HAL Id: tel-03144352

https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03144352

Submitted on 17 Feb 2021

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Uncovering the proliferation of contingent protection

through channels of retaliation, gender and development

assistance

Neha Bhardwaj Upadhayay

To cite this version:

Neha Bhardwaj Upadhayay. Uncovering the proliferation of contingent protection through channels of retaliation, gender and development assistance. Economics and Finance. Université Paris-Est, 2020. English. �NNT : 2020PESC0022�. �tel-03144352�

Université Paris Est

U.F.R. de sciences économiques et gestion

Année 2020 Numéro attribué par la bibliothèque

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

THESE

Pour l’obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Université de Paris Est Discipline : Sciences Economiques et Gestion

Présentée et soutenue publiquement par

Neha Bhardwaj Upadhayay

————–

Uncovering the proliferation of contingent protection through

channels of retaliation, gender and development assistance

Thèse dirigée par

Julie Lochard Pr. à l’Université Paris Est, Créteil Catherine Bros Pr. à l’Université Gustave Eiffel

MEMBRES DU JURY

Daniel Mirza (Rapporteur) Pr. à l’Université de Tours

Marcelo Olarreaga (Rapporteur) Pr. à l’University of Geneva

Robert Elliott Pr. à l’University of Birmingham

Abstract

This dissertation contributes to the empirical literature on trade protection through three independent chapters that have a common strand between them: use of contingent protection by trading economies of the world. In addition to tackling the conventional question on strategic determinants of contingent protection with a special focus on the role of mechanisms like retaliation (Chapter 1), this dissertation contributes two novel studies to the intertwinings of political economy with contingent protection: gendered role of national leadership (Chapter 2) and official development assistance (Chapter 3). The first chapter uncovers the determinants of anti-dumping - a trade policy that has emerged as a serious impediment to free trade. Anti-dumping actions have flourished, starting with active use by developed nations or traditional users, transcending into escalating use by developing countries or new users. The motives of anti-dumping use have also evolved, including influence of political factors, growing importance of strategic concerns, macroeconomic conditions like exchange rates and GDP. Researchers have questioned whether anti-dumping filings may be motivated as retaliation against similar measures imposed on a country’s exporters. This is the focus of this chapter, though we also control for other anti-dumping related indicators like past filing behaviour, cases filed globally and cases faced by the exporter. Using a large sample of anti-dumping users and their trade partners for a two decade period (1996-2015), we show that there exists marked heterogeneity in nations’ use of anti-dumping as a contingent protection mechanism. The focus of this chapter is on retaliatory motives and we find evidence that this effect is masked at the aggregate level with insufficient statistical significance (except for select regions and income groups of countries), however, a sectoral analysis reveals that retaliation is a positive and significant determinant of current anti-dumping case filing activity for a select group of large importers. Another key result of this study is that a substitution effect exists between trade liberalisation (reduction of applied tariffs) and anti-dumping petitioning activity.

In the second chapter we raise the issue of national leadership and how it can affect the trade policy treatment in a country. In this context, a higher level of belligerence can be encountered by countries led by women leaders due to a world-view based on prejudice (against women). In

this chapter, this belligerence is modeled as actions like dumping or subsidies by exporting nations that increase the probability of countermeasures from importing nations. Our argument is, due to existing prejudices, threats from countries led by men (importers) could be considered more credible and hence the trade conflict raising action (from the exporter) is curtailed. On the other hand, threats from countries led by women are considered non-credible and hence the country ends up taking the countermeasure against a trading partner (to curtail or stop completely the conflict raising action like dumping or subsidies to exports). We find that the presence of a woman chief executive is positively correlated with the propensity to instigate trade protection measures. We see the moderating effect of political institutions with higher women participation in parliaments leading to a plummeting of protection related petitioning at international forums.

The third chapter is an attempt to evoke a debate on the nexus between foreign aid and increased protection by donor nations. The primary research question addressed in this chapter is whether donor nations provide market access to the recipients of their aid, specifically Aid for Trade (AfT), which is given to assist in the cause of trade. Using aid and protection data, this chapter finds evidence that US contingent protection activity increases against a country which has been the recipient of US AfT in the previous period. This chapter also finds that between the two main activity heads of AfT i.e. Economic Infrastructure & Services and Production Sector, it is the former that is the significant medium for the use of protectionist policy. To examine the heterogeneity in donor decisions, this study is expanded to other traditional donors like Australia, Canada, European Union and New Zealand. This chapter finds that Australia behaves similar to the US, however, for Canada and the European Union the relationship between aid and market access is not statistically significant. This chapter raises important questions on the validity and prevalence of the AfT program and the (newly challenged) role of WTO in maintaining the rules of international trade to ensure that developing countries are not stripped off their trade advantages from one hand while being thrusted with aid in the other.

Keywords: Trade policy, protection, Anti-dumping duties, Countervailing duties, contingent protec-tion, retaliaprotec-tion, women leaders, Aid for Trade

Resumé

Cette thèse contribue à la littérature empirique sur la protection commerciale à travers trois chapitres indépendants ayant un point commun : l’utilisation de la protection contingente par les économies. En plus d’aborder la question traditionnelle des déterminants stratégiques de la protection contingente en mettant l’accent sur le rôle des représailles (chapitre 1), cette thèse deux nouvelles études sur l’imbrication de l’économie politique avec la protection contingente. La première s’intéresse au rôle du genre du dirigeant national (chapitre 2) et la seconde traite des effets de l’aide publique au développement (chapitre 3).

Le premier chapitre met en évidence les déterminants de l’antidumping, une politique commerciale qui est apparue comme un obstacle majeur au libre-échange. Les mesures antidumping se sont multipliées ces dernières années. Elles ont été utilisées au départ principalement par les pays développés (utilisateurs traditionnels), puis de plus en plus par les pays en développement (nouveaux utilisateurs). Les motivations du recours à ces mesures ont également évolué, notamment sous l’influence de facteurs politiques et de conditions macroéconomiques. Les mesures antidumping pourraient également être motivées par des rétorsions contre des mesures similaires imposées aux exportateurs d’un pays. C’est l’objet de ce chapitre dans lequel nous prenons également en compte d’autres déterminants des mesures d’antidumping : le comportement antérieur en matière d’antidumping; celui adopté avec le monde entier et les cas d’antidumping auxquels l’exportateur est confronté. Nous incluons aussi, dans notre analyse empirique, d’autres motifs comme les facteurs macroéconomiques et stratégiques. En utilisant un large échantillon de pays sur près de vingt ans, nous montrons qu’il existe une grande hétérogénéité dans l’utilisation par les nations de l’antidumping comme mécanisme de protection. Le présent chapitre se concentre sur les motifs de rétorsion et, si l’effet apparaît comme masqué au niveau global, une analyse sectorielle révèle que les rétorsions sont un déterminant positif et significatif de l’utilisation des mesures antidumping pour un groupe restreint de grands importateurs. Un autre résultat de cette étude est qu’il existe un effet de substitution entre la libéralisation du commerce (réduction des tarifs appliqués) et l’activité en matière d’antidumping.

Dans le deuxième chapitre, nous soulevons la question du leadership national et de la manière dont il peut affecter le traitement de la politique commerciale dans un pays. L’influence des dirigeantes féminines sur la conception des politiques a reçu peu d’attention dans la littérature. Dans ce contexte, les pays dirigés par des femmes peuvent être confrontés à un niveau de belligérance plus élevé en raison d’une vision du monde fondée sur les préjugés à l’égard des femmes. Dans ce chapitre, cette belligérance est modélisée par des actions telles que le dumping ou les subventions des pays exportateurs qui augmentent la probabilité de contre-mesures de la part des pays importateurs. Nous nous basons sur le rôle de la menace qui est fonction du sexe du dirigeant du pays. Notre argument est, qu’en raison des préjugés existants, les menaces provenant de pays dirigés par des hommes (importateurs) pourraient être considérées comme plus crédibles et que, par conséquent, la probabilité de conflits commerciaux (de la part de l’exportateur) est réduite. A l’inverse, les menaces émanant de pays dirigés par des femmes considérées comme non crédibles et le pays peut être amené à mettre en oeuvre des contre-mesures à l’égard de son partenaire commercial (pour réduire ou arrêter complètement la probabilité de survenue de conflits tels que le dumping ou les subventions aux exportations). Nous testons l’hypothèse de recherche suivante : les dirigeantes féminines ont-elles un rôle à jouer dans le renforcement des mesures de protection commerciale perçues comme un moyen de prévenir la hausse des importations faisant l’objet d’un dumping ? Nous montrons également qu’une plus grande présence des femmes dans les parlements nationaux exerce un effet modérateur sur la propension des femmes dirigeantes à mettre en place des mesures protectionnistes.

