R E V I E W

Open Access

Diagnosis, treatment, and response

assessment in solitary plasmacytoma:

updated recommendations from a

European Expert Panel

J. Caers

1*, B. Paiva

2, E. Zamagni

3, X. Leleu

4, J. Bladé

5, S. Y. Kristinsson

6, C. Touzeau

7, N. Abildgaard

8, E. Terpos

9,

R. Heusschen

1, E. Ocio

10, M. Delforge

11, O. Sezer

12, M. Beksac

13, H. Ludwig

14, G. Merlini

15, P. Moreau

7,

S. Zweegman

16, M. Engelhardt

17and L. Rosiñol

5Abstract: Solitary plasmacytoma is an infrequent form of plasma cell dyscrasia that presents as a single mass of monoclonal plasma cells, located either extramedullary or intraosseous. In some patients, a bone marrow aspiration can detect a low monoclonal plasma cell infiltration which indicates a high risk of early progression to an overt

myeloma disease. Before treatment initiation, whole body positron emission tomography–computed tomography

or magnetic resonance imaging should be performed to exclude the presence of additional malignant lesions. For decades, treatment has been based on high-dose radiation, but studies exploring the potential benefit of systemic therapies for high-risk patients are urgently needed. In this review, a panel of expert European hematologists updates the recommendations on the diagnosis and management of patients with solitary plasmacytoma.

Keywords: Solitary plasmacytoma, Extramedullary plasmacytoma, Myeloma, Plasma cell dyscrasia, PET/CT, MRI, Radiotherapy

Background

Plasma cell (PC) neoplasms can present in different clin-ical forms. Multiple myeloma (MM) is generally located in the bone marrow (BM) and associated with a wide spectrum of clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings [1]. Conversely, solitary plasmacytoma (SP) is character-ized by a single mass of clonal plasma cells, with no or minimal BM plasmacytosis and with no other symptoms than those derived from the primary lesion. It can present either as extramedullary (extraosseous) plasma-cytoma (EMP), i.e., in soft tissues, or as solitary bone plasmacytoma (SBP). SP is a rare condition with a cu-mulative incidence of 0.15/100.000 [2]. Liebross et al. reported that out of 1354 patients treated for plasma cell neoplasms at the MD Anderson Cancer Center between 1963 and 1996, 1272 patients (94%) had MM, 60 pa-tients (4%) had SBP, and 22 papa-tients (2%) had EMP [3].

A recent Swedish population study showed a similar dis-tribution of patients, with a global incidence of 0.191/ 100.000 for male and 0.090/100.000 for female patients [4]. SBP comprises 70% of all SP cases and occurs pri-marily in red marrow-containing bones such as verte-brae, femurs, pelvis, and ribs. EMP can involve any site or organ, with the most frequent being the head and neck region (sinuses, naso- and oropharynx), gastro-intestinal tract, and lungs [3, 5]. Patients presenting with SBP, especially those cases with minimal BM plasmacy-tosis, have a higher risk of developing symptomatic MM: approximately 50% of patients with SBP and 30% of patients with EMP develop MM within 10 years after the initial diagnosis [6]. Here, we provide a consensus statement on the diagnostic criteria, prognostic factors, treatment, and response criteria for SP. Readers should be aware that the management of patients with localized or solitary plasmacytomas is different from patients with soft-tissue plasmacytomas in the context of overt multiple myeloma.

* Correspondence:jo.caers@chu.ulg.ac.be

1Department of Hematology, CHU de Liège, Liège, Belgium Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s). 2018 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Methodology

These guidelines were developed by a working group of clinical hematologists with expertise in MM. Literature review was performed up to September 2017 and in-cluded published clinical studies, meta-analyses and re-views (Medline), and abstracts from the American Society of Hematology (ASH) and European Hematology Association annual meetings (keywords: plasmacytoma, solitary, myeloma, PET/CT, MRI, radiotherapy, diagno-sis, and treatment). Key recommendations were devel-oped based on randomized, controlled clinical trial evidence. If data were insufficient, expert consensus was used to suggest recommendations. The drafted recom-mendations were circulated among the working group members who all provided comments. In addition, the recommendations were discussed by working group members at the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG), European Myeloma Network (EMN), and ASH meetings. After three rounds of revisions, all work-ing group members reviewed and validated the final recommendations which were assigned using the GRADE criteria, which incorporate recommendation strength and quality of evidence (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Definition and diagnostic criteria

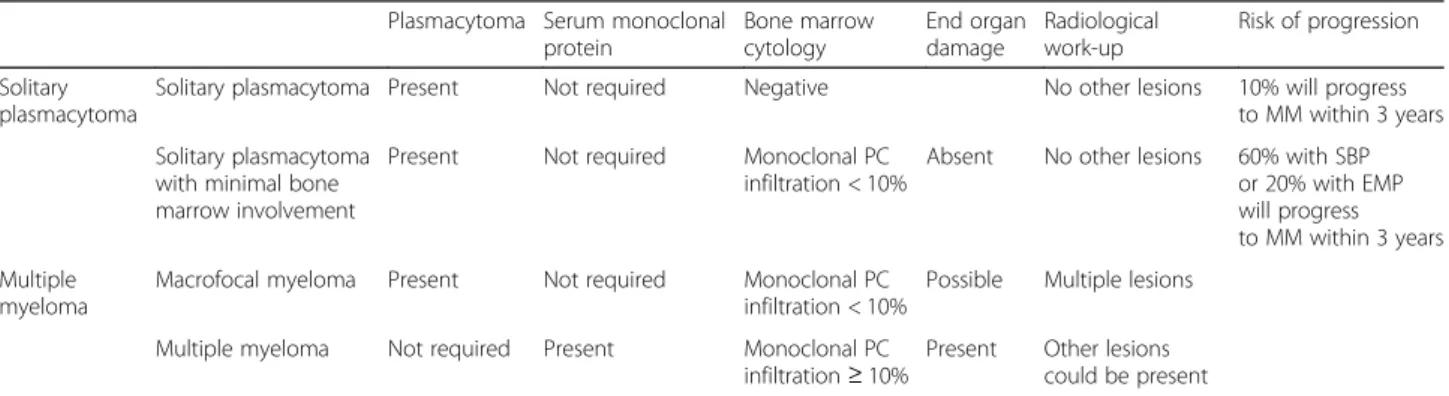

The advent of more sensitive techniques to assess BM plasmacytosis has recently led to an updated definition of SP by the IMWG [1]. SPB is defined by the presence of a single lytic lesion due to monoclonal PC infiltration, with or without soft-tissue extension, and EMP consists of a soft-tissue mass that is not in contact with bone [7]. Accordingly, conventional morphology or immunohisto-chemistry typically show no BM plasmacytosis, but min-imal BM infiltration by clonal plasma cells (PCs < 10%) was still considered consistent with a SP diagnosis, pro-vided that no other lesions are observed (Table 1).

