Effet du choix alimentaire sur le comportement et

les traits d’histoire de vie du gastéropode herbivore

Littorina saxatilis

Mémoire

Anis Marzouk

Maîtrise en biologie

Maître ès sciences (M. Sc.)

Québec, Canada

© Anis Marzouk, 2015

Résumé

Le régime alimentaire est influencé par la disponibilité des ressources et les préférences des consommateurs. Dans l'estuaire Saint-Laurent, l'escargot Littorina saxatilis se nourrit de deux types d'algues: diatomées et algues vertes. Dans les expériences de laboratoire, les escargots préfère fortement les diatomées, mais lorsque les attributs structurels des algues sont enlevés, cette préférence a diminué, ce qui suggère que certaines caractéristiques alimentaires (ex. l'ingestion) affectent ces préférences. La densité des escargots sur terrain est plus élevée sur les diatomées. Les expériences sur le terrain et au laboratoire ont montré que le régime alimentaire a un effet sur les traits d'histoire de vie des escargots avec les diatomées offertes dans un régime monospécifique ou mixte qui a amélioré la croissance des escargots, mais pas la fécondité. Cette étude montre que cet herbivore a des préférences alimentaires et que le régime alimentaire préféré peut améliorer certaines caractéristiques de leurs traits de vie.

Abstract

Diet is influenced by both food availability and the feeding preferences of consumers. In St. Lawrence maritime estuary, the herbivorous intertidal snail Littorina

saxatilis feeds on two different functional groups of algae: chain-forming diatoms and

filamentous green algae. In laboratory experiments, it strongly preferred diatoms, but when structural attributes of the algae were removed, this preference was weaker, suggesting that some aspect of feeding (e.g., ingestion) influences preferences. Densities of snails in the field were much higher on diatom-dominated habitats, consistent with preferences observed in the laboratory. Experiments in the field and laboratory found that diet also affected life history traits of snails with diatoms provided in monospecific or mixed diets increasing juvenile growth rates, but not fecundity. This study shows that this herbivore has dietary preferences and that a diet of its preferred food can positively affect certain life history characteristics.

Table des matières

Résumé ... iii

Abstract ... v

Table des matières ... vii

Liste des tableaux ... ix

Liste des tableaux en annexes ... xi

Liste des figures ... xiii

Remerciements ... xvii

Avant - Propos ... xix

Introduction générale ... 1

Chapitre 1. ... 11

Résumé ... 12

Abstract ... 13

Introduction ... 14

Materials and methods ... 15

Results ... 18 Discussion ... 21 Acknowledgments ... 25 Chapitre 2. ... 27 Résumé ... 28 Abstract ... 29 Introduction ... 30

Materials and methods ... 32

Results ... 35 Discussion ... 37 Acknowledgments ... 41 Conclusion générale ... 43 Bibliographie ... 51 Annexes ... 65

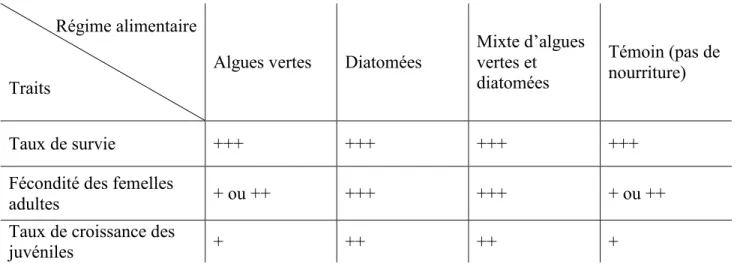

Liste des tableaux

Tableau 1 : Variation de traits d’histoire de vie chez littorina saxatilis en fonction du

régime alimentaire. Ces symboles « +++ », « ++ » et « + » représentent l’importance de la réponse. ... 46

Tableau 2 : Variation de traits d’histoire de vie chez Littorina saxatilis en fonction de la

hauteur de la zone intertidale. Ces symbloes « +++ », « ++ » et « - » représentent l’importance de la réponse. ... 48

Liste des tableaux en annexes

Tableau A1 : Résultats d’une ANOVA sur les préférences alimentaires au laboratoire

(Facteurs fixes : Zone [basse, haute], Diète = régime alimentaire [algue verte, diatomée, mélange, témoin], Mois [juin, juillet, août], Forme [entière, broyée]). * indique une signification au seuil α = 0.05. ... 65

Tableau A2 : Résultats d’une ANOVA sur la répartition sur le terrain (Facteurs fixes :

Zone [basse, haute], Habitat [tapis d’algues vertes, tapis de diatomées, tapis mixte, témoin = roche nue], Mois [juin, juillet, août], facteur aléatoire : Sexe [mâle, femelle]), * indique une signification au seuil α = 0.05. ... 66

Tableau A3 : Résultats d’une ANOVA sur la reproduction sur le terrain (Facteurs fixes :

Zone [basse, haute], Diète = régime alimentaire [algues vertes entières, diatomées entières, mélange entier, algues vertes broyées, diatomées broyées, mélange broyé, témoin]), * indique une signification au seuil α = 0.05. ... 67

Tableau A4 : Résultats d’une ANOVA sur la reproduction au laboratoire (Facteurs fixes :

Zone [basse, haute], Diète = régime alimentaire [algues vertes entières, diatomées entières, mélange entier, algues vertes broyées, diatomées broyées, mélange broyé, témoin]), * indique une signification au seuil α = 0.05. ... 67

Tableau A5 : Résultats d’une ANOVA sur la croissance sur terrain (Facteurs fixes : Zone

[basse, haute], Diète = régime alimentaire [algues vertes entières, diatomées entières, mélange entier, algues vertes broyées, diatomées broyées, mélange broyé, témoin]), * indique une signification au seuil α = 0.05. ... 68

Tableau A6 : Résultats d’une ANOVA sur la croissance au laboratoire (Facteurs fixes :

Zone [basse, haute], Diète = régime alimentaire [algues vertes entières, diatomées entières, mélange entier, algues vertes broyées, diatomées broyées, mélange broyé, témoin]), * indique une signification au seuil α = 0.05. ... 68

Liste des figures

Chapitre 1

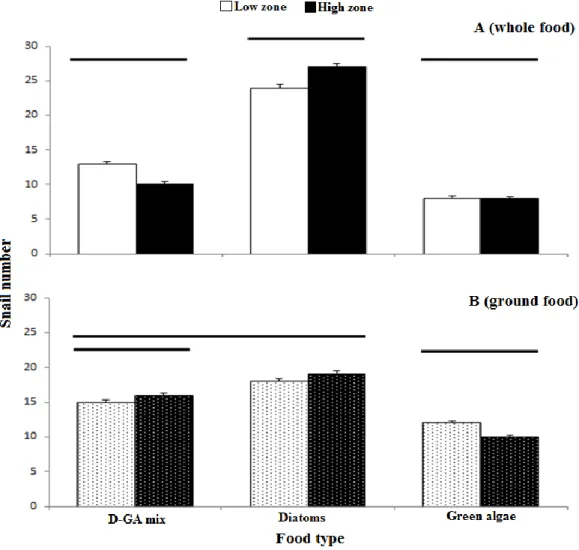

Figure 1.1. Multi-choice laboratory feeding experiments with Littorina saxatilis on

different algal diets; (A) Multi-choice whole-food comparisons and (B) Multi-choice ground-food comparisons, offer to L. saxatilis individuals harvested from the the high (black bars) and low tidal zones (empty bars). ”D-GA mix” represents a mixture of diatoms and green algae. Bars are averages for high and low zones over the three months of the study with standard errors (n = 3months). Horizontal lines group treatments that are not significantly different from each other. See Tableau3 for statistical details... 19

