Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

|/io.%-30

®

working

paper

department

of

economics

DISORGANIZATION

96-30OlivierBlanchard + Michael KMWvcf"

October, 1996

massachusetts

institute

of

technology

50 memorial

drive

Cambridge, mass.

02139

OlivierBlanchard » ^ctaxel Ktev*t

Olivier

Blanchard

Michael

Kremer

** Department of Economics, MIT, Cambridge,

MA

02138. (blanchar@mit.edu) and(kre-mer@mit.edu).

We

thank SusanAthey, Abhijit Banerjee,SimonCommander,BillEasterly,AvnerGreif, Dani Kaufmann,Gian-Maria Milesi-Ferreti,Wolfgang Pesendorfer, Julio Rotemberg and

Andrei Shleifer for discussions and comments.

We

thank Maciej Dudek and Andrei Sarychevfor researchassistance. Michael Kremerthanks the Research Departmentof the International

Disorganization

Abstract

Undercentral planning,

many

firms reliedon

a single supplier formany

oftheir inputs. Transitionhasled to decentralizedbargaining betweensuppliers andbuy-ers.

Under

incompletecontracts orasymmetric information,suchbargainingcanbeinefficient, andthemechanismsthatmitigatethisproblemintheWestcanonly

play a limitedrolein transition. Forexample, thescope forlong-termrelations to

reduce opportunistic behavior is limited

when many

existing firms are expectedto disappear orchange most oftheir suppliers inthe future.

The

result hasbeendisorganization, anda sharp decrease inoutput.

The

empirical evidencesuggeststhatdisorganization has played amore important role in theformer Soviet

Union

Figures 1

and

2show

the evolution ofofficial measures ofGDP

in the countriesofthe former Soviet Union, since 1989.

The

two

figuresgive a striking picture,that of

an

extremely largedecline inoutput. In 10 out of the 15 countries,GDP

for 1996is expected tostand at less thanhalfits 1989 level.

The

evolution of theseofficial measuresreflectsin large part ashift to unofficial,unreported activities. But studies

which

attempt to adjust for unofficial activitystillconclude thatthere has

been

a largedecline inoutput.Forexample,arecentstudy, by

Kaufmann

and

Kaliberda [1995], puts the actual decline inGDP

from1989to

1994

forthesetofcountries of theformerSovietUnion

at35%, compared

toa reported decline ofabout50%.

xThislarge declinein outputpresents

an

obvious challenge forneo-classicalthe-ory.

Given

themyriadpriceand

trade distortionspresent undertheSoviet system,these countries surely operated far inside theirproduction frontier before

tran-sition.

With

the removal of these distortions, onewould have

expectedthem

tooperatecloser to the frontier,

and

thusoutput toincrease.And

one

would have

expectedthat the

development

ofnew

activitieswould

shift theproductionfron-tierout,leading to further increases inoutput over time.Thisclearlyisnot

what

has happened.

In thispaper,

we

exploreone

explanationforthe decline of output,which

we

be-lievehas played

an

importantrole.The

bestword

todescribeit isdisorganization.1. Estimatesforanumberofotherstudies aregivenanddiscussedin European Bankfor

CO CJ

o

m

cda

CDo

L_ ZD CO 3) L_a

CDm

CO CO =)Q

CJo

czo

o

>

UJ CD CD [_ ZJen

as CD CD LD CD CO CD CD CD CO -r coO

CD—

o

CD CDO

o

COo

COO

cqo

co LOo

COo

o

o

CM COo

a

CD>-|8ASH

GO i_ CD

O

CD 00 CJ ZJQ_

CD—

^

a, CD CDn

cd Q_Q

CDO

cz CD C\J CD C\J I I ImCKM(ESj-)UJO

m3<»-o;S<muj

LD O, 00 oo CD CD CD CO CDO

CD CO CD CM CO CO CD CD CDO

CD CDa

CD >-|9A9-|Disorganization

Itslogic goesas follows:

• Central planning

was

characterized by acomplex

set of highly specificre-lations

between

firms. (Following standard usage,we

shall call a relation"specific" if there is a joint surplus to the parties from dealing with each

other rather than taking their next best alternative.)

There

were typicallyfewer firms in

each

industry thanin the West.2 Formany

inputs, firmshad

or

knew

ofonlyone

supplier fromwhich

to buy. Formany

oftheir goods,firms

had

orknew

ofonlyone

buyer towhom

tosell.3• Specificity opens

room

forbargaining.Under

asymmetric informationorin-complete contracts, the result of bargaining

may

be inefficient.A

complex

set of highly specific relations can thus lead to a poor aggegate outcome,

with large effects

on

total production.•

Through

variousinstitutionsand

arrangements,economies

develop waysoflimiting the adverse effectsofspecificity:

Under

central planning, themain

instrumentwas the coercivepower

ofthecentral planner toenforce production

and

delivery ofgoods.In theWest, for

some

goods, there aremany

alternative buyersand

sellers,eliminating specificity altogether.

And

for other goods, the scope for ad-verseeffectsofspecificityis reduced by arrangementsranging fromverticalintegration, to contracts, tolong-term relations

between

firms.• Transition eliminated the central planner,

and

thus themain

instrument2.

One

reason is that, in the West, (non natural) monopolies and associated monopoly rentscreateincentivesforentry ofnewfirms.There was no suchmechanismundercentralplanning.

3. The buyerwas often acentralized trade organization, which disappeared altogether during

used to limit the adverse effects ofspecificity under the previous regime.

But the

mechanisms which

exist in theWest

could not operateright away.New

buyersand

sellerscannot becreated overnight.The

roleofcontractsisreduced

when

many

firmsare close tobankruptcy.At

thesame

time,tran-sition has created the anticipation that

many

state firms will disappear orchange

suppliers, thus shortening horizonsand

thescope for long-termre-lations to avoid the adverse effectsofspecificity.

•

The

result hasbeen

thebreakdown

ofmany

economic

relations. Tradebetween

the republics of the former SovietUnion

has fallen by farmore

than

seems

consistent with efficient reallocation. Despite priceliberaliza-tion,

many

firms report shortages of inputsand

raw materials. Firms losecrucial workers/managers,

who may

havebeen

their onlyhope

forrestruc-turing

and

survival. Cannibalization ofmachines

iswidespread,even

when

it appears that

machines

would

bemore

productive in their original use.Thisgeneral disorganization has played

an

important role inexplaining the decline inoutput.Our

paperis organizedas follows:• In sections 1 to 3,

we show

throughthreeexampleshow

specificity, togetherwitheitherincompletenessof contractsorasymmetricinformation,

can

leadto large outputlosses.

We

show

how

theeffectsdepend

bothon

the degreeofspecificity in the relations

between

firms,and

on

the complexity of theproduction process.

We

show

alsohow

theemergence

ofnew

privateop-portunities

can

lead to a collapse ofproductionin the statesector,and

toasharpreductionin total output.

Disorganization

specificity take time to develop

and

have therefore playeda limited role intransition.