SP diagnosis is currently based on a tissue biopsy and histological and immunohistochemical confirmation of the presence of a homogenous infiltrate of monoclonal plasma cells, which typically express CD138 and/or

CD38. Monoclonality needs to be proven by kappa/ lambda light chain restriction or by a PCR-based ap-proach. Cytogenetic analysis of the SP generally identi-fies the abnormalities that are frequently encountered in MM. Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was realized in 2 small studies on EMP and iden-tified a high incidence of 13q losses (ranging from 33 to 40%), IGH rearrangements (in about 37 to 53%), and hyperdiploidy in 54% of the cases [8, 9]. However, no prognostic correlation could be found between chromo-somal aberrations and clinical features or disease progression [8].

Two independent studies detected low levels of clonal PCs in the BM by using more sensitive methods (i.e., flow cytometry) [10, 11]. Hill et al. demonstrated in 50 patients with SBP that occult BM disease, defined as a discrete population of phenotypically aberrant PCs, is present at diagnosis in 68% of patients. Importantly, the presence of such aberrant cells had prognostic signifi-cance, since progression to symptomatic MM or a new plasmacytoma outside the irradiation field was docu-mented in 72% (26/34) of these patients with occult disease vs. 12.5% (2/16) in patients without and the me-dian time to progression was 26 months vs. not reached. Furthermore, Paiva et al. reported that 17 of 35 (49%) of patients with SBP had aberrant BMPCs [11]. Of interest, 71% of patients with positive flow cytometry evolved to MM vs. only 8% of those with negative flow. This suggests that flow cytometry may be helpful in the dis-tinction of the true SBP (negative flow cytometry) with a very low rate of evolution to MM from those with high risk of progression to myeloma (positive flow cytometry). Both studies confirm that SP patients with minimal BM plasmacytosis have an increased risk of progression to MM compared to patients without BM involvement and close attention should be given to the former group during routine follow-up.

Finally, there is a small but well-recognized group of patients characterized by multiple lytic bone lesions and low BM plasmacytosis, the so-called macrofocal form of

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria for solitary plasmacytoma and overlapping disorders

Plasmacytoma Serum monoclonal protein Bone marrow cytology End organ damage Radiological work-up Risk of progression Solitary plasmacytoma

Solitary plasmacytoma Present Not required Negative No other lesions 10% will progress to MM within 3 years Solitary plasmacytoma

with minimal bone marrow involvement

Present Not required Monoclonal PC infiltration < 10%

Absent No other lesions 60% with SBP or 20% with EMP will progress to MM within 3 years Multiple

myeloma

Macrofocal myeloma Present Not required Monoclonal PC infiltration < 10%

Possible Multiple lesions Multiple myeloma Not required Present Monoclonal PC

infiltration≥ 10%

Present Other lesions could be present

MM [12]. These patients are generally younger than the overall myeloma population and have a better prognosis.

Bone marrow assessment

A unilateral BM aspiration and trephine biopsy is rec-ommended for all patients with suspected SP. In order to exclude > 10% of monoclonal PCs in the BM, a BM aspiration with immunophenotyping to define the pro-portion of monoclonal cells by kappa/lambda labeling should be performed. When the possibility for immuno-phenotyping is missing, a BM biopsy is recommended with immunohistochemistry to detect monoclonal PCs. A biopsy might reveal more monoclonal cells because of a sampling error with aspiration. The higher PC count of either aspiration or biopsy should be considered in cases of discrepancy between both techniques.

Noteworthy, the malignant phenotype of clonal PCs among patients with SP resembles that of cases with MM; accordingly, we recommend that laboratories use the same immunophenotypic strategy used in MM such as that established by the EuroFlow consortium for the assessment of minimal residual disease (MRD), which has a median limit of tumor cell detection of 2 × 10−6, and is virtually applicable to all patients with PC dyscra-sias [13]. BM plasmacytosis > 10% constitutes a definitive MM diagnosis.

Recommendations: All patients with suspected SP should receive a BM aspiration and a BM biopsy to evalu-ate PC morphology and the degree of total PC infiltration (Grade 1A). Given the diagnostic and prognostic import-ance, the degree of clonal PC infiltration should be deter-mined by flow cytometry or by kappa/lambda labeling on the BM aspirate or by immunohistochemistry on a BM bi-opsy (Grade 1B). When a monoclonal PC infiltration is present at baseline, the BM aspiration and biopsy should be repeated when a progression to MM is suspected.

Imaging

Detection and localization of SP depends on imaging studies. In addition, since SP is defined by the absence of other bone or extramedullary lesions, imaging is required to exclude a MM diagnosis.

Conventional radiography of the skeleton and computed tomography

Conventional radiography of the skeleton (skeletal sur-vey) has been recommended for the initial assessment of bone lesions for decades. SBP preferentially replaces the trabecular bone, while the cortical bone is partly conserved or even sclerotic [14]. In two thirds of the cases, the radiographic appearance is characteristic with a mixed, predominantly lytic pattern. Less commonly, SBP has a multicystic appearance. Similar to in MM patients, skeletal surveys are not sensitive enough to

detect early lytic bone lesions which are only visible when more than 30% of cortical bone is destructed [15, 16]. Moreover, conventional X-ray imaging does not reveal EMP located in soft tissues. This underlines the need for other imaging techniques for the evaluation of skeletal and extramedullary lesions, i.e., computed tom-ography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT.

In the context of EMP, CT may be helpful for an adequate loco-regional staging as regional lymph node recurrences occur in 7% of EMP cases. CT can also be used to identify spinal cord and/or nerve root compres-sion when MRI is unavailable. Importantly, comprescompres-sion due to a soft tissue mass may be missed on CT scans without contrast injection [15]. Whole-body (WB)-CT provides high-resolution images of cortical and trabecu-lar bone with a fast scanning time and it is able to detect small (< 5 mm) lytic bone lesions [17–21]. Clinical stud-ies addressing the use of WB-CT in comparison with other imaging techniques for SP are currently lacking. Low-dose WB-CT is currently proposed as the initial imaging technique of choice to detect bone disease in patients with MM [22].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Although the sensitivity of MRI to detect lytic bone le-sions is lower than that of CT, MRI is able to detect soft tissue and BM lesions and is the gold standard to detect spinal cord compression. SBP appears as an infiltration with a low T1 and a high T2 signal intensity. Moulopoulos et al. prospectively studied the role of MRI in the staging of 12 patients with SBP [23]. In order to identify other regions of BM involvement in addition to the primary SBP lesion, patients underwent spinal MRI. Additional foci of marrow replacement were found in one third of patients, and these patients showed persistent elevated serum monoclonal protein levels after radiotherapy. Conversely, patients without additional BM lesions displayed a signifi-cant reduction or disappearance of serum monoclonal protein after radiotherapy [23]. Liebross et al. confirmed these results in a second study in which 57 patients with SBP were staged with either conventional radiography alone or in combination with MRI prior to radiotherapy [24]. Among 23 patients with thoracolumbar spine disease, 7 of 8 patients, who had a solitary lesion by plain radiographs alone, developed MM in compari-son with 1 of 7 patients who also had only one lesion by MRI. Together, these prospective studies underline the importance of precise staging. Consequently, ex-cluding additional lesions is mandatory for the diag-nosis of SP as per IMWG criteria [25]. The use of diffusion-weighted MRI, a new highly sensitive tech-nique to detect and monitor tumor lesions in the BM

and soft tissues, has not been reported in the management of SP.