Figure 1.2. Mean density of Littorina saxatilis (bars represent standard errors) during the

summer (June-July-August) in the high and low tidal shore zones at five study sites near Pointe-Mitis, Québec, Canada. “D-GA” represents mixed diatom-green algal mats, “D” diatom mats, “GA” green algal mats, and “C” bare rock surfaces. Bars are averages for six quadrats in each of five zones (n=30). Horizontal lines group non-significant treatments. See Tableau 4 for statistical details. ... 20

Chapitre 2

Figure 2.1. Mean fecundity (bars represent standard errors) in laboratory (A; C) and field

(B; D) experiments for Littorina saxatilis individuals from high (filled bars) and low tidal zones (open bars) fed on whole food (A; B) and ground food (C; D). The same treatment was used as the control for both whole and ground food comparisons, and the data are repeated for clarity in both upper and lower panels. Bars with the same letter are not statistically different from each other (LSD test, P > 0.05). See Tableaux 5 and 6. ... 36

Figure 2.2. Mean Growth rate ratio (bars represent standard errors) under laboratory (A; C)

and field (B; D) experiments with different food conditions for Littorina saxatilis snails from high and low tidal zone fed on whole food (A; B) and ground food (C; D). Bars with the same letter are not statistically different from each other (LSD test, P > 0.05). See Tableaux 7 and 8 for statistical details. ... 37

Remerciements

Je tiens, tout d’abord, à remercier mon directeur de recherche Ladd Johnson. Ladd m’a accueilli chaleureusement au sein de son laboratoire, il a beaucoup aidé à mon intégration dans l’équipe et il était très patient lors de la réalisation de mon projet. Ladd est amoureux de la Pointe-de-Mitis là où il garde de beaux souvenirs lors de la réalisation de ses projets. Cet amour a été transmis spontanément à ses étudiants, ce qui m'a rendu curieux de découvrir sa passion envers cet endroit magnifique caractérisé par la colonisation de beaux tapis d’algues vertes filamenteuses sur les rochers de la zone intertidale et d’une abondance remarquable des gastéropodes marins de genre Littorina.

Un grand merci aussi aux professeurs Gwénaël Beauplet et Jean-Pierre Tremblay qui ont accepté, sans la moindre hésitation, de faire partie du comité d’évaluation de mon mémoire de maîtrise.

J’aimerais aussi remercier tout le personnel de l’Institut Maurice-Lamontagne, en particulier Chris McKindsey et son laboratoire, Paul Robichaud et Andrea Wise pour le prêt du matériel ainsi que Michel Giguère pour la réservation des bassins. Aussi, les gardiens de sécurité qui étaient tout le temps sympathiques et compréhensifs.

Je suis particulièrement reconnaissant à mes assistants de recherche Claude et Rémi qui ont montré du professionnalisme en effectuant leurs tâches au laboratoire et sur terrain ainsi que tous les membres de mon laboratoire : Nicolas, Anissa, Karine, Annick, Samuel, Helmi, Katie, Jordan, Carla et Olivier, et leurs précieux commentaires très constructifs concernant mon projet. Je remercie également tous les étudiants chercheurs avec qui j’ai passé deux agréables étés en cohabitation à la maison blanche de l’Institut Maurice-Lamontagne et je leur demande encore mes excuses à propos de l’enclenchement de l’alarme incendie générale dans la maison à 03h du matin à cause de mon poisson oublié sur le poêle.

Mes remerciements vont aussi au dédié personnel du groupement Québec-Océan qui a contribué en partie au financement de mes congrès scientifiques et de mes déplacements sur terrain pour le suivi et la collecte de mes échantillons.

La rédaction de ce mémoire est le résultat de l’encouragement de ma meilleure amie Marie-Pier, qui était tout le temps à mes côtés avec beaucoup d’affection et d’amour pour le meilleur et pour le pire durant cette période. Je t’aime mon bel escargot d’amour.

Finalement, je souhaite dédier mon mémoire de maîtrise à ma famille en particulier mes parents Salem et Rafika qui m’ont toujours encouragé et soutenu financièrement durant toute ma maîtrise sans aucun échange et avec beaucoup d’amour. Leur soutien moral et financier est le fruit de ma réussite. Mes parents auront finalement leur plus beau cadeau, assister, avec beaucoup de fierté et d’honneur, à la cérémonie de collation de garde et voir leur fils obtenir le grade de maître ès sciences de cet honorable établissement l’Université Laval.

Avant - Propos

Ce mémoire comporte deux chapitres 1 et 2 rédigés en anglais sous forme d’articles scientifiques ainsi qu’une introduction et une conclusion rédigées en français. Les observations et expériences qui y sont décrites ont été planifiées et réalisées par l’étudiant sous la direction du coauteur, Ladd Johnson. L’analyse des résultats et la rédaction de chacun de ces articles ont également été faites par l’étudiant, toujours sous la supervision de son directeur de recherche. Les articles en question n’ont pas été soumis pour publication au moment du dépôt final de ce mémoire. L’étudiant sera considéré comme premier auteur lors de la publication éventuelle de ces articles et le co-auteur sera son directeur de recherche.

Présentations d’affiches scientifiques

Marzouk A. et Johnson L.E. (2007) Effet de la qualité nutritionnelle des algues sur les préférences et les performances de Littorina saxatilis. Assemblée générale annuelle de Québec Océan, Rivière-du-Loup (QC, Canada), 22-23 novembre.

Marzouk A. et Johnson L.E. (2008) Effects of algal nutritional quality on the growth and reproduction of an intertidal herbivore, the gastropod Littorina saxatilis. Benthic Ecology Meeting, Providence (RI, États-Unis), 9-13 avril.

Marzouk A. et Johnson L.E. (2009) Effects of feeding preferences on growth and reproduction of an intertidal herbivore, the gastropod Littorina saxatilis. Congrès annuel de la Société Canadienne d’Écologie et Évolution, Halifax (NÉ, Canada), 14-17 mai.

Introduction générale

Les relations trophiques sont les éléments de base des réseaux trophiques et constituent le cadre essentiel de l’organisation d’un écosystème (Lubchenco et Gaines 1981, Crawley 1997). Plusieurs facteurs environnementaux et démographiques peuvent agir comme des sources de variabilité des relations trophiques (Crocket et al. 2002), et pour avancer nos connaissances, il faut simplifier les modèles et les expériences en contrôlant le plus possible les sources de variation de ces relations afin de mieux les décrire et les comprendre. En effet, chaque consommateur se nourrit typiquement sur une diversité de ressources alimentaires (p. ex. proies), et pour comprendre la dynamique des communautés de ces ressources, il faut connaître les déterminants du régime alimentaire du consommateur (Schmidt-Nielsen 1997, Wright et al. 2004). Certes, cela dépend de la disponibilité des diverses ressources alimentaires mais aussi des préférences du consommateur (Thornber 2006, Thornber et al. 2008). Une compréhension de ces préférences nous donne une vision sur le rôle de chaque espèce et de son impact potentiel sur la communauté dans son milieu écologique (Leibold 1999, Breckling et al. 2006).

Les préférences des consommateurs peuvent généralement être déterminées par leur choix alimentaire (Wakefieldet Murray 1998, mais voir Underwood et Clarke 2006), et plusieurs études se sont penchées sur la détermination des préférences alimentaires chez les consommateurs (Thornber 2006, Sauvé 2005, Fratini et al. 2008, Aquilino et al. 2012). Ces préférences sont fréquemment interprétées comme une stratégie d’optimisation énergétique ou nutritionnelle (Albuquerque et al. 2008, Fratini et al. 2008). Cependant, peu d’études ont approfondi les conséquences des choix alimentaires sur la performance écologique, telle que la croissance et la reproduction, des consommateurs, en particulier dans le milieu aquatique (Poore et Steinberg 1999).

