MITLIBRARIES

*

/

\

*

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

5

1

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

Did

Firms

Profit

from

Soft

Money?

Stephen

Ansolabehere

James

M.

Snyder,

Jr.Michiko

Ueda

Working

Paper

04-1

1January 2004

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper

can

be

downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection atMASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTPJ __

OF TECHNOLOGY

DID

FIRMS PROFIT

FROM

SOFT

MONEY?

Stephen Ansolabehere

Department

of

PoliticalScience

MIT

James

M.

Snyder, Jr.,Departments of

Political Scienceand

Economics

MIT

Michiko

Ueda

Department

of

PoliticalScience

MIT

January,

2004

The

authorsthank

William

Burke

for hisexcellent researchassistance. ProfessorAnsolabehere

At

its heart,the BipartisanCampaign

Reform

Act

seeksto limit theprivate benefits thatfirmsreceive

from

campaign

contributions.A

seriesof

rulingsby

the Federal ElectionCommission

createdthe opportunity fororganizationsand

individualsto give funds topartyaccounts outside the

system of

direct contribution limits-

so called softmoney.

Although

littleused

before 1992, softmoney

ballooned during the 1990s. In the2000

election, thetwo

major

parties raised

approximately

$500

million in softmoney, most

of

which

came

from

corporations indonations in excess

of

$100,000, at leastten times largerthan thehard

contribution limits set in theFederal Elections

Campaign

Act.Companies were

widely

alleged tohave

profited directlyand

substantiallyfrom

their softmoney

donations. In theyears leadingup

tothepassage

of

BCRA,

public interestgroups and

thepress

provided

numerous

examples of

firms thatbenefitedfrom

public policiesand

were

also largesoft

money

donors

-

tobacco, pharmaceutical,and

oilcompanies

were

especially featured in thesereports.

The

most

telling evidence,cited extensivelyby

themajority opinioninMcConnell

v.FEC,

emerged

in hearings before the U.S. SenateCommittee on

Commerce

in 1998. Corporateexecutives

and

legislators testified that softmoney

donationswere

oftengiven

when

valuablegovernment

contractswhere on

the line. In othercasesdonors

feared that, ifthey didnotcontribute, then their

companies

would

losecompetitiveadvantages through

regulations.These were

clearlystoriesof

excess. Partiesand

their candidates received donations well inexcess

of

what

they couldraiseunder

the hardmoney

limits,and

corporations,which

gave

most

of

the softparty

money,

allegedly received excessively largebenefits atpublicexpense

inreturn fortheircontributions.

SeethereportbytheFederal ElectionCommissionat:

Were

these cases typical, or exceptional? Ifexceptional, thenthegovernment might

bestdeal

with

theproblems of

corruptpracticesthrough

aggressiveenforcement of

anti-bribery laws. Iftypical, then the

government

might

attempt to eliminatetheseproblems with

blanketrestrictionson

contributions

-

as theyin fact did.At

issue is the extent towhich

donors, especially large corporate donors, benefitedfrom

softmoney.

Economists

and

political scientistshave

longbeen puzzled

aboutthe influenceof

campaign

contributionson

publicpolicy.An

extensive literatureexamines

the associationbetween

hard

money

contributionsand

publicpolicy decision-making,

especiallyroll callvoting inthe U.S.Congress.

The

largemajorityof

studies findno

significant effectsof hard

money

contributionson

publicpolicy, and, inthose that

do

findsome

association,themagnitude of

theeffects is typicallyvery small.

More

troubling still,the totalamount

of

campaign

contributingseems

too small toproduce

much

influence.Tullock

(1973)observed

that although corruption iswidely

alleged, it isnotplausibly large.

Assuming

areasonable returnon

investment,the total valueof

allgoods and

services that firms

buy

with

theircampaign

contributions cannotbe

more

than a severalhundred

milliondollars peryear.

That

might sound

like alot, butit isrounding

erroron

the nationalaccounts,

and

likelydoes

notamount

to a significant societalproblem.

On

the otherhand,such

calculationsmay

be wrong.

