ContentslistsavailableatSciVerseScienceDirect

Aquatic

Toxicology

j o ur na l ho me p ag e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / a q u a t o x

Changes

in

trace

elements

during

lactation

in

a

marine

top

predator,

the

grey

seal

Sarah

Habran

a,∗,

Paddy

P.

Pomeroy

b,

Cathy

Debier

c,

Krishna

Das

aaLaboratoryofOceanology–MAREB6c,UniversityofLiege,B-4000Liege,Belgium

bNERCSeaMammalResearchUnit,ScottishOceansInstitute,UniversityofStAndrews,StAndrewsKY168LB,Scotland,UK cInstitutdesSciencesdelavie,UniversitéCatholiquedeLouvain,CroixduSud2/L7.05.08,B-1348Louvain-la-Neuve,Belgium

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:Received19March2012

Receivedinrevisedform11August2012 Accepted15August2012 Keywords: Halichoerusgrypus Traceelements Lactation Maternaltransfer

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Lactationinpinnipedsrepresentsthemostsignificantcosttomothersduringthereproductivecycle. Dynamicsoftraceelementsandtheirmobilizationassociatedwithenergyreservesduringsuchanintense physiologicalprocessremainspoorlyunderstoodinmarinemammals.Thechangesintissue concentra-tionsof11elements(Ca,Cd,Cr,Cu,Fe,Hg,Ni,Pb,Se,V,andZn)wereinvestigatedinalongitudinalstudy duringthelactationperiodandduringthepost-weaningfastperiod.Blood,milk,blubber,andhair sam-pleswerecollectedsequentiallyfrom21mother–puppairsofgreyseals(Halichoerusgrypus)fromthe IsleofMayinScotland.Maternaltransferthroughthemilkwasobservedforalltraceelements,exceptfor Cd.Asanindicatoroftheplacentaltransfer,levelsinpuplanugo(natalcoat)revealedalsotheexistence ofmaternaltransferandaccumulationofallassayedtraceelementsduringthefoetaldevelopment.The placentalandmammarybarriersagainstnon-essentialmetaltransfertooffspringappeartobeabsent orweakingreyseals.Examiningthecontaminationlevelsshowedthatthisgreysealpopulationseems morehighlyexposedtoPbthanotherphocidpopulations(2.2mg/kgdwofgreysealhair).Incontrast, bloodandhairlevelsreflectedalowerHgexposureingreysealsfromtheIsleofMaythaninharbour sealsfromthesoutheasternNorthSea.Thisstudyalsoshowedthattraceelementconcentrationsinblood andblubbercouldchangerapidlyoverthelactationperiod.Suchphysiologicalprocessesmustbe con-sideredcarefullyduringbiomonitoringoftraceelements,andpotentialimpactsthatrapidfluctuations inconcentrationscanexertonsealhealthshouldbefurtherinvestigated.

Crown Copyright © 2012 Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Trueseals,orphocids,aremarinemammalsthatcan accumu-latediversecontaminants,suchasorganochlorines(Debieretal., 2003b,2006;VandenBergheetal.,2010)andtraceelements(Das etal.,2003,2008),athigherlevelsthanthosemeasuredintheir sur-roundingenvironment.Theirpositionasapexpredatorsinthefood chain,theiroccurrenceadjacenttoheavilypopulatedWestern soci-eties,alonglifespan,andthechemicalcharacteristicsofparticular groupscontributetothisphenomenon.Asmallincreasein environ-mentaltraceelementconcentrationscanleadtosignificantimpacts onmarineorganisms(Bustamanteetal.,2003).Marinemammals arethusconsideredassentinelspeciesinthemarineenvironment (Bossart,2006).

∗ Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+3243664844;fax:+3243665147.

E-mail addresses:S.Habran@ulg.ac.be, sarah.habran@gmail.com (S. Habran), pp6@st-andrews.ac.uk (P.P. Pomeroy), cathy.debier@uclouvain.be (C. Debier), Krishna.Das@ulg.ac.be(K.Das).

Phocids leavethewater and comeashoreonland orice for breeding,sucklingtheiryoung,moulting,andresting.Theseperiods ashoreprovideaconsiderableopportunityforsamplecollectionin comparisonwithotherfree-rangingmarinemammals.Inthe east-ernAtlantic,femalegreysealscomeashoretopupintheautumn (FedakandAnderson,1982).Motherseachgivebirthtoasingle white-coatedpup,which theysuckleforapproximately18days (FedakandAnderson,1982).Lactationrepresentsthemost signif-icantcosttomothersduringthereproductivecycleofpinnipeds (Yunkeretal.,2005).FemalegreysealsintheUKfast through-outthenursingperiodandrelyentirelyontheirendogenousfat andproteinreservestomaintaintheirmetabolicdemandsandto producemilk.Theysecreteafat-richmilkinwhichlipidcontent rangesfrom30%to60%(Pomeroyetal.,1996).Lactatingfemales loseanaverageof39%oftheirpostpartummassduringthe lacta-tionperiod,typicallyefficiencyofmasstransferfrommothersto pupsingreysealsis45%(Pomeroyetal.,1999).Pupsmoulttheir whitenatalcoat(alsocalled“lanugo”)aroundthetimeof wean-ingandthenremainonthebreedingcolonyfor1–4weeksbefore goingtosea(Reilly,1991).Duringthispost-weaningperiod,pups alsofastandrelyonreservesaccumulatedduringlactation. 0166-445X/$–seefrontmatter.Crown Copyright © 2012 Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Therelativelybriefbutphysiologicallyactivelactationperiod, followedbyaperiodofpost-weaningfastforpups,offersa valu-ableopportunitytoinvestigatechangesinlevelsofcontaminants inadultfemales andtheiroffspring. Indeed,themobilizationof contaminantspotentiallyassociatedtoenergyreserves(lipidsand proteins)during suchan intense physiologicalprocess remains anareaofconsiderableinterestformarinemammals.Most infor-mation onthe transfer of pollutants from mother to offspring throughtheplacentaandthroughthemilkconcentrateson anthro-pogenicorganicchemicals.Previousstudies(Debieretal.,2003a,b; Pomeroyetal.,1996;VandenBergheetal.,2010,2012)showed that suckling newborns could be exposed to high amounts of organicpollutants(PCBs,PBDEs,etc.)duringacritical developmen-talperiodoftheirlife.Incontrast,fewstudies(Habranetal.,2011; Wagemannetal.,1988)haveinvestigatedlevelsoftraceelements inrelationtoreproductionandmaternaltransferofbodyburdens. In addition to their natural occurrence, trace elements in marineenvironmentarisefromanthropogenicreleasesassociated toincreasedurbanandindustrialactivitiesinthecoastalregions, andtooffshorewastedisposal.Theseanthropogenicreleasesoccur throughriver,atmosphere,anddirectdischarges,andcontributeto thecontaminationofseasbymetals(OSPAR,2010).Traceelements canbeessentialor non-essentialforliving organisms.Essential traceelements,suchasZn,Fe,Cu,Se,orCr,arepartofprotein com-plexes(metalloproteins),arerequiredforenzymaticactivities,and canplaystructuralrolesinconnectivetissueandcellmembranes (Bryanetal.,2007).Theyarethusbeneficialforlivingorganismsat lowconcentrations,butcanbecometoxicathigherconcentrations, aboveacertainthreshold.Theessentialityofothertraceelements, likeNiandV,hasalsobeenwellestablishedforvariousbiological functions,buttheinformationontheiroptimalanddeficient con-centrationsislimited.Non-essentialtraceelements,suchasHg,Cd, andPb,arenotrequiredforphysiologicalprocessesandare consid-eredtoxicevenatverylowlevels(AMAP,2005;Wolfeetal.,1998). AlthoughCaisanessentialmacro-element,itwasalsoincluded inthisstudytoassessthepotentialinteractionswithPbandCd. Indeed,PbbindstightlytobothCaandZnsitesinproteinsandalters theiractivity(Godwin,2001).ExposuretoCdmayalsocausebone demineralizationandskeletaldamageduetothehyperexcretion ofCa(AMAP,2005).

Grey sealshave lifehistorycharacteristicsthatmake thema good‘model’inwhichtostudytheeffectsoflactationandfasting onthelevelsoftraceelementsinpinnipeds.Inthispaper,we inves-tigatedthechangesinlevelsof11elements(Ca,Cd,Cr,Cu,Fe,Hg,Ni, Pb,Se,V,andZn)inalongitudinalstudyon21greysealmother–pup pairsduringthelactationperiodandapartofthepost-weaning fastperiod.Themainobjectiveswereto(1)investigatetheeffect ofphysiologicalprocessesonthedistributionoftraceelementsin differenttissues(blood,blubber,andhair)ofmothersandtheir off-spring,and(2)characterizethemineralcontentingreysealmilk andtoassesschangesinlevelsduringlactation.Tothebestofour knowledge,thispaperrepresentsthefirstassessmentofthelevels oftraceelementcontaminationinUKgreysealsfromtheNorth Sea.