Parmi les relations trophiques, l’herbivorie se distingue du fait que les ressources alimentaires sont sessiles, où l’animal a souvent accès à une diversité de ressources alimentaires disponibles simultanément. La diversité des espèces végétales offre donc un choix pour les herbivores en fonction de la composition et la structure de cette végétation (Evjemo et al. 1999; Wright et al. 2004), où les herbivores présentent différentes stratégies

comportementale et physiologique afin de satisfaire leurs besoins nutritionnels (Duarte et al. 2010).

Herbivorie dans le milieu intertidal marin

Le milieu intertidal rocheux est depuis longtemps utilisé comme un grand laboratoire à ciel ouvert, ce qui a permis le développement de plusieurs théories écologiques classiques, telles que la théorie de la perturbation intermédiaire (Connell 1979), la succession écologique (Connell et Slatyer 1977) et l’importance des espèces clés dans une communauté (Paine 1980, Power et al. 1996). Ce milieu est considéré comme un milieu-modèle pour l’étude de la structure des populations et de l’influence du milieu sur ces dernières (Menge et Branch 2001). Il est aussi caractérisé par des gradients physiques causés par les marées qui génèrent des patrons de zonation dans lesquels la distribution des espèces s’effectue selon des gradients verticaux (Harley et Helmuth 2003, Addy et Johnson 2001, Pardo et Johnson 2005). Ces gradients abrupts du milieu abiotique (ex. : force des vagues, dessiccation) peuvent créer une grande variabilité spatiale et temporelle des ressources alimentaires (Underwood et Chapman 1998).

Le rôle de l’herbivorie dans ce milieu est particulièrement évident (Pardo 2004, Heck et Valentine 2006, Aquilino et al. 2012). En effet, le broutage des herbivores marin est l’une des principales relations entre les espèces du milieu intertidal marin (Poore et al. 2012). Ces herbivores peuvent consommer jusqu'à 51% de la productivité primaire nette produite dans leur système, ce qui représente la plus haute valeur parmi les différents types d'écosystèmes (Cyr et Pace 1993, Prado et al. 2007, Poore et al. 2012). Aussi, l’herbivorie peut jouer un rôle prépondérant dans la structure des communautés intertidales en affectant la diversité, la répartition et 1'abondance des organismes (Lubchenco et Gaines 1981, Cyr et Pace 1993, Poore et al. 2012).

Dans les habitats intertidaux, la variabilité spatiale et temporelle des ressources alimentaires des herbivores est une des caractéristiques essentielles de ce milieu (Underwood et Chapman, 1998). Ces ressources alimentaires sont constituées principalement des algues pérennes de grande taille (p. ex. Fucus) et des algues éphémères de petite taille (ex. diatomées et algues filamenteuses) (Steneck et Watling 1982, Frenette

2007). Les algues éphémères, principale source de nourriture des mollusques herbivores (Menge et al. 1986, Cosentino et Giacobbe 2008, Norton et al. 1990), colonisent rapidement les substrats rocheux des milieux intertidaux durant une grande partie de la saison estivale (Nicotri 1977, Plante-Cuny et Plante 1986, Robitaille 2001). Dans certains lieux, on peut donc y retrouver de grands tapis d’algues à travers une grande partie des niveaux de l’intertidal, parce que ces algues sont très tolérantes à la dessiccation. Cependant leur distribution dans la zone intertidale n’est pas égale, principalement à cause des gradients verticaux des facteurs abiotiques (p. ex. la dessiccation). En général, elles sont plus abondantes dans la zone intertidale basse que dans le niveau plus haut, forçant les populations de ce milieu à se tourner vers des ressources alimentaires alternatives (Leroux 2011). Une de ces ressources alternatives est le biofilm qui est constitué de macromolécules organiques et/ou inorganiques présentes sur les surfaces exposées en eau de mer ou sécrétées par les micro-organismes vivant dans ce milieu, puis de bactéries et ensuite de macro-organismes (Compère 1999). Le biofilm contribue à la productivité primaire des côtes rocheuses et il est souvent une importante source de nourriture pour les brouteurs (Thompson et al. 2000). Cette variabilité des ressources entre les niveaux haut et bas de l’intertidal favorise une variabilité dans la force des interactions entre les espèces (Pardo 2004), et influence le comportement de quête alimentaires des herbivores (West 1987, Chapman 2000).

L’abondance et la variabilité des ressources alimentaires entre les niveaux de l’intertidal offrent un choix aux herbivores marins et influencent la manière dont ils occupent leur espace (Picken 1979, Hay 1991, Cannicci et al. 2006). Ce choix peut être traduit par des préférences alimentaires sur différentes ressources individuelles (ex. des espèces végétales vivant seules sans compétiteurs) ou regroupées (ex. en associations avec une ou plusieurs autres espèces végétales) (Cruz-Rivera et Hay 2000, Poore et Hill 2006, Thornber et al. 2008, Aquilino et al. 2012). Plusieurs études ont démontré, chez les consommateurs généralistes, l’importance de la diversité des ressources sur les préférences alimentaires (Bernays et al. 1994, Cruz-Rivera et Hay 2000, Poore et Hill 2006, Worm et al. 2006). Dans plusieurs de ces cas, les consommateurs préfèrent des régimes monospécifiques mais croissent mieux sur des régimes mixtes où le contenu nutritionnel est meilleur dû à une complémentarité entre les ressources alimentaires (Bernays et al. 1994,

Cruz-Rivera et Hay 2000). Dans le milieu naturel marin, le choix des herbivores qui consomment un régime composé d’une ou plusieurs espèces végétales est peu connu. Les études précédentes ont été orientées plutôt sur les facteurs extrinsèques (ex. variations saisonnières, force des vagues, stress de dessiccation (Crocket et al. 2002), et intrinsèques (ex. structure des cellules, composition chimique palatabilité, défense chimique; Cronin et Hay 1996, Heaven et Scrosati 2004, Kimberly et Salice 2012) du régime alimentaire. Ces études ont montré, par exemple, une préférence des herbivores marins pour des ressources en fonction de leurs caractéristiques structurelles (p. ex. les diatomées qui ont une structure membranaire fragile avec une faible teneur en cellulose; Watson et Norton 1985, McShane et al. 1994) chimiques (p. ex. teneurs en carbone, phosphore, acides gras polyinsaturés, lipides, etc.) ou nutritionnelles (p. ex. digestibilité, prise alimentaire).La préférence alimentaire peut dépendre aussi des facteurs intrinsèques des herbivores eux-mêmes tels que la taille de leur appareil buccal et la sécrétion d’enzymes digestives qui leur permettent une meilleure acquisition du régime alimentaire choisi (Crosby and Reid 1971, Hawkins et al. 1989, Norton et al. 1990). Ces interactions plante-herbivores jouent un rôle important dans la structure des communautés intertidales dans une distance relativement courte (McQuaid 1996, Navarette et Menge 1996, Ruesink 1998, Menge et Branch 2001).En effet, à densité élevée, les populations d’invertébrés herbivores peuvent affecter l’abondance et la distribution de leurs ressources alimentaires (Gaines 1985; Hay et Fenical 1988, Crawley 1997, Aquilino et al. 2012). Cependant, d’une façon réciproque, les caractéristiques de la végétation peuvent influencer le comportement et les composantes biodémographiques des herbivores (Evjemo et al. 1999; Wright et al. 2004; Cruz-Rivera et al. 2011).

