-j

China's Preference for the Regional Order in East Asia

MASSACHUSETS INSTITUTE

by

OF TECHNOLOGYLen Chow Koh

OCT29 2019

B.A., Cambridge University (2004) LIBRARIES M.Eng., Cambridge University (2004)

M.A., Cambridge University (2007) Submitted to the Department of Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Science in Political Science at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

September 2019© Len Chow Koh 2019. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now

known or hereafter created.

Signature redacted

Author

Department of Political Science

Signature redacted

August22,2019Certifiedby

M. Taylor Fravel Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by

Signature redacted

Fotini Christia Professor of Political Science Chair, Graduate Program Committee

China's Preference for the Regional Order in East Asia

ByLen Chow Koh

Submitted to the Department of Political Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on August 22, 2019 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in

Political Science

ABSTRACT

What explains China's preference for the regional order in East Asia? There has been a lot of existing literature looking at China's involvement in regional affairs and institutions. In contrast, there has been less research on what China's preference for the regional order is and what shapes it. Looking at China's preference for the regional order is important as it is a key factor influencing its regional behavior. As a rising power, China's behavior would have a significant impact on the peace and stability of East Asia.

I develop a typology of ideal types of regional order using the two parameters of distribution of

power and governing logic. I then develop a theory for China's preference for a particular type of regional order. China's preference for the distribution of power is affected by its relative capabilities vis-A-vis the other great powers in the region as well as its long-term threat perception. Its preference for the governing logic is influenced by its relative capabilities as well as the benefits/costs of a rule-based order.

I then test whether the theory is able to explain China's preference for the regional order. I looked

at China's statements and speeches, as well as its approaches towards ASEAN and on the South China Sea territorial disputes between 1990-2019 to assess what they reflect about China's preference for the regional order. I then compare this with what the theory predicts to be China's preference for the regional order during the same time period. I show that the theory broadly explains China's behavior towards regional cooperation and institutions during this time period.

Thesis Supervisor: M. Taylor Fravel

Table of Contents

List ofAbbreviations ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 7 List of Tables ... ... 9 L ist of F ig ures... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 11 Acknowledgements ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 13 In trod u ction ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 15Chapter 1: Typology ofRegional Orders ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 23

Chapter 2: Theory of China's preference for the regional order in East Asia... ... 47

Chapter 3: Chinese statements and speeches... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .... 77

Chapter 4: Chinese actions towards ASEAN... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... . .. ... ... ... 127

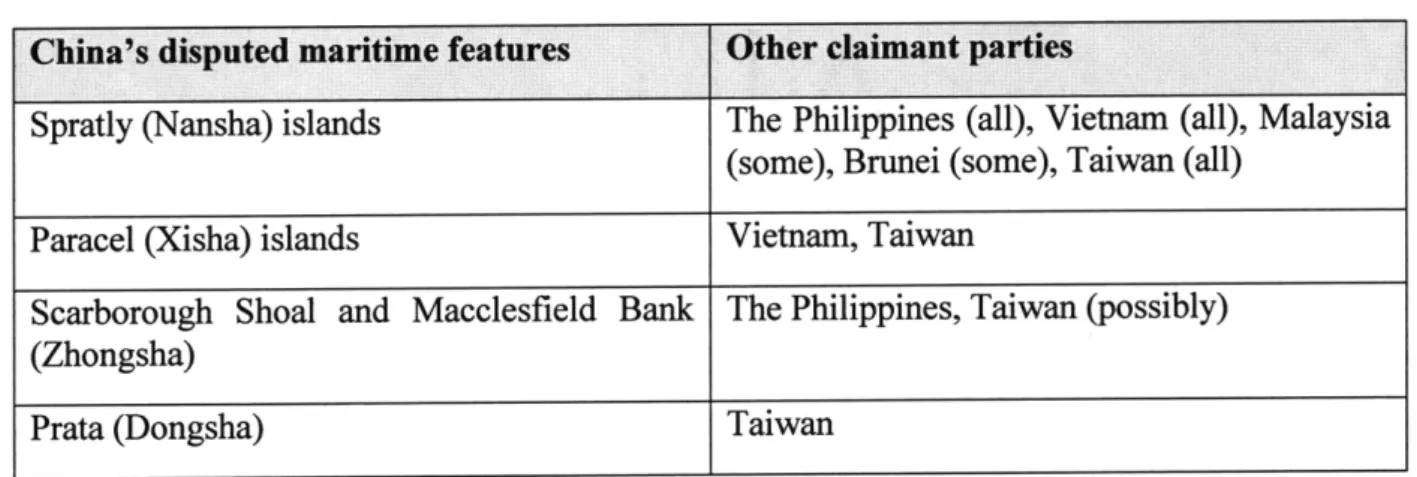

Chapter 5: Chinese actions on the South China Sea territorial dispute... ... ... ... .... ... ... 151

C on clusio n ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .... ... ... ... ... 169 B ibliog rap hy ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .... ... ... ... 1 77

List of Abbreviations

ACFTA ADB AIIB APEC ARF ASEAN ASEAN+3 BRI CCP CICA CMC COC DOC DV EAS EAVG EU FTA FTAAP GDP IMF IV JMSU NATO PRCASEAN-China Free Trade Area Asian Development Bank

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank Asia-Pacific Economic Community

ASEAN Regional Forum

Association of Southeast Asian Nations

ASEAN Plus Three

Belt and Road Initiative Chinese Communist Party

Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia Central Military Commission

