HAL Id: hal-01692699

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01692699

Submitted on 25 Jan 2018

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Corrosion behaviour of an assembly between an AA1370

cable and a pure copper connector for car manufacturing

applications

Rosanne Gravina, Nadine Pébère, Adrien Laurino, Christine Blanc

To cite this version:

Rosanne Gravina, Nadine Pébère, Adrien Laurino, Christine Blanc. Corrosion behaviour of an

as-sembly between an AA1370 cable and a pure copper connector for car manufacturing applications.

Corrosion Science, Elsevier, 2017, vol. 119, pp. 79-90. �10.1016/j.corsci.2017.02.022�. �hal-01692699�

O

pen

A

rchive

T

OULOUSE

A

rchive

O

uverte (

OATAO

)

OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and

makes it freely available over the web where possible.

This is an author-deposited version published in :

http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/

Eprints ID : 19370

To link to this article : DOI:

10.1016/j.corsci.2017.02.022

URL :

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2017.02.022

To cite this version :

Gravina, Rosanne and Pébère, Nadine and Laurino, Adrien and

Blanc, Christine Corrosion behaviour of an assembly between an

AA1370 cable and a pure copper connector for car manufacturing

applications. (2017) Corrosion Science, vol. 119. pp. 79-90. ISSN

0010-938X

Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent to the repository

administrator:

staff-oatao@listes-diff.inp-toulouse.fr

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Corrosion

Science

jo u r n al ho m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / c o r s c i

Corrosion

behaviour

of

an

assembly

between

an

AA1370

cable

and

a

pure

copper

connector

for

car

manufacturing

applications

Rosanne

Gravina

a,b,

Nadine

Pébère

a,

Adrien

Laurino

b,

Christine

Blanc

a,∗aCIRIMAT,UniversitédeToulouse,CNRS,INPT,UPS,ENSIACET,4alléeEmileMonso,CS44362,31030Toulouse,France bLEONIWiringSystemsFrance,5avenuedeNewton,78180Montigny-le-Bretonneux,France

Keywords: A.Aluminium A.Copper B.EIS C.Crevicecorrosion C.Pittingcorrosion

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

ThecorrosionbehaviourofanassemblybetweenanAA1370cableandapurecopperconnectorforwiring harnesseswasstudiedinneutralchlorideandsulphatecontainingsolution.Electrochemicalimpedance measurementsshowedthatthecorrosionbehaviourofthecablewascontrolledbytheingressofthe elec-trolyteinsidecablecavities.Further,localimpedancemeasurementswereperformedontwoassembly cross-sections,i.e.withandwithoutcavitiesinthealuminiumcable.Theresultsprovidedevidencefor boththegalvaniccouplingbetweenaluminiumandcopperandthepresenceofcavitiesinthealuminium cableasrelevantexplanationsforthecorrosionbehaviouroftheassembly.

©

1. Introduction

Typicalwiringharnessesintheautomotiveindustryconsistof assemblybetweenCucableandCuconnector.Today,thepressure inenvironmentalregulationsledtosearchforsolutionsgivingrise tofueleconomyandreductioninCO2emission.Inthiscontext,car

manufacturersplannedtoreducebothcostandweightofwiring harnesses.OneinnovativesolutionisthesubstitutionofCubyAl alloys,suchasAA1370,incables.Inthelastyears,severalworks concernedthemanufacturingprocessesofthisnewtypeof assem-bly.Recently,differentmethodshavebeenproposedtoproduceAl strandswithductilityandfatiguecharacteristicsreliablefor auto-motivewiringharnesses[1–4]whileultrasonicweldinghasbeen usedtojoinAlcablewithCuconnector[5,6].However,onemajor problemforwiringharnessesconcernstheircorrosionresistance because,in service,wiring harnesses are exposedto aggressive media,suchasde-icingsalt,whichcangeneratecorrosiondamage. Numerousdataarereportedintheliteratureconcerningthe cor-rosionbehaviourof1xxxAlalloys.Themainresultsconcernedthe influenceofFe-richparticleswhichactascathodicsitesand pro-motefirstdissolutionofthesurroundingmatrixandthen,pitting corrosion[7–9].However,thecorrosionbehaviourofanAlcableis morecomplex.Intheliterature,onlyfewworkshavebeenreported

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:christine.blanc@ensiacet.fr(C.Blanc).

concerningthecorrosionbehaviourofacable.XuandChen inves-tigatedthecorrosiondamageofwirespecimenspulledfromthe replacedcablesinShimenBridge[10].Theyanalysedthecorroded cablesfromthesheathbreakagetothecablecenterandexplained thattheextentofcorrosionatanypointofacablesectionwas con-trolledbyitsdistancefromthesheathbreakageduetothefluidthat couldpenetrateinsidethecable[10].IshikawaandKawakami[11]

showedthepresenceofcavitiesinsideacableduetothe incom-pletepenetrationofthesheathrubber.Then,duringexposuretoan aggressivemedium,thesolutionpenetrateintothecablecavities leadingtotheformationofaconfinedenvironment.Dependingon theconfigurationoftheharness,e.g.numberofstrandarms con-stitutiveofthecableandspacebetweenthem,andtheintrinsic corrosionbehaviourofthestrand,theconfinedelectrolyte com-positionshouldevolverapidly,e.g.,oxygenconcentration,cations concentrationandpH,andtheninduceseverecorrosion phenom-ena,suchascrevicecorrosion[12–14].ChanelandPeberestudied themechanismsgoverningthedegradationofbrass-coatedsteel cords fortyresin a 0.25M Na2SO4 solution incontact withair

andmaintainedat25◦Cbyusingelectrochemicalimpedance

spec-troscopy(EIS)[15].TheyshowedthatEISwasasuitabletechnique toquantifythecorrosionresistanceofacable[15].Moreover,the assemblybetweenanAlcableandaCuconnectorshould gener-ategalvaniccorrosionduetothedifferenceincorrosionpotential valuesbetweenthetwometalsinaqueoussolution[16–21].Khedr andLashieninvestigatedthecorrosionbehaviourofpureAlinCu2+

richsolutionsandshowedtheacceleratingeffectoftheCu2+cations

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2017.02.022

AlcorrosionrateduetoCudepositionandsubsequentgalvanic coupling[17,18].Jorcinetal.[19]showed,foramodelcouple con-stitutedofAlandCu,thechemicaldissolutionofAlduetoapH increaseattheAl/Cuinterface;thisgeneratedanoccludedzonein whichthecompositionoftheelectrolyte(a10−3MNa

2SO4

solu-tionincontactwithairandatroomtemperature)evolvedrapidly. ThegalvaniccouplingbetweenAlandCuwasalsoinvestigatedina 10mMNa2SO4solutionbyusingathin-layercellinordertomodel

theoccludedzoneinthecrevice[20].Jomaetal.performed exper-imentsina0.1MNa2SO4solutionandshowedthatthechemistry

inathin-layercellplaysasignificantroleatleastatalocalscale

[21].

The present work contributes to get a better insight of the mechanismsgoverningthedegradationofanAA1370cable/pure Cu assembly with a particular attention to the effect of the electrolyteingressinsidethecable.Conventionalelectrochemical measurements(Ecorrmeasurements,polarisationcurvesand

elec-trochemicalimpedancespectroscopy)werefirstcarriedoutforthe AA1370cableinordertoinvestigatethecorrosionbehaviourofthe cablealone.Giventhatthecablewasmadeofalargenumberof strands,theelectrochemicalmeasurementswerealsoperformed forAA1370strandstohaveabetterunderstandingofthe corro-sionmechanisms.Then,toinvestigatethecorrosionbehaviourof theAA1370cable–Cuconnectorassembly,localelectrochemical impedance(LEIS)measurementswereperformedontwo cross-sectionsof theassembly,onecross-section correspondingtoan AA1370cablewithcavitiesandtheotheronewithoutcavities.LEIS isanon-destructiveelectrochemicaltechniquethathasbeenused inrecentyearstostudylocalizedcorrosiononbimetallicsurface

[19,22–26].Itwasusedheretodeterminetheinfluenceofthe

cav-itiesintheAA1370cableafterweldingonthegalvaniccorrosion processesoccurringfortheAA1370cable/Cuconnectorassembly.

