Commercialization of a Masonry Tool Designed in a Senior-Capstone Class Through a Licensing Agreement

by Hannah R. Rudoltz MASSACHUSETS INSTITUTE OFTECHNOLOGY

SEP 13 2018

LIBRARIES

ARCHIVES

Submitted to theDepartment of Mechanical Engineering

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering

at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

June 2018

2018 Hannah R. Rudoltz. All rights reserved.

Signature redacted

Signature of Author:

I)

Department of Mechanical Engineering

/ * May 18,2018

signature

reaactea

Certified by:

Dr. Warren Seering Weber-Shaughness ProfessorZ Mechanical Engineering

Signature redacted

Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:~Rohit Karnik Professor of Mechanical Engineering Undergraduate Officer

Commercialization of a Masonry Tool Designed in a Senior-Capstone Class Through a Licensing Agreement

by

Hannah R. Rudoltz

Submitted to the Department of Mechanical Engineering on May 18, 2018 in Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements for the Degree of

Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering

ABSTRACT

Many seemingly viable products are designed and built in MIT Mechanical Engineering's senior capstone design class, 2.009, but a small fraction make it to real markets. The 2017 2.009 Orange Team is commercializing their product through the company Rhino Tools and Equipment (RTE). The product, a rotary hammer attachment that guides the chisel bit as it moves within a mortar joint, was designed with the aim of improving the repointing work done by masons on brick exteriors.

Given the real constraints on a team of soon-to-be graduating students and analysis of the market and the product, a licensing business model was chosen. The licensing business model is heavily reliant on intellectual property. Thus, an extensive prior art search was carried out to determine the product's novelty. By this analysis the product is patentable. Cash flows were projected to determine a fair allocation of economic benefit in a licensing agreement; RTE should expect to receive about 4.5% royalty on revenue.

Moving forward, RTE should pursue funding to complete the patent process as well as a pilot program with masons, and continue to develop its connections within the tool industry.

Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Warren Seering

Acknowledgments:

Thank you to every member of the 2017 2.009 Orange Team, who made the capstone of my senior year in Course 2 so memorable, and made this work possible.

And to Professor Warren Seering and Peter Nielsen, and the other Orange Team mentors who so enthusiastically encouraged and supported the team as we pursued this design.

Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 5 Table of Contents 7 List of Figures 8 List of Tables 9 1. Introduction 11 1.1 The Problem 11

1.2 The Design Process 11

1.3 The Alpha Prototype 14

1.4 Moving on After Final Presentations 15

2. Choosing a Business Model 17

2.1 What is a Business Model? 17

2.2 Business Models for New Ventures 18

2.3 Business Models Considered for the Rhino Tool Attachment 19

3. Intellectual Property 23

3.1 Utility 23

3.2 Novelty 24

3.3 Non-Obviousness 36

3.4 Disclosure 37

4. Creating a Licensing Agreement 41

4.1 Potential Partner Companies 41

4.2 Determining Royalty Rate 42

List of Figures

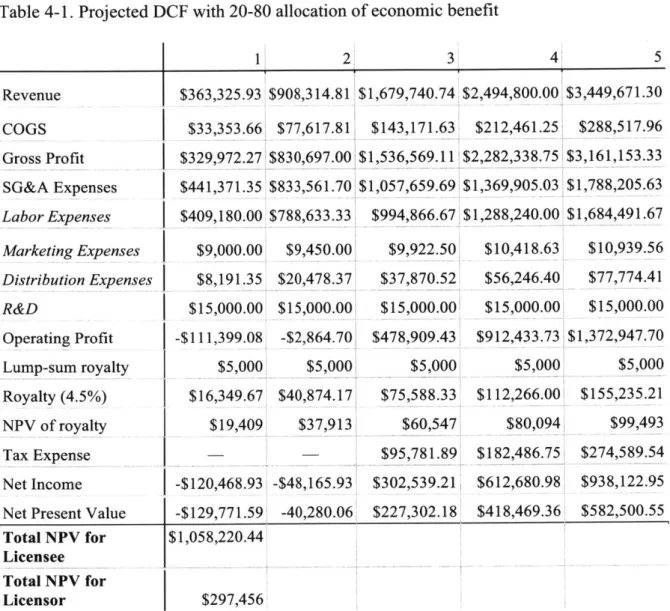

Figure 1-1: Figure 1-2: Figure 3-1: Figure 3-2:

First iteration of Rhino attachment with a single-sided device One-sided rotating alpha prototype

US Patent 5058275, "Chisel"

German Patent Specification No. DE 3312019

13 14 28 29

List of Tables

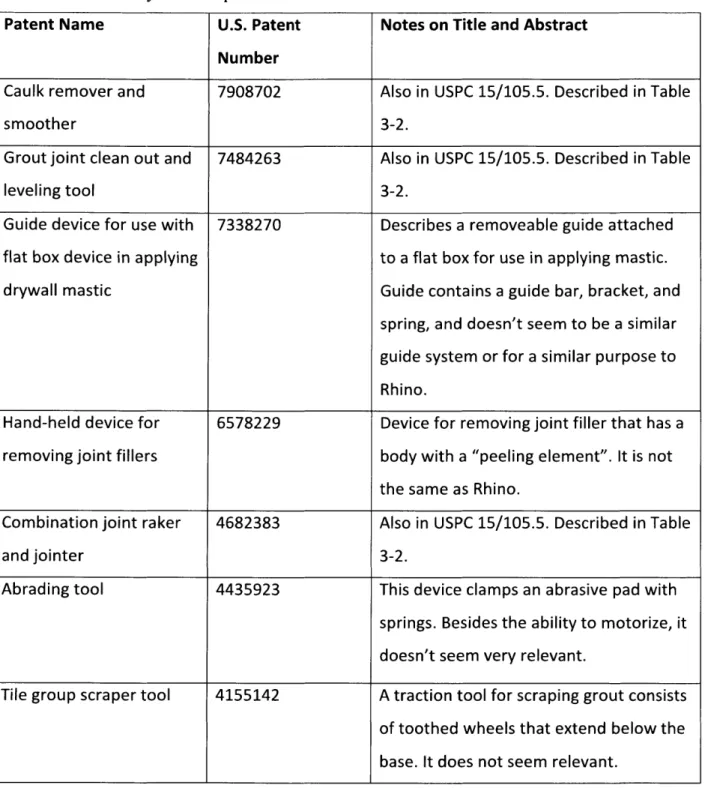

TABLE 3-1: TABLE 3-2: TABLE 3-3: TABLE 4-1:

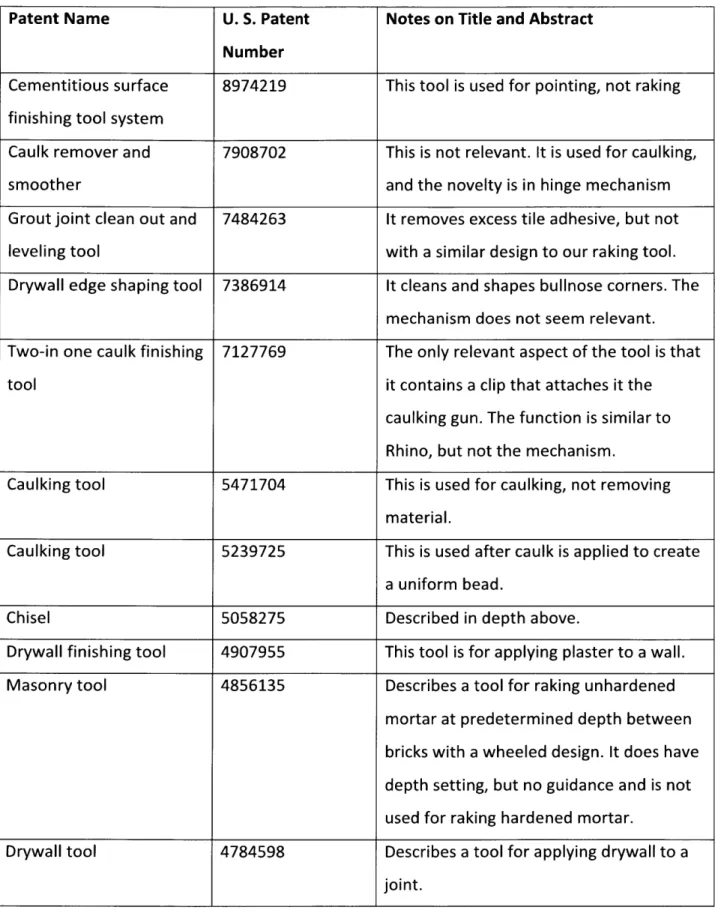

Preliminary prior art search results

Potentially relevant patents from USPC 15/105.5 Potentially relevant patents from USPC 15/235.3

Projected DCF with 20-80 allocation of economic benefit

26 33 35 47

Chapter 1. Introduction.

The Problem

Brick buildings must have their mortar replaced every few decades. This process of repointing is expensive, difficult, and can take months to years depending on the building size and the size of the masonry crew on the job. One of the primary reasons that repointing is such an arduous process is that removing the mortar ("joint raking") is slow and difficult to do without damaging the surrounding brick, primarily due to the current method used to remove mortar. Angle grinders are used for preliminary passes on the top and bottom of the joint, and a chisel is used to remove remaining mortar left in the center of the grinder passes. Grinding of mortar releases large clouds of harmful silica dust, so a vacuum shroud and often respirators must be used. Angle grinders are also difficult to use on vertical joints, as they either overcut into the brick or undercut the mortar due to the radius of the wheel relative to the length of the joint. Using a rotary hammer to remove mortar decreases dust production, as the percussive motion of the bit removes mortar in large chunks rather than pulverizing it. Using a rotary hammer may also increase speed of removal, since mortar can be removed in just one pass with the tool, and it solves the issue of overcuts on vertical joints. However, the hammer bit is difficult to control and may damage bricks if used alone. Thus, Rhino Tools and Equipment, Inc. (RTE) has designed the Rhino bit guiding attachment for a rotary hammer to be used for mortar joint raking.

The Design Process

RTE was formed during the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Mechanical Engineering senior capstone design class, The Product Engineering Process (2.009). In 2.009,

students are divided into teams of about 20 students. With a total budget of $7000 for product development, each team narrows down their product ideas from six, to three, to one final product design through stages of sketch models and mockups. The teams present their final products to a live audience of about 1250, and thousands more watching online, at the end of the semester in December.

RTE began as the Orange Team of Fall 2017, and decided to pursue the design of a rotary hammer bit guide after considering two very different product ideas before the product mockup stage in November. One potential product was a device that would allow the elderly, who often fear bathing due to risk of falls, to bathe outside of the shower while seated. It had a bathing head that dispensed water through a soapy sponge, but also vacuumed the used bathing water through ports on the side of the bathing head. The team struggled to make the bathing head ergonomic and to optimize the suction of water, which led to a wet and messy mockup. The other product option was a laser-grid projection to allow skiers to see terrain in flat light conditions. Though the product had its technical challenges, the team was also unsure about the potential of lasers mounted on a skier - would they bother or even harm other skiers on the mountain? We also questioned whether the potential market size for such high-tech ski gear would be large enough to justify pursuing the design, as we were considering designing specifically for the niche field of backcountry skiers. Due to these technical challenges and the uncertain user need or desire for these products, and the positive opportunity to dramatically change the way masons work with a relatively simple tool, Orange Team unanimously decided to pursue the rotary hammer attachment for the final six weeks of the class.

In the first design phase, the issue of accuracy and speed in repointing was not handled by a tool attachment at all, but rather by a frame that would mount to the brick wall and provide the

ability to move a cutting tool in two axes, while stabilizing its cutting motion up and down or left to right. This product would have been heavy, bulky, and difficult to move from one workspace to another, so the team decided sufficient stabilization could be obtained with a rotary hammer attachment. Moving on to an assembly review stage, the first conceptualization of a stabilizing rotary hammer attachment was a sheet metal plane attached to the chuck of the rotary hammer. This design could be made simply out of bent sheet metal, but provided limited visibility of the bit and did not allow for flexibility of working direction - that is, the attachment could only be used for repointing in one direction (Figure 1-1). Multiple attachments would be needed, and thus additional time and work to switch the attachments, to allow for repointing in the vertical direction as well as to the left and to the right.

Figure 1-1. First iteration of Rhino attachment with a single-sided device.

The next iteration, built just a month before the final presentation, was essentially the original attachment design reflected about the plane of the bit. Due to the symmetric handle placement, this prototype was named "Hammerhead." Though the symmetric design allowed for joint raking to the left and to the right, and a bent plane beneath the bit allowed for stabilization in the vertical direction, the symmetry of the attachment meant that the weight of two out of three guiding planes was unnecessary. The weight of the Hammerhead attachment made the rotary hammer unwieldy and increased worker fatigue, so the team pursued a second redesign.

The Alpha Prototype

The tool attachment debuted at the 2.009 final presentations was a single-sided device that attached to the chuck of the rotary hammer with a split collar. It has a stainless steel sled that glides along the brick wall, and a guiding fin that slides inside the cleared mortar joint in line with the bit. The sled is attached to the collar with a structural tube. A ball-detent mechanism provides four distinct locking points for the tube, allowing the user to quickly switch the working direction. A vacuum port was added in the back of the structural tube; while the dust generated by using the rotary hammer is minimal, the vacuum further reduces the harmful dust that may reach a mason's airway. This final presentation prototype was relatively lightweight, intuitive for masons to use, increased the speed of joint raking and reduced dust production. It also made raking the short vertical joints faster, easier, and more accurate (less prone to overcuts) than raking would be with an angle grinder.

Figure 1-2. One-sided rotating alpha prototype

The attachment was brought to the Boston Local 3 Bricklayers Union training center to be used on test walls by mason apprentices. We found that the tool attachment was useful not only for guiding the bit laterally, but also for controlling depth of cut with the shoe. Some masons were concerned that one raking pass with the rotary hammer instead of two with the angle grinder might

lead to more brick damage, and that the wide chisel bits are not effective on certain types of mortar. However, masons were excited about the rotary hammer attachment's potential to be used on job sites. Further testing showed that Rhino could increase joint raking speed by one and a half times and decrease dust concentration during cutting without a vacuum by over 99%.

Moving on After the Final Presentation

As a seasoned entrepreneur might say: a good idea is not sufficient to build a good business. At the 2.009 final presentation, the Rhino rotary hammer attachment was presented with great success, receiving overall positive reviews from audience members. Despite this success and our previous user testing with masons, Rhino had never been tested on a real job site, or even been used for longer than just a few minutes at a time.