La théorie de l'histoire de vie se penche sur l'étude de traits liés au développement et à la reproduction d'un organisme (traits d'histoire de vie), tels que la survie, la croissance et la reproduction. Elle vise à comprendre comment une combinaison particulière de ces traits peut avoir évolué au sein d'une population en réponse à certaines pressions sélectives telle que l’allocation des ressources dans l’évolution des espèces (Stearns 1976, Pardo 2004). L'étude de l’allocation des ressources est centrale dans cette théorie : elle fait le lien entre différents traits et les situe dans le cadre plus global d'une stratégie développée en réponse aux conditions environnementales.Les stratégies d’allocation des ressources ont fréquemment été observées chez les herbivores marins, particulièrement en réponse à des

variations dans l’abondance des ressources alimentaires (Russell 1998; Ernande et al. 2004). Ils devraient supporter la survie, la croissance et éventuellement la reproduction. Différentes contraintes et les stratégies adoptées par les animaux peuvent mener à différents patrons de variation de la masse corporelle (Morelissen et Harley 2007; Sorte et al. 2011). Par exemple, Cruz et al. (1998) ont observé chez les littorines, dans une étude en Espagne, la présence d'écotypes distincts entre le haut et le bas de la zone intertidale. Un écotype plus gros avec une coquille striée a été retrouvé dans le haut de la zone intertidale, alors qu'un écotype plus petit avec une coquille lisse a été retrouvé dans le bas. Ces écotypes se seraient développés en réponse à des pressions sélectives différentes (Cruz et al. 1998). Dans le haut de la zone intertidale, où la prédation est fréquente; les escargots y présentent une coquille plus grosse, épaisse et donc difficile à manipuler. Dans le bas de la zone intertidale, l'exposition aux vagues est plus grande; une coquille plus lisse et petite donne moins de prise aux vagues (Johannesson 2003).Dans certaines conditions, ces contraintes peuvent forcer même les individus à survivre à partir de leurs réserves corporelles (Pechenik et al. 1996). Par exemple, il existe des périodes critiques pour la survie des gastéropodes herbivores intertidaux où la disponibilité des ressources alimentaires est limitée et la dégradation de la qualité est marquée (Korpinen et al. 2007;Korpinen et Jormalainen 2008). Cela pourrait s'expliquer d'abord par le fait que ces herbivores montrent de grandes variations au niveau de leur phénotype sur de petites échelles spatiales.

Organisme et système d’étude

Un groupe caractéristique d'herbivores du milieu intertidal dans les régions tempérées est les gastéropodes de la famille Littorinidae (Reid 1996). Ce clade de gastéropodes comporte un grand nombre d'espèces (près de 173; Reid 1989), mais aussi une grande diversification dans 1'utilisation de 1'habitat et les stratégies d’allocation des ressources (Reid 1989, Norton et al. 1990, Johannesson 2003). L’espèce la plus représentative et la plus étudiée de ce groupe est Littorina saxatilis. Elle occupe une grande portion de la zone intertidale et a été abondamment utilisée dans des travaux concernant la structure des populations. Plusieurs caractéristiques biologiques de L. saxatilis en font un excellent modèle biologique pour explorer les interactions entre les éléments trophiques et les attributs individuels (Behrens-Yamada et Mansour 1987). Il s'agit d'une espèce

dominante dans les milieux rocheux de la zone intertidale en Europe et en Amérique du Nord. Son régime alimentaire est composé de micro et de macro algues, particulièrement des diatomées et des algues vertes filamenteuses qui colonisent le zone rocheuse de l’intertidale de façon monospécifique ou en association (Nicotri 1977, Plante-Cuny et Plante 1986, Robitaille 2001), mais aussi des composants vivants (p. ex. bactérie, cyanobactérie) et de matière organique en décomposition qui créent le biofilm superficiel intertidal (McQuaid 1996). Elle exerce un rôle important dans son écosystème où elle peut influer sur le recrutement et la croissance des algues (Norton et al. 1990; McQuaid 1996; Carlson et al. 2006), participer au recyclage de la matière organique et servir de proie à certains prédateurs côtiers (McQuaid 1996).

L. saxatilis est généralement retrouvé en fortes densités dans la zone intertidale

supérieure (McQuaid 1996) et parfois à travers toutes les zones médiolittorales (Addy et Johnson 2001, Pardo 2004). Cette large répartition l'expose à des intensités très variées de plusieurs facteurs biotiques et abiotiques. Cela se traduit par des différences marquées au niveau de sa morphologie, de sa physiologie et de son comportement observables entre les différents niveaux de la zone intertidale (Cruz et al. 1998). À l'instar de tous les mollusques, la croissance de L. saxatilis est indéfinie et son cycle de vie est assez peu commun chez les invertébrés marins : il est ovovivipare. Après la fécondation, les œufs sont conservés dans une poche d'incubation pour l'entière durée du développement des embryons (Reid 1989). La progéniture est libérée dans l'environnement sous forme d'escargots juvéniles complètement formés, à l'exception des organes sexuels qui n'apparaissent qu'une fois la maturité atteinte (Reid 1989). Cependant, la fécondité de cette dernière augmente de manière particulièrement marquée avec la taille corporelle (Pardo et Johnson 2005).En effet, L. saxatilis est un organisme modèle parce qu’on peut mesurer sa performance biodémographique tels que la survie (au laboratoire), la croissance (taille de la coquille) et son succès reproducteur en dénombrant les embryons que la femelle peut contenir dans sa poche d’incubation (Roberts 1979 cité par Hughes 1995, Reid 1989). Plusieurs études ont démontré que des changements dans leur environnement physique et dans les interactions biologiques induisent d'importantes modifications de leur comportement de quête alimentaire (Conan et al. 1992, Addy et Johnson 2001), leur croissance (Johannesson et al. 1997) et leur démographie (Emson et Faller-Fritsch 1976)

ainsi qu’une adaptation aux conditions locales considérable dans leurs habitats (Behrens-Yamada et al. 1989; Kyle et Boulding 2000; Makinen et al. 2008).

Le site d’étude est la Pointe Mitils (48° 41' N, 68° 2' O) situé au bord de l’estuaire du Saint Laurent, à Métis sur mer, Québec. Ce site présente des caractéristiques propices pour observer les sources de variations des traits biologiques de L. saxatilis dues à l’extension de l’étagement intertidal et de la haute densité d'individus dans tous les niveaux (Pardo 2004). De plus, l’action de la glace, chaque année, dénude une grande partie de la surface rocheuse (Bourget 1997), et permet ainsi une nouvelle colonisation des algues vertes filamenteuses (principalement Urospora penicilliformis et Ulothrix flacca) de la fin avril jusqu’à la fin du mois de juillet qui peut même s’étaler jusqu’au mois d’août. Des couches de diatomées colonisent, aussi, les substrats rocheux de la même zone et vivent soit seules ou en colonie avec les algues vertes filamenteuses (Pardo et Johnson 2005, Frenette 2007). La présence des tapis d’algues qui y abondent dans ce site et l’accessibilité réduite au public, facilite la mise en place du projet de recherche. Ce site représente un système relativement facile à manipuler et présente une complexité trophique réduite. En effet, il est possible d’y étudier la formation de tapis d’algues sans l’interférence d’autres organismes tel que des algues pérennes, ainsi que l’effet des préférences alimentaires de ces algues sur les traits d’histoire de vie de L. saxatilis. Cette espèce est particulièrement appropriée pour notre étude car la prédation est plutôt faible et uniforme à travers la zone intertidale (Pardo et Johnson 2005). De plus, tel que décrit ci-dessus, L. saxatilis se caractérise par un développement direct des juvéniles (c’est-à-dire ovovivipare), ce qui nous permet de quantifier la reproduction.

Objectifs de l’étude

Dans un contexte évolutif, les décisions d’approvisionnement d’un organisme exposé à des ressources devraient viser à maximiser la survie et la reproduction. Le premier objectif de la présente étude était d’étudier les préférences alimentaires du gastéropode herbivore marin L. saxatilis et leurs retombées sur ses paramètres biodémographiques. Mon « hypothèse de travail » est que les consommateurs ont des préférences alimentaires et que ces préférences vont influencer sur leur performance biodémographique.