We

also discuss the policy implications ofour theory,and

arguethatit

makes

a—

limited—

case forgradualism.• Insection 5, taking measures ofreported "shortages" of inputs by firms as

indicatorsofdisorganization,

we show

thatdisorganization appearstohave

played

an

important role in the former Soviet Union, but amore

limitedone

inCentral Europe.Before starting, it

may

be useful todo

some

productdifferentiation.Our

analysisisbasedon

standardideas inmicroeconomics, from asymmetricin-formation, to hold-up problems under incomplete contracts, to the

breakdown

ofcooperation in repeated

games

as the horizon shortens or as alternativeop-portunities arise.4

The

potential importance ofspecificity formacroeconomics

has

been

emphasizedrecentlybyCaballeroand

Hammour

[1996].Our

contribu-tion is to point to the potential importance of these problems in the context of

transition.

Our

analysiscomplements

other explanations of the decline inoutputintransi-tion.

Most

explanationsstart from theneed

for state firms to declineand

trans-form,

and

fornew

private firms to emerge.Some

argue that the output declinemay

reflect efficient reorganizationand unmeasured

investment in informationcapital, asfirmstry

new

techniquesand

workers lookforthe rightjobs. (Atkesonand Kehoe

[1992],Shimer

[1995] forexample). Incontrast,we

seethe evidence4.

On

this last topic, see for example Wells and Maher [1995] for breakdowns ofcoopera-tion within households, and Banerjee and

Newman

[1993] for an example in the contextofas reflecting in large partinefficientdisorganization.

Other

explanationscombine

reallocationwith

some

remainingdistortion, explaining the declinein output as a second-best outcome. Perhaps themost

widely accepted explanation arguesthat efficient reallocation

would have

implied a decrease inreal wages ofsome

workersinconsistent witheither actual

wage

determinationor politicalconcernsabout

income

distribution;asaresultof thesecontraints,employment and

outputhave decreased (see Blanchard [1996]).

We

read the evidence from the formerSoviet

Union

asshowing

that thereismore

atwork,namely

disorganization.Two

theories are related to ours.

The

first, developed byMurphy

et al. [1992],em-phasizesthe adverseeffectsofpartialprice liberalization.

The

second, developedbyShleifer

and

Vishny [1993], focuseson

the roleof corruption,and

emphasizesthe adverse effectsof rent extractionby

government

officials.We

shall point outthe relations as

we

go along.1

A

chain

of

production

This

and

thenexttwo

sectionsdevelopthreeexamples,all threeaimed

atcaptur-ing different

mechanisms

throughwhich

specificitiescan

lead toa large declineinoutput during transition.

The

first is also the simplest. Itgoes as follows:•

A

good

isproduced

accordingto aLeontieftechnologyand

requiresn

stepsof production.

Each

step of production is carried out by a different state firm(A

point ofsemantics here.We

shall use "state" firms to denote thefirms

which

existed under central planningand produced

under the plan,whether

ornot they havebeen

privatizedsince the beginning of transition.Disorganization

since transition.)

One

unit of the primarygood

leads, after then

steps, toone

unit of the final good. Intermediate goodshave

a value ofzero.The

price of thefinal

good

is normalized toone.One

may

replace "production" by "distribution" here:an

interpretationwith a Soviet

Union

flavor is that ofagood

having to travel throughn

provinces/republics,togo from theprimaryproducertothefinaldistributor.

•

The

supplier ofthe primarygood

hasan

alternative use for the input equalto c.

One

can

think ofc as a privateopportunity, perhaps the production of amuch

simplergood, avoiding the divisionof laborimplicit in thechainof production; cmay

therefore bemuch

lower than1. (It isstraightforward tointroducesimilar privateopportunitiesfortheintermediateproducersalong

thechainofproduction. Butthe point is

made

more

simplyby ignoringthispossibility.)

•

Each

buyer alongthechainknows

only thesupplierit waspairedwithundercentralplanning,

and

vice-versa.The

end

ofcentralplanningthus leavesn

bargainingproblems.

We

assume

that thereisNash

bargaining ateach

stepofproduction, withequal division ofthe surplusfrom the match.

The

characterizationofthe solutionisstraightforwardand

isobtained by workingbackward

from the laststage ofproduction.The

value of the surplus in the lastbargainingproblem,

between

thefinalproducerand

thenext-to-lastintermediateproducer isequal to 1 (by assumption, the

good

is useless before thefinal stage).

Thus, the next-to-last intermediate producerreceives (1/2). Solving recursively,

the first intermediateproducer receives(l/2)n.

The

surplus to be dividedbetween

the first intermediate producerand

thepositive

and

production takes place along the chain. Ifinstead c>

(1/2)", theprimary producerprefers totake

up

hisprivateopportunity.Thus, theappearanceof

even

mediocreprivate opportunitieswill lead to thecollapse ofproductioninthestatesector: the decreasein total output

may

beas large as 1—

(l/2)n inourexample

(what matters here is not the absolute level of private opportunities,but their level relative to opportunities in the state sector.)

The more

complex

the structure ofproduction (thehigher n), the smaller the private opportunities

needed

totrigger the collapse ofthestate sector.Avoiding the adverseeffectsofspecificityin

complex

structuresofproductionisa problem faced by firms in the

West

as well.Even

in the West,many

goods aresufficientlyspecificthat firms

can

onlygetthem

fromone

supplier, orsellthem

toone

buyer.We

shall discuss in Section 4 below themechanisms which

alleviatethe adverseeffectsofspecificity in the West,

and

why

theyhave

played alimitedrole in transition. Buta few points are worth

making

here already.The

source of the inefficiencyand

ofthe collapse ofoutput in ourexample

isa hold-up problem: each intermediate producer

must

produce its intermediategood

before bargaining with the next producer along the chain.Once

he hasproduced

the intermediategood

and

hasno

alternative use forit, hisreservationvalue isequal to zero.

The

inefficiencywould

therefore disappear ifall theproducers could signan

en-forceable contract before production took place. In thiscase, production

would

take place so long as cwas less than 1,

and

the producers as awhole

would

re-ceive 1

—

cof the output.The

source of the problem is thus the combinationofDisorganization

8

The

assumptionofincompletecontractsseems

quitereasonableinthe case of theformer Soviet Union.

The

legalsystemisstillinconstruction. Contractenforce-ment

is notoriouslyweak. Firmsoftenhave

fewvaluableassets,making

it hardtopunish

them

for deviating fromthe contract.Another

natural solutionisvertical integration. Inourexample,even

partialin-tegration (which effectively reduces the

number

ofbargaining problemsdown

from

n

to a smallernumber)

, alleviates the problem,and

full verticalintegra-tion (where one decision-maker decides

whether

or not to produce) eliminatesit.

Even

short ofvertical integration, long-termrelationsbetween

producerscan

also alleviate the problem. Iftheyare

engaged

ina long-term relation, producersmay

be willing topay their suppliermore

than the pricewe

derived above,mak-ing it

more

likely that production takes place in the chain.As we

shall argue inSection 4 however, the nature oftransition issuch that it reduces thescope for

vertical integration

and

forlong-term relations toinduce suchbehavior.2

A

statefirm

and

itssuppliers.

