Out-of-wedlock births in Senegal: an empirical investigation of

their consequences for women and children

Nathalie Guilbert∗, Karine Marazyan†

Preliminary version - Please do not circulate without the authors’ permission October 31, 2013

Abstract

Marital conditions, through their impact on women’s human capital accumulation and rel-ative bargaining power in their household, are potentially important determinants of child survival. Surprisingly, the role of mothers’ marital status on children’s outcomes has received little attention. This paper investigates the relationship between births out-of-wedlock and women’s access to resources. We raise two questions in particular: (1) we first investigate the extent to which women with a premarital birth and other women marry at different conditions measured by age at first marriage, and spouse rank within marriage; (2) second, we ask to what extent children born in or out-of-wedlock have different infant mortality rates. Recent nation-ally representative Demographic and Health Survey data are used to assess the consequences of premarital birth at the mother and child levels. According to our results, premarital births and first marriage conditions are correlated, but the significance and the size of the estimated correlations vary with the gender of the child born out-of-wedlock and with the women’s ethnic group. Our results suggest that having a child out-of-wedlock accelerates first marriage, either for social and/or economic motives.

At the child level, we do not observe negative consequences for children born out-of-wedlock except under certain circumstances when their mother had the birth while still an adolescent. We find significant variations of the estimated effects of mortality rates depending on the child’s gender, the mother’s ethnic group and the age at first birth These findings confirm that social stigma is not generalized in Senegal, and that there are ways to manage both the social stigma and the economic burden that taking care of a child born out-of-wedlock raises.

Keywords: Premarital fecundity, marriage, children’s mortality, Senegal

JEL Classification Numbers: I2, J1, O1

∗

Université Paris Dauphine, LEDA, and IRD, UMR 225 DIAL. E-mail: guilbert@dial.prd.fr †

1

Introduction

Child mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa is the highest in the world and exhibits low rates of decline 1. Understanding better the factors driving persistently high levels of child mortality is clue since it will allow to improve challenging factors and to identify leverages aimed at overcoming this major public-health problem. In the analysis of the determinants of children’s mortality, women’s poor education, poor health and nutrition as well as adolescent childbearing have been identified as major risk factors for children’s survival probability (Smith et al., 2003; Conde Agudelo et al., 2005; Guilbert, 2013). Surprisingly, the role of the mother’s marital status at the day of the child’s birth has received little attention. Wagner and Mathias (2011) and Gibson and Mace (2007) have for instance investigated the link between children health and mother’s polygynous status (and spouse rank) respectively in 28 Sub-Saharan African countries and in rural Ethiopia. Shelley and Dana (2013) have analyzed the relationship between single motherhood, driven by never-married or divorced or widow mothers, and child mortality in 11 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. In this paper, we focus on the question of whether a child’s survival probability is affected by his mother ever-married status at his birth, or said differently by whether he is born before his mother first marriage i.e. out-of-wedlock2.

Premarital births are frequent in Sub-Saharan Africa. According to Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from 25 countries, an average of one in five women has a birth before marriage (Garenne and Zwang, 2006). Whereas total fecundity is globally decreasing, premarital fecundity is a rising phenomenon. From 1950 to 2000, Garenne (2008) computed that the proportion of premarital birth in the region increased by 50 percent, rising from 3.8 to 5.7 percent. A driving factor is that sexuality and procreation are increasingly dissociated in the region (Onuoha, 1992; Bledsoe and Cohen, 1993; INED, 2013).

In the context of Senegal, which is the context of our study, exploiting nationally represen-tative data from the DHS, we find that the proportion of women of reproductive age having a premarital birth increased of almost 2 percentage points (from 8.17%, it rose to 9.98%) over the period 1992-2010. In Dakar specifically, Adjamagbo et al. (2004) compute that between women born in 1942-56 and those born in 1967-76, the proportion of first births that are out of wedlock rose from 8 to 23 percent. To assert further the prevalence of premarital fecundity in the country, data from two observation population centers, collected since mid 1980, can also be exploited. One center is located near the capital city Dakar (Niakhar) and the second one is located at Mlomp near Ziguinchor in the southern part of the country. While the Serere ethnic group is over-represented in Niakhar, the Diola ethnic group is in Mlomp. In Niakhar, among first born children born between 1984 and 1995, 16.6% were born before their mother’s first marriage3. In Mlomp, 40% of the children born between 1985 and 1999 were born to single mothers. These observations suggest not only that premarital births are frequent but also that its prevalence varies significantly between geographical areas and actually, in this situation, between the two ethnic groups that are the Serere and the Diola4.

There are various reasons why being born out-of-wedlock could affect a child’s survival 1

Based on the 2012 United Nations report on the Millennium Development Goals, mortality rate reduced by 2.4% over the period 2000-2010 in Sub-Saharan Africa.

2

Therefore this analysis does not count as children born out-of-wedlock children born between two marriages. 3The proportion of premarital pregnancy amounts to 24.4%. But one third of the premarital pregnancies are legitimated by a marriage before the child’s baptism. In such a case, most of the time, marriage is organized the date of the child’s baptism.

4In Senegal, the population can be divided into 6 main ethnic groups: The Wolof and the Fulani, the two major ones, the Serere, the Diola, the Mandingue and the Soninké.

probability in Sub-Saharan Africa and in Senegal in particular. Before coming to these reasons, one should note that households, in the region, are rarely organized according to the unitary household model. As a consequence, children benefit in terms of their welfare (as usually measured by their education and/or health status) from having mothers with some bargaining power over resource allocation decisions (for Senegal, see for instance Rangé (2008), for other Sub-Saharan African countries, see Quisumbing (2000)).

Premarital fecundity could affect this bargaining power through various channels. First for girls who are enrolled, a pregnancy often leads to school drop out. Such a drop-out is notably motivated by the implicit social prohibition resulting from school mates parents’ fear that their daughters would imitate the behavior of the pregnant while unmarried girl. Also breast-feeding and other child care activities prevent mothers from going to school. Yet bargaining power is expected to increase with education (Thomas, 1994). This channel should be particularly relevant for women having a premarital birth while being adolescent, who as we will see in our data, are not the majority of women having a premarital birth.

A second channel through which a woman’s bargaining power over resource allocation can be reduced following the birth of a child out-of-wedlock is if such a birth raises social stigma. For Senegal, the fact that premarital births raise social stigma is not as obvious as in other African countries (INED, 2013). Nonetheless, it likely exists as in Senegal marriage is the only socially recognised framework for sexuality and motherhood (Adjamagbo et al., 2004). According to fieldwork interviews conducted in Dakar in 2012, school drops out the fostering of the pregnant but unmarried daughter (to the mother’s paternal aunt most often) are strategies implemented to temper the social stigma and limit the spreading of premarital sexual behaviours. Exploiting data from the population observatory in Niakhar, Adjamagbo et al. (2004) show that marriage is delayed after the birth of a child unless women can marry the child’s father which is facilitated if they belong to the same ethnic group (the Serere). If the woman cannot marry the child’s father, the fact that she marries later is interpreted by the authors as the sign of the marginalisation of single-mothers on the local marriage market5. Note however that a delay of marriage timing

does not systematically suggest that women have difficulty to find husbands because of social stigma. If the delay is relatively short, it could reflect the fact that the mother expects to wean the child before considering getting married (to the father, or any other man)6.

From the work of Adjamagbo et al. (2004), we understand that social stigma raised by the birth of a child out-of-wedlock can be managed. Marriage with the child’s father is a mean. Actually, such a marriage can be the motivation for having a child out-of-wedlock. Indeed, there are some ethnographic evidence, although outside of Senegal, that premarital fecundity can be used as a strategic mean to force a union between two persons while the respective parents are against (Dramé, 2003; Abega et al., 1994)7. Another strategy to manage the “burden” (social or at least economic) associated with marrying a single-mother is the fostering out of the child born out-of-wedlock. Fostering is prevalent in Senegal and has several motivations among which one is helping the sending household to manage shocks8. If experienced as a shock, the birth of 5The fact that the birth of a child delays women’s marriage has been observed in other contexts of Sub-Saharan Africa and has also been interpreted as the consequence of social stigma (Johnson-Hanks, 2005; Calvès, 1999).

