Dispossessing the Public: Privatization of Open

Public Spaces in Lima, Peru

By

Daniela Chong Lugon

Bachelor of Architecture, Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru (PUCP) (2012)

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master in City Planning at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

September 2020

© 2020 Daniela Chong Lugon. All Rights Reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in

whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created.

Author_______________________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning

June 22, 2020 Certified by ___________________________________________________________________________ Lawrence J. Vale Associate Dean, School of Architecture and Planning Ford Professor of Urban Design and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by___________________________________________________________________________ Ceasar McDowell Professor of the Practice Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Dispossessing the Public: Privatization of

Open Public Spaces in Lima, Peru

By Daniela Chong Lugon

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on June 22, 2020, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning.

Abstract

The Metropolitan Area of Lima has on average 3.6m2 of green area per person, for a total of 10 million inhabitants. Although this is not the most accurate metric, it is the most available proxy to measure and understand the magnitude of open public space in the city. In addition, it is not equitably distributed: districts with higher socioeconomic levels and larger municipal budgets have greater area and higher quality public spaces. In a context of inequitable distribution on quantity and quality, one of the biggest threats that public spaces face is their privatization, a process in which a space is dispossessed from the public and transformed for a private or restricted use. From sidewalks, streets, parks, and plazas, to natural spaces such as beaches and the coastal lomas natural ecosystems, in recent years, these unprotected areas have become shopping centers, supermarkets, parking lots, private clubs, formal and informal housing, amusement parks, synthetic grass courts, and other infrastructure that has altered at some degree its openness, ownership, accessibility, and function. This shift from public to private spaces ultimately reduces the opportunity of all citizens to have available open public spaces, increases social fragmentation, and ultimately deepens issues of social injustice and spatial inequalities.

In such a scenario, this thesis examines the conditions under which open public spaces are privatized and identifies the mechanisms. Through different case studies and interviews, I create three types that attempt to explain the different forms in which privatization develops to expose the motivations behind it, the processes of how it happens, the actors who are involved, and the manifestations it has in the built environment. The first type is Concession for Development, and takes place when public space is rented to private entities in the form of concessions with the excuse of bringing development and improvement. The second is Appropriation for Livelihood, and occurs when public space is informally appropriated to fulfill a basic need such as housing or a productive activity. The third is Enclosure for Control, and results when public space is enclosed and its access is restricted in order to provide safety or facilitate its management. I analyze and expose the structural governance conditions and flaws in current planning processes — formal and informal, top-down and bottom-up — that lead to privatization in order to help create awareness about how and why this invisible phenomenon takes place and who is most affected by it. Finally, this thesis proposes recommendations that can help Lima and other Peruvian cities promote the protection and preservation of public spaces and also encourage a more equitable distribution.

Thesis Advisor: Lawrence Vale, Associate Dean, School of Architecture and Planning & Ford Professor

of Urban Design and Planning, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, MIT

Reader: Sharif Kahatt, Professor at Department of Architecture and Urbanism, Pontifical Catholic

Acknowledgements

These past two years at DUSP have been an amazing journey. The courses, projects, and the process of writing a thesis were challenging, yet incredibly rewarding. I want to thank the people who supported and guided me throughout this process.

To Larry, my advisor, I feel honored to have had the opportunity to work with you. Your thorough revisions, feedback, and comments helped me to constantly improve my research and work. Thank you for your continuous support, guidance, and encouragement, you have helped me grow as a person and as a professional. To Sharif, thank you for being my ground wire to Lima and for providing me enriching advice filled with wisdom that only grows from experience and local insights.

To all the DUSP community, thank you for all the moments and memories shared and for the most interesting discussions I have ever been part of, they have fed my soul and brain. To the DUSP latines, older and younger generations, you have all been very special in my journey through MIT. To my peers Nati, Vane, Diego, and Dani, I would not have been able to do this without you! Thank you to the Casa Latina crew, former, and current: Mechi, Jess, Mori, Fio, and Luismi, you gave me the best home and companionship along these past two years.

To my family, thank you for their constant support and cheers although the distance and for always believing in me. Last but not least, I want to thank Humberto, for the edits and uncovering my typos, for your support 24/7, and for your constant encouragement to be better. I couldn’t have done this without you.