IInour second example, thesource ofinefficiency isnot incompletecontractsbut

asymmetric information:

•

A

state firm needsn

inputs in order to produce. Ifall inputs are available,the firm

can

producen

units ofoutput. Otherwise, output isequal tozero.•

Each

input issuppliedbyone

supplier.Each

supplier hasan

alternative usefor his input, with value c, distributed uniformly

on

[0,c]. Let F(.) denotethe distribution function, so that

F(0)

=

and

F(c)=

1.Draws

areWe

can

again think ofc as a private sector alternative, such assmall scaleproduction or sale of the input to a foreign buyer.

The

distribution of c isknown,

but the specific realizationofeach

cis private information toeach

supplier, c

can

bethoughtofasindicating thedegree ofdevelopment

oftheprivate sector,

which

we

assume

isvery low pre-transition,and

increasingovertime thereafter.

•

The

statefirm maximizes expected profit. Itannounces

a take-it or leave-itprice

p

toeach

supplier (given thesymmetry

built in the assumptions, thepriceisthe

same

forallsuppliers). Ifthepriceexceedsthe reservationpricesofallsuppliers, production takes place in thestate firm. Otherwise, it does

not,

and

all suppliers use theirown

private opportunity.We

can

now

characterizeexpectedstate, private,and

total productionasafunc-tionofc

and

n.We

must

firstsolve fortheprofit-maximizingpricesetbythestatefirm.

Given

price p,expected profit isgivenby:ir

=

(F(p))n

(l-p)n

The

firsttermis theprobability that productiontakesplace.The

second isequaltoprofit ifproduction takesplace. Maximizing with respect to

p

yields theprofitmaximizingprice:

p

=

min(c

,—

—

-)n

+

IThe

firm never paysmore

than themaximum

alternative opportunity, c. But, ifDisorganization 10

increase its price. Increasing the price

would

increase the probability thatpro-duction takesplace, but

would

decrease expectedprofit.Given

this price, expectedstate production,Y

s, isequal to:n

1 nY

s=

nmin(l

, (——

-) )n

+

lc

Expected

private production,Y

p, isequal to theprobabilitythat stateproductiondoes not take place, times the conditional expected

sum

ofalternativeopportu-nities (conditional

on

at leastone

private alternative being largerthan the priceofferedby the state firm).

Y

p

can

be writtenas:nr

n

\ n+1^

=

^(0,1-^1)

)Expected

totalproduction isin turnequal toY

=

Y

s+

Y

pThe

bestway

to seewhat

theseequationsimplyisto lookatFigure3,which

plotsthe behavior, for

n

'.==4, ofexpectedstate, private

and

total production (all threenormalizedby the

number

ofinputs, n) for values ofcranging from 0.4 to 2.4.To

interpretthe figure,itisuseful tokeep theefficientbenchmark

inmind

(whichwould

betheoutcome

ifthemonopsonistwasfullyinformedaboutthealternativeopportunities ofeach supplier

and

thus was fully discriminating, or ifthere wereZ3 CL Z3

o

~oo

a

o

cuo

>

a>o

en a;o

CU o_X

CDo

>

o

CO CD cu3

eno

O

J2> aoO

o

fl

Z' IOL

80

9'0 *'0 3 -0"0Disorganization 1 1

was less than one, production

would

always take place in the state sector.As

cincreased

above

one, itwould

sometimes beefficient not toproduce inthe statesector:expected productioninthestatesector

would

decrease,but totalexpectedproduction

would

increase. Eventually, ascbecame

verylarge,most

productionwould

take placeinthe privatesector, with expected total productionincreasinglinearlywith c.

In contrast with the efficient outcome, increases in private opportunities lead

initially to such a large decrease in state production that the net effect is a

decrease in total production. Total production starts declining

when

c exceeds(n/(n

+

1))=

.8. For cequal to 1, the efficientoutcome would

be thatproduc-tionstill only takes place inthestate firm, with totalproduction equal to

n

(1 inthe figure, as output isdivided by the

number

ofinputs).The

actualoutcome

isaproductionlevel ofonly0.75. It isnotbefore chas reachedavalue ofabout 2.0

that total production isagainequal to its pre-transitionlevel.

Complexity

ofproduction in the statesector increases the size ofthe decline inoutput.

We

can

think ofn

asan

indexof thecomplexityoftheproductionprocess.Figure 4

shows

the effectsof alternativevalues ofn

on

theevolution ofexpectedtotal production (again normalized by the

number

ofinputs) as a function ofc.The

larger n, the higher the price that the state firm offers: for c largeenough

so that the

minimum

condition does not bind,p

=

n/(n

+

1). Thus, the highern, the higher the value ofc required to trigger the collapse ofthe state sector.

But, also the higher n, the smaller the probability that production takes place

in the state firm for c

>

n/(n

+

1),and

thus the greater the initial collapse oftotal productionas c increases.

As

n

approachesinfinity, the priceoffered by theO

>

CD CD "Oo

Z3o

o

o

CDo

CD Q.X

CD>

CD CD CD ZJO

CNI CO CDo

o

O

LZ >'L£1

S'L11

0*160

9*0L0

9*0Disorganization 12

above one: the probability that at least

one

supplier willhave

a realizationofcgreater than

one

goes to one. Thus, asn

approaches infinity, the path ofstateproduction (normalizedby the

number

ofinputs) approachesone

forc<

1,and

c/2 (theexpectedvalue ofprivateproduction) forc

>

1.When

cincreasesabove1, output fallsby fifty percent.

Puttingourresults inwords: Pre-transition, suppliers have such pooralternative

opportunities that the state firm can offer a price at

which

there isno

betteralternative than to supply.

As

transition starts,and

alternatives improve,some

suppliers

now

havemore

attractive opportunities.They

start asking the firm formore.

Not

knowing which

suppliersare bluffingand which

are not, thefirmhasno

choiceother than toofferagivenprice

and

take theriskofnotgettingthe inputs.The

result isan

initial decrease in total production asopportunities improve.Let us take

two

sets ofissuesat thispoint:(1) This

example

isclosely related to the analysisbyMurphy

et al. [1992] of theeffects ofpartial priceliberalization. In theirmodel, the fact that

some

pricesareheld fixed while others are left free

can

also lead toan

inefficient diversion ofoutput from state to private firms (Young [1996] argues that a similar perverse

mechanism

isrelevantinChina).Our

argument

isthat thesame

perverseeffectsoccur

even

underfullpriceliberalization.The

presenceofreported shortages (seesection5) ina

number

offormerrepublics anumber

of yearsafternearlycompleteprice liberalizationsuggests that there is indeed

more

atwork

than partial priceliberalization.

The

implications of thetwo

models for policy are also potentiallyquite different.

The Murphy

et al. [1992]model

implies the desirability offullbe lower during transitionthan it

was

under central planning.(2)

We

haveassumed

that thesellershad

privateinformation,and

that thesellerset theprice.