Le troisième chapitre s’inscrit dans le débat sur le lien entre l’aide étrangère et la protection accrue des pays donateurs. Ce chapitre explore les interactions entre l’aide en tant que politique étrangère et la politique commerciale. Le commerce ayant un rôle vital dans le développement des pays à faible revenu, l’aide au commerce vise à mobiliser des ressources pour faire face aux contraintes liées à ce dernier. Les recherches existantes suggèrent que l’aide incite le bénéficiaire à adopter des politiques commerciales plus ouvertes qui incitent, elles-mêmes, le donateur à donner l’aide. Cependant, l’augmentation ultérieure des flux commerciaux entre les deux pays dépend de ce que fait le donateur. Dans ce contexte, la principale question de recherche abordée dans ce chapitre est de savoir si les pays donateurs offrent un accès au marché aux bénéficiaires de leur aide, en particulier dans le cas de l’aide commerce, qui est spécifiquement accordée pour favoriser le commerce. En utilisant la protection contingente des États-Unis contre les pays qui bénéficient de l’aide pour le commerce des États-Unis, ce chapitre montre que la protection est plus élevée contre des pays qui ont bénéficié de l’aide au commerce des États-Unis au cours de la période précédente. Ce chapitre montre également qu’entre, c’est la première qui est le plus importante. Pour examiner l’hétérogénéité des décisions des donateurs, cette étude est étendue à d’autres donateurs traditionnels comme l’Australie, le Canada, l’Union européenne et la Nouvelle-Zélande. Nous montrons que l’Australie se comporte de manière similaire aux États-Unis, mais que, pour le Canada et l’Union

européenne, la relation entre l’aide et l’accès au marché n’est pas statistiquement significative. Ce chapitre soulève d’importantes questions sur la validité et la prévalence du programme d’aide au commerce et le rôle (nouvellement contesté) de l’OMC dans le maintien des règles du commerce international afin de garantir que les pays en développement ne soient pas dépossédés de leurs avantages commerciaux d’une part, et qu’ils ne soient pas poussés par l’aide d’autre part.

Mots-clés: Politique commerciale, protection, droits antidumping, droits compensateurs, protection contingente, représailles, femmes leaders, aide pour le commerce

Contents

Page

Abstract i

Resumé iii

List of Tables xi

List of Figures xiii

List of Acronyms xiv

General Introduction 1

1 Protection begets protection?

Role of retaliation in anti-dumping case filing 20

1.1 Introduction . . . 20

1.2 Literature and evidence on anti-dumping . . . 21

1.3 Empirical Analysis . . . 30

1.4 Results . . . 36

1.5 Sectoral Analysis . . . 45

1.6 Conclusion . . . 54

2 Are only men fighting trade wars? Role of national leadership in contingent protection activity 56 2.1 Introduction . . . 56

2.2 Gender and trade policy . . . 59

2.3 Empirical framework . . . 64

2.5 Conclusion . . . 81

3 Medicine with side effects Aid for Trade followed with targeted protection 83 3.1 Introduction . . . 83

3.2 Foreign Aid and Aid for Trade - Related literature . . . 86

3.3 Empirical Framework and Analysis . . . 94

3.4 Results . . . 102

3.5 Disaggregating Aid for Trade . . . 108

3.6 Robustness Checks . . . 112

3.7 Conclusion . . . 122

General Conclusion 124

Appendix A Appendix for Chapter 1 129

Appendix B Appendix for Chapter 2 139

Appendix C Appendix for Chapter 3 149

List of Tables

1 Average NTM use per USD 1 billion of imports (Top users) . . . 6

2 Trade contingent actions, Initiations and Measures:1995-2018 . . . 6

1.1 Initiation of AD cases by reporting country income: number of cases and intensity (1995-2015) . . . 23

1.2 Summary Statistics, Aggregate Analysis . . . 34

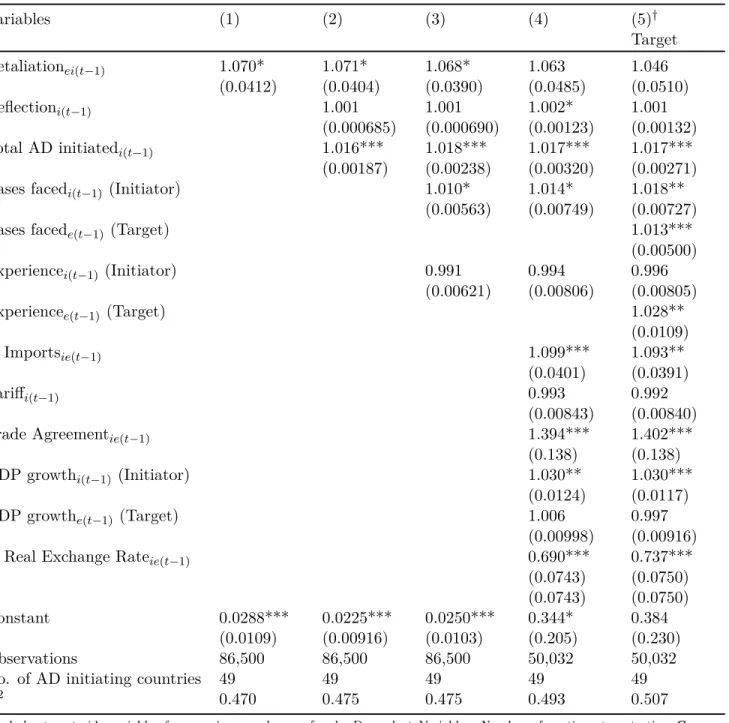

1.3 Intensity of AD initiations: Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation (Incidence Rate Ratios), 1996-2015, Baseline specification . . . 38

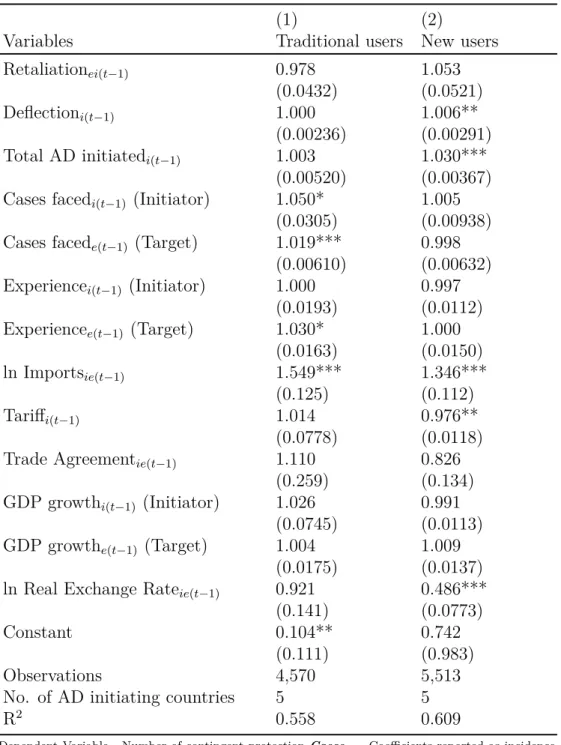

1.4 Intensity of AD initiations: Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation (Incidence Rate Ratios), 1996-2015, Income-wise Analysis . . . 40

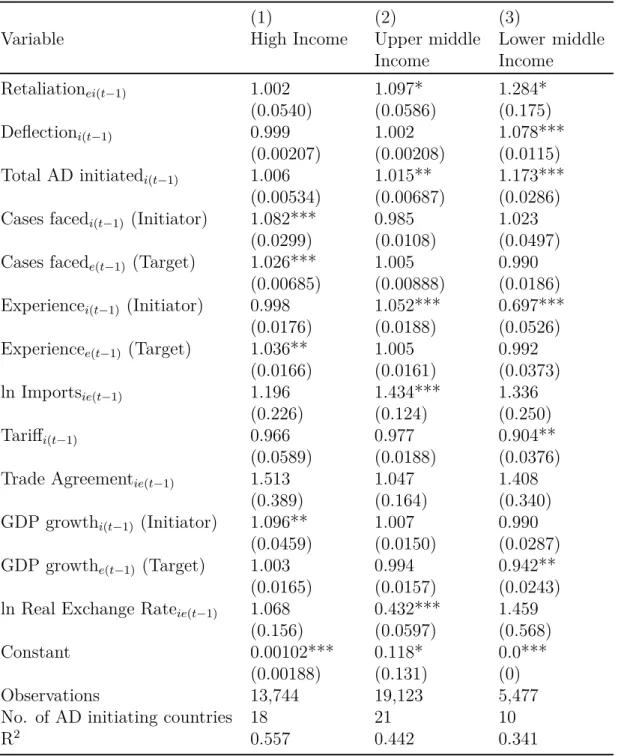

1.5 Intensity of AD initiations: Pseudo Poisson maximum likelihood model (Inci-dence Rate Ratios), 1996-2015, Traditional and New users of AD. . . 42