6

One can also suggest that this delay simply reflect the fact that a mother has less time than a single-woman to invest in searching for a husband. This would be relevant if women were individually responsible for finding their husband. But in Senegal, with some exceptions, parents are responsible for finding a spouse for their children when they first marry (le Cour Grandmaison, 1969).

7Note that the child’s father is not always aware of this strategy. 8

a child out-of-wedlock can then be managed through fostering in Senegal9.

Finally, if social stigma exists then the effect of premarital births on women’s bargaining power over the allocation of the resources in their household (their initial one or the one of their husband if they marry after the child’s birth) should also vary with individual level char-acteristics such as the degree of dependance on support from the family or the network or the ethnicity.

At the end, the effect of premarital births on women’s bargaining power, and through this channel on children’s resources in health and education, is not clear for Senegal. Empirical investigations, based on large, nationally representative data, are therefore necessary to identify the average effect of interest as well as whether there are sub-groups of women and children at particular risk to design appropriate policy tools.

To our knowledge, such an analysis does not exist for Senegal. There exists for other countries of Sub-Saharan Africa (Johnson-Hanks, 2005; Gyepi-Garbrah, 1985; Meekers, 1994b; Emina, 2011; Calvès, 1999) but none of them discusses estimation bias due to either unobserved heterogeneity at the mother’s level. The identification of sub-groups of women and children at particular risk is also not systematic.

In this paper, we use nationally representative data, those from the Demographic and Health Survey collected in Senegal in 2010. We estimate the effect of being born out-of-wedlock on children’s mortality controlling for whether the children are fostered out or not and for mother time invariant unobserved characteristics. Bias introduced by potential time varying unobserved characteristics are discussed. We systematically test whether the estimated effects vary with the following characteristics: the mother’s age at first birth (whether she was adolescent or not) and ethnicity. Indeed, the relevance of the channels through which premarital fecundity could affect women’s bargaining power (education, social stigma) could vary with these characteristics. We test the heterogeneity of the effect considering an additional characteristic: the gender of the child born out-of-wedlock. Indeed, social stigma and strategies to circomvent it could differ depending on the gender of the child (Jones et al., 2010). Unfortunately, we are not able to test whether the effect is heterogeneous to the child born out-of-wedlock residing with his father or not since the DHS data do not provide this information. Yet, effects are likely to vary with this characteristic.

We complement this analysis at the child level with an analysis at the woman’s level: do premarital births affect women’s own resource access? As opposed to children, we do not have direct measures for such an access but we proxy this access looking at her marriage conditions i.e. age at first marriage and spouse rank within marriage. We test whether the effects vary with the same characteristics as those considered for the analysis at the child level. This analysis has two limits: we do not observe whether the mother married the child’s father and we cannot address the endogeneity bias due to unobserved women level heterogeneity. However, we rule out the interpretation of the correlations between premarital fecundity and marriage characteristics as reverse causality, another source of bias in this analysis, by showing that the gender of the child born out-of-wedlock matter in explaining these characteristics.

Our main findings are that having a premarital birth, and in particular having a daughter born out-of-wedlock, accelerates the timing of women’s first marriage. Once looking at specific ethnic groups, we find that, among the Fulani, women with a son born out-of-wedlock marry at the same pace as they would have had if they had not this premarital birth. They have also

9

Emina (2008) has worked on the implication of out-of-wedlock childbearing on household structure. He found for Cameroon that children born out-of-wedlock are more likely to be fostered out than children born in wedlock.

a reduced probability of marrying as first wife. This last finding is also observed for Serere women.

At the child level, we observe that, on average, children born out-of-wedlock do not ex-perience restricted access to resources with respect to children born in wedlock. This result is confirmed among all ethnic groups for children born to women who were already adults at the time of the premarital birth. However, when considering children born out-of-wedlock to women who were still adolescent, we note that Fulani girls whose mother faced difficulties to find a husband and Fulani boys have an increased probability of dying before two years old. Wolof boys born to an adolescent mother who married rapidly after the birth have also a high mortality rate.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the data. Section 3 presents the analysis at the woman level which includes the summary statistics, empirical models, results and heterogeneity analysis. Section 4 presents the analysis at the child level. It includes the summary statistics, the analysis of child living arrangements (fostering experience) and the analysis of child mortality. Finally, Section 5 concludes.

2

The 2010 DHS data

We use the Senegalese demographic and health survey data, collected in 2010 in the country, which are representative at the national level. While the initial sample count 15 335 women aged between 15-49 years old, we restrict our analysis to women aged between 15-35 years old (of number 11 836). Indeed, out-of-wedlock births are events that occur rather early in women’s reproductive life and there is a risk of recall bias on such events with interviewing women from older generations 10. In addition, by focusing on young women, we ensure that they grew up under similar social values, notably regarding premarital pregnancies and births. Among women aged between 15-35 years old (thereafter, our women sample), 59.6% have ever given birth. The latter belong to our “ever-mother sample”. Women from the ever-mother sample are the mother of 21 530 children among which 51.2% are boys. These children belong to our children sample. This means that in the children sample, all the children of women in the ever-mother sample are reported, regardless of their living status, their residential status and their age at the time of the survey.

Around fifteen percent of the women in the ever-mother sample (1 063) had a premarital birth. Given the availability on a monthly basis of the birth history for each women in the ever-mother sample, we define premarital births as all births that occurred up to one month before their mother’s first marriage11. At the child level, 7.05% of the children were born before their mother celebrates their first union (1 518). Interestingly, the data show that one third of the women with a premarital birth had actually more than one premarital birth.

DHS data report actually not the date of the first marriage but the date of the first co-habitation. Yet, in Senegal, several months can separate the celebration of the marriage and cohabitation between spouses. Usually, cohabitation starts when the bride’s family received the

10

Blanc and Rutenberg (1990) analysed the quality of retrospective, notably those on age at first sexual intercourse, age at first marriage and age at first birth in the DHS. They found that women from older cohorts tend to over report the dates of their first union and births. In fact, when looking at the data we found that women from older cohorts have been married on average at later ages than women from younger ones, which contradicts the slow but certain increase in age at first marriage (Westoff, 2003)

11In other word, given this definition, we exclude women having children between two marriages from the sample of women with a premarital birth. Thereafter, being a child born before the mother’s first marriage or being a child born out-of-wedlock refer to the same situation.

total amount of marital compensations she was asking. Therefore, there is no standard delay between celebration and cohabitation that we could apply to the date of first cohabitation to retrieve the date of the marriage celebration12. Using the date of the first cohabitation with the first spouse leads likely to overestimate the proportion of women with a premarital birth and the proportion of children born out-of-wedlock. If premarital births are associated to social stigma, and if the social stigma vanishes as the woman gets married, then we might under-estimate the effect of such a stigma on women and children’s welfare. However, the information contained in the timing of first cohabitation is actually the most relevant one in terms of changes in re-sources allocation which is what we are interested in. In Senegal, once married, a woman has to leave her household to join that of her husband. This is the virilocal residence practice13. The timing of first cohabitation thus implies that the woman has actually joined the household of her husband and/or family-in-law and that she shares dwelling and other resources with them.

3

Effects of out-of-wedlock births on women’s first marriage

conditions

We first start the analysis of the effect of premarital births by looking at whether they affect women’s first marriage conditions. We consider here two characteristics: age at first marriage and spouse rank.

3.1 Link between marital conditions and access to resources: a literature review

In this sub-section, the objective is to highlight the effect of marriage, and of its conditions, on the amount of resources women can access to and why we expect that premarital births affect marriage and its conditions (and therefore resource access). Given the data that are available, we focus on the two following marriage conditions: age at first marriage and spouse rank. Indeed, polygyny is widespread in Senegal (one fourth of men will ever be in a polygynous union)14. Women have therefore a high probability to marry as spouse of second order or more. Marriage is “an arena for reproduction”. Indeed, in African context, women are under a great deal of pressure to become pregnant once they are married (Dial, 2008). This illustrates the reproductive aim of marriage which supposedly offers a secured access to resources for mothers and their children born in wedlock.