Code of Conduct in the South China Sea

Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea Dependent variable

East Asia Summit East Asia Vision Group European Union

Free Trade Agreement

Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific Gross domestic product

International Monetary Fund Independent variable

Joint Maritime Seismic Understanding North Atlantic Treaty Organization

PSC Politburo Standing Committee

RCEP Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership

RSC Regional Security Complex

SCO Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

SCS South China Sea

TAC Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia

TPP Trans-Pacific Partnership

UN United Nations

UNCLOS United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea

USSR Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

WTO World Trade Organisation

WWI World War I

List of Tables

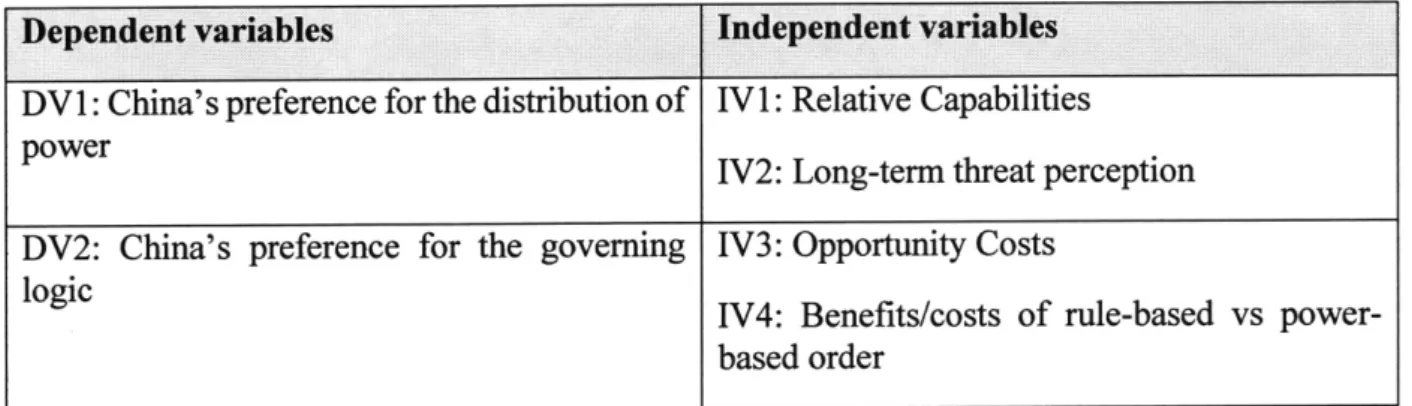

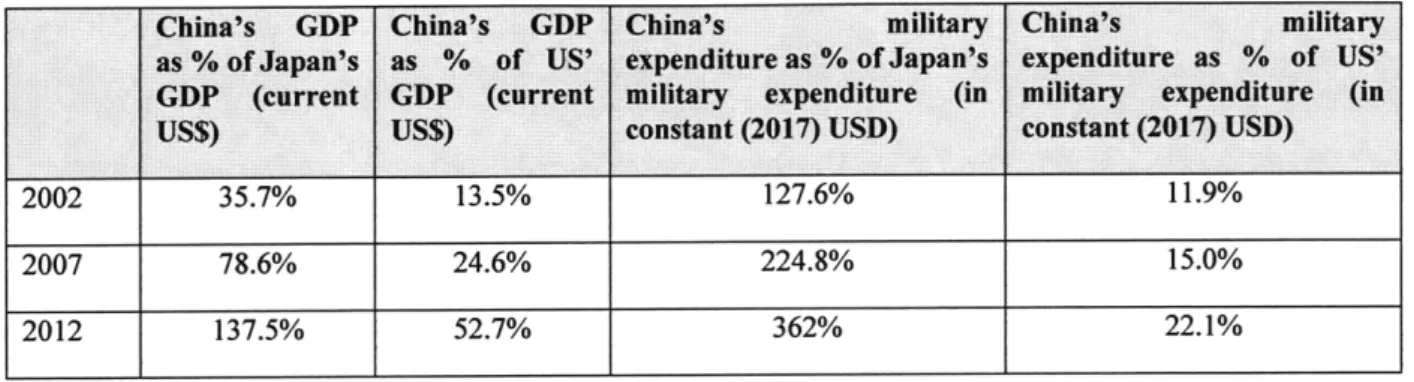

Table 1: Summary of dependent and independent variables ... 63 Table 2: Comparison of China's, Japan's and the US' GDP and military expenditure during Jiang Zem in's term in office ... ... 90 Table 3: Comparison of China's, Japan's and the US' GDP and military expenditure during Hu

Jintao's term in office ... 103

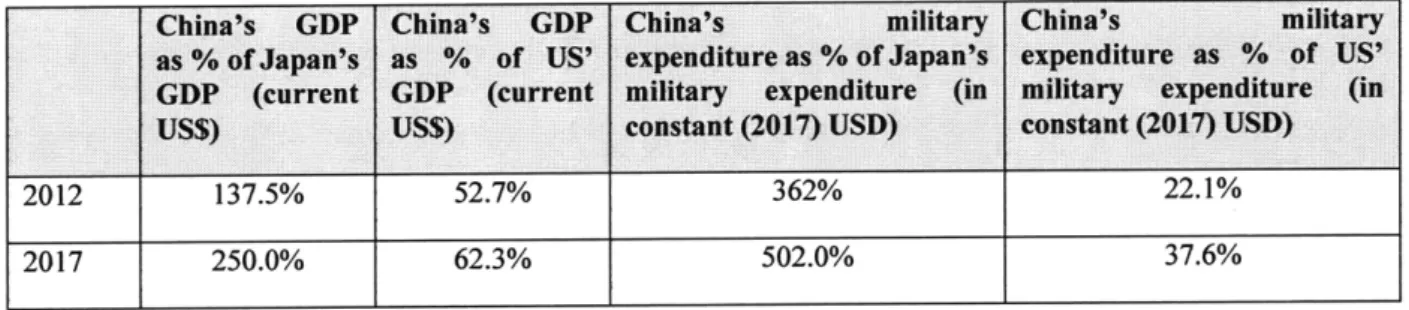

Table 4: Comparison of China's, Japan's and the US' GDP and military expenditure during Xi

Jinping's term in office ... 119

List of Figures

Figure 1: Degree of Distribution of Power ... 29

Figure 2: Governing Logic: Rules vs Power ... 34

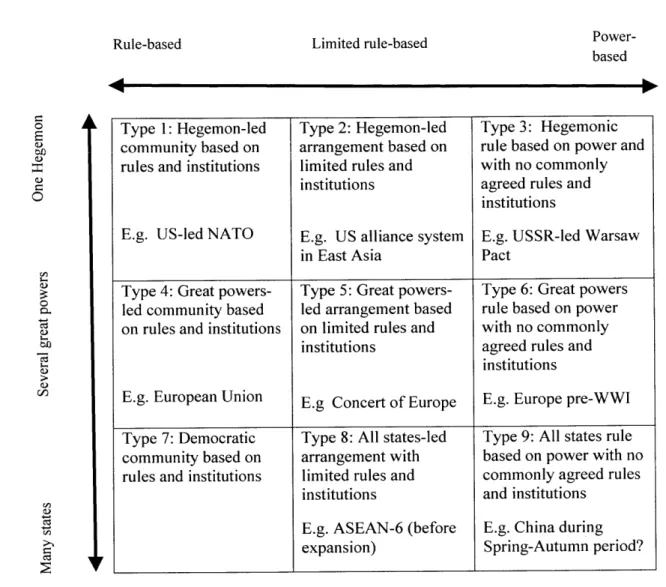

Figure 3: Typology of regional orders ... 35

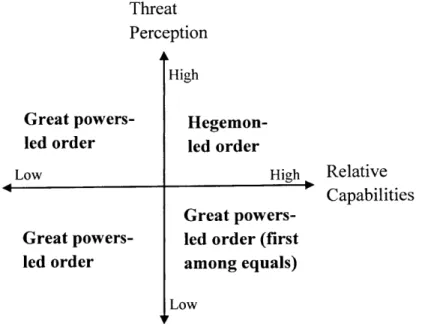

Figure 4: China's preference for distribution of power ... 56

Acknowledgements

Many people have made this thesis possible through their direct and indirect contributions. First and foremost is my supervisor Taylor Fravel. Taylor has been a great supervisor for the thesis. He has given me a lot of space to choose the thesis topic while providing a lot of generous comments when I consulted him on topic ideas and submitted drafts of my thesis. I would also like to thank Eric Heginbotham for agreeing to be my second reader. Despite his busy schedule, Eric agreed immediately to be my second reader and set aside time for discussion when I approached him about it. He also gave very substantive comments to my drafts which helped to make my thesis much better. I would also like to thank all the scholars and researchers who have done research in this area previously. I have cited some of their works in my bibliography. The pursuit of knowledge has always been a team effort across different generations of scholars and researchers. I am grateful for the work they have done previously which made my research possible and hope that I have made my little contribution to this area of study.

