Partner Selection Process for a Swiss medical

equipment start-up

Bachelor Project submitted for the degree of

Bachelor of Science HES in International Business Management by

Coralie DELACOSTE

Bachelor Project Mentor: Philip Willson, HES lecturer

Geneva, 2nd of June 2020

Haute école de gestion de Genève (HEG-GE) International Business Management

Disclaimer

This report is submitted as part of the final examination requirements of the Haute école de gestion de Genève, for the Bachelor of Science HES-SO in International Business Management. The use of any conclusions or recommendations made in or based upon this report, with no prejudice to their value, engages the responsibility neither of the author, nor the author’s mentor, nor the jury members nor the HEG or any of its employees.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all the people who contributed to this Bachelor thesis by sharing their time, knowledge and expertise.

Firstly, Laurent Sache and Denis Chambert at Pristem that were available to meet both physically and digitally and always ready to help in explaining the company’s strategy, product and vision. Your concrete knowledge was precious to apply the theoretical tools I selected and your constructive review on my work allowed me to improve its quality. I also thank the entire Pristem team that accepted to collaborate with me on this work and was always welcoming.

Secondly, I wish to thank my mentor, Mr. Philip Willson for raising the difficult but appropriate questions during our meetings and for answering to my interrogations related to supply chain management.

Thirdly, thank you to Mr. Alexandre Caboussat for racking your brain with the data analysis and visualisation part of my work. Your availability considering the special crisis we went through was truly appreciated.

Finally, I want to address my acknowledgment to my family and friends who contributed in their very own way to this project by supporting me, correcting my work and helping me to forget about it from time to time.

Executive Summary

This Bachelor thesis intends to answer to the need of a medical equipment start-up company which has to select a partner to perform the role of integrator in its global supply chain. This is a typical partner selection problem that is addressed in this work through a linear weighting model integrating both qualitative and quantitative variables. The criteria are selected by reviewing the state of the art and in agreement with the start-up’s management.

Analysis of the environment, culture and partners’ organisation and production are firstly conducted in order to have an overview of each partner’s context. These reviews are the foundation this project relies on to perform the evaluation of each company. They are also the base to recommend guidelines for the partnership contract negotiation and management that are the steps following this work.

The goal of this Bachelor thesis is to provide a Swiss medical equipment start-up with a simple but complete decision-making tool that can be used outside of the current academic scope. It can be used with the corresponding information available to the start-up. It also allows the start-up to easily make changes in the list of criteria, their indicators and weighting or the evaluation of each partner if new information appears or if the situation changes.

One partner stands out of this evaluation and is thought to be the best match considering the start-up’s requirements. The main risks and opportunities highlighted thanks to the previous analysis are further developed for the selected partner. It grants the start-up with a thorough preparation for the next steps of negotiation and design of the partnership contract and highlights what needs to be monitored by the start-up in order to get as much as possible from this partnership. The model also enables the exclusion of some companies from the pool of candidates in order to focus the start-up’s efforts on the remaining prospective partners.

Contents

Partner Selection Process for a Swiss medical equipment start-up ... 1

Disclaimer ... i

Acknowledgements ... ii

Executive Summary ... iii

Contents ... 1

List of Tables ... 3

List of Figures ... 3

1. Introduction ... 4

1.1 Subject of the work and scenarios ... 5

1.2 Bachelor thesis question and objectives ... 7

1.3 Theoretical concepts ... 8

1.4 Organisation ... 8

2. Literature review ... 9

3. Methodology ... 14

3.1 Criteria selection and weighting ... 14

3.2 Candidates’ evaluation ... 19

3.3 Partner selection and further considerations ... 21

4. Analysis ... 22 4.1 PESTEL Analysis ... 22 South Africa ... 22 France ... 25 4.1.3 Hungary ... 27 Italy ... 30 4.2 GLOBE Results ... 33

GLOBE Cultural Values Analysis ... 33

GLOBE Outstanding Leadership Analysis ... 37

4.3 Company description ... 39

Company A - Italy ... 39

Company B - France ... 40

Company C - Hungary ... 42

Company D – South Africa ... 43

Company E – South Africa ... 45

4.4 Production ... 46

Company A- Italy ... 47

Company B - France ... 47

Company C - Hungary ... 48

Company D – South Africa ... 49

Company E – South Africa ... 49

5. Results ... 51

Company A - Italy ... 51

Company B - France ... 52

Company C - Hungary ... 53

Company D – South Africa ... 54

Company E – South Africa ... 55

5.2 Criteria indicators and candidates’ evaluation ... 56

6. Discussion ... 60

6.1 Chosen model and methodology ... 60

6.2 Selected partner ... 62

6.3 Final considerations ... 67

7. Conclusion ... 68

Bibliography ... 70

Appendix 1: Criteria, indicators and candidates’ evaluation ... 76

Appendix 2: Weight factors ... 77

Appendix 3: Macro VBA ... 79

Appendix 4: Weighting scenarios and final score ... 80

Appendix 5: Labour cost calculations ... 82

Appendix 6: GLOBE results and computed differences ... 83

List of Tables

Table 1 - GLOBE Values scores ...34

Table 2 - GLOBE Outstanding Leadership results ...37

Table 3 - Abstract criteria and scales table ...57

Table 4 - Abstract of candidates’ evaluation ...58

Table 5 - Candidates’ final score for selected weighting scenario ...59

Table 6 - Extract of subsidiary’s financials ... Erreur ! Signet non défini.

