PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA

MINISTRY OF HIGER EDUCATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH Abd Elhafid Boussouf University - Mila

Institute of Literature and Languages

Department of Foreign Languages

Branch: English

A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Requirement of the Master Degree in Didactics of Foreign Languages

Presented by: Supervisor:

1) Amani MABOUD Dr. Fouad BOULKROUN

2) Roumaissa BOUANK

Board of Examiners:

Chairman: Ms. Lemya BOUGHAOUAS

Supervisor: Dr. Fouad BOULKROUN

Examiner : Dr. Layla ZOUREZ

Academic year : 2019 - 2020

In Search of the Cognitive Strategies Used in

Learning English Grammar

i

Dedication

I, Miss Roumaissa BOUANK, dedicate this humble work to the dearest people to my heart

to my supervisor Dr. FOUAD BOULKROUN for his patience and help. Indeed this work

would not have been finished without him.

To my mother Zahra source of love, care, happiness and success.

To my kind father Naaman may Allah bless him.

To my sisters and brothers:Ismahane, Rayane, Taki and Salah for their precious and

priceless love and support

To my lovely nephew Chihab who make all the stress and all the pressure fade away with

his presence

Special gratitude to the special person who has stood by me in every hard moment, my

Fiance Zakaria

To my life’s companions:Manel,Wissem, Hafssa and Ikram for the nice times we spent

together

To everyone who helped me one day

ii

Dedication

To God, our Lord and savior, for giving me strength and support to complete this work, for

the guidance in helping surpass all the trials that we encountered and for giving us

determination to pursue our study.

To my parents, whose affection, love, encouragement and prayers of day and night make me

the person I am today.

To my brothers and sister, for their support and inspiration

To my princess Riham, for lightening my darkness

To the one who always tells me to “Never say Never”

To my supervisor, Dr. Fouad BOULEKROUN, for his patience, support and help

And, also to Myself

iii

Achnowledgements

This work becomes a reality with the help and support of many individuals. We would like to extend our sincere thanks to all of them.

Foremost, we want to offer this endeavour to GOD Almighty for the wisdom he bestowed upon us, the strength, peace of mind and good health in order to finish this research.

We are highly indebted to Mr. Fouad BOULKROUN for his continuous support, patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. His guidance helps us all the time we spent in writing this research.

We would like to express our deepest gratitude for the jury members, Ms. Lemya BOUGHAOUAS and Dr. Layla ZOUREZ for accepting to take part in the examination of our research work, and for their time and patience.

Special thanks to Nouha for her worthy support, cooperation and time to help us with the administration of questionnaires.

iv

Abstract

The present study seeks to explore the cognitive strategies that are used by EFL students in grammar learning. For this to obtain, three research questions are raised: 1) What are the cognitive strategies that are employed by second year EFL learners when learning English grammar? 2) What are the most used cognitive strategies and the least used ones in grammar learning? 3) How should strategy training be carried out in EFL classrooms for an effective use of learning strategies, in general, and cognitive strategies, in particular, in learning grammar? To answer the research questions, the data are collected through two questionnaires administered to the participants via emails. The sample of the study consists of eighty one EFL students who are currently in their second year and ten EFL teachers at the Department of Foreign Languages, Mila University. Upon analysis of the data, the results show that second year EFL students use a wide range of cognitive strategies in grammar learning. It is found that the most used strategies are paying attention to the teacher’s feedback and to grammar when writing whereas memorization, repetition, and practice exercises are the least used ones. The findings also reveal various suggestions for an effective classroom implication of strategy training. The study ends up with a number of pedagogical recommendations for teachers, students and future research, along with a discussion of its limitations.

Key words : Cognitive/language learning strategies, Grammar learning, Grammar cognitive learning strategies, Strategy training, EFL students.

v

List of Abbreviations

ALM: The Audio-Lingual Method CLS: Cognitive Learning Strategies

CLT: Communicative Language Teaching DM: Direct Method

EFL: English as a Foreign Language

GCLS: Grammar Cognitive Learning Strategies GLS: grammar learning strategies

GTM: The Grammar Translation Method L2 : The Second Language

LLS: language learning strategies SBI: Strategies-Based Instruction TL: the target language

vi

List of Tables

Table 2.1. Allocation of Grammar Learning Strategies (GLS) in English as a Foreign

Language Class……….………45

Table 3.1: Students’ Age ……….………..…………..……….59

Table 3.2: Students’ Gender .………..………60

Table 3.3: Years of Studying English .……….…………..………..61

Table 3.4: Liking English ……….…………...62

Table 3.5: Students’ Interest in Studying Grammar …….………....………….62

Table 3.6: Students’ opinions Towards the Importance of Grammar in Language Learning …..… ……….………..…63

Table 3.7: Students’ Level in Grammar ……….………..………..64

Table 3.8: Teachers’ Method of Teaching Grammar (Explicit vs. Implicit)....……….……..65

Table 3.9: Teachers’ Method of Explicit Grammar Teaching (Deductive vs. Inductive) ... ...66

Table 3.10: Teacher’s Method of Grammar Teaching vs. Learner’s Preference …….…..….67

Table 3.11: Teacher’s Feedback ……...……….………..……68

Table 3.12: Explicit Vs. Implicit Teacher’s Feedback …...……….……….……….69

Table 3.13: Explicit Vs. Implicit Feedback Type Preference ………..…………69

Table 3.14: Students’ Learning Style ...………...……….…………...70

Table 3.15: Students’ Attention To Grammar Rules When Speaking ……..…………...…..71

Table 3.16: Students’ Attention To Grammar Rules When Listening...….72

Table 3.17: Students’ Attention To Grammar Rules When Writing ……...………73

Table 3.18: Students’ Attention To Grammar Rules When Reading ………...…...………….74

Table 3.19: Reading For Pleasure And Watching Television By Considering Grammar... ……….……...…….…..74

vii

Table 3.20: Learning Grammar by Memorising Rules ………..……….75 Table 3.21: Discovering Grammar Rules Through Example Analysis ………..……..76 Table 3.22: Extracting The Rules by Oneself to Better Understand Grammatical Forms

………..………...……..76 Table 3.23: Students’ Use of Guessing and/or Contextual Clues for Comprehension... ………...………...……….77 Table 3.24: Students’ Use of Imagery for Understanding and Remembering New Information ……….……….……….78 Table 3.25: Students’ Use of Elaboration ………...……….……..79 Table 3.26: Students’ Use of Transfer for Comprehension/Production ….……...…….…….79 Table 3.27: Students’ Use Of Note-Taking In Grammar Learning ….………..……….80 Table 3.28: Students’ Asking for Clarification and Examples …………...………….…..81 Table 3.29: Students’ Use of Translation.. ………..………..………82 Table 3.30: Repeating Rules and Structures to Oneself or Rewriting Them Repeatedly .…..… ………..………82 Table 3.31: Practice of Using Specific Grammar Structures In Communication …………....83 Table 3.32: Doing Grammar Practice Exercises …….………..….84 Table 3.33: Students’ Application of New Rules in Production ………..…………..……….84 Table 3.34: Comparing tGrammar in Written/Spoken Language with the Grammar They Actually Use ………...……….….……….……...85 Table 3.35: Paying Attention to Teacher Correction ……….…..…86 Table 3.36: Students’ Attitudes Towards the Importance of Grammar Cognitive Learning Strategies ………...…..……..87 Table 3.37: Teachers’ Years of Experience………..……….90 Table 3.38: Teachers’ Years of Experience in Grammar Teaching ……….91

viii

Table 3.39: Teachers’ Attitudes Towards the Importance of Grammar Teaching…..……….92