2. Materialsandmethods 2.1. Fieldtechniques

This study was performed on the Isle of May, Scotland (56◦11#N, 2◦33#W; Fig. 1), during the 2008 breeding season

(October–December).Onarrivalatthecolony,femaleswere mon-itoredandbirthdatesofpupswererecordedbydailyobservations of the breeding areas. Twenty-one known mother–pup pairs werecaptured in earlylactation (at2–4days postpartum) and

Fig.1.LocationofthegreysealcolonyontheIsleofMay(Scotland),intheNorth Sea.

recapturedapproximately13dayslaterinlatelactation(at15–17 days postpartum).Samplesofmaternalblubber, blood, milk,as wellaspupbloodwerecollectedfrompairsateachcapture. Moth-erswereimmobilizedwithanintramuscularinjectionofZoletil 100(1ml per100kgof estimatedbody mass; Virbac, UK,Ltd.) andimmobilizationwasmaintainedwithintravenous injections ofZoletil ifnecessary.Pupswererestrainedandcaptured man-ually.Bloodsampleswereobtainedfromtheextraduralveinof mothersandpups.Wholebloodsampleswerecollectedin6ml VacutainerTM plastic tubes treated with K

2EDTA anticoagulant

(FisherScientificInternational)andcertifiedfortraceelement anal-yses (throughout thetext, ‘blood’ refers to whole blood). Milk sampleswerecollectedfromeachfemale5minaftera1ml intra-venousinjectionofoxytocin(LeoLaboratories,Dublin,Ireland)to stimulaterelease ofthemilk.Milkwasexpressedfromtheteat usingacleancut-offsyringeandwastransferredtotwo5ml plas-tictubes.Ablubberbiopsywastakenatbothcapturesfromthe lateralpelvicareaafterasubcutaneousinjectionoflocal anaes-thetic(Lidocaine,3ml).Asmallpartoftheanaesthetizedareawas cleanedwithalcohol.Asmallincisionwasthenmadeanda blub-berbiopsy,extendingthefulldepthoftheblubberlayer,wastaken witha6mmbiopsypunch(Acu-Punch®,Acuderm).Blubber

biop-sieswerestoredinplastictubes.Mothers’hairandpups’lanugo werecollectedonlyonceduringlactation.Hairandlanugoareinert tissuesin whichtraceelementsarenot consideredbioavailable (Wenzeletal.,1993).Concentrationsinthesetissuesreflect con-centrationsininternaltissuesfromcirculatinglevelsofelements atthemomentoftheirgrowth,i.e.,duringthepreviousmoultfor mother’shairorthefoetaldevelopmentforpup’slanugo.In moth-ers,apatchofhair(approximately15cm×15cm;∼3g)wasshaved fromthedorsalmidline region,inthelowerpart,usinga “one-use”stainlesssteelblade.Lanugoofpupswassimplypluckedfrom thedorsalmidlineregionwhentheybeganmoulting,atthe sec-ondcapture.Hairandlanugowereplacedinapolyethylenebag. Antibioticwasgiventomotherwithaprophylacticintramuscular

Table1

Biometry(mean±SD;range)ofgreysealmothersandpupsatdifferentstagesoflactationanddevelopment(T1,earlylactation;T2,latelactation;T3,earlypost-weaning fast;T4,middlepost-weaningfast).

n Mass(kg) Standardlength(cm) Axialgirth(cm)

Mothers T1 21 164 ±27(125–232) 168±8(148–180) 145±12(125–166) T2 21 123±22(90–182) 165±8(150–182) 126±10(111–144) Pups T1 21 18±3(12–24) T2 21 39±8(24–50) T3 15 39±6(30–48) T4 11 36±5(27–44)

Lactationduration(day):19±2(16–23).Pupsexratio(female:male):48:52.

injectionofOxytetrin(oxytetracycline,10–15ml).Sixteenofthe

21pupswererecapturedonceortwiceafterweaning(arounddays

19and30postpartum)tocollectbloodandblubbersamples,

fol-lowingthesameprocedureasdescribedabovewiththemothers.A

4mminsteadofa6mmbiopsypunchwasusedtosampleblubber

fromweanedpups.Ateachcapture,ameasuringtapewasusedto

recordmother’snosetotaillengthandaxialgirth.Motherswere

weighedusingascale(SalterIndustrialMeasurementsLtd.,West

Bromwich,UK;capacity500±0.2kg)suspendedfromatripod,and

sucklingandweanedpupswereweighed±0.5kgonaspring

bal-ance(SalterIndustrialMeasurementsLtd.,WestBromwich,UK)at

eachsampling.Thepup’ssexwasdetermined.Biometricdataon

themother–puppairsaresummarizedinTable1.

Mothersandpupswereindividuallyidentifiedatthefirst cap-turewithapaintmarktoaidrecapture.Aftereachprocedure,the mother andpup werereleasedand monitoreduntilthefemale hadregainedmobility.Allcaptureandhandlingprocedureswere performedunderUKHomeOfficeprojectlicence#60/3303and conformedtotheAnimals(ScientificProcedures)Act1986.All sam-pleswerestoredat−20◦Cinthelaboratoryuntilanalysis.

2.2. Samplepreparation

Priortoanalysis,bloodsampleswerefreeze-dried,thenground withamortarandpestleintopowder.Watercontentwas deter-mined.Afterthawing,maternalhairandpuplanugowerewashed ultrasonicallywithreagentgrade acetone(acetone for analysis, EMSURE®,Merck)andwererinsedrepeatedlywith18.2M!cm

deionized water toremoveexogenous contaminants,according tothemethodrecommendedbytheInternationalAtomicEnergy Agency(ChattandKatz,1988).Hairandlanugosampleswerethen freeze-driedfor24h.

Blubberofsealsisstratifiedinchemicallydistinctlayers,each havingadifferentfunction:(1)theouterlayerisprimarily struc-tural andthermoregulatory, (2)theinner layeris metabolically activewithafattyacidcompositionthatisstronglyaffectedbylipid mobilization/deposition,and(3)themiddlelayerisastoragesite (Strandbergetal.,2008).Mobilizationofelementswastherefore investigatedintheinnerandouterblubberlayerswhenitwas pos-sible.Blubberbiopsiesofmotherswerelargeenoughtocutthem intwoequalpartsseparatingtheinnerandouterblubberlayers. Blubberbiopsiesfromweanedpupswereanalysedwhole. 2.3. Elementanalyses

Concentrationsof elements(Cd, Cr,Cu, Fe,Ni,Pb, Se,V, Zn, andCa)weremeasuredinblood,blubber,milk,hairandlanugoof 21mother–puppairsduringthebreedingseason.Approximately 0.2goffreeze-driedblood,0.25gofwashedandfreeze-driedhair orlanugo,and0.5mlofthawedmilkwereweighedtothe near-est0.0001g. Thawedblubber sub-samples (∼0.2g, mothers)or thewholebiopsy(weanedpups)wereweighed. Allthese sam-plesweresubjectedtomicrowave-assisteddigestioninTeflonTM

vessels with 4ml HNO3 (65%), 1ml H2O2 (30%) and 3ml of

18.2M!cmdeionizedwater.Aftercooling,sampleswerediluted to50mlwith18.2M!cmdeionizedwaterinavolumetricflask. ConcentrationsofCd,Cr,Cu,Fe,Ni,Pb,Se,V,ZnandCawere deter-minedbyinductivelycoupledplasmamassspectroscopy(ICP-MS, PerkinElmer,Sciex,DCR2).Multiple-elements(74Ge,103Rh,209Bi,

and 69Ga)internalstandards (CertiPUR®,Merck)wereaddedto

eachsampleandcalibrationstandardsolutions.Qualitycontroland qualityassuranceforICP-MSincludedfieldblanks,methodblanks, certifiedreferencematerials(CRMs)–SeronormL-3,DOLT-3, NIES-13,andBCR-063.Certifiedreferencematerialrecovery(%)andthe instrumental quantificationlimitsforeachelementarelistedin Table2.Cadmiumwasnotdetectedinblood,blubber,andmilk. NiandSewerebelowthelimitofquantificationinallbloodand blubbersamples,respectively.V,Cr,andPbwerebelowthelimit ofquantificationinsomebloodsamples(29%,13%,and11%of ana-lysedsamples,respectively).Databelowquantifiablelimitswere notsubjectedtofurtherstatisticalanalyses.Reported concentra-tionsforallelementsinblood,blubberandmilkareexpressedon awetweightbasisinmg/kg,whereasconcentrationsforhairand lanugoareexpressedonadryweightbasisinmg/kg.

2.4. TotalHganalysis

Approximately30–50mgoffreeze-driedbloodand1–4mgof hairandlanugowereaccuratelyweighedandloadedintoquartz boats. The masses were recorded tothe nearest 0.01mg. After thawing,milksampleswerehomogenizedandaliquotsof30–40!l were weighed and loadedinto quartzboats. BecauseHg levels inmilkwerelow,3–4quartzboatswereconcentratedtoobtain theHgvalueofonesample.TotalHg(THg)concentrationswere determinedbyatomicabsorptionspectroscopy(AAS,Direct Mer-curyAnalyzerDMA-80,Milestone).Themethodhasbeenvalidated forsolid samplesusingUS EPAMethod7473.Qualityassurance methodsincludedevaluatingbymeasuringblanks,duplicates,and CRMs–SeronormL-3andNIES-13withevery10samples(Table2). Digestedsamplesofblubberwereusedfortraceelementanalysis, includingTHganalysis,toassuresamplehomogeneity.However, THgcouldnotbedeterminedinblubbersamplesbecauselevels werebelowthelimitofquantificationafterthemicrowave-assisted digestionandthesuccessivedilution(THg<0.150mg/kgww blub-ber).

2.5. Statisticalanalyses

AKolmogorov–Smirnovtestwasusedtodeterminewhether datadepartedfromnormality.Thevariables werenotnormally distributedandnon-parametrictestswereusedforstatistical anal-yses.Toevaluatechangesinelementlevelsduringbreedingseason intissues,Wilcoxonsigned-ranktestswereusedtocomparemeans atdifferentsamplingtimes.Similarly,differencebetween moth-ersandpupsinbloodandhairlevelsweretestedusingWilcoxon signed-ranktests.TheSpearman’srankcorrelationcoefficientwas

Table2

Certifiedreferencematerialrecoveries(%,n=10)andinstrumentalquantificationlimits(IQL,ppb)forelementanalyses.

