© Maxime Blanchard, 2020

Crafting democracy

Mémoire

Maxime Blanchard

Maîtrise en science politique - avec mémoire

Maître ès arts (M.A.)

Crafting democracy

Maxime Blanchard

Mémoire

Sous la direction de:

Résumé

Est-il possible pour les pays en développement d’améliorer la qualité de leur démocratie via la réforme de leurs institutions politiques? Plusieurs nouvelles démocraties ont emprunté cette approche, adoptant régulièrement des réformes électorales dans le but d’encourager le développement de comportements politiques jugés normativement plus désirables dans un cadre démocratique. Cette tactique a notamment été très populaire en Amérique latine depuis que la région a transité vers la démocratie au tournant des années 1980. Les résultats de plusieurs études supportent l’affirmation selon laquelle les institutions électorales contribuent à définir le comportement des élites politiques. Nous en savons toutefois beaucoup moins sur la manière dont les électeurs réagissent aux réformes institutionnelles. Le cas colombien est particulièrement instructif à cet égard puisqu’une réforme électorale adoptée en 2003 a fortement diminué la personnalisation politique, de manière à recentrer les élections nationales sur les partis et leurs programmes. De manière plus précise, la réforme a contribué à abaisser significativement le nombre de partis et augmenter la discipline au sein de ceux-ci. Ces changements devraient avoir rendu plus facile pour les électeurs d’apprendre à connaître le programme des partis et de voter en conséquence, rendant incidemment plus probable l’expression d’un vote idéologique. En utilisant des données d’enquêtes d’opinion publique, nous avons élaboré une mesure idéologique bidimensionnelle afin de tester nos attentes théoriques. Les principaux partis colombiens ayant participé aux élections nationales de 1998 et 2006 ont été positionnés sur cette échelle idéologique en s’appuyant sur les réponses offertes par leurs élus à des questions traitant de préférences et d’attitudes politiques. Les répondants colombiens aux vagues 1998 et 2007 du latinobaromètre ont ensuite été positionnés à leur tour sur cette même échelle afin de comparer leur positionement idéologique à celui des partis parmi lesquels ils pouvaient choisir dans le cadre de ces deux élections. À l’aide d’un modèle logit conditionnel, nous avons estimé la fiabilité de la distance idéologique entre les électeurs et chaque parti en tant que prédicteur du vote. Les résultats offrent un support modéré à nos attentes théoriques, suggérant que la distance idéologique entre un électeur et un parti prédit légèrement mieux le vote après la réforme. Nos résultats sont encourageants pour les nouvelles démocraties puisqu’ils suggèrent qu’il est effectivement possible pour celles-ci d’approfondir la qualité de leur démocratie en modifidant la structure d’incitatifs à laquelle sont confrontés les électeurs et les élites politiques.

Abstract

Can countries of the developing world improve the quality of their democracy through institutional changes? Many new democracies have taken such route, with electoral system reforms frequently adopted in the hope of fostering normatively desirable po-litical behaviors. The tactic has been very common among Latin American countries since the region transited to democracy at the turn of the 1980s. A significant body of evidence has been gathered to support the argument that elite behavior is impacted by the shape of electoral institutions. Much less is known, though, about the reaction of voters to electoral reforms. The Colombian case is highly instructive in that regard, as an electoral reform adopted in 2003 substantially diminished political personal-ization to make parties and their programs more significant determinants of national elections. More specifically, the reform made parties much less numerous and fostered greater party discipline within them. Such changes should make easier for voters to know their programs and vote accordingly, thus making more likely the expression of an ideological vote. Using public opinion survey data, we built a bi-dimensional ideological measure to asses our expectation. All major Colombian parties competing in the 1998 and the 2006 national elections were positioned on our ideological scale using the answers given by their deputies to questions about political attitudes and preferences. Colombian respondents to the 1998 and 2007 latinobarometers were also positioned on the scale to compare their ideological preferences to that of the parties they could choose from during those two elections. Using a conditional logit model, we estimated the reliability of ideological distance between voters and each party as a predictor of vote choice. We find qualified evidence supporting our theoretical expec-tations positing that ideological voting should have become more likely in Colombia after the implementation of the 2003 electoral reform. Our results are encouraging for new democracies as they suggest that it might very well be possible for them to deepen the quality of their democracy by reshaping the incentives to which are faced both voters and elites during elections.

Table des matières

Résumé . . . ii

Abstract . . . . iii

Remerciements . . . . ix

Introduction . . . 1

0.1 Institutional Reforms in Latin America . . . 3

0.2 Research Question . . . 9

0.3 Case Selection: Colombia and the Quest for Order . . . 10

0.4 Thesis Overview . . . 12

Chapter 1: The Colombian Case . . . . 13

1.1 Colombian Elections Before the Reform . . . 15

1.2 The 2003 Electoral Reform . . . 18

Chapter 2: Theoretical Framework . . . . 23

2.1 Ideology and the Vote . . . 25

2.1.1 Normative Considerations . . . 25

2.1.2 Political Sophistication and the Coherence of Ideology . . . . 27

2.1.3 Ideology and Voting in New Democracies . . . 29

2.2 Electoral Institutions and Political Competition . . . 30

2.2.1 Mechanical Effects . . . 31

2.2.2 Psychological Effects . . . 33

Chapter 3: Empirical Expectations . . . . 35

3.1 Number of Parties and the Ideological Vote . . . 41

3.2 Party Discipline and the Ideological Vote . . . 45

Chapter 4: Method . . . . 50

4.1 Data . . . 50

4.2 Theoretical Approach . . . 51

4.3 Overview of the Spatial Voting Model . . . 52

4.4 Mapping Ideology . . . 54

4.5 Mesuring Preferences . . . 58

4.5.2 Among Parties . . . 62

4.6 Measuring the Ideological Vote . . . 63

Chapter 5: Empirical Analysis . . . . 70

5.1 Descriptive Analysis . . . 70 5.2 Regression Analysis . . . 71 Conclusion . . . . 78 Beyond Colombia . . . 82 Appendix . . . . 85 References . . . . 86

List of Tables

1 Institutional reforms in Latin America (1978-2008) . . . 4 5.1 Ideological voting in Colombian elections . . . 72

List of Figures

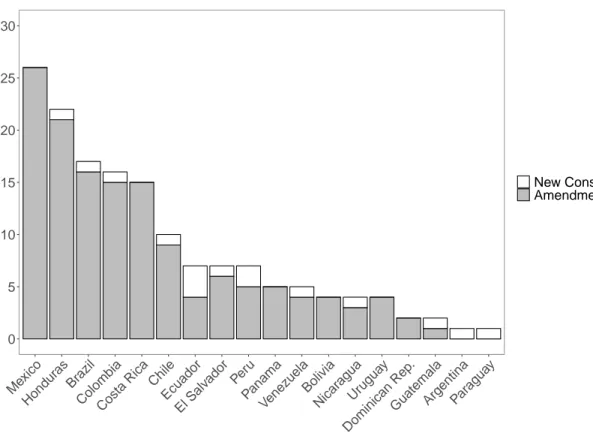

1 Constitutional reforms in Latin America (1978-2008). Note: Data

taken from Negretto (2013). . . 3 1.1 Mean number of lists per district presented by the liberals,