Table 3.40: Explicit Vs. Implicit Grammar Teaching ………..93

Table 3.41: Deductive Vs. Inductive Explicit Grammar Teaching ……….………94

Table 3.42: The Most Effective Method ………..….……….…...95

Table 3.43. The Strategies Mostly Used in Grammar Learning...96

Table 3.44. The Effectiveness of Learning Strategies in Grammar Learning...97

Table 3.45. The Most Useful Cognitive Strategies for Grammar Learning ...98

Table 3.46. The Cognitive Strategies Mostly Used in Learning Grammar...100

Table 3.47. The Least Used Cognitive Strategies in Learning Grammar...102

Table 3.48. Differences in Students’ Use of Strategies...103

Table 3.49 Types of Differences in Students’ Use of Strategies...104

Table 3.50. Students’ Awareness of the Effectiveness of Cognitive Strategies for Grammar Learning...105

Table 3.51. The Importance of Sensitising Students to GLS and GCLS...106

ix

List of Figures

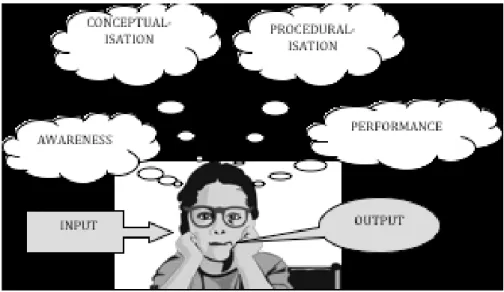

Figure 1.1.: A cognitive model of learning stages...17

Figure 2.1. Classification of Cognitive Strategies……….………..………….32

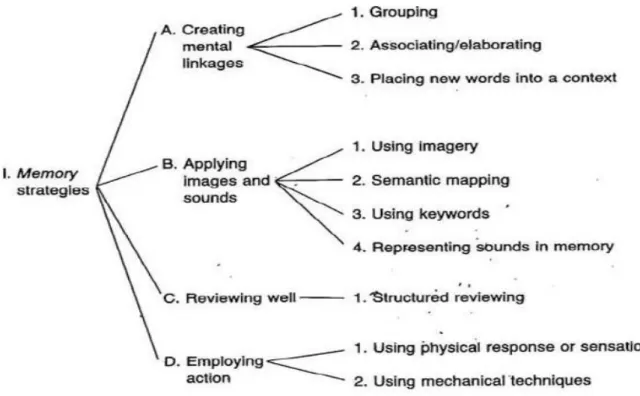

Figure 2.2. Classification of Memory Strategies………..…..…………..33

Figure 2.3. Classification of Compensation Strategies………...…..…………34

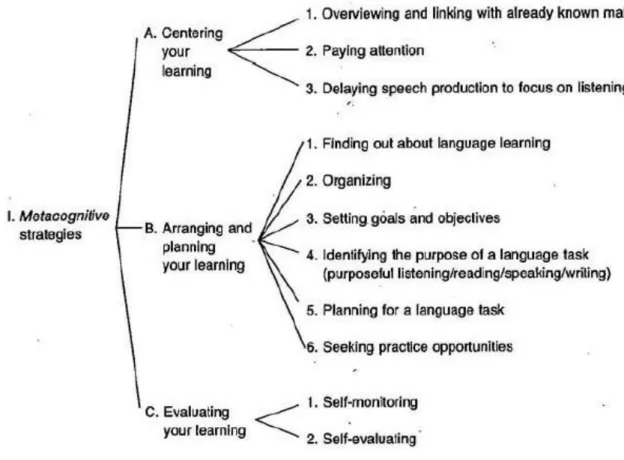

Figure 2.4. Classification of Meta-Cognitive Strategies………...………35

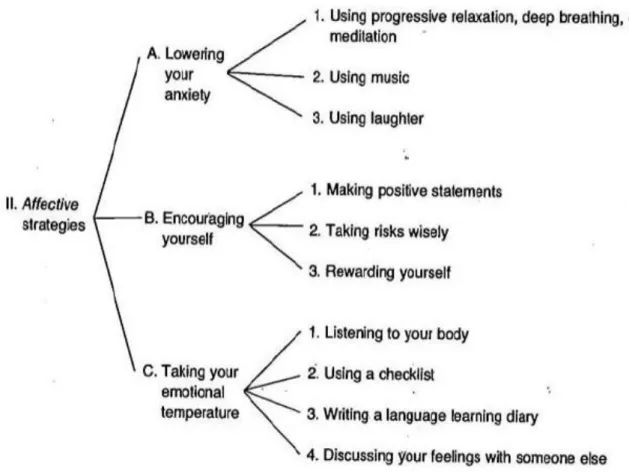

Figure 2.5. Classification of Affective Strategies………...………..37

Figure 2.6. Classification of Social Strategies………..38

Figure 2.7. Pawlak’s (2018) Classification of Grammar Learning Strategies………..43

Figure 3.1: Students’ age ……….………..…………..……...……….60

Figure 3.2: Students’ gender .……….………60

Figure 3.3: Years of studying English .……….……...……..………..61

Figure 3.4: Liking English ………....…………...62

Figure 3.5: Students’ interest in studying grammar …….………...………….63

Figure 3.6: Students’ opinions towards the importance of grammar in language learning …… ……….………..…64

Figure 3.7: Students’ level in grammar ………..………..65

Figure 3.8: Teachers’ method of teaching grammar (Explicit vs. Implicit)....………..65

Figure 3.9: Teachers’ method of explicit grammar teaching (Deductive vs. Inductive) ... ...66

Figure 3.10: Teacher’s method of grammar teaching vs. learner’s preference …….……..….67

Figure 3.11: Teacher’s feedback ………..……….….………..……68

Figure 3.12: Explicit vs. implicit teacher’s feedback …...………..………....………….69

Figure 3.13: Explicit vs. implicit feedback type preference ………..……..……70

x

Figure 3.15: Students’ attention to grammar rules when speaking ……..………..…..72 Figure 3.16: Students’ attention to grammar rules when listening...….72 Figure 3.17: Students’ attention to grammar rules when writing ……...………….…………73 Figure 3.18: Students’ attention to grammar rules when reading ……….…………..……….74 Figure 3.19: Reading for pleasure and watching television by considering grammar... ……….……...…….…..75