When a woman starts her fecundity before being married, she does not benefit from the economical support to raise her child a husband and/or a family-in-law are expected to give unless she marries rapidly after the birth of the child 15. It is thus expected that women want to marry rapidly after the birth of the child in order to raise their child(ren) in a standard family and resources environment. Mondain et al. (2005) show that this is indeed the case

12

Actually, the marriage celebration itself can be divided into various events: engagement, matrimonial com-pensations payment, civil and/or religious ceremony, cohabitation, making difficult the choice of the date to identify premarital births (Adjamagbo et al., 2004; Van de Walle and Meekers, 1994). In Senegal, indeed, a couple is considered as married once the parents agreed upon marital compensations to be exchanged for the occasion.

13

This practice is not systematic among the Diola.

14Several factors can explain the high prevalence of polygyny in Senegal: important spousal age gap; remarriage practices following divorce and widowhood (called “levirat” practice)

15

Studies performed in developed countries reported that women with non marital childbearing may be denied substantial resources and support normally provide to mothers (Schoeni and Ross, 2005). Mothers in free unions received less support from their social networks than married mothers (Harknett and Knab, 2007).

of rural women, having a premarital birth, in Niakhar. These women expect more precisely to be put under good material conditions, underlining the economic dimension of marriage. If they cannot, this could reflect difficulties to find a husband. In the absence of alternative support (the network), the question of their welfare and of their child is then raised. We are thus interested in whether women with a premarital birth succeed in marrying rapidly after the birth of child or not.

However, women might choose to not marry rapidly after the birth of the child. They chose to have a child born out-of-wedlock and they do not expect from a husband to get resources to raise the child (notably because they have their own resources) 16. A delay in marriage could also simply reflect that marriage is postponed until the breast-feeding period is over 17. For these two reasons, a delay in marriage timing does not necessarily translate into lower access to economic resources. Note also that marrying rapidly after the birth of the child could be less the result of getting the soonest the needed resources to take care of the child born out-of-wedlock than the reason for giving birth out-of-wedlock. Recall indeed from the introduction that premarital fecundity could be a marital strategy. But, here, whatever is the reason of a rapid marriage, resource access should be the same. A rapid marriage could also be the result of the network’s pressure to legitimate a birth and limit the stigma it could raise. The consequences of such a rapid marriage on women and children’s access to resources are unclear (it could depend on whether the woman marries the child’s father, although there is not guarantee that such a marriage protects the woman and the child if the family in law feels like being forced). Therefore, the interpretation of the correlations of having a premarital birth with marriage timing, and then with resource access, is not straightforward.

The second marriage outcome of interest is the spouse rank. Women with different spouse rank in marriage may indeed have different access to their husband’s resources18. Several arguments have been exposed to explain why being the first spouse may be associated to higher resource access. Although these have been highlighted in contexts other than Senegal, they could apply to Senegal. When a woman enters a union as first wife she is, at least temporarily, the only spouse the husband has to share his resources with. This period can be assimilated to a monogamous period. For this reason, for Gibson and Mace (2007), children born to first wives grow under better wealth conditions than do children from higher rank wives in rural Ethiopia. For Mammen (2004), it can also explain why, in Ivory Coast, children aged 13 to 16 years old born to second or third wives are less likely to be enrolled at school and benefit from lower educational expenditures than the children born to the first wife. Moreover, the lag between the wives’ entry in the household advantages first wives who have had time to achieve higher status in the household and subsequent control over the total resources. This can be illustrated in the context of Mali by the work of Madhavan et al. (2003) who show that first wives commonly enjoy social respect, are usually in the position of “household manager ” and experience higher degree of freedom19.

On the other hand, in Senegal, first marriages are usually arranged by parents as it has to respect various mating rules established by the clan and aiming at preserving it. First mar-riages follow the clan’s objectives and, in that respect, are considered as traditional marmar-riages

16

Note that late marriages are rarely desired and not common in Senegal, except in the capital city of Dakar. National mean age at marriage is 17.5 years old in the women sample and 99% of married women got married before 30.

17Sexual relationships are commonly prohibited during the breast-feeding period. 18

This, despite the fact that the Koran asks men to treat equally their wives.

19For a theoretical discussion in an economic framework of the reason why a first wife may enjoy higher power over resource allocation, see Grossbard (1980).

(le Cour Grandmaison, 1969). Second marriage follow in contrast more individual objectives. There is an expression in Senegal saying that: “First marriage is a reasonable marriage, second

marriage is a love marriage”20. Because they were chosen by their partner more than by the partner’s family, second order wives may benefit from a higher access to the husband’s resources than first wives. Third and fourth order spouses, for the same reasons than the second order spouses, may enjoy a higher access to their husband’s resources compared to first wives. They can be treated in a specific way for another reason: they are more often the widows of elder brothers. Depending on their accumulated wealth at the date of their first husband’s death, they might have an access to different resources compared to lower-rank spouses.

Hence, it is not clear in which way being a first wife will affect a woman’s access to her husband’s resources in Senegal. Nonetheless, since this access could be different according to the spouse rank, we are interested in how a premarital birth could affect this rank in marriage. If premarital fecundity is associated with breaking social rules like the one of virginity at marriage or of exclusive marital fecundity, women with a child born out-of-wedlock should be less likely to marry as first wives, unless they, as well as the child’s father, are young, and marry each other 21. If these women do not marry the child’s father, they may find more easily protection from older men who already satisfied marriage social requirements with a first marriage.

3.2 Descriptive statistics

In Table 1, we present basic individual and household level characteristics of our women sample. In Table 2, in the first panel, information on marriage are provided for all women of the women sample who ever married; in the second panel, we describe the births all women of the ever-mother sample had. In each of these tables, information is given considering separately women with a premarital birth and other women, and among women with a premarital birth those who had their first premarital birth while being adolescent (under 18 years old) and those who had their first premarital birth while being adult (at 18 years old or older). According to our data, women with a premarital birth while adolescent represent 47.5% of the women with a premarital birth, which suggests that, in Senegal, out-of-wedlock births in Senegal is only partially linked to teenage childbearing22.

The rationale for considering separately women who had a premarital birth while being adolescent and women who had a premarital birth while being adult is that the causes of the birth as well as it effects, in particular, on the child are likely to differ. On the causes, accidental pregnancies are expected to be more common among teenagers who are less informed about contraception and sexuality at large. On the effects, adolescents having a premarital birth are less mature, physically, than adults with a premarital birth. They had also less time to accumulate knowledge on pre-natal as well as post-natal cares to provide in the interest of children23. Therefore, children born out-of-wedlock from an adolescent mother are likely to be

20

“Le premier mariage est de raison, le deuxième est d’amour”.

21Using data for Senegal, Guilbert (2013) found that women married early are more first wives than are later married women.

22

Most of the studies on premarital childbearing have associated this phenomenon to teenage childbearing. See Mturi and Moerane (2001); Klepinger et al. (1999); Levine and Painter (2003), Wolfe et al. (2007) in United States, Murthy (2011); Gyepi-Garbrah (1985); Dadoorian (2000) for a non exhaustive list of papers on teen-age childbearing. Premarital fecundity has been largely increasing over the past 20 years (Mondain et al., 2005). We observe that the share of women with adult birth out-of-wedlock overcomes that of women with adolescent birth out-of-wedlock in the DHS 1997 for the first time.