Mon premier objectif est de déterminer les préférences alimentaires de L. saxatilis. Les sous-objectifs sont :

1) déterminer si L. saxatilis démontre une préférence parmi différents types de ressources alimentaires simples et composés;

2) évaluer l’effet des caractéristiques structurelles des ressources sur les préférences;

3) Établir le lien entre la distribution des littorines et celles des ressources dans la zone intertidale;

4) envisager une relation entre la préférence alimentaire et les caractéristiques structurelles et biochimiques des différents régimes étudiés.

Mon deuxième objectif est de décrire l’effet des préférences alimentaires sur les paramètres biodémographiques de L. saxatilis. Les sous-objectifs sont :

1) déterminer les paramètres biodémographiques de L. saxatilis nourris par différents types des ressources alimentaires simples et composées;

2) évaluer l’effet des caractéristiques structurelles sur les paramètres biodémographiques;

3) déterminer le lien entre les préférences alimentaires et les paramètres biodémographiques de L. saxatilis;

4) établir le lien entre l’allocation des ressources et la provenance de L. saxatilis dans le milieu intertidal;

5) évaluer le rôle du biofilm microbien comme source de nourriture supplémentaire pour L.

saxatilis lorsque les autres ressources alimentaires sont limitées.

L’avancement de nos connaissances sur la relation entre la composition des

ressources alimentaires telles que les diatomées et les algues vertes filamenteuses du milieu intertidal et le choix de l’herbivore marin L. saxatilis sur les différents types de régimes que peut former ces ressources nous permettra d’expliquer la distribution spatiale de cette

espèce dans son milieu et l’influence des régimes alimentaires sur les paramètres biodémographiques de l’herbivore L. saxatilis.

Chapitre 1.

DIETARY PREFERENCE AND FEEDING BEHAVIOUR OF

THE HERBIVORE GASTROPOD Littorina saxatilis

Anis Marzouk

1, Ladd E. Johnson

11

Département de biologie & Québec-Océan, Université Laval,

Québec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada

Résumé

Les préférences alimentaires des herbivores marins peuvent être liées aux caractéristiques et à la diversité des ressources disponibles. Cette étude évaluait la préférence alimentaire de l’escargot Littorina saxatilis entre les algues vertes et les diatomées offertes en régime monospécifique ou mixte. Dans une expérience cafétéria au laboratoire, les escargots ont préféré le régime de diatomées monospécifique. Dans une expérience parallèle, en enlevant les attributs structurels des algues, la préférence aux diatomées a diminué, mais est demeuré supérieure des algues vertes seules, suggérant que les attributs structurels et non structurels des ressources affectent la préférence de cet herbivore. Sur le terrain, la densité des escargots était plus élevée sur les tapis de diatomées que sur les autres ressources potentielles, suggérant que leur préférence des diatomées influence leur stratégie de quête alimentaire. Les préférences alimentaires des herbivores marins et la distribution des ressources semblent influencer la distribution spatiale des consommateurs.

Abstract

Dietary preferences of marine herbivores may be related to the characteristics and the richness of the foods available. This study evaluated the dietary preference of the snail

Littorina saxatilis between filamentous green algae and diatoms, in pure or mixed diets. In

laboratory-cafeteria feeding experiments, snails preferred monospecific diet of diatoms. In a parallel experiment, where structural attributes were removed, the preference for diatoms was reduced but still higher than for the monospecific diet of green algae, suggesting that both structural and non-structural attributes of the food resources affect the preference of this herbivore. Field surveys indicated that snail densities were higher on patches of diatoms than on other potential foods, suggesting that their preference for diatoms influences their foraging behaviour. Feeding preferences of marine herbivores and distribution of resources appear, consequently, to play a role in determining the spatial distribution of consumers.

Introduction

Herbivory is an important ecological process in many ecosystems (Potvin et al. 2003, Sauvé 2005, Heck and Valentine 2006), but particularly in marine benthic environments where abundant species such sea urchins and snails can control the distribution and abundance of marine algae (Lubchenco and Gaines 1981, Hawkins and Hartnoll 1983, Thornber 2006, Poore et al. 2012). Typically, these grazers have a range of potential food resources depending on the diversity of plant species within the assemblage. Their choice canhave both effects on the assemblage itself (e.g., selective grazing of particular species; Norton and Benson 1983, D’Antonio 1985, Gunnill 1985) as well as on the grazers (e.g., growth, reproduction).

The dietary preference of marine herbivores has received considerable attention (Hawkins and Hartnoll 1983, Himmelman and Dutil 1991).Most studies have focused on the defensive characteristics of the algae (largely structural [Hay 1981, Watson and Norton 1985] or chemical [Pereira et al. 2002]) that serve as deterrents to grazing (Hay and Fenical 1988, Van Alstyne 1988). In general, smaller, morphologically-simpler forms are considered to be more vulnerable to grazers (Steneck and Watling 1982), and poorly-defended ephemeral species are considered to be a good food resource for marine herbivores (Hay et al. 1987). There are, however, few studies that attempt to determine how feeding preferences vary within these groups, although the classic functional grouping of benthic algae with regards to susceptibility (Steneck and Watling 1982) distinguishes benthic diatoms (Functional Group 1) from filamentous algae (Functional Group 2), suggesting the potential for discrimination by herbivores. Previous studies suggest that marine herbivores may even select habitats, and therefore access to food, on the basis of several factors such as food abundance, nutritional content, noxious chemicals, and plant morphological structures (Hay and Fenical 1988; Strauss et al. 2002).

This study examines food choice by the ribbed periwinkle, Littorina saxatilis, a small but ubiquitous species of marine gastropod on temperate rocky shores in the northern hemisphere. In particular, we address the question of how the structural attributes of its primary food sources affect its dietary preference and feeding behaviour. Specifically, we performed food choice experiments in the laboratory involving both whole algae of

different functional groups as well as reconstituted algae (a mixture of ground algae and agar) in which structural attributes that might influence food choice were removed. To assess how any observed preferences might affect foraging, we also documented the distribution of snails in response to spatial variation in food abundance.

Materials and methods

We conducted, field studies at Pointe-Mitis (48° 41’ N, 67° 02’ W), located on the southern shore of the St. Lawrence maritime estuary, Quebec, Canada. Littorinid snails (Littorina sp.) are common on this ice-scoured rocky shore. L. saxatilis is the most abundant herbivorous snail there, occurring in all zones of this intertidal shore. It is frequently observed on algal mats composed of filamentous green algae (Urospora

penicilliformis and Ulothrix flacca; Chlorophyta) and diatoms (Bacillariophyceae),

especially chain-forming pennate diatoms such as Melosira sp., Synedra sp., Fragilaria sp.,

Berkeley arutilans, Cocconeis sp. and Navicula sp. These ephemeral mats form on rock

surfaces in wave-exposed areas where grazing by snails is reduced (Addy and Johnson 2001) and form anew each spring, gradually senescing over the summer.

In lower intertidal zones, rock ridges are usually covered with an algal mat in spring and summer (except near crevices used by the snails as refuges from wave action; Addy and Johnson 2001, Pardo 2004). Higher zones consist of a matrix of bare rock surfaces, macroalgal canopies (Fucus spp. and Ascophyllum nodosum), and mats of green algae and diatoms, which typically disappear several weeks before those in the low zone.