What

isessentialhereisthat therebe privateinformation,and

thatthe

uninformed

partyhavesome

bargaining power.Suppose

forexample

that thefirm has private information about the value offinal production, but that, now,

suppliers

make

price offers to the firm.Assume

that theyhaveno

privateoppor-tunities,

and

choose the priceso as tomaximize

their expected revenue. Ifthesum

of the prices charged by suppliers is higher than the actual value of finalproduction, production does not take place. It is straightforward to

show

that,in thiscase, the probability that suppliers collectivelyask for too

much

and

thatfinal production does not take place is positive. It isalso easy to

show

that thisprobability increases in the

number

ofsuppliers: themore complex

theproduc-tionprocess, the

more

likely isstate production to collapse,even

in the absenceofprivate opportunities.5 This result is closely related to results

on

the adverseeffectsofcorruption

on

output.We

have

assumed

thattheprice settersweresup-pliers. But,absent theruleoflaw,they

may

begovernment

officialssellingpermitstooperate thefirm.

There

istherefore a close parallelbetween

ourargument

thatdecentralizedbargaining

between

firmshasled to adecline inoutput,and

thear-gument

made

by Shleiferand

Vishny [1993] that political decentralization has5. More formally, assumethatifallinputs are supplied, outputisequal tone,withedistributed

forexampleuniformlyon [0, 1].

Now

consider theproblemfacing supplieri. Denote thesumoftheprices setbyallothersuppliers asp_,-.Supplierimaximizes(1

—

(p_,-+

Vi)ln)Pi< ar|d^

uschooses apriceequal to pi

=

(n—

p_,)/2. In thesymmetric equilibriump_,-=

(n—

l)p,-,sothat the

common

price isequaltop=

n/(n+

1),and thestate firm produceswith probabilityDisorganization 14

led tocompetition

among

rent extractors, withlarge adverseeffectson

output.63

A

statefirm

and

itssuppliers.

11The

thirdexample shows

how

specificityand

complexitycan

combine

tocreatecoordinationfailures,

and

a collapse ofoutput.In this model, technology is again Leontiefin

n

inputs. Because theinterpreta-tion is

more

natural here,we

think of then

suppliers as then

crucial workers inthe firm. But this is not essential.

The

essential differencebetween

thisand

the previousmodel

is inthe timing ofdecisions. In the previous model, ifstatepro-ductiondidnot takeplace,supplierscouldstilltake uptheir private opportunity.

Here, suppliers

have

to decidewhether

or not to take their private opportunitybefore they

know

whether

production is taking place in thestate firm. Thisdif-ference in timing introduces problems ofcoordination

between

workers,which

we

now

examine.The

model

isas follows:•

A

statefirmneedsn

workersinorder toproduceefficiently.Assume

that itstechnologyisLeontiefin thoseworkers

(who

aretherefore theworkerswho

are difficult to replace;

we

can think of the other workers as havingbeen

solved out of the production function)

.

Ifallworkersstay,thefirmproduces

n

unitsof output, equivalently 1 unitofoutput per worker. If

one

ormore

workers leave, the firm can hirereplace-6. Empiricalevidenceon thenumberand thesizeofbribesneeded torunabusinessinUkraine

merits; replacementsare

however

lessproductive. Ifthefirm hastohireone

ormore

replacements,outputper workerisequal to7

<

1.Thus

n

measures the complexity ofthe productionprocess.The

parameter7

(whichwasimplicitly put equal to zero inthe first example) isan

inversemeasure

of the specificityofexistingworkers.•

Each

workerhasan

alternativeopportunitygiven byc,distributeduniformlyon

[0, c].Draws

are independent across workers.The

distribution of c isknown,

but the specific realizationofeach

cisprivate information.We

can

thinkofcasrepresentingtheopportunities

open

tothemost

qualifiedwork-ersafter transition, fromopeningtheir

own

business, toworking forforeignconsultingfirms,

and

so on.7•

The

wage

paid is equal for all workers (this follows from the assumptionthat alternativeopportunitiesare private information,

and

thesymmetry

inproduction),

and

isequal to output per worker. This assumptionsimplifiesthe analysis,

and

is reasonable in the case ofmany

former state firms, butthe analysis

would

be qualitatively similar as long as wages increased withother workers' participation.

•

Workers must

decide whether to takeup

their private opportunity beforethey

know

thedecisions ofother workers,and

thus the levelofoutputand

the

wage

perworkerin thestate firm.We

assume that theyare riskneutral,sothat their decision isbased

on

the expected wage.7.

An

alternative interpretationofthismodelisasamodelofshirking, where workers havedif-ferent costsofeffort.If allworkersputeffort,outputperworkerisone.Ifsomedonot,outputper

workerisequal to7instead. Underthat interpretation,onemayinterpret themodelasapplying

Disorganization 16

Thus, if all workers decide to stay, output per worker,

and

therefore thewage, isequal to one. If

one

ormore

workers takeup

their privatealterna-tive,

some

replacement workersmust

be hired,and

output per workerand

the

wage

are equal to 7.It isclear that the solution to the problem facing each worker has the following form: Stay if c is less than

some

threshold c*, otherwise leave.To

characterizec*, think of the decision problem facing one worker. Ifhe leaves

and

takesup

hisalternativeopportunity, he will receive c.

Suppose

hedecides instead tostay.Given

that, by symmetry, the (n—

1) other workers alsohave

a thresholdequalto c*, the probability that they all stay is given by (F(c*))

n_1

.

Expected

outputper worker,

and

thus thewage

hecan

expect to receive ifhe stays, is thus equalto (F(c*))n_1

+

(1-

(F(c*))n-1

)7.

The

threshold level c* issuch that hemust

be indifferent

between

leavingor staying,so that:» n—

1

c*

=

7

+

min(l,(-)

)(l-

7

) (3-1)

c

Expected

output per worker,and

thus the expected wage, are givenin turnby:Jio

=

7

+

min(l,

fy

)(l-7)

(3-2)8. Notethedifferentexponentsin (3.1) and (3.2),(n

—

1)versusn.Each workerknowshisownalternativeopportunitywhen choosingwhethertostayornot, and thus the uncertaintycomes

fromwhatthe n

—

1otherworkerswilldo.Theexpectedwage isthe unconditional expectationofthewage anddepends onwhatallnworkersdo.Thedifferencebetweenc* and

w

goestozeroDisorganization 1

The

solutiontoequation (3.1)can

beone

of three types,depending

on

the valueof c.

These

three cases are represented in Figure 5,which

plots both sides ofequation (3.1)

on

thevertical axisagainstc*on

the horizontal axis.The

figureisdrawn

assumingvalues ofn

=

5,and 7

=

.2.The

left-hand-side of the equationisrepresented bya45-degree line.

The

righthand

side isrepresentedby acurvewhich

isinitiallyconvex, turning flat at c*=

1.• Forlowalternativeopportunities, thereisonly

one

equilibrium,inwhich

allinitial workersdecide to stay, leading to a level ofoutput per workerequal

toone.

