Editorial

The international quality requirements for the

conduct of clinical studies and the challenges

for study centers to implement them

Introduction

In the past 15 years, quality guidelines have been developed for the conduct of clinical research. The Good Clinical Prac-tice Guidelines (GCP) published by the International Confer-ence on Harmonization (ICH) have been implemented and become law in some countries. Based on the GCP, regulatory authorities installed national rules for the conduct of clinical studies. Finally, Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) of Pharmaceutical Companies and Clinical Research Organiz-ations (CRO) describe tactical aspects of clinical research. Those tools resulted in an increase in the quality of clinical studies. However, it is crucial for clinical research centers to implement measures that allow the adherence to those guide-lines in order to remain competitive.

Cancer patients are increasingly being treated within clini-cal studies. Thus, it is of particular interest to oncology clinics to qualify as study centers in order to provide their patients with the latest treatment options, to offer them alternatives, and, last but not least, to participate in the global research activities.

Daily practice in clinical research reveals many unresolved problems related to the quality requirements. The GCP and other binding guidelines leave ample space for interpretation with regard to translation of the rules into daily practice. On one hand, this leaves flexibility to researchers; on the other hand, SOPs of their partners (e.g. pharmaceutical companies) create conflicts which have the potential to jeopardize the implementation and constructive conduct of projects.

Because of the lack of a standard source of information and incomplete international harmonization, it is still complicated for an investigator to obtain an overview of the current rules and obligations for the conduct of clinical trials on human subjects. During an extensive literature search in Medline/ PubMed in 2003, no articles were found providing a compre-hensive summary of the current valid guidelines.

The different regulations of the national regulatory autho-rities are all based on the GCP of the ICH. But often, because of poor specificity, these guidelines are not able to give com-pletely satisfactory answers to daily practical problems that an investigator may have at a trial site.

In this editorial, we list the most comprehensive guidelines and rules including regulatory demands concerning the quality of the conduct of clinical studies with drugs in the USA and

the European Union (EU). We then discuss the impact of GCP and SOP of Study Sponsor on the clinical research conduct in study centers.

International ethical principles

The first international instrument on the ethics of medical research, The Nuremberg Code [1], was promulgated in 1947 as a consequence of the trial of physicians who had conducted atrocious experiments on unconsenting prisoners during the Second World War. The Code, designed to protect the integ-rity of the research subject, set out conditions for the ethical conduct of research involving human subjects, emphasizing their voluntary consent to research.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948 [2]. To give the Declaration legal as well as moral force, in 1966, the General Assembly adopted the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Article 7 of the Covenant states “ . . . no one shall be subjected without his free consent to medical or scientific experimentation”.

The Declaration of Helsinki [3], issued by the World Medi-cal Association in 1964, is the fundamental document in the field of ethics in biomedical research, and has influenced the formulation of international, regional and national legislation and codes of conduct. The Declaration of Helsinki amended several times, most recently in 2000, is a comprehensive inter-national statement of the ethics of research involving human subjects. It sets out ethical guidelines for physicians engaged in both clinical and non-clinical biomedical research.

These three documents may be considered as an historical foundation for today’s GCP.

International guidelines for the conduct

of clinical trials

There are three international guidelines in place for the protec-tion of human subjects in clinical trials.

(i) The World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for GCP for trials on pharmaceutical products [4].

(ii) International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects prepared by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) in collaboration with the WHO [5].

(iii) The ICH GCP [6].

The WHO has developed their guidelines in order to establish globally applicable standards for the conduct of biomedical research on human subjects. The WHO Good

Clinical Practice guideline was originally prepared in 1991 – 92 with 15 experts from drug regulatory authorities, academia and the pharmaceutical industry. The proposed guidelines were then circulated for comments to the Member States, to the rel-evant Expert Working Group of ICH and to the pharmaceutical industry.

It concerns all WHO Member States, but specifically countries where national regulations or requirements do not exist or require supplementation. Their relevant government officials may designate or adopt, in part or in whole, these guidelines as the basis on which clinical trials should be conducted.

The WHO GCP guidelines are addressed to investigators, ethics review committees, pharmaceutical manufacturers and other sponsors of research, monitors, statisticians and drug regulatory authorities.