Element Method IQL Certifiedreferencematerialrecovery(%)

SeronormL-3a DOLT-3b NIES-13c BCR-063d

Ca ICP-MS 0.534 99 n.c. 90 90 Cd ICP-MS 0.002 98 99 90 n.c. Cr ICP-MS 0.002 107 84 n.c. n.c. Cu ICP-MS 0.009 97 104 90 106 Fe ICP-MS 0.042 98 99 87 81 Ni ICP-MS 0.022 n.d. 100 n.c. n.c. Pb ICP-MS 0.005 98 109 94 n.d. Se ICP-MS 0.108 109 96 76 n.d. V ICP-MS 0.001 93 n.c. 76 n.c. Zn ICP-MS 0.032 91 103 84 75 Hg AAS 0.898 85 n.d. 95 n.c.

n.c.,notcertifiedvalue;n.d.,notdetermined.

aSeronormLevel3,Traceelementswholeblood(Sero,Billingstad,Norway) bDOLT-3,Dogfishliver(NationalResearchCouncilofCanada,NRCC,Ontario,Canada) cNIES-13,Humanhairno.13(NationalInstituteforEnvironmentalStudies,NIES,Ibaraki,Japan) dBCR-063,Skimmilkpowder(InstituteforReferenceMaterialsandMeasurements,IRMM,Geel,Belgium)

usedtotestcorrelationsbetweentwovariables.Statistical anal-ysisofthedatawasperformedusingStatisticasoftware(Statsoft Inc.,Version10)andp<0.05wasconsideredassignificant(with ˛=0.05).Resultsarepresentedasmean(median)±standard devi-ation(SD),range.

3. Results

Resultsofelementsinblood,milk,blubber,andhairofgreyseals atdifferentstagesoflactationanddevelopmentaresummarized inTable3.Elementconcentrationsweredeterminedin blubber sub-samples(innerandouterlayers)inmothers,andinthewhole biopsiesinweanedpups.Tocompareeasilyvaluesbetween moth-ersandweanedpups,meanconcentrationsinthewholebiopsyin motherswerealsocalculatedfromconcentrationsinblubber sub-samples(Table3).Elementlevelsingreysealmothersandpupsin earlylactationarefirstdescribedandcompared(Sections3.1and 3.2).Changesinconcentrationsduringlactationandpost-weaning fastarethenexamined(Section3.3).Thelastsectionassessesthe relationshipsbetweenelements,tissues,andbiometricparameters ofgreyseals(Section3.4).

3.1. Levelsoftraceelementsingreysealfemalesfromearly lactation

ThelactatingfemalegreysealsfromtheIsleof Mayshowed elementconcentrationsinbloodthatdecreasedaccordingtothe followingpattern:Fe>Ca>Zn>Se>Cu>Hg>Pb>Cr>V(Table3). Mercuryhadthegreatestlevelsofthenon-essentialmetals mea-sured in blood, with 0.083mg/kg ww in early lactation. The variationamongindividualsinbloodconcentrationsrangedfrom 5%to109%accordingtoelement,withthelowestvariabilityforCa andFelevels(5–12%)andthegreatestforPbandVlevels(43–109%, Table4).

Element concentrations in maternal blubber followed the sequence:Fe>Ca>Zn>Ni>Cu>Cr>Pb>V(Table3).Iron,V,andPb levelsshowedaveryimportantvariabilityinblubber(upto84%, 127%,and144%,respectively;Table4).LevelsofNi,Cr,Pb,andV inblubberweregreaterthanthoseinblood(Table3).Resultsin theblubbersub-samplesofgreysealmothersshowedno signifi-cantdifferenceinconcentrationsbetweeninnerandouterblubber inearlylactation(forallelements,p>0.05,Wilcoxonsigned-rank tests).

In contrast with blood and blubber, all element concentra-tionsinthematernalhairwereabovethelimitofquantification. Elementconcentrationsinmaternalhairdecreasedaccordingtothe

following pattern: Ca>Zn>Fe>Hg>Cu>Se>V>Pb>Ni>Cd>Cr (Table3).

Allelements,exceptCd,weredetectedinthemilkandfollowed thesequence:Ca>Fe>Zn>Se>Cu>Ni>Pb>Hg>Cr>V.Levels of Ca,Zn,Ni,Pb,Cr,andVweregreaterinmilkthaninmaternalblood, whileFe,Cu,Se,andHglevelsinmilkwerelessthanthoseinblood (Table3).LevelsofNi,Cr,Pb,andVinmilkwerelessthanthose in blubber(Table3).Theproportionsofeach elementinblood, blubber,hair,andmilkoflactatingfemalegreysealsareshown inFig.A1.

3.2. Levelsoftraceelementsingreysealpupsfromearlylactation All elements, except Ni and Cd, were detected and quan-tified in pup blood (Table 3). Element concentrations in pup blood decreased according to the same pattern as mothers (Fe>Ca>Zn>Se>Cu>Hg>Pb>Cr>V).LevelsofFe,Ca,Zn,andCu inpupbloodrosefrom90%to116%ofthematernallevelsinearly lactation(at2–4dayspostpartum;Fig.2).LevelsofPb,Cr,andV inbloodwereverylow(<0.012mg/kgww);neverthelesspup lev-elsinearlylactationweresimilartomaternallevelsforPboreven greaterthanmaternallevelsforVandCr(177%and144%ofthe maternalvalue,respectively;Fig.2).Incontrast,bloodSelevelin pupsinearlylactationwasmuchlessthanthatinmothersatthe sametime(∼38%ofthematernalvalue),andHglevelinpupswas halfthatofmaternallevel(Fig.2).

Allelementswere detectedin pup lanugoand followed the sequence:Ca>Zn>Fe>Hg>Se>Cu>Pb>Ni>V>Cr>Cd(Table3). OnlyZnlevelwasgreaterinlanugothaninmaternalhair(122vs. 101mg/kgdw;Fig.3).Allotherelementsshowedlower concentra-tionsinlanugo(forallp≤0.001,Wilcoxonsigned-ranktests;Fig.3). Nevertheless,Se,Cu,andHglevelsinlanugowerequitesubstantial andshowed76%,73%,and62%ofthematernalvalue,respectively (Fig.3).

Theproportionsofeachelementinpupbloodandlanugoare giveninFig.A1.

3.3. Changesoftraceelementconcentrationsinblood,milk,and blubberthroughoutlactationandpost-weaningfast

Duringlactation,concentrationsvariedsignificantlyin mater-nalbloodforFe,Zn,Se,andHg:whileFeandSelevelsdecreased, Zn and Hg levels increased between early and late lactation (Table5).In pupblood, mostelementconcentrations increased duringlactation. OnlyFeandHg puplevelsdecreasedbetween earlyand latelactation,upto50%forHg(Table5).Atweaning,

Table 3 Element concentrations (mean (median) ± SD (range); in mg/kg ww) in blood, milk, blubber, and hair of grey seals. Samples from 21 mother–pup pairs were collected in early lactation (T1), in late lactation (T2), in early post-weaning fast (T3), and in middle post-weaning fast (T4). n Ca Fe Zn Blood Mothers T1 21 48 (48) ± 2 (42–53) 544 (542) ± 25 (487–592) 2.3 (2.3) ± 0.1 (1.9–2.5) T2 21 48 (48) ± 4 (39–57) 520 (500) ± 65 (427–707) 2.5 (2.5) ± 0.2 (2.1–2.9) Pups T1 21 56 (56) ± 6 (46–64) 573 (570) ± 58 (465–673) 2.3 (2.3) ± 0.3 (1.9–2.8) T2 21 66 (67) ± 4 (58–74) 516 (518) ± 33 (440–563) 2.5 (2.5) ± 0.2 (2.1–2.8) T3 16 63 (64) ± 5 (54–70) 551 (552) ± 36 (477–614) 2.8 (2.9) ± 0.3 (2.3–3.1) T4 12 62 (62) ± 5 (52–69) 583 (582) ± 35 (533–651) 2.9 (2.9) ± 0.2 (2.6–3.3) Milk Mothers T1 21 682 (677) ± 120 (494–924) 24 (25) ± 7 (12–38) 7.3 (7.2) ± 1.0 (5.6–9.3) T2 21 957 (920) ± 172 (707–1384) 17 (16) ± 5 (9–30) 6.7 (6.6) ± 0.7 (5.1–7.9) Blubber Mothers T1 21 16 (14) ± 7 (9–37) 28 (20) ± 23 (4–75) 1.2 (1.2) ± 0.3 (0.8–1.8) T2 20 24 (25) ± 7 (11–35) 65 (66) ± 34 (9–145) 2.2 (2.3) ± 0.7 (1.2–3.6) Pups T3 16 13 (12) ± 3 (9–20) a 14 (9) ± 11 (6–42) 1.3 (1.2) ± 0.5 (0.9–3.0) T4 12 12 (11) ± 3 (8–16) 12 (10) ± 8 (5–30) 1.5 (1.2) ± 0.9 (0.7–4.3) Hair * Mothers T2 21 1936 (1854) ± 474 (1306–3394) 87 (81) ± 56 (16–234) c 101 (97) ± 9 (83–119) c Pups T2 20 259 (222) ± 177 (81–773) 9 (8) ± 4 (4–20) 122 (117) ± 13 (105–146) n Cu Se Hg Blood Mothers T1 21 0.60 (0.60) ± 0.06 (0.50–0.72) 1.9 (1.8) ± 0.5 (0.9–2.7) 0.083 (0.066) ± 0.046 (0.042–0.210) T2 21 0.57 (0.57) ± 0.06 (0.47–0.75) 1.7 (1.6) ± 0.5 (0.7–2.5) 0.104 (0.094) ± 0.055 (0.047–0.248) Pups T1 21 0.53 (0.52) ± 0.07 (0.43–0.64) 0.7 (0.7) ± 0.2 (0.5–1.1) 0.041 (0.033) ± 0.017 (0.023–0.080) T2 21 0.73 (0.72) ± 0.07 (0.62–0.92) 1.2 (1.2) ± 0.6 (0.5–2.2) 0.021 (0.019) ± 0.011 (0.010–0.055) T3 16 0.79 (0.79) ± 0.07 (0.65–0.92) 1.8 (1.8) ± 0.6 (0.7–2.7) 0.025 (0.022) ± 0.011 (0.014–0.055) T4 12 0.85 (0.84) ± 0.12 (0.73–1.19) 2.0 (2.1) ± 0.7 (0.7–2.7) 0.021 (0.019) ± 0.008 (0.013–0.036) Milk Mothers T1 21 0.45 (0.44) ± 0.06 (0.36–0.60) 0.9 (0.8) ± 0.4 (0.4–2.0) 0.012 (0.012) ± 0.004 (0.006–0.022) T2 21 0.53 (0.51) ± 0.08 (0.41–0.76) 0.4 (0.4) ± 0.1 (0.2–0.6) 0.021 (0.017) ± 0.010 (0.010–0.047) Blubber Mothers T1 21 0.16 (0.15) ± 0.05 (0.09–0.30) <0.26 n.d. T2 20 0.23 (0.23) ± 0.07 (0.12–0.37) <0.26 n.d. Pups T3 16 0.35 (0.34) ± 0.23 (0.12–0.72) <0.26 n.d. T4 12 0.28 (0.24) ± 0.16 (0.14–0.61) b <0.26 n.d. Hair * Mothers T2 21 4.2 (3.7) ± 1.1 (2.9–6.8) c 4.1 (4.4) ± 1.2 (2.3–6.2) 7.7 (6.3) ± 5.3 (1.0–20.9) Pups T2 20 2.8 (2.8) ± 0.2 (2.4–3.3) 2.9 (2.9) ± 0.5 (1.7–4.2) 4.6 (3.8) ± 2.3 (2.3–11.7)