List of Figures

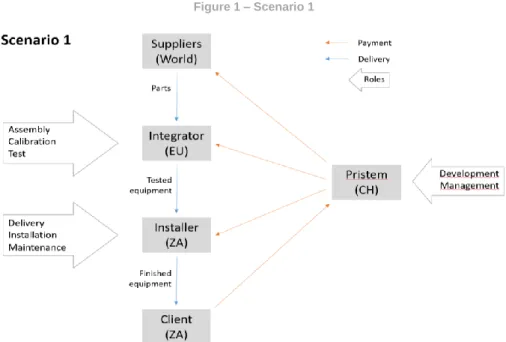

Figure 1 - Scenario 1 ... 6Figure 2 - Scenario 2 ... 6

Figure 3 - Outsourcing lifecycle model...14

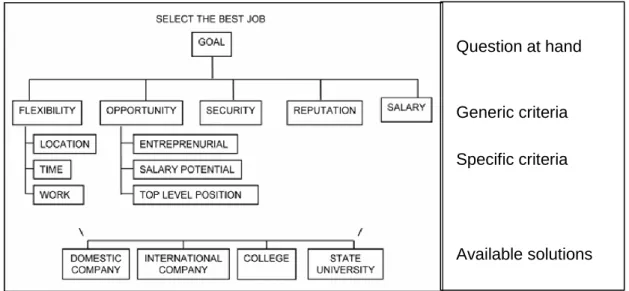

Figure 4 - Saaty’s example of simple decision ...18

Figure 5 - Quality Likert scale with five levels ...20

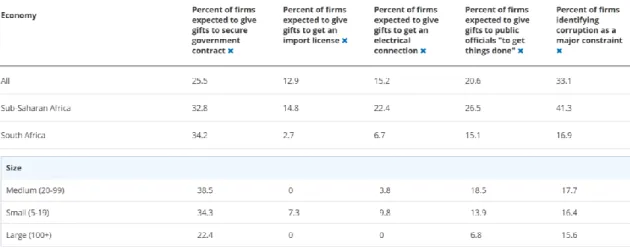

Figure 6 - Details of South Africa corruption table ...22

Figure 7 - Change South African Rand – US Dollar over one year ...24

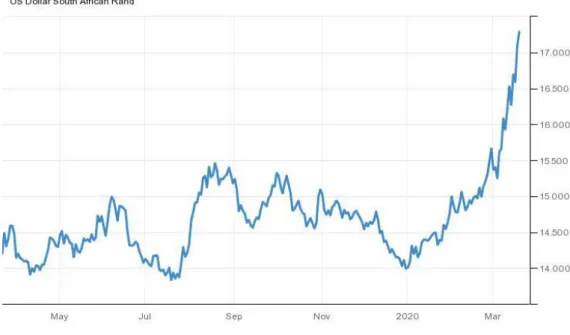

Figure 8 - General topics scores for South Africa ...25

Figure 9 - General topics scores for France and South Africa ...26

Figure 10 - Change Hungarian Forint – US Dollar over one year...28

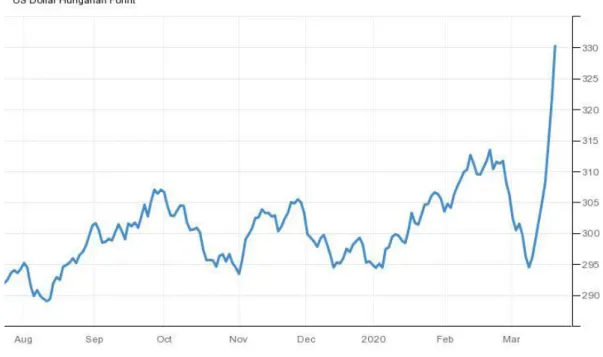

Figure 11 - Government Integrity Score ...30

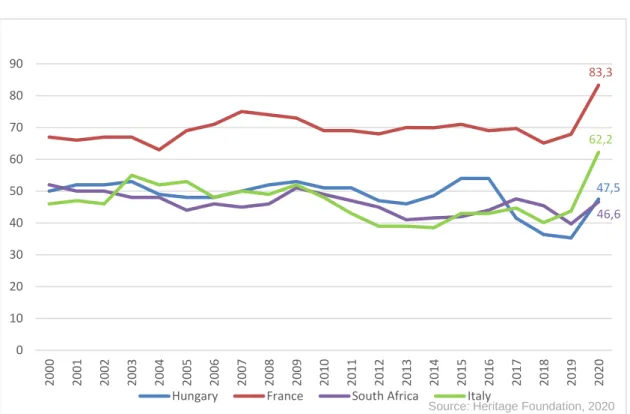

Figure 12 - Culture groups map ...32

Figure 13 - Culture groups map ...33

Figure 14 - Countries’ differences with Switzerland ...35

Figure 15 - Countries’ differences with South Africa ...36

Figure 16 - Extract of Company B’s financial statement ...41

1. Introduction

Pristem SA, hereafter mentioned as Pristem is a Swiss based start-up engaged in providing “world-class medical technologies specifically designed for [their] unique environments” (Pristem SA 2020).1It was founded on the 9th of December 2015 but is

the spin-off of a previous project called GlobalDiagnostiX and conducted by EPFL’s EssentialTech program started in 2012. This project aims at developing an X-Ray system with local integrators for hospitals in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries. Such equipment needs to answer to specific needs like:

Robustness of the design and IT system in order to withstand power outages, humidity, heat and dust.

Easiness to use and repair due to the lack of training of local workers.

Affordable total cost of ownership considering the target market (Global DiagnostiX 2020).

Pristem continued the work of GlobalDiagnostiX, keeping these requirements in mind and is developing an “all-in-one fully digital X-ray system” with Swiss engineering excellence. The company also provides options of high-quality maintenance services and digital health services.

Pristem’s mission of “strengthening primary health care globally by supplying high performance, extremely robust and cost-effective medical systems and ensuring that they operate effectively over extended life-cycles” summarizes well the company’s product and service offering. To complete that mission, Pristem created a manifesto of six core principles to keep in mind for every employee or partner involved in the project: Global impact thanks to the diffusion of basic medical equipment adapted to local

environments.

Superior efficacy by offering state of the art and secure systems. Zero downtime and long service lives for its products and services. Lasting solutions through high-quality equipment and services.

1 All information used in this introduction about Pristem SA, its products and its strategy is

based on information found on their website or collected through discussions with L.Sache and D. Chambert, respectively COO and Supply Chain Manager of Pristem SA, Lausanne, February 2020

Cutting-edge innovation through a culture supporting creativity and change. Global teamwork and collaboration in an open-minded and cooperative

atmosphere.

After receiving recognition lsuch as the PricewaterhouseCoopers prize for Future Trends at Seif Awards 2015 and the “Coup de Coeur” prize at the PERL Awards in 2017 Pristem raised 14 M Swiss francs to start the large-scale production of its radiology solution. The advanced technology used in this equipment is protected by various patents and its quality management system successfully completed the evaluation to get the ISO-13485 certification in late 2019.

1.1 Subject of the work and scenarios

One of the following steps for Pristem is finding a partner to integrate its equipment. The first part of the partner selection process that includes definition of the start-up needs and screening for potential partners has already been conducted by Pristem. This work follows the process by analysing and comparing the potential partners and selecting the most appropriate one (Kinnula 2004). At this point, a clarification needs to be made: the integrator is a partner which implements the production process (assembly and final calibration of the X-Ray parts of the final product) and is responsible for ramp-up to large scale production (around 150 units a year). Some of the components are directly sourced by the integrator if economies of scale are possible and the rest are purchased by Pristem. After testing, the components are disassembled, packed and sent to the installer in South Africa. The integrator will be based either in Europe (Italy, France or Hungary) in scenario one or in South Africa in scenario two, depending on the results of this work. In the latter option, the installer and integrator could be one unique entity.

In all scenarios, the installer is a player present in SADC countries. It is in charge of receiving parts either from Pristem or its integrator to install and perform the last tests of the solution at the customer location. This company is also in charge of repairing and maintaining the medical equipment. Flowcharts present the two scenarios hereafter to ease the understanding.

In scenario one, the integrator is based in Europe, in France, Italy or Hungary and the supply chain contains five actors. The installer is located in South Africa and parts are being sent to him after calibration and testing.

In scenario two, the integrator and the installer are both located in South Africa. The two actors could be reunited in one entity to ease the process and reduce the number of intermediaries. This unique entity would be in charge of calibrating, testing, installing and maintaining the system.

It is also important to make a distinction between the two candidates in South Africa. The first one, Company D is an external partner just like for the European ones. The second

Figure 1 – Scenario 1

Figure 2 – Scenario 2

Source: based on interview with L. Sache and D. Chambert, 2020

South African partner, Company E represents Pristem’s opportunity of having its own internal integrator based in South Africa through an acquisition. Finally, Pristem is thinking of taking the assembly process back in house in its own premises in South Africa in a few years providing the production is stable. Pristem also has a strategic plan of integrating the European market with its X-ray solution once its business is stable in South Africa. These two long-term visions have to be taken into account when analysing the risks and benefits or each partnership.