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT)

While 18F-FDG (fluorine-18-fludeoxyglucose) PET/CT is extensively studied in MM, only a few small-scale studies have addressed its role in SP [26]. 18F-FDG PET or 18F-FDG PET/CT may show additional lesions and have therapeutic implications in 33–55% of patients with presumed SBP as patients with a normal PET/CT did not develop MM [27–29]. Salaun et al. reported that 18F-FDG PET/CT is superior to MRI for the diagnosis and follow-up of plasmacytoma patients, although it should be noted that this study was performed in the context of extramedullary spread during MM [30]. At diagnosis, the sensitivity and specificity of PET/CT was higher than that of MRI of the spine and pelvis, because PET/CT was able to detect plasmacytoma lesions with a larger scope compared to MRI, i.e., in soft tissues, skull, ribs, and limbs. Also, the specificity of PET/CT was 99% to evaluate treatment responses, compared to 89% for MRI. A second study evaluated PET/CT and axial MRI at diagnosis and follow-up in 43 patients with either EMP (10 patients) or SBP (33 patients) [26]. PET/CT at diagnosis identified 10 patients with at least two hyper-metabolic lesions. Six of these patients progressed to MM, confirming a diagnostic role for PET/CT in SP. FDG-uptake was recently found to be correlated to the tumor size [31]: FDG-avid lesions are generally larger (41.4 mm) vs. FDG-negative lesions (23.5 mm) and the statistical risk of progression was higher in these FDG-avid lesions [31]. Based on these studies, the IMWG rec-ommended PET/CT as part of the initial evaluation of patients with SP [32].

Recommendations: In addition to the skeletal survey or CT, MRI or PET/CT are needed to exclude the presence of additional lesions and the use of at least one of these

examinations is mandatory (Grade 1A). Both are recom-mended based on small prospective studies, while PET/CT has additional prognostic value. Using both PET/CT and MRI may offer complementary information. When both PET/CT and MRI are not available, a WB-CT approach can be used to exclude other lesions. (Grade 2C). To detect additional soft tissue lesions, PET/CT is recommended for patients with EMP (Grade 1B).

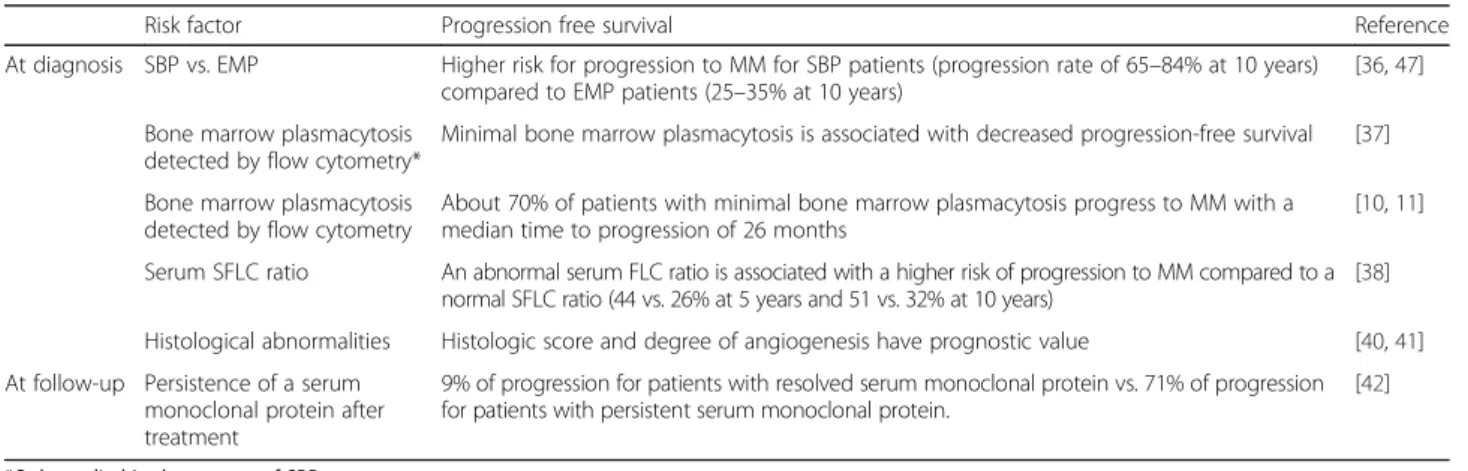

Prognostic factors

Progression of SP is defined as local recurrence, appear-ance of additional plasmacytoma without signs of MM, or a development of an overt MM. Different prognostic factors have been identified for SP and this has led to the proposal of different prognostic scoring methods (Table 2). However, none of these have been thoroughly validated and widely adopted.

Prognostic factors at diagnosis

EMP is usually indolent, in contrast to extramedullary spread of MM which is associated with poor prognosis [6, 7]. When compared to EMP, SBP has a worse prog-nosis with increased progression rates to MM, although the differences not always translate into a significant dif-ference in overall survival (OS) [3, 4, 33–36] (Table 3). At diagnosis, the presence of minimal BM infiltration by clonal PCs is a strong prognostic factor. In a retrospect-ive study, Warsame et al. found minimal BM infiltration, assessed by immunofluorescence, in 24 out of 61 patients and this was associated with an inferior progression-free survival (PFS 15 vs. 42 months for patients without BM involvement) [37]. These results were confirmed in recent studies in which flow cytome-try was used to identify monoclonal PCs in BM samples [10, 11]. Paiva et al. detected BM clonal PCs in 49% of SBP and 38% of EMP patients. Seventy-one percent of SBP patients with minimal BM involvement progressed

Table 2 Prognostic factors

Risk factor Progression free survival Reference

At diagnosis SBP vs. EMP Higher risk for progression to MM for SBP patients (progression rate of 65–84% at 10 years) compared to EMP patients (25–35% at 10 years)

[36,47]

Bone marrow plasmacytosis detected by flow cytometry*

Minimal bone marrow plasmacytosis is associated with decreased progression-free survival [37]

Bone marrow plasmacytosis detected by flow cytometry

About 70% of patients with minimal bone marrow plasmacytosis progress to MM with a median time to progression of 26 months

[10,11]

Serum SFLC ratio An abnormal serum FLC ratio is associated with a higher risk of progression to MM compared to a normal SFLC ratio (44 vs. 26% at 5 years and 51 vs. 32% at 10 years)

[38]

Histological abnormalities Histologic score and degree of angiogenesis have prognostic value [40,41] At follow-up Persistence of a serum

monoclonal protein after treatment

9% of progression for patients with resolved serum monoclonal protein vs. 71% of progression for patients with persistent serum monoclonal protein.

[42]

*Only studied in the context of SBP

to MM with a median time to progression of 26 months, compared to 8% for patients without BM involvement. Of note, no significant differences were observed among EMP cases, suggesting that BM involvement has prognostic value specifically in SBP [11]. Similar progression rates (72 vs. 12.5%) and time to progression (26 months vs. not reached) were reported by Hill et al., who only evaluated patients with SBP [10].

