HAL Id: inserm-01188194

https://www.hal.inserm.fr/inserm-01188194

Submitted on 28 Aug 2015

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of

sci-entific research documents, whether they are

pub-lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents

scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

population-based study.

Véronique Massari, Annabelle Lapostolle, Marie-Catherine Grupposo,

Rosemary Dray-Spira, Dominique Costagliola, Pierre Chauvin

To cite this version:

Véronique Massari, Annabelle Lapostolle, Marie-Catherine Grupposo, Rosemary Dray-Spira,

Do-minique Costagliola, et al.. Which adults in the Paris metropolitan area have never been tested for

HIV? A 2010 multilevel, cross-sectional, population-based study.. BMC Infectious Diseases, BioMed

Central, 2015, 15, pp.278. �10.1186/s12879-015-1006-9�. �inserm-01188194�

R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

Open Access

Which adults in the Paris metropolitan area

have never been tested for HIV? A 2010

multilevel, cross-sectional, population-based

study

Véronique Massari

1*, Annabelle Lapostolle

1, Marie-Catherine Grupposo

1, Rosemary Dray-Spira

1,

Dominique Costagliola

2and Pierre Chauvin

1Abstract

Background: Despite the widespread offer of free HIV testing in France, the proportion of people who have never been tested remains high. The objective of this study was to identify, in men and women separately, the various factors independently associated with no lifetime HIV testing.

Methods: We used multilevel logistic regression models on data from the SIRS cohort, which included 3006 French-speaking adults as a representative sample of the adult population in the Paris metropolitan area in 2010. The lifetime absence of any HIV testing was studied in relation to individual demographic and socioeconomic factors, psychosocial characteristics, sexual biographies, HIV prevention behaviors, attitudes towards people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), and certain neighborhood characteristics.

Results: In 2010, in the Paris area, men were less likely to have been tested for HIV at least once during their lifetime than women. In multivariate analysis, in both sexes, never having been tested was significantly associated with an age younger or older than the middle-age group (30–44 years), a low education level, a low self-perception of HIV risk, not knowing any PLWHA, a low lifetime number of couple relationships, and the absence of any history of STIs. In women, other associated factors were not having a child <20 years of age, not having additional health insurance, having had no or only one sexual partner in the previous 5 years, living in a cohabiting couple or having no relationship at the time of the survey, and a feeling of belonging to a community. Men with specific health insurance for low-income individuals were less likely to have never been tested, and those with a high stigma score towards PLWHA were more likely to be never-testers.

Our study also found neighborhood differences in the likelihood of men never having been tested, which was, at least partially, explained by the neighborhood proportion of immigrants. In contrast, in women, no contextual variable was significantly associated with never-testing for HIV after adjustment for individual characteristics.

Conclusions: Studies such as this one can help target people who have never been tested in the context of recommendations for universal HIV screening in primary care.

Keywords: HIV, Sexual behavior, Prevention, Gender, Multilevel, Cross-sectional studies, Social inequalities, Immigration status, Neighborhood

* Correspondence:veronique.massari@iplesp.upmc.fr

1Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ Paris 06, INSERM, Institut Pierre Louis

Institute d’Epidémiologie et de Santé Publique (IPLESP UMRS 1136), Department of Social Epidemiology, F-75012 Paris, France Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© 2015 Massari et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http:// creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Background

In high-income countries, publications on the barriers to and/or the facilitators of HIV testing remain scarce [1, 2], especially those focusing on the situation of their immigrant populations [3–7]. In France, because of the legal restrictions on collecting and processing data on ethnicity, religion and immigration status, there are few studies on the social and migrational determinants of HIV testing [8–10].

Despite universal access to HIV screening and treat-ment and one of the highest annual HIV testing rates in Europe (103 per 1,000 inhabitants) [11], the Paris region is characterized by a high proportion of HIV-positive tests (4.5 per 1,000 tests) and a large number of people who are unaware of their HIV infection (estimated at around 13,000 in a regional population of 11.9 million people) [12, 13]. In this context, new screening strategies have been considered, which consist not only in promot-ing regular testpromot-ing of high-risk individuals, but also in increasing the uptake of HIV screening by people who have never been tested. Indeed, in the past 5 years, the percentage of never-testers has decreased significantly but is still significant in this region. In 2010, a regional KABP survey found that 33.9 % of men and 21.5 % of women aged 18–54 years had never been tested during their lifetime (these proportions were 47.0 % and 33.6 % in 2004, respectively) [11]. The regional incidence of AIDS is estimated to be approximately 1,500 cases each year. In 2010, 60 % of them were unaware of their HIV status at the time of diagnosis, and 40 % had never been tested [14].

Our objectives were to collect certain socioeconomic status indicators, origin, sexual biographies, attitudes and behaviors regarding HIV testing and prevention, and neighborhood characteristics, in a representative sample of the adult, French-speaking population in the Paris metropolitan area and to determine those associated with no lifetime uptake of HIV testing.

Methods

The SIRS (a French acronym for health, inequalities and social ruptures) cohort is the first large, representa-tive, population-based cohort created to study the so-cial determinants of health and health-care utilization in the field of social epidemiology in France [15, 16]. In 2005, at inclusion, our study population was a multi-stage random sample of the adult French-speaking population living in the Paris metropolitan area (also called “Greater Paris”, consisting of the City of Paris and its three adjacent départements, which constitute the core area of the entire Paris region, with 6.6 million inhabitants). The primary sampling units were census blocks including about 2000 inhabitants each. Fifty of them were randomly selected from the 2595 eligible

census blocks according to their socioeconomic type. Subsequently, 60 households in each census block were chosen at random. Lastly, one adult in each household was randomly selected by the next-birthday method and interviewed at home.

In 2010, 47.2 % of the 3006 participants included in 2005 were reinterviewed (2.6 % were deceased, 1.8 % were too sick to answer our questions, 13.9 % had moved out of the 50 surveyed IRISs, 2.7 % were absent during the survey period, 18.4 % declined to participate, and 13.4 % were lost to follow-up). Their sex ratio and mean age were similar to those of the individuals who were not reinterviewed. The individuals lost to follow-up were younger and better off than the others, but neither their health status nor the socioeconomic type of their census block of residence was different. Those absent during the survey period had a lower socioeconomic sta-tus and were mostly immigrants. In each census block, the individuals who were not reinterviewed in 2010 were replaced by means of a random procedure similar to the one used in 2005, up to a final sample size of 60 adults interviewed per census block. The refusal rate among the newly contacted individuals was 29 % (the same as in 2005).

In this paper, data collected in 2010 were examined cross-sectionally. The independent variables were selected from the SIRS dataset for the relevance of their association with HIV testing [17] or, more generally, with preventive health-care activities [18]. The analyses were limited to the 2621 subjects under 70 years of age to avoid a possible memory bias in the older individuals and to compare our data with those from other French studies.

