Designing Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care:

A Practical Outcomes-Based Framework

by

Anubhav Arora

B.E. Polymer & Chemical Technology Delhi College of Engineering, 2010

Submitted to the Integrated Design and Management Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT AT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

JUNE 2019

@2019 Anubhav Arora. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or

hereafter created.

Signature of Author:

Certified by:

Signature redacted_____

Anubhav Arora Integrated Design and Management ProgramMayv24 2019

_Signature redacted

_1 C-Director, Initiative for Health Systems

Accepted by:

MASSACHUSETTS ISTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

JUN

2 7 2019

Dr Annei Quaadl ras Innovation & Senior Lecturer, Operations Management Thesis Supervisor

Signature redacted

Matthew S Kre y

Dire or Integrated Design and Management Progr m

,a 2421

Designing Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care:

A Practical Outcomes-Based Framework

by

Anubhav Arora

Submitted to the Integrated Design and Management Program on May 24, 2019 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Science in Engineering and Management

Abstract

Patients with comorbid physical, behavioral, and social needs-often referred to as high-need patients-tend to be the most frequent utilizers of the health care system. The US health care system, with fragmented behavioral and medical health care sectors, is unable to effectively meet the complex needs of high-need patients. This results in high health care utilization, increased health care costs, and poor health outcomes among this population. Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care (BHIPC) is widely promoted as a means to improve access, quality and continuity of health care services in a more efficient way, especially for people with complex needs. Hundreds of BHIPC programs are being implemented across health care settings in the US. However, the concept of BHIPC is wide-ranging, and it has been used as an overarching approach to describe integration efforts that vary in design, scope, and value. Research on how BHIPC is implemented in practice is limited. Practitioners and policymakers find it challenging to evaluate BHIPC programs and identify and scale-up its most critical elements.

In this thesis, I develop a design-based framework that deconstructs the ambiguous concept of BHIPC into a set of tangible design elements and decisions. Furthermore, in order to inform how BHIPC is implemented in practice, I use this design-based framework to examine the behavioral health integration programs in four community health centers in Massachusetts. I found that by just comparing the underlying design elements, it is difficult to assess BHIPC programs and distinguish a successful program from an unsuccessful one. I therefore recommend and propose an outcomes-based framework for differentiating and evaluating BHIPC programs. I also recommend that future researchers refine and standardize the process measures I introduce so that they can be used as guideposts by primary care practitioners to develop their BHIPC programs.

Thesis Supervisor:

Dr. Anne Quaadgras

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Matthew Kressy, thank you for believing in me, for seeing the love in people and nurturing it, for your idealism. Thank you for being who you are.

Dr. Anne Quaadgras, thank you for being the most supportive advisor and mentor one can ask for, for providing me with incredible guidance and freedom to explore, for your candid feedback and kind words. Thank you for supporting my journey at MIT.

Kenneth Kaplan, thank you for pushing me to think broadly and go beyond, for your kindness and words of wisdom.

Dr. Michael Tang, other leadership and staff at The Dimock Center, Lynn Community Health Center, East Boston Neighborhood Center, Uphams' Corner Health Center, and C3, thank you for your time and patience, for sharing a piece of your lives. Thank you for the work you do for those in need.

Andy MacInnis, Melissa Parrillo, my classmates at IDM, thank you for making what IDM really is, for the beautiful souls you all are.

Sehj, Shahed, Jaishree, Jelly, thank you for holding me when the chips were down, for being

there.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

11 Chapter 1 - Behavioral Health Integration: Past & Present

20 Chapter 2

-27 Chapter 3

-43 Chapter 4

-56 Chapter 5

-68 Chapter 6

-A Conceptual Understanding of Integration in Health care

o

3 Principles of Integration in Health careA Design-Based Framework for Behavioral Health Integration

o

5 Standard Models and Frameworkso

11 Design Elements for Behavioral Health IntegrationField Studies of Behavioral Health Integration

o

4 Community Health Centers in MassachusettsAn Outcomes-Based Framework for Behavioral Health Integration

o

4 Objectives of Behavioral Health Integrationo

5 Process Metrics for evaluating Behavioral Health IntegrationConclusions, Recommendations & Opportunities for Future Research

o

13 Key insightso

10 Recommendations0 5 Recommendations for future research

Figures

25 Figure 1: Relationship between patient needs and level of integration

Tables

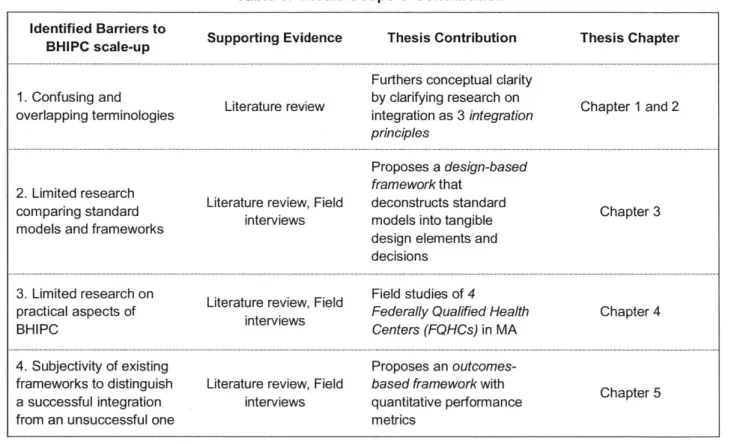

19 Table 1: Thesis Scope and Contribution

41 Table 2: Mapping Design Elements across Standard Models & Frameworks to

Integration Domains

42 Table 3: Design-Based Framework for Behavioral Health Integration in Primary

Care

54 Table 4: Using Design-Based Framework to study four FQHCs

67 Table 5: Outcomes-Based Framework for Behavioral Health Integration in Primary

Care

Appendixes

80 Appendix A: Semistructured Interview Guide

81 Appendix B: Sample Consent Form

Acronyms

ACO - Accountable Care Organization

AHRQ - The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality BH - Behavioral Health