Table of Contents

Introduction ... 8

1.1 Research Question... 10

1.2 Methodology ... 11

Case Studies Selection ...12

Semi-structured interviews and site visits ...12

Limitations ...15

Literature Review ... 16

2.1 Public Spaces Theories ... 16

Definitions of Public Space ...16

The Role of Public Space ...17

2.2 Privatization Theories ... 17

Definition of Privatization ...17

Other Forms of Privatization ...19

Privatization of Public Spaces in Lima, Peru...20

2.3 Metropolitan Governance Theories ... 21

Governance Structures and Models ...21

The Challenges of Effective Metropolitan Governance ...22

Context... 24

3.1 Lima’s Governance Structure and Challenges ... 24

3.2 Lima’s Urban Transformation and the Role of Public Spaces ... 26

3.3 Lima’s Public Spaces and their Governance ... 27

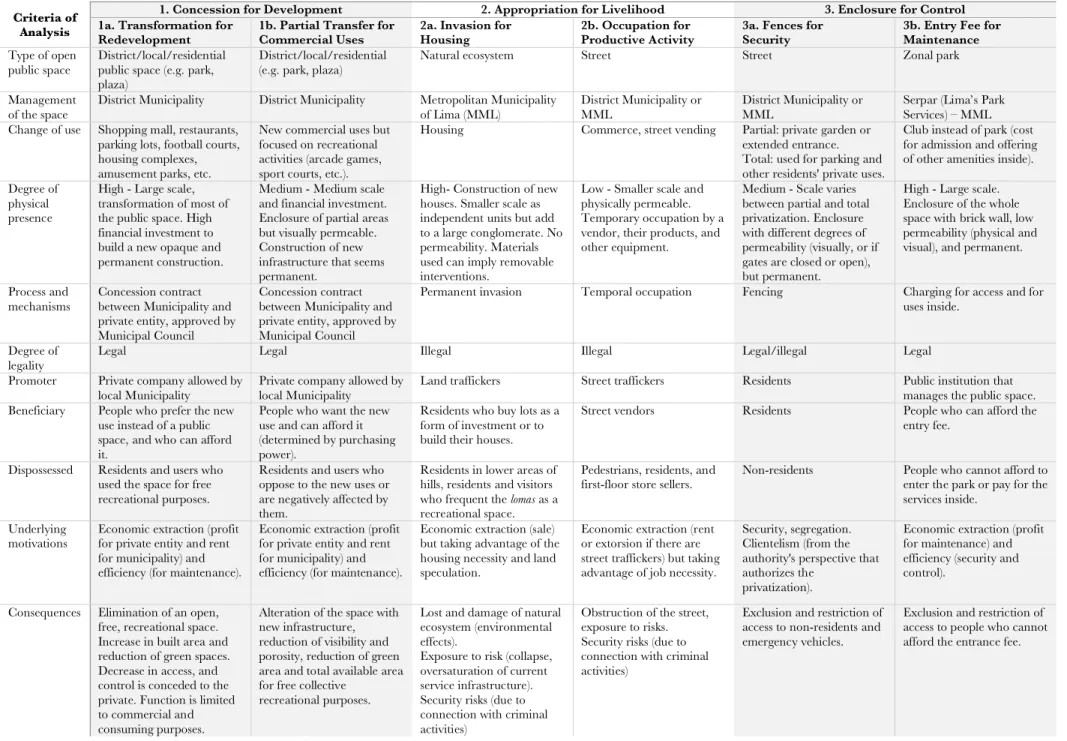

Types of Privatization and Case Studies ... 30

4.1 Building a Typology of Privatization ... 30

Criteria to Classify Types ...30

4.2 Privatization Types ... 31

Type 1: Concession for Development ...33

Type 2: Appropriation for Livelihood ...39

Type 3: Enclosure for Control...45

Findings: Who, Why, How? ... 53

5.2 Why are open public spaces privatized? ... 53

Indifferent State of Authority and Lack of Control ...54

Promotion of Private Developments and the Neglect Towards Open Public Spaces ...56

Privatization for Economic Extraction...57

5.3 How is Privatization Stopped? ... 59

Stopping Privatization and its Challenges ...59

Case Study of Bottom-up Stoppage: Manhattan Park and CADNEP ...61

An Attempt at Top-down Stoppage: Bill in Defense of Public Spaces ...64

Conclusions ... 66

6.1 Privatization as One Phenomenon: The Effects and Consequences at the City Scale ... 66

6.2 The Different Scales of Impact of Privatization ... 67

6.3 Recommendations ... 69

Legal Framework at a National Policy Level ...69

A New Governance Institution: Lima’s Public Space Authority ...69

Appendix 1 List of Interviews ... 74

List of Figures and Tables

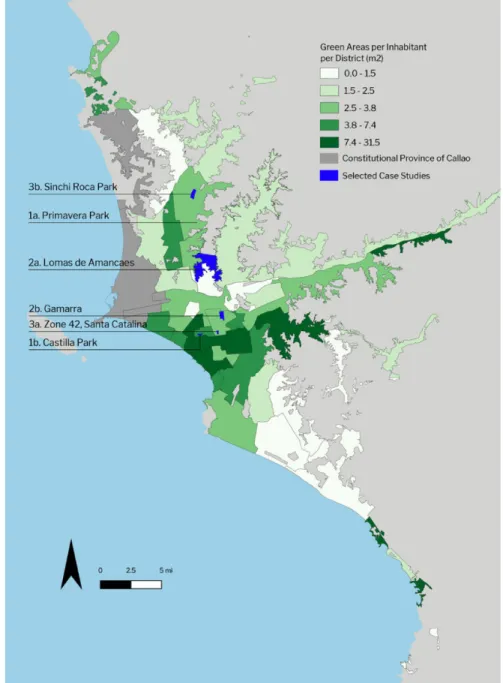

Figure 1 Green Area and Average Monthly Income Per District ... 9

Figure 2 Green Area and District Budget per District ... 9

Figure 3 Map of Green Area per Inhabitant per District and Case Studies Location ... 13

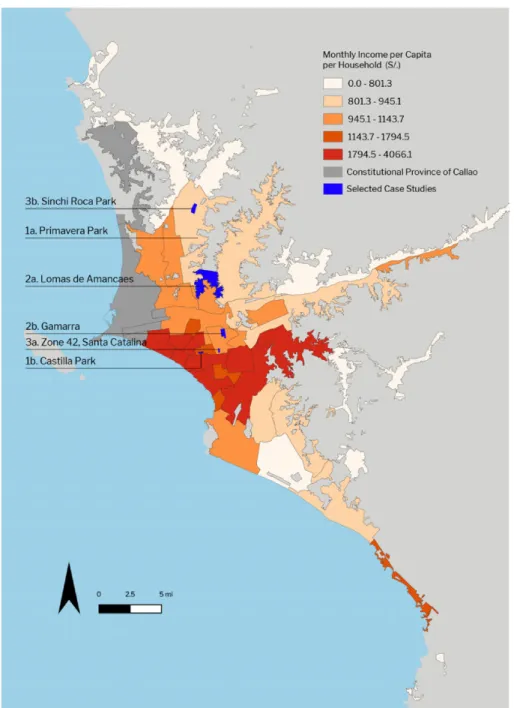

Figure 4 Map of Average Monthly Income per Capita per Household per District and Case Studies Location ... 14

Figure 5 Primavera Park before and after privatization ... 34

Figure 6 Primavera Park and its Surroundings ... 35

Figure 7 Neglected Area Next to the Football Court ... 36

Figure 8 Maps and Photos of Castilla Park ... 37

Figure 9 Ticket Booths Inside the Park ... 38

Figure 10 Lomas de Amancaes ... 41

Figure 11 Invasions on Lomas de Amancaes ... 42

Figure 12 Gamarra ... 45

Figure 13 Location of Gates in Zone 42, Santa Catalina ... 47

Figure 14 Entrance Gate in Santa Catalina ... 48

Figure 15 Sinchi Roca Zonal Club ... 50

Figure 16 Enclosed entrances in Sinchi Roca Park ... 51

Figure 17 Reasons why open public spaces are privatized ... 54

Figure 18 Google Street View in Av. El Retablo, Comas ... 56

Figure 19 Maps and photos of Manhattan Park ... 62

Figure 20 Advertisement of the new project, by the Municipality of Comas ... 63

Figure 21 Privatization, its consequences, and side effects ... 67

Table 1 Case studies selection ... 12

Table 2 Privatization types summary table ... 32

List of Abbreviations

ACR: Regional Conservation Area ANP: Protected Natural Areas

CADNEP: Citizens Activating and Defending Our Public Spaces INEI: National Institute of Statistics and Informatics

LOM: Organic Law of Municipalities LPSA: Lima’s Public Space Authority MML: Metropolitan Municipality of Lima

PAFLA: Environmental Protectors of the Flower and Lomas de Amancaes PLAM: Metropolitan Plan of Urban Development

RADTUS: Territorial Conditioning and Sustainable Urban Development Regulations RENAMU: National Registry of Municipalities

SERFOR: National Forest and Wildlife Service Serpar: Lima’s Park Services

Chapter 1

Introduction

Lima, the capital of Peru, has experienced an explosive growth that started in the 1940’s and was initially driven by internal migration. The following and continuous population expansion has led the city to develop and extend in a disorganized and unplanned way since then, occupying whatever land was available. Today, it contains almost 10 million people, one third of the total country’s population. Among other components of city planning, public space has been the one that has been deemphasized the most during this growth process. Nonetheless, it is undoubtedly one of the most important elements of cities, as it provides a collective space for encounter and gathering, supports and strengthens citizenship, and fosters diversity (Amin, 2008; Jacobs, 1961; Mitchell, 1995; Varna & Tiesdell, 2010; Young, 2011). In Lima, such as in other developing cities in the world, competing priorities such as boosting economic growth or providing basic services to vulnerable populations have overridden the creation and planning of public spaces.

