Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

HB31

J^-^^;

-2,006'

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

ADJUSTMENT

WITH

THE

EURO.

THE

DIFFICULT

CASE

OF

PORTUGAL.

Olivier

Blanchard

Working

Paper

06-04

February

23,

2006

Revised:

November

11,

2006

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper can be downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science Research

Network Paper

Collection

at

http://ssrn.conn/abstract=887

184

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTEOF

TECHNOLOGY

JAN

12007

Adjustment

within

the

euro.

The

difficult

case of

Portugal

Olivier

Blanchard

*November

11,2006

(First draft,February

2006)

Abstract

In the second halfof the 1990s, the prospect of entry in the euro led to an output

boom

and large current account deficits in Portugal. Since then, theboom

has turned intoa slump. Current account deficits arestill large, and so are budget deficits. This paper reviews the facts, the likelyadjustment inthe absenceofmajorpolicychanges, and examines policy options.'

Ithank JoaoAmador, MiguelBeleza, RicardoCaballero,Vitor Constancio, RicardoFaini,

Francesco Franco, Francesco Giavazzi, VitorCaspar, RicardoHausmann, Raoul Galambade

Oliveira,Juan FranciscoJimeno, Abel Mateus, FernandoTeixeirados Santos, SergioRebelo,

CharlesWyplosz, theeditor andthe referees, fordiscussions and comments. I thankLionel Fontagne,PedroPortugal,andthe researchdepartmentattheBankofPortugal,fordataand other information. I especiallythank Marta Abreuforherhelpthroughoutthisproject.

The

Portugueseeconomy

is in serious trouble: Productivitygrowth

is anemic.Growth

is very low.The

budget

deficit is large.The

current account deficit is verylarge.The

purpose of this paper is to analyze the options available to Portuguesepolicy

makers

at this point.To

do so however, the paper first returns to the past,thenexamines

thelikelyadjustmentprocessintheabsenceofmajor

policychanges,

and

finallyturns to policy options.Section 1 reviews the past.

To

understand the situation today, onemust

go backat least to thesecond half ofthe 1990s. Triggeredby

thecommitment

by

Portugal to join the euro, a sharp drop in interest rates

and

expectations of fastergrowth both

led to adecreasein privatesavingand

anincreaseininvest-ment.

The

resultwas

highoutput growth, decreasingunemployment,

increasingwages,

and

fast increasing current accountdeficits.The

futurehowever

turned disappointing. Productivitygrowth

went from bad

to worse.The

investmentboom

came

toan

end, and, with disappointed ex-pectations, private savingincreased. Fiscal deficitspartly offset the increase in private saving, but notby enough

toavoidaslump. Overvaluation, theresult of earlierpressureon wages

duringtheboom, imphed

that currentaccountdeficitsremained

large.This is

where

Portugal is today. In the absence of policy changes, themost

likely scenario is oneofcompetitivedisinflation, aperiodofsustained high

un-employment

until competitiveness hasbeen

reestablished, the current accountdeficit

and

unemployment

arereduced. Thisprocessis analyzed inSection2. Itis a process fraughtwith dangers,

both

economic

and

political,and

onewhich

caneasily derail. It

makes

itimperativeto thinkaboutwhat

pohcy

can do.The

options are basically two:

The

firstand

obviouslymost

attractive one is to achieve a sustained increasein productivitygrowth,

and

make

sure it is not fullyreflected inwage

growth

until

unemployment

and

the currentaccountdeficitsarereduced.Given

thelowlevelof

income

per capitain Portugalrelative to the topEU

countries, getting closer to thefrontierwould

seem

achievable. Section 3 focuseson which

reformsand

institutional changes aremost

likelyto succeed.The

second is lowernominal

wage

growth. It is obviously less attractive thanachieving the required increase in competitiveness without a long period of

unemployment.

The

main

issue is that, in the currentenvironment

ofalready lowwage

inflationboth

in Portugaland

the rest oftheEU,

such a strategy, if it is towork

fast enough,would

require a large decrease in thenominal

wage. Section4 focuseson whether

and

how

it canbe

achieved.Portugal isnot theonly

Euro

countryin trouble. Italysharesmany

ofthesame

problems.

And Germany

isnow

justemerging from

a similar cycle ofboom,

overvaluation,

and

slump. Section 5 looks briefly at theGerman

experience,with afocus

on

potential lessons for Portugal.Section 6 concludes. In short, inthe absenceof policychanges, the

adjustment

is likelyto

be

longand

painful. It canbemade

shorter,and

lesspainful. Higher productivitygrowth

and

lownominal

wage

growth

are notmutually

exclusive,and

the best policy is probably tocombine

both. Fiscal policy also has animportant

roletoplay. Deficit reductionisrequired,butitspaceand

itscontentsmay

be

linked to reformsand

wage

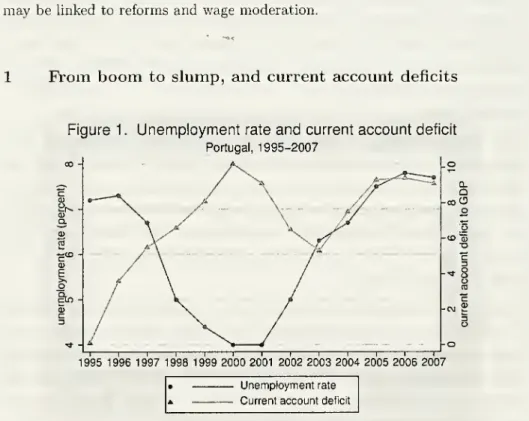

moderation.From

boom

to

slump,

and

current

account

deficitsFigure 1.

Unemployment

rateand

currentaccount

deficitPortugal, 1995-2007

19951996 1997 1998 1999 20002001 2002 2003 2004 2005 20062007 Unemploymentrate

Current accountdeficit

Source:

OECD

Economic

Outlook

June

2006.The numbers

for2006 and 2007

areOECD

forecasts.Figure 1 puts the current Portuguese

economic

situation in historicalperspec-tive. It

shows

the evolution oftheunemployment

rateand

the current accountdeficit(asaratioof

GDP)

since 1995.Two

periods clearlystandout:From

1995to2001, a steady decreasein

unemployment

and

a rapidly growing currentac-count deficit; since 2001, asteadyincreasein

unemployment, and

a continuingcurrent account deficit, with the forecasts being for

more

ofthesame

until at least2007.1Start with the

boom.

It is clear that its proximate causewas

participation in theERM

and

inthe construction oftheeuro.-^With

thereductionofinflation, the elimination ofcountryrisk,and

access to theeurobond

market, Portuguesenominal

interest ratesdechned

from

16%

in 1992to4%

in 2001; over thesame

period, real interest rates

dechned

from6%

to roughly0%.