Alike other PC disorders, such as monoclonal gammo-pathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering MM (SMM), the serum free light chain (SFLC) ratio is an independent prognostic factor in SP for progression to MM when it is outside the normal range (< 0.26 or > 1.65) [38, 39]. These results were recently confirmed by Fouquet et al., who developed a prognostic scoring method incorporating lesions on PET/CT and an abnormal SFLC ratio at diagnosis as risk factors for progression [26]. Other proposed prognostic scoring methods include histologic scoring [40] and assessment of the degree of angiogenesis [41].

Prognostic factors during follow-up

The presence of serum monoclonal protein at the time of diagnosis has no prognostic value in SP. Conversely, persistence of the serum monoclonal protein after radiation therapy is a prognostic factor for progression to MM among SP patients with detectable serum monoclonal protein prior to treatment [23, 24, 34, 42–44]. For example, Wilder et al. reported a 10-year PFS of 29% in patients with SBP whose serum monoclonal protein did not disappear after radiotherapy, compared to 91% in pa-tients whose serum monoclonal protein did resolve [42]. Interestingly, not only the presence of serum monoclonal protein but also its levels yield prognostic information in SBP. Dingli et al. proposed a prognostic scoring method incorporating an abnormal SFLC ratio and a persistent serum monoclonal protein level > 0.5 g/dl as adverse prognostic factors. Using this method, three groups with a different risk of progression could be identified [44]. Of note, only the persistence of serum monoclonal protein 1 year after treatment has a clear prognostic value, as its level can remain stable for several months before declin-ing [44].

Recommendations: The rate of progression to MM is higher in patients with SBP compared to patients with EMP. At diagnosis, the presence of minimal BM infiltra-tion by aberrant plasma cells, the presence of addiinfiltra-tional hypermetabolic lesions on PET/CT, and an abnormal SFLC ratio give prognostic information and should be included in the initial assessment (Grade 1A). Persistence of a serum monoclonal protein (determined by serum electrophoresis and immunofixation) after initial radi-ation therapy predict a higher risk of progression to MM. Therefore, it is mandatory to monitor serum electrophoresis and immunofixation after treatment com-pletion (Grade 1A).

Treatment

Radiation therapy

Despite their locally destructive and aggressive charac-teristics, clonal PCs are highly sensitive to radiation and initial clinical trials confirmed the high response rates of SP to radiotherapy [24, 34, 45, 46]. Caution is warranted when analyzing older trials, because SP localization was generally only determined via conventional radiography and BM cytology. Therefore, many patients were likely understaged in these trials.

The evidence for the effectiveness of radiation therapy (Additional file 2: Table S2) is mainly based on retro-spective studies as no proretro-spective clinical trials in SP comparing radiotherapy to best supportive care or to chemotherapy have been reported. Ozsahin et al. retro-spectively assessed the outcome in 206 patients with SBP and 52 patients with EMP treated with radiotherapy

Table 3 Reported outcomes for patients presenting with solitary plasmacytoma Author N Local recurrence, % Overall survival, % (years) Progression-free survival, % (years) Nahi et al. [4]

Total 191 NR 53% (8 years) 75% (2 years) SBP 124 NR 56% (8 years) 65% (2 years) EMP 67 NR 51% (8 years) 94% (2 years) De Waal

et al. [36]

Total 100 0% 68% (10 years) 50% (15 years) SBP 66 0% 64%(10 years) 30% (15 years) EMP 34 0% 77% (10 years) 88% (15 years) Katodritou

et al. [61]

Total 97 NR 78% (10 years) 59% (10 years) SBP 65 NR 69% (10 years) 40% (10 years) EMP 32 NR 86% (10 years) 50% (10 years) Reed

et al. [48]

Total 84 8% 78% (5 years) 47% (5 years) SBP 59 3% 76% (5 years) 56% (5 years) EMP 25 20% 85% (5 years) 30% (5 years) Kilciksiz et al. [45] Total 80 6% 73% (10 years) NR SBP 57 6% 68% (10 years) NR EMP 23 5% 89% (10 years) NR Ozsahin et al. [5]

Total 258 14% 55% (10 years) 35% (10 years) SBP 206 14% 52% (10 years) 28% (10 years) EMP 52 14% 72%(10 years) 74% (10 years) Tsang

et al. [47]

Total 46 17% 65% (8 years) 50% (8 years)

SBP 32 22% NR 36% (8 years) EMP 14 7% NR 84% (8 years) Liebross et al. [24] SBP 57 4% 50% (10 years) 47% (10 years) Liebross et al. [3]

EMP 22 7% 50% (10 years) 68% (10 years) NR not reported, SBP solitary bone plasmacytoma, EMP

alone (214 patients), radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy (34 patients), or surgery alone (8 patients) [5]. The 5-year OS, disease-free survival (DFS), and local control rates were 74, 50, and 86% respectively in the entire patient population. Radiotherapy was a favorable prognostic factor for DFS and local control. The relapse rate for patients receiving a radiation dose of 40–50 Gy was 12% compared to 60% for patients who received no radiotherapy. The local response rate to radiotherapy exceeds 80–90% and appeared to be highest in tu-mors < 5 cm in diameter. One study reported the use of lower doses of radiotherapy and could not withhold a dose-response relationship for doses > 35 Gy, even for lar-ger tumors [47]. However, some studies did report a rela-tionship between the initial tumor size and local control rate. For example, Tsang et al. reported a 100% local con-trol rate for SBP with a diameter < 5 cm compared to only 38% for SBP with a diameter > 5 cm. Whether large SBP require a higher radiation dose or combined treatment for effective local control, as these results suggest, remains to be addressed in future clinical trials. Of note, the possible relation between the administrated radiation dose and tumor size and the local control of plasmacytoma remains controversial as other retrospective studies did not con-firm these findings [37, 48].

Based on the available clinical data, the recommended treatment for most patients with SP is localized, fractionated radiotherapy given at a dose of 40–50 Gy over approximately 4 weeks [49]. Therapy is generally given daily at a rate of 1.8–2.0 Gy per fraction. The treatment field should include all the involved tissues identified by imaging as well as a margin of healthy tis-sue (at least 2 cm). This margin is needed because the risk of tumor extension outside the initial radiation portal can enhance disease recurrence. In the case of SBP affecting vertebrae, the margin should include at least one uninvolved vertebra on either side.

Surgery

In many instances, patients have had surgery, with complete or partial tumor removal, as part of the diagnostic procedure. Apart from the diagnostic approach, the indication of surgery are fixation of fractures, decompressive laminectomy, or spine stabilization. The introduction of modern spinal fix-ation and stabilizfix-ation methods, such as vertebro-plasty and kyphovertebro-plasty, allows for a surgical solution for patients who develop vertebral fractures, vertebral instability, neurological complications, or a combin-ation of these. Radiotherapy can be delayed until after surgery but it is still required because tumor excision without subsequent radiotherapy results in a very high rate of local recurrence [46].