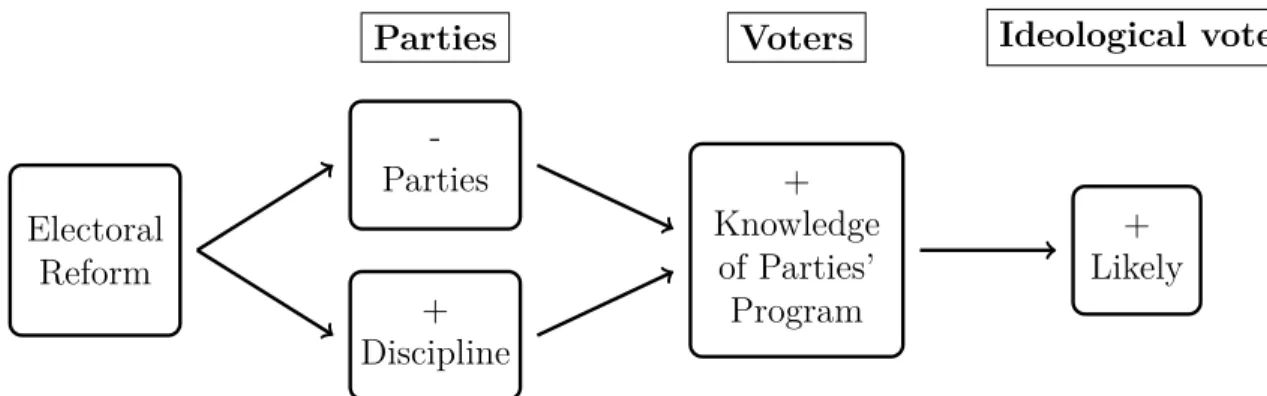

con-servatives, and all other parties, 1958-2002. Note: Trendlines are smoothed using spline interpolation. Data taken from Moreno & Escobar-Lemmon (2008). . . 17 3.1 Summarized expectations regarding the impact of the electoral reform

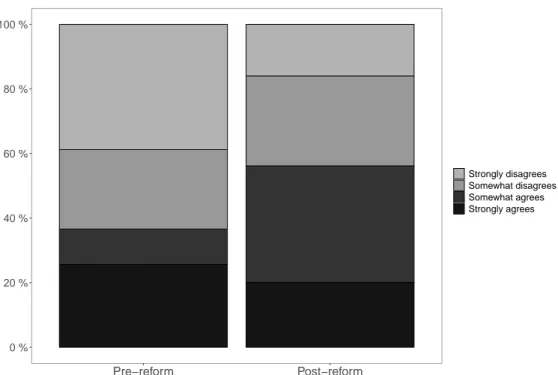

on party behavior and voting behavior. . . 37 3.2 Opinion on expulsion of legislators who fail to respect the party line. 38 3.3 Choice between voting in favor of party or departments’ interests

dur-ing a legislative vote. . . 40 3.4 Expected relation between the number of parties competing in an

elec-tion and the amount of ressources needed to gather informaelec-tion on their program, applied to the Colombian case. Solid line represents known change after the reform, dashed line indicates expected change. 43 3.5 Relation between the amount of ressources needed to gather

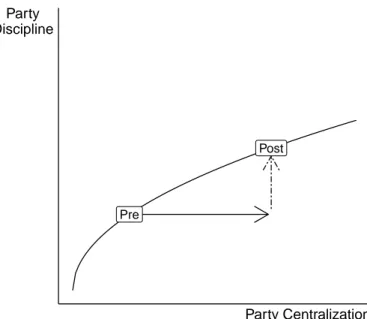

informa-tion on parties’ program and the likelihood of voters expressing an ideological vote, applied to the Colombian case. Solid line represents known change after the reform, dashed line indicates expected change. 44 3.6 Relation between the level of centralization of political parties and

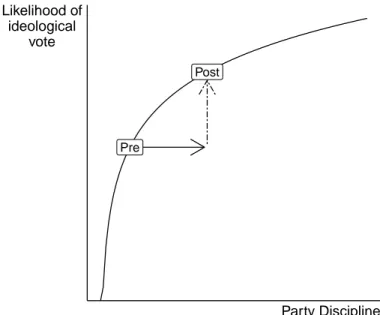

their discipline, applied to the Colombian case. Solid line represents known change after the reform, dashed line indicates expected change. 47 3.7 Relation between the level of party discipline and the likelihood of

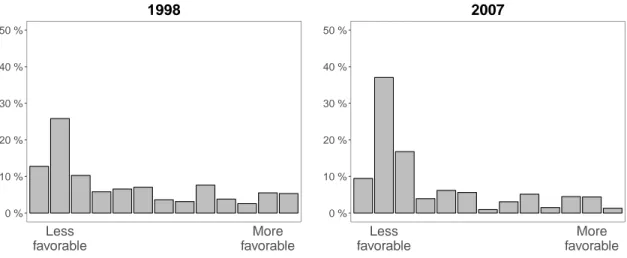

vot-ers expressing an ideological vote, applied to the Colombian case. Solid line represents known change after the reform, dashed line indicates expected change. . . 48 4.1 Bar chart of respondents’ opinion on privatization of various economic

sectors. . . 59 4.2 Bar chart of respondents’ trust in their country’s armed forces. . . 60 4.3 Jittered scatterplot of respondents’ bidimensional ideological position. 61

4.4 Scatterplot of parties’ bi-dimensional ideological position. Note: PL=Partido liberal, PC=Partido conservador, PD=Polo democrático alternativo, PU=Partido social de unidad nacional, CR=Cambio radical. . . 63 4.5 Separable preferences with equal salience. . . 64 4.6 Separable preferences with unequal salience. . . 66 4.7 Most important issue of respondents in pre- and post-reform samples. 67 5.1 Voters’ distance to parties, 1998. . . 71 5.2 Voters’ distance to parties, 2007. . . 71 5.3 Results of regression analyses with 300 random samples. Note: Dots

represent the parameter estimate and standard error of the ideological distance variable for each sample. Both sets of simulations use the squared measure. . . 76 5.4 Barplots presenting the statistical significance of simulations. Note:

The statistical significance threshold is set at the p<0.1 level. Both sets of simulations use the squared measure. . . 77 5 Factorial analysis of variables used to build the economic management

scale among voters, with data taken from the 1998 and 2007 Latino-barometers. . . 85

Remerciements

J’ai eu la chance d’être entouré de plusieurs personnes qui, à divers moments, m’ont appuyé dans la réalisation de ce mémoire et dans la poursuite de mon cheminement académique. Le premier remerciement doit être dirigé vers ma mère, qui m’a toujours encouragé à croire en mes compétences et poursuivre mon parcours académique aussi loin que je le souhaitais. Les innombrables heures qu’elle a investies afin de m’aider à compléter mes devoirs et comprendre la matière que l’on m’enseignait lors de mes premières années à l’école primaire m’ont aidé à avoir confiance en mes capacités et à prendre plaisir à constamment approfondir mes connaissances. Maman, merci pour toutes ces heures passées à mes côtés qui m’ont permis de développer mes aptitutes à comprendre et apprendre.

Ensuite, il est tout naturel de remercier la femme ayant pris le relais au cours des dernières années de ma vie. Lors des périodes les plus difficiles comme des périodes de questionnement, c’est principalement toi, Gabrielle, qui a su m’amener à poser les bonnes questions et maintenir le cap sur l’objectif. Ta confiance inébranlable en mes capacités est contagieuse et je me considère choyé de t’avoir à mes côtés afin de me permettre de devenir un meilleur chercheur, mais aussi une meilleure personne. Merci de toujours me supporter au travers de cette aventure.