Combined

with expectations thatparticipationintheeurowould

lead to fasterconvergenceand

thusfaster

growth

forPortugal,theresultwas an

increaseinboth

consumption

and

investment.Household

saving dropped, investment increased.The

actualbudget

deficitdecreased abit.But

discretionaryfiscalpolicywas

expansionary:From

1995 to 2001, the cyclically adjustedprimary

deficit—

which

adjusts fortheeffects oflower interestrates

and

outputgrowth

—

increasedby

roughly4%.

The

resultwas

high output growth,and

a steady decresise in unemplojrment.(Basic

numbers

for 1995 to 2001,and

for 2001 on, are given in Tables 1and

2 respectively. I decided to use

numbers

from theOECD

Economic

Outlook

database rather

than

nationalnumbers

to facilitate comparisons with othercountries.)

With

lowunemployment, nominal

wage

growth

was

substantially higherthan

labor productivity growth, leading togrowth

in unit labor costs higherthan

in the rest of the euro area (an areawhich

accounts for roughly70%

of Portuguese trade).The

result ofhigh outputgrowth

and

decreasing competitiveness (Ishalldefinecompetitiveness asthe inverse of unit labor costs relative to thosein theeuro area)was

a steadyincrease inthe current accountdeficit,

from

close to0%

in 1995 tomore

than10%

in 2000.1. Methodological changes in the LaborForce Survey imply abreakin theunemployment

series in 1998. It is estimated that, under the pre-1998 definition, the unemployment rate

would be roughly

1%

higher thanit istoday.2. Formoredetails,seeforexample Constancio(2005) ,Fagan and Caspar (2005), or

Table1.

Macroeconomic

evolutions, 1995-2001 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001GDP

growth

4.3 3.6 4.2 4.7 3.9 3,8 2.0 (relative to euro) 1.9 2.1 1.5 1,9 1.1 0,0 0.1UnemplojTnent

rate 7.2 7.3 6.7 5.0 4.4 4,0 4.0 Current account -0.1 -3.6 -5.5 -6.6 -8.1 -10,2 -9.0Household

saving 13.6 11.8 10.3 9.9 8.6 10,9 10,9Budget

surplus -5.3 -4.6 -3.4 -3.0 -2.8 -2,9 -4,3Primary

surplus (cycl adj) 1.9 1.3 0.8 -0.4 -0.7 -1,6 -2.4Nominal

wage

growth

6.7 9.0 3.8 4.3 4.0 6.9 5.2Productivity

growth

5.8 3.6 2.4 2.6 3.1 1,8 0.2Unit labor cost

growth

1.0 5.4 1.3 1.8 0.9 5,1 5.0 (relative to euro) -0.7 4,8 1.8 1.4 0.2 4.0 2.7(Source:

OECD

Economic

Outlook

Database

June

2006. "Current account":ratioofthe current account balance to

GDP.

"Household

saving": ratio todis-posable income.

"Budget

surplus"and

"Cyclically adjustedprimary

surplus": ratios toGDP.

"Nominal

wage growth" and

"labor productivity" are for the businesssector).Should

thegovernment

haveaimed

to limit the size oftheboom

and

the size ofthe current account deficitthrough

tighter fiscal policy?With

hindsight, theanswer

is surely yes. But, at the time, theanswer

was

lessobvious:• First, initial

unemployment

was

clearlyabove

the naturalrate.While an

unemplojanent

rateof7.3%

in 1996isnot highby

EU

standards,itwas

ahistoricallyhighrateforPortugal. Thus,

some

growth

inexcess ofnormal

growth

was

justified.By

theend

ofthe 1990s however,unemployment

had

clearlybecome

lowerthan

thenatural rate,and

excessgrowth was

no

longerjustified.• Second,

some

current account deficitwas

also clearly justified.A

lowerreal rate of interest

and

expectations offaster convergenceboth

justifyhigher privatespending,

be

itconsumption

and

investment.And

indeed,the

boom

was

primarily drivenby

private spending. This does not,by

itself,

imply

that thegovernment

should havejust stoodby

(thiswould

impliesthatthe large currentaccountdeficitscouldbe seenas largely be-nign, themanifestationoftheadvantages of tighterfinancial integration into the euro.^

Whether

or not,given expectations atthe time, policyshouldhavebeen

tighteris

now

anacademic

question—

althoughan

importantand open academic

ques-tion.* Starting in the early 2000s, the future turned outtobe disappointing...Table2.

Actual

and

projectedmacroeconomic

evolutions,2001-2007

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

GDP

growth

2.0 0.8 -1.1 1.1 0.3 0.7 1.5 (relativeto euro) 0.1 -0.2 -1.8 -0.7 -1.1 -1.5 -0.6Unemployment

rate 4.0 5.0 6.3 6.7 7.7 7.9 7.7 Current account -9.0 -6.4 -5.2 -7.4 -9.3 -9.6 -9.7Household

saving 10.9 10.5 10.8 10.1 9.9 9.6 9.6Budget

surplus -4.3 -2.9 -3.0 -3.2 -6.0 -5.0 -4.5Primaf'ysurplus (cycl adj) -2.4 -0.3 0.8 0.6 -1.6 0.1 0.5

Nominal

wage

growth

5.2 3.8 3.2 3.3 3.3 2.6 2.2Productivity

growth

0.2 0.1 -0.7 1.0 0.2 0.2 0.6Unit labor cost

growth

5.0 3.7 3.9 2.3 3.1 2.4 1.6 (relative to euro) 2.7 1.6 2.3 1.8 2.4 1.7 0.7Source

and

definitions:same

as Table 1.The

year 2001 is repeated forconve-nience.

The numbers

for2006

and 2007

areOECD

forecasts, as ofJune

2006.3. Thiswasindeed theinterpretationGiavazziandIgaveinBlanchardandGiavazzi (2002).

Our discussant, Pierre Olivier Gourinchas (Gourinchas 2002), was more worried about the

requiredadjustment. Hewasright.

4. Take a standard intertemporalopen economymodel, withtradables and non-tradables,

and a fixed exchange rate. Assume away all imperfections. Then, a decrease in the world

interest rate, or an increase in productivity growth willlead to an increase in consumption

and investment, and so to a current account deficit. Iflabor supply is inelastic, the wage,

andwith ittheprice ofnon-tradableswillincrease. Later on, asthecountrypaysintereston

accumulateddebt,thewagewilldecrease, andwith it,the price ofnon-tradables.Thereisno reasonforthegovernmentto intervene.(Aformalmodelalong theselinesispresentedbyFagan and Caspar (2005)). Suppose however that wages adjustslowly to labor market conditions.

Then, theincreasein demand willlead not onlyto a current account deficit, but also toan

increase in output above its natural level. Suppose thegovernment can use fiscal policy to

afi'ectdemand (becauseoffinitehorizons by privateagents forexample). Should it maintain outputatthe naturallevel,andinthe process eliminate the(partly desirable) currentaccount

deficit? Orshould itallowforsome increEise inoutput andsomecurrent accountdeficit? The

questionisofrelevance notonlyfor Portugal,butfor many othercountries.