1.2 Bachelor thesis question and objectives

This Bachelor thesis intends to help Pristem’s Chief Operations Officer in the partner selection process with the help of supply chain management tools and theories. The research question translating this task is the following:

How can supply chain theory be applied to provide a robust partner selection process for a Swiss medical equipment start-up serving the healthcare sector in SADC

countries?

In order to answer to this question two research objectives were defined:

First, qualitative and quantitative analysis of the five considered options and two scenarios are conducted. The country and culture in which the candidates operate are analysed along with the companies’ organisation and production. Second, a specific linear weighting model is designed and completed by a

sensitivity analysis with various weight repartitions. Candidates are evaluated based on the previous analysis conducted and on selected criteria approved by Pristem and the literature review on the subject. The best fitted partner is selected via this decision-making tool and further considerations are reviewed concerning the risks and opportunities of the specific partnership as part of Pristem strategy. Note that due to the general slowdown the COVID-19 virus caused, Pristem does not possess all the concrete information on the partners that was planned initially. In fact, the start-up will receive the prospective partners’ quotes only after the end of this work and some numbers and information such as price are thus for now estimations of what the reality could be. The goal of this work is to provide the start-up with a tool it can easily use and modify in its subsequent decision-making processes. Further offers and quotes information can be added to the model in order to complete the set of criteria and get a more accurate analysis of the partners.

1.3 Theoretical concepts

Due to the current fast-moving economy, companies often choose to focus on their core competences and outsource the rest of their value chain. One of the existing outsourcing strategies is outsourcing partnership, which is when “one company transfers part of its business to another company and after that the companies continue collaboration in a partnership mode” (Kinnula 2004, p. 1). This is the strategy selected by Pristem regard to its future assembly partner. The goal is to collaborate with the partner on the product introduction and production process. This kind of manufacturing outsourcing method generates many risks since the final product will be Pristem’s first and flagship product and given that the services quality claimed by the partner can be fully assessed only once realised. However, there are various ways to identify and mitigate these risks through both quantitative and qualitative analysis. The Partner Selection Problem is a long-studied optimisation problem that has been addressed with the use of various variables or variable sets and resolved using numerous models and methods (Niu, Ong, Nee 2012; Huang et al.2018; Ávila et al. 2012). Many risk analysis on collaboration, communication and proximity levels have also been conducted in order to identify the pain points of an international outsourcing relationship (Tang, Nurmaya Musa 2011; Kinnula 2004; Schmitt, Van Biesebroeck 2013).

1.4 Organisation

This introduction presents the company and the research problem and objectives. Then the work is divided in four parts: first a “Literature review” presents the past and current knowledge and works on the main themes addressed in this thesis. The “Methodology” section explains how and why such analysis is selected, its step-by-step process and references the criteria selection based on best practices and Pristem’s needs. The second part of the work, “Analysis”, contains general analysis of the partners’ country, culture, internal structure and production. Partners are then evaluated on each criterion in the third section of the paper, called “Results” which also contains the decision-making model defining the most appropriate partner for Pristem. The last part of this paper is dedicated to a “Discussion” on the model used, the results found and the additional considerations to make in relation to the latter. A “Conclusion” resumes the findings, the hurdles and further opportunities that have been mooted throughout the elaboration of this work.

2. Literature review

Supply chain management is a broad subject that has been analysed and discussed multiple times in history and from various points of view. It was first mainly about logistics and transportation but it then expanded and incorporated many other aspects like inventory management, contract settlement or globalisation. According to the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (2020), supply chain management includes “the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement, conversion and all logistics management activities”. These activities range from the sourcing of raw material to the distribution of the product to the final customer and its after-sale services. Often, these diverse steps are conducted by different companies interlinked by alliances and partnerships. In a global supply chain, the actors are dispersed around the globe, which increases the risks of mismanagement and miscommunication.

In today’s dynamic, global and highly competitive economies, business collaboration is an opportunity for companies to be more agile, focus on one’s core competencies by leveraging the strengths of each partner and is a means to reduce competition (Mat, Cheung, Scheepers 2009). For start-ups it is also a way to grow without being limited by the barriers of initial resources or capabilities for non-core competences such as limited operational know-how or high resources requirement (Bustamante 2019). These collaborations can take many types; outsourcing partnership is one of them, which “transfers part of the business to another company and then both businesses continue collaboration in a partnership mode” (Kinnula 2004). The company and outsourcer have a closer relationship than just the supplier-client type. The part of business transferred can be any business task that is non-core. In this work focus is set on manufacturing-type outsourcing partnerships.

Manufacturing a product is an important process in a business and it can be divided in different tasks; generally planning, development, design, testing and production ramp-up (Javadi, Bruch, Bellgran 2016). These tasks have considerable influence on the time to market, cost and quality of a product and many disturbances are usually encountered at this stage (Araz et al. 2007).Additionally, the first commercialized product is a crucial milestone for a start-up and its success or failure positions the firm for the future. The outsourcing partnership therefore needs to be closely monitored and the manufacturing partner should be diligently chosen. As a matter of fact, harvesting the advantages of collaboration is not easy and many partnerships end up having few or no positive effects or are faced with trade-offs (Bengtsson, Haartman, Dabhilkar 2009). Outsourcing is a

major strategic decision that impacts the entire organisation and which is costly and very difficult to reverse (McIvor 2005). Moreover, failure to coordinate the entire supply chain may result in excessive delays, poor customer service and thus rising costs for all the actors in the supply chain (Eon-Kyung Lee, Sungdo Ha, Sheung-Kown Kim 2001). Once the decision of outsourcing is taken, the subsequent steps are “supplier selection, contract negotiation and the transitioning of assets to the supplier” (McIvor 2005, p. 7). This paper focusses on the supplier selection part. Indeed, running a thorough partner selection process is one way of decreasing the risk of outsourcing partnership failure mentioned above.

The first step in any partner or supplier selection process and a crucial one is the selection of variables to assess the candidates on. They then can be divided into sub-variables, defined with indicators when possible and grouped into key and secondary criteria to ensure a detailed selection process. In the literature review, multi-criteria models are generally used in partner selection process as they allow to review a partner under different variables, which analysis can complete, reinforce or contradict each other. Indeed, outsourcing strategies are not fuelled anymore by cost reduction opportunities only but rather by technological and strategic motives, like efficiency in adopting new technologies or better copying with product demand (McIvor 2005). These motives have many possible indicators and are often mixed to create the perfect decision set.