Laboratory feeding preference assays

We collected both snails and algae at five different locations along a 1-km stretch of shore. We collected snails at each location from both the high and low intertidal zones as both snail size and food availability vary markedly between these zones (Pardo and Johnson 2004). We selected snails between 3-5 mm in shell height to assure that we had reproductive individuals (Pardo and Johnson 2005). We removed algae from the rock using a paint scraper. Both were then transported to the laboratory (a 10-minute trip) where we maintained snails in seawater aquaria. For whole-algae preference trials, algae were held in

refrigerators on damp paper towels in plastic bags, whereas for reconstituted-algae trials, algae were lyophilised (BANCONCO Freeze Dryer 8, at -100°C and 0.2 bars) and then ground into a fine powder (Wiley Mill, mesh size 80), a process that should not affect the chemical components or nutritional differences among food types (Bolser and Hay 1996; Hay et al. 1994). Ground algae were stored in glass boxes in the laboratory under ambient conditions until used in experiments.

Once a month in the summer, we conducted feeding experiments in the laboratory using a "cafeteria test" in which we simultaneously offered two kinds of food (filamentous green algae and diatoms) to individual snails placed within isolated feeding arenas. The first experiment consisted of giving snails a choice between these two types of algae in their natural whole state, and involved presenting these algae simultaneously in various combinations: (1) green algae alone, (2) diatoms alone, (3) a mixture of green algae and diatoms, and (4) a control of no food. The control treatment was used because in the field the rock surface is often denuded by grazers and thus is often an “option” for snails foraging in this environment. Thus the experiment mimicked the natural conditions since snails frequently encounter these four different choices in the intertidal zone. The actual laboratory arenas were a series of 90 plastic compartments (3x3 cm) in which individual snails could be isolated. The floor of the arenas was a rigid plastic grid with 1x1 cm openings, covered by plastic window screening (1-mm mesh openings) to support the algae and the snails. Within each arena, snails were provided food, ad libitum, in small (1x1 cm) mesh envelopes (window screening folded and sewn shut) to facilitate the grazing of snails, which could then use their radula to ingest the algae as under normal conditions. Mesh envelopes were arranged on the periphery of the floor of the arena (two envelopes of each type – 8 total) with an open area in the middle where the snail was placed at the beginning of the trial.

During feeding trials, snails were confined within their individual arenas by window screening placed on the top of the arenas, permitting seawater to circulate through the arenas. Feeding trials lasted 2 hours, after which individuals were immediately dissected under a stereomicroscope to identify which kind of food was found in the digestive tract. This feeding period was long enough for the snails to select a food type but also short

enough that the food would not be degraded (A. Marzouk, personal observation). We could easily identify food type based on the color and texture of the content of the digestive tract. A total of 90 such trials were conducted (i.e., 9 snails from each of the two zones for each of the five locations).

To reduce any effect of the structural attributes of the algae, a second parallel experiment was conducted in which the ground algae (see above) were offered to the snails. For the food choice experiment, ground algae were reconstituted into an "artificial food" at natural wet/dry mass ratios by adding 2 g of dry ground algae to a heated deionized water/agar mixture (13 ml/0.18 g; Bolser and Hay 1996, Thornber et al. 2006). We again presented individual snails a choice of three food diets (green algae, diatoms and green algae-diatoms mix held in mesh envelopes) and the control and then analyzed them as in the first experiment. A total of 90 replicates were again conducted.

Field surveys

To determine if snails were associated with any particular food type, we measured the density of snails at the five sites from which algae and snails were collected. Densities were estimated by collecting all snails from six 0.25-m2 quadrats haphazardly placed along two 10-m transects in the high zone and two transects in the low zone from each type of food (filamentous green algae, diatoms, green algae-diatoms mix and bare rock surfaces, i.e., no food). For each snail collected, we noted its sex and, if female, reproductive status (gravid or not). Snails were sampled three times throughout summer (June, July and August) to assess changes in the foraging behaviour of grazers over time.

Data from laboratory experiments were analysed with statistical analysis software (SAS) using a 4-factor ANOVA (fixed factors: zone, food type, food condition and month). The variance was modeled as a power of the mean structure in the mixed model. The response variable (number of snails) was analyzed by taking the square root for all models of preference. Data from field surveys were analyzed using split-split plot ANOVA with three fixed factors (zone, food type and month) and two random factors (site and transect). Other random terms were specified to meet the structure experimental design. For some models, we added an additional fixed factor (sex or reproductive status). The denominator

degrees of freedom were adjusted using the method of Kenward-Roger (Kenward and Roger 1997). Multiple comparisons, with LSD test, were used to find the sources of differences in factors for which there was a significant difference. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made.

Results

Feeding preference essays

In trials with whole food, L. saxatilis exhibited a strong preference for diatoms, consuming them twice as often as any of the other three diets. The other choices (green algae and the Diatom - green algae mix) did not differ significantly from one another (Figure 1.1.A, F3,984 = 64.10, P< 0.0001). No differences were observed between snails from the high shore compared to those from the low shore (Figure 1.1.A.B., F3,984 = 0.08, P = 0.97).

Figure 1.1. Multi-choice laboratory feeding experiments with Littorina saxatilis on different algal diets; (A)

Multi-choice whole-food comparisons and (B) Multi-choice ground-food comparisons, offer to L. saxatilis individuals harvested from the the high (black bars) and low tidal zones (empty bars). ”D-GA mix” represents a mixture of diatoms and green algae. Bars are averages for high and low zones over the three months of the study with standard errors (n = 3months). Horizontal lines group treatments that are not significantly different from each other. See Tableau A1 for statistical details.

When structural characteristics were removed from the algae (i.e., the algae freeze-dried, ground, and reconstituted), the strong preference for diatoms disappeared (Figure 1.1.B, F3,984 = 3.01, P< 0.0001). However, there was still a strong and significant difference between food types containing diatoms and green algae alone. Again, results were not different for snails collected from high and low zones (Figure 1.1.B, F3,984 = 0.35, P = 0.79).

Field surveys

Density of snails on diatoms and mixed diatom-green algal mats were significantly higher than green algal mats or bare rock surfaces (Figure 1.2, F3,600 = 104.74, P< 0.0001). The same results were observed in both the high and low zones, although snail density was higher in the high zone (Figure 1.2, F3,600 = 1.34, P= 0.03). The same results were observed throughout all months, with the exception of the high zone in August, where no grazing preference was observed although all differed from the control (Figure 1.2, F6,600 = 2.13, P= 0.06). Finally, no difference was observed between feeding preference and gender or reproductive status (Figure 1.2, F6,1056= 0.28, P= 0.94).

Figure 1.2. Mean density of Littorina saxatilis (bars represent standard errors) during the summer

(June-July-August) in the high and low tidal shore zones at five study sites near Pointe-Mitis, Québec, Canada. “D-GA” represents mixed diatom-green algal mats, “D” diatom mats, “GA” green algal mats, and “C” bare rock surfaces. Bars are averages for six quadrats in each of five zones (n=30). Horizontal lines group non-significant treatments. See Tableau A2 for statistical details.

Discussion

Laboratory feeding experiments suggest that Littorina saxatilis can choose between different foods as it showed a clear preference for diatoms over green algae, even though in general diatoms and simple green algae are both generally considered palatable food sources (Steneck and Watling 1982; Geddes and Trexler 2003). This choice appears to be at least in part based on structural differences, as the preference for diatoms was greatly reduced when the attributes of algae were removed.