Table 3 (continued ). n V Cr Ni Blood Mothers T1 21 0.0005 (0.0004) ± 0.0003 (<0.0003–0.0011) 0.0016 (0.0013) ± 0.0008 (<0.0012–0.0043) <0.021 T2 21 0.0004 (0.0003) ± 0.0002 (<0.0003–0.0009) 0.0014 (0.0014) ± 0.0007 (<0.0012–0.0039) <0.021 Pups T1 21 0.0007 (0.0006) ± 0.0003 (<0.0004–0.0015) 0.0019 (0.0020) ± 0.0004 (0.0014–0.0029) <0.015 T2 21 0.0009 (0.0005) ± 0.0010 (<0.0006–0.0020) 0.0020 (0.0019) ± 0.0006 (0.0014–0.0039) <0.019 T3 16 0.0006 (0.0005) ± 0.0003 (<0.0003–0.0015) 0.0025 (0.0023) ± 0.0009 (0.0014–0.0048) <0.015 T4 12 0.0007 (0.0005) ± 0.0003 (<0.0003–0.0014) 0.0025 (0.0021) ± 0.0011 (0.0017–0.0053) <0.015 Milk Mothers T1 21 0.004 (0.003) ± 0.004 (0.001–0.012) 0.004 (0.003) ± 0.003 (0.002–0.015) 0.030 (0.020) ± 0.017 (<0.015–0.063) c T2 21 0.005 (0.004) ± 0.004 (0.001–0.013) 0.005 (0.003) ± 0.005 (<0.001–0.018) 0.034 (0.026) ± 0.023 (<0.015–0.087) Blubber Mothers T1 21 0.006 (0.003) ± 0.007 (0.001–0.031) 0.079 (0.073) ± 0.031 (0.032–0.136) 0.261 (0.258) ± 0.042 (0.210–0.391) T2 20 0.012 (0.008) ± 0.014 (0.002–0.069) 0.146 (0.140) ± 0.050 (0.046–0.284) 0.383 (0.353) ± 0.115 (0.218–0.616) Pups T3 16 0.009 (0.007) ± 0.005 (0.003–0.022) 0.382 (0.336) ± 0.191 (0.211–0.945) 0.437 (0.428) ± 0.094 (0.320–0.583) T4 12 0.008 (0.007) ± 0.003 (0.004–0.013) 0.439 (0.357) ± 0.192 (0.215–0.823) 0.535 (0.540) ± 0.100 (0.371–0.721) Hair * Mothers T2 21 2.36 (2.35) ± 0.63 (1.40–3.86) 0.24 (0.22) ± 0.06 (0.17–0.35) 1.29 (1.22) ± 0.37 (0.79–2.06) Pups T2 20 0.09 (0.06) ± 0.12 (0.02–0.53) 0.05 (0.05) ± 0.01 (0.03–0.08) 0.18 (0.16) ± 0.04 (0.14–0.27) n Pb Cd Blood Mothers T1 21 0.009 (0.004) ± 0.008 (<0.003–0.029) <LD T2 21 0.007 (0.005) ± 0.008 (<0.003–0.033) <LD Pups T1 21 0.007 (0.006) ± 0.003 (0.004–0.016) c <LD T2 21 0.012 (0.009) ± 0.008 (0.006–0.034) <LD T3 16 0.009 (0.008) ± 0.005 (0.004–0.021) <LD T4 12 0.012 (0.011) ± 0.005 (0.006–0.025) <LD Milk Mothers T1 21 0.022 (0.012) ± 0.027 (0.006–0.119) <LD T2 21 0.019 (0.014) ± 0.012 (0.007–0.060) <LD Blubber Mothers T1 21 0.069 (0.038) ± 0.100 (0.026–0.478) <LD T2 20 0.111 (0.068) ± 0.158 (0.037–0.759) <LD Pups T3 16 0.113 (0.079) ± 0.143 (0.034–0.638) <LD T4 12 0.073 (0.077) ± 0.013 (0.049–0.090) <LD Hair * Mothers T2 21 2.2 (1.7) ± 1.5 (0.6–6.0) 0.27 (0.27) ± 0.07 (0.15–0.42) Pups T2 20 0.64 (0.46) ± 0.51 (0.15–1.85) 0.02 (0.02) ± 0.01 (0.01–0.06) LD, limit of detection; n.d., not determined. an = 15. bn = 11. cn = 20. *Values expressed in dry weight basis.

Table4

Variationamongindividualsinelementconcentrationsinblood,milk,blubber,andhairofgreyseals.Coefficientsofvariationareexpressedinpercentage.

Blood Milk Blubber Hair

Mothers Pups Mothers Mothers Pups Mothers Pups

T1 T2 T1 T2 T3 T4 T1 T2 T1 T2 T3 T4 T2 T2 n 21 21 21 21 16 12 21 21 21 20 16 12 21 20 Ca 5 8 10 6 8 9 18 18 45 29 23 23 24 68 Fe 5 12 10 6 6 6 28 31 84 52 82 65 64 41 Zn 6 9 11 8 9 7 13 11 21 32 39 65 9 11 Cu 9 10 12 9 9 14 14 15 34 30 64 56 27 7 Se 28 30 23 49 31 34 47 22 28 18 Hg 56 53 42 54 46 37 29 46 69 51 V 61 58 47 51 55 52 84 77 127 120 60 38 27 127 Cr 53 47 21 28 36 43 64 94 39 34 50 44 23 22 Ni 57 67 16 30 22 19 29 20 Pb 88 109 47 66 48 43 122 64 144 143 127 18 67 79 Cd 27 52

T1,earlylactation;T2,latelactation;T3,earlypost-weaningfast;T4,middlepost-weaningfast.

Fe

0 200 400 600 800*

mg/kg (ww)Ca

0 20 40 60 80*

Zn

Se

Cu

0 1 2 3*

*

Hg

Pb

0.000 0.050 0.100 0.150*

Cr

V

0.000 0.001 0.002 0.003 Mothers Pups*

*

Blood

Fig.2. Elementconcentrationsinbloodofgreyseals.Comparisonoflevels(mean±SD;mg/kgww)betweenmothers(darkgreybars)andsucklingpups(lightgreybars)in earlylactation.Blacklineinbarsrepresentsthemedian.*indicatessignificantdifferencebetweenmaternalandpupvalues(p<0.05,Wilcoxonsigned-ranktests).

CaandVlevelsofpupblooddecreased,Pblevelsremained

sta-ble,whereastheotherelementlevelsincreased.Concentrations

didnotvaryoronlyslightlyduringthefirsthalfofpost-weaning

fast(Table5).

MilklevelsofCa,Fe,Zn,Cu,Se,andHgvariedbetweenthe begin-ningandtheendoflactation(Table5).LevelofSefellto48%of thevalueinearlylactation,whilelevel ofHgin milkincreased

from0.012to0.021mg/kgwwbetweenearlyand latelactation (Table5).Changesinthemilkwatercontentduringlactation(from approximately 40%in earlylactationto30% inlate lactation in this study) mayaffect element concentrations. However, when values in mg/kg wwwere convertedindry weightbasis, simi-lar trends asthose in Table5 were observedfor most oftrace elements.

Ca

0 1000 2000 3000*

mg/kg (dw)

Zn

Fe

0 50 100 150*

*

0Hg

Cu

Se

5 10 15*

*

*

0V

Pb

Ni

Cd

Cr

1 2 3 4*

*

Mothers

Pups

*

*

*

Hair & lanugo

Fig.3. Elementconcentrationsinhairofgreyseals.Comparisonoflevels(mean±SD;mg/kgdw)betweenmaternalhair(darkgreybars)andpuplanugo(lightgreybars). Blacklineinbarsrepresentsthemedian.*indicatessignificantdifferencebetweenmaternalandpupvalues(p≤0.001,Wilcoxonsigned-ranktests).

Table5

Comparisonsofelementconcentrationsthroughoutlactationanddevelopment:resultsofWilcoxonsigned-ranktests(p-value)andratios([Tx+1]/[Tx]×100)notedwhen concentrationsweresignificantlydifferent(n.s.,nonsignificant).

Blood Milk Blubber

Mothers Sucklingpups Pups Weanedpups Mothers Mothers Weanedpups

T2/T1 T2/T1 T3/T2 T4/T3 T2/T1 T2/T1 T4/T3 n 21 21 16 12 21 20 12 Ca n.s. p<0.001,119% p=0.011,96% n.s. p<0.001,144% p=0.002,177% n.s.b Fe p=0.033,96% p<0.001,91% p=0.001,107% p=0.004,105% p=0.002,77% p=0.001,442% n.s. Zn p=0.001,110% p=0.003,109% p=0.001,110% n.s. p=0.023,93% p<0.001,186% n.s. Cu n.s. p<0.001,138% p=0.001,112% n.s. p<0.001,119% p=0.001,152% n.s.b Se p<0.001,89% p=0.001,175% p<0.001,167% n.s. p<0.001,48% Hg p<0.001,128% p<0.001,52% p<0.001,120% p=0.002,91% p<0.001,174% V n.s. p=0.010,149% p=0.001,66% n.s. n.s. p=0.011,364% n.s. Cr n.s. n.s. p=0.020,132% n.s. n.s. p<0.001,222% n.s. Ni n.s.a p<0.001,148% n.s. Pb n.s. p<0.001,172%a n.s. p=0.034,143% n.s. p=0.003,212% n.s.