Figure 3.20: Learning grammar by memorising rules ………..…..………….75 Figure 3.21: Discovering grammar rules through example analysis ………...………..76 Figure 3.22: Extracting the rules by oneself to better understand grammatical forms ……..… ………..………...……..77 Figure 3.23: Students’ use of guessing and/or contextual clues for comprehension... ………...………...……….77 Figure 3.24: Students’ use of imagery for understanding and remembering new information ……….……….……….78 Figure 3.25: Students’ use of elaboration ………..…...……….……..79 Figure 3.26: Students’ use of transfer for comprehension/production ………...……….…….80 Figure 3.27: Students’ use of note-taking in grammar learning ….………..……..………….80 Figure 3.28: Students’ asking for clarification and examples …………...………..81 Figure 3.29: Students’ use of translation.. ……….…...………..………82 Figure 3.30: Repeating rules and structures to oneself or rewriting them repeatedly .……….… ………..………83 Figure 3.31: Practice of using specific grammar structures in communication ………...83 Figure 3.32: Doing grammar practice exercises …….……….84 Figure 3.33: Students’ application of new rules in production ………..…….………..…….85

xi

Figure 3.34: Comparing the grammar in written/spoken language with the grammar they

actually use ………...………...……….….………...85

Figure 3.35: Paying attention to teacher correction ……….………..…86

Figure 3.36: Students’ attitudes towards the importance of grammar cognitive learning strategies ………;;;;…………....……..87

Figure 3.37: Teachers’ years of experience………..……….……..……….90

Figure 3.38: Teachers’ years of experience in grammar teaching ……….……….91

Figure 3.39: Teachers’ attitudes towards the importance of grammar teaching…….……….92

Figure 3.40: Explicit vs. implicit grammar teaching ……….…..93

Figure 3.41: Deductive vs. inductive explicit grammar teaching ………94

Figure 3.42: The most effective method ………..….………...95

Figure 3.43. The strategies mostly used in grammar learning...96

Figure 3.44. The effectiveness of learning strategies in grammar learning...97

Figure 3.45. The most useful cognitive strategies for grammar learning ...99

Figure 3.46. The cognitive strategies mostly used in learning grammar...101

Figure 3.47. The least used cognitive strategies in learning grammar...102

Figure 3.48. Differences in students’ use of strategies...103

Figure 3.49 Types of differences in students’ use of strategies...104

Figure 3.50. Students’ awareness of the effectiveness of cognitive strategies for grammar learning...106

Figure 3.51. The importance of sensitising students to GLS and GCLS...107

xii

Table of Contents

Dedication……….…………. i Acknowledgement……….……….. iii Abstract………..….….….iv List of Abbreviations………...……….…...v List of Tables………...………...vi List of Figures……...………..………...ix Table of Contents…...………xiiGeneral Introduction

1. Statement of the Problem ……….12. Aims of the Study ………1

3. Significance of the Study ……….2

4. The Research Questions………...2

5. Means of the Research ……….……….………2

6. Structure of the Dissertation………..3

CHAPTER ONE: On Grammar Teaching and Learning

Introduction 1.1. Definition of Grammar...51.2. Should Grammar Be Taught? ...6

1.2.1. Arguments against Grammar Teaching...7

1.2.2. Arguments for Grammar Teaching...9

1.3. Teaching Grammar ...10

1.3.1. Explicit and Implicit Grammar Teaching...11

1.3.1.1. Explicit Grammar Teaching...11

xiii

1.3.2. Grammar in Some Language Teaching Methods and Approaches...13

1.3.2.1. The Grammar Translation Method...13

1.3.2.2. The Direct Method...14

1.3.2.3. The Audio-Lingual Method...15

1.3.2.4. The communicative Approach...15

1.3.2.5. The Cognitive Approach to Grammar...16

1.3.3. Types of instruction...17 1.3.3.1. Focus on Forms...17 1.3.3.2. Focus on Meaning... 18 1.3.3.3. Focus on Form...18 1.4. Corrective Feedback ...19 1.4.1. Explicit Feedback...20 1.4.2. Implicit Feedback...20

1.5. Grammar Learning Strategies...20

Conclusion...21

CHAPTER TWO: On Language Learning Strategies: Grammar Learning

in the Cognitive Turn

Introduction………..……….232.1. Language Learning Strategies………...……….23

2.1.1. Definition of Language Learning Strategies………..…..23

2.1.2. Characteristics of Language Learning Strategies………..……….25

xiv

2.2. Strategies and the Good Language Learner………..26

2.3. Classification of Language Learning Strategies………28

2.3.1. Rubin’s (1981) Classification………..………28

2.3.1.1. Direct strategies………..……….29

2.3.1.2. Indirect strategies………..……….29

2.3.2. Oxford’s (1990) Classification……….…30

2.3.2.1. Direct strategies………....30

- Cognitive Language Learning Strategies………..30

- Memory Language Learning Strategies………....32

- Compensation Language Learning Strategies……….……..33

2.3.2.2. Indirect strategies………34

- Meta-Cognitive Language Learning Strategies……….35

- Affective Language Learning Strategies………36

- Social Language Learning Strategies………37

2.3.3. O’Malley and Chamot’s (1990) Classification………...……….38

2.3.3.1. Metacognitive Language Learning Strategies………..………38

2.3.3.2. Cognitive Language Learning Strategies………..39

2.3.3.3. Social/Affective Language Learning Strategies……….………..40

2.4. Grammar Learning Strategies………..……….40

2.4.1. Significance of Grammar Learning Strategies……….……40

xv

2.5. Grammar Cognitive Learning Strategies……….……..42

2.6. Factors Influencing Learner’s Choice of Language Learning Strategies……….…46

2.6.1. Gender………...………46

2.6.2. Motivation………...……47

2.6.3. Learning Style……….47

2.7. Language Learning Strategy Training ……….…………48

2.7.1. Aims and Importance of Strategy Training………..48

2.7.2. Types of Strategy Training………..49

2.7.3. Options for Providing Strategy Training……….….50

2.7.4. Teachers’ Role in Strategy Training……….…53

2.7.5. Assessing Language Learning Strategies Use………..53

Conclusion………...…….55

CHAPTER THREE: In Search of the Cognitive Strategies Used in

Learning English Grammar:

The Field Work

Introduction ……….563.1. The Aims of the Research………..………...56

3.2. The Participants ………57

3.3. Data Collection Tools ………...57

3.4. The Students’ Questionnaire ………57

3.4.1. Description of the Students’ Questionnaire ………...58

3.4.2. Administration of the Students’ Questionnaire ………..………..58

3.4.3. Analysis of the Students’ Questionnaire ………..58

xvi

3.5.1. Description of the Teachers’ Questionnaire ……….87

3.5.2. Administration of the Teachers’ Questionnaire ……….…89

3.5.3. Analysis of the Teachers’ Questionnaire ………89

3.6. Discussion of the Main Findings ………..107

3.6.1. Discussion of the Main Findings of the Students’ Questionnaire……...………107

3.6.2. Discussion of the Main Findings of the Teachers’ Questionnaire……….…….108

3.7. Recommendations for Pedagogy and Research………..…….109

3.7.1. Recommendations for Students………...……109

3.7.2. Recommendations for Teachers ……….……109

3.7.3. Recommendations for Research ………110

3.8. Limitations of the Study ………...……….………..110

Conclusion ………...………..111

General Conclusion ………...………112

Bibliography ………...………...113

Appendices Appendix A The Students’ Questionnaire………..119

Appendix B The Teachers’ Questionnaire………..…………124

صخلملا……….128

1

General Introduction

1. Statement of the Problem

The fundamental purpose of the extensive research studies that have been conducted in the field of English as a foreign language (EFL) has been to find out what helps and what hinders the process of acquiring a new language. Grammar learning has been a highly controversial issue regarding its importance, the extent to which learners are required to attend to the formal aspects of English, and what strategies are to be used in this process.

