30

The visualisation of Strawberry Hill:

A collusion of history and imagination

Marion Harney – University of Bath

Abstract

Horace Walpole is renowned for his creation of the celebrated Gothic villa Strawberry Hill and author of

The Castle of Otranto. Both are fabrications of his imagination originating in “a head filled like mine with

Gothic story”. This paper explores how visual and textual sources, authored or solicited by Walpole, express a nuanced reading of how the castle and collection are linked as unified forms of display. It demonstrates how Walpole constructed a visual narrative that led the observer through periods in history to stimulate a dynamic dialogue with the past through significant historical figures and events in English history.

Résumé

La réputation de Walpole est due à deux créations: sa villa gothique de Strawberry Hill et son roman Le Château d’Otrante. L’une et l’autre sont le produit de son imagination ayant pris sa source dans « un esprit rempli comme le mien d’histoires gothiques. » Cet article explore les sources visuelles et textuelles, inventées ou utilisées par Walpole, et tente de proposer une lecture nuancée des liens entre château et collection comme dispositifs d’exposition. Il démontre comment Walpole a construit un récit visuel qui condit l’observateur à travers plusieurs périodes historiques afin de stimuler un dialogue dynamique avec le passé à travers une série de personnages et d’événements de grande importance pour l’histoire de l’Angleterre.

Keywords

Horace Walpole (1717–1797) is renowned for his creation of the celebrated eighteenth-century Gothic villa Strawberry Hill and as author of the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto (1764). The setting for his artistic and literary pursuits, Walpole’s Gothic Castle and Otranto are both fabrications of his imagination originating in “a head filled like mine with Gothic story” (Correspondence 1, 88). Strawberry Hill is a nexus where the textual and architectural are constructed, and the visual, historical and associative play a seminal role in its conception and interpretation. The building and its contents combined to stimulate the eclectic antiquarian and author to produce narratives and images, fictional and factual, including antiquarian texts such as the

Catalogue of Royal and Noble Authors (1758) and Anecdotes of Painting (1762–1780), the first publication to

define a theory of Gothic architecture, and The History of the Modern Taste in Gardening (1780) chronicling, for the first time, the history and development of English landscape style. Strawberry Hill is probably the most well-documented eighteenth-century house, variously recorded and reproduced in Walpole’s voluminous

Correspondence with in excess of 4,000 extant letters and A Description of the Villa of Mr Horace Walpole … (1774 and 1784),1 the earliest fully illustrated account of a house in Britain. At Strawberry Hill Walpole

devised a plot and storyline articulated through the application of aesthetic theories and picturesque landscape garden concepts designed to stimulate the Pleasures of the Imagination, creating a series of sensory moods

and affective devices to facilitate a new way to “read” and engage with history.2 The literature, architecture and

collection reciprocate, providing the inspiration for Otranto; both are imaginative and creative fictional spaces, symbiotic creations where dramatic Gothic historicised theatrical fantasies originate. Walpole’s antiquarian interests and theoretical model for creating poetic literary spaces rely on the union of fact and fiction and the unmediated tangible relics of the past as discourse to inform a critical historiography and reimagine an alternative vision of history.

As a Member of the Society of Antiquaries, Walpole’s attitude to conventional historical and antiquarian accounts was one of scepticism, expressing the view that textual accounts were a form of fiction: “History is a romance that is believed; romance, a history that is not believed” (Sabor 368). Significantly, he wanted antiquarians to concentrate their efforts on discovering English antiquities, available through archaeological sources, antiquarian prints and narrative accounts. An early advocate of conservation, he complains that “The general disuse of Gothic architecture, and the decay and alterations so frequently made in churches, give prints a chance of being the sole preservatives of that style” (Walpole 1784, i). He was also vociferous about the appropriate type of research for antiquarian pursuit and was contemptuous of contemporary antiquarian research methodologies and publications:

The antiquaries will be as ridiculous as they used to be; and since it is impossible to infuse taste into them, they will be as dry and dull as their predecessors. One may revive what perished, but it will perish again, if more life is not breathed into it than it enjoyed originally. Facts, dates and names will never please the multitude, unless there is some style and manner to recommend them, and unless some novelty is struck out from their appearance. The best merit of the Society lies in their prints; for their volumes, no mortal will ever touch them but an antiquary. (Correspondence 1, 330)

1 Walpole added the following appendices to later editions: c.1786

Appendix; c.1789 Curiosities added; c.1791 More additions. All quotations are from the 1784 facsimile edn (London, 1964).

2 For a full account of Walpole’s application of Joseph Addison’s theories of association and imagination Pleasures of the Imagi-nation published in a series of essays (1712), see Harney.