2. Experimental 2.1. Materials

TheassemblywasobtainedbyultrasonicweldingusingaDS 20-IIapparatusbetweenanAA1370(99.7%Al,0.072%Fe,0.0045%Mg, 0.045%Si;wt.%)cableandapureCu(99.90wt.%Cu;200–400ppm O2)connector.TheCuconnectorwasahotstampedCusheet.In

thefollowing,theAA1370cableintheassemblywillbereferred toas‘theAlpart’;theAA1370cable/Cuconnectorassemblywillbe referredtoasAl/Cuassembly.Duringtheweldingprocess,thecable (withoutthepolymershell)waspositionedontheCuconnectorand apressurewasexerted.Then,ultrasonicvibrationswereappliedso thatthecableandtheCuconnectormovedrelativelytooneanother withanoscillatingmovement.Thisledtoafrictionbetweenthetwo metalsandthentotheformationofaweldingzone.Thetotallength oftheweldedzonewasabout12mm.Thequalityofthewelding dependsmainlyontheappliedpressureandontheamplitudeof thevibrations.Therewasashortzone(8mm)wherethestrands constitutiveofthecablewereentirelyweldedtogethersothatthe cabledidnotrevealanycavitiesafterthewelding,thiszonebeing calledasthe‘effectiveweldedzone’.

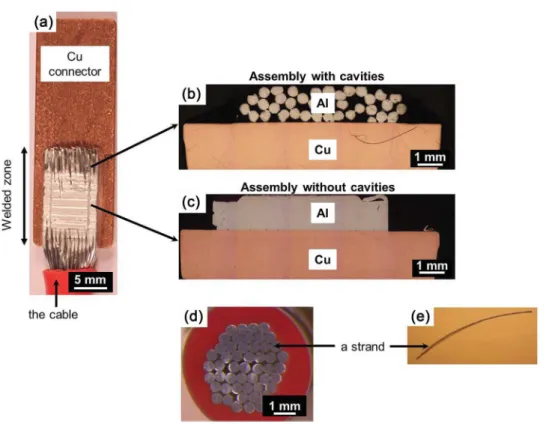

Thegalvanic couplingat theAl/Cu interfacewas studiedby electrochemicalmeasurementsperformedontwocross-sections oftheassembly.Fig.1ashows aglobalpictureoftheassembly. Thetwoselectedcross-sectionsareshowninFig.1bandc.Oneof thecross-sectionswasremovedfromaporouszoneofthecable due tothe fact that thestrands constitutive of the cablewere not entirelyweldedtogether (henceforthcalled ‘assemblywith cavities’)(Fig.1b).Anothercross-sectionwasremovedfromthe effectiveweldedzonewherenocavitieswereobservedbetween theweldedstrands(henceforthcalled‘assemblywithoutcavities’)

(Fig.1c).Beforecorrosiontests,thecross-sectionswereembedded inanepoxy-resinwithoutfillingthecavities.Thiswasachievedby embeddingthecross-sectionsinaparafilmshell.

Fora betterunderstandingofthecorrosionbehaviourofthe assembly, electrochemical measurements were also performed forcross-sectionsofboththeAA1370cablebeforewelding and AA1370strandsconstitutiveofthecable.Thecross-sectionswere perpendiculartothecable/strandaxis.Thecablewasanassembly of50strands(0.52mmdiameter)protectedbyaplastic insulat-ingsleeve.Fig.1dshowsanopticalobservationofacross-section ofacablewhere the50strandscanbeobserved.Itcanbeseen that thespacebetweenthestrands isnot uniform. Toperform theelectrochemicalmeasurements,thecablewasembeddedin anepoxy-resinwithoutfillingthespacebetweenthestrands(see theprocedurefortheassembly).Ifonlythesurface perpendicu-lartothecableaxiswastakenintoaccount,thesurfaceareaof thecross-sectionofthecablewith50strandsexposedtothe elec-trolyteduringtheelectrochemicalexperimentswas0.11cm2.To

studythecorrosionbehaviourofastrand,thedifficultywasits diameter,i.e.0.52mm.Threeelectrodeswerepreparedwiththe cross-sectionsof1strand(S=0.002cm2),4strands(S=0.008cm2)

and22 strands(S=0.047cm2)respectivelyexposed tothe

elec-trolyte.Forthe3electrodes,thestrandswereorganizedtoobtaina regulararrangementoftheircross-sections(theaxisofeach indi-vidualstrandbeingparalleltotheothers)andembeddedtogether inanepoxy-resin.Allthecavitiesbetweenthestrandswerefilled bytheepoxy-resin.Preliminaryexperimentsshowedthatsimilar resultswereobtainedforthe3electrodes.However,the repro-ducibilityofthemeasurementswasbetterfortheelectrodewith 22strandsduetothefactthatthesurfacewasmorerepresentative ofthealloymicrostructure.Inthefollowing,forbrevity,onlythe resultsfortheelectrodewith22strandsarepresented.This elec-trodewasreferredtoas‘strandsample’.Itcouldbenotedherethat thecorrosionbehaviourofthestrandsamplecouldbeconsidered representativeofthebehaviourofacableforwhichthecavities wouldbesealed.Electrochemical measurementswerealso per-formedforaCusampletakenoffaconnectorusedfortheassembly; thesurfaceexposedtotheelectrolytewas0.11cm2.

Beforeallelectrochemicaltests,thesurfaceofthespecimens wasmechanicallyabradedwithsuccessivegritSiCpapers(1200, 2400)andthenpolishedfrom6to1mmgradewithdiamondpaste anddeionisedwateraslubricant.

2.2. Electrochemicalmeasurements

Allelectrochemicalmeasurementswereperformedinsulphate and/orchloride-containingsolutions;theyareassumedtobe rep-resentativeoftheautomotiveenvironments.Severalauthorshave usedsulphateand/orchloride-containingsolutionstostudyAl/Cu galvaniccouplingallowingtheresultsobtainedinthisworktobe comparedwiththeirresults[20,21].Fortheconventional electro-chemicalmeasurements(Ecorrmeasurements,polarizationcurves

andimpedancemeasurements),thecorrosivemedium(pH=6.5) waspreparedfromdeionisedwaterbyadding0.1MNa2SO4 and

asmallconcentrationofchloride(0.001MNaCl).ForLEIS experi-ments,a0.001MNaClsolution(pH=6.5)preparedfromdeionised water was chosen to maintain a low conductivity required to optimize the measurements in the low-frequency range [27]. Theelectrolyte wasmaintained ata temperatureof 25◦C±1◦C

exceptfortheLEISmeasurementsperformedatroomtemperature (22◦C±1◦C).

Fortheconventionalelectrochemicalmeasurements,the exper-imentalset-upconsistedofathree-electrodecell,connectedtoa BiologicVSPapparatus,withalargeplatinumelectrodeusedas counterelectrodeandasaturatedcalomelelectrode(SCE)as ref-erenceelectrode.Specimensusedastheworkingelectrodewere

Fig.1.(a)GlobalviewoftheassemblybetweenAA1370cableandpureCuconnector;cross-sectionsoftheassemblies(b)withand(c)withoutcavities;(d)theAA1370cable and(e)astrand.

thestrandsampleandthecable.Forthetwocross-sectionsofthe assembly,onlyEcorrwasmeasuredforexposuretimestothe

elec-trolyterangingfrom1hto168h.In thefigures,meanvaluesof Ecorr aregivenonthebasisof atleasttenexperimentsforeach

experimentalcondition.Forthepolarizationcurves,thesamples werefirstexposedtotheelectrolyteatEcorrfor3handthen,the

anodicandcathodicpartswereobtainedindependentlyfromEcorr

atapotentialsweeprateof0.07mVs−1.Foreachsample,atleast

threecurveswereplottedtocheckthereproducibility.Impedance measurementswereperformedunderpotentiostaticconditionsat Ecorrwitha15mVpeak-to-peaksinusoidalperturbation.Frequency

wassweptdownwardsfrom65kHzto3mHzwith9pointsper decade.Severalimpedancediagramswererecordedasafunction oftimerangingfrom3hto168h.Allimpedancemeasurements wererepeatedthreetimestocheckthereproducibility.