Ethics

This cohort study had received legal authorization from two national authorities for non-biomedical research [19]: the Comité consultatif sur le traitement de l’information en matière de recherche dans le domaine de la santé (CCTIRS) (authorization number 904251) and the Com-mission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés (CNIL) (authorization number 05-1024). The participants provide their verbal informed consent. Written consent was not necessary because this survey did not fall into the category of biomedical research (as defined by French law) and did not collect any personal identification data.

Measures Outcome

The outcome variable was no lifetime HIV testing. Demographics

A first set of independent variables examined in this study consisted of demographics, which included age and ‘immigration status’. The latter was defined and

categorized on the basis of both the individual’s and his/ her parents’ nationality (at the time of the survey or of their death), distinguishing between French, born to two French parents; French, born to at least one foreign par-ent; and foreigners. Because HIV screening for all preg-nant women had been widely offered since 1990 in France [20], having a child <20 years of age (or being pregnant at the time of the survey) was also considered.

Socioeconomic status

(SES)- Several characteristics related to the participants’ SES were taken into account: education level (none or primary school, secondary school, and postsecondary), employment status (actively employed vs. all others, including unemployed, retired, student and inactive), occupational category (coded as never having worked, blue-collar, tradespeople/salespeople/shopkeepers and intermediate occupation, lower white-collar, and upper white-collar), and monthly income per consumption unit (CU), as calculated according to the OECD scale [21]. Health care utilization status

This dimension was explored by examining two variables: health insurance status and having or not having a regular general practitioner.

HIV risk and stigma

The participants’ self-perception of HIV risk (ranked as low or high) and their knowing or not knowing people living with HIV/AIDS were taken into account. Five ques-tions regarding attitudes towards PLWHA (namely, would accept to 1) work with them, 2) have a meal at their home, 3) go on vacation with them, 4) have protected sex with them, and 5) let them look after their children or grand-children) were combined to calculate a stigma score, which ranged from 0 and 10 and increased with the level of negative attitude towards PLWHA. For each gender, this score was dichotomized into two categories (≤ or > 2, i.e., the mean score value for the entire population and also by gender).

Sexual biographies, attitudes and behaviors

The following variables were taken into account: self-reported sexual orientation (homosexual or bisexual, heterosexual, and not answered), the number of sexual partners of each sex, the number of sexual partnerships during the previous 5 years (one partnership, multiple partnerships or no partnerships), couple status at the time of the survey (no relationship, love affair, non-cohabiting couple or non-cohabiting couple), and the life-time number of couple relationships. The interviewees were also asked about their STI history (with a single question: “Have you ever had an STI?”, with no fur-ther details).

Social integration

Certain characteristics pertaining to the participants’ social ties and social support were taken into consideration as well: a feeling of being supported (or of not being sup-ported) by friends, relatives or neighbors (“social support” in the rest of this paper), living (or not) living alone, a sense of belonging to a community, and their religious affiliation and practice, if any (but not their religion per se, as this would not have been very acceptable in France). Neighborhood characteristics

At the neighborhood level, four socioeconomic character-istics of the census blocks of residence were considered. The mean monthly household income was calculated using the 2007 income tax database (provided by French tax authorities) and divided into quartiles. The propor-tions of immigrants, unemployed residents, and people with a low education level (no education or primary school) were available in the 2007 population census data provided by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies.

Statistical analyses

The differences in characteristics among the partici-pants who reported having been tested at least once for HIV and those who had not were investigated using χ2analysis or the Fisher exact test. Since sexual biographies, attitudes and behaviors vary according to gender [22, 23], all the analyses were stratified by sex. All of the univariate statistical analyses were weighted to take into account the sampling method and the poststratification adjustment for age and gender ac-cording to the 2007 general population census data [16]. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statis-tically significant.

To build the final model for each sex, we used the following modeling strategy. First, a null model was computed to estimate the area-level variations without any covariables. Second, we considered three groups of independent variables (1. demographics and SES; 2. the other individual variables, i.e., those concerning HIV risk and stigma toward PLWHA, sexual biographies, attitudes and behaviors, and social integration; and 3. the neighborhood variables) and performed a preselec-tion of the independent variables associated with our outcome in each of these groups. To do this, all the variables associated with our dependant variable with a p-value <0.20 in univariate analysis (Table 1) were selected manually (using a backward-selection procedure based on the Hosmer & Lemeshow approach [24] with a threshold p < 0.10) and checking for multicollinearity. Third, in Model 1, only the preselected demographic and socioeco-nomic variables were included and further selected using the same procedure but with a threshold p < 0.05. Fourth,

Table 1 Comparison of the characteristics of the HIV-tested and never-tested men (n = 1261) and women (n = 1360) in 2010 Overall (n = 2621) % Never-tested men (n = 537) % P-value (tested vs. never-tested) Never-tested women (n = 451) % P-value (tested vs. never-tested) Age 18–29 years 655 25.0 162/332 48.7 <.0001 133/323 41.3 <.0001 30–44 years 959 36.6 144/455 31.6 78/504 15.5 45–59 years 700 26.7 143/332 43.0 140/367 38.1 60–69 years 308 11.7 89/142 63.0 99/166 59.8 Immigration status French/French parents 1688 64.4 329/832 39.5 .0031 257/856 30.0 .001 French/foreign parent (s) 544 20.7 116/243 48.0 111/301 36.7 Foreigners 389 14.8 92/187 49.4 83/203 40.9 Children and pregnancy

No child under 20 years of age 1921 73.3 514/1201 42.8 .5360 333/720 46.3 <.0001 Child under 20 years of agea 701 26.7 23/60 38.8 118/640 18.4

Education level

None or primary school 145 5.6 52/75 68.8 <.0001 50/70 71.3 <.0001 Secondary school 941 35.9 234/468 50.1 173/473 36.6 Postsecondary 1535 58.4 251/718 35.0 228/817 27.9 Employment status Actively employed 1940 74.0 386/1012 38.1 <.0001 233/928 25.1 <.0001 All others 682 26.0 151/249 60.7 218/432 50.4 Socio-occupational category Never worked 249 9.5 63/83 76.4 <.0001 91/166 54.9 <.0001 Blue collar 190 7.2 88/162 54.0 13/27 48.8 Lower white-collar 948 36.2 147/362 40.7 202/586 34.5 Tradespeople, salespeople 479 18.1 93/238 39.2 74/237 22.2 Upper white-collar 758 28.9 146/416 35.1 70/342 20.5 Monthly income (€/CU)

First quartile (< 1100) 652 24.9 150/305 49.2 .0002 143/347 41.4 .0010 Second quartile (1100–1700) 663 25.3 142/304 46.8 113/359 31.5

Third quartile (1701–2500) 657 25.1 130/333 39.0 84/324 27.3 Fourth quartile (≥2501) 649 24.8 115/319 36.1 106/330 32.1 Health insurance status final

HI + additional insurance 2104 80.4 416/976 42.6 0.0380 345/1128 30.6 <0.0001 HI for the poor 178 6.8 27/86 31.4 36/92 39.1

HI with no additional insurance 335 12.8 94/198 47.5 66/137 48.2 Self-perception of HIV risk