Chemotherapy

The role of adjuvant chemotherapy after radiation ther-apy in the treatment of SP remains controversial precluding a definite recommendation. In a study on 32 SP patients, Holland et al. observed that adjuvant chemotherapy did not affect the incidence of progression to MM (53% for SBP and 36% for EMP) but did delay progression from 29 to 59 months [43]. Similarly, Aviles et al. reported improved outcome in a small randomized prospective clinical trial on SBP when patients received adjuvant melphalan and prednisolone for 3 years [50]. After a median follow-up of 8.9 years, OS was 88% for patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, compared to 46% in the control group. Of note, BM infiltration in these patients was assessed by morphology alone, which does not have the sensitivity required to detect minimal infiltration. Conversely, other studies indicate that adju-vant chemotherapy for SP has no benefit [51, 52]. Also, autologous stem cell transplantation has been evaluated in high-risk SP patients but, although the initial results were promising, the small number of patients in this study precludes drawing definitive conclusions [53]. Some of the authors of these guidelines propose the use of adjuvant chemotherapy for bulky SP (> 5 cm), but this approach is not supported by previous studies. Similar to other plasma cell precursor entities (MGUS and SMM), bisphosphonates are recommended for those patients with confirmed osteoporosis on dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan in doses used for patients with osteoporosis [54]. Systemic use of bisphosphonates has not been studied in the context of SP but does not delay tumor progression in the SMM setting [55]. They can be considered for patients with a threatening fracture due to a SBP.

Recommendations: Radiation therapy is the standard treatment for SBP and EMP (Grade 1A). A total fraction-ated dose of 40–50 Gy should be given, and a margin of at least 2 cm should be employed (Grade 1A). For pa-tients with SBP, surgery should be reserved for the treat-ment of pathological fractures, neurological complications, or lesions with a high chance for fracture or instability. For patients with EMP, surgery might be able to resect large and well-defined masses but should be followed by radiotherapy. Due to the limited available data, adjuvant chemotherapy is not recommended for patients with SP. Adjuvant chemotherapy can be consid-ered for patients with persistent disease, based on PET/ CT, after initial radiotherapy (Grade 2C).

Response assessment

There are currently no guidelines for the assessment of treatment responses in SP. We suggest that the defini-tions that are currently applied in MM can be used in the setting of SBP, while RECIST criteria can be used for

assessing treatment responses in EMP [56, 57] (Table 4). For patients who have detectable serum monoclonal protein at diagnosis, the response can be assessed similar to the uniform IMWG response criteria for MM [58]. Serum and urine electrophoresis and immunofixation as well as serum free light chain analysis should be regu-larly performed during follow-up. As discussed, serum monoclonal protein can remain stable for several months before declining. In case of increasing serum monoclonal protein levels or the appearance of myeloma-associated end-organ damage, a new bone marrow sample should be taken in order to quantify the PC infiltration and to detect genetic abnormalities. The sensitivity of PET/CT for the evaluation of treatment re-sponses is higher than that of MRI. A persistent high uptake on 18F-FDG PET/CT indicates the presence of residual disease. Low tracer uptake at irradiated sites can be due to bone remodeling and is not always associated with a poor prognosis. Preferentially, the same imaging technique should be used for diagnosis and for the evaluation of treatment responses.

Recommendations: Treatment response should be assessed according to the IMWG criteria for patients with measurable serum/urine parameters (Grade 1B), although serum monoclonal protein can remain stable for several months. For soft tissue lesions, these criteria should be combined with the RECIST criteria (Grade 2C). During further follow-up of the disease, the same imaging (preferentially a whole body technique) method should be used, but one should be aware that the sensi-tivity of PET/CT is higher than that of MRI.

Future direction for clinical research

The current guidelines in SP are based on small-scale studies because prospective clinical trials are hampered by the low incidence of SP. Still, larger studies are needed to further establish and refine the current diag-nosis and treatment guidelines. Large prospective clin-ical trials to evaluate addition of systemic treatment (including novel agents) to radiation therapy are needed to define the optimal treatment approach of patients

presenting poor prognostic factors such as tumor size and the presence of clonal BMPCs. Moreover, different imaging techniques should be compared for SP diagnosis and follow-up. While low-dose WB-CT is used in MM, studies investigating this technique in SP are still lack-ing. At this time, PET/CT is considered the imaging technique of choice, but the introduction of diffuse weighted MRI could improve the ability of MRI to dis-criminate between active and inactive lesions. A multi-center SWOG trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00109889) comparing PET/CT with MRI in SP was closed in 2007 but its results are still unknown. In 2017, there is no sci-entific evidence that patients with an initial BM infiltra-tion require addiinfiltra-tional therapy, although they are at high risk of progression, particularly those with aberrant phenotype. Accordingly, in smoldering MM (SMM) a high-risk group of patients with > 70% risk of progres-sion to MM in 2 years could be identified by immuno-phenotyping of aberrant PCs. It has been shown that early treatment prevents progression to MM in these high-risk SMM patients [59]. Mateos et al. demonstrated not only a superior PFS, but also OS in patients treated with lenalidomide-dexamethasone, as compared to observation [60].

Although it is currently unknown, whether such a para-digm is applicable to SBP, the rate of progression to MM in SBP patients with occult BM infiltration is comparable to that observed in high-risk SMM. Therefore, a random-ized trial with similar design comparing treatment for a limited period vs. observation seems justified. A regular follow-up by blood and urine testing is required for these patients and a new BM aspiration and biopsy should be performed when a progression is suspected.

Advanced and sensitive techniques for the detection of monoclonal PCs are being developed and are already used in daily practice to detect MRD in the follow-up of MM. However, prospective trials with these new techniques in the diagnosis and follow-up of SP are lack-ing. Multiparametric flow cytometry uses a standard set of monoclonal PC-associated markers, is quantitative, includes an internal quality control of the sample

Table 4 Definition of treatment responses

Complete response (CR) Complete disappearance of all previously observed abnormalities on radiographic imaging. For patients with a secretory plasmacytoma, a disappearance of monoclonal protein from serum and/or urine. For SBP, the initial radiological abnormalities on MRI or CT should regress or stabilize during an observation time of at least 12 months to fulfill the requirements for a CR. For EMP, the disappearance of soft tissue mass is required for the definition of CR

Very good partial response (VGPR)

A CR with regard to clinical and radiological signs, but with a positive immunofixation or≥ 90% reduction in serum monoclonal protein plus urine monoclonal protein level < 100 mg/24 h.

Partial response (PR) A≥ 50% decrease in serum and/or urine monoclonal protein. For non-secretory SP, radiological features (MRI/CT) or local assessment is needed. In EMP patients, a 30% decrease in the diameter of target lesions should be observed.

Stable disease (SD) Insufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor sufficient increase to qualify for PD.

Progressive disease (PD) The development of new lesions or an increase of at least 20% in the size of existing lesions, the apparition of a myeloma defining event, and finally an increase of > 25% from lowest response value in serum and/or urine monoclonal protein.

cellularity and hemodilution, and is applicable for virtually every patient. Also, PCR-based techniques such as quantitative allele-specific oligonucleotide PCR (ASO-qPCR) and next-generation sequencing of VDJ sequences remain unexplored in SP.