It is not something that goes out of the ordinary that learners learn heterogeneously, taking different routes. Such differences are identified as variables affecting the learning outcomes. Research on the characteristics of the good language learner (Rubin, 1975; Stern, 1975) fomented the area of learning strategies, specifically cognitive strategies, which are said to improve the language skills of learners; notwithstanding, grammar strategies remained blatantly neglected and came to be considered as the second Cinderella. Thus, the motive to conduct this research study is the paucity of attention to the cognitive strategies in relation to English grammar learning.

2. Aim of the study

The desire to contribute to further knowledge and understanding in the area of grammar cognitive learning strategies is the motivation behind the current study. That is, this study seeks to determine the cognitive strategies employed by second year EFL learners at Mila University in the learning and use of grammar structures, and also to explore the cognitive strategies mostly used, and the least used ones. Furthermore, this study is set to reveal teachers suggestions for the integration of learning strategies, and grammar cognitive learning strategies, in particular, in EFL classrooms.

2 3. Significance of the Study

More research is needed into the field of cognitive learning strategies since it has not been satisfactorily explored, especially in relation to English grammar learning. The findings of the study at hand would raise teachers and learners’ consciousness to several cognitive strategies that would promote English grammar learning. Being aware of the strategies that learners use may help to regulate and automatise their learning. In order for the students to learn these strategies, their teachers should help them in the language classroom. Therefore, teachers may benefit from the findings of this study by providing their students with a successful grammar learning strategy training.

4. The Research Questions

In order to reach our aims, a number of research questions are raised:

- What are the cognitive strategies that are employed by second year EFL learners when learning English grammar?

- What are the cognitive strategies mostly used and the least used ones in grammar learning? - How should strategy training take place in EFL classrooms for an effective use of learning

strategies, in general, and cognitive strategies, in particular, in learning grammar?

5. Means of the Research

In order to gather data on students' grammar cognitive learning strategies, the questionnaire is opted for as a research tool for both students and teachers. The students’ questionnaire is administered to eighty one second year EFL students, who represent 1/3 of the whole population at Mila University. The questionnaire aims to reveal the students’ use of grammar cognitive strategies. On the other hand, the teachers’ questionnaire is conducted with ten EFL teachers who have experience in teaching grammar as a module. The teacher’

3

questionnaire is set to discover how teachers view those strategies and how they help students use them successfully in their classrooms.

6.

Structure of the Dissertation

This study consists of three chapters. The first and second chapters constitute the theoretical part of the study whereas the third chapter is about the field work. The first chapter is devoted for grammar teaching and learning. It first offers a definition of grammar as a concept, followed by arguments for and against its teaching. Then, it turns to discuss the area of grammar teaching in respect of a number of points. First, it deals with explicit and implicit grammar teaching, before moving on to discuss the place of grammar in various language teaching methods and approaches. After that, it accounts for the types of grammar instruction, and then discusses corrective feedback and its types. Finally, it highlights grammar learning strategies as a significant way to enhance grammar knowledge.

Chapter two sheds light on language learning strategies, with a special focus on grammar cognitive learning strategies. It sets out by presenting definitions, characteristics, importance of language learning strategies. It moves, further, to a discussion of the relation between the good language learner and the use of strategies, then to the different taxonomies of language learning strategies. In addition, it accounts for grammar learning strategies, their significance and classification. Next, the chapter sheds light on grammar cognitive learning strategies. Finally, it ends up with outlining the different factors affecting learner's choice of language learning strategies, in addition to an assessment of the use of such strategies.

The last chapter, which is the practical part of the research, addresses the raised questions, and attempts to achieve the aims of the investigation at hand. It provides an analysis of the data collected from the students’ and the teachers’ questionnaires, as well as a

4

discussion of the main findings. The chapter ends with some pedagogical recommendations for teachers and students as well as for future research, along with the limitations of the study.

5

Chapter One: On Grammar Teaching and Learning

Introduction

Grammar is one of the main concerns that have puzzled both foreign language teachers and learners due to its complex nature and great importance. Although it is widely accepted that grammar is the basis of any language and that mastery of grammar is a prerequisite for effective language learning, this subject is still controversial. Therefore, this chapter, in a brief overview, deals with some issues related to grammar starting with its definition and an account of arguments against and arguments for the teaching of grammar and of the explicit/implicit dichotomy as well. Then, a survey of the place of grammar within dominant language teaching methods and approaches is made. Next, the chapter sheds light on the types of instruction. After that, feedback is considered with some elaboration. Finally, grammar learning strategies are briefly introduced.

1.1. Definition of Grammar

It goes without saying that mastering grammar is key to success in language learning, yet the concept of “grammar” is not clear for everyone as it implies many aspects that are difficult, if not impossible, to be covered in one single comprehensive definition. The debate about grammar, then, begins at the level of basic definition. Many grammarians, based on their view on language, have defined grammar in different ways. According to Ur (1988), for example, grammar may be defined as:

The way a language manipulates and combines words (or bits of words) in order to form longer units of meaning […]. There is a set of rules which govern how units of meaning may be constructed in any language: we may say that a learner who ‘knows grammar’ is one who has mastered and can apply these rules to express him or herself in what would be acceptable language forms (p. 4).

Grammar is the study of what forms and structures are possible in a language. The analysis of language was at the sentence level. In other words, grammar consisted of the study of both syntax (i.e. the system of rules that cover the order of words in a sentence) and

6

morphology (i.e. the system of rules that cover the information of words). However, grammar has also to do with meaning. It communicates meanings, which can be at least of two types. The first is representational meaning, which means that grammatical forms represent the world. The second meaning is interpersonal, and it means that grammar helps people to interact. Moreover, grammar is linked to function; using one form, a speaker can express a variety of functions. In the same way, it is possible to express one function using different forms (Thornbury, 1999).

Newby (2008), on his part, gives grammar the following definition: “Grammar is a speaker’s knowledge of all the contrasts of meaning that it is possible to make within one sentence and his/her ability to use this knowledge in contexts” (p. 3). Grammar, according to this definition is both competence, the knowledge of the grammatical rules of the language in question, and performance, the ability to use this knowledge in real contexts.