The corrosion behaviourof the Al/Cu assembly wasstudied bylocalelectrochemicalimpedancespectroscopy(LEIS).The mea-surementswerecarriedoutwithaSolartron1287Electrochemical Interface,a Solartron1255B frequencyanalyser anda Scanning Electrochemical WorkstationModel 370(Uniscan Instruments). Thismethodusedafive-electrodeconfiguration.Theprobe(i.e., abi-electrodeallowinglocalcurrentdensitymeasurements)was steppedacrossaselectedareaofthesample.Theanalysed part had anareaof 8mm×14mmandthestepsizewas500mmin thexandydirections.Mapswereobtainedatafixedfrequency, choseninthepresentcaseat10Hz,andadmittancewasplotted ratherthanimpedancetoimprovethevisualizationoftheresult

[28].Localimpedancediagramswererecordedoverafrequency rangeof65kHz–3Hzwith8pointsperdecade.Spectrawere plot-tedforthe2cross-sectionsoftheassemblyshowninFig.1bandc fromtheCuparttotheAlpartwiththeoriginofaxisbeingtheAl/Cu interface.Thetimetorecordallthelocalimpedancediagramswas lowerthan60min.ForalltheLEISmeasurements,thespatial reso-lutionwasabout1mm2,i.e.theanalysedsurfacewasabout1mm2

whenalocalimpedancediagramwasplotted[27].Fortheassembly

withcavities(Fig.1b),thecavitiescorrespondedto20%ofthe ana-lysedsurfacesothattheeffectivemetallicsurfacewasonly80%of theanalysedsurface(analysisperformedonthecross-section per-pendiculartothecableaxis).Inthefollowing,forLEISresults,the impedancevalues(incm2)arenotcorrected.Therefore,forthe

assemblywithcavities,theimpedancevaluesareoverestimated withanerrorofabout20%ifonlythesurfaceexposedtothebulk solutionistakenintoaccount.

2.3. Surfacecharacterization

AA1370surfaceswereobservedbeforeandafterthe electro-chemicaltestsbyusingaNikonEclipseMA200opticalmicroscope (OM).ALeo435VPscanningelectronmicroscope(SEM)wasused tovisualizetheAl/Cuassemblyafterdifferentexposuretimesto theelectrolyticsolutionandtoobtainabetterdescriptionofthe corrosionmorphology,particularlyattheAl/Cuinterface.Forall theobservations,thesampleswereremovedfromtheelectrolyte aftertheelectrochemicaltests,rinsedwithdeionised waterand thenair-dried.

3. Experimentalresultsanddiscussion

First, the corrosion behaviour of the cable, as compared to the strand sample, was studied by combining stationary and impedancemeasurements.Then,attentionwaspaidtothe corro-sionbehaviouroftheAl/Cuassembly.

3.1. ElectrochemicalbehaviouroftheAA1370cable

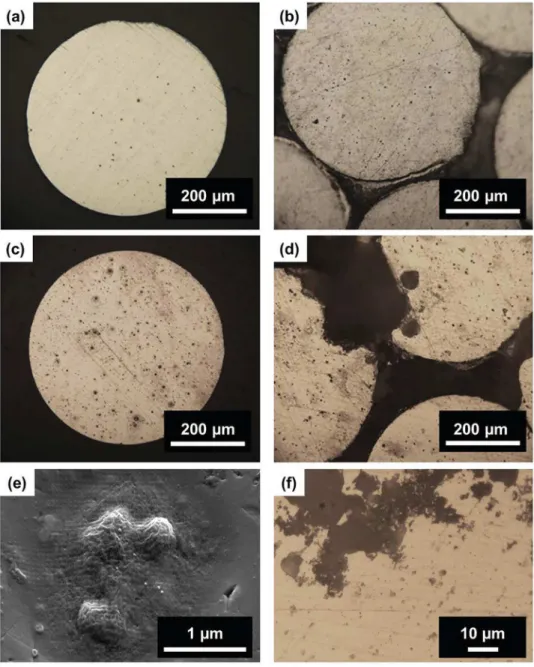

Fig.2showsOMobservationsofastrandandofthecableafter twoexposuretimes(3hand168h)totheaggressivesolutionat theircorrosionpotential.Forbothsamples,aweakdissolutionof thematrixaroundtheFe-richparticles,identifiedasAl3Fe

Fig.2.Opticalmicroscope(OM)observationsofthestrandandofthecableafter:(a,b)3hofimmersionand(c,d)168hofimmersionatEcorrin0.1MNa2SO4+0.001MNaCl. (a)and(c)correspondtothestrand,(b)and(d)tothecable.(e)SEMobservationofcorrosionphenomenaoccurringattheAl3Feintermetallicparticles.(f)close-uponthe corrosionfilamentsobserved.

bshowedthatafter3hthematrixdissolutionaroundthe inter-metallicparticleswasmoreextendedforthecablethanforthe strand.After168hofimmersion(Fig.2candd),asignificant dis-solutionofthematrixaroundtheFe-richparticles(Fig.2e)canbe seenonthewholesurfaceforbothsamples,andinaddition,for thecable,largepitssurroundedbyfinefilaments(Fig.2f)werealso observedattheperipheryofthestrands.Thesecorrosionfeatures, inagreementwithliteraturedata,accountedforthepenetration oftheelectrolyteinsidethecableleadingtoaconfinedmedium andcrevicecorrosion phenomenon[10,11].OMobservations of cross-sections parallel to the cable axisafter various exposure timestothechloride-containingsulphatesolutioncorroborated thisassumptionandallowedthedepthofthecorrodedzoneto bemeasured(Fig.3a).Itwasassumedtobeagoodindicationof theelectrolytepenetrationdepth.Inordertomeasurethedepthof thecorrodedzone,thecorrosiondamagewasenhancedby polar-izingat−700mV/SCEfor5minthesamplesaftertheexposureat Ecorr(Fig.3aandb).Theelectrolytepenetrationdepthwasfoundto

becomerapidlyindependentoftheexposuretime,reachingabout 800mmafter3hofexposure(Fig.3c).

Fig.4 reports Ecorr values versus exposuretime tothe

elec-trolyteforthestrandsampleandthecable.Forthestrandsample, Ecorr stabilized rapidly and an almost stationary value(around

−600mV/SCE)wasobtainedafter3hofimmersion.Onthe con-trary, for the cable, Ecorr decreased significantly towards more

negativevaluesduringimmersionwhichwasinagreementwith thedifferencesincorrosionmorphologyobservedbetweenthetwo samples(Fig.2).Fig.5showsthepolarizationcurvesforthestrand sampleandthecableobtainedafter3hofexposuretothe chloride-containingsulphatesolution.Forthecable,thecurrentdensities werecalculatedbytakingintoaccount(i)onlythecross-sections ofthe50 strands constitutiveof thecable,i.e.only thesurface exposedtothebulksolution(S=0.11cm2,nocorrectedsurfacein

Fig.5)and(ii)boththecross-sectionsandthelateralsurfaceof the50strandsona800mmdepth,i.e.boththesurfacesexposed tothebulkand toaconfinedelectrolyte(S=0.76cm2,corrected

Fig.3.(a)OMobservationofacablecross-section(paralleltothecableaxis)after3hofexposuretothe0.1MNa2SO4+0.001MNaClsolutionfollowedbypolarizationfor 5minat−700mV/SCE;(b)close-uponacorrodedstrandinsidethecable;(c)electrolytepenetrationdepthversustheexposuretime.

Fig.4.VariationofEcorrduringimmersionin0.1MNa2SO4+0.001MNaClforthe strandsampleandthecable.

