The Knight, the Lady, and the Poet: Understanding Huon of Oisy’s Tournoiement des Dames (c. 1185-1189)

Texte intégral

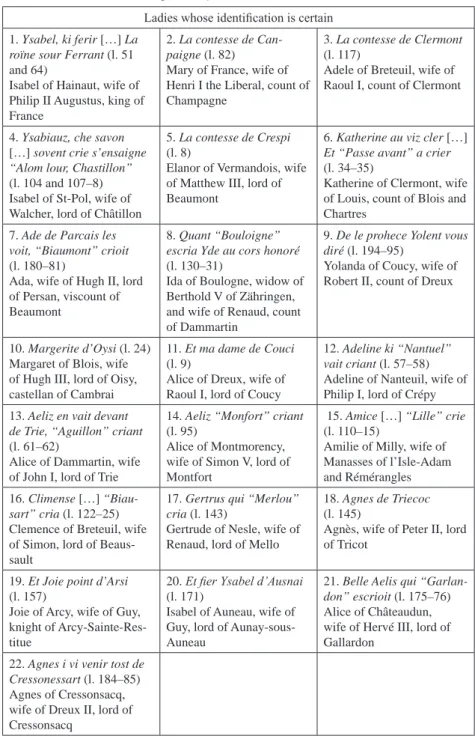

Figure

Documents relatifs

De l’importance de distinguer le populisme du nationalisme et d’analyser leurs liens Les liens entre le populisme et le nationalisme, selon nous, revêtent une importance majeure non

Prevalence of anxiety and depression among medical and pharmaceutical students in Alexandria University. Alexandria Journal of Medicine Volume 51, Issue 2 , June 2015,

Bien qu’apparemment défavorable, le balayage du bassin versant par le système pluvieux a été trop rapide par rapport aux vitesses de propagation des écoulements dans le cours du

place under the reader’s eyes as soon as he or she tries to trace a coherent system of ideas in Hardy’s thought as it is expressed in the poems, especially in Poems of the Past and

The results are used to prove to the existence of solutions to the random system of fractional di erential equations , then we shall be concerned with the existence and uniqueness

There is also from this time Descartes' first statement of the "creation of eternal truths", in a letter to Mersenne, 15 April 1630: "In my treatise of physics I

In the 14 th century, the Virgin is clearly clothed in episcopal garments, for example in Macedonia in the Church of the Virgin in Treskaveč (c.1340) and at the monastery of

The Temporary Administration Measures for the Verifi cation and Approval of Overseas Investment Project provides that “overseas invest- ment” refers to investment