High 708 27.0 73/349 20.9 <.0001 49/359 13.7 <.0001 Low 1913 73.0 465/912 51.0 402/1001 40.1

Knowing PLWHA

Yes 1650 63.0 396/807 49.1 <.0001 341/844 40.4 <.0001 No 971 37.0 141/455 31.1 110/516 21.3

Stigma towards PLWHA

Table 1 Comparison of the characteristics of the HIV-tested and never-tested men (n = 1261) and women (n = 1360) in 2010 (Continued)

Score > 2 882 33.6 217/421 51.6 184/460 39.9 Self-reported sexual orientation

Heterosexual 2515 95.9 522/1190 43.9 <.0001 435/1325 32.9 <.0001 Homo/bisexual 75 2.9 6/58 10.2 1/16 9.4

Not answered 31 1.2 10/13 76.9 14/19 74.9 Sexual partnerships during the previous 5 years

No partnerships 243 9.3 43/84 51.9 <.0001 99/159 61.9 <.0001 One partnership 1638 62.5 336/712 47.2 302/926 32.6

Multiple partnerships 740 28.2 158/465 33.9 50/274 18.1 Couple status at the time of the survey

Not in a relationship 569 21.7 143/279 51.5 <.0001 132/290 45.7 <.0001 Love affair 335 12.8 50/157 32.0 59/178 32.9

Non-cohabiting couple 156 5.9 21/82 25.5 15/73 20.3 Cohabiting couple 1562 59.6 323/743 43.4 245/818 29.9 Lifetime number of couple relationships

None 556 21.2 160/320 50.0 <.0001 116/237 49.0 <.0001 One 1317 50.3 285/565 50.5 268/753 35.6 ≥ 2 747 28.5 92/377 24.5 67/370 18.0 History of STI No 2260 86.2 513/1113 46.1 <.0001 409/1147 35.7 <.0001 Yes 361 13.8 24/148 16.4 42/213 19.5

Feeling of being supported

Yes 2597 99.1 533/1248 42.7 0.561 443/1349 32.8 0.0082

No 24.5 0.9 5/14 35.7 8/11 72.7

Living alone

Yes 414 15.8 75/223 33.6 0.002 73/190 38.4 0.1077 No 2207 84.2 463/1038 44.6 378/1169 32.3

Sense of belonging to a community

No 1806 68.9 347/872 39.8 .0024 273/934 29.3 <.0001 Yes 815 31.1 191/390 48.9 177/426 41.7

Practice of a religion

Practices a religion regularly 492 18.8 86/183 47.1 .1313 136/309 44.0 <.0001 Practices a religion but not on a regular basis 483 18.4 85/199 42.8 97/284 34.3

Affiliation but does not practice 699 26.7 154/353 43.6 101/346 29.1 No practicing or affiliation 949 36.2 212/526 40.4 117/422 27.8 Neighborhood variables

Mean annual household income (€/CU)

First quartile (< 17,000) 392 14.9 107/182 58.4 <.0001 81/209 38.8 .0026 Second quartile (17,000–21,999) 673 25.7 146/330 44.2 133/343 38.9 Third quartile (22,000–29,519) 776 29.6 157/375 41.8 112/401 28.0 Fourth quartile (≥ 29,520) 780 29.8 128/373 34.3 124/406 30.4 Proportion of immigrants First quartile 791 30.2 155/378 41.1 .0001 113/413 27.3 .0011

in Model 2, the other individual variables previously prese-lected were added to Model 1 and backward-seprese-lected with a threshold p < 0.05. Finally, all the contextual variables were added to Model 2 and selected in Model 3 in the same manner. Since no neighbourhood variable was found to be significantly associated in women, the final model was Model 2 (Table 3).

For each characteristic, the category with the lowest number of never-testers was used as the reference in the multivariate models. All the analyses used STATA soft-ware (STATA® v.12; STATA College Station, TX) with the xtmelogit procedure (specifying that collected data were clustered by census block). At each step, the level 2 variance was estimated to test for area-level variation, and the median odds ratio (MOR) was calculated. The MOR measures the median value of the adjusted OR between the most and least at-risk individual when com-paring all pairs of neighborhoods [25].

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The sample consisted of 1261 men (48.1 %) and 1360 women (51.9 %). The participants’ mean age (± SD) at the time of the interview was 41.6 (±15.4) years for the men and 42.3 (± 13.1) years for the women. With regard to SES (Table 1), 58.4 % had a higher education level, 74.0 % were actively employed, 21.7 % were not in a couple relationship at the time of the survey, and 15.8 % were living alone. A sense of belonging to a community was shared by 31.1 % of the study population, and 37.2 % practiced a religion.

In 2010, 42.6 % (n = 537) of the men and 33.2 % (n = 451) of the women reported that they had never been tested for HIV during their lifetime. The men were more likely to have never been tested for HIV than the women (42.6 % vs. 33.2 %, p < 0.001). Of the 1639 (62.0 %) participants tested at least once in their lifetime, 56.8 % had been tested at least once at their request, 56.8 % during a systematic or routine examination (including pregnancy, marriage, blood donations and preop exams), and 20 % at their physician’s request. Of the participants who had been tested, 39.7 % had been so during the pre-vious 24 months. The main reasons given for no testing were low risk perception (93 %), fear of HIV disease (3 %) and fear of HIV diagnosis disclosure (2 %).

The proportion of ever-testers varied greatly accord-ing to their neighborhood of residence, from 7.7 % (95 % CI: 0.0–19.6) to 85.7 % (95 % CI: 70.7–100.0) for the men, and from 19.3 % (95 % CI: 2.3–36.3) to 90.7 % (95 % CI: 80.1–100.0) for the women.

Factors associated with no lifetime HIV testing in men In the men (Table 1), the factors associated with never-testing for HIV in univariate analysis were a young (<29 years) or an old age (>60 years), being a foreigner or a French person born to at least one foreign parent, a lower education level, not being actively employed, being a blue-collar worker or never having worked, a lower income, having no additional health insurance, a low self-perception of HIV risk, not knowing any PLWHA, a high stigma score towards PLWHA, perceiving oneself as heterosexual or not answered, having had no or only one sexual partner during the previous 5 years, not

Table 1 Comparison of the characteristics of the HIV-tested and never-tested men (n = 1261) and women (n = 1360) in 2010 (Continued)

Second quartile 735 28.0 127/385 33.1 113/350 32.3 Third quartile 585 22.3 111/257 43.3 124/327 38.0 Fourth quartile 511 19.5 143/241 59.4 101/269 37.4 Proportion of unemployed persons

First quartile 707 27.0 130/334 39.0 .0003 112/373 29.9 .0008 Second quartile 835 31.9 156/399 39.2 134/436 30.7

Third quartile 622 23.7 143/315 45.5 98/306 32.0 Fourth quartile 457 17.4 107/213 50.3 107/244 44.0 Proportion of persons with a primary education

or less First quartile 868 33.1 153/417 36.7 .0001 115/451 25.4 .0001 Second quartile 831 31.7 162/406 39.9 141/425 33.2 Third quartile 515 19.7 112/243 46.3 110/272 40.3 Fourth quartile 406 15.5 110/195 56.2 85/211 40.3 a

being in a couple relationship or living in a couple relationship at the time of the survey, having had no or only one couple relationship in one’s lifetime, not having a history of STIs, living alone, and the sense of belong-ing to a community. All the contextual variables tested were associated with the outcome. On the other hand, having a regular general practitioner, having social sup-port and practicing a religion were not associated with no lifetime HIV testing in the men.