MIT provided a rich intellectual and conducive environment to pursue this project. I have received much inspiration from the classes I have taken. I would like to offer my thanks to the professors and students in these class who helped to make the classes intellectually stimulating. I would also like to thank MIT library for coming up with convenient tools to facilitate my research like Barton Plus and Borrow Direct.

Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends both in Singapore and in MIT whom have supported me in this one year. I wouldn't have been able to complete my studies and the thesis without the support of every single one of them.

Introduction

China's status as a rising great power in Asia and in the world is not in doubt these days. Most analysts assess that China would overtake the United States as the world's largest economy in the next decade. Its military spending is the second largest in the world after the United States and more than that of the other great powers in Asia combined (India, Russia and Japan).' China has always regarded its neighborhood as a key foreign policy (FP) priority. It has emphasized in its statements the need to ensure a peaceful and stable neighborhood for its national security and economic development. As early as 1993, then-CCP General Secretary Jiang Zemin said at the eighth Ambassadorial Conference that "any major problems happening in China's neighborhood would directly affect China's national security and economic interests. Hence, China should seriously deal with these problems ... to protect China's fundamental interests to the greatest extent."2 Given China's rising great power status and emphasis on its neighborhood, there are naturally questions about how it sees the regional order in its neighborhood. How does it see the current regional order? What is its preferred regional order? Is China a status quo or revisionist power in the region?

1. The Puzzle

SIPRI, "Trends in World Military Expenditure", SIPRI Fact Sheet, April 2019,

https://www.sipri.org./sites/default/files/20 19-04/fs 1904 milex 2018 0.pdf 2

Jiang Zemin, jiang zemin wenxuan di yijuan [Jiang Zemin's collected works vol 1] (Beijing; renmin chubanshe,

For my thesis, I will focus on the research question "What regional order does China want in East Asia?" To answer my research question, I will break it down into a series of sub-questions as below.

1. What has China said about its preferred regional order in East Asia?

2. What has China done to promote its preferred regional order in East Asia?

3. Is there a gap between China's statements and actions? If so, why?

4. Why is China pushing for this type of regional order?

I focus on East Asia because it is a complex region with several great powers such as the United

States, China and Japan, and multiple sets of regional rules/norms and institutions including the

U.S. alliance system and the ASEAN-led platforms. Any Chinese efforts to reshape the regional

order in East Asia can lead to tensions and potential conflict with the United States and its regional allies as well as with ASEAN. I will be looking at the time period from the 1990s till August 2019 which falls under the Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping leadership. I argue that this is an appropriate time period because the 1990s marked the start of China's sustained engagement of its neighborhood. In the previous decades, China was preoccupied with domestic developments (e.g. the Cultural Revolution, reform and opening up). Its foreign policy has been focused on maintaining a stable triangular relationship with the United States and USSR. As many academics noted, this changed at the turn of the 1990s with the Tiananmen incident, the end of the Cold War and collapse of the USSR. China began to see the importance of its Asian neighbors in getting

China out of its diplomatic isolation, counterbalancing the United States and in helping with China's economic development.3

Current research on China's preference for the regional order has been relatively limited. Many academics have focused on China's views and behavior towards the international order, whether it is a status-quo or revisionist power. 4 Other academics have looked at China's

engagement of Asia. They have applied various international relations theories ranging from realism to institutionalism to explain why China had or was reluctant to participate in regional cooperation.5 But not many academics have approached China's regional engagement from the perspective of its preference for the regional order.6

2. Summary of key findings

To preview the key findings of the thesis, I define a regional order as "the body of rules, norms, and institutions that govern relations among a cluster of states that are proximate to each other and are interconnected in spatial, cultural and ideational terms in a significant and

3 See Guoguang Wu and Helen Lansdowne, ed., China turns to multilateralism: Foreign policy and regional security (London: Routledge, 2008) and Medeiros Evan S., China's International Behavior: Activism, Opportunism, and Diversification (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 2009)

1 The examples for this are too numerous to cite. See, for instance, Michael J. Mazarr, Timothy R. Heath, Astrid Stuth

Cevallos, China and the International Order, (Santa Monica: RAND, 2018), Steve Chan, Weixing Hu, and Kai He, "Discerning States' Revisionist and Status-Quo Orientations: Comparing China and the US," European Journal of International Relations, 31 October 2018, Shiping Tang, China and the Future International and Order(s)," Ethics and International Affairs Vol. 32, No. 1 (2018), pp. 33-43

1 The examples for this are again too numerous to cite. See for instance Guoguang Wu and Helen Lansdowne, ed.,

China turns to multilateralism, (London: Routledge, 2008), Chien-peng Chung, China's multilateral cooperation in Asia and the Pacific: Institutionalizing Beijing's "Good Neighbouring" policy (London: Routledge, 2010), Marc Lanteigne, China and International Institutions: Alternate Paths to Global Power (London: Routledge, 2005), Asia's New Multilateralism, ed. Michael J. Green and Bates Gill (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009)

6 One exception is Sun Xuefeng & Huang Yuxing who used two parameters of the balance of power among major

countries in the region and the acceptability of regional rules in the region to map out four possible types of regional order. See Sun Xuefeng & Huang Yuxing, "China's Rise and the Evolution of East Asian Security Order", in China -Neighboring Asian Countries Relations: Review and Analysis, Volume 1, ed. Li Xiangyang

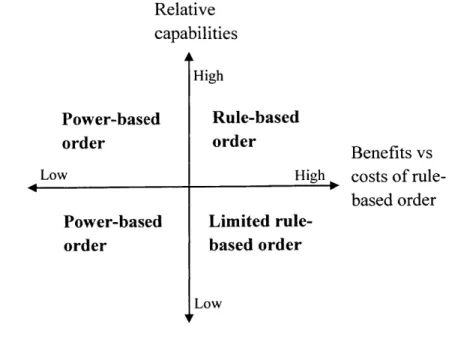

distinguishable manner." There are two parameters of regional orders in general, the distribution of power and the governing logic. The distribution of power is the number of powerful states in the region that is leading the order and can either be hegemon-led, great powers-led or led by all the states in the region. The governing logic is the principles determining state-to-state relations and how regional issues are resolved in the regional order and can be mainly divided into two types, rule-based and power-based. Using the two parameters, a typology of nine ideal types can be created ranging from power-based hegemonic rule to a democratic, rules-based community of states. China's preference for the regional order is driven by its long-term national interests, namely security, sovereignty, economic development and prestige. China's realist outlook towards international relations and its ideological/historical biases translate these national interests into its foreign policy approach including its preference for the regional order. There are several key factors (the independent variables) that affect China's preference for the distribution of power and governance logic of the order (dependent variables). China's relative capabilities vis-A-vis other great powers as well as its long-term threat perception affects its preference for the distribution of power. Its relative capabilities as well as the benefits versus costs of a rule-based order affect its

preference for the governance logic of the order.