Sur le plan académique, j’ai eu l’opportunité de rencontrer plusieurs professeur-e-s et collègues étudiant-e-s ayant contribué à faire de mon passage à l’Université Laval une expérience incroyablement enrichissante. Lorsque je me compare à l’étudiant que j’étais lorsque je suis arrivé au tout début de ma maîtrise, je prend conscience

de l’ampleur du chemin parcouru. Les trois membres de mon jury ont tous joué un rôle important dans ce développement, à commencer par mon directeur de mémoire, François. Je me sens extrêmement privilégié d’avoir eu l’opportunité de trouver un di-recteur m’ayant accordé sa confiance dès notre première rencontre. Tu m’as offert une panoplie de possibilités qui ont contribué à rendre l’expérience de ma maîtrise aussi enrichissante qu’elle l’a étée. Je garderai un souvenir indélébile des premières con-férences académiques auxquelles j’ai pu participer grâce à ton support. Je retiendrai de toi l’accent que tu m’as encouragé à mettre sur le caractère intuitif et simple que devrait avoir la recherche, des éléments que nous tendons fréquemment à perdre de vue. En ce qui a trait aux deux autres membres de mon jury, chacun a contribué non seulement à la réalisation de ce mémoire, mais aussi à mon développement en tant que chercheur. Les conseils de Marc et Yannick ont été particulièrement importants dans la construction du cadre théorique sur lequel s’appuie ce projet, m’ayant permis de débloquer à un moment où j’étais coincé. Aux trois membres de mon comité, merci d’avoir été disponibles afin de répondre à mes questions, de m’avoir offert votre point de vue et de m’avoir permis d’échanger avec vous sur une panoplie de sujets.

Finalement, je souhaite aussi remercier mes collègues de la Chaire de recherche sur la démocratie et les institutions parlementaires et du Groupe de recherche en communication politique. Votre enthousiasme est stimulant et je suis fort heureux de pouvoir compter un groupe d’étudiants aussi talentueux et déterminés parmi mon réseau de collaborateurs. À vous aussi, merci.

Introduction

Can institutional reforms induce predictable changes in the behavior of voters in emerging democracies? Numerous democratic transitions took place around the world during the 1980s, and many countries which took part in such democratization pro-cesses have tried during the following decades to make their democracy extend beyond the mere presence of free and fair elections. They have tried to get rid of undesirable behaviors such as clientelism, patronage, rent-seeking, and charismatic leadership, to replace those with practices better suited to a normative ideal of representative democracy. Most countries looking for a quick fix to such issues have opted for in-stitutional reforms, expecting their impact to be immediate and predictable, thus quickly deepening the quality of their democracy (Negretto, 2013). Yet, it remains unclear whether such speedway to democracy exists, as the impact of electoral in-stitutions on voters’ behavior has been the topic of much debate among scholars of the developing world. Whereas some believe they are universally strong predictors of political behavior, others claim the behavior of voters to be much more significantly determined by contextual factors.

This thesis proposes to contribute to the aforementioned debate by offering origi-nal empirical evidence to assess the explanatory power of neo-institutioorigi-nal theories to account for electoral behavior in new democracies. To do so, the project focuses on the reshaping of electoral institutions, a strategy which has frequently been used to fos-ter desirable political behaviors. Neo-institutional theories suggest that individuals,

whether voters or elites, respond to the incentive structure they are facing. New elec-toral institutions usually put in place new incentive structures, therefore expectedly inducing changes in the political behavior of both voters and elites. Yet, empirical investigations on the topic have found, at best, lukewarm support for such theories when looking at voting behavior in new democracies. This project intends to further explore their validity by utilizing a research design that contrasts with the ones used by most other studies testing neo-institutional theories. Using a before-after research design studying the Colombian case–where an electoral system reform was adopted in 2003–this thesis aims to assess the impact of the reform on the behavior of both parties and voters. The project therefore has the potential to contribute with new empirical evidence to an ongoing debate on the significance of electoral institutions to understand political behavior in emerging democracies.

The case of Colombia could provide strong evidence to our understanding of the predictive capacity of neo-institutional theories to account for voting behavior in new democracies. The 2003 reform on which this thesis focuses was designed to specifically impact party behavior in a way which would make easier for voters to hold them accountable. It would also make easier for voters to keep track of their policy preferences and voting record, making the expression of their own political preferences during elections more likely. The availability of public opinion survey databases conducted among both voters and legislators offers us the opportunity to assess the reach of the reform, most importantly whether it suceeded in impacting party behavior and if such impact, in turn, led to a change in citizens’ voting behavior. The results of this investigation thus have the potential to offer a comprehensive assessment of the reform’s impact, helping us better understand how voters of the developing world react to institutional reforms.

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Me xico Hondur as Brazil

ColombiaCosta Rica Chile Ecuador El Salv ador Per u Panama Venezuela Bolivia Nicar agua Urugua y Dominican Rep .

GuatemalaArgentinaPar agua

y

New Constitution Amendment

Figure 1: Constitutional reforms in Latin America (1978-2008). Note:

Data taken from Negretto (2013).

0.1

Institutional Reforms in Latin America

The practice of institutional engineering has been highly salient in the Latin American region. Frequent regime changes from the begining of the 19th century until the mid-1980s used to entail constitutional rewrites, which often included the restructuring of political institutions. The tendency to frequently modify constitutions, or replace them altogether, has remained a generalized trend in the region since the third wave of democratization, although the rate of changes has slightly decreased (Negretto, 2013). Recent constitutional rewrites are nevertheless of particular significance. In-deed, while constitutional rewrites during the pre-democratic period often signified a regime transition, from authoritarianism to democracy or vice versa, a notable dis-tinction of the recent acts of constitutional engineering is that they do not formalize a regime transition.

Table 1: Institutional reforms in Latin America (1978-2008)

Focus Number of reforms

Number of parties: presidential elections 13

Number of parties: parliamentary elections 32

Vote personalization: parliamentary elections 9

Control of government ministries 10

Legislative powers of presidents 18

Presidential reelection limits 16

Figure 1 presents the number of constitutional changes and constitutional amend-ments in Latin American countries during the 1978-2008 period. Every Latin Amer-ican country has either amended its constitution or adopted a new one during the period, with only four of the 18 countries in the region adopting less than four con-stitutional changes, while five countries modified their constitution at least 15 times. Constitutional engineering has thus remained alive and well even after democracy established itself in the region.

But what has been the focus of such reforms? Significant emphasis has been put on the shape of political institutions, with many reforms implemented in the hope of generating changes in elite behavior which would make them more efficient at solving their country’s problems (Negretto, 2009). Table 1 presents the number and the focus of institutional reforms adopted through the amendment or the replacement of constitutions in Latin America during the 1978-2008 period, with data taken from Negretto (2009).

The table underscores the significance of the reshaping of political institutions across the 18 countries of the region. In some cases, those reforms aimed at modifying the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches. Reforms which

modified the mecanisms of ministerial control, the limits of presidential legislative powers, and presidential reelection limits are of that kind. Other reforms aimed at modifying more directly the behavior of parties and candidates, such as those adopted to restrict or expand the number of parties competing in parliamentary and presidential elections, and those which were designed to impact the personalization of politics. Our investigation is concerned with that latter type of institutional change. From a macro perspective, most of those reforms have had a profound impact on the working of democracy in the countries that implemented them (Negretto, 2013). Many investigations have underscored the ability of institutional designs to influence the number of parties competing for office (Amorim Neto & Cox, 1997; Clark & Golder, 2006; Duverger, 1954; Lijphart & Aitkin, 1994; Samuels, 2000; Taagepera & Shugart, 1989), their internal functioning (Carey & Shugart, 1995; Moreno & Escobar-Lemmon, 2008), the balance of power between branches of government (Linz, 1994; Shugart & Carey, 1992), and the dynamics of inter-branch relations (Helmke, 2017).1 While scholars now tend to agree that the strength of the impact of political institutions on a given country’s politics is conditional upon the presence of reinforcing or alleviating contextual factors (Morgenstern & Vázquez-D’Elía, 2007), few challenge their impact altogether (see Hagopian, 2007 for a survey of the literature challenging the predictive capacity of neo-institutional theories). The debates revolve mostly around the strength and the boundaries of the impact of institutions on macro-level units such as parties and government branches.