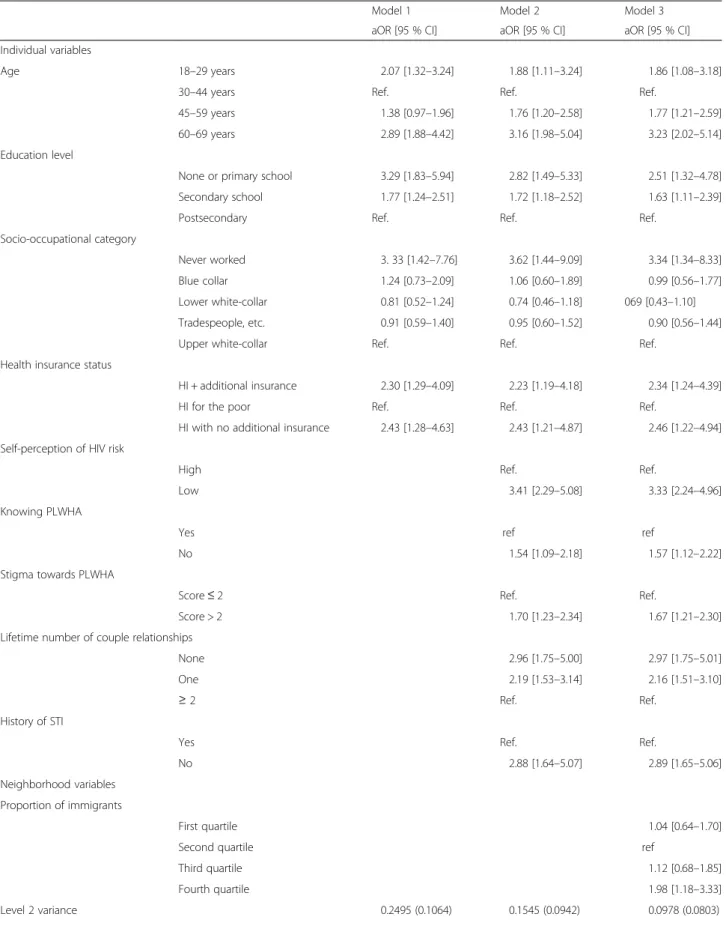

In multivariate multilevel analysis (Table 2), an area-level effect was found in the null model (area-level 2 variance of 0.2898 [0.1087], p = 0.008). Model 1 (with demographic and socioeconomic variables) showed that the factors associated with no lifetime HIV testing were all the age groups, except 30–44 years, a low or an intermediate education level, never having worked, and health insur-ance status (having health insurinsur-ance specifically for low-income individuals was associated with a lower likelihood of never having been tested than being insured through the usual system, with or without additional insurance). Introducing these characteristics reduced the level 2 variance by 14 %. In Model 2, the factors associated with our outcome included a low self-perception of HIV risk, a high stigma score towards PLWHA, not knowing any PLWHA, having had no or only one life-time couple relationship, and not having a history of STIs. Introducing these characteristics led to a 53 % reduction in the initial level 2 variance. When further introducing neighborhood characteristics, only the pro-portion of immigrants in the neighborhood of residence was significant. In Model 3, the area-level variance (0.0978 [0.0803]) was no more significantly different from zero when both the individual and area-level variables were taken into account, and the MOR gradually decreased from 1.67 in the empty model to 1.35 in the full model. Factors associated with no lifetime HIV testing in women In the women (Table 1), the factors positively associated with never-testing for HIV in univariate analysis were a younger (< 29 years) or an older age (> 60 years), being a foreigner or a French person born to at least one foreign parent, not having a child < 20 years of age, a low educa-tion level, not being actively employed, being a blue–collar worker or never having worked, a lower income, not hav-ing additional health insurance or havhav-ing insurance for low-income individuals, a low self-perception of HIV risk, not knowing any PLWHA, a high stigma score towards PLWHA, being self-reported as heterosexual or not an-swered, having had no or only one sexual partner during the previous 5 years, not being in a couple relationship at the time of the survey, never having been in a couple rela-tionship, not having a history of STIs, weak social support, a sense of belonging to a community, and practicing a religion on a regular basis. On the other hand, neither

having a regular practitioner nor living alone was associ-ated with never having been tested for HIV. All the con-textual variables were significantly associated with the outcome.