The CIOMS, an international non-governmental organiz-ation in official relorganiz-ations with the WHO founded in 1949, has published in 2002 in collaboration with the WHO their revised/updated international guidelines. The purpose of the CIOMS guidelines is to recommend how the fundamental ethical principles that guide the conduct of biomedical research could be applied to low-resource countries, taking into consideration the cultural and socio-economic circum-stances, national laws, and executive and administration arrangements.

The impact of the WHO and CIOMS guidelines is not sub-stantial, because they are not part of the national regulations of the USA and the EU, in contrast to the ICH guidelines.

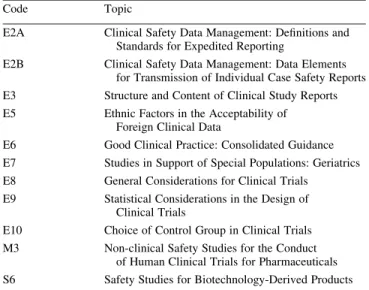

The ICH GCP was developed within the Expert Working Group of the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). The ICH is a joint initiative with experts from the regulatory authorities of Europe, Japan and USA, and from the pharmaceutical industry of the three regions as equal partners. Observers to this conference include experts from the WHO, European Free Trade Association, Canada and Australia. Expert working groups were created to draft guidelines on four main topic areas: quality, safety, effi-cacy and multidisciplinary. Since the inception of ICH, 37 guidelines covering these topics have been produced. The work under the Efficacy heading is concerned with the design, con-duct, safety and reporting of clinical trials. (Table 1 gives a list of relevant ICH Guidances. The ICH guideline ‘Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guideline’ (Efficacy6) is widely

conside-red to be one of the major achievements of the early phase of ICH.

Most countries in the EU, as well as other future EU Mem-ber States, Switzerland, Japan and the USA, have guidelines and partially legally binding regulations based on GCP.

The objective of this ICH GCP guidance is to provide a uni-fied standard for the EU, Japan and the USA to facilitate the mutual acceptance of clinical data by the regulatory auth-orities in these jurisdictions. Such harmonization makes human, animal and material resources more economical and eliminates unnecessary delays in the global development and

availability of new medicines by maintaining safeguards on quality, safety and efficacy, and regulatory obligations to pro-tect public health [7, 8].

The investigator’s responsibilities are specified quite exten-sively and Table 2 gives an extract of what an investigator should do according to ICH GCP.

Regional regulations

USA

The current regulations for conducting clinical trials with phar-maceutical compounds in the USA can be found in the Code of

Table 2.Extract of the investigator’s responsibilities according to ICH GCP

The investigator should:

Be a qualified, experienced physician to assume responsibility of the proper conduct of the trial and should provide evidence with up-to-date curriculum vitae.

Be thoroughly familiar with the study medications.

Comply with GCP and the applicable regulatory requirements. Permit monitoring and auditing by the sponsor and inspection by the

regulatory authorities.

Maintain a list of qualified persons with delegated significant trial duties. Be able to demonstrate a potential for recruiting the required number of

subjects.

Have adequate number of qualified and well informed staff to conduct the trial properly and safely.

Be responsible for all trial related medical decisions.

Ensure that adequate medical care is provided to a subject for any adverse events.

Communicate with the IRB/IEC (ethics committee) before initiating a trial and should have written all required written information to be provided to subjects.

Conduct the trial in compliance with the protocol agreed to by the sponsor (signature).