Scholars who investigated the impact of electoral institutions on citizen voting patterns have for their part reached more mitigated conclusions. While we do have a significant body of evidence indicating that institutions can change the way parties

1It is noteworthy to underscore that authors who provided empirical evidence supporting the

argument in favor of the impact of institutional designs on the shape of a country’s political compe-tition (i.e. the number of parties, party discipline, vote-seeking strategies) have claimed institutions to have a contributory impact, rather than the deterministic impact expected by many earlier works on the topic (for a survey of the relation between institutions and party systems, see Morgenstern & Vázquez-D’Elía, 2007).

behave, it is unclear how such impact translates into voters’ behavior during elections. Yet, a significant theoretical literature on electoral behavior claims that different vote aggregation mechanisms should lead to different voting patterns if we assume citizens to be utility-maximizing voters and, therefore, vote strategically (Amorim Neto & Cox, 1997; Duverger, 1954). Such impact of electoral rules on voting behavior is known as Duverger’s “psychological effect”: expecting the mechanical effects of elec-toral rules on party representation, citizens modify their voting pattern to maximize the value of their vote (Benoit, 2002).

That said, many scholars interested in electoral behavior in the developing world have underscored the empirical limits and contradictions of the neo-institutional ap-proach, claiming that the impact of institutions on political behavior are not au-tomatic, let alone predictable (Hagopian, 2007; Taylor-Robinson, 2006; Weyland, 2002). The most consistent critiques have come from authors who contend that neo-institutional theories oversimplify human behavior by merely looking at short-term factors, which they believe to have very little impact on voters.2 They incidentally argue that institutions exert only a limited–albeit progressive–influence, whereas so-cialization and modernization processes exert a much stronger and enduring influence on individual decision-making processes. Put simply, they acknowledge that institu-tional structures exert an impact on individual behavior, but they believe such influ-ence to develop over time, rather than instantaneously, and also claim that it can be countered or lessened by the social context.

Their argument carries significant implications for the developing world, where so-cial norms and attitudes often contrast with those of established democracies (Almond & Verba, 1963; Inglehart, 1997; Lipset, 1959), scarce material resources make voters less likely to gamble on long-term policies (Kitschelt & Wilkinson, 2007a; Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno, & Brusco, 2013),3 and informal institutions frequently blur the

2For an overview of the debate, see Norris (2004).

expected impact of formal institutions (Helmke & Levitsky, 2006). Those are all fac-tors which could cancel, or at least weaken the predicted impact of formal institutions on political behavior in new democracies.

In line with modernization theories, many scholars claim social experiences to have the most important explanatory power regarding political behavior in the Latin American region. Looking at the determinants of party system structuration during the late 1990s, Kitschelt, Hawkins, Luna, Rosas, & Zechmeister (2010) find historical patterns of social contestation over economic policies to be the main forces driving party system structuration. They do not find any evidence suggesting that institu-tional structures have impacted partisan cleavages. In a similar framework, Kenneth Roberts claims the neoliberal turn in the region during the 1980s and 1990s to have constituted a critical juncture which reshaped socioeconomic cleavages among citizens (Roberts, 2013, 2015). According to his argument, such reshaping of social cleavages then brought about a realignment or, in a few cases, a total reformation of existing party systems. Such works exemplify the argument of scholars presenting political experiences to be at the core of voters and parties’ behavior in the developing world.

Modernization theories also find support in the results of other investigations aiming to measure the impact of institutions on political behavior in Latin Amer-ica. Studying the Colombian case, Dargent & Muñoz (2011) stress the limits of institutional reforms adopted in 1991 and 2003, claiming they only affected partisan coordination strategies during elections and did not impact the degree of represen-tativeness of the parties. Turning to Honduras, Taylor-Robinson (2006) finds that an institutional reform even led parties to adopt strategies which ran counter to its expected impact. Many scholars therefore claim neo-institutional theories to have a weak explanatory power in emerging democracies, further arguing that their impact

of income is higher among the poor than the rich. More generally understood, the argument implies that the poorer a voter is, the less likely s/he is to gamble on policies whose benefits are potentially greater but also more uncertain.

might simply be conditional upon their interaction with favorable sociohistorical con-texts (Hagopian, 2007; Morgenstern & Vázquez-D’Elía, 2007).

A broad overview of the literature on the capacity of neo-institutional theories to account for political behavior in the developing world thus provides an unclear picture. Some very compelling positive results have been found, but they are met with numerous more skeptical works putting forward the cultural differences between consolidated and emerging democracies to explain why the literature on the latter context struggles to replicate the findings of authors interested in older democracies. Moreover, much less is known about the impact of institutions on the behavior of voters. Very little attention has been paid to the way voters react to changes among elite behavior after institutional reforms. This thesis aims to tackle this lack of evidence on the topic by measuring how the Colombian institutional reform of 2003 impacted voting behavior, and discuss the broader implications of such findings for the study of electoral behavior in emerging democracies.

From a more applied perspective, the lack of evidence supporting the impact of in-stitutional structures on electoral behavior questions the relevance of the widespread practice of institutional engineering in new democracies. The matter could prove especially significant for the Latin American region, where a significant amount of ressources are invested in frequent constitutional rewrites which often involve institu-tional changes. To enact such changes, governments usually form large Constituinstitu-tional Assemblies which are invested with the responsibility of rewritting their country’s constitution. A significant amount of public ressources is therefore invested in such processes, which usually last numerous months. Although other factors such as in-stitutional stability certainly matter in the implementation of electoral reforms, it appears reasonable to look not only at institutional actors, but also at voters to better understand the full range of implications of those endeavors.

0.2

Research Question

Neo-institutional theories are unequivocal: not only are electoral institutions powerful determinants of political behavior in any social context, but their effects are also predictable (Duverger, 1954; Rae, 1967; Taagepera & Shugart, 1989). Yet, empirical findings regarding the capacity of neo-institutional theories to account for political behavior in the developing world are mixed. While a solid body of works suggests that institutions have an impact on partisan behavior in certain contexts, very few scholars have paid attention to the way in which voters react to the changes in elite behavior fostered by institutional engineering.

The traditional cross-country transversal research designs frequently used in em-pirical assessments of neo-institutional theories might not be optimal to answer the research question this thesis is interested in. Such designs are fruitful to find gen-eral patterns but lack the precision which might be necessary to assess the impact of electoral changes among voters. Keeping in mind the caveats of scholars critical of neo-institutional theories, we believe that a cross-country design would not allow us the flexibility needed to take into account the contextual idiosyncrasies of the Colombian case. Focusing on a single country thus allows this thesis to take into consideration such factors to build context-specific empirical tests. Moreover, relying on a before-after design, the analysis will be based on reliable and comparable esti-mates of voting behavior before and after the threatment of interest–the institutional reform–to precisely measure its impact, if any.