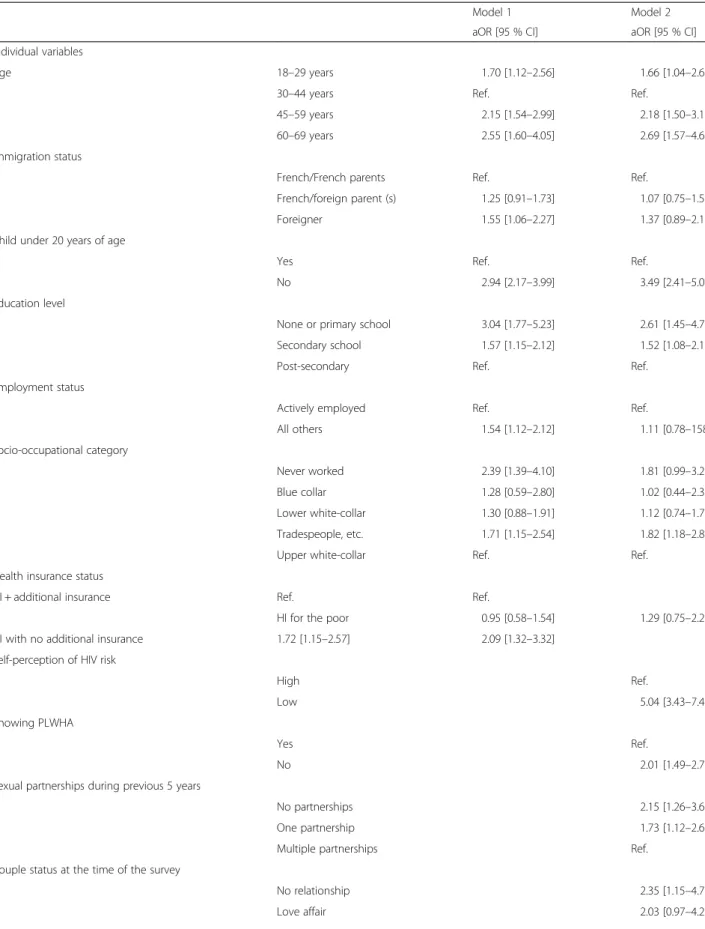

In multivariate multilevel analysis (Table 3), an area-level effect was found in the null model (area-area-level variance of 0.1864 [0.0698], p = 0.008). The following characteristics were selected in Model 1: the age groups other than 30–44 years, being a foreigner, not having a child < 20 years of age, a low or intermediate education level, not being actively employed, never having worked or being in an intermediate socio-occupational category, and not having additional health insurance. Introducing these characteristics reduced the level 2 variance by 38 %, and the area-level variance (0.1179 [0.0637]) was no more sig-nificantly different from zero. In Model 2, the attitudes and behavioral factors associated with never having been tested for HIV included a low self-perception of HIV risk, not knowing any PLWHA, a high stigma score towards PLWHA, having had no or only one sexual partner during the previous 5 years, not being in a couple relationship or being in a cohabiting couple relationship at the time of the survey, never having been in a couple relationship, not having a history of STIs, and a sense of belonging to a community. In the full model, the only neighborhood vari-able selected in the absence of any individual covarivari-ables (the neighborhood proportion of inhabitants with a low education level) was not significantly associated with the outcome. Overall, the successive adjustments had smaller impacts on level 2 variance and MOR in the woman than in the men.

Discussion

In addition to the socioeconomic factors usually ob-served to be associated with prevention attitudes and practices, we found that the absence of any lifetime HIV testing was associated with a low risk perception, health insurance status, not knowing any PLWHA, a high stigma score towards PLWHA, a low lifetime number of couple relationships, the absence of any history of STIs and, for men only, the neighborhood proportion of immigrants.

Our sample was limited to the Paris metropolitan area, which limits its external validity, particularly in nonurban contexts. However, since this region bears the largest part of the HIV burden in mainland France, our conclusions could be useful in helping manage the epidemic [26]. Unfortunately, because of the sampling design, we were unable to reach the most vulnerable populations, such as homeless people (among whom immigrants are overrepre-sented) [27]. Also, we interviewed only French-speaking individuals, thereby excluding still more foreigners but non-French-speaking individuals accounted for 5 % of the initial sample. If they had been included in the SIRS

Table 2 Factors associated with never-testing for HIV among men (n = 1261) as determined by multilevel multivariate logistic regression

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 aOR [95 % CI] aOR [95 % CI] aOR [95 % CI] Individual variables

Age 18–29 years 2.07 [1.32–3.24] 1.88 [1.11–3.24] 1.86 [1.08–3.18] 30–44 years Ref. Ref. Ref.

45–59 years 1.38 [0.97–1.96] 1.76 [1.20–2.58] 1.77 [1.21–2.59] 60–69 years 2.89 [1.88–4.42] 3.16 [1.98–5.04] 3.23 [2.02–5.14] Education level

None or primary school 3.29 [1.83–5.94] 2.82 [1.49–5.33] 2.51 [1.32–4.78] Secondary school 1.77 [1.24–2.51] 1.72 [1.18–2.52] 1.63 [1.11–2.39] Postsecondary Ref. Ref. Ref.

Socio-occupational category

Never worked 3. 33 [1.42–7.76] 3.62 [1.44–9.09] 3.34 [1.34–8.33] Blue collar 1.24 [0.73–2.09] 1.06 [0.60–1.89] 0.99 [0.56–1.77] Lower white-collar 0.81 [0.52–1.24] 0.74 [0.46–1.18] 069 [0.43–1.10] Tradespeople, etc. 0.91 [0.59–1.40] 0.95 [0.60–1.52] 0.90 [0.56–1.44] Upper white-collar Ref. Ref. Ref.

Health insurance status

HI + additional insurance 2.30 [1.29–4.09] 2.23 [1.19–4.18] 2.34 [1.24–4.39] HI for the poor Ref. Ref. Ref.

HI with no additional insurance 2.43 [1.28–4.63] 2.43 [1.21–4.87] 2.46 [1.22–4.94] Self-perception of HIV risk

High Ref. Ref.

Low 3.41 [2.29–5.08] 3.33 [2.24–4.96] Knowing PLWHA

Yes ref ref

No 1.54 [1.09–2.18] 1.57 [1.12–2.22] Stigma towards PLWHA

Score≤ 2 Ref. Ref.

Score > 2 1.70 [1.23–2.34] 1.67 [1.21–2.30] Lifetime number of couple relationships

None 2.96 [1.75–5.00] 2.97 [1.75–5.01] One 2.19 [1.53–3.14] 2.16 [1.51–3.10]

≥ 2 Ref. Ref.

History of STI

Yes Ref. Ref.

No 2.88 [1.64–5.07] 2.89 [1.65–5.06] Neighborhood variables

Proportion of immigrants

First quartile 1.04 [0.64–1.70]

Second quartile ref

Third quartile 1.12 [0.68–1.85] Fourth quartile 1.98 [1.18–3.33] Level 2 variance 0.2495 (0.1064) 0.1545 (0.0942) 0.0978 (0.0803)

cohort, the difference between French persons and for-eigners may have been accentuated by the inclusion of more individuals not reached by prevention messages.

The participants were interviewed retrospectively about any previous HIV testing. The last test had been per-formed on average about 5 years before the survey date. Thus, there was a possible recall bias concerning the circumstances of the last test. In addition, some respon-dents may have confused certain routine laboratory tests with the HIV screening test, which would have led to an overestimation of HIV testing, especially among recent immigrants and less educated and/or less health-literate individuals.

Many studies on the utilization of health-care services have shown that people with a low SES are less likely to avail themselves of preventive care, even in countries where national health services and/or universal health insurance should preclude any financial obstacles to such care [28]. For instance, we reported similar socio-economic gradients in women’s cancer screening in the same survey population [29, 30].

Taking into account certain indicators of sexual behav-iors and attitudes toward PLWHA enabled us to explore the contribution of these factors to some but not all of the observed socioeconomic and demographic differences. In particular, due to a lack of statistical power, we were un-able to find a significant association with (self-reported) sexual orientation, since the number of participants who indicated that they were bi- or homosexual was too small in both genders (58 men and 16 women). Moreover, these numbers were probably underestimated, particularly in certain immigrant populations where sexuality and espe-cially homosexuality are still taboo and/or punished by law in their country of origin [31].

The fact that younger people of both sexes were less likely to have been tested for HIV is particularly worri-some. Of course, HIV prevalence in young heterosexual people remains low, with the result that they are not the most at risk for HIV exposure (until now). However, a recent KABP study in the French capital region found that people in this age group had a poorer knowledge and a weaker perception of HIV risk compared not only to the other age groups in 2010, but also to the same age group interviewed previously, between 1992 and 2004 [26]. Indeed, in our study, 70.5 % of the men and 34.2 % of the women in this age group reported that they had had more than one sexual partner during the

previous 5 years (compared to 24.9 % and 14.5 %, respect-ively, of the rest of the population), while in a regional KABP study, only 39 % of the men and 27 % of the women in this age group indicated that they had used a condom at last intercourse (compared to 45 % and 36 % in 2004, respectively) [26]. We also observed, in a previous analysis, that of the 655 HIV-negative individuals aged 18 to 29 years who had answered the question about their intention regarding protection in 2010, 376 (57.4 %) reported that they consistently used condoms to protect themselves from HIV (men more often than women: 71.0 % vs. 43.3 %, respectively, p < 0.001) [32].