BHI - Behavioral Health Integration

BHIPC - Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care C3 - Community Care Cooperative

CBHO - Chief Behavioral Health Officer

CCM - Collaborative Care Management Model CM - Care Managers

CMQ - Chief Medical Officer

EMR - Electronic Medical Record

FQHC - Federally Qualified Health Center

HRSA - Health Resources and Services Administration MH - Medical Health

PCBH - Primary Care Behavioral Health Model PCP - Primary Care Physician

SAMHSA - The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration SDOH - Social Determinants of Health

SMI - Serious Mental Illness

CHAPTER 1: BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTEGRATION: PAST AND

PRESENT

1

Definitions

Behavioral Health (BH), as defined by The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), refers to "mental health and substance abuse conditions, health behaviors (including their contribution to chronic medical illnesses), life stressors and crises, stress-related physical symptoms, and ineffective patterns of health care utilization" (Peek, 2013). In this thesis, I use this broad definition of behavioral health that doesn't limit the term to mental health and substance abuse disorders. Behavioral health could refer to other lifestyle behaviors that impact a person's health status as well.

Behavioral Health Integration (BHI), as defined by the AHRQ, is the care that results from a practice team of primary care and behavioral health clinicians, working together with patients and families, using a systematic and cost-effective approach to provide patient-centered care for a defined population" (Peek, 2013).

Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care (BHIPC), as used in this thesis, specifically refers to behavioral health integration that takes place in a primary care clinic, when specialty behavioral health services are introduced into the existing primary care set up, as opposed to the other way around.

2 Introduction

Historically, the US healthcare system, much like health care systems in the rest of the world, has treated the mind separate from the body. The practice of partitioning mental and physical disorders, as illnesses that are separate and distinct from each other, is reflected in the way the behavioral health sector is segregated from the general medical sector. Over the years, this approach has been institutionalized through separate behavioral and medical health facilities, separate payment systems, separate regulations and policies, separate training institutions, separate clinicians, and

separate cultures. The biggest impact of a segregated health care system has been felt by those with comorbid 'bio-psycho-social' needs. These are individuals who have not only physical disabilities such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disorder etc. but also accompanying mental health diagnoses such as depression or anxiety, or other serious mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

In this chapter, I review the de-facto segregated behavioral and medical health care delivery system in the US, including its performance in meeting the needs of persons with behavioral health and medical comorbidities. I explore the potential of a more integrated health care system and the available evidence of its benefits. I also provide an overview of the efforts to integrate behavioral and medical health care and discuss the challenges that have made that goal harder to achieve. Finally, given this background, I describe the scope of this thesis and its potential contribution towards an improved health care system.

The following research questions form the basis for this chapter's review:

1. How are people with comorbid behavioral and medical needs currently seeking care, and

what does that experience and care delivery process look like?

2. What is the impact of the separation of the behavioral and medical health care system on health care costs and outcomes?

3. What are proven benefits of integrating behavioral and medical health care services?

4. What are some of the big challenges in realizing the full potential of an integrated health care system? How might research help in solving some of those challenges?

3 Drivers of Change for Behavioral Health Integration

Key Question 1: How are people with comorbid behavioral and medical needs currently seeking

care, and what does that experience and care delivery process look like?

Behavioral Health disorders affect a large segment of the US population. About one in five adults experience a mental disorder in any given year (National Institute of Mental Health, 2019); about one in ten have a substance use disorder (Milbank Memorial Fund, 2016). These percentages more than double for the Medicaid population, in which more than half of the beneficiaries have a mental health diagnosis (Nardone et al, 2014). Depression is one of the leading causes of death in the US,

and it is estimated that half of all Americans develop a behavioral health condition during their lifetime. Of all Americans with a behavioral health condition, only about 40% are able to access treatment in a given year (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). Even for those who are able to access care, the experience generally leaves much to be desired, as detailed below.

Inadequate Behavioral Health Care Sector

Behavioral health care services in the US are typically designed to be delivered through a parallel delivery system that is separate from the general medical care delivery system. Over 95% of all behavioral health clinicians provide their services in standalone inpatient and outpatient behavioral health specialty clinics (R. Kathol et al., 2015). These clinicians are members of separate provider networks that are often not connected to the larger medical provider networks. Separate payers reimburse and support these BH services. At a system level, treatment outcomes and costs for behavioral health are calculated and recorded separately from those of medical care (R. Kathol et al., 2015). There is a separate federal department, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), within the US Department of Health and Human Services, that aims to improve health access and outcomes of the behavioral health care system. It was hoped that such separation would lead to focused delivery of behavioral health services to those who need it the most (R. Kathol et al., 2015).

However, the behavioral health care system, in its current design, has fallen short of that expectation. About 80% of people with behavioral health disorders, including those with serious mental illness, prefer to visit the medical sector for their behavioral health needs (R. Kathol et al.,

2015). For certain segments of the population-the elderly, racial minorities, rural, and lower

socioeconomic populations-this percentage is much higher (Strosahl, 1994). For the 20% of people visiting specialty behavioral health clinics to seek care, there is usually a long delay of more than six weeks to get access to a behavioral health clinician (R. Kathol et al., 2015).

Apart from the delays in scheduling the initial appointment with a behavioral health clinician, there are other plausible reasons for why people prefer to seek care for their behavioral health needs outside specialty behavioral health settings. First, there is still a prevailing stigma associated with behavioral health treatment, especially severe mental illness, which might discourage people to go to a behavioral health clinic (Milbank Memorial Fund, 2016). Second, the fact that behavioral health conditions are usually first diagnosed in a primary care setting might indicate a high prevalence of

comorbid physical conditions in patients with behavioral health disorders (MACPAC, 2016). The behavioral health sector is not designed to treat these physical comorbidities and tends to refer people outside for their physical health needs (R. Kathol et al., 2015).