Reports from 2019 show that 30.7% of the population in Lima is unsatisfied with the public spaces in the city (Lima Como Vamos, 2019a). Regarding parks and green areas, the percentage escalates to 50.9%, with an increasing trend during two consecutive years (37.8% in 2017 and 45.4% in 2018) (Lima Como Vamos, 2019b), showing that the perception of public space in the city is not improving. Moreover, there is a lack of comprehensive metrics that quantify public spaces in the city, which is due to two main reasons. First, because there is not a clear definition of the concept and how to measure it, and so it can be interpreted in different ways. Second, because data collection is a challenge, not only because of a lack of technical capacities, but also due to a fragmented governance of public spaces. There is not one designated institution that is responsible of managing and measuring public spaces. It is done at multiple levels and by different institutions, from the country, to the city, to the district scale, and there is not a unified and regulated process. Because of these reasons, the default metric used for public spaces in Lima and the rest of the country is green area per inhabitant, which only covers part of it.

According to the last reported metric from 2017, the city of Lima has 3.36 m2 of green area per inhabitant (Lima Como Vamos, 2019b). However, this number changes drastically when measuring it at a district level. The results show that there is a large difference between the district with the highest area of green space — San Isidro, with 22.09m2 per inhabitant — and the one with the lowest area — Pucusana, with 0.11m2 per inhabitant (SINIA, 2018). Furthermore, when looking at satisfaction of public spaces in people’s neighborhood, results differ according to socioeconomic sectors. 33.1% of the highest socioeconomic sectors (A/B) are satisfied, while in the lower socioeconomic sectors (D/E) this number decreases to 19.2% (Lima Como Vamos, 2019a). Although this can be due to different reasons, there seems to be a direct relationship with the quantity of green areas and both the income levels and concentration of public investment in each District Municipality (See Figure 1 Green Area and Average Monthly Income Per District and Figure 2 Green Area and District Budget per District)

Figure 1 Green Area and Average Monthly Income Per District1

Elaborated by author. Sources: SINIA (National System of Environmental Information, Ministry of the Environment), 2018 and INEI (National Institute of Statistics and Informatics), 2016.

Figure 2 Green Area and District Budget per District

1 Note: The district of Santa Maria has not been included in Figure 1 and 2, as it is an outlier. Although it does not have a high

number of total green area, it is a beach summertime destination located in the south of the city which has a permanent population of only 1675 people. Its low population causes that in the normalization of the indicator, the district has a disproportionately highest number of green areas per inhabitant.

Elaborated by author. Sources: SINIA, 2018 and Evaluation Management Report of Lima and Callao, Lima Como Vamos, 2017.

It is well known that open public spaces are not limited to green areas. At the same time, Lima is located in a desert and there are other types of spaces, such as paved ones, that provide many benefits to the population but do not include vegetation. Regarding its definition, there are four components that will be used in this thesis to define open public spaces: openness, ownership, accessibility, and function. These are spaces that are mostly open and have none or few building interventions, they are owned by the government, they are accessible without any restriction (physical, visual, economic, social, etc.), and are destined for a collective use, one that provides a space for citizens’ encounters and which fosters diversity and inclusion.

Open public spaces can be categorized in many ways: according to their physical form, location, scale (size and importance), function, degree of intervention (designed or potential), type of ground coverage, among others (Ludeña Urquizo, 2013). Even though there is not an official definition nor indicator that measures how much area of public spaces there are in the city, the closest proxy of green area per inhabitant and the perception surveys shed a light on the current condition and situation. There is no doubt that Lima has a deficit in open public spaces and that those that exist could be improved. The spatial distribution of these spaces raises the discussion around how public spaces are planned, created and maintained. Districts and areas with fewer resources have also lower access to public spaces, both in terms of quantity and quality. Certainly, there is an issue of spatial injustice at a city scale: as social and spatial dimensions of human life are deeply interrelated, the search and struggle for social justice is transferred over the territory, thus distributional inequalities create unjust geographies (Soja, 2010).

Moreover, in recent years, there have been commented cases about neighborhood groups that have protested against their district municipalities which, together with a private entity, were trying to convert their community public space into some other use that restricted their public access. Some of these escalated to the local media and have generated a conversation and discussion about the privatization of public spaces in our city. In recent years, multiple types — such as parks, plazas, boulevards, sports courts, streets, sidewalks, gardens, river banks, beaches, the coastal lomas, and the Costa Verde cliff — have become shopping centers, supermarkets, parking lots, private clubs, housing, amusement parks, synthetic grass courts, temporary markets or other uses. There is increasing attention about how privatization has been so far an almost invisible phenomenon at a city scale, and discussions have uncovered how, when there were no citizen collectives to defend public spaces, these have been ultimately privatized.

1.1

Research Question

I believe the phenomenon of privatization goes beyond a private entity taking over a park. Open public space gets privatized in the city in different ways. I define the term as the process where a space is taken away or dispossessed from the public to transform it into one that is destined for more private or restricted use. Privatization alters the definition of public space by transforming its openness if it is built on top of, its ownership if it is conceded to another private actor (even temporarily), its accessibility if it restricts the ability of people to enter, and its function if it alters in any way its condition of being a space that fosters inclusion, diversity, and interaction between all citizens. This means that on top of an inequitable distribution on the quantity and quality, plus a deficit in the total public space available in the city, some of those spaces are being privatized in different ways. At a city and neighborhood scale, this ultimately reduces the opportunity of citizens to access public spaces, and deepens the issue of social and spatial injustice even more.

In this context, the key question guiding this thesis is: under which conditions and in what ways are

open public spaces privatized? My research interest lies in exploring what are the different ways that

privatization happens in the city of Lima. I want to understand the motivations behind this, as well as the mechanisms of how this happens and its manifestations in the built environment. This research provides a

contribution to the discussion of planning and the defense of public spaces. First, by providing a framework to understand the privatization phenomenon, and uncovering how it happens through different ways. Although some opinion articles have addressed this topic and uncovered dispersed privatization cases, there are few academic and more thorough studies on it. Current literature alludes to some of the forms independently but there is no framework that encompasses and explains them as part of the same phenomenon.

The second contribution is that this thesis will help expose possible flaws in current planning and governance processes, both formal and informal, as well as create general awareness about how privatization takes place. So far, as this phenomenon has taken place dispersedly, it has been almost invisible. People who know about it are normally the ones that have experienced and suffered it, but it has not been widely discussed or exposed at the city scale. Understanding the conditions under which privatization happens in different ways can help identify spaces that could be under a possible threat of this phenomenon. At the same time, studying how in some cases the process was interrupted or reversed can inform what are the strategies to help prevent it.

