From Clipboards to Annual Reports: Understanding Sport for Development Evaluation Thought and How it is Carried Out

Thèse

Andrew Webb

Doctorat en sciences de l’administration – Gestion Internationale Philosophiæ Doctor (Ph. D.)

Québec, Canada

From Clipboards to Annual Reports: Understanding Sport for Development Evaluation Thought and How it is Carried Out

Thèse

Andrew Webb

Sous la direction de : Frank Pons, directeur de recherche et André Richelieu, codirecteur de recherche.

iii Résumé

But – Le but de cette recherche est de contribuer à la recherche émergente sur l’utilisation du sport pour le développement en cherchant à mieux comprendre la pensée des gestionnaires à l’égard de l’évaluation, ainsi que sur l’influence de ces idées sur leurs opérations. Cette recherche est importante, car a) elle contribue à combler des lacunes dans la littérature académique; b) elle offre une meilleure appréciation du le rôle social important, mais méconnu, que jouent Olympiques Spéciaux Canada; et c) elle fournit une meilleure compréhension que l’évaluation joue dans la construction d’un nouveau normal pour des athlètes vivant avec une déficience intellectuelle.

Méthodologie– La théorie des acteurs-réseaux du Sociologue français Bruno Latour, combinée avec deux méthodes de recherche complémentaires, retracent, en triangulant les données, les connexions sociales des acteurs qui conçoivent et construisent le rapport annuel d’Olympiques Spéciaux Canada. En débutant avec de l’information granulaire sur les athlètes, cette recherche identifie les traces laissées par les acteurs qui planifient, organisent, exécutent et rendent compte de leurs opérations.

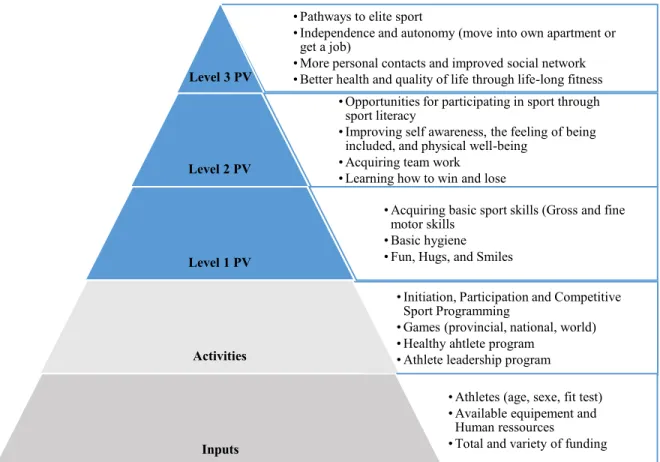

Observations – À travers les mots des acteurs eux-mêmes, cette dissertation démontre que a) les acteurs-réseaux perçoivent que les athlètes obtiennent trois niveaux de valeur ajoutée en participant à leurs programmes; b) collecter, connecter, colliger et communiquer les données sur les athlètes vivant avec une déficience intellectuelle sont nécessaires pour traduire ces données en faits qui sont partagés dans les rapports annuels; et c) que ces valeurs ajoutées perçues ne forment qu’une seule étape dans un processus plus large de construction des faits sur les athlètes vivant avec une déficience intellectuelle. Cette recherche démontre aussi qu’une stratégie de soi-disant « il faut voir pour le croire » permet aux partenaires d’évaluer par eux-mêmes la capacité que possèdent Olympiques Spéciaux Canada d’enrichir la vie des athlètes vivant avec une déficience intellectuelle. Finalement, des nouvelles idées sur les façons dont cette agence rend compte de leurs efforts à travers de rapports annuels sont aussi fournies.

Originalité – L’approche globale traitant de la gestion de l’évaluation dans un programme de sport pour le développement est originale en soi. En outre, cette dissertation est l’une des premières dans ce champ de recherche qui utilise la théorie des acteurs-réseaux du sociologue Français, Bruno Latour. Qui plus est, le modèle actanciel utilisé pour l’étude 1 est aussi une approche novatrice et contribue efficacement à la nature sous-théorisée de ce champ de recherche émergent. Finalement, cette thèse est aussi originale, car il y a actuellement des lacunes au niveau de la recherche sur les agences de sport pour le développement qui opèrent dans des pays industrialisés plutôt que dans un pays en voie de développement, ainsi que sur les programmes de sport pour le développement visant les athlètes vivant avec une déficience intellectuelle.

iv Abstract

Purpose – Within the emerging field of sport for development research, the aim of this study is to better understand evaluation thought and how it is carried out. This research is important because it a) contributes to the numerous gaps in published literature; b) offers better appreciation of the significant, yet often misunderstood, social role of Special Olympics Canada; and c) provides valuable insight about the relationships between evaluation thought, the action of transforming claims into fact, and the construction of a new normalcy proposition for people with intellectual disabilities.

Design – Actor-Network Theory, combined with two complementary research methods, retrace and triangulate the social threads connecting Special Olympics Canada’s annual report actor-networks. Beginning with granular datum about individual athletes, this research slowly follows actors as they plan, organize, conceive, design, implement, and account for their operations.

Findings – Through the actor’s own words, this dissertation demonstrates that a) actors currently perceive that athletes gain three levels of value by participating in their programs; b) that data about athletes with intellectual disabilities is translated into the facts presented in annual reports through collecting, connecting, collating, and communicating efforts; and c) that annual reports accordingly instigate broad evaluation and fact-building efforts. Moreover, this study argues that a so-called “seeing-is-believing” strategy allows partners to evaluate the specific fact that sport enriches the lives of athletes with intellectual disabilities for themselves. Finally, new insights were also obtained about how this agency provides accounts of their efforts to enrich the lives of athletes with intellectual disabilities.

Originality – The focus on evaluation management in sport for development is novel in itself. However, this is also one of the first studies in the emerging field of sport for development research to use the proven actor-network theory. Moreover, the complementary actantial model used in study 1 is similarly a new research methodology applied to this research field and contributes to addressing the under-theorized nature of this emerging research field. Finally, this thesis is also original as there is currently a dearth of published research on sport for development organizations that operate in the global north rather than the global south as well as on sport for development programs for athletes with intellectual disabilities.

v Contents Résumé ... iii Abstract ... iv Contents ... v Figures ... viii Tables ... ix Acknowledgments ... x Préface ... xii

1. Understanding Sport for Development Evaluation Thought and How it is Carried out. An introduction . 1 1.1. Research Problem and Objectives ... 3

1.1.1. Research objectives and justifications. ... 4

1.2. Introducing Special Olympics Canada ... 6

1.3. Justifications From Literature ... 10

1.3.1. Findings: Unpacking evaluation thought in SFD research. ... 11

1.3.2. Discussion: Unearthing concepts that justify this study. ... 16

1.3.3. Synthesizing justifications drawn from the literature. ... 22

1.4. Methodology ... 23

1.4.1. Linking the ontological, epistemological and methodological justifications for the research. 23 1.4.2. Research procedures. ... 30