32

Walpole despised the dry accounts produced by antiquarians expressing a desire to portray the zeitgeist of antiquarian inquiry in wanting to evoke “an idea of the spirit of the times” (Correspondence 2, 300–301). He believed that the material remains of the past possessed the power to evoke a more truthful unmediated sense of history, and he was at the vanguard of a new breed of antiquarianism in that the construction and furnishing of Strawberry Hill embodied the idea of the object as a new kind of historical evidence replacing strictly text-based historiography. Walpole’s premise was that intellectual speculation and association subverted preconceived notions, aesthetic ideas and cultural interests and allowed the observer to directly engage in a subjective, emotional “romantic” dialogue with the story imbued in the object. He also deemed contemporary images more reliable documents than conjectural accounts of buildings or artefacts, and from 1749 the Gothic Castle owed its conception and development to antiquarian printed sources and archaeological and visual encounters with Gothic remains in a series of inspirational “Gothic pilgrimages”. As he declared, “I was the first soul that ever endeavoured to introduce a little taste into English antiquities, and have persuaded the world not to laugh at our Hearne’s and Hollingshed’s” (Correspondence 28, 213).

The antiquarian approach Walpole articulates is evident in his decision to construct Strawberry Hill in Gothic style, in the accumulation and display of the collection and in the Description where he constructed a visual and literary narrative with the intention of making links with English history, people, places and events. Walpole’s notion of enriching interpretation and associational reference through literature, image and description fulfils his desire to make knowledge of the past interesting and accessible by provoking historical imagination. His remarks that he “would breathe life into history” and in his intention to create a “Gothic Museum” (Jesse 177) find their expression at Strawberry Hill where he devised a scheme that permitted the material remains of the past to speak for themselves and narrate their own spontaneous, imaginative history. The observer is led through a complex web of remarkable aesthetic theory, manipulation of presentation, descriptions of provenance, illustrations and associations evoked by the architectural borrowings in the design of the building, its ornamentation and contents, all of which is designed to suggest factual truth.

His statement that Gothic “should be made to imitate something that was of that time, a part of a church, a castle, a convent, or a mansion” (Toynbee 1928, 37) is significant in confirming that his continual references to Strawberry Hill as an “abbey”, “cloister”, “castle” or mansion are to emphasise that its architectural elements are imitated from either original Gothic buildings that he had seen or copied from printed antiquarian design sources. He believed that his concept of Gothic as manifest at Strawberry Hill was an appropriate use of authentic Gothic applied to a diminutive private dwelling, supposedly built on monastic foundations (Harney 118–119).

Significantly, he remarked to John Pinkerton (1758–1826), the Scottish antiquarian that “Gothic style seems to speak an amplification of the minute, not a diminution of the great” as his architectural borrowings were inevitably produced at a compressed scale (Pinkerton II, 59).

The pleasure gained from recalling the past through association and imaginative engagement was the main reason Walpole chose Gothic for Strawberry Hill:

I, who have great difficulty of not connecting every inanimate thing with the idea of some person, or of not affixing some idea of imaginary persons to whatever I should see, should prefer that building that

furnished me with most ideas, which is not judging fairly of the merit of the buildings abstractedly. And for this reason, I believe, the gloom, ornaments, magic of the hardiness of the buildings, would please me more in the Gothic than the simplicity of the Grecian. (Walpole 1759, 52)

For Walpole “Beautiful Gothic architecture” of the early-fifteenth century is the only “true” English archi-tecture and it is largely from this period that he takes Gothic architectural quotations, features, characteristic and decorative ornament, mainly from tombs, oratories and small chapels. Strawberry Hill expresses the idea that the Gothic Castle was based on monastic foundations and it seems certain that his preference for Gothic sprang, in part, from his belief that abbots were their own architects and created atmospheric interiors through creating “vaults, tombs, painted windows, gloom and perspective” which “infused such sensations of romantic devotion” (Walpole 1762–1780, 94).

He carefully selected Gothic vocabulary copied or imitated from authentic sources and original models such as the Lady Chapel at Gloucester Cathedral: “[…] But of all delight, is what they call the abbot’s cloister. It is the very thing that you would build, when you had extracted all the quintessence of trefoils, arches, and lightness. In the church is a star-window of eight points, that is prettier than our rose-windows” (Correspondence 35, 154).

A collection of remarkable visual sources, most solicited by Walpole who conceded that illustration had the power to supplement and enrich scenes that had only been loosely sketched out in his literary imagination, reveal subtleties in their iconography expressing a nuanced reading of how the castle and collection are linked as unified forms of display. They demonstrate the way in which the house museum successfully combined the visual and the descriptive to challenge and disrupt conventional narrative accounts of visitor experience and museum display. Although the published version of Walpole’s carefully constructed Description of the Villa (1774) and the extra illustrated version (1784) were not available to visitors during his lifetime, in the interplay of text and image they contextualise and help us to understand how the building, the collection and the various rooms are meant to be interpreted. Although Walpole is not explicit in stating how the rooms should be “read” in the Description he refers to it as an “illustration” suggesting the text is a pictorial narrative providing enough visual and textual information to ignite the imagination of the observer.