We also observed that older age was independently associated with never-testing for HIV in both genders. The recent ANRS-Vespa2 study found that older people were also at higher risk for late presentation of HIV in all the subpopulations that were specifically examined, e.g., heterosexual male and female immi-grants born in sub-Saharan Africa or North Africa and North Africans who practice a religion. Moreover, MSM over 50 who did not define themselves as gay were at higher risk for late HIV diagnosis [33]. Such a lower level of HIV testing in older individuals could certainly have major consequences on the epidemiology of HIV infection.

In a previous analysis of the same cohort in 2005 (with far fewer individual characteristics obtained by interview and analyzed), we found that gender, socio-economic status, immigration status and neighborhood of residence were barriers to HIV testing in the adult population in the Paris metropolitan area [17]. We also found that measures aimed at increasing HIV testing in sub-Saharan immigrants may have been effective, given that people from sub-Saharan Africa were more likely to have been tested in their lifetime (78.5 %) than those of French (56.2 %) or Maghreb (39.7 %) origin (p < 0.0001) [34]. In 2010, we found that women with a sense of belonging to a community and, to a lesser extent, for-eign women were less likely to have been HIV-tested than other women. Actually, these two characteristics are obviously correlated, given that a sense of belong-ing to a community is shared by 49 % of foreign women and 45 % of French women born to at least one foreign parent (compared to 22 % of French women born to French parents, p < 0.0001). In men, these figures were, respectively, 49 %, 45 % and 22 % (p < 0.0001).

Table 2 Factors associated with never-testing for HIV among men (n = 1261) as determined by multilevel multivariate logistic re-gression (Continued)

p-value 0.019 0.101 0.223

MOR 1.61 1.45 1.35

Table 3 Factors associated with never-testing for HIV among women (n = 1360) as determined by multilevel multivariate logistic regression

Model 1 Model 2 aOR [95 % CI] aOR [95 % CI] Individual variables

Age 18–29 years 1.70 [1.12–2.56] 1.66 [1.04–2.66] 30–44 years Ref. Ref.

45–59 years 2.15 [1.54–2.99] 2.18 [1.50–3.17] 60–69 years 2.55 [1.60–4.05] 2.69 [1.57–4.62] Immigration status

French/French parents Ref. Ref.

French/foreign parent (s) 1.25 [0.91–1.73] 1.07 [0.75–1.55] Foreigner 1.55 [1.06–2.27] 1.37 [0.89–2.10] Child under 20 years of age

Yes Ref. Ref.

No 2.94 [2.17–3.99] 3.49 [2.41–5.07] Education level

None or primary school 3.04 [1.77–5.23] 2.61 [1.45–4.71] Secondary school 1.57 [1.15–2.12] 1.52 [1.08–2.13] Post-secondary Ref. Ref.

Employment status

Actively employed Ref. Ref.

All others 1.54 [1.12–2.12] 1.11 [0.78–158] Socio-occupational category Never worked 2.39 [1.39–4.10] 1.81 [0.99–3.27] Blue collar 1.28 [0.59–2.80] 1.02 [0.44–2.36] Lower white-collar 1.30 [0.88–1.91] 1.12 [0.74–1.72] Tradespeople, etc. 1.71 [1.15–2.54] 1.82 [1.18–2.80] Upper white-collar Ref. Ref.

Health insurance status

HI + additional insurance Ref. Ref.

HI for the poor 0.95 [0.58–1.54] 1.29 [0.75–2.22] HI with no additional insurance 1.72 [1.15–2.57] 2.09 [1.32–3.32]

Self-perception of HIV risk

High Ref.

Low 5.04 [3.43–7.41]

Knowing PLWHA

Yes Ref.

No 2.01 [1.49–2.71]

Sexual partnerships during previous 5 years

No partnerships 2.15 [1.26–3.67] One partnership 1.73 [1.12–2.68] Multiple partnerships Ref.

Couple status at the time of the survey

No relationship 2.35 [1.15–4.78] Love affair 2.03 [0.97–4.27]

In our study, we found that individuals with a low life-time number of couple relationships were less likely to have been tested. Another French study among late-tested HIV-positive individuals found that both male and female heterosexuals in a steady relationship and with children felt that they were less at risk for HIV in-fection and that this put them at greater risk for never having been tested in the absence of symptoms [35]. Generally speaking, since they are not priority targets for testing promotion, individuals at low risk for HIV infec-tion are at high risk for not being tested for HIV and for late diagnosis [36]. In our study, a low self-perceived risk for HIV infection was associated with no HIV testing in both sexes. Some studies have reported similar observa-tions in immigrants in Portugal [6] and Spain [7], and in pregnant women in other European countries [2, 37, 38]. Deblonde et al., in a systematic review in Europe, found that the main barrier to HIV testing are a low risk perception, fear of HIV disease and of HIV diagnosis disclosure, and lack of access to health services. In our study. the two responses (fear of disease and fear of dis-closure) were given, respectively, by only 3 % and 2 % of the never-testers. A minor gradient was observed for fear of disclosure according to immigration status in both sexes (respectively, 0 %, 0.5 % and 8.4 % in the women and 1 %, 1.8 % and 2.7 % in the men).

The men with a high stigma score towards PLWHA and those who did not know any PLWHA among family, friends or coworkers were more likely to be never-testers. As suggested by Burkholder et al. [39], since they do not empathize or identify with PLWHA, people who stigmatize them cannot perceive themselves as possibly

being concerned by this matter or at risk for HIV infec-tion. In other words, people with stigmatizing attitudes may perceive a greater distance between themselves and those with the disease [31]. Stigma serves to emphasize and enhance the differences between the stigmatizers and those being stigmatized [40].

The association observed between no HIV testing and no history of STIs could be due to the fact that French health authorities recommend proposing an HIV test whenever an STI is suspected [41]. Practically, this recommendation seems to be followed by some health professionals but not a majority of them. Indeed, in a French study in newly diagnosed HIV-infected people carried out in 2010, only half of the individuals with STIs during the 3 years prior to HIV diagnosis had actu-ally received an HIV testing proposal from a health-care provider [42] .

Lastly, our study found a contextual effect on no life-time HIV testing in men. Indeed, the decrease in the level 2 variance and its p-values showed that introducing the proportion of immigrants living in the neighborhood of residence explained part of the observed differences between neighborhoods. In contrast, in women, the sig-nificant differences in the observed crude prevalence rates of HIV testing between neighborhoods were mainly explained by a composition effect (i.e., by individual characteristics).