1.4.3. Synthesizing the method. ... 35

1.4.4. Ethical considerations. ... 36

1.5. Outline of the Thesis ... 38

1.5.1. Study 1 - An actantial analysis of Special Olympics Presidents’ letters. ... 38

1.5.2. Study 2 - Special Olympics Games: Activating sport for development partners. ... 38

1.5.3. Study 3 - Down to the datum: Special Olympics Canada evaluation in action. ... 38

1.6. The End of the Beginning – Conclusion of the Introduction ... 40

2. Study 1 - An Actantial Analysis of Special Olympics Presidents’ Letters ... 41

2.1. Abstract ... 41 2.2. Introduction ... 42 2.3. Literature Review... 45 2.4. Research Design... 51 2.5. Findings ... 54 2.5.1. Desire axis. ... 54 2.5.2. Power axis. ... 56 2.5.3. Transfer axis. ... 57 2.6. Discussion ... 58

2.6.1. The importance of relationships. ... 58

2.6.2. Focusing on Bestowers... 60

vi

2.7. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research ... 64

2.8. Conclusion to Study 1 ... 66

3. Study 2 - Special Olympics Games: Activating Sport for Development Partners ... 68

3.1. Abstract ... 68

3.2. Introduction ... 69

3.3. Literature Review... 72

3.3.1. Background ... 72

3.3.2. Transforming claims into fact. ... 73

3.3.3. The influence of Games and spectacle. ... 74

3.4. Research Design... 78

3.4.1. Actor-Network Theory. ... 78

3.4.2. Data collection and analysis. ... 79

3.5. Findings ... 81

3.5.1. Creating opportunities for connecting. ... 81

3.5.2. Relationships as a collective of threads. ... 83

3.5.3. Presenting a new normalcy for athletes with intellectual disabilities. ... 84

3.6. Discussion ... 88

3.7. Limits and Avenues for Future Research ... 93

3.8. Conclusion to Study 2 ... 95

4. Study 3 - Down to the Datum: Special Olympics Canada’s Evaluation in Action ... 97

4.1. Abstract ... 97

4.2. Introduction ... 98

4.3. Literature Review... 100

4.3.1. Actor-Network Theory (ANT). ... 100

4.3.2. Theoretical impacts of sport for development. ... 101

4.4. Research Design... 104

4.4.1. Analyzing the data. ... 106

4.5. Findings ... 108 4.5.1. Phase 1: Collecting. ... 108 4.5.2. Phase 2: Connecting. ... 113 4.5.3. Phase 3: Collating. ... 115 4.5.4. Phase 4: Communicating. ... 117 4.6. Discussion ... 119

4.7. Limits and Avenues for Future Research ... 123

4.8. Conclusion to study 3 ... 125

5. Understanding Sport for Development Evaluation Thought and How it is Carried out ─ Implications, Limitations, Recommendations for Future Research, and Conclusion ... 127

5.1. Summarizing the Findings ... 127

5.1.1. Study 1 - An actantial analysis of Special Olympics Presidents’ letters. ... 127

vii

5.1.3. Study 3 - Down to the datum: Special Olympics Canada evaluation in action. ... 128

5.1.4. Overall key findings. ... 128

5.2. Theoretical Implications ... 131

5.3. Managerial Implications, Limitations, and Recommendations for Future Research ... 133

5.3.1. Managerial implications. ... 133

5.3.4. Brand confusion. ... 137

5.3.5. Leveraging the partnerships. ... 138

5.3.6. Special Olympics and Canada’s First Nations. ... 138

5.4. Overall Conclusion ... 140

viii Figures

Figure 1 Summarized research methodology ... 36

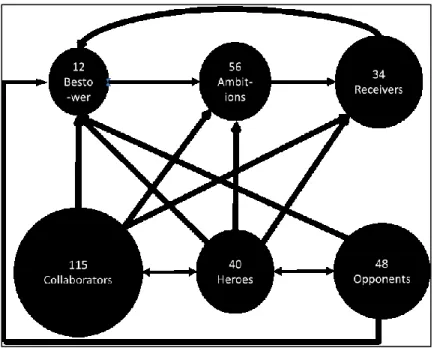

Figure 2 Desire axis – Hero and Ambitions ... 47

Figure 3 Power axis - Collaborators, Heroes, and Opponents ... 48

Figure 4 Transfer axis – Bestowers, Ambitions, and Receivers ... 49

Figure 5 Number and types of actors in presidents’ letters ... 58

Figure 6 BROACHT relationships model ... 59

Figure 7 Influencing Bestower ... 61

Figure 8 Building a new normalcy proposition in action ... 89

Figure 9 Acquiring Perceived Value (PV) through Special Olympics... 111

ix Tables

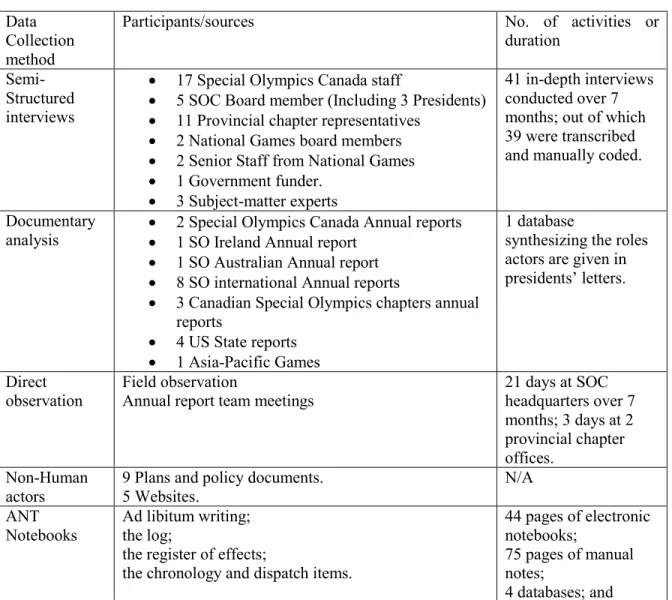

Table 1 synthesizing the data collection ... 34 Table 2 Actantial categories, roles, and examples ... 50 Table 3 Analyzed annual reports ... 53

x

Acknowledgments

We are like dwarfs on the shoulders of giants, so that we can see more than they, and things at a greater distance, not by virtue of any sharpness of sight on our part, or any physical distinction, but because we are carried high and raised up by their giant size.

Bernard of Chartres, circa 1130 AD As the metaphorical dwarf in this quote, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to those who supported and guided me throughout this amazing undertaking. Accordingly, I will begin by thanking the giants of my PhD committee for their essential involvement in this project.

My deepest gratitude goes to Dr. André Richelieu, who believed in me when others did not, who always provided quick and helpful feedback, and who generously shared his immense and impressive passion for teaching. What is more, as he expertly navigated, with a light hand on the tiller, this project through the shoals and complexities of the PhD process, I can now only hope to live up the standards set by the one, and only, “Tom Jones” of edutainment!

I would also like to specifically thank Dr. Yves Gendron for providing significant guidance in the classes you taught me, for setting me on the path of Bruno Latour et al., and for your ongoing words of encouragement. I truly hope that you will agree that this project answers your favoured question of “why does it matter”? Special thanks to Dr. Nizar Souiden for your support and guidance during each step of my work and for helping me complete this difficult endeavour. Your constructive comments and ideas were always appreciated. Additionally, I would also like to thank Dr. Frank Pons for accepting, without hesitation, to join the committee even after much of the theoretical underpinnings had already been set. You quickly grasped the nature of this research and your insights were most helpful indeed. I also respectfully acknowledge and thank Dr. Richard Giulianotti for accepting to join this project, even though having a giant from the field of sport for development and peace research on a review committee is somewhat unnerving. However, your ideas and suggestions undoubtedly make this project all the more robust and credible, and for that, I am truly grateful.