These visual and narrative accounts Walpole authored of the Gothic Castle and its collection illustrate how he created an alternative museum for the imagination that moved away from the conventional reconstruction of history through inanimate display and instead gave primacy to images, objects and artefacts brought together in a cabinet of curiosities where their associative qualities and imaginative connections told their particular story. John Locke (1632–1704) compared the mind to a cabinet and collecting, in the sense of the physical museum or the metaphorical “furnishing the empty cabinet of the mind”. The idea of filling the space of the imagination with visual images and impressions was a vital Enlightenment trope (Silver 14).

Strawberry Hill offered a heterogeneous alternative method of preserving the past in which the observer actively participated in generating image meaning and narrative. Taken together their historic legacy engendered genealogical, dynastic and ancestral lineage which for Walpole generated a sense of patriotism, nationhood and national identity that were inextricably linked to his sense of identity. This analysis focuses on how the house, collection, and images were conceived and displayed to narrate a particular view of history through

34

Gothic architectural quotations largely from the reign of Henry VIII up to the Civil War (1642–1651), which Walpole considered the most significant period in English history. Using architectural fragments and material remains, Walpole commemorated memorable people and significant events of the period through association, linking them to his own story.

In a remarkable document titled Walpole’s Account of the Aesthetic Effects at Strawberry Hill (1772) he explains how, through the application of this theory he developed to create different moods, impressions and

sensations can be used to stimulate the observer:3 “Great effects may be produced by the disposition of a

House, & by studying lights & shades, and by attending to a harmony of colours. I have practised all these rules in my house at Strawberry Hill, & have observed the impressions made on Spectators by these arts” (Walpole MS13–1947).

These innovative concepts include asymmetrical planning, varying levels and scale, the use of colour, light and shade, and framing and concealing to create a sense of movement, surprise and expectation as the visitor moved through the small dark spaces of the original house to light, expansive interiors created in the later accretions. The succession of dynamic spatial experiences is designed to give the impression that the building developed over centuries starting from monastic foundations with later additions mostly of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as the Tudor and Stuart periods held a particular fascination for him (Harney 160).

The specially-commissioned illustrations of the mansion and its interior that accompany the text of the extra-Illustrated edition of the Description of the Villa are crucial to the interpretation of the historicised interior and our understanding of how Walpole wanted the villa to be perceived. Emphasis is placed on historicising the Gothic Castle through Gothic symbols, incorporating quintessential Gothic vocabulary associated with castles and ecclesiastical or monastic buildings, such as crenellations, battlements, pinnacles, trefoils, pointed arches, tracery, fretwork, stained and painted glass and nomenclatures for rooms signifying historical medieval associations. The atmosphere he wished to convey was achieved through his design aesthetic often using artifice and deceptive devices such as historicised portraiture in the style of the great masters; chiaroscuro for dramatic effect; trompe-l’œil and constantly changing perspectives to create optical illusion; papier-mâché and lath and plaster instead of stone for structure; carved wood painted stone-colour to give the impression of stone construction; scagliola imitating marble; transposing and reimagining replications and copies of medieval monuments in diminutive scale using modern materials; fragments of stained glass and other spolia incorporated into the fabric or display, all “pretending to an observance of the costume even in the furniture [of the Middle Ages]” (Walpole 1784, iii).

In a letter to his friend Montagu, written during the early stages of construction, Walpole makes clear his intention of creating a fictive history for the site with his reference to creating the impression of an ancestral

building in referring to “the castle (I am building) of my ancestors” (Correspondence 9, 192). Inviting Thomas

Warton (1728–90), Professor of Poetry at Oxford, to pay a visit, Walpole alludes to the fictive quality of his Gothic fabrication, linking this to antiquarian literature, the Castle of Otranto and his establishment of the first private printing press with the first English printing press. Walpole tells Warton: “You would find some attempts at Gothic, some miniatures of scenes which I am pleased to find you love – cloisters, screens, round

3 The title appears to have been a later addition to the MS as “aesthetic” is a nineteenth-century German term.

towers, and a printing house, all indeed of baby dimensions, would put you a little in mind of the age of Caxton and Wynken. You might play at fancying yourself in a castle described by Spenser” (Correspondence 40, 255).

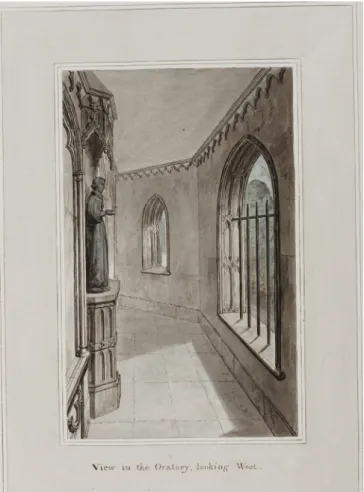

Creating three-dimensional effects, impressions of depth and sensations of mood through light and shade, perspective and grouping, monochromatic schemes contrasted with colours in order to achieve atmosphere, variety and a sense of revelation, Walpole is “imprinting the gloomth of abbey’s and cathedrals on one’s house” (Correspondence 20, 372). Transitions between “gloomth” and light, openness and enclosure, circuity and directness, all conspired towards providing a series of framed views and incidents designed to construct an association between object and subject, performer and audience to emotionally engage the observer in an affective sensory experience.