Theoretically, we have opted to rely on the proximity version of the spatial voting model to conduct our analysis. The spatial model has the significant advantage of valuing parsimony and simplicity, which makes it applicable in any voting context (whether electoral or not). In an electoral context, it simply posits that citizens should vote for the party whose stance is closest to their own. It is incidentally highly intuitive and fairly simple to apply in any political context. Moreover, its parsimony

allows us great flexibility to adapt its implementation to our contextual understanding of the Colombian case, hence allowing us to make sure that our empirical investigation is precisely built while also making sure that it lies on a solid theoretical foundation.

The objectives of the reform reinforce the relevance of the spatial model to answer our research question. During the 1990s until the 2002 election, the Colombian party system grew ever more chaotic. After the latter election, the Liberal party won the most seats, with 54 out of the 166 total seats in the Chamber of representatives. The second largest party was the Conservatives, which controlled 21 of the 166 seats. The 91 seats remaining (55% of the total) were shared among 60 parties or coalitions, most of them competing in sole or a very limited range of districts. The Colombian party system had thus become very fragmented, the flurry of parties competing making it hard for voters to develop a clear understanding of their ideological stance. The reform was adopted to decrease the amount of microparties competing in specific areas of the country and force their aggregation into a few larger parties on which voters could more easily gather information. Such simplified information-gathering process should make easier for voters to support parties sharing their ideological stance, as it would become more simple to understand parties’ stance and relate it their own, hence the use of the proximity spatial model.

0.3

Case Selection: Colombia and the Quest for

Order

The electoral reform which Colombia underwent in 2003 did not fundamentally change its electoral institutions. The seat-allocation formula remained a proportional one, the legislature remained bicameral, and most importantly, presidentialism was main-tained. The changes which were put in place were, in fact, rather minor, but their impact should be both straightforward and predictable. Furthermore, investigating

minor institutional changes avoids this thesis the hazardous task of disentangling what specific institutional modification led to a given behavioral change and infering about how would have voters reacted if only some elements of the reform had been implemented.

The three most important modifications enacted through the reform were: 1) the replacement of the previous simple quota largest remainder (SQLR) seat-allocation formula by a D’Hondt method; 2) the adoption of a 2% of the national vote threshold necessary for parties to reach to be included in the seat distribution process; and 3) the implementation of a rule forcing parties to present a single electoral list in each district, as opposed to the previously unlimited amount they could present.

While somewhat minor, those changes were designed–and succeeded to–foster sig-nificant changes in the Colombian party system. Mainly, the reformers had in mind to restrict the amount of parties obtaining legislative representation to make easier for voters to hold their representatives accountable (Botero & Rodríguez Raga, 2009; Mejía Guinand, Botero, & Rodríguez Raga, 2008). The disappearance of most micro-parties is also significant as such micro-parties usually developed personalized linkages with their electorate, paying little attention to programmatic matters (Dargent & Muñoz, 2011; Pizarro, 2002; Rodríguez Raga, 1998, 2002). Cleared from its micro-parties, the Colombian party system was expected to become much more centered on program-matic issues put forward by the larger parties, as keeping track of 4-5 party programs should be significantly easier than keeping track of dozens of programs.

The 2003 electoral reform thus constitutes a quasi-experiment in testing the im-pact of electoral institutions on electoral behavior, as it created a discontinuity which changed the Colombian party system from highly unamenable to ideological party-voter linkages to a system expectedly much more favorable to it. An investigation of the case thus has the potential to complement the various other studies which have tried to assess the impact of institutional engineering on political behavior using

cross-sectional designs. While contributing to the scientific understanding of such re-lationship, this thesis also has potentially very practical implications, as it could shed light on the efficacy of a very common practice among democracies of the developing world.

0.4

Thesis Overview

The five chapters of this thesis proceed as follow. We start by providing details on the Colombian case to justify its use to answer our research question and provide the contextual details that will prove determinant in our analysis. We then move on to a thorough presentation of our theoretical framework. We separate the latter section into, first, a description of the relationship between ideology and voting be-havior, and then present the neo-institutional theories which lay the foundation of our theoretical expectations. In Chapter 3, we make a precise description of such ex-pectations by connecting our theoretical framework to the Colombian context. The next chapter then presents and justifies the method we employ to identify voters’ and parties’ ideological stance, and how we estimate the impact of such stances on voting behavior. Chapter 5 presents the results of the empirical analysis, while the conclusion summarizes the findings and discusses their broader implications.

Chapter 1

The Colombian Case

Colombia has been relatively priviledged compared to most of its Latin American neighbours. The union of the Conservative and Liberal parties against the military dictatorship in 1957, in what came to be known as the National Front, led Colombia back on the path to democracy which was established anew in the following year. Since then, elections have remained free and rather fair, although the two dominant parties relied heavily on clientelistic appeals to maintain their hegemony over Colom-bian politics (Archer, 1995; Archer & Shugart, 1997; Martz, 1997). Nevertheless, Colombia’s political fate shines bright in comparison to that of most of its neighbors, that had to wait until the 1980s to see democracy take root.

Yet, although Colombia is democratic since the middle of the 20th century, its institutions have been molded in a variety of ways. Indeed, Colombia has been a fertile field of experiment for advocates of institutional engineering. The processes of electoral reforms are rooted in the democratic transition that Colombia underwent in 1958, which was established with both hegemonic parties signing the National Front Pact to end the dictatorship of General Rojas Pinilla (1954-1958). The agreement specified that elected positions and public offices would be evenly split between both parties for a period of four presidential terms (Hartlyn, 1988). The garanteed access

to public resources allowed parties to develop strong clientelistic appeals, which gener-ated a growing discontent among the electorate (Dargent & Muñoz, 2011). The long series of electoral reform thus started with the replacement of the partisan ballot by a universal ballot in 1988. Encouraged by its successful pressures for electoral reforms, the Colombian civil society demanded further reforms to open the partisan system to new social and political forces. Such demands culminated in the 1991 constitutional reform, in which many fiscal and decentralization reforms were implemented to reduce the power of the two dominant parties.

The 1991 reform having set the table for a significant reshaping of the Colombian party system, some features of the new political system came to be seen with criti-cism among the Colombian electorate and some elected officials. Incidentally, another significant reform was implemented in 2003, with the goal of putting in order Colom-bia’s chaotic party system to make parties more accountable to voters. The latter institutional change has significantly modified the Colombian party system, creating an environment which appears likely to have made policy orientations a more signifi-cant determinant of party and voting behavior. Indeed, the changes put in place and the impact they have had on the party system should have made significantly easier for parties to develop credible policy-commitment appeals and for voters to gather information on parties’ policy orientations.

This thesis thus focuses on the 2003 electoral reform to better understand its impact on Colombian voting behavior. Its analysis is informed by evidence previously collected in other works regarding the 2003 electoral reform’s impact at the macro-level (i.e., on the party system), which leads us to expect a concomitant change to have occurred at the micro-level (i.e., among voters’ behavior). The various investigations of the reform’s impact on the Colombian party system all reach the conclusion that the reform drastically changed the face of Colombian elections. Indeed, many have argued that the 2003 electoral reform created a significant disruption which lead to

profound, and enduring changes in party competition (Batlle & Puyana, 2011). The Colombian case thus promises to be very informative regarding the reach of electoral reforms, as it constitutes a natural experiment in which a party system has been drastically–albeit indirectly–modified, offering us the opportunity to test whether the impact on voting behavior of the change among party competition corresponds to that predicted by neo-institutional theories.