The men living in neighborhoods with a high propor-tion of immigrants (more than 28 %) were two times less likely to have been HIV-tested those living in neighbor-hoods with a proportion of immigrants between 17 and 23 %. This could be explained by a number of norms

Table 3 Factors associated with never-testing for HIV among women (n = 1360) as determined by multilevel multivariate logistic re-gression (Continued)

Non-cohabiting couple Ref.

Cohabiting couple 3.25 [1.57–6.72] Lifetime number of couple relationships

None 2.63 [1.55–4.46] One 1.39 [0.99–1.93] ≥ 2 Ref. History of STI No 1.62 [1.05–2.50] Yes Ref.

Sense of belonging to a community

Yes 1.33 [0.99–1.79]

No Ref.

Level 2 variance 0.1179 (0.0637) 0.1655 (0.0804)

P-value 0.064 0.039

MOR 1.39 1.47

shared by immigrant men in these neighborhoods, such as the fear of stigmatization or discrimination related to being tested for HIV (regardless of the result). Indeed, we observed that foreigners and French persons born to at least one foreign parent were more likely to have a positive stigma score than French persons born to French parents (61.0 %, 48.2 % and 34.3 %, respectively, in men, p < 0.0001; 60.2 %, 48.4 % and 31.3 %, respect-ively, in women, p < 0.0001). Similarly, foreigners and French persons born to at least one foreign parent were less likely to report that they knew a PLWHA than French persons born to French parents, (19.2 %, 28.8 % and 39.0 %, respectively, in men, p < 0.0001; 28.7 %, 27.6 % and 42.2 %, respectively, in women, p < 0.0001). Lastly, not knowing any PLWHA was significantly asso-ciated with a positive stigma score: 47.6 % of the men who did not know any PLWHA had a positive stigma score versus 28.1 % of those who did (p <0.001). In the women, these figures were, respectively, 47.9 % and 23.6 % (p <0.001).

No lifetime HIV testing could also be a consequence of differentiated practices by health professionals accord-ing to their patients’ social or demographic characteris-tics. For instance, in 2003, a French study found that the factors associated with the lack of proposing HIV/AIDS and hepatitis B and C screening in general practice to underprivileged immigrants were gender (women were screened less for HBV and HCV infection) and being from a non-sub-Saharan African country (especially from North Africa) for all three viruses [43].

Conclusions

At a time when, in France, many people remain unaware of their HIV status, when the proportion of people screened late is not decreasing and when many practi-tioners are not adhering to the recommendations for universal screening in primary care [44], it seems more important than ever that HIV screening services target not only the high-risk populations, but also those with a lower self-perceived risk of infection and/or at high risk for stigma, such as younger and older people, those in a steady relationship, and men living in immigrant neigh-borhoods. In 2016, a new French policy will merge (pre-viously split) HIV, viral hepatitis and/or STI screening centers into comprehensive sexual health centers, which will provide all these screening tests, as well as informa-tion, contracepinforma-tion, STI care and linkage to specialist care. This will possibly increase access to HIV screening for those who stay away from HIV testing services. Also, community-based and/or outreach, combined, rapid screening test services should not be limited in France to MSM communities but rather extended to other com-munities, in particular, immigrant communities other than just that from sub-Saharan Africa.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no financial competing interests exist. Authors’ contributions

All the authors contributed to the study. VM, AL, PC and DC had the idea for the study. All the authors substantially contributed to the conception and design of the study. VM, PC, AL and RDS created the questionnaire used in the study. AL and MCG were responsible for the data management. VM and MCG performed the statistical analyses and presented the results. All the authors participated in the interpretation of the results. VM, PC and RDS drafted the article. All the authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.” Funding

The SIRS survey was supported by the Institute for Public Health Research (IReSP) (grant number 2008-87; URL:http://www.iresp.net), the French National Agency for Research on AIDS and Viral Hepatitis (ANRS) (grant number 2009-072), and Sidaction.

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author details

1Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ Paris 06, INSERM, Institut Pierre Louis

Institute d’Epidémiologie et de Santé Publique (IPLESP UMRS 1136), Department of Social Epidemiology, F-75012 Paris, France.2Sorbonne

Universités, UPMC Univ Paris 06, INSERM, Institut Pierre Louis Institute d’Epidémiologie et de Santé Publique (IPLESP UMRS 1136), Department of HIV Clinical Research, F-75013 Paris, France.

Received: 2 April 2015 Accepted: 1 July 2015 References

1. De Wit JB, Adam PC. To or not to test: psychosocial barriers to HIV testing in high-income countries. HIV Med. 2008;9 Suppl 2:20–2. doi:10.1111/ j.1468-1293.2008. 00586.x.

2. Deblonde J, de Koker P, Hamers FF, Fontaine J, Luchters S, Temmerman M. Barriers to HIV testing in Europe: a systematic review. Eur J Publ Health. 2010;20(4):422–32. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckp231.

3. Stolte IG, Gras M, Van Benthem BH, Coutinho RA, van den Hoek JA. HIV testing behaviour among heterosexual migrants in Amsterdam. AIDS Care. 2003;15:563–74.

4. Fakoya I, Reynolds R, Caswell G, Shiripinda I. Barriers to HIV testing for migrant black Africans in Western Europe. HIV Med. 2008;9 Suppl 2:23–5. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00587.x.

5. Alvarez-del Arco D, Monge S, Azcoaga A, Rio I, Hernando V, Gonzalez C, et al. HIV testing and counselling for migrant populations living in high-income countries: a systematic review. Eur J Publ Health. 2011;23(6):1–7.

6. Dias S, Gama A, Severo M, Barros H. Factors associated with HIV testing among immigrants in Portugal. Int J Public Health. 2011;56:559–66. 7. Hoyos J, Fernandez-Balbuena S, de la Fuente L, Sordo L, Ruiz M, Barrio G,

et al. Never tested for HIV in Latin-American migrants and Spaniards: prevalence and perceived barriers. J Int AIDS Society. 2013;16:18560. http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.16.1.18560.

8. Le Vu S, Lydié N. Practices of HIV testing among people from sub-Saharan Africa in the Ile de France, 2005. Bull Epidémiol Hebd. 2008;7–8:52–5 (in French). 9. Lassetter JH, Callister LC. The impact of migration on the health of

voluntary migrants in western societies. J Transcul Nurs. 2009;20:93–104. 10. Lapostolle A, Massari V, Chauvin P. Time since the last HIV test and

migration origin in the Paris metropolitan area. France Aids Care. 2011;23(9):1117–27.

11. Halfen S, Embersin-Kyprianou C, Grémy I, Fauvelot S. Suivi de l’infection à VIH/sida en Ile de France. Bul Santé ORS Ile-de-France. 2011;15:1–8. 12. Cazein F, Barin F, Le Strat Y, Pilonnel J, Le Vu S, Lot F, et al. Prevalence and

characterisitics of individual with undiagnosed HIV infection in France: evidence from a survey of hepatitis B and C seroprevalence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(4):e114–7.

13. Supervie V, Ndawing JDA, lodi S, Costagliola C. The undiagnosed HIV epidemic in France and its implications for HIV screening strategies. Aids. 2014;28(12):1797–804. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000270.