Fig.5.Polarizationcurvesofthestrandsampleandthecableobtainedafter3h ofimmersionatEcorrin0.1MNa2SO4+0.001MNaCl.Scanrate=0.07mVs−1.For thecable,thecurve‘nocorrectedsurface’onlytakesintoaccountthecablesurface exposedtothebulk(S=0.11cm2);the‘correctedsurface’curvetakesintoaccount boththesurfaceexposedtothebulkandthatexposedtotheconfinedmedium insidethecavities(S=0.76cm2).

surfaceinFig.5).Forboththestrandsampleandthecable,the cathodicbranch,correspondingmainlytotheoxygenreduction, wassimilar.Forthestrandsampleandthecable,Ecorrvalueswere

−580mV/SCEand−730mV/SCErespectively.Theanodicdomain wascharacterizedforthestrandsample bya passivityplateau, withpassivecurrentdensitiesofabout4.10−4mAcm−2,followed

byabreakdownpotentialat500mV/SCEassociatedwith,first,a slowincreaseoftheanodiccurrentdensitiesandthenasharper one.Thiscouldbeassociatedto,first,anincreaseofthe dissolu-tionrateofthematrixsurroundingtheFe-richparticlesandthen topittingcorrosion.Besides,thesignificantcurrentfluctuations observedafterthesharpincreaseofthecurrentdensities consti-tutesacharacteristicfeatureofthepittingcorrosion.Forthecable, ashortpseudo-plateauwasobservedandtheanodiccurrent densi-tieswereabout2.10−3mAcm−2(correctedsurface).Whateverthe

surfacetakenintoaccount,thecurrentdensitieswerehigherforthe cable,ascomparedtothestrandsample;thiscouldbeassignedto adissolutionprocessratherthanapassivityprocess.Abreakdown potentialwasthenobservedat−550mV/SCEfollowedbyasharp increaseoftheanodiccurrentdensities.Alltheresultsshoweda lowercorrosionresistanceforthecableascomparedtothestrand sample.Thedifferencesincorrosionbehaviourbetweenthetwo sampleswererelatedtothepenetrationoftheelectrolyteinsidethe cablecavitiesleadingtotheformationofaconfinedandthenmore aggressiveelectrolyte.Thisconfirmed,forthecable,theoccurrence ofbothpittingcorrosiononthesurfaceexposedtothebulk solu-tionandcrevicecorrosiononthesurfaceexposedtotheconfined mediuminside thecavities. Thehigheranodiccurrentdensities observedforthecablewererelatedtotheprogressive modifica-tionoftheelectrolytetrappedinsidethecavitiesandsubsequent dissolutionphenomenon.

Impedance measurements were performed for the strand sampleandthecableafterdifferentexposuretimestothe chloride-containingsulphatesolution.Fig.6showsthediagramsinBode (Fig.6a) and Nyquist (Fig. 6b) coordinates for thestrand sam-ple. After3hand 24h of immersion, the impedance diagrams arecharacterizedbytwotimeconstants.Thefirsttimeconstant (60kHz–1Hz)wasassociatedtotheresponseofthepassivefilm, whilethesecondtimeconstant(1Hz–100mHz)wasattributedto thechargetransferprocessand totheoxygenreductiononthe passivefilminagreementwithliterature[27].Impedance mea-surementsperformedatEcorrinadeaeratedelectrolyte(resultsnot

Fig.6.Electrochemicalimpedancediagramsobtainedforthestrandsample–(a) Bodeand(b)Nyquistcoordinates–afterdifferentexposuretimesatEcorrto0.1M Na2SO4+0.001MNaCl.

at low frequencies and no modification in the high frequency domain.Thisconfirmedtheattributionofthelowfrequencytime constanttotheoxygenreduction.After168hofimmersion,the impedancediagramshowedonlyonetimeconstantwithalower resistancewhichcouldbeassociatedtothecorrosionofthealloy, i.e.tothechargetransferprocess.Suchanevolutionofthediagrams wasinagreementwiththeOMobservations(Fig.2c),i.e.the disso-lutionofthematrixsurroundingtheFe-richparticlesduetooxygen reductionontheintermetallicsand subsequentalcalinizationof theelectrolyte for increasingimmersion times. The impedance diagramsobtainedforthecable(Fig.7)wereclearlymodifiedas compared tothose obtainedfor the strandsample. Theresults arepresented by takinginto account thetotal surface exposed totheelectrolyte(the surfaceexposedtothebulksolutionand thatexposedtotheconfinedmediumtrappedinsidethecavities). TheNyquistdiagram(Fig.7b)wasconstitutedbyastraightlinein thehigh-frequencydomainfollowedbyasemicircle.Thistypical shapecanbeassociatedtotheoxygendiffusioninaporoussystem

[30–33]inagreementwiththepenetrationoftheelectrolyteinside

thecablecavities.Theflattenedsemicirclemayoriginatefromthe cavityshape [34].Theimpedancevalues forthecablewereten timessmallerthanthoseobtainedforthestrandsamplein agree-mentwiththedifferencesincorrosiondamagebetweenthetwo sampleswhichhighlightedtheinfluenceoftheelectrolyte pene-trationthroughthecavitiesofthecable.For168hofimmersion,a decreaseoftheimpedancewasobservedand,inthehigh-frequency domain,atimeconstantappearedwhichcouldbeassociatedtothe corrosionofthealloyintheconfinedmedium[35,36].Additional experiments(results notshown) wereperformedwitha cross-sectionofthecableforwhichthecavitieshadbeensealedwitha resinbyforcingtheresintopenetrateintothecavitieswitha vac-uumsystem.Theimpedancediagramobtainedforthecablewith sealedcavitiesafterimmersionintheaggressivesolutionandthat ofthestrandsampleweresuperimposed.Thiswasinagreement withcommentsintheexperimentalpartandconfirmedthatthe corrosionbehaviourofthecablewascontrolledbythepenetration oftheelectrolyteinsidethecable.

Fig.7.Electrochemicalimpedancediagramsobtainedforthecable–(a)Bode and(b)Nyquistcoordinates–after differentexposuretimesatEcorr to0.1M Na2SO4+0.001MNaCl.Theimpedancevaluestakeintoaccountboththesurface exposedtothebulkandthatexposedtotheconfinedmediuminsidethecavities (S=0.76cm2).

Equivalent electrical circuits are frequently used to extract parametersassociatedwiththeimpedancediagrams.Inthepresent study,thedifferentsetsofimpedancemeasurementsperformed allowedtheinterpretationofthedifferenttimeconstantsin agree-mentwithliteraturedataandrelevantparametersweredefined. Forthestrandsample,relevantparametersweretheoxidefilm resistance(Rox)andthechargetransferresistance(Rt).Theywere

directlymeasuredontheimpedancespectra.Further,among rel-evantparameters,aconstant phaseelement(CPE)isoftenused insteadofa capacitance totakethenon-ideal behaviourofthe interfaceintoaccount.TheCPEisgivenby:

ZCPE=

1

Q (jω)˛ (1)

where ais related to theangle ofrotation of a purely capaci-tivelineonthecomplexplaneplotsandQisin−1cm−2s˛.In

thepresentstudy,aandQweredeterminedusingthegraphical methodproposedbyOrazemetal.[37].Forthecable, consider-ingthecomplexityofaporoussystem,thepolarizationresistance (Rp)wasassumedtoallowthecorrosionresistanceofthecableto

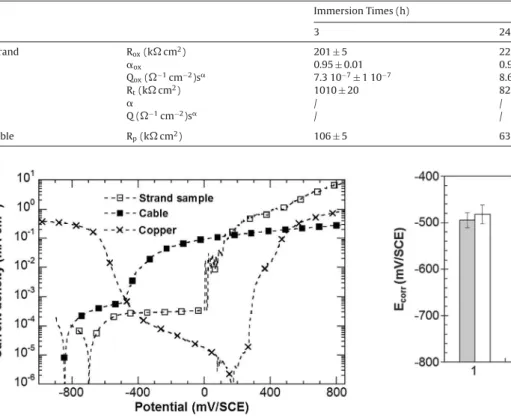

becomparedtothatofthestrandsample.Fig.7ashowedthatthe impedancemoduluswasquitestableforfrequencieslowerthan 10mHz;therefore,theimpedanceatlowfrequency(3mHz)was measuredandusedtoevaluatethecorrosionresistanceofthecable. TheimpedanceparametersarereportedinTable1.