1.6 Intensity of AD initiations: Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation (Inci-dence Rate Ratios), 1996-2015, Country level analysis based on size of importer in terms of trade value . . . 44

1.7 Summary Statistics, Sectoral Analysis. . . 46

1.8 Determinants of AD initiations, Probit regression analysis, 1996-2015, Baseline specification on sectoral level. . . 49

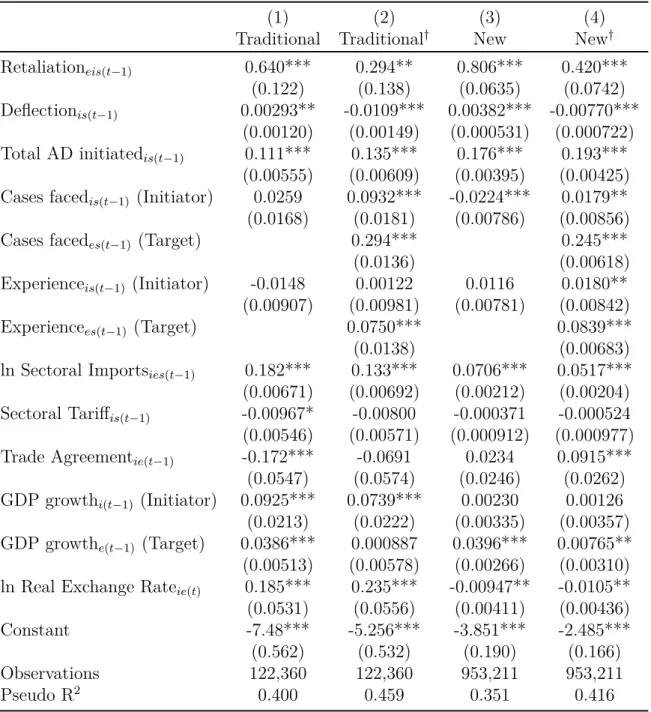

1.9 Determinants of AD initiations: Probit regression analysis, 1996-2015,

Tradi-tional and New users of AD on sectoral level . . . 52

1.10 Determinants of AD initiations: Probit regression analysis, 1996-2015, Sectoral analysis based on size of importer in terms of trade value . . . 53

2.1 Descriptive Statistics . . . 68

2.2 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Negative Binomial regression, 1998-2018, Baseline specification . . . 70

2.3 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Negative Binomial regression, 1998-2018, Additional controls and Interaction Results . . . 73

2.4 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Negative Binomial regression, 1998-2018, Temporal analysis . . . 76

2.5 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Negative Binomial regression, 1998-2018, Robustness checks . . . 77

2.6 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Instrumental Vari-able (IV) analysis, 1998-2018. . . 80

3.1 Summary Statistics for the main variables, USA sub-sample . . . 102

3.2 The impact of US Aid for Trade (AfT) on contingent protection case initiations against recipients, 2001-2018 . . . 104

3.3 Explaining the Aid for Trade (AfT) variable, first stage Ordinary Least Squared (OLS) regressions, 2001-2018 . . . 107

3.4 The impact of Aid for Trade (AfT) on contingent protection case initiations, Instrumental Variable (IV) analysis, 2001-2018 . . . 108

3.5 Summary Statistics for the main variables, USA sub-sample, dis-aggregate analysis . . . 110

3.6 The impact of disaggregated AfT on contingent protection case initiations, Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation, 2001-2018 . . . 111

3.7 The impact of AfT on contingent protection case initiations, Regions & Income categories of recipients, Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation, 2001-2018 . . . 113

3.8 The impact of US AfT on contingent protection case initiations against re-cipients, Presidents in power, Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation, 2001-2018 . . . 114

3.9 The impact of AfT on contingent protection case initiations and measures imposed, Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation, 2001-2018 . . . 117

3.10 The impact of AfT on contingent protection case initiations, comparing the US with Australia, Canada, European Union and New Zealand, Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation, 2001-2018 . . . 121

A.1 Contingent protection measure users . . . 130

A.2 HS 2002 Classification by Sector . . . 131

A.3 Intensity of AD initiations: Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation (In-cidence Rate Ratios), 1996-2015, Baseline specification with step-wise inclusion of controls . . . 132

A.4 Intensity of AD initiations: Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation,

1996-2015, Regional Analysis. . . 133

A.5 Determinants of AD initiations: Poisson pseudo maximum likelihood model (Inci-dence Rate Ratios), 1996-2015, Robustness checks . . . 134

A.6 Intensity of AD initiations: Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation (Incidence Rate Ratios), 1996-2015, Retaliation lagged by 2 and 3 periods . . 135

A.7 Determinants of contingent protection initiations: Probit binary choice model, marginal effects, 1996-2015 . . . 136

A.8 Determinants of AD initiations, 1996-2015, Baseline specification on sectoral level . . . 137

A.9 Determinants of AD initiations, 1996-2015, specification on sectoral level for select industry (sector) category . . . 138

B.1 Payoff Matrix- Mixed Strategy Game . . . 141

B.2 Contingent protection measure users . . . 143

B.3 Countries targeted by contingent protection users . . . 143

B.4 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Negative Binomial regression (Incidence Rate Ratios), 1998-2018, Baseline specification . . . 144

B.5 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Negative Bino-mial regression (Incidence Rate Ratios), 1998-2018, Additional controls and Interaction Results . . . 145

B.6 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Negative Binomial regression (Incidence Rate Ratios), 1998-2018, Temporal analysis. . . 146

B.7 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Instrumental Vari-able (IV) analysis, 1998-2018. . . 147

B.8 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Negative Binomial regression, 1998-2018, Sensitivity checks (Part 1) . . . 148

B.9 The impact of woman leadership on contingent protection, Negative Binomial regression, 1998-2018, Sensitivity checks (Part 2) . . . 148

C.1 Aid for Trade Sector definition . . . 149

C.2 Aid recipient countries targeted under contingent protection measures by the USA . . . 149

C.3 The impact of US Aid for Trade (AfT) on contingent protection case initiations against recipients, 2001-2018 . . . 153

C.4 The impact of US Aid for Trade (AfT) on contingent protection case initiations against recipients, 2001-2018 . . . 154

C.5 Number of contingent protection cases, Sensitivity Analysis Results, Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimation (Incidence Rate Ratio), 2001-2018. . 155

List of Figures

1 World applied most favoured nation (MFN) tariffs vs non-tariff measures . . 3

2 Number of non-tariff measures imposed by countries, 1995-2018 . . . 4

3 Tariffs applied (weighted mean, all products in %), by income of countries . 4

4 Trading nations’ use of countervailing duties, 1995-2018 . . . 9

5 Trading nations’ use of safeguards (by sector), 1995-2018 . . . 10

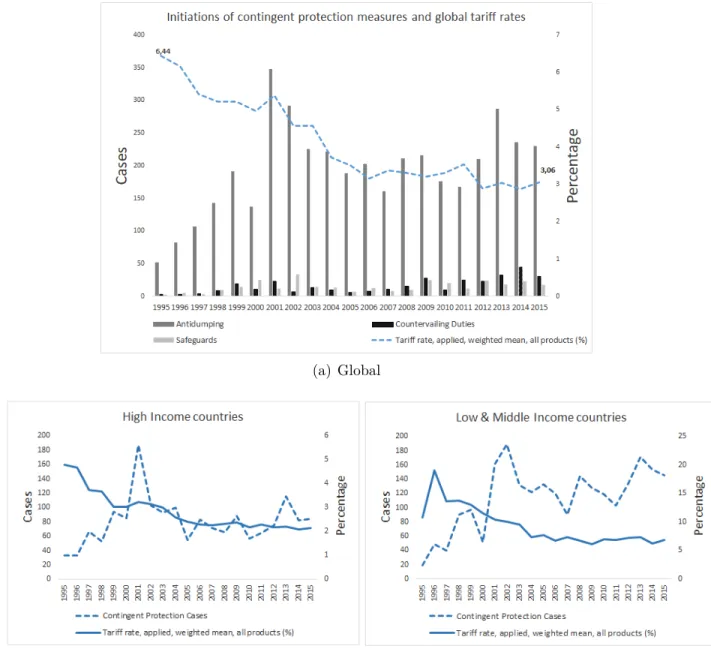

1.1 Initiations of contingent protection measures and global values of applied tariff (all products, %), 1995-2015 . . . 22

