8

iLIBRARIES)

raDigitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

DEWE\

working paper

department

of

economics

COMPARATIVE

ADVANTAGE

AND

THE

CROSS-SECTION

OF

BUSINESS

CYCLES

AartKraay JaunieVentura 98-09 June,1998

massachusetts

institute

of

technology

50

memorial

drive

Cambridge,

mass. 02139

WORKING

PAPER

DEPARTMENT

OF

ECONOMICS

COMPARATIVE

ADVANTAGE

AND

THE

CROSS-SECTION

OF

BUSINESS

CYCLES

AartKraay JaumeVentura 98-09 June, 1998

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE

OF

TECHNOLOGY

50

MEMORIAL

DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE,

MASS. 02142

MASSACHUSETTSINSTITUTE

OFTECHNOLOGY

SEP

1 6 1998Comparative

Advantage

and

the

Cross-section

of

Business

Cycles

Aart

Kraay

Jaume

Ventura

The

World

Bank

M.I.T.May,

1998

Abstract: Business cycles areboth less volatile

and

more

synchronizedwith theworld cycle in rich countriesthan in poorones. Inthis paper,

we

developtwoalternative butnon-competing explanations forthese facts. Both explanations

proceed from the observation thatthelaw ofcomparative

advantage

causes

richand

poorcountriestospecialize inthe production ofdifferentcommodities. In particular, rich countriesspecialize in"high-tech"products

produced

byskilledworkerswhilepoorcountriesspecialize in "low-tech"products

produced

byunskilled workers. Cross-country differences inbusinesscyclesthen arise as a resultofasymmetries

among

the industries in whichdifferentcountries specialize.We

focuson

two such asymmetries.The

firstwe

labelthe "competition bias" hypothesis,and

isbased on

the ideathat cross-country differencesin production costsare

more

prevalent inhigh-tech industries, sheltering producers fromforeign competition

and

thereforemaking

them

large suppliers in the marketsfor theirproducts.The

second

asymmetry

we

label the"cyclical bias" hypothesis,

and

isbased on

the ideathat production costs inlow-tech industriesmight

be

more

sensitivetothe shocks that drivebusinesscycles.Commentsarewelcomeatakraay@worldbank.org(Kraay)andjaume@mit.edu (Ventura).Theviews

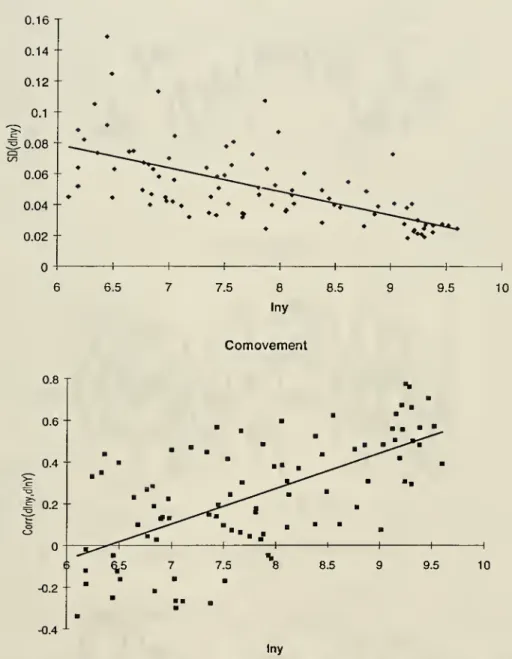

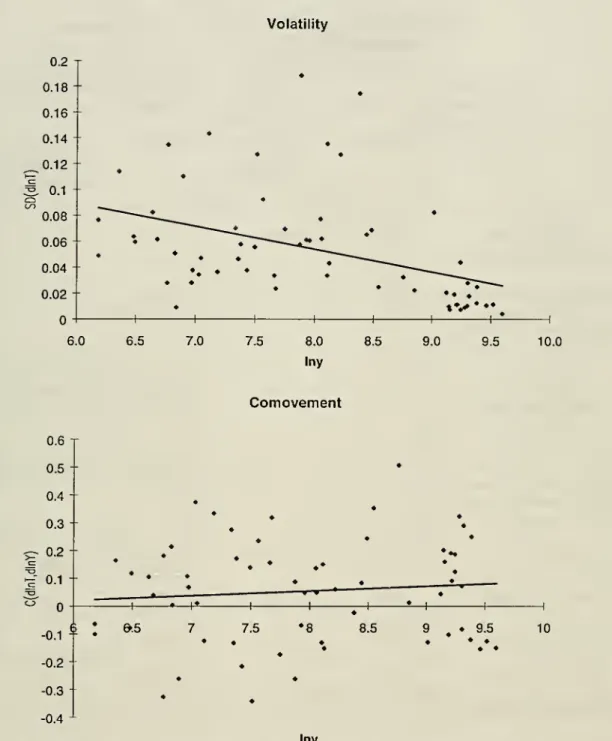

Businesscyclesare different in rich

and

poorcountries. Inthe top panelofFigure 1,

we

have

plotted the standarddeviationof percapitaGDP

growthagainstthe log-level ofper capita

income

fora

largesample

of countries.We

refer tothisrelationship astheVolatility

Graph

and

note thatitis downward-sloping,meaning

that fluctuationsin percapitaincome

growth are smallerin rich countries than in poorones. In the bottom panelof Figure 1,

we

have

plotted thecorrelation ofpercapitaincome

growth rates with worldaverage

percapitaincome

growth (excluding thecountry in question) against thelog-level of percapita

income

forthesame

setofcountries.

We

referto this relationshipas

theComovement

Graph

and

notethatit isupward-sloping,

meaning

thatfluctuations inper capitaincome

growth aremore

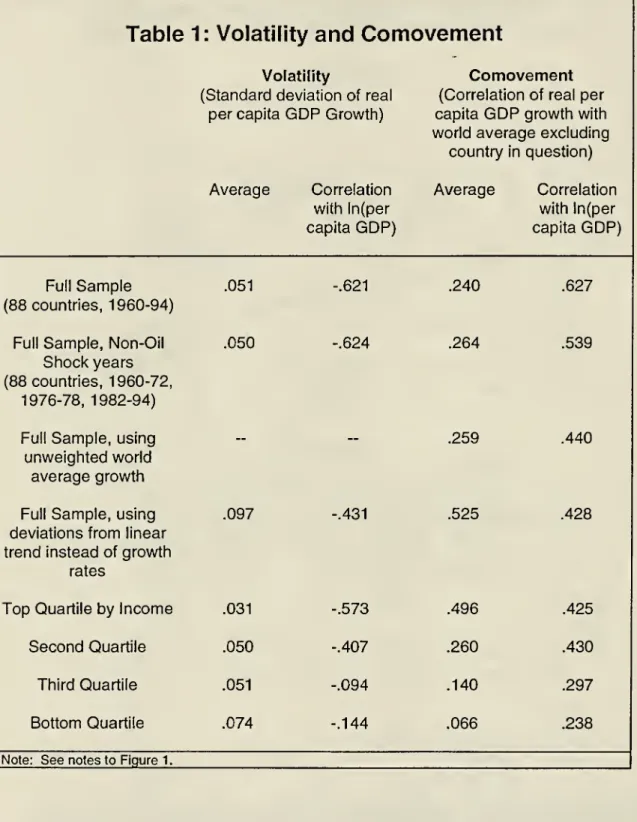

synchronizedwith the world cycle in rich countriesthan in poor ones. Table 1, which

isself-explanatory,

shows

thatthesefactsare quite robust.1Here

we

developtwo alternative but non-competing explanationsfor thesefacts. Both explanations rely

on

the notion thatthe lawof comparativeadvantagecauses

richcountries tospecialize in "high-tech" industries that require sophisticatedtechnologiesoperated

by

skilled workers, while poorcountriesspecializein "low-tech" industries that requiretraditional technologiesoperated byunskilledworkers. Thispattern of specialization

opens up

the possibilitythatcross-country differencesinbusinesscycles are

due

toasymmetries

between

high-techand

low-techindustries.Forinstance,

assume

thatproduction inhigh-tech industries ismore

sensitivetoforeign

shocks

and

less sensitive todomestic shocksthan in low-tech ones. Itfollowsimmediatelythatproduction in high-tech industries,

and

therefore in rich countries,would be more

synchronized with the world cycle than in low-tech ones. Moreover,tothe extentthatforeign

shocks

arean average

ofthe domesticshocks

ofmany

othercountries, itis reasonableto expect thatforeign shocks areless volatile than

domesticshocks.