The business plan presented at the end of 2.009 involved a one-year pilot program with the Boston Local 3 Bricklayers Union to further test the rotary hammer attachment and spread news of the new tool by word-of-mouth. The company would then expand regionally, marketing through the local masonry unions in different regions, focusing on the regions with the highest concentrations of brick buildings and masons. To make and sell the attachments, the company had many options: manufacture the tool in-house and or contract out; sell individual attachments or create a subscription program; sell online, in brick-and-mortar stand-alone stores or through major retailers like Home Depot. Team members spoke with masons and other entrepreneurs making tools for use on job sites to gain insight into how much contractors would be willing to pay.

However, a business plan that focused on growth and expansion over a period of years was not feasible given the time constraints on the team members. Almost all of the team members had received full-time post-graduation job offers or had applied to graduate schools by the end of

winter break. They were not interested in working on the project full-time, and would not have much time after graduation to work on Rhino even part-time. Even if team members were interested in working on Rhino for a significant amount of time after graduation, the small target market of masons who do repointing work made the opportunity to make a living off the device limited. Additionally, the power tools market is hypercompetitive. Looking at the major players' (Bosch, Makita, Hitachi, etc.) product lines, not much differentiates them but stylistic details and inner hardware. Thus, the longevity of a small entrant to the market seemed questionable.

Although many different models could have been chosen given an unlimited number of team members willing to work on the product, the team determined that the business model should not be to grow and expand indefinitely, but rather have a lower time commitment to commercialization and a quick exit strategy. Thus, the team decided pursue a licensing deal with an established tool company.

Before licensing the Rhino tool attachment design, the team would have to take two major steps. The first would be to solidify the intellectual property on the IP by obtaining a full patent and assigning all intellectual property to a corporate entity. The second would be to pursue the pilot program with Boston masons, to further demonstrate Rhino's efficacy and advantages over traditional joint raking methods. The following chapters will examine the patenting process and decision-making process in the business model, as the team moves towards commercialization of the Rhino rotary hammer attachment.

Chapter 2. Choosing a Business Model

Although a licensing business model was ultimately chosen for Rhino based on the schedules of the team members, many options were considered. In the case that a future team has members that are more committed to the project and not to full-time positions post-graduation, it will be useful to follow a similar procedure in deciding upon a business model.

2.1 What is a Business Model?

The simplest definition of a business model is merely the way in which a business plans to make money [1]. There are many conflicting and overlapping definitions of the business model floating around. As a necessary but not sufficient condition, the business model includes assumptions about the market, customers and competitors, and the company's strengths and weaknesses [1]. The business model tells a story about the enterprise, its customers and what they value; it can contain all the activities associated with making and selling something. At the most basic, a business model can be expressed in just a few sentences; at its most complex, it can be more of a business plan, with many strategic details and financial data.

A business model can be adapted from one of many basic forms, and it is relatively simple to find additional information on planning for businesses within each of the forms. Andrea Ovans of the Harvard Business Review provides a useful chart detailing basic business models such as crowdsourcing, leasing, and subscription in her article "What is a Business Model," cited below and available online at the time of this writing [1]. It is a useful resource for those looking for new ideas or unsure about which path to take with their business.

According to Ramon Cassadesus-Masanell and Joan Ricart, there are three types of choices to be made in creating a business model. Policy choices are "actions an organization takes across

all operations." Do we only work with union labor? What kinds of benefits do we offer to employees? Asset choices involve "tangible resources that a company deploys," such as warehouse space or even intellectual property. Governance choices refer to the decisions about who gets to make the other kinds of decisions [2]. From personal experience, in the transition from a class like 2.009, where everyone is on equal footing, to a real corporation, it is incredibly important that governance choices are handled early and with frankness, rather than being delayed because it doesn't seem very important to divide power before graduation or being made poorly due to lack of honesty and openness between team members.

All of these choices can either be flexible (relatively easy to change) or rigid (time consuming and difficult to change). Decisions that lead to a change in company culture are especially rigid [2].

2.2 Business Models for New Ventures

Importantly, a business model can and should change over time with shifts in the market, the company's directors and employees, technology, or other factors. In starting a business, it is important to be able to shift the business model as the founders learn more about every aspect of the business, from the market to the customer needs to manufacturing and distribution. Additionally, a new venture that does not yet face competition faces inherent uncertainty; though for something like Rhino competition from established tool companies is certain, the exact reactions of the behemoth companies that already exist in the tool space are uncertain and that risk must be factored into the choice of business model [2].

2.3 Business Models Considered for the Rhino Tool Attachment

Three business models were seriously considered before settling on one for commercializing Rhino: buying rotary hammers wholesale and selling the Rhino attachment already connected to the chuck; selling a standalone Rhino attachment, or licensing out the IP to an established tool company. The team had a few concerns about marketing and selling Rhino related to information gained during primary and secondary market research. The first was that users would find attaching the device to the rotary hammer too difficult or too much effort, especially in earlier design iterations. The second was that buyers would rely on brand recognition and it would be difficult to break into the market, or that masons would be set in their ways and not want to experiment with a new joint raking method. As the power tool market has a few big players and is very competitive, our biggest concern was that a large tool company would design around our IP, or simply take it, and market Rhino under their own brand without our involvement. Each of the potential business models had positives and negatives. The first option that we considered was selling rotary hammers as a re-saler with Rhino already attached, and it had some upsides. The attachment could be designed to be as robust as possible, rather than intuitive to attach and detach. We also thought that selling Rhino with a rotary hammer would allow sales to masons who might not use the tool already. We later learned that rotary hammers are fairly ubiquitous on job sites, and also assumed that masons that do not already use rotary hammers would be unlikely to adopt Rhino anyway. There also were concerns about potential IP infringement issues in reselling modified, branded tools. Additionally, as the attachment design became simpler with

iteration, reselling hammers seemed like an unnecessary complication and expense.

Selling a standalone Rhino attachment had an obvious benefit compared to the other models, as it had the largest potential for high margins. Tool attachments, like vacuum shrouds, in

the masonry market are typically sold for $200 or more. The Rhino collar would cost on the order of tens of dollars to produce, and the sled just in the single digits, leaving the seller with a very wide margin. However, such a business model has major gaps. How much instruction will the user need to attach Rhino? How will we protect the device from IP poachers? And will word of mouth and affordable marketing be enough to convince masons across the country to use Rhino?

Finally, a licensing deal has multiple benefits outside of the decreased commitment required of the founders. It is difficult to set up scaled-up manufacturing as a small, new company, while established companies have the resources needed to mass produce a new product. They could use existing manufacturing facilities instead of contracting out the work and making a massive initial investment, outside the capability of a startup. The large company already has supply chains, distribution channels and brand recognition. Most critically, a large company has the resources to defend IP in the competitive power tools market that a small company would not have. There are some risks and drawbacks to licensing - the company to which the IP has been licensed could face financial difficulties and decide not to pursue production of the product; there are higher administrative costs; and handing over IP to a licensee may allow them to gain knowledge and bypass the IP without paying a royalty [3]. There may be decreased potential for profit under a licensing business model, as royalties would be the only income, but there is also vastly decreased risk of theft of IP, and financial risk involved in loans to start production.