Inadequate Medical Health Care Sector

Given that the majority of people with behavioral health conditions are not being treated by the behavioral health sector, how is the medical sector meeting the needs of the 80% of people with behavioral health conditions who knock on its doors? The primary care system has been described as the de facto behavioral health system in the US, however the quality of this care has been limited (Vogel et al., 2017). As mentioned before, 95% of behavioral health specialists practice in the behavioral health sector, and are therefore not accessible to the primary care system. The primary care physicians who try to fill this gap (i) are insufficient in number (ii) are already overburdened (iii) are inadequately trained to diagnose and treat behavioral health conditions, and (iii) tend to rely on pharmacologic strategies (MACPAC, 2016; Vogel et al., 2017). As a result, only about a third of the patients seen in the medical sector for behavioral health disorders receive any kind of treatment for their condition (R. Kathol et al., 2015; R. G. Kathol, Butler, McAlpine, & Kane, 2010). Furthermore, of this third, only about 10% end up receiving evidence-based treatment (R. Kathol et al., 2015). The inability of either sector to adequately meet the full health needs of individuals with behavioral and physical health comorbidities means, in the best case, a constant shuffling between the two systems of care for such individuals. Most people, however, tend to fall out of the health care system completely, and patient "no show" rates are often high (R. G. Kathol et al., 2010).

Inadequate Overlap Between Behavioral and Medical Health Care Sectors

The crossover and sharing of personnel and resources between the medical and behavioral health care sectors seems to be difficult and uncommon. This has further added to the suboptimal experience of people with comorbid behavioral and medical health disorders. One of the main reasons for the poor health care delivery at the intersection of behavioral and medical health sectors is the segregated payment or reimbursement systems that have been established by the different health plans/payers of medical and behavioral health care (R. Kathol et al., 2015).

Separate payers and therefore budgets for medical and behavioral health care lead to a competitive environment where each system tries to ensure that their budgets are not being misappropriated to services in the other sector. These boundaries are further strengthened by the fact that the budget

for behavioral health constitutes only about 7% of the total health care spend (R. Kathol et al.,

2015). The best way to avoid misappropriation is keeping the two systems as far away from one

another as possible.

Key Question 2: What is the impact of the separation of the behavioral and medical health care

sectors on health care costs and outcomes?

High Impact of Behavioral Health on Outcomes and Costs

Care for people with behavioral health condition tends to be more complicated than for those without. Often, people with behavioral health disorders have comorbid medical health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, or diabetes (AHRQ, 2008). They also have high rates of unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, physical inactivity, or poor diet. (Milbank Memorial Fund, 2016). The presence of a comorbid behavioral health condition further worsens a chronic medical condition. For example, cardiac patients who are depressed are more likely to die; and depressed, diabetic patients have worse glycemic control and higher complication rates than those who are not depressed (Jackson et al, 2004).

The complexities of behavioral illnesses increase healthcare utilization for patients with behavioral health conditions (Strosahl, 1994). It has been observed that patients with comorbid behavioral health conditions have longer average length of stays of hospital and higher readmission rates (R. Kathol et al., 2015). The risk to get readmitted is particularly high if behavioral health disorders remain untreated (Henderson & Miller, 2014).

With increased health care utilization rates, it is no surprise that health care costs for patients with chronic medical and comorbid behavioral health conditions are 2-3 times higher than those who don't have comorbid behavioral health conditions (Melek et al., 2018). Most of this increased cost is for medical rather than behavioral health services (Melek et al., 2018). Again, patients with untreated behavioral health conditions further drive up costs because they utilize care 3 times as much as those who receive treatment (Henderson & Miller, 2014). It is argued that co-managing or integrating behavioral and medical health services has the potential to reduce these costs drastically (Melek et al., 2018).

4 The Promise of Behavioral Health Integration

Key Question 3: What are the proven benefits of integrating behavioral and medical health care

services?

Much of the innovative efforts in behavioral health integration have been in primary care. This is not surprising since primary care is usually the first point of diagnosis for behavioral health conditions. People are much more likely to visit their primary care physician than a mental health clinician each year (AHRQ, 2008). Many people with a behavioral health illness have a comorbid physical ailment as well, as has been mentioned before. Primary care is also expected to meet the whole-person needs of individuals (World Health Organization Alma Ata Declaration, 1978; Starfield, 1994). Behavioral health and primary care integration can occur in two directions: either specialty behavioral health services are introduced into primary care or primary care is introduced into specialty behavioral health settings (AHRQ, 2008). In this thesis, I discuss the first type of integration in detail and refer to it as behavioral health integration in primary care (BHIPC). The second type of integration, which is outside the scope of this thesis, is generally aimed at people with more serious mental illnesses (SMI), who mostly access specialty behavioral health settings but do not have their general medical needs adequately addressed.

A number of randomized control trials (RCTs), systematic reviews (SRs), and technology

assessments (TAs) have evaluated the impact of integrating behavioral and medical health services in primary care. This section briefly reviews some of those evaluations and discusses the available evidence for successful behavioral health integrations.

Improved Health Outcomes

In 2015, The Institute For Clinical And Economic Review (ICER) reviewed 94 RCTs covering more than 25,000 patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders and concluded that integrating behavioral and medical health services improves depression and anxiety outcomes or remission scores in the short (0-6months), medium (7-12 months), and long-term (13-24 months) in comparison to usual care (Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, 2015). Almost all of the 94 studies employed some version of the Collaborative Care Model (CCM) (discussed in chapter 3). Furthermore, ICER also studied the impact of integrated care on patients with comorbid depression/anxiety and a chronic medical illness (such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease)

and found evidence of improved medical outcomes there as well. The biggest RCT to date that observed improved health care outcomes in older people with comorbid depression and diabetes due to integration (CCM) is the IMPACT trial which was a multisite RCT that ran from 1998-2003 (Williams et al, 2004). Another RCT called TEAMcare that was conducted in 2007-09 saw statistically significant healthcare improvements with the CCM in patients with depression and coronary heart disease (Katon et al., 2010).