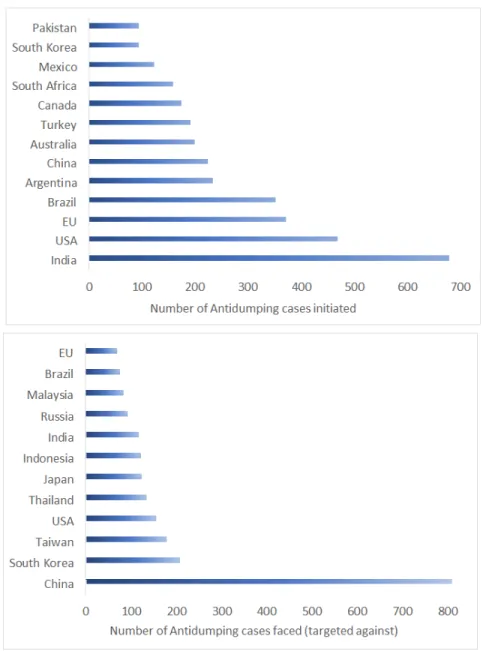

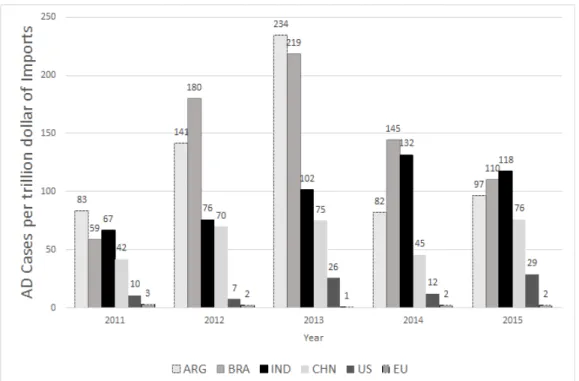

1.2 Top reporters and targets of anti-dumping cases, 1995-2015 . . . 24

1.3 Anti-dumping cases per trillion dollar of import for the period 2011-2015 . . 25

1.4 Initiations of anti-dumping cases, 1996-2015 . . . 26

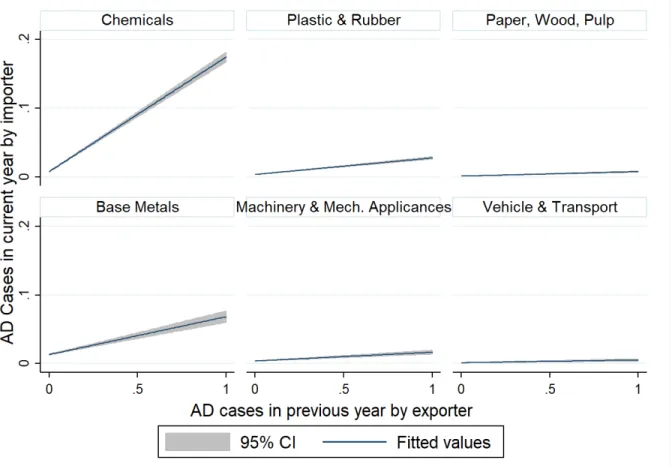

1.5 Retaliation by Sector (predicted values of cases filed vs. indicator for retaliation) 51

2.1 Non-tariff contingent protection initiations in the US and EU (two of the traditional users) vs. Percentage of women in the respective parliaments . . 61

2.2 Non-tariff contingent protection initiations in the prominent new users in Asia and South America vs. Percentage of women in the respective parliaments . 62

2.3 Effect of women in parliament on predicted values of contingent protection cases 74

3.1 Interactions of aid, trade and protection policies . . . 92

3.2 US AfT commitment and contingent protection case initiation from 2006 to 2018 94

3.3 US Net ODA provided (bilateral & multilateral), total (% of GNI) . . . 95

3.4 US Aid commitment to bilateral recipients (as a percentage of GNI) . . . 96

3.5 Distribution of dependent variable . . . 102

3.6 Distribution of Cases initiated and Measures implemented vs. AfT and Total ODA (net of AfT). . . 103

3.8 Cases (initiated) vs. Aid commitment (as a percentage of GNI) to bilateral

recipients, Top donors, 2001-2018 . . . 119

B.1 Year-wise contingent protection initiations by level of development of initiators139 C.1 AfT commitments and disbursements (2006-2017) . . . 150

C.2 AfT disbursements by Region (2006-2017) . . . 151

C.3 Top donors by commitments and disbursements, 2016 & 2017 . . . 151

C.4 Net trade in goods and services- USA (2000-2018) . . . 152

C.5 (a) US Shrimp imports from the 6 countries facing Anti-dumping duties (b) US Protection and Aid . . . 157

List of Acronyms

Acronym Expansion

ADB Asian Development Bank

AD Anti-dumping

AFT /AfT Aid for Trade

AVE ad valorem equivalent

CRS Creditor Reporting System

CVD Countervailing Duty

EAP East Asia and Pacific

ECA Europe and Central Asia

EU European Union

GATT General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

IADB Inter-American Development Bank

ICTSD International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development

IDA World Bank International Development Association

LAC Latin America and the Caribbean

LDCs least developed countries

MDG Millennium Development Goals

MENA Middle East and North Africa

NA North America

NIU National Implementation Unit

NTB non-tariff barrier

NTM non-tariff measure

ODA Official Development Assistance

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

SA South Asia

Acronym Expansion

SPS Sanitary and phytosanitary

SSA sub-Saharan Africa

TDSP Trade Development Support Program

TRAINS Trade Analysis and Information System

UNCTAD United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

US/USA United States of America

WBG World Bank Group

WGI Worldwide Governance Indicators

General Introduction

Background

Multilateralism - which is the extension of trade rules without discrimination to all members of trading regime - if not dead, maybe at risk (Bhagwati, 1990). Almost quarter century later, Bhagwati et al. (2016) continue to warn us of the threats1 to multilateral trading

systems, specifically the WTO and its rule-making role. The results of multilateral trade reforms have ushered the ‘death of distance’ (Cairncross, 2002), ‘world is flat’ (Friedman,

2005) and ‘great convergence’ (Baldwin, 2016), as the great achievements of globalisation, all pointing to the universal reduction in the costs of trading. However, through econometric decomposition of trade costs, researchers find that in addition to traditional sources of trade costs (tariffs and transportation charges), additional factors are now affecting the pattern of trade and production and these costs are more severe for the developing world (Anderson and Van Wincoop, 2004; Arvis et al., 2013; Looi Kee et al., 2009; Mirza and Verdier, 2014). These motley results give rise to the question whether the real costs of trading have indeed fallen for everyone?

Trade depends not only on the production of goods and services, rather also on the costs of trading. Trade costs, broadly defined as all costs incurred in getting a good to a final user other than the marginal cost of producing the good itself, include policy barriers (tariff and non-tariff), all transport (freight), border-related, contract enforcement costs, currency cost and local distribution costs from foreign producer to final user in the domestic country

1Bhagwati et al.(2016) attribute the rise of these threats, not only, from a variety of fundamental changes

in the world economy, but also systems within the WTO, giving countries room to restrict free trade. For instance, countries failed to close the Doha Round of trade negotiations and with the emergence of bilateral and plurilateral preferential trade arrangements (PTAs) such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the future of the multilateral trade systems is questioned by researchers.

(Anderson and Van Wincoop, 2004)2. Arvis et al. (2013) suggest that, not just geographical

distance, it is actually trade facilitation and logistics performance that play a major role in the trade isolation of developing countries. Deep regulatory and institutional features, that are discriminatory against foreign firms, also play a role in enhancing trade costs for developing countries3.

Given that tariffs, as trade costs, seem to be the most ‘visible’ impediment to trade, one may question whether multilateralism or free trade is really at risk considering the fact that average applied tariffs have been consistently coming down since the end of the second world war. To this effect, Baldwin et al. (2000) and Panagariya (2013) suggest that world trade is freer post-WTO in terms of reduction of tariffs4. The WTO documents that in its 25 years

of existence, average tariffs have almost halved, from 10.5% to 6.4%, however, non-tariff measures have been on a rise (WTO, 2019d) (See Figure 1). While the consequences of non-tariff measures are multitudinous, their proliferation is fraught with severe ramifications for multilateralism. Muzaka and Bishop (2015) suggest not restricting our attention to just short and medium term consequences, the decline of multilateral trade systems (like the WTO), in the long run, characterises the lack of a shared social purpose between the developed countries and the more powerful emerging countries which challenges the very foundation of trade politics.