23

T abl e 1: Basic demographic chara cteristics: W omen sam ple (15-35 years old) W ome n with adolescen t W omen with adult W omen with no premarital birth premarital birth Mean tes t premarital birth Me a n test Mean test N Mean (1) N M ean (2) (1)-(2) N Mean (3) (1)-(3) (2)-(3) Exogenous c haracteristics Curren t age 505 25.2 558 27.3 0.00 10773 23.5 0.00 0.00 Age at first sex 287 14.5 452 18 .2 0.00 7 038 17.1 0.00 0.00 Ev er enrolled at sc ho ol 5 05 0.35 558 0.57 0.00 10773 0.42 0.00 0.00 No. siblings 505 8.71 558 8.96 0.32 10773 8.60 0.56 0.05 No. older sis ters 505 1.56 558 1.61 0.53 10773 1.55 0.98 0.39 No. older brothers 505 1.87 558 1.67 0.04 10 773 1.69 0.01 0.75 W o lof 505 0.19 558 0.25 0.02 10773 0.35 0.00 0.00 F ul a ni 505 0.33 558 0.18 0.00 10773 0.31 0.40 0.00 Serere 505 0.10 5 58 0.16 0.00 10773 0.13 0.03 0.03 MDS 505 0.23 558 0.28 0.05 10773 0.13 0.00 0.00 Endogenous c haracteristics Single 505 0.21 558 0.40 0.00 10773 0.34 0.00 0.01 A ccept violence ( a ) 505 0.25 558 0.15 0.00 10773 0.19 0.00 0.01 Kno ws con traception 505 0.94 558 0.98 0.00 10773 0.87 0.00 0.00 Lo w bmi ( b ) 200 0.11 217 0.10 0.66 4 165 0.23 0.00 0.00 Normal bmi 200 0.62 217 0.62 0.96 4165 0.58 0.28 0.24 High bmi 200 0.27 217 0.28 0.80 4165 0.19 0.01 0.00 P o orest quin tile 505 0.30 558 0.15 0.00 1077 3 0.23 0.00 0.00 P o orer quin tile 505 0.30 558 0.24 0.05 10773 0.22 0.00 0.34 Middle quin tile 505 0.23 558 0.27 0.17 10 773 0.23 0.76 0.03 Ric her quin tile 505 0.12 558 0.20 0.00 10773 0.18 0.00 0.24 Ric hest quin ti le 505 0.05 558 0.14 0.00 10773 0.14 0.00 0.94 Urban 505 0.36 558 0.53 0.00 10 773 0.39 0.19 0.00 R ura l 505 0.64 558 0.47 0.00 10773 0.61 0.19 0.00 Dakar 505 0.06 558 0.11 0.00 10773 0.08 0.06 0.03 Ziguinc hor 505 0.12 558 0.22 0.00 10773 0.05 0.00 0.00 Diourb el 505 0.05 558 0.04 0.62 10773 0.10 0.00 0.00 Sain t-lo ui s 505 0.04 558 0.04 0.96 10773 0.07 0.01 0.01 T am bacounda 505 0.09 558 0.06 0.03 10773 0.07 0.09 0.20 Kaolac k 505 0.08 558 0.09 0.78 10773 0.09 0.60 0.88 Thiés 505 0.06 5 58 0.08 0.19 10773 0.09 0.00 0.28 Louga 505 0.03 558 0.04 0.35 10773 0.09 0.00 0.00 F atic k 505 0.05 558 0.08 0.03 10773 0.07 0.05 0.25 K o ld a 505 0.10 558 0.06 0.02 10773 0.07 0.03 0.30 Matam 505 0.06 5 58 0.04 0.07 10773 0.07 0.48 0.00 Kaffrine 505 0.06 558 0.04 0.13 10773 0.07 0.16 0.00 Kedougou 505 0.06 558 0.03 0.00 10773 0.03 0.00 0.50 Sedhiou 505 0.14 558 0.08 0.00 1077 3 0.06 0.00 0.12 No. c hildren < 5 in hh 505 3.23 558 2.93 0.03 10773 2.90 0.00 0.77 No. hh mem b ers 505 14.2 558 13 .6 0.20 10773 13.9 0.42 0.31 No. w omen in hh 505 3.3 558 3.4 0.17 10773 3.6 0.00 0.15 % in the sample 505 4.3% 558 4.7% 10773 91% ( a )The w oman considers it normal to b e b eaten in at least one of the fiv e follo wing situations: go ing out without aski ng p ermission, neglecting the c hildren, arguing with h usband, refusing to ha v e sex and burning fo o d. ( b )This classification follo ws the W orld Health Organization’s recommendations.

more vulnerable than other children. Mothers who had a premarital birth while adolescent might also be less educated than mothers who had a premarital birth while adult since adolescents who are pregnant have often to drop out from school. Yet, education is usually positively associated with bargaining power over resource allocation (Thomas, 1994). In addition, parents might be less tolerant regarding premarital sexual behaviour from a teenage daughter than from an adult one and may urge a marriage or the fostering out of the child born out of wedlock differently. This again might affect differently children born out of wedlock from adolescent mother or adult mother.

In Table 1 we separate, in addition, characteristics that could be considered exogenous to the premarital birth - in the sense, that they were pre-determined at the date of the event - and characteristics that could be correlated with the event.

According to Table 1, the three groups of women differ in terms of various individual charac-teristics. For instance, they significantly differ in terms of their current age and in terms of their educational level measured by whether they have ever been enrolled in school. Women with a premarital birth are older than other women, which could be explained by the fact that among other women, there are women who have never been mother yet. Women who had a premarital birth while adolescent have the lowest school enrollment rate and women who had a premarital birth while adult have the highest one. Other women are in between. This suggests either that being pregnant while adolescent leads to school drop out or that the probability to have a premarital birth increases with interactions at school24. Regarding age at first sex, not sur-prisingly, women who had a premarital birth while adolescent had their first sexual intercourse on average 2 years and a half earlier than other women. But, women who had a premarital birth while adult had this same experience the latest (around 1 year later than other women). Women with a premarital birth while being adolescent are also more likely to have older broth-ers compared to the two other groups of women. Ethnicity is split into 5 groups: the Wolof, the Fulani, the Serere, the Mandingue-Diola-Soninké (MDS) and a group that gathers other African and non-African ethnic groups. Wolof and Fulani are the main major ethnic groups in Senegal (as observed in the column for other women). However, once looking at women who had a premarital birth while adolescent, it happens that Fulani and MDS women are the most represented. Once looking at women who had a premarital birth while adult, Wolof and again MDS are over-represented. So, premarital fecundity is particularly frequent among the MDS women.

Compared to other women, women who had a premarital birth while adolescent are less likely to be single at the date of the interview. This could be driven by the difference in age or by the fact that the birth of a child, very early in the women’s life, urges a marriage. Compared to women who had a premarital birth while adult, they are also less likely to be single but this is by construction. They are also more likely than other to accept domestic violence. Interestingly, this is the opposite for women who had a premarital birth while adult. For the former, this could be driven by the trauma that could be associated with an early marriage. Women with a premarital birth, early or not, have a higher knowledge of contraception compared to other women 25. They are also more likely to have a higher BMI (computed on a sub-sample of under-utilization of maternity care (especially for first prenatal visit than for likelihood of institutional delivery) and this varies mostly with ethnicity thus suggesting that “cultural attitudes may shape the level of kin and social support for unwed mothers and, in so doing, have a direct impact on their perceived barriers to care”.

24School is indeed the main place where girls can have social interactions with non kin individuals from the opposite sex.

25

all these women)26. These two last patterns could, clearly, be the result of the existence of a (premarital) pregnancy.

In addition, we can see that women with an adolescent premarital birth are more concen-trated among the poor (compared to other women) whereas women with an adult premarital birth are more likely to have middle and upper level wealth index (compared to other women). Women with an adult premarital birth are more likely to live in the region of Ziguinchor. Women with an adolescent premarital birth are more likely to live in the three regions of South Senegal: Ziguinchor, Sedhiou and Kolda. Because the MDS are concentrated in the south of Senegal this recalls back the fact that premarital fecundity is particularly frequent among the MDS. These preliminary data confirm that women with a premarital birth differ from the average women. They show also that the group of women with a premarital birth is in itself hetero-geneous depending on the age at which the birth happened. This is further confirmed by the analysis of Table 2.