In addition, I extend my gratitude to Professors Maripier Tremblay, Sophie Veilleux, and Zahn Su, as well as Dr. Paule Duchesneau for providing significant guidance and helpful suggestions throughout this project. Moreover, I must highlight my appreciation for the pertinent (and patient!) editing and writing advice provided by Carrie-Lynn Evans who undoubtedly helped make this a more legible, robust, and convincing document. Judy-Anne Hélie and Rachel Lachance’s ongoing administrative knowledge and expertise was greatly appreciated throughout this project. Also, to Mr. Denis Paquet, who provided the spark that set me on this path by introducing me to this research field … I hope you know that this is all your fault!

I am also deeply indebted to my fellow PhD colleagues, Marie-Josée, Claire-France, Maude, Chloé, Mouna, Manel, Alain, David, Nicholas, Tegwen, Simon, and most significantly Amélie Cloutier. Thank you so much for the many opportunities to share a laugh, for reading my rough work, for enduring my presentation practices, for just being around in difficult moments, for giving me endless PowerPoint sand Endnote tips, and

xi

for all the times you helped sort-out my many confused ideas. Without your close support, this journey would have undoubtedly been far less interesting.

The uniqueness of this project required that many individuals believed in the importance of this research. I would therefore like to thank Sharon Bollenbach, the board of directors, and the whole team at Special Olympics Canada for the opportunity to carry out this work with you. You never ceased to impress with your ideas, your passion, and your dedication to your cause. I also want to underscore my appreciation for the Special Olympics Canada scholarship I received and for your ongoing support throughout this research project. I could not have found an organization with a more important or nobler social cause to work with.

In the spirit of Thucydides (410 ca BCE) who argued that “the society that separates its scholars from its warriors will have its thinking done by cowards and its fighting by fools”, this project also has a very personal side for me. In a sense, this amazing academic journey somewhat completes one specific peace-keeping mission that a much younger Lieutenant Webb undertook in July 1993. This rightly implies that I give a special recognition to all the people with intellectual disabilities that I have met during my adventures as they have taught me so much more than any of them can imagine. Collectively, they showed me the true meaning of grit and courage, and for that I am much obliged.

Finally, I would like to say thanks to Whiskey (my dog, not the drink) for taking me out for a walk every morning to help me stay sane. I also want to express my immense gratitude to my parents for the combined gifts of imagination, curiosity, determination as well as for the impressive PhD Kilt which will be a treasured artefact for years to come. A heartfelt “merci beaucoup” goes to Marie-Chantal for all the innumerable little things that helped keep this project going and especially for all the six o’clock cocktails! Lastly, I want to thank my son William for explaining what the actantial model is, for reminding me every day that anything worth doing is worth overdoing, and for giving a father so many reasons for beginning, and more importantly finishing, an unbelievable undertaking. Thank you for being the great son and young man you are.

xii Préface

L'état de publication des articles insérés (dates de soumission, d'acceptation ou de publication);

Le premier article a été soumis le 2016-04-05 à Critical Perspectives on Accounting. Cet article a reçu un avis de « réécrire et resoumettre » le 04-07-2016. Aucune modification n’a été portée à l’article présentement soumis.

Les articles deux et trois ont un format différent au niveau des « abstract » qui ont des standards de présentations différents. Cependant, ils sont formatés pour être soumis sous-peu.

Les modifications entre les articles insérés et leurs versions publiées, s'il y a lieu;

Pour assurer une harmonie au niveau de la présentation, tous les articles présentés ici utilisent le système de référence « APA », ce qui peut être différent de ce que demanderont des revues ciblées. De plus, pour assurer une plus grande harmonie à travers l’ensemble de l’œuvre, les articles présentés ici ont un paragraphe de transition au niveau de la conclusion, qui sera retiré lors de la publication.

Finalement, les articles présentés ici utilisent l’« oxford comma » pour offrir plus de clarté, mais cette ponctuation sera possiblement supprimée selon les demandes des éditeurs des revues visées.

1

1. Understanding Sport for Development Evaluation Thought and How it is Carried out ─ An Introduction

Let me win, but if I do not win, let me be brave in the attempt – Special Olympics oath

Special Olympics Founder Eunice Kennedy Shriver, 1968.

Recently, several academics have claimed that better evaluation of the growing sport for development (SFD) industry is needed (Richards at al., 2013). Such claims are arguably pertinent considering SFD’s “many conceptual and operational deficiencies, … which offer little in the way of an evidentiary base for the claim that sport has intrinsic social benefits” (Cornellissen, 2011, p. 503). Moreover, the pressure on SFD agencies to conduct more and better evaluation is augmented by funding agencies, such as government as well as sponsors, who are also clamouring for evidence of SFD’s contributions. As a case in point, in 2008, the United Nations (UN) ensconced the idea that sport could be used to contribute to achieving the millennium development goals. By mobilizing representatives from 47 nations, the UN produced a 308-page report designed to inform governments of the power of sport for development. However, the subsequent International Forum on Sport for Peace and Development that was held in May 2011 at the United Nations office in Geneva, specifically called for “the strengthening of common evaluation and monitoring tools on the impact of sport in social and economic development and for the interdisciplinary research to develop scientific evidence and good practices in these fields” (UNOSDP, 2011, p. 35). This call for better SFD evaluation was again reiterated in the UN’s office on sport for development and peace’s (UNOSDP) 2013 annual report. These respective calls invite reflection on whether the UN thinks that sport is a promising development tool, but just cannot prove it yet; or that sport is not effective, but they want/need people to think that it is? Yet, by apparently questioning their own faith in the theoretical potential of sport, the UN does contribute, however, to a healthy skepticism with regard to the potential of SFD.

In this regard, it is fascinating to note that claims that more sport for development evaluation is needed are frequently met by “pervasive undercurrents that discredit rigorous evaluation” (Richards et al., 2015, p. 3) and by a “questioning of the fundamental assumption that evaluation can be a rational and objective process” (Levermore, 2011a, p. 554). To the point where some SFD actors “believe that research and evaluation are unnecessary academic exercises that waste valuable program resources on outcomes that they postulate are impossible to measure” (Richards et al., 2013, p. 3). Indeed, calls for evaluation are being “challenged because the evaluation process can be expensive, time-consuming, technically complex, findings lag behind reality (arrive too late), go unread, don’t

2

always answer the ‘right’ question, lack analytical rigour and have access to limited availability/quality of data” (Levermore, 2011b, p. 340).

Yet, considering the complexities of the unique networks, contexts, and situations in which SFD agencies operate, would it not be logical to assume that a successful SFD agency in terms of longevity, sustainability, and growth effectively evaluates its operations in some ways? This suggests that the evaluation controversy might be, at least partially, the result of academics and the UN not quite grasping the nuances of evaluation schemes and strategies that are implemented on the ground. Therefore, the more precise matter of concern might not be whether successful SFD agencies should conduct more, or better evaluation. Rather, it might be more apropos to consider if SFD actors have developed and implemented evaluation standards and practices that are simply not yet understood. For instance, it seems likely that SFD agencies would reject a “you can’t manage what you don’t evaluate” mindset as their operations often intrinsically involve concepts that are difficult to evaluate such as inclusion or self-esteem. Thus, it is highly plausible that, in order to plan, organize, lead, and control their operations, SFD managers would elaborate evaluation thoughts, strategies, and practices which take such intangible concepts into consideration. Moreover, it is conceivable that changes in the funding environment is driving the pressure to evaluate. Hence, the so-called evaluation controversy might simply be a side effect of evaluation schemes that are different from what academic or funding agency accountants expect, or understand. Consequently, analyzing SFD evaluation thought and how it is carried out is arguably one promising approach for better understanding the SFD evaluation controversy, while concurrently contributing to the field of SFD research.