China's preference for the regional order, as reflected in its statements and speeches as well as its approach towards ASEAN and on the SCS territorial disputes are largely similar and broadly consistent with what my theory predicts. Broadly, from 1990 till around early 201Os, Chinese statements and speeches, and approaches towards ASEAN and on the SCS issue showed China's preference for a great powers-led regional order, with a limited rule-based governing logic in the political and security domain and a rule-based governing logic in the economic arena. This is consistent with my theory which predicts that China would try to maintain a great powers-led order

to counterbalance the United States as it is relatively weak vis-d-vis the other great powers and has a high threat perception during this time period. China would also have seen the significant benefits to taking a rule-based approach towards economic cooperation with the other countries. But in the political and security domain, China would probably perceive the benefits of a rule-based approach as more limited due to its limited experience in rule-based institutions and its realist outlook and historical bias against a rule-based order. From early2010s till 2019, Chinese statements and speeches, and approaches towards ASEAN and on the SCS issue showed China's preference to be either the first among equal in a great powers-led regional order or to be the hegemon in a hegemon-led order while its preference for the governing logic in the different domains have not changed. Based on my theory, China would try to be the hegemon during this time period as its capabilities are stronger and has a high threat perception. At the same time, it holds the same preference for the governing logic for the same reasons above.

3. Importance and Contribution

My thesis would help to make some contributions to policy-making and research on

China and the regional order.

Contributions to policy-making

My thesis would help to inform the current debate about what kind of power China is and

wants to be. First, there is a belief among some elites and academics in the United States that China wants to be a regional hegemon, which presumes that China wants to build a certain kind of

regional order. Aaron Friedberg spoke of a U.S.-China "contest for supremacy" in Asia.7 Jennifer Lind spoke about "what regional hegemony would look like" in East Asia for China.8 My thesis will help to answer the question of whether China wants to be a regional hegemon in the first place. Second, looking at the regional order that China is building can give us a sense of how China intends to reshape the international order. As some academics have noted, even if China has global ambitions, it is unlikely to go head-on to challenge the US to reshape the international order. It is more likely to start reshaping the regional order in Asia where it has the greatest influence.9 There are likely to be significant lessons from China's interactions with regional countries and building of regional institutions. China would probably apply these learnings when it tries to reshape the

international order.

Contributions to academic research

My thesis would help to fill a gap in the current academic research on China. As noted in

the earlier section, the current research on China's preference for the regional order has been relatively limited and my thesis can serve as an exploratory research in this area. My thesis would also help to further our understanding of regional orders. There has been some work done on regional order by several academics. For example, Brry Buzan & Ole Waever looked at regional security order using the concept of regional security complexes. 0Peter Katzenstein looked at the

7 Friedberg, Aaron L., "A Contest for Supremacy: China, America, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia", W. W. Norton & Company, 2012

8 Lind, Jennifer, "Life in China's Asia: What Regional Hegemony Would Look Like", Foreign Affairs March/April 2018 Issue, https://w ww.fore ignaffairs.com/articies/chiina/2018-02-1 3/life-chinas-asia

9 See for instance, Schweller, Randall L. and Xiaoyu Pu, "After Unipolarity: China's Visions of International Order in an Era of U.S. Decline," International Security, Vol. 36 No. 1 (2011), pp. 41-72

1 Barry Buzan and Ole Waver, Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003)

regional orders that were created under the American Imperium." But these works focused on the current regional orders under the US hegemony. They generally do not theorize about the ideal types of regional orders and the conditions that lead states to choose one over the others. In my thesis, I would be developing a typology of regional orders as well as explanations on why China would pursue one regional order over the other. This would help to further our understanding of

regional orders in general.

4. Overview of the Chapters

This thesis will proceed in the following way. In chapter 1, I will give a proper definition of regional order and come up with a typology of the ideal types of regional order. In chapter 2, I will come up with a theory on why China would prefer one type of regional order over others. In chapter 3, 1 will examine key official Chinese statements and speeches relating to China's views and policies towards its neighborhood to understand how China perceives the different regions as well as its preferences on the regional order. I will compare to see if this is consistent with what my theory predicts. In chapter 4 and 5, I will be looking at China's approach towards ASEAN and on the SCS territorial disputes, again to see what it reflects on China's preference for the regional order and whether it is consistent with what my theory predict. Finally, in the conclusion, I will end with some observations on my findings and the follow-up research that can be done.

" Peter J. Katzenstein, A World of Regions: Asia and Europe in the American Imperium (New York: Cornell University Press, 2005)

Chapter 1: Typology of Regional Orders

1. Introduction

What are regional orders? Are there different types of regional orders? If so, what differentiates one type of regional order from another? Is there a typology of regional orders? Without answering these questions, it would be difficult to properly describe and characterize the type of regional order that China prefers and how that preference changes over time. Developing a typology of regional orders would also have broader applications beyond analyzing China's preference for the regional order in East Asia. It could be used to map out preferences of other potential and aspiring regional powers like India and Iran for the orders in their respective regions.

This chapter would proceed as follows. First, I will look at various definitions of regional order, identify the essential elements and come up with my own working definition for the purpose of this thesis. Second, based on the definition, I will come up with two key parameters, namely the distribution of power and the governing logic, that helps us to differentiate between the different types of orders. The distribution of power is about the number of leading powers in the regional order while the governing logic is about whether the leading powers rely on power or rules to resolve issues within the order. Third, I will use the two key parameters to create a typology of nine ideal types of regional orders. These range from power-based hegemonic rule to a democratic, rules-based community of states. I will cite historical and contemporary examples that approximate these ideal types to illustrate how they can be applied in real life. Fourth, I will address some issues with applying the ideal types of regional order, specifically whether there is an inherent contradiction in a hegemon-led or great powers-led rule-based regional order (my answer is no),

whether there is a difference between a power-based order and balance of power (my answer is yes), whether regional orders can exist only in one domain (political, economic or military) (my answer is not likely) and whether states, particularly powerful ones, can influence the distribution of power (my answer is yes).