•

Higher

laborproductivitygrowth

did not materiahze. Instead, itnearly-vanished, averaging

0.2%

per yearfrom

2001 to 2005.The

investmentboom

came

toan

end.And,

becauseofhighaccumulated

debtand

worsefuture prospects, household saving increased.

•

The

increase in private savingwas

partly offsetby

increasing public dissaving.The

actual deficit steadily increased, reaching6%

in 2005.After an

improvement

inthe early2000s,the cyclicallyadjustedprimary

deficit again turned negative in 2005.

The

ratio ofdebt toGDP,

using the Maastricht definition, reached68%

at theend

of2006.•

Lower growth and

thus lowerimport

demand

should have led to a de-crease in the current account deficit.But

thiswas

largely offsetby

a continuing increase in relative labor costs. True,nominal

wage

growth

decreased; butwhatever

competitiveadvantage

thiswould

have given Portugalwas

more

than

offsetby

thedechne

in productivity growth.As

aresult,relative unitlabor costs haveincreased

by

more

than

10%

since 2001.Because

Portugal is largely a price taker for its exports, exportprices have not increased very

much,

if at all; the implication is that profitability innon-tradables has dramatically decreased.^•

The

effects ofovervaluationfrom

theboom

werecompounded

by

com-position effects in exports.A

large proportion of Portuguese exports is in "low tech" goods, roughly60%

compared

to an average of30%

for the euro area,

goods

where

competition withemerging economies

isstrongest.^Also,remittanceshavesteadilydecreased,

from

3%

ofGDP

in1996

(down from

10%

inthe 1980s...) to1.5%

today

This suggeststhat, in the absence oftheboom-induced

overvaluation, the current account balancewould

still have deteriorated.Lower consumption and

investmentdemand

have led toan output

slump.Growth

was

negativein2003,and

hasaveraged0.3%

since2001.The

unemploy-5. Anotherlogicalpossibility is thatwages have increased much less inthe tradable sector

thanfor theeconomyas a whole.Computations from Quadrosde Pessoal by Pedro Portugal suggesthoweverthatthishas notbeenthecase, at leastupto2002 (the latestdateforwhich the informationis available.) Bargainedand actualwageshavegrownatthesamerateinthe

textileorclothingsectorsforexampleas inthe private sector asa whole.

6. These numbers come from the

ECB

(2005). For more on export composition, see alsoCabral (2005). Some other computations suggest however a less dire picture. For example, computations by Lionel Fontagne of the correlation of export shares with China's export

shares, using disaggregated (HS6 level) sectoral data, suggest that this correlation is not

higher forPortugalthanit isforGermany, reflectingthefactthat competition withemerging economies in

medium

techgoods isalsorelevant.ment

rate has increasedback

to 7.9%.As

aresult of increases in relative unit labor costson

top ofadverse structural trends, the current account deficit hassteadily increased, reaching

9.6%

in 2006.And

it increasingly reflects a largebudget

deficit, rather than lowprivate savingor high investment.2

What

happens

next?

What

happens

next, absentmajor

policy changesand major

surprises^, is a period of "competitive disinflation": a period of sustained highunemploy-ment, leading tolower

nominal

wage

growth

untilrelative unit labor costs havedecreased, competitiveness has improved, the current account deficit has de-creased,

and

demand

and

output have recovered.The

processisfamiliarfrom exchange

rate-based stabilizations (see forexample

Rebelo

and

Vegh

(1995)),and from

the competitivedisinflationmany

countrieswent

through inEurope

in the 1980sand

1990s in order to join the euro.The

evidence is that it is typically a long

and

painful process. In our study ofthecompetitive disinflation process inR-ance inthe 1980s

and

early 1990s (1993), Pierre AlainMuet

and

I concluded that, startingfrom

equal inflation athome

and

abroad, a20%

gap

incompetitiveness,and

anunemployment

rate initially2%

abovethenatural rate,it tookfour years toreduce the competitivenessgap

to

12%

(andby

then, theunemployment

gap

was

still 1,2%), sixyears toreduce it to8%

(withan

unemployment

gap

still equal to 0.8%).Are

there reasons to bemore

optimistic for Portugal, to think that, in the absence ofmajor

policy changes, theunemployment

costneeded

toreestablishcompetitiveness

would be

lower?The

answer is probably not.One

can think ofthe effects ofunemployment

on

wages

and

thuson

competi-tiveness as

depending

primarilyon two

elements (I shallkeep theargument

in the text informal.A

formalmodel

is given inBox

1):•

The

first is reaiwage

rigidities, i.e. the effect ofunemployment

on

therate of

change

of realwages.The

weaker

the effect ofunemployment,

the slower the decrease inwages

for a givenunemployment

gap,and

thusthe

more

totalunemployment

isneeded

to achieve a givenimprovement

incompetitiveness.

Isthere

any

reasonto believethatrealwages

aremore

flexible inPortugalthan

theywere

inPrancein the1980sand

1990s?I read theeconometric evidenceas giving a negative answer.Based on

the sharpadjustment

in realwages

inthe early 1980s,some

researchershave concluded thatwages

were

quite flexible in Portugal.But

themain

cause of theadjustment

seems

tohavebeen

the devaluationswhich

took placeat thetime,ratherthan

a strong responseofwages

tolabormarket

conditions (seeDiasetal(2004)). Coefficientsestimated overthe

more

recentpast suggesthmited

real

wage

flexibility.As

the econometric evidenceismurky,

it isusefultolookatthewage

bar-gaininginstitutional setup directly.

Such

a look suggests that, aswages

are typically above those set in sectoral bargaining, there issubstan-tial

room

for firms to decrease wages, that there iswhat

Portugaland

Cardoso

call a substantial"wage

cushion" (see Portugaland Cardoso

(2005)). It appearshowever

thatthiswage

cushion hasbeen

partlyusedby

firms in recent years; this suggests that flexibihty is indeed smallertoday

than itwas

in the early 2000s.The

second isnominal

wage

rigidities. This expression is usedhowever

to describe

two

verydifferent aspects ofwage

setting.The

first is the presence of lags in the response ofnominal

wages

toprices

—

and

of prices tonominal

wages.The

longerthe lags, the slower theadjustment

ofwages

for a givenunemployment

gap, thus themore

unemployment

isneeded

to achieve agivenimprovement

incompetitive-ness. Empirical evidence suggests that, even if each lag is small, their joint presence can substantially increase the

unemployment

cost oftheadjustment.