Still, there might be significant risks to future sport for development research efforts if Levermore’s (2011b) aforementioned “right” questions are the only ones being asked. For instance, one direct risk associated with only posing questions that are known to produce the answers that SFD agencies or their financiers want, is that scholars would be pressured to “get off the bench” (Zirin, 2008, p. 28) and “support this process by developing rigorous monitoring and evaluation systems” (Cardenas, 2013, p. 30). In other words, academics may be pressed into directly supporting agency evaluation efforts. What is more, as there is a “tendency for … evaluation strategies to operate with the goal of proving the success of sport-based development and intervention programs” (Hartmann & Kwauk, 2011, p. 299), it is plausible that SFD scholars may be nudged into tailoring their question and research in a way that proves that a SFD agency works as advertised. This could, for example, lead SFD agencies to only granting access to scholars who will produce the types of reports or narratives that are needed to support their funding requests with more critical academics being brushed aside or ignored. Arguably, conducting research that demonstrates the impact of SFD could

3

lead to being lauded as an SFD expert or an ally that supports the SFD movement, and such academics would effectively play a role in transforming the claim that SFD works into fact (Latour, 1987). Yet, in keeping with the sport theme of this dissertation, it appears fair to ask if this is the game that SFD academics should be playing?

Conceding that “evaluation is a critical component of an effective [SFD] program” (Blom, Judge, Whitley, Gerstein, Huffman, & Hillyer, 2015, p. 8) and that evaluation is one of the identifiable thematic areas in which SFD academics publish (Burnett, 2015), a first pertinent question may be: the evaluation of what, specifically, is being discussed here? Does the so-called “what” under discussion only refer to broad impacts of a given program or does it also include inputs, activities or even context? For instance, even if several authors have focused on the overall impact (Bean, Forneris, & Fortier, 2015; Blom et al., 2015; Bruening et al., 2015; Coakley, 2011; Richards et al., 2013) or social impact (Burnett, 2010) of SFD programs, not all published SFD research is about evaluating impact. For instance, “Boyle has developed a rubric to assess sustainability based on three evaluative levels (low, medium, high) of seven criteria: “evaluation, funding, goals, social integration, volunteers, volunteer training, and exit strategies” (Donnelly, Atkinson, Boyle, & Szto, 2011, p. 596), which could be used to evaluate a given SFD program. Reflective of Hambrick and Fredrickson’s (2001) position on the importance of evaluating strategy, certain SFD scholars have argued that there is currently a lacuna in the comprehensive evaluation of SFD (Hartmann & Kwauk, 2011; Kidd, 2011; Levermore 2011b). Hence, as “there remains a dearth of evaluation and research to understand the impact of such programs” (Bean et al., 2015, p. 28), it is the intention of this dissertation to contribute to addressing important gaps in acquired knowledge by conducting a unique critical analysis of one SFD agency’s evaluation thoughts in action.

1.1. Research Problem and Objectives

Donnelly et al. (2011) ask what are the characteristics of SFD and how might various projects be evaluated, and the aim of this dissertation is to offer answers to these questions. However, it would be over-ambitious to try and analyze, in a single dissertation, all evaluation-related concepts of even just one SFD organization, let alone all the concepts that influence the evaluation of a complex global network of SFD agencies over several decades. Such an undertaking would be all the more challenging since the more or less interconnected networks of SFD actors cannot currently highlight milestones of achievements that are measurable or that may be claimed to have been achieved by this collective as a whole. In comparison, other global organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) can claim collective achievement when a child vaccination program has been

4

completed or when they state Ebola has been defeated. What is more, being spread thinly throughout the world, the potential impact of just over 700 independent SFD agencies (Sport and Development, 2016), pales in comparison with other much larger and better coordinated multinational channels such as the World Bank (Browne, 2001). As a development entity, therefore, the “woefully underfunded, highly uncoordinated and completely unregulated” (Kidd, 2008, p. 371) SFD collective, with its highly dispersed constituency of targeted beneficiaries, will arguably influence communities in different ways. Along these lines, there is clearly not the scope here to attempt to provide an overview of the real or claimed impact of thousands of SFD projects, over many years. Indeed such matters of concern whets our curiosity for more details about the complex motivations, thoughts, and actions that influence SFD evaluation. However, a more targeted research approach is timely.

1.1.1. Research objectives and justifications.

The objective of this dissertation is to contribute to the theoretical underpinnings of the field of sport for development research by providing insight about SFD evaluation thought and how it is carried out. To this end, the primary objectives are:

a) To obtain a better understanding of SFD evaluation thought; and

b) Provide insights into how and why SFD evaluation is carried out in the field.

Secondary research objectives were derived from Weick’s (1996) recommendations that administration sciences should a) focus on relationships, but not settle for simple relationships; b) demonstrate configurations and contingencies in relationships that bring one to conceive concepts that to go “beyond concrete events” (p. 303); and c) lead to the “development of operational definitions that bridge concepts and raw experience” (p. 303). With this in mind, this project was also designed to achieve the secondary objectives of collating concepts related to evaluation management that provide insight about the broader SFD research field, and to provide operational definitions that build bridges between these concepts and the concrete relationships built by and through SFD evaluation. There are many reasons for achieving these objectives, yet the dominant justifications are: a) The lack of insight about the targeted agency as well as the athletes they serve. This justification

will be expanded in section 1.2 ;

b) The gaps in current literature described in section 1.3; and

c) The methodological groundings for this project, elaborated in section 1.4 also supports and further justify this research project. By borrowing from Latour’s (2005) actor-network theory

5

(ANT), which is a proven method for better understanding organizations, this is one of the first scholarly works that will analyze relationships between SFD evaluation thought and how it is carried out using ANT.

As the evaluation strategy in a sport for development organization is likely not designed and implemented based on a single individual’s thoughts, evaluation strategies and processes will be developed and implemented by groups of actors that are connected through relationships (Law, 1992). As their interests become aligned, the stabilized, or black-boxed (Latour, 1987), evaluation networks somehow manage to get actors to work together. Hence, in pursuance of this project’s objectives, one promising black-boxed evaluation network needed to be identified and cracked open. The characteristics of the targeted network were established based on published literature and included the following requirements: a) the actor-network is related to a sport for development organization; b) the organization conducts evaluations of their operations; c) they provide accounts of these operations; d) they operate in a geographic area that is safe enough to conduct research; and e) “offers scope not only for the collection of rich data, but also flexibility about a research topic” (Irvine & Gaffikin, 2006, p. 121). As a result, one very unique organization was chosen for this study.

