precious tools for those scholars engaging in genetic criticism and documenting the avant-texte phase of comic-making (Vigier).

Works Cited

Beaty, Bart. Comics Versus Art. Toronto UP, 2012.

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Prism Key Press, 2010.

Berthou, Benoît, editor. La bande dessinée: quelle lecture, quelle culture? Editions de la

Bibliothèque publique d’information, collection “Etudes et Recherches,” 2015, http://books.openedition.org/ bibpompidou/1671. Accessed 1 Mar. 2015.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Practical Reason. Stanford UP, 1998.

Couperie, Pierre, and Maurice C. Horn, editors. A History of the Comic Strip. Crown, 1968.

Crépin, Thierry. “Haro sur le gangster! ”: La moralisation de la presse enfantine, 1934-1954. CNRS Editions, 2001.

“Diamond Announces Top Selling Comic Books & Graphic Novels of 2015.” Diamond

25

2016.

Fiedler, Leslie A. “The Middle Against Both Ends.” Encounter vol. 5, 1955, pp. 16-23. Heinich, Nathalie. Être écrivain. Création et identité. La Découverte, 2000.

Lent, John A., editor. Pulp Demons: International Dimensions of the Postwar Anti-Comics Campaign. Farleigh Dickinson UP, 1999.

Mauger, Gérard, Claude F. Poliak, and Bernard Pudal. Histoires de lecteurs. Nathan, 1999.

Molotiu, Andrei. “Permanent Ink: Comic-Book and Comic-Strip Original Art as Aesthetic

Object.” The Hooded Utilitarian, 18 Oct. 2010, http://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2010 /10/permanent-ink-by-andrei-molotiu/. Accessed 26 June 2013.

Nyberg, Amy Kiste. Seal of Approval: the History of the Comics Code. Mississippi UP, 1998.

Spurgeon, Tom. “CR Newsmaker Interview: Scott Dunbier.” The Comics Reporter, 6 Apr.

2012, http://www.comicsreporter.com/index.php/resources/interviews/38772/. Accessed1 May 2015.

Vandenberghe, Gérard. “BD: ce business des dédicaces qui dérange les dessinateurs.”

RTBF.be, 4 Feb. 2016, http://www.rtbf.be/info/medias/detail_bd-ce-business-des-dedicaces-qui-derange-les-dessinateurs?id=9205295. Accessed 21 Feb. 2016.

Veblen, Thorstein. The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions. Macmillan, 1902.

Vigier, Luc. “Génétique de la bande dessinée.” Littérature, vol. 178, 2015, pp. 80-92.

Walter, Anne-Laure, and Marie-Lucile Kubacki. “Scènes de chasse aux salons.” Livres Hebdo, vol. 857, 2011, pp. 34-37.

West, Richard V. “Comics as ‘Ding an Sich’: A Note on Means and Media.” Children of the

Yellow Kid: The Evolution of the American Comic Strip, edited by Robert C. Harvey, Frye Art Museum

and Washington UP, 1998, pp. 168-172.

Dr. Jean-Paul Gabilliet is a professor of North American Studies with the Department of English at Université

Bordeaux Montaigne, France. He specializes in the cultural history of comics in North America and Europe since the 19th century. He has authored Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books (UP Mississippi, 2010) and the biography of a famous underground cartoonist simply titled R. Crumb (Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux, 2012). He is now more specifically documenting the transformation of comics, reading into a mainstream cultural practice in Europe and North America in the last few decades of the 20th century. Email: jnplgabilliet@gmail.com