Visual sources, many commissioned by Walpole from a range of artists, including Johann Heinrich Müntz (1727–1798), Paul Sandby (bap. 1731, d. 1809), John Carter (1748–1817) and Edward Edwards (1738–1806), document the architectural development of the Gothic Castle and illustrative strategies Walpole used to convey the specific impression he wants to portray, asking of Müntz, “Can he paint perspectives, and cathedral aisles, and holy glooms?” (Correspondence 35, 186). Many images of Strawberry Hill were in circulation documenting the picturesque setting, the development of the building and the collection, and Walpole collected them for inclusion in the extra-illustrated edition of the Description and various portfolios. Many accentuated architectural details, particular features and dramatised the approach to the villa, and Walpole himself encouraged and promoted visions of the house as a monastery. Combined with the Description of the

Villa they give a rich textual and visual intertextuality of his means of preserving the past through complex

representations of the Gothic Castle, its interiors, 4,000 artefacts, 12,000 prints and in excess of 7,000 books

36

that decorated the rooms, mixing fact, fiction, text and image to create a carefully constructed journey through history, breathing life into the mainly British and European works of art and artefacts. “Portraits of remarkable

persons,”hung in every room in the mansion alongside Walpole family members signifying their place in

history (Walpole 1784, ii). Acknowledging the commemorative associative function of portraiture he wrote that, “I prefer portraits, really interesting, not only to landscape painting, but also to history […] a real portrait we know is truth itself: and it calls up so many collateral ideas, as to fill an intelligent mind more than any other species” (Pinkerton 1, 26).

Ancestry, genealogy, and lineage, are articulated through design, decoration, historicised portraiture, Gothic fragments and artefacts. Original seventeenth-century furniture was supplemented by modern ebony furniture in antique style with chairs designed in ecclesiastical Gothic based on medieval lancet windows casting illusionistic shadows. The intermingling of old and new in historically themed transitional architectural spaces was innovative and unique. In this tongue-in-cheek comment it is evident that the overall concept from the outset was to convince the observer that they were viewing an ancient structure regarding the construction of the Tower: “[…] I am waiting for Mr Essex to finish my new tower, which, as my farmer said, is still older than the rest” (Correspondence 32, 320).

The Description describes every room and its contents, including “principal curiosities”; in detail, however a brief tour through some of the architectural spaces demonstrates how Walpole used innovative aesthetic concepts to stimulate the pleasures of the imagination induced through association. The textual and illustrative accounts of the approach to the Gothic Castle, the entrance and a brief description of a few of the historicised rooms set the tone, mood and narrative and give an insight in what he wished to convey.

The emphasis on the picturesque Gothic Castle’s contrived monastic foundations is immediately apparent on “the approach to the house through lofty trees, the embattled walls overgrown with ivy, the spiry pinnacles, the grave air of the building, give it all the appearance of an old abbey” (Ferrar 1795). Nomenclatures and decorative Gothic features illustrate its supposed links to historical people and events and enhance the notion that Strawberry Hill was built on fragmentary ruins from the Dissolution of the Monasteries subsequently incorporated into an ancestral home. An architectural quotation from a Jacobean prodigy house – “the embattled wall to the road is taken from a print of Ashton house in Warwickshire, in Dugdale’s history of that county” – emphasises its accretive nature (Walpole 1784, 2). The wall also enclosed and sheltered the “Prior’s” garden setting the scene for the Gothic interior of the “Abbey” with three “shields of Walpole, Shorter and Robsart”, signifying the ancestral home of the Walpole family.

A lancet arched door leads to the Winding Cloister: “From hence under two gloomy arches you come to the hall and staircase, which it is impossible to describe to you, as it is the most particular and chief beauty of the

castle”(Correspondence 20, 379–380). Walpole’s Description confirms that the hall was designed to exhibit

contrasting effects outlined in his aesthetic theory: “With regard to light and shades. The first Entrance strikes by the gloom: the Staircase opens upwards to a greater light” (Walpole MS13–1947).

Six Gothic doors gave the illusion that the building is much larger than it actually is and this perception

is enhanced by an ambience of “gloomth”, with grey trompe-l’œil effect wallpaper enriching the illusory

mysterious quality. The complex “history” further embellished through literary references to the hall as the “Paraclete”, a quotation from Pope’s popular Gothic poem Eloisa To Abelard (1717): “I was going to tell you that my house is so monastic that I have a little hall decked with long saints in lean arched windows and with taper columns, which we call the Paraclete, in memory of Eloisa’s cloister” (Correspondence 20, 372).