T1,earlylactation;T2,latelactation;T3,earlypost-weaningfast;T4,middlepost-weaningfast. an=20.

bn=11.

Maternal concentrations of all elements in whole blubber increasedbetweenthebeginningandtheendoflactation. Depend-ingontheelement,levelsinlate lactationroseto148–442%of thevalueinearlylactation(Table5).Resultsintheblubber sub-samplesofgreysealmothersshowedthatconcentrationsincreased betweenearlyand late lactationboth in inner and outer blub-ber.However,magnitudeofincreasewasmoreimportantininner blubber forCa, Fe,Zn, and Cu.Consequently, concentrations of Ca,Fe, Zn, and Cuin late lactation were greater in inner than inouterblubber (Table6),whereas concentrationsof V, Cr,Ni, and Pb in late lactation were similar in inner and outer blub-ber(p>0.05,Wilcoxonsigned-ranktests).Incontrast,therewas nochange of concentration in blubber of weaned pups during theearlypost-weaningfastperiod(Table5).LevelsofCrandNi inblubberweremuchgreater inweanedpupsthaninmothers (Table3).

3.4. Relationshipsbetweenelements,tissues,andbiometric parameters

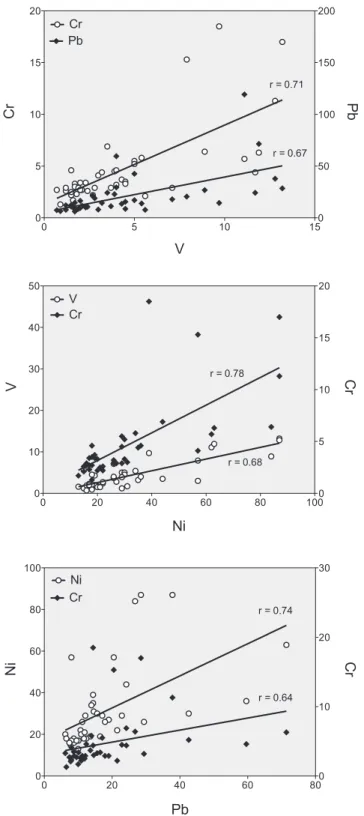

Correlationsbetweentraceelementsinthedifferenttissuesare giveninTable7.Inblood,onlyFeandZnconcentrationswere posi-tivelycorrelated.Interestingly,Ni,Cr,Pb,andVshowedasignificant relationshipwitheach other,both inmilkandblubber (Table7 andFig.4 for milk). Somecorrelations wereobservedbetween thedifferenttissues.OnlyHgandSeshoweda significant posi-tiverelationshipbetweenhairandbloodlevelsinmothers(r=0.66, p=0.001andr=0.51,p=0.017,respectively;Spearman’srank cor-relationcoefficient).Bloodlevelsofelementswerenotsignificantly correlatedtolevelsinmaternalblubber,exceptforVinearly lac-tation(r=0.59,p=0.004;Spearman’srankcorrelationcoefficient). ConcentrationsofSeinmaternalbloodwerepositivelycorrelated withconcentrationsofSeinmilk(r=0.62and0.61inearlyand late lactation, respectively, for both p=0.003; Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient). Concentrations of other elementswere notsignificantlycorrelatedbetweenmaternalbloodandmilk,or onlyslightly.Levels ofZn, Se,Hg,Pb,and Vinpup bloodwere

correlated to maternal blood levels in early lactation (r=0.53, r=0.71,r=0.78,r=0.63,r=0.59,respectively,for allcorrelations p≤0.01;Spearman’srankcorrelationcoefficient).Cu,Se,Pb,andV showedaslightlypositiverelationshipbetweenlanugoandblood levelsinpups(forallr=0.5andp<0.05;Spearman’srank correla-tioncoefficient),andHgshowedahighlysignificantrelationship betweenlevelsinthesetissues(r=0.89andp<0.001;Spearman’s rankcorrelationcoefficient).

Thebiometricparameters(i.e.,mass,length,andaxialgirth)of greysealmothersandpupswerenotsignificantlycorrelatedwith element concentrationsin thedifferenttissues (p>0.05; Spear-man’srankcorrelationcoefficient),oronlyslightly(r>−0.50for FeinblubberinearlylactationorforHginmilkinlatelactation, p<0.05forall;Spearman’srankcorrelationcoefficient).Element concentrationsinblood,blubber,andlanugoinpupsdidnotdiffer betweenmalesandfemales(forallp>0.05,Mann–Whitneytests). Relationshipsbetweenelementconcentrationsandlipidcontentin thedifferenttissues(blood,blubber,andmilk;analysesinVanden Bergheetal.,2012)werealsoassessedinmothersandpups.Only concentrationsofCaandSewerecorrelatedtothelipidcontentin milk,inearlylactation(r=0.67,p=0.001andr=−0.58,p=0.007, respectively;Spearman’srankcorrelationcoefficient).

4. Discussion

4.1. TraceelementlevelsinUKgreyseals 4.1.1. Bloodlevels

BloodlevelsofCa,Fe,Zn,andCufoundinlactatinggreyseals fromtheIsleofMaywerecomparabletothosereportedin stud-iesofotherphocidspecies(Barajetal.,2001;Grieseletal.,2008; Kakuschkeetal.,2006).Asessentialelementsinvolvedinmany functions,bloodconcentrationsofCa,Fe,Zn,andCuwere home-ostaticallycontrolledandtheirconcentrationsvariedlittleamong allanimalsofthisstudy.Incontrast,bloodSelevelinthisstudy wasthegreatestvaluesreportedinbloodoffree-rangingphocids (Grieseletal.,2008;Habranetal.,2011).Aswithanyessentialtrace Table6

ComparisonsofCa,Fe,Zn,andCuconcentrationsbetweeninnerandoutermaternalblubberinlatelactation(Wilcoxonsigned-ranktests).

n Innera Outera p-value

Ca 20 29(29)±11(12–50) 21(20)±7(11–33) p=0.002

Fe 20 87(84)±54(10–201) 44(43)±22(8–84) p=0.001

Zn 20 2.8(2.8)±1.2(1.1–5.1) 1.7(1.6)±0.5(1.2–3.3) p<0.001

Cu 20 0.285(0.286)±0.120(0.117–0.518) 0.180(0.186)±0.042(0.116–0.266) p<0.001

Table7

Correlationsbetweenelementsinthedifferenttissuesofgreyseals(doubleunderlined:p<0.001;underlined:p<0.01;notunderlined:p<0.05;Spearman’srankcorrelation). Thedifferentcaptureswerecombinedforanalysis.

Blood Milk Blubberofmothers Blubberofweanedpups Hair Lanugo

Ca +V +Ni +Fe

Fe +Zn +Ca,+V,+Ni

Zn +Fe +Cu,+Ni,+Pb

Cu +Zn,+Ni,+Pb −Cr

Se −Ni

V +Cr,+Ni,+Pb +Cr,+Ni,+Pb +Ca −Pb +Fe,+Ni

Cr +V,+Ni,+Pb +V,+Ni,+Pb +Ni −Cu,+Ni

Ni +V,+Cr,+Pb +Zn,+Cu,+V,+Cr,+Pb +Cr +Ca,−Se,+Cr,+Cd +Fe,+V

Cd +Ni,+Pb

Pb +V,+Cr,+Ni +Zn,+Cu,+V,+Ni,+Cr −V,+Cd

element,Secanbecometoxicaboveacertainthreshold.Although

marinemammalsappeartobelesssensitivetodietaryorganicSe

exposure,littleinformationexistsaboutSetoxicityintheseanimals

(Janzetal.,2010).Suchlevelsinpigshaveshownreduced

repro-ductiveperformances(KimandMahan,2001).Overall,bloodlevels ofothertraceelements(V,Pb,Cr,Ni,andCd)ingreysealswerein thesamerangeasconcentrationsreportedinphocids(Barajetal., 2001;Grieseletal.,2008;Kakuschkeetal.,2006).Nevertheless, thereweresomedifferencesinPbandCrlevelsincomparisonwith othersealsfromtheNorthSea.Greysealsfromthisstudyshowed 10foldhigherPblevelsand5–8foldlowerCrlevelsthanthoseseen fromotherphocidsfromtheNorthSea(inharbourseals,Griesel etal.,2008;inagreyseal,Kakuschkeetal.,2006).Mercuryinblood ofadultfemalesshowedthegreatestconcentrationsofthe non-essentialmetalsinthisstudy.However,theseHgconcentrations werelessthanthoseencounteredforphocidselsewhere(Brookens etal.,2007;Dasetal.,2008;Habranetal.,2011).BloodHglevels infree-rangingharboursealsfromtheNorthSea(Dasetal.,2008) weretwiceashighasthoseinthepresentstudy,reflectingthelower HgexposureofgreysealsfromtheIsleofMay.Asexpected, poten-tiallytoxicelements(e.g.,V,Pb,andHg)showedwidevariationsin concentrationsforallanimalsstudied(Table4).

4.1.2. Hairlevels

Haircontainedagreaterproportionofnon-essentialmetalsin comparisonwithblood(Fig.A1).Therefore,annualmoults repre-sentasignificanteliminationofthesenon-essentialmetalsforboth sexes.Calcium wasthemajorelementpresentinmaternalhair, followedbyZnandFe,thenHgwith7.7mg/kgdw.Althoughan importantburdenofHgseemstobeeliminatedinhair,thisannual losswouldrepresentapproximately17%oftypicaltotalbody bur-densof Hg(Agusaet al.,2011).Levels ofHgwere inthesame rangeasvaluesobservedinhairofphocidselsewhere(Brookens etal.,2007;Grayetal.,2008;Medvedevetal.,1997),butmuchless thanharboursealsfromGermany(7.7mg/kgdwingreysealsvs. 33.5mg/kgdwinharbourseals,Wenzeletal.,1993).Incontrast, Pblevelsinmaternalhairweregreater(2.2mg/kgdw)thanlevels reportedinmostphocids(0–1.6mg/kgdw,Andradeetal.,2007; Medvedevetal.,1997;Wenzeletal.,1993;Yamamotoetal.,1987). MaternalhairalsocontainedhighlevelofV(2.4mg/kg)in compar-isonwithblood,milk,orblubbervalues.Infact,hairappearstobe theprimarysiteofaccumulationofVinphocids:45%ofthetotal Vbodyburdenisaccumulatedinhair(Agusaetal.,2011).Other traceelement(Zn,Cu,Se,Cr,Cd,andPb)contentsinphocidhair representbetween10%and18%ofthetotalbodyburdens(Agusa etal.,2011).