Forthestrandsample,duringthefirst24hofimmersion,aox

remainedconstantandequal to0.95. ThevaluesofQox slightly

increasedfrom7.310−7−1cm−2s0.95to8.610−7−1cm−2s0.95.

Theaox andQox valuesaccountedforthepresenceofapassive

layer.ThevariationofQoxwithincreasingimmersiontimecould

berelatedtotheevolutionofthethicknessand/orofthe chemi-calcompositionofthepassivefilminrelationwiththedissolution ofthematrixaroundtheintermetallics.Duringthefirst24h,the

85

Table1

Parametersobtainedfromtheimpedancediagramsforthestrandsampleandforthecableafterdifferentimmersiontimesin0.1MNa2SO4+0.001MNaClsolution.Forthe cable,theimpedancevaluestakeintoaccountboththesurfaceexposedtothebulkandthatexposedtotheconfinedmediuminsidethecavities(S=0.76cm2).

ImmersionTimes(h) 3 24 168 Strand Rox(kcm2) 201±5 220±5 / aox 0.95±0.01 0.95±0.01 / Qox(−1cm−2)sa 7.310−7±110−7 8.610−7±110−7 / Rt(kcm2) 1010±20 821±10 324±5 a / / 0.94±0.01 Q(−1cm−2)sa / / 4.2510−6±110−6 Cable Rp(kcm2) 106±5 63±5 27±2

Fig.8. PolarizationcurvesoftheAA1370strandsample,theAA1370cableandthe pureCuconnectorafter3hofimmersionatEcorrin0.001MNaClsolution.

corrosionbehaviourofthestrandsamplewascontrolledbythe presenceof theoxidefilmwithhighvaluesof bothRox andRt

while,for168hofimmersion,theelectrochemicalbehaviourwas controlledbythecorrosionprocesses(decreaseoftheRtvalues).

Forthecable,thelowRpvalueswereinagreementwiththelow

corrosionresistanceofthecableascomparedtothestrand sam-ple;moreover,thedecreaseofRpwithincreasingimmersiontime

wasinagreementwiththeextentofthecorrosiondamagerelated tothepenetrationoftheelectrolyteinsidethecableandtothe crevicecorrosionphenomenaonthesurfaceexposedtothe con-finedmediumwhilepittingoccurredonthesurfaceexposedtothe bulk.

3.2. Electrochemicalbehaviouroftheassembly 3.2.1. Preliminaryexperimentsandobservations

Apreliminarystudywasperformedin0.001MNaClto charac-terizeseparatelythecorrosionbehaviourofAl(i.e.AA1370)andCu inthesamesolutionasthatusedfortheLEISmeasurements.First, theanodicbranchofthepolarizationcurvesfor theAlsamples (strandsampleandcable)andthecathodicandanodicbranches forpureCuwereobtained(Fig.8).ComparisonofFigs.5 and8

showedthattheglobalshapeofthecurvesfortheAlsampleswas thesameindependentlyoftheelectrolyte.Forthestrandsample, a600mV-longplateaucorrespondingtoapassivityplateauwith lowanodiccurrentdensities(3.10−4mAcm−2)wasobservedand

followedbyanabruptincreaseofthecurrentassociatedtopitting corrosion.Forthecable,aplateauwasalsoobserved;itwas bet-terdefinedthaninsulphateandchloride-containingsolutionsbut, again,correspondedtohigheranodiccurrentdensitiesthanforthe strandsampleandwasconsideredasapseudo-passivityplateau. Itwasrapidlyfollowedbyasharpincreaseoftheanodiccurrent densitiesassociatedtobothpittingandcrevicecorrosionas

previ-Fig.9. VariationofEcorrduringimmersionin0.001MNaClsolutionfortheAl/Cu assemblieswithandwithoutcavities.

ouslyexplained.Asobservedinthechloride-containingsulphate solution,thebreakdownpotentialassociatedtotheincreaseofthe anodiccurrentdensitieswasmorenegativeforthecable(pitting andcrevicecorrosion)thanforthestrandsample(pitting corro-sion) whichshowedthelowercorrosionresistanceof thecable ascomparedtothestrandsample.Inthe0.001MNaClsolution, thebreakdownpotentialwas10mV/SCEand−500mV/SCEforthe strandsampleandthecable,respectively.Then,itcanbeseenfrom

Fig.8thatthecorrosionpotentialofpureCuwasmorepositive (200mV/SCE)thanthoseofthestrandsample(−700mV/SCE)and thecable(−850mV/SCE)showingasexpectedthat,intheAl/Cu assembly,pureCuwillbethecathodeandtheAlsampleswillbe theanode[20,21,38–40].FromtheanodiccurvesoftheAlsamples andthecathodiccurveofCu,thecommonpotentialmeasured,in thecaseofagalvaniccouplingbetweenthetwometalswiththe samesurfacearea,wouldbeabout−400mV/SCEforanAlstrand sample/Cuassembly,and−500mV/SCEforanAlcable/Cu assem-bly.Itwasworthnoticingthat,fortheassembliesinvestigatedhere andasshowninFig.1,theratioSCu/SAl(SCuandSAlarethesurface

areasexposedtotheelectrolyteintheassemblyrespectivelyfor CuandAl)wassignificantlyhigherthan1.Therefore,thecommon potentialshouldbeshiftedtowardsmorepositivevaluesthanthose previouslyestimated(withthesamesurfacearea).FromFig.8,it canbeclearlyseenthat,in0.001MNaCl,thecommonpotentialwas inthelocalizedcorrosion(pittingandcrevicecorrosion)regimefor thecable,whereas,dependingontheratioSCu/SAl,itcouldbeinthe

passiveregimeforthestrandsample.Thismeantthatasevere cor-rosiondamagewasexpectedforthecablewhencoupledwithCu. Thissuggestedalsothatdifferencesshouldbeobservedbetween thetwotypesofassembly,i.e.withandwithout(allthestrands con-stitutiveofthecablebeingweldedtogether)cavities,asdescribed inFig.1.

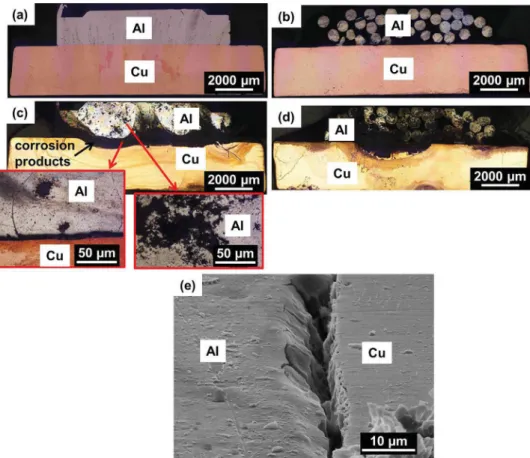

Fig.10.OpticalmicroscopeobservationsofthecorrosiondamagefortheAl/Cuassembliesafter(a,b)3hand(c,d)168hofimmersionatEcorrina0.001MNaClsolution: assembly(a,c)withoutand(b,d)withcavities.(e)SEMmicrographoftheAl/Cuinterfaceoftheassemblywithoutcavitiesafter24hofimmersionin0.001MNaClsolution (tiltof70◦).

Fig.9showedEcorr valuesversusimmersiontime in0.001M

NaClforthetwotypesofassembly.Asexpected,Ecorrvalueswere

betweenthoseoftheAlcableandCu.Forbothassemblies,Ecorr

valuesdecreasedwithincreasingimmersiontimewhichcouldbe relatedtocorrosiondamage.Duringthefirst24h,Ecorrvalueswere

thesameforthetwotypesof assembly;theydecreasedslowly from−500mV/SCEto−600mV/SCE.After24hofimmersion,Ecorr

oftheassemblywithoutcavitiesstabilizedaround−600mV/SCE, whereas,fortheassemblywithcavities,Ecorrmovedtowardsmore

negativevaluesandreached−770mV/SCEafter168hof immer-sion.ThisvariationofEcorrsuggestedthat,foranimmersiontime

longerthan24h, thecorrosiondamage wasmoreextended for theassemblywithcavitiesandunderlined,asalreadydiscussed, thatthepresenceofcavitiesinthecablemodifiedthecorrosion processes.