While FISH studies have confirmed that SP is part of the spectrum of plasma cell disorders, they could not identify prognostic subgroups as in MM. Future compar-isons between monoclonal plasma cells obtained from SP and BM (if a minimal infiltration is present) would allow identification of additional, secondary genetic aberrations that drive tumor progression. More ad-vanced techniques such as single nucleotide polymorph-ism (SNP) or gene expression arrays will also contribute to a better understanding of the tumor biology. Inclusion of more patients in these studies will facilitate prognostic stratification and identification of patients with a high risk of progression that could benefit from a systemic treatment to postpone disease progression.

As for prognostic scoring methods, only minimal BM aberrant plasmacytosis has been extensively validated as a prognostic factor in SBP for progression to MM. The identification and validation of additional risk factors, such as those used in SMM, is of interest to better iden-tify those patients that might benefit from adjuvant ther-apy or to delay progression to MM.

Finally, additional clinical trials to address the role of adjuvant chemotherapy for SP are needed. Of note, the treatment approaches in all reported studies included conventional chemotherapy. Studies with novel potent MM agents, such as proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, ixazomib, and carfilzomib), immunomodulatory agents (thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide) or mono-clonal antibodies (elotuzumab and daratumumab) are currently lacking. Focus on those patients who are at high risk for progression to MM (i.e., the detection of BM clonal PC cells by flow cytometry, more than one hypermetabolic lesion at PET/CT plus abnormal FLC ra-tio, residual paraprotein after radiation therapy, and bulky tumor mass > 5 cm) is warranted.

Conclusion

Solitary plasmacytoma belongs to a spectrum of plasma cell disorders and is defined by a single mass of mono-clonal plasma cells that can be found in the bones or in the extramedullary regions. We updated the recommen-dations on the diagnosis and management and proposed a new definition of response assessment. While radio-therapy remains the recommended treatment, several risk factors for early progression to multiple myeloma have been identified. Further studies evaluating adjuvant treatment regimens (based on novel agents) are urgently needed for these high-risk patients.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. Grading of recommendations. (DOCX 12 kb) Additional file 2: Table S2. Results of radiotherapy in patients presenting with SP [62, 63]. (DOCX 36 kb)

Abbreviations

18F-FDG:Fluorine-18-fludeoxyglucose; ASH: American Society for Hematology; ASO-qPCR: Quantitative allele-specific oligonucleotide PCR; BM: Bone marrow; CR: Complete response; CT: Computed tomography; EMN: European Myeloma Network; EMP: Extramedullary plasmacytoma; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; IMWG: International Myeloma Working Group; MGUS: Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM: Multiple myeloma; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; PD: Progressive disease; PET/CT: Positron emission tomography–computed tomography; PR: Partial response; RECIST: Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors; SBP: Solitary bone plasmacytoma; SD: Stable disease; SFLC: Serum-free light chain; SP: Solitary plasmacytoma; VGPR: Very good partial response; WB-CT: Whole body computed tomography

Acknowledgements

The authors thank contributing EMN and IMWG experts for their significant support, fruitful discussion, and valuable suggestions.

Funding

This work has been supported by grants from the Belgian Foundation against Cancer and the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique to Jo Caers. This work is further supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe (grants 1095969 and 111424) (to Monika Engelhardt) and by Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (GCB120981SAN) (to Bruno Paiva).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Authors’ contributions

JC, JB, and LR took the initiative to start this project and drafted a first version. ME, SZ, EZ, and BP contributed in improving and writing the manuscript. All other authors corrected and gave additional recommendations that were taken into consideration. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate Not applicable

Consent for publication Not applicable

Competing interests

Jo Caers received honoraria from Amgen, Celgene, and Janssen-Cilag and research grants from Celgene. Elena Zamagni received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, BMS, and Amgen. Niels Abdilgaard received research grants from Takeda, Celgene, and Amgen and honoraria from Takeda, Celgene, and Janssen-Cilag. Xavier Leleu received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, Novartis, Sanofi, Amgen, Takeda, Pierre Fabre, Gilead, BMS, and Merck. Laura Rosinol received honoraria from Janssen, Celgene, Amgen, and Takeda. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author details

1Department of Hematology, CHU de Liège, Liège, Belgium.2Clinica Universidad de Navarra, Centro de Investigacion Medica Aplicadas (CIMA); Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Navarra (IDISNA), CIBERONC, Pamplona, Spain.3Seràgnoli Institute of Hematology, Bologna University School of Medicine, Bologna, Italy.4Hopital La Miletrie, University Hospital of Poitiers, Poitiers, France.5Department of Hematology, Hospital Clínic de

Barcelona, IDIBAPS, Barcelona, Spain.6Department of Hematology, Landspitali National University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland.7Department of Hematology, University Hospital Hôtel-Dieu, Nantes, France.8Department of Hematology, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark.9Department of Clinical Therapeutics, School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.10Instituto de Investigacion Biomedica de Salamanca, Centro de Investigación del Cancer, Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain.11Department of Hematology, University Hospital Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.12Department of Haematology, Oncology, and Bone Marrow Transplantation, Universitaetsklinikum Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.13Department of Hematology, University of Ankara, Ankara, Turkey. 14

Department of Medicine I, Wilhelminen Hospital, Vienna, Austria. 15Department of Molecular Medicine, Amyloidosis Research and Treatment Center, Foundation‘Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS) Policlinico San Matteo’, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy.16Department of Hematology, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. 17Department of Hematology and Oncology, University of Freiburg Medical Center, Freiburg, Germany.

Received: 26 October 2017 Accepted: 26 December 2017

References

1. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos M-V, Kumar S, Hillengass J, Kastritis E, Richardson P, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e538–48.

2. Dimopoulos MA, Moulopoulos LA, Maniatis A, Alexanian R. Solitary plasmacytoma of bone and asymptomatic multiple myeloma. Blood. 2000; 96:2037–44.

3. Liebross RH, Ha CS, Cox JD, Weber D, Delasalle K, Alexanian R. Clinical course of solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma. Radiother Oncol. 1999;52: 245–9.

4. Nahi H, Genell A, Walinder G, Uttervall K, Juliusson G, Karin F, Hansson M, Svensson R, Linder O, Carlson K, et al. Incidence, characteristics, and outcome of solitary plasmacytoma and plasma cell leukemia. Population-based data from the Swedish Myeloma Register. Eur J Haematol. 2017;99:216–22. 5. Ozsahin M, Tsang RW, Poortmans P, Belkacemi Y, Bolla M, Dincbas FO,

Landmann C, Castelain B, Buijsen J, Curschmann J, et al. Outcomes and patterns of failure in solitary plasmacytoma: a multicenter Rare Cancer Network study of 258 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:210–7. 6. Kilciksiz S, Karakoyun-Celik O, Agaoglu FY, Haydaroglu A. A review for

solitary plasmacytoma of bone and extramedullary plasmacytoma. Sci World J. 2012;2012:6.

7. Weber DM. Solitary bone and extramedullary plasmacytoma. ASH Education Program Book. 2005;2005:373–6.

8. Bink K, Haralambieva E, Kremer M, Ott G, Beham-Schmid C, de Leval L, Peh SC, Laeng HR, Jütting U, Hutzler P, et al. Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma: similarities with and differences from multiple myeloma revealed by interphase cytogenetics. Haematologica. 2008;93:623–6. 9. Boll M, Parkins E, O’Connor SJM, Rawstron AC, Owen RG. Extramedullary

plasmacytoma are characterized by a‘myeloma-like’ immunophenotype and genotype and occult bone marrow involvement. Br J Haematol. 2010; 151:525–7.