Under

some

assumptions aboutthenature

of

political bargaining,companies might

command

an

extraordinarilyhighreturnon

investment (e.g.,

Persson and

Tabellini, 2002,pp. 187-190;Dal Bo,

2002).And

there areafew

empirical studies that claimto find evidence for

such

highreturns(e.g., Stratmann, 1991).Is there

evidence

that firmsprofited substantiallyand

systematicallyfrom

their softmoney

donations?

We

know

of no

studythat has looked fora systematicrelationshipbetween

softmoney

donations

and

policy decisions oroutcomes.

We

address thisquestionhere,by

examining

corporate stock returns.

The

Bi-PartisanCampaign

Reform Act

itselfprovides a lensthrough

which

toobserve

thevaluethat firms' derived

from

softmoney.

Ifcompanies

profitedfrom

softmoney,

then investorsinfirms should

have valued

the firms accordingly.Companies

thatgave

softmoney

and

receivedundue

competitiveadvantages

or largecontractsin return shouldhave been

better investmentsinrecent years than

companies

thatgave

little sofimoney.

By

thesame

reasoning, theimpositionof

new

regulationsand

the Court's decisiontouphold

thoseregulations shouldhave lowered

the valueof

the firms thatused

the softmoney

loopholes forprofit.Consider

atypicalFortune

100

company. Annual

revenues

forthesecompanies

are,on

average,

$50

billion,roughly

10%

of

which

is profit.Large

firmsthat give softmoney

contributions (not all do) give

an

averageof about $500,000 over

two

years.An

excellent returnon

this investment

would

double

theamount

invested. Thiswould

account

forjustone one-hundredth

of

one

percentof

thecompany's

two-year

profit-

difficult tonoticeand

notmuch

to get excitedabout.

The

fear,however,

is thatcompanies

receivereturnsthousands

of

times largerthan theinvestment.

Suppose,

forexample,

that$500,000

in softmoney

donationsyields $1 billionworth

of

contractsand

services,and

$100

million in profits. Thiswould

represent a20,000

percentreturn,

and

would

account

for 1 percentof

acompany's

annual

profit.The

eliminationof

softmoney

would

eliminate this streamof

profit. Inthe first case,where

returns

on

investmentaremore modest

and

where

the total valueof

goods and

servicesbought

isrelatively small, the effect

on

acompany's

stockpricewould

be

negligible-

intherange

of

one

cost

of

softmoney

togovernment

and

societymight be

substantial, theeffectof banning

softmoney

would

be

tolower

thestockvalueof

thehypothetical firmby

about 1 percent.We

canexamine

the effectsof

BCRA

using stockmarket

dataand

standard event studymethodology.

3 Previous papersby

Roberts

(1990a, 1990b),Fisman

(2001),Jayachandran

(2002),and

othershave found

that politicalevents-

such

asthe deathof

SenatorHenry

(Scoop)

Jackson

in1983 and

SenatorJames

Jeffords' party switchin2001

-

can

have

a noticeableimpact

on

stockprices.

One

importantprerequisite forconducting

an

event studyisthe abilitytodetermine

thedateof an

event thatreleasesnew

information into the market.We

are especially fortunate in thisregard

because

we know

preciselythe dateof

theSupreme

Court's decisionon

BCRA:

December

10, 2003.

Moreover, because

theoutcome

was

uncertain until theverymoment

thecourt revealedits decision,

new

informationwas

clearlyreleased tothemarket

that day.While

it isdifficult toknow

exactlyhow much

of

a "surprise" the decisionwas,

the fact that almostno

observerswere

willingto

make

predictions suggests thatthey believedthe courtwas

aboutas likelyto strikedown

the

BCRA

as itwas

touphold

it.4

An

example

of

the tentativecommentary

offeredby campaign

finance

law

experts is the following,by

ProfessorMichael

C.Dorf

of

theColumbia

UniversityLaw

School:

"The

four-houroralargument

inMcConnell

indicated,above

all, that the Justicesremain

deeply

divided overhow

toapproach

campaign

financeregulation... Itwas

notclearfrom

thelengthyoral

argument

which

of

theseviews

willprevail. Indeed, itwas

noteven

clearwhat

legalstandard

would

be used

tojudge

the challenged provisionsof

BCRA."

5The day

afterthe decision,SeeSchwert(198

1)foradescriptionofthemethodandasurveyofpapers employingit.