As

a

result, production in high-tech industries,and

therefore in richcountries,

would

alsobe

less volatilethan in low-tech ones.1

AcemogluandZilibotti(1997) also present theVolatilitygraph.

We

areunawareofanyprevious referencetotheComovementgraph.One

explanation ofwhy

industries reactdifferentlyto shocks isbased on

the ideathatproducers in high-tech industriesenjoymore

marketpower

than producersin low-tech industries.

We

referto thisasymmetry

among

industries asthe"competition bias" hypothesis. This bias

would

occur, forinstance, if differences inproduction costs

among

firms aremore

prevalentin high-tech industries.These

costdifferences sheltertechnological leadersfrom theircompetitors

and

make

them

large suppliers in international markets.This competition biashas implicationsfor

how

industries reacttodomesticand

foreign shocks. Considerthe effects ofafavourabledomesticshock

that reducesunitcostsin all industries. Since producersin high-tech industriesare large suppliers

in international markets, increases in theirproduction lowerprices, moderating the

effects ofthe shock. Since producers in low-tech industriesare small suppliers in

world markets, increases in theirproduction

have

littleor noeffecton

theirprices.To

the extentthatthe competition biasis important,

one

would thereforeexpectthathigh-tech industries are less sensitiveto domesticshocksthan low-tech industries.

Considernext the effects of

a

foreignshock

that raises productionand income

abroad and,as a result, increases

demand

in all industries. Since producers inhigh-tech industriesare large suppliers in international markets, this

shock

istranslatedintoa large shift in theirindustry

demand

which leadsto large increases in productionand

prices. Since producers in low-tech industriesare small suppliers in internationalmarkets, this

shock

has a negligible effecton

their industrydemand

as

most

ofthe increase in worlddemand

ismet

byincreases in production abroad.To

the extentthatthecompetition bias isimportant,

one would

therefore expectthat high-techindustries are

more

sensitive toforeign shocksthan low-tech industries.Anotherexplanation for

why

industries reactdifferentlytoshocks

isbased on

theideathat unitcosts in the lattermightbe

more

sensitive totheshocks

thatdrivebusinesscycles than inthe former.

We

referto thisasymmetry

among

industriesasthe"cyclicalbias" hypothesis. Ifbusiness cycles are driven byproductivityshocks,

business cycles are driven

by monetary

shocks, this bias mightarise ifcash-in-advance

constraints aremore

prevalentforfirms in low-tech industries.This cyclical bias also has implicationsfor

how

industries reacttodomesticand

foreign shocks. Almost by assumption, thecyclical bias implies that favourabledomesticshocks reduce unit costsin low-tech industries

more

than in high-techindustries, leading tolargerincreases in production in theformerthan in the latter.

Thisis

how

the cyclical bias explainswhy

high-tech industries areless sensitive todomestic

shocks

than low-techindustries. Less obviously,the cyclical bias alsoimplies that high-tech industriesare

more

sensitive toforeignshocks

than low-techindustries.

To

see

this, considerthe effects ofa favourableshock

that raisesproduction

and income

abroad.The

cyclical bias implies thatworldwide productionoflow-tech products increases relative to thatof high-tech products, raisingthe relative

price ofhigh-tech products.

From

the perspective ofthe domesticeconomy,

thisconstitutes afavourable

shock

forproducersofhigh-tech productsand an

adverseone

for low-tech producers.As

a result, high-tech industriesaremore

sensitive toforeign shocks than low-tech industries.

To

analyze these issueswe

constructastylizedworld equilibriummodel

of the cross-sectionofbusiness cycles. Inspired bythework

of Davis(1995),we

consider aworld in which differences in bothfactor

endowments

a la Heckscher-Ohlinand

industrytechnologies a la Ricardo

combine

todeterminea country'scomparativeadvantage

and, therefore, the patternsof specializationand

trade.We

subjectthisworld

economy

toboth the sortof productivity fluctuations thathave

been

emphasized

by Kydlandand

Prescott(1982),and

alsotomonetary

shocks thathave

real effectssince firmsface cash-in-advanceconstraints.

We

then characterize the cross-section ofbusiness cyclesand

findconditions under whichthe competitionand

cyclical biases

can be

used

to explain the evidence in Figure 1.The

model

issimpleenough

thatwe

obtainclosed-form solutionsfor all the expressionsof interest.We

alsofindthat ourresultshold

even

in the presence oftradefrictions, modelled here as"iceberg" transport costs, providedthatthesefrictionsare notso large asto altermagnify cross-country differences in business cycles. Finally,

we

show

that thetwo hypotheses underconsiderationhave

different implicationsfor thecyclical properties oftheterms oftrade. In principle, these propertiescan be used

to distinguishbetween

thetwo hypotheses. In practice, however, afirst look atthe datayieldsconflicting evidence.

The

research presented here isrelatedtothe largeliteratureon

open-economy

real business cycle models, surveyed by Backus,Kehoe

and

Kydland(1995)

and

Baxter (1995), thatexploreshow

productivityshocks are transmittedacross countries.

Our work

also relates torecentwork

byObstfeldand

Rogoff(1995,1998)

and

Corsettiand

Pesenti (1998) thatanalyzes theinternational transmissionofmonetary

shocks.We

differfrom these lines ofresearch intwo ways. Insteadofemphasizing theaspects in which businesscycles are similaracrosscountries,

we

focus

on

those aspects in whichthey are different. Instead offocusing primarilyon

the implications of international lending, risk-sharing

and

factormovements

forthe transmission of businesscycles,we

emphasize

the role ofcommodity

trade.2The

paperisorganizedas

follows. Section 1 develops the basicmodel.Section

2

explores the properties ofa cross-section ofbusiness cycles in the basicmodel. Section 3 extendsthe

model

byintroducingmoney.

Section4

furtherextendsthe

model

byintroducingtransport costs. Section 5examines

some

implications ofthe

model

forcyclical properties oftheterms oftrade. Section 6concludes.Previousliteratureonbusiness cyclesinopen economiestypicallyassumesthat either(a)thereisa

singlecommodity, sothatthereisno commoditytradewhatsoever,or(b)thatcountries arecompletely

specializedinthe productionofdifferentiated products. Whethersuchmodelsprovideagood

descriptionofobservedtrade patternshasnotbeen a major concernfor this literature. Incontrast,the

modelpresented hereisempiricallyconsistentwiththemainfeaturesofobservedtradepatterns: (a)a

largevolume oftradeamongrichcountriesinproductswith similar factor intensity (intraindustrytrade);

(b)substantialtradeamong richandpoorcountriesinproductswithdifferentfactor intensities

1.

A

Simple Model

of

Trade

and

Business

Cycles

We

consideraworldwith acontinuum ofcountrieswithmass

one; twoindustries, which

we

refertoas

the a-and

p-industries;and

two factors ofproduction,skilled

and

unskilledworkers. Countriesdifferin theirtechnologies, theirendowments

ofskilled

and

unskilled workersand

their level of productivity. In particular,each

countryisdefined

by

atriplet (n,8,7i),where

jj. isameasure

ofhow

advanced

thetechnologyofthe countryis, 8isthe fraction ofthe populationthat is skilled,

and

n

isan

indexofproductivity.We

assume

thatworkers cannot migrateand

that cross-country differences in technologyare stable, sothat)iand

8are constant.We

generate businesscycles byallowing the productivity index

n

to fluctuate randomly.The

a-and

p-industrieseach

contain a continuum of differentiated productsofmeasure one

which canbe

tradedat zero cost. Firms inthe a-industry usesophisticated technologies that require skilledlabour, whilefirms in the p-industry use

traditional technologiesthat

can

be

operated byboth skilledand

unskilledworkers.Not surprisingly,

we

shall find that richcountries thathave

bettertechnologiesand

ahigh proportion of skilledworkersexportmainlycc-products, whilepoor countriesthat

have

worse

technologiesand

a high proportion of unskilledworkers export mainlyp-products.