4.1.3. Blubberlevels

Allelements,exceptCdandSe,werefoundinmaternal blub-ber.Asmallamountofbloodwassometimespresentinblubber

biopsies due to associated vascularization.Therefore some ele-ments from blood, especially Fe, may have impacted levels in blubber.ThiscouldexplainthegreatvariabilityinFelevelsin blub-ber.SubstantialamountsofNi,Cr,andPbwerefoundinblubber (Fig.A1).Ingeneral,Ni,Cr,Pb,andVseemtobemoredistributed inlipophilictissue,likeblubberormilk,thantheothertrace ele-ments.Agusaetal.(2011)showedthat11.5%,26%,and45%oftotal burdensofV,Cr,andPb,respectively,werefoundintheblubber, whileonlybetween0.5%and3.5%ofthetotalburdensofZn,Cu,Se, Cd,andHgweredistributedinthattissue.

4.2. Maternaltransferoftraceelementsduringgestationand lactation

4.2.1. Placentaltransfer

Lanugoappearsasagoodindicatoroftheplacentaltransferof elementstooffspringsinceitreflectstheincorporationofelements duringthefoetalperiod.Itgrowsduringdevelopmentofthefoetus anditisshedaroundweaning.Resultsofthisstudyshowedthat allassayedelements,includingNiandCd,wereaccumulatedin greysealsandweretransferredtooffspringthroughtheplacenta. Lanugoseemstobeanimportantsiteofaccumulationfortrace ele-ments.Apartofthenon-essentialmetalscanbealreadyeliminated fromearlystagesofdevelopment,asshownforHgwith4.6mg/kg dwinthegreyseallanugo.

Levels inlanugowerevery muchgreaterthan inpup blood. Therefore, lanugoappearsmoreusefulthanblood todetectthe placental transfer of minor traceelements, suchas Ni and Cd. Moreover,pupbloodinearlylactationwascollectedat2–4days postpartum since it was not possible tocollect it immediately after birth for animal care reasons and logistical reasons. This meansthatpup bloodlevelsmeasuredinearlylactationreflect both theplacental transferand theintakefromthemilkduring thefirstdaysoflactation.Nevertheless,pupbloodprovides impor-tant indications about the levelsof elementscirculating in the body,whichcanaffectpuporgansandsystemsinearlystagesof development.

Calcium,Zn,Fe,andCuvaluesinpupbloodwerecloseto mater-nalvaluesinearlylactation(Fig.2).Forthesemetals,itisbelieved that thenewborn’s needsare metmainlyby reserves accumu-latedduring foetaldevelopment,especiallyduring thelastpart ofpregnancy (Dorea,2000).In contrast,a fairlylimitedtransfer ofSethroughtheplacentawasobservedingreyseals,withpup levels reaching 38% of the maternal blood value. Despite their verylowbloodlevels,Pb,Cr,andVappearefficientlytransferred frommothertooffspringwith,respectively,100%,144%,and177% of thematernalmetal valueat birth(at2–4days postpartum). TransferofHgwaslowerbutneverthelessconsistentsincepups alreadyshowedmorethan50%ofthematernalbloodvalueinearly lactation.

0 5 10 15 0 5 10 15 20 0 50 100 150 200 Cr Pb r = 0.67 r = 0.71

V

Cr

Pb

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 10 20 30 40 50 0 5 10 15 20 V Cr r = 0.68 r = 0.78Ni

V

Cr

0 20 40 60 80 0 20 40 60 80 100 0 10 20 30 Ni Cr r = 0.64 r = 0.74Pb

Ni

Cr

Fig.4. RelationshipsbetweenV,Cr,Ni,andPbinmilkofgreyseals. Concentra-tionsareexpressedin!g/kgww(forallcorrelationsp<0.001,Spearman’srank correlationcoefficient).

4.2.2. Lactationaltransfer

Overall,themineralcontentingreysealmilkappearsquitehigh incomparisonwiththeoneinterrestrialmammalmilk.Thehigh proteincontentinpinnipedmilk,beingamongthehighestofany mammal(approximately10%,Davisetal.,1995)maycontribute tothehighmineralcontentinmilksincemanymetalsareusually boundtoproteins.

Calcium level in milkwas similar tothat in other pinniped milk(around700mg/kgww,Oftedaletal.,1987),higherthanin

humanmilk(252mg/l,Dorea,1999)andlowerthanincowmilk (1100mg/l, USDA,2007).Calcium is a majorelement for min-eralizationof bonematrix inoffspring andis mostlypresentin milkcomplexedwithproteins,caseins,inmicelles.Surprisingly, pinnipedshavemuchlesscalciuminmilkthanwouldbepredicted basedontheirhighcaseincontent(Jenness,1979).

Adequate Fe intake is essential for optimal growth, haematopoiesisandcognitivedevelopmentinoffspring(Kelleher andLönnerdal,2005).GreysealsshowedsimilarFelevelsinblood, butverymuchgreaterFelevelsinmilk(∼20mg/kgww)thanother terrestrialmammals(<1mg/linhumansandruminants,Anderson, 1992;4–10mg/linratsanddogs,Lönnerdaletal.,1981).Asvery littleinformationexistsabouttraceelementsin milkofmarine mammals, levelshave been compared withthose in terrestrial mammalswhereanydatawasavailable.Threeproteinsinmilk havebeenreportedtobindFeinterrestrialspecies:lactoferrin, transferrin, and casein (Lönnerdalet al., 1981). Grey seal milk is devoid of lactoferrin (Conesa et al., 2008). Casein might be usedasiron-bindingproteininmilkasdosomespecies(i.e.,rats and cows),which havenooronly low levelsoflactoferrinand transferrininmilk(Hegenaueretal.,1979;LohandKaldor,1973). Thevery largeamounts ofcaseinmicellesof thepinniped milk (Oftedal,1993)mightcontributetothehighlevelofFedetected in grey seal milk. Caseins could also bind partially Zn and Cu (Lönnerdaletal.,1981).AlthoughFelevelsinmaternalbloodand milkofgreysealsdeclinedthroughoutthecourseoflactation,they werenotcorrelatedbetweenthem.Asreportedinothermammals (Lönnerdalet al., 1981),Fe transport via mammary gland is a tightlyregulatedprocessthusensuringappropriateFetransferto theneonate(KelleherandLönnerdal,2005)

LevelsofCuandZningreysealmilkwereinthesamerangeas valuesfoundinterrestrialmammals(Anderson,1992;Lönnerdal etal.,1981).Copperplaysanessentialroleasacofactorforenzymes that generate cellular energy, cross-link connective tissue and mobilizecellulariron(Linderetal.,1998).Zincisanutrientrequired formany proteinsinvolvedinDNAsynthesis,proteinsynthesis, mitosisandcelldivision.AdequateZnsupplyisparticularly impor-tantduringtheperiodsofrapidneonatalgrowthanddevelopment (KelleherandLönnerdal,2005).CopperandZnlevelsincreasedin pupbloodthroughoutthecourseoflactation,likelylinkedtothe substantialCuandZnuptakefromthemilk.LikeCaandFe, mecha-nismsgoverningthetransferofCuandZnfrombloodtomilkarenot fullyunderstood,buttheydonotseemtodependonmaternalmetal reserves(Dorea,2000).Littlerelationshipbetweenbloodlevelsand milklevelsoftheseelementswasobservedingreysealmothers. Thehighfatcontentofpinnipedmilkmightalsocontributetohigh levelsofFe,Zn,andCudetectedingreysealmilk.Indeed,itappears thatsignificantportionsofFe,Zn,andCuinhumanandcowmilk arelocalizedinthemilkfatfraction(Lönnerdaletal.,1981). How-ever,norelationshipwiththemilklipidcontentwasobservedfor theseelementsinthepresentstudy.

Seleniumisoneofthemostimportantantioxidantsinmilk.Itis essentialforhealth,playingaroleintheimmuneandantioxidant systemsandinDNAsynthesisandDNArepair(Haugetal.,2007). MilkingreysealscontainedalotofSe,especiallyinearlylactation (around900!g/kg).Thisvaluewassimilartotheleveldetected innorthernelephant sealmilk(Habranetal.,2011),and itwas muchgreaterthanvalues foundinhuman(13–33!g/l, Dumont etal.,2006)orcow(11–37!g/l,Haugetal.,2007).Asreportedin northernelephantseals(Habranetal.,2011),thehighSeuptake frommilkincreasedpuplevelduringsuckling,despitedecreasing milkleveloverlactation.Itseemsthattheneonate’sneedsinSe aremetmainlybyreservesaccumulatedduringsucklinginphocids. Unlikepreviouselements(Ca,Fe,Cu,andZn),Selevelinmilkseems todependonitsmaternalreservessinceitwaspositivelycorrelated withmaternalbloodconcentrations.

GreysealmilkcontainedHg,Pb,V,Ni,andCr,andthe concentra-tionsweregreaterthaninblood,exceptforHg.Interestingly,Pb,V, Ni,andCrshowedasignificantpositiverelationshipwitheachother (Fig.4),suggestingasimilarmobilizationofthesemetalsthrough themilk.Incontrastwiththeplacentaltransferdetectedinlanugo, itappearsthatCdwasnottransferredthroughthemammarygland intothemilk.Likeinblood,Pb,V,Ni,andCrinmilkappearless tightlyregulatedthroughthemammaryglandthanCa,Cu,andZn, asevidencebytheircoefficientsofvariation(Table4).