2. Definition of Regional Order

There is no one common definition of regional order even though the concept of regional order has frequently been used in academic writings. Many of the definitions are incomplete or include normative elements which I argue are not essential to our understanding of regional order. Kissinger broadly defined regional order as "the concept held by a region about the nature of just arrangements and the distribution of power" that can be applied to "a defined geographic area."12 While his definition includes the key element of a distribution of power, it assumes that the order must be based on "a set of commonly accepted rules that define the limits of permissible action."13 As I will argue later, regional orders can also be governed by power where the hegemon or great powers within the order coerce other states to do their bidding. Sun Xuefeng & Huang Yuxing defines regional order as "the pattern of international behavior within the vested geographical scope and this pattern promotes the achievement of basic objectives. These include maintaining survival and sovereignty in the region, reducing and preventing violent conflict in the region, and implementing effective enforcement of regional rules, regional system arrangements, and organizational functioning."14 While I agree that regional order should include a pattern of

12 Kissinger, Henry, "World Order", (Penguin, 2014), p.9. 13 Ibid

behavior among the states, Sun & Huang's stated objectives of the order are not necessary, perhaps with the sole exception of the hegemon or great powers wanting to perpetuate the order. A regional order can be a violent one, with the hegemon or great powers allowing other states to use military actions to challenge each other's sovereignty or settle any disputes. Using Alaggapa's definition of order 5, Chung-In Moon & Seung-Won Suh defined regional order as "a formal or informal

arrangement that sustains rule-governed interactions among states in their pursuit of individual and collective goals in a specific region."' 6 I agree with Moon & Suh that there must be a formal

or informal arrangement within the regional order but I disagree that it must be "rule-governed." As I will note later, the interactions between states in a regional order can be power-driven, meaning that the more powerful state gets its way. All three definitions also do not properly define the scope a region or assume that it is purely geographical. As we will see later, the concept of a region is quite complex. It may not just be about geography but could include cultural and ideational elements.

I have come up with my own definition of regional order using other researchers'

definitions of the two concepts of "order" and "region". For my thesis, I define regional order as "the body of rules, norms, and institutions that govern relations among a cluster of states that are proximate to each other and are interconnected in spatial, cultural and ideational terms in a significant and distinguishable manner." I take RAND's definition of order which is "the body of rules, norms, and institutions that govern relations among the key players." 7 I find this definition

1 M. Alagappa, "The Study of International Order: An Analytical Framework," in Asian Security Order, ed. M. Alagappa, p.39-41

1 Chung-In Moon, Seung-Won Suh, "Identity Politics, Nationalism, and the Future of Northeast Asia Order," in The

United States and Northeast Asia: Debates, Issues, and New Order, ed. G. John Ikenberry, Chung-in Moon (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007), p. 194

17 Mazarr, Michael J., Miranda Priebe, Andrew Radin, and Astrid Stuth Cevallos, Understanding the Current

International Order. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016.

to be suitable as it breaks down the concept of order to its essential elements. As with the RAND report, I differentiate order from its "manifestation", i.e. the actual way in which order is organized and enforced. RAND noted that orders "can be built out of combinations of alliances, organizations (formal and informal, official and private), rules and requirements (established by treaty or other means), norms (sometimes emergent and sometimes calculated)." RAND called these

manifestations of order as "ordering mechanism."1Iconsiderstatesastheonlykeyplayersinthe

definition and do not consider non-state actors like multilateral institutions or non-governmental organizations as players. Similar to John Ikenberry, my definition of the concept of order "does not necessarily require normative agreement among its members" and that the order "could be based simply on exchange relations, coercion or the operation of the balance of power." 9 As for region, I take Thazha Varkey Paul's definition of "a cluster of states that are proximate to each other and are interconnected in spatial, cultural and ideational terms in a significant and distinguishable manner." This definition of region gives due justice to the complexity of the concept as it combines three different perspectives of looking at region including geographical proximity, cultural uniformity and ideational factors.2 0

18 Mazarr, Michael J., Miranda Priebe, Andrew Radin, and Astrid Stuth Cevallos, Understanding the Current International Order. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016.

littps:// www.iand.org/pubs/reseaich reports/R R1598.html, p. 7-8

' Ikenberry G. John, "After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order after Major Wars",

(New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 2001), p. 23

20 Paul T.V., "Regional transformation in international relations" in International Relations Theory and Regional Transformation, ed. Paul T.V. (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2012), p.5

3. Key parameters of a regional order

Using my working definition of regional order and taking reference from Ikenberry's types of international order, I argue that there are two key parameters for regional orders in general, namely the distribution of power and the governing logic.21

Distribution ofPower

The distribution of power affects how states interact with each other as well as the type of order that could emerge in a region. For instance, if there is just one powerful state and many weak ones in a region, the powerful state would be able to more easily use its power to coerce the weaker states hence creating or maintaining a hegemon-led regional order. But if there are several powerful states, each of these powerful states would find it harder to coerce the weaker states and to create or maintain a hegemonic order given the potential for these weaker states to engage in balancing behavior. To know the distribution of power in a regional order, it is necessary to properly define the concept of power. For my thesis, I adopt Michael Barnett & Raymond Duvall's definition which is that power is "the production, in and through social relations, of effects that shape the capacities of actors to determine their circumstances and fate."22 Barnett & Duvall's definition is a broader conceptualization of power as it include "a consideration of how social structures and processes generate differential social capacities for actors to define and pursue their interests and ideals."23 Hence, states can be powerful not just because they have much more

21 Ikenberry G. John, "Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order",

(New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 2011), p. 47

22 Barnett, Michael, and Raymond Duvall, "Power in International Politics." International Organization 59, no. 1

(2005), p. 42 23Ibid

material capabilities but also because of their influence in multilateral institutions or as norms setters (e.g. soft power). It differs from the more commonly accepted definition of power which is purely based on the material capabilities of the states." I adopt this broader definition because my study of regional order is inspired in the first place by the competition between leading powers to shape the structures and processes within a regional order. Leading powers compete because they realize that beyond their own material capabilities, a favorable regional order allows them to better pursue their national interests or broader values.

There are a few possible types of distribution of power (see Figure 1 below). On one extreme, there is only one powerful state in the region and no potential rivals which makes the state a hegemon. On the other extreme, all the states in the region have similar level of power and they are not able to dominate the regional order. In the middle, we might have several great powers with significant capabilities. These great powers counter-balance each other. There are two main sub-variations in this middle type of distribution of power. In one, the great powers have similar level of capabilities and none of them have the potential to dominate the regional order. In another sub-variation, one great power might be more powerful than other great powers and can potentially dominate the order. I call this more powerful great power the first among equals. But if the other great powers band together, they would still be able to resist this more powerful great power, hence this is still a great-powers-led order. This marks the distinction between a hegemon-dominated order and one with one great power more powerful than other great powers. In the former, the hegemon can dominate the order, i.e. it can get its way over the opposition of other great powers in the regional order. In the latter, it is not able to do so and would still have to take into account

24Barnett and Duvall defined it as "how one state uses its material resources to compel another state to do something

the views of other great powers. Separately, I would like to note that while IR theories pay special attention to bipolarity in the international system, this is not significant for my ideal types. A two great powers distribution of power in a region would fall under the middle category of "several major states."