To

emphasize

the roleofcommodity

trade,we

ruleout trade infinancialinstruments.

To

simplifythe problemfurther,we

also ruleout investment. Jointly,these assumptions implythat countries

do

notsave.3Preferences

Each

country jspopulated by a continuum ofconsumers

who

differin their level ofskillsand

theirpersonal opportunity cost ofwork, orreservationwage.

We

3

index

consumers

by ie[1/y,00)and

assume

thatthis index isdistributed accordingto this Pareto distribution: P(i)=

1-

(y•\)~X

, with ?t>0,y>0.

A

consumer

with index imaximizes

thefollowing expected utility:E|U

ca(z,i) nV cp(i)1-v

1-v K|) i \e

-P-t.dt (1) /where

U(.) isany

well-behavedfunction; l(i) isan

indicatorfunction thattakes value 1ifthe

consumer works and

otherwise;and

ca(i)and

cp(i) are thefollowing

consumption indices ofa-

and

p-products:c«(i)

=

e e

_

1 e-i e-1 "•I e-i e-1

Jc

a(z,i) e dz cp(i)=

Jcp(z,i) e -dz_o

(2)

where

ca(z,i)and

cp(z,i)areconsumer

i'sconsumption ofvarietyzofthe a-and

p-industries, respectively.

The

elasticity ofsubstitutionbetween

industries isone, while the elasticityofsubstitutionbetween any

twovarieties withinan

industry is9, withe>i.

The

solution to theconsumer's problem isquite straightforward.Consumers

spend

a fractionv oftheirincome on

a-productsand

afraction 1-von

p-products.Moreover, the ratioofspending

on

any

twoa-products zand

z' isgivenby

Pa(z)

Pa(z')

1-e

;

and

the ratioofspendingon any

two p-productszand

z' isPp(z)

Pp(z') 1-e

where

pa(z)and

pp(z)denote the price ofvarietyzofthe a-

and

p-products, respectively. Finally,consumers work

ifand

onlyifthe applicablewage

(skilled orunskilled)

exceeds

a reservationwage

of i" 1V 1-v "1

Te

"1 1-eJp

a(z) 1-e -dz JPp(z) 1-d2

.0 .0 jWe

expressall prices in termsof the idealconsumer

price index, i.e.=

1. Let r(p.,8,7i)and

w(|j.,8,7t)be

thewages

of skilled

and

unskilled workers in a (p.,8,7i)-country. Also, define s(u.,8,7t)and

u(u.,8,rc)to

be

themeasure

ofskilledand

unskilledworkers thatareemployed.Under

theassumptionthatthe distribution ofskills

and

reservationwages

are independent,we

have

that s=

8-i r \ u=

(1-6) ( \x iw

\ 1 ) (3) (4)Equations (3)-(4)

show

that thefraction ofskilledand

unskilled workers thatareemployed

are f \x ' r ^ v lJand

'w

'y)

, respectively. Ifthe

wage

ofany

typeofworkerreachesy, theentire labour force ofthattype is

employed

and

the laboursupplyforthat typeofworkers

becomes

vertical. Throughout,we

shallassume

thatyis largeenough

sothat thisnever happens. Finally,we

notethatthe wage-elasticityofthelaboursupplies, "k, isthe

same

forboth typesof workerssince itonlydepends on

thedispersion of reservation

wages.

Firms

and Technology

The

oc-industry uses sophisticated production processesthatare not availabletoall countries

and

thatrequire skilledworkers. Lete~

ta'n

dz (ea>0)

be

the"best-practice" unitlabourrequirements to produce

one

unit ofa given small set of a-products ofmeasure

dz. Let (1+

Ti)e_£flc

'n

technology available toproduce

one

unit ofa given small set ofa-products ofmeasure

dz. Let\ibe

themeasure

of a-products inwhich a firm located in a(|a,8,7i)-country

owns

the best-practicetechnology.We

can interpret u.a natural indicator ofhow

advanced

thetechnology ofa countryis.Assume

further that theset ofa-products in which two or

more

firms share best-practicetechnology hasmeasure

1 1

zero. Jointly, theseassumptions implythat 1

=

J Ju.

•dF(|j.,8),

where

F(u.,8) is theoo

time-invariantjoint distribution function ofp.

and

8.We

shallassume

throughout thatti is large

enough

so thatthefirms thathave

the best-practice technologyare'defacto' monopolists in the marketfortheirproducts. Therefore, theiroptimal pricing policyis toset a

markup

overtheir unitcost.Symmetry

ensuresthat that allfirms inthe a-industry ofa (ji,5,7i)-countrysetthe

same

price, pa(p.,8,7i):Pa=^r.e-

£« n(5)

The

p-industry usestraditional technologiesthat areavailable inall countriesand

canbe

operated byboth skilledand

unskilledworkers. In particular,e~

p n -dz(ep>0)workersof

any

kind are requiredto produceone

unit ofa

given "small"set ofp-products of

measure

dz. Since all firmshave

accesstothesame

technologies, thep-industryis competitive

and

pricesare equalto costs.We

shallassume

throughoutthatin equilibrium skilled

wages

are highenough

thatonly unskilledworkers produceP-products.4

Symmetry

ensures thatall firmsinthe p-industry ofa

(^,8,7i)-countrysetthe

same

price, pp (n,8,7t):

Pp=w-e"

Epn (6)Two

featuresof this representation oftechnologyplayan

important rolethroughoutthe paper. First, theelasticity of substitution

among

varieties 6 regulatesthe extentto whichthecompetition bias isimportant. If is low (high), a-products are

perceived

as

different(similar) byconsumers

and, as aresult, firms in the a-industry faceweak

(strong) competitionfrom producersofothervarieties ofa-products.As

6->°°,the

degree

of competition in the a-industryincreasesand

the competition biasdisappears.

Second,

the parameters e„and

ep regulate the importanceofthecyclical bias. If ea<£p (£a>£p), unitcosts in the (3-industry (a-industry) are

more

sensitive to fluctuations in productivity.

As

£a->£p, the cyclical biasdisappears.Productivity

Fluctuations

We

generate business cyclesbyassuming

that the productivityindexfluctuatesrandomly. In particular,

we

assume

that%

consists ofthesum

of a globalcomponent,

n,and a

country-specificcomponent,

n-Yl.We

assume

thatthe globaland

country-specificcomponents

are independent,and moreover

thatthecountry-specific

components

are independent across countries. Both the globaland

country-specific

components

of productivity are reflected Brownian motionson

theinterval

n

n

2'2

, with zero driftand

instantaneousvariancesodt

and

(1-o)dtrespectively,

where n

isa

positiveconstantand 0<a<1

.These assumptions

implythatthe productivityindexitfollowsa

Brownian

motionwith zerodriftand

unitvariance reflected

on

the intervaln-*,n

+

*

2 2

Thisinterval itselffluctuatesover

time

as

the globalcomponent

ofproductivity changes. Finally, itisa

well-knownresultofthe theoryofreflected Brownian motionthat the invariant distributionsofthe

global

and

country-specificcomponents

of productivity, G(IT)and

G(7t-n), are uniformon

theintervaln

n

2'2

. 5We

assume

thatthe initialcross-sectional distributionof4

Thisisthecaseiftheshareofspendingona-productsnottoosmall, i.e.v»0.