Finally, I want to contrast the different types of privatization and evaluate how each can be more or less detrimental to public life, and expose who are the most affected by this process. Studying this phenomenon at a city-scale can also shed light on how it benefits the most powerful actors and sectors. My hypothesis is that in the end, this issue is related to the governance of public spaces: who has control and power, who is allowed to do what in the public sphere, and who is included in the decision-making processes. Definitely, what lies under the privatization of open public spaces is a lack of understanding of their importance in our city, as well as a lack of a comprehensive vision and public policy around what their role should be. In Lima and the rest of Peruvian cities, open public spaces should be planned, created and maintained to provide more safe spaces of interactions, encounters, and leisure, where active citizenship is encouraged, and where diversity is fostered.

1.2

Methodology

This thesis uses an inductive research methodology and qualitative methods to investigate the processes and ways that privatization takes place in the city of Lima. The research was carried out in two parts. The first aimed to explore and identify different cases of privatization in order to inform and formulate a typological framework of privatization. This exploratory research was done during July and August 2019, by identifying relevant literature, through semi-structured interviews to diverse stakeholders, and from reviewing documents such as academic papers, reports, media articles, and TV coverage. I then established different criteria that would help answer my research question, and identified three types that categorized privatization according to the rationale and process followed.

The second part was done through a case study analysis and aimed to understand the phenomenon more comprehensively. To do this, I selected a case study that embodies and illustrates each type. Through documents and media review, in-depth and semi-structured interviews, observations and photographic documentation, I collected qualitative information from each one. Interviews were made to diverse stakeholders, such as government institutions, residents, academics, and experts involved in the study of public spaces (Appendix 1). Through this research I collected diverse experiences and points of views, which have been synthetized in key findings and learnings that expose the motivations and processes of how privatization takes place, who are the actors involved, why it happens, and what impact and consequences it has.

Case Studies Selection

Three types of privatization of public spaces, with two variations each, were established in the typological framework. One case study was selected for each of the variations, which added up to six case studies. The selection process was based on five main criteria. As the research is applied to the city scale, the first criterion was to select case studies that were located geographically in different districts of the city. The second was to select districts that represent different income levels, municipal budgets, and quantity of green areas, in order to include a variety of socioeconomic factors in the analysis. The third criterion was to select cases of privatization that have taken place around a similar time frame. The fourth objective was to choose examples that were the most representative of the constructed typologies and which presented interesting elements to illustrate them. Finally, the fifth criterion was mainly logistical matters. Although many stakeholders involved in multiple case studies were contacted for this thesis, I finally selected the ones where I was able to get a response from and where I could establish a connection with the most stakeholders involved.

The six case studies are located in four different districts of Lima. A summary indicating each one and its corresponding typology and description is shown in Table 1. In addition, Figure 3 (Map of Green Area per Inhabitant per District) and Figure 4 (Map of Average Monthly Income per Capita per Household per District) show the specific geographic location of each of the case studies in the context of whole city.

Table 1 Case studies selection

Semi-structured interviews and site visits

A total of 17 semi-structured and in-depth interviews (with a duration of between one and two hours), and several short intercept interviews were conducted between December 2019 and January 2020 (Appendix 1). The objective was to learn from different perspectives and experiences from the various stakeholders involved in the case studies: from government authorities to evaluate the management perspective, to the residents who were supporting or affected by the privatization process. Additionally, semi-structured interviews were conducted to four planning experts involved in the study or promotion of public spaces. The interviews conducted to government officials were intended to gather information about the specific cases of privatization, as well as their planning practices, processes and challenges. Residents’ interviews

Typology Description Variation of

Typology Case Study Location Time Frame

1.

Concession for Development

Public space is rented to private entities in the form of concessions with the excuse of bringing development and improvement.

1a. Transformation for

Redevelopment Primavera Park Comas 2017 – Today

1b. Partial Transfer for

Commercial Uses Castilla Park Lince 2016 – Today

2.

Appropriation for Livelihood

Public space is informally appropriated to fulfill a basic need such as housing or a productive activity.

2a. Invasion for

Housing Lomas de Amancaes Rímac 2013 – Today 2b. Occupation for

Productive Activity Gamarra La Victoria ~2015 – 2019

3.

Enclosure for Control

Public space is enclosed and its access is restricted in order to provide safety or facilitate its

management.

3a. Fences for security Zone 42, Santa Catalina La Victoria 1995 – Today

3b. Entry fee for

aimed to learn about their experience in each case, mostly in their fight against privatization, and their current challenges and initiatives. Each of the privatized public space was visited in order to make on the ground observations, document the sites through photographs, and conduct short interviews to visitors and local managers to collect their different perspectives.

The interviews aimed to learn about each of the six case studies, but additional interviews were made regarding one other privatization case, in order to complement and help inform the research. This was Parque Manhattan in Comas, a case where the privatization process was stopped. It was included in the interviews to learn from the process and motivations behind, and also to understand the mechanisms that were implemented to prevent privatization. It was also the only case where I was able to conduct an interview with the private stakeholder involved in the process.

Figure 3 Map of Green Area per Inhabitant per District and Case Studies Location

Map elaborated by author. Source: SINIA (National System of Environmental Information, Ministry of the Environment), 2018.

Figure 4 Map of Average Monthly Income per Capita per Household per District and Case Studies Location

Limitations

The methodology described here aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the phenomenon of privatization in Lima. Nonetheless, this research presents some limitations. The selected case studies, located in four districts, do not cover the whole city’s geographic territory. This thesis tries to comprise governance and planning approaches that can be generalized to Lima, but not all the district municipalities have been included in the research. Moreover, most of the residents who were interviewed were opposed to the privatization of public spaces. Thus, the first-hand experience included in this thesis has been collected from people opposing privatization and authorities. It was very difficult and unsafe to contact directly and interview residents or other actors who were privatizing the public space, as some of the cases were connected to criminal activity. This is the reason why these stakeholders’ perspectives have been gathered from secondary sources of information such as reports, testimonies, news coverage and other investigations. Furthermore, this thesis does not include any quantitative approach that exposes how large the issue of privatization is, and how much area has been privatized according to the different forms of privatization. It is difficult to determine if this phenomenon is substantially decreasing the amount of open public spaces at a city scale, and also evaluate how it has changed throughout time. The challenge, as explained before, is a data gathering issue but also a definition problem. This thesis provides a definition for public spaces and for privatization, in addition to identifying different typologies. Future work could focus on how to quantify the total amount of open public spaces in the city and operationalize privatization, in order to evaluate it in a quantitative way. Finally, I acknowledge that processes to recuperate open public spaces are also taking place in the city. This research does not focus on them, unless they are connected to the selected case studies, as the goal is to uncover privatization processes to inform how they can be stopped and prevented. Future work could also concentrate on evaluating if there are more privatization or recuperation processes occurring in Lima.