In his early work on partner selection process, Dickson (1966) listed 23 criteria on which managers base their selection process. This work builds the theoretical foundation for many subsequent articles that try to identify the most important criteria for each industry and situation or to complete the initial list. The most used and agreed upon criteria for partner/supplier selection process in the state of the art are quality, cost and delivery (Eon-Kyung Lee, Sungdo Ha, Sheung-Kown Kim 2001; Talluri, Narasimhan 2003). Weber et al. (1991), after reviewing 74 related papers, also conclude that quality was the most widely used and important criterion, followed by delivery and cost performance. However, these three criteria are often judged not to be enough if used alone. Eon-Kyung et al. (2001) underline the importance of aggregating financial stability, technology and design capabilities, compatibility of the top management and location of production facilities to the decision process. Araz et al. (2007) add capacity utilization and Luan et al. (2019) advise adding partner’s innovation and development to the usual criteria. Another group of researchers decided to integrate qualitative criteria to the list such as reputation and risk (Niu, Ong, Nee 2012), personal judgment (Samut, Erdogan 2019) or

integrity and commitment (Mat, Cheung, Scheepers 2009). In their work, Ellram et al. (2002) underline the importance of adding compatibility of management and strategy orientation to the usual criteria. Eon-Kyung et al. (2001) agree and add cultural compatibility to the list. Indeed, supply chains with close relationships and a common goal are recognised to produce better results and even create competitive advantage and this is more easily achievable when personal and corporate culture are similar (Tsai, Yang, Lin 2010; Samut, Erdogan 2019).

Moreover in the present research that presents a situation of low volume manufacturing outsourcing, communication is essential to secure a smooth product introduction and a production without defects. In fact, it was observed in the field that the main disturbances in production are due to missing or incorrect information which could be prevented with efficient communication (Javadi, Bruch, Bellgran 2016).

A start-up strategy of early outsourcing is also a set-up that encourages transparent and continuous communication processes. The product, its qualities and design are given by the start-up but the production process comes mainly from the partner. It is very important that these two requirement sets match each other. Manufacturability of the product is often a pain point when the designer is not the manufacturer (Javadi, Bruch, Bellgran 2016) and even more when they are geographically distant (Classen, Lopez 1998). Once again, a close partnership is key to the success of the enterprise. Building close relationships includes creating high mutual trust and communication processes are eased when the partners naturally understanding each other. These cultural, inter-organisational and inter-personal relationships can be analysed only through qualitative data, which is why decision was taken to include them in this research.

Once variables, both quantitative and qualitative, have been selected the time comes to choose a model to solve what is called the partner selection problem. Literature review underlines five main options at this stage: linear weighting models, statistical approaches, mathematical programming models, artificial intelligence and hybrid models (Dimitris 2012).

One of the first mentions of a mathematical partner selection problem is in Talluri and Baker’s work (1996) with a two-phase mathematical programming approach including the variables of time, cost and geographical distance. Later, with the development of computer science and specifically the widespread use of artificial intelligence use in business analysis, literature on the partner selection problem expanded exponentially and the algorithms and models used to solve the problem became more and more complex. Artificial intelligence and hybrid techniques are assuming an increasing

importance in modern literature because they allow one to integrate a higher number of variables or variable sets and subsets with more complex relations between them. It also translates the uncertain and dynamic environment of globalised supply chains more accurately (Chai, Liu, Ngai 2013).

However, integrating intangible (qualitative) data into mathematical programming has always been a challenge for scientists and researchers (Eon-Kyung Lee, Sungdo Ha, Sheung-Kown Kim 2001). In recent years, some researchers tried to do it by transforming the qualitative data into quantitative using fuzzy numbers (Niu, Ong, Nee 2012) or through a fuzzy analytical network process (Samut, Erdogan 2019). But these fuzzy processes and the resulting models are complex and other models like linear weighting enable integration of both quantitative and qualitative criteria into the selection process much more easily (Eon-Kyung Lee, Sungdo Ha, Sheung-Kown Kim 2001).

Finding the best method to solve the partner selection problem is a balanced choice between a highly complex model that translates the uncertainty and complexity of reality and a model simple enough to solve and appropriate to the situation and users. Since qualitative variables are paramount in the analysis at hand, a linear weighting model is preferred to create a simple yet robust approach for a start-up to apply, backed up by solid arguments. It is also the best method to use in this setup as its implementation is quick and inexpensive (Dimitris 2012).

The weighting linear model used in this work is mainly based on the work of Ávila et al. (2012) and structures the criteria into a hierarchy with generic and specific criteria. Each criterion is allocated a weight representing its relative importance in the selection process and indicators or analysis on which to base the evaluation. Each candidate is then evaluated individually through a value analysis with a defined scale for each criterion. These grades are multiplied by the weights to obtain a weighted final score for each prospective partner. The company with the highest rating represents the best fit for the firm (Ávila et al. 2012). The advantages of such method are that it is not costly to implement, time-efficient and simple enough to allow the start-up to further use it easily. The only disadvantage cited in the state of the art about this method is that the weight attribution is a subjective process (Dimitris 2012). Such limitation is however tackled in this work through the automated creation of multiple weighting scenarios to analyse through Excel’s Visual Basic Application.

This work’s objective is to help a start-up in its decision-making process on partner selection. At the same time, it addresses a gap in the state of the art on the specific subject. Indeed, only a few projects address the issue of partner selection in a

low-volume manufacturing environment and even less in an early stage outsourcing context. Thus tackling this issue for a medical equipment start-up with quantitative and qualitative analysis and a linear weighting method is original and this work may help further research on the topic.

3. Methodology

According to the outsourcing life cycle model disclosed below, Pristem is currently in the developing phase of its partnership (Kinnula 2004).

The developing phase consists in screening the environment for potential partners, evaluating them, selecting the most appropriate and negotiating the agreement. The screening and first selection phases have already been done by Pristem and have reduced the possibilities to five prospective partners. This thesis intends to support the start-up in the next steps of this phase, especially in evaluating the identified targets and selecting the best fit. In order to reach these objectives and after reviewing the state of the art on this subject, a linear weighting method including quantitative and qualitative criteria was selected as the most appropriate model. The method adapted from Ávila et al. paper (2012) relies on three main stages:

Selection and weighting of criteria to evaluate the partners

Evaluation of the partners on the different criteria and running of the linear model Partner selection and further considerations

3.1 Criteria selection and weighting

The criteria selection for this work is based on the literature review and adapted to the specific case at hand with the help of the start-up. Some selected criteria such as product reliability or price do not have any indicator available for now. This is due to the COVID-19 crisis that slowed down the partner selection process and prevented Pristem from receiving the quotes and offer from each potential partner. These criteria however are included in the work because they are considered as key to the decision-making process. The start-up will be able to easily fill in the blanks once it has all the necessary information and run the model multiple times to see if any change occurs. The generic criteria used

Figure 3 - Outsourcing lifecycle model

in this work are Quality, Finances, Performance, Collaboration and Communication and Production Capabilities.

Quality is probably the most cited criterion in partner selection problem and its indicators are diverse. Quality and precision in the products are unsurprisingly key criteria in the medical industry and also one of Pristem’s core value. Indeed, in its mission and company description the start-up mentions “Swiss quality”, “world-class”, “high-performance” and superior efficacy and lasting solutions are two core values in its manifesto (Pristem SA 2020). The generic quality criterion is translated in this work by the following specific criteria:

Processes conformity: through the use of medical quality standard ISO (Organisation Internationale de Normalisation 2020) or Good Manufacturing Practices (European Union 2003)

Product reliability: product release inspection failure rate

Repair services: proposed as internal or external process by the company Confidentiality: access or not to competitors’ production line during facilities visit

and under which conditions.