1.2. Should Grammar Be Taught?

Teaching grammar has been singled out not suitable for harsh controversy among researchers for years. As Thornbury (1999) states, "in fact, no other issue has so preoccupied theorists and practitioners as the grammar debate, and the history of language teaching is essentially the history of the claims and counterclaims for and against the teaching of grammar" (p.4). According to Thornbury, the question ‘should grammar be taught?’ has, at least, two competing answers. According to the first, the teaching of grammar can have a detrimental effect; therefore, it should not be taught. According to the second, the teaching of grammar is advocated. Some arguments for both positions, as summarised by Thornbury, are given in what follows.

7

1.2.1. Arguments against the Teaching of Grammar

Grammar teaching is disfavoured for many reasons; six of the main ones are briefly mentioned here (Thornbury, 1999).

1.2.1.1. The knowledge-how argument

Language learning can be viewed as a skill or a complex set of skills. Accordingly, it is an experiential learning i.e. learning by doing and not learning by simply studying the language, because learners face struggles when they transfer their declarative knowledge into procedural knowledge. That is to say, when students know the grammar rules, it does not mean that they can apply those rules, so it is better to let them experience the language in classrooms instead of studying grammar directly.

1.2.1.2. The communicative argument

Communication skills are learned by communicating; therefore, a language should be used in order to be learned. In this way, the learner will unconsciously learn the grammar when dealing with activities that simulate real world communication, and target his communicative competence.

1.2.1.3. The acquisition argument

Krashen (1970) distinguishes between conscious language learning, which is the result of formal instruction, and unconscious language acquisition, which is a natural process by which people pick up their first and other languages. He argues that success in a second language is due to acquisition i.e. exposing the learner to the input in an environment that triggers his or her innate learning capacities. Hence, learning grammar is of limited use for communication ( as cited in Thornbury, 1999).

8

1.2.1.4. The natural order argument

Learners possess an innate Universal Grammar (Chomsky, n.d., as cited in Thornbury, 1999) which contributes to the process of explaining similarities in the developmental order of first and second/foreign language acquisition. Universal Grammar explains why all learners acquire some grammatical items before others, in a natural order, irrespective of the order in which they are taught. The natural order argument (Thornbury, 1999) claims that the grammar of textbooks cannot be a mental grammar.

1.2.1.5. The lexical chunks argument

Lexical chunks learning is about the memorisation of phrases and formulaic expressions (Thornbury, 1999). It plays an important part in language development. Having learned language chunks makes it easier for the learner to react in real-time situations, and it helps him to save time in real communication. In contrast to the traditional emphasis on sentence grammar, some writers have proposed a lexical approach to teaching that, among other things, promotes the learning of frequently used and fairly formulaic expressions rather than learning of abstract grammatical categories. The language chunks will be analysed later by the learner to infer grammatical structures and rules to be used anew. Therefore, chunks learning can substitute the learning of some abstract grammatical forms (Thornbury, 1999).

1.2.1.6. The learner expectations argument

Some students may want to focus on communication because they have studied grammar for a long period, or because they do not like grammar, or for other reasons, so they are not in need for more grammar; rather, they need to put their knowledge about grammar in use i.e. communication.

9

1.2.2. Arguments for the Teaching of Grammar

In favour of grammar teaching, Krahnke (1985, as cited in Terrell, 1991, p. 54) suggests that “much of the effort spent arguing against the teaching of grammar might be better spent on convincing true believers in grammar instruction that grammar has a newly defined but useful role to play in language teaching and in showing them what it is.” Thornbury (1999) states the following arguments for the teaching of grammar.

1.2.2.1. The sentence-machine argument

‘Item learning’ is part of the learning process. However, the number of items that one can retain or retrieve is limited. Inevitably, the learner will need to learn some rules that enable him to generate new sentences. That is, he will be in need of a grammar that provides him with the means to generate a huge number of original sentences. This way, grammar is a kind of ‘sentence-making machine’ without which it is impossible to use language creatively.

1.2.2.2. The fine-tuning argument

The teaching of grammar withholds any type of ambiguity. It enables the learner to convey a more intelligible and differentiated meaning than the simple stringing together of words. The knowledge of syntax and morphology contributes to a better understanding of the discourse as it provides semantic clarification.

1.2.2.3. The fossilisation argument

It is suggested that learners who receive no formal instruction are at risk of fossilising sooner than those who do receive such instruction. Without attention to form, the learner usually does not progress beyond the most basic level of communication.

1.2.2.4. The discrete item argument

Grammar allows the dividing up of the complex language system into smaller units, ‘discrete items’ that are digestible. Thereby, it reduces the enormity of the language learning

10

task for learners. As for the teacher, grammar enables a clear organisation of language teaching.

1.2.2.5. The rule-of-law argument

Grammar enables the transmission of knowledge, typically in the form of rules, from the teacher to the learner as this structured system can be taught, learned and tested. Grammar meets the need for rules, order and discipline in institutional contexts such as school.

1.2.2.6. The learner expectations argument

Students might well expect to learn a foreign language through grammar instruction as they assume that teaching grammar is a more systematic and efficient approach than picking up the target language in a non-classroom setting. If the teacher ignores this expectation by encouraging learners to experience language, he is likely to frustrate them.

1.3. Grammar Teaching

The teaching of grammar holds a central position in the language-teaching literature

and research. Grammar teaching can be considered as a description of the grammar that is

designed for teaching and learning purposes. Ellis (2006) identifies two types of definitions of grammar teaching: a narrow definition and a broad definition. In the narrow definition, Ellis describes grammar teaching as the traditional grammar teaching that involves “presentation and practice of discrete grammatical structures” (p. 84). Presentation has to do with the explanation of the rules of the language whereas practice captures the various activities a learner will take in the process of teaching and learning.

Most grammar book writers support this kind of grammar teaching description. Ur (1996) and Hedge (2000) also consider grammar teaching as being based on “presentation and practice”, a narrow definition composite of only two stages. Grammar teaching can be

11

conducted, as well, by means of corrective feedback on learner errors in the context of performing some communicative task (Ellis, 2006).

With regard to the broad definition, Ellis (2006) defines grammar teaching as involving “any instructional technique that draws learners’ attention to some specific grammatical form in such a way that it helps them either to understand it metalinguistically and/or process it in comprehension and/or production so that they can internalize it” (p. 84). On her part, Larsen- Freeman (1991) defines grammar teaching as "enabling language students to use linguistic forms accurately, meaningfully, and appropriately" (p. 280).

1.3.1. Explicit and Implicit Grammar Teaching

Over the years, there has been a growing concern among researchers, theorists and teachers alike about the ways in which grammar can be taught. Within foreign/second language contexts, two methods are of use: explicit and implicit grammar teaching.

1.3.1.1. Explicit Grammar Teaching

Explicit instruction is teacher‐centered instruction that focuses on clear behavioural and cognitive goals and outcomes that are, in turn, are made ‘explicit’ to learners. Explicit teaching clearly outlines what the learning goals are for the learner. It is an approach to teaching grammar that overtly presents grammatical rules (Harmer, 1987).