38

The ancestral and ecclesiastical themes are illustrated and reinforced by the placement of decorative elements such as heraldry and stained glass throughout the Gothic Castle. “‘The armoury bespeaks the ancient chivalry of the lords of the castle, and I have filled Mr Bentley’s Gothic lanthorn with painted glass, which casts the most venerable gloom on the stairs which was ever seen since the days of Abelard: “Lost in a convent’s solitary gloom!’” (Pope 1983). Walpole continues, “The lanthorn itself in which I have stuck a coat of the Veres is supposed to have come from Castle Henningham” (Correspondence 9, 149), is intended to convey associative links to John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford (1442–1513), a significant military commander in the Wars of the Roses who helped win the campaign at the Battle of Bosworth Fields, a defining moment in English and Welsh history which effectively ended the Plantagenet dynasty and signified the commencement

of the Tudor dynasty. Visually and imaginatively it is also associated through the trompe-l’œil wall decoration

copied from screen of the tomb of Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales (1486–1502), first son of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York (1466–1503), who died before his father and never became king. One of his godfathers was John de Vere, whose family arms appear on the lamp.

Many of the chimneypieces are taken from tomb architecture such as that in the Little Parlour modelled on Bishop Ruthall’s (d.1523) tomb (Walpole 1784, 15), surmounted by Walpole’s arms expressing lineage with the House of Tudor as Ruthall was in the service of Henry VII and Henry VIII. Ruthall served alongside Wolsey and was much involved in preparations for the defence of England when James IV (1473– 1513) of Scotland threatened war (DNB).

“The green closet is all light and cheerfulness within & without” (Walpole MS13–1947), with double-aspect windows containing “some very curious pieces of painted glass […] with the arms of England and those of Henry VIII entwined with Catherine of Aragon” (Walpole 1784, 23). It also had an image of Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583–1648), a chivalric knight whom Walpole greatly admired; he had written the preface and printed his biography at Strawberry Hill (Correspondence 20, 379–380).

Emerging into a top-lit staircase the diminutive Armoury is revealed, evoking a medieval concept that is a prime example of Walpole constructing a complex fiction implying that his ancestor fought in the crusades. A miniature recreation of a Gothic baronial hall, the collection of armour and weapons further enhanced the idea of an ancient medieval house. There are Gothic arches, Walpole’s armorial quarterings and ancestors painted on the walls displaying links to the crusades, Tudors and Royal dynasties, with arms “all supposed to be taken

by Sir Terry Robsart [1464–?] in the holy wars”( Correspondence 20, 379–380).4

Walpole acquired weapons and other objects suitable for display in the niches on the staircase, culminating in 1771 with a suit of Francis I’s (1494–1547) armour to enhance its baronial posturing as an ancient display of combat armour. This later acquisition most obviously connects with the Tudor theme as the French king had attempted to negotiate an alliance with Henry VIII on the Field of Cloth of Gold in 1520; however, retrospectively it made a subtle visual association of the Gothic villa as the inspiration for the fictional Castle

of Otranto (Correspondence 1, 243).

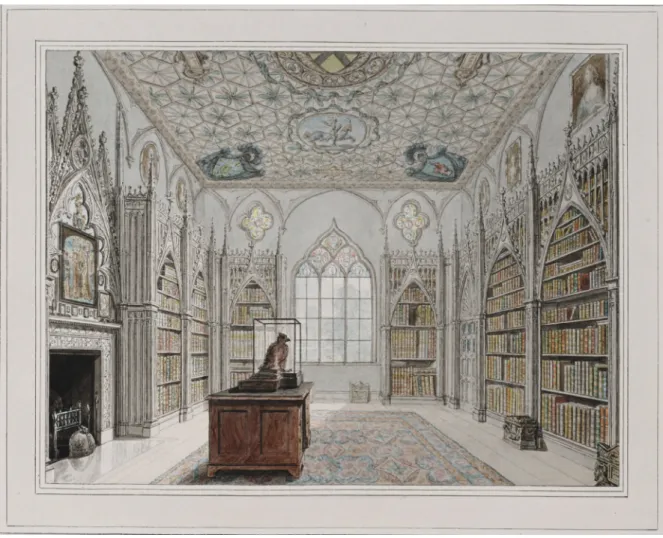

4 Robsart was Walpole’s most romantic maternal ancestor discovered in his genealogical researches. Fig. 5. The Library, J. Carter

40

Enhancing the monastic conceit the Library is architecturally the most accomplished and sustained essay in Gothic, suggesting the monastic scholarship of an abbey. In this impressive space the design brought together three great ecclesiastical buildings, using architectural quotations from Canterbury Cathedral, Old St Paul’s and Westminster Abbey. The iconography, decorative scheme, furnishings, books, painting and statuary made significant statements regarding the status and aspirations of its creator. Walpole is proclaimed as scholar, collector, connoisseur and antiquarian with the extensive book collection, including the Wenceslas Hollar prints, used for the design of the library, all “arranged within Gothic arches of pierced work, taken from a side-door case to the choir in Dugdale’s St Paul’s” (Walpole 1784, 33).