Performance is a general criterion that englobes the partner’s production volume and robustness history but also the organisational structure of each company, its reputation in the industry and market, its knowledge of the target market and the price it asks for the service. These are variables that help to complete the analysis by adding a view on the impact a company has on its environment and vice versa and to identify areas where synergies are possible. They also allow to see the evolution of a company in a time frame and are used by Caddick and Dale in their work (1987). In this project, the following performance aspects are analysed:

Knowledge of target market: current operations in SADC or similar countries Cost: estimation of the potential partner’s labour costs

History of performance: last annual sale volume on a similar product or product mix

Reputation and position in industry: judgment based on publicly available information

Organisation & management: overall level of respect of Good Manufacturing Practices, judgement based on publicly available information and first meetings with partners.

Production capabilities are also of high importance in an outsourcing partnership of low-volume manufacturing because there is no or little opportunity to test and refine the product before ramping the production. Prior production of similar products is therefore a source of learning that could serve as a facilitator of the manufacturing process and compensate the lack of testing and refinement opportunity (Javadi, Bruch, Bellgran 2016).

Production is also a matter or space, equipment and time to market capabilities. The latter is very important for Pristem, which investors want to get returns on their investment. The start-up follows a tight schedule which was disrupted by the COVID-19 crisis and manufacturers which can ramp-up to the target production volume in a shorter time frame own an advantage. This shorter ramp-up must not however impact the quality level of the production line and/or product. To evaluate production capabilities, current and future production capacities, technical capabilities are examined through the following indicators:

Current production capacity: in units per year available to Pristem today

Future production capacity: in units per year available to Pristem in the future with or without investment

Technical capabilities and resources: comparison of internal capabilities and resources of partner with Pristem needs

Capacity utilization: share of Pristem’s production in partner’s total volume Flexibility of operations: perceived ability to react to change based on meetings

with the partners and publicly available information.

Financial stability on the contrary is not a criterion that appears often in the literature even though it proved to be of high importance. A study by Twardy (2008) showed that partnerships in which companies use financial criteria to assess and select the partner are more likely to success. In this work, the selection of a financial criterion is justified by the start-up phase in which Pristem is. No company wants its business to be jeopardized by the financial distress or challenges of its partners but for companies that are still in a development phase a financially unhealthy partner brings high risks for their own growth and survival. The indicators selected are inspired by Mandru et al. (2010) use of the

Altman model. These are examples of ratios commonly used in the literature but for now, no information is available on the prospective partners. The complete financial analysis of the candidates is planned to be done during the following months and the results can then be incorporated into the model.

Financial health and stability: Ratios such as Net margin, Gross outcome of exploitation/Total assets or Book value equity / Book value of total debt.

Finally, soft skills like collaboration and communication capabilities have historically been judged not to be prevalent in a supply chain decision-making process. But this assumption is slowly changing as different partner selection problem research proved that cultural, management and strategy orientation compatibility are important criteria to succeed (Ellram, Zsidisin, Siferd, Stanly 2002; Eon-Kyung Lee, Sungdo Ha, Sheung-Kown Kim 2001; Lambert, Enz 2017). The goal of Pristem’s partnership is not only to outsource one stage of the production but to collaborate with an integrator on a new production line and processes and reach synergies through the partnership. Some similarities in the partners’ organisations like cultural and organisational fitness indicate higher chances of reaching such synergies. Literature on the subject indeed declares that to successfully apply quality and reliability tools within a new production process, it is necessary to consider the predominant and sub-cultural norms that exist within the partner organisation (Johansen 2005). Collaboration is evaluated with the following appreciations:

Motivation to do business: judgement based on first meetings with partners, identification of what the prospective partner win in the deal

Social relationship: cultural and inter-personal differences

All the previously mentioned criteria are then structured in a hierarchical model inspired by Saaty’s work (2002).

The goal of the decision-making process or question at hand is displayed at the top, followed by generic and specific criteria that describe how to reach the best decision. Below are displayed the possible solutions to the question that will be evaluated according to the criteria mentioned above. Each of these criteria can be attributed a weight that represents its importance in the decision-making process.

At this stage and when using linear weighting models, it is difficult to ensure criteria are hierarchized objectively (Dimitris 2012). To tackle this issue, the selected weighting scenario is completed by a multitude of other scenario created using Excel Visual Basic for Applications. The ten primary criteria are attributed three possible weights corresponding to extremely important, moderately important and slightly important and the creation of more than 50’000 weighting scenarios is automated. This process known as sensitivity analysis reduces the risk of subjective weights attribution by providing the full range of weight attribution possibilities. It also grants the start-up an automated tool in which weights can be easily changed if needed and to observe the impact on the decision result. This enables the start-up to closely monitor its decision-making process.

Question at hand

Generic criteria Specific criteria

Available solutions

Figure 4 – Saaty’s example of simple decision

3.2 Candidates’ evaluation

In the “Results” part of this work each partner is evaluated on the different criteria identified and analysed before. The quantitative data currently available to Pristem are explained and recorded. The ones to which Pristem does not have access yet are listed and explained. Once data is transmitted by the prospective partners, the key performance indicators can be completed and the decision-making tool adapts automatically. These KPIs are selected based on the literature review and Pristem’s COO expertise. The numbers are always to be taken carefully because when comparing companies with different structure, size and organisation; it is difficult to find and compare equal indicators. The qualitative analysis provided in the work allows one to contextualise such indicators and so a healthy scepticism is advised.

Moreover, Company E, which represents Pristem’s opportunity of developing its own subsidiary in South Africa cannot be directly compared to the other candidates. It indeed represents a different kind of investment for Pristem and since no production is yet functioning, all indicators cannot be filled. This is the reason why Company E is not included in the model but the scenario is evaluated on the side in the “Results” chapter. PESTEL Analysis of the different countries is important to get an overview of the environment in which each potential partner operates and the hurdles or opportunities it raises if a partnership is to be signed. The PESTEL analysis identifies key risks and opportunities in each country and relative to the political, economic, social, technological and legal spheres. In this work, the environmental criterion is not analysed because not of primary importance for Pristem at this stage. The technological aspect is mainly translated by infrastructure quality and the legal environment by administrative effectiveness in the country because they are the most important variables identified in these spheres for the sustainable development of Pristem’s partnership. These spheres have direct or indirect impact on the criteria selected for analysis. For example, a slow and highly bureaucratized administration will slow down and/or complicate the processes of getting the adequate certification for the production line. Economic and social instability can influence the financial viability of the partner and restrain its access to adequately trained workforce. The review of PESTEL in South Africa is also useful to Pristem in order to get deeper knowledge of its target market.

Moreover, the PESTEL analysis, along with the GLOBE Project results enables Pristem to plan monitoring processes for potential risks in the partnership and include appropriate terms and conditions in the partnership contract to reduce the probability of such risks arising. The GLOBE Project results are useful to underline any cultural difference that

could raise significant issues of miscommunication or lack of collaboration. As seen before, these two processes are very important for a start-up like Pristem in an early stage outsourcing manufacturing partnership and with a low volume production.

The companies organisation and production description are the basis to evaluate criteria such as production and collaboration capacity or the motivations of the candidates in entering the partnership. They provide important insights on how synergies can be reached or prevented. As quantitative data is not currently available for some selected criteria on production or quality, these analysis allow to get an appreciation of what the corresponding numbers could be.