5

thecountry-specific

component

ofproductivity is equal tothe invariantdistributionand hence does

notchange

overtime.From

the perspective ofa (u.,8,7t)-country,we

can refertochanges

in nand

n

as as domestic

and

foreign productivityshocks. Itisstraightforward toshow

thattheinstantaneouscorrelation

between

these shocks isVo

7.6

Thatis, the parameter

a

regulates the extenttowhichthe variation in domesticproductivity is

due

tothe global or country-specific components, i.e.whether

itcomes

fromdn

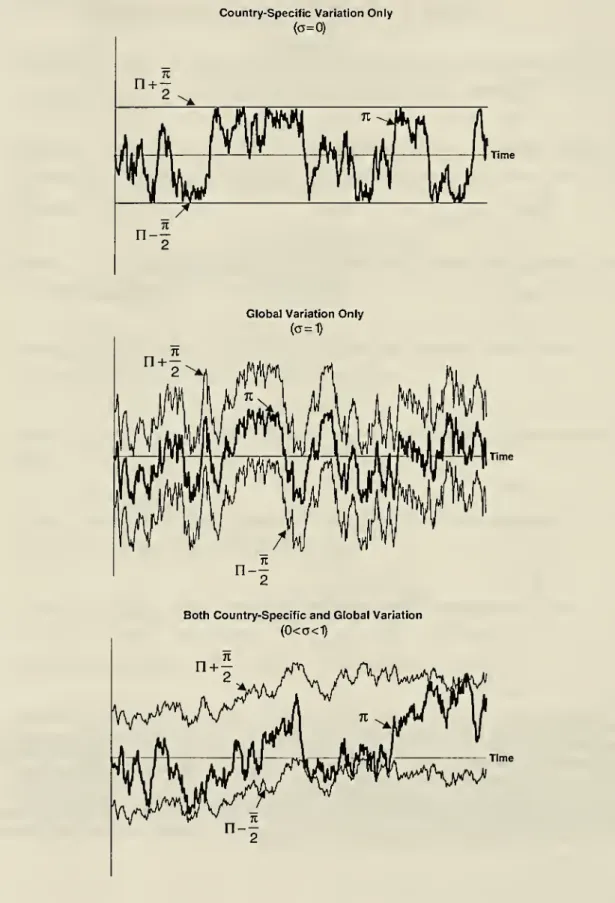

or d(7t-n). Figure2shows

possiblesample

pathsofn

underthree differentassumptions regarding a. Inthefirstpanel,

we

assume

thato=0, sothatn

isconstantand

all the variation in%

is country-specific.The

second

panelshows

thecase in which c=1. Then, djr=dnand

all the variation in

n

is global, i.e.changes

inn

areperfectly correlatedwithchanges

in global productivity, n.

The

third panelshows

thecase

inwhich0<o<1

. Then, thevariation in

%

is has both country-specificand

globalcomponents.

Equilibrium Prices

and Trade Flows

Letp

be

the average price ofan

oc-product(orthe ideal priceindex ofthecc-industry) relative totheaverage price ofa p-product product (orthe ideal price index

of the p-industry). Then,our normalization rule implies that

1 1 "1 1-e "1 1-e

Jp

a(z) 1-e -dz=

p1"vand

Jp

p(z) 1-e -dz .0 .0=

p v. Using this notation, theequilibrium prices of

any

a-productand

p-productproduced

ina (jj.,5,7t)-countryare:Pa=X"P

1-v V-1 1+A. 0+ *-.e e+x. ea (7t-n) (7)Thiswillbetrueexceptwheneithernor

n

arereflectedat theirrespective boundaries.Thesearerareevents sincethedatesatwhichthey occurconstituteasetofmeasurezerointhetimeline.

Pp

=

P_V

(8)where %

is a positiveconstant.7 Sinceeach

countryis a"large" producerof itsown

varieties of a-products, the price ofthese varieties

depends

negativelyon

thequantity produced. Countries with

many

skilledworkers(high 5)with relatively highproductivity (high 71-n) producing

a

smallnumber

ofvarieties (lowp.) produce largequantities of

each

varietyofthe a-productsand

as a result,face lowprices.As

8->oo,thedispersion in theirprices disappears

and

pa—

>p1"v

. Inthe p-industry all products

must

command

thesame

price. Otherwise, low-price varieties of (3-productswould

not

be

produced

in equilibrium. Finally,we

find thatthe equilibrium value forp is:p

=

vK-e(e0"£a)'

n

(9)

where

\\fis anotherpositiveconstant.8 In the presenceofa cyclical bias,e^ep

(£a>£p)» highproductivityisassociatedwith high (low) relative pricesfora-products as

theworldsupplyofp-products is high (low) relative tothat ofa-products.

As

£a-»£p,the cyclical biasdisappears

and

the relative prices ofboth industriesare unaffectedbythe level of productivity.

fi_i - 11 Tn^l e+x

(uT

(1+x)'e (7l_n)7

Inparticular, x = J JJji-

—

-e a dF(y,8)dG(jt-n),whichis-~o o ^Sj

constant giventhatthedistributions Fand

G

aretime-invariant. To deriveEquation(7),equatetheratio ofworldexpenditureonthe(sum ofall)a-productsofa (u,5,7i)-countryand a(u',8',7t')-countrytotheratio ofthevalueofproductions. Second, use Equations(3)-(6) to find that:P«' =Pre • •ee+^

a

. Finally,substitutethisexpression intheidealprice indexof

U-5'J

thecc-industryandsolvetor p„. Equation(8)issimplyaconsequenceofour normalization ruleandthe

observationthatallp-productscommandthesameprice inequilibrium.

1+1 R+i v ( e \x °° 11 (1+A.)-e R-(7i-n) 8 Inparticular, \v v = J JJ(1-5) e p dF(u,8) dG(n- n) .

1-v

V.O-V

^00

Toderive Equation(8),

we

equatetheratioofspendinginbothindustriestotheratioofworldwide productionofbothindustriesandthenuseEquations (3)-(7) tosolvefor p.Lety(|a,5,7i;)

and

x(|i,8,7t)be

theincome

and

theshare in production ofthea-r•s

industry, i.e.

y=rs+wu

and

x=

. Notsurprisingly, countrieswithgood

technologies (high u.)

and

a high proportion of skilledworkers (high 5)have

highvaluesforboth y

and

x.We

therefore referto countrieswith high valuesofxasrichcountries. Since

each

country producesan

infinitesimalnumber

of varieties ofcc-products

and

consumes

allofthem, all countries exportalmostall of theirproductionof a-products

and

import almostall oftheirconsumption

ofa-products.As

a share ofincome, theseexports

and

imports arexand

v, respectively. This kind oftrade is usually referred toas intraindustry trade, since it involvestwo-way

trade in productswith similar factorintensities.

To

balancetheirtrade, countrieswithx<v

exportp-products

and

countrieswith x>v importthem.As

a share ofincome, these exportsand

importsare v-xand

x-v, respectively. Thiskind oftrade is usuallyreferred toasinterindustrytrade orfactor-proportions trade.

As

a result, themodel

captures in a stylizedmanner

three broad empirical regularities regarding the patternsof trade: (a)a large

volume

ofintraindustry tradeamong

rich countries, (b) substantialinter-industrytrade

between

richand

poorcountries,and

(c) little tradeamong

poorcountries.

2.

The

Cross-section

of

Business

Cycles

In theworld

economy

described in the previoussection, countriesare subjecttotwo kinds ofshocks.

On

theone

hand, domesticproductivityshocks shift industry supplies.On

the other hand, foreign productivityshocks

shiftindustrydemands.

Inthe

presence

ofthe competition biasorthecyclical bias, theseshockshave

differenteffectsin high-tech

and

low-tech industries.As

a result, the aggregate response to similarshocks

differsacrosseconomies

with different industrial structures. Inotherwords, the propertiesofthe businesscyclesthatcountriesexperience

depend

on

thedeterminantsoftheir industrial structure, that is,

on

theirfactorendowments

and

technology.