InFigure 5, the only equilibrium corresponding tothe case

where

c=

.3is at point A.• For intermediate alternative opportunities, there are two equilibria (the

equilibriumin-betweenisunstable usingstandardarguments),

one

inwhich

all workersstay

and

output per workerisone,and one

inwhich most

work-ersarelikely to leave,

where

c*,and

inturnexpected outputper worker, are close to 7.InFigure5, forcequal to .7, the twoequilibria are atpoints

A

and

B.At A,

c* is 1.At

B, c* (and the expectedwage

from (3.2)) isveryclose to .2: theprobability thatat least

one

workerwill leave isveryhigh.• For higher alternative opportunities

—

for c>

1—

there is a unique, low activity, equilibrium.In Figure 5, for c

=

1.1, the only equilibrium is at point B,where

c*,and

the expected wage, areboth equal to a valueclose to .2: production in the

statesectoris veryunlikely.

lo CD

O

>

CD>

O

CD * CD Z3 ^_ -Q Z5 CT UJ LO CD ZSO

ood

CO *.d

<->^3-d

CNId

o

o

I01

80

90

V0

Z'O O'O*D

(1)

The

first istheexistence, oversome

range,ofmultipleequilibria. This resultisnot

due

toprivateinformation.To

see this, note thateven

when

workershave

an

alternativeopportunity equal toaknown

valuec,then, forvalues ofcbetween

7

and

c, therearetwo

equilibria,one

inwhich

all workers stay in the state firm (the efficientoutcome)

,and one

inwhich

all workers takeup

their alternativeopportunity.

Is

one

equilibriummore

likely to prevail?The

arguments here are standard.On

the

one

hand, theequilibrium with high productionisParetosuperior.The game

is

one

ofpurecoordination, so ifthe workerscan

talk beforehand, theyshouldbe able to coordinate

on

the equilibriawhich

is better for all of them.On

theotherhand,ifeach workerbelievesthatthere is

some

probabilitythatsome

otherworker will irrationally refuse to participate, then the high-equilibrium

can

un-ravel.

As

n becomes

large,even

a small probability thatone

worker willirra-tionallyrefuse to participate

can

lead to the rational collapse ofoutput.This aspect of the

model

captures the fact thatcomplex

production processes,which

require the contribution ofmany

specific workers (or/andmany

specificsuppliers) imply

complex

coordination problems.A

reflection of these problemsis the potential presence of multiple equilibria.

The

argument was

firstmade

byBryant [1983] in the contextof

Western

Economies. But the prevalence ofspe-cific relations (and

we

shall argue in the next section, the lack ofmechanisms

designedtohandle suchcoordination problems)

makes

itmore

relevantforcoun-triesin transition.

Some

firmsmay

disappearsimplybecause theyareexpectedto,either bytheir suppliers or their essential workers.

informa-Disorganization 19

tion

and

interactionsbetween

decisions given the timing ofdecisions. It is the rapidcollapse ofstate outputassoon

asthe probability that at leastone

privatealternativeexceedsthe

wage

underefficientproductioninthestatefirmbecomes

positive.Forexample,forthecase

where

c=

1.1inFigure5 (sothat theexpectedvalue of private opportunitiesisonlyequal to.55,

compared

to 1 inthestatefirmif workers stay) the probability that all initial workers stay in the state firm is

nearly equal to zero,

and

expected productionperworkerin thestate firmisveryclose to .2, a highly inefficientoutcome.

To

seewhy

output collapses, note that assoon

ascisgreaterthanone, there isachance

that aworkerwill leave.The

wage

thatremaining workerscan

expect toreceive is thus reduced in proportion to the probability thatat least one worker

will leave. Inturn, thisreduction intheexpected

wage

promptsmore

workers toleave,

and

so on.The

effect ofhigher values ofn

is to magnify the interactionsbetween

the workers' decisions. For example, for c=

1.01, expected output perworker inthe state firm isequal to .92 if

n—

2, butfalls to .21when

n=3.

9This aspect of the

model

appears to capture anumber

of aspects oftransition.It captures the idea that crucial

managers

may

leave a firm, despite potentiallylarge payoffs from turning it around, because they are not sure that others will

stay

around

longenough. Ifwe

returntoan

interpretationof themodel

withsup-9. Toseetheroleoftimingdecisions, theseresultscanbecompared tothosewhichobtainwhen

workers decide whetherornotto taketheir private opportunity afterhavingobserved the

de-cisionsofothers. In that case, the probability thatallworkersstay in the state firm isequal to

(l/c)n, and expected outputperworkerin thefirmisequal to7

+

(l/c)"(l—

7).Forc=

1.01,pliers rather than workers, the

model

isconsistent with anecdotal evidence thatsuppliers are often very reluctant tosupplystatefirms, because ofthedifficulties

ofgetting paid. Ifthey are not paid

on

delivery but only ifthe firm succeedsinproducing

and

sellingitsproduction, then,just like workersinourexample,sup-pliers

become

residual claimants, (this raises the issue ofwhy

state firmsdo

notpay theirsuppliers

on

delivery.More

on

thisinthenextsection.)The

probabilitythat

one

ofthem

will notsupplyleadsall ofthem

tobe learyofsupplying,leadingtocollapse of the statefirm.

4

Managing

specificityWe

have

shown

throughthreeexampleshow

specificityand

complexitymay

havecombined

toleadtoa largedecrease ofoutputduring transition. Buttheseexam-plesraiseageneral issue.Ifanything, theproductionstructure inthe

West

iseven

more complex

thanit isin theEast.Why

aren'tproblems arising fromspecificityasseverein theWest?

We

have

alreadyhintedatsome

ofthe answers:(1) First,intheWest,

many

goodsaretradedinthick markets, markets withmany

buyers

and

many

sellers.And

while formany

intermediate goods, firmsdeal withonly

one

supplier, there are likely to be other potential suppliers,and

shiftingsuppliers

may

be difficultbut not impossible.For

many

goods however, thick marketscannot be created overnight.There

arejust not

enough

suppliers orbuyersin theeconomy

tostart with;new

firmsmust

Disorganization 21

increases the potential

number

of buyersand

sellerscan

clearly help here.In-deed,

one

of the arguments for imposingconvertibilityand

low tariffs in Polandin

1990

was

indeed to limit themonopoly power

ofdomestic firmsby increasingcompetition,

an argument

closelyrelated to ours (Sachs [1993]).(2) Second,thereis

more

scopeforcontractstohandle problemscreatedbyspeci-ficity.

The

potential role ofcontractsinsolving or alleviatingproblemsofspecificity isclearest in our first example. In that model, ifproducers

can

sign bindingcon-tractsbefore productiontakesplace, thentheywill avoid hold-upproblems,

and

achieve

an

efficient outcome. Total output will not declinewhen

privateoppor-tunities improve.

There

is little questionhowever

that the scope for contracts to alleviateprob-lemssuchas hold-upsis

more

limited inthe East.The

deficienciesofthe currentRussian legalsystem

have been

pointedout bymany

(forexample

Greifand

Kan-del [1994]): Contractenforcement is

weak

(in our example, producershave an

incentive ex-post to renege

and

offer a lower price to their suppliers. Contractenforcementistherefore crucial).Firms have few assets

which can

beseized,and

thus less to lose from breaking a contract. This last aspect takes us to the next

point.

