We dedicate this manual to the diverse assisted living

Texte intégral

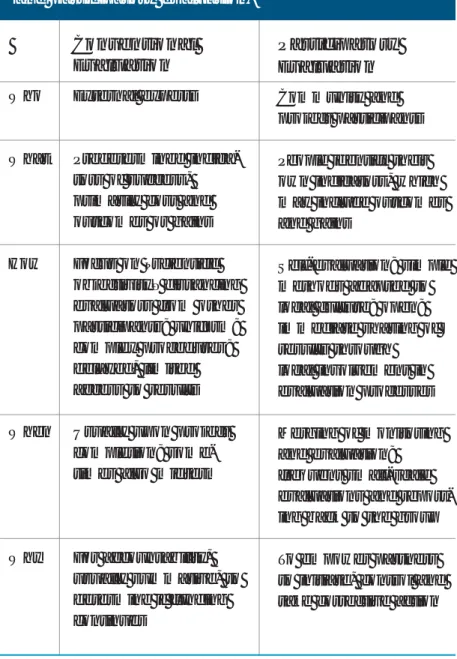

Figure

Documents relatifs

In DOREMI, the house itself is transformed in an unobtrusive monitoring environment able to keep track of the daily activities of the elderly people at risk of

Columbia University

– research discussions – paper presentations – practice talks. –

Class by David Jensen at University of Massachusetts, Amherst .!. DOING RESEARCH

Kurose, “10 pieces of advice I wish my PhD advisor had given

• Partnership between Regional Council, Memorial University, and MNL.

For long-living systems, explicit documentation of such context assumptions means that alternative context configurations, which specify permissable changes in the

The transfer of domiciliary care services from the AWBZ to the WMO, and more generally the upgrading of the role of local government in LTC by the additional transfer