As

consultantson thiscase(Snyder onthe sideopposedtotheBCRA

and Ansolabehere onthe sideinsupportofit), twooftheauthorshaddetailedknowledgeoftheproceedingsandfollowedthelitigationclosely. Boththoughttheplaintiffsweremorelikelytoprevail. 5

Quotedfromanarticleonthe

CNN

web

site,September 19,2003,"The SupremeCourt'scampaignfinance reformcampaign

finance expertThomas

Mann

said: "Yesterday, [theSupreme

Court

reached] another 5:4decision that surprised

many,

although, certainly, not allmembers

of

this panel, in thereachand

clarity

of

its findingson

the BipartisanCampaign

Reform

Act."6Other

piecesof evidence

supportthis view.

The

finalvoteon

BCRA's

softmoney

provisionswas

as close as possible, 5 to4.At

theoral

arguments

inSeptember,

Justice Rehnquist, thoughttobe

pivotalon

this matter, subjectedthedefense to hostile lines

of

questioning,which

signaled his likelyvote againstupholding key

provisions

of

the Act.7And many

observersfindthat JusticeO'Connor,

anotherpivotaljustice, is"even

more

inscrutable than usual"on campaign

finance questions. 'The

prediction, then,is straightforward: Ifsoftmoney

donationsproduced

profitsand

BCRA

stopped

them,

then the stockpricesof

companies

thatused

softmoney

heavily shouldhave

fallen

on

December

10,2003,

while those thatdidnot should eitherhave

risenorbeen

unaffected.In additionto the

Supreme

Court's final decision,therewere

four other eventssurrounding

BCRA

thatmight have

surprised themarket.Thus,

we

have

five events in all. (1)The

U.S.House

passed

thebillon

February

14,2002;

(2) theSenate

passed

iton

March

20,2002;

(3)thepresidentsigned thebill into

law

on

March

27,2002;

(4)theSupreme

Court

heard

oralargument

on

6

BrookingsBriefing,"SupremeCourtRuleson CampaignFinanceCase:TheLegalandPolitical Impact ofMcConnell

v.

FEC"

December

11, 2003.See, forexample,the WashingtonPostarticleon

Aug

31,2003byCharles Lane,"RehnquistMay

BeKey

forCampaignFinanceChiefJustice'sPastVotesLeave

Outcome

ofChallengesto McCain-FeingoldLaw

Uncertain."QuotebyProfessor

Roy

Schotland oftheGeorgetownUniversityLaw

Center,from Washington PostarticleonAug

31,2003 byCharles Lane,"Rehnquist

May

Be Key

forCampaignFinanceChiefJustice'sPastVotesLeaveOutcomeofChallengestoMcCain-Feingold

Law

Uncertain."Anotherinterestingpieceofevidenceisthe

BCRA

"market"runforan undergraduate courseontheSupremeCourtattheUniversityof NorthCarolinaatChapelHill. About 130studentsinthe classtradedinthemarket,rewardedwith grades. Thebettingwason whetheror nottheelectioneeringcommunicationprovisionswouldbe upheld. Thelast

pricesatwhichtradestookplace,postedon December8,were$.55forthepositionthattheprovisionswouldbe upheld and$.55forthe position that theprovisionswouldbestruckdown, onbetsthatpaid$1.00-thisimpliesbeliefsvery

September

8,2003

(atwhich, Justice Rehnquist's questioningwas

viewed

as a signal thathe

would

side

with

plaintiffs);and

(5) theSupreme

Court

issued itsrulingon

December

10, 2003.10Following

the event study literature,we

estimatethe following equation, a modificationof

the CapitalAsset Pricing

Model:

J 5

j=\ s=\

where

iindexes firms,t indexesdates,j

indexesdonor

status {e.g., large donor, non-donor),Rii is the return

on

firmj's stock fordate /,M

t is themarket

return for date t,Ay

=

1 iffirm / isatype-y

donor and

otherwise,and l

st=

1 ifs=

tand

otherwise. Ifevents 1, 2, 3and

5produced

"bad

news"

forlarge softmoney

donors, thenthe corresponding ?/sshould

allbe

negativeand

statistically significant;

and

ifevent4 produced

"good

news",

forlargesoftmoney

donors,then thecorresponding

I4 shouldbe

positiveand

statistically significant. (Note,Ru

=

(Pn- Pi,t-i)lPi,t-uwhere

Pitisthe closingprice

of

firmis

stockon

date t.)We

assembled

dataon

dailystock prices forall Fortune500

companies

fortheperiodFebruary

10,2001 through

December

12, 2003.'