Table 1.List of relevant ICH guidances and topics

Code Topic

E2A Clinical Safety Data Management: Definitions and

Standards for Expedited Reporting

E2B Clinical Safety Data Management: Data Elements

for Transmission of Individual Case Safety Reports

E3 Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports

E5 Ethnic Factors in the Acceptability of

Foreign Clinical Data

E6 Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guidance

E7 Studies in Support of Special Populations: Geriatrics

E8 General Considerations for Clinical Trials

E9 Statistical Considerations in the Design of

Clinical Trials

E10 Choice of Control Group in Clinical Trials

M3 Non-clinical Safety Studies for the Conduct

of Human Clinical Trials for Pharmaceuticals

S6 Safety Studies for Biotechnology-Derived Products

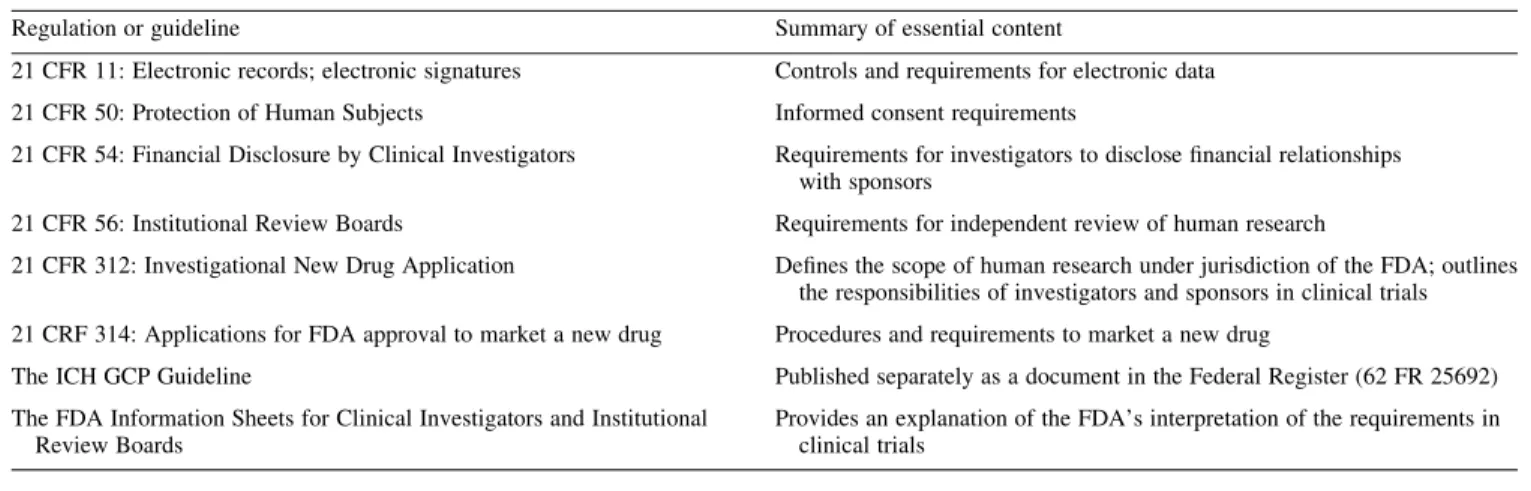

Federal Regulations (CFR). The CFR is a codification of the general and permanent rules published in the Federal Register by the Executive departments and agencies of the Federal Gov-ernment. Title 21 of the CFR is reserved for rules of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Each title (or volume) of the CFR is revised once a year. It is available electronically (Table 3).

The FDA is part of the US Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA requirements are the most compre-hensive in the world; it has published a large number of gui-dances. Some of these are simply ICH documents, but the FDA has gone far beyond this, in supplying a large amount of practical information. Their guidances are not binding [9], they represent the agency’s current thinking on the topic. An alternative approach may be used if such an approach satisfies the requirements of the applicable statues and regulations.

The FDA acts as a public health protector by ensuring that all drugs on the market exhibit a high degree of safety and efficacy. Authority to do this comes from the implementation of the 1938 Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, a law that has undergone many changes over the years.

The US provisions of particular applicability to clinical trials are listed in Table 4.

The Federal Register is a source of information on what FDA or any other government agency is doing. Published daily, the Federal Register carries all proposed and finalized regulations. Furthermore, the FDA has published Information Sheets for Clinical Investigators and Institutional Review Boards. These Information Sheets provide an explanation of the FDA’s interpretation of the requirements in clinical trials as they are published in the CFR 21.

All these regulations, information sheets and additional guidelines are available at the official homepage of the FDA, where an investigator can obtain an understanding of the drug development and regulatory process in the USA (see also Table 3).

European Union

As a result of significant differences that have developed over the years in the national requirements for carrying out clinical trials across the EU, legislation has been introduced in an attempt to simplify and harmonize the administration of clini-cal trials.

Table 3.Important and useful internet websites

ICH homepage www.ich.org

EMEA—European Medicines Evaluation Agency www.emea.eu.int

European Commission Pharmaceuticals Unit http://pharmacos.eudra.org

Legislation and guidance documents in the EU governing medicinal products http://dg3.eudra.org/F2/eudralex/index.htm

Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products www.swissmedic.ch

The World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (2000 update) www.wma.net/e/approvedhelsinki.html

ICH Guideline for Good Clinical Practice www.ifpma.org/pdfifpma/e6.pdf

World Health Organization www.who.ch

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) websites

FDA homepage www.fda.gov

Guidance documents www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/index.htm