The corrosiondamages for thetwo types of assembly were observedbyOMandSEMaftershortimmersiontimes(3hand24h) andlongimmersiontime(168h)in0.001MNaCl(Fig.10;results areonlygivenfor3hand168h).Independentlyoftheimmersion time,AlpartwascorrodedwhiletheCusurface exposedtothe bulksolutionremainedsafe.Forashortimmersiontime,no signif-icantdifferencewasobservedbetweenthetwotypesofassembly (Fig.10aandb).After168hofimmersion,significantdifferences wereobservedfortheAlpartdependingonthepresenceornot ofcavities(Fig.10candd).Fortheassemblywithoutcavities,OM observationsshowedthepresenceofpitsandnumerousfine fila-mentsaroundthepitsfortheAlpart(Fig.10c).Fortheassembly withcavities,aseverecorrosiondamageoftheAlpartwasobserved withnot onlypitsobservedonthesurfaceexposedtothebulk solutionbutalsosomestrandsconstitutiveofthecablecompletely dissolvedoverseveralhundredsofmicrometersindepth.These

corrosionfeatureswereinagreementwithpittingcorrosion phe-nomenaoccurringonthesurfaceexposedtothebulksolutionwhile crevicecorrosionoccurredinthecavities[38].Moredetailed atten-tionwaspaidtotheAl-Cuinterface.Forbothassemblies,corrosion products(blackareasinFig.10candd)wereclearlyobservedatthe Al/CuinterfaceandspreadallovertheAlpartfortheassemblywith cavities(Fig.10d).Fig.10eshowsaSEMmicrographoftheAl/Cu interfaceafter24hofimmersionfortheassemblywithout cavi-ties.AttheAl/Cuinterface,acrevicewasclearlyvisibleandalsothe Aldissolution.Suchacrevicewasalsoobservedfortheassembly withcavities:itwasevenmorevisible.Similarfeaturewasalready observedforaAl/Cumodelcouple[19].ThisshowedthatforCu, eventhoughnocorrosiondamagewasobservedonthesurface exposedtothebulksolution,corrosionphenomenaoccurredon theverticalwallinsidethecrevice,referringtocrevicecorrosion processes[20,21].Thus,forbothassemblies,theinitialstepofthe corrosionprocesswasthedissolutionoftheAlpartattheAl/Cu interfaceduetothealkalinisationlinkedtotheoxygenreduction reactionontheCupart[19].Theelectrochemicalreactionsthat justifythealuminiumcorrosionwereasfollows[38,40–42]:

Cathodic(ontheCusurfaceexposedtothebulksolution):

O2+2H2O+4e−→4OH− (2)

Anodic:

Al→ Al3++3e− (3)

2Al+6H20 →2Al(OH)3+3H2 (4)

Al(OH)3+OH−→ [Al(OH)4]− (5)

With increasing immersion time, in the crevice, hydrolysis of cationscan beassumed and asa consequencethe chemical

Fig.11. Admittancemapsobtainedafter24hofimmersionatEcorrin0.001MNaCl solutionat10HzabovetheAl/Cuassemblies:(a)withoutcavitiesand(b)with cav-ities.Admittancevaluesarecalculatedtakingintoaccountananalyzedsurfaceof 1mm2.

compositionoftheelectrolyteattheAl/Cuinterfaceshouldvary significantlywithadecreaseofpHasshownbyShietal.[40].This canbeascribedtothereactionofAldissolutionandhydrolysis[40]: Al+nH2O→Al(OH)n3−n+nH++3e−,n=1–3 (6)

Therefore,inthecreviceformedattheAl/Cuinterface,thepH gotmore acidicwhichshouldpromoteacrevicecorrosion phe-nomenonforCu.Ontheopposite,farfromtheAl/Cuinterface,Cu wasincontactwiththebulksolutionwhereoxygenispresent[21]

leadingtoanon-corrodedsurface.FortheAlpart,fortheassembly withoutcavities,pittingcorrosionwasobserved.Concerningthe assemblywithcavities,pittingcorrosionwasobservedontheAl surfaceexposedtothebulksolutionandcrevicecorrosionoccurred inthecavitiesexistingbetweenthestrandsduetothe penetra-tionoftheelectrolyteinsidethecavities.Therefore,thecorrosion productsobservedshouldincludebothcopperoxides,aluminium oxidesandhydroxides[20,38,40,42].Håkanssonetal.showedthat themaincorrosionproductsformedduringgalvaniccorrosionof aluminium/carbonsystemsin0.6MNaClwasAl(OH)3,presented

asagelatinoussubstanceinthecrevicesbetweentheAlwires[43]. TheseauthorsalsoshowedthatAl(OH)3shouldcontroltherateof

thecorrosionprocesseswhichshouldexplaintheplateauobserved onthepolarizationcurvesforthecableafterthebreakdown poten-tial(Fig.8).

3.2.2. LEISstudyoftheassemblies

LEISwasfirstusedinmappingmode.Mapsobtainedat10Hzfor theassemblieswithandwithoutcavities,after24hofexposurein a0.001MNaClsolutionareshowninFig.11.Forbothsamples,the admittancevaluesarehigher(i.e.,lowerresistance)ontheAlpart whichwasduetothegalvaniccouplingbetweenAl(anode)and Cu(cathode).Moreover,heterogeneousvaluesoftheadmittance

wereobservedontheAlpartinaccordancewithpittingcorrosion processes,aspreviouslyshown.ComparisonofFig.11aandbdid notshowsignificantdifferencesbetweenthetwotypesofassembly inagreementwithEcorrmeasurements(Fig.9).

Then, localimpedance spectrawerecollected after24hand 168hofimmersionforthetwotypesofassembly(Fig.12,Nyquist coordinates).

First,itcanbeseenthatimpedancevaluesontheAlpartfor theassemblywithcavitiesarehigherthanthosefortheassembly withoutcavities.Asexplainedintheexperimentalpart,impedance valuesontheAlpartareoverestimatedfortheassemblywith cavi-ties.Theerroronthemeasurementswasestimatedtobeabout20% byconsideringonlythesurfaceexposedtothebulksolution.Ifthe surfaceexposedtotheconfinedelectrolyteinthecavities (consid-eringthesurfaceintheplaneparalleltothecableaxis)istakeninto account,thiserrorshouldbereducedbecausetheexposedsurface wouldbeincreased.Nevertheless,despitetheseinaccurate mea-surements,itwashelpful,forbothAl/Cuassemblies,tostudythe changesobservedforthelocalimpedancediagramsversus immer-siontimeandtocomparetheelectrochemicalresponseoftheAl partandtheCuparttodescribetheinfluenceofthecavitiesonthe corrosionbehaviouroftheAl/Cuassembly.

Then,forbothassemblies,theimpedancevaluesafter24hof immersion (Fig. 12a and b) were higher on the Cu part, then decreasedwhentheprobemovedtowardstheAl/Cuinterface,and decreasedagainwhentheprobewasovertheAlpart.Suchan evo-lutionoftheimpedanceasafunctionofthepositionoftheprobe wasinagreementwiththegalvaniccouplingbetweenAlandCu. After24hofimmersion,pittingcorrosionoccurredontheAlpart (Fig.10).Fortheassemblywithcavities,thediagramsplottedfor theCupart(redcurves inFig.12)aresignificantlymodified in thelowfrequencyrange ascomparedtothoseobtainedforthe assemblywithoutcavities.Theirglobalshapesuggesteda diffusion-controlledelectrochemicalprocess inrelationwiththecathodic reactionofoxygenreductionontheCupart.After168hof immer-sion,thediffusion-controlledprocesswasevenmoremarkedon thediagramsfortheassemblywithcavities(Fig.12d)andcouldbe alsonotedfortheassemblywithoutcavities(Fig.12c).This conclu-sioncouldberelatedtothoseofHåkanssonetal.whoshowedthat, foraAl/carboncouple,theratecontrollingmechanismwassolely themasstransportofoxygenthroughthegelatinousAl(OH)3inside

thecrevice[43].