The

second ishowever

asrelevant ormore

relevant today. Itcomes from

thefact that workers

may

be

reluctant to acceptnominal

wage

declines.Indeed, in Portugal today, the labor law forbids "unjustified

wage

de-creases"and

in practice rules out decreases innominal

wages

foreco-nomic

reasons.The

evidenceon

wage

changesshows

indeedthepresenceof substantial

nominal

rigidityofthis type in Portugal (see forexample

the histograms of

wage

changesby

yearin theBank

ofPortugal report (2004)Box

2-5,and

Dickens et al (2005) foran

internationalcompari-son).

limitsthe speed at

which

competitiveness can be improved.Suppose

forexample

thatnominal

wages

areincreasing at2%

in theeuro area,and

that productivity

growth

intradables isthesame

inPortugaland

inthe therestoftheeuroarea.Then,

themost which

can beachieved, i.e.nom-inal

wage

growth

of0%,

onlyleads toan improvement

ofcompetitivenessof

2%

a year.To

summarize,

real rigidities limitthe speed ofadjustmentofthewage

tolabormarket

conditions.Nominal

rigidities further slowdown

and

may

even stop the adjustment.The

higherreal ornominal

rigidities, the larger theamount

ofunemployment

needed

to reestablish competitiveness.What

can bedone

to alleviate theunemployment

cost ofadjustment?•

One

way

is to achieve higher productivity growth. Higher productivitygrowth

isclearlydesirableon

itsown

asitimpliesa higherrate ofgrowth

ofGDP

per capita.And

it willimprove

competitiveness so long as it is not fully reflected inwage

growth. This points to reforms in thegoods

and

financial markets.•

Even

with dramatic reforms, productivitygrowth

is unlikelyhowever

toincresiseovernight. Thus, anotherand

potentiallymuch

fasterway

to reestablishcompetitivenessistodecreasenominal

wage

growth

—

indeed,giventhecircumstances,toachieve adecreasein

nominal

wages

—

withoutrelying

on

unemployment

todo

thejob over time.Are

there otherways?

The

answer isbasically no.Out-migration, the

main mechanism

throughwhich

individual U.S. statesre-turntolow

unemployment

afteran

adverse shock, is not an option, atleaston

the scale in

which

itwould

have to take place to solve theproblem

inPortugal. Fiscal policycouldinprinciplebe usedtoincreaseaggregatedemand

and

reduceunemployment.

Thishowever would

come

at the cost ofan'even larger currentaccount deficit, and,

by

decreasingunemployment

and

thedownward

pressureon

wages,would

slowdown

oreven stop theimprovement

in competitiveness.It

would

thus imply largerand

longer lasting current account deficits. Thus, even leaving aside the facts that the ratio of public debt toGDP

is already highand would

be getting higher, thiswould

only postponethemacroeconomic

adjustment, not solve it. I shall later argue that fiscal policy can help as part

ofapolicy package.

The

pointmade

here isthat,by

itself, it cannot solveboth

the competitiveness

and

theunemployment

problems.In this context, let

me

briefly takeup

a proposition that hasappeared

insome

pohcy

discussions, the proposition that afiscalconsohdation could, in the cur-rent context,be expansionaryand perhaps

evenimprove

competitiveness.While

there are indeed circumstancesinwhich

a fiscal consolidationcan

increasede-mand

in the short run, Ido

notbeheve

that thisis the case forPortugal today.The main

channelthrough

which

fiscal consolidation can increasedemand

in the shortrun

isby

allowingfor adramatic

reduction inreal interest rates. Thiswould

notbe

the case for Portugal, as thenominal

interest rate isdetermined

for the euro area asa whole,

and

there is, for the time being, only anegligible riskpremium

on

Portuguese bonds. Thus, while deficit reduction is needed, itwould

be unwise to expect it to lead,by

itself, to higherdemand

and

lowerunemployment.

For thesame

reason, itwould be

unwise to expect deficitre-duction tolead to a

boom

ininvestment,and through

capital accumulation,toa substantial

improvement

in competitiveness.Box.

Wage

and

price

dynamics

Consider a small country which is part ofa

common

currency area (the euroarea^,

and which produces and consumes

tradablesand

non-tradables.Assume

thewage

equation isgiven by:Aw

=

EAp

+

EAa

—

P{u

—

u)where

Ap =

aApj\

-l-(1—

a)ApT

Aa

=

aAa-N

+

(1—

a)AaT

where

w

is the log of thenominal

wage, soAw

is the rate ofchange

of thenominal

wages;p

is the logoftheconsumption

price deflator (itselfa weighted average of thepriceofnon

tradablesand

the priceoftradables),soAp

isthe rateof inRation using the

CPI

deflator;Aa

islogproductivitygrowth

(a weighted average of productivitygrowth

innan

tradablesand

tradable production);u

and

u are the actualand

naturalunemployment

rates respectively;E

denotesanexpectation.

(A

more

general,and

theoreticallymore

appealing, formulation,would

assume

thatwages

followan

error correctionmechanism,

in which casean

error-correctionterm

would appear on

the right. Introducing such aterm

would

complicatethepresentation butnotchangesubstantiallythepointsmade

below.)

The

equation therefore states thatwage

inHationdepends

on expected price inflation, expected productivity growth,and

theunemployment

gap, the devi-ation oftheunemployment

ratefrom

the actualrate.Assume

thathome

and

foreign tradables are perfect substitutes, so the rate ofchange

oftradables pricesis equalto the rateofeurowage

inflationminus

the rate ofeuro productivitygrowth

(euroarea variables aredenotedby

asterisks):Apr

=

Ap^

=

Aw* - Aax

Assume

thatthe non-tradablesectorproduces

under constant returns to labor, so the price ofnon-tradablesisgiven by:ApTv

=

Aw

—

Aoat

Finally, define competitiveness asz

=

px

—

w +

ar, the priceminus

unit laborcostin tradables, or equivalently z

=

w*

—

a^

—

w

+

ax, the inverseofrelative unit labor costs.The

question:How

much

unemployment

isneeded

to achievea given

improvement

in competitiveness?Assume

first that expectations are equal to actual values. In this case, theequations

above

yield:Az=-^{u-u)

(1)i

— Q

The

change

incompetitivenessdepends

onlyon theunemployment

gap. Itisin-dependent

ofthe evolution ofproductivityin tradablesand

non-tradables.The

coefficientj3 capturesreal

wage

rigidities.The

lowerthat coefficient, the larger theunemployment

needed

to achieve a givenimprovement

incompetitiveness.Now

introducenominal

rigidities (oftype 1), i.e. lags in the response ofwages

to prices.

Maintain

for themoment

theassumption

that expected productivitygrowth

isequal toactualproductivity growth,and assume

both to be constantovertime.

But

assume

now

that expected inEation is equal tolagged inflation:EAp =

Ap(-l)

In this case, the equations

above

yield:Az

=

aAz{-l)

-

P{u

-

u)Compare

this equation with the equation obtained absentnominal

rigidities.The

effect of a givenunemployment

gap on

competitiveness isnow

slower.This in turn implies that

more unemployment

isneeded

to achieve a givenimprovement

in competitiveness.Finally consider the effects of changes in productivity growth.