Laws enforced by FDA and CFR 21 www.fda.gov/opacom/laws/default.htm

Good Clinical Practice www.fda.gov/oc/gcp

Table 4.Federal regulations essential to the conduct of clinical trials in the USA

Regulation or guideline Summary of essential content

21 CFR 11: Electronic records; electronic signatures Controls and requirements for electronic data

21 CFR 50: Protection of Human Subjects Informed consent requirements

21 CFR 54: Financial Disclosure by Clinical Investigators Requirements for investigators to disclose financial relationships with sponsors

21 CFR 56: Institutional Review Boards Requirements for independent review of human research

21 CFR 312: Investigational New Drug Application Defines the scope of human research under jurisdiction of the FDA; outlines the responsibilities of investigators and sponsors in clinical trials 21 CRF 314: Applications for FDA approval to market a new drug Procedures and requirements to market a new drug

The ICH GCP Guideline Published separately as a document in the Federal Register (62 FR 25692)

The FDA Information Sheets for Clinical Investigators and Institutional Review Boards

Provides an explanation of the FDA’s interpretation of the requirements in clinical trials

The EU Directive on GCP in Clinical Trials: Directive 2001/20/EC [10]. The full title of the legislation—‘Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Approximation of the Laws, Regulations and Administra-tive Provisions of the Member States Relating to Implemen-tation of Good Clinical Practice in the Conduct of Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use’ explains its pri-mary purpose. Its provisions must come into force in each EU Member State by 1 May 2004. It is therefore the first time that statutory controls have been put in place to define the ways in which clinical trials are carried out.

Directive 2001/20/EC has a particularly wide scope and applies to every clinical trial on medicinal products, whether sponsored by industry, government, research organizations, charity or a university. The Directive sets standards for pro-tecting clinical trials subjects, including incapacitated adults and minors. Importantly, it establishes ethics committees on a legal basis and provides legal status for certain procedures, such as time within which an opinion must be given. It lays down standards for commencing a clinical trial, for the manu-facture, import and labeling of investigational medicinal pro-ducts (IMPs), and provides for quality assurances of clinical trials and IMPs. To ensure compliance with these standards, it requires Member States to set up inspection systems for Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and GCP. It also provides guidelines for safety monitoring of patients in trials, and sets out procedures for reporting and recording adverse drug reac-tions and events. To help with the exchange of information between Member States, secure networks will be established linked to European databases for information about approved clinical trials and pharmacovigilance.

All clinical trials on medicinal products for human use should be designed, conducted, recorded and reported accord-ing to the principles of good clinical practice. The EU Commission is required to publish detailed guidelines. This guideline, released for consultation on 10 July 2002, clarifies the principles of GCP in the conduct of clinical trials in the EU [11]. It states that sponsors and investigators shall also take into account the existing Community Guidelines, in particular the note for guidance on GCP (CPMP/ICH135/95) [6].

The national competent authorities of the Member States remain responsible for conducting inspection of the sites con-cerned by any clinical trial conducted to verify compliance with the provisions on GCP and GMP.

The texts of legislation and other provisions governing medicinal products in the European Community can be found on the EudraLex/Pharmaceutical Unit website of the European Commission (Table 3).

Implication of GCP and Sponsor-SOP on daily

clinical research practice

Academic centers in oncology have the ongoing task of main-taining or improving the quality of medical care of their patients. The benefit of new interventions, however, can only be evaluated by intensive research. Participation in the

conduct of clinical trials is therefore unavoidable. It provides contact with the most recent state of the art research and increases the quality of care of patients. To conduct clinical research in compliance with existing guidelines and national regulatory requirements is a challenge for an Academic Research Center. It is time consuming to obtain an overview of the complex nature of guidelines. The implementation of the current binding rules in the daily practice of a study center requires professional management of clinical trials. The organ-ization and structure of the research staff have to be adjusted to the manifold materia and the growing needs of the particu-lar centers. A responsible research director and departments with well educated staff for the different domains of clinical trials have to be established.

One conclusion of our work is that the ICH GCP and the Declaration of Helsinki, in compliance with the requirements of the national regulatory authorities, should serve as the basis of each clinical trial in order to establish international accep-tance of clinical trial data. The guidances published by the FDA are a helpful support concerning the implementation of clinical studies.