Figure 1: Degree of Distribution of Power

Concentrated: Uneven: Several Dispersed: All

One hegemon great powers states of similar

capabilities

Governing logic

I define governing logic as the principles determining state-to-state relations and how

regional issues are resolved in the regional order. Similar to Ikenberry and RAND, I differentiate between two types of governing logic, rules and power. 2 5The regional order is rule-based if there

is a set of rules and institutions negotiated among all the states in the region which regulates the relationships among the states and how they should resolve regional issues. These rules and institutions offers some degree of procedural fairness among all states, giving even small states a role and voice within the order. A rule-based regional order is conceptually similar to one of the three types of international order that Ikenberry developed, namely the constitutional order. He noted that in a constitutional order, "the leading state agrees to extend decision-making access and rights to secondary states in exchange for their acquiescence in the order's rules and institutions."26

25 See Mazarr, Priebe, Radin, and Cevallos, Understanding the Current International Order and Ikenberry, After

Victory

It is important to emphasize that these rules and institutions must be negotiated, meaning that all the states willingly participate and comply because their interests are taken into account. The hegemon or great powers also choose to comply with these rules and institutions even if they have the power and short-term interests to break them. There is a distinction between "rule of law" and "rule by law" here, with a rule-based order being based on "rule of law". This means that a regional

order cannot be considered rule-based ifthe hegemon or great powers unilaterally impose rules

and institutions via coercion and do not follow them themselves. This is essentially "rule by law". Borrowing Bull's term, an ideal rule-based regional order can be seen as a society of states in a regional context, where order comes from "a sense of common interests in the elementary goals of social life; rules prescribing behavior that sustains these goals; and institutions that help to make these rules effective." 2 7 Clearly, a completely rule-based regional order is an ideal type and rarely happens in real life. Influence matters even in cases which approximate this ideal type (e.g. the US-led liberal order which I will elaborate later). A great power can hardly be expected not to use its power to shape the "rules of the game" in its favor. This happens especially if the great power is a hegemon in the order. But I still consider this order mostly "rule-based" if other states have a voice in the shaping of the rules and willingly participate and comply with these rules as it serve their own interests, and if the hegemon or great powers comply with the rules once the rules are decided.

The regional order is power-based if there are no set rules and states determine how the states should interact with each other and resolve regional issues. Instead, states which are more powerful (i.e. the hegemon or great powers) determine their relations with weaker states including how the weaker states should behave. They also determine how regional issues should be resolved.

The hegemon or great powers could do this in several ways. They could decide how to treat other states or handle certain issues in an ad-hoc, case-by-case basis. They could also impose a set of rules and institutions on smaller states which maximizes their interests. Under a power-based order, the hegemon or great powers are not constrained by these rules and institutions and can change them whenever they like. Smaller states are coerced to comply by the decisions of the hegemon or great powers or the rulesand nstitutions they set up even though these may not be in their interests.

It is important to know that both rules and power-based governing logic are underpinned

by particular values. In a rule-based order, values are important because they determine the content

of the rules beyond the emphasis that there should be some degree of equality among all states. In a rule-based order, the values are shared among all the states and constitute their "sense of common interests in the elementary goals of social life," using Bull's words.2 8 For instance, the United States-led liberal order includes certain underlying values, such as the beliefs in free trade, democracies and human rights. With these values in mind, there are rules within the liberal order against states erecting trade barriers to block free trade or carrying out repressive or genocidal activities against their people. In a power-based order, values are important because they determine sources of authority that could generate power beyond states' material capabilities. David Lake cited Max Weber to note that there are several forms of authority that are relevant in international

relations, namely tradition, religion and charisma.2 9 These sources of authority constitute the values in a power-based order. For instance, certain states have traditional source of authority as they are recognized as the leader in a region for a very long period of time. Imperial China is such an example. Before its hundred years of humiliation, China was seen as the center of civilization

28 Ibid

29 Lake, A. David. (2010). Rightful Rules: Authority, Order, and the Foundations of Global Governance. International

in Asia and built a tributary system with neighboring countries. Other states could be seen as a leader due to ideology or religion. For instance, China during Mao's time was seen as one of the leaders in the communist world given its promotion of the Marxist-Leninist ideology. Egypt under President Gamal Abdel Nasser was seen to be the leader of the Arab world given Nasser's success in championing the ideology of Nasserism, a socialist Arab nationalist political ideology.

There are again a few possible variations of rule and power-based orders based on the nature of rules setting and enforcement as well as the degree of institutionalization in the order. Beyond the question of whether all states have a voice in setting the rules, there are differences in how rules can be made and enforced. On the one hand, rules can be made through well-defined procedures, are binding on the states which agreed to them and are strictly enforced. On the other hand, rules can be made in an ad hoc manner (e.g. through backdoor negotiations), are not binding on states and are loosely or not enforced at all. The contrast between the different ways of rule-making and enforcement can be seen in Western and Asian multilateral institutions. As Michael Yahuda noted, "unlike western multilateral institutions which are characterized by rule-making and procedures for rule enforcement, such institutions in Asia tend to be defined by voluntarism and consensual decision-making." 3 0 There can also be different degrees of institutionalization. As Chien-peng Chung noted, "institutionalization usually involves specifying functional goals, creating a number of behavioral norms, progressing to formal rules, and extending the process to include concrete entities like permanent committees, staffs, budgets and internal procedures that can shape policies or norms."3 1The contrast can again be drawn between the Western and Asian

30 Michael Yahuda, "China's multilateralism and regional order" in Guoguang Wu and Helen Lansdowne, ed., China

turns to multilateralism: Foreign policy and regional security (London: Routledge, 2008), p.7 6

1 Chien-peng Chung, China's multilateral cooperation in Asia and the Pacific: Institutionalizing Beijing's "Good

multilateral institutions. In Asia, multilateral institutions such as ASEAN often play a more limited role of regularizing interactions between states with little independent power to shape policies or norms.3 In Europe, the European Commission plays a significant role in designing and implement policies across the whole European Union.