'

Some

of

thesecompanies

arenotpublicly tradedand

otherswere

involved incomplicatedmergers

duringtheperiodunder

study-

dropping

thesecases leaves

446

firms.12To

measure

themarket

returnwe

used

theCSRP

value-weighted

return.We

merged

thiswith

dataon

the softmoney

donations for all these firms.1310

Hertzel,Martin,andMeschke(2002) studiedtheimpactofthefirstthreeof these events on thestockreturnsof40 major soft-moneydonors,and found nosignificanteffects. These wereprobablylesssurprisingthanthelastevent.

ThevoteonfinalpassageintheHouse was240-189,andthevoteintheSenatewas60-40;moreover,othereventsthat

occurredduring considerationofthebill

may

have beenequallyimportant,suchas theapproval ofa rulebytheRulesCommitteeon February8,theadoption ofthe rulebythefullHouseon February 13,andtheapproval ofthe

Shays-MeehansubstituteamendmentovertwocompetitorsonFebruary 13.

We

analyzeallfiveeventsforcompleteness.Thefirstdate isexactlyoneyearpriortothefirstof ourfiveevents.

Thetotalnumberofobservationsisthereforenearly 325,000.

Firmstockmarketprice dataandmarketdataarefrom

CRSP

(CenterforResearchin SecurityPrices,attheUniversity of Chicago) andFactiva. Soft

money

donationsarefromthe websiteoftheCenterforResponsivePoliticsThe

Fortune

500 companies

includemany

of

the largest softmoney

donors, as well asalarge

number

of companies

thatgave

little orno

softmoney.

The

ten largest softmoney

donors

overthe4-year period

1999-2002

were

AT&T

($6.8 million), FreddieMac

($6.4million), PhilipMorris

($5.3 million), Microsoft ($4.2 million),SBC

Communications

($3.3 million),Verizon

($3.1 million),

Fannie

Mae

($3.0 million), Pfizer ($2.9 million),Bristol-MyersSquibb

($2.8million),

and

Anheuser-Busch

($2.7 million).On

the other side,an

impressive listof

firmsgave

no

soft

money

at all,includingIBM,

American

ElectricPower,

Intel,ALCOA,

Whirlpool,and

Consolidated Edison.

We

group

firms into three categories,based

on

their total softmoney

donationsover

thetwo

electioncycles

1999-2000

and 2001-2002:

Non-Donors

arethosewho

gave $10,000

or less,Modest Donors

thosewho

gave

between

$10,000 and $250,000; and

Large Donors

thosewho

gave

at least $250,000.

We

alsoconducted

analyses inwhich

we

isolatedMillionDollar

Donors,

who

gave

in excessof

$1 millionover

the4-year period.The

firstgroup

contains216

firms; thesecond

group

contains142

firms,with

an average

contributionof about $90,0000; and

the thirdgroup

contains

142

firms,with

anaverage

contributionof

$1,080,000.There

are50

MillionDollar

Donors.

Were

softmoney

donors

hurtby

theSupreme

Court's decision touphold

BCRA?

The

shortanswer

is: Evidently not.At

theend of

the tradingday on

December

10, the firmsthatgave

softmoney

had had

abetter

day

on

Wall

Streetthan firms thatgave

no

softmoney.

The

valueof

thebroad market

indexdropped

by

about.5% on

December

10th.The

stock pricesof

Large Donors

dropped

by .3%

thattheirvaluethat day.