Domestic

and

Foreign

Shocks

as

a

Source

ofBusiness

Cycles

The

(demeaned)

growth rate ofincome

in a (n.,8,7i)-country canbe

writtenasa linearcombination ofdomestic

and

foreign shocks:9dlny-E[dlny]

=

^Edn

+

^n

dn

(10)The

functions ^(\i,8,n)and

l,n(\i.,b,n)measure

thesensitivity ofa country'sgrowth rate todomestic

and

foreign shocks,and

are givenby:$K=<1 +

*.)-xe

f9-1

Q+ X

+

(1-x)-ep x'e«"rr^

+

(x" v)(e

«_e

P) W+

A (11) (12)Toseethis,applyIto'slemmatothedefinition ofincome and usetheexpressionsforequilibrium factor

pricesandsuppliesinEquations(3)-(9).

Equations (10)-(12) providea completecharacterization ofthe businesscycles

experienced by a (ji,8,7t)-country. Moreover, they

show

how

business cycles differacross countries, since thesensitivity ofgrowth ratesto domestic

and

foreign shocksdepends on

the share in production of high-tech products, x. Finally,we

note the thedetrended growth rate ofworld average income, Y, is given by

dlnY-E[dlnY] =

con

dn

(13)where

the sensitivity oftheworld growth rate to innovations inthe globalcomponent

of productivityis given by:

©n=(1

+

A.)-(v-ea +(1-v):e

p) (14)

LetV(u:,8,jt)denote the standard deviation ofthe growth rate ofa

(^1,8,71)-country,

and

letC(|i,8,7i) denotethe correlation of its growth ratewith world averageincome

growth.These

are thetheoretical analogsto theVolatilityand

Comovement

graphs in Figure 1. Using the Equations (10)-(14)

and

the properties ofthe shocks,we

derive the following result:10PROPOSITION

1:The

functionsC

and

V

depend, at most,on

x. Moreover:(i)lf £3

=£«•-—-,

then—

=

—

=

for all x;H

Q

+

X

dx dx(ii) If en

>

e„ , then——

<

and

——

>

forall x;and

w

P ae

+ X

dx dx(iii) If eR

<

e„ , then-—

>

and

—

-<

forall x.w

+

A. 3x dx10

Theproofissimple, since

we

haveclosed-formsolutionsforboth thevolatilityandcomovementstatistics: V =y(l-o)•Z,n +a (t,K +£

n

) and

C

= , . Since^+£nV(i-o)-§! +«•(£*

+Sn)

2

doesnotdependonx,V(C)willbedownward(upward) slopingifandonlyif

^

isdecreasingin x.Thepropositiondescribesthe sign of for different parametervalues.

9x

This isthefirst ofa series of results that relate

a

country's industrial structure,as

measured

byx,to the properties ofits business cycles. Proposition 1 says thatthetheoretical Volatility

and

Comovement

graphshave

thesame

slopes astheirempirical counterparts if thecompetition bias (low8) and/orthecyclical bias (ep>£a)

are strongenough. Equations (11)-(12)

show

thatthissame

parameter restrictionimplies that rich countriesare less sensitive to domestic

shocks

(i.e. £,n is decreasing with x), butmore

sensitivetoforeignshocks

(i.e. E,n is increasing with x). In theremainderofthis section

we

provide intuition for this result.Why

Are

Rich Countries

Less

Sensitive

To

Domestic

Shocks?

Domestic shocks

shiftindustry supplies.When

these shocks arepositive,they raise production,

wages

and

employment

in both industries.When

negative,they lower production,

wages

and employment. However,

tothe extent thatthecompetition bias

and

the cyclical bias are important,these effectsare larger in the p-industrythanthe a-industry.Itis useful tostartwith a

benchmark

case

in which 6->«>and

Ea=Ep=£, sothat neitherthe competition bias nor thecyclical biasare present.A

favourableproductivity

shock

results inan

increase in productivity ofmagnitude

e-drc in bothindustries,

and

has twofamiliar effects. Holding constantemployment,

increasedproductivity directlyraises production

and hence

income. This is nothing but the celebratedSolow

residualand

consistsofthesum

ofthe growth rates of productivity ofboth sectors, weighted bytheirsharesin production, i.e.e-drc. Increasedfactor productivityalso raisesthewages

ofskilledand

unskilled workersand, asa

result,employment,

outputand income

risefurther. This contribution ofemployment

growthto thegrowth rateof

income

ismeasured by

Xedm,

and

its strengthdepends on

theelasticityofthe laboursupply to

changes

inwages,

X. Favourable domesticshockstherefore raisegrowth rates in all countriesbythe

same

magnitude, i.e. (1+X)edn.To

seehow

the competition bias determineshow

a countryreactsto domesticshocks,

assume

thatG isfiniteand

ea=ep=e.As

in thebenchmark

case, favourabledomesticshocks raise productivity equally in the a-

and

p-industries, raising wages,employment and

output. Thisiscapturedby

the term (1+A.)-£-djtasbefore. However,since thecountryis large in the marketsforitsa-products, increases in the supplyof

a-products are

met

with reductions in prices thatlower productionand

income. Thisstabilizingeffectof prices is

measured by

the term-x

•^—

•e•drc.

The

more

9

+

A.inelastic isthe

demand

facedbyeach

cc-product (theloweris 0)and

the larger is theshareofthe a-industry (the larger isx), the

more

important isthisstabilizing roleof prices. Since rich countrieshave

largercc-industries, domesticshockshave

smallereffects

on

theirgrowth rates, i.e. (1+

X) 1-

x •e•drc.

V, 9

+

KJTo

seehow

the cyclicalbias determineshow

a countryrespondsto domesticshocks,

assume

that0-»°<>and

£c<ep.Now

domesticshocks

raise productivityin the a-industrybyEa-dic,and

in the p-industryby

fy-dn.As

a result, both theSolow

residual

and

theemployment

effectwillbe

smallerin the a-industry than in thep-industry. Since richcountries

have

larger a-industries, domestic shockshave

smallereffects

on

theirgrowth rates, i.e. (1+

a)•[x ea

+

(1-

x)•epl-dn

. Clearly, if£a>£P, the

conversewill

be

true.To

sum

up, in all countries domesticproductivityshocks shiftoutwardsthe suppliesof a-and

p-products. Since richcountries produce mainly high-tech products, they face inelastic industrydemands

(i.e. the competition bias)and

experience relatively small shifts in supplies(i.e. the cyclical bias).

As

a

result, theeffectsofdomestic shocks

on income

are small in rich countries.Poor

countries, byvirtueofproducingprimarily low-tech products, face elasticindustry

demands

and

experience relativelylarge shiftsin supplies.This is

why

the effectson income

ofdomestic shocksare large in poorcountries.

Why

Are

Rich Countries

More

Sensitive

toForeign

Shocks?

Foreign

shocks

shiftindustrydemands.

For instance, positive shocks raiseproduction

and income

in the restof theworld, increasingdemand

forall products.Whether

this leadstoan

increase inthedemand

forthe domestic industrydepends

on

the extentto which the increase indemand

ismet

byan

increase in productionabroad.

To

the extentthatthe competition biasand

the cyclical bias areimportant,the increasein the

demand

for the a-industryisalways largerthan that ofthe(3-industry.

It isuseful to start again with the

benchmark case

in which neitherthecompetition biasnor the cyclical biasare present, i.e. 9->«>

and

Ea=ep=e.A

favourableforeign

shock

consists ofan

increase inaverage

productivityabroad

of magnitudeedn

in both industriesand

therefore raisesworldwidedemand

and

production ofboth a-

and

p-products.However,

itfollowsfrom Equation (12) thatthis hasno

effectinthe domestic

economy.