(3)

Most

statefirms in transitionare shorton

"cash" (morepreciselyhave

limitedliquid assets,

and

limited access tocredit.)The

potential roleofcashinreducingproblemscoming

fromspecificityisclearestin our third example. Consider the case

where

there aretwo

equilibria,one

inforcing thefirm to hireless efficientreplacements.

A

commitment

by the firm topay

each

existingworkerawage

ofone, independentlyofwhat

theother workersdo, will lead all workers to stay,

and

will sustain the efficient equilibrium, atno

cost to the firm.

Thus, firmswith "deeppockets"can alleviate

some

of the problems arising fromspecificity.10 But state firms in the former Soviet

Union

typicallydo

nothave

such deep pockets: wages typically exhaust

most

of revenues, firms have limitedaccess tocredit,

and

many

are close tobankruptcy.Under

these conditions, theyhave

no

easyway

ofconvincing theirworkers tostayor their suppliers to supply.This

argument

points to the role offoreign direct investment: foreign firmstyp-ically have

deep

pockets.They

can paysupplierson

delivery; theycan

crediblypromise to pay theirworkers

even

ifthingsgo wrong.They

can

therefore avoidtheproblemsof coordination facedbystate firms.

(4)

While

state firms were oftenmore

vertically integrated than in the West,the type ofvertical integration

needed

to alleviate problems ofspecificityduringtransition isdifferent from

what

it was inthepast.The

reasonto verticallyintegrateundercentralplanningwastheimperfectabilityof the central planner toenforce timelydelivery of

some

inputs, leading firms toprotect themselves against such disruptions. Sachs [1993] gives the

example

ofan

industrial firm installing pigpens to raise pigsand

insure the delivery offoodto theirworkers inthe face offoodshortages.

The

typeofverticalintegrationneeded

in transition, as well aslateron,islikelytoDisorganization 23

bedifferent. It is

most

needed

forthose inputswithahigh degreeofspecificity,and

thus alarge potentialforseriousbargainingproblems. Pigpensarenottheanswer

anymore: markets in agricultural goods

have

eliminated the problem. But theproblem

may

now

be aspecific engine part,which

was easy to getunder

centralplanning butis

now

available fromonlyone

firm, raising issues ofspecificityand

bargaining.

Thus, the existingstructure ofvertical integrationcan onlyplay a limited role in

transition.

And

creatingnew

vertically integratedstructuresofproductionbothhassharplimits

and

takestime.The

argumentsherearestandard. First,chains ofproductioninterlock.

When

suppliershave

more

thanone

buyer,which

supplierintegrateswiththebuyer?Second,ifverticalintegrationistobe achievedthrough

the purchase ofexisting firms, thebargainingproblems

we

saw

become

relevant,this time notin the determinationofinputprices, but

now

inthe determinationofthe purchaseprice offirms. If

n

—

1 ofthe firms in ourfirstexample

verticallyintegrate, theremaininghold-outfirmhas

an

incentivetoholdoutfora large partofthe rents,

and

thus a high purchase price. Thus,no

firm willwant

to be thefirst tobe vertically integrated. Thissuggests

much

ofvertical integration needstoproceed throughthe

development

ofnew

activitieswithin the firm. This, likethe

development

ofnew

firms, takes time.(5) Fifth, but

we

thinkmost

important, the very nature of(any) transitionissuchthatthereislimitedscopeforlong-termrelations insolvingproblems arisingfrom

specificity.

Instable

economic

regimes, such as under central planning in the SovietUnion

an

important role in reducing inefficiencies arising from specificity,lb

see this,take for

example

ourthirdmodel,and assume

thatworkerswho

decidetotakeup

a private opportunitycannot

work

forthestatefirm in the future (onecan

againreplace "workers"by"suppliers" in

what

follows).Thismay

be either fortechno-logical reasons (they have to

move

to another city) or because it is the optimalpunishment

from the point ofview of the state firm.Then,

if privateopportu-nities are temporary, workers will think twice about leaving.

More

formally, theywill use a

much

higher threshold, a higher value ofc*, for decidingwhether

totake

up

aprivate opportunity.The

result willbeahigherprobability thatworkersstay,

and

higherexpected productionoverall.In that context, the value ofc* will

depend

cruciallyon

the probability that thefirm is still there

and

relieson

thesame

workers in the future. Ifthisprobabilityis low, then workerswill

behave

opportunistically, in away

close to thatcharac-terized intheprevioussection. But bythe nature of transition, this probabilityis

indeed likelytobe lowin transition: Transition implies that

many

state firmswilldisappear,

and

that,even

ifthey survive, they will have tochange

operations aswell as

many

oftheir suppliers.In a neo-classical

benchmark,

if it took time fornew

more

productive firms toarise following transition, state firms

would

continue producing until theywerereplacedby new,

more

efficient firms.The

argument

we

havejustdevelopedsug-gests that the

mere

anticipation thatmore

efficientprivate firms will eventuallyappearcan lead to areduction inproductivity in the state firms. It

may

alsoex-plain

why

the pre-official transition period in the SovietUnion

wascharacter-ized by increasing disorganization

and

decreasing output, as the shortening ofDisorganization

25

some

evidence that the degree towhich

state firms felt theyhad

to satisfy theplan decreased in the Soviet

Union

with the increased likelihood of reform inthe mid-1980s.

n

This line of

argument

may

explain alsosome

ofthe differencebetween

theex-periences of

China

and

EasternEurope

during transition. China'slower level ofindustrial development,

and

itsexplicit policyof decentralizing industrytomany

smallfactoriesimplies thatproblemsofspecificitywerelessinthefirstplace (Qian

et al. [1996]).

And

the ability of the Chinesegovernment

tomaintain politicalcontrol

meant

thatcentralized allocationwas

not fullyreplacedbydecentralizedbargaining.

And

China'scommitment

to maintain state firms, using subsidies ifnecessary,

may

have

lengthened horizons, allowing for a larger roleoflong-termrelations

between

firmsand

theirsuppliers,and

thus avoiding thecollapse ofstatefirms in the face of

new

private opportunities. This last point naturally takes usto a discussion of the policy implicationsofour theory.

(6) Policy implications.

Suppose

that in a neo-classicalbenchmark

(i.eabsent theeffectswe

have

focusedon

so far), absent subsidies,many

state firmscan

be expected todisappear overtime.

The

argument

we

have developed implies that, once the implications ofspecificity are taken into account, this

may

well lead to the immediate collapse11.This argument canalso explain theopposition of industry tolaws requiring firms toprovide

workersadvance notificationof plantshut-downsand whysomefirmsdecide simplytopay their

workersseverance pay rather than providingnotice. Ellickson [1989] notes thatatthetime ofthe collapseof thenineteenth centurywhalingindustry, thenormsof cooperation thathadevolved

ofthosefirms.Shorterhorizons

may

leadsuppliers tobehave

more

opportunisti-cally, leading tothe collapse ofstate production.