While Colombia has a presidential system, the reform strictly targeted legislative elections. Parliamentary elections being held six weeks before presidential elections, the time difference between the two events allows us to study legislative elections in isolation from presidential elections. Simply put, even if the reform did, in some way, impact presidential campaigns, their occurrence more than a month after legislative elections allows us to rest assured that our results will not be impacted by any kind of possible cross-over effects between the two contests. This specificity of the Colombian political system further reinforces the quasi-experimental character of our case, as we are strictly looking at the impact of an institutional change on legislative elections rather than all elections, expectedly reducing the noise in the results of our analysis.

1.1

Colombian Elections Before the Reform

Electoral competition in emerging democracies is often characterized by clientelism, patronage, and various other forms of contingent distributive politics. Colombia is no exception, as clientelism was prevalent during most elections held in the country, channeled trough its two hegemonic parties, the liberals and the conservatives, which ruled elections since the 19th century (Archer, 1995; Archer & Shugart, 1997; Martz, 1997). But as far as national elections go, that story is now part of the past. The adop-tion of a new constituadop-tion in 1991 decentralized the control of an important amount of state resources to lower-level governments, therefore considerably amputating the

capacity of national politicians to engage in clientelistic appeals (Dargent & Muñoz, 2011). Since then, we do not have any indications that contingent distributive politics of any kind still play a significant role in national elections.

Elections that occured after the 1991 reform nevertheless remained far removed from a normative ideal of representative democracy. The 1991 electoral reform, adopted through a new constitution, had as its main objective to break the two-party hegemony which had started in the 19th century and was facing a growing legitimacy crisis (Dargent & Muñoz, 2011). To open the Colombian party system to new parties representative of various social forces, registration laws were drastically relaxed, in the hope of breaking the electoral monopoly of the two dominant parties (Batlle & Puyana, 2011, 2013).

The reform succeeded at opening the Colombian party system to new social forces. In fact, it succeeded to such an extent that it quickly became problematic, as the number of lists presented by parties other than the liberals and the conservatives quickly got out of control. Figure 1.1 presents the evolution during the latter half of the 20th century of the mean number of lists per district presented by the liberals, the conservatives, and all other parties. As made explicit by the figure, the number of lists presented by non-traditional parties quickly exploded, jumping from an average of two or three lists per district before the reform to an overwhelming mean of 16 lists in the 2002 election.

Incidentally, the mere number of lists every voter had to choose from in elections held during the 1991-2002 period seriously hampered the possibility for voters to make a well-informed choice. Yet, the manner in which parties were competing and trying to form bonds with their electorate created a further discrepancy between the way elections were held in Colombia and the way elections should be held according to a normative ideal of representative democracy. Indeed, a significant amount of parties were considered to be “political micro-entreprises”, as they where merely

po-1991 ref or m 0 5 10 15 1958 1962 1966 1970 1974 1978 1982 1986 1990 1994 1998 2002 Lists Parties Liberals Conservatives Others

Figure 1.1: Mean number of lists per district presented by the

liber-als, conservatives, and all other parties, 1958-2002. Note: Trendlines are smoothed using spline interpolation. Data taken from Moreno & Escobar-Lemmon (2008).

litical vehicules allowing regional barons to compete in elections without presenting a clearly defined program, instead relying on personal ties with their constituents to run their campaign (Dargent & Muñoz, 2011; Pizarro, 2002; Rodríguez Raga, 1998, 2002). Many of those parties, especially in the 1998 and 2002 elections, succeeded at obtaining a seat in the Chamber of representatives, thus effectively obtaining a mandate to represent their constituents without having presented a clearly defined set of policy orientations. Their success culminated during the 2002 election, in which they captured nearly half of the seats in the Chamber of deputies.1

Another significant issue across the period relates to party unity. Party leaders had very weak control over their candidates, making them unable to force discipline around

1They had an almost identical success in senatorial elections, which are not discussed here as this

party lines. Parties were highly factionalized, with every faction presenting its own list and running its own campaign without any significant constraint imposed by party leaders (Moreno, 2005; Moreno & Escobar-Lemmon, 2008). In such environment in which party labels didn’t carry any specific implication, party-switching was frequent between electoral contests.

In sum, two major issues contributed to make uneasy for voters to hold their representatives accountable: the high number of electoral lists presented in every district, and the factionalization of parties. Those two issues made voters unlikely to gain information on the policy preferences of the different lists competing in their district. Furthermore, the factionalization of parties made policy implementation during legislatures unpredictable, as parties were not forced to follow a common line, their many factions voting disjointly on the various bills which were proposed.

1.2

The 2003 Electoral Reform

To rationalize their party system, Colombian legislators adopted an electoral reform in 2003. The main declared objective of the reform was to strengthen the major parties at the expense of the microparties, so as to facilitate electoral accountability.2 To do so, the reformers decided to redesign the rules governing the seat-allocation process.

The first significant change concerns the electoral lists presented by parties. Before 2003, Colombia had a proportional voting system with open party lists.3 Parties could present an unlimited number of lists in each district, and the two major parties developped a strategy known as operación avispa, where they would try to drown their minor opponents by presenting multiple lists in each district (often up to 7 or

2For the complete official definition and explanation of the reform, see http://www.

congresovisible.org/democracia/reformas/2003/.

3The deputies were elected in 33 electoral districts with a magnitude ranging from 2 to 18, with

8).4 Figure 1.1 shows that the strategy was most importantly used by the liberals. As seats were allocated on the basis of a simple-quota largest remainder (SQLR) formula, such tactic allowed the two major parties to have multiple lists meeting the quota requirement to obtain seats through the first distribution stage, and also have multiple lists competing for seats in the second distribution stage, in which seats are allocated to the lists with the largest remainder of votes when no more list meats the quota.5

The latter tactic was no longer possible after 2003. Since the adoption of the electoral reform, parties are now forced to present a single electoral list in every district, substantially simplifying voters’ information-gathering process. Parties have been left with the opportunity to choose between open or closed lists, but most parties have opted to keep their lists open.

The second important change implemented by the reform concerns the revision of the seat-allocation formula. The SQLR method’s second distribution stage was deemed too favorable to small parties and thus considered to have facilitated the fragmentation of the Chamber of deputies through the development of microparties (Pachón & Shugart, 2010).6 A D’Hondt allocation formula was therefore adopted,

considered to be more favorable to large parties. To further restrict the representation of micro-parties, the reform also established a threshold of 2% of the national vote necessary to reach for parties to be included in the seat allocation process for the Chamber of deputies.7 Incidentally, while the electoral formula remained proportional, it was designed to favor a much more moderate form of multipartyism.

The most straightforward objective of the reform was therefore to force the

ag-4For more details on the electoral strategies of parties before the 2003 reform, see Moreno &

Escobar-Lemmon (2008).

5Presenting multiple lists also provided a way for parties not to choose between different

fac-tions internally competing one another, but this notion is out-of-bounds considering our research objectives. Again, for more details, see Moreno & Escobar-Lemmon (2008).

6Although we limit the scope of our research to the Chamber of deputies, it is worth noting that

the same argument applied to the also very fragmented pre-2003 Senate.

gregation of the vast amount of micro-parties that had emerged into a few major parties which could more easily be held accountable by voters (Botero & Rodríguez Raga, 2009; Mejía Guinand et al., 2008). The reform did succeed to concentrate the partisan representation in a few major parties, effectively wiping out the bulk of micro-parties during the 2006 and 2010 elections (Batlle & Puyana, 2011; Pachón & Shugart, 2010; Rodríguez Raga & Botero, 2006). Following the traditional downsian logic (Downs, 1957), acquiring information on voting alternatives (i.e., parties in our case) is costly, and we can expect that, ceteris paribus, the higher the number of parties, the most resources-extensive it is for voters to develop a clear understanding of parties’ programs. Incidentally, the decrease in the number of parties competing for seats can be expected to have made voters’ information-gathering process signifi-cantly less costly, possibly helping them to develop a clearer knowledge of their stated policy preferences and voting record in Parliament.