Walpole’s claimed lineage, personal history and links to other royal and national histories were made through architecture, decorative elements and portraiture. English kings were represented, portraits of Henry VI, Henry VIII, and the first Stuart King, James I were juxtaposed alongside Walpole’s family portraits, linking their history with kingship. The windows also contained the largest display of stained and painted glass including, “a large shield of the arms of England”, and shields of Prince Arthur, first son of Henry VII from New College, Oxford and the Roses of York and Lancaster, a layer that celebrates Tudor history, as in other rooms (Walpole 1784, 34). Charles I and II, Royal Coats of Arms and knights in roundels are also displayed in the heraldic glass amid colours associated with heraldry. Classical antique and other objects decorated the room, including a clock, “a present from Henry 8th. to Anne Boleyn [1501–1536] […] on the top sits a lion holding the arms of England, which are also on the sides”, with Walpole’s extensive collection, including rare books and prints lining the walls (Walpole 1784, 36). The principal part of the heraldic ceiling was a visual representation of his pedigree in chiaroscuro with the family motto, Fari quæ sentiat; “to say what one feels”, prominently displayed in Latin, “at the ends, M.DCC.LIV, the year in which the room was finished, expressed in Gothic letters: the whole on mosaic ground” (Walpole 1784, 33–34).

Walpole’s Blue Bedchamber, from which he had his dream vision, in June 1764, that “on the uppermost banister of a great staircase I saw a gigantic hand in armour”, partly inspired the Castle of Otranto (Correspondence 1, 88), had a copy of the Magna Carta and the death warrant of Charles I by the bed. The stained glass too recalled the significant figure of Anne Boleyn, the first English queen to be executed, recalling the Act of Supremacy (1534) and subsequent legislation which resulted in the English Reformation

with Henry VIII’s declaration as Head of the Church of England.5

The Star Chamber, named after the original which was used as a court to exercise jurisdiction over the landed gentry and other prominent people, is characterised by “gloomth” exuding an air of confinement and restriction. Walpole explicitly states that the intention is that, “The Star:chamber and dusky passage again prepare for you for solemnity” (Walpole MS13–1947). Walpole placed a bust that he believed to be of Henry VII in agony in the chamber; he was responsible for replacing the royal council with the Court of the Star Chamber.

From the enclosed, inquisitorial overtones of the Star Chamber, “a trunk-ceiled passage, lighted by a window of painted glass” fuel the mood of interment before entering the Holbein Chamber which evokes and celebrates the Tudor Court of Henry VIII and associated English history. Emanating a purple glow, “[…]

5 Anne Boleyn was Mother of Queen Elizabeth I and second wife of King Henry VIII of England.

the Holbein-chamber softens that Idea, yet still maintains a grave tone; for the whole is a kind of Chiaro Scuro”, a contrasting and surprising revelation after experiencing the dark trunk-ceiled passage (Walpole MS13–1947). The iconography of the room of heraldic motifs from Walpole’s arms, the crosslet, Saracen’s head and Catherine wheel associate him with the royal display. The bed was originally intended to come from Burghley, the Tudor mansion built by Queen Elizabeth’s chief adviser and Lord High Treasurer, Sir Henry Cecil (1521–1598). Walpole also purchased a thirteenth-century chair from Glastonbury Abbey to enhance the ancient effect: “I am deeper than ever in Gothic antiquities; I have bought a monk of Glastonbury’s chair full of scraps of the psalms, and some seals of most reverend illegibility. I pass all my mornings in the thirteenth century, and my evenings with the century that is coming on” (Correspondence 35, 107).

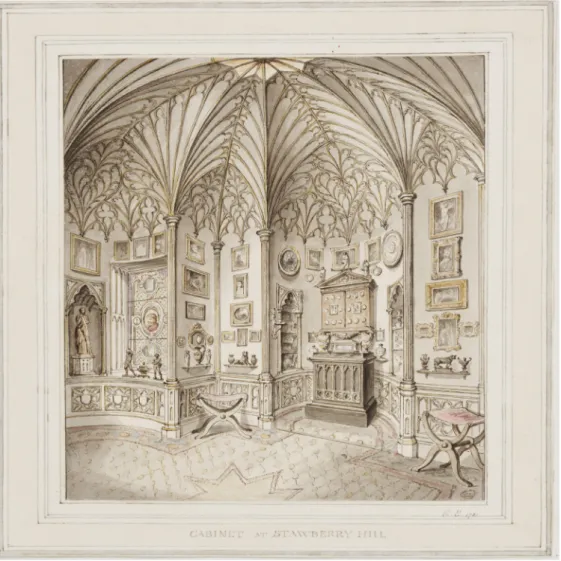

Entered or viewed from the dazzling “new Gallery, wch is all Gothicism, & gold, & crimson, & looking-glass” (Gray 2, 373), the Tribune named for the Tribuna room of treasures at the Uffizi in Florence with its heterogeneous collection was viewed through a Gothic grated door, painted to resemble ironwork.