For all these reasons, the qualitative analysis conducted in this work are crucial. They indeed allow to estimate quantitative data when the latter are not available but also nuance them when reviewed together. They are good tools to understand quantitative data and contextualise them in order to get a holistic view.

The partner evaluation is done for each criterion on a one to five scale, one being the lowest score. When possible, each score is accompanied by a description (in processes conformity, five equals to usage of ISO-13485 e.g.). If no indicator or scale is readily available for the criterion, a Likert quality scale as presented below is used with one corresponding to very poor and five to excellent performance in the criterion.

Each partner is evaluated individually and can get any score between one and five for each criterion. In order to translate reality as it is and not through a one partner-one score competitive method the same score can be given to two partners. Indeed if the previous

Figure 5 - Quality Likert scale with five levels

example of processes conformity is taken, two prospective partners can use the ISO-13485 and thus both receive the score of five. Unlike the weights attribution, only one evaluation for each partner in each criterion is taken into account but the scores can be changed anytime if needed.

3.3 Partner selection and further considerations

Weights and scores for individual criterion are then combined to calculate the final score of each partner according to the following logic:

Total score P1 = S(C1) * W(C1) + S(C2) * W(C2) + S(C3) * W(C3) + … + S(Cn) * W(Cn)

Where P1 is potential partner number 1, C1 is criterion number 1,

S is the score the potential partner was rated (1-5), W is the weight criteria are attributed (0-1),

n is the number of criteria selected, 10 in this case

One preferred weighting scenario and resulting partner selection is selected by Pristem COO and Supply Chain Manager to be further analysed. Their experience is valuable to the decision-making process because they know what the start-up will most benefit from. The other scenarios help in evaluating the nature and importance of the consequence of a change in criteria hierarchy on the partner selection. The database of scenarios is also analysed to determine if there is any pattern in the partner selection or to identify a partner that is repeatedly scoring better or worse than the others. The best and worst performing partners are then identified and their performance explained through a summary of the key points mentioned in the previous analysis.

4. Analysis

4.1 PESTEL Analysis

A PESTEL Analysis of each country in which the prospective partners are located is conducted in order to provide Pristem with an overview of the risks and opportunities linked with each scenario. The environmental sphere usually reviewed in a PESTEL Analysis is ignored in this work because not of primary importance for Pristem at this stage. These analyse nuance all criteria selected for the decision problem and provide a complete knowledge source to rely on to design the appropriate partnership contract.

South Africa

In 2019 South Africa ranks 70th over 180 countries in the Corruption Perception Index made by Transparency International with a score stagnating around 44/100 since 2015. The country was on a good track at the beginning of the 21st century but since then the situation worsened due to many scandals involving former presidents Mbeki and Zuma and the country is now at a lower level (Transparency International 2019).2

The corruption indicators are detailed in the table above, which reflects the situation in 2007. At that time, 16.9% of firms in South Africa saw corruption as a major constraint to business (World Bank 2020a). Moreover, it is reasonable to think that these numbers have considerably increased by now when we consider the degradation mentioned before. The sub-sections concerning import licenses and “to get things done” are of high

2 The higher the score, the less corrupted the public sector is perceived. The score can

go from 0 (high corruption) to 100 (very clean).

Figure 6 - Details of South Africa corruption table

importance for Pristem business. These indicators could materialize in additional costs and longer timelines.

South Africa possesses attractive economic assets such as a diversified and advanced economy thanks to abundant natural resources and a rising reserve of workforce but all these advantages do not seem to balance the social and political risks for investors. The country currently stands 106th out of 186 countries in the Index for Economic Freedom

(Heritage Foundation 2020) and the main reasons of this score are blurred regulations, societal unrest and poor infrastructure quality. World Bank data confirm this mediocre score; for example, to import goods, it usually takes more than five days to get and submit the documentation (36 hours) and pass border controls (87 hours) (World Bank 2020b). These numbers are one example of the South African economy inefficiency in dealing with administrative tasks, which dissuades investors from entering this market despite its initial attractiveness. These data corroborate the experience of Pristem’s Chief of Operations when visiting the start-up’s partners in South Africa. He explains that “in daily life and for any task, quality processes do not exist. It is always system D that prevails and problems are addressed only when they occur. There is no prevention and this is how things have been working since a long time”.3

Another aspect to take into account is South African’s highly volatile currency. The Rand (ZAR) is very sensitive to any shocks as shown in the figure displayed hereafter with the COVID-19 virus in year 2020 (Trading Economics 2020a). This volatility is a sign of economic instability and it arises uncertainty in the country and for the businesses.

3 Discussion with L.Sache and D. Chambert, respectively COO and Supply Chain Manager of

Also, South Africa has a heavy history of social unrest and violence due mainly to inequalities present in the country. Statistics show that crime and disorder are the main obstacles firms identify for business in South Africa. 76.4% of firms even pay security teams in order to secure their production (World Bank 2020a).

Beyond security issues, the frequent stops in production and the uncertainty caused by social demonstrations or strikes impact companies’ production costs, schedule and quality. This social unrest is a risk to quantify when developing a new business in South Africa and it will impact Pristem’s cost structure. Most strikes are unprotected ones organised by non-unionised workers and due to wages inequalities or lack of communication with the management (CIDB 2015). This is a vicious circle of poor conditions for the workers, which lead to social unrest, which in turn impacts negatively the company and thus the workers. More broadly, unemployment rate was 29.1% at the end of 2019 (Trading Economics 2020a). The Human Development Index summarizes well the reality of the social environment in South Africa, which currently stands at rank 113th over 189 countries (United Nations Development Programme 2019).

As far as technology is concerned, South Africa is a fairly innovative country, with a developed manufacturing industry. That is what explains the country’s 63th rank over 129

in the Global Innovation Index with the infrastructure and creative outputs themes ranking particularly far (Cornell INSEAD WIPO 2019). For example it usually takes more than three months to get an electrical connection and electricity outages are frequent all over

the country (World Bank 2020b). The unreliable infrastructure added to the frequent strikes could provoke stops in the production and result in a decreasing productivity for Pristem.

Finally, the regulation problem in South Africa is evident when looking at the table below showing the Ease of Doing Business scores. The worst scores for South Africa are indeed for resolving insolvency, enforcing contracts and registering property.

These three topics are related to the lack of robust laws and the poor ethics of staff to enforce them in South Africa despite recent attempts by the government to consolidate policies. Indeed, in the 2020 Index of Economic Freedom South Africa is still in a bad position concerning judicial effectiveness with a decreasing score of 38 over 100 (Heritage Foundation 2020).

France

France is a politically stable country even if its history has always been linked with strikes and demonstrations. The reform program implemented by President Macron has been the trigger of waves of social unrest in 2019 like the Yellow Vest movement or the transport sector strike. During these demonstrations the French police has been sometimes accused of using excessive force against protesters (Human Rights Watch 2020). These acts of civil conflict have seemed to gain more intensity in recent years with longer and more violent strikes even though the population benefits from relatively good living conditions; France’s Human Development Index rank is 26th over 189 (United

Nations Development Programme 2019).