The second important objective of the reform, much less straightforward to sub-stantiate, was to foster greater intra-party coherence regarding policy orientations, so as to clarify the ideological boundaries between parties that would survive the reform. Once again, this feature of the reform aimed to make easier for voters to hold parties accountable during elections, as the multiple amount of lists presented by every party was perceived to have favored the personalization of politics (Moreno & Escobar-Lemmon, 2008). To foster greater party discipline, designers of the reform wished to increase the leverage of party leaders on their representatives to offer them the capacity to impose a united party line to their candidates/deputies (Dargent & Muñoz, 2011). The limit of a single list per party in every district thus contrasts heavily with the pre-reform situation, where parties had little control over who used their label, leading to a situation in which most parties presented multiple lists in every district but rarely had more than a single candidate elected from one of their lists (Botero & Rennó, 2007). Parties now having to select a limited number of

candi-dates in every district–the number of candicandi-dates on the lists had been limited to the number of seats at stake in the district–reformers expected party leaders to benefit from a greater capacity to impose discipline on their candidates. In addition, the elimination of micro-parties was expected to remove the option for party represen-tatives to opt out of their party and form their own partisan vehicule, which could create a reinforcing pattern of representatives staying with their party rather than exiting it (Hirschman, 1970), effectively raising the power of party leaders among their troups while simultaneously increasing the distinctiveness of each party among its competitors.

Greater party discipline should have made it easier for parties to develop credible policy-commitment appeals, as policy commitments can accordingly be expected to have become more easily enforceable upon party representatives. Such change could be expected to have further simplified voters’ information-gathering process regarding parties’ policy preferences, thus lowering the threshold of political knowledge neces-sary for voters to issue a vote on such matters. While debates remain regarding the reform’s success in increasing ideological coherence among parties, Rodríguez Raga & Botero (2006) did find evidence of greater intra-party unity after the reform.8

In summary, the Colombian electoral reform of 2003 should have put in place conditions facilitating the expression of an ideological vote. The personalization of politics prevailing before the reform is expected to have significantly decreased, as micro-parties have effectively been eliminated from political competition and major parties should now have a greater leverage on their representatives to impose a united party line. Collecting information on parties’ stated policy preferences and voting record in Parliement should thus have become significantly easier, which is in turn expected to have lowered the threshold of political knowledge necessary for citizens to vote according to their ideological stance. All considered, the Colombian case

represents a most-likely case of success for neo-institutional theories to prove their explanatory power among emerging democracies.

Chapter 2

Theoretical Framework

The expression of political preferences through voting behavior has been investigated in a wide variety of ways. Relying on different conceptual operationalizations and the-oretical models, authors have studied it under different labels. One who surveys the scholarship on the impact of political preferences on the vote will encounter various strands of literature which have been developed in parallel and hardly engage with one another. Spatial voting, issue voting, positional voting, or positional issue voting are among the many strands of literature which have assessed the relationship be-tween political preferences and voting behavior, each relying on more or less distinct conceptual definitions.

Yet, before scholars started to work on this specific relationship, the foundational models of voting behavior developed in the American context had paid it little at-tention. Both the pioneering Columbia and Michigan models considered political preferences to be unlikely to significantly impact voters’ behavior during elections (Campbell, Converse, Miller, & Stokes, 1960; Lazarsfeld, Berelson, & Gaudet, 1948). While the Columbia school claimed voting behavior to be first and foremost deter-mined by citizens’ social identity, the Michigan school rather put party identification at the core of its integrated theory of the vote.

In parallel, scholars working in a more Economics-oriented perspective developed the spatial voting theory. As opposed to the former voting models, the spatial model not only presents political preferences as significant determinants of voting behav-ior, but even makes the assumption that they are the main determinants of voters’ electoral choice. The pioneering works can be attributed to Downs (1957) and Black (1958), who formalized the idea of a unidimensional axis to represent political

com-petition and developed the median voter theorem.1 Their work has been met with theoretical and empirical criticisms, on which many scholars working in the rational choice framework have responded either by adapting the original spatial model to its empirical shortcomings or clarifying its theoretical interpretation (see Hinich & Munger (1997) for a survey of spatial models of politics and their responses to the most common criticisms).

More than half a century after its initial introduction to the study of political competition, the spatial model has now become a common analytical tool for po-litical scientists looking to adress the relationship between ideological orientations and voting behavior. We have thus decided to rely on the spatial theory to answer our research question as it is designed to assess the particular relationship we are interested in and is built in such a manner that favors its application in a wide va-riety of contexts. Indeed, the various developments which have extended the basic downsian spatial model throughout the years offer a sophisticated array of analyti-cal tools to precisely measure the way in which ideology conditions voting behavior. Furthermore, the emphasis of spatial models on the parsimony of their theoretical constructions makes them well-suited to be applied in a wide array of contexts, from older western democracies to newer, developing democracies of the south.

1It is noteworthy to mention that the spatial model presented by Downs and Black is an

adap-tation to political competition of Hotelling’s spatial model of competition between firms (Hotelling, 1929).

2.1

Ideology and the Vote

2.1.1

Normative Considerations

From a normative standpoint, the expression of political preferences through the vote has been presented by many as highly desirable as it is a demonstration of political sophistication which carries significant implications (Ames, Baker, & Renno, 2008; Baker & Greene, 2015; Brusco, Nazareno, & Stokes, 2004). Indeed, for citizens to vote in such way, they need to discount factors that are unrelevant to policy-making capacities and instead focus on identifying the candidate who best represents their policy preferences. They incidentally discard many heuristics commonly used to eval-uate candidates but that are unrelated to policy orientations such as ethnicity, gender, physical traits, charisma, and so on. While some authors have argued in favor of the relevance of such heuristics to help voters palliate to their lack of information (Pop-kin, 1991; Sniderman, Brody, & Tetlock, 1993), more recent works in both political science and psychology have shown skepticism regarding the usefulness of heuristics to orient vote choice (Dancey & Sheagley, 2013; Fiske & Taylor, 2008; Kuklinski & Quirk, 2000; Lau & Redlawsk, 2001). Paying more attention to directly relevant fac-tors such as issue stances and policy propositions should thus help voters emancipate themselves from the use of heuristics and can better help them identify the candidate most likely to closely represent their political views.

Moreover, for citizens to vote according to their policy preferences, they need to be confident that legislators will respect their campaign’s policy commitments. If legislators fail to do so, voters are expected to discount candidates’ stated policy preferences during future campaigns, thus effectively wiping out the impact of policy orientations on the vote (Stokes, 2001). Hence, citizens only vote according to their policy preferences if parties respect their policy commitments, which further enhances its normative appeal.

Finally, if voters condition their electoral choice on policy preferences, it forces office-seeking parties and candidates to be responsive to voters’ preferences (Downs, 1957). Recent investigations have shown that parties and governments do respond to citizen preferences in established democracies of the western world (Burstein, 2003; Spoon & Klüver, 2014; Stimson, MacKuen, & Erikson, 1995). Democracy incidentally becomes much more responsive from a macro perspective, as it revolves around the representation of voters’ preferences rather than mere performance on consensual issues, as in valence issue voting. Voters are offered a wider array of political choices than candidates who merely all commit themselves to reaching the same goals, hence directly involving voters in the process of selecting their country’s policy orientations.