By

thesame

argument, acom-mitment

by thegovernment

tosubsidize state firmsforsome

timemay

avoidtheirimmediatecollapse.12

Should

agovernment

commit

to subsidizing state firms,and

thus avoid acol-lapseofstate productionatthe beginning oftransition?This will

depend on

theexpected path of private opportunities,

on

the time path of c in our example. Ifefficientprivate firms (firmswithvalues ofcequal toorgreaterthanproductivity

in thestate firms) areexpected todevelop quickly, thena

commitment

tomain-taining state firms for along time islikely tobe overlycostly. It

may

bebetter toaccept the fall in initial output, in

exchange

forhigher productionsoon

after. Ifhowever, the

development

ofan

efficientprivatesector isexpected totakemore

time (ifcisexpected tobe high

enough

tocreateproblemsof bargaining,but lowenough

that state production dominates private production for a long time), itmay

then bejustified tocommit

to subsidize state firmsforsome

time,and

avoidtheir immediatecollapse in the face ofmediocreprivate opportunities.

There

are clearlyother implications ofsubsidieswe

have not taken into account12.Thinkofsubsidies by thegovernment asaffecting the probability that the state firm will be

alive atany point in the future.

A

high enough probability will lead suppliers to increase the threshold atwhichthey takeuptheir privateopportunities. Technically, thecommitmentof thegovernmentmustbesuch thatthere isa positive probability, howeversmall, thatthestate firm

survivesforever. Theargumentisstandard: if it wereknown thata firmwas going to disappear withcertainty atsomefuturepointin time, thingswouldunravel,and thefirmwouldcollapse at

Disorganization

27

here: subsidies

may

reduce the incentivesofstatefirms to adjust. Subsidieshave

to be financed,

and

through the tax channel, slow thegrowth

ofnew

privatefirms.

And

in the end, politicaleconomy

considerationsmay

wellstilllead totheconclusion that the only

way

to stop subsidies is to stopthem

at once. But ourtheory provides at least

one

respectableargument

in favorof gradualism.When

the

emergence

of efficient private firms is likely to be slow, acommitment

bythe

government

to subsidize state firms forsome

timemay

avoid theirimmedi-ate collapse,

and

avoid a large inefficient decline in output at the beginning oftransition.

5

Empirical

Evidence

As we

went

along,we

gave anecdotalevidenceofdisorganization.Inthissection,we

attempt togivemore

formal evidence aboutthe relativeimportance ofdisor-ganization, both over time

and

across countries in transition.To do

so,we

relyon

measuresofreported shortages ofrawmaterialsand

intermediate productsbyfirms.

Two

remarks are in order hereWhat

firmsmean when

they report "shortages" is admittedly unclear.And

it isalsonotclear

whether

thebreakdowns

insupplywhich

occurin ourthreeexam-plesshould be calledshortages.

There

are, however,no

measuresof"breakdowns

in supply", while there are measures of reported shortages.

And

it is plausiblethat firms facing

breakdowns

in supply as inour exampleswould

reportthem

asshortages. Thus,

we

arereasonably confident thatreported shortagesare adecentWe

focuson

shortages ratherthansome

of theother implications ofourexamplesbecause most alternative theoriesofthe output decline

do

not naturallypredictshortages.13

There

isone

exception: shortagesmay

reflect the effects ofpartialprice liberalization, along the lines of

Murphy

et al. [1992]. In most republicshowever, prices have

now

been

mostly liberalized,so that partialpriceliberaliza-tion probablyplays a limited role inexplaining shortages at thispoint.14

We

read the available evidence as suggesting that disorganization has played alimited role in the major Central

European

countries,some

role in Russiaand

the Baltics,

and

a majorrole in the otherrepublics.(1) Since 1992/93, the

OECD

hascarriedout asurveyof firms in manufacturingina

number

ofCentralEuropean

and

Balticcountries,askingthem

aboutfactorslimiting production in manufacturing.

The

strength of these data is that theycome

fromroughly identical surveys. Unfortunately, theydo

not cover the earlyperiod oftransition,

where

disorganization islikely to havebeen

relativelymore

important.

The

evidence from these surveys issummarized

in table 1:Table 1. Percentage

of

firmsexperiencing shortagesof

materials.13.Phenomena such aswagecompression in statefirmscompared toprivate firms (forexample

Rutkowski [1996] forPoland, Kollo [1996] forHungary), thecollapseof inter-republican trade,

cannibalization ofmachines, "spontaneous privatization" and the carvingup offirms, are also

consistentwithourstory. The problemis thatthey are alsoconsistent withother explanations, includingefficientreorganization.Thevolumeoftrade maywellhave been toohigh.

Cannibal-izationofmachinesor offirmsmaybeefficient, andso on.

14.Forasurvey ofprogressonprice liberalization asof 1995, seeEuropeanBankfor

Disorganization

29

min

percentmax

percent 1996-1 valueCzech

Republic 93-1 96-1 3 9 5Hungary

92-1 96-1 6 11 5 Poland 93-3 96-1 3 6 5 Bulgaria 93-1 96-1 15 33 25Romania

92-1 96-1 8 39 15 Latvia 93-1 96-1 21 32 21 Lithuania 93-3 96-1 13 43 17Source:

OECD

Short term indicators, 2/1996. Business surveyannex.Inthe threemajorCentral

European

countries,shortages of materialshave

playeda very limited role since 1992-1993.

The

numbers

are comparable to thoseob-tained from similar surveys offirms in

Western

Europe.Numbers

from Bergand

Blanchard [1994]

show

that,even

in 1990inPoland (the firstyear oftransition),

disruptionswere not

an

importantpartof thestory.The

proportion offirms citing"supply

and

employment

shortages" as a limiting factor in production was62%

in

October

1989,37%

inJanuary1990

(themonth

of the "big bang"), butdown

to

10%

byApril 1990.The

evidence from those CentralEuropean

countrieswhich

are doing less wellsuggests a larger role for disorganization. In Bulgaria

and Romania, two

of the countrieswith the largest drop inoutput, supply shortages playedan

importantrole

more

thantwo

years after the beginning of transition.The

same

is true of(2) Table 2givescorresponding

numbers

forRussia, since 1991 (fromasample ofabout

500

industrial firms,witha response rate of30-40%

over time).Table 2. Proportion

of

firmsin industrymentioning

the following constraints aslimits toproduction. Russia,

1991-1995

Insufficient Shortages of Shortages of Shortages of

Demand

Materials Financial Resources Labor1991 4 82 18 28

1992 51

46

45 81993 41 23 62 6

1994 48 19

64

5 ;1995 47 22

64

8Source: Russian

Economic

Barometer,1996

The

most

strikingnumber

is the proportion offirms experiencing shortages ofmaterials in 1991. This

however

is the last year before full price liberalization(which took place inJanuary 1992). 15

The

numbers however remained

high in1992,

and

arestill high bystandards ofmarket economies.Another

piece of evidence,which

speaksmore

directly todisorganization, istheproportion of

work

time infirms lost to full stoppages of production, by reason.The

time seriesare givenin table 3.15.Itwould beinterestingtofindouthowtheproportion offirmsexperiencing shortages evolved pre-1991.Thesurvey usedabovestarts in 1991.