To

the extentthat such changes are anticipated, equation (1)

shows

theyhave

no

effect on competitiveness.So

we must

lookattheeffectsofunanticipatedchanges. DefineVff

=

Aaj\f—

EAajM,

vt

=

Aqt

— EAar

and

v=

av^

+

(1—

C()vt, so v is unanticipated aggregate productivity growth.Assume,

for simplicity, thatexpectedinflation isequaltoactual inHation. Then,theequations

above

imply:Az

=

(u—

u) '1

—

a

I— a

For

a givenunemployment

gap, an unanticipatedincreaseinproductivityleads toan

increasein competitiveness. Thisin turn implies that lessunemployment

is

needed

to achieve a givenimprovement

in competitiveness.An

important

implicationis that it does notmatter whether

the unanticipatedincrease in overall productivity

growth

comes

from

the tradables or thenon-tradablessector.

What

mattersisv, notitscomposition, vtand

vn

work

how-ever in very different ways,vt

directlyimproves

competitiveness, but, for agiven

unemployment

rate, hasno

further effecton

the wage,v^

iiistead de-creases the price ofnon

tradables,which

in turn decreases the wage, thereforeimproving

competitivenessin the tradablessector. Thisalso indicateswhen

the equivalence breaksdown.

Ifwage

inflation is already equal to zero forexam-ple,

and

wage

inflationcannot

be negative (the second type ofnominal wage

rigidity describedin the text), productivitygrowth

innon-tradablessectorwillnot be fully reflected in

wage

inflation,and

therefore willhave

no

effecton

competitiveness.3

Increasing

productivity

growth

GDP

percapita(atPPP

prices) inPortugalis$16,400. Thisisonly52%

ofGDP

per capitainthetop fiveEU

members

($31,500).Given

Portugal'smembership

in

both

theEU

and

the euro, onemight

thinkthat this48%

gap

would

be easytoreduce, that Portugal could achieve substantiallyhigherproductivity

growth

than it currently does.^

A

McKinsey

studyofproductivityinPortugal (2005) looksatthesources ofthis gap.Of

the48%

gap, it attributes16%

to "structural" (geographicand

other) factors,and

the rest,32%

to "non-structural" factorswhich

canbe

correctedthrough

appropriate pohcies. If Portugal were able tomake

up, for example,half of the non-structural

gap

in 10 years, thiswould

translate to an increase inproductivitygrowth

of2.5%

a year.^Such an

increase inproductivitygrowth

would

clearlyincrease thegrowth

rate ofGDP

percapita. Itwould

decrease the current account deficit onlyto the ex-tentthatitimproved

competitivenessinthe tradablessector, to theextent thatwage

growth was

lessthan productivitygrowth

intradables. Thismight

requirewage

agreements limiting realwage

growth, but these are easier to achieve if productivitygrowth

is high in the first place.Under

these conditions,antici-pations ofhigher income,

and

higher profitability could lead to an increase inconsumption

and

investmentdemand

and

output,and

thus reduceunemploy-ment

fasterthan

under the adjustment path described earlier. In effect, thiswould

lookverymuch

likethe scenariomany

had

inmind

inthe 1990s.Produc-tivity

growth

decreased rather than increased however,and

that scenario didnot playout. This time, ifproductivity

growth

actually increased, it would. Letme

lookat the scenario inmore

detail,and

takeup two

issues.8. The evidence is that convergence is typically faster within

common

currency areas. Seefor exampleFrankel and Rose (2002). Whether therelation isentirely causal isamatter of

debate.

9. For comparison'ssake: Therate ofproductivitygrowth inPoland overthe lastten years

has beencloseto 4.8%. Poland's

PPP

GDP

percapita, about$10,000, isstill however lowerthan Portugal's.

Would

itbebetterforthe increaseinproductivitygrowth

totake placeinthe tradablesector orinthenon-tradablesector?

The

perhapssurprisinganswer

is that, to afirst approximation, it doesnot matter.The

reason is the following (the underlying algebra is given inBox

1):At

a givenwage

and

unemployment

rate, higher productivity in trad-ables indeed translates directly into higher competitiveness. Ifthe price of tradables is givenby

the worldmarket

however, this hasno

further effecton

the price level,and

thusno

further effecton

the wage. Higher productivity in non-tradableson

the otherhand

leads to a lower price ofnon-tradables,which

leads (for a given realconsumption

wage) to alower wage. Thus, it improves competitiveness

through

the lowerwage

rather

than

directlythrough

higher productivity in tradables.The

argument

alsoshows

the limits of this equivalence result: If, forexample,

nominal

wage

growth

is already equal to zeroand

cannotbe

negative, then,improvements

in productivity in non-tradables haveno

effect

on

the wage,and

thusno

effecton

competitiveness.Still, even with this caveat, this equivalence is an

important

result.Im-proving productivityin the tradables sector,

where

largecompanies

aremore

likelytobe

involved,and

competitionlikelytobe

stronger,may

be

much

harderthanimproving

productivity innon-tradables.Put

another way,improving

zoningregulations or redefining the licensing processand

the division of tasksbetween

localand

national authorities,may

be asimportant

—

and

easier to achieve—

than

helping createnew

high-techexporting firms.

IsitessentialforPortugal to

improve

productivityinthehightech sectorand

increaseitsshareofhigh-techexports?The

answer

is,Isuspect,no.-^°First,Portugal does nothave an obvious comparative

advantage

in high-tech:The

levelsofeducationand

R&D

spendingareboth

lowrelative toother

members

oftheEU.

Labor market

institutions, in particular thehigh level of

employment

protection,imply

low labormobility,and

thus a limited ability to reallocate resources as the high-tech frontiermoves

on.A

more

obviouscomparative advantage,and

onewhich

islikelytoremain

10. Thefocuson "high-tech" innovations

may

be misleadinginanycase:An

interestingstudy by Bhide (2006) ofa hundred venture-capital-backedfirms inthe United States shows that,inmostcases, thesefirmswerenot involved inupstream

R&D,

but rathercombiningexistinginnovations.

for a long time, is in tourism.

Many

Portuguese balk at the idea ofthe Florida model, the scenario in

which

Europeans

come

to retire in Portugal.-'^The

experience of Spain suggests that this can be amajor

source of private transfers (asretirees transfer fundsfrom

tlieir countryoforigin).^^

The

"Floridamodel", asopposed

totraditionaltourism, alsocomes

with deriveddemand

formany

products,forexample

sophisticated healthcare. Facilitating such adevelopment

through infrastructureand

coordination

seems

more

promising than startinganew

high-tech sectorfrom

scratch.What

canactuallybedone

toimprove productivity? Inanswerto thisquestion,one

typicallyhears a longlitanj^ofreforms,from reformof theeducation system,to

improvement

inthejudicial system, to deregulation ofthegoods

market, tochanges in labor

market

laws.How

does one gobeyond

these generalities?One

approach

isto use econometricsto relategrowth

to anumber

ofmeasures

of institutions for abroad

cross section of countries, to seehow

Portugal fares,and

how

improvements

in the differentmeasures

would

increase Portuguese growth. This is theapproach

followed forexample by

Tavares (2004), basedon

themeasures

of institutions developedby

Shleifer et al (1998)and by

others.Another, complementary,

approach

is to focuson

specific sectors, tomeasure

the productivitygap

with other countries,and

to tryto identifytheproximateand

deeper sources ofthis gap. This iswhat

the 2003McKinsey

study did. Itfocused

on

seven specific sectors. Letme

present its findings fortwo

ofthem,residentialconstruction,

and

tourism.^^ Ibelievetheygiveagood

sense ofwhat

reforms

may

bemost

useful.•

The

study found that productivity in residential constructionwas

only38%

ofthelevelinthebenchmark

country,in thiscasetheUnited

States.The main

proximate causes behind this62%

gap

were the lack ofstan-dardizationindesign

and

construction—

forexample

under-utilization of prefabricated materials—

which

accountedfor22%

(one third of the gap);11. Francesco Giavazzi has suggestedcallingitthe "Tuscanymodel",whichisrelevant as well

and sounds more attractive. The relevant point is that higher income retirees bring larger transfers.