The

MillionDollar

Donors -

such

asAT&T,

Microsoft,and

PhilipMorris

-saw

theirstocks drop onlyby

.1%. This is exactlythe reverseof our

expectations.The

event study analysisconfirms thisconclusion.Table

1shows

the estimated effectof

the events

on

firms' stockmarket

valuations (i.e., their ?'s) forthe threetypesof

donor

firms.The

events

marking

thepassageof

BCRA

and

the Court'sdecisiontouphold

thelaw had

no

statisticallydiscernable effect

on

the valuationof

firmsthatgave

largeamounts of

softmoney;

i.e., their?'s arestatistically indistinguishable

from

0.What

ismore,

the effectsof

the eventson

firms thatgave

no

soft

money

and

firms thatgave

modest amounts

of

softmoney

were

not statistically differentfrom

firms that

gave

largeamounts

of

softmoney.

Specifically, the F-statistics at the footof

the tablereveal, inthe firstcase, that the?'s forthe different types

of

firms are not significantly differentfrom each

otherand, in thesecond

case, thatwe

cannotrejectthehypothesis thatthe ?'s are 0.That

is,the dataare consistentwith

thehypothesisthatallof

the eventshad

zeroeffecton

thevaluations

of

all typesof

firms, Ifanything, the court'sdecision appearstohave

helpedtheLarge

Donors, and

hurt theNon-Donors -

again,completely

contraryto expectations.In short, theBipartisan

Campaign Reform

Act

did notaffect theprofitabilityof

corporationsthat

gave

considerableamounts

of

softmoney.

There

aretwo

possible interpretationsto these findings.One

possibilityis thatBCRA

willhave

little effecton

behavior. Investorsmight have

expectedthat firms will find away

around

thenew

law. Indeed, theFEC

now

facesnew

challenges in dealingwith

committees

known

as 527'sand

501(c)4's.14We

believe,however,

that thesoftmoney

ban

has teethand

will eliminatethesizable corporate donations that

were

thehallmarkof

softmoney

in the 1990s.A

second,more

profound

possibilityis thatthepremise

of

most

of

the discourseover

campaign

finance is simplywrong.

Firms

may

notcaremuch

about

softmoney

because

theydo

14

not profit

much

from

softmoney

donations.As

noted inthe calculations above,even

iffirmstreatedtheir soft-

money

donations as investments,and

these investmentsproduced

a fairly decentrate

of

return, thetotal effecton

profitswould

be minuscule

and

virtually undetectable in stockmarket

prices.Moreover,

veryfew

firmsgave

largeamounts

of

softmoney.

Anyone

who

has followedthis issue

over

the pastdecade can probably

name

some

of

the large softmoney

donors-

such

asR.J. Reynolds, Philip Morris,

and

AT&T.

But

they arethe exceptions.Only one

in25 Fortune

500

companies gave

in excessof

$1 millionof

softmoney

inthe2000

election,while

40%

gave

no

softmoney

atall,and

halfgave $10,000

orless.The

lackof

apparentfinancial losses associatedwith theend of

softmoney

indicates at thevery leastthatthe

campaign

contributionsdo

not exact exceedingly large returnson

investment.Thousand-

fold returns, as suggestedby

the Senate hearingsand

otheranecdotes, arenotborne

outinthe behavior

of

investors.This conclusion raises

a

problem

with

abasicpremise

intheBCRA.

Isthere acompelling

societal interest in regulating soft

money?

Probably

not. Apparently,we

are notinaworld of

excessivelylarge returns to

campaign

contributors.Firms

do

notappear

toreceive a lot for a little.And,

even with

returnon

investment as large as 100%,

there isvery

littlemoney

inelectionscompared

with thevalueof

allgoods

and

servicesproduced

by

thegovernment.

There

may

be

agovernmental concern

about casesof

corruption.That

concern

seems more

appropriately

handled through

stricterenforcement

of laws

thatprohibitbriberyand

quid proquo

arrangements

(Lowenstein, forthcoming). This concern,however,

is about afew bad

apples. It isLacking

evidenceof

actual corruption, theCourt

reliedheavilyon

concern

about perceivedcorruption. But, in the

absence

of

evidencethat firms profitedfrom

softmoney

orthatthere is anoticeable

economic

costto society,one

wonders

on

what

theperceptionof

corruption is based.And

ifinvestors,who

back

theirperceptions with realhard moneys

—

theirown

—

do

notperceiveReferences

Ansolabehere,

Stephen,John de

Figueiredo,and

James

M.