Evidence for improvements in health care outcomes for other physical comorbidities (other than diabetes and cardiovascular disease) due to integrated care is limited (Milbank Memorial Fund,

2016).

Intermountain Healthcare, a fully integrated system, conducted a retrospective, longitudinal study from 2010-2013 and found that integration reduced ER visits by 23% (Melek et al., 2018; Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016).

Reduced Health Care Costs

The IMPACT trial demonstrated that the CCM led to lower health care costs of about 10% over a four year period (Melek et al., 2018; Vogel et al., 2017). Other studies (such as the Intermountain Health study) have also found a 5-10% savings in total cost of care over a period of two to four years (Melek et al., 2018).

Increased Patient Satisfaction

According to the ICER review, integration did increase overall patient satisfaction with the care provided (institute for Clinical and Economic Review, 2015).

5 Thesis Objective

Key Question 4: What have been some of the challenges in realizing the full potential of an

integrated health care system?

Recent health care policy reforms including the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) movement and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA, 2010) have pushed the field of behavioral health integration forward and brought attention to the delivery of behavioral health

services within primary care settings (Vogel et al., 2017). The ACA expanded behavioral health coverage and removed copays for preventive behavioral health screenings. The Accountable Care Organization (ACO) Model of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation offers shared savings to organizations that provide coordinated care. This has further encouraged providers to pilot innovate models of behavioral health integration.

Although behavioral health integration in primary care is spreading rapidly, there are barriers that still exist, especially for groups who are trying to implement a model of integration based on existing knowledge and evidence. Future research work can play an important role in accelerating the adoption of behavioral health integration:

LI Efforts have been made by the US federal agencies, AHRQ and SAMHSA to define standard definitions and frameworks for behavioral health integration. However, confusion around the concepts and underlying principles of integrated care still prevails;

there is a need for research to further simplify the multitude of models and concepts that exist

LI Health systems struggle to evaluate their level of integration. The SAMHSA levels of

integration are difficult to quantify and evaluate against; there is a need to develop

measures to help health systems better determine their level of integration and the road ahead

L) Health systems struggle to understand the relationship between various integration design decisions and final outcomes; there is a need to develop a framework that

makes it easier to understand the value of a specific design decision.

In this thesis, I aim to:

LI Synthesize research on behavioral health integration in a way that furthers understanding of the origins, rationale, and models of behavioral health integration L Break down the abstract concept of behavioral health integration in primary care into a

set of tangible design elements and decisions that providers and policymakers can use to develop a behavioral health integration program

LI Provide a window into the day-to-day operations of community health centers and share how primary care centers operationalize some of the common integration strategies

LI Propose an outcomes-based framework that helps organizations implementing behavioral health integration to better determine (i) their current status of integration, (ii) steps they might take to enhance that integration, (iii) the impact of the different design elements and strategies on integration outcomes.

The table below summarizes the thesis scope and contributions:

Table 1: Thesis Scope & Contribution

Identified Barriers to Supporting Evidence Thesis Contribution Thesis Chapter BHIPC scale-up

Furthers conceptual clarity

1. Confusing and. Literature review by clarifying research on

overlapping terminologies integration as 3 integration Chapter 1 and 2

principles

Proposes a design-based

2. Limited research framework that

comparing standard Literature review, Field deconstructs standard Chapter 3

models and frameworks interviews models into tangible

design elements and decisions

3. Limited research on Literature review, Field Field studies of 4

practical aspects of e. Federally Qualified Health Chapter 4

BHIPC inerviews Centers (FQHCs) in MA

4. Subjectivity of existing Proposes an

outcomes-frameworks to distinguish Literature review, Field based framework with

Chapter 5

a successful integration interviews quantitative performance

CHAPTER 2: A CONCEPTUAL UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATION IN

HEALTH CARE

1

Definitions

Integration in Health Care or Integrated Care refers to a coherent set of methods and models at the funding, administrative, organizational, service delivery and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment, and collaboration within and between the cure (medical) and care (social or human services) sectors (D. L. Kodner & Spreeuwenberg, 2016).

2 Introduction

Although the movement towards behavioral health integration has only gained momentum in the last decade or so, the idea of integration in health care or integrated care has existed since the 1970s (D. L. Kodner & Spreeuwenberg, 2016). Integration in health care has been used as an umbrella term for multi-pronged efforts aimed to improve health care delivery for special patient groups such as the elderly, people with chronic conditions, and other individuals with complex needs. These high-need, or complex-need, or continuous-need patients utilize health care to a greater extent than an average-need patient, often by accessing different parts of the health care system. Improving care delivery and experience for high-need patients has been recognized as a priority in the US, and several examples of integrated care models have emerged as a result. These models can lend insights into how integration is typically achieved, and how integrated care models might differ from one another.

In this chapter, I review the larger landscape of integration in healthcare, which is not limited to behavioral health care integration, and in fact predates it. I study and discuss related research that has attempted to bring some structure to this larger idea of integration in health care. I synthesize my findings and clarify the concept of integration in health care as three underlying principles. The objective here is to not only increase conceptual clarity of integration in health care but also provide

the foundation to more easily conceptualize the design of behavioral health integration models, which I will discuss in the next chapter.

The following research questions form the basis for this chapter's review:

5. What are the origins of and motivations for integration in health care?

6. What are some generalizable insights from the wider field of integration in health care that

might benefit practitioners of behavioral health integration?

3 Integration in Health Care

Key Question 5: What are the origins and motivations of integration in healthcare?

A Fragmented Health Care Delivery System

Health care systems are highly complex and interdependent enterprises. The complexity and the need to manage dependencies in health care arise from the presence of a high degree of differentiation. Functional differentiation in health care can be seen along the whole continuum of care, for example, separate organizations or groups responsible for disease prevention and promotion, treatment, long-term care, and social care. Functional differentiation often leads to structural differentiation, which refers to the different ways in which services are organized and managed along the continuum. Health care organizations and groups are also often driven by different motivations and objectives, resulting in cultural differentiation (Axelsson & Axelsson,

2006). In the previous chapter, I illustrated the differentiations between the behavioral and medical

health care sectors.