12. Thereare180,000foreignersoverthe ageof65 inSpain;itissafetoassume mostofthem

areretirees. IfPortugal attracted thesame numberofretirees, and theirpensionswere equal onaveragetoincomeper capitainPortugal, thiswouldrepresent private transfers of close to

2%

ofPortugueseGDP.13. Theother sectors in the studyare food retail, retail banking, telecommunications, road

freight, and theautomotive sector.

poor

projectdesign—

forexample

highlevelsofrework

—

which

accountedfor another

15%;

inefficient execution—

forexample

under-utihzation oflabor

and machinery

—

which

accounted for another10%.

What

were

the deeper, institutional, causes?The

study concluded thatit was, first

and

foremost, informality, allowing small inefficientfirms tosurvive,

and

preventingeconomies

of scalefrom

being exploited;zon-ing

and

licensing rules, hmiting thenumber

of large scaledevelopments

(15%

in Portugal versus70%

in the Netherlands forexample) and

theassociated

economies

of scale were alsoimportant.•

The

study found that productivity in tourism (hotels)was

only44%

of the level inthebenchmark

country, in this case France.The main

proximate

causesbehind

this56%

gap were

low occupationrates

(42%

versus59%

for Prance),and

a fimited role of hotel chains(10-25%

versus34%

for France).The

deeper,institutional,causes,thestudy concluded,were

labor regula-tion,making

itdifficult forhotelsto adjust to seasonalityand

shift-basedworking

schedules,and

zoningand

licensing laws, hmiting the scope for large resort formats,and

limitingthe role of international chains.These

areonlycase studies.But

theymake

aconvincingargument

thatreducing informahty,improving

zoningand

licensingrequirements, adaptingemployment

protectionlaws to allow seasonalindustries to use labor

more

efficiently,would

go

some

way

towards increasing productivity inboth

non-tradablesand

trad-ables.Reforms

along these lines, rather than a high-tech plan,may

yield larger results in terms ofproductivitygrowth

and improved

competitiveness.In this particular context,

how

essentialarereforms inthe labormarket?

There

are clear signs that the Portuguese labormarket

is dysfunctional:At

a givenrate of

unemployment,

average duration ofunemployment

is verylong, evenby

Western

European

standards,and

flows inand

out ofunemplojrment

are verylow.

The main

cause appears tobe

the high degree ofemployment

protection.To

the extent that productivitygrowth depends

in large parton

reallocation, thissuggests that reducingemployment

protection could be one ofthe keys tohigher productivity growth.

The

studyPedro

Portugaland

I did ofjoband

worker

flows in Portugal (2001) suggestshowever

amore

nuanced

conclusion.We

found

thatjob flows, that is the degree of reallocation oflabor acrosses-tabhshments, was, surprisingly, similar to that of the United States.

Worker

flows however, including

movements

inand

out ofunemplojonent, wereunusu-ally low.

One

interpretation of these findings is thatemployment

protectionmay

notimpede

job reallocation asmuch

as onemight

have guessed. Itmay

however

reduce the quality ofmatches between

firmsand

workers,and

thusimply

a loss of productivity, ifnot ofproductivity growth.My

(tentative) con-clusion is that, while reform ofemployment

protection is highly desirableon

other grounds (such as a decrease in the average duration of

unemployment,

and

better matching), itmay

not be essential for the issue at hand,namely

higher productivity growth.

4

Decreasing

wages

Increasing productivity

growth

isnot easyand

willnothappen

overnight.^^The

other

way

to reestabhsh competitiveness is to decreasenominal

wage

growth,or even, in the current context of already low Portuguese

and

European

wage

inflation, to actuallydecrease

nominal

wages.The

important pointhereis that,given productivity,thisdecrease in

wages

isneededtoimprove

competitiveness.The

issueiswhether

it is achievedover timethroughunemployment

or ifunem-ployment

can be avoided,and

thesame

decrease achievedthrough

a voluntaryand

coordinated reduction ofwages by

workers.The

traditionalway

to achieve such a reduction is through a devaluation. Ifsuccessful, adevaluationleads to anincreaseinthe priceoftradables, giventhe

nominal

wage

and

the priceofnon

tradables.Put

another way, itdecreasesthe realconsumption

wage

and

the relative price of non-tradables,and

increases profitability in the tradables sector. Ifworkers can be convinced to accept thedecrease in the

consumption

wage,and

thus not to increasenominal

wages

inresponse to the increase in the price of tradables, the devaluation is successful

and

competitiveness is improved. Thiswas

forexample

the case in Italy in 1992,where

awage

freeze,which had been

agreed to with unions before the devaluationofthelira,was

maintainedafter the devaluation—

a devaluation in excess of30%.

14. In the second half of 2003, a large drop in inflation in Chile was partly attributed to

reforms in the distribution sector (Banco Central de Chile 2004) (through their effects on

profit margins as much as on productivity). Iftrue, this would be a nice example of how

structural reforms can haverapid macroeconomiceffects. The evidence is notoverwhelming

howeverthatthiswas themainfactorbehind thedecrease ininflation.

Given

Portugal'smembership

inthe euro, devaluationis not an optionhowever

(and I believe getting unilaterally out ofthe euro

would

have disruption costswhich

would

farexceedany

gainincompetitivenesswhich might be

obtainedin thisway).The same

resultcan be achieved however, at leaston

paper,through

a decrease in the

nominal

wage

and

the priceof non-tradables, while the price oftradables remains the same. This clearly achieves thesame

decrease in the realconsumption

wage,and

thesame

increaseintherelative priceof tradables.The

question is:Can

it actuallybe implemented?

Letme

take anumber

of issuesand

objections:• Decreases in

nominal

wages

run intoboth

psychologicaland

legalprob-lems. (Indeed, asindicatedabove, such decreases

would

probablyrequirea modificationof existing labor laws to

be

implemented).Could

there-quired

change

in relative prices be achievedthrough

taxes rather thanthrough

wages?

The

answer

isyes,but onlytoalimited extent. Consider a balancedbud-get shift

from

payroll taxes toVAT.

Exporting

firms will benefit:They

pay

lessinpayroll taxes,and

aresubject tothe foreign,unchanged,

VAT

rate.