The

reason issimpleand

follows from threeassumptions.First, the assumptionof homothetic preferencesensures that, atgiven prices, the

relative

demands

forboth typesof products are unalteredas income

grows. Second,the assumptionthat £a=£p ensuresthat, atgiven prices, the relative supplies ofboth

industriesare unaltered asproductivitygrows. Third, our assumption that 0->°°

ensuresthat

consumers

areverywillingto switchtheirconsumption

expendituresover differentvarieties ofproducts.

The

firsttwoassumptions

mean

thatthe increases in theforeignsupplies ofboth industriesmatch

exactly the increase indemands

for bothindustries. Thisiswhy

pdoes

notchange

(recall Equation (9)).The

third assumption

means

thatdespite thechange

in relative supplies ofdifferentvarieties of cc-products, there are

no changes

in their relativeprices.To

see

how

the competition bias affectshow

a

country reacts to foreignshocks,

assume

that9 isfiniteand

ea=ep=e. It isstilltrue that aftera favourableforeign

shock

the increases in the foreign supplies of both industriesmatch

exactlythe increasein

demands

atthe industrylevel.As

a resultp is not affected.However,

since the increase in

demand

fordomestic cc-products is notmatched

by increasedproduction abroad, the price ofthesevarieties increases. This stimulates

wages,

employment and

production in the a-industry. Thiseffect ismeasured

byx•

—

•e drc,

and

is larger themore

inelastic is thedemand

faced byeach

a-+

A,product(the loweris6)

and

the largeris the share ofthe a-industry(the larger is x).Since rich countries

have

larger a-industries, foreign shockshave

larger effectson

theirgrowth rates.

To

see

how

the cyclical bias determineshow

a country reactstoforeignshocks,

assume

that 0->c»and

ea<sp. At given prices,we

have

now

thatafavourableforeign

shock

raises theworld supplyofoc-products ((3-products) byless (more) thanits

demand.

As

a result, there isan excess

demand

fora-productsand an

excesssupply ofp-products thatleadsto

an

increase in p (recall Equation (9)).From

thepointofviewof thecountry, this is

an

increase inthedemand

forthe domesticcc-industry

and

a decrease in thedemand

forthe domestic (5-industry.These

demand

shifts raisewages,

employment and

production inthe a-industry,while loweringthem

in the (3-industry.

The

combined

effect in both industries ismeasured

by(1

+

A.)•(x-

v)•fep-

ea)

and

its signdepends on

whetherthecountry is a netexporterofa-or p-products. Since rich countries

have

larger a-industries, foreign shockshave

larger effectson

their growth rates.To

sum

up,foreignshocks

shiftthedemands

ofboth industries athome.

Since rich countries

have

a largershareofhigh-tech products, theyhave

littlecompetitionfromforeign suppliers(i.e. the competition bias)

and

specializein industrieswhose

pricesmove

with the world cycle (i.e. the cyclical bias).As

a result,effectsofforeign shocksare positive

and

large. Poorcountriesproduce low-tech products and, as a result,face stiff competitionform abroadand

specialize inproducts

whose

pricemoves

against the worldcycle.As

a result, the effectsof foreignshocks are less positivethan in richcountries,and

theymighteven be

negative.

The

Role

ofCommodity

Trade

In this model, the propertiesof businesscycles differacrosscountries

because

countrieshave

different industrial structures, asmeasured

by x.There

aremany

determinants of the industrial structure ofa country.We

focus hereon

perhapsthe

most

importantof such determinants, thatis,a

country'sabilitytotrade. In fact, ifwe

deny

this abilityto thecountriesthat populateourtheoretical world, their businesscycles

would

have

identical properties. Ina world ofautarky, x=v in every countryand

commodity

pricesare determinedby

domesticconditions. In such aworld thesensitivities of growth rates to domestic

and

foreign shockswould be

thesame

in allcountries,

%^

=

(1+

X) v•ea

+

(1-

v)•egand

^

=

;

and

the Volatilityand

Comovement

graphswould

be

flat,V

=(1+

X)-C^Vc

7.

V£

a

+(1-V)£p

and

Moving

from aworld ofautarkyto a world offreetradeaffectsthe industrialstructure ofcountries since infreetradethe relative prices ofthose products in which

a countryhas comparative

advantage

are higher than in autarky. Higherpricesimply higher industryshares,even

ifproduction remains constant. Butone would

alsoexpect higherprices tostimulate

employment and

production.These

increases inemployment

couldcome

fromunemployment,

as isthe case in themodel

presentedhere.

Or

they couldcome

fromemployment

in otherindustries, as itwould

be

thecase

ifwe

changed

ourassumptionsand

allowed both industriesto use bothtypesofworkers.

11

Thisresultdependsontheassumptionthattheelasticityofsubstitutionbetweena-productsand

p-productsisone. Otherwise, industrialstructureswouldalsobedifferentinautarkyandthecross-section

ofbusiness cycleswouldexhibitsomevariation.

3.

Monetary

Policy

In thissection

we

extend themodel

byintroducingmonetary

shocks asan

additional source ofbusiness cyclesfluctuations.

As

is customaryin the literatureon

money

and

businesscycles,we

assume

thatmonetary

policy is erratic. Thissimplificationis

adequate

ifone

takes the viewthatmonetary

policy hasobjectivesotherthanstabilizing thecycle. For instance, ifthe inflationtax is

used

to financeapublicgood, shockstothe marginal valueof thispublic

good

are translated intoshocks tothe rate of

money

growth. Alternatively, ifa

countryiscommitted tomaintaining afixed parity,

shocks

to foreign investors' confidence in the countryaretranslated into shocksto the nominal interest rate,asthe

monetary

authoritiesusethe latterto

manage

theexchange

rate.We

motivate the use ofmoney

by assuming

thatfirmsfaceacash-in-advance

constraint.12 In particular, firmshave

to usecash in ordertopay

a fraction oftheir

wage

payments

before production starts. Firms borrowcash fromthegovernment and

repaythe cash plusinterestafterproduction iscompletedand

outputis soldtoconsumers.

Monetary

policyconsistsof settingthe interest rateon

cash,

and

then distributing theproceeds

orlosses inalump-sum

fashionamong

consumers. Increases inthe interest rate raise the financing costsoffirms, reducing

wages,

employment and

output. Inthis model, interest-rate shocks are thereforeformally equivalenttosupply

shocks such as changes

in production or payroll taxes.The

Model

with

Money

Leti

be

theinterest rateon

cash. Sincemonetary

policyvaries acrosscountries,

each

countryisnow

defined bya

quadruplet(n,8,7t,i).We

constructtheprocessforinterest-rate

shocks

followingthesame

stepswe

used

to constructthe12

SeeChristiano,Eichenbaum and Evans(1997)foradiscussionofrelatedmodels.

processfor productivity

shocks

in Section 1.The

interest rateiconsists oftwoindependentpieces: a global

component,

I,and

a country-specificcomponent,

i-I.Moreover, the country-specific

components

are independent acrosscountries. Boththe global

component

and

the country-specificcomponents

of interestrates arereflecting Brownian motions

on

the intervali i

2'2

, with zerodriftand

instantaneous variances<|>-dt

and

(1 -<J))dt respectively,where

i is a positive constantand

0<())<1.These

assumptions

implythat the interest ratei isa Brownian motiont l T l

2 2

The

initialwith zerodrift

and

unitvariance reflectedon

the intervalcross-sectional distribution ofthe country-specific

components,

H(i-I), is uniformon

and hence does

notchange

overtime.From

the perspective ofa(u.,8,7i,i)-i i

2'2

country,

we

definediand

dlas domesticand

foreign interest-rate shocksand

notethattheircorrelation coefficient

is^.