While differentiation is inevitable in a health care system, given the myriad patient needs that exist, differentiation without some overall coherence or integration of effort leads to fragmentation of responsibilities. Fragmentation in health care has been associated with several efficiency and quality problems such as service delays, duplication, inconsistencies, and high patient no-show rates (Axelsson & Axelsson, 2006; D. L. Kodner & Spreeuwenberg, 2016; Mac Adam, 2008). Furthermore, complex-need individuals are the most adversely affected by fragmentation in health care (D. L. Kodner & Spreeuwenberg, 2016). These individuals include the frail elderly, individuals with multiple chronic conditions, and individuals with comorbid behavioral, medical, and social needs (Hayes et al., 2016).

Integrated Care and Disease Management

The prevalence of fragmentation in health care and the associated inefficiencies and inadequacies have driven policymakers and practitioners to develop innovative health care delivery models. Integrated care and disease management are two parallel approaches that have emerged towards improving care for those with complex and concurrent needs (Nolte & McKee, 2008).

There is considerable overlap between the concepts of integrated care and disease management. While they are similar in their objective to improve care for those with complex needs and in their approach of reducing fragmentation by linking services across the continuum of care, they differ in the systems they aim to integrate. Integrated care tends to frequently link the health care and social sectors whereas disease management is typically limited to coordinating services within the health care sector to manage a specific (single) health condition (Nolte & McKee, 2008).

Disease management initiatives in the US began in the 1980s, initially as educational programs run

by pharmaceutical companies with the aim to promote medication adherence and behavior change

among patients with a chronic illness such as diabetes, asthma, or coronary heart disease. In the 1990's, disease management strategies were adopted more widely after cost savings were realized for chronic patients. Disease management programs evolved to be either 'on-site', wherein they were provided by primary care providers, or 'off-site' or 'carved-out', where they were managed by for-profit vendors for a specific process of care (Nolte & McKee, 2008). More recently, there has been a trend to develop a broader, more population-focused approach to disease management. These second generation disease management programs have aimed to address the multiple needs of complex-need patients and have blurred the boundary between integrated care and disease management (Nolte & McKee, 2008).

Two Perspectives on Integrated Care

Two predominant perspectives exist on the objectives that integrated care is supposed to achieve. One perspective stems from the traditional health care or managed care lens, according to which integrated care is supposed to achieve improved health care efficiency and quality. The World Health Organization's (WHO) definition on integrated care reflects this perspective. According to WHO, integrated care brings together inputs, delivery, management and organization of services related to diagnosis, treatment, care, rehabilitation and health promotion in order to improve access, quality, user satisfaction and efficiency (Gr6ne & Garcia-Barbero, 2001). The other perspective is more patient-centered in its view and posits that the primary objective of integrated care is meeting

the 'whole' needs of patients, that health care and social sector should not be separate. According to Leutz, integrated care is about connecting the health care system (acute, primary medical, and skilled services) with other human service systems (e.g. long-term care, education, and vocational and housing services) (Leutz, 1999).

4 PRINCIPLES OF INTEGRATION IN HEALTH CARE

Key Question 6: What are some generalizable insights from the wider field of integration in

health care that might benefit practitioners of behavioral health integration?

Several researchers have examined integration efforts in health care in the US for the purpose of classifying the different forms of integration that exist, understanding the factors that influence integration, and identifying the different strategies that are employed to achieve integration. One of the pioneering works in this field was that of Walter Leutz, who in 1999 described the different configurations in which integration can happen. Following Leutz, Kodner and Spreeuwenberg suggested a continuum of strategies to foster integrated care in 2002. In 2006, Axelsson and Axelson published their review of integration in health care, specifically focusing on inter-organizational integration. Ellen Nolte and Martin Mckee (2008) also contributed towards clarifying the concept of integration in health care.

In this section, I synthesize some of the insights from these foundational works into three main principles of integrated care. These principles represent the first set of decisions that practitioners typically face when developing a plan to integrate care in their settings.

(a) The extent of integration should be aligned with the risk and complexity of targeted patients' needs

One of the first decisions that systems integrating health care services have to make is to choose the extent of integration. According to Leutz, "You can integrate all of the services for some of the people, some of the services for all of the people, but not all of the services for all of the people." In his work, Leutz suggests that there are multiple services that could be integrated by a health care setting, and that they could be integrated to varying degrees or levels (Leutz, 1999). One criterion to consider while choosing the services and level to integrate is what the patients need. According to Leutz, there are six dimensions of need on the basis of

which patients can be stratified or placed along the 'needs'axis. These dimensions include the stability and severity of patients' conditions, duration (short, medium, long, end-of-life), urgency, complexity, and the patients' or caregivers' capacity for self-direction (Leutz, 1999). This stratification of patients conveys the idea that not everybody needs full integrated services, and that the greater the needs, the greater are the possible benefits of integration, and the greater

should be the level of integration.

(b) Integrated Care efforts can be arranged along an integration continuum

The second dilemma that is faced while integrating health care services is how to integrate or choosing the right configuration to integrate. Continuing with the idea that the degree of integration should be based on patients' needs, Leutz describes three levels of integration to suggest three arrangements in which integration can happen between segregated systems: linkage, coordination, and full integration (Leutz, 1999).

o Linkage - Patients with mild-to-moderate or stable conditions can be served sufficiently by

simple linkages of different systems. This form of integration is minimal and does not require any special system arrangements, although, it does require each provider to be aware of the capabilities of other providers in terms of health and social needs, financing responsibilities, and eligibility criteria so that effective referrals can be made (Nolte & McKee,

2008).

o Coordination - Patients with moderate level of needs can also be served mainly through

the existing systems, but require additional inter-organizational arrangements (such as established workflows) to facilitate communication, coordination, and continuity.

o Integration - Patients with long-term, severe, or unstable conditions require transformative

systemic changes and formation of new entities that integrate responsibilities, financing, and resources in a single entity in order to support patients through the entire continuum of care

(D. Kodner, 2013).