4.3. Variationsintissuesthroughoutlactationandpost-weaning fast

Resultsshowedthattheperiodassociatedtomilkproduction, fasting,orsucklingcouldaffectelementlevelsintissuesofgrey sealmothersandpups.Bloodandmilkconcentrationsincreased ordecreasedoverthecourseoflactation,dependingonthe ele-mentinvestigated(Table5).Interestingly,thesamedynamicsof HgandSeduringlactation,includingsimilartransferratiosatbirth andsimilarvariationsinconcentrations,wasfoundinbloodand milkofnorthern elephantseals(Habranet al.,2011).Each ele-mentseemstohaveitsowndynamicsduringthisperiod,andit isnotpossibletohighlightageneralpatternforthemobilization ofelements.Nevertheless,theseresultsshowthatconcentrations intissuescanvaryrapidlyduringintensephysiologicalchanges. Therefore,theseprocesses couldleadtoa biasedassessmentof traceelementcontaminationinmarinemammalswhendifferent populationsordifferentspeciesarecompared.Moreover, impor-tantvariationsintraceelementconcentrationsinthebloodstream couldcausedamagesindiverseorgansorsystems,especiallyduring growingofoffspring.

Duringlactation,adultfemalesfastanddependentirelyontheir bodyfat,mainlyfromtheblubber,tomaintaintheirmetabolism andtoproducemilk.Concentrationsofallelementsinthematernal blubberincreasedthroughoutlactationwiththereductionof blub-berthickness(Table5),suggestingalessefficientmobilizationof elementsfromblubberthantriglycerides,thedominantlipidtype (Hendersonetal.,1994).However,elementspotentiallyassociated tolipidreservesseemtobenot mobilizedallinthesame way. Atthebeginningoflactation,elementsweredistributed homoge-neouslyacrossthefulldepthoftheblubberlayer(nodifference betweeninnerandouterlayers).Duringlactation,concentrations ofCa,Fe,Zn,andCuincreasedmoreintheinnerblubberandbecame significantlygreaterininner thaninouterblubberinlate lacta-tion(Table6).Incontrast,concentrationsofV,Cr,Ni,andPbalso increasedduringlactationbutremainedsimilarbetweeninnerand outerblubber.Fattyacidsaremainlymobilizedfromtheinner blub-berlayerduringthisperiod,whiletheouterpartremainsmore stable(Strandbergetal.,2008).Indeed,forthegreysealsofthe presentstudy,innerblubberlost18%ofitslipidcontent,whileouter blubberlost9%duringlactation(analysesinVandenBergheetal., 2012).ItseemsthatV,Cr,Ni,andPbwouldbelessretainedintothe innerblubberthanCa,Fe,Zn,andCu.Moreover,significant rela-tionshipsbetweenV,Cr,Ni,andPblevelswereobservedbothin blubberandmilksuggestingthatthese4elementsweremobilized throughsimilardynamicsfromtheblubbertothemilk.

Surprisingly,nochangeinblubberlevelswasobservedinpups duringtheirpost-weaningdevelopment,whereas theyalsofast dependingontheirreservesaccumulatedduringlactation. Differ-enceinthefatutilizationbetweenmothersandpupsmightaffect traceelementmobilizationinblubber,givenapproximately25%of bodyfatcontentisusedduringpost-weaningfastingreysealpups (Bennettetal.,2007),whileapproximately60%duringlactationin greysealfemales(Mellishetal.,1999).Interestingly,weanedpups showedveryhighlevelsofCrandNiintheirblubber–higherthanin maternalblubber–whereastheirbloodlevelswerelowandCrand

Nimilkintakewasquiteweak.Thesourceofthesemetals(placental orlactationaltransfer)remainsunclear,sincepupsarebornwith averythinblubberlayer,andCrandNiuptakefrommilkappears quitelow.Inanycase,animportantpartoftheCrandNicontent ingreysealsseemstobeaccumulatedduringtheirearlystagesof development.

5. Conclusions

Lanugoanalysesingreysealsallowedtohighlighttheexistence ofaplacentaltransfertooffspringofallelementsinvestigatedin thisstudy.Moreover,resultsinlanugoshowedthatapartofthe non-essentialmetalscouldbealreadyeliminatedfromthefoetal development.Amaternaltransferthroughthemilkhasalsobeen observedforallelements,exceptforCd.Somemetals,suchasHg, weretransferredtooffspringmainlythroughtheplacentaduring gestationandtoalesserextentduringlactation,andinverselyfor otherelementslikeSe.Theplacentalandmammarybarriersagainst non-essentialmetaltransfertooffspringseemedtobeabsentor weakingreyseals.TherewashoweveranexceptionforCdwhich wasnotpresentintothemilk.Inadditiontotheplacentaltransfer, theimportantdailyingestionofcontaminatedmilkcouldleadto adverseeffectsonhealthofpupsfromtheearlystagesof develop-ment.

Furthermore,thisstudyalsoshowedthatelement concentra-tionsintissues(i.e.,bloodandblubber)couldchangerapidlyover thelactationperiod.Suchphysiologicalprocessesandtheireffects mustbetakenintoconsiderationwheninterpretingtraceelement concentrationsintheframeworkofbiomonitoring.Moreover, fur-thertoxicologicalstudiesneedtounderstandtheimpactthatthese importantfluctuationsinconcentrationsmayexertonhealthof bothadultsandoffspring.Tothebestofourknowledge,thisstudy representsthefirstassessmentofthelevelsoftraceelement con-tamination in this grey seal population of the North Sea. This populationseemslowerexposedtoHg,buthigherexposedtoPb thanotherphocidpopulations,notablyfromtheNorthSea. Acknowledgements

TheauthorsthankS.Moss,P.Reimann,C.Morris,W.Paterson, A.Hall,andN.Hansonfortheirassistancewithsamplecollection ontheIsleofMay.TheauthorsarealsogratefultoR.Biondoforhis technicalassistance.K.D.isaF.R.S.-FNRSResearchAssociate.S.H. isaF.R.S.-FNRSResearchfellow.ThisstudywassupportedbyNSF grant#0213095andbyFRFCgrant#2.4502.07(F.R.S.-FNRS).This paperisMAREpublication235.

AppendixA. Supplementarydata

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.aquatox.2012.08.011.

References

Agusa,T.,Yasugi,S.,Iida,A.,Ikemoto,T.,Anan,Y.,Kuiken,T.,Osterhaus,A.D.M.E., Tanabe, S., Iwata, H., 2011. Accumulation features of trace elements in mass-strandedharborseals(Phocavitulina)intheNorthSeacoastin2002: thebodydistributionandassociationwithgrowthandnutritionstatus.Marine PollutionBulletin62,963–975.

AMAP,2005.AMAPAssessment2002:HeavyMetalsintheArctic.ArcticMonitoring andAssessmentProgramme(AMAP),Oslo,Norway.xvi+265pp.(firstpublished aselectronicdocumentin2004).

Anderson,R.R.,1992.Comparisonoftraceelementsinmilkoffourspecies.Journal ofDairyScience75,3050–3055.

Andrade,S.,Carlini,A.R.,Vodopivez,C.,Poljak,S.,2007.Heavymetalsinmoltedfur ofthesouthernelephantsealMiroungaleonina.MarinePollutionBulletin54, 602–605.

Baraj,B.,Bianchini,A.,Niencheski,L.F.H.,Campos,C.C.R.,Martinez,P.E.,Robaldo, R.B.,Muelbert,M.M.C.,Colares,E.P.,Zarzur,S.,2001.TheperformanceofZeiss GFAAS-5instrumentonthedeterminationoftracemetalsinwholeblood sam-plesofsouthernelephantseals(Miroungaleonina)fromAntarctica.Fresenius EnvironmentBulletin10,859–862.

Bennett,K.A.,Speakman,J.R.,Moss,S.E.W.,Pomeroy,P.,Fedak,M.A.,2007.Effects ofmassandbodycompositiononfastingfuelutilisationingreysealpups (HalichoerusgrypusFabricius):anexperimentalstudyusingsupplementary feed-ing.JournalofExperimentalBiology210,3043–3053.

Bossart,G.D.,2006.Marinemammalsassentinelspeciesforoceansandhuman health.Oceanography19,134–137.

Brookens,T.J.,Harvey,J.T.,O’Hara,T.M.,2007.Traceelementconcentrationsinthe Pacificharborseal(Phocavitulinarichardii)incentralandnorthernCalifornia. ScienceoftheTotalEnvironment372,676–692.

Bryan,C.E.,Christopher,S.J.,Balmer,B.C.,Wells,R.S.,2007.Establishingbaseline lev-elsoftraceelementsinbloodandskinofbottlenosedolphinsinSarasotaBay, Florida:implicationsfornon-invasivemonitoring.ScienceoftheTotal Environ-ment388,325–342.

Bustamante,P.,Garrigue,C.,Breau,L.,Caurant,F.,Dabin,W.,Greaves,J., Dode-mont,R.,2003.Traceelementsintwoodontocetespecies(Kogiabrevicepsand Globicephalamacrorhynchus)strandedinNewCaledonia(SouthPacific). Envi-ronmentalPollution124,263–271.

Chatt,A.,Katz,S.,1988.HairAnalysis,ApplicationsintheBiomedicaland Environ-mentalScience.VCHPublishers,NewYork.

Conesa,C.,Sánchez,L.,Rota,C.,Pérez,M.a.-D.,Calvo,M.,Farnaud,S.,Evans,R.W., 2008.Isolationoflactoferrinfrommilkofdifferentspecies:calorimetricand antimicrobialstudies.ComparativeBiochemistryandPhysiology,PartB150, 131–139.

Das,K.,Debacker,V.,Pillet,S.,Bouquegneau,J.M.,2003.Heavymetalsinmarine mammals.In:Vos,J.G.,Bossart,G.D.,Fournier,M.,O’Shea,T.J.(Eds.),Toxicology ofMarineMammals.Taylor&Francis,London,pp.135–167.