In the first panel of Table 2, we describe the current marriage characteristics of the women of our women sample who ever married. Women with a premarital birth married later than other women. By construction, women with an adult premarital birth married even later. Interestingly, while women with an adult premarital birth married on average less than 3 years after the birth of their child, women with an adolescent premarital birth waited longer (3 years and a half). This difference is significant. It could indicate that women with an adult premarital birth marry more often the child’s father, and therefore faster. The average age at first birth is also interesting to compare to the age at first sex we analysed in the first table. The age at first birth is very close to the age at first sex for women with adolescent premarital birth, which feeds the hypothesis that they became pregnant over the course of their first sexual experiences, as suggested by Adjamagbo and Antoine (2002). Regarding women with adult premarital birth we observe a delay between the first sexual relationship and first birth. This suggests that these women had sexual relationship on average well before they got pregnant. Divorce rate does not differ between each sample of women. Regarding current marriage characteristics, women with an adult premarital birth are less likely than average women to be in a polygynous union whereas women with an adolescent premarital birth are more. When in a polygynous union, they are less likely to be the first spouse. The spousal age gap is also the lowest for this sub-group of women (12 years on average). The school enrolment rate of their husband is also the highest. Finally they have more decision power, regarding their own health, large purchases and the visits they would like to have, than all other groups of women. These observations suggest that women with an adult premarital birth do very specific marriages. In particular, their marriage seem less traditional (lower age gap, less often the first spouse) and/or more favorable to their welfare and potentially that of their child (decision power, husband’s education)27. This can be interpreted at least in three ways: either the premarital birth is the consequence of the desire to marry a particular man adult women had time to identify (reverse causality) or both the premarital birth and a less traditional or more favorable marriage are expected outcomes given the characteristics of the women (potentially unobserved from us); or that favorable marriage follows the arrival of a child (but only if the birth is not too young). Notwithstanding, the lower contraceptive methods are actually not that common in Senegal. Among women who ever had sexual relationship, 74.6% never used any [contraceptive method] or tried to delay or avoid getting pregnant. Our own calculations based on DHS data collected in Senegal in 2010-2011.

26We performed BMI statistics on the restricted sample of ever-mothers with no premarital birth to assert that higher BMIs among women with FPM does not result from past pregnancies. Results are very similar to those on the whole sample of women allowing us to exclude the pregnancy hypothesis.

27

T able 2: Marria ge chara cteristics (of ever married w omen of the w omen sam ple)and bir th histo r y chara cteristics (of w omen of the ever mother sample) W omen with adolescen t W omen wi th adult W omen with no premarital birth premarital bi rth Mean tes t premarital birth Mean test Mean te st N Mean (1) N Mean (2) (1)-(2) N Mean (3) (1)-(3) (2)-(3) Ev er-married w omen samp le Age at first uni o n 397 18.1 337 23.3 0.00 7104 17.2 0.00 0.00 Length of single motherho o d (in mon ths) 397 42.2 3 37 33.8 0 .00 Div orced 397 0.04 337 0.07 0.10 7104 0.05 0.40 0.17 P oly g amous 381 0.38 314 0.23 0.00 6756 0.29 0.00 0.02 First wife (within p olygamous) 144 0.31 73 0.16 0.02 1948 0.33 0.51 0 .0 0 Sp ou sa l age gap 378 16.0 311 12.1 0.00 6645 14.2 0.01 0.00 Husband ev er enrolled 3 97 0.33 337 0.45 0.00 7104 0.27 0.01 0.00 No sa y o wn health 381 0.76 314 0.73 0.34 6756 0.77 0.84 0.16 No sa y large purc hase 381 0.77 314 0.74 0.24 6756 0.8 0 0.31 0.02 No sa y visits 381 0.65 314 0.55 0.01 6756 0.66 0.62 0.00 Ev er-mothers sample Age at 1st bi rth 505 14 .8 558 20.7 0.00 59 94 18.9 0.00 0.00 No. c hildren ev er b orn 505 3.47 558 2.34 0.00 5994 3.0 8 0.00 0.00 No. living c hildren 505 3.06 558 2.18 0.00 59 94 2.78 0.00 0.00 Has c hild dead bf 24 mon ths 505 0.26 558 0.11 0.00 5994 0.19 0.00 0 .00 No. c hildren dead bf 24 mon ths 505 0.34 558 0.13 0.00 5994 0.26 0.01 0.00 Has c hild dead bf 12 mon ths 505 0.22 558 0.10 0.00 5994 0.16 0.00 0 .00 No. c hildren dead bf 12 mon ths 505 0.28 558 0.12 0.00 5994 0.20 0.01 0.00 Has c hild dead bf 1 mon th 505 0.12 558 0.07 0.01 5994 0.10 0.08 0.04 No. c hildren dead bf 1 mon th 505 0.15 558 0.08 0.00 5994 0.12 0.12 0.01 Sample: first panel: ev er-married w omen aged 15-35 y ears old; second panel: ev er-mother sample aged 15-35 y ears old.

probability to be in a polygynous union could be due to the fact that women with an adolescent premarital birth married earlier than women with an adult one. The husband of women who had an adolescent premarital birth has therefore more time to find another spouse and become polygynous than the husband of a woman who had an adult premarital birth.

The second panel of Table 2 describes the characteristics of birth history for women who have ever been mothers. Women with an adolescent premarital birth have on average more children than all other women. This is likely to be driven by the fact that they started their reproductive life the earliest. To avoid the latter pattern affect comparison in birth characteristics, measures indicating whether an event has occurred (instead of the number of event) are preferred. We observe that women who had a premarital birth while being adolescent are more likely to face the death of a child (the one born out-of-wedlock or another). Women who had a premarital birth while being adult are the least likely to face such an event. Such a difference on mortality rate recalls the idea that the marriage can be more or less favorable to women depending on the age she had the premarital birth.

From these descriptive statistics, it is rather obvious that premarital fecundity is not a random phenomenon and even further, that women with an adolescent premarital birth are different than women with an adult premarital birth. Although the causality is not clear, the former are more likely to be associated with lower welfare outcomes for themselves or their dependents (as measured by their schooling, their children’s survival rate, their marriage characteristics) compared to the latter.

3.3 Empirical models

3.3.1 Premarital fecundity and age at first marriage

To investigate the link between premarital fecundity and age at first marriage we use risk model, the risk being the one of marrying at each age given the woman is still single at the beginning of the age considered. Given the fact that marriage can occur at any date within a month within a year and that the DHS data report only the information that a marriage occurred at an unknown day within a known month, the time lengths for marriage are interval-censored. To account for such a censoring, a discrete time model, and in particular the complementary log-log model, is preferred (Jenkins, 2005). Besides, the use of discrete-time model allows to easily model time-varying covariates and thus to examine how the evolution of the risk of marrying varies with the occurrence of a premarital birth which varies with time.

The estimation of the model in clog-log implies the construction of person-age datasets. For each woman, each age at which she is at risk of entering a first union represents a distinct observation. For each woman, the observation period starts with the beginning of exposure to the risk of marrying, which is at 9 years old as no woman has married before in our sample, and runs until age at first marriage for married women or until their current age if they are still single at the date of the survey. Our dependent variable is a dummy coded 0/1 for women who married before the survey (0 while still single and 1 for the last observation) and 0 for all single women. For a better understanding, we report here below an extract from our database. We provide two different examples to illustrate the data. The first example, reported in the left-hand side part of Table 3, is that of a woman currently aged 29 who had a premarital birth at 15 years old and married at 18 years old. Observation stops with the woman’s first marriage i.e. at 18 years old. The second example, reported in the right-hand side part of Table 3, refers to a woman currently aged 22 who has been married at 20 and never had children. Here

observation stops at 20 years old, age at her first marriage.

Table 3: Data organisation - Discrete time risk model with time varying covariate

Spell Age at first Out-of-wedlock Age at first Marriage Spell Age at first Out-of-wedlock Age at first Marriage

birth birth marriage birth birth marriage

9 15 0 18 0 9 21 0 20 0 10 15 0 18 0 10 21 0 20 0 11 15 0 18 0 11 21 0 20 0 12 15 0 18 0 12 21 0 20 0 13 15 0 18 0 13 21 0 20 0 14 15 0 18 0 14 21 0 20 0 15 15 1 18 0 15 21 0 20 0 16 15 1 18 0 16 21 0 20 0 17 15 1 18 0 17 21 0 20 0 18 15 1 18 1 18 21 0 20 0 19 21 0 20 0 20 21 0 20 1

One challenge in using risk models is choosing the right function to describe the evolution of the risk of marrying at each age over time. According to the literature, the duration dependance can be modelled either as a logarithmic function or a polynomial function. Time interval dummies can also be introduced if the duration dependance is assumed to be constant within the time interval chosen and different between these time intervals. Because it offers higher flexibility, we choose a polynomial function of degree 328.