Scott (1990) clarifies that: "An explicit approach to teaching grammar insists upon the value of deliberate study of grammar rules, either by declarative analysis or inductive analogy, in order to recognize linguistic elements efficiently and accurately." (p. 779). In other words, explicit grammar instruction takes place either deductively, by giving the rules first and providing the examples later on, or inductively, by providing examples, then letting students extract the rules by themselves. In this approach, thus, learners study the target grammar consciously.

12

Some researchers emphasise the need for implicit instruction. They reject traditional grammar teaching pedagogy in which students are presented with grammatical structures explicitly in a decontextualised manner. The traditional model of grammar teaching consists of conscious presentation and manipulation of grammatical forms through drills and practice. It is suggested that learners should have opportunities to “encounter, process and use" the target forms in various ways, so that the form can become a part of their interlanguage (Nassaji and Fotos, 2004, p 130-131).

1.3.1.2. Implicit Grammar Teaching

Implicit grammar teaching, for Ellis (2009), is directed to enable learners to infer rules without awareness; as he puts it, "it seeks to provide learners with experience of specific exemplars of a rule or pattern while they are not attempting to learn it” (p. 16). Put another way, it is a way of grammar teaching that exposes learners to the target language to make them acquire the language as naturally as possible without stating rules. Therefore, the main aim of the teaching/learning process is an unconscious internalisation of the grammatical patterns through the communicative tasks they work on. To cut it short, the implicit approach to teaching grammar is an approach whose goal is orienting learners’ attention to specific grammatical structures without having to study them directly.

Implicit grammar teaching can be conducted through the use of the technique of input enhancement. This is defined by Nassaji and Fotos (2011) as “the process by which input is made more noticeable to the learner” (p. 39). In pedagogical contexts, input enhancement can have different forms. For instance, it can be internal or external. The former “occurs when the learner notices the form himself or herself through the outcome of internal cognitive processes or learning strategies” (p. 40). For example, “the learner may notice a grammatical feature as a way of processing input for meaning, such as paying more attention to content words than function words” (p. 40). The latter, however, “occurs when the form is

13

noticed through external agents, such as the teacher or external operations carried out on the input” (Nassaji and Fotos, 2011, p. 40).

Looking for the most suitable foreign language teaching/learning method that could work best for speakers of other languages is the one of the main concerns of researchers, yet there is not much agreement in this regard among them. Evidently, there is no best form of grammar instruction. The appropriate type of instruction is conditional upon the particular learning context. It is important, then, to keep a balance, if needed of course, taking into account the needs of the particular class being taught.

1.3.2. Grammar in some Language Teaching Methods and Approaches

A consideration of foreign language teaching over the years reveals a fundamental shift in the teaching of grammar. In a traditional approach to grammar teaching and learning, grammar, being a set of forms and structures, is the main focus of the syllabus of the textbook. Accuracy is important and enabling students to form correct sentences is emphasised (Newby, 2000, p. 1). In more recent years, there is less concern with grammar as such. What follows is a brief historical background of the development of language teaching methods and the place of grammar therein.

1.3.2.1.

The Grammar Translation Method

The Grammar Translation Method (GTM), also known as “The Classical Method”, was used first to teach classical languages, Latin and Greek. It is the most ancient method that appeared in the field of foreign language teaching. As its name suggests, it took grammar as the starting point for instruction with the purpose of helping students read and appreciate foreign language literature. An important goal of this method is for students to be able to translate each language into the other; if students can translate from one language into another, they are considered successful language learners. Through the study of the grammar

14

of the target language, it was hoped also that students will speak and write their native language better and grow intellectually (Larsen-Freeman, 2000).

In the GTM, the target language is divided into parts of speech which are taught deductively through an explicit explanation of rules. Hence, in the GTM classroom, learners are required to memorise those rules. They are also required to translate texts from the target to their first language. Developing learners’ academic capacities, among others, is one of the purposes of this method (Nassaji and Fotos, 2011, p.2).

The GTM can provide learners with good skills in reading and writing; however, it draws little attention to pronunciation; much time is spent talking about the target language (TL) and little time talking in TL. Besides, the teacher is the absolute authority in the classroom. Most of these drawbacks were criticised by educationalists and linguists. An increasing need for a somewhat different method was, then, warranted.

1.3.2.2.

The Direct Method

The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed a growing interest in the study of the spoken language. The Direct Method (DM) appeared, as a consequence. This method places aural and oral skills at the centre of language learning. According to the proponents of this method, second/foreign language acquisition is considered similar to first language acquisition. Therefore, the medium of instruction is the target language. Learners are encouraged to make direct association between the target language and meaning. Furthermore, grammar is taught inductively; language learners are, in fact, supposed to ‘pick up’ the grammar structures. Additionally, the syllabus is based on situations or topics, not discrete items, and meaning by using objects like pictures or realia (Larsen-Freeman, 2000).

The popularity of the DM declined in the twentieth century; it was criticised for having weak theoretical foundations, and its effectiveness depended on small classes and native speakers as instructors, and thus it failed to resist in larger classes.

15

1.3.2.3. The Audio-Lingual Method

The Audio-Lingual Method (ALM), also known as the Aural-Oral Method was prominent in the 1950s and 1960s. This method focuses on the teaching of speaking and listening before reading and writing. Therefore, the use of dialogues and oral drilling of basic patterns was the centre of instruction (Richards & Schmidt, 2010, p. 40). In contrast to the Direct Method, the

ALM is based on linguistic and psychological theories, namely structural linguistics and behaviourist psychology. Here, the focus shifts from studying grammar in terms of parts of speech to the description of the underlying structures and phonology. Similarly, behaviourist psychologists consider language learning as a process of habit formation and conditioning through memorisation and practice (Nassaji and Fotos, 2011).

Like any other method, this method fell out of favour because of its principles and procedures. As Richards and Schmidt (2010) point out, “Criticism of the audio lingual method is based on criticism of its theory and its techniques" (p. 40).

1.3.2.4. The Communicative Approach

The Communicative Approach, or Communicative Language Teaching (CLT), emerged in the 1970s. Opposing the Grammar-Translation Method, the Direct Method, and the Audio-Lingual Method, CLT holds that grammatical competence is one integral part of a wider communicative competence. As put by Thornbury (1999), “Communicative competence involves knowing how to use the grammar and vocabulary of the language to achieve communicative goals, and knowing how to do this in a socially appropriate way” (p. 18). The focus of this approach, then, shifts towards developing communicative competence rather than developing grammatical competence alone.

16

Moreover, CLT has two versions, namely the ‘shallow-end approach’ and the ‘deep-end approach’ (Thornbury, 1999). In the shallow-‘deep-end approach, language is learnt in order to be used. Grammar teaching, as such, is not completely rejected, yet it is dressed up in functional labels such as making future plans or asking about the way. In the deep-end approach, however, language is used in order to be learnt. According to this version, grammar instruction is a waste of time, as it is believed that learners are to learn the grammatical rules unconsciously through communicative tasks; for this reason, grammar instruction is rejected (Thornbury, 1999).