Many have claimed that government and party system responsiveness to citizen preferences is a key component of democracy (Dahl, 1971; Huber & Powell, 1994; Pow-ell, 2000). Their claim underscores the significance of the challenge to which are con-fronted most emerging democracies: the establishement of not only well-performing, but also responsive government. Investigating the topic in the Latin American con-text, Stokes (2001) finds that governments of the region are prone to policy-switching, i.e. adopting different policies once in office than those advocated during electoral cam-paigns. A vicious circle is then created, as voters discard the policy orientations of parties when making their vote choice since they do not believe in their commitments, which further reinforces the incentives for parties to discard their campaign promises once in office. The usual claim–first laid out by Ferejohn (1986)–that governments respond to their electorate’s demand to avoid being removed from office in the next electoral cycle, incidentally does not hold in such contexts. The burden of institu-tional reforms is thus enormous, as they are put in place to foster certain desirable behaviors–in our case, ideological voting–in contexts in which such behaviors have hardly (if ever) occurred on a regular basis.

2.1.2

Political Sophistication and the Coherence of Ideology

While the possibility that political preferences might determine voters’ electoral be-havior appears highly desirable from a normative standpoint, most scholars have long been skeptical of voters’ capacity to base their electoral choice on such rationale. Both the authors of the Columbia and the Michigan voting model–the first to establish a unified voting theory–have argued against the relevance of policy preferences. The pioneering authors of both models have mostly presented policy orientations as being irrelevant to account for vote choice, and have instead focused on group identifications as conditioning voters’ choice. While the Columbia school presents voters as mostly influenced by their sociodemographic characteristics (Berelson, Lazarsfeld, McPhee, & McPhee, 1954; Lazarsfeld et al., 1948), the Michigan school presents electoral be-havior as being primarily determined by the party identification of voters (Campbell et al., 1960). Hence, although both models present different characteristics as being critical in accounting for vote choice, their proponents nevertheless agree on leav-ing little space for individual decision-makleav-ing processes, as their electoral choice is expected to be largely pre-determined by social or political identifications.

Many have also argued that citizens lack the necessary levels of political sophis-tication to vote on such complex matters as policy preferences. In his seminal work, Converse (1964) showed compelling evidence suggesting that most citizens lack a co-herent ideological structure in their political preferences. The author later claimed the bulk of voters to form such preferences randomly (Converse, 1970). Converse’s findings being successfully replicated by others (Butler & Stokes, 1975; Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996), a long strand of work presenting most voters as relying on little political sophistication has florished. Zaller (1992) refined Converse’s argument by claiming that citizens’ preferences echo that of the political elites. The literature on political sophistication makes a clear distinction between the elites, expected to have high levels of political knowledge and sophisticated reasoning patterns, and the

masses, presentend as weakly informed and unable to have coherent preferences of their own regarding policy orientations.

Considering the purported lack of coherence in the formation of political prefer-ences among the bulk of voters, those preferprefer-ences appear very unlikely to significantly condition the electoral choice of most citizens. Yet, recent developments in the lit-erature, especially regarding attitude measurement techniques, have contributed to challenge the pessimistic stance which prevailed until recently. Achen (1975) was the first to challenge Converse’s conclusion. Relying on psychological theories of individual choice, the former analyzed the latter’s data by taking into account the probabilistic nature of respondents’ answers and inadequacies of survey designs. He reversed the blamed and argued that the lack of ideological constraint that Converse observed was partly due to the unreliability of the survey questions he used, thus drawing a less skeptical depiction of voters’ political preferences.

Ansolabehere, Rodden, & Snyder (2008) recently offered new evidence supporting Achen’s claim. They showed that including multiple questions to measure respon-dents’ political preferences on an issue substantially increases their internal coherence. Using measurement scale indices to measure the impact of voters’ political preferences on electoral behavior, they find that the impact of such preferences on vote choice has so far been dramatically underestimated. Their findings incidentally run counter to those of Converse (1964) and Zaller (1992), who present the political preferences of voters to be largely irrelavant, a view which has been dominant among scholars of electoral behavior during the last decades. Recent advances in our understanding of measurement techniques have incidentally fostered a newfound optimism regard-ing the capacity of voters to have a coherent ideological structure, which leads us to believe that political preferences could possibly be more significant determinants of vote choice than most had previously thought.

2.1.3

Ideology and Voting in New Democracies

The skepticism toward voters’ capacity to vote according to their ideological prefer-ences has been even greater among scholars of electoral behavior in new democracies. The reasons for such skepticism are both structural and individual. On the structural side, party systems tend to be characterized by high levels of volatility, making it hard for voters to gain a clear understanding of their policy preferences as they often have to choose between recently founded parties on which they do not have much in-formation (Scully, 1995). Party systems have also been claimed to be inchoate, most parties hardly differing from each other on a wide variety of issues, making policy preferences appear to be unrelevant to account for parties’ linkage strategies with voters (Kitschelt et al., 2010). Moreover, many parties have adopted bait-and-switch tactics, thus suggesting that parties’ policy commitments are not credible and can-not be taken into consideration in voters’ electoral decision-making process (Stokes, 2001).

Turning to individual factors, voters in the developing world are often claimed to rely on low levels of political sophistication, possibly making it hard for them to develop a clear position on the many complex matters which enter the political agenda (Grönlund & Milner, 2006). Low amount of material ressources also make them less likely to gamble on innovative policies or favor projects whose benefits could take a few years to materialize, making them more short-sighted when considering policy proposals (Kitschelt & Wilkinson, 2007b). All such factors have led scholars to be highly skeptical not only about the possibility of policy preferences conditioning electoral behavior in new democracies, but also about the likelihood that voters form such preferences by relying on a coherent ideological structure.

Yet, recent investigations have challenged the assumption. Studying Latin Amer-ica’s left wave during the early 2000s, Baker & Greene (2011) have found evidence suggesting voters’ policy preferences to account for the phenomenon. Broadening

their scope to all of Latin America, they have also found similar evidence indicat-ing positional votindicat-ing to have occured on a variety of economic issues durindicat-ing the 21st century, echoing the claim made by Ansolabehere et al. (2008) that attitudes and preferences might simply have been inappropriately measured (Baker & Greene, 2015). Also lending optimism to the posibility that ideological voting might occur in Latin America is an investigation of the 2000 presidential election in Mexico, in which voters were found to have made policy-based voting choices when they perceived the position of candidates to differ (Zechmeister, 2008). This latter finding complements those of Baker and Greene by suggesting that the main challenge to the expression of policy preferences through electoral behavior in emerging democracies might not be individual capacities but rather party system structuration and the voting strategies it makes available to voters.

The study of the impact of political preferences on voting behavior in the de-veloping world thus took a trajectory quite similar to that of scholarly work on the topic in the context of older democracies. Initially met with heavy skepticism, the possibility that citizens of the developing world might use their vote to express their policy preferences is now considered credible by many. The resemblance between the trajectory of the study of the topic in old and new democracies thus warrants further investigation as it has proven to be an elusive concept to assess and has not received as much attention in new democracies as it did in older ones.

2.2

Electoral Institutions and Political

Competi-tion

The impact of electoral institutions on political competition can be separated in two categories, as defined by Duverger (1954): their mechanical effects, and their psychological effects. The former are related to the rules defining the way in which