It is therefore consequential to examine and understand the determinants of trade barriers like non-tariff measures as a trade policy (Gawande et al.,2015). Not only this, it is also important to unravel the role of policy makers (national leaders) and linked policy agenda (like official development assistance) when countries deploy barriers to trade as tacit circumvention of global trading rules (Blonigen and Prusa,2001). This dissertation focuses on a select category of non-tariff measures i.e. contingent protection measures, more specifically, anti-dumping and countervailing duties.

2Anderson and Van Wincoop(2004) find a ‘headline’ number of 170% ad valorem for a typical developed

country. This number is broken down to 21% transport costs, 44% border related trade barriers, and 55% wholesale and retail distribution costs (2.70 = 1.21×1.44×1.55). Of the 44% ad valorem equivalent of border related trade barriers, only 8% relates to traditional trade policies such as tariffs.

3Within the developing countries, considerable disparity is seen in terms of trade costs with East Asia and

the Pacific exhibiting lower levels compared to Sub-Saharan Africa (Arvis et al.,2013).

4There is a body of research papers around 2010-2015 which validate the successes of the WTO. Prominent

among these isDavey(2012) who concludes that the WTO has been broadly successful in implementing the existing agreements and settling disputes. Panagariya (2013) observes that despite several challenges, the WTO has been successful on two fronts: keeping global trade free, and ensuring that developing countries have embraced freer trade and investment. This is in striking contrast to the views ofBhagwati(1990);

Bhagwati et al.(2016) and therefore, we can see that researchers are divided in their opinion about the success of the WTO with positions evolving due to several exogenous factors.

Figure 1: World applied most favoured nation (MFN) tariffs vs non-tariff measures

Source: World tariff profile (WTO,2019d) and non-tariff measures data (WTO,2019e) Note: Non tariff measures used for this graphic are Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS), Anti-dumping duties (AD),

Countervailing Duties (CVD) & Safeguards (SG)

Non-tariff measures

By definition, any government trade policy, other than tariffs, that leads to discriminatory treatment of foreign competitors relative to domestic producers could be termed as non-tariff measure (NTM) (UNCTAD, 2017). In other words, NTMs5 are policy measures, other than

[ordinary] customs tariffs, that can potentially have an economic effect on international trade in goods, changing quantities traded, or prices or both (WTO, 2019d).

With respect to non tariff measure indicators covered by WTO data6, the United States tops

5Often used interchangeably, non tariff measures (NTM) and non tariff barriers (NTB) are marginally

divergent concepts mainly differentiated on the intent of the regulation. NTBs are policies that almost always induce an adverse impact on trade due to a discriminatory or protectionist hue. On the other hand, NTMs are in place to serve public interest and ensure national security (Marks,2020). These may, however, transition into an NTB when the theoretical intent is incompatible with the practical implementation (Finger,

1992). In this chapter we use contingent protection measures like anti-dumping and countervailing duties for analysis. These are classified as non-tariff measures by theWTO (2019e) and therefore we use the nomenclature NTM throughout the dissertation.

6Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures, Anti-dumping duties (AD), Countervailing Duties (CVD) &

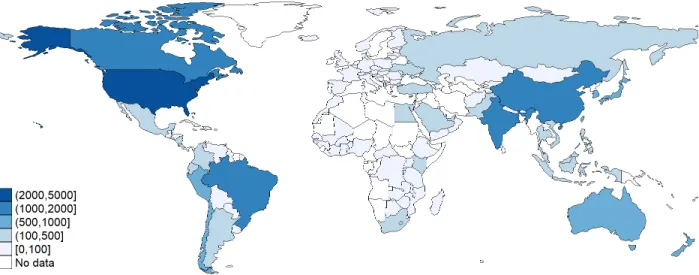

Figure 2: Number of non-tariff measures imposed by countries, 1995-2018

Source: WTO (2019e)

the chart in implementation with more than 3,850 incidences since the establishment of the WTO (1995). In the developed world, they are followed by Canada, EU, Australia and Japan. Developing countries like India, Brazil and China have initiated measures that are half in number of the US cases (See Figure2). Nevertheless, these are high, exceeding 1,000 cases in the said period.

Figure 3: Tariffs applied (weighted mean, all products in %), by income of countries

Since the 1960s, tariffs have remained low in the developed or high income economies. In recent years, even for emerging economies, they are inching closer to those of advanced countries, a consequence of the trade liberalisation phenomenon that these countries have been witness of (See Figure 3). As seen in Figure 1, we may question if there exists a substitution effect between tariffs and non-tariff measures on trade. In this context, several theoretical and empirical studies have tried to answer this question. Anderson and Schmitt

(2003) develop a model showing that when governments can set tariffs freely, they have no incentive to impose non-tariff measures. When a coordinated liberalisation of tariffs takes place, there is a progression from tariff protection to the use of quotas. If quotas are also limited, this is followed by a movement to anti-dumping enforcement. This argument is supported by the empirical work of Feinberg and Reynolds (2007) who show for developing countries, tariff reductions not only increased the likelihood of a country using anti-dumping protection (non-tariff measure) but also the total number of anti-dumping petitions filed by countries. Moore and Zanardi (2009) confirm the existence of a substitution between tariffs and use of non-tariff measures like anti-dumping, albeit, only for developing countries who are heavy users of the anti-dumping provision in the WTO rules. In a study specific to India,

Bown and Tovar (2011) find products with larger tariff cuts due to the trade liberalisation in the 1990s are associated with an increase in non-tariff measures or protection. With respect to trade restrictiveness, Looi Kee et al. (2009) argue that non-tariff measures contribute an additional 87% to the restrictiveness imposed by tariffs. Therefore, they advocate that non-tariff measures should be a priority for those negotiating trade policy.

Contingent Protection

Anti-dumping duties, Countervailing Duties and Safeguards fall under the category of ‘Con-tingent Protection’ actions since the WTO agreement requires a link between trade volume and the imposition of trade protection for all of these trade remedies (Prusa and Teh,2011)7.

In the 2009-2018 decade, non-tariff measures of the contingent protection type constituted 65% of the pie of all protection measures used by trading countries (Global Trade Alert,2020). Another indication of the importance of contingent protection measures is the proportion of world trade affected by them (Niels, 2000). This proportion is difficult to calculate, however, the metric of cases per dollar of imports provides an idea of the proliferation of these measures (See Table 1). What is more striking is that developing economies have been more intense

users of non-tariff measures when compared to the traditional users (Prusa, 2005).

To provide context to this argument, consider the case of products of iron or steel (metals sector). In 2018, metals accounted for 7% of global trade while consumer goods are roughly 31% and machinery and electrical are roughly 26% of the global trade (World Integrated Trade Solution,2019). In the ten year period 2009-2018, about 1,800 interventions were made globally on metals and fabricated metal products which is 32% of the total interventions (Global Trade Alert, 2020)8. Thus a very large portion of globally traded products (and

value) were subject to duties at any given point in time.

Table 1: Average NTM use per USD 1 billion of imports (Top users)

Country 1995-2004 2005-2014 2015-2018 Developed Economies Australia 0.120 0.06 0.080 Canada 0.054 0.02 0.037 European Union 0.008 0.003 0.002 Japan 0.001 0.0008 0.002 United States 0.028 0.012 0.026 Developing Economies Argentina 0.527 0.261 0.227 Brazil 0.140 0.138 0.075 China 0.032 0.011 0.008 India 0.622 0.125 0.117 Mexico 0.044 0.017 0.015 Turkey 0.135 0.064 0.063 South Africa 0.35 0.070 0.012

Source : Author’s calculation fromWTO (2019e)

Table 2: Trade contingent actions, Initiations and Measures:1995-2018 Trade contingent instrument Initiations Relative Measures Relative

Anti-dumping Duty 4,830 85.3 % 3,607 88%

Countervailing Duty 469 8.2% 271 6.6%

Global safeguards 364 6.5% 189 4.6%

Source : Author’s calculation fromWTO (2019e)

8In recent trends, researchers have also found that coverage of contingent protection is extended to several

As shown in Table 2, there have been over 4,800 anti-dumping initiations and over 800 countervailing duty and safeguard initiations since 19959. Within this category of protection

actions, Blonigen and Prusa (2001) note that since 1980 (till 2001, when their paper was published) GATT/WTO members had filed more complaints under the Anti-dumping statute than under all other trade laws combined. Given that the focus of this dissertation is on anti-dumping and countervailing duties as non-tariff measures or forms of trade protection, we devote the next few pages to discussing these contingent protection measures in detail.