14. Lot F, Pillonel J, Pinget R, Cazein F, Bernillon P, Leclerc M, et al. Les pathologies inaugurales de sida, France, 2003-2010. Bulletin Epidémiologique Hebdomadaire. 2011;43-44:454–7 (in French).

15. Chauvin P, Parizot I. Les inégalités sociales et territoriales de santé dans l’agglomération parisienne. Une analyse de la cohorte Sirs. In: In: Les cahiers de l’ONZUS. Saint-Denis La Plaine: Délégation interministérielle à la ville; 2009. p. 105.

16. Vallée J, Chauvin P. Investigating the effects of medical density on health-seeking behaviours using a multiscale approach to residential and activity spaces. Results from a prospective cohort study in the Paris metropolitan area, France. Int J Health Geogr. 2012;11:54. doi:10.1186/1476-072X-11-54. 17. Massari V, Lapostolle A, Cadot E, Parizot I, Chauvin P. Gender, socio

economic status, migration origin and neighbourhood of residence are barriers to HIV testing in the Paris metropolitan area: results from the SIRS cohort study of 2005. Aids Care. 2011;23(12):1609–18. doi:10.1080/ 09540121.2011.579940. Epub 2011 Jun 28.

18. Vallée J, Cadot E, Grillo F, Parizot I, Chauvin P. The combined effects of activity space and neighbourhood of residence on participation in preventive health-care activities: The case of cervical screening in the Paris metropolitan area (France). Health Place. 2010;16:838–52. Epub 2010 Apr 24. 19. Claudot F, Alla F, Fresson J, Calvez T, Coudane H, Bonaïti-Pellié C. Ethics and

observational studies in medical research: various rules in a common framework. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1104–8.

20. Massari V, Dorléans Y, Flahault A. Trends in HIV voluntary testing in general practices in France between 1987 and 2002. Eur J Epidemiol.

2005;20(6):543–7.

21. Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques. Definitions and methods- Consumptions units. http://www.insee.fr/en/methodes/ default.asp?page = definitions/ unite-consommation.htm.

22. Bajos N, Ducot B, Spencer B, Spira A. Sexual risk-taking, socio-sexual biographies and sexual interaction: Elements of the French national survey on sexual behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(1):25–40.

23. Bajos N, Bozon M. Enquête sur la sexualité en France - Pratiques, genre et santé. Paris: Editions La Découverte; 2008.

24. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley; 2000. 25. Larsen K, Merlo J. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on

individual health: integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(1):81–8. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi017. 26. Beltzer N, Saboni L, Sauvage C, Lydié N, Semaille C, Warszawski J, et al. An

18-year follow-up of HIV knowledge, risk perception, and pratices in young adults. Aids. 2013;27:1011–9.

27. Laporte A, Douay C, Detrez MA, Le Strat Y, Chauvin P. Psychiatric disorders among homeless people in Paris, France: a representative, population-based survey in 2009. New York Academy of Medicine: 9th International Conference on Urban Health; 2010. Abstract book: OS16.1.

28. O’Connell T, Rasanathan K, Chopra M. What does universal health coverage mean? Lancet. 2014;383:277–79.

29. Grillo P, Vallée J, Chauvin P. Inequalities in cervical cancer screening for women with or without a regular consulting in primary care for gynaecological health, in Paris. France Prev Med. 2012;54(3-4):259–65. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.01.013. Epub 2012 Jan 24.

30. Rondet C, Lapostolle A, Soler M, Grillo F, Parizot I, Chauvin P. Are immigrants and nationals born to immigrants at higher risk for delayed or no lifetime breast and cervical cancer screening? The results from a population-based survey in Paris metropolitan area in 2010. Plos One. 2014;9(1):e87046. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087046. eCollection 2014. 31. Riley G, Baah‐Odoom D. Do stigma, blame and stereotyping contribute to

unsafe sexual behaviour? A test of claims about the spread of HIV/AIDS arising from social representation theory and the AIDS risk reduction model. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(3):600–7.

32. Kesteman T, Lapostolle A, Massari V, Chauvin P. Impact of migration origin on individual protection strategies against sexual transmission of HIV in Paris metropolitan area, SIRS cohort study. Washington: AIDS Conference; 2012. Abstract No. A-452-0254-15154.

33. d’Ameida Wilson K, Dray-Spira R, Aubrière C, Hamelin C, Spire B, Lert F, et al. MSM over 50 years and not self-defined as gay more at risk of late presentation at HIV diagnosis: Results of the ANRS-Vespa2 study, France. Barcelona, Spain: XIth International AIDS Impact Conference; 2011. 29 September to 2 October 2013.

34. Lapostolle A, Massari V, Beltzer N, Halfen S, Chauvin P. Differences in recourse to HIV testing according to migration origin in the Paris metropolitan area in 2010. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(4):842–5. 35. Delpierre C, Cuzin L, Lauwers-Cances V, Marchou B, Lang T. High-risk groups

for late diagnosis of HIV infection: A need for rethinking test policy in the general population. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:838–46. doi:10.1089/ apc. 2006.20.838.

36. Delpierre C, Cuzin L, Lert F. Routine testing to reduce late HIV diagnosis in France. Brit Med J. 2007;334(5):1354–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.39225.458218. 94. 37. Burns FM, Imrie J, Nazroo JY, Johnson AM, Fenton KA. Why the (y) wait? Key

informant understandings of factors contributing to late presentation and poor utilization of HIV health and social care services by African migrants in Britain. AIDS Care. 2007;19:102–8.

38. Campbell T, Bernhardt S. Factors that contribute to women declining antenatal HIV testing. Health Care Women Int. 2003;24:544–51. 39. Burkholder GJ, Harlow LL, Washkwich JL. Social stigma, HIV/AIDS

knowledge, and sexual risk. J Appl Bio-Behavior Res. 1999;4:27e44. 40. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identuty. London:

Penguin; 1990.

41. Ministère de la Santé et des Sports. Plan national de lutte contre le VIH/ SIDA et les IST 2010-2014. Rapport du Ministère. Novembre 2010. 42. Champenois K, Cousien A, Cuzin L, Le Vu S, Deuffic-Burban S, Lanoy E, et al.

Missed opportunities for HIV testing in newly-HIV-diagnosed patients, a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:200. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-200. 43. Rigal L, Rouessé C, Collignon A, Domingo A, Deniaud F. Factors associated

with the lack of proposition of HIV-AIDS and hepatitis B and C screening to underprivileged immigrants. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2011;59:213–21. doi:10.1016/j.respe.2011.01.007. Epub 2011 Jul 2. (in French).

44. Conseil National du Sida CNS): Avis suivi de recommandations sur le bilan à mi-parcours du plan national de lutte contre le VIH/sida et les IST 2010–2014. http://wwwcns.sante.fr/spip.php?article495.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central and take full advantage of:

• Convenient online submission • Thorough peer review

• No space constraints or color figure charges • Immediate publication on acceptance

• Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar • Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at www.biomedcentral.com/submit