Chapter 2

Literature Review

2.1

Public Spaces Theories

Definitions of Public Space

Public space is a complex concept, that can include many dimensions and can be defined in different ways. It is a concept that but encapsulates a variety of ideal qualities that provides a lens of analysis to examine the intersection and interaction between urban life and concrete open spaces. One way of defining it is by taking the legal ownership of the space. Under this lens, public space exists when the land property belongs to a public institution and thus is regulated and controlled by it (Borja, 2001). The definition can also be tied to the concepts of inclusivity and access. Akkar (2005) mentions that the level of inclusivity of a space can be defined by four qualities of access. These can happen at different levels, creating a continuum between an inclusive public space and its opposite, an exclusive private space. The first quality is physical access. The second is social or symbolic access, which considers if the activities and discussions that take place are accessible to all. This also evaluates if there are any elements — physical, social or regulatory — that suggest if someone is welcome or not to the space. The third is access to information, and examines if information about the space, such as its development, is available to all. The forth is access to resources, which refers to the ability of citizens to have a public arena where they can express their claims. Access is tied to the space’s ownership but is also established by its management. Thus, publicness and inclusivity can be constantly formulated and reformulated according to who sets the rules and how the space is controlled (Németh, 2009).

Other scholars define public spaces by considering the functionality or use of the space, and by the way the physical space is occupied (Grant & Curran, 2007; Purcell, 2002). A public space exists where social and political activities take place, it is defined by the ‘lived’ sense and not just by the legal aspect or ownership (Low & Smith, 2006; Marcuse, 2005; Worpole & Knox, 2007). In addition to accessibility and property, Kohn (2004) adds the component of intersubjectivity, which refers to how a public space fosters communication and interaction. Another variation considers how representative of the collective, rather than the individual or private, a space is, and if it is socially inclusive and neutral (Tiesdell & Oc, 1998). Moreover, Ludeña (2013) considers that public spaces are those that have an unrestricted, free, public use, which can be individual or collective. In addition, the use can be existing or potential, which means that a space that has not yet been designed or intervened, but that is open and government-owned, can be considered as a public space.

Furthermore, some scholars have gone beyond the definition and have created a set of indicators to try to measure publicness and compare different sites, including dimensions of control, functionality, and physical characteristics. Akkar and Oya (2015) elaborate a model to assess publicness considering four dimensions: design, management, control, and use of the space. Moreover, Németh and Schmidt (2007) develop an index to quantify social and behavioral control in publicly accessible urban spaces. They measured 20 different variables - half which indicated control and a half which indicated open use of the space - classified into four categories: laws and rules, surveillance and policing, design and image, and access and territoriality. Similarly, Varna and Tiesdell (2010) present a model that measures five dimensions of the

public space: ownership, which refers to the legal status of the space; control, which alludes to explicit control presence and policing; civility, which refers to how the public place is managed and maintained; physical configuration, which determines if the public can easily reach and enter the place; and animation, which measures how much the design of the space is aligned or responds to human needs in a public space.

The Role of Public Space

Public spaces play a central role in cities and democratic societies as they are neutral spaces that host encounters between all citizens. They are places for civic inculcation and political participation and where people with diverse points of view can coexist (Amin, 2008; Mitchell, 1995; Young, 2011). Jacobs (1961) highlights their social purpose and their centrality to the life of cities, and mentions how in public spaces individual actors come together in an aggregated whole. Similarly, Borja (2003) attributes public spaces as the arena for the declaration of an active citizenship and highlights its importance to establish a new urban life amidst the current negative vision of the city as a space full of social problems.

More recently, Alvares and Barbosa (2018) analyze diverse case studies of public spaces in Brasil to illustrate how the public engages in both individual and collective manifestations, symbolically appropriating the space. Their study seeks to show and reflect on how in public spaces all differences can be seen and dealt, and where individuals can engage in a ‘vita activa’. Furthermore, Varna and Tiesdell (2010) present three types of value that public space brings to the city. The first is political/democratic: it offers a stage for political representation, is neutral open to all, and is inclusive and pluralist. The second is social: it fosters social integration, information exchange, personal development, social learning and the development of tolerance. The last is symbolic: it is representative of the collective and sociability rather than individuality and privacy.

Evidently, the concept of public space is complex and cannot be described or contained in one single category. That is the reason why the literature normally defines it with multiple and interrelated characteristics. Kohn (2004) proposes that it should be treated as a cluster concept, which involves defining different possible criteria. The concept of public space might not represent a concrete reality, as the totality of its ideal qualities might not be achieved in practice. Nonetheless, these are valuable to help determine the degree to which the essence of these spaces is reduced from its ideal state (Tiesdell & Oc, 1998), and to help inform the type of cities we want to create.

Taking in account the described definitions and dimensions, this thesis defines public spaces considering four components: openness, ownership, accessibility, and function. Public spaces are those that are mostly open and have none or few building interventions, they are owned by the government, they are accessible without any restriction (physical, visual, economic, social, etc.), and are destined for a collective use one that provides a space for citizens’ encounters and which fosters diversity and inclusion, which means that its purpose is to serve to the whole city and not to specific groups.

2.2

Privatization Theories

Definition of Privatization

The word ‘private’ is commonly defined in relationship and contrast with the concept of ‘public’. The private sphere refers to the individualization of formerly social practices and is placed in the opposite spectrum of the public sphere (Arendt, 1958; Corcoran, 2012; Cheshire et al., 2018). The dichotomy between the public and the private can be attributed to the legal ownership and property of the space: the public is what belongs to the government and the private is what belongs to an individual or business

(Díaz-Albertini F., 2016). Thus, privatization can be a transfer in ownership. It is also related to the concept of exclusion, which can be explicit and justified by norms, political or proprietary arrangements; or implicit, based on social rules and relationships (Kim, 1987). Moreover, privatization is also referred to as a process where the growth of the private sector or entity is placed at the expense of the public — it is a retraction of the public sphere. Starr (1988, p. 3) declares that “privatization can also signify another kind of withdrawal from the whole to the part: an appropriation by an individual or a particular group of some good formerly available to the entire public or community. Like the withdrawal of involvement, privatization in the sense of private appropriation has obvious implications for the distribution of welfare”.

Taking these approaches, in this thesis I define privatization as the process by which government-owned open public spaces are dispossessed or taken away from the general public and citizens, and assigned a new type of ownership associated with an external non-governmental actor such as an individual, a group of individuals, or private entity. Thus, privatization is a process of transformation that also involves its access, function, and physical space. There is a decrease in access which can be physical or symbolic, together with a change in use that focuses not in the collective and public, but in the individual and private. This means that the actors who use the space or can potentially use it is altered and reduced. Finally, through the privatization process there is also a physical transformation of the space, in which its openness is restricted and diminished, and where exclusion is translated into the built environment.