10. Hill QA, Rawstron AC, de Tute RM, Owen RG. Outcome prediction in plasmacytoma of bone: a risk model utilizing bone marrow flow cytometry and light-chain analysis. Blood. 2014;124:1296–9.

11. Paiva B, Chandia M, Vidriales M-B, Colado E, Caballero-Velázquez T, Escalante F, Garcia de Coca A, Montes M-C, Garcia-Sanz R, Ocio EM, et al.

Multiparameter flow cytometry for staging of solitary bone plasmacytoma: new criteria for risk of progression to myeloma. Blood. 2014;124:1300–3. 12. Dimopoulos MA, Pouli A, Anagnostopoulos A, Repoussis P, Symeonidis A,

Terpos E, Delimbasi S, Tsolakis F, Economopoulos T, Zervas C. Macrofocal multiple myeloma in young patients: a distinct entity with favorable prognosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1553–6.

13. van Dongen JJM, Lhermitte L, Bottcher S, Almeida J, van der Velden VHJ, Flores-Montero J, Rawstron A, Asnafi V, Lecrevisse Q, Lucio P, et al. EuroFlow antibody panels for standardized n-dimensional flow cytometric

immunophenotyping of normal, reactive and malignant leukocytes. Leukemia. 2012;26:1908–75.

14. Rodallec MH, Feydy A, Larousserie F, Anract P, Campagna R, Babinet A, Zins M, Drape JL. Diagnostic imaging of solitary tumors of the spine: what to do and say. Radiographics. 2008;28:1019–41.

15. Caers J, Withofs N, Hillengass J, Simoni P, Zamagni E, Hustinx R, Beguin Y. The role of positron emission tomography-computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and follow up of multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2014;99:629–37.

16. Edelstyn GA, Gillespie PJ, Grebbell FS. The radiological demonstration of osseous metastases. Experimental observations. Clin Radiol. 1967;18:158–62. 17. Hur J, Yoon CS, Ryu YH, Yun MJ, Suh JS. Efficacy of multidetector row

computed tomography of the spine in patients with multiple myeloma: comparison with magnetic resonance imaging and fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:342–7. 18. Baur-Melnyk A, Buhmann S, Becker C, Schoenberg SO, Lang N, Bartl R, Reiser

MF. Whole-body MRI versus whole-body MDCT for staging of multiple myeloma. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1097–104.

19. Gleeson TG, Moriarty J, Shortt CP, Gleeson JP, Fitzpatrick P, Byrne B, McHugh J, O'Connell M, O'Gorman P, Eustace SJ. Accuracy of whole-body low-dose multidetector CT (WBLDCT) versus skeletal survey in the detection of myelomatous lesions, and correlation of disease distribution with whole-body MRI (WBMRI). Skelet Radiol. 2009;38:225–36.

20. Kropil P, Fenk R, Fritz LB, Blondin D, Kobbe G, Modder U, Cohnen M. Comparison of whole-body 64-slice multidetector computed tomography and conventional radiography in staging of multiple myeloma. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:51–8.

21. Horger M, Claussen CD, Bross-Bach U, Vonthein R, Trabold T, Heuschmid M, Pfannenberg C. Whole-body low-dose multidetector row-CT in the diagnosis of multiple myeloma: an alternative to conventional radiography. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54:289–97.

22. Terpos E, Kleber M, Engelhardt M, Zweegman S, Gay F, Kastritis E, van de Donk NWCJ, Bruno B, Sezer O, Broijl A, et al. European Myeloma Network guidelines for the management of multiple myeloma-related complications. Haematologica. 2015;100:1254–66.

23. Moulopoulos LA, Dimopoulos MA, Weber D, Fuller L, Libshitz HI, Alexanian R. Magnetic resonance imaging in the staging of solitary plasmacytoma of bone. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1311–5.

24. Liebross RH, Ha CS, Cox JD, Weber D, Delasalle K, Alexanian R. Solitary bone plasmacytoma: outcome and prognostic factors following radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41:1063–7.

25. Dimopoulos MA, Hillengass J, Usmani S, Zamagni E, Lentzsch S, Davies FE, Raje N, Sezer O, Zweegman S, Shah J, et al. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the management of patients with multiple myeloma: a consensus statement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:657–64.

26. Fouquet G, Guidez S, Herbaux C, Van de Wyngaert Z, Bonnet S, Beauvais D, Demarquette H, Adib S, Hivert B, Wemeau M, et al. Impact of initial FDG-PET/CT and serum-free light chain on transformation of conventionally defined solitary plasmacytoma to multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014; 20:3254–60.

27. Nanni C, Rubello D, Zamagni E, Castellucci P, Ambrosini V, Montini G, Cavo M, Lodi F, Pettinato C, Grassetto G, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT in myeloma with presumed solitary plasmocytoma of bone. In Vivo. 2008;22:513–7. 28. Schirrmeister H, Buck AK, Bergmann L, Reske SN, Bommer M. Positron

emission tomography (PET) for staging of solitary plasmacytoma. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2003;18:841–5.

29. Kim PJ, Hicks RJ, Wirth A, Ryan G, Seymour JF, Prince HM, Mac Manus MP. Impact of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography before and after definitive radiation therapy in patients with apparently solitary plasmacytoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:740–6.

30. Salaun P-Y, Gastinne T, Frampas E, Bodet-Milin C, Moreau P, Bodéré-Kraeber F: FDG-positron-emission tomography for staging and therapeutic assessment in patients with plasmacytoma. 2008.

31. Albano D, Bosio G, Treglia G, Giubbini R, Bertagna F. 18F–FDG PET/CT in solitary plasmacytoma: metabolic behavior and progression to multiple myeloma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45(1):77-84.

32. Cavo M, Terpos E, Nanni C, Moreau P, Lentzsch S, Zweegman S, Hillengass J, Engelhardt M, Usmani SZ, Vesole DH, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders: a consensus statement by the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e206–17.

33. Alexiou C, Kau RJ, Dietzfelbinger H, Kremer M, Spieß JC, Schratzenstaller B, Arnold W. Extramedullary plasmacytoma. Cancer. 1999;85:2305–14.

34. Galieni P, Cavo M, Pulsoni A, Avvisati G, Bigazzi C, Neri S, Caliceti U, Benni M, Ronconi S, Lauria F: Clinical outcome of extramedullary plasmacytoma. 2000. 35. Dores GM, Landgren O, McGlynn KA, Curtis RE, Linet MS, Devesa SS.

Plasmacytoma of bone, extramedullary plasmacytoma, and multiple myeloma: incidence and survival in the United States, 1992–2004. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:86–94.

36. de Waal EG, Leene M, Veeger N, Vos HJ, Ong F, Smit WG, Hovenga S, Hoogendoorn M, Hogenes M, Beijert M, et al. Progression of a solitary plasmacytoma to multiple myeloma. A population-based registry of the northern Netherlands. Br J Haematol. 2016;175:661–7.