Structural differences can occur at multiple levels. At the highest level, the overall plant architecture (e.g., size, branching) can affect the ability of an herbivore to ingest plant material. In this regard, there are substantial differences between green algae and chain-forming diatoms in spite of their common filamentous nature. Green algal filaments are series of tightly connected cells often covered by a sheath that protects them from mechanical damage and drying. Intertidal species are considered particularly well protected from stress by their thick cell walls and sheaths (Rodela et al 2010). In contrast, diatom cells are generally more loosely connected and mechanically easy to disassociate. Indeed, in term of susceptibility to grazing, diatoms are considered more vulnerable than filamentous algae (Functional groups 1 and 2 sensu Steneck and Watling [1982]). Snails may thus find it easier to ingest diatoms with their radula, the complex feeding apparatus found uniquely in molluscs (Sommer 1999, Hillebrand et al. 2000). Large differences in the composition of the diet appeared to be correlated to differences in mouthparts in gastropods, and the type of the radula is strongly related to the food consumed by the animals (Steneck and Watling 1982).The taenioglossan radula found in littorinid snails is moderately more robust compared to other snails (Steneck and Watling 1982) with shorter and stouter teeth that are able to “rake” rather than “sweep” food into the mouth. The square, straight-edged teeth of L. saxatilis are considered adapted for grazing on hard surfaces (e.g., on rocks and perhaps lichens; Hawkins et al. 1989). Thus diatoms may be easier to consume, especially chain-forming species (Nicotri 1977), whereas the architectural aspects of filamentous green algae (e.g., long chains of tightly-jointed cells surrounded by a common sheath) may interfere with ingestion processes. This difference in

ease of ingestion may then lead to the observed preferences for diatoms relative to green algae.

At a lower level – the cell wall – there are also fundamental differences between diatoms and green algae. Beyond the radular action involved in the ingestion of food, gastropods have no other mechanical means to crush or grind food. Diatom cell walls are composed of silica and are likely to be more easily crushed when ingested than green algal cells, which normally have thick cell walls (Rodela et al. 2012). Our findings thus provide support for the idea that significant ecological consequences can arise from differences in cell wall structure among algal species (Hay and Fenical 1988, Strauss et al. 2002). In this case, even after ingestion, green algal cells may be more resistant to rupture, and thus access to cellular contents may be more difficult to attain.

Removal of structural characteristics (i.e., plant architecture and the integrity of cells) by grinding did not, however, totally eliminate grazer preferences as the pure green algal treatment was still consumed less than the pure diatom or algal mixture treatments even after drying and grinding. This result may be due to two primary possibilities: (1) differences in nutritional value between diatoms and green algae and (2) differences in chemical defences. For the former, diatoms are likely to have a higher nutritional value as they can be rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are energetically valuable and play an important role in regulating cell membrane proprieties and other organismal processes (Beach et al. 1970, Ahlgren et al. 1990). The higher lipid content in diatoms is generally thought to be due to the need to store energy efficiently and maintain a neutral buoyancy, which is particularly challenging due to the weight of the siliceous cell walls. While this problem is more relevant for planktonic diatoms, high lipid content is a general characteristic of all diatoms despite substantial variation among species (Courtois et al. 2012). The composition of the cell wall itself will also have an effect on the nutritional value of the different food types. For diatoms, the silica cell walls provide no nutritional value, but may only represent a small fraction of the biomass ingested. In contrast, the thicker cell walls of green algae (or more technically, their extracellular matrix, ECM) may represent a large fraction of the ingested biomass. Although this material is, in theory, digestible, such energy extraction requires specific enzymes that may not be produced by

the grazers or their symbiotic gut fauna. Green algal ECM varies among species, but among the algal family in which Ulothrix and Urospora are found (Ulvophyceae), cellulose, β-mannans, β-xylans, and sulfated polysaccharides are common components of the ECM (Domozych et al 2012), and cellulose in particular can be a major component of the cell membranes in the filamentous green algae, providing mechanical resistance to cell walls. It is unclear, however, if such polysaccharides have a nutritional value as their presence can affect digestibility (Greenfield and Lane 1953, Grantham et al. 1993, German 2009), and specific enzymes (e.g., cellulases) are required to digest such molecules. Diet is a factor likely to affect the cellulolytic activity in animals, and cellulolytic activity in animals generally corresponds to the level of cellulose in the food (Crosby and Reid 1971). Cellulases have been recorded from a number of gastropods (Tanimura et al. 2013), including littorinid snails (Elyakova et al. 1968, Schmidt-Nielson 1997). However, careful examination of extracts of the snails' digestive gland and intestinal wall failed to reveal any cellulase activity, although cellulase is readily found in intestinal contents (Florkin and Lozet 1949). This observation suggests a major role of intestinal microorganisms, but the fact that an extract of digestive organs does not reveal the enzyme does not necessarily exclude the possibility that the animal may produce the enzyme itself (Schmidet-Nielson 1997). Regardless, it remains unknown if they are produced in sufficient quantities to extract much energy from these complex polymers. If not, then the cell wall material of green algae may passively interfere with digestion by occupying space within the digestive tract without providing any nutritional value. In addition, if whole cells are ingested during feeding, the cell walls may block access to the cellular contents.

Finally, we cannot discount the possibility that green algae use chemical defenses, e.g., the production of toxic secondary metabolites. Although chemical defences are not usually found in ephemeral algae (Paul et al. 2011), chemicals that depress invertebrate feeding rates have been found in a number of simple green algae (Paul et al. 1992, Meyer and Paul 1995, Van Alstyne et al. 2006, Van Alstyne et al. 2009, Paul et al. 2011). However, to our knowledge, no such products have been found in either of the green algal genera found in the algal mat.

Regardless of the precise mechanisms, grazer preference for diatoms appears to contribute to the distribution of snails in the field, with higher densities found on algal mats dominated by diatoms than on those dominated by green algae. Given the limited mobility of this grazer (net displacements of approximately 30 cm.d-1; Pardo and Johnson 2004), this pattern likely represents elements of both food choice and habitat selection. However, this process does not apparently work at larger spatial scales as we generally found higher snail densities in the high zone where diatoms mats are generally less abundant. Whereas the lower abundance of diatoms in this zone on the high shore could be the result of losses to herbivory, it may also be due to the greater stresses associated with desiccation (Courtois e al. 2012). Likewise the typical disappearance of diatom mats before the green algal mats (2007 was an exceptional year in which algal mats persisted until August; L.E. Johnson, pers. obs.) could also be attributed to either grazing losses or desiccation stress. Regardless, given the ephemeral nature of the diatom mat, other ecological factors are also likely controlling snail distribution. For example, previous work has shown that snail foraging behaviour is affected by water motion (e.g., wave forces), and snails living lower on the shore are often restricted to foraging in areas surrounding spatial refuges such as crevices (Addy and Johnson 2001; Pardo 2004).

In summary, we have shown here that this intertidal herbivore has a distinct preference for benthic diatoms over filamentous green algae, two food resources that are widely, if only seasonally, available in its environment. This preference appears to be based on both structural and biochemical characteristics as treatments to remove structural attributes only partially eliminated this preference. Whether the biochemical attributes involve nutritional aspects associated with digestibility of cell wall components (e.g., cellulose) or the nutritional values of the cell contents remain to be seen, but, based on our current knowledge, we suggest that the ease of ingestion of diatoms and their high concentration of lipids are the main reasons for this preference. It remains to be seen if the results that we observed are common elsewhere and if other factors could lead to different conclusions. Our field observations suggest that the preference that we observed affects the foraging behaviour of this species, leading to higher densities of this consumer in areas of high abundance of its preferred food resources within an intertidal zone. Likewise, further study is needed to determine the impact of these behaviours on the individual performance

and population dynamics of the consumer as well as its ecological impact on its food resources.

Acknowledgments

We thank Claude Leroux for assistance with sample collection, laboratory assays and logistics in the field and Chris McKindsey and Fisheries and Oceans Canada for use of laboratory facilities at the Maurice Lamontagne Institute. We also thank my cousin Arwa and Johnson Lab colleagues Thew and Katie for precious help with correction of syntax in the English version. This study was funded in part by a grant from Québec-Océan, le groupe interinstitutionnel de recherches océanographiques du Québec and a Discovery Grant (LEJ) from the Canadian Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC).