The first and second principles highlight the relationship between the level of patients' needs and the level of optimal integration. This relationship is illustrated in figure 1 below.

++severe +++ s... ...- ...- ....-.- ... Full Integration needs ++ mo-derate Coordination needs + mild-moderate -- Linkage needs integration continuum

(c) Different health care domains can be integrated-Clinical, Operational,

Financial, Cultural, and Organizational

Another consideration that is encountered while integrating health care services is which elements to integrate. Several researchers have examined this question and more or less suggest similar domains (sometimes with different names) for integration. Following is a list of possible integration domains synthesized from various sources (each integration domain mentions the sources that it was referenced from).

U Clinical Integration

This refers to integration at the point of care level among different providers who come together for the whole health needs of patients and develop a uniform code for patient interaction, screening, treatment, and maintenance processes (Axelsson & Axelsson,

2006; D. L. Kodner, 2006; Leutz, 1999; Nolte & McKee, 2008; Valentijn, Schepman,

Opheij, & Bruijnzeels, 2013).

Ll Operational Integration

This refers to integration at the staff, service, and process levels. This includes how staff are trained and work together as a team to provide various patient services from first access to coordination of care post discharge. This also includes functional systems that

work behind the scenes to make integration possible such as information exchange and patient management systems (Axelsson & Axelsson, 2006; D. L. Kodner, 2006; Leutz,

1999; Nolte & McKee, 2008; Valentijn et al., 2013).

L3 Financial Integration

This refers to the integration of funding systems. According to Kodner and Spreeuwenberg, all aspects of integration are strongly influenced by the way funding is structured, and allocated between the health and social care services. This is why the form of integrated care often follows funding mechanisms (D. L. Kodner, 2006; Leutz,

1999; Pim P. Valentijn, Schepman, Opheij, & Bruijnzeels, 2013).

Li Cultural Integration

Surprisingly, none of the research works I studied except that of Pim Valentijn's mention cultural integration as a possible integration domain. Cultural integration refers to developing a shared mission, vision, values, and culture among the organizations and

professionals engaged in the integration process (Valentijn et al., 2013). Li Organizational Integration

This refers to integration between organizations at the same level of care such as different primary care practices (horizontal integration) or between organizations at different levels of care such as health services, social services, and vocational services (vertical integration) to coordinate care across settings. Organizations could enter into different formal partnerships based on the degree of integration-from specific contracts to full mergers (Axelsson & Axelsson, 2006; D. L. Kodner, 2006; D. L. Kodner & Spreeuwenberg, 2016; Nolte & McKee, 2008; Valentijn et al., 2013).

CHAPTER 3: A DESIGN-BASED FRAMEFORK FOR BEHAVIORAL

HEALTH INTEGRATION IN PRIMARY CARE

1

Definitions

Standard Models, as defined in this thesis, refer to models that are recognized as foundational models for behavioral health integration in literature, and have inspired a number of adaptations. In this thesis, the standard models that are studied are the Collaborative Care Management Model

(CCM), and the Primary Care Behavioral Health Model (PCBH).

Standard Frameworks, as defined in this thesis, refer to the Integration Frameworks developed by

US federal agencies, AHRQ and SAMHSA-HRSA, in order to highlight key elements of BHIPC and

differentiate among various adaptations of the standard models.

Design Elements, as defined in this thesis, refer to the different functional and structural elements that make up a BHIPC model or program.

Design Specifications, as defined in this thesis, refer to the practical options that might be adopted to operationalize a particular design element.

Design Decisions, as defined in this thesis, refer to the decisions that primary care practitioners of face when developing a BHIPC program

2 Introduction

Hundreds of Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care (BHIPC) programs have been implemented in primary care clinics across the US, and many other BHIPC programs are in the process of getting implemented. These BHIPC implementations may be based in different settings (e.g. private or public, community health center or hospital), be adapted from different theoretical

models (e.g. Collaborative Care Management Model or Primary Care Behavioral Health Model), be targeted towards different patient population needs (e.g. chronic care patients with low risk behavioral health conditions, patients with active substance abuse problems, or patients with serious mental illness), or be differently funded (e.g. fee-for-service, value-based payment, or grants).

However, apart from these surface differences that allow us to categorize these programs, how else do these BHIPC programs differ from one another? For practitioners or groups who want to start a BHIPC program, what are some strategies they might take while designing their BHIPC programs? What are integration elements that they must include? There is limited research on classifying the underlying components of BHIPC programs and models, and uncertainty remains on how to design BHIPC programs. More work is also needed to understand how BHIPC is implemented and practiced (Martin, White, Hodgson, Lamson, & Irons, 2014).

In this chapter, I deconstruct some of the standard BHIPC models and frameworks to synthesize the underlying characteristics into a set of design elements. I use the integration domains defined in chapter 2-clinical, operational, financial, cultural, and organizational-as broad buckets within which these design elements are categorized. I also review related research that has examined successful BHIPC implementations in the US in order to understand how some of the standard design elements have been adapted and operationalized in real-world settings. I codify these adaptations as design decisions that practitioners have taken in order to realize behavioral health

integration in their settings.

The purpose of this chapter is to break down the abstract concept of behavioral health integration in primary care into set of tangible design elements and decisions that providers and policymakers can use to design a behavioral health integration program.

The following research questions form the basis for this chapter's literature review:

7. What standard models and frameworks have informed BHIPC efforts across the United

States? How did these models originate?

8. What are the key characteristics of the standard BHIPC models and frameworks, and what

do they aim to achieve?

10. What are the most critical characteristics that have been found to be associated with positive

outcomes?

2 Design Elements derived from Standard Models and Frameworks

Key Question 7: What standard models and frameworks have informed BHIPC efforts across the

United States? How did these models originate?