6 1.2. Introducing Special Olympics Canada

Following contacts made between February and June 2015 by phone, letter, or email to an initial round of 12 SFD organizations that met these characteristics, Special Olympics Canada (SOC) demonstrated the most interest in participating in the project. Having worked with this organization in the past, the access was facilitated by a known sponsor (Patton, 2002) and this previous experience provided valuable contextual knowledge about SOC’s operations, organizational behaviour, and more importantly, the athletes they work with. To wit, SOC is dedicated to enriching the lives of Canadians with intellectual disabilities (ID) through sport. With over 40 000 registered athletes, SOC not only met this project's research parameters, but is also one of the largest amateur sport organizations in Canada. This organization, which has been in operation since 1969, contributes to more inclusive communities and fosters “a capacity to work in a cooperative manner” (Cardenas, 2013, p. 26), and are, in their own words,

…a force that brings people together and allows them to connect on an entirely new level. People from all walks of life – families, local leaders, businesses, law enforcement, celebrities, government officials, and others – work together to make the world a better place; one which is more respectful, accepting, and tolerant (SOC, 2016a).

The nature of the disability, in this case intellectual disability, is one of this movement’s distinguishing features and differentiates it from other social sport brands such as Paralympics which focuses on physical disabilities. As conceptual clarity is important, this study will adopt the United Nations perspective on disability, which contends that “persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” (Beacom & Golder, 2015, p. 2). More specifically, intellectual disability includes Down syndrome, autism, Asperger’s syndrome, and having an Intellectual Quotient (IQ) of less than 70. Generally, IDs implies

a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn and apply new skills (impaired intelligence). This results in a reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning), and begins before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development (WHO, 2016).

Special Olympics Canada is a registered charity which receives a significant portion of their revenues from Sport Canada, corporate sponsors such as Sobeys and Staples, as well as private donors. Through a federated model of 12 independent provincial and territorial chapters, SOC provides what one interview participant describes as “cradle to grave” participative and competitive sport for development opportunities to athletes with IDs.

7

The corporate governance and strategic affairs are overseen by a volunteer board of directors, which at the moment of this study was composed of four women and fourteen men. The day-to-day operations are managed by a 16-person team located in Toronto, Canada. According to their current five-year strategic plan, their operations could be broken down into sporting, health, community, and sustainability priorities. Thus, as an organization, SOC reflects the variety and fog associated with the limits and boundaries observed in other Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO’s) (Davison, 2007; Gray, Bebbington, & Collinson, 2006; O’Dwyer, 2005). Organized as a charity, yet often operating like a business, it relies on, but also provides direction and support to, provincial chapters. These independently incorporated not-for-profit provincial chapters are the agencies that provide most of the direct services to their targeted athletes.

In their 2015 annual report, Special Olympics Canada reported revenue of $9.5 million Cnd obtained through grants, fund-raising events, sponsorships, and foundations that sustain wide-ranging sport, health, business development, and social elements of their operations. This multiplicity of funding sources obviously has an impact on their evaluation and accountability, which is a trait observed in many NGO’s (Davison, 2007; Hulme & Edwards, 1997). SOC’s operations are accounted for, amongst other means, by an annual report which is a document that reflects the rich and complex mission that SOC strives to accomplish. The information and facts that SOC wishes to communicate is presented in a colour document, ranging from 49 to 60 pages depending on the year, and is available in both paper and electronic versions as well as in English and French, which are Canada’s official languages. SOC’s annual report includes regulatory accounts, a CEO’s and chairperson’s letter, highlights from chapters, and is filled with vivid pictures and stories about SO athletes and volunteers. Obviously, much work is needed to produce these sophisticated assets; to describe, in great detail, the activities of the actor-network that builds it will be a challenging, yet promising, endeavour.

What is more, the annual report actor-network does not just produce this accounting artifact, but also communicates it with a broad audience. Specifically, as there are no shareholders or voting members in this organization, the annual report is shared with board members, major funding partners, potential partners, and the provincial chapters that request copies. As such, the actors that will be followed through this project will consist mostly of board members, directors, staff, and volunteers who are involved in not only crafting SOC’s annual reports, but also participate in sharing and communicating the finished asset. What is particularity fascinating is that crafting annual reports is a relatively new activity for SOC, with only three annual reports (2013, 2014, 2015) having been produced so far. This offers opportunities to witness actor-network creation in action as the who, what, and why behind this initiative, as well as all the related strategies, processes, and controversies

8

are still emerging and evolving. Thus, it appears highly plausible that the manipulation, negotiating, seducing, nudging, nagging, or coercing required to get actors involved in the annual report network are all ongoing. Furthermore, as this evaluation and accounting process is still in its infancy, the related paper and electronic media, such funding applications, evaluation reports and training material, websites, as well as videos will all have been produced recently which will increase and facilitate data traceability and collection.

Beyond conducting much of their operations at the grassroots level through their affiliated chapters, SOC is also an important player in a much broader institution. Special Olympics International (SOI) is a multinational sport provider that operates in 168 countries and is one of the largest amateur sports organizations in the world. Founded in 1968 by Eunice Kennedy Shriver, this movement has its roots in the ground-breaking work of University of Toronto’s Dr. Frank Hayden:

It challenged the prevailing mindset of the day – one that claimed that it was the disability itself that prevented them from fully participating in play and recreation. Through rigorous scientific method, Dr. Hayden proved that it was simply the lack of opportunity to participate that caused their fitness levels to suffer. Given the opportunity, people with an intellectual disability could acquire the necessary skills to participate in sport, and become physically fit. Sport could have a transformative effect on the lives of those with an intellectual disability. (SOCb, 2016)

The thought that it was the disability, and not the lack of participation, that was the cause of a lack of physical ability may have been reflective of the dominant ideology (Bourdieu & Boltanski, 2008) and grand narrative (Boje, 2001) that was prevalent in that historical period (Gendron & Breton, 2013). Such historical narratives were even powerful enough to lead to secluding, hiding, or even sterilizing individuals with an intellectual disability (Grekul, 2011). The overall situation has thankfully improved for many individuals with an ID, yet long-standing narratives arguably still affect these individuals today. As a case in point, over 75% of adults with an ID are currently unemployed in Canada (Bizier, Fawcett, Gilbert, & Marshall, 2015). Thus, as the State gradually decreases its involvement in social causes (Harvey, 2005), SOC operations could be placed against a backdrop of neoliberal agendas that promotes reducing the role of the State in favour of greater freedom for corporations to act as saviours of the world. One result of this trend is that, in many contexts, sport is now a luxury that many children (and even adults) cannot afford (Armstrong, 2004).

Composing with this trend, Special Olympics has enthusiastically assumed, since the late 1960s, the mantle of creating what politicians and governments were unable or unwilling to do, that is to enrich the lives of people with an intellectual disability, through sport, and to contribute to tolerant and inclusive communities. This transfer of burden is similar to other situations in which governments

9

transfer responsibility for the delivery of public services towards corporations, NGOs, church groups, or even hockey stars (Basu, 2015). Moreover, neoliberalism is argued to be a concept that emphasizes “evidence as the golden goose of validity” (Hall, Massey, & Rustin, 2013, p. 2). Thus, it appears highly plausible that neoliberalism’s penchant for all things measurable could be a meta-concept that may arguably influence Special Olympics actors. In other words, neoliberalism may influence or taint evaluation thought and its related processes.