Snyder, Jr. 2003."Why

IsThere

So

Little

Money

inUS

Politics?"Journal of

Economic

Perspectives 17: 105-130.Dal Bo,

Ernesto. 2002. "Bribing Voters."Unpublished

manuscript, Universityof

California atBerkeley.

Fisman,

Raymond.

2001. "Estimating theValue

of

PoliticalConnections."

American

Economic

Review

91:1095-1102.

Hertzel,

Michael

G., J.Spencer

Martin,and

J. FelixMeschke.

2002."Corporate

SoftMoney

Donations

and

Firm

Performance."

Unpublished

manuscript,Arizona

StateUniversity.Jayachandran,

Seema.

2002."The

Jeffords Effect."Unpublished

manuscript,Harvard

University.Lowenstein, Daniel H.

Forthcoming,

2004."When

Is aCampaign

Contribution aBribe?"

inWilliam

C.Heffernan and John

Kleinig,Privateand

Public

Corruption.Lanham,

MD: Rowman

&

Littlefield.

Persson, Torsten,

and

Guido

Tabellini.2002.

PoliticalEconomics.

Cambridge,

MA: MIT

Press.Roberts,

Brian

E. 1990a."A

Dead

SenatorTellsNo

Lies: Seniorityand

theDistributionof

FederalBenefits."

American

Journal

of

PoliticalScience

34: 31-58.Roberts,

Brian

E. 1990b. "Political Institutions, Policy Expectations,and

the1980

Election:A

Financial

Market

Perspective."American

Journal

of

PoliticalScience 34:289-310.

Schwert, G. William. 1981.

"Using

FinancialData

toMeasure

Effectsof

Regulation."Journal

of

Law

and

Economics

24: 121-158.Stratmann,

Thomas.

1991."What

Do

Campaign

ContributionsBuy?

Deciphering

Causal Effectsof

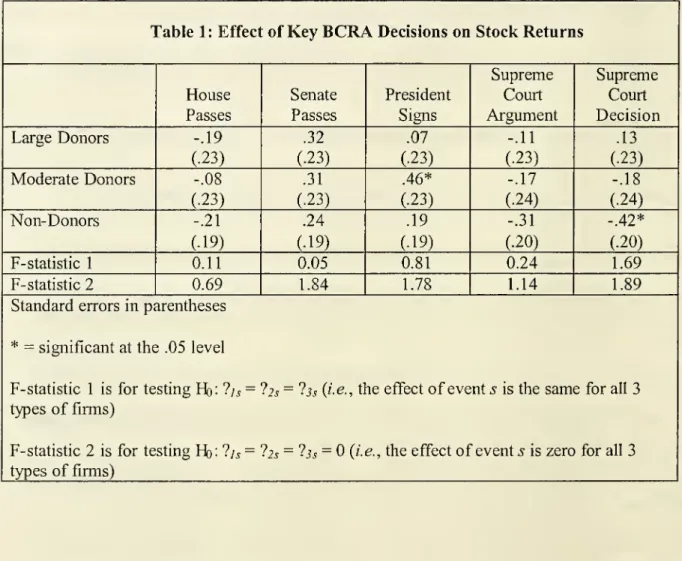

Table

1: EffectofKey

BCRA

Decisionson

Stock

Returns

House

Passes Senate Passes President SignsSupreme

CourtArgument

Supreme

CourtDecision

Large

Donors

-.19 (.23) .32 (.23) .07 (.23) -.11 (.23) .13 (.23)Moderate

Donors

-.08 (.23) .31 (.23) .46* (.23) -.17 (.24) -.18 (.24)Non-Donors

-.21 (.19) .24 (.19) .19 (.19) -.31 (.20) -.42* (.20) F-statistic 1 0.11 0.05 0.81 0.24 1.69 F-statistic2 0.69 1.84 1.78 1.14 1.89Standard errorsin parentheses

*

=

significant atthe .05 levelF-statistic 1 is for testing Ho:?js

=

?2s=

?3.s(i-e., the effectof

events isthesame

forall 3 typesof

firms)F-statistic 2 is for testing Ho: ?is

=

?2S=

?3s=

(i.e., theeffectof

event5 is zero forall 3types

of

firms)MITLIBRARIES

wmmmmmM^MmmMM

1

P