Given the hypercompetitive nature of the power tools market and the limited resources of a new company, a business model in which the Rhino design is licensed to an existing tool company is the easiest and least risky option. Regardless of the fact that a quick-exit business model is necessary given the real constraints on the team, pursuing licensing of the Rhino attachment is a sound strategic decision.

References

[1] Ovans, A., 2015, "What Is a Business Model?," Harvard Business Review.

[2] Casadesus-Masanell, R., and Ricart, J. E., 2011, "How to Design a Winning Business Model," Harvard Business Review.

[3] Smith, Gordon V., and Parr, Russell L., 1993, Intellectual Property: Licensing and Joint

Chapter 3. Intellectual Property

The licensing business model depends on having strong intellectual property (IP). A "design" or "idea" in the abstract cannot be licensed: the IP is what is actually being licensed, so to get the maximum royalty on it the patent or trademark must be strong, so that it is difficult to design around. An idea must be patentable for there to be IP to license. There are four requirements for patentability: Utility, Novelty, Non-Obviousness, and Disclosure [1]. This chapter will detail the Rhino tool attachment's ability to meet these criteria.

3.1 Utility

The ultimate goal of a patent system is to create short term monopolies that encourage innovation that might spur economic growth; thus, it makes sense that a patented design must be at minimum useful [2]. The definition of utility depends on the written statutes and court precedent. 101 of the 1952 Patent Act merely states the requirement of a patentable design being "useful" [3]. The Federal Circuit has further clarified that to satisfy 101, the patent must have an immediate benefit to the public [4]. Additionally, the patent examination guidelines state that the invention has utility if a person having ordinary skill in the art (PHOSITA) "would immediately appreciate why the invention is useful based on the characteristics of the invention" and if "the utility is specific, substantial, and credible" [5].

Rhino must meet all of the above requirements to meet the utility patentability criteria. While the determination of a relevant PHOSITA takes some consideration and will be addressed in later sections, 2.009 faculty experienced in mechanical design and product development, as well as masons who have been repointing buildings for decades had very positive reactions to the Rhino attachment design. Thus, a PHOSITA in the art of mechanical design or masonry would

"immediately appreciate" Rhino's utility, as mandated by the patent examination guidelines. As required by those guidelines, Rhino's utility is specific: Rhino increases joint raking speed, decreases number of bricks chipped and decreases dust production. The utility is substantial, as measured dust reduction was significant, and joint raking speed was also observed to be much faster. Additionally, the Rhino attachment meets the requirement of having immnediate public benefit, as its increase in joint raking speed will result in increased profits for contractors. The pilot program described in Chapter 1 will lend additional credibility to the tests that have been performed thus far.

3.2 Novelty

Novelty is typically considered a much more difficult criterion to meet than the utility requirement [4]. 102 of the Patent Act states that an invention is not novel if it is "patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention; or in a patent or patent application naming another inventor filed before the effective date" [4]. Thus, the team needed to ensure that a tool like the Rhino attachment was neither on the market nor already patented.

To determine if an attachment like Rhino was already on the market, the websites of stores like Home Depot and major tool brands like Bosch, Hitachi, Makita and Milwaukee were searched, as those places are where contractors and masons shop. Nothing like Rhino was found. However, the most telling indication that nothing like Rhino currently exists was the reaction from masons while testing Rhino - they had never seen anything like it before, despite being the experts in repointing field.

3.2.1 Preliminary Prior Art Search

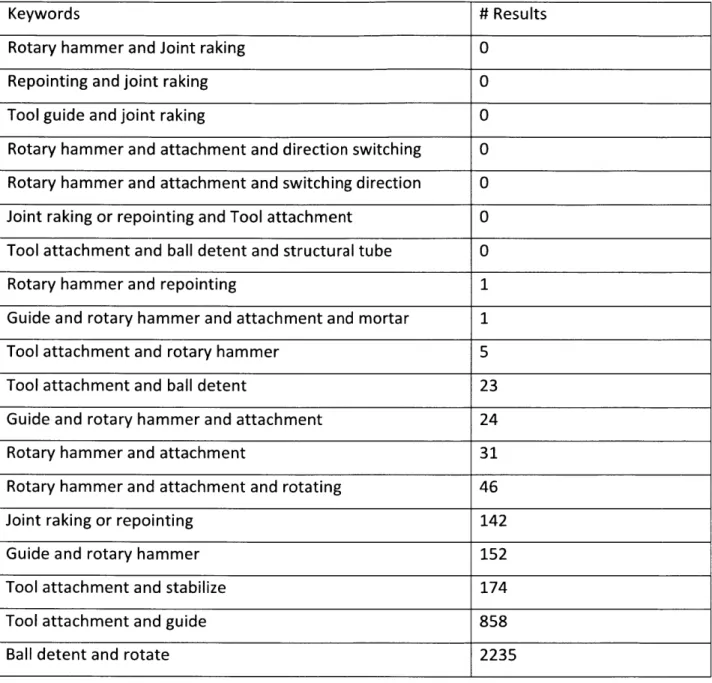

To determine if an attachment like Rhino had been patented, but not successfully commercialized, a thorough prior art search needed to be conducted. Two distinct methods were used to identify relevant patents. The first method was a simple keyword search to obtain a quick understanding of density and distribution of IP in Rhino's general field. Potential keywords relevant to Rhino were generated based on components of the tool attachment, the rotary hammer to which it is attached, and its purpose for joint raking and repointing. Combinations of two to three keywords were searched on the USPTO Patent Full-Text and Image Database on March 10, 2018 [6]. The numbers of results from each search are shown in Table 1, listed in order of increasing number of results.

It is useful to begin the prior art search analysis with the search terms that realized no hits, since those combinations expose where there has been little to no IP activity. It seems that though there has been a lot of invention in the more general joint raking and repointing space, there is no patent that includes reference to both a tool attachment and joint raking or repointing. Additionally, the three most important components of Rhino - that it is a "tool attachment," includes a "ball detent" mechanism and has a "structural tube" - yielded no hits. "Rotary hammer" and "joint raking" yielded no results, while "rotary hammer" and "repointing" yielded one result, US Patent #5,058,275, that was not in itself a patent for a method ofjoint raking with a rotary hammer. These keyword combinations were the ones that most closely approximated the whole of Rhino's design and repointing method, so the lack of results indicates a potential opening in the IP landscape for joint raking using a rotary hammer tool attachment.

Table 3-1. Preliminary prior art search results (03/10/2018)

Keywords # Results

Rotary hammer and Joint raking 0

Repointing and joint raking 0

Tool guide and joint raking 0

Rotary hammer and attachment and direction switching 0

Rotary hammer and attachment and switching direction 0

Joint raking or repointing and Tool attachment 0

Tool attachment and ball detent and structural tube 0

Rotary hammer and repointing 1 Guide and rotary hammer and attachment and mortar 1

Tool attachment and rotary hammer 5

Tool attachment and ball detent 23

Guide and rotary hammer and attachment 24 Rotary hammer and attachment 31

Rotary hammer and attachment and rotating 46 Joint raking or repointing 142 Guide and rotary hammer 152

Tool attachment and stabilize 174 Tool attachment and guide 858

On the other hand, some keyword combinations yielded relatively massive numbers of results. These keyword combinations tended to be less specific. "Tool attachment" and "guide" yielded 858 results; "tool attachment" and "stabilize" yielded 174 results, and "ball detent" and "rotate" yielded 2235 results; "joint raking" or "repointing" yielded 142; "guide" and "rotary hammer" yielded 152. These results confirm the common-sense assumptions that a rotary ball-detent mechanism may not be considered novel, or that there are many patents pertaining to joint raking or repointing already. It was impossible within the constraints of a single semester to read each of the 2235 results of searching "ball detent" and "rotate," but a brief review of the patent titles from the categories with 20 to 200 results did not reveal, at face value, any prior art very close to the Rhino attachment.