Contingent Protection - Anti-dumping

The first Anti-dumping law passed by a sovereign government was over a century ago (in 1904) by Canada. This was followed by similar legislation in most of the major trading nations in the industrialised world prior to and after World War I (New Zealand (1905), Australia (1906), USA(1916)). After the World War II, Anti-dumping provisions were incorporated into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) (Deardorff and Stern,2005). Since the turn of the century, developing countries - that have historically played only a minor role in the contingent protection landscape, have been involved in an overwhelming way as either petitioners or targets of these contingent protection cases (Feinberg,2011).

Dumping10 is said to have taken place when an exporter sells a product in a market at

a price less than the price prevailing in its own domestic market (sometimes even lower than cost of production) (Viner, 1923). A proof of ‘injury’ (or threat of an injury) to a competing domestic industry, within the provisions of the Agreement on Implementation of Article VI of the GATT 1994, makes the importing country eligible to impose anti-dumping measures against the exporters. Here, injury could mean material injury to a domestic industry, threat of material injury to a domestic industry, or material retardation of the establishment of such an industry and shall be interpreted in accordance with the provisions of this Article (WTO Antidumping Agreement, 1995). The dumping margin determines the quantum of duty that an importer levies on the ‘unfair’ imports. The dumping margin is the difference between the export price and the domestic selling price in the exporting country. Should the

9We use this year as a starting point because the WTO was formed on January 1, 1995.

10In his seminal work on dumping,Viner(1923) classifies dumping according to motive : (1) the bargain-sale

type, to dispose of a casual surplus; (2) the advertising type, to obtain or retain a market in which prices will presently revert to higher levels; (3) the predatory type, to kill or forestall competition; (4) the bounty-fed type in which exports at lower than the home price are made profitable through export bounties granted by governments of mercantilistic tendency; and (5) the cost-reducing type, to secure or retain a reduced unit cost by the expansion of output. He also suggests that after the 1890s, the fifth type of dumping has become most important of all suggesting that dumping is simply a method for obtaining economies which would be impossible without it.

determination of the comparable domestic price be impossible, export prices to third countries or a ‘constructed value’ is used for price comparison. Constructed value is calculated as the cost of production in the country of origin plus reasonable amounts of handling costs and profits.

Stiglitz(1997) argues that from a static perspective, dumping by foreign firms seems to make consumers better off. However, from the policymakers’ point of view, dumping could become a problem in wake of predatory pricing and new trade theory effects.

Predatory pricing is a tactic employed by firms to drive down market prices to such low levels that other firms are forced to exit the market because they just cannot compete. Predatory pricing, while unprofitable initially, can lead to profits in the second stage by acting as an entry barrier for other firms. However, several conditions may exist in which firms sell less than the cost of production. For example, firms may have sales below average total cost but above average variable cost in the short run. Also, learning curves can prompt firms to forward price at long-run marginal cost rather than short-run marginal cost (Stiglitz,1997). In recent years, it is seen that foreign firms are targeted with anti-dumping cases despite charging higher prices abroad or prices higher than domestic competitors. Thus, predatory pricing does not feature as a pre-requisite for filing anti-dumping petition against firms. Therefore, Blonigen and Prusa (2001) conclude that ‘Anti-dumping has nothing to do with predatory pricing’- a conclusion arrived at by Stiglitz(1997) much earlier.

With respect to the new trade theory effects, Brander and Spencer (1985) suggest that there may be cases in which subsidy on imports could raise national welfare but reduce welfare in the importing country due to import surges. In this case, countervailing duties11

are useful in preventing foreign firms from gaining the first mover advantage in the domestic market.

Contingent Protection - Countervailing Duties

Barcelo III (1977) exposes the trade principle behind countervailing duties observing that the inadequacies of free economies may require government intervention from time to time. While the intervention can be in the form of subsidy to domestic production and export subsidies, it is the former that is more effective from efficiency point of view. Bown(2010b) analyses

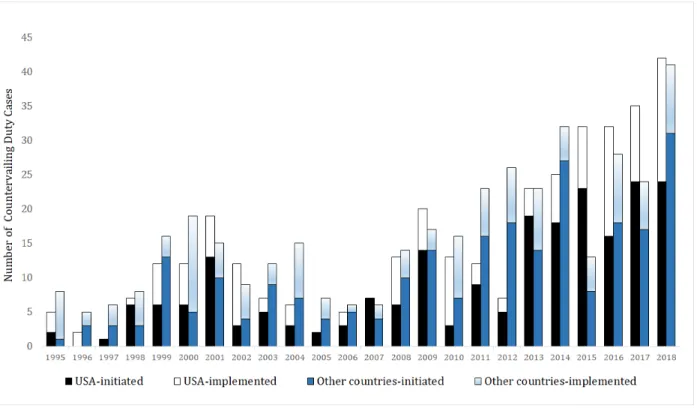

Figure 4: Trading nations’ use of countervailing duties, 1995-2018

Source : Author’s calculation fromWTO (2019e)

this view further suggesting that there was a potential shift towards governments relying on the countervailing duty (anti-subsidy) policy triggered mainly due to two events: (1) China’s WTO accession in the face of its continued export expansion; and (2) the global policy response to the financial crisis of 2008–09 which led to a number of government-financed industry bailouts. These government support measures in the form of subsidies could be addressed through countervailing duties by trade partners. He also notes that while in the 1990-2009 period the US was the major user of countervailing duty provisions, several other WTO member economies (India, China, Turkey) have implemented new countervailing duty legislation and enhanced their use of this statue (See Figure 4). China’s purported ‘currency manipulation’ has often led to the rise in concerns of acting as an export subsidy which may lead to a surge in countervailing duty cases by other countries (Staiger and Sykes, 2010) and therefore, amongst the other countervailing duties-imposing economies in the G20, there is strong evidence of the simultaneous use of countervailing duties alongside anti-dumping. The overall growth in countervailing duties could be troubling since it indicates either of the following two practices: 1) subsidies are growing or, 2) countervailing duties are being employed against a wider range of subsidies suggesting an increasingly protectionist deportment (Marvel

and Ray, 1995). Since Marvel and Ray’s commentary in 1995, countervailing duty cases have been on a rise, although not commensurate to the number of anti-dumping cases worldwide. Also, it is worth noting that the US is a major user of countervailing duties in the world with its countervailing duty implementations since 2014 exceeding the countervailing duty initiations by all other countries combined (Figure 4).

Contingent Protection - Safeguards

Figure 5: Trading nations’ use of safeguards (by sector), 1995-2018

Source : Author’s calculation fromWTO (2019e)

Safeguards12 are contingent protection measures used by trading nations to (temporarily)

protect a specific domestic industry from import surges that cause (or threaten to cause) material injury to the domestic industry. The GATT formalised the ‘insurance’ needed to make free trade politically acceptable in Article XIX which allows safeguards to be levied if import surges threaten domestic industry (Stiglitz, 1997). A few select sectors have seen intensive use of safeguards (Figure 5). These are the base metals, chemicals and ceramics categories. Since China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, there have been China specific safeguards imposed by countries. These account for 17% of the total safeguard cases filed between 2002 and 2012 (author’s calculation from Bown (2016)).

12While safeguards are not the focus of this dissertation (because of their non-bilateral nature), this short

Countries have been more restrained in their use of safeguards, probably because of the relative ease of using anti-dumping and countervailing duty petitions (Bown,2010a). Also, safeguards may be less popular because using them might signal the admittance that a country’s domestic industry is not competitive (Niels,2000).

Consequences of contingent protection

Empirical studies seem to support the theoretical argument that flexibilities are needed in trade agreements. These flexibilities help in addressing possible difficulties that may not be envisaged at the time of signing the agreement. Contingent protection measures are a step in that direction and research suggests that they are more likely to be used when countries are undergoing difficult economic circumstances. However, researchers have not disbared the possibility of these measures being used as protectionist tools invoking numerous consequences (WTO,2009). With the rapid proliferation of contingent protection policies, the effects or consequences that arise from them have been scrutinised in several studies.