The variation in the nature of rules setting and enforcement as well as the degree of institutionalization translates into different types of governing logic for the order (see Figure 2 below). On one end, we have the pure rule-based order where rules are made in well-defined procedures involving all states. The rules are binding on all states including the hegemon or great powers even though they constrain their power and options. The hegemon or great powers enforce the rules stringently with the assistance of other states. There is often a high level of institutionalization in this ideal type, with the presence of strong and independent multilateral institutions. These institutions have their own budget and staff and have the power to formulate independent policies. On the other end, we have the pure power-based ideal type where all issues within the order are determined by the most powerful state or group of states. In such an order, there are no commonly accepted negotiated rules and institutions. If there are any rules and institutions, they are decided by fiat by the hegemon or the great powers in the region. The hegemon and great powers use their military power to coerce smaller states to comply or

join

these rules and institutions. In the middle, we have a limited rule-based order which is a hybrid between the rule-based and power-based orders. In this type of order, there are some rules governing state-to-state interactions and key issues. These rules are set by all states although the more powerful states have a bigger voice (the degree of procedural fairness is lower compared to a purerule-32 Although ASEAN has a secretariat, it plays more a coordinating and implementing role on policies that are agreed

based order). The rules are made in less structured settings (for example in negotiations among states), are generally either broad or vague (more like statements of principles or norms than specific rules) and are not binding on the states. There are also no specific mechanisms to enforce the rules against those that contravene them beyond pressure from other states. Multilateral institutions in this hybrid order have less independent power, and play a more limited role in

shaping policies.

Figure 2: Governing Logic: Rules vs Power

Rule-based: Dominance Limited Rule-based: Power-based: No

of negotiated rules and Limited negotiated negotiated rules and

institutions rules and institutions institutions

4. Ideal types of regional orders

By considering the two parameters together, I am able to conceptualise the different types

of ideal orders. Theoretically, the number of types of ideal orders is infinite because there is a continuous range of values for both parameters. For simplification, I divide up each parameter into three values as highlighted above. By doing so, I have come up with nine ideal types of regional

Figure 3: Typology of regional orders Governing Logic: Rule vs Power

Rule-based Limited rule-based

A 0 Power-based 0 0 0 cj~ 0 0 0. 0 0 0

Type 1: Hegemon-led Type 2: Hegemon-led Type 3: Hegemonic

community based on arrangement based on rule based on power and

rules and institutions limited rules and with no commonly

institutions agreed rules and

institutions

E.g. US-led NATO E.g. US alliance system E.g. USSR-led Warsaw

in East Asia Pact

Type 4: Great powers- Type 5: Great powers- Type 6: Great powers

led community based led arrangement based rule based on power

on rules and institutions on limited rules and with no commonly

institutions agreed rules and

institutions

E.g. European Union E.g Concert of Europe E.g. Europe pre-WWI

Type 7: Democratic Type 8: All states-led Type 9: All states rule

community based on arrangement with based on power with no

rules and institutions limited rules and commonly agreed rules

institutions and institutions

E.g. ASEAN-6 (before E.g. China during

expansion) Spring-Autumn period?

A hegemon-led community based on rules and institutions (Type 1) is one where one state

(the hegemon) is much more powerful than other states in the region and decides to create and maintain a regional order using rules and institutions. The hegemon's source of power could come from its material capabilities as well as other sources of authority such as being a recognized leader

by tradition, religion/ideology or soft power. The hegemon chooses to work with the other states tocomeupwith a set of rules and institutions that is acceptableto all. Underlying the order isa set

of values that is commonly embraced by all the states in the order. An example that approximate this type of order is the US-led liberal order in Europe. Post-WWII, the US promoted an order based on values of free trade, democracy and human rights which are first supported by the other western countries. Based on these values, the US worked with the western countries to create

NATO, a collective security multilateral institution to protect against aggression from the

communist USSR (NATO).

A hegemon-led arrangement based on limited rules and institutions (Type 2) is similar to

Type 1 in that one state (the hegemon) has much more power than other states in the region. The hegemon chooses to work to with other states to come up with a limited set of rules and institutions. Because these rules are less binding and enforceable and the institutions are less independent than those in Type 1, they only bound the hegemon and other states to some extent. Underlying the order is a set of values that is embraced by or at least not opposed by all the states in the order. An example that approximate this type of order is the US-led alliance system in East Asia. Compared to the multilateral institution NATO that the US created in Europe, it chose to build institutionalized bilateral relations with key countries in East Asia through alliances. As Ikenberry noted, this difference is due to the US needing less out of the East Asian countries given its "much

more unchallenged hegemonic power in Asia than in Western Europe."33 He also noted Victor Cha's argument that the US also feared "entrapment and collusion of East Asian states."34

A hegemonic rule based on power and with no commonly agreed rules and institutions

(Type 3) is similar to Type 1 in that one state (the hegemon) is much more powerful than other states in the region. But the hegemon uses its power instead of rules and institutions to create and maintain the regional order. Relations between states and decisions on issues within the order are determined by the hegemon's preference. The hegemon might decide to rule the order using rules and institutions but these are tools used to govern the smaller states and do not pose any constraints to the hegemon. As with Type 1, the hegemon's source of power could come from its material capabilities as well as other sources of authority like tradition, religion/ideology and charisma and the hegemon uses them to sustain the regional order. An example that approximate a hegemonic rule based on power is the USSR-led Warsaw Pact. Even though there are rules and institutions within the Warsaw Pact where all the communist states are supposed to have a voice and role, the

USSR dominates over other states due to its much larger material capabilities and perceived

leadership of the communist bloc. The USSR also imposed its will on other states including invading Czechoslovakia in 1968 with the justification that it had the right to intervene in any country where a communist government had been threatened (known as the Brezhnev Doctrine).

A great powers-led community based on rules and institutions (Type 4) is one where a few

major countries are much more powerful than other states in the region and decides to create and maintain a regional order using rules and institutions. Again, these great powers' power could come from their material capabilities and other sources of authority. An example that approximate

11 Ikenberry, Liberal Leviathan, p. 101

this type of regional order is the current European Union where the great powers like Germany, France and Italy worked with other smaller European states to form a community of European states based on common liberal values. Within the EU, there are well-defined procedures to formulate policies across all the member states. The European Commission, as noted earlier, has strong independent powers to design and implement policies. A great powers-led arrangement based on limited rules and institutions (Type 5) is similar to Type 4 in having several great powers in the order although the degree of rules and institutionalization are more limited. An example that approximate this type is the Concert of Europe in the 19th century where the major European states of Great Britain, France, Austria, Prussia and Russia agreed to a set of rules to jointly ensure the stability of European. These rules included recognition of each other as great powers, agreeing to consult each other to establish and redefine the political and territorial boundary for Europe and the setting up of a mechanism for consultation and dispute resolution. Compared to the EU, these rules are more general and vague and are left to the great powers to comply voluntarily. There are also no multilateral institutions with independent powers in Europe during that time.

A great powers rule based on power with no commonly agreed rules and institutions (Type 6) is similar to Type 4 in that a few major countries have much more power than other states in the

region. But these great powers either choose not to or could not agree to cooperate jointly and use rules and institutions to create and maintain a regional order. Instead, they compete within the regional order using their own power, to either protect and expand their national interests or to achieve certain goals. As each great power tries to advance its national interests/goals and block other states from achieving theirs, this creates a balance of power within the regional order. An

3 Lascurettes, Kyle, The Concert of Europe and Great-Power Governance Today: What Can the Order of 19th-Century Europe Teach Policymakers About International Order in the 21st 19th-Century?. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE226.html. Also available in print form.

example of this type of regional order is the situation in Europe pre-WWI when the Concert of Europe has broken down and the great powers resort to growing their own capabilities and allying with other great powers to prevent their enemies from becoming dominant in the continent.