1.3.2.5. The Cognitive Approach to Grammar

The cognitive approach to learning has gained importance in recent years. The cognitive view of learning rejects the passive view of traditional approaches to grammar teaching and learning. O’Malley and Chamot (1990) suggest that “second language acquisition cannot be understood without addressing the interaction between language and cognition” (p. 16). According to this view, language is represented as a ‘complex cognitive skill’. Other central tenets of this theory are that “learning is an active and dynamic process in which individuals make use of a variety of information and strategic modes of processing”, and that “learning a language entails a stagewise progression from initial awareness and active manipulation of information and learning processes to full automaticity in language use” (O’Malley and Chamot, 1990, p. 217). Thence, language learning can be seen as an active progressive process starting with manipulating information to automatic use of the language, through stages.

Similar to this view is the stage-model used by cognitive psychologists as a processing model of learning. According to Newby (2008) this model can be adapted to see language learning both as a series of information processing and learning stages. He provides a relatively recent description of the cognitive stages that aims to identify stages of grammar

17

acquisition. The cognitive stages are shown in the figure below. There are four stages between the input (i.e. the materials provided by the teacher or the textbook and the pupil’s existing knowledge) and the output (i.e. what the pupil says or writes). Though this model is presented as discrete stages, they are not separate, but rather overlapping and recursive (Newby, 2008).

Figure 1.1.: A cognitive model of learning stages (Newby, 2008)

In the cognitive approach, the stages of learning take the learner’s rather than the teacher’s perspective and focuses on the tasks that must be accomplished in the human mind in each stage in order for grammar to be internalised. This model views grammar both in terms of competence and performance, which is similar to the communicative model in which language is seen in terms of both knowledge and skills (Newby, 2008).

1.3.3. Types of Instruction

At the heart of the discussion of instruction are the different types available to instructors. Three types are distinguished: focus-on-forms instruction, focus-on-meaning instruction, and focus-on-form instruction.

1.3.3.1. Focus-on-Forms

Focus-on-forms is the traditional approach which represents a synthetic syllabus. In focus-on-forms instruction, lessons consist of the linguistic items which learners are

18

encouraged to master one at a time, with little if any communicative use of the target language. Focus-on-forms has been criticised for being, among other things, a one-size-fits-all approach i.e. for giving no credit to individual communicative needs and learning styles, and for ignoring the role learners can play in language development. Hence, it results in decline of motivation and attention on the learners’ part (Long, 1998, p. 36-37).

1.3.3.2.

Focus-on-Meaning

Focus-on-meaning distinguishes itself from focus-on-forms, with regard to grammar instruction. In Focus-on-meaning, any direct grammar instruction is rejected, as language learning is claimed to be incidental and implicit. In this approach, lessons are purely communicative, and learners induce the grammatical rules of the target language from exposure to comprehensible input (Krashen, 1987; Long, 1998).

Focus-on-meaning, however, is problematic because, as Long (1998) argues, comprehensible input is necessary, but it is not sufficient to enable learners to be grammatically competent.

1.3.3.3. Focus-on-Form

As an alternative to both focus-on-forms and focus-on-meaning instruction, Long (1998) proposes focus-on-form instruction which calls for an integration of forms and meaning at the same time. According to him: “Focus on form refers to how attentional resources are allocated, and involves briefly drawing students’ attention to linguistic elements [...] as they arise incidentally in lessons whose overriding focus is on meaning, or communication” (p. 40). In the same line of thought, Ellis (2006) states that “focus on form implies no separate grammar lessons but rather integrated into a curriculum consisting of communicative tasks” (p. 101). Similarly, Nassaji and Fotos (2004) highlight that “focus on form involves the teacher's attempts to draw the student's attention to grammatical forms in the context of communication” (p. 131). In other words, the focus of such instruction is to

19

involve learners in communication without excluding attending to formal features of the target language; this is claimed to equip them with both fluency and accuracy.

Furthermore, while focus-on-forms is teacher-centred in approach, the third type of instruction is learner-centred. It respects the learner’s needs, makes room for the learner’s internal syllabus, and happens when the learner has a communication problem; thus, it meets the conditions that are optimal for learning (Long, 1998).

In what follows, Doughty and Williams (in press-b, p. 4, as cited in Long, 1998) make the relationships among the three approaches:

We would like to stress that focus on formS and focus on form are not polar opposites in the way that ‘form’ and ‘meaning’ have often been considered to be. Rather, a focus on form entails a focus on formal elements of language, whereas focus on formS is limited to such a focus, and focus on meaning excludes it. Most important, it should be kept in mind that the fundamental assumption of focus-on-form instruction is that meaning and use must already be evident to the learner at the time that attention is drawn to the linguistic apparatus needed to get the meaning across.

1.4. Corrective Feedback

When learners use the target language along with the concomitant grammatical forms productively, providing corrective feedback seems wise. Generally speaking, the term ‘feedback’ refers to the “information that is given to the learner about his or her performance of a learning task, usually with the objective of improving this performance” (Ur, 1996, p. 242). Feedback can have two distinguishable types: positive and negative feedback. In the former, the teacher confirms that the learner’s performance is correct. In the latter, the teacher signals the learner’s incorrect utterances. Corrective feedback is one type of negative feedback. Corrective feedback “takes the form of a response to a learner utterance containing a linguistic error” (Ellis, 2009, p. 3). That is, corrective feedback is the correction of the erroneous utterances produced by the learner. A further distinction can be made between explicit and implicit corrective feedback.

20

1.4.1. Explicit Corrective Feedback

According to Ellis et al. (2006), explicit feedback is of two main types: explicit correction and metalinguistic feedback. In explicit correction, the teacher directly signals the error and gives the correction. Metalinguistic feedback is defined by Lyster and Ranta (1997, p. 47 as cited in Ellis et al., 2006, p. 341) as “”comments, information, or questions related to the well-formedness of the learner’s utterance”.

1.4.2. Implicit Corrective Feedback

According to Ellis (2006), “implicit feedback occurs when the corrective force of the response to learner error is masked” (p. 99). In this case, there is no overt indicator that an error has been committed. This type of feedback is more compatible with a focus-on-form approach because it ensures that learners are more likely to stay focused on meaning (Ellis, 2006).

The importance of corrective feedback differs depending on the principles of the different language teaching methods and approaches. The challenge facing teachers in classes with learners of individual differences is how to handle this issue, in terms of its timing, what errors to correct, and how to correct them.

1.5. Grammar Learning Strategies

Central to the discussion on the teaching of grammar is a discussion of the strategies that can aid learners to learn the grammar of the target language. According to Fotos (2001, p. 280 as cited in Esmaili Fard, 2010, p. 4), “no cognitive model of second/foreign language grammar learning would be complete without considering strategies”. It seems, then, that the use of strategies can affect the learning of grammar.