Furthermore, the process of privatization can be attributed and rooted to different reasons. These may happen simultaneously or independently, and they are essential to understand why this phenomenon takes place. The first is the implementation and glorification of neoliberal economic models. Governance structures have shifted from a managerial model to an entrepreneurial model, where planning is led by the market and capital (Harvey, 2001). Alvares and Barbosa (2018) mention that while the public sphere is connected to a cultural production and citizen construction dimension, the private sphere is driven by market needs and demands, and thus associated uniquely to an economic dimension. Public interventions in urban governance have weakened, and cities have started to compete with each other to attract private investments in the form of real estate and private developments. Neoliberal policies have direct implications on public spaces, creating tensions between the public nature and the interest of encouraging capital accumulation based on the commoditization of public urban land (Kohn, 2004; Lozada Acosta, 2018; Narváez Muelas, 2019). Cities have created and encouraged new spaces of consumption, where individualization and fragmentation are fostered (de Mattos, 2009). In addition, Kohn (2004, p. 12) suggests that while privatization processes (such as a town square being replaced by a commercial space or theme park) could reflect a change in consumers’ preferences, these preferences might instead be driven and defined by the imposed economic structures.

A second reason that motivates privatization is efficiency, which happens when public authorities do not have the means or capacities to sustain public spaces. Efficiency can be related to the financing, development, and/or management of the public space. In cases where public authorities do not have the means to achieve any of these goals, partnering and collaborating with private entities appear as an adequate solution (De Magalhães & Freire Trigo, 2017; Grant & Curran, 2007). Evidently, private sector involvement can lead to an increase in the financial budget, but can at the same time constrain the open access to the public space.

Van Melik et al. (2009, p. 208) study this hypothesis by analyzing four privately redeveloped squares in different Dutch cities. Although they conclude that public access in these cases is not necessarily restricted, they acknowledge that this outcome cannot be generalized, since Netherlands' public spaces policies are strict and control that they should be 'used by and accessible to all'. Furthermore, De Magalhães & Freire Trigo (2017) study the private management of public spaces in the city of London and conclude that as long as there are clear and transparent accountability and decision-making processes that involve multiple stakeholders, the results do not necessarily affect negatively the level of publicness of the space. However,

they recognize that these spaces eventually privilege the involved constituencies’ interests, such as local residents, businesses, and landowners. Nonetheless, these processes might not have the same results in Latin America, as some studies indicate that private management does affect access and control to public spaces. For example, Narváez-Muelas (2019) study a case in Cali, Colombia, that took place in the 1990’s, where a private entity privatized a large green open public space in the city after building a new housing development adjacent to it. The authors highlight how the transferring rights of development projects play a key role in privatization processes.

A third reason why privatization takes place is an urgency for safety and control, which can lead to segregation and exclusion. Overly regulation in response to crime, disorder and insecurity can be a way of privatizing as it controls who is allowed to access a space, symbolically or explicitly (Barker, 2016; Bensús, 2012; Low et al., 2005). This is demonstrated in the new residential models such as private enclaves, gated communities, common interest housing developments, and private streets and roads. All these aim to provide an increase of perceived safety to a group of people who share a common space, but also delimit an area where they who share similar lifestyles, economic status and/or identities can differentiate from others (Grant & Curran, 2007; Low, 2003). The exclusion of determined groups also showcases the desire to hide from sources of discomfort and other unpleasant characteristics commonly present in the city that are consequences of a social system (Kohn, 2004). In Latin America the mechanisms to achieve these safety measures might not be institutionalized and formal, and many times take place after the neighborhood is developed and consolidated. These processes can demonstrate how a specific group is able to influence the local management of public spaces and change the built environment to their benefit (Palma, 2014). Moreover, privatization through control are implemented across all socio-economic sectors. Caldeira (2007) studies how, in Sao Paolo, processes of fortification that create monitored borders appear throughout the city, and end up segregating and promoting a sense of intolerance and fear between different social, economic and geographic sectors.

A fourth reason is clientelism and patrimonialism, which mostly appears in Latin America and responds to the political systems in place. The first is when authorities act on behalf of a specific sector of the population with an underlying motivation of getting votes and political support from them (Díaz-Albertini F., 2016; Velarde Herz, 2017). This can result in interventions in the physical space or in regulations that can benefit a specific sector of the population over others. At the same time, it creates short-term impact governance practices, as the interventions mostly last for as long as the authority is in charge. Finally, patrimonialism refers to the private appropriation of the public position, when authorities act or make a public intervention in the city for their own benefit.

Other Forms of Privatization

Although this thesis focuses in the privatization of open public spaces that are owned by the government, existing literature on this topic includes other manifestations of privatization. One type are the privately-owned public spaces. These refer to ones that although are a private entity’s property, they constitute of public access and thus are considered public. This can apply, for example, to an open plaza in the entrance of a shopping mall or an office building. A city where many of this type of spaces exist is New York City. In 1961, a new zoning resolution was established to help incorporate new public spaces to the city. It allowed new project developments to gain floor area bonuses in exchange of including a public space within their property, a policy that has been replicated in other cities to achieve the same goal. Although new open spaces have been added to the city, some studies suggest that the management regulations can limit their level of publicness (Kayden, 2000; Kiefer, 2001). Thus, if a private party owns a public space, it is in charge of determining the rules of who, when and how it can be used, possibly asserting exclusion through control (Armborst et al., 2017).

Moreover, privately-owned public spaces can also be spaces which, although are privately owned, have been appropriated by citizens as a public space. This might happen due to the neglect or lack of control established by the property owner. Mitchell (1995) studies a specific case where this took place in California: the People’s Park. The park was gained by the University of California (UC) through eminent domain to build students' dormitories in 1967. Nonetheless, UC did not move forward with the project, and the park was intervened, occupied, and used by local residents and homeless people for almost 24 years. After this time, the university decided to reclaim and redevelop it to complete its original use, displacing users and changing the character and use of the park. Although the legal property owner was the university, this process might still be considered some form of privatization.

Other ways of privatization and exclusion of public spaces are achieved by using specific regulations or design elements. Armborst et al. (2017) provide an extensive catalog revealing different mechanisms used in the United States by which private owners and authorities include and exclude people from public spaces. Likewise, another form of privatization is when local authorities regulate and commodify the surfaces of urban elements, such as walls, trash cans, electric wiring boxes, and others, for creative and cultural production, but with an economic interest behind (Treger, 2011).

Furthermore, existing research studies how public space is privately used by citizens for their individual benefit. Bruno et al. (2013) document different ways of how this happens through physical interventions in Seoul. They argue that, as citizens, we all use public spaces for our private benefit on different levels, depending on the intensity and how much time we spend there. How we privately occupy the space is a constant negotiation with the community that surrounds it. They state that although many times these appropriations are done illegally, these occupations should be seen as an opportunity more than a problem that needs to be completely eradicated. Similarly, Kamalipour and Peimani (2019) study street vending in different cities in Ecuador, Colombia, Thailand, and India. However, they declare that these informal collaborations can convert into a form of monopoly and collective privatization of public space.