A democratic community based on rules and institutions (Type 7), an all-states led

arrangement with limited rules and institutions (Type 8) and an all states rule based on power with no commonly agreed rules and institutions (Type 9) are more uncommon type of regional orders. In these order, all states have similar level of power and there are no one or several states which are much more powerful than other states. This is uncommon because historical developments and geographical usually results in disparity in capabilities among states in the same region. In terms of the governing logic, states in the Type 7 order are able to agree to cooperate under a commonly agreed set of rules and institutions. Arguably, this is probably more difficult to achieve than the Type 8 where the states might just agree on some limited rules and institutions or Type 9 order where states compete with each other to protect and expand their national interests and goals with no rules and institutions. This is because it is harder to get consensus among a large group of states with different and sometimes conflicting national interests to agree to specific set of rules which are binding and enforceable. These states are also unlikely to give up any sovereign powers to an independent institution since their similarity in power is likely to lead them to be careful not to upset any balance of power. There did not appear to be any examples of a Type 7 regional order. An example of a Type 8 regional order could be the six ASEAN states prior to 1995. The six

ASEAN countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Philippines and Brunei) have

similar level of power and worked together with limited rules and institutions. They created the

ASEAN way of decision-making which emphasize consensus among all states and created ASEAN as a platform to encourage interactions and cooperation among the various states. An

example of a Type 9 regional order could be the group of small states in China under the Spring-Autumn period. During that period, the power of the Zhou dynasty has waned significantly and the lords of the hundreds of vassal states began to jostle among themselves for power and territory.

5. Some issues regarding regional order

In this section, I will try to clarify some issues regarding the typology and how it can be

applied. First, I will address potential confusion on some apparent contradiction between distribution of power and governing logic. Second, I will address the difference between the power-based governing logic and balance of power in the distribution of power. Third, I will look at whether regional order can exist only in one realm (political, economic, security). Finally, I will

discuss whether states are constrained by material conditions in reshaping the regional order.

Apparent contradiction between distribution ofpower and governing logic

Is there an inherent contradiction in a hegemon or great powers-led rule-based order? Can power be concentrated within one or several states even when rules are made and supported among all the states in the order? I argue that there is no contradiction between the two. The assumption behind the contradiction is that interactions between states in an order is inherently zero-sum. A state or several states that are much more powerful would try to maximize their interest in the order and this must be opposed by other weaker states that try to protect their own interests. Hence a hegemon or great powers-led order cannot be rule-based using my definition of rules. It can only be a power-based order where the hegemon or great powers impose a set of rules and institutions on the other states. However, as we see from the United States-led liberal order, this assumption

is not true. The problem is that the zero-sum assumption is wrong. Interactions among states may not be zero-sum. States may choose to cooperate and bind themselves in rules and institutions if what they get from such cooperation is greater than what they can get on their own without cooperation. In addition, states can perceive their interests differently. As Ikenberry noted, hegemon or great powers may see it in their interests to create a rule-based order where other states have a voice in rule-setting so that these states are supportive ofthe order.Tisreducesthecosts of maintaining the order and entrench the hegemon or great powers' influence in the order against potential competitors in the future. The hegemon or great powers may see these benefits as more than offsetting the costs of having to constrain their power in the order. On the other hand, smaller states may choose to support a rule-based order where the hegemon or great powers still enjoy significant influence to insure against potential worse excesses that they may suffer if the hegemon or great powers are able to exercise their power without any constraint.3 6

Power-based governing logic vis balance ofpower

Is a power-based governing logic the same as a balance of power distribution of power? I argue that they are fundamentally different. A power-based governing logic just means that power is the key determinant of state-to-state relations and outcome of state interactions. Countries use their power to get what they want from other states and influence the outcome of regional issues. A power-based governing logic does not only happen in regional orders with a balance of power. A hegemon-led order where no balance of power exist, can also operate on a power-based governing logic. Conversely, a balance of powerjust means that the states either engage in internal

or external balancing behavior against other states in the order to prevent any one state from dominating the system. This balancing behavior can take place in orders with either power-based or rule-based governing logic. In an order with power-based governing logic, states will primarily rely on material capabilities to balance against other states. But in an order with rule-based governing logic, states would also rely on devising rules and institutions that prevent other states

VI Lf L'J r af,

r%11Tf-from having the opportunity to dominate now or the future.

Regional order across different domains

Does a regional order exist only in a particular domain or across domains (political, economic, security)? The concept of regional order is often applied in the security domain where it is linked to the idea of a regional security complex (RSC). Buzan & Waver defined RSC as "a group of states whose primary security concerns link together sufficiently closely that their national securities concerns cannot reasonably be considered apart from one another."37 Many of the academic writings on regional order has focused on a security order such as the US-led alliance system in East Asia or NATO in Europe. But other academics also see regional order beyond the security domain. Katzenstein see regional order as "social and institutional environments" where "power inheres."38 These environments are created by"powerful states" who tried to "extend their purposes beyond national borders through a combination of strategic action and sheer weight."39 Katzenstein considered regional order both in the security and the economic realm. It would also be worth mentioning that regional order has also been discussed in the study of regionalism.

37 Buzan and Waver, Regions and Powers, p. 44

38 Katzenstein, A World of Regions, p. 21-22

Andrew Hurrell and Louise Fawcett noted how "regionalism and regional organizations can contribute positively to the provision of order and stability within a particular region."40

Can a regional order exist only for one realm (political, economic, security) or does it have to exist across all the domains? Can there be different regional orders in different domains in the same region in the same period of time (e.g. a United States-led security order and China-led economic order in East Asia)? I argue that a sustainable regional order needs to exist across all different domains although the strength of the order might vary across the domains. This is because power, the key determinant of the distribution of power in the regional order, is made up of

different components including material capabilities, legitimate authority etc. These different components come from the different domains and reinforces each other. Historically, we have seen many more cases of international and regional orders built across different domains. For example, the British empire in the 19th century drew its strength from its navy (military), trading fleets (economic) and colonies (political). The United States-led order in East Asia has lasted for several decades because of strong political and economic ties with East Asian countries (political and economic) and its alliance system (military). The rare exception is probably Japan post-WWII where it created some sort of East Asia economic order while being under the US security umbrella. But even this exception comes with many caveats as the United States was still deeply involved economically in the region and United States-Japan post-WWII relationship is rather unique and unlikely to be replicated by other states.

0 Andrew Hurrel and Louise Fawcett, "Conclusion: Regionalism and International Order?" in Regionalism in World