Another justification for focusing on Special Olympics Canada is that many sport for development agencies currently prefer addressing so-called “third world”, rather than domestic, issues (Choudry, 2007). As a case in point, the vast majority of SFD research has so far “focused on programs taking place in the ‘Third World’ (or what we refer to throughout this paper as the Global South) rather than illuminating the domestic terrain of similar initiatives currently taking place in Global North Countries such as Canada” (Hayhurst, Giles, Radforth, & The Vancouver Aboriginal Friendship Centre Society, 2015, p. 2). Accordingly, as there are undeniable development issues throughout the Global North, this project will concurrently address two important gaps in current research; the lack of insight about the evaluation of SFD for people with an ID as well as the lack of insight about SFD in Canada.

10 1.3. Justifications From Literature

We further call for the strengthening of common evaluation and monitoring tools on the impact of sport in social and economic development and for more interdisciplinary research to develop scientific evidence and good practices in these fields.

United Nations Office on Sport for Development and Peace – 2013 annual report. The UN’s call for “the strengthening of common evaluation … tools and for … more interdisciplinary research to develop scientific evidence … in these fields (UNOSDP, 2011, p. 35) could be translated as a call for academics to establish and test the fact that SFD works. Taking stock of the state of the academic art appears as a pertinent departure line for exploring concepts related to such a call. Moreover, analyzing SFD literature provides a better idea of the challenges relating to the transformation of claims that sport influences development into a fact. Thus, this section was written with the intention of a) highlighting and considering concepts related to evaluation thought and how it is carried out; b) identifying gaps and lacunas in our current understanding of SFD evaluation; c) providing further justifications for this research project; d) establishing conceptual boundaries to the overall research project (Peters, Godfrey, McInerney, Soares, Hanan, & Parker, 2015): and e) expanding the handful of literature reviews of SFD research (Jones, Edwards, Bocarro, Bunds, & Smith, 2015; Kidd, 2007; Langer, 2015; Schulenkorf, Sherry, & Rowe, 2016). This is all the more pertinent considering that,

a review of prior, relevant literature is an essential feature of any academic project. An effective review creates a firm foundation for advancing knowledge. It facilitates theory development, closes areas where a plethora of research exists, and uncovers areas where research is needed (Webster & Watson, 2002, p. xiii).

Indeed, a literature review may uncover areas relating to evaluation thought and how it is carried out where more research is needed. Thus, in the spirit of Lewin’s (1945) claim that “nothing is as practical as a good theory” (p. 129), collating existing theory is a practical approach for further contributing to this under-theorized research field (Schnitzer, Stephenson, Zanotti, & Stivachtis, 2013).

The data for this review was first obtained by using “sport” and “development” as a key-word in the ABI/Inform and web of science databases. Subsequently, each article was read, analyzed, and references that were not previously identified through the data-base search were extracted and similarly examined. Through this two-step process, 176 peer reviewed articles were analyzed for concepts related to evaluation thought and how it is carried out. Successively, all obtained works were then collated using “evaluation”, “proof” and “evidence” as initial key-words and clusters for analyzing the content.

11

As this section will demonstrate, much of the SFD literature focuses on broad questions related to evidencing SFD impact. However, narrowing the focus from broad evaluation concepts to more pointed questions relating to SFD evaluation thought will conceivably provide insight about basic building blocks of the SFD movement. For instance, by focusing on the evaluation of broad impacts of SFD, academic literature has hitherto somewhat neglected considering that all stages of SFD operations, such as inputs and activities, contribute to the overall success or failure of a given scheme, and as such, should arguably be evaluated. In essence, the collated academic papers provide findings about three trends related to SFD evaluation thought: a) Confirming the potential of SFD (see section 1.3.1.1.); b) Critiquing SFD claims (see section 1.3.1.2.); and/or c) Contributing to SFD facts by using previous claims (see section 1.3.1.3.). Synthesizing research trends will subsequently lead to a discussion about four justifications for this study that are drawn from existing literature: a) The need to better understand SFD facts; b) The need to better understand the why behind the calls for more evaluation; c) The current lack of consensus about what to evaluate; and d) Under-theorization of SFD evaluation thought.

Yet, before unpacking the literature, it is pertinent to mention that each of the three papers that forms the core of this dissertation has its own literature review sections. It was therefore decided to keep this literature review short in order to reduce, without completely eliminating, redundancy. This is why the literature review is presented as a section of the introduction, rather than as a lengthier chapter that might be commonly found in a classical dissertation. However, this section is still sufficiently robust to credibly argue that even if it is pertinent to consider and evaluate the ultimate impact of a SFD program, a better understanding of evaluation thought and its related management choices, decisions, investments, and actions which all contribute to an organization's impact, is also needed.

1.3.1. Findings: Unpacking evaluation thought in SFD research.

Levermore (2008) claims that the impressive list of sport for development initiatives really took off as a result of criticism of more traditional development tools such as trade and investment. The 483.48% increase (Sport and Development, 2016) in the number of organizations that claim to use sports for development since Levermore’s aforesaid observation has attracted rising academic interest in this emerging research field. So far, published SFD research has shed light upon relationships between sport and individual or community development (Del Felice & Wisler, 2007; Hassan & Telford, 2013; Hasselgård, 2015; Schrag, 2012; Smith, Cahn, & Ford, 2010; Sugden, 2008), gender equality (Beutler, 2008; Coakley, 2011; Donnelly et al., 2011; Dyck, 2011), millennium development goals (Khan, 2013; Lyras, 2007; Schnitzer et al., 2013), health promotion (Beutler, 2008; Calloway,

12

2004; Cornelissen, 2011; Hasselgård, 2015; Levermore, 2008) and peace (Beutler, 2008; Blom et al., 2015; Cardenas, 2103; Crowther, 1999; Darnell, 2010; Darnell & Hayhurst, 2011; Giulianotti, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c; Levermore, 2008; Peacock, 2011; Sugden, 2008). However, in comparison with the number of papers that have focused on the contributions of sport, a handful of studies have also critiqued or questioned claims about the potential of SFD. Nevertheless, constructive criticism has pertinently generated valid calls for more research about SFD evaluation.

As a case in point, even if sport may somehow have an ability to break down barriers, transcend cultural differences, and unite (Darnell, 2007), it is imperative to remember that sport can also be highly divisive, often discriminates against women and minorities, and is rife with racism as well as homophobia (Kidd, 2007). Thus, overly optimistic attitudes and claims about the potential of SFD, fuelled by taken for granted facts about the power of sport such as that “Sport has become a world language, a common denominator that breaks down all the walls, all the barriers” (the UN’s Secretary General, in Maguire, 2012, p. 5) all contribute to making researching this field all the more important. Relatedly, a better understanding of current trends in SFD research may produce effective contributions to acquired knowledge.

1.3.1.1. First trend in SFD literature: Confirming the potential of SFD.

Numerous academic narratives could be described as expert discourse that supports claims about the potential of sport as a development tool. For instance, Bean et al.’s (2015) evaluation of a SFD program designed to help female youth increase their physical activity and develop life skills concludes that the program “succeeds in facilitating positive outcomes for youth” (p. 36). Similarly, much of the literature provides positive perspectives on SFD outcomes by describing SFD’s constructive contributions with likewise broad and positive, yet difficult to evaluate, concepts. An example of this broad/positive perspective on impacts is extracted from Blom et al.’s (2015) analysis of Jordanian coaching workshops, which led them to conclude that

utilizing sport as a tool to promote empathy, leadership, communication, peace-building skills and collaboration among diverse populations may provide young athletes with the skill-sets needed to become productive and well-rounded adults who are better prepared to contribute to society (p. 10).