Privatization of Public Spaces in Lima, Peru

There is an emergent body of literature that analyzes specific aspects of the privatization of public spaces in the city of Lima. Some scholars emphasize how the issue of fear of the “other” — those dissimilar to one self — and feeling of insecurity has generated the privatization of public spaces, process that can be led both by municipalities and citizens (La Rosa González, 2014; Takano & Tokeshi, 2007). Under this lens, Plöger (2006) studies and proposes a typology of distinct residential enclaves that exist in the city of Lima, categorized by the size, location, socio-economic status, quantity of amenities and services, and moment of privatization. He argues that this process includes the appropriation, control, and fortification of public spaces, and that these developments normally emerge from the surrounding residents.

Similarly, Díaz-Albertini (2016) presents three ways in which privatization takes place in Lima and argues that this process is mainly a response to the feeling of insecurity in the city. They are called the fief, the region, and the fair, and are grouped and distinguished exclusively according to the actors who privatize the spaces. The study does not focus solely in open public spaces but also considers privately-owned spaces. The first is executed legally by the government, the second is done illegally by citizens, and the third is the creation of shopping malls by private companies. He considers that the last ones consist in the new private-public spaces, as an increasing number of people feel safer and thus prefer to spend their time there instead of outside.

Moreover, other research highlights specific case studies where privatization of public spaces took place or almost happened. Lozada (2018) has presented two cases where she analyzes how existing planning regulations, which are ruled by predominant logics of capital investment promotion, influence the course

and outcome of public spaces. The role of citizen movements plays an important part in preventing privatization in a system that privileges the private sector and where public participation is not guaranteed. Moreover, there is a journalism report presented by Convoca.pe (Pérez Pinto, 2019) that investigates and quantifies the total area of public spaces in seven districts Lima that have been given in concession to private entities in the last 25 years. It finds that the total area is 569,700.65m2, which is equivalent to 79 soccer fields. Finally, ex-congresswoman Indira Huilca, together with CADNEP (Citizens Activating and Defending Our Public Spaces) (2019) — a citizen organization that promotes the protection of public spaces in Lima — have created a report that describes different cases of privatization of public spaces in the city and present different mechanisms and actionable recommendations that citizens or collectives can use to defend the public spaces in their communities.

2.3

Metropolitan Governance Theories

Governance Structures and Models

Metropolitan governance is the means by which the state regains control over the territory (Xu & Yeh, 2017) and acts as a framework for economic development, planning, and financing (Ortiz & Kamiya, 2017). Although different terms are applied to the approaches and practices, there is some consensus that it is “determined by the nature of the governance structures with relation to the levels of fragmentation or consolidation, the degree and level of control over urban functions, and the degree of formality or informality in the coordination of metropolitan area units” (Gómez-Alvarez et al., 2017).

Metropolitan areas can follow different governing structures and organizations, and these vary according to national and historical, cultural and political contexts (Birch, 2017). Bird and Slack (2007) have developed four models that describe different ways in which local governance and finance are structured: one-tier, two-tier, voluntary cooperation and special districts. The first takes place when there is a single local government that is in charge of providing all metropolitan services. In the second, there is an upper tier governing body that includes the larger metropolitan territory, and a lower tier or local municipalities that govern smaller jurisdictions, which are in charge of providing services in that specific area. In the third model, there is no official institution that governs the whole metropolitan area, but the existing units of the local governments cooperate voluntarily. The fourth model, special districts, is created for a single purpose, such as providing a service to multiple municipalities. The authors argue that all of them have pros and cons, and that choosing the best model highly depends on the specific context and challenges. They conclude that good government requires not only publicly elected and responsible mayors and councils, but also financial independence.

In addition, Sellers & Hoffmann-Martinot (2008) propose that governance institutions in metropolitan areas can be classified according to different dimensions. The first is spatial coverage, or the total area the jurisdiction is responsible for, which can be a fraction, the majority, or the entire metropolitan area. The second is institutional thickness, which refers to how much integration and collaboration exists across institutions, and ranges between inter-community co-operation and Metropolitan town. The third dimension is democratic intensity, which is determined by the degree of citizens’ role in the appointment and control of metropolitan authorities. The final dimension is the centrality and relationship between the metropolitan institution and the higher levels of policymaking. Institutions can be evaluated according to their level (low, moderate, high) in each dimension.

Moreover, the different adopted governance models and the way they are executed has a direct influence in the ability of local institutions to deliver public services. The lack of a metropolitan scale management can lead to urbanization and environmental problems, fragmentation of service delivery, traffic congestion, and other inefficiencies such as under-utilization of land (Ahrend et al., 2017; Andersson, 2017).

Additionally, the changing landscapes of diverse administrative structures can exacerbate local problems and challenges. It also misses opportunities that could help achieve valuable development across sectors, such as transportation, open space preservation, and equitable growth (Xu & Yeh, 2017).

In order to make urban places productive, there needs to be a multi-tiered, multi-stakeholder governance, which should be guided by decentralization principles (Birch, 2017). This means that there is a transfer of powers, from central or higher levels to local or lower levels of governance, which include smaller legally delimited geographic areas (Yuliani, 2004). Moreover, decentralization can take two forms: deconcentration and devolution. The first refers to an administrative decentralization and takes place when the local administration still depends and is accountable to the centralized government. Both have the same institutional identity and normally the person in charge of the local level is appointed by the higher level of government. Devolution refers to a shift of power from the central government to the local government. This creates semi-autonomous institutions whose authorities are normally elected by citizens (Ortiz & Kamiya, 2017; Yuliani, 2004; Zegras, 2017).

The Challenges of Effective Metropolitan Governance

Decentralization has been a world trend since the late 20th century. Since 1992, around 80% of the countries in the world started to experiment some form of decentralization (Faguet, 2012). In Latin America, after the 1980’s, when most authoritarian presidential regimes ended, the new democratic governments introduced reforms that transferred powers and financial capacities from the central to local governments. Nonetheless, the region is still highly centralized in the political, territorial and economic aspect. This is partly due because of the concentration of population in the metropolises and the social and territorial imbalances (Rosales & Valencia Carmona, 2008). Although decentralization aims to achieve institutional autonomy and better responses to local needs, in the Latin American region there have been many challenges in its implementation.

The first challenge is institutional fragmentation due to municipal heterogeneity. There is a geopolitical and horizontal fragmentation as each local government focuses in its own jurisdiction, and tries to adapt and respond to their local constituency. At the same time, there is vertical fragmentation with overlapping higher levels of government such as federal, state and local agencies (Feiock, 2009). This fragmentation is sometimes called atomization and is present at some degree in all of Latin America. Peru, for example, has more than 2000 provincial and district municipalities (Rosales & Valencia Carmona, 2008). A second challenge is the political aspect of governance. As local leaders are chosen by citizens, and in some areas can be reelected, there is a need of authorities to seek political support by answering to needs and demands of specific groups. Hence, most of the time final decisions depend on the political willingness of actors (Ahrend et al., 2017).