Our independent variable of interest is a time-varying dummy that signals the occurrence of premarital birth when coded 1, zero otherwise. We also include other control variables that could influence the risk of marriage. We define two specifications. The first one includes mostly exogenous control variables to avoid introducing endogeneity bias. These characteristics are the religion and the ethnic group to account for specific cultural characteristics. We also control for whether the woman has ever been enrolled in school or not. In this model, the advantage of such a measure for education is that it is likely to be predetermined at the date of the birth (contrary to a measure of educational level attained). We also control for the number of older brothers and sisters the woman has as first born daughters with older brothers might have higher pressure to marry fast (since the marital compensations received can be used to finance the marriage of an older brother29.

In the second specification, we add variables to control for the type of place of residence i.e. rural versus urban as well as the region of residence. These variables are measured at the time of the survey and thus may have been influenced by the occurrence of a birth out-of-wedlock. Notably, girls facing financial difficulties to provide for their child in rural areas often have to leave their village to go and work in the city (Mondain et al., 2005).

3.3.2 Premarital fecundity and spouse rank in marriage

Second, we examine the relationship between premarital birth and the probability that a woman enters a union as first wife or as a higher rank spouse. We consider as first wives both women engaged in monogamous unions and women holding first wife rank within polygamous

28

When testing the robustness of our estimation to specifying the duration dependance as piecewise constant, our results are qualitatively similar.

29

unions30. Are considered higher rank spouses women who are second, third or fourth wives in polygamous unions. Our dependent variable is thus a dummy coded one if the woman is in a monogamous union or first wife in a polygamous union and zero of she is second, third or fourth wife in a polygamous union.

In this analysis, we restrict the sample to women who are currently married and who married only once. Because we only have information on the spouse rank at the time of the survey, the latter restriction is necessary to ensure that we observe the characteristics of the union the woman entered while she was a single mother. There remains only one situation for which the observed spouse rank might not be the same as the one a woman had when she first married. This could be the case if the respondent entered a union as second spouse but became first wife following the divorce or the death of the official first wife. However, there is no way we can recover this information. The model is estimated in probit. It is explained by the same set of characteristics than the model for marriage timing.

3.4 Results

3.4.1 Premarital birth and age at first marriage

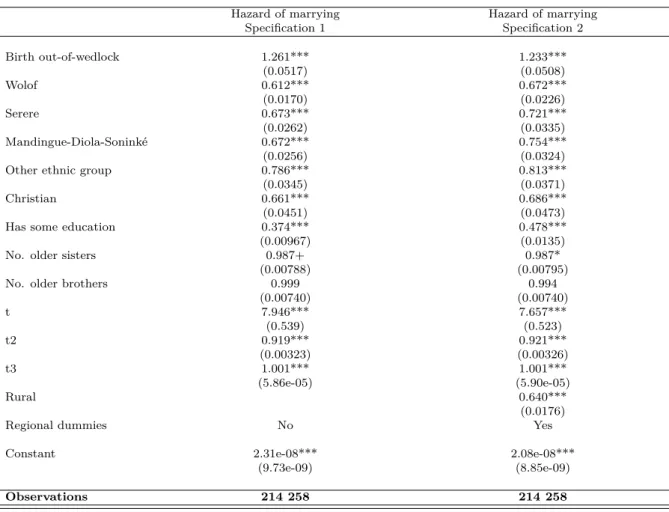

Results from the complementary log-log model are presented in Table 4. Results from specifications 1 and 2 are reported respectively in columns 1 and 2. To ease the interpretation, exponentiated coefficients i.e. hazard ratios are reported in the tables. An hazard ratio inferior to one suggests that marriage is delayed or that the time spent into singlehood is increased; an hazard ratio superior to one suggests that marriage arrives earlier or that time spent into singlehood is reduced.

Premarital fecundity appears to be positively and significantly correlated with the risk of marrying at each age in both specifications. Precisely the risk of marrying for a woman increases of 25% when having a premarital birth. This represents a reduction of 1 year in time spent into singlehood (this is obtained by computing the median age at first marriage for a woman with mean characteristics except she has not a premarital birth and for a woman with mean characteristics except she has a premarital birth. The median age of first marriage of the former group is 18.5; the median age of the later group is 17.5). Regarding the other covariates, we find that the risk of marrying at each age is higher for women from the Fulani ethnic group (reference category), and for Muslim women (reference category) compared to Christian ones. Not surprising, having some education (whether the woman has ever been enrolled in school) reduces the risk of marrying at each age. Note also that the duration dependance is inverted u-shaped.

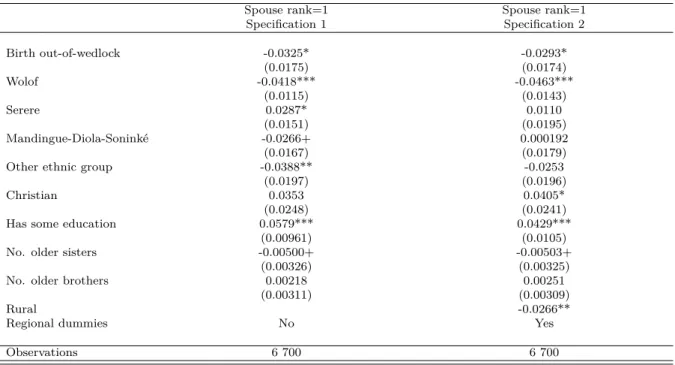

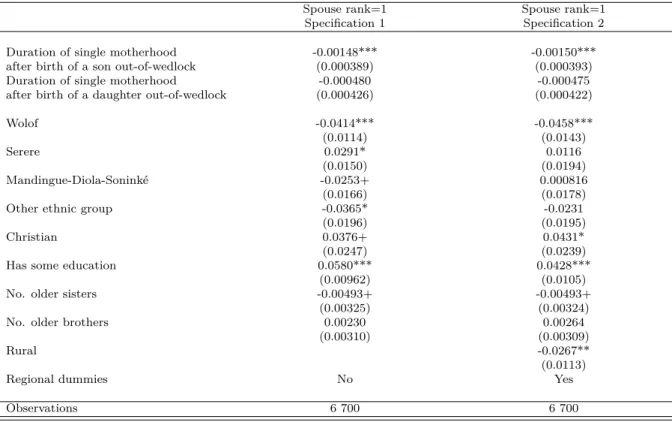

3.4.2 Premarital birth and spouse rank

The results from probit estimations are presented in Table 5. To ease the interpretation, marginal effects are reported. We find a negative correlation between premarital birth and the likelihood of marrying as first spouse significant at the 10% level.

Regarding the other covariates, we find a positive correlation between being a first spouse and education (likely to be driven by women in monogamous unions). Wolof women are less likely than Fulani women to be first wives. This is the opposite for Serere women31.

30The monogamous or polygamous status of a union is normally decided when the marriage is contracted. However, in practice it is not uncommon that monogamous unions actually transform in polygamous ones.

31Wolof is the more polygamous ethnic group in Senegal, with 51.5% of the wolof women in our sample currently engaged in polygamous unions. Serere is the less polygamous one, with 37% of polygamous women.

Table 4: Hazard of marrying each year - Complementary log-log models Exponentiated coefficients reported

Hazard of marrying Hazard of marrying

Specification 1 Specification 2 Birth out-of-wedlock 1.261*** 1.233*** (0.0517) (0.0508) Wolof 0.612*** 0.672*** (0.0170) (0.0226) Serere 0.673*** 0.721*** (0.0262) (0.0335) Mandingue-Diola-Soninké 0.672*** 0.754*** (0.0256) (0.0324)

Other ethnic group 0.786*** 0.813***

(0.0345) (0.0371)

Christian 0.661*** 0.686***

(0.0451) (0.0473)

Has some education 0.374*** 0.478***

(0.00967) (0.0135)

No. older sisters 0.987+ 0.987*

(0.00788) (0.00795)

No. older brothers 0.999 0.994

(0.00740) (0.00740) t 7.946*** 7.657*** (0.539) (0.523) t2 0.919*** 0.921*** (0.00323) (0.00326) t3 1.001*** 1.001*** (5.86e-05) (5.90e-05) Rural 0.640*** (0.0176)

Regional dummies No Yes

Constant 2.31e-08*** 2.08e-08***

(9.73e-09) (8.85e-09)

Observations 214 258 214 258

Standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. + p<0.15. Reference category for ethnic groups: Fulani; Reference category for religion: Muslim. On interpretation of coefficients: When inferior to one the coefficient reflects a reduced hazard, when superior to one it suggests an increased hazard.