Vandenbussche and Viegelahn (2011) categorise the use of several indicators that capture direct effects of contingent protection policy (in this case anti-dumping). These are product coverage, country coverage and product-country coverage, all coded as count measures. Studies with a core partial equilibrium nature have focused on the product level directly affected by contingent protection actions. For example, Krupp (1994) examine the use of anti-dumping in the US chemical industry to find a positive link between import penetration and price-cost margin with petitioning activity. In a recent paperChandra(2019) investigates the effect of US anti-dumping duties on the exports of Indian multi-product firms and find that firms affected by US anti-dumping duties increased the number of products exported to other destinations by about 0.7 products, on average.

Vandenbussche and Zanardi (2010) also expand to a general equilibrium approach by looking at the aggregate effects of contingent protection where a mixture of effects is likely to be at play. They identify indirect effects on trade flows like trade destruction, trade creation (via import source diversion), trade deflection and trade depression13 due to contingent protection.

13If country A takes a contingent protection measure against B, there are four possibilities of trade flows

between A, B and third country C :

1) trade flows (relative to free trade) from B to A can reduce (trade destruction), 2) trade flows (relative to free trade) from B to C will increase (trade deflection), 3) trade flows (relative to free trade) from C to B can reduce (trade depression) and,

4) trade flows (relative to free trade) from C to A increase (trade creation via import source diversion) (Bown and Crowley,2007;Vandenbussche and Zanardi,2010)

Research has also delivered the following potential channels through which contingent pro-tection can administer consequences on trade. These are : downstream effects (negative impact on downstream products like cars due to protection in intermediate sectors like steel (Krupp and Skeath, 2002)), deterrent effect (making trade partners more cautious when shipping their goods to countries that signal to be frequent and tough users of contingent protection (Blonigen, 2006)), collusive device (formation of international cartels and tacit collusion (Prusa,1992;Zanardi,2004)), FDI effects (exporters may decide to evade contingent protection by setting up a production plant within the protected market (Blonigen, 2002;

Cole and Elliott, 2005), retaliation effects (political and strategic considerations related to the use of contingent protection laws (Blonigen and Bown, 2003; Feinberg and Reynolds,

2006,2018;Skeath and Prusa, 2001)).

Thus, the effects or consequences of trade protection could have short as well as long term reach for a country’s macro-economy and often the global economy (Vandenbussche and Zanardi,

2010). This becomes particularly important for countries that seek to access developed markets where restrictiveness of non-tariff measures is higher. Therefore, three broad conclusions can be drawn from the literature on the consequences of contingent protection. First, use of contingent protection is a highly political process and creates vested interests not only among protected industries and their political representatives, but also among the officials and lawyers directly involved in the policy (Niels,2000). Second, ‘chilling effects’ of protectionist policies are measurable even before a duty is imposed (Vandenbussche and Zanardi, 2010). And third, evidence is mixed on the effect of trade flows between countries that impose protectionist polices, the target of these protectionist measures and third countries14.

At this juncture, it is important to enunciate that this dissertation does not study the conse-quences of contingent protection. This dissertation explores the determinants of contingent protection and attributes their genesis to factors other than only trade. Nevertheless, we believe, a fundamental discussion on the consequences of contingent protection was worthwhile to inform the debate on the motivations of the same. This is in line with the observations of Gawande et al. (2015) who point out that quantitative evaluations of the consequence of protection on trade flows cannot be decoupled with the understanding of the determinants of trade policy in the first place. In that vein, this dissertation is an attempt to uncover the atypical factors that play a role in nations’ activity of contingent protection.

14A priori, the effect of contingent protection proliferation on trade flows remains unclear. Imports are

likely to be reduced in an equilibrium scenario of all countries use contingent protection. Alternatively, the proliferation of contingent protection laws may result in a politically optimal equilibrium where the capacity to access these laws induces a cooperative equilibrium (Bagwell et al.,2016).

Outline of the dissertation

The literature on contingent protection measures, specially anti-dumping duties, is fairly mature with significant contributions over the past three decades related to key questions from when and why dumping occurs to its overall welfare effects. However, there is scant attention to several new issues which although developed by trade theory have not found coverage in the contingent protection literature (Blonigen and Prusa,2016). For example, which group of countries use contingent protection as a strategic tool to retaliate and in which sectors? Why do some countries take a more belligerent stand and does this have to do with the leadership or representation of the country? Do countries use development assistance as a ‘carrot and stick’ approach to induce desired behaviour in the recipient countries who become competi-tive trading partners? This dissertation is an attempt to address these under-scrutinised issues. This dissertation is a collection of three empirical studies in international trade focusing on the use of contingent protection measures by trading nations. However, it can be advocated that it comes under the realms of development economics since trade protection has percolated into the developing countries, not only as targets but also as petitioners. It is an attempt to examine the trends in use of protection, consequently evoking discussion on welfare-enhancing alternatives that would be a useful direction for research. Each paper consists of a detailed literature review, and therefore here, we only briefly describe the motivations, theoretical backdrop, empirical methodology and key findings of each chapter.

What determines trade protection?

Chapter 1: Protection begets protection?

The first chapter titled Protection begets protection? is aimed to uncover the role of strategic motives like retaliation when using Anti-dumping duties. It is to be noted, in this chapter, we focus only on anti-dumping policy as it is the most conspicuous of all trade policies in terms of retaliatory behaviour15. It seems that anti-dumping has found a favour for

countries wanting subtle protection due to its unique combination of political and economic manipulability, incentives, and intrigue (Blonigen and Prusa, 2001). Blonigen and Bown

(2003) develop theoretical models to exhibit the potential channels of retaliation involved in Anti-dumping cases. They suggest that effective retaliation requires a combination of having

15To avoid noise in this particular analysis about the strategic motive of retaliation, we exclude countervailing

duties since the bulk of countervailing duty cases (roughly 66%) are attributed to the USA. Also, safeguards as contingent protection tool, have to be excluded since these are not bilateral but levied product wise.

access to and experience with the GATT/WTO dispute settlement mechanism and having sufficient trade from the home country to engage in a strong enough retaliatory response. To this effect, more recent studies like Feinberg and Reynolds (2006, 2018);Niels and Francois

(2006) find strong evidence that a significant share of anti-dumping filings worldwide can be interpreted as retaliation.

In this chapter, we use data on anti-dumping activity pertaining to 49 active users and their trade partners from 1996 to 2015 (20 years). The focus of this chapter is on retaliation as a motive for further anti-dumping activity. Therefore we construct indicators which capture the retaliatory motives of trading nations. Additionally, to examine the role of anti-dumping as a strategic tool in trade, we have a battery of anti-dumping related indicators to capture the deflected trade, total anti-dumping initiated globally in that particular time period, anti-dumping initiating experience and echoing (a global phenomenon wherein different coun-tries sequentially impose anti-dumping measures on the same product from the same exporter). This chapter finds that on an aggregate (country level), retaliation is not a strategic motive for anti-dumping petitioning. However, for sub-samples based on income levels, size of trade and regions, a very heterogeneous contour is evident in terms anti-dumping case filing behaviour. Lower and upper middle income countries show a positive correlation between current anti-dumping petitioning and past anti-dumping against them by a trade partner, in other words, retaliatory anti-dumping. This is also true for East Asia & Pacific region probably due to the presence of China and South Korea.

At an aggregate level, it would not be crystal clear why countries would retaliate using an anti-dumping petition against a country which has targeted it in a particular industry section. To investigate this, this chapter includes a dis-aggregated analysis of anti-dumping activity, i.e. at the sectoral level. In the sectoral analysis, we find that the coefficients are positive and significant at the 1% level for a select group of large importers (constituting of both traditional and new users of anti-dumping) indicating that at a sectoral level, retaliation does determine anti-dumping activity.

The timing of retaliatory action by an importer, which is in direct response to past anti-dumping activity by the exporter, raises concerns of a potential trade war and hence can be suggestive of retaliation being a significant motive behind Anti-dumping activity. Overall, in this first chapter, we corroborate the views of researchers like Feinberg and Reynolds(2018),

suggest that retaliation as a strategic instrument substantially affects present anti-dumping activity. Taking a deeper dive into the sectoral break-up, this chapter uncovers that while at the aggregate level retaliation does not seem to be a significant motive, it is deployed at the sectoral level by both traditional (developed economies) and new users (emerging economies) of Anti-dumping.

Is trade policy design different when the leader of a country is a

woman?

Chapter 2: Are only men fighting trade wars?