37. Warsame R, Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Kyle RA, Buadi F, Dingli D, Greipp PR, Hayman SR, Kumar SK, Lust JA, et al. Trends and outcomes of modern staging of solitary plasmacytoma of bone. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:647–51. 38. Dispenzieri A, Kyle R, Merlini G, Miguel JS, Ludwig H, Hajek R, Palumbo A,

Jagannath S, Blade J, Lonial S, Dimopoulos M, Comenzo R, Einsele H, Barlogie B, Anderson K, Gertz M, Harousseau JL, Attal M, Tosi P, Sonneveld P, Boccadoro M, Morgan G, Richardson P, Sezer O, Mateos MV, Cavo M, Joshua D, Turesson I, Chen W, Shimizu K, Powles R, Rajkumar SV, Durie BG, International Myeloma Working Group. International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for serum-free light chain analysis in multiple myeloma and related disorders. Leukemia. 2009;23(2):215-24.

39. Caers J, Vekemans M-C, Bries G, Beel K, Delrieu V, Deweweire A, Demuynck H, De Prijck B, De Samblanx H, Kentos A, et al. Diagnosis and follow-up of monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance; information for referring physicians. Ann Med. 2013;45:413–22.

40. Susnerwala SS, Shanks JH, Banerjee SS, Scarffe JH, Farrington WT, Slevin NJ. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the head and neck region:

clinicopathological correlation in 25 cases. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:921–7. 41. Kumar S, Fonseca R, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Lust JA, Wellik L, Witzig TE,

Gertz MA, Kyle RA, Greipp PR, Rajkumar SV: Prognostic value of angiogenesis in solitary bone plasmacytoma. 2003.

42. Wilder RB, Ha CS, Cox JD, Weber D, Delasalle K, Alexanian R. Persistence of myeloma protein for more than one year after radiotherapy is an adverse prognostic factor in solitary plasmacytoma of bone. Cancer. 2002;94:1532–7. 43. Holland J, Trenkner DA, Wasserman TH, Fineberg B. Plasmacytoma.

Treatment results and conversion to myeloma. Cancer. 1992;69:1513–7. 44. Dingli D, Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV, Nowakowski GS, Larson DR, Bida JP, Gertz

MA, Therneau TM, Melton LJ 3rd, Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA. Immunoglobulin free light chains and solitary plasmacytoma of bone. Blood. 2006;108:1979–83.

45. Kilciksiz S, Celik OK, Pak Y, Demiral AN, Pehlivan M, Orhan O, Tokatli F, Agaoglu F, Zincircioglu B, Atasoy BM, et al. Clinical and prognostic features of plasmacytomas: a multicenter study of Turkish Oncology Group-Sarcoma Working Party. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:702–7.

46. Knobel D, Zouhair A, Tsang RW, Poortmans P, Belkacemi Y, Bolla M, Oner FD, Landmann C, Castelain B, Ozsahin M. Prognostic factors in solitary plasmacytoma of the bone: a multicenter Rare Cancer Network study. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:118.

47. Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK, Pintilie M, Bezjak A, Wells W, Hodgson DC, Stewart AK. Solitary plasmacytoma treated with radiotherapy: impact of tumor size on outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:113–20. 48. Reed V, Shah J, Medeiros LJ, Ha CS, Mazloom A, Weber DM, Arzu IY, Orlowski

RZ, Thomas SK, Shihadeh F, et al. Solitary plasmacytomas: outcome and prognostic factors after definitive radiation therapy. Cancer. 2011;117:4468–74. 49. Soutar R, Lucraft H, Jackson G, Reece A, Bird J, Low E, Samson D. Guidelines

on the diagnosis and management of solitary plasmacytoma of bone and solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:717–26. 50. Aviles A, Huerta-Guzman J, Delgado S, Fernandez A, Diaz-Maqueo JC.

Improved outcome in solitary bone plasmacytomata with combined therapy. Hematol Oncol. 1996;14:111–7.

51. Shih LY, Dunn P, Leung WM, Chen WJ, Wang PN. Localised plasmacytomas in Taiwan: comparison between extramedullary plasmacytoma and solitary plasmacytoma of bone. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:128–33.

52. Bolek TW, Marcus RB Jr, Mendenhall NP. Solitary plasmacytoma of bone and soft tissue. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36:329–33.

53. Jantunen E, Koivunen E, Putkonen M, Siitonen T, Juvonen E, Nousiainen T. Autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with high-risk plasmacytoma. Eur J Haematol. 2005;74:402–6.

54. Terpos E, Morgan G, Dimopoulos MA, Drake MT, Lentzsch S, Raje N, Sezer O, García-Sanz R, Shimizu K, Turesson I, et al. International Myeloma Working Group recommendations for the treatment of multiple myeloma–related bone disease. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2347–57.

55. Musto P, Petrucci MT, Bringhen S, Guglielmelli T, Caravita T, Bongarzoni V, Andriani A, D’Arena G, Balleari E, Pietrantuono G, et al. A multicenter, randomized clinical trial comparing zoledronic acid versus observation in patients with asymptomatic myeloma. Cancer. 2008;113:1588–95. 56. Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, Blade J, Barlogie B, Anderson K, Gertz M,

Dimopoulos M, Westin J, Sonneveld P, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1467–73.

57. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47.

58. Rajkumar SV, Harousseau JL, Durie B, Anderson KC, Dimopoulos M, Kyle R, Blade J, Richardson P, Orlowski R, Siegel D, et al. Consensus recommendations for the uniform reporting of clinical trials: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 1. Blood. 2011;117:4691–5.

59. Caers J, Fernandez de Larrea C, Leleu X, Heusschen R, Zojer N, Decaux O, Kastritis E, Minnema M, Jurczyszyn A, Beguin Y, et al. The changing landscape of smoldering multiple myeloma: a European perspective. Oncologist. 2016;21:333–42.

60. Mateos M-V, Hernández M-T, Giraldo P, de la Rubia J, de Arriba F, Corral LL, Rosiñol L, Paiva B, Palomera L, Bargay J, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:438–47.

61. Katodritou E, Terpos E, Symeonidis AS, Pouli A, Kelaidi C, Kyrtsonis MC, Kotsopoulou M, Delimpasi S, Christoforidou A, Giannakoulas N, et al. Clinical features, outcome, and prognostic factors for survival and evolution to multiple myeloma of solitary plasmacytomas: a report of the Greek myeloma study group in 97 patients. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:803–8. 62. Frassica DA, Frassica FJ, Schray MF, Sim FH, Kyle RA. Solitary plasmacytoma

of bone: Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16:43–8. 63. Bachar G, Goldstein D, Brown D, Tsang R, Lockwood G, Perez-Ordonez B,

Irish J. Solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma of the head and neck —long-term outcome analysis of 68 cases. Head Neck. 2008;30:1012–9.

• We accept pre-submission inquiries

• Our selector tool helps you to find the most relevant journal • We provide round the clock customer support

• Convenient online submission • Thorough peer review

• Inclusion in PubMed and all major indexing services • Maximum visibility for your research

Submit your manuscript at www.biomedcentral.com/submit