Table 5: Likelihood of marrying as first wife - Probit models - Marginal effects reported

Spouse rank=1 Spouse rank=1

Specification 1 Specification 2 Birth out-of-wedlock -0.0325* -0.0293* (0.0175) (0.0174) Wolof -0.0418*** -0.0463*** (0.0115) (0.0143) Serere 0.0287* 0.0110 (0.0151) (0.0195) Mandingue-Diola-Soninké -0.0266+ 0.000192 (0.0167) (0.0179)

Other ethnic group -0.0388** -0.0253

(0.0197) (0.0196)

Christian 0.0353 0.0405*

(0.0248) (0.0241)

Has some education 0.0579*** 0.0429***

(0.00961) (0.0105)

No. older sisters -0.00500+ -0.00503+

(0.00326) (0.00325)

No. older brothers 0.00218 0.00251

(0.00311) (0.00309)

Rural -0.0266**

Regional dummies No Yes

Observations 6 700 6 700

Standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. + p<0.15. Reference category for ethnic groups: Fulani; Reference category for religion: Muslim

3.4.3 Interpretation

Our results indicate that premarital births are associated with reduced time spent into singlehood and a higher probability to enter in a polygynous union as a second or upper order spouse.

On one hand the acceleration in the timing of first marriage suggests that premarital births urge marriage either because of social stigma or because, simply, marriage provides additional resources that are needed to take care of the child. On the other hand, the reduced likelihood to marry as first wife may reflect the higher difficulties faced by women with a premarital birth to find a husband (if they cannot marry the child’s father). Recall that first marriages are often those reflecting traditional values and obeying traditional rules. If women with a premarital birth are considered as having violated some traditional values, then, it should be harder for them to marry as first spouse. Alternatively, the picture depicted by these results could be the one of women willing to marry men, who appears to be already married, but the first spouse prevents this union. The birth of a child, either voluntary or involuntary, forces the union (reverse causality).

To get insights on how to interpret these results, we pursue the analysis of marriage timing interested in whether they vary when taking into account the gender of the child born out-of-wedlock, the ethnic group of the woman, and whether the woman was adolescent or adult when she had the premarital birth. In particular, we believe that the interpretation in terms of reverse causality can be ruled out if we find that the risk of marrying varies with the gender of the child born out-of-wedlock. For the analysis of spouse rank, we test whether the result obtained vary with one additional characteristic: the time the woman spent as single following the birth of the child.

whether the child’s mother and father belong to the same ethnic group or not. Indeed, previous work by Mondain et al. (2005) suggested that marriage timing, after a premarital birth, varies with whether the father belongs to the same ethnic group of the child’s mother or not. If yes, a marriage, just after the child’s birth is easier to organize (actually after the child’s baptism). Unfortunately, we lack of one important information to do such an analysis: we do not know whether the man a woman married is the father of the child born out-of-wedlock or not. We can retrieve this information for only a sub-sample of children born out-of-wedlock: those living at the date of the interview with their mother, and who are less than 17 years old at that date (on this sub-sample, 21.9% of these children live with their father). For children who do not live with their father, so the majority, we do not have information on the biological father.

3.5 Heterogeneity analysis

3.5.1 Distinguishing the gender of the child born out-of-wedlock

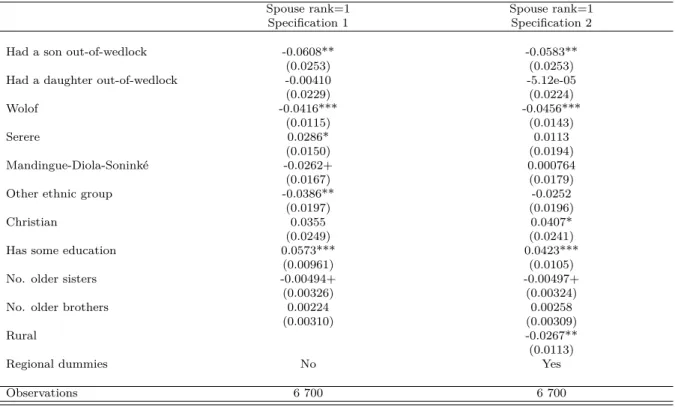

We are here interested in testing whether first marriage conditions of women with a pre-marital birth vary with the gender of the first child born out-of-wedlock. Results from age at first marriage and first wife rank likelihood models are presented in Tables 6 and 7.

Age at first marriage

From Table 6 we observe that the risk of marrying is even more accelerated when the child born out-of-wedlock is a girl (the two coefficients are significantly different from each other at the 10% level in the first specification and at the 5% in the second one). Having a girl out-of-wedlock induces a reduction of time spent into singlehood of 1 year whereas having a boy out-of-wedlock induces a reduction of less than 1 year. Therefore, this is the premarital birth of a girl that has a noticeable effect on marriage timing.

First, the fact that marriage timing varies with the gender of the child born out-of-wedlock rules out the interpretation of the correlation in terms of reverse causality. Indeed, if the premarital birth is motivated by the desire to fasten a marriage, the gender of the child should not have any effect.

Second, the fact that this is the birth of a girl that actually fastens marriage calls for some explanations. First this difference in delay is not explained by a difference in breast-feeding duration by gender. Indeed, according to our data, we do not find that boys are breast-fed longer (nor shorter) than girls. It could be explained by differences in economic value between boys and girls: girls do domestic work and at the occasion of their marriage, parents receive a brideprice. For this reason, if a potential husband (who is not the child’s father) hesitates to marry a woman with a premarital birth, the reasons for hesitating can be reduced if the child born out-of-wedlock is a girl. From fieldwork interviews, it appeared clearly that men hesitate to marry women with a premarital birth (when they are not the child’s father) because they fear that the biological father claims rights over the child in the future. Finally it could also be explained by a difference in fostering opportunity. If girls are more easily fostered out, having a daughter born out-of-wedlock could be a “burden” (economic, or social), more easily managable for women through fostering32.

The difference could also be explained if the birth of a girl was easing a marriage with the child’s father (assumed to be easier to organize, and therefore more rapid, than with another man). But we do not see reasons for that to be true 33.

32

Based on PSF data, we do not see however that girls, on average, are more fostered out than boys. 33

Table 6: Hazard of marrying each year: testing the gender differentiated effect of premarital birth

Complementary log-log model - Exponentiated coefficients reported

Hazard of marrying Hazard of marrying

Specification 1 Specification 2

Had a son out-of-wedlock 1.176*** 1.140**

(0.0662) (0.0643)

Had a daughter out-of-wedlock 1.351*** 1.333***

(0.0734) (0.0728) Wolof 0.611*** 0.672*** (0.0170) (0.0226) Serere 0.672*** 0.721*** (0.0262) (0.0335) Mandingue-Diola-Soninké 0.672*** 0.755*** (0.0256) (0.0325)

Other ethnic group 0.785*** 0.811***

(0.0345) (0.0371)

Christian 0.662*** 0.688***

(0.0452) (0.0474)

Has some education 0.374*** 0.478***

(0.00966) (0.0135)

No. older sisters 0.988+ 0.987+

(0.00788) (0.00795)

No. older brothers 0.999 0.995

(0.00741) (0.00740) t 7.949*** 7.658*** (0.539) (0.523) t2 0.918*** 0.921*** (0.00323) (0.00326) t3 1.001*** 1.001*** (5.85e-05) (5.90e-05) Rural 0.639*** (0.0176)

Regional dummies No Yes

Constant 2.30e-08*** 2.07e-08***

(9.70e-09) (8.84e-09)

Observations 214 258 214 258

Standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. + p<0.15. Reference category for ethnic groups: Fulani; Reference category for religion: Muslim. On interpretation of coefficients: When inferior to one the coefficient reflects a reduced hazard, when superior to one it suggests an increased hazard.

So, at the end, marriage seems to be eased if the child born out-of-wedlock is a girl, athough the channels through which this effect arises are not easy to identify.