Three keyword combinations returned fewer than 10 patents. "Tool attachment" and "rotary hammer" returned five patents. A rotary hammer tool attachment may or may not be similar to the Rhino attachment; a review of these patents showed that they were not relevant. Two of the found patents were not even for rotary hammer attachments, but for adaptations to the chisel bit [7, 8]. Another of the patents describes a rotary hammer attachment consisting of a blind bore to slide over the bit and a generic retaining mechanism for attachment to the power tool, to allow for rapid switching between drilling and chiseling [9]. The fourth describes an invention that allows for debris removal without a vacuum attachment, and the fifth a rotary hammer attachment that allows for easier anchor driving and setting [10,11]. None of this prior art is particularly relevant to the Rhino attachment's component parts, mechanism, or function.

Two keyword combinations ("rotary hammer" and "repointing"; "guide" and "rotary hammer" and "attachment" and "mortar"), however, retrieved just one patent, indicating that

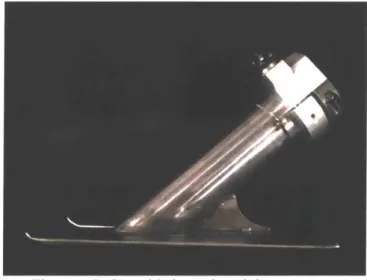

someone had indeed thought of using the power tool in the repointing process. These two combinations retrieved the same patent, US Patent #5,058,275, or "Chisel" [12].

The "Chisel" patent, filed in 1991, describes a device the most similar to the Rhino tool attachment out of all the US patents read. The purpose of the chisel is to remove material between two adjacent bricks. The chisel is supported by shoulders that set the depth of the chisel, and the shoulders may or may not have rollers to avoid marking bricks [12]. Patent drawings of this chisel device are shown in Figure 3-1, showing the chisel, with its depth below the brick set by rollers. This chisel invention shares a few similarities with the Rhino attachment: it uses a chisel (not necessarily powered, as in a rotary hammer) to remove mortar from between bricks, with depth set by a shoulder, as Rhino's is set by the sled.

17 3 22 18 19 2r3 22 24

4-m3

Figure 3-1. US Patent 5058275, "Chisel" [12]

While "Chisel" lacks direct reference to joint raking with a rotary hammer, its Description section mentions the German Patent Specification No. DE 3312019 ("Grooving chisel for hammer drilling machines") which does describe a sleeve for a rotary hammer to be used for mortar removal similar to Rhino's [12]. "Chisel" notes that the German patent describes "the drill extended through a sleeve the end of which bears on the brick surface so as to limit the depth of penetration of the

drill. Unfortunately, the sleeve prevents visual monitoring of the progress of the drill bit... It can easily be thrown out of the crack" [12].

The original German patent's abstract (translated through Espacenet) describes a device for creating grooves in hard surfaces, such as rock or concrete, but not necessarily in mortar [13]. The device is "fixed in the locating part of a hammer drilling machine by means of a drill holder"

[13]. It is unclear from the patent translation whether this attachment through a "drill holder" is an attachment to the chuck or by some other mechanism, but the exact attachment mechanism does not seem to be specified. From the patent drawings (Figure 3-2), it seems as though the drill-bit itself may be attached to the tube somehow, or the tube is attached to the drill in a non-specific manner. Only the depth of the bit controlled. Since the tool ensures constant bit depth, but does not control lateral motion, it does not afford the primary advantage of using the Rhino attachment.

19-2

4 20

3 7 t 6 1

a

Figure 3-2. German Patent Specification No. DE 3312019 [13]

Therefore, there are many aspects of Rhino that still seem novel, despite some overlap with the two patents discussed above. The guiding fin that prevents lateral displacement of the chisel

bit, as well as the vacuum system and specific locking and rotational attachment mechanism are unique to Rhino.

3.2.2 Search Using Patent Classifications

Having exhausted the relevant patents through keyword searches, the patent database was also searched by classification as suggested by the USPTO's seven-step search strategy [14]. By finding classifications relevant to the Rhino attachment, a broader search could be carried out. To find relevant Cooperative Patent Classifications (CPCs) and US Patent Classifications (USPCs), the USPTO website was searched using terms similar to those generated for the preliminary

keyword search (Table 3-1).

First attempting to find any subclasses specific to the repointing process, the website was searched with "repoint," "repointing" and "joint raking." None of those terms yielded any results. Searching for "mortar" and "masonry" also did not yield any relevant subclasses. That search did find CPC E04B ("General building constructions; walls, e.g. partitions; roofs; floors; ceilings; insulation or other protection of buildings"), but none of E04B's subclasses that mentioned mortar included mortar removal [15]. Searching for "mortar joint" also recovered CPC E02D ("Foundations; Excavations; Embankments; Underground or Underwater Structures"), but the title of the classification did not sound relevant to Rhino's purpose, and there did not seem to be any relevant subclasses within E02D [16].

Searching for "tool guide" rather than with industry-specific keywords led to more relevant results. USPC 83, "Cutting," contains multiple subclasses for driving or guiding a tool (subclass 523) [17]. Subclasses of 83/523 were 544 "with guard means," for inventions "provided with a protective obstruction to prevent contact of an extraneous object... with a part of the machine"

[17]. Given that "extraneous object" being a brick, and the bit the "part of the machine," Rhino could potentially fall under 83/544. From the patent titles within it, the subclass seems to include mainly safety guards for power tools. Still, the subclass could merit further attention.

Closely related to 83/544 is subclass 83/545, which includes "Static" means to drive or guide a tool [17]. Unsurprisingly, the 26 patents in this subclass do not seem particularly relevant to Rhino either. They are mostly methods of cutting by shearing, rather than impact, and similarly to 83/544 are disproportionately guides or guards for safety. Another subclass of 83 (83/859) describes devices that include "a structural unit or housing which provides an environment for a cutting tool" [17]. At first glance, the structural tube of the Rhino attachment seems like it may fulfill that description. The 83/859 subclass contains more patents (as of an April 24, 2018 search) than the other two subclasses, at 120, so it may be a more general subclass. However, the patents in the subclass also appear to be mostly for cutting by shearing, and many of them seem to be concerned with mounting, storing or carrying machines rather than guiding the cutting motion; still, the subclass' patents may warrant more attention.

It seemed like a logical next step to move from viewing subclasses related to keywords associated with the Rhino attachment, to examining the subclasses to which the previously described "Chisel" patent belonged. "Chisel" belongs to two subclasses of USPC 30. USPC 30, "Cutlery," contains cutting tools that move relative to the work, and may be power operated [18]. The subclasses under which "Chisel" is classified are 30/168 and 30/170, which contain cold chisels for cutting cold metal and wheeled implements, respectively. Neither of these subclasses seem to describe the Rhino tool attachment.