A third issue in the implementation of effective metropolitan governance is the level of limited financial autonomy and capacity. If local autonomy is not attached to the financial aspect, then policies and projects are much difficult to implement. Who has the money, who can spend it, where it comes from, and where it can be spent are crucial elements that determine how efficiently institutions work, their capacity to deliver public services and needs, and their ability to respond to longer-term issues (Bird & Slack, 2007; Gómez-Alvarez et al. 2017). Although the most important source of income for municipalities is property tax, their capacity to collect taxes is weak, and most of the time they are based on outdated property registers. In addition, most of the time these institutions do not have the power to determine, change or increase taxation, and they depend on the central government to get funds transfers. Furthermore, as territories are diverse and many times socio-economically segregated, there is a large contrast and unequal distribution of municipal wealth (Rosales & Valencia Carmona, 2008).

A fourth challenge is accessing and maintaining human resources. In most countries of Latin America, including Peru, there is not a civil service career or they are not well organized. In addition, most higher-level staff are chosen by the current administration, and so personnel is highly affected by political changes. The lack of incentives and the low level of value attributed to pursuing a public servant career, together with a very high staff rotation result in inefficient management.

Incorporating civic participation in governance processes is the fifth challenge. This can be due to the mentioned issues of having inadequate financial assets or staff to manage those processes. Nonetheless, it can also take place because these processes are not incorporated into national policies, or when they are, they are poorly adapted at the local scale. Another reason might be that institutions do not have the management capacity to reach and mobilize local communities. Moreover, as metropolises continue to grow, they also include very diverse public interests, and it is harder to respond to all of them. Still, some countries have created initiatives and mechanisms to better incorporate public participation and consultation, such as Bolivia, Venezuela, Peru, and Uruguay (Rosales & Valencia Carmona, 2008). Finally, another challenge is that there are none or poorly implemented official mechanisms to hold authorities accountable. Many times, these are created by external governmental actors such as citizens groups, NGOs, or private entities, but depend on different factors. Taylor-Robinson (2010) studies the capacity of the public to achieve government accountability, focusing in Honduras but generalizing to the Latin American context. She analyzes how officials respond differently to rich and poor constituencies, and their behavior determines the ability of people to hold them accountable. Accountability is harder to achieve for the poor because they lack the resources that middle class and elite groups have, such as connections, education and access to information. Institutions make it hard and costly for poor people to punish elected officials, thus this is not a highly pursued path. The author determines that the best option for this group is to look for clientelistic representation, so that authorities respond to their needs in exchange of political support.

Although several challenges to create effective decentralized governance structures have been presented, there are still successful cases. Tendler (1997) uncovers good governance examples in Brazil, focusing on the Northeast region and poorest one in the country. She challenges the existing larger body of literature that concentrates on critiquing bad government practices and solely proposes generic advice. Across her four case studies, she finds that civil servants were autonomous, very dedicated to their jobs, and carried out a variety of tasks that sometimes exceed their usual activities — all in order to better respond to citizens’ needs. The state government also plays an important role. It implemented an effective communication campaign that informed citizens about their rights and how public services worked. This incentivized people to demand a response to their needs and transparent processes, which helped hold authorities accountable. Moreover, Faguet (2012) focuses on the decentralization reforms in Bolivia and studies two cases between 1987 and 2009. He finds that while one local government was very responsive to local needs, the other was corrupt and unresponsive. He investigates the causes of these different responses that take place under the same political reform. The author concludes that the governance accountability and effectiveness depend on the local social, economic, and political dynamics, which in turn are defined by three institutional relationships: voting (individual voters), lobbying (private firms), and civil society (collectives). Finally, McNulty (2011) studies specific governance practices in eight different regions of Peru, including Lima. She finds that although they follow the same regulations, the ones that implemented successful participatory practices and have better governance are regions with a strong leadership and an active and organized civil society that collaborates with the local government.

The described successful governance cases thus emphasize how each local institution was able to adapt to the local context and respond autonomously to the public they were serving, incorporating them in the discussion and decision-making process.

Chapter 3

Context

3.1

Lima’s Governance Structure and Challenges

Lima, located in the coastal desert of Peru and in the geographic center in the north-south dimension, has today a population of 10 million people in a country of almost 30 million. The capital city has an extension of 2,819 km2 and a population density of 3.33 habitants per km2. Lima’s governance structure is characterized for being a two-tier model, according to the types of metropolitan governance defined by Bird and Slack (2007). This means that there is an upper tier corresponding to a Metropolitan Government, led by the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima (MML), and a second tier corresponding to the local governments, led by the district municipalities. The city is formed by 43 districts in total, all with different sizes, population, and socio-demographic characteristics. In addition, the Constitutional Province of Callao, composed of seven more districts, is located adjacent to Lima. Although both are part of the same geographic territory, they are independent provinces and have different administrations.

The current Constitution, created in 1993, provided municipalities with higher levels of autonomy, and established the co-existence of local governments and a metropolitan structure. However, today the two tiers are not integrated functionally, as many roles overlap. In addition, there are 19 ministries at the national level that have roles that might focus on similar topics (e.g. culture, education, etc.) but that and are treated as isolated functions within their own sector. There is very little vertical and horizontal spillovers and collaboration across all government levels. In Lima, at the municipal level each institution governs on its own delimited district, developing a fragmented administration of the territory.

Furthermore, according to Article 195 of the Constitution, the public function of the district municipalities is to promote development and neighborhood economies, and provide public services, using national plans and policies to guide their processes. However, Peru does not have a general law regarding urban development nor an urban code that guides city planning. The only instrument we have at the national level is the Territorial Conditioning and Sustainable Urban Development Regulations (RADTUS). This document, developed by the Ministry of Housing and approved in 2016, establishes the city planning instruments to be used by local institutions. Nonetheless, it only presents the regulation codes and legal framework, and does not include any tools, design or planning guidelines that translate the framework into actual plans. Furthermore, Lima does not currently have a Metropolitan Development Plan for the whole city that acts as an urban development guide for each district. The last approved plan for Lima was the one created in 1990, designed to last until 2010 and using the 1979 Constitution, and is now obsolete.

The Metropolitan Municipality of Lima overviews scattered planning projects that affect larger areas of the city and normally involve multiple districts. Some examples are transportation infrastructure developments or design transformations on main streets that cross different jurisdictions (e.g. implementing a bike lane or changing the street design). Moreover, although district municipalities are in charge of creating urban development plans for their districts and establishing zoning regulations, the MML needs to approve those changes. Hence, the two-tier model creates a very bureaucratic process of approvals that not only take a long time to implement, but are also very political processes. In order for projects of these types to move forward, usually the district’s mayor and the Lima’s mayor have to have a good relationship, such as being