In order to quantitatively analyse the LEIS diagrams, three parametersweregraphicallyextracted:theCPEvalues(aandQ) andthevaluesoftheimpedancemodulusat1Hz(|Z|1Hz).Fig.13

showsthevariationoftheseparametersforeachdiagramobtained overtheAlandCuparts.Independentlyoftheassemblyandof theimmersiontime,|Z|1HzvaluesfortheCupartwerehigherthan

thosefortheAlpart,whichconfirmedthedifferencesin reactiv-ity betweenthetwo metals whentheywerecoupled(Fig.13a, d).On theCupart,thelow frequency rangewasrelated tothe diffusionprocesslinkedtotheoxygenreduction(Fig.12). What-evertheassembly,theincreaseof|Z|1Hzbetween24hand168hof

immersionwasingoodagreementwiththeshiftofthecorrosion potentialsmeasuredfortheassembliestowardsmoreandmore negativevaluesfrom24hto168hofimmersion(Fig.9):thiswas linkedtoamoreandmoresignificantcathodicpolarizationforthe Cupart.Whentheimmersiontimeincreased,inagreementwith thecorrosionpotentialvalues measuredforthetwoassemblies, thedifferencesin|Z|1HzvaluesbetweentheAlandCupartswere

evenmoremarkedfortheassemblywithcavities.After168hof immersion,|Z|1HzvaluesmeasuredontheAlpartfortheassembly

withcavitieswerelowerthanthoseoftheAlpartforthe assem-blywithoutcavities.Thiswasexplainedbytakingintoaccountthe increaseoftheelectrochemicalprocessesina confinedmedium previouslyshowedforthecable:theeffectofthegalvaniccoupling

Fig.12.Localimpedancespectraobtainedafter(a,b)24hand(c,d)168hofimmersionatEcorrin0.001MNaClsolutionfordifferentpositionsofthebi-electrodeabovethe Al/Cuassemblies:(a,c)withoutcavitiesand(b,d)withcavities.Impedancevaluesarecalculatedtakingintoaccountananalyzedsurfaceof1mm2.

Fig.13. Variationoftheparameters((a)and(d)|Z|1Hz,(b)and(e)aand(c)and(f)Q)obtainedfromthelocalimpedancespectraafterdifferentexposuretimesin0.001M NaClandfordifferentpositionsofthebi-electrodeovertheAl/Cuassemblies:(d)withoutcavitiesand( )withcavities.Impedancevaluesarecalculatedtakingintoaccount ananalyzedsurfaceof1mm2.

wasmoreandmoremarkedwithincreasingimmersiontimefor theassemblywithcavities.

ThedifferencesinreactivitybetweenCuandAlfromonepart, andbetweenthetwoassembliesfortheotherpart,wereconfirmed bythevariationofaandQwithincreasingimmersiontime.After 24hofimmersion,thestrongreactivityattheAl/Cuinterfacewas

showedwithboththedecreaseofaandtheincreaseofQinthezone whereSEMmicrographies(Fig.10e)showedacreviceontheAlpart. Thisevolutionwasmoremarkedforanassemblywithcavitiesin relationwithalowercorrosionresistanceoftheAlpartduetothe penetrationoftheelectrolyteinsidethecavitiesofthecable.After 168hofimmersion,aandQvaluesconfirmedtheincreaseofthe

89

galvaniccouplingeffect.Between24hand168hofimmersion,a valuessignificantlydecreasedinagreementwithanincreaseofthe diffusionprocessesontheCupartandastrongercorrosionforthe Alpart.Moreover,itcanbeseenthatafter168hofimmersion, avaluesarelowerforboththeCuandAlpartsfortheassembly withcavitiesascomparedtotheassemblywithoutcavities.The resultcouldbelinkedtoastrongerincreaseofQvaluesattheAl/Cu interfaceobservedfortheassemblywithcavitiesascomparedto theassemblywithoutcavities.Theresultswereingoodagreement withthepresenceoftheconfinedelectrolytewhichamplifiedthe effectofthegalvaniccouplingwhentheimmersiontimeincreased. Therefore,theLEISmeasurementsprovidedevidencethatthe corrosionbehaviouroftheAl/Cuassemblywasexplainedbyboth thegalvaniccouplingbetweentheAlandCuparts,whichenhanced thecorrosionoftheAlpart,andthepenetrationoftheelectrolyte insidethecavitiesobservedintheAlpartoftheassembly,which ledtoamoreandmoreconfinedandaggressiveelectrolytewith increasingimmersiontimesothatitenhancedthereactivityofthe AlpartandthusthegalvaniccouplingwithCu.

4. Conclusions

ThestudywasfirstfocussedonthecorrosionbehaviourofanAl (AA1370)cableascomparedtoastrand.

1.OMobservationsafterexposuretoachloride-containing sul-phatesolutionshowedamoreextendedcorrosiondamagefor thecablethanforthestrand.

2.Electrochemical measurements showed for the cable: (i) a strongerdecreaseofthecorrosionpotentialwithtimethanfor thestrand,(ii)anincreaseoftheanodiccurrentdensity associ-atedwithapseudo-passivityplateauandamorenegativepitting potentialascomparedtothestrandand(iii)impedancediagrams characteristicofaporoussystem.

3.ThecorrosionbehaviouroftheAlcablewascontrolledbythe penetrationoftheelectrolytebetweenthestrandsconstitutive ofthecable.Suchaphenomenonledtoamoreaggressive con-finedmediumwhichexplainedthelowercorrosionresistance ofthecableascomparedtothestrand.

4.Then,thecorrosionbehaviouroftheassemblybetweenanAl cableandaCuconnectorwasinvestigatedbyelectrochemical techniques,andinparticularlocalimpedancemeasurements. 5.Aldissolution occurreddue togalvaniccouplingwiththeCu

connectorandcrevicecorrosionwasobservedontheCuwalls perpendicularlytotheAl/Cuinterfaceexposedtotheelectrolyte. 6.LocalimpedancedatashowedthatthecavitiesoftheAlcable significantlyinfluencedthecorrosionbehaviourofthe assem-bly:thereactivityattheAl/Cuinterfaceandtheextentofthe corrosiondamageontheAlpartwerestrongerfortheassembly withcavities.

References

[1]Y.Yamano,T.Hosokawa,Developmentofaluminumwiringharness,SEITech. Rev.73(2011)73–80.

[2]A.Laurino,E.Andrieu,J.P.Harouard,J.Lacaze,M.C.Lafont,G.Odemer,C. Blanc,Corrosionbehaviorof6101aluminumalloystrandforautomotive wires,J.Electrochem.Soc.160(2013)5069–5575.

[3]K.Yoshida,K.Doi,Improvementofductilityofaluminumwireforautomotive wiringharnessbyalternatedrawing,ProcediaEng.81(2014)706–711.

[4]S.Koch,H.Antrekowitsch,AluminumAlloysforwireharnessesinautomotive engineering,BergHuettenmaennMonatsh152(2007)62–67.

[5]S.-I.Matsuaka,H.Imai,Directweldingofdifferentmetalsusedultrasonic vibration,J.Mater.Process.Technol.209(2009)954–960.

[6]J.W.Yang,B.Cao,X.C.He,H.S.Luo,Microstructureevolutionandmechanical propertiesofCu–Aljointsbyultrasonicwelding,Sci.Technol.Weld.Join.19 (2014)500–504.

[7]R.Rambat,A.J.Davenport,G.M.Scamans,A.Afseth,Effectofiron-containing intermetallicparticlesonthecorrosionbehaviourofaluminum,Corros.Sci. 48(2006)3455–3471.

[8]J.O.Park,C.H.Paik,R.C.Alkire,ScanningMicrosensorsformeasurementof localpHdistributionsatthemicroscale,J.Electrochem.Soc.143(1996) 174–176.