Finally, productivityshocksand

interest-rateshocks

areassumed

tobe

independent.The

introduction ofmonetary

policy leads to minorchanges

in the equilibriumofthe model. Since cash-in-advance constraintsonlyaffectfirms, theconsumer's problem is notaltered

and

both thespending rulesand

the labour supplies inEquations (3)-(4) remain valid. Regardingfirms,

we

assume

thata

fraction ofwage

payments

k„and

Kpinthe a-and

p-industrieshave

tobe

made

incash

beforeproduction starts. Consequently, the costsof producinga small set ofproductsof

measure

dz includenot only the unitlabourrequirements,e~

Za'K

dz

and

e~

zV'n -dz, but also the financing costs, eKa'

l

dz

and

eKpl-dz.13As

a

result,Equations (5)-(6)

have

tobe

replaced by:p

a=

JL.

r.e—

°l

(15)

13

We

are usingthe followingapproximationshere: Ka-i^lnO+Ka-i)andKpi=ln(1+K Pi).pp

=w-e

^

pl(16)

An

interesting novelty ofthemodel

withmoney

is that it indicatesanotherpotential sourceforthe cyclical bias.

Even

if productivity is equallyvolatile in bothindustries, i.e. £a=ep, unitcosts could still

be more

volatile in the p-industry ifthecash-in-advance constraintis

more

bindingthere, Kp>K„. Finally,a straightforwardextension ofthe

arguments

in Section 1 can beused

toshow

that Equation (8) isstill valid,while Equations (7)and

(9)must be

replaced by:14Pa=x-P

1 -V{fj

-e~

«*

(17) p=

¥

.e {ep-e«)n

-^

( ' Kp"KjI

(18)Equations (15)-(18)are natural generalizationsof Equations(5), (6), (7)

and

(9).

As

the cash-in-advance constraintsbecome

less important, i.e. k^->0and

Kp-»0,this

model

convergesto themodel

withoutmoney

presented in Section 1.

Properties

ofBusiness

Cycles

With the additionof interest-rateshocks,

income

growth inthe(|i,8,7i,i)-country is given bythisgeneralization of Equation (10):15

14

Theconstants%and\\tarenowgivenby:

X "1

= J J

HH^

G

-

e8+X

'«*

V

.dF(^8).dG(K-n).dH(v-I)i+i o+i v ( e

^

co co 11 [(i+X)ER-(7t-n)-x-KB-(i-i)J¥

i+ x x e+x = r b ; j JJ(1_6).eV P P >*.dF0i.8).dG(7t-n).dH(i-i)1-v

\?-V

^o-^rjO 15To computeincome,rememberthat financingcosts arenotreallyacostfortheeconomyasa whole

butatransferfromfirmstoconsumersviathegovernment.

dlny-E[dlny]

=

^

d7c+

§n

dn-^

di-^

dl (19)where

^(h,8,tc,i)and

£n(|-i,S,7t,i) arestill definedby

Equations (11)-(12)and

^(|j.,8,7t,i)and

£,(11,8,71,1), whichmeasure

the sensitivityofincome

growth todomesticand

foreign interest-rate shocks, are given by:

5i

=

\-e-1

XK„

a Q+

X

Si=

1-1+ 1

X-K„

a Q+ X

+

(1-X)Kp

(20) (21)Equations (11)-(12)

and

(19)-(21) provide a complete characterizationof thebusiness cycles ofa (u.,8,7t,i)-country.

As

k^O

and

Kp->0,we

have

that£,->0and

£i->0

and

business cycles are driven onlybyproductivity shocks.As

e„->0and

Ep->0,we

have

thatZ,K-^>0and

i;n->0and

businesscycles aredriven onlybyinterest-rateshocks. In the general case,

however

businesscycles resultfromthe interaction ofboth typeofshocks.

A

comparison

of (20)-(21)with (11)-(12) reveals thatthe effects ofdomesticand

foreignmonetary

shocks

are verysimilartothoseof productivityshocks.As

mentionedearlier, differences in the prevalenceofcash-in-advanceconstraintsprovide

an

alternative sourceofcyclical bias, i.e. Kaand

Kpplay thesame

role in (20)and

(21)as

e„and

epdo

in (11)and

(12). In contrastto productivityshocks, however,monetary shocks

onlyhave

indirecteffectson

production through theireffectson

wages

and

laboursupplies. Therefore, thesensitivityofincome

growth tomonetary

shocks issmaller, i.e. theterm (1+X) which premultiplies (11)

and

(12) is replacedwith A,.

Since

we now

have

two sources ofbusiness cycles, world average growth isgiven by:

dlnY-E[dlnY]

=

condn-(0[

dl (22)where

con is still defined by Equation (14) while co, is given by:a>

I

=A.-[v-K

+(1-v).Kp]

(23)Ifproductivity

shocks

are negligible ea=ep=0,we

have

thefollowing result:16

PROPOSITION

2:The

functionsC

and

V

depend, at most,on

x. Moreover:(i) If kr

= k„

, then-—

=

——

=

forall x;w

p aQ

+

X

dx dx(ii) If Kn

>

k„

, then—

<

and

—

> forall x;and

w

p aQ

+

X

dx dx(n) If kr

<

k„

, then—

>

and

—

<

forall x.p

Q

+ X

dx dxProposition 2 is the natural analogto Proposition 1 in aworld in which

business cycles are driven only byinterest-rate shocks.

The

competitionand

cyclicalbiases

cause

cross-country differences in businesscycles, regardlessofwhether

thecycles are driven by productivity

shocks

or interest-rate shocks.The

intuition ofwhy

thecompetition biasand

the cyclical bias generate these patternsina cross-sectionofbusiness cycles

has

been

discussed at length in Section2and need

notbe

16

Notethatinthiscase

v-j[i-.).{?,..(

t,.{,)i!

M

dc..

kMM

r

TheproofisanalogoustothatofProposition 1

.

repeated here. Instead,

we

generalize Propositions 1and

2 tothe casewhere

bothproductivity shocks

and

interest rateshocks

drive businesscycles, asfollows:17av

PROPOSITION

3:The

functionsC

and

V

depend, atmost,on

x. Moreover, if—

<

3x (

—

>0),

then—

>0

(—

<0).

Define: 3x 3x 3x ? (0-1

"\ ? (6-1

^A

= (1-a)-0+*r-|e

o

-Q^-epJ-ep+(1-*)-*

-IK

a-^-^-K

pJ-Kp

;B

=

(1-c).(1+

X)2{e„.^I-e

p)+

(l-«.»?

.(«..£!-«,

J

Then,(i) IfA>0,

—

>

forall x;3x

(iij if-B<A<0,

—

<0

(—

>0)

ifx<--

(x>--);and

3x dx

B

B

(iii) ifA<-B, then

—

<

forall x.3x

Proposition3 provides

a

set of necessaryand

sufficient conditionsforthe functionsV

and

C

to exhibitthesame

slopesthantheirempirical counterparts. Let x*be

the highestvaluefor xin a cross-section ofcountries.Then, a necessaryand

sufficientcondition forbusinesscyclesto

be

lessvolatileand

more

synchronized withtheworld cycle in rich countries isthat

A+Bx*<0.

Thiscondition isalwayssatisfied ifbothtypesof

shocks

generate industry responseswith the rightbiases, i.e.17

Notethat

V

=^(1-c)-^

+a-£

n +Sn)2+(1-4>K?

+4>-(Si +Sl)2

and

a-«>n"ten +Sn> +*-

m

i-($i-HJi)C

= Sinceneithery(o-o>ft

+**»?)-((1-oK|

+o(U

+S

n

)2

+(1-4>K

2+<MSi

+^i)2

)

2 2

^,,+^nnor %,+tndependonx,

V

(C) isdownward (upward)slopingifandonlyif (1-o)-i,n +(1-<t>)• %x isdecreasing(increasing) in x.Thepropositiondescribes thesignof

—

1(1-o)•Z,n +(1-<|>)•£,

x Ifor

3xv '

differentparametervalues.