It has to be admitted that there is scarcity of research on the area that tackles the strategies used in grammar learning; however, one remarkable exception is the attempt of Oxford et al. (2007) to define such kind of strategies. The researchers, based on a general

21

definition of language learning strategies provided by Oxford (1990), describe grammar learning strategies (henceforth, GLS) as“ actions and thoughts that learners consciously employ to make language learning and/or language use easier, more effective, more efficient, and more enjoyable” (as cited in Pawlak, 2018, p. 353). In a recent definition, Oxford (2017, p. 244) describes grammar learning strategies as “teachable, dynamic thoughts and behaviors that learners consciously select and employ in specific contexts to improve their self-regulated, autonomous L2 grammar development for effective task performance and long-term efficiency” (as cited in Pawlak, 2018, p. 353). This definition highlights all the key features of grammar learning strategies; thus, it can serve as a basis for future research.

On their part, Cohen and Pinilla-Herrera (2011) define grammar strategies as “deliberate thoughts and actions students consciously employed for learning and getting better control over the use of grammar structures” (p. 66).

In recent times, grammar instruction has been recognized as an essential and unavoidable component of language learning and use. Not questioning the need for grammar instruction in the field of foreign language learning, the complexity of grammar, the plethora of the methods available for teaching grammar that naturally have pros and cons, have oriented the research focus towards the learning strategies that may result in substantial gains in the learning of target language structures and of language as a whole.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the subject of grammar will, no doubt, continue to be a topic of interest for researchers and practitioners who desire to meet the needs of language learners.

Grammar instruction is considered one of the most difficult issues in language teaching. Once grammar is believed to be integrated into language classes for its importance, language teachers find themselves facing the problem, among many other problems, of how best to teach grammar. Moreover, it is not possible for them to teach students everything about

22

grammar. Learners will be able to use grammar conventions effectively if they learn them using the required strategies.In this way, the ongoing research on the subject of grammar and strategies will contribute to success in language learning, in general, and grammar learning, in particular.

23

CHAPTER II:

On Language Learning Strategies: Grammar Learning in the

Cognitive Turn

Introduction

The practical goal of teaching languages is to help learners to take charge of their learning by themselves. Recently, an international interest in language learning strategies (LLS) appears to have grown as many studies have shown that the appropriate use of those strategies strongly serves this aim. Investigations within the realm of LLS are not new endeavours as they garnered much attention in the 1990s; however, they have been in decline in the current century.

This chapter sheds light on language learning strategies in general, how such strategies can assist the process of learning the target language, the characteristics of such strategies, and their classification. It also clarifies the significance and classification of grammar learning strategies, with a focus on grammar cognitive learning strategies. Then, it discusses some factors that can affect the use of LLS. In addition, strategy training, its importance, and types are highlighted. Finally, an account is given to strategy use assessment tools.

2.1. Language Learning Strategies

2.1.1. Definition of Language Learning Strategies

To clear the ground about what language learning strategies are, the term strategy is worth defining first. According to Cambridge online dictionary, the term strategy is defined as follows: “a detailed plan for achieving success in situations such as war, politics, business, industry or sports, or the skill of planning for such situation”. Oxford (2003) notes that the

24

term ‘strategy’ has Greek origin: "Strategia" which means “steps or actions taken for the purpose of winning a war”; she points out that: “The warlike meaning of strategia has fortunately fallen away, but the control and goal directedness remain in the modern version of the word” (p. 8). At its simplest, a strategy is an action done to reach a goal.

In general education, the term ‘strategies’ is recognized under various collocations, such as learning strategies, learner strategies, learning to learn strategies. O’Malley and Chamot (1990) conceive learning strategies, in a broader sense, as “special ways of processing information that enhance comprehension, learning, or retention of the information” (p. 1). In the field of language learning, however, language learning strategies (LLS) are “specific actions, behaviors, steps, or techniques – such as seeking out conversation partners, or giving oneself encouragement to tackle a difficult language task – used by students to enhance their own learning” (Scarcella & Oxford, 1992, p. 63, as cited in Oxford 2003, p. 2). In a similar line of thought, Cohen (2003) defines LLS as: “the conscious or semi-conscious thoughts and behaviours used by learners with the explicit goal of improving their knowledge and understanding of a target language” (p. 280). Basically, learning strategies might be interpreted as techniques deployed in the learning of any subject: science, math, physics, languages and others whereas LLS refers more specifically to the processes used in language learning. The latter will be focused on in the rest of this chapter.

To synthesize, it can be deduced that learning strategies are goal-driven behaviours, thoughts, steps, or techniques that learners deploy to overcome learning problems, to improve their understanding, and to enhance the learning process, in general. Nonetheless, it remains unclear whether learning strategies are thoughts or behaviours i.e. observable or not, or both. However, Cohen (2003) deals with LLS as both thoughts and behaviours.

25

2.1.2. Characteristics of Language Learning Strategies

Besides defining LLS, early research was also concerned with the characteristics of these strategies. Oxford (1990, p. 9) proposes a list of twelve characteristics; LLS:

1. Contribute to the main goal, communicative competence. 2. Allow learners to become more self-directed.

3. Expand the role of teachers. 4. Are problem-oriented.

5. Are specific actions taken by the learner.

6. Involve many aspects of the learner, not just the cognitive. 7. Support learning both directly and indirectly.

8. Are not always observable. 9. Are often conscious. 10. Can be taught. 11. Are flexible.

12. Are influenced by a variety of factors.

2.1.3.

Importance of Language Learning Strategies

A great deal of research investigated the effect of the use of strategies on the improvement of learners’ basic language skills and sub-skills, namely speaking, listening, reading, writing, vocabulary, and grammar with less emphasis. Researchers shared ideas about the undeniable significance of LLS in the process of second or foreign language learning and teaching. Oxford (2003) cites Allwright, (1990) and Little (1991) who discuss the importance of applying strategies for promoting learning autonomy; they consider that learning strategies enable students to become more independent, autonomous, lifelong

26

learners. Language learning is, then, more effective if it is supported by the use of learning strategies.

As Oxford (1990) puts it, “learning strategies are especially important for language learning because they are tools for active, self-directed involvement, which is essential for developing communicative competence" (p. 1). Thus, knowing and developing some learning strategies, which is part of the strategic competence, is needed in order to be communicatively competent. In addition, skilled teachers, through an understanding of the learners own styles and strategies of learning, can attune their instruction to reach more learners; that is, in their lesson, for instance, teachers can encourage learners to use learning strategies that reflect their basic learning styles, or help them try out some strategies that are out of their zone of preferences by providing some tasks accordingly (Oxford, 2003). Thus teachers can manage the class not only from a teaching perspective, but also from a learner’s perspective

Learning strategies are important in second/foreign language learning and teaching. Chamot (2005) cites (Grenfell & Harris, 1999) stressing this importance for two major reasons. One reason is that an examination of the strategies used by L2 learners in their learning process provides researchers with insights into the metacognitive, cognitive, social and affective processes involved in language learning. The second reason is that less successful language learners can be better learners if they are taught new strategies.

2.2.

Strategies and the Good Language Learner

Studies of the good language learner have started ever since the seventies, specifically in 1975 with the original work of Rubin, entitled: “What the “Good Language Learner” Can Teach Us”. Throughout the next twenty years, witnessing a radical shift in the focus of L2 learning from teaching processes to learning processes, much ink has been spilled to elicit the characteristics of the good language learner (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990; Oxford,