[9]O.Seri,M.Imaizumi,ThedissolutionofFeAl3Intermetalliccompoundand

depositiononaluminuminAlCl3solution,Corros.Sci.30(1990)1121–1133.

[10]J.Xu,W.Chen,Behaviorofwireinparallelwirestayedcableundergeneral corrosioneffects,J.Constr.SteelRes.85(2013)40–47.

[11]Y.Ishikawa,S.Kawakami,Effectsofsaltcorrosionontheadhesionofbrass platedsteelcordtorubber,RubberChem.Technol.59(1986)1–15.

[12]J.J.Perdomo,I.Song,Chemicalandelectrochemicalconditionsonsteelunder disbondedcoatings:theeffectofappliedpotential,solutionresistivity, crevicethicknessandholidaysize,Corros.Sci.42(2000)1389–1415.

[13]S.H.Zhang,S.B.Lyon,Anodicprocessesonironcoveredbythin:dilute electrolytelayers(I)-anodicpolarisation,Corros.Sci.36(1994)1289–1307.

[14]R.Oltra,B.Malki,F.Rechou,Influenceofaerationonthelocalizedtrenching onaluminumalloys,Electrochim.Acta55(2010)4536–4542.

[15]S.Chanel,N.Pébère,Aninvestigationonthecorrosionofbrass-coatedsteel cordsfortyresbyelectrochemicaltechniques,Corros.Sci.43(2001)413–427.

[16]D.Wong,L.Swette,Aluminumcorrosioninuninhibitedethyleneglycol-water solutions,J.Electrochem.Soc.126(1979)11–15.

[17]M.G.A.Khedr,A.M.S.Lashien,Theroleofmetalcationsinthecorrosionand corrosioninhibitionofaluminuminaqueoussolutions,Corros.Sci.33(1992) 137–151.

[18]M.G.A.Khedr,A.M.S.Lashien,Corrosionbehaviorofaluminuminthepresence ofacceleratingmetalcationsandinhibition,J.Electrochem.Soc.136(1989) 968–972.

[19]J.-B.Jorcin,C.Blanc,N.Pébère,B.tribollet,V.Vivier,Galvaniccoupling betweenpurecopperandpurealuminum,J.Electrochem.Soc.155(2008) C46–C51.

[20]C.Blanc,N.Pébère,B.Tribollet,V.Vivier,Galvaniccouplingbetweencopper andaluminuminathin-layercell,Corros.Sci.52(2010)991–995.

[21]S.Joma,M.Sancy,E.Sutter,T.T.M.Tran,B.Tribollet,Incongruentdissolution ofcopperinAl-Cualloys:influenceoflocalpHchanges,Surf.InterfaceAnal. 45(2013)1590–1596.

[22]P.DeLima-Neto,J.P.Farias,L.F.G.Herculano,H.C.DeMiranda,Determination ofthesensitizedzoneextensioninweldedAISI304stainlesssteelusing non-destructiveelectrochemicaltechniques,Corros.Sci.50(2008) 1149–1155.

[23]G.Baril,C.Blanc,M.Keddam,N.Pébère,Localelectrochemicalimpedance spectroscopyappliedtothecorrosionbehaviorofanAZ91magnesiumalloy, J.Electrochem.Soc.150(2003)488–493.

[24]S.Marcelin,N.Pébère,Synergisticeffectbetween8-hydroxyquinolineand benzotriazoleforthecorrosionprotectionof2024aluminiumalloy:alocal electrochemicalimpedanceapproach,Corros.Sci.101(2015)66–74.

[25]M.Mouanga,M.Puiggali,B.tribollet,V.Vivier,N.Pébère,O.Devos,Galvanic corrosionbetweenzincandcarbonsteelinvestigatedbylocalelectrochemical impedancespectroscopy,Electrochim.Acta88(2013)6–14.

[26]D.Sidane,E.Bousquet,O.Devos,M.Puiggali,M.Touzet,V.Vivier,A. Poulon-Quintin,Localelectrochemicalstudyoffrictionstirweldedaluminum alloyassembly,J.Electroanal.Chem.737(2015)206–211.

[27]J.-B.Jorcin,M.E.Orazem,N.Pébère,B.Tribollet,CPEanalysisbylocal electrochemicalimpedancespectroscopy,Electrochim.Acta51(2006) 1473–1479.

[28]J.-B.Jorcin,E.Aragon,C.Merlatti,N.Pébère,Delaminatedareasbeneath organiccoating:alocalelectrochemicalimpedanceapproach,Corros.Sci.48 (2006)1779–1790.

[29]N.A.Belov,D.G.Eskin,A.A.Aksenov,MulticomponentPhaseDiagrams: ApplicationsforCommercialAluminiumAlloys,firstedition,ElsevierLtd, Oxford,2005.

[30]D.D.Macdonald,Reflectionsonthehistoryofelectrochemicalimpedance spectroscopy,Electrochim.Acta51(2006)1376–1388.

[31]C.Gabrielli,M.Keddam,N.Portail,P.Rousseau,H.Takenouti,V.Vivier, Electrochemicalimpedancespectroscopyinvestigationsofamicroelectrode behaviorinathin-layercell:experimentalandtheoreticalstudies,J.Phys. Chem.110(2006)20478–20485.

[32]H.-K.Song,H.-Y.Hwang,K.-H.Lee,L.H.Dao,Theeffectofporesize distributiononthefrequencydispersionofporouselectrodes,Electrochim. Acta45(2000)2241–2257.

[33]A.Lasia,Impedanceofporouselectrodes,J.Electroanal.Chem.397(1995) 27–33.

[34]C.Hitz,A.Lasia,Experimentalstudyandmodellingofimpedanceoftheheron porousNielectrodes,J.Electroanal.Chem.51(2001)213–222.

[35]S.Marcelin,N.Pébère,S.Régnier,Electrochemicalinvestigationsoncrevice corrosionofamartensiticstainlesssteelinathinlayercell,J.Electroanal. Chem.737(2015)198–205.

[36]M.Keddam,A.Hugot-Le-Goff,H.Takenouti,D.Thierry,M.C.Arevalo,The influenceofathinelectrolytelayeronthecorrosionprocessofzincin chloride-containingsolutions,Corros.Sci.33(1992)1243–1252.

[37]M.E.Orazem,N.Pébère,B.Tribollet,Enhancedgraphicalrepresentationof electrochemicalimpedancedata,J.Electrochem.Soc.153(2006)B129–B136.

[38]R.Vera,P.Verdugo,M.Orellana,E.Mu ˜noz,Corrosionofaluminiumin copper–aluminiumcouplesunderamarineenvironment:influenceof polyanilinedepositedontocopper,Corros.Sci.52(2010)3803–3810.

R.Gravinaetal./CorrosionScience119(2017)79–90

[39]L.B.Coelho,M.Mouanga,M.-E.Druart,I.Recloux,D.Cossement,M.-G.Olivier, ASVETstudyoftheinhibitiveeffectsofbenzotriazoleandceriumchloride solelyandcombinedonanaluminium/coppergalvaniccouplingmodel, Corros.Sci.110(2016)143–156.

[40]H.Shi,E.-H.Han,F.Liu,T.Wei,Z.Zhu,D.Xu,Studyofcorrosioninhibitionof coupledAl2Cu–AlandAl3Fe–Albyceriumcinnamateusingscanningvibrating

electrodetechniqueandscanningion-selectiveelectrodetechnique,Corros. Sci.98(2015)150–162.

[41]N.Murer,R.Oltra,B.Vuillemin,O.Néel,Numericalmodellingofthegalvanic couplinginaluminiumalloys:adiscussionontheapplicationoflocalprobe techniques,Corros.Sci.52(2010)130–139.

[42]J.Bernard,M.Chatenet,F.Dalard,Understandingaluminumbehaviorin aqueousalkalinesolutionusingcoupledtechniques:partI.Rotatingring-disk study,Electrochim.Acta52(2006),86–93.

[43]E.Håkansson,J.Hoffman,P.Predecki,M.Kumosa,Theroleofcorrosion productdepositioningalvaniccorrosionofaluminum/carbonsystems, Corros.Sci.114(2017)10–16.