Chapitre 2.

EFFECTS OF DIET ON LIFE-HISTORY TRAITS

OF THE MARINE HERBIVOROUS

GASTROPOD Littorina saxatilis

Anis Marzouk

1, Ladd E. Johnson

11

Département de biologie & Québec-Océan, Université Laval,

Québec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada

Résumé

Le régime alimentaire peut jouer un rôle important dans la détermination des traits d’histoire de vie des consommateurs. Des essais de type jardins communs ont été conduits au laboratoire et sur terrain afin de comprendre l’influence de différents régimes alimentaires d’algues vertes et de diatomées, offerts sous forme naturelle ou reconstituée, sur la survie, la croissance et la reproduction de l’escargot Littorina saxatilis. Les résultats ont montré que les escargots peuvent survivre et se reproduire même en absence de nourriture, probablement grâce à la couche microbienne du biofilm formée. En revanche, les juvéniles ont enregistré une croissance élevée sur le régime de diatomées monospécifique ou mixte, due probablement à la qualité nutritionnelle des algues liée à leurs caractéristiques structurelles et biochimiques. Finalement, la croissance était plus importante dans le haut du milieu intertidal. La sélection contre-gradient sur la grande taille des individus provenant du niveau bas explique, probablement, cette observation.

Abstract

Diet can play an important role in determining the life history traits of consumers. Common garden essays were conducted, both in laboratory and field, in order to understand the influence of different diets of green algae and diatoms, in a whole natural form and in a reconstituted form, on survival, growth and reproduction of the snail Littorina saxatilis. Our results showed that snails can continue to survive and to reproduce, even when food was limited, probably because of the microbial biofilm. Juvenile growth was, in contrast, higher for individuals provided only with diatoms or a mixed diet, suggesting that differences were due to nutritional quality of the algae, and also possibly to structural or biochemical differences. Finally, we recorded higher growth rates for individuals from high shore levels, apparently due to counter gradient selection against large size in lower shore levels.

Introduction

Foraging decisions should reflect the energetic and nutritional needs of the consumers, and, theoretically, their choices should reflect strategies to maximize fitness, either in limiting exposure to risks (i.e., survival) or maximizing energetic gains (i.e., growth and reproduction) (Catteral et al. 1989, Cezilly and Benhamou 1996). Such considerations are often only made in terms of the quantity of resources, but the diet of consumers generally includes a variety of food resources. Thus aspects of quality must be taken into consideration, especially as consumers typically show preferences for certain types of food over others (Wakefield and Murray 1998, Thornber 2006), presumably due to differences in their nutritional quality.

The situation is particularly relevant to herbivores as their food resources are not mobile, and thus choosing between different types is less challenging than it might be for predators of mobile prey. Indeed, herbivores often have a true choice in their foraging decisions as food resources can be available to them quasi-simultaneously. The system is, however, dynamic, and the foraging choices that herbivores make can have a strong negative impact on the abundance of vegetation (Cooke and Farrel 2001, Côté et al. 2004). A decrease in the quantity and quality of food resources may in turn influence life history traits such as survival, growth, and reproduction (Loison and Langvant 1998, Andersen and Linnell 2000).

Typically, energetic resources are allocated first to basic life functions (i.e., survival), then to growth and finally to reproduction although once an organism reaches an adult size, growth may become less of a priority, especially among organisms with determinant growth. Many studies have examined the effects of environmental factors on the behaviour and life history traits of aquatic herbivores (Goverde 2000, Estoy et al. 2002, Kenneth 2005, Pardo and Johnson 2005), but it is not always obvious which traits are most likely to be affected by variation in food resources. Relatively few studies have examined the impact of food quality on these animals (Robert et al. 2001), especially for mobile herbivore gastropods.

In intertidal habitats where extremely sharp physical gradients occur (Menge and Branch 2001), herbivorous gastropods can exhibit large habitat-dependent phenotypic variability between populations separated by even a few meters (Makinen et al. 2008). Explanatory efforts have focused primarily on the influence of abiotic factors, but rarely has such variation been experimentally linked to variation in biotic factors such as the quantity and quality of available food resources (Ruckelshaus et al. 1993). Moreover, phenotypic variation has often been attributed to plasticity in the response of intertidal herbivores because the large dispersal of most invertebrates by planktonic larvae ensures that local adaptation cannot occur over small spatial scales (e.g., high and low shore levels). However, certain species can have quite limited dispersal, especially those with direct development (i.e., encapsulated larvae or brooded embryos), and multiple studies have shown both genetic differentiation and local adaptation over the scales of meters across the shore (Behrens-Yamada 1989; Kyle and Boulding 2000, Johannesson 2003). The most well studied case of local adaptation is that of the rough periwinkle, Littorina saxatilis, a herbivorous gastropod found on temperate and polar shores in the northern hemisphere. Reproduction in this ovoviviparous species involves internal fertilization, brooding of embryos and, finally, the release of “crawl-away” juveniles. Thus, unlike most other marine species, there is very little gene flow within populations, creating the potential for local adaptation.

In higher latitudes, intertidal communities can be chronically disturbed by ice scour (Archambault and Bourget 1983), which removes perennial macroalgae and sessile invertebrates (e.g., barnacles and mussels) from much of the shoreline, leaving rock surfaces denuded. These conditions lead to the development of algal mats consisting of mixture and pure stands of ephemeral algae, especially diatoms and filamentous green algae. L. saxatilis is frequently found grazing upon live filamentous green algae and diatoms in the field. While this species has shown a preference for diatoms in the lab (Chapter 1), it is possible that a mixed diet may be a better diet for growth and reproduction as seen in both natural (Bernays et al. 1994, Cruz-Rivera and Hay 2000, Poore and Hill 2006, Worm et al. 2006, Aquilino et al. 2012) and the more applied situation of animal husbandry (Klopfenstein et al. 2008, Moya et al. 2010) and human nutrition (Mennella and Trabulsi2012, Kuo 2013).

![Tableau A1 : Résultats d’une ANOVA sur les préférences alimentaires au laboratoire (Facteurs fixes : Zone [basse, haute], Diète = régime alimentaire [algue verte, diatomée, mélange, témoin], Mois [juin, juillet, août], Forme [entière, broyée])](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/6671527.182859/85.918.173.797.229.951/tableau-résultats-préférences-alimentaires-laboratoire-facteurs-alimentaire-diatomée.webp)

![Tableau A2 : Résultats d’une ANOVA sur la répartition sur le terrain (Facteurs fixes : Zone [basse, haute], Habitat [tapis d’algues vertes, tapis de diatomées, tapis mixte, témoin = roche nue], Mois [juin, juillet, août], facteur aléatoire : Sexe [mâle,](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/6671527.182859/86.918.121.768.185.735/tableau-résultats-répartition-terrain-facteurs-habitat-diatomées-aléatoire.webp)

![Tableau A3 : Résultats d’une ANOVA sur la reproduction sur le terrain (Facteurs fixes : Zone [basse, haute], Diète = régime alimentaire [algues vertes entières, diatomées entières, mélange entier, algues vertes broyées, diatomées broyées, mélange broyé,](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/6671527.182859/87.918.164.799.175.340/résultats-reproduction-facteurs-alimentaire-entières-diatomées-entières-diatomées.webp)

![Tableau A6 : Résultats d’une ANOVA sur la croissance au laboratoire (Facteurs fixes : Zone [basse, haute], Diète = régime alimentaire [algues vertes entières, diatomées entières, mélange entier, algues vertes broyées, diatomées broyées, mélange broyé, té](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/6671527.182859/88.918.126.755.437.606/résultats-croissance-laboratoire-facteurs-alimentaire-entières-diatomées-diatomées.webp)