Firms

sellingtothedomesticmarket

willlose:They

pay

lessinpay-rolltaxes,but

pay on

netmore

inVAT.

Such

ashiftwillthereforeachievean

increase in competitiveness, without achange

innominal

wages. Inpractice, the scope for such a

measure

toreestabUsh competitiveness islimited.

The

VAT

ratewas

recently increased in Portugalfrom

19%

to21%.

The

increase required toimprove

competitiveness by, say20%

or so,would

require ashift in taxationand an

increase inVAT

ratesmuch

largerthan

is realistic or feasible within theEU.

•

Could

anominal

wage

freeze—

which

hasbeen

used in other countrieson

occasion,and

is psychologically easier for workers to accept—

ratherthan an

actual decreaseinnominal

wages, be sufficient?The

answer

isthat, inthecurrentenvironment

oflow eurowage

inflationand poor

productivitygrowth

in Portugal, itwould

not achievemuch.

Take

theOECD

forecasts for2006

(as ofJune

2006):Wage

growth

and

labor productivity

growth

in the business sector for the euro area ai'eforecast to

be 2.0% and 1.1%

respectively, implying an increase in unitlaborcosts of0.9%.

Wage

and

productivitygrowth

inthe business sector in Portugal are forecast to be2.2% and 0.6%

respectively, implyingan

increase in unit labor costs of 1.6%, thus a further increase in laborcostsvis-a-vis theeuro areaof0.7%.

A

nominal

wage

freezewould

implyinstead a decreaseinrelative labor costs of1.5%.

At

that rate, itwould

takeverymany

years to reestablish competitiveness in Portugal.Can

workers be induced to accept a decrease innominal wages?

The

answer

may

wellbe

no.Unions

may

disagree with the diagnosis,and

thus disagree with the need to reestablish competitiveness.

They

may

hope

for faster productivity growth.Many

years ofhighunemployment

may

beneeded

to convinceworkers oftheneed for adjustment.There

are nevertheless three important points tomake

here.The

firstis, for given productivity growth, the adjustment of

wages

has tocome

sooner or later if competitiveness is to be improved; the question is

whether

theunemployment

costs can be reduced.The

second is thatpart of the

unemployment

costcomes from nominal

rigidities, not realrigidities. Coordinating

wage

adjustmentsand

thus reducing therole ofnominal

rigidities can decrease theunemployment

cost of theadjust-ment.

The

third is thatany

decrease innominal

wages

implies a smallerdecrease in real (consumption) wages.

Assume

tradable pricesremain

unchanged, thatnon-tradable prices are set

by

amarkup

on

wage

costs,and

the share oftradables is roughly50%.

Then

a decrease innominal

wages

of20%

leads to a decrease inconsumption wages

of only 10%.The

reason is that the price ofnon-tradables decreases inproportion towages. This is still asubstantial decrease inreal wages, but only half of the

nominal

decrease.Even

ifworkers accept thetwo arguments

above, theymay

stillworry

thatthingsmay

not turn out asexpected.There

areat leasttwo

legiti-mate

worries:The

first isthat firmsinthenon-tradablesectormay

increasetheirmar-ginsrather

than

decrease their pricesin linewith labor costs, or simplythat the pass-through fi'om

wages

to non-tradable pricesmay

be slow,implying a larger decrease in real

wages

forsome

time than impliedby

the

computation

above.^^An

apparentsolution tothiswould

betocoordinatethedecreaseinwages

and

non-tradableprices simultaneously. But,justlikepricecontrols, thisislikelyto create

major

distortions:The

reasonisthat producersofnon-15. Inmanycountries,theshift totheEurohasbeenperceivedbyconsumers,rightorwrong,

tohave led toan increasein margins byfirms. The samefearsare hkelyto be present here.

tradables use tradables as inputs inproduction,

and do

this in different proportions. Thismeans

thatnon-tradablepriceswilland

shoulddecline in different proportions.A

potentially better solution isan

ex-post con-tingentadjustment

ofnominal wages

for inflation, if inflation turns outto be higher (or, in this case, deflation turns out to be smaller)

than

expected.

The

secondworry

is that, even if competitiveness is improved, the de-crease inrealwages

may

lead toalargedecreaseinconsumption

demand,

and

thus to a decrease in outputand

tomore

unemployment,

at least in theshort run.A

potential solution heremay

be

acommitment

to usefiscal policy to sustain

demand

ifneeded. While, as discussed earlier, afiscalexpansion

would on

itsown

be both dangerous

and

counterproduc-tive, it can, as part of a package of

wage

and

fiscalcommitments,

help deliverimprovements

incompetitivenessand unemployment.

The

nominal

interestrateis setby

theECB

ineuros.To

the extentthatnominal

wage

decreases lead to anticipated deflation forsome

time, theywill lead to large ex-ante realInterest rates,

which

will affectdemand

and output

adversely.This is an

important

differencewith

what

happens

when

theadjust-ment

ismade

through

a devaluation. In that case, thenominal

interest rate,post-devaluation, typicallydecreases—

as the probability ofanother devaluation has decreased.At

thesame

time, inflationand

expectedin-flation t>T)ically increase, reflectingthe higher priceofimports.

On

both

counts, the real interest rate is likely to decrease, not increase. Here, because theadjustment

ismade

through

a decrease inwages and

non-tradable prices, the effect goes the other way.This raises the question of whether,

on

those grounds, it is better tohave

a largenominal

wage

decrease at the start, or instead to achievesmaller rates of

wage

decrease over anumber

of years.The

answer

is that this channel strengthens theargument

for a large earlynominal

wage

decrease.Take

theextreme

casewhere

thenominal

wage

decreasewere

unanticipated,and

the price ofnon-tradables did adjust towages

without

lags. In that case, the deflationwould

be fully unanticipated,and

therewould be no

effecton

ex-ante real rates. Neither ofthesetwo

assumptions

is hkely to be met, so that there will, inany

case, besome

anticipated deflation.

But

theargument

remains:The more

front-loadedthe adjustment, the larger theunanticipated portionofthedeflation,the

smallerthe effect

on

real interest rates.5

Learning

from

other countries

Portugalis not the onlycountry within the

Euro

to be facing external balance problems.-^^Italy has not

gone through

aboom/bust

cycle, but hasinstead suffered from a slow but steady deterioration of its competitiveness.Low

productivitygrowth

since the mid-1990s, together with sustainednominal

wage

growth, has led toa steady decrease in competitiveness: Unit labor costs have increased

by

15%

since 1995relative to the

Euro

area.One

reasonthisdeclineincompetitiveness has not translatedin alarge currentaccount deficit appears tobe

low internaldemand, and

lowgrowth

import growth.In contrast, the

performance

of the Spanisheconomy

since the mid-1990s is widely considered a great success.The unemployment

rate has decreasedfrom

closeto

20%

to under10%, an

achievementsometimes

referred to as the"Span-ish miracle". This steady decrease in unemplo^aiient has

come

however

with a steady increase innominal

wages

over (a very low rate of) productivity growth.'''Since 1995, unit labor costs have increased

by

21%

relative to theEuro

area.Growth

and

appreciation havecombined

to create a large currentaccountdeficit,

now

equal to9%

ofGDP.