The stone-coloured vault with gold ornament is said to be taken from the Chapter House at York Cathedral but the flowering tracery is derived from the west window of York, the tracery is made of papier-mâché (Correspondence 33, 575). The pattern for the niches is, like those in the Gallery, taken from Müntz’s drawing of the north door of St Albans, the medieval chapel-effect, created through the use of a yellow stained glass star-shaped moon-strip located in the ceiling, “throws a golden gloom all over the room” (Walpole 1784, 55),

42

conveying an atmosphere “that is to have all the air of a Catholic chapel – bar consecration” (Correspondence 21, 306). The illustration by Edwards is misleading in terms of size and scale depicting the room as being significantly larger than the 16 feet across that it actually is. Neither does it realistically portray the fantastic quantity of objects displayed or reveal the sense of clutter that must have characterised the space (Harney 161).

The Great North Bedchamber alludes to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century equivalents in ancient great houses. Meant for contrast, “The sobriety of the Chapel, & the idea of having seen all the House, make the opening of the great bedchamber the more surprising, from its not being expected, & from the striking contrast between the awe impressed by the Chapel, & the gush of light, gaudiness & grandeur of the bedchamber” (Walpole MS13–1947). Portraiture and iconography evoke the House of Tudor and English history. Objects included a spur worn by William III at the Boyne and a pair of gloves worn by James I in addition to the “speculum of kennel coal […] used to deceive the mob by Dr Dee, the conjurer in the reign of queen Elizabeth” (Walpole 1784, 77).

It is by now apparent that Walpole did not fit into the stereotypical model of the eighteenth-century antiquarian author and collector. Strawberry Hill is unique in having an intellectual and aesthetic idea behind the sequence of theatrical stage sets and museum quality, historically-themed rooms with their carefully contrived iconography, ornament and display bringing to life the material remains of the past and stimulating the imagination of the spectator through their links to history. The singularity of his creation, the villa and his collection is a manifestation of the range of his interdisciplinary interests. In many ways Walpole was defined by Strawberry Hill and his considerable collection which represent his heterogeneous tastes and sensibility and are inextricably linked to his notion of national and personal history and his place in it.

Strawberry Hill was the first purpose-built antiquarian “museum” interior, a sequence of theatrical spaces that played with scale, atmosphere and colour as a background to his collection of objects, all “singular”, “unique”, or “rare” (Harney 4). In creating the Gothic Castle and interior Walpole pioneered a shift from purely epistemological processes which were text-led and text-driven to display a living narrative and to illustrate a counter-history that disrupted the hitherto traditional accounts of historians. Emphasising alternative narratives and innovative visual display, Walpole successfully combines architecture and museology through an affective and effective display of the fragments of the past incorporated into the fabric of the new Gothic building and exhibited throughout the house museum.

The creation of atmosphere and mood through aesthetic effects was central to the ability to stimulate the imagination in evoking the “enchantment and fairyism, which is the tone of the place” (Correspondence 10, 72). Walpole’s handling of the interior is designed to create a theatre of the imagination through the forming of innovative architectural spaces, creating atmosphere through lighting and themes achieved with a range of theatrical devices to stimulate imaginative and associative pleasure. His aesthetic theory was used to animate the display and create theatrical effects, which combined the commemorative aspects of his life, his varied interests, and his architectural and literary achievements in an atmospherically historicised space. He transformed a domestic interior into a veritable cabinet of curiosities, a concept emphasised by its diminutive scale and his continual references as “a little play-thing” and a “bauble”, which confirm that from its inception he visualised it as a place of pleasure and entertainment (Correspondence 37, 269–270).

The building and its collection are inseparable and Walpole’s mission was to record these as his memorial and to serve as a model for others that might be tempted to recreate the “beautiful Gothic” or a house museum interior. His antiquarian research and Gothic pilgrimages enabled him to produce a picturesque ensemble capable of stimulating the imagination. With the creation of Strawberry Hill Walpole desires posterity to recall him as the amateur architect who surpassed all previous attempts at reproducing correct English Gothic. He wanted to be remembered as the arbiter of taste for reviving the Gothic style equivalent to the way Burlington was credited for the Palladian Revival: “As my castle is so diminutive, I gave myself a Burlington-air, and say, that as Chiswick is a model of Grecian architecture, “Strawberry Hill is to so of Gothic” (Correspondence 20, 361–362).