Unions in France are quite powerful and played an important role in the social movements described above. A French employee works on average 36 hours a week,

Figure 8 – General topics scores for South Africa

which is the lowest average over the four countries under analysis; South Africa’s average is the highest with 43 hours per week, then comes Hungary and Italy with respectively 38 and 37 hours worked per week on average (ILOSTAT 2018). As in South Africa, these frequent strikes increase the risk of a lower productivity for the businesses with disruptions in the production flow. Labour union strength is a factor to integrate and monitor in the partnership strategy. Even though France is among the top third group of countries with best indicators, it is rarely in a good position in this group. It does not usually rank among OECD countries with very high indicators. For example, the 2020 Economic freedom index ranks it only 64th out of 186 countries. This rate is mainly due

to low labour freedom – explained by the strength of unions – and fiscal freedom due to its high tax rates (Heritage Foundation 2020).

In the economic sphere, France is an important international player ranking 6th worldwide

with a GDP estimated at $2.77 trillion in 2020 (International Monetary Fund 2020). Its economy is growing and diversified and unemployment is currently slightly decreasing (from 9.0 in 2018 to 8.4% in 2019) but government deficit is significant, amounting to more than 95% of the GDP (OECD 2020;Trading Economics 2020). When comparing France and South Africa’s World Bank indicators as displayed below, all scores are higher for France except Protecting Minority Investors, Getting Credit and Paying Taxes.

Trade across Borders in France is highly facilitated in Europe and worldwide thanks to the European Union bilateral agreements. As stated before, France is known as a high-tax country with income high-tax amounting to 33,3% for companies and that can go up to 45% for the wealthiest individuals (Trading Economics 2020b). Finally the Coronavirus

Figure 9 – General topics scores for France and South Africa

crisis will of course also have an impact on the country but its stable and diversified economy should be relatively resilient. France is a relatively attractive country for Pristem to have a partner thanks to this economic stability and an overall stable situation. On the technological level, France is a well-developed and innovative country with a history in IT, sciences and space technology. It occupies the 16th rank in the 2019 Global

Innovation Index with especially good scores in human capital and research and infrastructures (Cornell INSEAD WIPO 2019). President Macron announced in late 2019 a “massive investment of capital in French tech start-ups” through the French Tech Mission. This project intends to increase France’s technological level and promote innovative start-ups in order to become the “leading ecosystem” in Europe (Koksal 2019). This initiative will boost the country’s R&D sector and create an attractive environment for entrepreneurs, investors and international companies. The French territory benefits from an almost complete coverage and a high reliability of electricity supply (World Bank 2020b). A partner located in France would benefit from these trustworthy infrastructures and could thus focus more on innovation and technology development than in South Africa.

Hungary

Since its transition process from the Soviet bloc Communist countries Hungary has been a parliamentary republic. It is member of the EU since May 2004 and is preparing its entry into the Eurozone. Currently, the country is still using the Hungarian Forint (HUF) (European Union 2020). According to Human Watch (2011) there have been some concerning events in the last decade like the creation of a governmental media control body in 2011. Other scandals involving the Hungarian government into breaks of academic freedom, anti-migrant, anti-LGBT and xenophobic campaigns increased the human rights protection fragility in the country. There have been criticisms on the center-right government and clashes with the European Union (Human Rights Watch 2011). This political instability is translated in the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index, which ranks Hungary 70th over 180 countries with a decreasing score

of 44/100 (Transparency International 2019). The corporate sector also suffers from the situation with 12.1% of them choosing political instability as the biggest obstacle to doing business (World Bank 2020a; 2020b).

A partner located in Hungary would have to cope with this social and political instability that could have impacts on the functioning of the business. As far as economy is concerned, trade in the country is mainly with the European Union with 82% of exports

and 75% of imports intra-EU which makes Hungary heavily dependent on the EU (European Union 2020). Trade across borders in Hungary is facilitated by the EU agreements.

The Hungarian economy has been growing for the last decade thanks to a strong national household consumption encouraged by economic reforms like an increase of minimum wages (currently at 464.20 EUR per month against 1521 EUR in France), a tax reduction on food products and services and a substantial diminution of personal income and corporate taxes (Trading Economics 2020c). However, the economy in Hungary is weakened by social and political issues and has been heavily supported by EU funds for many years; Hungary has been under the EU Excessive Deficit Procedure since its entry into the union (European Union 2020).

The Hungarian Forint is somewhat less volatile than the South African Rand and like the latter, very sensitive to shocks such as the Coronavirus in March 2020 that is clearly identifiable in the figure above.

Due to this volatility and other factors, Hungary’s inflation rate (4.4%) is closer to the rate of South Africa (4.6%) that of France (1.6%) or the Euro Area average (1.2%) (Trading Economics 2020c). This rate and the fact that the current economic growth may be skewed due to EU cash injections are not encouraging a new business or partnerships in the country. This increases uncertainty and challenges the sustainability of Hungary’s

economy. The Coronavirus crisis emphasizes this uncertainty and as for any crisis, will probably have a significant impact on feeble economies like the Hungarian or Italian ones.

On the social sphere, there is a decline in population in Hungary. This phenomenon is probably due to the inequalities that strike the country, encouraging young qualified people to leave the country and pushing families to have less children. The Roma community, populations in rural areas and children are particularly at risk. For example it is estimated that one in every three children lives in poverty in Hungary (Benyik 2019). Pristem will be relatively spared by this issue as the prospective partner in Hungary is based in Budapest, which is part of the wealthiest and most developed counties in the country. However, the brain drain could impact Pristem’s partner in Hungary which may face a shortage of qualified workers.

Surprisingly, the Human Development Index is relatively high in Hungary, ranking 43rdover 189 but there are increasing concerns about corruption and government

intervention into media as explained before (United Nations Development Programme 2019). Far-right political parties are gaining strength mainly due to migration issues - some of Hungary’s frontier being borders of the European Union - and union manifestations against what they call a “slave law” are heavily repressed. This law, passed in 2018, raises for example the maximum amount of overtime possible in one year from 250 to 400 hours (Benyik 2019). All these aspects already led to a brain drain in some regions of Hungary (Benyik 2019) and could create high-skilled worker shortages at a national level which would impact negatively all the other spheres analysed in this section and businesses in the country, including Pristem’s partner. Finally Hungary is rated 33rd over 129 in the Global Innovation Index which is a relatively

good position but large differences are noticed between the themes analysed in this report. Indeed, market sophistication which computes credit, investment and trade indicators scores very badly at rank 76th while knowledge and technology outputs is

positioned 17th over 129 countries. This variability is also observed in the Ease of Doing

Business Survey. Indeed it reports that it takes longer to get electricity and construction permits in Hungary than in South Africa but the country gets better scores than the OECD high income countries in other aspects (World Bank 2020b).

These observations reinforce the feeling that Hungary is still a fragile state with a febrile political environment and which current economic prosperity could be only superficial, especially considering the uncertainty raised by the COVID-19.

Italy

On the graph below, it can be seen that Italy’s government integrity is located in between France and South Africa at a score of 62.2 (Heritage Foundation 2020).

Italy is a democratic parliamentary republic that has indeed known some political crisis in recent years leading to the creation of different unstable coalitions and an ever-changing Prime Minister.