The question whether leaders matter for economic growth is as familiar as it is difficult to fully answer. In this chapter we pursue the idea that characteristics of a country’s leader - in this case gender - are important for policy design including trade policy. Literature suggests that trade affects men and women differently. This is attributable to men and women having different economic and social roles and different access to and control over resources, due to socio-cultural, political and economic factors. With this in mind, policy makers as well as researchers have been burdened with making gender responsive trade policies. While all this debate happens at the level that trade and trade policies affect women as entrepreneurs, traders or workers, there is a dearth of research on the role of women leaders as designers of trade policy. In this second chapter, titled Are men fighting the trade wars?, we investigate the role of national leadership, specifically women, in the propensity to instigate trade protectionist measures (anti-dumping and countervailing duties).

First, we build a theoretical model based on game theory with the role of threat being consequential to players’ decisions to initiate or curb protectionist countermeasures. The threat from a woman leader maybe deemed non-credible (Dube and Harish, 2020) leading to the continuing of a ‘harmful’ trade action from the partner country (like dumping or subsidising exports). To counter this, a woman leader is left with no other option but to instigate a petition under the disciplines of the WTO. Within the realms of psychology studies, this behaviour is termed as ‘male posturing’ when a woman is required to act as male to make her threat seem credible (Caprioli, 2000).

Second, using empirical analysis for the trading nations that have used contingent protection in the 21 year period between 1998 and 2018, we find that a woman head of government increases the propensity of a country to file a contingent trade protection case against a trading

partner at the WTO forum. This varies significantly from the behaviour of women leaders at the mass level, i.e. as members of parliament, since their credibility at an international level is not put to test (unlike that of the woman head of government). Women parliamentarians are less likely than men to support the use of contingent protection and our results show that increasing percentage of women in parliament has a moderating effect on the use of contingent protection, irrespective if the chief office holder is a man or woman. In this chapter we also include controls for important ministries that may seem to have a link with trade policy design, for example, the foreign affairs and finance ministries.

To sum up, this chapter is a novel investigation into the role of national leadership, specifically gendered role, in the use of contingent protection. When it comes to protectionist policies, women leaders seem to be equally likely (or more) to initiate trade conflicts. This is of course governed by the role of the office a woman leader holds and the economic performance of the country she is leading.

Growing protection on the sidelines of development aid

Chapter 3: Medicine with side effects - Aid for trade and targeted protection

In the third chapter titled Medicine with side effects, we investigate the under-examined issue of the relationship between Aid for Trade (AfT) and contingent protection. Inspired by

Nunn’s commentary (2019) on rethinking economic development, this is a novel study that asks whether donor nations open their markets to developing nations who are recipients of their AfT assistance?

In this chapter, the theoretical motivation is guided by the work of Lahiri et al.(2002) who suggest that in cases when level of aid is decided before level of tariffs, aid induces the recipient to more open trade policies giving an incentive to the donor to choose aid first. Subsequent increase in trade flows between the two countries now depends on what the donor country does in terms of providing market access to the recipient. The first part of the analysis carried out in this chapter deals with the USA as donor (and contingent protection user). We find evidence that USA’s contingent protection activity increases against a country which has been the recipient of its Aid under the AfT programme in the previous year. Our conclusion stands up for a battery of robustness tests based on regions, income level of recipients and different presidential regimes. Also, to eliminate doubts of potential endogeneity between aid and trade, we use instrumental variable approach and find that our results remain consistent.

This chapter also finds that between Economic Infrastructure & Services and Production medium (the two broad trade related categories in the Official Development Assistance data classified by the OECD), it is the former that is the significant medium. Subsequently, this study is expanded to other donors and a variegated response of each donor is observed.

Data quality and availability

This dissertation is a work on non-tariff measures and relies extensively on data by the WTO

(2019e) for indicators related to contingent protection cases. Data on contingent protection (initiations and final measures) is available from 1995 to 2019 for 49 reporting economies and 106 trade partners. This data is at the country-level and is reported as a count of the number of cases initiated against an exporter. TheWTO (2019e) collects this data passively as all members are required to submit reports regarding contingent protection measures regularly16 under agreed regulations. Although there are limits in terms of translation and

interpretation bias due to mismatches in language and training of data reporters in each country, the Anti-dumping data from the WTO, at least as the count of cases per year, have become comprehensive (UNCTAD,2017).

For sector (industry) level data (Chapter 1) we use the Temporary Trade Barriers Database (TTBD) by Bown (2016) which covers over 95% of the global use of anti-dumping,

coun-tervailing duties and safeguards. The temporal coverage of TTBD is from 1995 to 2015 for 51 reporters (including the Gulf Cooperation council and the European Union as single entities). This dataset provides sector classification for each contingent protection case filed by the reporters. The TTBD compiles information extracted from national government legal texts and other communications dealing with the respective measures and mapped to the Harmonized System (HS) product codes. Analogous to any data compiled using national registers or reports at the sector or product level, the data in TTBD could also be girdled with common problems like the following. First, the data could have deficiencies due to problems of ‘non-reporting’. Second, it is possible that the data provided in the national government legal texts and other communications may not be coded according to the nominated classifications and categories. Therefore, while the TTBD efficiently tracks each contingent protection case number wise, there could be gaps in product and duty value coverage. Our study does not deal with duty value, however, for missing product fields (252 individual cases) WTO 16For anti-dumping, as per article 16.4 of Agreement on Implementation of Article VI of the General Agreement

on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), members are required to submit a report of all anti-dumping actions they have taken, as well as a list of all anti-dumping measures in force, twice a year. For countervailing and safeguard measures, as per Article XIX of GATT, members are required to notify investigations and applications of measures to relevant committees.

Antidumping Agreement resources were perused to update the product fields.

Regarding temporal coverage, the TTBD is available till 2015 posing a limit for our sectoral analysis in Chapter 1. In Chapter 2 we have a temporal coverage from 1998 to 2018. However, this is because of the unavailability of data related to percentages of women in parliament which is a key independent variable. Similarly, in Chapter 3, the measures for key independent variables related to foreign aid are available 2001 onward and therefore our sample ranges for period 2001 to 2018. In summary, our three studies were planned to study the period starting from the establishment of the WTO (1995)17 till the most recent

year (2018). However, temporal coverage in each chapter stands altered depending on the availability of key independent variables as mentioned above.

For remaining indicators used in this dissertation, data related information is provided in further detail within the chapters.

Contributions

In summary, this dissertation makes contributions to the existing literature in the following aspects. First, it adds insights to the often questioned motives of initiating contingent protection by considering the role of retaliation in current filings of anti-dumping cases. More precisely, it complements previous evidence on the impact of strategic motives in initiating contingent protection (Bown and Crowley, 2007; Feinberg and Reynolds,2006, 2018), and explores the role of industry in petitioning actions. Second, it contributes to the scarce stream of research on the impact of national leadership on contingent protection as a trade policy instrument. Third, this dissertation furthers our understanding on the subtle, yet strong, linkages between foreign policy and trade policy. The effectiveness of foreign policy instruments like Aid for Trade has seldom been discussed from the standpoint of ensuing contingent protection and our results are compelling evidence suggesting that ‘aid is seldom purely altruistic’.

With the aforesaid, the inferences in this dissertation have two important general implications: first, they provide deeper insights into the extant topics like determinants of contingent protection. Second, they raise neoteric and original questions on the intertextuality between trade policy, development, and political economy.

17The number of cases filed has significantly increased since the establishment of the WTO (1995) due to the

Chapter 1

Protection begets protection?

Role of retaliation in anti-dumping case filing

1.1

Introduction

Finger (1992) in his seminal work titled Dumping and Anti-dumping: the rhetoric and the reality of protection in industrial countries said, “Anti-dumping is ordinary protection with a grand public relations program”. His reasoning is straightforward when he says that anti-dumping is the fox that is in-charge of the hen-house. In other words, foreign anti-dumping is the rhetoric used by trading nations to excuse contemporary protectionist measures. Whilst with an original objective of curtailing ‘unfair trade’, contingent protection measures provisioned by the World Trade Organisation, are increasingly becoming the means of introducing trade distortions.

A vast body of literature has explored the motivations for anti-dumping usage and its proliferation in developed and developing trading nations alike. A result that emerges from these studies is that the strategic motive of retaliation is a key factor contributing to the growth in anti-dumping regimes (Blonigen and Bown, 2003; Blonigen et al., 2000; Feinberg and Reynolds, 2006, 2018; Prusa and Skeath, 2004). This chapter fits into this broader area of anti-dumping literature that focuses on prevalence of retaliation amongst users of anti-dumping. However, this chapter contributes to literature in the following aspects. In the first place, it vastly expands the scope of study by using a large sample of contingent protection users since the formation of the WTO. To be precise, we look at the determinants of anti-dumping use intensity among the users of contingent protection with a special focus