We

havesearched forearlierones,sofarwithoutDisorganization 31

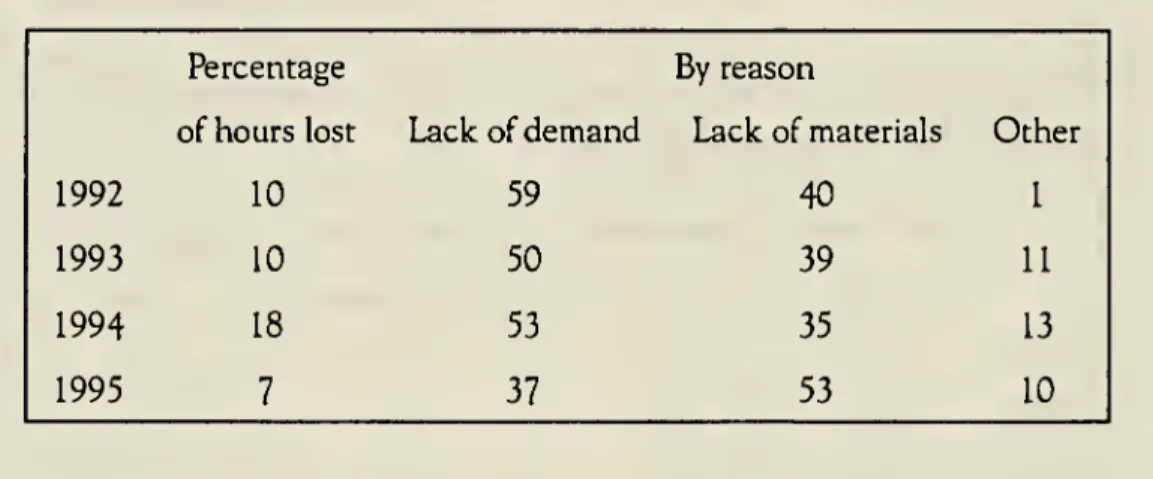

Table3. Percentage

of

working hourslostdue

tofullstoppageof

production,and

reasonsforit. Russia, 1992-1995.

Percentage

By

reasonofhourslost

Lack

ofdemand

Lack

of materialsOther

1992 10 59

40

11993 10

50

39 111994 18 53 35 13

1995 7 37 53 10

Source:

Goskomstat

Rossii, variousissues.1992

isAugust

only.1993

is theaver-ageover 4quarters.

1994

is theaverage ofMay

and

October.1995

istheaverageof

thefirsttwo

quarters.Lack

of materials appears to be themain

factor in explainingwork

stoppagesduring the period 1992-1995.

(3) Shortages of materials appear to play still a

more

important role in there-publics of the former Soviet Union. Table 4gives

some numbers

for the Kyrgyzrepublic.

The

numbers

are from a survey offirms by theILO

and

are for 1993,thus a year after price liberalization in the Kyrgyz republic,

and

one year afterthe collapse oftrade

between

the Kyrgyz republicand

the other republics oftheformer Soviet Union. (1993 is

however

a period of very high inflation—

23%

a

month

on

average—

.High

inflation is typically associated with disruptions inTable 4-

Main

businessproblems offirmsin industry. Kyrgyzrepublic,1993

Shortages of materials

Low demand

Other

factorsFood

processing 57 1330

Textiles 36 17 47

Non

metallic minerals 26 32 42Fabricatedmetals 31 22 47

Wood

and

paper 63 16 21Other

43 2136

Source: Windelletal. [1995] Proportion

of

firms, inpercent.These

numbers

are insharp contrast to those for, say Polandor Hungary.Short-ages of materials

seem

tobeing playinga central role.We

arenow

collectingmore

evidence from the other republics.

So

far, the evidence appears consistent withthat inTable 4.

The

shortages inTable 4seem

to reflect mainly internal disorganization, ratherthan the collapse of trade

between

republics.The

same

survey gives for eachindustry the proportion of materials

coming

from domesticand

non-domesticsources.

The

correlation across sectorsbetween

the proportion offirms citingshortages

and

theshareofmaterialscoming

fromnon-domesticsourcesisroughlyequal to zero.

Can

one

explain the differencesbetween

Central Europeand

the former SovietUnion?

Our

discussionsuggests anumber

ofpotentialexplanations. SpecificitiesDisorganization 33

say, Polandor the

Czech

Republic, leading toa larger collapse ofboth intra-and

inter-republican trade. Distance from the West,

and

thus thevolume

oftrade,and

thescope for foreign firms to alleviate problems ofspecificity,may

also haveplayed

an

importantrole.These

arehowever

speculations at thispoint.6

Conclusions

Transition was conceptualized in a recent

World

Bank

World

Development

Re-port[1996] as amovement

"From

Plan to Market."Ifourargument

is right,then amore

accurate, iflesssuccinct, titlewould

havebeen

"From

Planand

PlanIn-stitutions to

Market and Market

Institutions."Transitionmay

cause the existingorganization ofproduction tocollapse, leading to a largedecline inoutput until

new

institutionscan

becreated.The

evidence suggests that disorganization has played a limited role in CentralEurope,a

more

importantone intheBalticsand

Russia,and an even more

impor-tant

one

in theother Republics. Putanotherway,disorganization appearstohave

playeda

more

importantrole incountrieswhere

the output declinehasbeen

thelargest.

While

politicaleconomy

and

other considerationsmay

well lead to theconclu-sion that the only

way

to stop subsidies is to stopthem

at once, our analysisprovides

some

support for gradualist policies in dealing with state firms. Iftheemergence

ofnew

efficient private firms islikely to be slow, theremay

be a caseReferences

Atkeson, A.

and

Kehoe, E, 1992, Social insuranceand

transition,mimeo.

Banerjee, A.

and

Newman,

A., 1993, Occupational choiceand

the process ofdevelopment, Journal

of

PoliticalEconomy

101(2).Berg, A.

and

Blanchard,O,

1994, Stabilizationand

transition in Poland;1990-1991, pp. 51-92, in

The

transitioninEasternEurope,Volume

1,O

Blanchard,K. Froot

and

J. Sachseds,NBER

and

University ofChicago

Press, Chicago.Blanchard, O., 1996,

The

economics

oftransition in Eastern Europe,Oxford

UniversityPress, Oxford,

Clarendon

lectures, forthcoming.Bryant, J., 1983,

A

simple rational expectations Keynes-type model, QuarterlyJournal

of

Economics

3, 525-528.Caballero, R.

and

Hammour,

M., 1996,The

macroeconomics

of specificity,mimeo,

JuneMIT

Ellickson, R., 1989,

A

hypothesis ofwealth-maximizing norms: Evidence fromthe whaling industry, Journal

of

Law,Economics

and

Organization 5(1),mimeo

LSE.European

Bank

for Reconstructionand Development,

1996, Transition report,1995.

Greif, A.

and

Kandel, E., 1994, Contract enforcement institutions: historicalperspective