These political issues have certainly damaged the Italian economy by increasing uncertainty and tainted the government credibility for its citizens but also for the European Union and the rest of the world (Ellyatt 2019). Even though the country is the world’s 8th biggest economy, GDP growth is declining since 2017. The country is

continually in a situation of trade-off between fuelling the economy and cutting the expenditures to diminish the government’s high debt (134.8% of GDP) (Trading Economics 2020e). This situation is subject to continuous tensions with the European Union. Italy’s import and exports are mainly intra-EU but its advantageous geographical location and large port in Genoa allows the country to diversify its trade and lower its dependence on the European Union when compared with Hungary.

But the bigger hurdle that the Italian economy is currently experiencing for its growth is the Coronavirus crisis. The virus is indeed touching Italy heavily due partly to its aging

Figure 11 – Government Integrity Score

47,5 83,3 46,6 62,2 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Hungary France South Africa Italy

population and experts project that the already ailing Italian economy will go through another severe recession cycle during the months and years following the COVID-19. Italy will probably need to ask for more financial help to the EU or to the IMF in the foreseeable future (Al Jazeera News 2020). In this context, starting a partnership with an Italian company arises risks.

When it comes to the social sphere, Italy’s dichotomy is more obvious than ever. In the Human Development Index Italy ranks 29th over 189, only a few place away from France

but this indicator does not integrate all the nuances the country possesses. Indeed, as for Hungary, the country experiences serious inequalities among its territory. The highly industrialised North obtains very good results – comparable to the ones of the OECD high income countries - but they are contrasted with the ones of the agricultural South, where life is harder and poverty higher. Since Pristem’s possible partner in Italy is based at the North of Milano, it is reasonably conservative to consider Italy’s national score in this analysis. One problem that is nation-wide - although more severe in the South - is the current high youth unemployment rate that reached 29.3% in early 2019 (Trading Economics 2020e). This rate along with the general unemployment rate will keep rising due to the Coronavirus crisis and its economic consequences mentioned before.

Technology and innovation is also a skewed subject in Italy as its development is pushed by the North of the country and held back by the South. Global Innovation Index ranks Italy 30th over 129 economies with very good scores in infrastructures and knowledge &

technology outputs but market sophistication records a bad mark, especially in the investment sub-section. The scores are however much closer in the different themes than for Hungary, which is a sign of robustness (Cornell INSEAD WIPO 2019).

Finally and concerning the legal sphere, different scores in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business show the ineffectiveness of the Italian administration. It is indeed almost as long to obtain an operating license or construction permit as in South Africa and much longer than in France or other EU countries. Enforcing contracts, paying taxes and getting credit also seem difficult tasks in Italy and on average all administrative processes take much more time in Italy than in the OECD high income countries.

From the comparison table below we can conclude that Italy’s score is higher than South Africa’s mainly thanks to the European Union and its free trade across border policy.

As for South Africa, the ineffective administration could slow down the implementation of the partnership in Italy and resulting in a lagging schedule for Pristem.

Source: Word Bank, 2020

4.2 GLOBE Results

The evaluation in this sub-section focuses on cultural differences in values and leadership styles between the countries of the prospective partners, Pristem, the installer and final customers. The evaluation is done based on GLOBE Project Cultural Values Analysis and Outstanding Leadership Analysis. The results are used to evaluate the communication and collaboration generic criterion.

GLOBE Cultural Values Analysis

The GLOBE Project culture groups map below shows us that France, Italy and the French part of Switzerland belong to what’s called Latin Europe (in orange), Hungary to Eastern Europe (in blue) and South Africa to Anglo & Sub-Saharan Africa (in red).

The supply chain alternative involving the highest number of different cultural groups is the Hungarian hypothesis in scenario one. Indeed, in this scenario three cultural groups are included in the supply chain with Pristem in Switzerland (Latin Europe), the integrator in Hungary (Eastern Europe) and the installer and final customers in South Africa and SADC countries (Anglo & Sub-Saharan Africa). This situation represents a slight disadvantage compared to other options where only two groups are involved and therefore miscommunication risks minimized. However it is important to consider also differences between the specific countries implied. Scenario two for example in which

Source: GLOBE Project, 2004

the installer and integrator are in South Africa has the advantage of including only two countries in the partnership compared to scenario one with three countries.

The table below summarizes the GLOBE Cultural Values scores for each country and the following Figures display the differences in each variable between the partner’s countries and respectively Switzerland (Figure 14) and South Africa (Figure15) (GLOBE 2007).4 Indeed, Switzerland for Pristem and South Africa for the installer and final

customers are two countries that stay fixed no matter the scenario and partners selected. This table and the ones used to create the Figures can be found in Appendix. 6.

Switzerland

South

Africa Italy France Hungary

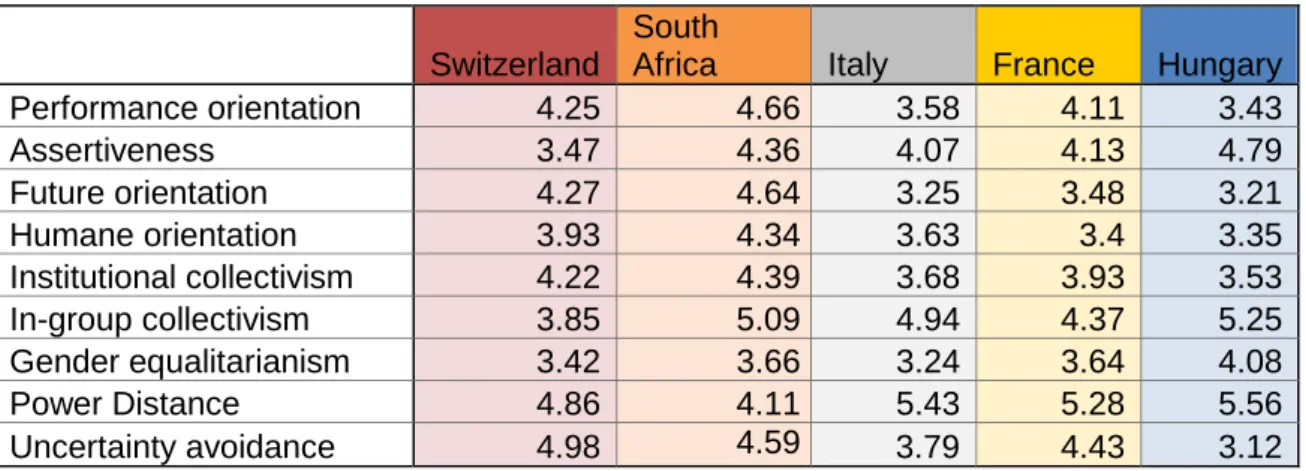

Performance orientation 4.25 4.66 3.58 4.11 3.43 Assertiveness 3.47 4.36 4.07 4.13 4.79 Future orientation 4.27 4.64 3.25 3.48 3.21 Humane orientation 3.93 4.34 3.63 3.4 3.35 Institutional collectivism 4.22 4.39 3.68 3.93 3.53 In-group collectivism 3.85 5.09 4.94 4.37 5.25 Gender equalitarianism 3.42 3.66 3.24 3.64 4.08 Power Distance 4.86 4.11 5.43 5.28 5.56 Uncertainty avoidance 4.98 4.59 3.79 4.43 3.12

4 Scores range from 1 (very low) to 7 (very high).

Table 1 – GLOBE Values scores