However, "Chisel" also belongs to two subclasses of USPC 15. USPC 15 contains patents relating to brushing, scrubbing, general cleaning and "removal of foreign matter" [19]. While

cleaning does not directly relate to Rhino's purpose, it is involved in removal of foreign matter, i.e. mortar. The subclasses 15/105.5 and 15/235.3, to which "Chisel" belongs, directly relate to mortar, both containing patents on implements for mortar joint finishing [19]. Subclass 15/105.5 contains 26 patents, and 15/235.3 contains 47 patents according to an April 17, 2018 search. Patents from these subclasses are summarized in Tables 3-2 and 3-3, respectively, with patents deemed irrelevant from their titles omitted. Generally, if these patents were related to Rhino's function, they did not include the components of the Rhino design still considered to be novel after consideration of Patent #5,058,275. The patents from these classes were also generally concerned with the cleaning and finishing of soft, not hardened, mortar between bricks, grout between tiles or mastic in drywall.

Table 3-2. Potentially relevant patents from USPC 15/105.5

Patent Name U. S. Patent Notes on Title and Abstract Number

Cementitious surface 8974219 This tool is used for pointing, not raking finishing tool system

Caulk remover and 7908702 This is not relevant. It is used for caulking, smoother and the novelty is in hinge mechanism Grout joint clean out and 7484263 It removes excess tile adhesive, but not leveling tool with a similar design to our raking tool. Drywall edge shaping tool 7386914 It cleans and shapes bullnose corners. The

mechanism does not seem relevant. Two-in one caulk finishing 7127769 The only relevant aspect of the tool is that tool it contains a clip that attaches it the

caulking gun. The function is similar to Rhino, but not the mechanism.

Caulking tool 5471704 This is used for caulking, not removing material.

Caulking tool 5239725 This is used after caulk is applied to create a uniform bead.

Chisel 5058275 Described in depth above.

Drywall finishing tool 4907955 This tool is for applying plaster to a wall. Masonry tool 4856135 Describes a tool for raking unhardened

mortar at predetermined depth between bricks with a wheeled design. It does have depth setting, but no guidance and is not

used for raking hardened mortar.

Drywall tool 4784598 Describes a tool for applying drywall to a joint.

Combination joint raker 4682383 This rakes a joint with soft mortar and and jointer smooths the mortar. It is wheeled and sets

depth.

Caulk bead tool 4586890 This compresses and contours

caulk/grout/putty. It is not very similar to Rhino.

Joint grouting tool 4558481 Excess material raked out with wheeled tool.

Finishing tool for 4391013 This smooths joints of interior, not smoothing wallboard tape exterior walls. So, it is not relevant. joints

Table 3-3. Potentially relevant patents from USPC 15/235.3

Patent Name U.S. Patent Notes on Title and Abstract Number

Caulk remover and 7908702 Also in USPC 15/105.5. Described in Table

smoother 3-2.

Grout joint clean out and 7484263 Also in USPC 15/105.5. Described in Table

leveling tool 3-2.

Guide device for use with 7338270 Describes a removeable guide attached flat box device in applying to a flat box for use in applying mastic. drywall mastic Guide contains a guide bar, bracket, and

spring, and doesn't seem to be a similar guide system or for a similar purpose to Rhino.

Hand-held device for 6578229 Device for removing joint filler that has a removing joint fillers body with a "peeling element". It is not

the same as Rhino.

Combination joint raker 4682383 Also in USPC 15/105.5. Described in Table

and jointer 3-2.

Abrading tool 4435923 This device clamps an abrasive pad with springs. Besides the ability to motorize, it doesn't seem very relevant.

Tile group scraper tool 4155142 A traction tool for scraping grout consists

of toothed wheels that extend below the base. It does not seem relevant.

3.3 Non-Obviousness

The non-obviousness patentability requirement is more nebulous than the previous two requirements of utility and novelty. An obvious patent is one that involves a trivial recombination of prior art, that would be obvious to a Person Having Ordinary Skill in the Art (PHOSITA) [20]. 103 of the Patent Act states: "A patent for a claimed invention may not be obtained... if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains" [20]. The primary hurdle in determining obviousness of a patent is determining what exactly "obvious" and "ordinary skill" mean here.

Obviousness is "not a question upon which there is likely to be uniformity of thought" in every case [20]. The flexibility of the non-obviousness requirement was further supported by a patent-law student working at a local patent law firm; he reports that determination of obviousness varies between examiners [21]. Obviousness can be argued based on the examiner's responses to the initially submitted claims [21].

The scope of the prior art being considered in determination of obviousness depends on the identification of the PHOSITA. The PHOSITA is a hypothetical person with characteristics chosen to best serve the patent system; the PHOSITA has knowledge of all prior art and its references, creativity typical of people in the relevant art and of the relevant skill [22]. Since the mid-20th century, the PHOSITA has typically been considered to have a designer-level role, as opposed to being an "ordinary mechanic" [22].

Though the exact wording of the claims on Rhino's patent have not been determined, arguments can be made against its obviousness. An obvious invention can be thought of in a

"blinding flash of the obvious" [4]. As discussed in Chapter 1, Rhino's design was iterated over months, so it was hardly created in a blinding flash.

Additionally, certain aspects of Rhino's design will protect it from an assertion of obviousness. Currently, there are tool attachments on the market, such as vacuum shrouds for angle grinders [23]. However, these attachments use a different mechanism to attach to the power tool, so an argument asserting that the Rhino attachment with its split-collar is a trivial recombination of U.S. Patent #5,058,275, a vacuum shroud and its attachment would be difficult to make.

However, the Rhino shoe may be difficult to claim as non-obvious. Depth-setting shoes exist for circular saws and other tools, as well as in patents like U.S. Patent #5,058,275. It remains to be seen if the claims can be written in such a way as to avoid an assertion of obviousness on the shoe's combination with the rest of the Rhino attachment.

3.4 Disclosure

Patenting an invention requires full disclosure of that invention [1]. Therefore, all aspects of the Rhino design that are to be protected by IP must be disclosed to the extent that another engineer could recreate the tool.

The 2.009 Orange Team applied for a provisional patent in November of 2017. The USPTO requires that the full patent application be filed within one year of the provisional patent application filing date or public disclosure. Since our provisional patent was filed prior to the 2.009 final presentation, the deadline to file a patent application is a year from the provisional patent filing date.

References

[1] Graham, A., "Patents: About Patents," MIT Libraries [Online]. Available: https://libguides.mit.edu/c.php?g=1761 8 4&p=1159290. [Accessed: 16-Apr-2018]. [2] "Origins & Underlying Concepts of Patent Law," Law Shelf [Online]. Available:

https://lawshelf.com/courseware/entry/origins-underlying-concepts-of-patent-law. [Accessed: 22-Apr-2018].

[3] "35 U.S. Code 101 -Inventions Patentable," Legal Information Institute.

[4] "Utility, Novelty, Statutory Bar, & Nonobviousness," Law Shelf [Online]. Available:

https://lawshelf.com/courseware/entry/utility-novelty-statutory-bar-nonobviousness. [Accessed: 18-Apr-2018].

[5] "2107 Guidelines for Examination of Applications for Compliance with the Utility Requirement [R- 11.2013]," Manual ofPatent Examining Procedure, USPTO [Online].