At Strawberry Hill the faculty of the imagination was given primacy over that of intellect; the house is a fusion of history and fiction, the visual and the sensory, an architectural palimpsest fabricated from the semantics of Gothic, where the accumulation of parts stood for the whole. Walpole was interested in the form and visual language of Gothic architecture and his “little Gothic castle” established a sense of history and lineage and he was centre-stage in this theatre of the imagination. It was based on a fiction, an elaborate theatrical conceit that was both pleasurable and entertaining (Harney 277).

However, he never lost sight of its fictional qualities and textual origins declaring “I am no poet, and my castle is of paper, and my castle and my attachment and I, shall soon vanish and be forgotten together” (Correspondence 33, 42–43).Walpole’s final words in the preface to the Description of the Villa emphasise the importance of the fictive Gothic Castle and the role of fiction as a source of pleasure and inspiration:

[…] could I describe the gay but tranquil scene where it stands, and add the beauty of the landscape to the romantic cast of the mansion, it would raise more pleasing sensations than a dry list of curiosities can excite: at least the prospect would recall the good humour of those who might be disposed to condemn the fantastic fabric, and to think it a very proper habitation of, as it was the scene that inspired, the author of the Castle of Otranto (Walpole 1784, iv).

References

Manuscript Sources

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, MS13–1947. Walpole, Horace. 1772. Account of the Aesthetic Effects at

Strawberry Hill.

Lewis Walpole Library MS. Walpole, Horace. 1759, 1771, 1786. Books of Materials.

Books

Addison, Joseph. 1837. The Works of Joseph Addison: Complete in Three Volumes: Embracing the Whole of

44

Davis, Herbert, ed. 1983. Pope: Poetical Works. London: Oxford University Press.

Dictionary of National Biography. http://www.oxforddnb.co

Ferrar, John. 1796. Tour from Dublin to London, in 1795, through the Isle of Anglesea, Bangor, Conway …

and Kensington. Dublin.

Harney, Marion. 2013. Place-making for the Imagination: Horace Walpole and Strawberry Hill. Farnham: Ashgate.

Jesse, John Heneage. 1882. George Selwyn and His Contemporaries. 4 vols. London: Bickers & son.

Lysons, Daniel. 1792–1796. The Environs of London, Being an Historical Account of the Towns and Villages,

and Hamlets within Twelve Miles of the Capital … with Biographical Anecdotes and Plates. 4 vols.

London: T. Cadell.

Sabor, Peter, ed. 1998. The Works of Horatio Walpole, Earl of Orford, 1798. From the 1798 edition. 5 vols. London: Pickering & Chatto.

Silver, Sean. 2008. The Curatorial Imagination in England, 1600–1752. PhD thesis. Los Angeles: University of California.

Toynbee, Paget, ed. 1928. “Horace Walpole’s Journal of Visits to Country Seats”. Transactions of the Walpole

Society. Annual 16. London: Walpole Society.

Toynbee, Paget and Leonard Whibley, eds. 1935. The Correspondence of Thomas Gray. 3 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Walpole, Horace. 1784. A Description of the Villa of Horace Walpole, Youngest Son of Sir Robert Walpole,

Earl of Orford, at Strawberry Hill, near Twickenham. With an Inventory of the Furniture, Pictures, Curiosities etc. Twickenham: Strawberry Hill Press. Fascimile edn., 1964. London.

—. 1762–1780. Anecdotes of Painting in England and a Catalogue of Engravers. 5 vols. Twickenham: Strawberry Hill Press.

—. 1764, dated 1765. The Castle of Otranto, A Story. Translated by William Marshal, Gent, From the Original Italian of Onuphrio Muralto, Canon of the Church of St. Nicholas at Otranto. London: J. Dodsley. —. 1764. The Life of Lord Edward Herbert of Cherbury (Preface). Twickenham: Strawberry Hill Press. —. 1805. Walpoliana. Compiled by John Pinkerton. 2 vols. London: R. Phillips.

—. 1937–1983. The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence. Ed. W.S. Lewis et al. 48 vols. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Marion Harney is Senior Lecturer in Conservation, Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering,

University of Bath. An architectural and landscape historian specialising in conservation and research ed-ucation, her book Place-making for the Imagination: Horace Walpole and Strawberry Hill (Ashgate, 2013) won the J. B. Jackson Award 2015. Sole researcher for Bath: Pevsner Architectural Guides (Yale University Press, 2003), Marion’s recent publications include, Gardens and Landscapes in Historic Building

Conserva-tion (ed.) (Wiley-Blackwell, 2014); the concluding chapter, ‘Conserving Britain’s Ruins, 1700 to the Present

Day ‘ in Reading Architecture Across the Arts and Humanities: Writing Britain’s Ruins, 1700-1850 ( British

Library, 2017) and ‘Genius loci restored: the challenge of adaptive re-use’, ( EAAE Thematic Network on Conservation Workshop V, 2017).