By a simplified definition, behavioral health integration in primary care involves linking primary care

providers with behavioral health care providers (AHRQ, 2008). However, the nature and strength of these linkages as well as the strategies employed to link to other aspects of the care process might vary significantly. BHIPC encompasses a broad continuum of models from minimal to full integration (SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions, 2013). Within this continuum of diverse BHIPC models, research has mostly focused on two models: the Collaborative Care Management Model (CCM) and the Primary Care Behavioral Health Model (PCBH) (Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, 2015; Vogel et al., 2017).

Some of the pioneering work on developing and studying integrated care models in primary care was led by Wayne Katon and Edward Wagner (independently) in the early 1990s. While Katon et al ran the first randomized control trials for the treatment of anxiety and depression in primary care that would eventually become the CCM, Wagner et al worked to develop the broader principles of the Chronic Care Model for integrating care for all chronically ill patients (AIMS Center; Wagner et al., 1996). CCM in that sense is a specific evidence-based approach that operationalizes the principles of the Chronic Care Model for individuals with comorbid behavioral health and physical health conditions (APA/APM, 2016; Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, 2015). Under the

CCM, a team composed of a primary care physician (PCP), a care manager who is a mid-level

provider, and a consulting psychiatrist provide brief psychoeducation or counseling services for a defined patient population with specific chronic mental health needs (e.g. depression).

The PCBH model, derived from the work of Kirk Strosahl, became popular as another approach to integrate primary care and behavioral health in the 1990s (Robinson & Reuter, 2007). PCBH shares several elements of the CCM. The key difference is that behavioral health clinicians (usually psychologists or clinical social workers) are fully embedded into the primary care team to improve

the overall behavioral health (behavioral factors for all mental and physical conditions) for the whole patient population (Hunter & Goodie, 2010; Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, 2015; Vogel et al., 2017). The design of these models (both CCM and PCBH) is discussed in more detail in the

next section.

Terminology in the emerging field of behavioral health integration has been varied and confusing. This has proved to be a barrier in comparing different behavioral health integration models and standardizing successful ones. Recognizing these challenges, the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed a Lexicon to define key terms and an Integration Framework to recommend key elements of behavioral health integration. Other federal agencies, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) supplemented AHRQ's work with another conceptual framework to help organizations evaluate their own degree of integration. These frameworks are also discussed in more detail in the following section.

Key Question 8: What are the key design characteristics of the standard BHIPC models, and what

do they aim to achieve?

1. Wagner Chronic Care Model (WCCM)

Several BHIPC models that have been piloted and studied through controlled trials in the US have cited the Wagner Chronic Care Model (AHRQ, 2008; Institute for Clinical and Economic Review,

2015). This heuristic model for improving care for patients with chronic illnesses was developed by

Edward Wagner and his peers at Seattle's Group Health Cooperative (acquired by Kaiser Permanente in 2015) in 1996 (Wagner et al., 1996).

Reviewing available evidence at the time, Wagner et al argued that usual medical care fails to meet the educational, behavioral, and psychosocial needs of chronically ill patients. These needs are essential for patients and their families to appropriately self-manage their illness and its treatment. They further drew attention to the difficulties encountered by medical care providers in following established guidelines for chronic illnesses treatment. Wagner et al hypothesized that these deficiencies in usual medical care contribute to suboptimal outcomes for chronically ill patients (Wagner et al., 1996). Some of the reasons suggested for these deficiencies are summarized below. These inadequacies motivated Wagner et al to examine successful innovative approaches

to chronic illness care and recommend guidelines for reorganizing it (Wagner et al., 1996). The guidelines are widely referred to as the Wagner Chronic Care Model.

Reasons mentioned by Wagner et alfor the failure of routine care to meet the demands of patients with chronic illnesses:

1. Culture and Structure of Medical Practice: Medical settings including primary care are

traditionally organized to respond to the acute and urgent needs of patients that puts the focus of care on diagnosis, curative, and symptom-relieving treatments. Physicians end up responding mostly to acute emergencies, which leaves little time for addressing the less-urgent, self-management, and longer-term needs of chronic patients.

2. Inadequate Provider Training: Chronic illness treatment requires some degree of planning, but due to the emphasis on urgent care, providers are not adequately trained on available standards in the medical care of patients with chronic illnesses.

3. Inadequate Operational Structures: In the acute illness care environment, it is not the

norm to collect information about patients' ability to function, their understanding of the illness, and their ability to self-manage. Non-physician staff are busy with managing access and patient flow, and there is no delegation of patient education, counseling, and follow-up responsibilities. Patient medical records are also not designed to facilitate chronic care management.

4. Lack of Financial Incentives: Traditionally, provider evaluation and payment structures under fee-for-service have not rewarded providers for taking out the time to conduct assessments, counseling, telephone follow-ups, or other self-management activities for patients.

Design Elements derived from the Wagner Chronic Care Model

Wagner et al identified significant similarities among successful programs aiming to improve care for chronic illness patients and classified the common strategies as guidelines for re-organizing care:

A. Developing Evidence-Based Planned Care

According to Wagner et al high-quality chronic illness care should be planned and homogenized for a patient population instead of being reactionary and individualized to each patient-aspects that are encouraged by the acute care orientation of traditional medical care (Wagner et al., 1996). Planned care is defined as an explicit statement of what needs to be done for patients, at what intervals, and by whom. Planned care is typically realized in successful programs through defined evidence-based protocols or guidelines. Wagner et al highlight that the shift to evidence-based, planned care leads to improvement in clinical outcomes and can be facilitated by organized efforts such as information systems and provider trainings.

Synthesized Idea: Planned care based on proven treatment pathways leads to improvement in outcomes.

B. Redesigning Clinical Practice

One strategy to meet the ongoing multiple needs of chronically ill patients is to enhance the clinical team. Approaches to reorganization of the clinical team have varied along a continuum from enhancing usual primary care, adding specialized providers (such as medical specialists or care managers) to primary care teams, to entirely separate specialized care programs. According to Wagner et al adding specialized providers to the clinical team may not only bring new knowledge to the team, but also enable regular assessments, follow-ups, and better patient engagement that are required for effective management of chronically ill patients. Team meetings (between the generalist and specialist providers) and continuing medical education are other suggested interventions for

enhancing primary care expertise.