£r

>

Enand

Kn>

k„

. Butthis is nota necessarycondition. Forinstance, itmight bethatthe cc-industryis

more

sensitive todomestic productivity(interest-rate)shocks

and

lesssensitive to foreign productivity (interest-rate)shocks6—1

6—1

than the (3-industry, £r

<

ea (kr< K

a -), yetstill business cycles are6

+

A, 6+

A.less volatile

and

more

synchronized with theworld cycle in rich countries. Thisnaturallyrequiresthatthe cc-industry

be

less sensitive todomesticinterest-rate (productivity)shocksand

more

sensitive toforeign interest-rate (productivity)shocks,6-1

,6-1

,K

P

>K

a-—

(ep>e

a-

—

).4.

Trade

Integration

The

postwarperiod hasseen

large reductionsin both physicaland

policybarriers to

commodity

trade.Here

we

do

notattemptto explain thesechanges

but instead explorehow

parametric reductions in transport costsaffectthe cross-sectionofbusiness cycles. Throughout,

we

assume

that transportcostsare smallenough

relativeto cross-country differences in factor

endowments

that all countries areeithernetimporters or netexporters ofthe p-product, for

any

value oftheirdomesticproductivity

and

interest rates,and

forall possible equilibrium prices. Moreover,we

assume

thattransportcosts are smallenough

relative tocross-country differences intechnologyin the a-industrythateverya-product continuesto

be

produced

in onlyone

country.These

assumptions ensure thatthe pattern oftrade isunchanged

bytheintroduction oftransport costs, although the

volume

oftrade is negatively relatedtothe size of transportcosts.

Remember

thatthemain

theme

of thispaper

is thatthe nature ofbusinesscycles

a

country experiencesdepends on

its industrial structure.As

transport costsdecline, the pricesofproducts inwhich a countryhas comparative

advantage

increaseand, as a result,the share in productionofthese industries increases.

A

naturalconclusion ofthis

argument

is thatone

should expectthatreductionsintransportcosts (globalization?) increase the cross-countryvariation inthe properties

ofbusiness cycles.

We

confirm this intuition here.The

Model

with

Transport

Costs

We

generalize themodel

withmoney

byassuming

thattrade incurs transportcostsofthe "iceberg"variety, i.e. ift>1 units ofoutput are shipped across borders,

only

one

unitarrives at the destinationwhilex-1 units "melt" in transit. Let p«(z)and

Pp(z)

now

denote thef.o.b. or international price of variety zofthe a-productsand

ofthe p-products, respectively.

We

use thesame

normalization ruleas

before in terms of theseinternational prices,and

define p as astheaverage

f.o.b. price ofa-productsrelative to p-products.

The

presenceof transportcosts implies thatthe c.i.f. ordomestic product prices varyacrosscountries. In

each

country, the c.i.f. prices ofimports

and

import-competing products are higher than thef.o.b. priceswhile thec.i.f. prices ofexports are equal tothef.o.b. prices. Since countries importall the

varieties ofa-products they

do

not produce, the c.i.f. price ofall but the infinitesimalmeasure

u.ofdomestically-produced a-products is x- pa(z). Similarly, thec.i.f. price ofP-products is xpp(z) ifthe country is

a

net importerof p-products,and

pp(z)otherwise.

Note thatthe

consumer

continuesto allocateconsumption

expenditures(evaluated atc.i.f. prices) overcommodities exactlyasbefore.

The

consumer'slaboursupply decision is also

unchanged:

consumers work

ifand

only iftheapplicable

wage,

expressed in termsof a unitofconsumption,exceeds

theirreservation

wage. However,

sinceconsumers

located in differentcountriesfacedifferentc.i.f. prices, theprice of a unitof

consumption

now

variesacross countries.Letpc(n,8,rc,i) denotethe ideal price indexof

consumption

ina

(u.,8,7r,i)-country. Thisindexisgiven byxifthe countryis a net importerofthe p-product,

and

xvotherwise.18 Therefore,we

need

to replace Equations (3)-(4) bythefollowinggeneralizations:r s

=

5-( r ^YPc

(w

> u=

(1-8)--?-U-Pcy

(24) X (25) 18Toseethis,usethenormalizationruleandrecallthatallcountriesimportallbut theinfinitesmal

numberofa-productsproduceddomestically,andsoincurrthetransportcoston(almost)theirentire

consumptionofa-products,whichconstituteafractionvoftotalexpenditure. Inaddition,consumersin

countries thatarenetimportersofp-productsfaceac.i.f.priceofxp

pfor theirremaining expenditureon

P-products.

Since a-productsare exported in all countries, producers face identical c.i.f.

and

f.o.b. prices and, as a result, Equation (15) isstill valid.However,

Equation (16)isonlyvalid in countriesthat export p-products. In countries thatimport p-products, the producer price oftheseproducts isT-pp, and,

as

a result, Equation (16) hastobe

replaced by: T-p p

=w-e"

E P-7C+KPl (26)Straightforward but

somewhat

tedious algebra revealsthatthe expressionsfor equilibrium pricesin Equations (8), (17)

and

(18) still hold, provided thatwe

replace 8

and

1-8with 8•x~x

and

x•(1-

8) ifthecountry is a net importerofp-products,

and

with 5-t4v

and

(1-8)-t~*"v otherwise.19Whiletrade patternsare unchanged, the world

economy

with transport costsexhibits lesscross-countryvariation in industrialstructures than the world

economy

with free trade.

The

higher the transport costs are, the loweristhe price ofthoseindustries inwhich thecountry has comparative advantage. Thatis, the loweris the price of a-products (P-products) in rich (poor) countries. Forthe reasons

mentioned

before,this leads to

an

reduction inthe share ofthecc-industry (P-industry) in rich(poor) countries.20

19

ToderivetheanalogtoEquation(17),

we

can equatethe ratioofworldexpenditureonthe(sumofall)a-productsinany twocountriestothe ratioof the valueofproductionsasbefore. Usingthenew

expressionsforwagesintheexpressionsforfactorsuppliesresultsin

1 (..,<! -A.

Wi

1+x .. /- „M x Pa' =Pa

u'-6 pC

H-6p

c

, Q+X^•

ea-(*-n,)-77r

Ka-(i-i')•eH+K 1 A . Insertingthisintheideal priceindex

forthe a-industryyieldsthe appropriatemodificationofEquation (17). Equation(8) issimplya

consequenceofourunchangednormalizationrule.ToobtaintheanalogtoEquation (18),notefirstthat thepresenceoftransportcostsimplies thatthemarket-clearingconditionsinthea-andp-lndustries

cannowbe expressed asequating the valueofworld productionatproducerprices tothevalueofworld

consumptionatconsumerpricesforalla-andp-products.Then, using the analogtoEquation (17),the

newexpressionsforfactor prices,andthe factorsupplieswecan equatetheratioofexpenditureinboth

industriestothe ratioofproductionsatproducerpricestoobtainthe appropriate modificationof (18).

20

Itisstraightforward toverify thisbysubstitutingtheexpressionsforequilibriumwages and

employmentintothedefinitionofxanddifferentiatingwith respecttox.

Business

Cycles

and

Transport

Costs

The

(demeaned)

growth rate ofincome

isstill given by Equations (11)-(12)and

(19)-(21). Consequently, Proposition 3 relatingthe properties of businesscyclestoa country'sindustrial structure still holds.

However,

transportcosts reducethevolume

oftrade and, as a result, the cross-sectional dispersion inx.This implies thatthecross-section of businesscycles exhibits less variation in the

model

with transportcoststhan in the free-trademodel.

A

processof parametric reductionsintransportcostshas

opposite effectson

the business cyclesof rich

and

poorcountries. Ifthecompetitionand

cyclical biasesare important,

we

know

thatthe Volatilityand

Comovement

graphs aredownward

and

upward

slopingwith x, respectively. Therefore, reductions intransport costslowerthe volatilityofbusinesscycles in rich countries (as theirx increases)

and

raisevolatility in poorcountries (astheirx decreases). Similarly, reductions intransport

costs

make

business cyclesmore

synchronized with theworld cycle in rich countries(astheirx increases)

and

less synchronized with theworld cycle inpoorcountries(astheirxdecreases).