Table 7: Likelihood of marrying as first wife: testing the gender differentiated effect of premarital birth - Probit models - Marginal effects

reported

Spouse rank=1 Spouse rank=1

Specification 1 Specification 2

Had a son out-of-wedlock -0.0608** -0.0583**

(0.0253) (0.0253)

Had a daughter out-of-wedlock -0.00410 -5.12e-05

(0.0229) (0.0224) Wolof -0.0416*** -0.0456*** (0.0115) (0.0143) Serere 0.0286* 0.0113 (0.0150) (0.0194) Mandingue-Diola-Soninké -0.0262+ 0.000764 (0.0167) (0.0179)

Other ethnic group -0.0386** -0.0252

(0.0197) (0.0196)

Christian 0.0355 0.0407*

(0.0249) (0.0241)

Has some education 0.0573*** 0.0423***

(0.00961) (0.0105)

No. older sisters -0.00494+ -0.00497+

(0.00326) (0.00324)

No. older brothers 0.00224 0.00258

(0.00310) (0.00309)

Rural -0.0267**

(0.0113)

Regional dummies No Yes

Observations 6 700 6 700

Standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. + p<0.15. Reference category for ethnic groups: Fulani; Reference category for religion: Muslim

Likelihood of first wife rank

From Table 7, we note that the negative effect found between having a birth out-of-wedlock and marrying as a first spouse in Table 5 is actually driven by women who had a son born out-of-wedlock (the coefficient on girls and boys are significantly different in both specifications at 10%). This pleads in favor of the interpretation according to which women face more difficulties to be the first wife of a man following the birth of a son rather than of a daughter.

3.5.2 Distinguishing ethnic groups

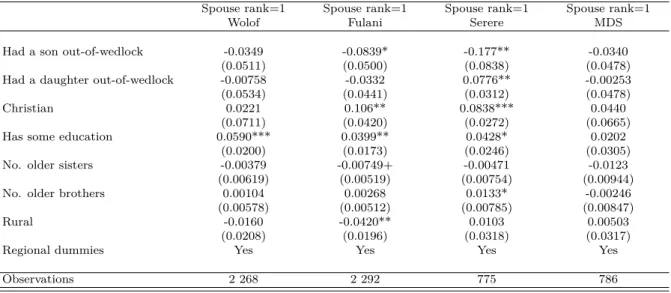

In this section, we examine the extent to which the correlations of interest vary with the gender of the child born out-of-wedlock and with the woman’s ethnic group.

Attitudes toward women with a premarital birth and their children born out-of-wedlock could vary between ethnic groups.

Recall that premarital birth is particularly frequent among the Mandingue-Diola-Soninke. The Diola population is largely animist or catholic. From fieldwork interviews, for Wolof and are less than 17 years old at the date of the survey, we find that boys born out-of-wedlock are more likely to reside with their father than girls: respectively 25.4% versus 18.5%. This suggests, at the opposite, that marriage with the child’s father is easier when the child is a boy.

Fulani, Diola’s social rules towards fecundity and marriage are often considered as less con-straining. At the opposite, the Fulani people are considered, by other ethnic groups, as more traditional34.

If social stigma exists, we thus expect premarital fecundity to be more heavily condemned among Fulani than among the former ethnic group. In terms of marriage timing, this should translate into delayed marriage (compared to what is observed in other ethnic groups). In terms of spouse rank, this should translate into a higher probability to marry as second or upper rank spouse (compared to what is observed in other ethnic groups)35. We also suspect these patterns to be re-inforced if the child born out-of-wedlock is a boy.

Results from specification 2 are shown in Tables 8 and 9. Tables 8 computes the reduced number of years spent into singlehood following the birth of a child for a given gender and in a specific ethnic group. It is based on coefficients estimated in Table 1 in the appendix.

Age at first marriage

Table 8: How much time spent into singlehood has decreased following the birth of a child, by gender and by ethnic group (in years)?

Wolof Fulani Serere MDS

Had a son out-of-wedlock 2 0 1 1

Had a daughter out-of-wedlock 1 1 2 2

Based on estimations in table 1

According to table 8, we first observe an effect of premarital fecundity on marriage timing for all ethnic groups. This suggests first that social stigma on premarital fecundity, we expect to be particularly important among the Fulani, is not the only factor affecting changes in marriage timing following a premarital fecundity.

In terms of age at first marriage, women from all ethnic groups enter marriage more rapidly following the birth of a girl out-of-wedlock. Fulani women having a child born out-of-wedlock, and in particular a son, are the women marrying the less rapidly after the birth compared to women from other ethnic groups. This finding is consistent with our expectations. Compared to other women with a premarital birth, Fulani women who had a son out-of-wedlock marry with more delay. The fact that premarital fecundity raises stigma among this ethnic group can be a reason.

Likelihood of first wife status

From Table 9, marriage conditions as measured by spouse rank following the birth of a child out-of-wedlock vary again between ethnic groups. Significant effects are found for the Fulani and the Serere but not for other ethnic groups.

34According to the data from the survey Pauvreté et Structure familiale conducted in Senegal in 2006, Fulani women, aged between 9 and 50 years old, marry on average earlier: 17.7 versus 19.45 years old; they are more likely to marry endogamously (with a man belonging to the same family: 61% versus 54%; and/or to a man belonging to the same ethnic group: 88% versus 84%); they are also less likely to ever work: 57% versus 66% and do more often domestic work (more than 28 hours par week): 69% versus 58%. These are some evidence that marriage for Fulani women is more traditional.

35

Note that none of these effects should be observed if the Fulani, because of the social stigma raised by the presence of a child born out-of-wedlock, foster out more often than other ethnic group this child

For the Fulani, as expected, the birth of a boy out-of-wedlock raises the probability to marry as second or upper rank spouse. This could be due to social stigma making difficult marriage as a first spouse. Note that the same effect is observed for Serere women. However, for Serere women, the birth of a girl increases the probability to marry as first spouse (and reduces even more importantly, than the birth of a boy, the time spent into singlehood). Results regarding both marriage timing and spouse rank for the Serere women were not expected. They could suggest that, for the Serere, the birth of a girl relative to a boy eases marriage with the child’s father (since it comes faster) or that girls have a different economic value than boys or that they have more opportunity to be fostered out (therefore, marrying a single-mother with a daughter is less challenging for any man who is not the child’s father)

Table 9: Likelihood of marrying as first wife: test of a differentiated effect of premarital birth by child gender and women’s ethnicity Probit models

-Marginal effects reported (based on specification 2)

Spouse rank=1 Spouse rank=1 Spouse rank=1 Spouse rank=1

Wolof Fulani Serere MDS

Had a son out-of-wedlock -0.0349 -0.0839* -0.177** -0.0340

(0.0511) (0.0500) (0.0838) (0.0478)

Had a daughter out-of-wedlock -0.00758 -0.0332 0.0776** -0.00253

(0.0534) (0.0441) (0.0312) (0.0478)

Christian 0.0221 0.106** 0.0838*** 0.0440

(0.0711) (0.0420) (0.0272) (0.0665)

Has some education 0.0590*** 0.0399** 0.0428* 0.0202

(0.0200) (0.0173) (0.0246) (0.0305)

No. older sisters -0.00379 -0.00749+ -0.00471 -0.0123

(0.00619) (0.00519) (0.00754) (0.00944)

No. older brothers 0.00104 0.00268 0.0133* -0.00246

(0.00578) (0.00512) (0.00785) (0.00847)

Rural -0.0160 -0.0420** 0.0103 0.00503

(0.0208) (0.0196) (0.0318) (0.0317)

Regional dummies Yes Yes Yes Yes

Observations 2 268 2 292 775 786

Standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.10. + p<0.15.

3.5.3 Distinguishing between adolescent and adult premarital birth

Following our descriptive statistics, we expect the age at first birth to be an important factor in shaping the consequences of premarital birth. We now investigate how the timing of the out-of-wedlock birth affects the timing of first marriage and the likelihood of marrying as first wife.

Age at first marriage

To have an idea about the difference in the risk faced within each group of women with premar-ital birth, we limit our sample to women with premarpremar-ital birth and compare the predictions of the survival functions in singlehood for women with adolescent premarital birth versus women with adult premarital birth. Recall that we consider as adolescent women who were at most 17 years old at the time of the out-of-wedlock birth and as adult all women who were 18 or more. We restrict the latter group to women who had birth between 18 and 22 to concentrate adult