Synthesized Idea: Primary care needs to be enhanced in order to meet the self-management and bio-psycho-social needs of chronic care patients.

C. Providing Patient Self-Management Support

Another feature shared by successful chronic illness programs is patient educational programs that train patients and family caregivers to self-manage their chronic illnesses. Wagner et al share evidence of self-management and behavioral change programs that have led to outcome improvements in diabetes, hypertension, and coronary heart disease.

Although, the exact method of patient empowerment (class, one-on-one counseling, or virtually) seems to be of lesser significance, goal-setting and sustained follow-up are a few program elements mentioned by Wager et al that have proven to be beneficial.

Synthesized Idea: Effective management of bio-psycho-social needs of chronically ill patients requires changes in lifestyle and development of self-management competencies.

D. Developing Information Systems

Wagner et al stress that without information about patients, their treatment progress, and outcomes, physicians are forced to be reactive, which leads to suboptimal care. One strategy to achieve this is to develop and use patient registries as monitoring tools.

Synthesized Idea: Information about patients' needs, treatment progress, and outcomes is essential to effective care.

II. Collaborative Care Management Model (CCM)

A model that operationalizes some of the above-mentioned principles of Wagner Chronic Care

Model for people with behavioral health disorders is the Collaborative Care Management Model

(CCM), first trialed by Wayne Katon in the 1990s. Over the last three decades, hundreds of

randomized controlled trials have established strong evidence for the CCM to deliver improved outcomes over usual medical care (APA/APM, 2016; Un~tzer, 2013). This success has been replicated in a variety of settings (private and public), for different patient populations (insured and uninsured), for different mental health conditions (depression, anxiety disorders, and more serious conditions such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia), and even with different financing mechanisms (fee-for-service and capitation) (Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, 2015; Milbank Memorial Fund, 2016; UnOtzer, 2013).

Design Elements derived from the Collaborative Care Management Model

Large-scale adaptations covering thousands of patients have identified four design elements to be core to the CCM. Not surprisingly, all four elements have been mentioned in the conceptual Wagner Chronic Care Model (see previous section). CCM adds more depth and specificity to these elements, having been informed by their real-world implementations in meeting the behavioral health needs of patients in primary care.

A. Team-Driven Care

In CCM, the clinical team is a multidisciplinary group of care delivery professionals-primary

care physicians (PCPs), nurses, care managers (CMs), and mental health specialists-who follow a planned-based care. Mental health specialists may include psychiatric nurse practitioner, social worker, licensed counselor, psychologist, or psychiatrist. This can be contrasted with other team structures mentioned in the Chronic Care Model practice team continuum vis-6-vis enhanced PCPs and separate specialty care programs. There are three main members in this multidisciplinary team: (a) the PCP (b) the CM, and (c) the consulting psychiatrist. While the PCP leads the overall patient treatment plan, the behavioral or medical health CM, who is usually a mid-level provider, is responsible for engaging patients in their care plan and linking the team to patients and to each other. The psychiatrist either provides regular consultation to CMs and PCPs or direct care to the patient (APA/APM,

2016).

B. Population-Focused Care

This element refers to the use of a patient registry to stratify and manage a defined population of patients. The registry is reviewed by the clinical team at regular intervals to monitor each patient's progress and prepare treatment plans accordingly. Treatment is systematically adjusted-stepped up or down-based on patient's response and severity levels. Stepped care enables effective use of limited specialty resources. Effective data collection and monitoring of a patient's condition, progress, and outcomes are essential components of population-based care. CM is typically responsible for gathering information about the patient through phone calls, text messages, emails or home visits. Maintenance of a patient registry also allows regular follow-ups with patients which results in better treatment adherence (APA/APM, 2016; UnLtzer, 2013).

C. Measurement-Based Care

Inspired by Chronic Care Model's principle of planned care based on structured patient assessments, measurement-based care (MBC) involves the use of systematic, disease-specific, patient-reported outcome measures (such as PHQ-9 for depression) to drive clinical decision-making (APA/APM, 2016).

D. Evidence-Based Care

Evidence-based care refers to the use of proven clinical treatments to achieve improved outcomes. This element advocates the idea of Chronic Care Model's planned care principle that is based on systematic research data. Treatment plans are standardized and follow a stepped-care approach that varies in intensity based on a patient's severity of needs. One example of evidence-based care is the use of psychotherapy for treating major depressive disorders, since psychotherapy has proven to be effective for depression remission for

60-70% of patients (APA/APM, 2016). Ongoing trainings of providers is a strategy to ensure

that the most updated therapies are used by the primary care team.

1ll. Primary Care Behavioral Health Model (PCBH)

Another model that is widely popular and that have been implemented in hundreds of primary care clinics in the US is the PCBH model, which was largely developed from the work of Kirk Strosahl in the 1990s.

Design Elements derived from the Primary Care Behavioral Health Model

PCBH falls on the more intensive end of the BHIPC continuum and further extends the design

principles of the CCM model.

A. Team-Based Care

In this model, behavioral health consultants (BHCs) and PCPs provide services side by side, ideally sharing the same physical space, with the goal of creating a team-based management care approach. BHCs are typically licensed BH providers-a psychologist, social worker, or counselor.

B. Population-Based Care

PCBH focuses on population management which is different from specialty mental health. Whereas, mental health tends to focus on specific behavioral health needs of a patient, providing extensive in-depth care, the PCBH model is designed to see a much higher percentage of the primary care population (Robinson & Reuter, 2007). The services provided by a BHC in the PCBH model are more comprehensive than specialty MH and cover a wider range of behavioral health problems-including chronic pain, headache, medical nonadherence, smoking cessation, weight management, and sleep disorders (Hunter & Goodie, 2010; Robinson & Reuter, 2007; Vogel et al., 2017).