What is the impact of these rules on the conduct of clinical trials in daily practice? Patient care is confronted with an increasing degree of bureaucracy topped by the need to keep an eye on the study’s internal procedures. In many cases, the latter is the real problem, namely the room for interpretation of GCP by pharmaceutical companies [12]. The fact that the SOPs are usually constructed in extreme detail, can lead to conflict situations, which impair the practicability of clinical trials in research centers.

Examples for GCP and protocol violations occur for instance, with the patient information and informed con-sent. Informed consent prospectuses created by the sponsor often contain an enormous amount of information, and are too extensive and incomprehensible for the layman. A clear

Table 5.GCP and protocol compliance problems of our research center in daily practice

Excessively lengthy patient information prospectuses.

Definition and interpretation of investigator and subinvestigator. To be an Investigator in a clinical study means among others the completion of several forms. In our opinion, only those doctors who are actively involved in patient information and decision on diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in study patients should be (sub-) investigators. Residents in education shall therefore only become investigators if they are actively and directly involved in the study conduct. Curriculum vitae (CV) of all hospital staff involved in the study are

needed. Resident doctors, who have seen a trial subject once or twice, have to submit a CV or fill out other forms, i.e. financial disclosure. Sometimes CVs of pharmacists or laboratory personal are required without their direct involvement in the study.

Non-uniform handling concerning serious adverse events reporting. Reimbursement of the standard chemotherapy in a randomized

placebo-controlled study.

Data protection and confidentiality related to the transfer of patients’ data to third parties (e.g. CT scans and histology slides for second review). Rights and obligations of study centers; study agreements.

and reasonable document with a non-technical language and a length of three or four pages seems to be more appropriate. Further examples of GCP compliance problems are listed in Table 5.

Additional education of the research staff in the EU and the presentation of the FDA guidance could make the necessity for filling out some forms more understandable.

With the implementation of professional structures in research centers with competent manpower that helps to inter-pret GCP, the necessary competence to not abandon the lack of GCP to the free interpretation by pharmaceutical companies should be achievable. Research centers need to develop their own SOPs in order to set minimum standards.

Some of the problems must be discussed carefully between the concerned study centers, the industry and the competent authorities. Further work on the mutual common interpretation of guidelines for the conduct of clinical studies is needed in order to achieve a high quality standard while maintaining feasibility.

If guidelines are mainly developed by partners who are not conducting the trials on site, then we move into a century of unrealistic theory and will therefore prevent academic research activities.

A. Gajic, R. Herrmann & M. Salzberg* University Hospital Basel, Clinical Research Oncology, Spitalstrasse 26, CH-4031 Basle, Switzerland (*E-mail: salzbergm@uhbs.ch)

References

1. Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law. No. 10, Vol. 2. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office 1949; 181 – 182.

2. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations 1948, Resolution 217A(III). Avail-able at: http://www.unhchr.ch/udhr/index.htm

3. World Medical Association (WMA). Declaration of Helsinki, 52 and WMA General Assembly. Edinburgh, UK, 2000. Available at: http:// www.wma.net/e/approvedhelsinki.html

4. World Health Organization. (1995); Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) for Trials on Pharmaceutical Products. WHO Techni-cal Report Series, No. 850; 97 – 137.

5. Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, Geneva, 2002. Available at: http://www. cioms.ch/guidelines_nov_2002_blurb.htm

6. Note for Guidance on Good Clinical Practice (CPMP/ICH/135/95), ICH Topic E 6, Step 5, Consolidated Guideline 1.5.1996. London: EMEA 1997.

7. Dixon JR Jr. The International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guideline. Qual Assur 1998; 6: 65 – 74.

8. Switula D. Principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) in clinical research. Sci Eng Ethics 2000; 6: 71 – 77.

9. Fletcher AJ, Edwards LD, Fox AW, Stonier P. Principles and Prac-tice of Pharmaceutical Medicine, chapter 25, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd 2002; 297.

10. European Parliament, Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parlia-ment and of the Council of 4 April 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. Official J Eur Commun 2001; 121: 33 – 44.

11. European Commission Enterprise Directorate-General, Detailed guidelines on the principles of GCP in the conduct in the EU of clini-cal trials on medicinal products for human use. Draft 5.1. Brussels, July 2002. Available at: http://pharmacos.eudra.org/F2/pharmacos/ dir200120ec.htm — (for consultation).

12. Salzberg M, Mu¨ller E. Quality requirements in clinical studies: a necessary burden? Swiss Med Wkly 2003; 133: 429 – 432.