How they evaluate these broad/positive impacts is not discussed; nor is the role sport played in acquiring them; or if the broad/positive impacts were obtained by all participants, all the time and at the same level. Yet, even if such reported findings buttresses SFD claims, these last authors do recognize that such SFD initiatives may have limited impact on initiating social change and as such may actually contribute to segregation and fear. Other examples of broad/positive perspectives on

13

SFD impact include Cardenas’ (2013) affirmation that “sport programs had an impact on the self-esteem and perceived self-efficacy of participants” (p. 26); and that “SFD has been shown to facilitate positive outcomes such as social capital development through expanding networks and community building” (Bruening et al., 2015, p. 69). Again, the precise relationship between sport and these impacts are not established.

Conversely, some authors adopt a narrow/positive perspective and focus on more pointed elements of SFD’s potential. As a case in point, Armstrong (2004) argues that the “best that football can claim to be able to offer is an avenue to better health, lessons on morality, the sacrifices teamwork requires, the need for charity and selflessness, and generally offer itself as a workable metaphor” (p. 495), which, in some circumstances, may be far better than nothing. What is more, other narrow/positive impacts include sport that serves to protect children from adults who have dishonourable intentions (Armstrong, 2004), or becomes a surrogate family (Armstrong, 2002).

If the premise that SFD does indeed contribute to generating positive outcomes is accepted, other indirect contributions could also be considered. For instance, Sugden’s (2010) “ripple effect model … illustrates the circumstances under which sport can make a difference in the promotion of social justice and human rights in deeply divided societies” (p. 259). Moreover, frequently repeated positive perspectives on SFD outcomes is apparent throughout the analyzed papers. To the point where it is not only the quality, but also the quantity of narratives that conceivably contributes to SFD fact-building. Similarly, as Latour (1987) affirms that experts, allies and literature can all contribute to transforming claims into fact, the growing volume of published research could also be contributing to SFD fact-building purposes. Put differently, Sugden’s (2010) ripple effect metaphor may not only be pertinent for reflecting on the influence SFD schemes may have, over time, on development of society, but may also be representative of the influence that generally positive published research may have of the long-term transformation of SFD claims into facts.

1.3.1.2. Second trend in SFD literature: Critiquing SFD claims.

In a pathfinder role, Armstrong (2002) nuances the dominant broad/positive perspective on SFD impact by arguing that

the outcomes of the various projects are not obvious. There are possibly two reasons for this. The first is that many projects are recent in their implementation and, in the arena of post-war reconstruction, are difficult to evaluate. The other is that some projects seem to be celebrity-led with little evidence of long-term planning, but the organizers seem happy to promulgate clichés via glossy brochures and photo opportunities (p. 479).

14

For all the taken for granted powers of sport, analyzing SFD literature reveals that several scholars offer, in contrast to the generally positive narratives presented in the previous section, a more critical review of this field (Coalter, 2007; Darnell, 2010; Kay, 2009). For instance, Svensson and Hambrick (2016) have highlighted the growing body of research, such as Coakley (2011), Coalter (2010), and Darnell (2007, 2012), that critiques the idealistic beliefs that undergird many SFD claims and programs. Critical scholars argue for more realistic expectations with regards to what these programs can accomplish. Indeed, considering the complexity of environmental factors such as operating in nihilistic societies (Armstrong, 2002), even well-structured SFD programs may not result in positive outcomes for all participants, all the time (Coalter, 2010). Such considerations invite scholars to not focus exclusively on potential, but to also remain cognizant about SFD’s theoretical limits whilst they advance in the largely uncharted SFD waters.

One such conceptual sandbar that SFD scholars may need to navigate is to consider if the studied agency may be trying to integrate the athletes into society rather of instead trying to change society. This state of affairs is reflected in the numerous movies, documentaries as well as abundant electronic and print media that tell the stories of the few such as Luis Suarez (Khan, 2012) or Michel Oher (Lewis, 2007) who have managed to rise above poverty and hardship through sport. Helping individuals rise above the odds is not essentially problematic in itself. However, it may be more significant for sport to help change the odds for the many, instead of simply helping the exceptional few. Hartmann and Kwauk (2011) directly address this concept by explaining that,

the mobilization of sport-for-development in its current formation is explicitly not designed to bring about social changes to inequalities, but rather to ‘… re socialize and recalibrate individual youth and young people …’ into contemporary social and economic norms and structures in order that these relations be maintained and their associated privileges preserved (p. 291).

Hartmann and Kwauk are effectively raising the important question of development for whom? The individual participants, or contemporary society and corporations which largely follows dominant neoliberal doctrines? This conceptual position re-affirms the importance of recognizing the long-standing traditions of using sport for political or social purposes.

Similarly, Darnell and Hayhurst (2011) argue that sport carries much “historical and cultural baggage especially from its hegemonic core” (p. 185). Whereas, Blom et al. (2015) posit that “Two of the most dangerous and prevalent criticisms of the SFD field are the imposition of Western ideals or neocolonialism and the absence of community voices” (p. 3). These positions are supported by Lindsey and Banda (2011) who explain that one problem at the core of many SFD operations linked

15

to neoliberalism is the bypassing of local governments by SFD agencies. This is important since such organizational behaviour may reinforce the perception that many governments of developing nations are either corrupt, failing or both (Lindsey & Banda, 2004). Moreover, the actions of international development agencies may also contribute to the construction of concerns about economic globalization as overwhelmingly being a so-called “Third World” issue which largely overlooks domestic development issues in the donor countries themselves (Hayhurst et al., 2015).

Building on the second and more critical research trend, one promising lens through which to better understand SFD evaluation thought is related to the management of evaluation and its relationships with SFD funding. As a case in point, Burnett (2015) argues that donors demand “proof” of the success over society’s problems have been achieved through the focused, yet often limited, programs they support. Clearly, the needed to provide requested proof may become a major management issue for cash-strapped SFD agencies. However, Coalter (2013) is particularly vocal about the uncritical stance that practitioners and funding agencies adopt with regard to assumed impacts, and insists on exploring sport for development without illusions, but without becoming disillusioned. In this regard, Coalter refers to the “pessimism of the intellect” and “optimism of the will” as opposing forces that describe SFD (Coalter, 2013, p. 3). He also cautions against over-simplified versions of “the nature of relationships between possible project impacts and broader individual and social outcomes” without clear evidence of cause–effect (Coalter, 2013, p. 15). One potential risk associated with a lack of critical reflection on evaluation management, would be the decision of choosing research and evaluation questions that are manageable and that are likely to provide a proof of effect for donors to justify their investments. This particular gap in knowledge will contribute to the fourth literature based justification for this research which will be presented in sections 1.3.2.4.

1.3.1.3. Third trend in SFD literature: Contributing to SFD facts by using previous claims. As the volume of SFD related papers increases over the years, another fascinating academic trend emerges: by using SFD knowledge claims by themselves, scholars wittingly or not, contribute to transforming these claims into fact (Latour, 1987). Put differently, a claim that is reused may eventually become a fact devoid of traces of fabrication and of interests. Contrariwise, a claim that is ignored will not become established as a fact and will eventually be forgotten. What is important about this process, for the purposes of the study of evaluation thought and how it is carried out, is to remain cognizant of which claims are repeated and which are ignored. For instance, by restating UN or UNESCO claims that more evaluation is needed, scholars contribute to transforming the claim that

16

more SFD evidence is needed into a fact (Brittain & Wolf, 2015; Draper & Coalter, 2016; Levermore, 2008; Lyras, 2007).