Available: https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2107.html. [Accessed: 23-Apr-2018]. [6] "US Patent Full-Text Database Boolean Search" [Online]. Available:

http://patft.uspto.gov/netahtml/PTO/search-bool.html. [Accessed: 24-Apr-2018].

[7] Quinn, T. J., Johnson, D. N., and Probst, F., 2015, "United States Patent: 9085074 -Chisels." [8] Quinn, T. J., Johnson, D. N., and Probst, F., 2016, "United States Patent: 9333635 -Chisels." [9] Gawron, A. F., and Dillon, W. E., 1977, "United States Patent: 4007795 -Attachment for a Rotary-Hammer Tool."

[10] Baker, T., Barhitte, J., Jacobs, B., and Krondorfer, H., 2013, "United States Patent: 8397342

-Debris Removal System for Power Tool."

[11] Kosik, T., and Caruso, D., 1999, "United States Patent: 5979913 -Universal Driving and Setting Tool and Method of Using Same."

[12] Staubli, J. G., 1991, "United States Patent: 5058275 -Chisel."

[13] Verzicht Des Erfinders Auf Nennung, 1984, "Grooving chisel for hammer drilling machines," (DE19833312019 19830402).

[14] 2015, "7-Step U.S. Patent Search Strategy Guide."

[15] "CPC Scheme -E04B GENERAL BUILDING CONSTRUCTIONS; WALLS, e.g.

PARTITIONS; ROOFS; FLOORS; CEILINGS; INSULATION OR OTHER PROTECTION OF BUILDINGS," USPTO Cooperative Patent Classification [Online]. Available:

https://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/cpc/html/cpc-EO4B.html. [Accessed: 24-Apr-2018].

[16] "CPC Scheme -E02D FOUNDATIONS; EXCAVATIONS; EMBANKMENTS; UNDERGROUND OR UNDERWATER STRUCTURES," USPTO Cooperative Patent Classification [Online]. Available:

https://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/cpc/html/cpc-EO2D.html#E02D2300/00. [Accessed: 24-Apr-2018].

[17] "Class Definition for Class 83 -CUTTING," United States Patent and Trademark Office [Online]. Available: https://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/uspc083/defs083.htm. [Accessed: 16-Apr-2018].

[18] "Class Definition for Class 30 -CUTLERY" [Online]. Available:

https://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/uspc030/defs030.htm. [Accessed: 25-Apr-2018].

[19] "Class Definition for Class 15 -BRUSHING, SCRUBBING, AND GENERAL CLEANING" [Online]. Available:

https://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/uspcO 1 5/defs0 15.htm. [Accessed:

25-Apr-2018].

[20] James Boyle, and Jennifer Jenkins, "Non-Obviousness," Intellectual Property: Law & the

Information Society - Cases & Materials, CreateSpace, pp. 743-769.

[21] Tang, M, 2018, Patent Law Student, private communication

[22] Darrow, J., 2009, "The Neglected Dimension of Patent Law's PHOSITA Standard," Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, 23(1), pp. 227-258.

[23] "Dustless Technologies 5 in. Dust Buddie Dust Shroud for Hand Grinders-D 1835," The

Home Depot [Online]. Available: https://www.homedepot.com/p/Dustless-Technologies-5-in-Dust-Buddie-Dust-Shroud-for-Hand-Grinders-D1835/100653780. [Accessed: 03-May-2018].

Chapter 4. Creating a Licensing Agreement

As discussed in the previous chapters, licensing is the most optimal, and the only realistic commercialization option for Rhino. The practical details of the licensing process will be discussed in this chapter. A suitable partner company must be found and a royalty rate and structure that is agreeable to both RTE and the partner company must be decided.

4.1 Potential Partner Companies

Multiple methods were used to identify potential partner companies. First, the team could observe the tools and brands that masons were using for repointing. Their power tools were primarily Bosch; the masons believed the brand to be higher quality than other options such as Makita, Hilty or Milwaukee. However, they did also use tools from smaller, more niche brands, such as their angle-grinder vacuum shrouds. The team also reached out to connections in industry through 2.009 team mentors.

It is important to look further than just what masons are currently using to assess all potential options. Thus, a comprehensive list of the major tool companies and their subsidiaries operating the US was compiled, eliminating those companies that only produce hand tools or industrial machinery [1]. Company websites were browsed to ensure that they produce rotary hammers, hammer drills or angle grinders. The selected companies are Bosch; Stanley Black and Decker and its subsidiaries Bostitch, DeWalt, Porter Cable, and Craftsman; Apex Tool Group's subsidiaries Dotco and Master Power (which produce mainly pneumatic tools); Techtronic Industries subsidiaries AEG, Milwaukee Tool, and Ryobi; Emerson subsidiary Rigid; KKR subsidiaries Hitachi and Metabo; and Makita [2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

There are many options for potential partnerships outside of the preferences masons expressed; in fact, smaller tool manufacturers may have an added interest in licensing Rhino in an attempt to compete with more established companies like Bosch.

4.2 Determining Royalty Rate

It is important that RTE has a target royalty rate in mind when negotiating with potential licensees, and a minimum acceptable royalty rate to accept a deal. There are many factors that may be considered in determining the target royalty rate, including industry standards, risks to the licensor or licensee, and projected cash flows.

There are many heuristics that entities may use to determine a royalty rate. One is merely an arbitrary allocation of economic benefit. The twenty-five percent rule is one such arbitrary allocation; it states that the royalty rate should be at least 25% of the gross profit [9]. This rule's first deficit is that it is vague - some may interpret gross profit to be the profit after manufacturing expenses or profit less operating expenses, or pre- or post-tax. Another method to determine the royalty rate is to ensure a return on research and development costs. However, any simple heuristic will fail to take into account the actual value of the IP. A quarter of respondents to a 1997 survey said that they used the 25% rule to determine royalty rate, but their example should not be followed [10]. The royalty rate should reflect both the potential revenue associated with the IP and the environment in which it will be used, as some products will have higher support and operational costs, reducing the overall value of the IP [11].

One way to determine a reasonable royalty rate is to simply look at average royalty rates in the same industry. Like other simple heuristics, this determination is arbitrary and fails to account for the profitability of the ultimate product that is developed using the IP, and thus should

not be used as the sole basis for a target royalty rate, but can be used to give a starting estimate [11]. The industry average can give the uninitiated an idea of what may be considered reasonable by a licensee. In 2014, the average royalty rate was 4.8% in the machine and tools industry and

5.6% in the building and construction industry [12].

This average royalty rate of about 5% should be taken as a reasonable approximation of a target royalty rate, but not the actual amount; instead, the royalty rate should be determined based on the risk of investment in the IP relative to the reward and a fair distribution of economic benefit [11]. Factors that should be considered against the value of the IP include the investment rates of return for similarly risky investments, the assets required to commercialize the IP, the relative

investment risk associated with those assets, and the risk associated with competition, future or current regulations (such as OSHA, in the case of masonry), and industry economics (such as a potential housing bubble) [11].

Risks associated with IP come in two primary forms: business risk, and financial risk [11]. Business risk is associated with business elements and relationships between the enterprise and other entities, while financial risk is associated with investment. Business risk decreases with increasing size of the licensee company; it is is also lower if the customer base and company product portfolio are large and varied. Government regulation increases risk as does the need for a large inventory and intensive sales and marketing work [11]. Financial risk includes the risk of false or error-filled accounting data presented by the licensor, purchasing power risk (if inflation is large relative to investment gains), interest rate risk (if low-risk investments like bonds have high interest rates, riskier investments are less enticing), and the risk of a market collapse of unknown cause [11].