Das,K.,Siebert,U.,Gillet,A.,Dupont,A.,Di-Poï,C.,Fonfara,S.,Mazzucchelli,G.,De Pauw,E.,DePauw-Gillet,M.-C.,2008.Mercuryimmunetoxicityinharbourseals: linkstoinvitrotoxicity.EnvironmentalHealth7,1–17.

Davis,T.A.,Nguyen,H.V.,Costa,D.P.,Reeds,P.J.,1995.Aminoacidcompositionof pinnipedmilk.ComparativeBiochemistryandPhysiologyB:Comparative Bio-chemistry110,633–639.

Debier,C.,Chalon,C.,LeBoeuf,B.J.,deTillesse,T.,Larondelle,Y.,Thome,J.P.,2006. MobilizationofPCBsfromblubbertobloodinnorthernelephantseals(Mirounga angustirostris)duringthepost-weaningfast.AquaticToxicology80,149–157. Debier,C.,Pomeroy,P.P.,Dupont,C.,Joiris,C.,Comblin,V.,LeBoulenge,E.,

Laron-delle,Y.,Thome,J.P.,2003a.DynamicsofPCBtransferfrommothertopupduring lactationinUKgreysealsHalichoerusgrypus:differencesinPCBprofilebetween compartmentsoftransferandchangesduringthelactationperiod.Marine Ecol-ogyProgressSeries247,249–256.

Debier,C.,Pomeroy,P.P.,Dupont,C.,Joiris,C.,Comblin,V.,LeBoulenge,E.,Larondelle, Y.,Thome,J.P.,2003b.QuantitativedynamicsofPCBtransferfrommothertopup duringlactationinUKgreysealsHalichoerusgrypus.MarineEcologyProgress Series247,237–248.

Dorea,J.G.,1999.Calciumandphosphorusinhumanmilk.NutritionResearch19, 709–739.

Dorea,J.G.,2000.Ironandcopperinhumanmilk.Nutrition16,209–220. Dumont,E.,Vanhaecke,F.,Cornelis,R.,2006.Seleniumspeciationfromfoodsource

tometabolites:acriticalreview.AnalyticalandBioanalyticalChemistry385, 1304–1323.

Fedak,M.A.,Anderson,S.S.,1982.Theenergeticsoflactation:accurate measure-mentsfromalargewildmammal,thegreyseal(Halichoerusgrypus).Journalof Zoology198,473–479.

Godwin,H.A.,2001.Thebiologicalchemistryoflead.CurrentOpinioninChemical Biology5,223–227.

Gray,R.,Canfield,P.,Rogers,T.,2008.Traceelementanalysisintheserumandhair ofAntarcticleopardseal,Hydrurgaleptonyx,andWeddellseal,Leptonychotes weddellii.ScienceoftheTotalEnvironment399,202–215.

Griesel,S.,Kakuschke,A.,Siebert,U.,Prange,A.,2008.Traceelementconcentrations inbloodofharborseals(Phocavitulina)fromtheWaddenSea.Scienceofthe TotalEnvironment392,313–323.

Habran,S.,Debier,C.,Crocker,D.E.,Houser,D.S.,Das,K.,2011.Blooddynamicsof mercuryandseleniuminnorthernelephantsealsduringthelactationperiod. EnvironmentalPollution159,2523–2529.

Haug,A.,Høstmark,A.T.,Harstad,O.M.,2007.Bovinemilkinhumannutrition—a review.LipidsinHealthandDisease6(25).

Hegenauer,J.,Saltman,P.,Ludwig,D.,Ripley,L.,Ley,A.,1979.Iron-supplemented cowmilk.Identificationandspectralpropertiesofironboundtocaseinmicelles. JournalofAgriculturalandFoodChemistry27,1294–1301.

Henderson,R.J.,Kalogeropoulos,N.,Alexis,M.N.,1994.Thelipidcompositionof selectedtissuesfromaMediterraneanmonkseal,Monachusmonachus.Lipids 29,577–582.

Janz,D.M.,DeForest,D.K.,Brooks,M.L.,Chapman,P.M.,Gilron,G.,Hoff,D.,Hopkins, W.A.,McIntyre,D.O.,Mebane,C.A.,Palace,V.P.,Skorupa,J.P.,Wayland,M.,2010. Seleniumtoxicitytoaquaticorganisms.In:Chapman,P.M.,Adams,W.J.,Delos, C.G.,Luoma,S.N.,Maher,W.A.,Ohlendorf,H.M.,Presser,T.S.,Shaw,D.P.(Eds.), EcologicalAssessmentofSeleniumintheAquaticEnvironment.,1sted.CRC Press,Pensacola,FL,pp.141–232.

Jenness,R.,1979.Comparativeaspectsofmilkproteins.JournalofDairyResearch 46,197–210.

Kakuschke,A.,Valentine-Thon,E.,Fonfara,S.,Griesel,S.,Siebert,U.,Prange,A.,2006. Metalsensitivityofmarinemammals:acasestudyofagrayseal(Halichoerus grypus).MarineMammalScience22,985–996.

Kelleher,S.L.,Lönnerdal,B.,2005.Molecularregulationofmilktracemineral homeo-stasis.MolecularAspectsofMedicine26,328–339.

Kim,Y.Y.,Mahan,D.C.,2001.Prolongedfeedingofhighdietarylevelsoforganicand inorganicseleniumtogiltsfrom25kgbodyweightthroughoneparity.Journal ofAnimalScience79,956–966.

Linder,M.C.,Wooten,L.,Cerveza,P.,Cotton,S.,Shulze,R.,Lomeli,N.,1998.Copper transport.AmericanJournalofClinicalNutrition67,965S–971S.

Loh,T.T.,Kaldor,I.,1973.Ironinmilkandmilkfractionsoflactatingrats,rabbitsand quokkas.ComparativeBiochemistryandPhysiologyPartB44,337–346. Lönnerdal,B.,Keen,C.L.,Hurley,L.S.,1981.Iron,copper,zincandmanganeseinmilk.

AnnualReviewofNutrition1,149–174.

Medvedev,N.,Panichev,N.,Hyvärinen,H.,1997.Levelsofheavymetalsinseals ofLakeLadogaandtheWhiteSea.ScienceoftheTotalEnvironment206, 95–105.

Mellish,J.A.E.,Iverson,S.J.,Bowen,W.D.,1999.Variationinmilkproductionand lac-tationperformanceingreysealsandconsequencesforpupgrowthandweaning characteristics.PhysiologicalandBiochemicalZoology72,677–690. Oftedal,O.T.,1993.Theadaptationofmilksecretiontotheconstraintsoffastingin

bears,seals,andbaleenwhales.JournalofDairyScience76,3234–3246. Oftedal,O.T.,Boness,D.J.,Tedman,R.A.,1987.Thebehavior,physiologyandanatomy

oflactationinthepinnipedia.In:Genoways,H.H.(Ed.),CurrentMammalogy., 1sted.Springer,NewYork,pp.175–245.

OSPAR,2010.QualityStatusReport2010.OSPARComission,London.

Pomeroy,P.,Fedak,M.,Rothery,P.,Anderson,S.,1999.Consequencesofmaternal sizeforreproductiveexpenditureandpuppingsuccessofgreysealsatNorth Rona,Scotland.TheJournalofAnimalEcology68,235–253.

Pomeroy, P.P., Green, N., Hall, J.A.,Walton, M.,Jones, K., Harwood, J.,1996. Congener-specificexposureofgreyseal(Halichoerusgrypus)pupsto chlori-natedbiphenylsduringlactation.CanadianJournalofFisheryandAquaculture Sciences53,1526–1534.

Reilly,J.J.,1991.Adaptationstoprolongedfastinginfree-livingweanedgreyseal pups.AmericanJournalofPhysiology260,267–272.

Strandberg,U.,Kakela,A.,Lydersen,C.,Kovacs,K.M.,Grahl-Nielsen,O.,Hyvarinen, H.,Kakela,R.,2008.Stratification,composition,andfunctionofmarine mam-malblubber:Theecologyoffattyacidsinmarinemammals.Physiologicaland BiochemicalZoology81,473–485.

USDA, National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/Data/%5D.(accessed03.09.07). VandenBerghe,M.,Mat,A.,Arriola,A.,Polain,S.,Stekke,V.,Thomé,J.-P.,Gaspart,

F.,Pomeroy,P.,Larondelle,Y.,Debier,C.,2010.Relationshipsbetweenvitamin AandPCBsingreysealmothersandpupsduringlactation.Environmental Pol-lution158,1570–1575.

VandenBerghe,M.,Weijs,L.,Habran,S.,Das,K.,Bugli,C.,Rees,J.-F.,Pomeroy,P., Covaci,A.,Debier,C.,2012.Selectivetransferofpersistentorganicpollutants andtheirmetabolitesingreysealsduringlactation.EnvironmentInternational 46,6–15.

Wagemann,R.,Stewart,R.E.A.,Lockhart,W.L.,Stewart,B.E.,Povoledo,M.,1988. Tracemetalsandmethylmercury:associationsandtransferinharpseal(Phoca groenlandica)mothersandtheirpups.MarineMammalScience4,339–355. Wenzel,C.,Adelung,D.,Kruse,H.,Wassermann,O.,1993.Tracemetalaccumulation

inhairandskinoftheharbourseal,Phocavitulina.MarinePollutionBulletin26, 152–155.

Wolfe,M.F.,Schwarzbach,S.,Sulaiman,R.A.,1998.Effectsofmercuryonwildlife:a comprehensivereview.EnvironmentalToxicologyandChemistry17,146–160. Yamamoto,Y.,Honda,K.,Hidaka,H.,Tatsukawa,R.,1987.Tissuedistributionofheavy metalsinWeddellseals(Leptonychotesweddellii).MarinePollutionBulletin18, 164–169.

Yunker,G.B.,Hammill,M.O.,Gosselin,J.-F.,Dion,D.M.,Schreer,J.F.,2005.Foetal growthinnorth-westAtlanticgreyseals(Halichoerusgrypus).JournalofZoology 265,411–419.