Obviously, there is insufficient scope in this project to collate all fact-building trends in SFD literature, but this literature review demonstrates broad academic support for the claim that more evaluation is needed. While sometimes apparently neglecting why the claims that SFD needs more evaluation are being made, many scholars reinforce the idea that more evaluation is needed by referring to this phenomenon themselves. Examples of this include “…evaluation is a critical component of an effective SFD program for the purposes of accountability, participant learning, program improvement, and program funding” (Blom et al., 2015, p. 9); and that it is “imperative to develop a better understanding of appropriate structures and processes needed for implementing sustainable SFD programs” (Svensson & Hambrick, 2016, p. 2). Indeed, many SFD agencies are thought to have insufficient capacity to meet the funder’s evaluation requirements.

However, ongoing calls for more evaluation may have had some unexpected results. For instance, Blom et al. (2015) argue that “with this increase in exposure, researchers began to challenge the frequent and unsubstantiated claims about the positive outcomes from these programs, calling for a more systematic implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of SFD programs (e.g., Coalter, 2007, 2010; Darnell, 2010; Sugden, 2009)” (p. 2). Such arguments run counter to the highly positive and enthusiastic claims from practitioners and proponents, and do raise certain questions about the veracity of SFD claims. Overall, such questioning may be beneficial for academia as it invites healthy debates about the potential and limits of SFD. Relatedly, the volume of ongoing discussion about SFD evaluation has even inspired Adams and Harris (2014) to analyze the impact of a so-called lack of evidence discourse. These authors suggest that, even if funding agencies and academics currently dominate evaluation approaches, “the dominance of these vested interest groups does not represent a structural and hierarchal manifestation of power” (Adams & Harris, 2014, p. 147). In other words, the narrow and constraining scientific approaches proposed to evaluate SFD initiative can be resisted by SFD agencies and that their counter-discourse provides alternatives to mainstream scientific approaches towards evidence. Nevertheless, left unresolved, the contrast between SFD proponents and skeptics, could arguably put sustainable SFD funding at risk by creating confusion in the minds of potential funding partners. Yet, critically analyzing the claims about the potential and limits of SFD may contribute to constructing more robust and practical theory.

1.3.2. Discussion: Unearthing concepts that justify this study.

Coalter (2010) sums up the situation by establishing that “ Perhaps it is these failures – overinflated and imprecise claims, lack of systematic monitoring and evaluation, lack of robust evidence of poorly

17

defined (but always ambitious) outcomes – that partially explain the relative isolation from mainstream development efforts” (p. 308). What is more, Darnell (2014) pointedly reflects upon why

few, if any, questions are asked about the structural and cultural underpinnings … of the extent to which global sporting forms thrive within the same relations of economic exploitation that sustain inequalities and that have implications for global health – one effect is to make the charity of Empire – the overflow of its wealth – into a form of benevolence, rather than a result of global capitalism’s economic surplus (p. 9).

A lack of robust evidence, the charity of Empire and the benevolent use of capitalism’s overflow of wealth, may, at first glance, appear as bleak conceptual backdrops for any study of SFD evaluation thought. Indeed, the breadth and depth of such concepts make them unwieldy, and such an endeavour would be beyond the scope of this project. Yet, beyond identifying the lack of consensus on the potential and limits of SFD, collating SFD literature provides at least four justifications for this overall research project.

1.3.2.1. First justification: The need to better understand sport for development facts. A first practical justification for providing insight about SFD evaluation thought and how it is carried out is related to the practice of underpinning SFD facts with knowledge claims, such as article 24 of the Universal Declaration of Human rights, which states that: “everyone has the right to rest and leisure” (Armstrong, 2004, p. 474), or that “The goal of Olympism is to place sport at the service of the harmonious development of humankind, with a view to promoting a peaceful society concerned with the preservation of human dignity” (International Olympic Committee, 2015). Over time, even if knowledge claims about the potential of sport have become common place and are often taken for granted, such rhetoric is scarcely evaluable. However, the limited evaluability of such claims is important since a skeptic may sometimes need to challenge SFD facts in order to make a point. To this end, a scholar who needs to question SFD claims may first have to understand taken for granted facts and theoretical foundations. It is therefore plausible that in some case, a scholar might need to challenge the Olympic Charter in order to present credible and convincing arguments. Yet, creating a breach in SFD theories and literature, such as the Olympic charter that are accepted as gospel by SFD proponents, will not be straightforward task.

Remaining cognizant of SFD fact-building may also be important when attempting to better understand SFD evaluation thought of practitioners who unquestionably accept the claim that sport is an effective development tool. To the point where Adams (2014) argues that “it is a telling point … that the intellectual development of sport for development may not be welcomed by those who occupy the evangelical mythopoeic world and who are proactive in establishing current boundaries” (p. 229). Additionally, this culture of blindly accepting SFD facts is thought to be so widespread that

18

Coalter (2010) claims that it has resulted in a state of incestuous amplification, which is defined as “a condition in warfare where one only listens to those who are already in lock-step agreement, reinforcing set beliefs and creating a situation ripe for miscalculation” (p. 295). Hence, better understanding facts that contribute to SFD evaluation thought, both at a practical as well as theoretical level, may arguably be a pertinent form of scholarly risk management, as it may help avoid costly miscalculations while designing, funding or carrying out SFD research projects.

Indeed, setting conceptual boundaries is important in order to conduct feasible research projects. However, another related risk is linked to gaining access to cash strapped SFD agencies, who may already have their doubts about evaluation, may become increasingly hesitant into granting access to their operations for academic research purposes. Indeed, collated from the reviewed literature, there appears a persistent trend of SFD actors who question the value of evaluation as wastes “valuable program resources on outcomes that they postulate are impossible to measure” (Richards et al., 2013, p. 2). Thus, understanding SFD facts as well as where the calls for more evaluation come from, and what may realistically be achieved through evaluation, may all be vital elements for gaining trust, and then access, to SFD agencies for research purposes.

1.3.2.2. Second justification: The need to better understand the why behind the calls for more evaluation.

The sports evangelist culture (Coalter, 2010) may indeed limit interaction between practitioners and scholars as the converted may be hesitant to have lengthy discussion with skeptics or academics who question their beliefs. However, the analysis of published literature also demonstrates gaps in our understanding of the why behind the calls for more evaluation. For instance, Beutler (2008) argues that there is “insufficient monitoring and evaluation to gauge the effectiveness of programs” (p. 367), but does not establish why this is. Furthermore, this perceived lack of evaluation may have grown from both domestic and international development agencies who face the increasing demand to create performance indicators that will provide evidence of the impact of programs (Beacom, 2008). Alternatively, why these calls are being made have emerged from the blurring of the roles between not-for-profit organizations and governments that act like business and businesses that act like charities or governments (Davison, 2007). Indeed, this resistance to evaluate in the way scholars and funding agencies would like them to, may be exacerbated by an industry largely structured by agencies that are accustomed to operating independently from local and national governments and “completely disregard (in this writer’s view) of the overarching need to restore and strengthen state programs of health and education” (Kidd, 2008, p. 376). Not fully considering the transnational complexities is a significant gap in the existing literature as there has been limited “sustained,