What does all of this mean for RTE? The Rhino tool attachment was designed for a small market, so the small customer base increases the risk in developing the product; however, depending on the company, it does have the potential to widen a company's existing customer and product portfolio. The Rhino attachment will also have a relatively large profit margin, and will not require the same massive upfront investment from a large company that already has manufacturing capacity. Upfront investment is also reduced by the lack of molds needed for casting or injection molding, as the attachment is made by sheet metal bending, welding and machining. The larger the company that RTE targets for licensing, the lower the risk for the licensee.

In terms of the current economy, inflation is currently at the federal reserve's target of 2% but may rise higher than that, making investments relatively riskier [13]. Compounding that financial risk, interest rates have risen over the past decade since the federal reserve dramatically lowered them after the Great Recession, and they are set to rise again before RTE completes a licensing deal [14].

The lifespan of IP must also be taken into account. The actual economic life of the IP may be shorter than the time prescribed by law or contract [11]. This shorter lifespan may be due to a change in the availability or price of raw materials/commodities, environmental concerns and regulation, or advancements in technology that render the original IP obsolete. The economic life of the IP cannot exceed the amount of time during which the products made using the IP have space in the market [11]. So, though whatever patents RTE acquires on the Rhino attachment will be valid for 20 years from the filing date, changes in the prices of steel, aluminum, or construction materials or any updates to OSHA regulation may damage Rhino's position in the market or kick it out of the market entirely [11].

Ultimately, the royalty rate can be decided by balancing the value of the license to the licensor and the licensee using forecast revenues from the IP. The value of the license to the licensor (RTE) is the present value of future compensation less the present value of the costs of the licensing agreement and income not gained by exploiting the IP internally; the value to the licensee is the present value of the future revenue gained by exploiting the IP less the costs of that exploitation [11].

Before the end of 2.009, cash flows were forecasted to determine an approximate net present value (NPV) for the company. The cost to manufacture and assemble a single Rhino attachment unit was estimated to be about $23.50 at scale. Given that vacuum shrouds, whose function Rhino includes and improves upon, sell for about $200, and based on projected cost savings for contractors from replacing traditional joint raking methods, an approximate price for the attachment was set at $275.

The market was sized by approximating the percentage of masons who work onjoint raking at about 80%, based on conversations with the Boston Local 3 Union. The total number of brickmasons and blockmasons in the United States in 2016 was 91,100, giving Rhino about 73,000 potential users [15]. Data on the distribution of brickmasons and blockmasons nationally, by state, were also obtained.

The cash flow forecasts were performed using a discount rate of 10%, and assuming an initial rollout in the Northeast region before expanding nationally. It was also assumed that, on average, a mason using Rhino would use 1.5 of the attachments per year given our understanding that the industry standard is not recycling tools. With the kind of aggressive market entry strategy that might be expected from a large established tool company, the NPV of the Rhino attachment over the first 5 years is about $1.4 million after tax.

There are two primary ways RTE could structure a licensing deal. The first would be a royalty rate based on revenue, or a lump-sum royalty with an added royalty rate. The benefit of a lump-sum royalty to RTE is obvious: even if Rhino does not sell, RTE makes some money. The lump-sum could be relatively small but still be large enough to allow RTE to pay for patenting expenses and beta-testing costs. This relatively small sum will leave the NPV of the investment essentially unchanged for the licensee, reducing the risk on their end.

Based on the projections described above, the maximum royalty rate that can be paid to RTE with the licensee still having a positive NPV of the license is about 29%. This rate is the absolute maximum, above which the licensee would make no profit; the licensee obviously wants to make a sizable profit and will thus demand a royalty rate far lower than that 29%. It is interesting to think about royalty rates in terms of the percentage of the total NPV of the Rhino tool attachment that they allow RTE to collect. Considering a lump-sum royalty of $5000 per year, to collect 50% of the NPV, a rate of about 14% should be charged; to collect 20%, a royalty rate of 4-5% should be charged, which is in line with industry standards. A sample calculation of this rate can be seen in Table 4-1.

Some additional provisions can be added to a royalty agreement that can impact the value to both the licensor and licensee. Some provisions include considerations for the potential cost of

litigation for patent infringement, which is made more likely by an industry that is well developed, highly competitive, and saturated with large, resourceful companies [11]. The uncertainty of such an event can be factored into the above DCF analysis by increasing the discount rate, or by estimating the cost of such an event and adjusting for its estimated probability [11]. The license may also be exclusive, in which case it is worth more to the licensee, especially if the market is hypercompetitive, the company has the resources to serve a large market, and has its own IP to

Table 4-1. Projected DCF with 20-80 allocation of economic benefit Revenue COGS Gross Profit SG&A Expenses Labor Expenses Marketing Expenses Distribution Expenses R&D Operating Profit Lump-sum royalty Royalty (4.5%) NPV of royalty Tax Expense Net Income Net Present Value

Total NPV for Licensee Total NPV for Licensor 1 2' 3. 5 $363,325.93 $908,314.81 $1,679,740.74 $2,494,800.00 $3,449,671.30 $33,353.66 $77,617.81 $143,171.63 $212,461.25'_ $288,517.96 $329,972.27 $830,697.00 $1,536,569.11 $2,282,338.75 $3,161,153.33 $441,371.35 $833,561.70 $1,057,659.691$1,369,905.03 $1,788,205.63 $409,180.00 $9,000.00 $8,191.35 $15,000.00 -$111,399.08 $5,000 $16,349.67 $19,409 -$120,468.93 -$129,771.59 $1,058,220.44 $297,456 $788,633.3 $9,450.0 $20,478.3 $15,000.0 -$2,864.7 $5,00 $40,874.1 $37,91 -$48,165.9 -40,280.0 $994,866.67 $1,288,240.00 $1,684,491.67 0 $9,922.50 71 $37,870.52 01 $15,000.00 0, $478,909.43 0 $5,000 7 $75,588.33, 3 $60,5471 $95,781.89, 3 $302,539.21 6 $227,302.18' $10,418.63 $56,246.40 $15,000.00, $912,433.73 $5,000 $112,266.001 $80,094 $182,486.75 $612,680.98 $418,469.36 $10,939.56 $77,774.41 $15,000.00 $1,372,947.70 $5,000 $155,235.21 $99,493 $274,589.54 $938,122.95 $582,500.55

----K-_--combine with the licensed IP with synergistic results [11]. Exclusivity can be modeled by increasing the projected market share.

In conclusion, a royalty rate of about 4.5% with a lump-sum royalty of $5000 per year seems to be a reasonable target, most likely as part of an exclusive license. However, there is uncertainty in the projections of future cash flows, and the models should be updated as more information becomes known about the product redesigns and the market.

i i i I

![Figure 3-1. US Patent 5058275, "Chisel" [12]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/14383762.506801/28.917.278.669.540.790/figure-us-patent-chisel.webp)

![Figure 3-2. German Patent Specification No. DE 3312019 [13]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/14383762.506801/29.917.289.624.600.932/figure-german-patent-specification-no-de.webp)