One

may

reasonablywonder

if,ifand

when

internaldemand

slowsdown,

Spainmay

not face a situation similar to that ofPortugal today.Perhaps

themost

interestingcomparison

however,both

forthesimilaritiesand

the differences itsuggests, is withGermany.

In the early 1990s, aboom

due

to reunification led to a steady appreciationand

a loss of competitiveness. Since then,lownominal

wage

growth

relativeto productivitygrowth

hasledhowever

to areversaland

a slow but steadyincrease in competitiveness.Figures 2

and

3show

the relative evolution ofnominal

wage growth and

pro-ductivityin Portugaland

Germany.

Figure 2 presents graphicallyinformation16.

What

followsismuchtoocursory.Theintentissimplyto replacetheexperienceofPortugalinalarger context.

17. Just asinthecase ofItaly,measuredproductivitygrowthissolowas tomakeone suspect

measurementerrors.But so far, culpritshave notbeenclearly identified.

presented in tables earlier: Figure 2a plots the rate of

growth

ofcompensation

and

the rate of productivitygrowth

for the private sector in Portugal since 1996, whileFigure 2b presentsthe deviations of thesetwo

ratesfrom

theirEuro

average counterparts. Figures 3a

and 3b do

thesame

forGermany,

starting in 1992.The main

message one

gets fi'om Figure 3 is that, each year since 1992, relativeGerman

wage

growth

hasbeen

lessthan

relativeGerman

productivity.Thus, competitiveness

—

at leastmeasured

thisway

—

, hasimproved

eachyear.In contrast, as

we

had

seenearlier,Portuguese competitiveness hasdeterioratedeach year since 1995.

Figure2.

Wage

and laborproductivitygrowthPortugal1996-2006

b.RelalivetoEuro area

Figure3.

Wage

andlaborproductivitygrowthGermany 1992-2006

a. Absolute b.RelativetoEuroarea

Source:

OECD

Economic

Outlook June

2006.The numbers

for2006areOECD

forecasts.Thus, theexperience of

Germany

shows

theway

outforPortugal.Low

nominal

wage

growth and

decent productivity growth, ifitcan beachieved, lead to highercompetitiveness and, eventually, lead

back

to growth.But

itshows

alsohow

slow

and

painfulthisway

out is.German

growth

hasbeen

lowerthan Euro-areagrowth

every yearsince1995.Only

now

doesGermany

appeartohaverecovered,and

there are still doubts as towhether

and

when

higher export gi'owth will lead tosustained higher domesticconsumption and

investment growth.6

Conclusions

I

began by

arguingthat Portugalfacedan

unusuallytougheconomic

challenge:low growth, low productivity growth, high

unemployment,

largefiscaland

cur-rent account deficits.I then

examined

various policy choices,from

reforms increasing productivity growth, to coordinated decreasesinnominal

wages,and

the use offiscalpolicy in this context. Iwant

toend

on

amore

positive note.There

is a large scopeforproductivityincreasesinPortugal,

and

aset ofreformswhich

couldachievethem.

A

decrease innominal

wages

sounds exotic, but is thesame

in essence as a successful devaluation. If it can be achieved, it can substantially reducethe

unemployment

cost of the adjustment. Fiscal policy can also help.While

deficits

must

be reduced,temporary

fiscalexpansion could bepart ofan overallpackage, facihtatingtheadjustmentofwages.

The

challengeisthere.But

so are the toolsneeded

tomeet

it.References

Banco

Central de Chile (2004)Monetary

policy reportBanco

de Portugal (2004)Annual

reportBhide

A. (2006)Venturesome

consumption, innovationand

globalization,mimeo

Columbia,

Centeron

Capitalismand

SocietyBlanchard

O, GiavazziF

(2002) Current account deficitsin theEuro

area:The

end

ofthe Feldstein-Horioka puzzle?Brookings

Papers on

Economic

Activity2:147-209

Blanchard

O,Muet

PA

(1993) Competitivenessthrough

disinflation:An

as-sessment ofthe French

Macroeconomic

Strategy.Economic

Policy 8(16) April:12-56

Blanchard

0, PortugalP

(2001)What

hidesbehind an

unemployment

rate.Comparing

Portugueseand

U.S.unemployment.

American

Economic

Review

91(1)March: 187-207

Cabral

S (2004)Recent

evolution of Portuguese exportmarket

shares in theEuropean

Union.Banco

de PortugalEconomic

BulletinDecember:79-91

Cardoso

A, PortugalP

(2005) Contractualwages

and

thewage

cushion underdifferent bargaining settings. Journal of

Labor

Economics

23:875-902Constancio

V

(2005)European

monetary

integrationand

the Portuguese case,in:

The

new

EU

member

states;Convergence

and

stability. C. Detken, V.Gas-par,

and

G. Noblet, eds,European

CentralBank, October

Francisco Dias F,EstevesP,

and

FelixR

(2004) Revisiting theNAIRU

estimatesfor thePortuguese

economy.

Banco

dePortugalEconomic

Bulletin, June: 39-48 DickensW,

Goette

L,Groshen

E,Holden

S,Messina

J, SchweitzerM, Turunen

J,

and

Ward

M

(2005)The

interaction oflabormarkets

and

inflation: Analysisofmicro-data

from

the internationalwage

flexibility project,mimeo,

European

Central

Bank

Fagan

G,Caspar

V

(2005) Adjusting to theeuro area:Some

issues inspiredby

thePortuguese

experience,mimeo.

Banco

de Portugaland

European

CentralBank,

August.Frankel J,

Rose

A

(2002)An

estimate ofcommon

currencieson

tradeand

income. Quarterly Journalof

Economics,

117(2):437-466Gourinchas

P.O

(2002)Comments

on

"Current account deficits in theEuro

area:

The

end

of theFeldstein-Horiokapuzzle?". BrookingsPapers onEconomic

Activity 2:187-209

McKinsey

GlobalInstitute (2003) Portugal2010.Increasingproductivitygrowth

in Portugal.

McKinsey

Institute, LisbonRebelo

S.,Vegh

C. (1995) Real effects of exchange-based stabilization;An

analysis ofcompeting

theories.NBER

Macroeconomics

Annual, 125-174, B.Bernanke and

JRotemberg

eds,MIT

Press,Cambridge

Shleifer A,

La

Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F,and Vishny

R

(1998)Law

and

finance. Journal ofPohtical

Economy,

106:1113-1155Task

forceoftheMonetary PoHcy

Committee

oftheEuropean System

ofCen-tral

Banks

(2005)Competitivenessand

theexportperformance

oftheeuroarea.Occasional paperseries,

European

CentralBank,

June

TavaresJ (2004) Institutions